ABSTRACT

As a result of the decline of key economic sectors, old industrial towns face several development challenges, reinforcing the perception of these places as peripheral. However, even in the context of old industrial towns in the Ústí nad Labem Region in post-socialist Czechia, local people are addressing locally specific issues to facilitate a positive change. These actors (known as ‘agents of change’) mobilise diverse resources through their actions. This study shows that to build an individual capacity to act, inspiration and knowledge transfer from diverse professional and geographical structures are even more important than formal education. To finance their initiatives, agents use informal investments provided by their friends and family, but later they exploit formal subsidies from the public sector. In terms of social capital, a high-quality collaboration between locals is a crucial factor for change, yet local and regional governments often fail as coordinators and leaders of change agency.

1. INTRODUCTION

Structures, historical preconditions and problems of old industrial regions (OIRs) are often perceived as homogeneous. However, contrary to such perceptions, different rates of apparent success in the transformation of OIRs result in their increasing polarisation (Kinossian, Citation2019). Individual OIRs often face typical development problems, which can also be understood as opportunities and resources enabling ‘change agency’. Change agency is defined as human action to break with existing regional development paths (Grillitsch et al., Citation2019). While Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) and Grillitsch et al. (Citation2019) have provided detailed theoretical discussions of the process of change agency, Blažek and Květoň (Citation2022) and Rekers and Stihl (Citation2021) approached the issue empirically on a regional or a local scale. However, limited attention was paid to the scale of individuals and their change agency supporting the transformation of OIRs. Such individual human agency stands very often at the beginning of the change process and might create new development trajectories and lead to the breakdown of existing structures (Green, Citation2016). Therefore, this study aims to reveal the factors that strengthen individuals’ capacity to implement their own change agency, while considering locally specific characteristics of old industrial towns in the Ústí nad Labem Region.

2. CONCEPTUAL BACKGROUND

2.1. Change agency in OIRs

Although there are many definitions of OIRs, it is generally agreed that OIRs are places where the former economic dynamism driven by key industries has disappeared. Therefore, such regions become peripheral and obsolete in the context of their economic structure (Benneworth & Hospers, Citation2007). The decline of the region and its key industries is then reproduced by a specific institutional setting hindering future change, often labelled as ‘lock-in’ (Grabher, Citation1993), whereby the former industrial specialisation of the region becomes the main obstacle to redevelopment (Trippl & Tödtling, Citation2008).

The wider social structures of OIRs interact constantly with individual agency, and both components shape each other (Giddens, Citation1984). In the context of OIRs, lock-in principles accurately describe regional structures’ path-dependent mechanisms and persistent resistance to change. However, Boschma and Frenken (Citation2018) note that if new combinations of regional and extra-regional industries and resources (e.g., knowledge, skills, institutions and material assets) appear, it is possible to break from old development paths and adopt new ways that can still be related to the former industrial specialisation of the region (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006).

The term ‘change agency’ refers to the transformative processes shaping the existing structures of OIRs, while forging new regional development paths (Grillitsch et al., Citation2019). In this study, we focus on human agents of change whose presence and characteristics are crucial. The transformation of a regional development path is more likely to succeed if the agents are affected by some kind of impulse. Even a crisis might turn into a window of opportunity (Boschma, Citation1997) or opportunity space. However, such spaces only open under specific conditions which tend to vary in time and space as they depend on the different conditions of each region and the capabilities and imaginative capacity of agents therein (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020).

2.2. The role of human and social capital in seizing opportunities for change

Regional structures, including formal and informal institutions and geographical characteristics, are important factors that enable or hinder change. However, the capacity of local agents to recognise and exploit these locally specific characteristics and opportunities seems to be key (Rekers & Stihl, Citation2021). Therefore, the mere existence of a window of opportunity is not enough, because the ability to take these opportunities also depends on the quantity and quality of human and social capital of agents of change.

Human capital refers to not only personal characteristics such as knowledge, skills and experience, but also more innate properties, such as flexibility, creativity and motivation (Maskell & Malmberg, Citation1999). Social capital consists of mutual trust, the quality of social networks and individuals’ ability to move within specific social networks, norms and values (Bourdieu, Citation1986). Embeddedness might be considered a specific kind of networking within a given region. A high level of embeddedness corresponds to a higher quality of interactions between agents. This, in turn, improves information transfer, trust and, eventually, the development of the locality or the region (Asheim, Citation2002). However, too intensive and isolated contacts within a single region can lead to lock-in situations. Therefore, to increase the change potential, regions and agents should remain open to external knowledge (Putnam, Citation1995). Both forms of capital can, therefore, be understood as agent-specific assets that can be potentially mobilised for any action but cannot be interpreted directly as resources that the individual uses for change agency itself. As resources we can understand various means of achieving specific goals or satisfying particular needs, or assets that facilitate certain actions and enable individuals to pursue their time- and locally specific goals (Bourdieu, Citation1986).

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Study areas

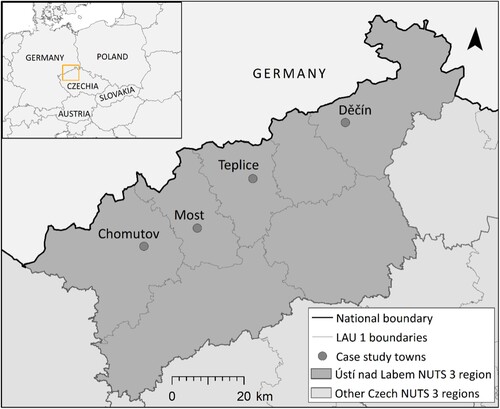

This study focuses on four old industrial towns in the Ústí nad Labem Region (NUTS-III) in Czechia: Chomutov, Most, Teplice and Děčín (). These towns have a similar population size (47,000–63,000) and the same status as district capitals. Until recently, heavy industry has been the main driver of their economies. Chomutov, Most and Teplice were dependent on lignite mining, while Chomutov combined mining and energy industries and non-ferrous metallurgy. The local economy of Děčín was traditionally based on the textile industry and metallurgy, whereas Teplice relied on the glass industry and spa services. The decline of these key industries launched by the post-socialist economic restructuring during the 1990s caused economic problems (e.g., a lack of qualified jobs), social problems (social exclusion and community disintegration; lack of cultural, leisure and social activities) and environmental problems (e.g., urban decay and the presence of brownfields). In particular, owing to its continued dependence on lignite mining and consumption, the region is one of the targets of the Just Transition Mechanism (European Commission, Citation2021), which aims to address the social and economic effects of the transition towards a climate-neutral economy of the European Union (EU).

3.2. Data and methodology

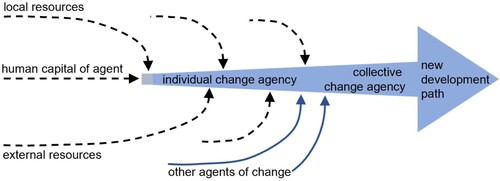

Despite several development problems described above, in all cases identifiable examples of change agency were triggered by local and regional agents of change. The towns investigated do not present clear examples of transition to new industrial development paths as described by Boschma (Citation1997). Rather, local agents of change used individual and collective initiatives (1) to introduce novelty in OIRs or (2) to address problems resulting from the decline of OIRs (). To identify such initiatives, an analytical framework has been developed based on an extensive literature review focusing on the problems of OIRs and defining an ‘ideal state’ by the concept of an innovative/creative milieu (Píša, Citation2022).

Table 1. Criteria for selecting agents of change.

To identify possible agents of change and to understand locally specific conditions, regional newspapers were analysed and 14 semi-structured pilot interviews with local and regional informants (four researchers, five leaders of regional development organisations, two regional journalists, two leaders of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and one local politician) were conducted. Both methods were designed to do the following: (1) to clarify the local specificities of each town; (2) to identify stories that reflect changes according to the criteria presented in ; and (3) to identify the agents of these changes.

To answer the research question below, a further 49 semi-structured interviews with agents of change were conducted. In this study, I am mindful of the role of the public sector in strengthening individuals’ capacity to act. More specifically, I ask the following:

How was the human, social and economic capital of the agent constructed by formal and informal institutions as regards to the knowledge, economic resources and social networks used to implement and operate their initiatives?

Which specific local conditions and institutional settings do agents of change mobilise to implement their initiatives?

The interviewees included innovative entrepreneurs, leaders of NGOs, local politicians, activists and government employees. The interviews were conducted from September 2020 to August 2021. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic and related government measures, almost half of the interviews were conducted online. With the consent of the study participants, the interviews were recorded, taking between 30 and 150 min. Subsequently, the recordings were transcribed and analysed using the thematic analysis method (Hendl, Citation2016).

4. EMPIRICS: RESOURCES LEVERAGED BY AGENTS OF CHANGE

4.1. Knowledge resources

When pursuing their change agency, agents use the knowledge gained in various contexts. To some extent it is linked to the formal education system. However, knowledge acquired through informal channels also appears vital. The interviewees explained that the knowledge that they gained through the traditional education system served only partially as a resource to enact their initiatives. An exception here was the initiatives of NGOs aiming at social inclusion because formal (university) education is a necessary legal condition for working in such fields.

School education was influential in more general terms in forming the broader worldviews of agents. Regardless of the type of agency, the knowledge and skills used are incremental and dependent on the previous experience of individual agents. Very often, such knowledge is influenced by experience from other spatial structures (internships and studies in other regions) and sectoral structures (previous employment, business and leisure activities). For example, an innovative information technology (IT) entrepreneur from Děčín built on the work experience he gained in Silicon Valley and New York, stating:

It’s definitely not just an item in my CV or something […] but it gave me a lot because thinking about doing business there is, in many ways, completely different. So, I learnt a lot there. When I came back, I said that a year in America gave me as much as 10 years of doing business in Czechia.

As well as more formal education and experience, respondents cite the actions of extra-regional agents and active and influential local agents who showed that various forms of change agency are possible even in the OIRs. These observations served as inspiration for their own projects.

Respondents often act as initiators of investigated activities, but lack the expertise necessary to carry them out. For this reason, for example, respondents from the rank of entrepreneurs hire experts from different regions and foreign countries to bring new skills to OIRs and to diversify the local economy, by combining regional industrial traditions with imported knowledge. This was the case of an army equipment factory in Děčín, where workers’ skills gained in the traditional regional textile industry were combined with the high-tech knowledge of foreign military technology experts. However, the ability to attract such skilled migrants here was limited largely by the negative image of the OIR. At the same time, although wages in innovative sectors are well above the average regional wages, they still lag behind the wages in metropolitan areas, particularly in Prague, leading to yet more barriers to recruitment.

Other agents of change highlight the importance of the combination of knowledge obtained informally from their co-workers and skills from outside the organisation (and usually the region) shared through more formal routes (such as training and staff exchanges). Anyway, agents’ knowledge, important for any type of initiative, was derived from various forms of collective learning. The dominant source of knowledge, however, is personal, informally acquired experience accumulated during an agent’s life.

4.2. Economic resources

Money is an essential resource that, to some extent, influences the creation and progress of any initiative by respondents. To avoid risks arising from the use of external sources, agents active in small, non-profit (e.g., community building) initiatives usually used economic resources they had accumulated through their own efforts. Agents from the ranks of entrepreneurs, in contrast, more often combined these resources with formal sources such as subsidies and loans.

In several interviews, the scope of the initiative under investigation directly overlapped the work or business activity of the agents. For most interview partners, however, this initiative was supplemental to their economic activity or was a project that the agents pursued in their free time using finances earned from their primary source of income. Sourcing money was also heavily dependent on various forms of cooperation and coordination between investigated agents of change and other actors and organisations. At the start of any initiative, usually, more stakeholders were connected via informal relationships with family and friends who also invested their efforts, ideas and financial reserves. As one interviewee stated:

At the beginning, my business partner made a small investment in the firm, but later, we broke up anyway. So, we only had hundreds of thousands [Czech Crowns] in marketing, the web and so on. That was all. We each put one car into it as well. (travel agency founder)

Such investments were often combined with economic income resulting from the initiative identified in this research as change agency or commercial loans and subsidies. We found various ways in which economic resources were leveraged by different agents of change. Leaders of ‘small’ cultural and social initiatives can use local grants provided by community foundations, firms and municipalities. Managers of social services (e.g., social enterprises employing disabled people) use subsidies for investment (e.g., building reconstruction often financed by EU funds) and operating costs are, to a large extent, covered by the state budget if the social service is a part of a state-coordinated social system. These sources are often supplemented by contributions made by the local or regional authority or donations. Entrepreneurs use both EU and state subsidies to cover labour costs (particularly in the case of sheltered jobs), as well as for reskilling employees, launching innovative projects and investing in business premises and equipment. Leaders of political organisations and other supporting organisations use subsidies from the EU and the state for investment projects and hiring the employees needed to coordinate social inclusion activities. Only three respondents mentioned the great potential of large-scale development projects of the Just Transition Mechanism targeting OIRs. The manager of a coal mining company involved in landscape restoration was the only one who expected direct benefits for the initiatives of his company.

Generally, the use of subsidies is highly dependent on the agents’ ability to apply for them. While larger organisations such as bigger firms and universities employ qualified staff to work on project applications, agents from the third sector are unable to use such grants because they are limited in terms of time and their knowledge and concerns about bureaucratic demands.

Thus, at the beginning of a change agency process, we often see personal financial resources or informal support provided by friends and family members contributing to start-up activities. Later, initiatives of agents of change might also benefit from various subsidies, particularly when profit is not an expected result of the activity. This also means that the ability to secure financial resources for any of the initiatives under study is the result of social capital (e.g., position in a social network, quality of relationships) and human capital (e.g., experience of applying for subsidies) of the agent.

4.3. Social resources

Both formal and informal relationships between agents and other actors and institutions can be essential elements of support for the activities examined. In addition to the above-mentioned resources related to economic capital, many non-economic forms of support and coordination with other actors and organisations were identified. While more formalised relationships are essential for the agents of community development, the activities of the business agents are, rather, determined by a combination of these formal contacts and informal links.

Regional development organisations and local authorities (political leaders and top officials) are connected with the agents through more formalised relationships. They may act as coordinators linking individual agents and facilitating access to external resources (such as knowledge and grants), consultants, agency promoters and providers of facilities for individual initiatives (e.g., space and technical equipment). The success of such collaboration is determined by the capabilities, attitudes and willingness of local governments and mutual favour between them and agents of change. As one interviewee stated:

A month ago, new political leadership was formed. Issues that we used to debate in cafes and pubs can now be discussed at the level of the office of the first deputy of the mayor. The shift is extreme because the relationship of the unnamed mayor, [whose electoral term] ended mid-term, to this agenda [urban planning and local development] was, diplomatically speaking, very distant. (urban planning expert commenting on the situation in Děčín)

Additionally, some social ties are less burdened by the power relations between individual partners. Within a limited regional market, agents who can be classified as innovative entrepreneurs are usually unable to find suppliers or customers. Agents, therefore, look for a specific niche in national or international markets. In doing so, they use their own extra-regional social networks or expand their production and range of services in response to the absence of regional suppliers.

There are also several examples of collaborations between the agents of change and educational organisations, such as secondary schools and universities, which are motivated by the need to secure a workforce and develop innovation. Both forms of cooperation are often established through an initial research project supported by the grants described above or coordination with local and regional development organisations (e.g., the chamber of commerce or regional innovation centre). This temporary and purely professional cooperation often develops into informal, long-term relationships between actors.

Initiatives based on civic activism and the promotion of cultural and social life can deepen the relationships between people and places and often depend on the cooperation of several similar agents. These agents get to know each other by participating in the same events. This can lead to the formation of coalitions of agents, which, particularly if they acquire legal status, have more power to change local environments. This is the case of a group of active people in Děčín who founded an association for the restoration of the local chateau, and later some of them reached administrative and political positions, which helped them to obtain subsidies for the restoration and to promote other development activities. Generally, joining local councils is a relatively common strategy used by agents when they disapprove of the attitude or passivity of the political leadership. However, the effects of such decisions are not always positive, as they can exacerbate conflicts between the agents (and their initiatives) and the local political leadership. This illustrates the fact that even the good intentions of agents of change can sometimes have negative consequences. In general, however, developing the social capital of agents, in turn, opens a way to obtain other types of resources, such as knowledge and finance. Moreover, it can also generate other relationships that are important for further change.

4.4. Locally specific resources

All interviewees recognised the negative effects of the deindustrialisation processes and other historical events that have affected the region in the past. Nevertheless, half of the interviewees recognised that specific local and regional characteristics had at least partly facilitated or triggered their initiative. However, the possibility of valorising local specificities depends on a good knowledge of them. Such knowledge is often related to local history, in the form of either a story that can be commercialised or as remnants of traditional industries that can still be exploited. In Teplice, for example, the social and cultural life is much richer than in the other towns because of its spa history, and this is why other related cultural, commercial and social initiatives are created here by agents. In other towns, where the social capital is weaker, agents rely on the material heritage of the industrial era (such as brownfields) or redundant and relatively cheap labour or, they sometimes simply construct new, unrelated cultural initiatives.

Some of the agents of change are motivated to stay in the region as they perceive an opportunity to valorise these specific regional assets or the quality of the local environment. This may seem surprising in the context of OIRs, but the agents interviewed perceived the selected towns as quiet and pleasant places to live, surrounded by an attractive natural environment. They also perceived them as having a high potential for development. Thus, when agents consider the specificities of the selected towns as an important resource, they transform them from a barrier to an opportunity for development.

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

This study makes an important contribution to the concept of change agency. It shifts research attention from the transformation of development paths to the doers of this transformation – the agents of change as individuals. Existing research has already stressed that the development of a region or locality depends on people (Rekers & Stihl, Citation2021), human and social capital (Bourdieu, Citation1986; Maskell & Malmberg, Citation1999) and agent-specific opportunity spaces (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). However, these studies did not analyse in depth how resources constructing the capacity to act are gathered by individuals and mobilised towards change agency.

My results show that the capacity to enact change agency in OIRs stems from a combination of various forms of human capital (e.g., imported knowledge and the capability to use relevant institutions) and economic and social capital (e.g., the transfer of resources from different structures) (Putnam, Citation1995). Contrary to the dominant view, some elements of old industrial structures that have been perceived negatively can be recognised as locally specific resources that stimulate change agency (e.g., the presence of brownfields, cheaper real estate and labour, lack of services and cultural events and weak informal institutions).

The ability of agents to recognise these local specifics and their local embeddedness shape the main motivation for implementing change, which, along with other resources, can act as a driving force for local and regional development. This study finds that changes observed empirically are not triggered by sudden crises or impulses forcing adaptation to new circumstances. Rather, they result from complex deliberations about the resources available and what is feasible at a certain time and place. In terms of creating the potential or conditions for change agency, we draw on the conceptualisation of opportunity spaces (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Personal capabilities (human capital) and various forms of interpersonal relationships (social capital) obtained both within and outside local and regional structures () can be understood as specific examples of agent-specific opportunity spaces that enable the emergence of change agency. According to Martin and Sunley (Citation2006), even at the individual level, change agency seems to be path-dependent: several cases presented followed the life paths of the agents, sometimes even reproducing the historical and industrial tradition of the place. However, the importance of resources drawn upon by agents of change differs according to the specificity of each local case and the agents themselves.

Although this study focuses on individual pioneers of change, it is necessary to recognise that no interviewee was an isolated case of a positive development impact. Instead, agents were embedded in a complex network of relationships that affected the direction and success of local development. Regarding economic resources, ‘small’ agents often suffer from an inability to take advantage of financial incentives offered by local, regional and higher authorities. Therefore, these agents have to find an alternative solution, often consisting of intensive informal cooperation with other agents (loans, external investment, donations and other forms of help) or draw on their multi-structural position when using funds generated by their employment or business activity.

In this context, however, this study finds that local and regional governments and supporting organisations often fail to shape the collective social capital and coordinate initiatives of the agents of change. When local and regional government support for change agency is weak, it can reinforce the existing locked-in situation as described by Trippl and Tödtling (Citation2008). This problem is partly reflected in the setting of the grant schemes designed for the transformation of OIRs (the debate on the Just Transition Mechanism resonated strongly in regional media during the research period). However, planned large-scale projects funded from these sources are likely to lead to the technological upgrade of large, old industrial firms and the support of current powerful actors, rather than to the emergence and development of small-scale initiatives described in this study. In this case, the region will transform of its economic structure to reduce the dependence on fossil fuels, but no real change in power relations between regional actors can be expected.

This brings us to a question and a new challenge for the research on the creation of a new development path in OIRs – how can existing successful individual or collective change agencies be transformed or upgraded into a new development path for the region? What tools are available to public authorities and other development actors? How should these be used to accelerate the pace of the new development path creation?

This research challenge is also related to the following issue. Although interviews showed that local specifics of individual towns are perceived and understood as enabling or limiting factors for agency, it is not possible to assess how slightly different local conditions (such as economic diversity, quality of urban space and local political leadership) affect the number, nature and development impacts of agents of change. Therefore, we can pose another challenge for further research (but partly related to the one above) – how to create in OIRs (particularly at the local level) a stimulating milieu for launching change agency of local inhabitants or attract potential agents of change from other regions?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank the reviewers and my project partners (project: ‘Agents of Change in Old-Industrial Regions in Europe’, Volkswagen Foundation, funding programme ‘Challenges for Europe’) for comments on this paper and inspiring discussions. I also thank the Regional Studies Association (RSA) for its support and the APC fee waiver provided through the early career section of the journal.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Asheim, B. T. (2002). Temporary organisations and spatial embeddedness of learning and knowledge creation. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 84(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2002.00117.x

- Benneworth, P., & Hospers, G. J. (2007). The new economic geography of old industrial regions: Universities as global–local pipelines. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 25(6), 779–802. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0620

- Blažek, J., & Květoň, V. (2022). Towards an integrated framework of agency in regional development: The case of old industrial regions. Regional Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2054976

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2018). Evolutionary economic geography. Oxford University Press.

- Boschma, R. A. (1997). New industries and windows of locational opportunity: A long-term analysis of Belgium. Erdkunde, 51(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.1997.01.02

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In John Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 46–58). Greenwood Press.

- European Commission. (2021). The Just Transition Mechanism: Making sure no one is left behind. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/funding/just-transition-fund_en

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

- Grabher, G.. (1993). The weakness of strong ties; the lock-in of regional development in Ruhr Area. In Gernot Grabher (Ed.), The Embedded Firm; on the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks (pp. 255–277)). Routledge.

- Green, D. (2016). How change happens. Oxford University Press.

- Grillitsch, M., Rekers, J., & Sotarauta, M. (2019). Trinity of change agency: Connecting agency and structure in studies of regional development (No. 2019/12). Lund University, CIRCLE – Center for Innovation, Research and Competences in the Learning Economy.

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hendl, J. (2016). Kvalitativní výzkum: Základní teorie, metody a aplikace. Praha: Kvalitativní výzkum: Základní teorie, metody a aplikace.

- Kinossian, N. (2019). Agents of change in peripheral regions. Baltic Worlds, 61–66.

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Maskell, P., & Malmberg, A. (1999). The competitiveness of firms and regions: ‘ubiquitification’ and the importance of localized learning. European Urban and Regional Studies, 6(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649900600102

- Píša, J. (2022). Agents of change in Ústí nad Labem Region [Doctoral dissertation]. J. E. Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem, Czechia.

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002

- Rekers, J. V., & Stihl, L. (2021). One crisis, one region, two municipalities: The geography of institutions and change agency in regional development paths. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 124, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.05.012

- Trippl, M., & Tödtling, F.. (2008). Cluster renewal in old industrial regions: Continuity or radical change?. In Charlie Karlsson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Cluster Theory (pp. 203–218). Edward Elgar Publishing.