ABSTRACT

This manuscript presents a qualitative exploration of the experiences of people in two Southwestern Alaska communities during the emergence of COVID-19 and subsequent pandemic response. The project used principles of community based participatory research and honoured Indigenous ways of knowing throughout the study design, data collection, analysis, and dissemination. Data was collected in 2022 through group and individual conversations with community members, exploring impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants included Elders, community health workers, Tribal council members, government employees, school personnel, and emergency response personnel. Notes and written responses were coded using thematic qualitative analysis. The most frequently identified themes were 1) feeling disconnected from family, friends, and other relationships, 2) death, 3) the Tribal councils did a good job, and 4) loss of celebrations and ceremonies. While the findings highlighted grief and a loss of social cohesion due to the pandemic, they also included indicators of resilience and thriving, such as appropriate and responsive local governance, revitalisation of traditional medicines, and coming together as a community to survive. This case study was conducted as part of an international collaboration to identify community-driven, evidence-based recommendations to inform pan-Arctic collaboration and decision making in public health during global emergencies.

Introduction

The COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic had profound impacts in the United States (US), as well as within Alaska Native communities, where the pandemic exposed strengths and vulnerabilities within community response and local health and services infrastructure [Citation1]. More than 60,000 people in Alaska, including about half of the state’s Alaska Native population, live in remote communities that are not connected to major population centres via road, and are only accessible via plane, snow machine, or boat [Citation2,Citation3]. Numerous geographic and social factors placed Alaska Native residents of remote communities at an increased risk of negative consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, including reduced access to basic supplies and store-bought food, overcrowded housing, inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure, and limited healthcare access [Citation4–7]. Community-wide shutdowns and school closures affected social connections, disrupting childcare, cultural activities and ceremonies, and increasing social isolation [Citation8]. Moreover, the lasting impacts of structural racism and historical trauma contribute to inequities that exacerbated COVID-19 risk for American Indian and Alaska Native peoples [Citation1,Citation9]. Consistent with racial and ethnic disparities across the US, Alaska Native people experienced disproportionately high incidence of COVID-19 relative to White people living in Alaska [Citation1]. From March 2020 through December 2021, COVID-19 incidence for Alaska Native people in Alaska was 26,583 per 100,000 standard population, more than twice the rate among White people living in Alaska (11,935) [Citation1].

Despite considerable vulnerabilities, many Alaska Native communities responded proactively to the novel stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation10]. People living in remote communities reported prioritising the knowledge, and protection, of Elders, which affected individual safety decisions related to mask use and vaccination [Citation10,Citation11]. Surveys collected from Alaska Native people living in remote communities during the early months of the pandemic showed that although traditional hunting camps were cancelled to limit social contact, overall access to traditionally harvested foods was minimally disrupted [Citation2,Citation6]. People reported participation in subsistence activities like hunting, fishing, and berry picking, which are associated with health, healing, and stress coping in Alaska Native communities [Citation12,Citation13]. Alaska Native community members also found strategies to continue providing harvested foods to Elders despite contact restrictions [Citation6].

Existing health disparities among remote Alaska Native communities prompted many local leaders to take swift action to implement protective measures and policies to mitigate COVID-19 transmission [Citation14]. Regionally coordinated pandemic responses were affected by politicisation of COVID-19 protection strategies, and by limited federal and state guidance on transmission mitigation strategies such as mask use, and travel [Citation11,Citation15]. Despite few state-level restrictions, many Alaska Native communities implemented mask requirements and restricted entry to limit COVID-19 transmission [Citation2,Citation14]. In a study of pandemic adaptations among Alaska Native communities in Southeast Alaska, more interviewees reported feeling united, rather than divided, in their public health response to COVID-19 [Citation10]. Although communities demonstrated resilience in their response to COVID-19, lockdowns, and supply and service disruptions, the pandemic was responsible for disproportionate morbidity and mortality in Alaska Native communities. As such, there emerged a critical need to explore the positive and negative ways that locally implemented COVID-19 policies impacted the everyday lives of Alaska Native people who lived in remote communities during the pandemic.

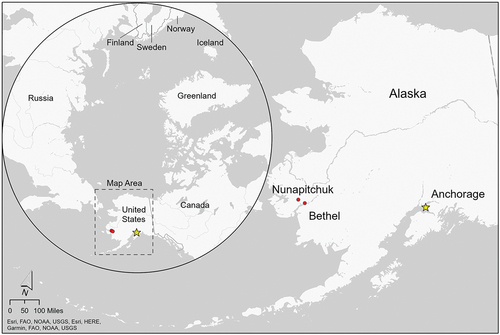

This qualitative study explored community perspectives on the COVID-19 pandemic in two rural Alaska communities. We also investigated what types of COVID-19 policies and restrictions were locally implemented and how they affected the daily lives of residents. This study was part of a circumpolar collaboration to examine perspectives on COVID-19 from Indigenous and rural communities across seven Arctic countries (the United States, Canada, Greenland, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland) [Citation16]. The research collaborative was initiated by a team of Arctic Fulbright Initiative Alumni and implemented under the auspices of the former Sustainable Development Working Group of the Arctic Council. The research team for the Alaska portion of this project, like many of the international teams, included Indigenous researchers and used culturally congruent methods. Our study aimed to co-produce knowledge, honour Indigenous ways of knowing, and uplift the voices of Alaska Native community members who graciously shared their COVID-19 experiences.

Methods

Study area

This case study explored the experience of rural Alaska community members during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants were from the Southwestern Alaska communities of Nunapitchuk and Bethel (). Nunapitchuk had an estimated population of 594 residents in 2020 and was governed by both a Tribal council and a city government [Citation17,Citation18]. Bethel is the regional hub and had an estimated population of 6,327 residents in 2020, with governance by both a Tribal council (Orutsararmiut Native Council) and the City of Bethel [Citation19–21]. Nunapitchuk and Bethel are located in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, where the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers empty into the Bering Sea. There are virtually no roads in the region, and communities are accessible by boat or small aircraft in the summer months, and by snow machine or by driving on frozen rivers in the winter. Bethel is the regional hub, and is the location of the largest airport, hospital, and other major infrastructure in the region. Health and medical care in Nunapitchuk and Bethel is serviced by the regional Yukon-Kuskokwim Health Corporation headquartered in Bethel, and Nunapitchuk has a clinic in the village staffed by Community Health Aides/Practitioners; rural Alaska’s lay medical providers [Citation22].

Community based participatory research

Our study was rooted in the principles of community based participatory research (CBPR) to include the needs and interests of local community members, improve equity between researchers and participants, and to honour Indigenous ways of knowing throughout all stages of research [Citation23]. The members of our research team have diverse backgrounds, including Alaska Native, Chicana, Cuban-American, and White researchers. Three of our research team members were born and raised in Alaska and contributed valuable place-based knowledge and cultural understanding to strengthen the foundation and relevance of the research. The leadership for this project included an Indigenous researcher from Nunapitchuk who lived in Bethel, and who was an essential leader in community partnerships and co-creating knowledge. Bethel and Nunapitchuk were selected as study areas based on the existing relationships between our community-based research team member and the communities, and a history of established trust and mutually gratifying research collaborations. Through a CBPR framework, our research team built upon existing community strengths and incorporated local knowledge, resources, and social networks into the study design to generate salient findings that are meaningful and relevant for people in the communities of Nunapitchuk and Bethel. The team maintained regular communication with Tribal governance including with the Native Village of Nunapitchuk Council and the Orutsararmiut Native Council to discuss study design, research questions, and preliminary findings. CBPR as a framework for conducting research in Indigenous communities allows for trust building and reciprocity and enriches data interpretation by uniting the expertise of community members and academic teams [Citation24].

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study was provided by the Alaska Area Institutional Review Board (IRB Reference Number 2021-09-050-2), with the University of Alaska Anchorage Institutional Review Board also reviewing and approving, and then ceding review to the Alaska Area IRB. Additional approval was granted by the Nunapitchuk Native IRA Council, Orutsararmiut Native Council and the Yukon Kuskokwim Health Corporation’s (YKHC) Executive Board of Directors. In accordance with their protocols, this manuscript was submit for review and approval by the YKHC Executive Board of Directors, while the Native Village of Nunapitchuk Council and Orutsararmiut Native Council were provided updates when this paper was under review and copies of published documents.

Recruitment and participants

Participants in our study included people in Nunapitchuk and Bethel who were living in the region during the COVID-19 pandemic. Consistent with the principles of CBPR and Indigenous methodologies, research participants were recruited through long-standing relationships with project leadership [Citation25]. In addition to general community members, healthcare workers, city personnel, Tribal council members, emergency response personnel, school staff, and Elders were purposively recruited. Participants signed a written consent prior to participation and were each offered a $50.00 gift card and light refreshments in the spirit of reciprocity, consistent with Indigenous research methodologies and local customs [Citation25].

Data collection

Four members of the research team connected with community members in Bethel and Nunapitchuk in March of 2022. Focus groups were planned with residents from each community. Interviews were opportunistically conducted with individual community members in circumstances where focus group attendance was staggered. In addition to interviews and focus groups, several Elders from a local senior group submitted signed consents and written responses to each question. In Nunapitchuk, focus groups were held in a public gathering space and in the workplaces of individual community members based on their availability. In Bethel, focus groups were held in a community gathering space, at the Tribal council office, and at the local college campus. Interviews were primarily conducted in English, and a project team member provided Yup’ik cultural and linguistic translation when needed.

The focus group/interview question guide was developed collaboratively by the research team, with input from the international circumpolar collaboration this project is a part of, and revised from Nunapitchuk and Bethel Tribal council input. An introduction and consent form was read aloud before all conversations, and signed consent forms were collected from all participants prior to data collection. There were 12 questions asked of all participants about the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants involved in governance and healthcare were asked additional specific questions related to local COVID-19 healthcare policies and incident command structure.

Notes were taken by one of the research team members during each focus group on a large flip-chart so participants could see. During interviews, notes were taken directly on the interview guides. At the end of each focus group/interview, notes were read aloud to the participants to confirm the interpretation and clarify or edit any content. The meetings were not otherwise recorded. All members of the research team adhered to state and community-specified COVID-19 protocols, including testing for COVID-19 before and after travel, using a mask in all spaces, providing proof of vaccination, and hygiene practices.

Analysis

All focus group and interview notes, as well as the written Elder responses, were input into Microsoft Excel. Two research team members independently coded all notes, with regular meetings to first develop and refine the codebook, then come to consensus on codes. The most frequently occurring codes were identified for each question, and for the overall dataset. These findings were discussed with the project team to confirm Indigenous and community meaning and context. Verbatim comments typifying each theme were selected to communicate findings in a linguistically relevant manner, and to represent the voices of study participants as closely as possible.

Dissemination

The results of the study were organised by theme and presented to the Orutsararmiut Native Council in Bethel, and to the Native Village of Nunapitchuk. A one-page flyer with findings specific to Nunapitchuk and Bethel, respectively, was distributed to each Tribal council to share in their community. Additionally, a one-page flyer with comprehensive results was produced for distribution during presentations and other relevant meetings.

Trustworthiness

Using a CBPR framework, the established relationships between our community-based research team member and other community members enhanced the trustworthiness of the findings. To improve the rigour of our analysis, themes were discussed by multiple research team members to incorporate Indigenous epistemology, rich local standpoint, and to avoid interpretation from a single research perspective [Citation26,Citation27]. Direct quotes are included in our results to provide participant descriptions in support of emergent themes. Consistent with the principles of CBPR, we disseminated the findings of this study directly back to Tribal leaders in both communities to empower participants to see, understand, and own their data [Citation23]. In the production of this article, the members of our research team who are Alaska Native directed important and nuanced linguistic choices that adhere to Alaska Native values of communication, and truthfully represent lived realities for Alaska Native people.

Results

A total of 48 individuals participated in the study, including in 19 focus groups/interviews.

Demographics

Demographics are summarised in :

Table 1. Study participant demographics.

Participants ranged in age from 22 to 80 years old, and included 27 female participants (17 in Nunapitchuk and 10 in Bethel), and 21 male participants (8 in Nunapitchuk and 13 in Bethel). Nineteen groups/individuals participated in the study, including 11 groups in Nunapitchuk and 8 groups in Bethel. Participants included Elders, health professionals, Tribal/city leadership, and teachers/school staff. The results shared in this manuscript include both the most frequently occurring codes overall and by question. To allow the voices of participants to speak for themselves, we have included participant quotes for the most frequently occurring codes.

Common themes

The most frequently occurring code was “feeling disconnected from family, friends, and other relationships”, with 16 comments identified throughout the data. As a participant shared: “We have very close families. Had to choose between family and COVID”. The second most frequently occurring code was death, occurring nine times throughout the data. As participants shared: “People die every day. We’ve lost our Elders”. “Lot of deaths, don’t know who’s being buried. Used to be we would go support family. We don’t do that anymore”. The loss of celebrations and ceremonies referenced in the previous participant quote was the fourth most common code, and included several references to a loss of ceremony around death (7 comments). As a participant shared:

When a family member is very sick the immediate family is affected by not being able to be with the sick when they are in the hospital and dying. We could not have a proper funeral due to the pandemic. Families not able to get together for funerals, parties, and other gatherings.

The third most frequently occurring code was that the Tribal councils had “done good” in assisting with the pandemic (8 comments). As a respondent shared:

“ONC has been so supportive, above and beyond. Cleaning supplies, dropping off food. We wouldn’t have been able to survive without ONC. Beyond grateful, don’t want to ask for anything else. Tunriq” [Tunrirtua – I am beholden…]

The Yup’ik emotion, “tunriq” was translated by a member of the project team as to be so grateful/indebted that you can’t criticise. This emotion is holistically and deeply rooted in Yup’ik Values of Spirituality and Humility; this study participant felt beholden by the Tribal council providing essentials to support coping with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fifth and sixth most common codes each had six occurrences in the data. “Working together” and “social distancing” as the most helpful way to keep you and your community safe. Respondents shared that working together included:

People are more caring for each other, rely on each other. In my village, we had water and needed kindness to help people get basic needs, like back in the day. People help people. Working together.

Our region has lots of medicine. People are going back to it. Even white people. I got COVID, no one’s going to help us, so that’s what we did. Lot of people helping, volunteering, sewing masks out of cloth from hospital. Organizing to get supplies to villages. Food bank. We took COVID more seriously because we have that history of pandemics wiping out our people.

Responses by question

summarises responses by question:

Table 2. Most frequent responses by question.

Discussion

This community engaged study revealed not only the hardships and loss experienced by study participants, but also the resilience, ingenuity, and the revitalisation of traditional ways of being during the pandemic. Small, rural Indigenous communities in Alaska, and throughout the United States, suffered a disproportionate burden of death and morbidity due to the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation1]. The high rates of loss are even more keenly felt not just because each person in a small community is often a friend or family member, but also because the death of an Indigenous Elder means their traditional knowledge dies with them. With Indigenous languages and ways of knowing under threat, these losses impact the passing of vital cultural knowledge from one generation to another. The threat of loss of Elders and of traditional knowledge has been identified as a COVID-19 concern among other rural Alaska Native communities in the state, and as a motivator to adopt COVID-19 health protections [Citation10,Citation11,Citation28]. In response to acute crises like COVID-19, and to persistent challenges affecting rural Alaska Native communities, like climate change, the transmission of traditional knowledge is an invaluable component of thriving in a changing world [Citation28].

The themes that emerged from the focus groups have root reflections of historical, and continually evolving, Yup’ik cultural practices. Although contemporary social systems tend to contradict Yupiit People practicing their own medicine and senses of community, the Yup’ik study participants articulated that they continued to hold the spirit of working together in high regard, and the COVID-19 pandemic revitalised that familiar spirit of helping each other out and sharing each other’s medicinal knowledge. While a part of everyday life, the traditional strategies of caring, coping, and medicinal practices became poignantly important during the pandemic.

The sense of disconnection from family and friends, as well as loss of celebrations and ceremonies were common themes that speak to the social and cultural disruption caused by the pandemic and policies to mitigate its’ spread. Further research would be needed to understand how communities have recovered from the height of the pandemic, and what, if any, changes have persisted due to the pandemic and related policies, whether positive (such as continued revitalisation of traditional medicines and sharing) or negative (such as continued feelings of disconnection and loss of ceremonies).

Study findings also spoke of people helping each other out of necessity and kindness, with Tribal councils ensuring that community members had traditional foods to eat and cleaning supplies to help keep themselves safer. People in Nunapitchuk found ways to continue supporting spiritual wellness and coping despite contact limitations, including by streaming church services through local radios in the village. The loss of friends and family members, as well as historical knowledge of the 1918–1919 Spanish flu and other outbreaks, also were mentioned as contributing to the high adherence to local policies like lockdowns, social distancing, and travel restrictions. Historic memory of prior outbreaks, including the 1918 Spanish flu, was identified as a motivator of vaccination acceptance and guidance for crisis response in other Alaska Native communities during the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation10,Citation11].

This study relied on the leadership and guidance of a community-based research team member deeply connected to the participating communities. The principles of co-production of knowledge and focus on Indigenous leadership allowed the study to happen. The strong relationships and wisdom of the community-based researcher facilitated the partnerships with Tribal decision-making bodies, the development of the research questions and methodology, and recruitment of study participants. The focus groups were some of the first in-person gatherings some of the study participants had been to, and many showed up because of their personal connection to the research team member. The existence of this study, and the rich results, are a testament to the essential role of Indigenous leadership and co-production of knowledge.

Most study participants approved of how the Tribal councils in Nunapitchuk and Bethel responded to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Tribal councils’ distribution of hygiene and cleaning products, masks, and assistance with utility payments were reported as extremely helpful for many households. Participants emphasised how valuable local quarantine workers were in helping to deliver groceries and supplies while entire households were isolating. The approval and gratitude participants expressed for these locally organised services reflect the power and acceptability of Tribal governance, and the key role they play in promoting community well-being.

Participants described innovative infection control and transmission mitigation strategies that reflected the realities of their health infrastructure and geography, such as collaborating with the local airline to establish a travel approval system for airline passengers:

Essential travel remained. With Tribal, we set up a system to ask Tribal admin before getting on Grant [airline]. Communication with the airport. Former administrator would call airlines to allow and approve travel. COVID funding allowed for a project coordinator. You had to be met at the airport with a paper and then we would print out a quarantine list and then cross-check it with a positive case. It was their version of contact tracing even though YKHC did actual contact tracing for just the traveler, not the whole household.

Furthermore, participants identified situations where there was a need for funding or equipment to support COVID-19 protections in their community that was unconventional relative to federal COVID-19 guidelines. For example, a participant on the COVID-19 task force expressed that they needed a new snow removal machine to clear access to the clinic for COVID-19 patients, but purchasing that type of equipment was not allowable under the Coronavirus Relief Fund guidelines of the CARES Act for Tribal communities [Citation29].

Collectively, these findings echo the call to policymakers at the state and federal level to engage Alaska Native communities quickly and empower their local leadership to execute emergency response protocols that match their resource landscape [Citation30–32]. In the absence of state and federal COVID-19 restrictions, Tribal leadership in Nunapitchuk and Bethel executed many strategies to protect community members and reduce transmission, including through curfews, travel restrictions, and mask requirements. Findings from this case study emphasise the power of sovereign Alaska Native communities, and support their autonomy to establish and enforce local protocols in times of crisis [Citation30,Citation32].

Limitations

The findings of this study are specific to the communities of Nunapitchuk and Bethel and cannot be generalised to all Alaska Native communities in the state. There were also only 48 participants, and their responses may not be generalisable to the entirety of their communities. However, our results are consistent with research emerging among Alaska Native communities of other geographic regions of Alaska [Citation8,Citation10,Citation11].

Conclusion

People living in the participating rural Alaska Native villages of Southwest Alaska demonstrated unity and creativity in their adaptive responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings of this qualitative study suggest that rural Alaska Native communities benefitted from strong Tribal leadership and a collective approach to protecting all community members and particularly Tribal Elders. Policies pertaining to emergency response protocols in Alaska Native communities may be strengthened by directly empowering and supporting local Tribal leadership to organise community protections. Participants shared their closing thoughts with us, that included:

What I want people to learn from this pandemic is how to rely on each other for support and help.

Tell next generation: Always be ready for the next COVID to come. And don’t listen to hearsay about the things. Some of them don’t tell the truth. And make sure the little ones get their shots.

A message for the future: Teach our children about Yup’ik medicine. Our parents and elders told us of TB [tuberculosis] and they told us what they did at that time. And we can pass our medicines to our little kids. Tell them daily.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ward LA, Black KP, Britton CL, et al. COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths among American Indian or Alaska Native Persons—Alaska, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(22):730. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7122a2

- Fried R, Hahn M, Cochan P, et al. COVID-19 in remote Alaska communities: a longitudinal view of a novel pandemic. Witness community highlights. Arctic Research Consortium of the U.S; 2021. https://www.arcus.org/witness-the-arctic/2022/3/highlight/1#:~:text=More%20than%2060%2C000%20people%20live,or%20snowmobile%20(Figure%201)

- Robinson D, Howell D, Sandberg E, et al. (2019). Alaska Population Overview: 2019 Estimates. https://live.laborstats.alaska.gov/pop/estimates/pub/19popover.pdf

- Eichelberger L, Dev S, Howe T, et al. Implications of inadequate water and sanitation infrastructure for community spread of COVID-19 in remote Alaskan communities. Sci Total Environ. 2021;776:145842. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145842

- Hathaway ED. American Indian and Alaska native people: social vulnerability and COVID‐19. J Rural Health. 2021;37(1):256–9. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12505

- Johnson N, Erickson K, Jäger M, et al. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on food access for Alaska natives in 2020. Arctic report card, 2021. https://arctic.noaa.gov/report-card/report-card-2021/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-food-access-for-alaska-natives-in-2020/

- Wong MS, Upchurch DM, Steers WN, et al. The role of community-level factors on disparities in COVID-19 infection Among American Indian/Alaska native veterans. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(5):1861–1872. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01123-3

- Fried RL, Hahn MB, Gillott L, et al. Coping strategies and household stress/violence in remote Alaska: a longitudinal view across the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2022;81(1). doi: 10.1080/22423982.2022.2149064

- Burki T. COVID-19 among American Indians and Alaska Natives. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21(3):325–326. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(21)00083-9

- van Doren TP, Zajdman D, Brown RA, et al. Risk perception, adaptation, and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Alaska Natives. Soc Sci Med. 2023;317:115609. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115609

- Eichelberger L, Hansen A, Cochran P, et al. COVID-19 vaccine decision-making in remote Alaska between November 2020 and November 2021. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2023;82(1). doi: 10.1080/22423982.2023.2242582

- Fried RL, Hahn MB, Cochran P, et al. ‘Remoteness was a blessing, but also a potential downfall’: traditional/subsistence and store-bought food access in remote Alaska during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Nutr. 2023;26(7):1317–1325. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980023000745

- Wolsko C, Lardon C, Mohatt GV, et al. Stress, coping, and well-being among the Yup`ik of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta: the role of enculturation and acculturation. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2007;66(1):51–61. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v66i1.18226

- Hopkins K (2020, March 22). Remote Alaska villages isolate themselves further in effort to shield against coronavirus. Anchorage Daily News. https://www.propublica.org/article/remote-alaska-villages-isolate-themselves-further-in-effort-to-shield-against-coronavirus

- Alaska Native Health Board (ANHB). (2020). Coronavirus public health response to Alaska fisheries in rural Alaska native communities. ANHB White Papers. https://www.anhb.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ANHB-White-Paper-Coronavirus-Public-Health-Response-to-Alaska-Fisheries-in-Rural-Alaska-Native-Communities-Final.pdf

- Peterson M, Healey Akearok G, Cueva K, et al. (2023). Public health restrictions, directives, and measures in Arctic countries in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic [In Review].

- Native Village of Nunapitchuk. Native village of Nunapitchuk. Yupik.org; 2023. http://yupik.org/

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Nunapitchuk City, Alaska. https://www.census.gov/search-results.html?q=Nunapitchuk&page=1&stateGeo=none&searchtype=web&cssp=SERP&_charset_=UTF-8.

- City of Bethel. City of Bethel, Alaska. City of Bethel; 2023. https://www.cityofbethel.org/

- Orutsaramiut Native Council (ONC). About ONC. Orutsaramiut Native Council; 2023. https://orutsararmiut.org/aboutonc/

- U.S. Census Bureau. Bethel City, Alaska; 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/bethelcityalaska,bethaltovillageillinois,bethelcensusareaalaska#

- Golnick C, Asay E, Provost E, et al. Innovative primary care delivery in rural Alaska: a review of patient encounters seen by community health aides. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71(1):18543. doi: https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18543

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, et al. Community-based participatory research for health: advancing social and health equity. Wiley; 2017. https://books.google.com/books?id=GLg4DwAAQBAJ

- Whitesell NR, Mousseau A, Parker M, et al. Promising practices for promoting health equity through rigorous intervention science with indigenous communities. Prev Sci. 2020;21(S1):5–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-018-0954-x

- Wilson S. Research is ceremony. Indigenous research methods. Winnipeg: Fernwood; 2008.

- Quinn AL. Bridging indigenous and Western methods in social science research. Int J Qual Methods. 2022;21. doi: 10.1177/16094069221080301

- Thornberg R, Charmaz K. Chapter 11: grounded theory and theoretical coding. In The sage handbook of qualitative data analysis. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2014. doi:10.4135/9781446282243

- Palomino E, Pardue J. Alutiiq fish skin traditions: connecting communities in the COVID-19 era. Heritage. 2021;4(4):4249–4263. doi: 10.3390/heritage4040234

- US Department of the Treasury. (14 December 2021). Coronavirus Relief Fund: Revision To Guidance When a Cost Is Considered Incurred, December 14, 2021. United States Government. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/CRF-Guidance_Revision-Regarding-Cost-Incurred.pdf

- Akearok GH, Lavoie JG, Larsen CVL, et al. 2023. Policy recommendations from the COVID-19 pandemic in the Arctic: a locally focused holistic systems approach. in review.

- Brodt E, Empey A. American Indians and Alaska Natives in the COVID-19 pandemic: the grave burden we stand to bear. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):394–397. doi: 10.1089/heq.2021.0011

- Foxworth R, Redvers N, Moreno MA, et al. Covid-19 vaccination in American Indians and Alaska Natives — lessons from effective community responses. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2403–2406. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2113296