ABSTRACT

The emergence of divergent economic activities in the context of developing economies characterised by institutional voids and market failure is a result of changes in the institutional environment and institutional arrangements. This study provides an inter-temporal framework for understanding the emergence of economic activities, institutional change, path dependence, and spatial economic resilience mediated by continuous and reciprocal interactions between economic and institutional agents (formal and informal) at the micro-level. Co-evolutionary studies of divergent economic activities in the Indian city of Delhi have revealed that radical changes in the institutional environment that did not enable retention of the existing ‘lock-in’ and informal institutional arrangements such as social ties and networks led to institutional drift and path exhaustion for the industrial sector. Meanwhile, in the service sector, the response of economic entrepreneurs to changes in the institutional environment has led to technological lock-in and the emergence of supporting informal institutional arrangements. Formal institutional arrangements have undergone institutional layering that has led to economic path creation for the service sector.

JEL Classifications: B52, E26, R11, O17

1. INTRODUCTION

Building economically resilient cities has taken centre stage in policy discussions, especially following the 2007–08 housing crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic (Zhai & Yue, Citation2022). The literature on spatial economic resilience has delved into the evolution of economic activities using generalised Darwinism theory (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). In contrast, complexity theory emphasises the existence of different populations that co-evolve (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019) with each other. Spatial economic resilience can be understood by undertaking co-evolutionary studies of economic activities and institutions (Matutinović, Citation2007). The interactions between economic and institutional agents and their relative bargaining power play an important role in institutional change (Kingston & Caballero, Citation2009), lock-in and path development. Institutional changes can be radical or incremental, and subsequently economic activities emerge, change and adapt to institutional changes (Grillitsch, Citation2015). In developing economies, change in economic activities is contingent upon the interactions between economic agents and the agents of informal institutions (Sjöstedt, Citation2015) since co-evolution is rooted in the socio-economic context (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014). A causal link between institutional change, economic path development and the economic resilience of cities using the co-evolutionary framework was proposed by Hu and Yang (Citation2019). However, the role of informal institutional arrangements was not established.

This paper makes the following key contributions. First, it provides a framework for carrying out co-evolutionary studies (inter-temporal) of radical and incremental changes in the institutional environment and institutional arrangements. The framework provides a proposal for the causal link between the co-evolution of institutions (formal and informal) and economic activities, institutional change, path development and spatial economic resilience. Second, it fills a gap in the literature on complexity theory by exploring the role of institutional (formal and informal) and economic agents in mediating institutional changes by undertaking co-evolutionary studies in the case study areas.

The paper is organised as follows. The next section discusses the theoretical underpinnings of generalised Darwinism, complexity theory and co-evolutionary studies. The third section discusses institutional changes, agency issues, path dependence and lock-in. The fourth section discusses spatial economic resilience in the context of co-evolutionary studies. The fifth section proposes a theoretical framework for inter-temporal evolutionary studies. The sixth section discusses the case study and the final section concludes.

2. GENERALISED DARWINISM, COMPLEXITY THEORY, CO-EVOLUTION

The failure of neo-classical economics to acknowledge the role of history and institutions has led to the emergence of evolutionary economics literature. As per the theory of generalised Darwinism (Aldrich et al., Citation2008; Essletzbichler & Rigby, Citation2007), the concepts of evolution, that is, variety, selection and continuity, can be applied to understand the advent and sustenance of economic activities (Breslin, Citation2011; Hodgson, Citation2002; Hodgson & Knudsen, Citation2006). The non-applicability of the basic assumptions of neo-classical economics, such as the rationality of individuals, incentivises firms to experiment with variety. The bounded rationality of transactors incentivises firms to innovate and introduce new products to gain competitive advantage and earn positive economic profits (Bergh & Stagl, Citation2003). In the process, firms develop new routines, create knowledge, build new contractual relationships and generate the institutional inertia needed for survival in a competitive market environment. The sustainability of firms in the market is determined by the ‘selection’ process. ‘Selection’ is not contingent on firms’ efficiency and productivity but rather on various other factors including the local market environment, social norms, and rules and regulations (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009). After selection, firms bring order to economic activities by ‘self-reinforcing’ routines to ensure ‘continuity’ (Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013). However, while this theory explains the one-way evolution of economic activities in a competitive environment, it does not explain how the environment itself is evolving (Hassink et al., Citation2018). In contrast, complexity theory advocates the existence of a complex, that is, mutual, continuous and reciprocal, relationship between the environment and economic activities (Martin & Sunley, Citation2007; McGlade & Garnsey, Citation2006), which determines evolution and economic path development. The environment is chiefly composed of overarching institutions that reduce uncertainty during economic transactions. In the context of spaces, evolutionary economic geography (Mavros et al., Citation2016) emphasises that co-evolutionary studies can be conducted to understand the complex relationships between economic activities and institutions (Grillitsch, Citation2015; Schamp, Citation2010) since path dependence and lock-in are highly contextual (Simmie & Martin, Citation2010). The next section discusses the impact of the institutional environment, formal and informal institutions, and agency issues on facilitating economic transactions.

3. INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES

Institutions are defined as entities that fashion behaviour such as norms, routines, rituals and shared expectations (Edquist, Citation1997). They are viewed as organisations with a formal structure (North, Citation1990) and as formal rules, regulations and laws that shape behaviour (Gertler, Citation2010). In the evolutionary game theoretic framework, institutions emerge as a ‘stable equilibrium’. Markets as institutions furnish socially optimal outcomes under the conditions of perfect competition (Henning et al., Citation2013). Institutions regulate agent behaviour through the coordination of mutual expectations (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014). Markets in developing economies are far from perfect and are characterised by institutional voids (Ivy & Perényi, Citation2020). As such, informal institutions emerge to deal with issues such as the uncertainty of transactions and market failure (Evenhuis & Dawley, Citation2017). The causes of this failure include price negotiation, lack of access to formal-sector credit, lack of information about the quality of products and relationship-based market exchanges (Gerry, Citation1987). The spatial manifestation of such institutions can be observed as informality in the shape of non-compliance and non-enforcement wherein non-conforming use activities, unauthorised construction and mixed land uses emerge (Anderson, Citation2010).

The role of institutions can be differentiated at different scales. At the macro/aggregate level, they provide a set of structures, namely an institutional environment, for example, capitalism, socialism and communism (Evenhuis, Citation2017). The institutional environment shapes the micro-level institutions, also known as institutional arrangements (Brie & Stölting, Citation2012; Henisz, Citation2000). These refer to various organisational forms, rules, regulations, procedures and routines. Formal institutional arrangements comprise market institutions such as quality assurance, labour unions and trading systems, while governance institutions include rules, regulations, policies, and the public and private sectors (Bergh & Stagl, Citation2003; Evenhuis, Citation2017). Informal institutional arrangements are rules formulated based on experience, culture and values that impact the subjective perception of the economic agents (Brie & Stölting, Citation2012). Such arrangements are dyadic (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2011), highly localised and place specific. Economic agents develop habits and skills at the individual/micro-level and organisational routines at the network/group level under the aegis of institutional arrangements (Stam, Citation2007). The routines lead to path dependence and different kinds of lock-in, namely functional, political and cognitive (Grabher, Citation1993; Martin & Sunley, Citation2008 ). The causes of path dependence at the spatial level are high sunk costs, the quasi-irreversibility of fixed costs, learning effects, network externalities and locational inflexibilities (David, Citation1985). These subsequently facilitate ‘agglomeration economies’, which become a self-reinforcing mechanism.

Under the conditions of dyadic relationships, co-evolutionary studies have emphasised that institutions and economic activities change (Gong & Hassink, Citation2019). Institutional changes are mediated by the actions of actors/agents (Hu & Yang, Citation2019; Lang, Citation2012), a collective bargaining process among agents (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2008; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Sjöstedt, Citation2015), or an evolutionary process (Williamson, Citation2000). The first and second of these correspond to endogenous changes in the institutions facilitated by formal and informal institutional arrangements. Informal institutions can complement, accommodate, compete with or substitute a formal institution during the change process (Helmke & Levitsky, Citation2004). Changes in the external environment facilitate changes in the institutional environment. Such changes are also categorised as exogenous changes (Young, Citation2010). While exogenous shifts/‘major’ changes in the institutional environment puncture existing lock-ins (Strambach & Halkier, Citation2013), continuous/ongoing changes are categorised as ‘minor’ or ‘incremental’ (Grillitsch, Citation2015; Mahoney & Thelen, Citation2010; Van der Heijden, Citation2011). Mahoney and Thelen (Citation2010) emphasised that ‘major’ changes are ‘radical’ and ‘minor’ changes are ‘incremental’ (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Change can be bottom-up, wherein agents can reinterpret and subvert the rules, or top-down, wherein powerful agents create new institutional arrangements (Evenhuis, Citation2017). Agency theory deals with individual behaviour at the micro-level (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014). Owing to the above, institutions undergo changes that can be categorised as layering (new institutions emerge alongside existing ones), conversion (the disposition of old institutions for new purposes), drift (new institutions emerge but agents do not respond), and displacement (old institutions are replaced by new ones) (Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). The next section discusses the relationship between institutional changes, the interaction between agents, and spatial economic resilience.

4. SPATIAL ECONOMIC RESILIENCE

The ‘selection’ and ‘retention’ of economic activities in a continuously changing institutional environment/arrangements are contingent on the socio-economic conditions. The ‘selection’ process is facilitated by numerous factors. These include agglomeration economies at different spatial scales (Liu et al., Citation2020), increasing returns accruing to firms owing to economies of scale (localisation economies) (Malmberg & Maskell, Citation2002) and economies of scope (urbanisation economies) (Fu & Hong, Citation2011), ease of matching skills, and positive externalities (Graham, Citation2007) caused by spillover of knowledge (Alonso-Villar, Citation2002; Henderson, Citation2007) and technology (Koo, Citation2005). ‘Path dependency’, as discussed in the previous section, is the cause of the ‘adaptation’ of economic activities to the selection environment. Proponents of the resilience literature have argued that an economy scoring high on ‘adaptation’ is likely to be less resilient to an external economic shock or a radical change (Pike et al., Citation2010; Simmie & Martin, Citation2010). Instead, a variety of economic activities in a region enhances its ‘adaptability’ (Boschma, Citation2015; Hassink, Citation2010; Hu & Hassink, Citation2017; Martin & Sunley, Citation2010) and helps to de-lock existing routines (Wright et al., Citation2013) and dissipate the shock (Boschma, Citation2015; Sedita et al., Citation2017). Conversely, the presence of highly specialised activities can aggravate the shock (Hudson, Citation2007), leading to output, asset and employment losses (Hassink, Citation2010; Martin & Gardiner, Citation2019). Institutional changes lead to path creation, path renewal, path reorientation and path exhaustion of economic activities (Sotarauta & Suvinen, Citation2018). The next section discusses the proposed framework for establishing the relationships between the co-evolution of institutions (formal and informal) and economic activities, institutional change, path development, and spatial economic resilience.

5. FRAMEWORK OF CO-EVOLUTION, AGENCY ISSUES, INSTITUTIONAL CHANGES AND URBAN ECONOMIC RESILIENCE

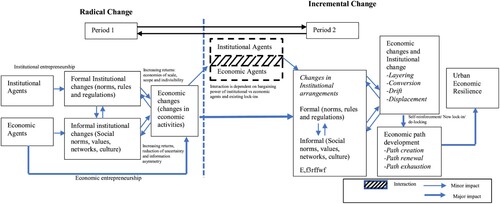

The framework discusses two ways in which the existing system changes. It also traces the time frame, where an institutional change separates one time period from the other.

First, in period 1, institutional entrepreneurs initiate radical/exogenous changes in the institutional environment. This alters the socio-economic environment and the ways in which economic and institutional agents interact. The commencement of radical changes in the institutional environment leads to changes in the ‘selection’ environment. Subsequently, economic activities co-evolve by responding to the ‘selection’ environment (the reciprocal relationship is represented by two arrows in ). Changes in the institutional environment then initiate changes in the ‘agency relationship’ (the mediator) where interaction between institutional and economic agents is contingent upon the bargaining power and existing lock-ins. If the policy changes positively impact the informal institutional arrangements, then the interactions expedite ‘self-reinforcement’ and ‘lock-ins’. As a result, formal institutional arrangements undergo institutional layering in period 2. Existing economic structures are strengthened (path persistence) and new paths are created. The same can be observed when economic agents are quick to respond to changes in the institutional environment. Such agents find opportunities and deliberately create new paths and new routines with the aid of informal institutional arrangements.

Figure 1. Inter-temporal framework for co-evolution of institutions and economic activities.

If the policy changes initiated by institutional entrepreneurs are incongruent with the existing informal arrangements due to the uprooting of the spatial lock-ins, then the agents resist changes. Since the informal institutional agents have very high bargaining power due to the existing ‘spatial lock-in’, they are unlikely to break it. Institutional ambiguities arise due to the higher bargaining power of agents belonging to competing informal institutions, the rigidity of formal institutions, and the resistance of economic agents to change. The formal institutional agents use these ambiguities to their advantage by demonstrating opportunistic behaviour. If the incentives for the formal institutional agents by not executing the changes in the rules/regulations are greater than the sanctions imposed, there is a discord between the rules in the plan document and its execution that leads to informality as ‘non-compliance’ and ‘non-enforcement’ on the ground. This discord between rules/regulations and execution is a source of uncertainty/information asymmetry. Hence, we observe institutional drift, an incremental change, in period 2. Institutional drift renders the economic environment highly vulnerable and results in path exhaustion, eventually leading to the breakdown of routines and the de-locking of economic activities.

The second type of radical/exogenous change concerns changes in the economic environment. In the literature on developed economies, the generalised Darwinism framework identified entrepreneurship as the basic requirement for the introduction of variety. In contrast, self-employment (a concept different from entrepreneurship) is adopted as a survival strategy in developing economies. If the economic/selection environment changes quickly, but the formal institutional arrangements are too rigid, then the economic agents play the role of change agents and adapt to the changing economic environment. These economic activities are embedded in the informal institutional arrangements due to the lack of a timely response from the formal arrangements. Informal institutional arrangements help firms to develop new routines, create knowledge, build new contractual relationships, and generate the required institutional inertia. With sustainable institutional inertia, self-reinforcement/lock-in of economic activities can begin. This leads to an increase in the bargaining power of the economic agents. As a result, interactions between the agents are initiated in period 1. Formal institutional arrangements such as rules and regulations undergo incremental/endogenous changes, that is, institutional displacement. New institutional arrangements are created to accommodate self-employment activities. Hence, there is a ‘path extension’ for economic activities.

However, if formal institutional arrangements are too slow to respond, we observe opportunistic behaviour by the formal institutional agents. Informal institutional arrangements compete with formal arrangements and the latter undergo institutional conversion, wherein the old institutions are redeployed for new purposes, leading to path exhaustion. As discussed above, institutional ambiguities and rigidity become the sources of uncertainty during market transactions. Path creation and path renewal lead to urban economic resilience, which in turn is a result of the co-evolution of economic activities and institutions mediated by agent interactions at the micro-level ().

The following section elaborates on the case study, research design, and co-evolution of different populations belonging to divergent economic activities (industrial and service sectors) and institutions under the proposed framework.

6. STUDY AREA AND RESEARCH DESIGN

Urban agglomeration in developing economies such as India is guided by plan documents and land-use plans. The presence of a federal government structure renders it very difficult to analyse land development policies holistically for the country. Instead, it is interesting to delve into the issues of co-evolution and economic resilience by taking the case study of a city. The case study method is the most popular means of undertaking co-evolutionary studies. It is recognised for its ability to facilitate understanding of the various phenomena and processes embedded within the socio-economic context (Marshall & Rossman, Citation2014). The definition of a cut-off time frame can pose a challenge when conducting co-evolutionary studies because endogenous incremental changes in the institutional arrangements are continuous and are not well documented.

In contrast, it is comparatively easier to trace radical changes in the institutional environment because they are documented. With knowledge of the local planning procedure and having worked with the Delhi Development Authority (DDA), I selected pockets of the service sector and industrial use in the city of Delhi as the basis for undertaking co-evolutionary studies. DDA was established in 1957 to carry out planned development. The first plan document for the city was prepared after independence to control haphazard growth. Redevelopment of the Old City/core area was one of the prime objectives. Residential colonies for the resettlement of refugees from Pakistan in low-income housing were proposed. Land-use plans were considered to provide a solution to the complex and interrelated social, economic and cultural problems of the city. The plan documents had legal sanctity; therefore, it was difficult to make amendments (Delhi Development Authority, Citation1962).

To identify the case study areas, reference was made to existing land-use plans and approved zonal development plans. The land-use plan of Delhi for 1958 illustrated the dominance of mixed land use (commercial and industrial use) in the core area/walled city and Karol Bagh. The prospective land-use plan for 1982 (the land-use plans are available on the website of DDA) earmarked zones for the relocation of industries from the core to the outskirts. One such relocation site was chosen as a case study. Meanwhile, case studies for the service sector were chosen based on the proposals in the master plan of 1962 for the development of district centres (DCs) and reconnaissance surveys of the development status of DCs (such as Bikhaji Cama, Preet Vihar, Nehru Place, Saket) in 2012. Nehru Place DC was found to be a hub of information technology (IT) software and hardware services housing both formal and informal economic activities. In contrast, Saket DC was developed as a hub of highly formalised economic activities by providing spaces to high-end commercial brands and office space for financial, consultancy and insurance services. Thus, to understand the dichotomy between informal and formal economic activities, the Nehru Place and Saket DCs were chosen as case studies.

Radical changes in the institutional environment were primarily traced from the planning documents, notably master plans, zonal development plans, industrial policy, policy for commercial streets, newspaper articles and gazette notifications released over a period of 50 years. To trace changes in the institutional arrangements, interviews were conducted with different agents and reconnaissance surveys were undertaken. The qualitative data obtained from the interviews provided insights into historical accounts. Institutional agents were identified based on their administrative positions in the key planning organisations. contains a profile of the interviewees (an organisational chart is available on the website of the DDA). A total of 20 in-depth interviews were conducted with the economic agents (shop owners, owners of industrial units), five with DDA officials and five with officials from the National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA), which is the institute responsible for the preparation of master plan of 2041, in the period 2019–20.

Table 1. Profile of the institutional agents.

The interviewees were recruited via snowball sampling because they were difficult to identify. Open-ended questions were used in the semi-structured interviews; these were mainly conducted in Hindi and then translated into English with the help of an expert. Reconnaissance surveys were carried out in 2012, 2015 and 2019 to trace the changes in the subdivision plans. These changes and the persistence of non-conforming use activities in the case study area showcase informality as ‘non-compliance’. The divergence of the actual use activities from the approved ones in the case study areas represents a spatial manifestation of informal institutional arrangements. These will be discussed in detail in the next section.

7. CO-EVOLUTION OF INSTITUTIONS AND ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES IN DELHI

7.1. Industrial use

The core city of Delhi, that is, the Walled City and Karol Bagh planning zones, was home to a non-conforming, hazardous and unorganised sector. It contained industrial units catering to furniture, garment and electrical machinery production, repair services, a slaughterhouse, timber depots and fire hazard trades (Delhi Development Authority, Citation1962). To provide a healthy living environment, the first master plan proposed relocating the obnoxious industries to the outskirts of Delhi (land-use plans are available on the website of the DDA). A total of 32 planned industrial estates for small-scale and non-nuisance flatted complexes were proposed for relocation in the planning zone of Narela. Of these 32 planned industrial estates, 21 were under the jurisdiction of the DDA and the remainder were developed and maintained by the Delhi State Industrial and Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd (DSIIDC) (Department of Industries, Citation2010). During the preparation of the first master plan, the institutional environment was changing as a socialist government came to power. The idea of the plan document was to provide a healthy living environment for all the residents of Delhi. Hence, a radical change in the institutional environment was observed in period 1. By 1990, however, only a few industries had shifted to the conforming use zones, that is, Narela, while non-conforming use activities continued in the core city. Interviews were conducted with the economic agents to understand the causes of this non-compliance. During the interviews, the economic agents cited marketplace uncertainty, the loss of existing supply chain networks, a lack of labour force availability, the absence of large-scale infrastructure and an increase in the cost of production as the prime causes for not shifting. The existing networks were a source of increasing returns for the firms. For example, neither buyers nor suppliers wanted to alter the existing buyer–supplier network because of the quasi-irreversibility of the location set-up costs. On the demand side, consumers faced high switching costs. The above-mentioned institutional arrangements were captured spatially by tracing the changes in use activities in the layout plans of the case study areas. Agency issues and transaction characteristics were captured through the interviews. Layout plans of the walled city were obtained from the Municipal Corporation of Delhi and use activities were roughly outlined on the plan during the reconnaissance surveys in 2012, 2015 and 2019 to trace the spatial ‘lock-in’. Mixed-use activities, especially manufacturing, commercial and residential, were found to be closely interwoven. The retail and wholesale markets for goods such as clothing items, leather products, metal products, domestic goods, timber and furniture were mapped and found to be in close proximity to the manufacturing units. The labour force comprised primarily self-employed/family and extended family members. Cash was the preferred mode of transactions and formal invoices were rarely generated. Transactions were recorded on a ‘kacha bill’, that is, a temporary bill that is neither recorded in a book of accounts nor revealed for tax purposes. Similarly, no quality assurance/certification was provided for the products. During the interviews, buyers revealed that they relied on the seller’s reputation. The sellers would reassure buyers: ‘In case of quality issues, bring back the product to me. You don’t need to show a bill for exchange. I have been in the business for generations. We work on trust.’ The radical change in the institutional environment accentuated the information asymmetry problem. As such, economic agents had strong apprehensions about shifting.

Subsequently, in 1996, the Supreme Court of India ordered the hazardous industries to be shut down. It also ordered the relocation of non-conforming industries to the conforming use zones. In light of this, the Delhi government prepared an industrial relocation scheme in 2006 and declared that 27,905 industrial units were eligible for allotment of land and flats in the planned industrial estates of Bawana, Jhilmil, Narela and Patparganj. By 2009, 17,801 industrial units had completed all the legal formalities and paid relocation fees and 16,667 had taken physical possession of the land or built-up area; however, only 5000 industrial units had begun construction work (Industrial Policy for Delhi, 2010–21). During the interviews, the economic agents revealed that the increase in congestion cost and the cost of informality as non-enforcement (sustenance of informal economic activities due to the high cost of monitoring and enforcement of formal regulations) incentivised a few of them to break the existing lock-ins. The onset of delocking can be attributed to endogenous changes in agglomeration diseconomies. However, the DDA’s failure to provide the necessary infrastructure promptly inhibited the self-reinforcement and spatial path dependence of the industrial sector in the new estates. Formal institutional agents from the DDA revealed that the involvement of multiple authorities and coordination issues caused delays, which initiated a dialogue between the economic agents and formal intuitional agents.

Dialogues between economic and institutional agents are difficult to observe in co-evolutionary studies but could nevertheless be ascertained here from the fact that many factory owners applied for a change of land use. Hence, a very interesting phenomenon was observed, wherein the economic agents collectively bargained to change the selection environment, which contrasted with the VSR (variety, selection and retention) framework in generalised Darwinism. There was a very strong ‘Self-reinforcement’ of economic activities facilitated by the informal institutional arrangements. However, such requests were not complied with; instead, non-conforming activities continued on the ground due to the nexus between the economic and formal institutional agents. The costs of informality as ‘non-compliance’ and ‘non-enforcement’ increased for the formal institutional agents. However, instead of working as ‘change agents’ or ‘institutional entrepreneurs’, they displayed opportunistic behaviour on the ground. This lack of ‘institutional entrepreneurship’ combined with the agents’ opportunistic behaviour led to a delinking of the provisions of the plan from the realities on the ground. This depicts an incremental change, that is, ‘institutional conversion’ in the next period. The collective bargaining power of the economic agents began to increase until finally, 20 non-conforming industrial clusters were identified for regularisation via a gazette notification in 2012, subject to the preparation and implementation of the redevelopment plans. Hence, institutions underwent institutional drift from the institutional change framework in the subsequent period.

Simultaneously, changes in the economic activities were taking place in the proposed industrial estates as unauthorised commercial and residential activities appeared (Industrial Policy for Delhi, 2010–21). The commercial activities were mainly small-scale self-employment units including grocery stores, stationery shops and retail units selling items such as clothes and shoes. The plan of 2001–21 proposed redevelopment of the existing planned industrial estates in a public–private partnership mode. However, no layouts for the redevelopment plans were prepared. During the interviews, the formal institutional agents disclosed that coordination problems and the unclear demarcation of functions between the DDA, municipal corporation and DSIIDC were behind the lack of timely land acquisition. Unauthorised commercial use continued from the 1990s until it was regularised by the DDA in 2018. Spatial manifestations of the institutional arrangements were traced on the layout plans during reconnaissance surveys wherein the extent of mixed-use activities and unauthorised construction was found to be rampant. The continuation of unauthorised activities and informality as non-enforcement reflects opportunistic behaviour and institutional ambiguity. Hence, institutional conversion was observed. However, an increase in the scale of commercial and residential activities in the industrial estates augmented the collective bargaining power of the economic agents. Additionally, it ultimately led to a change in land use from industrial to ‘commercial and residential’ in 2018. Hence, institutions underwent institutional displacement in the ensuing period. Economic agents adapted to the changing economic environment, especially after liberalisation in 1991, and catered to the increasing demand from the service sector. However, formal institutional agents revealed that big service-sector firms did not venture onto these industrial estates due to the unclear property rights resulting from unauthorised construction, the sale of property using ‘power of attorney’, and the lack of infrastructure and facilities. Hence, it can be concluded that while the economic agents adapted to the changing needs, the lack of clear property rights impeded the development of employment centres. A ‘reorganisation’ of economic activities toward the small-scale service sector was observed. Economic activities in the industrial sector slowly dwindled, as none of the policies took into account the existing ‘lock-in’ facilitated by the informal institutional arrangements. This resulted in path exhaustion and the eventual decay of the industrial sector.

7.2. Commercial use (service sector)

To enhance the diversity of economic activities, the plan of 1962 proposed centres for trade and commerce. To prevent ribbon developments, DCs were proposed as economic and employment centres with retail shopping facilities, professional and commercial offices, cinemas, small-scale industries, light manufacturing, and government offices. For instance, the DDA developed Nehu Place as a DC in 1972, which has since become the largest computer and IT accessories market in India. The DC provides office space for banks, consulting firms, and IT and outsourcing firms in addition to being a hub for computers and related accessories. After India opened up its economy in 1991, growth in the service sector accelerated. Radical changes in the institutional environment paved the way for the rapid development of service-based employment centres in Delhi. To trace the spatial implications of the changes in institutional arrangements for the service sector, approved layout and subdivision plans of the case study areas were acquired from the DDA and use activities were earmarked during reconnaissance surveys in 2012, 2015 and 2019. In Nehru Place, formal institutional arrangements facilitated agglomeration economies at the city and neighbourhood levels by providing connectivity to the city via arterial roads and the metro. During the surveys, it was observed that while the commercial retail shops were small, many of them acted as a single unit. For example, if a customer wanted to purchase a product from a particular brand and that product was unavailable in the outlet in question, then instead of disclosing its non-availability, the shopkeeper would approach the nearby shops and ensure the product was available to the customer. The economic agents worked in a close-knit network and these informal institutional arrangements spatially manifested in the form of non-compliance with the approved layout plan, characterised by unauthorised construction, change in use activities, and the further subdivision of plots. While such activities were rampant in the commercial units, they were limited in the office spaces allocated to consultancy firms, banks and financial advisory firms, among others. The primary reasons behind such actions as disclosed during the interviews were twofold. First, the retail units practiced backward integration to reduce inventory holding costs; and second, the units maintained buyer–customer relationships. This was also one of the survival strategies that firms adopted to adjust to the growing needs of the service sector. Further analysis of the transacted products was then carried out to delve into the causes of the observed ‘lock-in’. It has been widely documented by the US Trade Representative (2014) that the DC, as a hub for computer-related accessories, is a ‘notorious’ market where copyright-infringing content is sold openly (The Indian Express, Citation2014). During the interviews, the economic agents revealed that the demand for computer-related hardware and software increased post-liberalisation and after the establishment of service-sector firms in the vicinity. Low-cost pirated products were widely used by businesses and individuals to meet immediate demand. The DC thus became a supplier of pirated computer accessories across India. Interestingly, the sellers sold the goods to retail customers with a disclaimer of ‘no guarantee, no warranty’. Hence, it became important for buyers to develop a social network with the seller to reduce the uncertainty concerning ‘quality’. In this way, the ‘network externality’ of the products and the ‘social network’ between the buyer and seller provided the required institutional inertia for ‘lock-in’ and path dependence. In addition, such lock-ins could emerge due to a lack of formal institutional regulations for intellectual property rights (IPR). In view of this, it is evident that the formal institutional agents were aware of the malpractice; however, since the economic activities were not ‘non-conforming’ to land-use provisions, the matter was not within their purview. Scrutinising the legality of conforming economic activities is also beyond the scope of this study.

During the field surveys of 2019, it was observed that firms were competing on some products and colluding on others. This phenomenon was unique to the firms co-located in this area. It demonstrated that the shops were undergoing a process of scaling up and formalisation. The economic agents revealed that over a period of time, customers had become quality conscious and refrained from buying second-hand and pirated products. Hence, the spatial configuration of the retail shops evolved in response to changes in consumer demand.

In contrast, economic activities conducted in the newly developed Saket DC (which opened in 2007 but only became fully functional after 2012) were found to be very different from those in Nehru Place. Formalised commercial facilities such as shopping malls and office spaces were developed in Saket DC. However, although the DC was developed with world-class infrastructure and facilities, it failed to become a specialised one. Interestingly, a radical change in the institutional environment led to changes in the ‘selection’ environment, and the economic agents, facilitated by informal institutional arrangements, responded to these changes. The master plan of 2041 envisages Delhi as a knowledge and innovation centre for the promotion of research and development, conferences, exhibitions, and cultural and creative activities. The plan also proposes repurposing the existing industrial estates for the knowledge-based service sector. This echoes the institutional ‘layering’ of the institutional change framework in period 2. Further, changes in the formal institutions for the service sector do not undermine the existence of institutional arrangements but rather reinforce them, leading to path creation for economic activities.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The literature on spatial economic resilience has developed greatly from its unidirectional evolution under the generalised Darwinism framework to acknowledge the complex and reciprocal relationship of multiple populations under the complexity theory. Since economic activities are embedded in socio-economic and cultural contexts, co-evolutionary studies of institutions and economic activities shed light on the economic resilience of spaces. This study highlights the role of informal institutional arrangements in correcting market failure and positively impacting economic resilience, especially in the context of developing economies characterised by institutional voids. The micro-level agency issues proposed in the complexity theory have rarely been studied with reference to cities/regions in developing economies. Hu and Yang (Citation2019) proposed a framework for institutional change, path development and the economic resilience of cities by undertaking co-evolutionary studies for cities in China. This study incorporates the notion of time and proposes an inter-temporal framework for the co-evolution of institutions and economic activities, institutional change, and changes in economic activities embedded in the informal institutional arrangements mediated by interactions between institutional and economic agents. Co-evolutionary studies of institutions and divergent economic activities in the case study area of Delhi revealed that informal institutional arrangements such as social ties and networks facilitated agglomeration economies. The spatial manifestation of informal institutional arrangements can be traced in the form of non-compliant and mixed-use activities. A radical/exogenous change in the institutional environment, that is, a policy change to shift industries from the city core to the outskirts, led to resistance by economic agents. The rigidity of the plan document, opportunistic behaviour on the part of institutional agents, high sunk costs and the hindrance of agglomeration economies led to institutional ambiguity. It is very difficult to de-lock economic paths rooted in strong social ties and networks. Thus, instead of a policy to de-lock such paths, it is recommended to focus on spatial informality as non-compliance and non-enforcement, thereby generating plan provisions that do not diverge far from the ground realities and include tougher sanctions for institutional agents in case of non-enforcement. Non-compliance by the economic agents led to the regularisation of non-conforming uses after a period of 30 years. Hence, the existing formal institutional arrangements underwent institutional conversion. Service-sector activities and commercial uses emerged in the parcels proposed for industrial use. This was caused by the rise of self-employment as a survival strategy by firms and a reorientation of the economy toward the service sector. Unauthorised commercial activities were regularised. Therefore, institutions underwent institutional drift, which eventually led to path destruction for industrial use. Meanwhile, economic entrepreneurs in the service sector were found to respond quickly to changes in the institutional environment. Supporting formal and informal institutional arrangements and timely execution of the plan provisions helped the service sector to flourish. Institutional layering and path creation for economic activities was observed in the service sector. It is simpler to de-lock economic paths rooted in economic entrepreneurship and technological changes. In these cases, institutional layering is recommended through incremental changes in economic and institutional arrangements to facilitate urban agglomeration, along with the timely execution of plan provisions.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Interviews with the subjects were conducted telephonically and in person. The author has taken explicit consent from the study participants and recorded their consent in voice mode while conducting the interviews. The author declares that full confidentiality of the personal identities of the subjects will be maintained.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). Persistence of power, elites, and institutions. American Economic Review, 98(1), 267–293. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.1.267

- Aldrich, H. E., Hodgson, G. M., Hull, D. L., Knudsen, T., Mokyr, J., & Vanberg, V. J. (2008). In defence of generalized Darwinism. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 18(5), 577–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-008-0110-z

- Alonso-Villar, O. (2002). Urban agglomeration: Knowledge spillovers and product diversity. The Annals of Regional Science, 36(4), 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001680200090

- Anderson, B. (2010). Migration, immigration controls and the fashioning of precarious workers. Work, Employment and Society, 24(2), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017010362141

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2011). The relational economy: Geographies of knowing and learning. OUP Oxford.

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823

- Bergh, J. C. V. D., & Stagl, S. (2003). Coevolution of economic behaviour and institutions: Towards a theory of institutional change. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 13(3), 289–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-003-0158-8

- Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49(5), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Breslin, D. (2011). Reviewing a generalized Darwinist approach to studying socio-economic change. International Journal of Management Reviews, 13(2), 218–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2010.00293.x

- Brie, M., & Stölting, E.. (2012). International handbook on informal governance, 19–39.

- Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2014). Building resilient regions: Complex adaptive systems and the role of policy intervention. Raumforschung und Raumordnung| Spatial Research and Planning, 72(2), 93–102.

- David, P. A. (1985). Clio and the economics of QWERTY. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 332–337.

- Delhi Development Authority (DDA). (1962). Master plan of Delhi, 1962. The Central Government.

- Department of Industries. (2010). Indian policy for Delhi, government of national capital territory of Delhi. Delhi: Department of Industries.

- Edquist, C. (Ed.). (1997). Systems of innovation: Technologies, institutions, and organizations. Pinter.

- Essletzbichler, J., & Rigby, D. L. (2007). Exploring evolutionary economic geographies. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm022

- Evenhuis, E. (2017). Institutional change in cities and regions: A path dependency approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx014

- Evenhuis, E., & Dawley, S.. (2017). Evolutionary perspectives on economic resilience in regional development. Creating Resilient Economies, 19–39.

- Fu, S., & Hong, J. (2011). Testing urbanization economies in manufacturing industries: Urban diversity or urban size? Journal of Regional Science, 51(3), 585–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2010.00702.x

- Gerry, C. (1987). Developing economies and the informal sector in historical perspective. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 493(1), 100–119. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716287493001008

- Gertler, M. S. (2010). Rules of the game: The place of institutions in regional economic change. Regional Studies, 44(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903389979

- Gong, H., & Hassink, R. (2019). Co-evolution in contemporary economic geography: Towards a theoretical framework. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1344–1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1494824

- Grabher, G. (1993). The embedded firm (pp. 255–277). Routledge.

- Graham, D. J. (2007). Agglomeration, productivity and transport investment. Journal of Transport Economics and Policy (JTEP), 41(3), 317–343.

- Grillitsch, M. (2015). Institutional layers, connectedness and change: Implications for economic evolution in regions. European Planning Studies, 23(10), 2099–2124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.1003796

- Hassink, R. (2010). Regional resilience: A promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp033

- Hassink, R., Hu, X., Shin, D. H., Yamamura, S., & Gong, H. (2018). The restructuring of old industrial areas in east Asia. Area Development and Policy, 3(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2017.1413405

- Helmke, G., & Levitsky, S. (2004). Informal institutions and comparative politics: A research agenda. Perspectives on Politics, 2(04|4), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592704040472

- Henderson, J. V. (2007). Understanding knowledge spillovers. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 37(4), 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2006.11.010

- Henisz, W. J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics & Politics, 12(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0343.00066

- Henning, M., Stam, E., & Wenting, R. (2013). Path dependence research in regional economic development: Cacophony or knowledge accumulation? Regional Studies, 47(8), 1348–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.750422

- Hodgson, G. M. (2002). Darwinism in economics: From analogy to ontology. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 12(3), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-002-0118-8

- Hodgson, G. M., & Knudsen, T. (2006). Dismantling Lamarckism: Why descriptions of socio-economic evolution as Lamarckian are misleading. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 16(4), 343–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-006-0019-3

- Hu, X., & Hassink, R. (2017). Exploring adaptation and adaptability in uneven economic resilience: A tale of two Chinese mining regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 10(3), 527–541. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx012

- Hu, X., & Yang, C. (2019). Institutional change and divergent economic resilience: Path development of two resource-depleted cities in China. Urban Studies, 56(16), 3466–3485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018817223

- Hudson, R. (2007). Regions and regional uneven development forever? Some reflective comments upon theory and practice. Regional Studies, 41(9), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701291617

- Ivy, J., & Perényi, Á. (2020). Entrepreneurial networks as informal institutions in transitional economies. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 32(9–10), 706–736. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1743770

- Kingston, C., & Caballero, G. (2009). Comparing theories of institutional change. Journal of Institutional Economics, 5(2), 151–180. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137409001283

- Koo, J. (2005). Technology spillovers, agglomeration, and regional economic development. Journal of Planning Literature, 20(2), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412205279796

- Lang, T. (2012). How do cities and regions adapt to socio-economic crisis? Towards an institutionalist approach to urban and regional resilience. Raumforschung und Raumordnung| Spatial Research and Planning, 70(4), 285–291.

- Liu, C. H., Rosenthal, S. S., & Strange, W. C. (2020). Employment density and agglomeration economies in tall buildings. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 84, 103555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2020.103555

- MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Pike, A., Birch, K., & McMaster, R. (2009). Evolution in economic geography: Institutions, political economy, and adaptation. Economic Geography, 85(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01017.x

- Mahoney, J., & Thelen, K. (2010). A theory of gradual institutional change. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power, 1, 1–37.

- Malmberg, A., & Maskell, P. (2002). The elusive concept of localization economies: Towards a knowledge-based theory of spatial clustering. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 34(3), 429–449. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3457

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2014). Designing qualitative research. Sage publications.

- Martin, R., & Gardiner, B. (2019). The resilience of cities to economic shocks: A tale of four recessions (and the challenge of Brexit). Papers in Regional Science, 98(4), 1801–1832.

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2007). Complexity thinking and evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 573–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm019

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2008). Economic geography: Critical concepts in the social sciences. Routledge.

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2010). The place of path dependence in an evolutionary perspective on the economic landscape. The Handbook of Evolutionary Economic Geography, 62–92.

- Matutinović, I. (2007). Worldviews, institutions and sustainability: An introduction to a co-evolutionary perspective. The International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 14(1), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504500709469710

- Mavros, P., Austwick, M. Z., & Smith, A. H. (2016). Geo-EEG: Towards the use of EEG in the study of urban behaviour. Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy, 9(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12061-015-9181-z

- McGlade, J., & Garnsey, E. (2006). The nature of complexity. Complexity and Co-Evolution: Continuity and Change in Socio-Economic Systems, 1–21.

- North, D. C. (1990). A transaction cost theory of politics. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 2(4), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692890002004001

- Pike, A., Dawley, S., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq001

- Schamp, E. W. (2010). On the notion of co-evolution in economic geography. In Ron A. Boschma & Ron L. Martin (Eds.), The handbook of evolutionary economic geography (pp. 432–449). Edward Elgar.

- Sedita, S. R., De Noni, I., & Pilotti, L. (2017). Out of the crisis: An empirical investigation of place-specific determinants of economic resilience. European Planning Studies, 25(2), 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1261804

- Simmie, J., & Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp029

- Sjöstedt, M. (2015). Resilience revisited: Taking institutional theory seriously. Ecology and Society, 20(4), https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08034-200423

- Sotarauta, M., & Suvinen, N. (2018). Institutional agency and path creation. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems. Theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 85–104). Springer.

- Stam, E. (2007). Why butterflies don’t leave: Locational behavior of entrepreneurial firms. Economic Geography, 83(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2007.tb00332.x

- Strambach, S., & Halkier, H. (2013). Reconceptualizing change: Path dependency, path plasticity and knowledge combination. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 57(1–2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw.2013.0001

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. (Eds.). (2005). Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford University Press.

- The Indian Express (2014, February 13). Nehru Place, Gaffar Market notorious markets for piracy: US.

- Van der Heijden, J. (2011). Institutional layering: A review of the use of the concept. Politics, 31(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2010.01397.x

- Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595

- Wright, M. O. D., Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2013). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In Robert B. Brooks & Sam Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). Springer.

- Young, O. R. (2010). Institutional dynamics: Emergent patterns in international environmental governance. MIT Press.

- Zhai, W., & Yue, H. (2022). Economic resilience during COVID-19: An insight from permanent business closures. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54(2), 219–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211055181