ABSTRACT

The efforts of agroecology-oriented farmers and peasants’ organizations have been studied in depth in relation to their political expression, but less so with regard to the forms they adopt to strengthen the socio-economic viability of small- and medium-sized farms within sustainable food systems. Whilst farmers’ self-organization represents a core process in the development of Agroecology-based Local Agri-food Systems (ALAS), the development of collective, economic structures among agroecology-oriented farmers’ is still weak. In an attempt to understand why and how agroecology-oriented farmers are constructing their own position within ALAS, and the challenges they are facing in this sense, we conducted a qualitative study on the self-organizational processes and structures of five Agroecology-Oriented Farmers’ Groups in Spain. Based on 27 interviews and six online, participatory workshops, our results reveal different reasons for joining and setting up farmers’ groups as non-mixed collective spaces, with instrumental and social factors constituting the principal motivations. Politics and advocacy aroused controversy and were only observed in the biggest, most powerful and well-structured organizations. The main challenges identified refer to the precariousness and isolation of farmers, as well as of the different local groups. The weakness of the Agroecology-Oriented Farmers’ Groups highlights the need for further action-oriented research and accompaniment

Introduction

Agroecological research has undergone a major change in recent years, with the scale of analysis being extended to food systems, and with a sharper focus on social and economic aspects (Mason et al. Citation2021). The scaling-up of agroecological transitions at food system level involves the material and economic dimensions, which presupposes the reorganization of production flows, and includes the creation of “communities of growers and eaters (that) can form alternative food networks around the world where a new culture and economy of food system sustainability (can be developed)” (Gliessman Citation2016, 188). For Gonzalez de Molina (Citation2013, 55) agroecological transitions entail “the implementation and multiplication of collective experiments in sustainable production and responsible consumption through the creation and strengthening of production and consumption groups, associations of producers and consumers.” This new economy requires transformations in logistics and production models, as well as in organizational forms and farmers’ own identities within the food chain itself (Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. Citation2018; Mount Citation2012).

Recent papers on Agroecology-based Local Agri-food Systems (in advance: ALAS) indicate “re-localization requires the territorial reorganization of production, logistics and consumption” (López-García and González de Molina Citation2021, 8) with strong emphasis on the articulation of isolated agroecological experiences in production, distribution and consumption. However, to date the agroecology literature referring to the food-system scale has been developed on a theoretical level, but to a lesser degree in the empirical sense (Mason et al. Citation2021). Within the context of other approaches with more empirical development, such as Sustainable Food Systems and Alternative Food Networks, the literature has focused particularly upon individual, direct marketing experiences in formats such as CSAs and farmers markets. But, farmers and peasant communities are recognized by some to constitute the protagonists of the agroecological transitions (Val et al. Citation2019), and more especially regarding their collective structures and agency (Marsden, Hebinck, and Mathijs Citation2018; Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. Citation2018).

Research on the organizational dynamics of producers to supply local markets has addressed formats such as food hubs (as third parties) linked to AFNs (Perrett and Jackson Citation2015; Stroink and Nelson Citation2013) and traditional cooperatives associated with commodity markets (Gray Citation2014a, Citation2014b). However, there is a lack of empirical analyses of the dynamics of organization of agroecology-oriented farmers within AFNs, as well as of the assemblages that AFNs must form among themselves and with other human and non-human actors in order to generate hegemony within food systems (Marsden, Hebinck, and Mathijs Citation2018).

The present paper attempts to fill this research gap. It is part of the RURBACT-Ae project, which will be further explained in section 3, promoted by the Spanish Red de Municipios por la Agroecología (hereinafter RMAe-Network of Municipalities for Agroecology) and field research was conducted from September 2021 to July 2022. The project arose from debates held within this organization (an association of Spanish Local Governments), in which the scarce presence of the (agroecology-oriented) farming sector in the local food policy agenda was observed and recognized. The RMAe deems this absence as a weakness in the co-production and implementation of food policies in member municipalities, and has set itself the general objective of strengthening the role of the agroecology-oriented farming sector in urban food policies and in the RMAe itself. To this end, our aim involves identifying the dynamics of self-organization in this sector, its weaknesses and the existing needs in terms of public policies. The present paper addresses the following research objectives: (1) to describe Agroecology-Oriented Farmers’ Groups, some features of their members and the reasons to join them; (2) to identify the specific role and features of AOFGs that makes them suitable to promote agroecological transitions at food systems’ scale; and (3) to identify the challenges they are facing for the scaling-out of agroecological transitions.”

Theoretical framework

In the present section we will first explore how agroecologists understand the role of farmers in Agroecology-based Local Agri-food Systems-ALAS (González de Molina and Lopez-Garcia Citation2021), as well as any potential dissonances between theory and actual collective experiences. Secondly, we will analyze the literature on the collective strategies of agroecology-oriented farmers for supplying local markets – farmers’ traditional cooperatives, food hubs and Participatory Guarantee Systems- in order to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each of these from an agroecological perspective.

Farmers within agroecology-based local agri-food systems

The potential for (social and ecological) sustainability of agroecology cannot be fully developed without the implementation of transitions at food-system scale (Gliessman Citation2016). Agroecology involves a holistic approach which necessarily comprises a set of farming methods, a science and a social movement (Rivera-Ferre Citation2018; Wezel et al. Citation2009), integrating issues such as food sovereignty, food security and agency (HLPE Citation2019), and which has been presented as “the ecology of the entire food system” (Mason et al. Citation2021). Agroecologists strongly defend and advocate equity, bottom-up governance and multi-actor participatory processes at the core of their approach (Anderson et al. Citation2019; López-García and González de Molina Citation2021; Méndez et al. Citation2017), in order to address the existing power imbalance in food systems, within what has been called “Political Agroecology” (González de Molina et al. Citation2019). Some authors stress the central role of farmers as protagonists of the transitions, suggesting a scheme of concentric circles. Agroecology-oriented farmers are to be the core tractors of a plural subject to promote the transition, within a wider circle of conventional family farmers, and surrounded and supported by (often urban) food movements (Edelman et al. Citation2014; Holt Giménez and Shattuck Citation2011; López-García and González de Molina Citation2021).

However, the ways and the means for the social subjects to become empowered to promote such transitions is still under-researched (Avelino and Wittmayer Citation2016), as well as the way in which such collective subjects can address the power imbalances existing within food systems. For a major change toward sustainability in food systems, it has been highlighted a need to promote assemblages of farmers groups, food security and consumer networks, public policies and authorities, and non-human actors and infrastructures, in order to provide access for food movements and agroecological farmers to the decision-making process (González de Molina et al. Citation2019; Marsden, Hebinck, and Mathijs Citation2018). At the core of such a discussion lies the question referring to the role farmers play in agroecological transitions at food-system scale, as they generally appear to constitute a rather fragmented and contradictory social subject (Bernstein Citation2010). Not only do they often oppose the notions of agroecology or even sustainability (Mamonova, Franquesa, and Brooks Citation2020; Shattuck, Schiavoni, and VanGelder Citation2015), but important sectors of farmers also justify and advocate regressive and unsustainable agri-food policies (Ploeg Citation2020).

Focusing upon Europe’s food systems, we can differentiate two different kinds of collective actors to explore the political agency of the farming sector, before addressing the issue of transitions toward sustainability: The first group would be represented by traditional farmers’ unions and farmers’ cooperatives that are generally oriented toward global commodity markets and intensification practices (Ajates Citation2020; Gray Citation2014a). Special mention should be given to what has been legally homogenized in the European Union under the category of “Producers” Organizations,’ mainly in the fresh fruit and vegetable sectors. POs have been promoted by the European Union in an attempt to consolidate the relationship between producers and markets, and to modernize the sector, adapting it to the requirements of big retailers, and to sustainable production standards (García Azcárate, Trentini, and Dasque Citation2022). However, conventional producers’ organizations can act as intermediaries in the transition of conventional farmers, regarding their legitimacy and embeddedness in the rural communities, and their capacities to support the transition both in terms of knowledge and material aspects (Groot-Kormelinck et al. Citation2022).

The second group is represented by the food sovereignty movement. It has developed strong socio-political organizations and alliances with urban food movements (Holt Giménez and Shattuck Citation2011; Val et al. Citation2019).This second group fails to attract the majority of conventional farmers toward transitions to sustainability, producer-consumer and urban-rural alliances, and progressive positions regarding social equity and environmental sustainability (Mamonova, Franquesa, and Brooks Citation2020; Bielewicz et al. Citation2020Shattuck, Schiavoni, and VanGelder Citation2015). Such a myriad of small and medium-sized farmers need a way out of the long-lasting crisis in the farming sector (Guzmán et al. Citation2022). They are open to agroecological transitions or they are already involved in the transition process -including the “proto-agroecological farmers” presented by Ploeg et al (Citation2019), organic farmers, or the so-called “agroecological farmers” (Cristofari, Girard, and Magda Citation2018; Deaconu et al. Citation2021). However, most of them are not organized in socio-political terms around food sovereignty organizations, and neither do feel represented by traditional, conventional farmers’ unions.

Focusing on the aforementioned two categories, there is an abundant body of research on the forms of aggregation of both groups. By one side, producers’ organizations act as structures for both political representation and marketing for conventional farmers’ (Ajates Citation2020; García Azcárate, Trentini, and Dasque Citation2022). On the other side, socio-political structures built around food sovereignty and peasants’ rights are useful for advocating at the global level - (Duncan and Claeys Citation2018; Giraldo and Rosset Citation2017). But there remains a pressing need to further study the way in which organic and agroecology-oriented farmers are organizing themselves in order to address local logistics and marketing challenges, especially in the Global North (Groot-Kormelinck et al. Citation2022; López-García and González de Molina Citation2021),

Farmers, economic collective structures and agroecology

The agroecological literature on farmers’ collective structures and movements has focused mainly on socio-political, territorialized peasant movements and the political construction and performance thereof, at both the local and global scales (Giraldo and McCune Citation2019; Giraldo and Rosset Citation2017; Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. Citation2018; Claeys and Duncan Citation2018; Val et al. Citation2019). Other studies have focused upon knowledge exchange networks for innovation and dissemination of agroecological farming practices, such as Campesino a Campesino (Rosset et al. Citation2011; Val et al. Citation2019). Only recent research has focused on the potential of local, agroecology-oriented farmers’ groups for promoting on-farm agroecological transitions (Groot-Kormelinck et al. Citation2022), territorialized transitions through wide, multi-actor alliances (Deaconu et al. Citation2021), and even sustaining food provision during COVID-19 pandemics (Frank et al. Citation2022). In all these case studies the literature focuses on experiences in the Global South. However, when we look at densely populated territories or scenarios in the Global North, farmers are to play an increasingly smaller role in the literature on sustainable food systems. In Global North settings, farmers’ involvement in transitions is often concealed as a weak group within broader plural subjects (Edelman et al. Citation2014; Holt Giménez and Shattuck Citation2011; López-García and González de Molina Citation2021), or in opposition to urban food movements (Bilewicz Citation2020), or it is addressed in minority profiles such as new farmers (Fernandez et al. Citation2013; López-García and González de Molina Citation2021). Additionally, the literature on farmers’ collective structures for local food supply seldom considers the relationships between the economic and the political dimensions of food systems (some exceptions can be found in Gonzalez de Molina Citation2020; Guzmán et al. Citation2013; Méndez et al. Citation2017), which remain an absent topic for empirical research.

The lack of empirical research could be giving rise to a certain inaccuracy in the terms used, but it also reflects disputes regarding both the material and immaterial territories around the term “agroecology” (Giraldo and Rosset Citation2017). For example, the concept of agroecology is used as a general formula to refer to highly differentiated farming systems, within which categories such as “agroecological farmers” tend to be used. This concept encompasses very diverse meanings, such as production models involving high inputs (such as herbicides) that are prohibited in certified organic agriculture systems and ones oriented toward distant markets (Cristofari, Girard, and Magda Citation2018), but also models that go far beyond organic certification standards, addressing both social and ecological issues (Deaconu et al. Citation2021). In our approach, agroecology is not a label or an adjective for describing certain products or ways of producing; rather, it is an approach featured as “the ecology of the entire (agri-)food system” (Francis et al. Citation2003; Mason et al. 2020). We therefore prefer to speak of “agroecology-oriented farmers” (or farmers’ networks) to refer to production initiatives whose farming practices are guided by agroecology principles and which go beyond (or at least always comply with) organic certification standards. They are oriented toward food sovereignty and local food systems, which incorporate social and labor justice and rights into their production systems. Let’s try to stress how Agroecology-Oriented Farmers’ Groups (AOFGs, in advance) may look like.

Some of the literature on Alternative Food Networks and Localized Food Systems highlights the potential of ecosystems of local operators in the food chain to improve their economic performance through coordination and cooperation (Clark and Inwood Citation2018). In some cases, farmer-to-farmer cooperation (knowledge, access to technology and storage facilities, etc.) is seen as a tool for increasing autonomy and in turn reducing the risks arising in the Short Food Supply Chains, together with complementary strategies such as product diversification and investments for scaling production (Fleiss and Aggestam Citation2020). Conventional producer organizations can act as intermediary networks to enhance on-farm transitions to sustainability (Groot-Kormelinck et al. Citation2022) or at territorialized scales (Deaconu et al. Citation2021). Some authors see a shift from local to regional scales as necessary to transcend “direct to-consumer” sales, in order to meet increasing demand for local and sustainable foods (Cumming, Kelmenson, and Norwood Citation2019). This would not necessarily mean losing the values inherent to local food systems, but rather reconfiguring and adapting them to the different farmers’ profiles and farming contexts, and adopting a dynamic approach to address the power imbalances and exclusions that occur when the AFNs are created (Mount Citation2012). Given the importance of collective farmers’ structures in the transitions to sustainability (in ecological, social and economic terms), we will revisit some collective formulas for farmers organization within the framework of localized and sustainable food systems. In the next paragraphs, we will focus on Participatory Guarantee Systems, Food Hubs and Agricultural Cooperatives, as the most references categories in the recent literature.

One frequent collective model responding to local food demand which is referenced in the agroecological literature are Participatory Guarantee Systems-PGS. They constitute local systems intended to generate trust and to guarantee compliance by producers with certain (social and environmental) sustainable farming standards, based on participation of farmers, consumers and other stakeholders such as advisors or researchers (International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements Citation2008). These PGS are not marketing or delivery structures; they can serve as a basis for local distribution networks within the framework of agroecological principles, avoiding the barriers posed by third party organic certification for small farmers, adapting guarantees to local conditions and actors, and building non-commoditized relations among producers and consumers (Cuéllar-Padilla and Ganuza-Fernandez Citation2018). A link between PGS and long-lasting social processes and communities through bottom-up collaboration can empower farmers (Home et al. Citation2017). However, PGS require a great effort by farmers, as well as their specific skills, to develop complex compliance and control systems, and to manage any eventual associated conflicts. While they are becoming more abundant on a global scale, the actual existing experiences are not suitable for all conditions, and they are limited to territories with dense networks of (usually small) farmers who are strongly committed to agroecology (Cuéllar-Padilla and Ganuza-Fernandez Citation2018). Additionally, as they are not marketing or delivery structures; they require the development of specific structures for this aim. In some territories (mainly in the Global South) PGS are linked to networks of “agroecological farmers,” and through such networks, farmers cooperate in distribution tasks and even in politics and advocacy (Deaconu et al. Citation2021), whilst advocacy activities may not be among the objectives of some PGS (Cuéllar-Padilla and Ganuza-Fernandez Citation2018).

In this sense, a large amount of literature on Alternative Food Networks has focused on (regional) food hubs. They are presented as structures for increasing access by small- and medium-sized farms to markets by organizing the logistics for scaling localized and sustainable food systems (Barham et al. Citation2012), and/or by supporting small farms unable to invest as a result of the so-called “poverty trap” (Stroink and Nelson Citation2013). Food hubs can support transitions to more sustainable farming practices both in material and immaterial terms -especially for medium-sized farms too big to join AFNs, and too small to survive in global markets (Brislen Citation2018). Food hubs can constitute a private, public or hybrid actor, and they can limit their activities to logistics and last-mile distribution or deploy many other services for production. However, they are usually described as third party, and can be therefore considered as alien to the farming sector (Barham et al. Citation2012). Therefore their role is not to strengthen the social fabric of farmers, or the political role and agency necessary for farmers to protagonize agroecological transitions at food-system scale. In practice, food hubs are currently serving rather as a vehicle for adapting small local productions to the demands of large (extra-local) operators active in the local environment, such as big retailer chains marketing local foods as part of their marketing strategy (Perrett and Jackson Citation2015).

Lastly, Agricultural Cooperatives are social movements formalized in their origins by (usually small or disadvantaged) farmers, often utilized around the world in reaction to the socio-economic injustices existing in agri-food systems and to gain access to markets (Gray Citation2014a). Agricultural Cooperatives of conventional farmers under the category of Producers’ Organizations have been highlighted as effective instruments for leading transitions to sustainability in farming practices in the European Union (García Azcárate, Trentini, and Dasque Citation2022). They do possess greater resilience whilst generating numerous community services that market models are unable to provide to small and medium-sized farmers (Ajates Citation2020). But, Agricultural Cooperatives have often been criticized because of their high transaction costs related to internal decision-making processes, which are more democratic and therefore more complex (Gray Citation2014a). Ajates (Citation2020) believes that the framework of Agricultural Cooperatives evolved from constituting a tool for farmers within the class struggle to being an instrument of the institutionalized social economy for placing the produce of small farmers on the global commodity markets, through enterprise formulas that are flexible, vertical (and non-democratic) and concentrated, in an effort to compete on global markets with private enterprises. Emery, Forney, and Wynne-Jones (Citation2017) argue that cooperation must be understood as a process, beyond specific legal or organizational forms, to unfold its emancipatory potential. In general terms, the literature on ACs has been criticized to be reductionist, as it tends to provide either economic or sociological analyses (the latter in very few cases), ignoring the more wide-reaching and ongoing tensions, dilemmas and contradictions in the movement (Gray Citation2014b). Consideration of production and consumption processes as separate categories reproduces a traditional gap both in research theories and in the praxis of food movements; and all this has given rise to proposals for hybrid formulas such as Multi-Stakeholder Cooperatives or Open Cooperatives (Ajates Gonzalez Citation2017). However, unitary production and consumption structures do not necessarily lead to more socially and ecologically sustainable models, as they could also be masking processes of overexploitation of labor and ecosystems, as is the case in some formats of Community-Supported Agriculture (Galt Citation2013).

Research background and methodology

In 2020 Spain ranked fifth in the World with regard to area of organically certified land (10% of agricultural area, 2,437,891 ha and 44,493 farms), albeit with a much lower rate of organic food sales (2.4% of family food expenditure) (MAPA Citation2021). The RURBACT-Ae project was implemented by the Spanish Network of Municipalities for Agroecology (RMAe from 2021 to 2022. Five pilot projects was launched through partnerships with five RMAe member municipalities (Ainsa-Sobrarbe, Madrid, Palma de Mallorca, València and Valladolid) and five local groups of agroecology-oriented farmers associated with urban food policies in each of these five territories. The participating local entities were, respectively, the network of producers linked to the project “Mincha d’Aquí,” supported by the NGO CERAI-Aragón; “Unión de Huertas Agroecológicas de Madrid,” supported by the grassroots organization “Madrid Agroecológico;” “Associació de Productors i Productores d’Agricultura Ecològica de Mallorca” (APAEMA); “Coordinadora Campesina del Païs Valenciá” (CCPV-COAG), supported by the “Fundación Mundubat;” and the “Vallaecolid” association of organic producers, processors and traders from Valladolid. Four of the five territories refer to metropolitan areas of regional capitals (all of these with over 400,000 inhabitants), and to producer networks located in the surrounding provinces (in the cases of Madrid, Palma de Mallorca and València) or region (Valladolid). In the case of Ainsa-Sobrarbe (2,151 inhabitants in 2018) the reference municipality is a rural one, grouping all the population nuclei of a large mountainous territory in the central area of the Pyrenees mountain range. In two case, the producer groups involved did not possess a formalized structure (Mincha d’Aqui, Unión de Huertas Agroecológicas de Madrid), and therefore participated in the project supported by local social entities with which they collaborate on a regular basis.

The project included three main activities: a self-diagnosis performed by each group; a dialogue between producers’ groups and political authorities with competencies in food policies in the respective City Councils; and online meetings among farmers from the five AOFGs to co-produce a political position document, common to all five AOFGs, which states their need for support through agroecology-oriented food policies. Both the objectives and the method and rhythms of the research project were discussed and agreed upon at the start of the process between the researchers (as coordinators and facilitators of the process) and representatives of the technical staff of the five AOFGs. Those representatives and the researchers met in monthly online meetings throughout the process, namely the “Driving Group” of the project. The driving Group discussed the outputs of the self-diagnoses to develop a final common diagnosis, and coordinated the other actions (dialogs between farmers and politicians, and drafting process of the position document).

Twenty-seven semi-structured interviews were conducted with farmers from the five groups, as part of the five self-diagnoses. Each self-diagnosis included between 5 and 7 interviews and one workshop to discuss the results of the interviews, after data being processed by each groups’ technical staff. The survey was designed through purposive sampling (Campbell et al. Citation2020), in an attempt to capture diversity in terms of gender, age, main crops, market orientations and quality labels (see in section 4). The interviewees proposed by its organization were also selected regarding their involvement in the organization. The questionnaire included closed and open questions. The former were included in order to shape interviewees profiles. The latter were oriented to gather qualitative information in order “to understand how meaning is attached to process and practice” (McGuirk and O’Neill Citation2016, 5–6). The open questions focused on the aims for joining the collective structures, the obstacles for achieving these aims, and on the opinions on the possible organizational forms to be adopted. The interviews were performed by the technical staff of each group, along a common questionnaire designed by the authors of the present paper.

Table 1. Main (average) profile features of interviewees of the five associations. Own data.

The codes used to cite interviewees in this article show the characteristics of the profiles as follows: the first letters and the first number refer to the municipality of reference of each initiative (V-Valencia; M-Madrid; P-Palma de Mallorca; VL-Valladolid; A-Ainsa-Sobrarbe) and the number of interviewees. The letters F and M refer to gender (F-female; M-male). And the last letters refer to the main crop (V-Vegetables; RT-Rainfed Trees; WT-Watered trees; L-livestock; P-processed foods). Thus, the third interviewee from APAEMA (Palma de Mallorca), a male and an olive-oil producer (rainfed trees) will be indicated as follows: P3MRT.

With the quantitative data obtained from the interviews we conducted a descriptive analysis of means, differentiated between territories. We then performed a qualitative thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) with the transcripts of the open-ended interview responses. To this end, we first manually classified all the contents into different thematic categories, created deductively from the categories in the questionnaires, introducing some emerging categories based upon the respondents’ answers (inductive approach). Secondly, we reread all the comments to detect nuances in relation to the arguments and ideologies within each category. With both types of data, the initial draft of a general diagnosis was drawn up, combining and contrasting data in the five territories, which was discussed by the farmers in face-to-face meetings in each territory. Local comments were collected to later discuss the diagnosis draft in an online meeting of the Driving Group of the process, which brought together the research team and representatives of the technical staff from each group. Following these discussions, a final version of a joint self-diagnosis of groups of agroecology-oriented farmers was drafted, based on the information and analyses from the five territories. We show its main results in section 4.

Results: Collective structures for agroecology-oriented farmers

This section provides data to give answers to the research objectives one and two. The first sub-section will describe the characteristics of the farmers interviewed, as a reference to the profiles included in each AOFG. The second sub-section will describe the farmers’ groups. The third sub-section will show the main reasons farmers state for their membership. And finally, the fourth sub-section shows the principal difficulties encountered with regard to the functioning of each entity, and in relation to their participation in governance spaces on agri-food policies.

Profiles of selected farmers involved in AOFGs

presents some values for characterization of the profiles of the farmers interviewed. The most common features of the interviewees from the five AOFGs involves family farms run by middle-aged men growing organically certified fresh vegetables, living and working in rural or periurban areas, and highly involved in other complementary collective entities such as farmers’ unions, traditional Agricultural Cooperatives, PGS or associations for the protection of traditional landraces. Nonetheless, as has already been stated, the sample of interviewees intentionally incorporates a bias that is intended to capture the views and positions of minority profiles in the AOFGs. (e.g. extensive cropping or livestock farming, women, or conventional farmers).

reveals some internal differences within the sample, and along different categories of analysis. The interviewees from Mincha d’Aqui, mainly livestock farmers living in a rural area, show 100% agricultural family background, but less professionalized profiles: a small economic size (farming constitutes their second economic activity in some cases) and reduced organic certification rates. In Vallaecolid, although 100% certified organic, average economic size of the farms is even lower (below 1 AWU/farm) and interviewees show a low rate of agricultural family backgrounds. Most farmers live and farm mainly in Valladolid’s metropolitan area. The Vallaecolid interviewees therefore present a profile of newcomers to farming, coming from urban backgrounds, as in the Unión de Huertos Agroecológicos de Madrid (UHAM). In the latter group (UHAM) the rate of organic certification is very low, with a large amount of production falling under direct marketing schemes and PGS systems. While a significant number of farmers overall are involved in PGS (in the territories where these exist), with interviewees clearly engaged in food sovereignty movements in their territories, most of them indicate a complementary strategy combining PGS (24% of the overall sample) and organic certification (65% of the overall sample).

Features of AOFGs

The organizational forms of the different groups are diverse, ranging from informal networks of producers (AHUM in Madrid or Mincha d’Aqui, in the Aragonese Pyrenees) to agricultural unions integrated into state-level structures (CCPV in València, integrated at state level in the Coordinadora de Organizaciones de Agricultores y Ganaderos, itself a member of La Via Campesina), or formal associations of organic farmers (such as APAEMA, in Mallorca) (see , in section 5). Positions regarding organizational forms differ between territories. In Madrid, Ainsa and Valladolid they opt for more flexible formats, such as producer groups and PGSs., with little commitment to joint marketing and political action. Those three groups show a higher frequency of nonprofessional farmers, including a majority profile of both new entrants into farming without agricultural family backgrounds and part-time farmers. The bigger groups (Mallorca and València) show a bigger proportion of professional farmers who converted from conventional to organic farmers, with bigger farms, and that opt for more structured and formalized models of organization: “(We want to create an) agroecological cooperative. An association remains lame” (VL4FL).

Table 2. Features of agroecology-oriented associations compared with other collective structures in the farming sector. Own data.

AOFGs are all explicitly committed to the promotion of agroecology and food sovereignty, while the main aims declared by the interviewees are instrumental and not political (e.g. marketing and logistics coordination). They constitute multi-purpose entities combining marketing, logistics and communication aims with service provision and promotion of mutual support activities among members; and they develop advocacy activities. In order to cover all these tasks, they are developing their own technical staff to support farmers in technical issues, but taking care not to supplant farmers in the decision-making process. At the same time, the interviewees indicated their additional involvement in a wide variety of organizations, often mutually complementary: “Cooperativism and associationism are for different types of support” (P4MV). The different structures are in synch with the entities participating in the project, including cooperatives, SATs, associations for collective advice, or Participatory Guarantee Systems.

The limited size of the organizations is also seen as an important tool for conserving internal governance mechanisms, and for ensuring that all members can participate in, and follow up on, the actions implemented by the technical teams. In territories with more professionalized profiles such as Palma de Mallorca, there is a commitment to strong structures and greater commitment from members: ”We are fortunate to have a strong association, such as APAEMA. Perhaps I would like to develop even more local assembly spaces and not delegate so much to the technical team. To decentralize a bit this work that they do. […] if we don’t, (we’ll) end up building structures that are too hierarchical and which we producers don’t feel like they are our own, and that we see more as a service that we hire” (P2MRT);

Their memberships is linked to specific territories, and their activities mainly focus on marketing and distribution activities for the local markets. The extension of such territories are mainly provinces, excepting the case in Vallaecolid, located in a wide and depopulated territory, and thus composed by members located in three different provinces. With the aim to keep control and democracy within their groups, agroecology-oriented farmers have made also a bid for non-mixed structures (in the sense of not including consumers, nor other food chain operators). Those AOFGs with stronger presence of new entrant profiles speak negatively about past experiences of mixed production-consumption groupings: ”Organizing along with consumption did not work. […] Direct sales and consumer groups are too time-consuming” (M2MV). Non-mixed organizations are additionally seen as a way to simplify internal management of the groups, through ensuring convergent profiles and interests.

Motivations for joining AOFGs

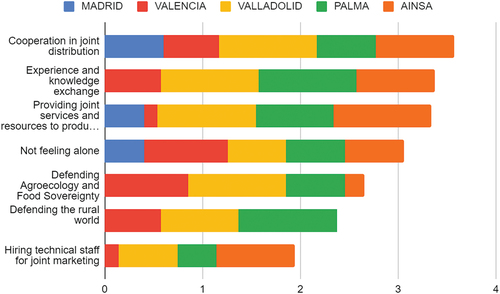

shows the main reasons expressed by interviewees for joining the AOFGs, based on a closed list of options. Instrumental motivation stands out in the five territories, especially with a view to joint distribution and marketing, the exchange of experiences and knowledge and the collective provision of production services. The motivation to hire technical marketing staff for occupies the lowest position in terms of value, and is only significantly valued by Vallaecolid (1 staff member) and Mincha d’Aqui (no staff members). In the other groups, this was not valued, having the ones of Mallorca and Valencia strong technical teams. A secondary plane refers to social aspects, which stresses a stronger focus on socio-emotional reasons than on political reasons to join in: “Feeling that you have the support of an association or other people you can count on is a relief” (P2MRT); “people who share your same problems and concerns” (M2MV). But also in relation to the visibility of their experiences and offer: “to unite with others and also to defend yourself against the big agri-food companies” (M3FV). In fact, the motivations related to advocacy display a very low value, as we will see in section 4.4, especially in Ainsa and Madrid, which bring together less professionalized profiles.

Challenges for AOFGs

The main difficulties described for the organization by agroecology-oriented farmers involve a lack of time and the small amount and dispersion of the initiatives included in each group: “(we) need to survive and look after the individual project. There is no time to look after the collective” (VL3MV). Great importance is given to the idea of collective entities being useful for producers and improving the conditions of the individual projects, as the only way to overcome competition between them: ”Articulation works when there are shared interests. […] Association does not (allways) work because it creates conflicts of interest” (M1MH). Numerous voices speak of a sector with a low degree of collective self-esteem (named “undervaluation of the profession” (V2MRT)), distrust and little involvement in the collective: “There is no trust or respect for collective structures: it seems that we are going to steal from each other and that we are competitors. I have joined with someone and what has happened is that I have been bypassed” (M3MV). The groups are weighed down by previous negative (collective) experiences, in contexts unfavorable to agroecology and small productive initiatives: “We have all had failed experiences that lead to disenchantment, due to price competition or ‘egos.’ It is ‘coming together to obtain and not to contribute’” (M2MV).

Many actors call for technical staff to be hired in order to dynamize and support the producers’ networks, although others are reluctant to do so. However, the possible hiring of personnel for the management of common issues (dynamization of the organization, administrative management, agronomic and financial consultancy, the search for subsidies, commercial management and communication, etc.) constitutes the least valued motivation, and some difficulties and tensions are noted in this respect: “there are clashes with the more theoretical or administrative party when it comes to making decisions in formal or political spaces, which are conditioned by very theoretical visions that disregard the knowledge of the producer who is in the field on a daily basis” (P3MAS); “in (our organization) there is a lack of commitment because it has been created from above and not based on the needs of the producer” (VL1MV).Footnote1 There tends to be a clash between proposals related to joint communication, with positions in which individual experiences prefer to maintain control over their sales and direct contact with consumers. Additionally, the less consolidated AHUM expresses the limitations of the PGS model: “(neither retailer shops nor Consumer Groups or other producers)”accept our PGS as a tool because other producers are not willing to be supervised or to show economic transparency” (M2MV).

Despite the importance attributed to political advocacy in the interviewees’ discourses, the comments generally reveal a distancing from the political decision-making spaces, and a feeling of powerlessness in this regard: “it weighs on us that we are very passive in making any demands; it is very difficult, we are very calm” (P1FV). Some reflections were collected in the discussion meetings to discuss the position document, which revealed an evolution in this respect: “Until now I have never been interested in European agricultural policies, but I am seeing that perhaps they are more important to my farm than I thought” (VL2FL).

The role of women in the organizations is mostly recognized as being very valuable, although not without contradictions: “Women suffer from invisibility and little appreciation by the collective. There are different dynamics, such as women devoting themselves more to organizational and technical tasks and men more to philosophizing about farming” (V3FRT). Women report situations of discrimination both outside and inside the organizations they belong to: “Despite the fact that women are more visible, and there are more women in charge of farms, equality is still not complete. There are obvious differences, for example with family conciliation (between care work and farming work)” (P1FV); “It has happened to me many times that I have not been recognized as a valid interlocutor. And when someone has approached us, they have said that they preferred to talk to my father. When I do the same job as him and I know the same things because he taught me” (P5FV). These situations are also recognized by some men: ”In practice, men have taken on a more visible role, with more importance and more strength. More public (visibility). […] It is essential to take on the ecofeminist discourse in agroecology […] to build from here new assembly-based networks” (P2MRT).

Some interviewees did not identify any problems with regard to gender inequality, although a majority of women see themselves as a minority, undervalued and unheard in their organizations, with the exception of those presenting clearly female majorities. Some men openly express conflict with women’s ways of doing things in their organization: “They (women) have a different vision, they are more administrators than executors of the activity, they get together a lot but do not execute” (VL1MV); while others recognize that female-dominated organizations function better: “I would highlight the fact that everything is very easy, more so than in other spaces where I have been before and where women were not in the majority” (P4MV).

Discussion: Agroecology-oriented farmers’ groups: A key tool in agroecological transitions at food system’s scale

The promotion of sustainable agri-food systems requires an increase in diversified food production and larger and more efficient logistics and distribution networks in local environments. It needs also access of agroecological experiences to the spaces where decisions on food systems’ regulation and governance are taken (Gonzalez de Molina Citation2020; González de Molina et al. Citation2019; Marsden, Hebinck, and Mathijs Citation2018). Agroecology-oriented farmers have been pointed out to be a weak actor to promote agroecological transitions at food system’s scale in Global North settings (López-García Citation2020, Citation2020). Additionally, the sustainable farming sector is actually not the decisive actor with regard to defining agri-food policies at different levels (Ajates Gonzalez Citation2017; Duncan and Claeys Citation2018; Gonzalez de Molina Citation2020; Marsden, Hebinck, and Mathijs Citation2018; Rivera-Ferre Citation2018). AOFGs are collective structures to strengthen agroecology-oriented farmers as a collective social subject in local food systems, both in economic and political terms. Thus, AOFGs are to play a central role in the development of agroecological transitions at food systems’ scale. In the present section, we will discuss how AOFGs are unfolding such a potential role, and the challenges they are facing in this task.

AOFGs: The role of farmers’ collective instruments to promote agroecological transitions

The most common profiles within the sample of interviewees fall within the category of what is known as the “agroecological farmer” (Deaconu et al. Citation2021) and even the “proto-agroecological farmer”(Ploeg et al Citation2019). They include certified organic farmers’ and other whose strategies are based on the reduction and re-localization of external inputs. They are much younger and show a proportion of women and neorrural than average farmers in the EU (EUROSTAT Citation2022; Sutherland Citation2023). The interviewees showed to be highly implicated in different collective structures, mixed or non-mixed with other food systems’ actors. These are considered to be complementary among each other.

The AOFGs they are creating constitute incipient structures intended to create the economic and social viability of the individual initiatives they comprise (Begiristain and López-García Citation2016). To this end, they have oriented the provision of local and organic food toward Agroecology based Local Agri-food Systems (González de Molina and Lopez-Garcia Citation2021), and in this sense they are important promoters of agroecological transitions at local levels. Additionally, they are involved (and are one of the main promoters) in the development of local, sustainable food policies in different Spanish territories (López-García and González de Molina Citation2020). The spatial proximity between its members is crucial for AOFGs, as their main aims are material -joint marketing and distribution activities in local markets. The close relationship between AOFGs and local administrations can also be seen as place-based, as a way of territorialized governance (Sanz-Cañada and Muchnik Citation2016).

AOFGs show a high internal diversity of organizational forms. Such a diversity reflects differences in the general objectives of each entity, in the profiles of the farmers that make them up, as well as in their adaptation to different geographical and socio-political contexts. However, we can establish some elements that differentiate AOFGs from other types of farmer’s groups previously analyzed (see ).

PGSs, as well as other mixed production-consumption structures (such as Multi-Stakeholder Cooperatives) enable relationships of trust and cooperation to be built between production and consumption beyond market relations. However, they are described by the interviewees as structures presenting significant maintenance costs in terms of time and dedication for members (Ajates Gonzalez Citation2017; Cuéllar-Padilla and Ganuza-Fernandez Citation2018). Therefore, they show an ambivalent potential for strengthening the collective social subject of agroecology-oriented farmers. Additionally, their potential for the development of local agri-food policies is limited, especially in situations in which the agricultural sector does not possess strong organizations.

The strategies intended to maintain the involvement and leadership of farmers within each entity, reflect a big difference with respect to the managerialist drift adopted by the Agricultural Cooperatives (Ajates Citation2020), or the third party management and purely commercial objectives of the experiences most cited for Food Hubs (Perrett and Jackson Citation2015). In fact, maintaining control of the collective structures in the production sector itself is presented as one of the main objectives differentiating AOFGs from other types of collective structures, such as Agricultural Cooperatives or the most common types of Food Hubs. The explicit aims to keep control under farmers’ decision defines the internal functioning of AOFGs, for example regarding the limited number of members in some cases, or the adoption of time-consuming models of internal governance, such as assemblies.

The non-mixed character (specific structures for farmers only) of the groups analyzed makes it easier to accommodate the diversity of profiles present among agroecology-oriented farmers, and at the same time to develop efficient structures to respond to the leap in scale in the demand for local and organic food. They also allow the interests and demands of a segment of the agricultural sector -agroecology-oriented farmers- which is not represented in traditional collective structures, such as Agricultural Cooperatives or most of the traditional Farmers Unions (Ajates Citation2020). Along AOFGs, agroecology-oriented farmers are able to be represented in an incipient way, despite their precariousness. This is despite the fact that some Producer Organizations are becoming active promoters of sustainable schemes, such as organic farming (García Azcárate, Trentini, and Dasque Citation2022).

Challenges and needs of AOFGs in relation to the scaling of agroecology

These entities comprise people overburdened with work in often-precarious productive initiatives, with little time for collective action and little knowledge of, or skills in, the agri-food policies that serve as a framework and condition their economic activity. Profiles that reject collective action for advocacy coexist with others that promote activities requiring public resources to support the sector, thus incurring in important contradictions. The interviewees’ lack of connection with some of the main current debates on agri-food policies, such as climate emergency (Pradhal et al. Citation2020) or food security (Moragues-Faus and Battersby Citation2021), has also been observed.

Although they all bring together agroecology-oriented farmers, the weakness and fragility that their members perceive in the collective structures they belong could also explain the diversity of models deployed. This reflects the search for organizational ways to survive in a context that does not support them, but rather rejects agroecological innovations, pushing toward conventionalization (Ajates Gonzalez Citation2017; Gonzalez de Molina Citation2020). While some urban food policy initiatives include specific actions aimed at strengthening the agroecology-oriented production sector (López-García Citation2020), for these actions to have the desired effect they require previously empowered actors (Avelino and Wittmayer Citation2016). The testimonies collected, as well as the debates developed thereby, indicate weak collective subjects, with few technical resources and little capacity for action. The widespread perception of not being supported by the administrations can be linked to the rejection of part of the agroecological movement toward collaboration or advocacy toward the different levels of the administration (see e.g. Cuéllar and Ganuza Citation2018). Nonetheless, farmers recognize their dependence on, and the importance of, public policies to meet the objectives of the entities, which all involves an important contradiction (Giraldo and McCune Citation2019; Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho et al. Citation2018).

The strongest entities and those with a stronger technical staff (APAEMA and CCPV), however, are involved in advocacy activities at the regional level, although they often delegate actions to other more specific organizations (such as the regional Regulatory Councils for Organic Production). In turn, they delegate advocacy at national level to the national structures they belong to, despite the fact that this detracts from the agroecological perspective in the food policy approaches of such national organizations, whose hegemonic positions are often regressive and opposed to agroecology (Ploeg Citation2020; Vázquez, López-García, and Pof Citation2022). In any case, there can be observed within those organizations a majoritarian opinion on the need for specific technical resources and staff to develop more active advocacy. The demand for recognition (both in monetary and symbolic terms) of the role of “experts” from the farming sector in research projects, advisory committees and agri-food governance spaces highlights a clear challenge for their advocacy activities.

Despite the general acceptance of the importance of the feminist approach in agroecology, in theoretical terms (Trevilla Espinal et al. Citation2021; Zuluaga Sánchez, Catacora-Vargas, and Siliprandi Citation2018), such organizations have been seen to host and reproduce situations of discrimination, which are expressed in individual and collective ways of doing (Siliprandi Citation2010), as well as in the greater burden of care work for women members (Khadse Citation2017). The testimonies collected highlight the limited impact to date of affirmative discrimination policies toward women, such as (Spanish) Law 35/2011 on the shared ownership of farms (Cabello Fernández Citation2018; de España Citation2011). Despite the recognition of this problem, no explicit actions for addressing these dynamics have been detected in the entities involved.

In any case, AOFGs represent new collective forms, which are necessary with regard to accompanying, and even leading the scaling of agroecological transitions toward ALAS. The relocalization of agri-food systems calls for a strong role for AOFGs, as well as the development of other collective structures capable of promoting sustainable and fair local food distribution and logistics systems (López-García and González de Molina Citation2021; Marsden, Hebinck, and Mathijs Citation2018). Structures that can respond to these challenges will have to be different from others operating on conventional markets, such as traditional Agricultural Cooperatives or Food Hubs, which are pointed out to reproduce the industrial and globalized agri-food system (Gray Citation2014b; Perrett and Jackson Citation2015).

Sustainability goals for agri-food systems promoted by supra-national institutions therefore require the promotion and development of AOFGs (European Commission Citation2020). However, the members of AOFGs doesn’t feel supported by current agricultural policies in the EU, and in fact the interviewees of the present research show a strong disaffection toward agricultural policies.Current agricultural policies are oriented toward large-sized farms, or to increase the size of the farms, along a one-size-fits-all approach (Sutherland Citation2023). Such policies are thus a clear expression of the so-called “systemic rejection” of agroecological transitions under the hegemony of the corporate food regime (Gonzalez de Molina Citation2020).

Conclusions: AOFGs as collective, multi-purpose structures to promote agroecology-based local agri-food systems

Agroecology-oriented farmers are creating their own collective economic structures, in order to give responses to the growing demand of local and sustainable food in Global North’s urban spaces. As all of them are playing a key role to provide sustainable food to local demand promoted along urban food policies, they play a role in Agroecology-based Local Agri-food Systems. The collective structures analyzed here are non-mixed (composed exclusively by farmers), limited in their number of members, and oriented to local markets. AOFGs are thus different from other collective structures of farmers oriented to the provision of sustainable food to local markets, such as PGSs, Food Hubs or traditional Agricultural Cooperatives. However, in many cases the memberships of the latter and of AOFGs are mutual, and in some cases they share similar objectives. The key factor expressed by agroecology-oriented farmers to develop AOFGs is to keep the control of their marketing structures. Such structures could combine different activities such as marketing, distribution and communication, and advocacy activities, all based on an agroecology and food sovereignty perspective. They are oriented to local markets and, in the cases analyzed, they are supported by urban food policies in different but very limited ways.

The precariousness and mutual isolation between individual farmers has been expressed as the main challenge for the commitment of farmers to AOFGs. Likewise, the precariousness and the limited size of AOFGs themselves is seen as a major challenge for addressing the needs of its members, as well as their limited capacity to cooperate between AOFGs, whether it is for marketing or advocacy activities. Additional issues have been identified as challenges for an adequate performance of AOFGs, such as a lack of knowledge on public policies and a diversity of positions toward political advocacy activities, members’ individualist cultures and bad experiences in previous collective entrepreneurships, and gender inequalities both in the individual farms and in AOFGs’ management structures. However, the analysis has revealed differences between AOFGs regarding internal structure or activities developed. Such differences are related to variables such as the ideological orientation and socio-economic profile of their members, the spatial proximity between its members, or the total number of members.

Regarding the important role AOFGs are to play in the development of ALAS, a prior understanding of how they develop and adapt to different territorial and political contexts, and differentiated farmers’ profiles, would be a relevant task in further agroecological research. Action-Oriented and Participatory-Action Research projects can constitute a useful tool in this sense, as they combine the generation of scientific knowledge, place-based knowledge and the strengthening of the social subjects involved in participatory processes. Additionally, further research is needed in order to better understand the needs of agroecology-oriented farmers’ and their collective structures – AOFGs – regarding public policies and public support.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to all people involved in RURBACT project, including farmers and AOFGs’ technical staff, for their commitment to the project and their cooperation with the present research, and in general for their commitment with the agroecological transitions at food systems’ scale.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Vallaecolid association was created with strong support from the Valladolid City Council, as a central element within the Local Food Strategy.

References

- Ajates, R. 2020. An integrated conceptual framework for the study of agricultural cooperatives: From repolitisation to cooperative sustainability. Journal of Rural Studies 78:467–79. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.06.019.

- Ajates Gonzalez, R. 2017. Going back to go forwards? From multi-stakeholder cooperatives to open cooperatives in food and farming. Journal of Rural Studies 53:278–90. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.02.018.

- Anderson, C. R., J. Bruil, M. J. Chappell, C. Kiss, and M. P. Pimbert. 2019. From transition to domains of transformation: getting to sustainable and just food systems through agroecology. Sustainability 11 (19):5272. doi:10.3390/su11195272.

- Avelino, F., and J. M. Wittmayer. 2016. Shifting power relations in sustainability transitions: A multi-actor perspective. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 18 (5):628–49. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1112259.

- Barham, J., D. Tropp, K. Enterline, J. Farbman, J. Fisk, and S. Kiraly. 2012. Regional food hub resource guide. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service.

- Begiristain, M., and D. López-García. 2016. Viabilidad económica y Viabilidad Social. Una propuesta agroecológica para la comercialización de la producción ecológica familiar. Etxano (Spain): ENEEK.

- Bernstein, H. 2010. The class dynamics of agrarian change. Halifax: Fernwood.

- Bilewicz, A. M. 2020. Beyond the modernisation paradigm: Elements of a food sovereignty discourse in farmer protest movements and alternative food networks in Poland. Sociologia Ruralis 60 (4):754–72. doi:10.1111/soru.12295.

- Braun, C., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brislen, L. 2018. Growing meeting in the middle: Scaling-up and scaling-over in alternative food networks. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 40 (2):105–13. doi:10.1111/cuag.12176.

- Cabello Fernández, M. D. 2018. La Titularidad Compartida De Las Explotaciones Agrarias Como Medida “bidireccional”». Estudios De Deusto. doi:10.18543/ed-66(1)-2018pp253-279.

- Campbell, S., M. Greenwood, S. Prior, T. Shearer, K. Walkem, S. Young, D. Bywaters, and K. Walker. 2020. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing 25 (8):652–61. doi:10.1177/1744987120927206.

- Clark, J. K., and S. M. Inwood. 2018. Beyond polarization: Using Q methodology to explore stakeholders’ views on pesticide use, and related risks for agricultural workers, in Washington State’s tree fruit industry. Agriculture and Human Values 35 (1):131–47. doi:10.1007/s10460-015-9618-7.

- Cristofari, H., N. Girard, and D. Magda. 2018. How agroecological farmers develop their own practices: A framework to describe their learning processes. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 42 (7):777–95. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1448032.

- Cuéllar-Padilla, M., and E. Ganuza-Fernandez. 2018. We don’t want to be officially certified! reasons and implications of the participatory guarantee systems. Sustainability 10 (4):1142. doi:10.3390/su10041142.

- Cumming, G., S. Kelmenson, and C. Norwood. 2019. Local motivations, regional implications: Scaling from local to regional food systems in Northeastern North Carolina. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2019.091.041.

- Deaconu, A., P. R. Berti, D. C. Cole, G. Mercille, and M. Batal. 2021. Agroecology and nutritional health: A comparison of agroecological farmers and their neighbors in the Ecuadorian highlands. Food Policy 101:102034. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102034.

- de España, G. 2011. Ley 35/2011, de 4 de octubre, sobre titularidad compartida de las explotaciones agrarias. Accessed October02, 2022. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2011/10/04/35

- Duncan, J., and P. Claeys. 2018. Politicizing food security governance through participation: Opportunities and opposition. Food Security. doi:10.1007/s12571-018-0852-x.

- Edelman, M., T. Weis, A. Baviskar, S. M. Borras Jr, E. Holt-Giménez, D. Kandiyoti, and W. Wolford. 2014. Introduction: Critical perspectives on food sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6):911–31. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.963568.

- Emery, S. B., J. Forney, and S. Wynne-Jones. 2017. The more-than-economic dimensions of cooperation in food production. Journal of Rural Studies 53:229–35. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.05.017.

- European Commission. 2020. Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European economic and social committee and the committee of the regions. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system (COM/2020/381 final). Accessed October 02, 2022. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52020DC0381

- EUROSTAT. 2022. Farmers and the agricultural labour force – statistics. Accessed May 10, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Farmers_and_the_agricultural_labour_force_-_statistics

- Fernandez, M., K. Goodall, M. Olson, and V. E. Méndez. 2013. Agroecology and alternative agri-food movements in the United States: Toward a sustainable agri-food system. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems. doi:10.1080/10440046.2012.735633.

- Fleiss, E., and V. Aggestam. 2020. Key aspects of scaling-up short food supply chains: A survey on Swedish food producers. Journal of the Austrian Society of Agricultural Economics. doi:10.24989/OEGA.JB.26.13.

- Francis, C., G. Lieblein, S. Gliessman, T. A. Breland, N. Creamer, R. Harwood, L. Salomonsson, J. Helenius, D. Rickerl, R. Salvador, et al. 2003. Agroecology: The ecology of food systems. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 22 (3):99–118. doi:10.1300/J064v22n03_10.

- Frank, M., B. Kaufmann, M. Ejarque, M. G. Lamaison, N. M. Virginia, and M. Martin Amoroso. 2022. Changing conditions for local food actors to operate towards agroecology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6:6. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2022.866004.

- Galt, R. E. 2013. The moral economy is a double-edged sword: Explaining farmers’ earnings and self-exploitation in community-supported agriculture. Economic Geography 89 (4):341–65. doi:10.1111/ecge.12015.

- García Azcárate, T., L. Trentini, and J. Dasque (2022). Sustainable Fruit and vegetables: a 40 years history. Accessed September20, 2022. https://tomasgarciaazcarate.chil.me/post/sustainable-fruit-and-vegetables-a-40-years-history-402406

- Giraldo, O. F., and N. McCune. 2019. Can the state take agroecology to scale? Public policy experiences in agroecological territorialization from Latin America. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 43 (7–8):785–809. doi:10.1080/21683565.2019.1585402.

- Giraldo, O. F., and P. M. Rosset. 2017. Agroecology as a territory in dispute: Between institutionality and social movements. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (3):545–64. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1353496.

- Gliessman, S. R. 2016. Transforming food systems with agroecology. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 40 (3):187–89. doi:10.1080/21683565.2015.1130765.

- Gonzalez de Molina, M. 2013. Agroecology and politics. How to get sustainability? About the necessity for a political agroecology. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems. doi:10.1080/10440046.2012.705810.

- Gonzalez de Molina, M. 2020. Strategies for scaling up agroecological experiences in the European Union. International Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resources 47 (3):187–203. doi:10.7764/ijanr.v47i3.2257.

- González de Molina, M., and D. Lopez-Garcia. 2021. Principles for designing agroecology-based local (territorial) agri-food systems: A critical revision. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 45 (7):1050–82. doi:10.1080/21683565.2021.1913690.

- González de Molina, M., P. F. Petersen, F. Garrido Peña, and F. R. Caporal. 2019. Political agroecology: advancing the transition to sustainable food systems. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Gray, T. 2014a. Agricultural Cooperatives. In Encyclopedia of food and agricultural ethics, P. B. Thompson and D. M. Kaplan. ed., 46–54. Dordrecht: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0929-4_203.

- Gray, T. 2014b. Historical tensions, institutionalization, and the need for multistakeholder cooperatives. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 23–28. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2014.043.013.

- Groot-Kormelinck, A., J. Bijman, J. Trienekens, and L. Klerkx. 2022. Producer organizations as transition intermediaries? Insights from organic and conventional vegetable systems in Uruguay. Agriculture and Human Values 39:1277–300. doi:10.1007/s10460-022-10316-3.

- Guzmán, G. I., D. López-García, L. Román, and A. M. Alonso. 2013. Participatory action research in agroecology: Building local organic food networks in Spain. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 120904081413002. doi:10.1080/10440046.2012.718997.

- Guzmán, G. I., D. Soto Fernández, E. Aguilera, J. Infante-Amate, and M. González de Molina. 2022. The close relationship between biophysical degradation, ecosystem services and family farms decline in Spanish agriculture (1992–2017). Ecosystem Services 56:101456. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2022.101456.

- High Level Pannel of Experts of the World Committee on Food Security-HLPE. 2019. Agroecology and other innovative systems. Rome: HLPE.

- Holt Giménez, E., and A. Shattuck. 2011. Food crises, food regimes and food movements: Rumblings of reform or tides of transformation? The Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (1):109–44. doi:10.1080/03066150.2010.538578.

- Home, R., H. Bouagnimbeck, R. Ugas, M. Arbenz, and M. Stolze. 2017. Participatory guarantee systems: Organic certification to empower farmers and strengthen communities. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 41 (5):526–45. doi:10.1080/21683565.2017.1279702.

- IFOAM-International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements. 2008. Participatory guarantee systems: Case studies from. Brazil, India, New Zealand, USA, France: IFOAM.

- Khadse, A. 2017. Women, agroecology and gender equality. New Delhi: Focus on the Global South.

- López-García, D. 2020. Who is the subject of agroecological transitions? Local Agroecological Dynamisation and the plural subject of food systems transformation. Journal of Sustainable and Organic Agricultural Systems 70 (2):36–42. doi:10.3220/LBF1606213050000.

- López-García, D., and M. González de Molina. 2020. Co-producing agro-food policies for urban environments: Toward agroecology-based local agri-food systems. In Urban agroecology. Interdisciplinary research and future directions, M. Egerer and H. Cohen. ed., 188–208. Boca Ratón (FL): CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9780429290992.

- López-García, D., and M. González de Molina. 2021. An operational approach to agroecology-based local agri-food systems. Sustainability 13 (15):8443. doi:10.3390/su13158443.

- Mamonova, N., J. Franquesa, and S. Brooks. 2020. ‘Actually existing’ right-wing populism in rural Europe: Insights from eastern Germany, Spain, the United Kingdom and Ukraine. The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (7):1497–525. doi:10.1080/03066150.2020.1830767.

- Marsden, T., P. Hebinck, and E. Mathijs. 2018. Re-building food systems: Embedding assemblages, infrastructures and reflexive governance for food systems transformations in Europe. Food Security 10 (6):1301–09. doi:10.1007/s12571-018-0870-8.

- Masikati, P., G. Sisito, F. Chipatela, H. Tembo, and L. A. Winowiecki. 2021. Agriculture extensification and associated socio-ecological trade-offs in smallholder farming systems of Zambia. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 19 (5–6):497–508. doi:10.1080/14735903.2021.1907108.

- Mason, R. E., A. White, G. Bucini, J. Anderzén, V. E. Méndez, and S. C. Merrill. 2021. The evolving landscape of agroecological research. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 45 (4):551–91. doi:10.1080/21683565.2020.1845275.

- McGuirk, P. M., and P. O’Neill. 2016. Using questionnaires in qualitative human geography. In Qualitative research methods in human geography, ed. I. Hay, 246–73. Canada: Don Mills.

- Méndez, V. E., M. Caswell, S. R. Gliessman, and R. Cohen. 2017. Integrating agroecology and participatory action research (PAR): Lessons from Central America. Sustainability. doi:10.3390/su9050705.

- Mier y Terán Giménez Cacho, M., O. F. Giraldo, M. Aldasoro, H. Morales, B. G. Ferguson, P. Rosset, A. Khadse, and C. Campos. 2018. Bringing agroecology to scale: Key drivers and emblematic cases. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 42 (6):637–65. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1443313.

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación-MAPA. 2021. El gasto en productos ecológicos en España se incrementa un 7 % con respecto al año anterior. https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/prensa/ultimas-noticias/el-gasto-en-productos-ecol%C3%B3gicos-en-espa%C3%B1a-se-incrementa-un-7—con-respecto-al-a%C3%B1o-anterior-/tcm:30-583763

- Moragues-Faus, A., and J. Battersby. 2021. Urban food policies for a sustainable and just future: Concepts and tools for a renewed agenda. Food Policy 103:102124. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2021.102124.

- Mount, P. 2012. Growing local food: Scale and local food systems governance. Agriculture and Human Values 29 (1):107–21. doi:10.1007/s10460-011-9331-0.

- Perrett, A., and C. Jackson. 2015. Local food, food democracy, and food hubs. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. doi:10.5304/jafscd.2015.061.003.

- Ploeg, J. D. V. D. 2020. Farmers’ upheaval, climate crisis and populism. The Journal of Peasant Studies. doi:10.1080/03066150.2020.1725490.

- Ploeg, J. D., D. Barjolle, J. Bruil, G. Brunori, L. M. Costa Madureira, J. Dessein, Z. Drąg, A. Fink-Kessler, P. Gasselin, M. Gonzalez de Molina, et al. 2019. The economic potential of agroecology: Empirical evidence from Europe. Journal of Rural Studies 71:46–61. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.09.003.

- Pradhan, P., S. Kriewald, L. Costa, D. Rybski, T. G. Benton, G. Fischer, and J. P. Kropp. 2020. Urban food systems: How regionalization can contribute to climate change mitigation. Environmental Science & Technology 54 (17):10551–60. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c02739.

- Rivera-Ferre, M. G. 2018. The resignification process of Agroecology: Competing narratives from governments, civil society and intergovernmental organizations. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 42 (6):666–85. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1437498.

- Rosset, P. M., B. Machín Sosa, A. M. Roque Jaime, and D. R. Ávila Lozano. 2011. The campesino-to-campesino agroecology movement of ANAP in Cuba: Social process methodology in the construction of sustainable peasant agriculture and food sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (1):161–91. doi:10.1080/03066150.2010.538584.

- Sanz-Cañada, J., and J. Muchnik. 2016. Geographies of origin and proximity: Approaches to local agro-food systems. Culture & History Digital Journal 5 (1):e002. doi:10.3989/chdj.2016.002.

- Shattuck, A., C. M. Schiavoni, and Z. VanGelder. 2015. Translating the politics of food sovereignty: Digging into contradictions, uncovering new dimensions. Globalizations 12 (4):421–33. doi:10.1080/14747731.2015.1041243.

- Siliprandi, E. 2010. Mujeres y agroecología. Nuevos sujetos políticos en la agricultura familiar. Investigaciones Feministas 1:125–37.

- Stroink, M. L., and C. H. Nelson. 2013. Complexity and food hubs: Five case studies from Northern Ontario, the international journal of justice and sustainability. Local Environment 18 (5):620–35. doi:10.1080/13549839.2013.798635.

- Sutherland, L. A. 2023. Who do we want our ‘new generation’ of farmers to be? The need for demographic reform in European agriculture. Agricultural and Food Economics 11 (3). doi: 10.1186/s40100-023-00244-z.

- Trevilla Espinal, D. L., M. L. Soto Pinto, H. Morales, and E. I. J. Estrada-Lugo. 2021. Feminist agroecology: Analyzing power relationships in food systems. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 45 (7):1029–49. doi:10.1080/21683565.2021.1888842.

- Val, V., P. M. Rosset, C. Zamora Lomelí, O. F. Giraldo, and D. Rocheleau. 2019. Agroecology and La via Campesina I. The symbolic and material construction of agroecology through the dispositive of “peasant-to-peasant” processes. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 43 (7–8):872–94. doi:10.1080/21683565.2019.1600099.

- Vázquez, G., D. López-García, and P. Pof 2022. El malestar del campo: reflexiones frente a la ofensiva ideológica de las derechas. Accessed October 06, 2022. https://ctxt.es/es/20220301/Firmas/39185/poblacion-rural-izquierda-ultraderecha-transicion-ecosocial.htm

- Wezel, A., S. Bellon, T. Doré, C. Francis, D. Vallod, and C. David. 2009. Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 29 (4):503–15. doi:10.1051/agro/2009004.

- Zuluaga Sánchez, G. P., G. Catacora-Vargas, and E. Siliprandi. (Coords.). 2018. Agroecología en femenino. Reflexiones a partir de nuestras experiencias. La Paz: SOCLA.