ABSTRACT

While it is widely acknowledged that entrepreneurial processes are embedded in an institutional framework, understanding exactly how institutions impact Entrepreneurial Ecosystems (EEs) remains a challenge. This is especially the case for informal institutions, and in particular those not directly related to entrepreneurship support. This paper contributes to this gap by addressing the question: How can an informal institution – not directly related to entrepreneurship support – shape entrepreneurial processes within an EE? It relies on a qualitative case study of a regional EE in Colombia, drawing on direct observation, semi-structured interviews, and secondary data analysis. ‘Take it easy’ was identified as an informal institution of the Colombian Caribbean where the analysed EE is located. Contrary to expectations, ‘take it easy’ does not refer to laziness; rather, it refers to doing things calmly, including conflict avoidance and an a preference for entertainment. While ‘take it easy’ is specific to this case study, the notion that informal institutions linked to individual agency and behaviour affect EE performance applies to any context.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial processes are embedded in an institutional framework (Ács et al., Citation2014; Welter, Citation2011), but it remains a challenge to understand exactly how institutions impact Entrepreneurial Ecosystems (EEs) (Borissenko & Boschma, Citation2017; Welter & Baker, Citation2021). This is true of informal institutions, especially those not directly related to entrepreneurship support. Even though culture is a determinant in entrepreneurship, it is not clear how it shapes individual and organisational action within the EE (Roundy, Citation2017). The field requires more research into the role of informal institutions – and particularly those that are not directly related to entrepreneurial support functions – in determining the functioning of EEs. This paper contributes to this gap by addressing the question: How can an informal institution shape entrepreneurial processes within an EE? It presents a qualitative case study of the EE in the department Atlántico in Colombia, drawing on participant observation and semi-structured interviews with 25 entrepreneurs and 14 EE actors, complemented with secondary data analysis. This paper is structured as follows: first the literature regarding EE and informal institutions is reviewed, and existing gaps highlighted, then the case of Atlántico Colombia is introduced before the analysis of the ‘take it easy’ culture is presented, followed by a discussion of how these finding advances research in informal institutions and EE.

2. Literature review

2.1 Institutions and entrepreneurship

An institutional perspective on entrepreneurship considers the individual–context relationship (Schmutzler et al., Citation2019). According to North (Citation1990), institutions are the rules of the game that shape human interaction and include both formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions are related to constitutions, laws, property rights, economic rules, and contracts and informal institutions include taboos, customs, traditions and conducting codes, which are socially transmitted and are part of the ‘heritage we call culture’ (North, Citation1990, p. 37). Although an informal institution is not formally established, it certainly conditions people’s behaviour, functioning as a well-understood ‘rule’ among people in a particular context. Applying this informal institutional perspective to the study of EEs is necessary to increase our understanding of this phenomenon, but it has been previously under-researched (Borissenko & Boschma, Citation2017).

2.2 Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

The concept of EE has gained popularity among (regional) economic development studies. Yet, it still lacks strong theoretical foundations (Neumeyer & Corbett, Citation2017), although recent contributions are advancing the field (e.g., Wurth et al., Citation2021). An EE is generally understood as ‘a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship within a particular territory’ (Stam & Spigel, Citation2016, p. 1) and according to Spigel (Citation2017) comprise cultural, social, and material attributes that provide benefits and resources to entrepreneurs within a territory.

Cultural attributes refer to the underlying beliefs and perspectives about entrepreneurship. Social attributes are defined as resources available through existing networks. Finally, the material attributes refer to tangible resources that support entrepreneurship (see ).

Table 1. Ecosystem attributes according to Spigel (Citation2017).

2.3 Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and institutions

Informal institutions already studied in the EE literature include the supportiveness of the entrepreneurial environment (Stam, Citation2015), the population’s perception of entrepreneurship (Spigel, Citation2016), and risk tolerance or fear of failure (Neck et al., Citation2004). This paper goes beyond these to suggest that informal institutions attached to people’s behaviour, although not directly related to entrepreneurship support per se, may influence the functioning of an EE. Thus, deeper and more contextual analyses are needed. Additionally, empirical studies of EEs have mainly been located in developed economies (Pugh et al., Citation2021) with only a few exceptions (e.g., Porras-Paez & Schmutzler, Citation2019). Those studies conducted in emerging economies suggest some differences in EEs. Emerging economies may have a set of inadequacies (Manimala & Wasdani, Citation2015), likely also present in other resource-scarce settings. In such contexts, informal institutions could affect entrepreneurial activity more than formal institutions (Valdez & Richardson, Citation2013), warranting a deeper analysis of these contexts.

3. Methodology & case study overview

This paper relies on a qualitative methodology and explores the EE of a coastal region – the Department of Atlántico in Colombia. Geographically and administratively Colombia is divided into 32 departments and according to the last report of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Colombia ranks fourth world-wide for total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) (Bosma et al., Citation2021).

According to Motoyama and Knowlton (Citation2016), understanding of EEs would expand if academics explored regions with substantial transformations in their entrepreneurial scene; clearly Colombian regions provide interesting case studies due to their burgeoning entrepreneurial activities. Although the economic development of Barranquilla – the department’s capital – has been lagging behind for a long time (Aguilera-Díaz et al., Citation2017), the city recently obtained the ‘Startup Nations Award for Local Policy Leadership’ (Mouthón, Citation2016) and it has one of the four most developed EEs in Colombia (StartupBlink, Citation2019). In cultural terms, Barranquilla’s Carnival is a renowned festival considered as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity since 2003 (Cabrera et al., Citation2020). The region is also well known for soccer (Cure, Citation2017) and music; the nation’s soccer games are played here and Shakira, an internationally renowned artist, is part of Barranquilla’s identity (Esparragoza et al., Citation2020).

The case study methodology was chosen due to its relevance in addressing ‘how?’ and ‘why?’ questions, and its suitable frame for the regional delimitation of the study (Yin, Citation2009). Data collection consisted of three phases: (1) secondary information analysis to identify the existence of an EE, and its actors and roles; (2) direct participant observation, attending 11 entrepreneurship events (July 2017–November 2018), plus 60 audios (24 h of recording) of public talks and debates; (3) 38 semi-structured interviews with 25 entrepreneurs and 13 actors. These phases initiated sequentially, but turned into an iterative process as is natural in qualitative studies (Coller Porta, Citation2005). Entrepreneurs and actors were chosen based on their ecosystem participation (in the events) and sampling was increased by snowball methods until saturation. and detail the sample specifications. Secondary data of national and local socioeconomic reports, news and social media complemented the research.

Table 2. Characteristics of interviewed entrepreneurs.

Throughout the observation phase, the attitude ‘take it easy’ (in Spanish ‘cógela suave’) was identified as a relevant informal institution. Thus, interviewees were asked about their perceptions of this phrase. All collected data were transcribed and the software Nvivo was used for content analysis: data were categorised, labelled (interviews with entrepreneurs were labelled as e.g., E101; interviews with actors were labelled as e.g., A101), and coded according to themes (Cope, Citation2005) guided by the research question. In the analysis, the existence of an informal institution called ‘take it easy’ was confirmed and further explored in the data to understand its meaning and layers. Subsequently, data were analysed to identify both negative and positive implications on the EE and its attributes.

Table 3. Roles of 13 interviewed actors.

4. Data and findings

4.1 Positive and negative elements of ‘take it easy’

‘Take it easy’ was identified as an informal institution of the Colombian Caribbean where the Atlántico’s EE is located, ‘because of the idiosyncrasy, because of the heat […], we have a smoother pace’ (E105). The phrase emerged consistently from the data and was a key theme. ‘Take it easy’ refers mainly to taking things calmly, but also directly connects to the cultural heritage and carnivals that characterise this region: ‘The Barranquillero [person from Barranquilla] is not lazy, […] but here people are thinking about music, parties and carnivals’ (E116). ‘Take it easy’ is also an invitation to live and share the local customs, the way and rhythm of life, the cultural and natural richness, and the joyful way of communicating (Consuegra, Citation2019).

Moreover, ‘take it easy’ is an attitude that helps to manage awkward or tense situations but it reflects the cultural tendency to avoid conflict and difficulty saying ‘no’ that was identified as a regional characteristic relevant to entrepreneurship: ‘People cannot say no, they feel uncomfortable […], as if they were afraid of offending others’ (A101). ‘We have the culture of conflict avoidance, many people say “Oh, great, call me … ” Instead of saying “you know what? This does not seem interesting to me”. So, people think it is “take it easy”’ (A111).

Taking things calmly is often-times viewed as positive: ‘As we do not worry so much, we live a happier life. […] It is like things will flow, […] let’s enjoy’ (E114). This is seen as having benefits for quality of life: ‘I think take it easy is very good for certain scenarios that maybe we do not have it in the interior [of Colombia], there the quality of life is terrible, I have quality of life here’ (E109).

Yet, there is also a negative side, it is seen to affect productivity: ‘It’s good because people here are happy, positive, friendly, more relax, which is good for business […] Now it has the other side, which is not so good, it makes everything slower, and with less quality’ (A101).

Valuable time is wasted: ‘There is a Japanese who said that we work 10 h, but we work 3 out of 10, because we get distracted too much and it’s certainly true’ (E118).

Some entrepreneurs recognised leisure has more power than productivity: ‘I feel that here on the coast […] life focuses more on leisure, on entertainment rather than on growth itself. Growth, as a means to an end (leisure), not as an end in itself … ’ (E105).

‘Take it easy’ could be one of the reasons why non-local entrepreneurs (who perhaps don’t take it so easy) have taken advantage of the local market:

You go to the center of the city, where merchandise is distributed for selling and it is full of ‘paisas’ [people from the department of Antioquia] […]. So, one may ask, why did they have to come? […], I feel we have stayed behind (E108).

Clearly, the influence of ‘take it easy’ culture in Atlántico has an ambiguous impact on the EE, with some elements seen as a strength, and others as an obstacle.

Entrepreneurs adapt to the ‘take it easy’ culture by adopting particular strategies:

It’s about work styles, […] if you go somewhere, you adapt yourself to it, or if people come here also adapt themselves, but as an entrepreneur, you must be open […] so your processes can flow (A109).

4.2 ‘Take it easy’ influencing the wider EE

Beyond analysing how ‘take it easy’ affects entrepreneurs, it is important to consider how it affects wider EE attributes. In this section, following the categories presented in , the cultural, social and material influence of ‘take it easy’ on EE development is considered.

Regarding the cultural attributes, ‘take it easy’ influences the underlying beliefs and outlooks about entrepreneurship. The level of innovation is seen as quite low, which can be a constraint but also an opportunity in the sense that the barriers are quite low for innovative entrepreneurs: ‘to be innovative in the Caribbean is to do things well and on time […], we are in such a basic industry’ (A111).

Entrepreneurs could also be seen as ‘workaholics’:

When I came here and opened the company, I remember, I came to work at 7 am and left at 8 pm. That was my work rhythm and I had problems with some people that I started to hire who said, ‘hey calm down, that’s not how it is’ (E105).

Other entrepreneurs shared how they could feel frustrated when they were questioned about their pursuit of entrepreneurial success: ‘[People] tell me: “why do you kill yourself working so much? Who are you going to leave everything you earn?” Look, […] I want to be successful; […] “Take it easy” here pisses me off.’ (E102).

Entrepreneurs recognised they are in a ‘take it easy’ context, and if they identify companies where people ‘take it easy’, they avoid doing business with them: ‘Companies that are doing well do not take it easy. Companies that are not doing well, they probably take it easy, […], you do not usually knock on their doors’ (E113).

With respect to the social attributes, resources such as money and time are seen to be impacted by the ‘take it easy’ culture. Cash flow is affected because debtors and big companies take too much time to pay: ‘[Debtors say] “Don’t worry, I’ll pay in a month” […] How […]? I needed that money’ (E109). ‘Always something happens […]. Big companies pay within 120 days. They use you […], is complicated’ (E118).

Time, a valuable resource rarely discussed in EE literature, is also negatively impacted: ‘The standard sometimes is ‘I will do it later’, so yes, there is a little bit of that culture of being more flexible with time’ (A111).

Time is perceived to be wasted on a daily basis:

Here in Barranquilla you go to a meeting and it lasts two hours: an hour talking about nothing, […] and another hour talking about the topic of the meeting […], in Bogotá you go to meeting and is 45 min (E114).

5. Discussion: ‘take it easy’ – a double edged informal institution

EE development is susceptible to the interplay between informal rules, such as culture, and individual agency (Spigel, Citation2016). Due to the embeddedness of an EE where individuals are tied to the environment (Jack & Anderson, Citation2002) and with human interaction being key for an EE’s functioning (Motoyoma & Knowlton, Citation2016), institutional context influences both the EE and the individual agents interacting within the EE, whose behaviour will eventually reproduce the ecosystem.

As an informal institution, ‘take it easy’ shapes human interaction in the Colombian Caribbean. ‘Take it easy’ is analysed in this paper to unpack the way in which the often intangible and hidden elements of informal institutions and culture not related directly to entrepreneurship support impact the functioning of an EE. Contrary to expectations, ‘take it easy’ does not refer to laziness; rather, it refers to taking things calmly while also including conflict avoidance and an a preference for entertainment, exerting both positive and negative influences on entrepreneurs themselves and the wider EE, as evidenced by data. There is a suggestion that this culture can lead to less anxiety and better quality of life (Piedra et al., Citation2022) but it is also seen to be a problem that people may prioritise leisure, parties, soccer games and holidays over growth and productivity. Conflict avoidance is also highlighted as difficulties in ‘saying no’, which can result in non-compliance with promises and commitments.

The impact on the region’s EE of this informal institution has two sides: On the negative side, it slows down processes, reduces productivity, lowers the quality of products or services, and increases the risk of hiring inefficient employees. ‘Take it easy’ is sometimes seen as hindering the EE’s progress, leading to a general trend whereby the potential of human capital in the region is not realised. Cultural aspects are often seen as obstructing entrepreneurial and innovative progress. However, for the local culture ‘take it easy’ does not mean wasting time or living in a perpetual Carnival. On the contrary, the positive side of ‘Take it easy’ enables a nuancing of awkward situations, it is a stress softener and makes people more relaxed, friendly, happier and positive; it is instead a unique way to balance life that stimulates creativity and imagination (Consuegra, Citation2019) which has a positive impact on business. Thus, we can see that ‘take it easy’ has an ambiguous influence on the EEs of Atlántico, defying dichotomic narratives of good or bad.

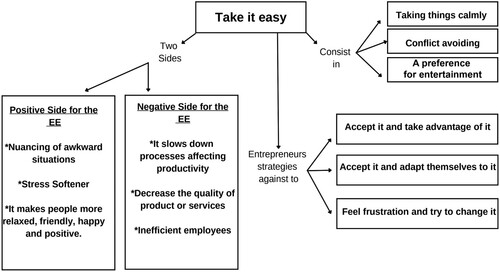

Entrepreneurs develop different strategies to deal with ‘take it easy’: some accept it and take advantage of it, others accept it and adapt themselves to it, and others feel frustration and try to change it. Whilst being embedded in a ‘take it easy’ context, the research shows that entrepreneurs in fact rarely take it easy. Non-local entrepreneurs have taken advantage of this culture, managing to capture market segments through their higher productivity. However, non-local entrepreneurs tend to feel frustration confronting ‘take it easy’, as they have experienced doing business in contexts where things may flow faster. Entrepreneurs know they must make an extraordinary effort to change the mindset of their talent to focus on growth and productivity and at the same time understand the local lifestyle and adapt to this cultural condition to contribute to the quality of life. As such, navigating ‘take it easy’ culture is a balancing act that entrepreneurs in Atlántico must handle. By having a negative and positive sides, this informal institution acts as two opposing forces that impact the EE, perhaps making it difficult for the EE to advance. summarises this research, illustrating the complexities around how ‘take it easy’ is understood and its implications for the EE and entrepreneurs.

Figure 1. The informal institution of ‘take it easy’. Summary of three ‘Take it easy’ fundamental aspects. First, what it consists of; second, the two sides (positive/negative) and third, the strategies that entrepreneurs use against this informal institution.

Considering the composition of EE and the results of this study, several implications emerge according to the ecosystem attributes defined by Spigel (Citation2017). illustrates how this study of ‘take it easy’ as an informal regional institution advances our understanding of how informal institutions impact EE development and functioning along the nexus of cultural, social and material attributes.

Table 4. Ecosystem attributes and informal institutions.

This paper illustrates how localised culture not directly related to entrepreneurship influences the entrepreneurial process (Vaillant & Lafuente, Citation2007). Depending on its nature each informal institution can act as driver or barrier to entrepreneurship or even both. This analysis uncovered that informal institutions influence the underlying beliefs and outlooks about entrepreneurship within the EE. We can see this in the tensions between entrepreneurs getting frustrated about things moving slowly, or employees being unproductive and people questioning entrepreneurs as ‘workaholics’. A clear disconnect emerges between entrepreneurs (who do not take it easy as a general rule) and the EE context they sit within which values and normalises such behaviour. Informal institutions belong to cultural attributes which according to Spigel (Citation2017, p. 7) ‘create a context through which supportive social attributes can emerge’. This could include worker talent, networks and knowledge and research flow, which could be dynamised or delayed by informal institutions. Informal institutions could facilitate (or inhibit) coordination, trust-building, and knowledge-sharing among economic actors and enterprises (Lowe & Feldman, Citation2017). EE actors need always to be aware of local institutional context to make sure their actions will be effective. In addition, research findings show that resources such as money and time are the most affected by ‘take it easy’. Payment delays have an impact on entrepreneurs’ cash flow. Time, a valuable resource that is rarely discussed in EE literature, is wasted, affecting the EE dynamic.

Third, the material attributes – such as universities, support services, policy and governance, and open markets – are influenced by their staff behaviour. Human agency attitudes within EE support organisations may be shaped by informal institutions, but also they can act as agents of institutional transformation (Hatch, Citation2014). Depending on the nature of informal institutions, entrepreneurs can experience them differently, which can result in a variety of attitudes and strategies towards each institution. ‘Take it easy’ marks a context-specific life and work style that can slow down the dynamics inside support organisations. ‘Take it easy’ can impact productivity in terms of functioning of the wider EE, not only in business terms, but also in the ability of EE actors to push the system forwards.

6. Conclusions

This paper contributes to the understanding of an EE as a socioeconomic structure embedded in a specific institutional context and examines how an informal institution impacts an EE via specific regional culture. In particular, this paper shows how an informal institution that is not directly related to entrepreneurship support can nevertheless shape entrepreneurial processes. Depending on the context and the informal institution, this influence can be positive, negative or both. Specifically, existing within the wider ecosystem, informal cultural institutions will also impact social and material attributes, by affecting network dynamism and accelerating or delaying the flow of resources.

Policymakers should be aware of how informal institutions affect entrepreneurial activity and address their actions to improve the ecosystem not only through financial strategies but including initiatives towards socio-cultural impact, positively influencing institutional conditions. If policymakers can understand institutional context better, and how this impacts EE functioning and development, considering the idiosyncrasy that each place has, policies could be adapted to fit better within different EE contexts. Also, problematic practices of importing entrepreneurship policies from developed economies with completely different institutional scenarios can be diminished through a better understanding of local culture.

While the notion to ‘take it easy’ could be considered specific to this case study, the notion that informal institutions not directly related to entrepreneurship support affect EE performance could apply to any context. Future research focused on the recognition of how informal institutions affect EE in different contexts, and how diverse types of entrepreneurs and actors experience them, is needed to increase the understanding of the shaping effect of institutional context to EE.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Ács, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016

- Aguilera-Díaz, M. M., Reina-Aranza, Y. C., Orozco-Gallo, A. J., Vega, J. Y., & Barcos-Robles, R. (2017). Evolución socioeconómica de la región Caribe colombiana entre 1997 y 2017. Documentos de Trabajo Sobre Economía Regional y Urbana; No. 258.

- Borissenko, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: towards a future research agenda. Papers in innovation studies, (2017/03).

- Bosma, N., Hill, S., Ionescu-Somers, A., Kelley, D., Guerrero, M., Schott, T., & The Global Entrepreneurship Research Association (GERA). (2021). 2020/2021 Global Report. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-20202021-global-report.

- Cabrera, K. I., Montenegro, Y. A. y., & Cabrera, E. F. (2020). Protección del patrimonio cultural inmaterial a través de la Propiedad intelectual: el caso del Carnaval de Barranquilla. Revista La Propiedad Inmaterial, 49–72. https://doi.org/10.18601/16571959.n30.02

- Coller Porta, X. (2005). Estudio de casos. Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

- Consuegra, J. (2019). ¡Cógela Suave!. El Heraldo. https://www.elheraldo.co/columnas-de-opinion/jose-consuegra/cogela-suave-642542.

- Cope, M. (2005). Coding qualitative data. In I. Hay (Ed.), Qualitative research methods in human geography (pp. 223–233). Oxford University Press.

- Cure, C. C. (2017). Barranquilla, la casa de todos. Revista Colombiana De Endocrinología, Diabetes & Metabolismo, 4(2), 4. https://doi.org/10.53853/encr.4.2.111

- Esparragoza, D. J., Díaz, D. J. M., & Guerra, H. S. (2020). Identificación y apropiación de los signos identitarios de la marca barranquilla en jóvenes universitarios. Dictamen Libre, 27, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.18041/2619-4244/dl.27.6648

- Hatch, C. J. (2014). Geographies of production: The institutional foundations of a design-intensive manufacturing strategy. Geography Compass, 8(9), 677–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12158

- Jack, S. L., & Anderson, A. R. (2002). The effects of embeddedness on the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 17(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3

- Lowe, N. J., & Feldman, M. P. (2017). Institutional life within an entrepreneurial region. Geography Compass, 11(3), e12306. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12306

- Manimala, M. J., & Wasdani, K. P. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystem in emerging economies. Springer.

- Motoyama, Y., & Knowlton, K. (2016). Examining the connections within the startup ecosystem: A case study of St. Louis. Entrepreneurial Research Journal, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2498226

- Mouthón, L. (2016). Cámara de Comercio de Barranquilla gana premio mundial de emprendimiento. El Heraldo, 19 November, 16.

- Neck, H. M., Meyer, G. D., Cohen, B., & Corbett, A. C. (2004). An entrepreneurial system view of New venture creation. Journal Of Small Business Management, 42(2), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2004.00105.x

- Neumeyer, X., & Corbett, A. C. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems: Weak metaphor or genuine concept?. In D. F. Kuratko & S. Hoskinson (Eds.), The great debates in entrepreneurship (pp. 35–45). Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Piedra, L. M., Howe, M. J., Ridings, J., Montoya, Y., & Conrad, K. J. (2022). Convivir (to coexist) and other insights: Results from the positive aging for Latinos study. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(5), 1421–1434. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211069269

- Porras-Paez, A., & Schmutzler, J. (2019). Orchestrating an entrepreneurial ecosystem in an emerging country: The lead actor’s role from a social capital perspective. Local Economy, 34(8), 767–786. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094219896269

- Pugh, R., Schmutzler, J., & Tsvetkova, A. (2021). Taking the systems approaches out of their comfort zones: Perspectives from under explored contexts. Growth and Change, 52(2), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12510

- Roundy, P. T. (2017). Hybrid organizations and the logics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0452-9

- Schmutzler, J., Andonova, V., & Diaz-Serrano, L. (2019). How context shapes entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a driver of entrepreneurial intentions: A multilevel approach. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(5), 880–920. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717753142

- Spigel, B. (2016). Developing and governing entrepreneurial ecosystems: The structure of entrepreneurial support programs in Edinburgh, Scotland. International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, 7(2), 17–19. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJIRD.2016.077889

- Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12167

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769.

- Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2016). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy. In R. Blackburn, D. de Clercq, J. Heinoen, & Z. Wang (Eds.), Sage handbook for entrepreneurship and small business. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- StartupBlink. (2019). Startup ecosystem rankings 2019.

- Vaillant, Y., & Lafuente, E. (2007). Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity? Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(4), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701440007

- Valdez, M. E., & Richardson, J. (2013). Institutional determinants of macro-level entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(5), 1149–1175. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12000

- Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x

- Welter, F., & Baker, T. (2021). Moving contexts onto new roads: Clues from other disciplines. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 1154–1175. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720930996

- Wurth, B., Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2021). Toward an entrepreneurial ecosystem research program. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 46(3), 729–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258721998948

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed). Sage Publications.