?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In Finland, national and local restrictions were implemented to control the COVID-19 pandemic after the increase of cases, and it changed the everyday life of people. The purpose of our study was to explore public health communication and compliance related to the COVID-19 public health instructions, recommendations, and restrictions in two municipalities in Northernmost Finland, Inari and Utsjoki. We interviewed the representatives and operators working in the municipalities to understand and learn about their experiences. Results suggested that residents complied with different COVID-19 actions, and overall, communication was found to be good. Altogether, guidelines were easy to follow but required the individual’s own activity. Guidelines were also published in Sámi language. National border restrictions were a challenging part of communication and information, and guidelines were found to be contradictory at times. National border actions required resources from the municipalities, e.g. testing, which caused more demands on municipalities operating with already low resources. In the future, it is essential to consider the local situation of the pandemic and harmonise actions and put effort on local cooperation. It is important to invest in clear communication, which reaches people of all ages, and in three Sámi languages.

Introduction

The first COVID-19 infection in Finland was identified in the end of January 2020 in the municipality of Inari, Northern Finland. Cases started to spread in the beginning of March, leading the Finnish Government to declare a state of emergency [Citation1]. National restrictions, e.g. closure of public premises, educational institutes, restaurants, remote work, when possible, remote studying, quarantine in case of a positive COVID test or exposure, and lockdown of Southernmost Finland, were implemented against the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation1,Citation2]. In May, the strictest restrictions were dismantled, but testing and quarantine, social distancing for risk groups and in public places, and high hygiene standards remained. Moreover, full service of restaurants and inside events with over 500 people were possible in July 2020. During the pandemic, relevant COVID-19 restrictions were renewed when necessary, depending on the region [Citation1].

The national, overall COVID-19 situation was monitored by the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, which guided health authorities. Regional State Administrative Agencies (altogether six in Finland) regulated COVID-19 actions in their own regions, and ensuring that hospital districts and municipalities prepared for COVID-19, but they were also able to make some decisions, e.g. concerning public events. During the years of this study, Finland had 20 hospital district areas whose responsibility was to harmonise and coordinate COVID-19 situations for local needs [Citation3,Citation4]. Moreover, municipalities completed these actions, but were also able to set their own, specific restrictions when necessary. In September 2020, local area COVID-19 coordinating groups were implemented by hospital districts, which included different authorities, e.g. from hospital districts, municipalities, and Regional State Administrative Agencies, and they coordinated local COVID-19 actions [Citation4]. The earlier governmental level of control against the pandemic was transferred to the regional/local level, becoming more decentralised [Citation5,Citation6].

Northernmost Finland is part of the Sámi homeland area, with borders to Norway and Russia. The Sámi homeland is seen as one area for Sámi people, supporting traditional culture and lifeways, and with open borders between Norway, Sweden, and Finland. Scandinavian countries have agreed on free movement between countries. However, Finland, among other countries, implemented national internal border restrictions to control the pandemic. This had an impact on people living close to borders between Finland and Sweden/Norway as crossing the borders was only possible for necessary reasons, e.g. essential work. During the pandemic, situations varied, and countries prepared individual guidelines for borders [Citation7].

Moreover, the tourism business is important for the area [Citation8]. The COVID-19 situation remained better in Northernmost Finland, compared to Southern Finland, until the early winter of 2022 due to the Omicron variant that caused clear increase of confirmed cases in North too [Citation9]. Southern Finland is highly populated area compared to Lapland providing more favourable situation for the virus to spread. Overall, until the date of 15 November 2023, Lapland hospital district area has reported just over 22 000 confirmed COVID-19 cases, while Helsinki and Uusimaa hospital district area (capital region) had over 570 000 confirmed cases (9) During the whole COVID-19 pandemic, it was important to inform the public about the changing situation and necessary guidelines. They were publicised e.g. via webpages (e.g. health operators, municipalities), national and local newspapers, radio, and television.

Material and methods

Aim and purpose

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore public health communication and compliance related to COVID-19 public health instructions, recommendations, and restrictions in two municipalities in Northernmost Finland. The aim was to gather information from the representatives and operators working in municipalities to understand and learn about their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding about the communication, internal and external, and moreover, compliance of it will create a description of how municipalities, different operators in municipalities and residents experience pandemics and the guidance related to it. Additionally, it will also support the development work and preparedness, e.g. health and social care for the future. Successful communication and handling the pandemic will provide an equal situation for all, supporting their health in a meaningful way.

Study participants and data collection

Data was collected by conducting qualitative interviews in two municipalities, Utsjoki and Inari, during December 2021 – February 2022. Study participants (9 men and 10 women) were working in various positions, such as health and social work, administration, education, culture, economics, business, tourism, communication, and voluntary work. Participants worked in public and private sector. One interview was a group interview, including seven men and six women. Participants were both Sámi and Finnish, however, the individuals’ personal information was not recorded. Instead, the interviews recorded the individuals’ positions as an operator or representative working in the municipality. Interviews were completed in Finnish. The final sample, 20 interviews, formed as follows: interviewees were selected based on a structure of the municipality, keeping in mind different representatives and operators working in these municipality areas. As the data collection continued, researchers learned from the completed interviews and reached out different representatives in order to gather comprehensive sample from different perspectives.

The average duration of the interview was 45–60 minutes, carried out by the authors of this paper. Participation was voluntary, with a right to terminate the process at any stage. Information about the study was orally presented by the researchers and consent forms were signed. All interviews were jointly agreed to be recorded. The data have been stored securely, and only the authors have access. Each interview was renamed with a specific research ID to protect the anonymity of participants. Interviews were transcribed by a research assistant. This study did not require an ethical review by the University of Oulu Human Science Ethics Committee (Finland). A risk assessment/data protection impact assessment was performed, and all participants were provided with a privacy statement for the scientific research.

A theme interview was conducted with all participants to gather information from the perspective of representatives/operators related to instructions, recommendations, and/or restrictions:

receiving information

compliance to

informing and communicating/being responsible for informing and communicating

specific issues related to Sámi identity or culture

implications for the future

Data analysis

Data was analysed by following qualitative inductive content analysis. The following research questions guided the analysis:

How has it been to follow public health instructions, recommendations, and restrictions?

What has been your experience of the informing and communication processes?

What kind of issues related to Sámi identity or culture need to be considered?

What needs to be considered for the future?

As guided by Elo and Kyngäs [Citation10] and Lindgren and colleagues [Citation11], the analysis started by reading the data through frequently. Then, open coding was completed by writing down codes throughout the data. Coding sheets were created, based on the written codes, and subcategories were constructed by grouping codes that presented the same content. The researcher checked the original data every time if the content of the code was unclear. This verified that each code was allocated to the correct subcategory, retaining the original context. Finally, these actions were followed by grouping the created subcategories to categories, and further to generic categories. At last, the main category was developed based on the generic categories, which closed the abstraction process. Categories in each step were given a name that described the content.

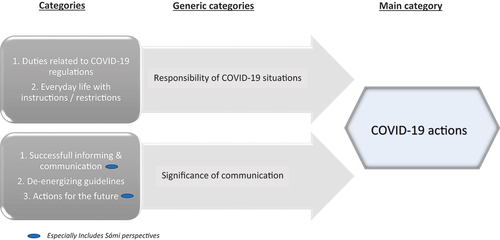

Codes that emerged from the data, which answered specifically to the research question of Sámi identity and culture, were grouped to separate categories (see ).

Table 1. Categories, created from sub-categories, presenting the results of informing & communication and compliance of restrictions.

Results

COVID-19 actions

The main category “COVID-19 actions” is presenting the main result of the content analysis and was formulated in the process of creating two generic categories and five categories (See ). The results are presented based on these five categories: 1) Duties related to COVID-19 regulations; 2) Everyday life with instructions/restrictions; 3) Successful communication; 4) De-energising guidelines; and 5) Actions for the future (). Moreover, five categories included altogether 16 sub-categories, which are sh own in .

Duties related to COVID-19 regulations

COVID-19 actions were considered as an extra function that needed to complete despite of all regular functions and actions. They required new testing activities on borders and municipalities, but also demanded new documents that had to be checked from customers of variety of services or tourism, and infrastructure had to support these actions. However, there was a lack of resources and staff to keep up with all these new demands; the existing resources in municipalities and among operators were limited to sustain the new activities. This was especially a problem during the winter season due to the high number of tourists, as resources were already stretched. The pandemic challenged already vulnerable staff resources in health care as staff were heavily loaded, and many times only critical care could be ensured. The role of health care professionals was essential when planning, completing, and informing about COVID-19-related actions. This co-operation was experienced to be important and functional. Additionally, staff working in the tourism business, for example, were not necessarily available due to a change of working place or layoffs after the first wave of COVID-19.

Everyday life with instructions/restrictions

Many levels of recommendations and restrictions were experienced in these regions. For example, the pandemic situation in Lapland remained good compared to southern Finland, and often municipality recommendations for COVID-19 actions were enough, people followed them. On the other hand, it was experienced that many varieties of directions on many levels, e.g. national, Lapland, local, and organisational, had to be followed and, define whether there is a need for recommendation or restriction. Local co-operation with Local areal COVID-19 coordinating group and regular meetings between different organisations and operators e.g. Regional State Administrative Agencies, hospital districts, were important and took place when necessary. People wore masks, used hand disinfectant, and worked/studied remotely when advised. Plastic or glass walls and social distancing were used in customer service, and at times, certificates of vaccinations were also required. The tracing system and vaccinations were common actions to control the pandemic, and borders between Norway and Finland, which were usually open, were closed. All these became a part of everyday life; participants experienced that people saw them as important and took responsibility for their own actions. Vaccinations were seen as essential, especially among elders. However, following all the guidelines and acting based on them required one’s own responsibility. Situations changed quickly, which demanded people to be constantly alert to know which guidelines and recommendations were current. This was challenging, especially at the beginning of pandemic, but also when the flow of information was fast and plentiful, or if it was unclear where one could confirm the information.

Successful communication

Despite the high media interest in the first COVID-19 case in Finland, participants experienced that overall, the information and communication were clear, coherent, and reached people. Different operators and organisations, e.g. workplaces took responsibility during the pandemic, and information was shared through many sources e.g. online, emails, and information letters. People shared knowledge with others, and professional, centralised communication was found to be important. Traditional media, newspapers, television, and radio were important information sources for people, especially for elders. However, online communication, e.g. webpages of municipalities, health providers, organisations (incl. media), and social media, was seen as very powerful, easy, and a fast option to inform and communicate pandemic-related actions. Both, traditional and online media, were also available in Sámi language. Participants recognised the importance of information sharing in Sámi languages, which is based on law. There are three Sámi languages in these municipalities, which should be used in communications, but many times only the Northern Sámi language was used due to the quickly changing situation and urgency. Often, communication was in both Finnish and Sámi. Information in Sámi language was not seen as an actual problem, and different Sámi organisations helped with the translation, which was important. Still, especially at the beginning of the pandemic, agencies had to be reminded to provide information in Sámi.

De-energizing guidelines

There were not only experiences of unclearness related to instructions and contradictory guidance for borders, but also criticism towards given restrictions. The guidance at the beginning of the pandemic was felt to be unclear and the pandemic situation varied a lot, not only within the Lapland Hospital District, but also in the whole of Finland. Often, the national discussion did not fit to the situation in the North, and that was found to be confusing. Discussions at the e.g. governmental/national/local level and related to business and tourism, were sometimes felt to be contradictory. There were experiences that legislations of restrictions were conducted too fast, resulting in different interpretations. Many documents, e.g. vaccination documents, were only available online. This caused problems for some, especially people living remotely with no internet access, or elders without access to an online bank with secure identification, which was needed to access these online documents.

Unclear and contradictory national border actions were highlighted among participants. It was experienced that guidelines were made in the capital region and did not suit the local situation. Borders were open on and off; Norway and Finland assessed the pandemic differently and the country situation did not necessarily reflect the local situation, especially when COVID-19 rates were low in these municipalities compared to national rates. Informing and communicating about the border statuses was not clear, and Norway made its own, quick decisions that required constant awareness. At times, it was unsure who needed to be tested at the border and which documents were required, and people asked others whether the borders were open. Border community was defined during the pandemic, which was meant to help boarder communities in their everyday life and passing boarders more easily, but it necessarily reaches all communities that local saw important. Participants also expressed critical thoughts towards guidelines and restrictions, and they were tired of following them, especially youth. It was felt the information was not necessarily valid; using masks or other protections negatively influenced communication between people and overall, people became frustrated towards the whole pandemic and all the activities that were completed online.

Actions for the future

Overall, if a similar situation occurs in the future, informing and communication should be improved. Information should be easily accessible to all people; in particular, an effort should be made to ensure oral guidelines are clear, and they should be available in the local language. The traditional ways of informing are still important; people should be able to ask for additional information easily, and professionals working together should have a mutual understanding, including the requirements for specific documents from customers, e.g. vaccination documents. All this should be available in all three Sámi languages, and situations should be avoided where only Finnish and one Sámi language are used. Still, it is not clear if the legal requirements of informing in Sámi language were met. This should be investigated and developed, if necessary, for future activities Sámi language was seen as an important element to support identity and culture.

Discussion

Participants felt that people followed the given COVID-19 instructions well, and often there was no need to set restrictions – recommendations were already followed. People were more likely to comply with the given COVID-19 guidelines when they trusted the information source, e.g. government or health operator [Citation12–14]. Willingness to adhere increases if one trusts authorities’ information [Citation15], has a feeling that the given actions are effective [Citation12,Citation16], that the instructions protect them and others, and that everyone is taking them seriously [Citation16]. People can tolerate some discomfort and modify behaviour when needed [Citation12,Citation16]. Still, necessary public health actions with a minimal negative impact on individuals should be utilised first, and guidelines should be avoided that cause serious discomfort, e.g. economic, or social effects; these, in turn, can decrease compliance [Citation12]. Moreover, people should be supported to comply with the given guidance [Citation13].

Easy, reachable information [Citation16] and clear, rational communication [Citation12,Citation16] support compliance. For example, social distancing [Citation16,Citation17], hand washing [Citation16], and using face masks [Citation17] have found to be easy actions to accomplish. Based on our results, participants experienced that overall, information provided by different operators was easy to follow as a worker but also as a resident; however, they required constant awareness: guidelines had to be actively followed, and at times it was challenging due to the quick flow of information. Hylan-Wood and colleagues [Citation13] point out that communication styles and modes differ between different social groups and communities. When communicating COVID-19-related actions, various communication and media sources should be used to reach people of different ages, ethnicities, and abilities. In our study, elderly people were seen as a vulnerable group that did not necessarily have access on online information. Moreover, the information was not always provided clearly enough; oral instructions were seen important. Although social media was an essential communication channel, traditional ways, e.g. radio or TV, were also highlighted. Media has an essential role in crises to broadcast news and information to the public, and it is an important tool for responsible professionals and agencies [Citation18]. Social media, e.g. twitter, has been found to be a fast and efficient way to share COVID-19 information [Citation19–21], but at the same time, social media can be a platform for users to share misinformation [Citation22,Citation23].

Communicating in Sámi was also required in these municipalities, based on the Sámi Language Act [Citation24]. This right was recognised among participants and in the official information, e.g. provided by municipalities. It was acknowledged that communication actions could have been even better, which should have contributed to traditional culture. Moreover, residents of these municipalities were impacted by changing border restrictions that required constant awareness, as found in this study and by Heinikoski and Hyttinen [Citation7]. People living in national border communities had a special right to cross the borders, until this exemption was removed in January 2021 [Citation25]. Overall, people had to follow border restrictions that, for example, kept it closed at times, or entry was possible with a negative test result. Countries made independent decisions based on different criteria, e.g. assessment of the pandemic based on the whole country/region, and coordination between countries was minimal [Citation7]. In COVID-19-related communication, local values, and experiences, that may vary due to different impacts and communities, should be listened [Citation13].

Guidelines were provided on many levels, e.g. national, regional, and local, and these had to be adapted to meet local needs. This demanded resources from organisations and municipalities, which was especially demanding for municipalities that already operated with low resources. COVID-19 tests had to be provided to residents, tourists, and borders, including the infrastructure around it; this placed an extra burden and costs on municipalities. Moreover, the shift from governmental to local level in the management of COVID-19 May have increased the pressure on municipalities. Although local coordination was important, a clearer governmental role would have been beneficial [Citation6]. Operators/politicians at the national level were experienced still to impact on regional/local coordination, and not fully handing over the management to local municipalities. On the other hand, this appeared to strengthen the cooperation at the local level, between municipalities in Finland [Citation5].

Keeping in mind the situations of each Arctic country during the first year of the pandemic, restrictions varied. Still, generally, the restrictions were given to control travelling and physical distance in social interaction, e.g. closures, but also to ensure testing and isolation when necessary. Indigenous Peoples in the Arctic were generally permitted to special exceptions due to the traditional lifeways, including Finland [Citation26]. Overall, research evidence summarises that the pandemic time between September 2020 and January 2021 was challenging in the Arctic, especially in Alaska, Arctic Russia, and Northern Sweden due to increased confirmed cases and deaths. During this second wave of the pandemic, peaks in confirmed cases can be seen in the other areas of Arctic as well, e.g. Northern Canada, Finland, Norway, and Iceland, Faroe Islands and Greenland, but the increase was not that dramatic [Citation27,Citation28]. Compared to other Arctic countries, Finland recorded less COVID-19 cases 26]. However, the pandemic time with the Omicron variant at the end of the year 2021 increased the number of cases in these countries as well, except in Sweden, where it was not that obvious compared to earlier phases. Number of deaths, caused by COVID-19 in Finland, has been counted using different system compared to other Arctic countries, and therefore it is not comparative [Citation28]. Confirmed COVID-19 cases of the municipalities of the study at the end of the year 2021, number of cases started to raise in Inari municipality, resulting to the most challenging situation in late February and mid-March 2022 in both municipalities [Citation9], which is common time for winter holiday breaks in Finland.

Conclusions

People complied well with COVID-19 public health actions, which could have been due to the good pandemic situation in Northernmost Finland. Operators and municipalities were able to provide the needed actions and communication was overall coherent. Still, in future situations, communication should be even clearer and more precise. It should be done in all three Sámi languages and be available to all age groups and communities, using different sources of information. Local co-operation between professionals and operators is essential during a pandemic, and the local situation should be considered, especially concerning restrictions on borders. In the future, coordination between countries should be improved. In the control of a pandemic, the resources of municipalities with borders and a high number of tourists should be supported. These results highlight the importance of local operations and decision-making that consider of all the residents, including Indigenous Peoples and their needs. Trustworthiness towards authoritative is important and may support the official public health communication and compliance towards guidelines. These perspectives may be useful and could be utilised in the other Circumpolar areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all the participants for their time and valuable information, and researcher Kati Parkkinen, PhD, for her valuable work during the research project. The authors want to thank all the participants for their time and valuable information.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Tiirinki H, Tynkkynen LK, Sovala M, et al. COVID-19 pandemic in Finland – preliminary analysis on health system response and economic consequences. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(4):649–8.

- Häyry M. The COVID-19 pandemic: a month of bioethics in Finland. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2021;30(1):114–122. doi: 10.1017/S0963180120000432

- Regional state Administrative Agency. About Corona. [cited 2023 Apr 14]. Available from: https://avi.fi/en/about-corona

- Stenvall J, Leskelä R-L, Rannisto P-H, et al. Koronajohtaminen Suomessa. Arvio covid-19-pandemian johtamisesta ja hallinnosta syksystä 2020 syksyyn 2021. Valtioneuvoston selvitys- ja tutkimustoimikunnan julkaisusarja. 2023 May 16;2022: 34. tietokayttoon.fi. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/163995

- Kihlström L, Siemes L, Huhtakangas M, et al. Power and politics in a pandemic: insights from Finnish health system leaders during COVID-19. Soc Sci Med. 2023;321:115783. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115783

- Koljonen J, Palonen E. Performing COVID-19 control in Finland: interpretative topic modelling and discourse theoretical reading of the government communication and hashtag landscape. Front Polit Sci. 2021;3:3. doi: 10.3389/fpos.2021.689614

- Heinikoski S, Hyttinen T. The impact of covid-19 on the free movement regime in the north. Nord J Int Law. 2022;91(1):80–100. doi: 10.1163/15718107-91010004

- Inari municipality. Statistics. [cited 2023 May 15]. Available from: https://www.inari.fi/en/information/statistics.html

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. COVID-19 Cases In The Infectious Diseases Registry. [cited 2023 Apr 14]. Available from: https://sampo.thl.fi/pivot/prod/en/epirapo/covid19case/summary_tshcdweekly

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Lindgren BM, Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108:103632. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

- Georgieva I, Lantta T, Lickiewicz J, et al. Perceived effectiveness, restrictiveness, and compliance with containment measures against the Covid-19 pandemic: an international comparative study in 11 countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(7):3806. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18073806

- Hyland-Wood B, Gardner J, Leask J, et al. Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):30.

- Soveri A, Karlsson L, Antfolk J, et al. Unwillingness to engage in behaviors that protect against COVID-19: the role of conspiracy beliefs, trust, and endorsement of complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):684.

- Earnshaw VA, Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, et al. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(4):850–856. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa090

- Sedgwick D, Hawdon J, Räsänen P, et al. The role of collaboration in complying with COVID-19 health protective behaviors: a cross-national study. Administration & Society. 2022;54(1):29–56. doi: 10.1177/00953997211012418

- Benham JL, Lang R, Kovacs Burns K, et al. Attitudes, current behaviours and barriers to public health measures that reduce COVID-19 transmission: a qualitative study to inform public health messaging. PloS One. 2021 19;16(2):e0246941. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246941

- Anwar A, Malik M, Raees V, et al. Role of mass media and public health communications in the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2020 14;12(9):e10453. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10453

- Fissi S, Gori E, Romolini A. Social media government communication and stakeholder engagement in the era of covid-19: evidence from Italy. Intern Jour Publ Sec Manage. 2022;35(3):276–293. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-06-2021-0145

- Shang Y, Liou R-S, Rao-Nicholson R. What to say and how to say it? Corporate strategic communication through social media during the pandemic. Int J Commun. 2022;16(4):633–648. doi: 10.1080/1553118X.2022.2033980

- Solnick RE, Chao G, Ross RD, et al. Emergency physicians and personal narratives improve the perceived effectiveness of COVID-19 public health recommendations on social media: a randomized experiment. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(2):172–183.

- Bridgman A, Merkley E, Loewen PJ, et al. The causes and consequences of COVID-19 misperceptions: understanding the role of news and social media. HKS Misinfo Review. 2020. doi:10.37016/mr-2020-028

- Mheidly N, Fares J. Leveraging media and health communication strategies to overcome the COVID-19 infodemic. J Public Health Policy. 2020;41(4):410–420. doi: 10.1057/s41271-020-00247-w

- Finlex. [cited 2023 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.finlex.fi/en/

- Finnish Ministry of the Interior. Decision. [cited 2023 Apr 21]. Available from: https://intermin.fi/ajankohtaista/paatos?decisionId=0900908f80706da0

- Peterson M, Akearok GH, Cueva K, et al. Public health restrictions, directives, and measures in Arctic countries in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. International J Circump Health. 2023;82(1):2271211. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2023.2271211

- Petrov AN, Welford M, Golosov N, et al. The “second wave” of the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: regional and temporal dynamics. International J Circump Health. 2021;80(1):1925446. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2021.1925446

- Tiwari S, Petrov AN, Devlin M, et al. The second year of pandemic in the Arctic: examining spatiotemporal dynamics of the COVID-19 “delta wave” in Arctic regions in 2021. International J Circump Health. 2022;81(1):2109562. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2022.2109562