ABSTRACT

Objectives: Longer life expectancies imply increased prevalence of heart failure. Blittle is known about the maintenance of disease specific knowledge following patient education. Our aim was to investigate if self-care and heart failure knowledge persists at 9 month follow up among patients with heart failure after an outpatient programme in the Faroe Islands.

Methods: A prospective cohort study with patients recently diagnosed with heart failure were recruited and evaluated by questionnaire at baseline, after 3 and 9 months using The European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale and the Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale. Clinical and demographic information was collected.

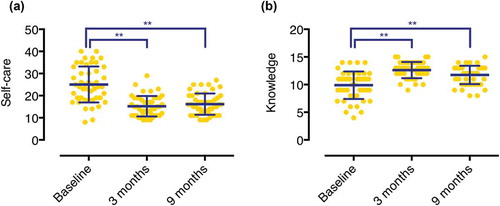

Results: Seven (15%) women and 40 (85%) men with heart failure and NYHA > 2 were included. There was an overall improvement in patients’ self-care from baseline 25 (8) to 3 months 15 (5) and to 9 months (16 (45); both p < 0.001). Mean knowledge score 10 (3) improved to 13 (2) at 3 months and 12 (2) at 9 months (both p < 0.001).

Conclusions: Disease specific patient education is applicable to heart failure patients, which can produce persistent improvements in self-care and knowledge after multidisciplinary outpatient programme.

Practice Implications: Multidisciplinary outpatient programmes are beneficial for patients with heart failure and alters disease specific knowledge and self-care.

Introduction

Due to an ageing population there is an increase in people living with heart failure (HF) which considerably affects the quality of life of the afflicted, estimated to constitute more than 5,5% of the population over 60 years, and their families as well [Citation1]. Heart failure is a complex and potentially life-threatening condition with debilitating symptoms for patients and an economic load to the healthcare system associated with around 1–3% of total healthcare distribution in Western Europe [Citation2,Citation3].

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) and secondary prevention programmes are known to reduce mortality, symptoms, hospital readmissions and costs, and to improve quality of life [Citation3,Citation4]. However, the information is sparse on the long – lasting effect of patient education with focus on disease specific knowledge and behaviour change techniques (BCT) [Citation5–Citation7]. Patient education is a core part of CR, where self-care promotion is an essential BCT objective [Citation8–Citation10]. Since 2008, the European Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of HF strongly emphasise self-care as a part of routine HF management and patient empowerment [Citation11]. Self-care is defined as a process that facilitates behaviours that maintains physiological stability by guiding the patient’s awareness of symptoms and direct the management of those symptoms [Citation12]. Self-care includes activities aimed at self-care maintenance (e.g. taking medication, exercising), monitoring (e.g. monitoring weight changes) and management (e.g. seeing the doctor with symptoms of fluid retention) [Citation9]. Studies show that less than 20% of patients with HF attend at CR programs and lack adequate self-care behaviour [Citation13–Citation15]. A comparison between HF patients in 15 countries worldwide showed that self-care among HF patients is sub-optimal and a culture- and country specific approach is needed with regards to improving self-care behaviour [Citation16].

Knowledge is necessary to effectively accomplish self-care [Citation17]. Previous studies have shown a significant improvement in self-care, quality of life and medication persistence among HF patients after receiving education compared with HF patients who did not receive such education [Citation4,Citation18–Citation20].

To our knowledge, evidence on long lasting changes in knowledge after patient education from a small-scale society is lacking. Our aim was to evaluate heart failure knowledge and self-care in a group of patients with heart failure receiving patient education in the acute and subacute phase (phase 1–2) of cardiac rehabilitation in an outpatient clinic in the Faroe Islands. This study can contribute to an evidence base for further development of home-based CR, aiming at providing equity in rural areas.

Methods

Design and setting

The study was a prospective cohort study. For STROBE checklist please see Supplementary file 1. The study conforms to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [Citation21]. Patients were informed oral and in writing and written informed consent was obtained. The local ethical committee was informed; however, approval was not required. The study was approved by the data protection agency (J. no. 17/00131–9).

The study took place at the largest cardiology outpatient clinic in the Faroe Islands – an archipelago consisting of 18 islands located in the North Atlantic Ocean with a population of approximately 50,000 inhabitants. There are only two cardiology outpatient clinics in the Faroe Islands; at the National Hospital located in the capital of Tórshavn serving roughly 90% of the population; and an outpatient clinic at a regional hospital on the island of Suðuroy [Citation22].

Recruitment and data collection

Patients diagnosed with HF from January 2015 to January 2017 were recruited. Heart failure was diagnosed during hospitalisation for symptomatic HF or after an ambulatory consultation with a cardiologist. The inclusion criteria were: Recent new diagnosis of HF (left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤45%), age ≥18 years and no previous systematic HF education. The exclusion criteria were psychological and/or cognitive dysfunction. In total 72 patients were diagnosed with HF in the Faroe Islands during the recruitment period; 13 were subsequently excluded due to psychological/cognitive dysfunction. Three eligible patients were lost before inclusion; one patient died during the index admission, one patient had terminal cancer at index admission, and one patient emigrated. Fifty-six participants were eligible for inclusion. As shown in , nine patients were lost to follow up; three did not show for follow up visits; three declined to participate; three had follow up at another hospital, resulting in 47 participants who completed the study.

Figure 1. Flow Chart

All patients were evaluated by a nurse at their first outpatient clinic visit (baseline), after three months at a meeting at the outpatient clinic, and after nine months by telephone. The questionnaires are designed to be self-administered, but in our study four patients received practical assistance in order to complete the forms. The response rate was 100% at baseline and nine months, at three months two patients (4%) failed to answer the Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale.

Patient education

The outpatient programme containing standardised multidisciplinary heart failure related patient education consisted of oral and written information grounded on the COM-B model (“capability”, opportunity’, “motivation” and “behaviour”), that recognises behaviour as part of an interacting system involving the aforementioned components [Citation23]. The patients received the disease specific education by a multidisciplinary team during the accumulated visits in the outpatient clinic, and involved social support, goal setting, monitoring, instructions on how to perform the behaviour and consisted of learning to define and observe HF symptoms such as weight gain, oedema and dyspnoea [Citation5,Citation7]. Furthermore, patients were instructed in medication regimens. Risk assessment and self-monitoring refer to the patients’ ability to regulate their behaviour (e.g. sodium and fluid restriction and exercise). Psychological support and guidance was provided to patients to handle negative feelings of anxiety or depression that often occur in relation to HF [Citation24].

Data collection instruments

Baseline clinical and demographic variables were collected from the patients via the electronic patient records (Cambio COSMIC, Sweden). The European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS-9) and the Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale were translated to Faroese and back translated after permission from the original authors. The translation to Faroese was done by one of the authors (KL) and the back translation was done by an independent native English-speaking person. The EHFScBS-9 is self-administered and consists of questions about self-care behaviour of patients with HF. The scale is a five-point Likert scale between 1 (completely agree) and 5 (completely disagree) with a minimum total score of nine and a maximum of 45 points. Lower score indicates better self-care behaviour. The EHFScBS-9 has been found to be a valid and reliable instrument to assess the self-care of HF patients [Citation25]. The Dutch HF Knowledge Scale is a self-administered multiple-choice questionnaire with 15 items including HF knowledge in general, knowledge on treatment and HF symptom recognition. Each question has three possible answers where only one is correct. The scale has a minimum total score of 0 and a maximum of 15-points score. Higher score indicates better knowledge. The scale has been found to be a reliable and valid instrument to assess the knowledge of HF patients [Citation26].

Statistics

We tested all variables for normal distribution using the Kolomogorov Smirnov test. Variables were tested for normal distribution and presented as mean (standard deviation, SD) throughout. When appropriate we used student’s paired t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test or Friedman test with Dunn’s post hoc multiple comparison to test for differences. Categorical variables are presented as numbers (percentage) and comparisons are made using chi-squared tests. We conducted Spearman’s rho correlation analysis and multivariable linear regression analysis with backward elimination to examine the association between self-care and age, gender, educational length and living status. Missing data in the knowledge scale was handled as common-point imputation. Based on the sample size we chose to include only these four variables in our model. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24), “R” (version 3.0.3; R Development Core Team 2014, http://www.R-project.org/) and the GraphPad Prism 6.0c (GraphPad software Inc., La Jolla, California, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The present study included seven (15%) women and 40 (85%) men (). Female mean age was 66 (5) years and male was 63 (10) years (p = 0.2, ). Ischaemic heart disease was the most common cause of HF (43% for women and 55% for men, p = 0.6, ). Both men and women had an increase in mean LVEF from baseline to follow up (p < 0.05). The majority of patients were in NYHA functional class II at baseline (57%). All patients were up-titrated to highest tolerable dose in anti-congestive medication during follow-up. Treatment was discontinued in two patients due to hypotension. In this study 24 (51%) of the patients had primary school as their highest educational level while four patients (9%) had a university education. During the 9 months follow up period, two (4%) male patients were readmitted to hospital due to worsening of HF symptoms ().

Table 1. Demographic and clinical factors

There was an overall improvement in patients’ self-care from baseline to 3 months and from baseline to 9 months (25.0 (8.1) and 16 (4.8), respectively, both p < 0.001, ). There was no change from 3 to 9 months ()). The improvement in total self-care score reflects differences in most of the EHFScBS-9 replies, except from question 8 “I take my medication as prescribed”, which was stable throughout the follow up period (p = 0.76, ).

Table 2. Individual EHFScBS-9 questionnaire scores

Figure 2. Scatter plots for self-care and knowledge

Mean knowledge score at baseline was 9.9 (2.5), which improved to 12.6 (1.5) at 3 months and 11.7 (1.7) at 9 months (both p < 0.001, )).

There was a correlation between self-care baseline and knowledge at baseline, with higher knowledge correlating with better self-care (p < 0.001). This correlation was no longer present at 3 and 9 months. Knowledge at baseline correlated with knowledge at 3 and 9 months follow up (p < 0.001). Patients’ cohabitation status correlated with better self-care at baseline (p < 0.05, ), and age correlated inversely with knowledge at baseline (p < 0.05) and 9 months (p < 0.001). In a multivariable linear regression analysis, we found that living alone was associated with self-care at baseline (p = 0.037, ), whereas gender (p = 0.31), age (p = 0.76) and educational level (p = 0.48) were not. After performing a backward elimination of variables, only living alone remained in the analysis and continued being associated with self-care (beta = 6.35, p = 0.021, ).

Table 3. Correlation analysis

Table 4. Multivariable analysis for predictors of self-care at baseline

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

In our study, we found that knowledge and self-care improved from baseline to 3 months after patient education and this improvement persisted after 9 months. Higher age was associated with lower knowledge – a similar association was described in the US between high age and lower knowledge related to HF among patients in rural areas (29). Cognitive abilities are required to maintain a certain level of knowledge and perform self-care. The elderly can have problems with hearing, vision and cognitive deficits, these factors can all influence the outcome of patient education and become a barrier to attending CR [Citation27]. The elderly represent a large part of the overall HF population, and many of them are widowed and living alone. Living alone was associated with worse self-care. A growing body of research illustrates that shared care (involving family, friends or caregivers) is necessary to obtain sufficient self-care [Citation28–Citation30]. We suggest monitored CR for older patients with heart failure, aiming at providing resources especially to vulnerable patients living alone.

The baseline mean level of self-care was worse in our study when compared with other studies, but during follow up our group of patients made a marked improvement in self-care which resulted in a similar level of self-care at the time of follow up [Citation31,Citation32]. Habits, cultural beliefs and values are important factors affecting self-care. A low educational level in 50% of the participants might explain why the baseline level of self-care was lower in our patients compared with other studies [Citation33]. When we analysed each of the nine questions in the EHFScBS-9 separately, we observed an improvement in self-care for all questions. The patients exhibited good compliance with regards to taking medication as prescribed (), which was also shown in previous studies [Citation32,Citation34]. However HF patients frequently overestimate medication-compliance adherence in self-reported studies [Citation35], so it may be questioned whether our results reflect a true high compliance or not.

For the specific question in the EHFScBS-9 addressing sodium intake, our group of patients had a high score compared to other studies [Citation31,Citation32,Citation36,Citation37]. This is probably a reflection of the high sodium intake associated with a traditional Faroese diet. However, the mean score changed in our patients from 3.0 to 2.0 after the intervention, which was a level comparable to other patient cohorts [Citation32]. At baseline, the patients in our study were comparably more hesitant to contact medical staff for necessary disease management, than in two Spanish studies [Citation31,Citation32]. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that the patients in our cohort had relatively few symptoms – 87% were in NYHA II at baseline () – and therefore had little experience in managing symptoms. Previous research has shown, that patients can have difficulties relating to a question when they lack experience in a relevant context [Citation12]. It is evident that a focus on BCT and patient education is of great importance in CR and can be effective in improving knowledge about HF as measured by the “Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale” [Citation26,Citation34]. Our findings for baseline scores on the “Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale” and improvement after 3 months were comparable with previous findings from Europe [Citation26]. We furthermore found that knowledge is persistent after 9 months.

It is important to underpin the differences between the setting of the present study compared to previous studies. This study is performed in a rural setting, which can contribute to crucial differences in perceptions, preferences and barriers to improve the CR uptake. Municipal CR programs in rural areas differ in containment and duration; even more, some municipalities do not have any CR programs. Recruitment issues and retention of health professionals is a problem in rural areas, consequently the quality of the discharge care is likely to vary and is likely to contribute to lower CR referral rates.

The overall findings of this study suggest a possible benefit of standardised multidisciplinary hospital-based patient education in the acute – subacute phase of heart failure rehabilitation (phase 1–2). Future studies of the potential effect of home-based CR in the intermediate and late phase of CR (phase 3–4) are of great significance. Tractability in CR is important because of the diversity of health status, geographic location and demographic challenges in rural and remote areas. Home based programs with telephone support, community services and CR apps are alternative CR models, however studies show inconsistent results and hence randomised clinical studies are warranted [Citation6,Citation38].

Due to the small population of 50,000 inhabitants in the Faroe Islands, our study sample was small and statistical power for detecting differences was low. However, if we apply the global incidence of HF (around 1,0 ‰ pr. year) to our setting approximately half of all new HF patients where included during the study period. The size of the study prevented us from investigating associations with aetiology and residence. The outpatient program was implemented as usual care before this study started, therefore a randomised controlled trial was considered unethical, although it would have given more firm answers to our research questions to investigate a possible effect of the standardised patient education. Furthermore, the size of this study does not allow us to draw firm conclusions, hence all results should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

An outpatient programme containing multidisciplinary heart failure related patient education was applicable to a population of heart failure patients and was found to promote patients’ self-care and knowledge assessed with the EHFScBS-9 and the Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale. Disease specific knowledge persisted over time and the results can indicate that a multidisciplinary patient education is beneficial to maintain sufficient self-care adherence, however this needs further research. Furthermore, higher age was associated with lower knowledge and patients living alone constituted a particular vulnerable group in the present study.

Relevance to clinical practice

Cardiovascular mortality and quality of life is known to improve after secondary prevention programmes. We found, that patient education with a BCT approach contributes to persisting improvements in self-care and disease specific knowledge in patients with heart failure. This study can contribute to endorse patient education containing BCT as a key component in secondary prevention in small scale societies with distant rural areas. Recruitment issues and retention of health professionals is a problem in rural areas, consequently the quality of the discharge care is likely to vary. We suggest monitored CR for older patients with heart failure, aiming at providing resources especially to vulnerable patients living alone.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, TR. The data are not publicly available due to data containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Statements

I confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (85.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Elin Winther Arge for collecting data, all the participants and the National hospital of the Faroe Islands especially the cardiological unit and the Faroese Heart Organisation. The study was supported by a grant from the Research Council Faroe Islands.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hoes AW, Wagenaar KP, Rutten FH, et al. Epidemiology of heart failure: the prevalence of heart failure and ventricular dysfunction in older adults over time. A systematic review. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:242–8.

- Buckingham S, Singh S, Davis R, et al. Optimising self-care support for people with heart failure and their caregivers: development of the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH-HF) intervention using intervention mapping. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2:1–37.

- Budi Siswanto B, Shimokawa H, Samal UC, et al. Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Hear Fail. 2014;1:4–25.

- Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. Heart failure clinics are still useful (More Than Ever?). Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:272–275.

- Heron N, Kee F, Donnelly M, et al. Behaviour change techniques in home-based cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:e747–757.

- Dalal HM, Taylor RS, Jolly K, et al. The effects and costs of home-based rehabilitation for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The REACH-HF multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;26:262–272.

- Herber OR, Atkins L, Störk S, et al. Enhancing self-care adherence in patients with heart failure: a study protocol for developing a theory-based behaviour change intervention using the COM-B behaviour model (ACHIEVE study). BMJ Open. 2018;8:e025907.

- Riegel B, Dickson VV. A situation-specific theory of heart failure self-care. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:190–196.

- Riegel B, Jaarsma T, Strömberg A. A middle-range theory of self-care of chronic illness. Adv Nurs Sci. 2012;35:194–204.

- Van Der Wal MHL, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Veeger NJGM, et al. Compliance with non-pharmacological recommendations and outcome in heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1486–1493.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129–2200.

- Riegel B, Dickson VV, Faulkner KM. The situation-specific theory of heart failure self-care: revised and updated. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2016;31:226–235.

- Riegel B, Driscoll A, Suwanno J, et al. Heart failure self-care in developed and developing countries. J Card Fail. 2009;15:508–516.

- Cocchieri A, Riegel B, D’Agostino F, et al. Describing self-care in Italian adults with heart failure and identifying determinants of poor self-care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015;14:126–136.

- Greaves CJ, Wingham J, Deighan C, et al. Optimising self-care support for people with heart failure and their caregivers: Development of the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH-HF) intervention using intervention mapping. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2:37.

- Jaarsma T, Strömberg A, Ben Gal T, et al. Comparison of self-care behaviors of heart failure patients in 15 countries worldwide. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:114–120.

- Van Der Wal MHL, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, et al. Compliance in heart failure patients: The importance of knowledge and beliefs. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:434–440.

- Nieuwenhuis MMW, Jaarsma T, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Long-term compliance with nonpharmacologic treatment of patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:392–397.

- Warren F, Davies R, Green C, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Rehabilitation Enablement in Chronic Heart Failure (REACH-HF) facilitated self-care rehabilitation intervention in heart failure patients and caregivers: rationale and protocol for a multicentre randomi. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009994.

- Lang CC, Smith K, Wingham J, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a facilitated home-based rehabilitation intervention in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and their caregivers: the REACH-HFpEF Pilot Study. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019649.

- World Medical Association. World Medical Associaton Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical rersearch involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194.

- Føroya H [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2019 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.hagstova.fo/fo.

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. 2014. www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

- Farkas J, Sedlar N, Mårtensson J, et al. Factors related to self-care behaviours in heart failure: A systematic review of European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale studies. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16:272–282.

- Jaarsma T, Årestedt KF, Mårtensson J, et al. The European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour scale revised into a nine-item scale (EHFScB-9): A reliable and valid international instrument. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:99–105.

- Van Der Wal MHL, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, et al. Development and testing of the Dutch heart failure knowledge scale. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;4:273–277.

- Uchmanowicz I, Jankowska-Polańska B, Mazur G, et al. Clinical interventions in aging dovepress cognitive deficits and self-care behaviors in elderly adults with heart failure. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1565–1572.

- Bidwell JT, Higgins MK, Reilly CM, et al. Shared heart failure knowledge and self-care outcomes in patient-caregiver dyads. Hear Lung. 2018;47:32–39.

- Lee CS, Vellone E, Lyons KS, et al. Patterns and predictors of patient and caregiver engagement in heart failure care: A multi-level dyadic study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:588–597.

- Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Quinn C, et al. Family influences on heart failure self-care and outcomes. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:258–265.

- González B, Lupón J, Domingo M, et al. Educational level and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure before and after nurse educational intervention. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13:459–465.

- Lupón J, González B, Mas D, et al. Patients’ self-care improvement with nurse education intervention in Spain assessed by the european heart failure self-care behaviour scale. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;7:16–20.

- Marmot M, Bell R. Social inequalities in health: A proper concern of epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:238–240.

- Boyne JJJ, Vrijhoef HJM, Spreeuwenberg M, et al. Effects of tailored telemonitoring on heart failure patients’ knowledge, self-care, self-efficacy and adherence: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13:243–252.

- Nieuwenhuis MMW, Jaarsma T, van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Self-reported versus “true” adherence in heart failure patients: a study using the medication event monitoring system. Neth Heart J. 2012;20:313–319.

- Lee CS, Lyons KS, Gelow JM, et al. Validity and reliability of the European heart failure self-care behavior scale among adults from the USA with symptomatic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12:214–218.

- Shuldham C, Theaker C, Jaarsma T, et al. Evaluation of the European heart failure self-care behaviour scale in a UK population. J Adv Nurs. 2007;60:87–95.

- Field PE, Franklin RC, Barker RN, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation services for people in rural and remote areas: An integrative literature review. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18:4738.