ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged our lives during the years 2020–2022. Impacts could be seen in everyday life, both locally and nationally, through economic, mental and social elements. However, these effects varied depending on the life situation of individuals. This paper aims to gather information from the representatives and operators working in two Finnish municipalities, Inari and Utsjoki, to understand and learn about their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data (20 interviews) were collected between December 2021 and February 2022 and analysed following the principles of the qualitative content analysis. The results suggest that the effects of COVID-19 emerged through issues related to the national border between Finland and Norway, economic challenges, and the pressure that people experienced. However, despite challenges, people were supported by everyday life and a connection to nature, communality and close co-operation. Additionally, local needs were highlighted among participants. The results provide a deeper understanding about the public health impacts in these Northernmost municipalities and can therefore be utilised in future development work. They also provide relevant information on the experiences of Sámi people, and specific views related to Sámi people can be recognised.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged and impacted our lives, and the most intensive time was during the years 2020–2022. Around mid-March 2020, the WHO pronounced COVID-19 to be a pandemic [Citation1,Citation2]. After 6 months, it was found to be the cause of death for almost one million people worldwide [Citation1]. In Finland, COVID-19 started to spread during March 2020, even though the first case of infection was diagnosed from one tourist on the 29th of January [Citation2,Citation3] at a ski resort located in the municipality of Inari, Finland. Overall, during the pandemic, the spread of infection and number rates varied in Finland, depending on regions; most cases were identified in the Southern part [Citation3]. The COVID-19 pandemic started to spread in Finland late compared to other countries, which in turn, provided an opportunity to implement public health guidelines [Citation2].

Finland, together with many other countries, sets public health recommendations and restrictions, e.g. social distancing and testing. In cases of a positive infection, tracking, isolation, and treatment took place to control the spread of infection [Citation2,Citation4]. National regulations were set, which promoted remote working in organisations, businesses, and services, when possible, restaurants and public cultural and recreational services were closed, and public meetings were limited to up to 10 people [Citation3,Citation5]. Schools and educational organisations provided remote online studying for students over 9-years old [Citation5–7], and it was also advised to provide home care for small children instead of daycare [Citation5]. Most regulations were released during the summer 2020, but restrictions related to hygiene standards, social distancing, and isolation when needed, remained, including control of public gatherings. New waves of the pandemic and regional variations demanded resetting of regulations during the pandemic when necessary – especially in autumn 2020 and spring 2021 [Citation2,Citation5].

Starting from January 2021, COVID-19 vaccinations in Finland were provided to people [Citation8], which helped to control the pandemic and protect the health of people [Citation9]. The pandemic was an economic challenge, resulting in dramatic financial problems for some [Citation2], but it also burdened the capacity of the healthcare system and resources [Citation4]. Rantanen and colleagues [Citation10] found that these demands resulted in an experience of mental burden among healthcare workers, especially when workload was increased, there was a lack of time to recover from work, or protective COVID-19 instructions were insufficient. The new demands and changes were mentally challenging for working people [Citation11], but also for family caregivers at home [Citation12]. In both studies, challenges were found to cause, e.g. anxiety, loneliness and stress. According to Koskela and colleagues [Citation7], the pandemic caused extra worries and burden for parents due to remote studying. They were especially concerned about the use of online tools, control of everyday life and the overall learning and wellness of their children. Suddenly, parents found themselves in a situation where they had to deal with their own remote work, while taking care of their children and remote studying [Citation6]. The collaboration between educational organisations and families in supporting parents has been highlighted [Citation7].

At the beginning of the pandemic, Finland set travel bans, which included bans on international flights from high-risk areas [Citation4] and crossing the national borders between Nordic countries [Citation13]. As Northernmost Finland is the area for residents, including Sámi Indigenous Peoples, who are used to free movement between Nordic countries, this decision separated families and changed the everyday life of people living in these border municipalities [Citation13]. Tourism, reindeer herding, and fishing are the central livelihoods in the municipalities of Inari and Utsjoki, which have borders to Norway and Russia [Citation14,Citation15]. In fact, the municipality of Utsjoki is the only municipality in Finland that has a majority of Sámi residents [Citation15].

This study purposed to investigate the appearance and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in Northernmost Finland, keeping in mind the future recommendations related to the pandemic. The study aimed to gather information from the representatives and operators working in two municipalities, Inari and Utsjoki, to understand and learn about their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This qualitative study interviewed adult study participants, who were representatives and operators working in the public and private sectors around the two Northernmost municipalities in Finland, Inari and Utsjoki. Both municipalities are in the Sámi homeland and have borders with Norway and Russia. Representatives and operators were working in different fields that were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, e.g. health and social work, management, education, culture, economics, business, tourism, communication, community, and volunteer work. They were both Finnish and Sámi; however, identity was not defined for the study. The determinative factor was to gather a wide variation of different representatives and operators working in the municipalities. In the individual interviews, there were nine men and ten women, and one group interview consisted of seven men and six women.

Data collection

The data were collected by a selection of researchers based on the structure of the municipality, using organisation charts and recognising central operators working in these municipalities. This process was finalised during the study as the goal was to achieve a comprehensive representation of representatives and operators working in the area. Researchers contacted study participants, informed about the study, and arranged interviews. This process resulted in 20 interviews. That number of interviews was enough as saturation was fulfilled. Interviews took place during December 2021 – February 2022, with an average duration of around 45–60 min. Interviews were conducted by the two authors of this study, whose backgrounds are in health sciences. Interviews were held at locations preferred by the study participants, usually their work offices. All interviews were completed in Finnish.

Theme interviews followed the topics related to overall appearance, impacts and future recommendations. The specific topics, which were asked and discussed in the interviews, were as follows:

appearance of the COVID-19 pandemic?

negative/positive impacts

supportive elements during the pandemic

specific elements related to Sámi identity or culture

implications/recommendations for the future

Data analysis

Data were analysed by inductive content analysis, which is a relevant analysis method in health research [Citation16]. The analysis process searched for answers to questions:

In what ways has COVID-19 appeared/emerged in these municipalities?

What has been important/supportive in solving the challenges of COVID-19?

What kind of elements related to Sámi identity or culture needs to be considered?

What should be considered/recommended for the future?

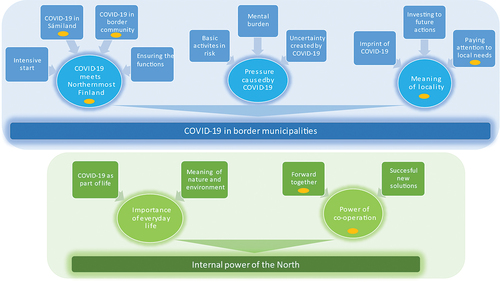

The analysis started by reading the data through several times, to get familiar with it. Next, the open coding process started by coding the data. This was followed by creating coding sheets, and moreover, codes with a similar content were grouped together. These sub-categories were formulated throughout the data. Furthermore, sub-categories were grouped into categories, and the process continued by grouping categories into generic categories. Finally, the abstraction process was closed by creating two main categories (). Codes that emerged from the data, which specifically answered the research question of Sámi identity and culture, were at first grouped into their own separate sub-categories. At the end of the analysis, they were merged to the whole data. The results integrate the responses of both Sámi and Finnish participants.

Ethics

For the participants, all were voluntary, and they had a right to terminate the study at any time. Consent forms were signed, and oral information about the study was provided by the researchers. All participants agreed to recorded interviews. The raw data has been securely handled; only the authors had access. Individual interviews were given a specific research ID that supported the anonymity of participants and were used, while the research assistant transcribed interviews. The risk assessment/data protection impact assessment was completed, and all participants were given the privacy notice for scientific research participants. This study did not fulfill the criteria for an ethical review in human sciences by the University of Oulu, which are based on national guidelines of Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK [Citation17] nor the criteria for medical research.

Results

The categories, generic categories and two main categories (COVID-19 in border municipalities and Internal power of the North) are presented in (see more detailed information in ). The results are presented by the following five generic categories. Quotes can be found from the .

Table 1. Categories and sub-categories, divided by the main categories.

Table 2. Quotes of the generic category COVID-19 meet northernmost Finland.

Table 3. Quotes of the generic category pressure caused by COVID-19.

Table 4. Quotes of the generic category meaning of the locality.

Table 5. Quotes of the generic category importance of everyday life.

Table 6. Quotes of the generic category power of co-operation.

COVID-19 in border municipalities

COVID-19 meets northernmost Finland

Based on the answers of the participants, the pandemic appeared to have an intensive start in Northern Lapland as the first diagnosed COVID-19 case in Finland was found from the municipality of Inari. National and international media were very interested in this case, and journalists travelled to Inari. During this time, the COVID-19 pandemic seemed chaotic and uncertain, and participants experienced that people felt confused and scared. They did not know how to act or what to do; there was uncertainty whether grocery stores would have enough food, so people stockpiled food and necessary items. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland became congested with new benefit applications due to the lack of incomes. People were afraid to meet elderly, and restrictions came into force. As a result, many locals went out into nature, which in turn, crowded popular forest areas. At the very beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were still tourists from Asia and Southern Europe in municipalities, which caused confusion for locals as it was recommended not to travel and still tourists were around. This new situation with COVID-19 appeared to be serious: projects and development plans had to be put on hold, public and community events and activities were cancelled, people did not travel for work, and student exchanges were cancelled. Based on the answers, local schools and student dormitories were closed, when necessary, but also public premises, such as restaurants and libraries, had to be closed. People did not meet each other in person as usual.

Participants felt that still, it was obvious that work and some activities had to be continued and carried out despite the COVID-19 pandemic – functions had to be ensured. That meant that the working mode and environment were modified by implementing new action models, such as completing minimal actions or with limited staff, and working online. They indicated that in-person or group meetings with customers or service users, e.g. health and social care and community work, were either on hold or had to be organised in a location without COVID-19 cases in order to carry on essential services. Furthermore, services were modified as well, for example medications and food were delivered to people, e.g. the elderly. Additionally, a free food service was started to help those in need, because people were lacking jobs and income. It was expressed that people met others, for example when picking up food, through windows or at the front of their homes. Student groups became smaller, and children’s summer camps were arranged as day camps. Moreover, traditional religious events had to be formulated in a new way, e.g. funerals and confirmation camps had to be postponed. This change to traditional funerals was distressing for some, as they were used to big funerals that were open to everyone; now due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this tradition seemed to be changing. Participants described that while in-person contact was reduced, telephone calls and messages and written letters returned to use when keeping in touch with customers, students, families, and elders. Also, newspapers were seen as an important element to pass on real-time information to locals, and their content was modified to include supportive and informative views during the pandemic. Online media related to COVID-19 was active, and news reached many locals. Overall, interviewees expressed that people wanted to receive information and had more time to read the news, so the media put an effort on that. Online working became real and familiar to all, with meetings, workshops and society clubs for children and youths, as well as different church services were held online.

The COVID-19 pandemic was clearly felt by the border communities, especially those living close to the border between Finland and Norway – which is usually open. Participants indicated that people were not able to go to work, shop, attend hobbies, pick berries, or do normal, everyday activities. Border restrictions and closed borders caused extra problems, burden, and work for many officials, but also for all who lived in these border communities. The impacts on collaboration with Russia were noticed as well, but not as strongly as the border is normally controlled. Based on the interviews, the COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges to the Sámi by creating a real boundary between Finland and Norway, which heavily impacted their lives, and limited Indigenous rights. It limited and even stopped the normal interactions between families, people, and villages, but also had a negative impact on traditional culture. The Sámi people felt isolated and excluded, which created a heavy mental burden. Interviewees expressed concern that control over the closed national border was at times exaggerated, and interpretation of the rules was tight, but also extensive at times. The border guards defined family relationships differently compared to Sámi definitions, and there were experiences of misunderstanding when trying to cross the border due to the reasons of traditional lifeways – which was an acceptable reason. They pointed out that only reindeer herders were allowed to go to Norway when retrieving their reindeer.

Study participants described that overall, the Sámi people felt unable to live a normal life, and no one supported them during the COVID-19 pandemic when they were not able to travel to Norway to meet their families. However, during this time, people were able to travel, e.g. from Southern Finland to the North to their villages. It felt unfair, especially when rates of cases were low in areas close to the national borders, but rates were high in the south of Finland. Participants indicated that traditional lifeways in Sámi culture, including reindeer herding and handicrafts, were impacted by the pandemic as well. Due to the closing of restaurants and decrease in the tourism business, the sale of reindeer meat decreased dramatically. This caused serious economic problems for reindeer herders and their families; for many it was the only source of income. Also, it was pointed out that border restrictions did not only have a negative impact on regular reindeer herding; it was also a problem that people were not able to buy equipment for handicrafts from Norway. At the same time as the COVID-19 pandemic, the Sámi people had to deal with extremely challenging winters, which caused the starvation and deaths of reindeer. Additionally, interviewees described that traditional salmon fishing became forbidden in the Teno river due to fishing regulations. All these changes, together with the pandemic, put people’s mental well-being and economic balance at risk. It was felt by the study participants felt that these were experienced even more strongly by Sámi people.

Some participants assessed that the impacts of COVID-19 were stronger for Sámi people, especially on their community and culture, compared to Finnish people. For some participants, there were no specific elements or issues related to Sámi Indigenous people or culture that had to be considered during the pandemic, as it was normal and part of everyday life in these municipalities. Overall, Sámi Indigenous peoples and culture were seen among participants as important, essential, and valuable. Moreover, communication with three Sámi languages had to be remembered and respected in municipalities. Sámi culture and families were seen as one Sámi land that has no national borders. Families live in Finland and in Norway, which is normal, and the border is not a real border for the Sámi. Sámi culture and language appeared strong in this area, and everyday communication, collaboration, and traditional lifeways were a part of everyday life.

Pressure caused by COVID-19

Basic activities were at risk, which were especially noticed in the tourism business and public services, and these presented economic challenges. Study participants indicated that due to the pandemic, tourism was totally stopped, especially at the beginning of the pandemic. International flights were cancelled, and national travel was limited, too. The all-year-round tourism business was in crisis with no tourists, which had been an essential part of the economy of these municipalities. However, based on the interview responses, national tourism became busy especially in summer 2021, which was important for local companies and restaurants to fill the gap. Slowly, the tourism business started to revive, but it has remained vulnerable throughout the pandemic, and seasons varied a lot. Interviewees described that economic and livelihood impacts for municipalities and people were dramatic, not only in tourism but also in restaurant and commerce businesses, especially those close to national borders due to the lack of Norwegian customers. Many people faced layoffs, they did not have income, and suddenly they had to also feed their children during the daytime as schools were closed at the beginning of the pandemic. It was also indicated that media, e.g. newspapers, were economically impacted as well due to a lack of bought advertisements – suddenly, there were no events or such to advertise. Moreover, public services were at risk due to a pause in the co-operation with Norway in social and health care services. In addition, participants expressed concern that collaboration between libraries, schools, and child day care for border communities were on hold. These had impacts on services for Sámi as well, including mental health services and specific health care, e.g. giving birth in a Norwegian hospital (the closest hospital) was not possible. Additionally, based on the interviews, there were experiences that home caregivers had to cope at home without specific services.

All these challenges related to COVID-19 caused mental burden for people. It was indicated that for some, changes in working life, such as remote work and online working, appeared to increase their workload. New systems and techniques demanded time, and people missed each other and in-person meetings. Overall, COVID-19 caused anxiety and fear. For some participants, it was challenging to keep updated and look for information about the pandemic situation. On the other hand, some experienced that being supportive to others was difficult or exhausting. They experienced that the pandemic felt endless, and being at home together with the whole family, cooking food, and remote working at the same time was demanding. The feeling of freedom was gone, and effectiveness at work was at risk. It was experienced that the whole community was mentally impacted, with different variations for children, youth, adults, and elders. These challenges were recognised in municipalities. For children, remote school caused extra challenges, and families did not necessarily have computers or other equipment. Alcohol use and domestic violence were recognised as possible problems, too. Participants described that a few weeks after the pandemic started, schools started to provide regular school lunches for children, which helped parents at home. However, they recognised that living alone and being isolated was demanding, especially for elders. People missed their family members and being together. Feelings of loneliness were strong. Regular family occasions, events, and celebrations were cancelled. Moreover, they expressed that it was difficult for people who had to travel long distances without their own car, for example, for vaccinations. On the other hand, as some of the interviewees described, the closed national borders during the COVID-19 pandemic brought up old, tragic memories, such as previous pandemics, e.g. Spanish influenza or World War II. For some, COVID-19 reminded them of life during the residential schools of Indigenous peoples.

Participants recognised that the COVID-19 pandemic caused uncertainty for locals. People were unsure whether they could safely travel in Finland or abroad, despite the lack of restrictions to control that. This uncertainty was noticed in the tourism business and economically – the future seemed unsure and unbalanced. No one knew what would happen with the pandemic. They indicated it had resulted in the situation where it was difficult to plan anything, such as meeting people or conducting any events. Possible new restrictions were in interviewees’ minds, and they did not know whether all will be closed again. The COVID-19 pandemic appeared to be unpredictable and living with changes was challenging, especially in the tourism business, which excitedly waited for tourists to fully return. Even though there were good signs that tourism would recover, it felt too unsure to really believe it. Additionally, in the interviews it came out that the pandemic situations varied quickly and regionally. Therefore, people wished for a normal life and hoped that vaccinations would help in the control of the pandemic.

Meaning of locality

Study participants felt that they had learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, and a certain imprint of COVID-19 was left. This experience and knowledge were important to recognise and utilise in the future in similar situations. Participants acknowledged that health promotion is important, decisions need to be made quickly, and crisis planning needs to be updated. They recognised how vulnerable health can be. The pandemic both educated and increased the awareness of locals. Additionally, online connections and working were believed to remain in the future, which participants also saw as an important way to reduce economic costs, e.g. travel costs. However, good interactions and supportive teamwork were highlighted when working remotely.

When considering the future, interviewees pointed out that investing towards future actions were essential, for example investing in concrete preparedness and appropriate resources. Participants wished for specific action models for similar situations and highlighted the productive and fluent collaborations that aim to support and help individuals. Some felt that preparedness during the pandemic could have been better. Moreover, there was a lack of resources, both economic and human, which require investment, especially in the field of social and health care. Still, the uncertainty of the future was recognised by study participants, which can be shown globally through new viruses or inequality between people, e.g. access to vaccinations. For some, there is mistrust of officials or decision-makers. On the other hand, it is still unsure whether people really learned from this experience. Participants indicated that it is important to maintain appropriate functions in the future. Especially tourism was seen as essential for these municipalities, and it should be a target for investment. Economically, tourism is important, but so is business in general. A sense of community was important for participants as well.

Local needs and paying attention to them were highlighted in the interviews by participants. This was especially important when considering and setting guidelines or restrictions to control the pandemic – the Northernmost situation and way of life should be recognised. Participants indicated that their knowledge and expertise are locally in the municipalities. Border restrictions should consider local needs and perceived double impacts, e.g. the restrictions for salmon fishing, should be avoided. Additionally, it was recognised that health is holistic, including not only physical health but also mental and social health. This needs to be considered when setting restrictions in future pandemics. For the future, closer collaboration should take place, for example with the Sámi Parliament, and reindeer herders should be more effectively included in decision-making. It was emphasised that Sámi should be seen as one who have their Indigenous rights, identity, and traditional culture, and this perspective should be included into future action models in similar situations. On the other hand, online actions and remote working or studying during the pandemic allowed Sámi people to stay at home more, which in turn, supported everyday life and traditional lifeways in their homeland. All these would increase adaptation to changes and support traditional life. As described by participants, overall, effective, and reflective interaction and collaboration between Sámi and Finnish peoples need to be remembered.

Internal power of the north

Importance of everyday life

Overall, participants expressed a variety of supportive elements that helped them during the pandemic. In a way, COVID-19 became a part of their lives. They felt that after the intensive start and hassle, the situation calmed down a bit. The uncertainty was reduced, and the situation was brought under control, using the knowledge and means that they had at that time. It was felt that this pandemic will not go away, so we must just live with it. Participants felt that people managed, adapted, or learned to live this new way of life, and focused on their own health and protected themselves, and vaccinations were seen as an important solution that helped control the pandemic. On the other hand, participants experienced that they had managed the situation well; the pandemic had remained moderate in Northernmost Finland, the number of cases had been low, and therefore the impacts on lives had been lower compared to other parts in Finland. During the pandemic, people were able to live quite a normal life at times. Interviewees described that municipalities, organisations and working places were able to quickly react to changing pandemic situations, guidelines, and restrictions. This supported normal life, as well as working and school environments. Municipalities were seen as an effective operator. New ways of working helped, but it was also experienced that preparedness was important; for example, a variety of online activities were already available prior to the pandemic. Some organisations had good economic resources that helped them cope during the pandemic time. Participants expressed that they had a lot of space, environment, and nature to live in these municipalities compared to larger cities. People had their own houses and yards, there were fewer people, and they were able to go around in nature, which was an especially empowering and pacifying element for locals. Nature truly supported people to deal with the challenges that COVID-19 caused, and people met each other out in the nature.

The power of co-operation

Participants expressed issues that described people going forwards together. Co-operation between them, communities, and different organisations was highlighted. People worked together and helped each other more intensively than before. COVID-19 was a joint enemy, a problem that had to be dealt with together. They indicated that some working places arranged remote discussion events or meetings in nature, since support of colleagues was important. Social and health services and different organisations or associations shared joint goals and strengthened their local collaboration. Moreover, it was noticed that people tried to support and encourage each other to do different things together. Fundraisings were organised, grocery stores donated food, and community people donated clothes for those who needed them. Volunteers packed and transported these further. Media published supportive news. Interviewees felt that a sense of community was very essential and positive, and it helped people a lot. All were in the same boat. It was described that some Sámi families met each other on the bridge between Finland and Norway and had coffee together without crossing the official border. They expressed elements that supported Sámi identity and culture during the pandemic. One central element was seen through the media. For example, radio, newspapers, and television provided important information and discussion in Sámi language, at times in all three Sámi languages. Moreover, online concerts were provided, and real, actual concerts were held outside when possible. The Sámi parliament attended different official meetings related to COVID-19 and collaborated with Sámi parliaments from Sweden and Norway. Based on the answers, Sámi associations provided support for locals. Overall, all these actions were seen as important.

Participants expressed successful new solutions when handling the COVID-19 pandemic. They felt that online working, meetings, and studying were not only good and effective overall but it also brought people closer in a way. Locals had good skills for remote working; they were already used to it, and children talked and played with each other online. This was seen as an important way to connect with each other. They described that through online working, the world seemed to be closer now – not only for people living in Northernmost Finland, but it also brought these municipalities closer to people living in Southern Finland. Many felt that the pandemic taught other people to see this possibility, and they now received new invitations to meetings or collaboration networks, which did not happen before. It was seen that the pandemic strengthened the online skills of locals. Online working was not the only way to conduct work; participants also expressed other alternative ways to work during the pandemic. For example, online shops and home delivery were created, media put effort on online newspapers, e.g. completed interviews via telephone and took photos through windows. Libraries started to take orders via telephone too and deliver books to customers when libraries were closed. Interviewees pointed out that the tourism business put more effort on summer tourism, and some organisations renovated their premises as they now had time for this. For some employees, the pandemic offered the possibility to study new things, e.g. languages, or they organised their work in a new way, for example arranged groups and activities for customers outside. Overall, participants felt that people were creative.

Discussion

The pandemic created negative impacts on labour markets globally, causing uncertainty and resulting in higher unemployment rates [Citation18,Citation19]. In Finland, these effects hit especially new organisations and the service sector [Citation20], such as tourism, restaurants and catering businesses [Citation5,Citation21], and businesses providing public events and happenings [Citation21]. Comparable findings were found in the present study, as participants expressed experiences related to economic challenges and unemployment, especially among service-sector providers. The tourism business struggled greatly due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which had further negative impacts on accommodation providers, restaurant businesses, and moreover on Sámi reindeer herders due to the decline in reindeer meat sales. Similar effects on the Indigenous traditional economy were found by the Arctic Council [Citation22]. A study conducted in Norway found that the pandemic had a minimal impact on daily work itself among reindeer herders in Norway, including Sámi herders. Still, negative consequences were noticed, such as economic impacts and closed national borders that limited normal life, e.g. work, family visits, and access to grocery stores [Citation23]. Changing guidelines and restrictions on international travel negatively affected travellers’ attitudes during the pandemic, and concerns related to health became after [Citation24]. Similarly, national border restrictions affected local peoples’ lives in this study, causing uncertainty, frustration and limiting their regular everyday life. Challenges related to the national border were recognised well among participants, and economic impacts were dramatic on businesses close to the border of Norway.

Working life changed – not only the content or way of working but it also forced rearrangements in working places, e.g. services. For some, remote working was more of a natural shift, while for some this change appeared more concrete, requiring innovative solutions of how to conduct work. The pandemic was a challenge for part-time workers, women, and those who were not able to work remotely, especially in face-to-face services [Citation5]. Oksanen and colleagues [Citation25] have found that remote work seemed to be a softer change for those who had already used it as part of their work. However, overall, people working remotely experienced more anxiety, and the most challenging time was in the middle of the pandemic in Finland [Citation26] and employees who felt stress related to online environment, or had feelings of overwhelming or loneliness, experienced anxiety or concerns more. Specifically, being female or younger was connected to feelings of anxiety [Citation11,Citation26]. Perceived stress was found to be related to work ability, but also to a lack of ergonomics and support from the working organisation [Citation27]. Based on the results of our study, support and togetherness of colleagues were important for participants and helped while working from home.

Changes during the pandemic, e.g. in economy, work and school, challenged life at home. They also led to the emergence of mental impacts, such as feelings of loneliness or being overwhelmed. For many, the pandemic separated families and brought new economic difficulties due to lack of income and increased living costs. According to Xiong and colleagues [Citation28], younger age, being female or having a lower economic status or education were risk factors for mental symptoms during the pandemic. Similarly, females, younger parents, or parents with economic challenges or younger children seemed to have more challenges adapting to the situation during the first lockdown in Finland [Citation29]. Being at home together with family was found to be specifically demanding for mothers, especially during the first wave of the pandemic [Citation5]. The limited time and space had to be rearranged to complete remote studying and working, and often parents helped their children during the schoolday, adjusting their own working hours [Citation6]. Brooke and Jackson [Citation30] recognised that during similar situations as COVID-19, elderly people should be supported to maintain their social connections as well as possible, as we found in this study. Family caregivers of older adults experienced loneliness and worry about how COVID-19 may impact their health. Again, being female and having a higher experience of stress or low mood were related to feelings of loneliness and worry [Citation12]. Limited social interaction increased the feeling of loneliness [Citation12,Citation31], and lower physical health was connected to mental challenges during the pandemic [Citation12,Citation28]. These findings are in line with our present study. However, based on our results, we cannot make any conclusions related to gender. It has been found that compared to non-Sámi people, Sámi people were more concerned of getting infected by COVID-19, and this was more obvious among Sámi men. Moreover, even higher concern emerged among Sámi men and women towards others for getting sick, compared to non-Sámi participants. However, feelings of loneliness were less common among Sámi participants [Citation32].

For Indigenous Peoples, physical distancing put the natural interactions between extended families, traditional cultural happenings, and important activities, including spiritual and religious, at risk. Spending time with valuable elders, youth, connecting with the community, sharing food [Citation33] and practicing their own traditions [Citation34] are important for Indigenous Peoples. In Canada, COVID-19 resurfaced historical traumas related to colonialism – lockdown, being separate again, and given governmental guidelines [Citation33]. Similar experiences were found in our study, such as memories of the Spanish flu, but a more dramatic memory was related to the closed national border. This caused memories of World War II and residential schools to resurface. According to Heinikoski and Hyttinen [Citation13], closed borders have been a great challenge to Sámi people; they have lived throughout history in one Sámi Land, without national borders. This in particular may have had a critical effect on their traditional lifeways, e.g. reindeer herding and family interactions.

Often, Indigenous Peoples experience lower health and well-being compared to non-Indigenous, and COVID-19 challenged already vulnerable people [Citation34–36]. This finding did not appear in our study; however, access to health care services in Norway was affected due to the pandemic and closed national border. According to Nilsson and colleagues [Citation32], based on the study conducted in Sweden, there were some differences among Sámi and non-Sámi participants in seeking health care during the spring of 2021. Sámi men seemed to be less likely to avoid health care services compared to Swedish men, while Sámi women were a little more likely to avoid care compared to non-Sámi women. Despite the negative effect that the pandemic had on Sámi livelihoods and traditional practices, even out in nature, our results highlighted that nature and space around people were supportive elements for residents in these municipalities during the pandemic. Similarly, Sámi people in Sweden seemed to spend more time outside compared to Swedish participants [Citation32]. In the current literature, there is evidence supporting this finding; nature is indeed important for our health and well-being [Citation37,Citation38]. For Indigenous Peoples, being connected to nature is an essential part of everyday life and culture [Citation39,Citation40].

Among nature, communality and togetherness helped people to deal with the pandemic and, in a way, brought people together. They helped each other, for example by sharing food and clothes, but people also reorganised their work to provide help and services. As found earlier, being able to interact with people in similar situations is important [Citation41]. Social relationships – being together in the same situation – support well-being and dealing with the pandemic [Citation42]. This was also highlighted among Finnish students and university staff during remote studying, although in-person meetings were missed [Citation43]. Similar results were found in this study, but participants also felt that online connections allowed them to be more active and connected with others – the world was closer now. Technology and online work provide the freedom to plan work, which in turn, supports work–life balance and work engagement [Citation44]. Organisational support and one’s positive attitude towards online work are essential, as they may help to maintain work engagement [Citation44,Citation45]. Additionally, media can support local people in challenging situations, as found in this study which investigated COVID-19 related news published in one local newspaper in Northernmost Finland. Despite the fact that Sámi perspectives were not in a focus, it can reflect, in a way, general feelings and atmosphere during the pandemic. Media’s role may be even solution seeker and empowering [Citation46].

For the future, public health actions should be focused on people with lack of social support and with economic difficulties [Citation42]. Preparedness of health care systems is essential, and social efforts need to be remembered during the pandemic, together with other public sectors, e.g. education and research [Citation47]. Knowledge exchange and equal communication were highlighted among Indigenous Peoples in Canada. It should be recognised between Indigenous peoples and national, governmental and regional leaders and professionals – people should work together. It is essential to acknowledge the local needs [Citation33].

Limitations and strengths

During the content analysis process, the researcher always checked the original data in case of unclarity to verify the codes and to correct the sub-category. This was done to ensure validation of the analysis and study results. It must be acknowledged that in the qualitative analysis process, the own experiences and views of the researcher may impact the interpretation and therefore the process of the abstraction. Keeping this risk in mind, the authors of the paper discussed constantly during the analysis process, reflecting on the decisions from coding to grouping main categories. The data include a variety of representatives and operators who worked in both public and private sectors, and in different fields. The data consist of different perspectives and experiences, providing wide views related to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in the two Northernmost municipalities in Finland. Although the results cannot be generalised, they still provide a comprehensive description of the investigated area – and the information can help and support politicians and decision makers.

Conclusions

The main results of this study can be described in three parts. At first, the COVID-19 pandemic affected the lives of local people, including Sámi Indigenous Peoples. The effects were particularly seen through issues related to national borders and pressure that the pandemic caused – economically and mentally, but it also challenged service systems. Secondly, despite these challenging impacts, it seemed that everyday life with a connection to nature, togetherness, communality, and effective co-operation supported people to deal with challenges. Additionally, the pandemic situation remained better in Northernmost Finland compared to Southern Finland until early 2022. And thirdly, locality was seen as very important; it was highlighted among participants that future actions should acknowledge local needs. A deeper understanding of the overall public health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and recommended actions will provide valuable information for the development work and preparedness on the national and local levels, e.g. public health and social care in the future in similar situations. Additionally, it will provide relevant information on experiences in Sámi Land, and, therefore, has a special input to Sámi Indigenous Peoples, including their perspectives as well.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank all the participants for their time and valuable information, and researcher Kati Parkkinen, PhD, for her valuable work during the research project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Sedgwick D, Hawdon J, Räsänen P, et al. The role of collaboration in complying with COVID-19 health protective behaviors: a cross-national study. Adm Soc. 2022;54(1):29–13 . doi: 10.1177/00953997211012418

- Tiirinki H, Tynkkynen LK, Sovala M, et al. COVID-19 pandemic in Finland - preliminary analysis on health system response and economic consequences. Health Policy Technol. 2020;9(4):649–662.

- Häyry M. The COVID-19 pandemic: a month of bioethics in Finland. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2021;30(1):114–122. doi: 10.1017/S0963180120000432

- Yarmol-Matusiak EA, Cipriano LE, Stranges SA. Comparison of COVID-19 epidemiological indicators in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland. Scand J Public Health. 2021;49(1):69–78. doi: 10.1177/1403494820980264

- Mesiäislehto M, Elomäki A, Närvi J, et al. The gendered impacts of the covid-19 crisis in Finland and the effectiveness of the policy responses findings of the project “the impact of the covid-19 crisis in Finland”. Discussion paper. Helsinki: Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare; 2022 [cited 2023 June 21]. Available from: https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-800-2

- Häkkilä J, Karhu M, Kalving M, et al. Practical family challenges of remote schooling during COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. In: Proceedings of the 11th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Shaping Experiences, Shaping Society; ACM; 2020. p. 1–9. [cited 2023 June 22]. doi: 10.1145/3419249.3420155

- Koskela T, Pihlainen K, Piispa-Hakala S, et al. Parents’ views on family resiliency in sustainable remote schooling during the COVID-19 outbreak in Finland. Sustainability. 2020;12(21):8844. doi: 10.3390/su12218844

- Tiirinki H, Viita-Aho M, Tynkkynen LK, et al. COVID-19 in Finland: vaccination strategy as part of the wider governing of the pandemic. Health Policy Technol. 2022;11(2):100631. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2022.100631

- Earnshaw V, Eaton L, Kalichman S, et al. COVID-19 conspiracy beliefs, health behaviors, and policy support. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10(4):850–856.

- Rantanen N, Lieslehto J, Oksanen LAH, et al. Mental well-being of healthcare workers in 2 hospital districts during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Finland: a cross-sectional study. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2022 15;35(6):707–718. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01940

- Savolainen I, Oksa R, Savela N, et al. COVID-19 anxiety-a longitudinal survey study of psychological and situational risks among Finnish workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 19;18(2):794. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020794

- Savela RM, Välimäki T, Nykänen I, et al. Addressing the experiences of family caregivers of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(8):1812–1820. doi: 10.1177/07334648221095510

- Heinikoski S, Hyttinen T. The impact of covid-19 on the free movement regime in the north. Nord J Int Law. 2022;91(1):80–100. doi: 10.1163/15718107-91010004

- Municipality of inari. [cited 2023 June 21]. Available from: www.inari.fi

- Municipality of Utsjoki. [cited 2023 June 21] Available from: www.utsjoki.fi

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Finnish national board on research integrity TENK. [cited 2023 November 15]. Available from: https://tenk.fi/en

- Milani F. COVID-19 outbreak, social response, and early economic effects: a global VAR analysis of cross-country interdependencies. J Popul Econ. 2021;34(1):223–252. doi: 10.1007/s00148-020-00792-4

- Juranek S, Paetzold J, Winner H, et al. Labor market effects of COVID-19 in Sweden and its neighbors: evidence from administrative data. Kyklos (Oxford). 2021;74(4):512–526. doi: 10.1111/kykl.12282

- Fasil B, Sedláček CP, Sterk V. EU start-up calculator: impact of COVID-19 on aggregate employment. Scenario analysis for Denmark. Estonia, Finland, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Portugal and SwedenLuxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union; 2020. doi: 10.2760/093209

- Varanka J, Packalen P, Voipio-Pulkki L-M, et al. COVID-19 -kriisin yhteiskunnalliset vaikutukset Suomessa Keskipitkän aikavälin arvioita. VALTIONEUVOSTON JULKAISUJA. (accessed on July 3, 2023;2022:14. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-383-708-9

- Arctic Council. Covid-19 in the Arctic: Briefing Document for Senior Arctic Officials1 Senior Arctic Officials’ executive meeting Iceland 24-25 June 2020. 2020 [cited 2023 July 3]. Available from: https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/bitstream/handle/11374/2473/COVID-19-in-the-Arctic-Briefing-to-SAOs_For-Public-Release.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- Fisktjønmo GLH, Næss MW. Consequences of COVID-19 on the reindeer husbandry in Norway: a pilot study among management staff and herders. Hum Ecol. 2022;50(3):577–588. doi: 10.1007/s10745-021-00295-0

- Leppävuori J, Liimatainen H, Baumeister S. Flying-related concerns among airline customers in Finland and Sweden during COVID-19. Sustainability. 2022;14:10768. doi: 10.3390/su141710768

- Oksanen A, Oksa R, Savela N, et al. COVID-19 crisis and digital stressors at work: a longitudinal study on the Finnish working population. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;122:106853. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106853

- Oksanen A, Oksa R, Celuch M, et al. COVID-19 anxiety and wellbeing at work in Finland during 2020–2022: a 5-wave longitudinal survey study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(1):680.

- Kyrönlahti S, Neupane S, Nygård C-H, et al. Perceived work ability during enforced working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic among Finnish higher educational staff. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):6230. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19106230

- Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affective Disorders. 2020;1(277):55–64.

- Sorkkila M, Aunola K. Resilience and parental burnout among Finnish parents during the COVID-19 pandemic: variable and person-oriented approaches. Fam J. 2022;30(2):139–147. doi: 10.1177/10664807211027307

- Brooke J, Jackson D. Older people and COVID-19: isolation, risk and ageism. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(13–14):2044–2046. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15274

- Lampraki C, Hoffman A, Roquet A, et al. Loneliness during COVID-19: development and influencing factors. PloS One. 2022;17(3):e0265900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265900

- Nilsson LM, San Sebastian M, Stoor JPA. The health experience of the COVID-19 pandemic among the Sámi in Sweden: a cross-sectional comparative study. In: Spence J, Exner-Pilot H Petrov A, editors. Arctic year Book. Arctic pandemics: COVID-19 and other pandemic experiences and lessons learned. 2023 (accessed on November 15, 2023. Arctic Portal. https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2023-special-issue

- Mashford-Pringle A, Skura C, Stutz S, et al. What we heard: indigenous peoples and COVID-19. 2021 [cited 2023 July 4]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/indigenous-peoples-covid-19-report/cpho-wwh-report-en.pdf

- Power T, Wilson D, Best O, et al. COVID-19 and indigenous peoples: an imperative for action. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(15–16):2737–2741. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15320

- Curtice K, Choo E. Indigenous populations: left behind in the COVID-19 response. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1753. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31242-3

- Petrov AN, Welford M, Golosov N, et al. Lessons on COVID-19 from Indigenous and remote communities of the Arctic. Nature Med. 2021;27(9):1491–1492. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01473-9

- Cox DT, Shanahan DF, Hudson HL, et al. Doses of nearby nature simultaneously associated with multiple health benefits. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):172. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020172

- Lackey N, Deborah T, Mcnay G, et al. Mental health benefits of nature-based recreation: a systematic review. Annals Of Leisure Res. 2019;24(3):1–15.

- Timlin U, Ingimundarson J, Jungsberg L, et al. Living conditions and mental wellness in a changing climate and environment: focus on community voices and perceived environmental and adaptation factors in Greenland. Heliyon. 2021;7:e06862. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06862

- Chatwood S, Paulette F, Baker GR, et al. Indigenous values and health systems stewardship in circumpolar countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(12):1462. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14121462

- Lohiniva A-L, Dub T, Hagberg L, et al. Learning about COVID-19-related stigma, quarantine and isolation experiences in Finland. PloS One. 2021;16(4):e0247962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0247962

- Gloster AT, Lamnisos D, Lubenko J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: an international study. PloS One. 2020;15(12):e0244809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244809

- Uusiautti S, Hyvärinen S, Björkman S. The mystery of remote communality: university students’ and teachers’ perceptions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Arenas. 2021;7(1):232–249. doi: 10.1007/s42087-021-00262-7

- Subramaniam R, Singh SP, Padmanabhan P, et al. Positive and negative impacts of COVID-19 in digital transformation. Sustainability. 2021;13:9470. doi: 10.3390/su13169470

- Lilja J, Fladmark S, Nuutinen S, et al. COVID-19-Related job demands and resources, organizational support, and employee well-being: a study of two Nordic countries. Challenges. 2022;13(1):10. doi: 10.3390/challe13010010

- Parkkinen K, Timlin U, Rautio A. Local newspaper as a solution seeking actor in northernmost Finland during the COVID-19 pandemic. In: Spence J, Exner-Pilot H Petrov A, editors. Arctic year Book. Arctic pandemics: COVID-19 and other pandemic experiences and lessons learned. 2023 (accessed on August 29, 2023. Arctic Portal. https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2023.special-issue

- Aristodemou K, Buchhass L, Claringbould D. The COVID-19 crisis in the EU: the resilience of healthcare systems, government responses and their socio-economic effects. Eurasian Econ Rev. 2021;11(2):251–281. doi: 10.1007/s40822-020-00162-1