?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper investigates whether local banking market structure affects regional entrepreneurship, measured by new firm formation. Considering provincial data over the period 2011–21 in Italy, we found that bank concentration and firm formation had an inverted ‘U’-shaped relationship. Lower levels of bank concentration fostered firm formation, but above a market share of about 58% for the largest banks, which is seen in the South and some peripheral and inner areas of central and northern Italy, increased concentration reduced firm formation. However, the presence of local banks is beneficial for the birth of new firms and can reduce the negative impact of high concentration. These findings suggest that banking market structure plays an important role in shaping regional entrepreneurship.

1. INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurship, or the start-up of new businesses, is increasingly recognized by academics and policymakers as an important driver of economic development. New small businesses increase competition and productivity in emerging industries, and foster innovation capacity and job creation (Acs & Storey, Citation2004). Ultimately, they are important in short- and long-term regional growth and prosperity (Ribeiro-Soriano, Citation2017).

The spatial distribution of firm formation varies considerably both between countries and at the subnational level. Within most countries there are regions with high rates of firm creation and regions with little entrepreneurial activity. The entrepreneurship literature suggests that these disparities are due to several socio-economic factors including industrial structure, the presence of physical infrastructure, access to finance, agglomeration economies, regional policies, cultural heritage, local history and individual personality traits (Del Monte et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Fritsch & Storey, Citation2014; Pan & Yang, Citation2019).

This paper focuses on one of these factors, access to finance, and investigates whether and how regional creation of new firms is affected by the market structure of the local banking industry. In many countries, the local credit market is the main source of funds for regional entrepreneurial activity and local banks play a crucial role in supporting the birth and development of firms. Previous studies have mainly analysed the relationship between bank structure and entrepreneurship at the national level, and have either neglected within-country differences or assumed that, if they exist at all, they are not particularly important (Deloof et al., Citation2019). Our empirical analysis is based on Italian provinces (NUTS-3 geographical level) between 2011 and 2021. Italy is interesting because both the rate of new firm creation and the characteristics of the local credit markets are strongly heterogeneous across geographical areas. The Italian banking industry is also undergoing important changes including increased concentration due to mergers and acquisitions between banks, giving more power to major banks and decreasing the number of small and local banks. These changes may have an important impact on both new firm formation and firm growth because bank financing is the primary source of funding for small and medium-sized Italian enterprises (Alessandrini et al., Citation2009).

Applying the generalized method of moments (GMM), the estimates suggest that banking market structure is an important factor shaping regional entrepreneurship. Bank concentration shows an inverted ‘U’-shaped relationship with regional firm formation. At low levels of concentration, increased concentration is associated with the creation of new firms. However, above a given threshold, corresponding to a market share of about 58% for the largest banks, increased concentration reduces new firm creation. This negative effect is found in many southern areas, where concentration of the banking market is well above 58%. This suggests the presence of a clear North–South divide in the conditions required to start new firms. This result is in contrast with other studies that have not emphasized a similar regional divide (e.g., Guiso et al., Citation2004). Other provinces that would be penalized by increased banking concentration are found in peripheral and inner areas of northern and central Italy. Increased concentration of the banking system would therefore increase regional disparities within the country, hampering firm formation in the South and in peripheral and inner areas of the Centre and North, but fostering it in other regions.

We also found that the presence of local banks promotes regional entrepreneurship, with a positive effect on the creation of new firms. This effect is independent of banking concentration and holds for all provinces of the country. The development of local banks would therefore be particularly important in areas that would be disadvantaged by greater concentration of the banking system. Bank concentration and the weight of local banks vary strongly across Italian provinces, and these results therefore have important implications for the policy debate on regional development, suggesting that market structure of the local banking industry plays a crucial role in shaping regional disparities in the rates of new firm formation. A moderate bank concentration and a strong presence of local banks facilitate the creation of new firms. Entrepreneurial activity, however, is hindered in provinces where the local banking market is highly concentrated and there are few local banks.

This study contributes to the literature on regional entrepreneurship by showing that the market structure of the banking industry is an important determinant of firm formation and that its effects vary across geographical areas depending on the characteristics of the local credit market. Most closely related to our analysis are studies by Bonaccorsi di Patti and Dell’Ariccia (Citation2004), Bergantino and Capozza (Citation2018) and Rogers (Citation2012). The first two of these documented a non-linear relationship between bank market power and new firm creation: low levels of market power fostered firm formation, and high levels of market power limited the creation of new firms. These effects were heterogeneous across industries and economic cycles. Like Bonaccorsi di Patti and Dell’Ariccia (Citation2004) and Bergantino and Capozza (Citation2018), we found evidence of a non-linear effect of bank market concentration on firm creation. However, our approach differs from theirs because we emphasized the implications for regional disparities in the rates of new firm formation, while their analysis focused on cross-industry differences at national level, and on the heterogeneity associated with periods of crisis.

Rogers (Citation2012) analysed the impact of bank competition on new firm creation. The results were mixed, depending on how competition is measured (number of banks or number of branches) and on the type of bank considered (unit banks – single, often small banks that offer financial services to a very local community – versus others). In line with his study, we found that different types of banks had varying impacts on new firm creation. We focused, however, on local banks, and showed that they had a positive effect on the local entrepreneurial activity. This result supports the theoretical model that considers relationship lending suitable to foster regional entrepreneurial activity. It also extends and is consistent with the line of research that emphasized the positive impact of small banks on local outcomes, such as employment and economic growth (Bernini & Brighi, Citation2018; Coccorese & Shaffer, Citation2021; Usai & Vannini, Citation2005). Our study also provides new evidence for Italy, which is particularly interesting in light of the recent wave of consolidation in the banking system. In the last few years there has been a strong reduction in the number of banks, from 740 in 2012 to 456 in 2021, and the number of branches, from 33,607 in 2011 to 21,650 in 2021. In 2021, the banks affected by these reductions were almost exclusively small and local banks, in 17 cases out of the total of 18. Lastly, from the methodological point of view, this study adds to previous work by estimating a dynamic empirical model, which takes into account the fact that regional creation of new firms is highly persistent over time. Previous analyses have not considered this aspect and their empirical results may be biased. The dynamic model was estimated using GMM, which also helps to account for potential endogeneity issues related to the variables capturing bank market structure.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the theory underlying the relationship between firm formation and banking market structure and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data, emphasizing the differences across Italian provinces in the rates of new firm creation, concentration of the banking industry and presence of local banks. It also defines the variables and discusses the methodology. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical analysis and section 5 concludes.

2. RELATED LITERATURE AND HYPOTHESES

2.1. Banking concentration and firm formation

Local financial development is an important driver for the creation of new firms and regional growth (Guiso et al., Citation2004). In many local contexts, the banking industry plays a crucial role in local entrepreneurship, and the structure of the local banking market determines the availability of resources to start new businesses. In particular, the concentration of the local banking market can affect the availability of resources to start and finance new firms. Studies have recognized that a certain degree of concentration is beneficial for entrepreneurship, because banks can take advantage of economies of scale and scope, provide a wide range of services and extend their geographical markets. This view suggests that higher concentration can increase credit availability for the creation and growth of new firms. The growth of banks that follows market consolidation can also allow them to use more sophisticated information and communication technologies, as well as advanced credit scoring and risk management systems to evaluate the creditworthiness of opaque borrowers. Large banks also have wider and more diversified portfolios and can be less risk averse. They may therefore provide more funds for new and young firms (Udell, Citation2009).

The positive relationship between banking industry concentration and new firm creation can also be explained using the information-based hypothesis, which is rooted in the asymmetries of information that arise between lenders and borrowers. In the presence of information asymmetries and agency costs, a lower concentration of the market may reduce banks’ incentives and efforts to screen borrowers to collect information, which may increase financing constraints for firms, especially those characterized by high opacity and riskiness (Dell’Ariccia & Marquez, Citation2004). This problem is especially relevant for startups, which have limited history, more uncertain prospects and are the most informationally opaque (Backman, Citation2015). A more concentrated market, where the number of banks is low, reduces adverse selection, moral hazard and hold-up problems. This has positive effects on credit availability for entrepreneurs to start new firms. Higher competition also reduces bank incentives to invest in new projects because future rents are positively associated with market power (Petersen & Rajan, Citation1995). These considerations suggest that banking concentration has a positive effect on the birth of new firms.

However, the traditional models of industrial organization lead to opposite conclusions, suggesting that bank concentration hinders firm formation. There, the presence in the market of many financial institutions is associated with better supply of credit to entrepreneurs, lower interest rates and fewer requirements for collateral (Besanko & Thakor, Citation1992; Guzman, Citation2000; Hainz et al., Citation2013). These models suggest that the concentration of the banking industry and the market power of banks are detrimental to entrepreneurship and new firm formation. This implication has been empirically supported by many studies showing that the consolidation of the banking industry reduces small business lending (Berger et al., Citation1998; Black & Strahan, Citation2002; Cetorelli & Strahan, Citation2006; Focarelli et al., Citation2002).

Two other strands of literature further support the idea that market concentration has a negative effect on the creation of new firms. One considers the geography of the banking industry and the other focuses on different styles of lending. Studies in the first area have shown that functional distance, or the distance between a bank headquarters and its branches, rather than physical distance between bank branches and borrowers, is an important determinant of bank lending policies, bank officers’ behaviour and availability of credit for local firms (Alessandrini et al., Citation2005). Banks with high functional distance have high organizational complexity and geographical and cultural distance between hierarchical layers. Information on creditworthiness of local firms is mainly soft and embedded in the local economy and society (Liberti & Petersen, Citation2019), and can only be acquired by local officers of a bank. Knowledge of firms’ creditworthiness is therefore asymmetric within the bank organization and it is difficult to transfer to the bank’s strategic and decisional office. Additionally, if the salaries and career opportunities of local officers depend on the performance of local branches, their lending strategies may be biased towards more profitable investments, typically associated with short-term projects based on hard information. In this case, high functional distance might lead banks to limit their lending to young and new firms in distant and peripheral areas, which are typically characterized by soft information and strong information asymmetries with lenders (Alessandrini et al., Citation2016). The consolidation of the banking industry has usually been accompanied by the concentration of bank headquarters in just a few financial centres, and therefore with an increase of functional distance. This therefore reduces local rates of new firm formation. Some empirical evidence is consistent with these implications (e.g., Uchida et al., Citation2012).

The second strand of work has analysed how the lending styles of banks affect credit availability for entrepreneurial activity. The main differences are between transactional lending and relationship lending. The former is based on hard information about borrowers, that is, information that is easy to gather from official sources (e.g., balance sheet data), and transfer to other offices or people, and is also quantifiable and comparable across borrowers (Liberti & Petersen, Citation2019). The latter, however, is based on soft information, which usually cannot be verified by anyone other than the agent who produced it (Stein, Citation2002). Examples of soft information include the business owner’s integrity, the local reputation for reliability or the quality of the firm’s management. This information is difficult to compare across borrowers and hard for outsiders to quantify and verify. Relationship lending takes advantage of repeated interactions between a bank and its clients to obtain and exploit this soft information, which enables banks to learn about borrowers’ creditworthiness. It has long been considered the most appropriate lending style for banks that lend to opaque and risky borrowers, such as small and new firms (Beck et al., Citation2018). Transaction-based lending is used mainly by large banks to supply standardized products and loans to large companies. The consolidation of the banking market has increased the average size of banks and moved lending strategies towards transactional lending. The increased concentration of the banking industry can therefore have a negative effect on the availability of financing for young and new firms.

This brief review of theoretical models and empirical analyses showed that the implications of bank concentration for firm creation are mixed. However, Berger et al. (Citation1998) provided some interesting results that could reconcile the two opposite views. They considered the consolidation of the banking industry and how it affects bank lending behaviour. They found that if the consolidation of the market led to a significant increase in the size of the banks, for example, as in the case of mergers between large banks or between a large bank with a smaller one, then the supply of small business financing decreased. However, if the mergers took place between small banks, and the average size of the banks increased moderately, then the supply of financing for new and small firms increased. It is therefore likely that the effect of banking concentration on firm formation depends on the level of concentration itself. If market concentration increases in a geographical market where it was previously low, banks increase small business lending because they benefit from economies of scale and scope, more diversified portfolios, wider geographical markets, and fewer problems of adverse selection. If market concentration increases above a given threshold, however, small business lending decreases because banks become more complex organizations and shift towards transactional lending.

Banking concentration and the availability of small business financing may depend not only on a consolidation process, but also on the geographical expansion strategies adopted by the different typologies of banks. One study, for example, considered savings banks in Spain and identified three types of geographical expansion: mainly in the regions in which the banks were already present; one into new geographical areas; and one across the whole country (Illueca et al., Citation2009). These strategies could provide different degrees of concentration in the various local banking markets.Footnote1 Therefore, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1: An increase of banking concentration fosters new firm formation in provinces where concentration is low, but it has a negative effect in provinces where concentration is already high.

2.2. Local banks and firm formation

The impact of the banking industry on regional development may depend on the type of banks operating in the area (Deloof & La Rocca, Citation2015). In general, small and local banks devote more of their lending resources to local small businesses than do large banks (Berger et al., Citation2001; Coccorese & Shaffer, Citation2021; Hasan et al., Citation2019; Rogers, Citation2012). They also support local growth (Usai & Vannini, Citation2005), dampen recession effects and foster resilience (Schneiberg & Parmentier, Citation2022).

Two main factors support the view that local banks foster local firm formation. First, small and local banks rely extensively on relationship lending, which is beneficial to local economic activity (Meslier et al., Citation2018). As discussed before, a common finding is that these types of banks have a comparative advantage in relationship lending based on soft information, while large banks are better equipped to use hard information for their transactional lending technologies. It therefore seems reasonable that the local banking market must have a substantial volume of small institutions to meet the demand from informationally opaque small and medium-sized enterprises (Berger & Udell, Citation2006). In a local bank, the principal–agent problem is weak because there are few organizational layers between the decision-making centre and the loan officer. These may even coincide. The loan officer retains the authority to make decisions about lending strategies and has much stronger incentives to invest in soft information. In large banks, however, the increased organizational complexity associated with many layers and the distance between the decision-making process and the loan officer reduce the incentives for local loan officers to invest in soft information collection (Berger et al., Citation1998). The systematic differences in the kinds of borrowers served by large and small banks have been verified at empirical level. Berger et al. (Citation2005), for example, found that companies borrowing from small banks tend to be smaller, geographically closer to their bank, and have a long-lasting relationship with their banker.

Some studies have provided empirical evidence of the important role of local banks in supporting new entrepreneurial activities. Hasan et al. (Citation2017), for example, considered cooperative banks, which are a specific type of local banks, and found that their presence in local banking markets was accompanied by more favourable conditions for new firm creation. Filomeni et al. (Citation2021) showed that organizational distance, defined as the physical distance between the branch in which the loan officer responsible for the credit evaluation operates and the bank’s headquarters, reduces the ability of a bank to ‘harden’ soft information, that is, to transform soft information into hard information that can be used to assess creditworthiness. Spatially based communication friction within banking organizations therefore affects lending decisions, especially in large and national banks characterized by higher organizational distance. This limits the use of relationship lending by these banks.

Second, it is widely recognized that lending decisions are affected by ‘home bias’. The geographical distance between bank headquarters and borrowers tends to reduce the social embedment of local branches. This has a negative effect on whether lending policies are designed to support the needs of the local economy (Alessandrini et al., Citation2016). Capital allocation is driven by both local lending opportunities, and several other factors including corporate politics, the power and influence of managers in the same branch organization, and the economic, social and political importance of the local economy surrounding the bank’s headquarters (Scharfstein & Stein, Citation2000). Increased distance between headquarters and branches can reduce the ability of local managers to attract internal resources, as well as the bank’s willingness to allocate resources to distant branches (Presbitero et al., Citation2014). Together these effects create home bias.

Several empirical analyses confirm the existence of home bias in lending decisions. Firms in regions with fewer local banks have less access to credit and little capacity to maintain a long-lasting relationship with their banks (Alessandrini et al., Citation2009; Claessens & Van Horen, Citation2014). The strength of home bias is more pronounced in times of crisis, when the supply of financing is constrained (Giannetti & Laeven, Citation2012; Presbitero et al., Citation2014). Home bias in lending strategies therefore means that the availability of funding for entrepreneurial activity is lower in regions where the credit market is composed mainly of functionally and physically distant banks. There, transaction and monitoring costs are higher (Bellucci et al., Citation2019) and the rates of new firm formation are lower (Ho & Wilhelmsson, Citation2022). However, a strong presence of small and local banks in a region is expected to stimulate access to credit for local entrepreneurs.

Building on these considerations, we therefore hypothesized:

Hypothesis 2: Local banks have a positive effect on the birth of local firms.

3. DATA, VARIABLES AND METHODOLOGY

3.1. Data and variables

To investigate whether banking market structure affects new firm creation at local level, we ran an econometric model. The data used in the empirical analysis were from a variety of sources and covered the period 2011–21. Information on new firm creation was from Movimprese, the statistical analysis on the creation and closure rates of Italian firms conducted by InfoCamere, which draws on the archives of all national chambers of commerce. Movimprese provides data on the total stock of active firms, newly created firms and closed firms by year and province of headquarters. We used these data to compute the dependent variable of the econometric model, which was new firms in non-financial industries as a percentage of total and non-financial firms in each province and in each year in the period 2011–21 (variable Birth rate).

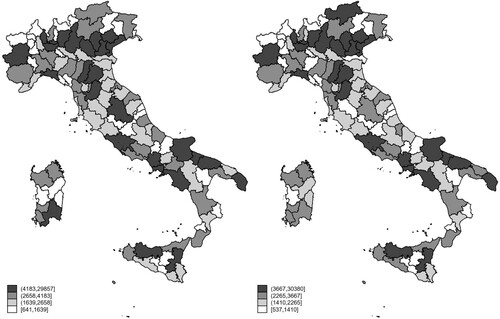

shows the spatial distribution of new firm formation (number) in the years 2011 and 2021. It suggests two main patterns. First, the number of new firms varies considerably across provinces and there are some clusters of provinces with both high and low numbers of new firms. There was strong entrepreneurial activity in some provinces of Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna in the North, Tuscany in the Centre and Campania, Apulia and Sicily in the South. However, there were low levels in some provinces of Piedmont and Veneto in the North, and Abruzzo, Molise, Basilicata, Sicily and Sardinia in the Mezzogiorno. Second, there was little variation between the two years. With few exceptions, provinces with high or low levels of new firm creation were essentially the same in 2011 and 2021. This suggests that entrepreneurship is a persistent phenomenon, at least within the short time horizon considered here.

Figure 1. Geographical distribution of new firm formation.

Data for the structure of the local credit markets were from the Bank of Italy, and its statistical series on Banks and Financial Institutions: Financing and Funding by Sector and Geographical Area. This collects data on bank deposits at the provincial level, broken down by categories of banks into major banks, large banks, medium banks, small banks and minor banks. Data are not available for individual banks but are aggregated into these five categories. The first group (major banks) basically corresponds to the six largest national banking groups, and the last group includes smaller and local banks.Footnote2 We used data on the aggregate deposits of these two groups to compute our proxies for banking structure at provincial level. The market share of major banks proxies banking concentration (Concentration), and the market share of minor banks proxies the presence and the weight of local banks (Local banks) in each province.Footnote3 Data were available for all years between 2011 and 2021.

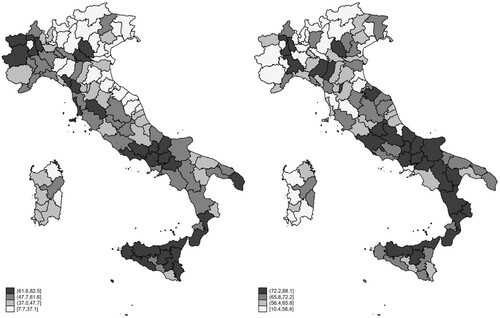

shows the proxy for banking concentration, that is, the market share of the largest banks, in each province in 2011 and 2021. There were strong differences between provinces, with concentration varying from 0.07 (Bozen) to 0.82 (Messina in Sicily) in 2011 and from 0.10 (again Bozen) to 0.87 in 2021 (Reggio Calabria in Calabria). Between the two years, the average concentration of the banking industry increased from 0.49 to 0.62. This trend, however, was much stronger in many southern provinces, where in 2021 concentration was above 0.72. Concentration also partially increased in some central provinces, mainly in the Marche region, but decreased in the North-West.

Figure 2. Concentration of the banking industry in Italian provinces.

The weight of local banks was more equally distributed across provinces than market concentration. shows descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables used in the empirical analysis. The standard deviation of Local banks was 8.7, just over half that of Concentration (15.2). During the period 2011–21, the market share of local banks on average decreased from 11% to 7%. also shows the variance inflation factors (VIFs) to assess potential multicollinearity. All VIFs were well below the threshold value of 10, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a significant concern in the analysis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

The empirical model included several controls highlighted by previous studies as important factors shaping entrepreneurship and new firm formation. To account for the size of local economy and the wealth of different provinces, we used population and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (variables Population and GDP pc). The source of data for these variables was Eurostat.

Education levels have been used in previous studies as a proxy for human capital, which in turn has a central role in fostering regional entrepreneurial activity (Qian et al., Citation2013). Therefore, we computed the variable Human capital as the share of the provincial population with a bachelor’s degree or higher. The source of data was the Italian Ministry of Education.

Unemployment is also an important driver of new firm formation, although the nature of its relationship with entrepreneurship is complex (Audretsch et al., Citation2015). To account for unemployment, the model included the rate of unemployment of people over 15 years old (Unemployment). Data were from the Italian Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). Lastly, the controls took into account the importance of venture capital financing. Venture capital is an important source of funding for the creation and growth of firms and can complement or substitute for bank financing (Pan & Yang, Citation2019). This aspect was covered by the variable Venture capital, which is the number of firms headquartered in a given province funded by venture capitalists. Information on venture capital investments came from AIFI, the Italian Association of Private Equity, Venture Capital and Private Debt. Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online summarizes the definition of variables and the sources of data.

3.2. Methodology

The base model specification of the econometric model was:

where the dependent variable measures new firms in non-financial industries as a percentage of total and non-financial firms in each province i and in each year t in the period 2011–21,

is the lagged dependent variable that enters the model as regressor in the dynamic specification,

is the vector of controls that vary across provinces and over time,

are time-fixed effects (FE) that control for time-varying unobserved heterogeneity and

is the random error term that captures all remaining effects.Footnote4 The coefficients of interest that allow us to understand the impact of the banking market structure on firm formation are

,

and

, which measure the short-term effects, or the effect after one period, of banking concentration and local banks. The model is dynamic, and the long-run effects on the rate of new firm formation are therefore given by these coefficients divided by

The coefficient

is also important to understand whether the dynamic specification of the model is appropriate to analyse regional new firm formation.

The model was estimated using system GMM, as specified by Arellano and Bover (Citation1995) and Blundell and Bond (Citation1998). System GMM is designed for ‘small T, large N’ panels, with few time periods and many individuals, and for models that are dynamic, in the sense that the dependent variable depends on its own past values. These values are correlated with the FE in the error term, violating one of the assumptions underlying ordinary least squares (OLS). System GMM accounts for this problem in two ways: by transforming the data to remove the FE and by instrumenting with past values that are uncorrelated with the FE. In other words, it takes into account the problem of endogeneity by using internal instruments. This strategy for endogeneity is also applied to the other endogenous variables. Endogeneity issues are particularly likely to arise for banking market variables. Market concentration and the presence of small and local banks in a province can affect local firm formation, but a causal relationship in the opposite direction cannot be excluded. If a province has low entrepreneurial activity, it is possible that the banking industry tends to be more concentrated, with fewer local banks. In this case, the empirical model would suffer from a problem of reverse causality, leading to biased estimates and making the results hard to interpret. System GMM is therefore a natural candidate for the model in this study, which includes data from few years but many provinces, a dependent variable measuring new firm creation, which is a highly persistent phenomenon, and various regressors that are potentially endogenous.Footnote5

The dependent variable measuring the birth of new firms was used as a percentage. GDP per capita, population and venture capital investments in local firms were used in logarithmic form. The main variables of interests concerning the banking structure and measuring the market share of the largest banks and local banks were expressed as percentages. Unemployment rate and the proxy of human capital were entered as shares.

4. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

The first set of estimates focused on the impact of bank concentration on new firm formation (). The bivariate regression reported in column (1) shows that the linear relationship between concentration and firm creation was not statistically significant. When the model also included the squared term Concentration sq, the relationship became highly significant: Concentration had a positive sign, and Concentration sq had a negative sign (column 2). This suggests the presence of a nonlinear relationship with an inverted ‘U’-shape. In other words, increasing bank concentration increases firm creation up to a certain threshold, but above this threshold, the impact becomes negative.

Table 2. Effect of bank concentration on firm formation.

Column (3) considers only the controls and column (4) shows the full model including bank concentration and controls. In this last specification, concentration and its squared term were significant at the 1% level, and both kept their sign. Of the control variables, population and venture capital investments were positively and significantly correlated with new firm formation, as expected, but the other controls were not statistically significant.

The lagged dependent variable (Lagged Y) was statistically significant at the 1% level in all model specifications. This supported the view that regional entrepreneurship is a persistent phenomenon over time and suggested that the empirical strategy to use a dynamic model specification was appropriate. The result is consistent with Fotopoulos (Citation2014), who showed that interregional differences in new firm formation are time persistent.

The diagnostic tests reported at the end of generally support the validity of the model specification. Looking at the full model in column (4), the Arellano–Bond test for the second order correlation of the residuals showed that they were not serially correlated, because the p-value was large enough and did not reject the null hypothesis that residuals in first differences were not correlated.

The Hansen test for the over-identifying restrictions supported the validity of the internal instruments, which could therefore be considered exogenous. The p-value of the test did not reject the null hypothesis that the instruments were uncorrelated with the residuals.

The second set of estimates extended the econometric model by adding the impact of local banks on firm creation (). Starting from the last model specification, we added the variable Local banks in isolation (column 1) and then with its squared term Local banks sq (column 2) to verify whether the relationship with new firm formation is nonlinear. The linear term was statistically significant at 5% when considered in isolation and at 10% when considered together with its square. Given that the squared term was not significant, the estimates suggest the presence of a linear effect of local banks on the creation of new firms. The positive coefficient attached to Local Banks implies that local banks foster new firm formation. The signs and significance of the variable related to bank concentration survived the inclusion in the model of local banks. The controls in general kept both their sign and statistical significance.

Table 3. Effect of bank concentration and local banks on firm formation.

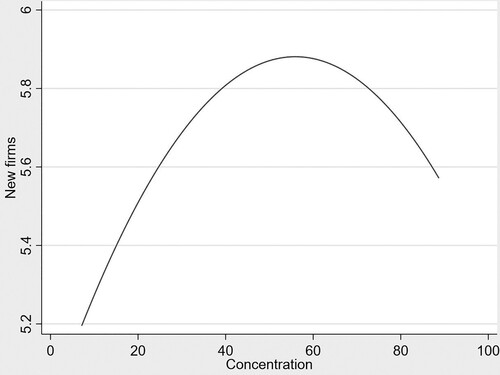

Based on these findings, we considered the specification in column (1) of to be the main regression of the analysis. plots the estimated relationship between the percentage of new firms and banking concentration. The point estimates indicate that the effect of bank concentration on the creation of new firms is positive until the market share of the largest banks reaches 58%. Above this threshold, the impact turns negative.

Figure 3. Estimated relationship between firm formation and bank concentration.

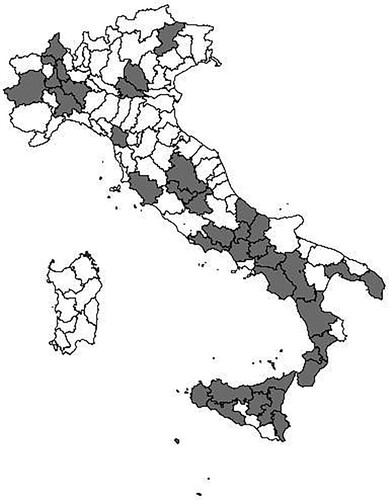

shows the provinces where the concentration of the local banking industry is above 58% (in dark grey) in 2021, the last year of our sample. Here, banking concentration is detrimental for firm formation. It is interesting to observe that most of these provinces are in the South of the country, although some provinces in the North-West and Centre also have a banking concentration above 58%. The location of these provinces suggests the presence of two distinct geographical patterns. First, there is a clear North–South divide: increased concentration of the banking system would be damaging for southern provinces but beneficial for many provinces in the rest of the country. Second, although many northern and central provinces would gain an advantage from increased banking concentration, some inner and peripheral provinces in these macro-areas would be penalized. A greater banking concentration would therefore increase regional disparities between southern provinces, inner and peripheral areas in the Centre–North and the rest of the country.

Figure 4. Provinces with banking concentration above 58% in 2021.

Coming back to the point estimates, the impact of greater concentration on the birth of firms was non-linear and depended on the starting value of concentration. To quantify the economic size, we considered a long-term increase in concentration of 10% in two provinces, Sondrio and Brindisi. In the former, banking concentration is 20%, and a 10% increase means that new firms increase by 0.7%.Footnote6 In the latter province, banking concentration is 70% and a 10% increase reduces firm formation by 0.4% in the long term. The disparity between the two provinces would therefore increase by 1.1%, which is not negligible.

Considering the economic impact of local banks, if their market share increases by 10%, the creation of new firms as a percentage of total firms in the province increases by 0.07% in the short term, and 0.3% in the long term.Footnote7 The latter result is similar to Rogers (Citation2012), who found an increase of 0.2% in new firms when the market share of local banks increased by 10%. This does not seem very high, but Rogers noted that it would mean almost 8000 new firms in a state such as Texas, which is economically significant. Similarly, if we look at the province of Naples in 2021, an increase of 0.3% in new firms is equal to 940 more firms in the province, which is an important change for local employment and growth.

Until now, we have considered the impact of market concentration and local banks on the birth of new firms. We also investigated whether the birth of new firms is affected by the presence of other groups of banks. To achieve this, the model was extended to include the market share of large banks (variable Large banks) in column (3), the market share of medium banks (Medium banks) in column (4), and the market share of small banks (Small banks) in column (5). None of these variables was statistically significant, and the variables for market concentration and local banks preserved their sign and significance. This suggests that the other types of banks do not have a clear and significant impact on the birth of local firms.

Lastly, we performed a moderation analysis to assess whether local banks can modify the relationship between the concentration of the banking industry and the creation of new firms. In column (6), we introduced the interaction terms between Local banks and Concentration (variable Local banks*Concentration) and Local banks and Concentration sq (variable Local banks*Concentration sq). The underlying variables remained significant, with the same sign as before, but the interactions were not significant. This result suggests that the presence of local banks in a province and the concentration of the local banking industry are two independent phenomena that affect firm formation through different channels. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that large and small banks serve different types of borrowers. Large banks are oriented towards large and well-established borrowers, who tend to have relatively long track records with audited financial statements, and thus credit decisions can be made using hard information (DeYoung et al., Citation2004). However, local banks are more likely to lend to smaller and marginal borrowers.

Overall, these results provide support for Hypotheses 1 and 2.

To corroborate the main findings of the analysis, we applied several checks of robustness to the specification in column (1) of . The estimates are summarized in . First, we used a different econometric strategy by estimating a FE model. FE has the advantage over the GMM model used in the main analysis that it can control for unobserved and time-invariant heterogeneity at the provincial level. However, it cannot manage endogeneity through internal instruments and does not provide unbiased estimates of the autoregressive term of the dependent variable. The FE estimates reported in column (1) confirmed the statistical significance of the explanatory variables of interest. The estimated coefficient of the autoregressive term is smaller, confirming that FE estimates are biased in dynamic models. It is worth noting that FE gives us an idea of the explanatory power of the model looking at the overall R2, which is 0.59, and therefore not very high. This is consistent with previous studies, which have identified many determinants of regional entrepreneurship. The characteristics of local banking markets are therefore only a part of the story that explains regional disparities in firm formation.

Table 4. Robustness checks to the main analysis.

Second, we considered a different dependent variable, with the number of new firms scaled by provincial population (New firms pc) instead of the total stock of firms, as in the main analysis. The second variable could blur the identification of the impact of the local banking market on firm formation if banking concentration and the presence of local banks affect both the birth of new firms and the stock of existing ones, for example through their probability of survival. The estimates in column (2) are consistent with the main analysis and we are confident that the impact of the local banking market does not depend on how the dependent variable is measured.Footnote8

Third, to check the robustness of the impact of banking concentration, we used the Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI), which is commonly used in the literature to measure concentration. The advantage of this measure is that it provides a single variable covering the market share of all banks, while the proxy used in the main analysis considered only the largest banks.Footnote9 Column (3) shows the index computed on deposits and column (4) on bank branches. The results confirm the inverted ‘U’-shaped relationship with the birth of new firms.

Fourth, we replicated the main regression using a restricted sample that considered only the years after 2015. In that year, the Bank of Italy slightly changed the classification of Italian banks. The data were harmonized for the three years before 2015, but it is possible that the five groups of banks that we used to compute our proxies of market concentration included different banks over time. Therefore, we tested whether our main results held after the changed classification. The number of observations decreased to 630 and the estimates were similar to the main ones (column 5). We can therefore assume that this measurement issue did not affect our results.

Fifth, we used different time lags for the instruments in the GMM estimates. In the main analysis, we used the lags and

, while in column (6), we considered only instruments in

and in column (7) we used all available instruments from

to the end of the period. These different time lags did not change the main results of the analysis.

Lastly, in column (8), we focused on more innovative new firms. These firms were identified using the high-tech classification of manufacturing industries adopted by Eurostat. The numerator of the dependent variable was the number of new firms in the knowledge-intensive services and high-technology manufacturing industries. With this alternative dependent variable, the regressors on unemployment and education became significant. The negative sign attached to unemployment is probably because high unemployment rates are associated with a lower demand for advanced technology activities in a region, which in turn reduces pressure for new firm formation (Armington & Acs, Citation2002; Audretsch et al., Citation2015). The result for education is consistent with other studies, emphasizing that the positive effect of human capital on new firm formation is particularly important in high-tech industries (e.g., Qian et al., Citation2013).

Appendix B in the supplemental data online provides some further checks of robustness to account for multicollinearity, a different measure of HHI based on loans, and endogeneity issues.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This paper has examined the impact of banking market structure on regional variation of new firm formation in Italy. Two main characteristics of the local banking markets have been considered: concentration and the weight of local banks.

Regional creation of new firms and banking concentration have an inverted ‘U’-shaped relationship. At low levels, increased concentration fosters new firm formation. However, above a given threshold, which corresponds to a market share of 58% of the largest banks, increased concentration of the banking market reduces the creation of new firms. Concentration is diffusely above 58% in the South and in some peripheral and inner provinces of the Centre and North-West of Italy. The new wave of consolidation that is affecting the national banking industry will therefore have an asymmetric impact across geographical areas, driven by the North–South and the Centre–periphery divides that have become clear in this analysis. In the last few years, in fact, there have been several important mergers and acquisitions among large Italian banks, such as the acquisition of UBI Banca, the fifth largest bank, by Intesa Sanpaolo, the largest bank. This could increase regional disparities in the rate of new firm formation.

On the other hand, the presence of local banks in a given area is beneficial for the creation of new firms. This positive effect could mitigate the negative impact of increased consolidation in provinces where the banking market is already highly concentrated. The estimates, however, showed that the impact of market concentration and local banks were independent of each other, supporting the view that small and large banks serve different types of borrowers. Small banks are more likely to finance smaller and more opaque borrowers, and large banks are focused on larger and well-established borrowers.

Taken together, these findings are consistent with the literature emphasizing that banking market structure plays an important role in new firm formation. However, while previous studies have focused on cross-country analysis, we contributed to the literature on entrepreneurship and regional economics by showing that the different characteristics of local banking markets within Italy help to explain the geographical disparities in new firm formation across areas. Musolino et al. (Citation2022) showed that southern regions are less attractive for entrepreneurial activity and suggested the lack of accessibility and infrastructure as possible explanations. Our analysis suggested that high banking concentration and a weak presence of local banks are other factors that can explain and widen both the North–South divide and disparities between peripheral and central areas of the country.

Our findings may be interesting for other countries where small and local banks are important players of the credit market, and the industrial structure is based on the presence of small and medium enterprises. Further research, however, is needed to assess the external validity of our results in other national contexts.

In Italy, successive waves of reform in the banking industry have strongly reduced the number of banks. In the last decade, the number has decreased from 740 to 456. This is a common trend in most European countries, where the number of banks has continuously decreased as a result of mergers and acquisitions. In some countries, however, the consolidation of the banking market has progressed more slowly. In Germany, for example, there are currently about 1500 banks, many of which are small and local banks with a regional focus, and subject to regional principles and needs. Similarly, it may also be helpful if small and local banks in Italy keep their role in supporting local entrepreneurship, employment and, indirectly, local growth. A banking market model centred on the role of large banks does not seem adequate to support Italian industry because of the strong regional disparities that characterize local economic systems and firms. In most Italian regions, there are few large companies and small firms are the backbone of the economy.Footnote10 For these firms, relationship lending is the best option, and small banks the most appropriate lenders. However, the ongoing process of consolidation of the banking industry is shaping a model based on the presence of large and complex banks, which are more oriented towards transactional lending. This trend does not take into account local credit market conditions, or the needs of new local firms. It could therefore be a source of serious concern about access to finance for regional new firms. The consolidation of the national banking market may be desirable for reasons linked to cost saving, revenue enhancement and market stability. However, policymakers should balance these important objectives against the equally important need to support regional economies. They should therefore preserve and encourage the presence of small and local banks, and their lending relationships with new local firms, especially in areas affected by lower economic growth.

This view is consistent with some previous studies that have criticized the consolidation trend among cooperative and mutual banks. These banks are considered a safe local point of reference and providers of funding for small and medium-sized firms, artisans, and families that operate in local areas (Coccorese & Shaffer, Citation2021). Mergers and acquisitions between cooperative banks do not provide clear and significant gains of efficiency, and the increased size resulting from consolidation can weaken the capacity to support local firms (Coccorese & Ferri, Citation2020). Public policy should therefore take into account the important role played by cooperative banks, and local banks in general, in the provision of financial resources to local entrepreneurship and, ultimately, in enhancing local economic development.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (110.9 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The study showed that the different expansion strategies had heterogeneous effects on bank productivity. In particular, savings banks that expanded into new markets achieved greater productivity gains; these gains were only partially due to the changes in the bank risk (Prior et al., Citation2019).

2 As reported in the statistical appendix of the Annual Report of the Bank of Italy, the six largest banking groups are UniCredit, Intesa Sanpaolo, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, UBI Banca, Cassa Depositi e Prestiti and Banco BPM.

3 We considered that all minor banks were local banks. There may be some small banks that are also local, but this group includes some banks that operate nationally, and therefore cannot be considered local (e.g., Banca Sella and Banca Mediolanum). We are therefore confident that our variable only includes genuinely local banks, but we have probably underestimated their weight because some local banks are also included in the group of small banks.

4 We have a panel of 105 Italian provinces over 11 years. We lost one year for the lagged dependent variable included among the regressors, leaving a total of 1050 observations.

5 The GMM estimator has poor small sample properties but is strongly consistent and asymptotically normal in large samples. GMM also requires minimal assumptions about the data-generating process, especially on the distribution of the error term. This is often a strength because most models are based on distributional assumptions such as normality (Verbeek Citation2017). Besides being consistent and asymptotically normal, GMM is the most efficient estimator in the class of estimators that do not use any extra information aside from that contained in the moment conditions. Because of the good large sample properties and few assumptions on the model specification, GMM is an appropriate methodology in our analysis.

6 As specified in section 3.2., in a dynamic model the long-term impact of a regressor on the dependent variable is . Therefore, the long-term coefficient is 0.1202 for Concentration and –0.0011 for Concentration sq. If Concentration changes from 20% to 30%, and therefore Concentration sq changes from 400 to 900, the rate of new firms increases by 0.67%, holding other regressors at their mean values.

7 A 1% increase of concentration leads to and a 10% increase leads to a 0.3% increase in new firms over total firms in non-financial industries.

8 In this regression, we removed the control concerning total population because it was used to compute the dependent variable. The estimates, however, are similar if the variable is still included or if other proxies of provincial size, such as the total stock of firms or GDP, are included in the model. Lastly, the results are also confirmed if the dependent variable is measured using the raw number of new firms.

9 As explained in section 3, unfortunately yearly information on every bank in the Italian provinces is not available. Therefore, we computed the HHI using the deposit market shares of the five groups of banks described in section 3.

10 The Italian industrial structure is characterized by few large firms with an asymmetric geographical distribution. In 2020, there were 2856 large firms (firms with more than 250 employees) headquartered in the North, 802 in the Centre and 402 in the South. Most firms nationally (95.1%) had fewer than 10 employees. This percentage is higher in the South (96.2%), and close to 98% in southern provinces such as Nuoro, Enna and Reggio Calabria.

REFERENCES

- Acs, Z. J., & Storey, D. J. (2004). Introduction: Entrepreneurship and economic development. Regional Studies, 38(8), 871–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340042000280901

- Alessandrini, P., Croci, M., & Zazzaro, A. (2005). The geography of banking power: The role of functional distances. BNL Quarterly Review, 58(235), 129–167.

- Alessandrini, P., Fratianni, M., Papi, L., & Zazzaro, A. (2016). Banks, regions and development after the crisis and under the new regulatory system. Credit and Capital Markets, 5, 536–560. https://doi.org/10.3790/ccm.49.4.535

- Alessandrini, P., Presbitero, A. F., & Zazzaro, A. (2009). Banks, distances and firms’ financing constraints. Review of Finance, 13(2), 261–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfn010

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(94)01642-D

- Armington, C., & Acs, Z. J. (2002). The determinants of regional variation in new firm formation. Regional Studies, 36(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400120099843

- Audretsch, D. B., Dohse, D., & Niebuhr, A. (2015). Regional unemployment structure and new firm formation. Papers in Regional Science, 94, S115–S138. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12169

- Backman, M. (2015). Banks and new firm formation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 22(4), 734–761. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-03-2013-0035

- Beck, T., Degryse, H., De Haas, R., & Van Horen, N. (2018). When arm’s length is too far. Relationship banking over the credit cycle. Journal of Financial Economics, 127(1), 174–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.11.007

- Bellucci, A., Borisov, A., Giombini, G., & Zazzaro, A. (2019). Collateralization and distance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 100, 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.01.011

- Bergantino, A. S., & Capozza, C. (2018). Banking market structure and industry growth in the Central-East Europe region. Empirical Economics, 54(3), 1319–1333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-017-1262-1

- Berger, A. N., Klapper, L., & Udell, G. F. (2001). The ability of banks to lend to informationally opaque small businesses. Policy Research Working Paper No. 2656. World Bank, Washington, DC.

- Berger, A. N., Saunders, A., Scalise, J. M., & Udell, G. F. (1998). The effects of bank mergers and acquisitions on small business lending. Journal of Financial Economics, 50(2), 187–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00036-1

- Berger, A. N., & Udell, G. F. (2006). A more complete conceptual framework for SME finance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(11), 2945–2966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2006.05.008

- Berger, N., Miller, N. H., Petersen, M. A., Rajan, R. G., & Stein, J. C. (2005). Does function follow organizational form? Evidence from the lending practices of large and small banks. Journal of Financial Economics, 76(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.06.003

- Bernini, C., & Brighi, P. (2018). Bank branches expansion, efficiency and local economic growth. Regional Studies, 52(10), 1332–1345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1380304

- Besanko, D., & Thakor, A. V. (1992). Banking deregulation: Allocational consequences of relaxing entry barriers. Journal of Banking & Finance, 16(5), 909–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-4266(92)90032-U

- Black, S. E., & Strahan, P. E. (2002). Entrepreneurship and bank credit availability. The Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2807–2833. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00513

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8.

- Bonaccorsi di Patti, E., & Dell’Ariccia, G. (2004). Banking competition and firm creation. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 36(2), 225–251. https://doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2004.0011

- Cetorelli, N., & Strahan, P. E. (2006). Finance as a barrier to entry: Bank competition and industry structure in local US markets. The Journal of Finance, 61(1), 437–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00841.x

- Claessens, S., & Van Horen, N. (2014). Location decisions of foreign banks and competitor remoteness. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 46(1), 145–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12100

- Coccorese, P., & Ferri, G. (2020). Are mergers among cooperative banks worth a dime? Evidence on efficiency effects of M&As in Italy. Economic Modelling, 84, 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.04.002

- Coccorese, P., & Shaffer, S. (2021). Cooperative banks and local economic growth. Regional Studies, 55(2), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1802003

- Dell’Ariccia, G., & Marquez, R. (2004). Information and bank credit allocation. Journal of Financial Economics, 72(1), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00210-1

- Del Monte, A., Moccia, S., & Pennacchio, L. (2021). Cultural environment, entrepreneurship and innovation in Europe. The importance of history. Il Capitale Culturale, Studies on the Value of Cultural Heritage, 23, 111–139.

- Del Monte, A., Moccia, S., & Pennacchio, L. (2022). Regional entrepreneurship and innovation: Historical roots and the impact on the growth of regions. Small Business Economics, 58(1), 451–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00425-w

- Deloof, M., & La Rocca, M. (2015). Local financial development and the trade credit policy of Italian SMEs. Small Business Economics, 44(4), 905–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9617-x

- Deloof, M., La Rocca, M., & Vanacker, T. (2019). Local banking development and the use of debt financing by new firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(6), 1250–1276. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718783486

- DeYoung, R., Hunter, W. C., & Udell, G. F. (2004). The past, present, and probable future for community banks. Journal of Financial Services Research, 25(2/3), 85–133. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:FINA.0000020656.65653.79

- Filomeni, S., Udell, G. F., & Zazzaro, A. (2021). Hardening soft information: Does organizational distance matter? The European Journal of Finance, 27(9), 897–927. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2020.1857812

- Focarelli, D., Panetta, F., & Salleo, C. (2002). Why do banks merge? Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 34(4), 1047–1066. https://doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2002.0054

- Fotopoulos, G. (2014). On the spatial stickiness of UK new firm formation rates. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(3), 651–679. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbt011

- Fritsch, M., & Storey, D. J. (2014). Entrepreneurship in a regional context: Historical roots, recent developments and future challenges. Regional Studies, 48(6), 939–954. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.892574

- Giannetti, M., & Laeven, L. (2012). The flight home effect: Evidence from the syndicated loan market during financial crises. Journal of Financial Economics, 104(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.12.006

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2004). Does local financial development matter? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(3), 929–969. https://doi.org/10.1162/0033553041502162

- Guzman, M. (2000). Bank structure, capital accumulation and growth: A simple macroeconomic model. Economic Theory, 16(2), 421–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00004091

- Hainz, C., Weill, L., & Godlewski, C. J. (2013). Bank competition and collateral: Theory and evidence. Journal of Financial Services Research, 44(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-012-0141-3

- Hasan, I., Jackowicz, K., Kowalewski, O., & Kozłowski, Ł. (2017). Do local banking market structures matter for SME financing and performance? New evidence from an emerging economy. Journal of Banking & Finance, 79, 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2017.03.009

- Hasan, I., Jackowicz, K., Kowalewski, O., & Kozłowski, Ł. (2019). The economic impact of changes in local bank presence. Regional Studies, 53(5), 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1475729

- Ho, C. S. T., & Wilhelmsson, M. (2022). Geographical accessibility to bank branches and its relationship to new firm formation in Sweden via multiscale geographically weighted regression. Review of Regional Research, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-022-00166-1

- Illueca, M., Pastor, J. M., & Tortosa-Ausina, E. (2009). The effects of geographic expansion on the productivity of Spanish savings banks. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 32(2), 119–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-009-0138-6

- Liberti, J. M., & Petersen, M. A. (2019). Information: Hard and soft. The Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 8(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/rcfs/cfy009

- Meslier, C., Sauviat, A., & Yuan, D. (2018). Local banking market structure, external financial dependence and economic activity: A new assessment of the benefits of relationship banking. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3103792

- Musolino, D., Meester, W., & Pellenbarg, P. (2022). Stated locational preferences of Italian entrepreneurs: The underlying location factors. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 14(4), 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12498

- Pan, F., & Yang, B. (2019). Financial development and the geographies of startup cities: Evidence from China. Small Business Economics, 52(3), 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9983-2

- Petersen, M., & Rajan, R. (1995). The effect of credit market competition on lending relationships. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 407–443. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118445

- Presbitero, A. F., Udell, G. F., & Zazzaro, A. (2014). The home bias and the credit crunch: A regional perspective. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 46(s1), 53–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmcb.12078

- Prior, D., Tortosa-Ausina, E., & García-Alcober, M. P. (2019). Profit efficiency and earnings quality: Evidence from the Spanish banking industry. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 51(2–3), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-019-00553-w

- Qian, H., Acs, Z. J., & Stough, R. R. (2013). Regional systems of entrepreneurship: The nexus of human capital, knowledge and new firm formation. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(4), 559–587. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbs009

- Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2017). Small business and entrepreneurship: Their role in economic and social development. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(1–2), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1255438

- Rogers, T. M. (2012). Bank market structure and entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 909–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9320-0

- Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (2000). The dark side of internal capital markets: Divisional rent-seeking and inefficient investment. The Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2537–2564. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00299

- Schneiberg, M., & Parmentier, E. (2022). Banking structure, economic resilience and unemployment trajectories in US counties during the great recession. Socio-Economic Review, 20(1), 85–139. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwaa039

- Stein, J. C. (2002). Information production and capital allocation: Decentralized versus hierarchical firms. The Journal of Finance, 57(5), 1891–1921. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00483

- Uchida, H., Udell, G. F., & Yamori, N. (2012). Loan officers and relationship lending to SMEs. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 21(1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2011.06.002

- Udell, G. F. (2009). Innovation, organizations and small business lending. In P. Alessandrini, M. Fratianni, & A. Zazzaro (Eds.), The changing geography of banking and finance (pp. 15–26). Springer.

- Usai, S., & Vannini, M. (2005). Banking structure and regional economic growth: Lessons from Italy. The Annals of Regional Science, 39(4), 691–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-005-0022-x

- Verbeek, M. (2017). A guide to modern econometrics. Wiley.