ABSTRACT

Inuit in Canada experience greater social and economic inequities than the general Canadian population. Food security exemplifies this inequity and is a distinct determinant of Inuit health. This scoping review focuses on food security-related policies implemented in Nunatsiavut, located in Northern Labrador. The primary objective was to identify the range of existing policies that pertain to food security in Nunatsiavut. The secondary objective was to complete a directed content analysis to map each policy against the applicable dimension of food security. This scoping review followed the Johanna Briggs methodology. The search strategy included the databases: Medline (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), CINAHL, and Scopus, and a hand search of the relevant journals, conference abstracts and grey literature. This search was undertaken from April 2019 – October 2019. A content analysis mapped each policy against the applicable dimension of food security.

Results: The results showed that twenty five policies were identified, spanning three levels of government, that explicitly or implicitly addressed at least one dimension of food security. Accessibility was the most frequent food security dimension identified. The Government of Canada developed 60% of policies and the Nunatsiavut Government implemented 48% of policies. Most policies focused on proximal factors for food security. Identifying distal policies for food security and understanding the impact of existing policies in Nunatsiavut remain as areas of further investigation.

Ethics and Dissemination:This project was reviewed by the Nunatsiavut Government Research Advisory Committee.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Inuit are an Indigenous people living in the circumpolar region [Citation1]. This region spans four countries: the USA (Alaska), Greenland, Russia (Chukotka), and Canada [Citation2]. Within Canada, Inuit primarily live in the four land claim areas: Nunavut, Inuvialuit in the Northwest Territories, Nunavik in Northern Quebec, and Nunatsiavut in Northern Labrador. These areas comprise Inuit Nunangat, referred to as the Inuit homeland [Citation1]. In 2005, Nunatsiavut became the first Inuit self-government in Canada through the implementation of the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement. Nunatsiavut is constitutionally protected under the aboriginal and treaty rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada guaranteed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 [Citation3]. It is located in Northern Labrador, in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada.

Inuit in Canada experience “greater social and economic inequities than the general Canadian population that impact their health and wellbeing” [Citation4]. Inequities are defined as differences in health status between groups of people that are due to unfair or unjust conditions. Food security exemplifies this definition and is identified as a distinct determinant of Inuit health [Citation5]. Labrador Inuit within Nunatsiavut are less food secure than the general population in Canada. A 2014 survey completed in Nunatsiavut demonstrated that of the households surveyed, only 40.7% of respondents were food secure. In 2014, the same measurement for the general Canadian population was 88.0%. In 2012, 86.6% of the population in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador were food secure [Citation6,Citation7].

Policy can have an important role in health equity. It can define a plan of action, set priorities, and guide resource allocation [Citation8–10]. In the general Canadian population, the intersection of policy and food insecurity has been an active area of research [Citation11]. Effective policy interventions have alleviated the burden of food insecurity within certain populations in Canada. One example is among social assistance recipients in Newfoundland. Policy changes attributed to reducing food insecurity in this population were addressing insufficient incomes, moving income support clients into work, and addressing the financial vulnerability of income support clients [Citation12]. Another example is within low-income adults over the age of 65 in Canada. Introducing age eligible publicly financed pensions at age 65 for unattached low-income adults is attributed to reducing the prevalence of food insecurity by half in comparison to low-income Canadians under the age of 65 [Citation13].

Historically, food security has been considered a health issue. However, currently policies for food security are also outside of the health domain [Citation14]. Instead, they are related to factors such as socioeconomic change, geography, environment, and climate change [Citation15]. A variety of international and national documents have policy recommendations that demonstrate a diverse policy space for food security. They include the Social Determinants of Inuit Health in Canada [Citation5], the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food [Citation16], Recommendations on Northern Sustainable Food Systems [Citation17], and Recommendations on Country/Traditional Foods from the Northern Policy Hackathon [Citation18] to name a few.

For Inuit in Canada, policies pertaining to food security differ by region due to provincial/territorial and federal jurisdictions. Nunatsiavut was chosen for this scoping review primarily due to the low prevalence of food secure households in the region [Citation6] and the identification of food security as a priority in the Nunatsiavut Government Department of Health and Social Development Health Plan [Citation19].

The complete range of policies that pertain to the multidimensional concept of food security and Nunatsiavut has not been explored in recent literature. The range of policies remains unclear and has led to the questions: What are the policies that pertain to food security in Nunatsiavut? And, how do these policies relate to the dimensions of food security?

To answer these questions, this scoping review aimed to systematically identify any policy implemented in Nunatsiavut that pertains to food security. A content analysis was then completed to map each policy against the four dimensions of food security (availability, access, utilisation and stability [Citation20]; to assess for gaps and/or policy overlap (i.e. one dimension that has multiple policies). The scoping review was undertaken with the expectation that results could inform actions of stakeholders to advance policy efforts to improve food security in Nunatsiavut.

Objective

To complete a scoping review of the literature on the range of policies that pertain to food security in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Using the Population, Concept and Context (PCC) elements, the specific objectives of this review are as follows:

(1) Identify the range of existing policies that pertain to food security in Nunatsiavut;

(2) Complete a directed content analysis to code each policy against the applicable dimension of food security (availability, access, utilisation and stability).

Materials and methods

This review was conducted following the Joanna Briggs Methodology (JBI) for scoping reviews [Citation21] from April 2019 – October 2019. The findings of the review are reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension statement for reporting of scoping reviews PRISMA-ScR [Citation22].

Prior to undertaking this study, a preliminary search for existing or similar scoping reviews was completed. The databases searched were: Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI) database, and Epistemonikos. No similar or existing scoping studies or systematic reviews were found. This scoping review is new and does not build upon existing reviews. The protocol for this study was published in November 2019 [Citation23].

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this scoping review followed the relevant population, concept and context (PCC). The population included Labrador Inuit in Nunatsiavut, the concepts were food security and policy, and the context was current regional, provincial and federal policy. Each criterion is described below in more detail.

Population

The studies included published and non-published research studies and grey literature focused on Inuit in Canada, specifically Labrador Inuit in Nunatsiavut. As this is a relatively small population, the studies and documents are either inclusive of or focused specifically on Labrador Inuit in Nunatsiavut. It excluded articles that focused on other Indigenous groups and articles outside of Canada.

Concept

Two concepts were explored in this scoping review; the first was policy and the second was food security. Policy for the purposes of this scoping review is a “general term used to describe a formal plan of action adopted by an actor to achieve a particular goal” [Citation24]. It also included public policy which is the “expressed intent of government to allocate resources and capacities to resolve an expressly identified issue within a certain time frame” [Citation25]. Accordingly, this review included any legislation, regulations or programme policy that pertained to food security in Nunatsiavut.

The second concept, food security, is defined as “when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” [Citation20]. Food security has four dimensions. They are availability, meaning the quantity of safe and nutritious foods that are consistently available to individuals and meets their tastes and cultural traditions; access, which indicates individuals and households have the adequate economic and physical access to food; and utilisation, which refers to the proper biological use of food to provide sufficient energy requirements, essential nutrients, potable water and adequate sanitation. This includes the knowledge and skills to prepare and preserve food. Stability is the fourth dimension of food security, which refers to the ability to be food secure in the present and the future, mainly through a reliable supply of food products. The first three dimensions of food security are based on a “static concept of food security”. The fourth dimension is reflective of the “dynamic concept of food security” and considers the current and future state of food security. All four dimensions must be met to achieve food security [Citation20,Citation26].

Context

This scoping review focused on any policy that pertained to food security. As Nunatsiavut can be impacted by federal and provincial policies, no restriction was placed on where the policy was developed. However, the policy must be inclusive of or specifically focused on Nunatsiavut and included any policy that has a cultural component such as providing country foods.

Information sources and search strategy

This scoping review included publications of all types (for example research studies of any design, editorials, commentaries). Both published research and grey literature were searched. The grey literature search consisted of government websites and documents, newspapers, national Indigenous organisation websites and publications, and legal documents. Documents in this scoping review only included those in English due to constraints in translation resources. The time limit was documents published from 1985 until 2019.

A search strategy for databases consisted of keywords and MeSH terms related to Inuit, food security and policy (See Appendix A). The search strategy was conducted on the following four databases: Medline (via ovid), EMBASE (via ovid), CINHAL, and Scopus. A health information specialist provided assistance with the search strategy. A hand search of the circumpolar health bibliographic database and the journals Food and Food Ways, Food Policy Journal, and Arctic Journal was completed. The grey literature search terms consisted of food security and Inuit. The following government databases were searched: Canada Research Index, Government of Canada Canadian Public Documents, and the Royal Commission. Departmental websites were searched for the Government of Canada, the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, and the Nunatsiavut Government. Additional searches included websites for Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Inuit Circumpolar Council, Food First Newfoundland and Labrador, the Labradorian Newspaper articles from 2011–2019 and the Nunatsiavut Hansard Records from 2006–2018. The analysts considered the grey literature search completed when no new policies were identified, and the same data occurred repeatedly.

Patient and public involvement

This scoping review had a Nunatsiavut Government Advisory group that consisted of two representatives from the Department of Health and Social Development. The group’s role was to member check the list of policies prior to conducting the analysis to assist in filling potential gaps according to their knowledge of the region.

Study records

Data management

For the research studies, database search results were imported to Covidence Systematic Review Software (Covidence, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). After removal of duplicate articles, citation titles and abstracts were screened. For the non-published studies and grey literature, an Excel file was created with the name and reference for the document.

Selection process

Two independent analysts screened research articles in a two-level process. The level one screening was for the title and abstract of potential studies. Any studies with a yes or maybe proceeded to level two. The full document was then reviewed by the two analysts. If there was disagreement during level one or two, a third reviewer was available to provide a final decision.

The process differed for the non-published documents and grey literature. One reviewer developed a list of documents and added a yes or no and rationale for inclusion into an Excel file. A second reviewer reviewed the list and concurred or disagreed. Again, a third reviewer was available to provide a deciding opinion. The agreed upon documents were fully reviewed by two analysts. The list of identified policies was validated with the Nunatsiavut Government Advisory Group for this project. Two additional policies were added to the initial list as a result of member checking with the Nunatsiavut Government Advisory Group. The results are reported as per the PRISMA flow diagram [Citation27].

Data extraction process and analysis of results

The method by Hsieh and Shannon [Citation28] was used to complete a directed content analysis. This entailed a document review by two independent reviewers to extract the relevant data for each policy using an a priori-designed data extraction form. The form collected information on the following parameters: a description of the policy, the organisation/institution that developed the policy, the definition of food security used or implied, and any stated intended targets or outcomes. The extracted information was compiled in a tabular form. Additional data on the dates for policies, target audience for policy, department that implemented the policy, and place of implementation was added as a result of the document review. Two independent analysts reviewed the extracted data.

The extracted data informed the next step of the analysis, mapping the policies according to the four dimensions of food security. One analyst completed an initial mapping and the second analyst reviewed the results. Both reviewers were in agreement on the results.

Ethics and dissemination

This review did not require primary data collection and accordingly, ethics approval was not required. However, prior to starting the scoping review, the project was reviewed by the Nunatsiavut Government Research Advisory Committee. This group is separate from the advisory group and has a distinct function that involves reviewing research applications for research conducted in Nunatsiavut, to ensure that all research is completed with full knowledge of the Nunatsiavut Government and Labrador Inuit.

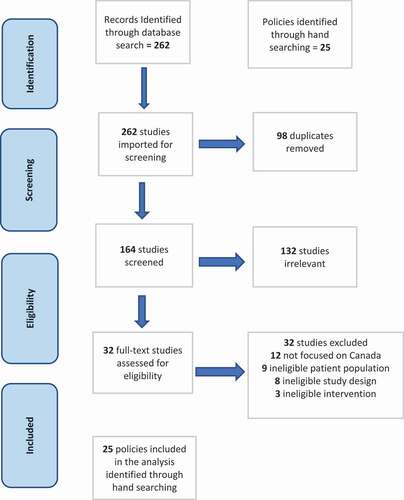

Selection of sources of evidence

We screened 164 titles and abstracts. All documents were screened as per the population, concept and context (PCC). One hundred and thirty-two were excluded as they were not focused on Inuit. The remaining 32 titles were reviewed in full. They were excluded as they did not focus specifically on or include Labrador Inuit or Nunatsiavut, focused on measuring food security, described the concept of food security or evaluated a relevant policy but did not provide the required data parameters required for this review. As none of the documents met the criteria, no documents were identified by the database search. The reviewers were in complete agreement. While not included, these studies identified policies for further exploration in the grey literature. We identified 25 policies through hand searching of various journals, policy documents, and websites. Fulsome policy descriptions were obtained mainly from government websites due need to add in to their role in policy development and implementation. These policies formed the basis of the data extracted and analysed for this scoping review. The results are listed in Diagram A: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension statement for reporting of scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation27].

Characteristics of policies

Twenty-five policies were identified that pertained to food security in Nunatsiavut. Most policies identified were proximal to food security. Fifteen policies (60%) were Government of Canada (federal) policies, seven policies (29%) were the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (provincial) policies, and three (12%) were the Nunatsiavut Government (Inuit) policies. A description of each policy by jurisdiction is in . The policy focus varied by government level. Inuit policies focused on governance and resource management, provincial policies focused on social policies and regulations, and federal policies focused on community-based interventions, regulations and governance.

Table 1. Policy Description and Level of Development

The focus of these identified policies was grouped into five broad areas. There were seven policies for resource management, both wildlife and fish [Citation29–35]; and social policies, specifically income [Citation36–42]. Four policies were related to health [Citation43–46], two policies [Citation47,Citation48] focused on climate change and two policies [Citation49,Citation50] focused on governance. Three policies included food security in their description [Citation43,Citation44,Citation47], with one policy stating it funded local food security projects [Citation43]. The policy characteristics are summarised in .

Table 2. Characteristics of Identified Policies

However, the existence of a policy did not mean that it applied to all Labrador Inuit in Nunatsiavut. This was due to factors such as place of implementation and required criteria to access the stated policy benefit. Three out of 25 (12%) policies were implemented in select communities. These policies included the Innovation Strategy [Citation43], the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities [Citation46], and the Hyperabundant Moose Management Plan 2019 [Citation51].

At times, a policy required that criteria were met before the stated benefit was received. The criterion for 11 policies included either life stage, income or population. Seven policies had a life stage criterion. These policies included the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program [Citation45]; for mothers in the prenatal period, the Mother Baby Nutrition Supplement [Citation37] that is provided in the first year of life for a child, Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities [Citation46]; for the early childhood time frame, the Newfoundland and Labrador Child Benefit supplement [Citation36], and the Canada Child Benefit [Citation42] that can be accessed by families with children until the age of 18. The Newfoundland and Labrador Seniors Benefit [Citation39] and Guaranteed Seniors Income Benefit [Citation41] were available to senior citizens. Income was another separate criterion, as four policies required a low-income to access the benefits. These policies included the Newfoundland and Labrador Child Benefit Supplement [Citation36], the Mother Baby Nutrition Supplement [Citation37], the Income Support Program, Newfoundland and Labrador [Citation38], and the Newfoundland and Labrador Seniors Benefit [Citation39].

Population was a criterion for six policies that were available only to Labrador Inuit. These policies included the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement [Citation49], Inuit Domestic Fishery [Citation29], Wildlife Regulations [Citation30], the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative [Citation44], the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program [Citation45], and the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities [Citation46].

Five policies required meeting more than one criterion. These included two policies, the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program [Citation45]; and the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities [Citation46]; policy that had life stage and population as criteria. Additionally, the latter policy was only available in one community. Three policies, the Newfoundland and Labrador Child Benefit [Citation36], the Mother Baby Nutrition Supplement [Citation37], and the Newfoundland and Labrador Seniors Benefit [Citation39] had life stage and low-income as criteria.

The majority of policies (80%) did not have a time limit. However, there were five time-limited policies. They were the hunting ban on George River Caribou Herd [Citation32], the Hyperabundant Moose Management Plan 2019 [Citation51], the Climate Change Preparedness in the North Program [Citation47], the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program North [Citation48], and the Innovation Strategy [Citation43]. The reasons for the time limitations varied. The hunting ban on George River Caribou Herd [Citation32] and the Hyperabundant Moose Management Plan 2019 [Citation51] were time limited as they are based on assessing the respective wildlife resources. The remainder of the policies were project-based. The majority of the policies (56%) had a stated evaluation plan. Four policies, the hunting ban on George River Caribou Herd [Citation32], the Hyperabundant Moose Management Plan 2019 [Citation51], Nutrition North Canada [Citation52] and the Innovation Strategy [Citation43] specifically stated they had completed evaluations that directed future actions and policy related.

Results

Policy development and implementation varied by the level of government and at times included the private sector. The Government of Canada developed the majority of the policies (60%) and the Nunatsiavut Government developed the least number of policies (12%). All policies were implemented in Nunatsiavut as it was a criterion for inclusion in this scoping review. However, responsibility for the policy implementation varied by level of government and included the private sector. The Nunatsiavut Government was responsible for implementing most of the policies (48%), due to the implementation of community-based programming. The Government of Canada implemented 44% of the identified policies due to their role in implementing policies developed by the provincial government. Both the provincial government and the community-based retailers implemented only one distinct policy each and one policy shared implementation among the Government of Canada and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador.

At times, differing levels of governments were responsible for developing and implementing the same policy. For example, within the federal government policies, seven out of 15 federal policies were developed and implemented by another government. One federal policy, the Innovation Strategy [Citation43] also involved a non-government organisation, Food First Newfoundland and Labrador. Another policy, Nutrition North Canada [Citation52] developed by the Government of Canada, was implemented by private retailers. Also, six of the seven provincial policies were developed by the provincial government and implemented by a federal government department.

The framing of an issue impacts how it is understood and the corresponding policy response [Citation53]. The framing of food security as part of the policy was extracted from the policy description. Food security was explicitly in the description for three of the 25 policies (12%). Two of the policies were framed as health – the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative [Citation44], the Innovation Strategy [Citation43], and the third policy, the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program North [Citation45], was framed as climate change. The Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative [Citation44] was the only policy to include a definition of food security in the broader policy description. Only one policy, the Innovation Strategy [Citation43], which funded local projects, stated the project in Nunatsiavut was focused solely on food security.

For the remainder of these policies the pertinence to food security was implicit and they were framed as six areas. Seven policies focused solely on resource management [Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–35,Citation51], seven policies focused on social policies [Citation36–42] and two policies focused on climate change [Citation47,Citation48]. Two policies focused on governance, one specifically for Nunatsiavut, the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement [Citation49], and the other the Inuit Permanent Bilateral Mechanism–Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee [Citation50] focuses on Inuit in Canada, and more specifically Inuit self-determination. This policy is specifically discussed in the context of the Government of Canada’s commitment to Truth and Reconciliation [Citation54]. One policy was framed as nutrition education [Citation55] and another as market food availability [Citation52].

Each policy was mapped against the primary relevant dimension of food security. For this scoping review, the categorisation for the dimension of food security was based on the primary intent of the policy identified in the description and the definition of the food security dimension. However, six policies spanned more than one dimension and accordingly are included in a separate discussion. The individual policy and the associated dimensions of food security are listed in .

Table 3. Policies and Dimensions of Food Security

Accessibility was the most frequent dimension associated with the identified policies. This dimension states that individuals and households have the adequate economic and physical access to food. This dimension was addressed in nine policies [Citation31,Citation36–42,Citation52] out of 25 (36%). Seven of the nine policies were social policies [Citation36–42], one policy [Citation31] focused on community freezers, and one policy [Citation52] stated it made market food more accessible.

The next most frequent food security dimension was availability. This dimension refers to the quantity of safe and nutritious foods that are consistently available to individuals and meets their tastes and cultural traditions. Seven [Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–35,Citation51] out of 25 policies (28%) were associated with this dimension, due to the focus on making country foods available for harvest.

The utilisation dimension refers to the proper biological use of food to provide sufficient energy requirements, essential nutrients, potable water, and adequate sanitation. This includes the knowledge and skills to prepare and preserve food. Three policies [Citation44,Citation48,Citation55] were associated with this dimension as they specifically provided education and planning. These policies were the Nutrition North Canada retail and community-based nutrition education [Citation55] that focus on “increasing knowledge of healthy eating, developing skills in selecting and preparing healthy store-bought and traditional or country food, and building on existing community-based activities with an increased focus on working with stores”, the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative [Citation44] that states “the program supports appropriate community-led planning to improve access to healthy foods”, and Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program North [Citation48] that supports “communities to develop and implement health-related adaptation or action plans, develop knowledge-building and communication materials, support adaptation decision-making at local, regional and national levels”.

Stability refers to the ability to be food secure in the present and the future, mainly through a reliable supply of food products. No policy was solely associated this dimension. Rather, it was encompassed within other policies that spanned several dimensions.

Four policies spanned two dimensions based on the policy description. The Climate Change Preparedness in the North [Citation47] was associated with accessibility as it included “The Going Off, Growing Strong Project that aimed to make country foods accessible through the community freezers” and utilisation through “initial engagement on a Food Security Strategy for Nunatsiavut” that focused on education and planning. The Innovation Strategy [Citation43] was associated with availability as it included “expansion of the community freezer in Hopedale” and accessibility, as it included “traditional gardening in Hopedale and Rigolet” and the “Good Food Box in Rigolet”. Two community-based programs, the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program [Citation45] and the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities [Citation46]; were associated with accessibility as they provided access to food, and utilisation as nutrition education was a part of their program policy.

Two policies were associated with all of the food security dimensions. These policies, the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement [Citation49]; and the Inuit Permanent Bilateral Mechanism–Inuit-Crown Partnership Committee [Citation50] focused on governance and included a range of areas that pertain to food security and were considered inclusive of all the food security dimensions.

Discussion

To date, policy research on food security and Inuit in Canada have demonstrated that “a more multi-faceted approach is required” to address food security for Inuit in Canada [Citation15], and specifically in Nunavut, that more work needs to be undertaken to meet the pillars of food security [Citation56]. Recognising that each Inuit region is unique, this scoping review focused on identifying food security policies that pertained to Nunatsiavut, Labrador as it is a gap in the current literature on policy and food security and mapping the identified policies against the food security dimensions.

This scoping review identified 25 policies that pertained to food security to Nunatsiavut. The majority of these policies focused on proximal factors for food security. To varying degrees, the content of the identified policies addressed food security dimensions. However, the stability dimension was never addressed in isolation of the other food security dimensions, but rather as a part of a policy. The scoping review results highlighted the breadth of policies, areas of emphasis in food security dimensions and advances in Inuit participation and governance of policies that pertain to food security and the need for further evaluation of policies.

Mapping policies against food security dimensions demonstrated both the breadth of policies and areas of policy emphasis. The accessibility dimension was the most frequently associated food security dimension with the identified policies. These policies made country and market food accessible or they provided financial resources to purchase foods. Three of these policies Climate Change Preparedness in the North [Citation47], Labrador Nutrition and Artistic Allowance [Citation31], and the Innovation Strategy [Citation43], aimed to make country foods accessible through support of community freezers. It was unclear from the descriptions if these policies were augmenting or duplicating efforts. Only one policy associated with this dimension, Nutrition North Canada [Citation52], focused on making market foods more accessible as the policy was “dedicated to ensuring accessible market foods”. The remaining policies associated with this dimension were social policies focused on providing income to purchase food. These social policies focused on distinct populations, namely women and children and senior citizens. The life stage approach to these policies is consistent with the literature on populations more at risk for not being food secure [Citation57] and has been a focus of previous research [Citation15].

Availability of food was the next most frequent dimension identified. The majority of these policies focused on resource management that impacts the availability of country foods. Country food is a term that describes “traditional Inuit food, including game meats, migratory birds, fish and foraged foods, and is an integral part of Inuit identity and culture” [Citation58]. Policies identified with this dimension were consistent with other studies that have stated the availability of country foods is “influenced by the environment and ecological conditions that shape the health, abundance, distribution and migration of wildlife populations” [Citation59]. It also reflects the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement [Citation49] that identifies Inuit rights to land and resources that provide country foods. Policies associated with the availability dimension were coordinated across all three levels of government and provided the best example of policy coherence. Food safety policies were considered a gap in this dimension. They are a part of the availability dimension, yet no food safety policies were noted in this review.

Only three policies [Citation44,Citation48,Citation55] addressed the utilisation dimension, which includes health education. The least amount of sole focus on health education and planning may be attributed to a change in understanding of factors impacting food security among Inuit [Citation60] and accordingly a fundamental shift from a personal issue that promotes individual responsibility [Citation53] to a population health issue.

In this review, based on the policy description, no policy solely addressed stability. Stability is important as it impacts a person’s sense of agency and it is required to break the cyclical nature of not being food secure. In fact, stability is required “to ensure that a population, household and individual do not risk losing access to food as a consequence of sudden shocks or cyclical events” [Citation20,Citation61]. However, stability is considered a cross cutting function, as it is included in both access and availability dimensions over time. It is for this reason that stability was included as a dimension in policies that supported overall governance as these policies spanned more than one area. Therefore, the lack of focus on stability identified in this scoping review may not be due to the policy intent, but rather, interpretation of the policy description.

The availability or accessibility dimension was addressed in 64% of the total policies. This focus is more consistent with food insecurity and specifically household food insecurity, defined as “the inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints” [Citation11]. The high percentage of results focusing on access and availability from this study is consistent with results from a synthesis of food security initiatives in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Northwest Territories, Canada, that identified 30 initiatives and mapped each initiative against applicable food security dimensions [Citation59]. However, the results differ from another systematic review on food security dimensions and transitional food security in Alaska [Citation62]. Utilisation was cited as the most common dimension in that particular study. These differences in study findings can be attributed to the scope of the study, namely the focus on health impact of traditional food security, which was not included in this scoping review.

Governance for food security is cited as an important factor for food security efforts on a national and international scale. However, these efforts are not without associated challenges such as a high degree of complexity, coherency and coordination, conflict of ideas, and the allocation of sufficient resources [Citation63]. Two policies pertained to governance, one is Nunatsiavut specific [Citation49] and another is national in scope and includes all Inuit land claim areas [Citation50]. The latter is a partnership and is described as part of Canada’s commitment to Truth and Reconciliation [Citation54]. This includes the national Inuit Crown Food Security Working Group that focuses on food security and working towards a sustainable food system [Citation64].

Inuit self-determination involves participation in both making and implementing policy. Documentation of Inuit participation has demonstrated progress in this area. For example, no Inuit organisations were listed as participants in Canada’s Action Plan for Food Security developed in 1998 [Citation65]. In 2019, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami led their own consultation and submitted a full response to the national food policy consultation instead of just participating in broader discussions [Citation66]. In this scoping review, the Nunatsiavut Government developed 12% of the identified policies and implemented 48% of the identified policies. The lower number of policies developed by the Nunatsiavut Government can be attributed to the fact that Nunatsiavut is a relatively new government and inherited many policies that were developed prior to the land claims agreement in 2005. However, they were already implementing these inherited policies as part of broader Indigenous health programming.

Policy implementation was the greatest area of progress for the Nunatsiavut Government. In 2008, Canada’s Fifth Report on the Food Security Action Plan reported four Aboriginal specific domestic programmes [Citation67]. The Nunatsiavut Government is currently implementing these four health-related policies [Citation44–46,Citation52] from the Action Plan Report and other policies that span a greater breadth of areas beyond health. These advances in policy implementation for food security can create an interesting dilemma for the Nunatsiavut Government, as they are accountable for the policy outcomes to their members and other governments. This can present a contextual challenge for the Nunatsiavut Government and other Inuit governments in Canada as they implement the legacy of historical policies, while at the same time are striving to determine future policies for food security through their governance structures. How the Nunatsiavut Government and Inuit in Canada overcome these implementation and governance challenges can be a learning experience for other Indigenous peoples, on both a national and international level.

If it existed, the evaluation plan for each policy was noted. However, it was assumed that the evaluation plan corresponded to the outcomes for each policy and not necessarily the impact on food security, or furthermore, food security of Labrador Inuit within Nunatsiavut. Evaluation was acknowledged as a limitation when describing food security initiatives in other Inuit regions within Canada [Citation59]. A fulsome review of each policy evaluation was beyond the scope of this study. However, this remains an important area of further investigation as it will provide a greater understanding of the policy impact and assist with a broader assessment as to whether or not the policy is fair or just.

Strengths and limitations

This study provided a more fulsome overview of policies that pertain to food security in Nunatsiavut. The strength of this study is that it provides an overview of a breadth of policies that pertain to food security in Nunatsiavut and serves as a starting point for further discussion on policy and food security. However, there were limitations to this study, namely the generalisability of findings, the search terms strategy and interpretation of policy descriptions, that impacted the scoping review results.

This study focused on Nunatsiavut, and more specifically, Labrador Inuit. The scoping review findings may not be generalisable to other Inuit land claim areas or Indigenous peoples in Canada. This scoping review only included policies that pertained to Nunatsiavut. This population criterion may have excluded more distal policies for food security that pertain to the broader Labrador Region of the province, the province of Newfoundland and Labrador as a whole, or it could be indicative of a policy gap.

The variation in detail of activities was a limitation as some policies provided descriptions of activities within Nunatsiavut, and others did not provide the same level of detail. This could have impacted the association of the policy with one or more of the food security dimensions. Another challenge related to description was the policy name and associated activities changed over time. Examples included social policies such as the Newfoundland and Labrador Income Support Supplement [Citation38], Newfoundland and Labrador Seniors Benefit [Citation31], and the Newfoundland and Labrador Child Benefit [Citation37] changed their rates over time. The Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative [Citation44] changed in focus for each phase and only explicitly mentioned food security in the third phase. The Nutrition North Canada subsidy [Citation52] was previously the Food Mail Program and the Labrador Aboriginal Nutrition and Artistic Allowance [Citation31] changed from the Air Foodlift Subsidy Program to the coast of Labrador [Citation68]. This challenge was overcome through utilising the most recent description of the policy. However, it shows that policies are not static, and appeared to be influenced by political context and at times, policy evaluation.

Finally, the intent of a scoping review is to map the information, which in this scoping review was to identify policies. Therefore, validating policy implementation within Nunatsiavut was beyond the scope of this review. This is a required future step to understand the policy implementation activities and validate the association of policies with food security dimensions.

Conclusion

This scoping review contributes to filling the gap in the literature on policy and food security in Nunatsiavut.The breadth of policies, and levels of government identified, and variety in policy development and implementation, underscore the complex policy space that must be navigated by the Nunatsiavut Government and Labrador Inuit. This scoping review demonstrated that for Inuit, it is not only the policy framing and focus, but also how the policies support Inuit governance, and self-determination on a regional and national level. This is perhaps the most important aspect of food security policies for Inuit in Canada and within the circumpolar region.

The scoping review findings can inform the efforts of policy actors within and outside of Nunatsiavut, and the broader research community in their future research, policy and advocacy actions. Future areas of investigation remain for policies that pertain to food security such as determining the distal policies for food security and evaluating policies currently in place in Nunatsiavut. The latter will contribute to understanding the policy impact; and potentially to the broader conversation as to whether or not the policy is fair or just. It is hoped continued efforts are undertaken to build a more fulsome understanding of the food security puzzle in Nunatsiavut and improve the health and well-being of Labrador Inuit.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study would like to acknowledge the Labrador Inuit Lands.

Gail Turner, Nunatsiavut Beneficiary Member, Quebec City, Quebec, Canada.

Ian D. Graham, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario.

Chris Furgal, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario, Canada.

Lise Dubois, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Disclosure statement

There are no disclosures for this scoping review.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. About Canadian Inuit [Internet]. Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (CAN); n.d. [cited 2019 Sep 12]. Available from: https://www.itk.ca/about-canadian-inuit/

- Inuit Circumpolar Canada [Internet]. n.d. [cited 2019 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/

- Government of Canada. Land claims agreement between the Inuit of Labrador and her majesty the queen in right of Newfoundland and Labrador and her majesty the queen in right of Canada [Internet]. n.d. [cited 2019 Feb 11]. Available from: https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1293647179208/1293647660333

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Inuit statistical profile 2018. Ottawa, Canada; 2018. Report No.: ISBN: 978–1–989179–00–0.

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Social determinants of Inuit health in Canada. Ottawa: Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; 2014.

- Furgal C, McTavish K, Martin R and IHACC Research Team. The importance of scale in understanding and addressing Arctic food security. Arctic Change, International Conference; 2017 Dec, Quebec City, Canada. [Presentation, Abstract].

- Tarasuk V, Mitchell A, Dachner N. 2014. Household food insecurity in Canada, 2012 [Internet]. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Available from: https://proof.utoronto.ca/

- Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(3):380–19.

- Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Almeida-Filho N. A glossary of health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(9):622–623.

- Richards D, Smith MJ. Governance and public policy in the UK. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

- Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Food insecurity policy research. 2017 [cited 2019 Feb 6]. Available from: http://proof.utoronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/monitoring-factsheet.pdf

- Loopstra R, Dachner N, Tarasuk V. An exploration of the unprecedented decline in the prevalence of household food insecurity in Newfoundland and Labrador 2007–2012. Can Public Policy. 2015;41(3):191–206.

- McIntyre L, Dutton DJ, Kwok C, et al. Reduction of food insecurity among Low-income Canadian seniors as a likely impact of guaranteed annual income. Can Public Policy. 2016;42(3):274–286.

- May CL, Hamill C, Rondeau K, et al. A critical frame policy analysis of response to the World Food Summit 1998–2008. Arch Public Health. 2014;72:41.

- Ferguson H. Inuit food (in) security in Canada: assessing the implications and effectiveness of policy. Queen’s Policy Rev. 2011;2(2):54–79.

- United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the right to food, A/HRC/22/50/Add.1 [Internet]. 2012 Dec 24 [cited 2019 Apr 13]. Available from: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/RegularSession/Session22/AHRC2250Add.1_English.PDF

- National Indigenous Economic Development Board [Internet]. Recommendations on Northern sustainable food systems. 2019 Feb [cited 2019 Apr 13]. Available from: http://www.naedb-cndea.com/reports/NORTHERN_SUSTAINABLE_FOOD_SYSTEMS_RECOMMENDATIONS%20REPORT.pdf

- Gordon Foundation [Internet]. Recommendations on Country/traditional foods from the Northern Policy Hackathon. 2017 [cited 2019 Apr 13]. Available from: http://gordonfoundation.ca/initiatives/northern-policy-hackathon/

- Nunatsiavut Government [Internet]. Healthy individuals, families and communities, regional health plan 2013–2018, Department of Health and Social Development. [ cited 2019 Jun]. Available from: https://www.nunatsiavut.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/DHSD-Regional-Health-Plan-2013-2018.pdf

- Food and Agricultural Organization [Internet]. An introduction to the basic concepts of food security. Food security for action practical guides. Rome, Italy. EC-FAO food security programme; 2008. Available from: http://www.fao.org/3/al936e/al936e00.pdf

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Methodology for scoping reviews: Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual: 2015 edition/supplement. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2015.

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

- Bowers R, Turner G, Graham ID, et al. Piecing together the Inuit food security policy puzzle in Nunatsiavut, Labrador (Canada): protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e032601.

- Porta M, editors. A dictionary of epidemiology. 5th ed ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

- de Leeuw E, Clavier C, Breton E. Health policy - why research it and how: health political science. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:55.

- Sassi M. Understanding food insecurity key features, indicators, and response design. New York: Springer International Publishing AG; 2018.

- Tricco AC, Lillie A, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Inter Med. 2018;169(7):467–473.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288.

- Nunatsiavut Government [Internet]. Inuit domestic fishery. n.d. [cited 2019 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.nunatsiavut.com/beneficiary-information/fisheries/

- Nunatsiavut Government [Internet]. Wildlife: A resource for Generations. n.d. [cited 2019 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.nunatsiavut.com/beneficiary-information/wildlife/

- Labrador Affairs Secretariat [Internet]. Happy Valley-Goose Bay. Labrador aboriginal nutritional and artistic assistance program. 2017 Feb 22 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.gov.nl.ca/ola/grantsprograms-we-offer/labrador-aboriginal-nutritional-and-artistic-assistance-program/

- Environment and conservation executive council hunting Ban announced on George River Caribou Herd [Internet]. 2013 Jan 28 [cited 2019 Jul 15]. Available from: https://www.releases.gov.nl.ca/releases/2013/env/0128n08.htm

- Wild life regulations 1156/96 [Internet]. 2018 Nov 15 [cited 2019 Jul 25]. Available from: https://www.assembly.nl.ca/Legislation/sr/Regulations/rc961156.htm

- Marine Mammal Regulations SOR/93–56 [Internet]. 2018 Nov 2 [cited 2019 Jul 20]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/SOR-93-332/index.html

- Migratory Birds Convention Act (MBCNA) and Regulations [Internet]. c2004. 2019 Jul 5 [cited 2019 Jul 12]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/migratory-birds-legal-protection/convention-act-regulations.html

- Department of Immigration, Skills and Labour [Internet]. St. John’s. Newfoundland and Labrador Child Benefit Supplement. [2019 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.gov.nl.ca/isl/income-support/child/

- Department of Immigrations, Skills and Labour [Internet]. St. John’s. Mother Baby Supplement. [ cited 2019 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.gov.nl.ca/isl/income-support/nutritionsupplement/

- Department of Immigration, Skills and Labour [Internet]. St. John’s. Income Support Program [ cited 2019 July 19]. Available from: https://www.gov.nl.ca/isl/income-support/overview/

- Department of Finance, Fiscal and Economic Policy Branch [Internet]. St. John’s. Newfoundland and Labrador Seniors Benefit. [ cited 2019 Jul 19]. Available from: https://www.fin.gov.nl.ca/fin/tax_programs_incentives/personal/income_supplement.html

- Employment and Social Development Canada [Internet]. Ottawa: the Government of Canada; c2019. Employment Insurance Benefits; 2019 May 28 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/ei/ei-regular-benefit.html

- Government of Canada [Internet]. Ottawa. Guaranteed Seniors Income Benefit. 2018 Dec 4 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/benefits/publicpensions/cpp/old-age-security/guaranteed-income-supplement.html;https://www.fin.gov.nl.ca/fin/tax_programs_incentives/personal/income_supplement.html

- Canada Revenue Agency [Internet]. The Canada child Benefit. Ottawa. [ cited 2019 Jul 31]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview.html

- Public Health Agency of Canada [Internet]. The Innovation Strategy. 2018 Feb 5 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/innovation-strategy/healthier-weights.html

- Indigenous Services Canada [Internet]. The Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative. 2011 Sep 26 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/indigenous-services-canada/services/first-nations-inuit-health/reports-publications/diseases-health-conditions/aboriginal-diabetes-initiative-program-framework-2010-2015-health-canada-2011.html#a7.1

- Indigenous Services Canada [Internet]. Canada Prenatal nutrition program - first nations and Inuit components. 2019 Jul 5 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/canada-prenatal-nutrition-program-cpnp.html

- Public Health Agency of Canada [Internet]. Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC). 2017 Oct 23 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/childhood-adolescence/programs-initiatives/aboriginal-head-start-urban-northern-communities-ahsunc.html

- Crown and Indigenous Northern Affairs Canada [Internet]. Climate change preparedness in the North 2018. 2019 Jun 14 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/eng/1560543974844/1560544001045#c5

- Indigenous Services Canada [Internet]. Climate change and health adaptation program north. 2018 Sep 12 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1536238477403/1536780059794

- Labrador Inuit land claims agreement Act S.C.2005, c27 [Internet]. 2019 Jun 20 [cited 2019 Jul 20]. Available from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/L-4.3/index.html

- Crown and Indigenous Northern Affairs Canada [Internet]. Inuit permanent bilateral mechanism – inuit-crown partnership committee. 2018 apr 3 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1499711968320/1529105436687

- Parks Canada [Internet]. Hyper-abundant moose management plan 2019. Ottawa. [ cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/pn-np/nl/grosmorne/info/plan/ebauche-draft–2019

- Crown and Indigenous Northern Affairs Canada [Internet]. Nutrition North Canada. 2018 Dec 10 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1415538638170/1415538670874

- Bastian A, Coveney J. The responsibilisation of food security: what is the problem represented to be? Health Sociol Rev. 2013;22(2):162–173.

- Government of Canada [Internet]. Delivering on truth and reconciliation commission calls to action. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1524494530110/1557511412801

- Indigenous Services Canada [Internet]. Nutrition North Canada retail-based intervention. 2019 Jan 24 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: https://www.nutritionnorthcanada.gc.ca/eng/1415548276694/1415548329309

- Myers M, Powell S, Duhaime G. Setting the table for food security: policy impacts in Nunavut. Can J Native Stud. 2004;XXIV(2):425. Available from: https://arctichealth.org/media/pubs/295952/cjnsv24no2_pg425-445.pdf

- Sarkar A, Traverso M, Gadag V, et al. A study on food security among single parents and elderly population in St. John’s. Canada: Memorial University of Newfoundland, St John’s, NL; 2015.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia [Internet]. Country Food (Inuit Food) in Canada. 2019 Jul. Available from: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/country-food-inuit-food-in-canada

- Kenny TA, Wesche SD, Fillion M, et al. Supporting Inuit food security: a synthesis of initiatives in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Northwest Territories. Can Food Stud. 2018;5(2):73–110.

- Council of Canadian Academies. Aboriginal Food Security in Northern Canada: an Assessment of the State of Knowledge, Ottawa, ON. The Expert Panel on the State of Knowledge of Food Security in Northern Canada, Council of Canadian Academies; 2014.

- OECD. Managing Food Insecurity Risk: analytical Framework and Application to Indonesia. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.p. 15–24. Chapter 1: Food Insecurity: Concepts, measurement and causes. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264233874-4-en.

- Walch A, Bersamin A, Loring P, et al. A scoping review of traditional food security in Alaska. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2017;77(1):1419678.

- Candel JJL. Food security governance: a systematic literature review. Food Secur. 2014;6:585–601.

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada [Internet]. Government of Canada announces improvements to Nutrition North Canada including support for country food. 2018 Dec 10. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/crown-indigenous-relations-northern-affairs/news/2018/12/government-of-canada-announces-improvements-to-nutrition-north-canada-including-support-for-country-food.html

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada [Internet]. Canada’s Action Plan for Food Security. 1998 [cited 2020 Jan 10]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2013/aac-aafc/A2-190-1999-eng.pdf

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami [Internet]. An Inuit Specific Approach for the Canadian Food Policy. 2017 Nov. Available from: https://www.itk.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/ITK_Food-Policy-Report.pdf

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada [Internet]. Canada’s Fifth Progress Report on Food Security. 2008 [cited 2020 Jan 10]. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2009/agr/A22-492-2009E.pdf

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador [Internet]. Provincial government announces new Labrador Aboriginal Nutritional and Artistic Assistance Program. 2016 Apr 16 [cited 2019 Jul 28]. Available from: https://www.releases.gov.nl.ca/releases/2016/exec/0419n03.aspx

Appendix A.

Search Terms

Search terms used:

aborigin*

american

ancestry

arctic

care

central

circumpolar

continental

environmental

first

fiscal

food

group

group*

health

indians,

indigenous

individual*

insecurit*

inuit

inuits

metis

nation*

native

north

nutrition

nutrition*

oceanic

people*

person*

policies

policy

public

reform

region*

regions

right*

securit*

south

supply

tribe*