ABSTRACT

This study explores the diverse range of activities undertaken by informal workers and the ways in which these activities can differ in terms of their degree of informality. The methodology is qualitative, based on a case study of mototaxi drivers in Cartagena, Colombia, in order to achieve a more complete description and a holistic analysis of the phenomenon. The paper offers a novel multilevel perspective of informality that encompasses not only legal status but also social and economic aspects, and proposes an integrated approach to understanding informality that accounts for the range of activities undertaken by informal actors.

1. INTRODUCTION

The informal economy plays a significant role in providing employment opportunities and sustaining livelihoods, particularly in developing countries. The literature describes various informality concepts such as an underground, a shadow or a submerged economy that have emerged. The underground economy refers to economic activities that are not reported for tax purposes and thus hidden from the government. These activities can be either illegal or legal (Williams, Citation2008).

However, some activities outside formal and informal institutions lack legal support and social acceptance. These activities form part of what we call renegade economies, which are different from informal economies because they lack legitimacy given by large social groups that support a set of certain standards, values and beliefs. (Webb et al., Citation2009). For the purposes of this paper, the informal economy is defined as the set of illegal but legitimate activities undertaken by actors to exploit sector opportunities outside formal institutions (Webb et al., Citation2009). While these activities are illegal because they are outside formal institutions, they are considered legitimate if their products are legal (Lee & Hung, Citation2014).

Measurement of the level of informality involves considering that enterprises or workers may choose to comply with some institutional expectations while still operating informally. However, there is limited research on how they do so (Shahid et al., Citation2020). Academics recognise the complex relationship between formal and informal levels within individuals, organisations and working relationships (Guha-Khasnobis et al., Citation2006; De Castro et al., Citation2014). In order to better understand this relationship, multilevel approaches are required to measure compliance with formalisation elements such as tax, administrative and labour regulations.

This article takes into account the multifactor approach proposed by Gómez et al. (Citation2020) and Shahid et al. (Citation2020). An integral aspect of this proposal is that it is aimed at measuring the ‘degree of informality’ that an agent may have in the development of its economic activities, according to the operationalisation of economic, legal and social aspects. In this paper, the research questions addressed are as follows: What are the main characteristics of informal workers? How might it be possible to analyse the degree of informality in developing contexts? In order to address this gap, this study focuses on the mototaxi driver taxi sector as a case study to analyse the characteristics and roles of informal workers, and to measure the degrees of informality they may have. The study provides a comprehensive overview of the sector, including its current status and future prospects, which is rapidly growing in Colombia as well as in other developing countries. In particular, the study identified two new contributions: a multifactor perspective of informality, taking into account not only the legal status of activities but also the social and economic aspects of informality; and a more integrated approach to the understanding of informality, which takes into account the diversity of types of informal workers from a developing context.

The article is structured as follows. Next, it provides a conceptual framework that extends the conventional formal–informal dichotomy and provides a multifactorial understanding of informality. It then describes the case and methods used. Finally, the results and discussion, highlighting the different characteristics of mototaxi drivers and the multifactorial analysis, facilitate a comprehensive overview of the different degrees of informality.

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In recent decades, significant research and discussion has focused on the informal economy, and understanding of its levels has greatly progressed beyond the previous limited terminology of the informal sector (Charmes, Citation2012; International Labour Organization (ILO), Citation2002).

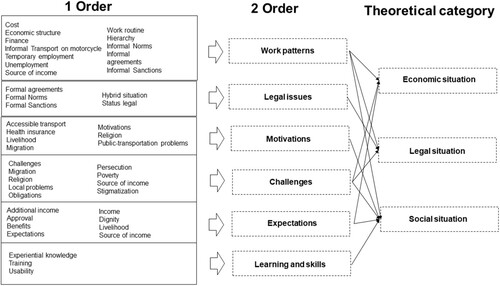

Gómez et al. (Citation2020) propose a multilevel analysis framework to assess the level of formality in entrepreneurs. They used a list of items that evaluate compliance with formal regulations across economic, political and social aspects. These items are assigned scores on a 0–scale, with 10 indicating the highest level of compliance. In contrast, Shahid et al. (Citation2020) propose a four-variable index that measures a company’s level of informality based on legal status, tax registration status, labour registration status and type of accounting, which results in a five-point scale from 0 (totally formal) to 4 (totally informal). This study employs a multilevel approach to understand informality, using an extensive approach proposed by Gómez et al. (Citation2020) which measures the degree of compliance with formal regulations in various aspects such as economic, political and social (). This approach allows for a nuanced understanding of informality and avoids limiting the categorisation of individuals or businesses as solely formal or informal. In addition, the scope of analysis includes the conditions of individuals, groups or associations while incorporating a labour administration indicator to measure the presence of organisational models or behaviour patterns in both their work and means of learning.

Table 1. Degrees of (in)formality.

3. METHODOLOGY

This study employed a qualitative methodology and conducted an in-depth case study. Multiple data collection methods, such as semi-structured interviews, non-participant observation and archival documents, were used to obtain information from different perspectives while developing a comprehensive theoretical model. The data collection took place in several phases over 13 months in Cartagena, Colombia.

3.1. The informal context in Cartagena

In Colombia, official statistics only measure aspects related to the legal perspective of informality. The Colombian National Statistical Office (DANE) employs two surveys, the Great Integrated Household Survey (GEIH) and the National Quality of Life Survey (ENCV), to assess informality. Both methods use affiliation with social security as a criterion for measurement and the legal registration of their businesses (formal sector, informal sector or household) and the nature of employment (formal employment or informal employment).

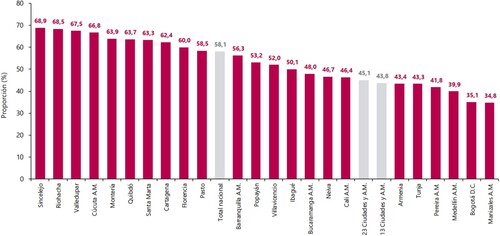

Cartagena is a city with a population of approximately 1,013,389 people and a diverse economy, with prominent sectors such as tourism, industry and logistics. However, as of August 2022, according to data from DANE, 62 out of every 100 individuals employed in Cartagena have informal jobs, lacking social security or a work contract (). There are currently no data concerning the number of mototaxi drivers working in Colombia, including in Cartagena itself.

Figure 1. Proportion of the informal working population.

Source: DANE, Great Integrated Household Survey (GEIH). 2022.

According to regional reports from the Colombian Caribbean coast, the average profile of an individual working as a mototaxi driver is low-economic and has a primary and secondary education. For example, a study on mototaxi drivers in Sincelejo revealed that 90.7% of mototaxi drivers in the city were of socio-economic status 1 and 2, corresponding to the lower level where the population with fewer resources lives; 91.2% were between 14 and 43 years old, and 50% did not finish high school (Brieva et al., Citation2007). Based on the research conducted by Maza et al. (Citation2019), in Cartagena, 55.58% of the 403 surveyed in this informal work were aged 18–34 years old, and in terms of socio-economic status around 50% of workers belong to level 1. Furthermore, the study showed that the majority of mototaxi drivers had a low level of academic training, with only 38.96% of respondents having completed their high-school studies; Moreover, only 11.17% of the studies were technical in nature, 5.46% were in technology areas and 2.23% were university professionals.

The mototaxi driver is an informal phenomenon, and one that can be analysed from multiple perspectives: as a work solution for people with scarce resources or without formal employment; a low-cost service as a practical solution for individuals in remote and inaccessible regions or without access to formal public transportation (Behrens et al., Citation2016); motorcycles are light, fast and easy-to-manoeuvre vehicles, favouring the user who uses this service to travel the route in less time (Cervero, Citation2013); and it is a business opportunity given the ease of buying or renting a motorcycle to use as a work tool (Segovia, Citation2001). Finally, this informal transport service is surrounded by an interplay of actors and interactions that involve not only users and drivers but also those who are motorcycle rental businesses, mechanical workshops, distributors, assemblers and small businesses using them as couriers (Sanchez-Jabba, Citation2011).

3.2. Methods

Multiple data collection methods were used in the research to support the multilevel analysis of the informality. The data collection was conducted in three parts: (1) understanding the phenomenon, (2) fieldwork and (3) search for secondary information. The first part, understanding the phenomenon, involved conducting preliminary interviews with actors in the field to analyse common and representative characteristics of the phenomenon. This preliminary phase began in the last week of April 2019 and lasted approximately three weeks, during which time a total of 12 interviews were conducted in different geographical locations. The second part, fieldwork, began in May 2019 and ended in January 2020. For the selection of the individuals interviewed, criteria such as the characteristics of the work, strategic geographical location, differentiating service patterns, presence and relevance in the discourse of the interviewees were taken into account. Finally, 65 in-depth interviews were conducted during the first and second phases of the fieldwork: mototaxi drivers (54), social leaders of mototaxi drivers (4), traffic control officers – Departamento Administrativo de Tránsito y Transportes (Administrative Department of Transit and Transportation) (DATT) (3), transit police officer (1), social leader of government (1), and two interviews: one with the manager of a shopping centre who had formed a business alliance with a group of motorcycle taxis that operate within the location, and a group leader of entrepreneurs who created an app to offer the informal service.

In addition to primary data collection methods, a secondary data collection effort was also undertaken to further contextualise the findings of the study. A total of 400 documentary pieces, including news articles, were collected, with 199 specifically pertaining to the city of Cartagena. Additionally, seven regional and statistical reports were analysed. A direct observation method was employed in this study to gather information of a real working environment within the informal economy within the transport sector. This method included both overt and covert observations at various physical locations in the sectors of Castellana, 13 de Junio, Olaya, Foco Rojo, Las Gaviotas, La Carolina, Santa Mónica, Zaragocilla, Santa Lucia, La Providencia, Pie de la Popa, Paseo Bolívar and Chambacu. The overt observation involved the actors being aware of the researchers’ presence, while the covert observation was carried out by assuming the role of a user to gain insight into the service provided at different points. The direct observation was conducted over an extended period of time at different worker stations to ensure high levels of immersion.

The data analysis was conducted using the software Atlas.ti, beginning with the transcription of the interviews. In the first-order analysis, 39 codes were generated from the interviews. In the second-order analysis, emerging themes from the fieldwork were used to describe and explain the phenomenon being observed in .

4. RESULTS

4.1. Features of mototaxi drivers

The analysis of the data collected revealed the existence of different subgroups within the mototaxi drivers service, characterised by variations in drivers’ motivations, challenges, expectations, knowledge or skills, and work models. The motivations for mototaxi drivers can be summarised as the need for survival due to lack of employment and the opportunity for autonomy and flexibility in their work. They also establish work patterns, schedules and rules of conduct. The work patterns include ‘roleteo’ and working from fixed ‘stations’ where clients come to them. The schedule varies depending on personalised clients or work areas, with most starting work around 5.00 a.m. and working until nighttime. The rules are common among those who work at the stations and include specific rules of the place, such as location, arrival time, and departure shifts. Challenges faced by mototaxi drivers include restrictions imposed by government and traffic authorities, regulations related to licensing costs and taxes, discrimination, robbery, accidents and exposure to harsh environmental conditions. And finally, expectations include improving working conditions and gaining acceptance in the profession. As previously mentioned, for details, see Table A1 in Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

In conclusion, the mototaxi driver service includes a diverse group of drivers that can be categorised based on their characteristics. These characteristics demonstrate the complexity and nuances present within an informal economy, as they affect the drivers’ work organisation, compliance with standards and economic motivations for pursuing the job.

4.2. Types of mototaxi drivers

The analysis of the data reveals that different types of actors are involved in this informal motorcycle service. It was possible to consolidate two main typologies of drivers: Rebusque drivers and occupation drivers (Vanegas-Chinchilla et al., Citation2023).

Rebusque drivers are temporary workers who work to increase their income or to work temporarily while seeking formal employment to meet their needs, for that, they can be: additional Rebusque is an additional job to increase income, and transitory Rebusque is a survival option when looking for formal jobs in a company:

we can be people with formal jobs and for example we work 8 h, and our salary is not enough … so we take on extra work to make up for the petrol, or for the children’s food, so we work 2–3 h. (ENT048)

This station is one of the most modern, and even when you see an orange helmet, you immediately say he is from the ‘Plazuela’ station, we want people to be safe when we provide services, and want them to feel safe when they take a motorcycle. (ENT007)

4.3. Degrees of informality

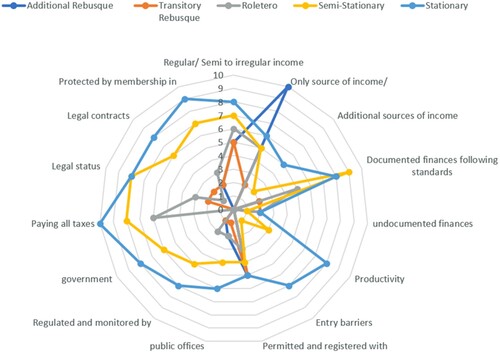

Based on the three factors of economic, legal and social, it is possible to assess the degree of formality for this case by examining the typology of those actors involved. shows that the economic situation highlights the economic conditions of informal motorcycle drivers, noting that some may have irregular income; however, this can improve for those with experience and regular clients. It also differentiates between semi-stationary and stationary drivers, with the latter having more stable incomes and reduced costs. However, it is also mentioned that informal drivers may face restrictions on their mobility within the city, but authorities often recognise their services and relax regulations for the benefit of the community.

Table 2. Economic situation within the degree of (in)formality.

The legal situation discusses the legal perspective of mototaxi drivers, noting that some choose to register their businesses through corporations, foundations or associations (). also illustrates that some drivers opt to pay for their own social security, while others choose to use the state-subsidised healthcare system. Additionally, the drivers are required to pay taxes associated with the use of motorcycles. It also notes that some stationary drivers use legal contracts or verbal agreements with formal actors while others use verbal agreements among drivers.

Table 3. Legal situation in the degree of (in)formality.

In summary, the social situation of informal drivers is driven by the desire to support their households and the opportunity to have a decent job while addressing a transportation need in the city (). Most drivers do not keep separate accounts for their informal activity and household finances, and their management methods vary from searching for customers on the streets to being established in a specific location. Learning is mostly acquired through experience, though in some stations there may be technicians, technologists or professionals who share their knowledge in order to organise the station.

Table 4. Social Situation in the Degree of (In)formality.

The analysis of the informal motorcycle transport sector revealed a range of informality among actors. Assigned scores were based on the presence of formal characteristics within the discourse and narratives of the documents. No formal characteristics resulted in a score of zero, while the presence of more than 10 quotations resulted in a score allocated according to the number of citations. As shown in , stationary and semi-stationary drivers have a lower level of informality compared to other actors.

Figure 3. Degree of (in)formality in mototaxi drivers.

Source: Author’s design.

The degree of (in)formality can vary depending on economic, legal and social factors. Analysis of the discourse and narratives of documents found that stationary drivers and semi-stationary drivers have a lower degree of informality, with practices that bring them closer to formality. On the other hand, drivers such as ‘rebusque’ and ‘roleteros’ have a higher degree of informality. The highest levels of formality in this sector are found in the social situation, where drivers are motivated by a combination of survival and opportunity. These actors may also move through different levels of formality depending on their context. Overall, the analysis revealed different degrees of informality within the same sector.

5. DISCUSSION

The informal sector is characterised by a complex and dynamic environment in which drivers interact with various actors and gain the necessary skills and capacities to be accepted by society. The literature on informality has expanded to include various perspectives and scopes, leading scholars to view it from a more comprehensive perspective, rather than a dichotomous one. This research adopts a multifactor approach, as proposed by Gómez et al. (Citation2020) and Shahid et al. (Citation2020), and includes two additional elements in the indicators associated with the social situation: forms of work administration and learning.

Economic situation plays a significant role in shaping the experiences and income levels of drivers, with some individuals earning regular and additional income while others struggle with irregular income (Charmes, Citation2017; ILO, Citation2013), a characteristic of the informal economy. Legal considerations, such as the lack of government control and non-payment of taxes, also play a role in the informal nature of the sector (Castells & Portes, Citation1989; ILO, Citation2002; La Porta & Shleifer, Citation2014; Chen Citation2012). However, some drivers are able to access social benefits through registered associations, making them more visible to the state. The motivations for participating in the informal economy vary, with some driven by the need for survival (Charmes, Citation2017), while others seek to provide solutions to marginalised populations and increase their income. Furthermore, learning capacities among drivers differ, with those who have acquired experience and knowledge over time being more likely to take on management roles within their group of drivers. Overall, this multidimensional approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of the informal economy and the various factors that shape the experiences of informal workers.

The analysis revealed the involvement of various actors within the informal transport service value chain, including drivers and other economic agents who aim to add value to the service based on market opportunities and needs. In fact, these connections between service providers and other economic agents seek to generate value to the product or service according to market opportunities and needs (Kraemer-Mbula, Citation2016). By analysing the characteristics and roles of informal actors and measuring the degrees of informality they can have, this research provides a more nuanced understanding of informality and its implications for economic and social development.

Informal economy is a complex phenomenon with actors operating at different levels of (in)formality. The analysis of the discourse and narratives of the documents reveals that some drivers have a lower degree of informality, due to their association with formal groups that provide benefits such as legal assistance, agreements and negotiations with authorities. It is important to note that this study has certain limitations that may restrict the generalisability of its findings. Specifically, the study only examined the mototaxi driver sector in a particular region of Colombia. Therefore, there is potential for the multifactor perspective used in this study to be applied to other informal sectors throughout Colombia or other developing countries. Furthermore, additional research is necessary to comprehend how the interrelationships between various types of actors could impact the level of informality and how institutional context might affect these levels. A multifactor approach to comprehending informality can provide valuable insights for the development of public policies that can enhance the abilities of the informal economy, while enhancing working conditions for individuals operating at various levels of formality.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (132.6 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I express my sincere gratitude to the editors and reviewers for their invaluable contributions, insightful feedback and constructive criticism. Additionally, I thank the Bolivar government for the ‘Bolivar Gana con ciencia’ programme that provides opportunities for researchers to make meaningful contributions to society. Its support and investment of scientific research is greatly appreciated.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

REFERENCES

- Behrens, R., McCormick, D., & Mfinanga, D. (2016). An introduction to paratransit in Sub-Saharan African cities. In Paratransit in African cities. Operations, regulation, and reform (pp. 1–25). Routledge.

- Bonner, C., & Spooner, D. (2011). Organizing in the informal economy: A challenge for trade unions. Internationale Politik Und Gesellschaft, 14(2), 87–105. https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/ipg/2011-2/08_a_bonner.pdf

- Brieva, J., Tinoco, U., Restrepo, J., & Arango, L. (2007). El mototaxismo en Sincelejo, un análisis socioeconómico. Observatorio del Mercado de Trabajo en Sucre, conformado por la Cámara de Comercio de Sincelejo, la Corporación Universitaria del Caribe –CECAR-, la Universidad de Sucre, el Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje –SENA con apoyo del Programa REDES del PNUD, la Secretaría de Planeación de la Gobernación de Sucre y FENALCO, (1), 3-22.

- Castells, M., & Portes, A. (1989). World underneath: The origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy. In A. Portes, M. Castells, & L. A. Benton (Eds.), The informal economy: Studies in advanced and less developed countries (pp. 11–37). Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Cervero, R. (2013). Linking urban transport and land use in developing countries. Journal of Transport and Land Use (JTLU), 6(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.5198/jtlu.v6i1.425

- Charmes, J. (2012). The informal economy worldwide: Trends and characteristics. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6(2), 103–132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/097380101200600202

- Charmes, J. (2017). The Informal Economy. Definitions, Size, Contribution and Main Characteristics. The informal economy in developing nations: Hidden engine of innovation, 13–52.

- Chen. (2012). The informal economy: Definitions, theories and policies. In Women in informal economy globalizing and organizing. WIEGO working paper 1, Geneva.

- Danielsson, A. (2016). Reforming and performing the informal economy: Constitutive effects of the World Bank’s anti-informality practices in Kosovo. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 10(2), 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2015.1137393

- De Castro, J. O., Khavul, S., & Bruton, G. D. (2014). Shades of grey: How do informal firms navigate between macro and meso institutional environments? Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8(6), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1172

- Gómez, G. M., Chawla, S., & Fransen, J. (2020). Exploring the entrepreneurial ecosystem within the informal economy with a multifactor framework. In Urban studies and entrepreneurship (pp. 181–202). Springer.

- Guha-Khasnobis, B., Kanbur, R., & Ostrom, E. (2006). Beyond formality and informality. Linking the formal and informal economy: Concepts and policies. In Wider studies in development economics (pp. 75–92). Oxford University Press.

- Hart, K. (1973). Informal income opportunities and urban employment in Ghana. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 11(1), 61–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X00008089

- Hillenkamp, I., Lapeyre, F., & Lemaître, A. (2013). Introduction: Informal economy, vulnerabilities, and popular security-enhancing practices. In I. Hillenkamp, F. Lapeyre, & A. Lemaître (Eds.), Securing livelihoods: Informal economy practices and institutions (pp. 1–22). Oxford University Press.

- ILO. (1972). Employment, incomes and equality. A strategy for increasing productive employment in Kenya. International Labour Organisation.

- ILO. (2002). Decent work and the informal economy. International Labour Office.

- ILO. (2004). Statistical definition of informal employment: Guidelines endorsed by the Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (2003). In International Labour Organization, Geneva ILO (2012) Statistical update on employment in the informal economy (pp. 1–17). Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- ILO. (2013). Transitioning from the informal to the formal economy, ILC/103/v/1-2. International Labour Organization.

- Kabeer, N., Milward, K., & Sudarshan, R. (2013). Organising women workers in the informal economy. Gender & Development, 21(2), 249–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.802145

- Kraemer-Mbula, E. (2016). The informal economy in developing nations: Hidden engine of innovation? (pp. 146–193). Cambridge University Press.

- La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2014). Informality and development. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.28.3.109

- Lee, C. K., & Hung, S. C. (2014). Institutional entrepreneurship in the informal economy: China's Shan-Zhai mobile phones. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 8(1), 16–36.

- Lindell, I. (2010). Informality and collective organizing: Identities, alliances and transnational activism in Africa. Third World Quarterly, 31(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436591003711959

- Maza, F., Fals, M., Espinosa, L., Safar, C., & Licona, D. (2019). Percepciones del riesgo asociado a la práctica del mototaxismo en Cartagena, Colombia. Economía & Región, 13(2), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.32397/er.vol13.n2.2

- Sanchez-Jabba, A. (2011). La economía del mototaxismo: el caso de Sincelejo. Documentos de Trabajo Sobre Economía Regional. Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales (CEER) del Banco de la República. No 140. https://www.banrep.gov.co/es/economia-del-mototaxismo-el-caso-sincelejo

- Segovia, M. (2001). Transporte público en Cartagena: una concentración de iniciativas individuales sin hilo conductor. Serie de Estudios Sobre La Costa Caribe, Serie de estudios sobre la Costa Caribe, Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano, Seccional del Caribe, Departamento de Investigaciones, Cartagena. (No. 16).

- Sethuraman, S. V. (1981). The urban informal sector in developing countries: employment poverty and environment. ILO.

- Shahid, M. S., Williams, C. C., & Martinez, A. (2020). Beyond the formal/informal enterprise dualism: Explaining the level of (in)formality of entrepreneurs. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 21(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465750319896928

- Sindzingre, A. (2006). The relevance of the concepts of formality and informality: A theoretical appraisa. In B. Guha-Khasnobis, S. M. R. Kanbur, & E. Ostrom (Eds.), Linking the formal and informal economy: Concepts and policies (pp. 58–74). Oxford University Press.

- Tokman, V. E. (1982). Unequal development and the absorption of labour: Latin America 1950-1980. Cepal Review, 17, 121–133.

- Vanegas-Chinchilla, N., Schmutzler, J., Porras-Paez, A., & Juliao-Rossi, J. (2023). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in the informal economy? A case study of mototaxi drivers in Colombia. In J. Cunningham (Ed.), Working Paper to be published in research handbook on entrepreneurial ecosystems (pp. 1–33). Edward Elgar.

- Webb, J. W., Tihanyi, L., Ireland, R. D., & Sirmon, D. G. (2009). You say illegal, I say legitimate: Entrepreneurship in the informal economy. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 492–510. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.40632826

- Williams, C. (2008). The hidden enterprise culture: Entrepreneurship in the underground economy. Edward Elgar.