ABSTRACT

Lung cancer is one of the most commonly diagnosed cancers in Canada and a leading cause of cancer mortality. Lung cancer also affects First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples significantly in Canada, which deserves further investigation as there is a literature gap on this topic. We sought to develop a deeper understanding of lung cancer diagnosis, incidence, mortality, and survival in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada. A systematic search was conducted in bibliographic databases to identify relevant studies published between January 2000 and March 2023. Articles were screened and assessed for relevance using the Population/ Concept/ Context (PCC) framework. A total of 22 articles were included in the final analysis, of which 13 were Inuit-specific, 7 were First Nations-specific, and 2 were Métis-specific. The literature suggests that comparative incidence, mortality, and relative risk of lung cancer is higher and survival is poorer in First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. Lung cancer also has varying impact on these population depending on sex, age, location and other factors. This review illustrates that more comprehensive quantitative and qualitative lung cancer research is essential to further identify the structural causes for the high incidence of the disease.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most commonly diagnosed cancer in Canada. In 2021, an estimated 21,000 Canadians died of lung cancer, rendering it the leading cause of cancer death [Citation1]. Likewise, lung cancer is a major cause of morbidity, where outcomes reportedly disproportionately affect First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada compared to non-Indigenous Canadians (NIC) [Citation2]. Many factors influence disparities in cancer outcomes, yet very few studies have identified statistical data in the three distinguished Indigenous populations of Canada and compiled them to assess disparities among Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. In this review, we seek to explore what is known from the existing literature about the impact of lung cancer on First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples in Canada.

Background

First Nations, Inuit, and Métis are Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Evidence suggests that the health outcomes amongst these populations are significantly poorer than the country’s non-Indigenous population, especially cancer risk and mortality. Compared to the non-Indigenous population, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis are more at risk of developing cancer and other chronic diseases [Citation3–5]. A report by Health Council of Canada, 2005, showed that lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Indigenous people in Canada. In Ontario alone, the lung cancer incidence rate is 19% and 48% higher in Indigenous men and women respectively compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts [Citation6].

The high lung cancer mortality rate in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis can largely be attributed to its high incidence and late-stage diagnoses [Citation7–9]. The diagnosis of lung cancer begins with a computed tomography (CT) scan in combination with other confirmatory tests, followed by surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy or variations of these treatments throughout different phases of the patient’s treatment plan [Citation10]. A few provinces have launched organised lung screening programs for high-risk populations to increase the early diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer, including Ontario. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis as well as non-Indigenous populations who are at high risk are eligible for Ontario’s new lung cancer screening program and will be offered a special type of CT scan that uses a small amount of radiation, called a “low-dose CT scan” or “LDCT” [Citation11]. However, effectively implementing lung screening for Indigenous Peoples requires a deeper understanding of the population’s lung cancer diagnosis, incidence, mortality, and survival, as well as how it is experienced by them. Currently, the literature shows that there is a knowledge gap that needs to be addressed to better comprehend the impact of lung cancer in this population. Thus, this scoping review seeks to consolidate the current information about lung cancer amongst First Nations, Inuit, and Metis.

Materials and methods

A scoping review is a method of evidence synthesis that intends to rapidly scan existing academic literature on an existing topic while still upholding rigour and quality of results [Citation12]. A rapid initial review on PubMed and the Open Science Framework found that there are no other concurrent or existing studies that have similar aims as this review.

Acknowledging the positionality and social location of the primary author and reviewer is essential before proceeding in the analysis. James O’Grady (JO) is a settler and a scholar who does not hold lived experience of Indigeneity nor the use of health services as an Indigenous patient. Likewise, the first author does not have primary experience with lung cancer as a patient nor as a caregiver. Oversight by the Indigenous Cancer Care Unit (ICCU) at Ontario Health (OH) in which the author was employed under a research grant was required in the selection and analysis of the literature.

Three databases were searched in March 2023 using index terms and keywords related to “Indigenous”, “Canadians”, and “lung neoplasms”. The search terms were first developed for PubMed and were subsequently adapted to Scopus, Embase and CINAHL. The literature was not restricted by study design; however, it was limited to sources in the English language and by Population/Concept/Context (PCC) criteria [Citation13]. The population are peoples Indigenous to what is now Canada including First Nations (status and non-status), Inuit, and Métis groups. The concepts of inquiry are incidence, treatment, survival rates, and experience of lung cancer or lung neoplasms. The context is limited to within Canada, however there was no restriction related to province or territory. Likewise, the literature was restricted to January 2000 until March 2023. An initial search for this review reports on lung cancer amongst Indigenous Peoples in Canada found much information cited in reports and policy briefs dating back to the late 20th century. The search for this review was restricted between the years 2000 and 2023 in the hopes of capturing more up to date and relevant information on the PCC of choice. Grey literature was not included in this review.

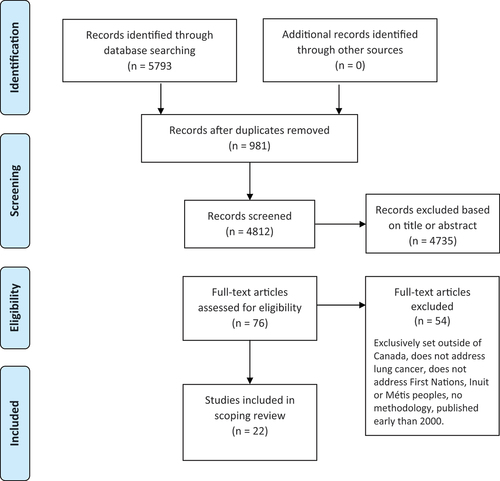

After the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of identified articles in the systematic search software of Covidence were screened, followed by a full text review by JO. The selected articles that underwent full-text review were evaluated against the inclusion criteria (). If there were any doubts, additional team members from the ICCU and Akausivik Inuit Family Health Team (AIFHT) were consulted for guidance. The literature did not undergo a critical appraisal given that scoping reviews are intended to provide an overview of existing literature rather than generate critical findings.

Table 1. Summary of included studies.

Data were compiled in an extraction form by JO. Periodic review by the ICCU ensured the minimalization of bias in the selection of charted literature. The data included in the extraction table included information on study aim, participants, context, and key findings. Given that the central focus of the scoping review were studies contextually placed in Canada amongst First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples, there was no mapping of geographic location of studies. Data extraction was an iterative process that was in accordance with the charting protocols outlined in the Arksey & O’Malley [Citation12] framework. For each article we included title, DOI, lead author, province or territory of focus, the aim of the study, its stated methods, start and end dates of analysis, population of interest, and the inclusion criteria.

The systematic search produced 5793 studies, of which 981 were duplicates and subsequently removed. A total of 4812 studies were screened by evaluating the title and abstract for relevant criteria to the aims of the scoping review. Of these screened studies, 4735 were removed. Of the 76 studies remaining for full-text review, 22 studies were selected for inclusion and data extraction. The 54 removed studies were considered irrelevant for reasons relating to study design, context, outcomes, patient population, and other indicators ().

Results

The included articles were published between 2003 and 2022 (). Of the included articles, 13 explicitly focused on Inuit [Citation14–21,Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation29,Citation34]. Seven focused on First Nations peoples [Citation22,Citation25,Citation27,Citation28,Citation30,Citation31,Citation33], while two articles were explicitly focused on Métis people in Canada [Citation28,Citation32]. Likewise, out of the extracted literature, only two articles focused on lung cancer alone [Citation21,Citation24]. The remaining twenty articles addressed or analysed cancer incidence, mortality, or patient experiences with cancer care of which lung cancer was a central aspect.

First Nations

Although reported incidences varied amongst the literature reviewed, overall, the literature suggests that lung cancer is a serious health concern for First Nations communities in Ontario [Citation28]. ’s study found that the incidence rate of lung cancer to be similar between NIC and Indigenous individuals living on-reserve. Contrastingly, First Nations living off-reserve had a reportedly much higher incidence. Given the cultural and geographic vastness of First Nations communities, the risk of lung cancer also varied regionally. First Nations adults in the Atlantic Provinces and Ontario had the highest relative risk compared to non-Indigenous individuals in the same province (RR = 1.49, 95%CI = 1.15–1.94; RR = 1.30, 95%CI = 1.15–1.55) [Citation28]. In Québec, out of all cancer risk in Indigenous men and women living on-reserve, lung cancer ranked second [Citation25]. In British Columbia, one study noted that lung cancer incidence was comparatively lower amongst First Nations men and women compared to non-Indigenous residents of the province [Citation30]. Interestingly, once adjusted for income and rurality, the relative risk of lung cancer in First Nations decreased, indicating that low income and rurality influence lung cancer risk [Citation28]. On the contrary, Withrow et al., 2017 [Citation33] found that adjusting for income or rurality still translated into a higher excess mortality rate ratio for First Nations individuals with lung cancer nationally.

[Citation31] found that between 1992 and 2001, First Nations adults were just as likely to be seen at specialised cancer centres as non-Indigenous Ontarians, indicating that differing risk may be due to a need for prevention programs. During the period of 1991–2010 [Citation22], found that incidence rates of lung cancer increased significantly for First Nations women compared to non-Indigenous women in Ontario. First Nations and non-Indigenous men in Ontario both had decreasing incidence rates during this period [Citation22]. In a review of cancer in circumpolar contexts [Citation34], found that the age standardised incidence of lung cancer amongst male and female Dene peoples, a First Nations, o be second highest in the world.

Inuit

Much of the literature extracted in this review specifically addressed lung cancer in Inuit, illustrating high incidence and low survival [Citation14–21,Citation23,Citation24,Citation26,Citation29,Citation34]. Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in Inuit Nunangat, demonstrating 36% of all cancers amongst Inuit men and 27% amongst Inuit women [Citation15]. [Citation20] supported this statistic by noting that 32% of all cancers were of the lung. Nunavut had the highest lung cancer rate with an age-standardised incidence rate of 123.0 per 100,000 for Inuit males and 121.6 per 100,000 for Inuit females [Citation16]. Compared to NIC men and women, lung cancer incidence is about 1.5 times higher amongst Inuit men and between 2 and 3 times higher amongst Inuit women [Citation18]. Two major themes were identified in the literature related to cancer care among Inuit: late diagnoses and travel to receive care.

Late diagnoses

Several studies found that lung cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival among Inuit notably differed from NIC. In one retrospective review by [Citation14] 31% and 46% of referred patients already had stage III and stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Of those with small-cell lung cancer, 61.5% of cases were diagnosed with advanced stage disease. Interestingly, Inuit women were more likely to be referred for radiotherapy or chemotherapy than men, despite relatively comparable incidence rates between the two groups. The same review also found that Inuit patients with lung cancer had an overall median survival of 10 months (95% ci: 6.1 to 13.9 months). In one study conducted in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut from 1987–1996, mortality from lung cancer was found to be almost four times higher than the Canadian national average, indicating that elevated mortality rates are not a new challenge but one that has been ongoing for decades [Citation26].

[Citation21] conducted the first histological and genotypic characterisation of lung cancer amongst Inuit in Canada. The authors utilised medical records and tumour samples from deceased Inuit patients referred from the Eastern Arctic to TOHCC between 2001 and 2011 with a lung cancer diagnosis. Both Inuit men and women were diagnosed with later stage cancers. In the observed cases of this study, 38% and 50% of tumours were stage III and stage IV at time of diagnosis amongst Inuit men [Citation21]. Amongst Inuit women, 33% and 40% of tumours were stage III and stage IV [Citation21]. Furthermore, 56.7% and 44.7% of Inuit men and women had squamous cell carcinomas compared to 28% and 16.2% of lung cancer cases in the NIC population [Citation21]. Likewise, Inuit had a higher incidence of adenocarcinoma in comparison to the NIC population [Citation21].

A retrospective review of Inuit patients from Nunavut treated with radiotherapy at TOH between 2005 and 2014 found that of all participants, 58% were treated palliatively, with 70% of these cases being diagnosed at stage IV and 72% of patients undergoing palliative care having lung cancer [Citation17].

Medical travel

Limited access to care and/or long travel distances to access care were themes that arose consistently in the literature relating to Inuit patients with lung cancer. The shortest distance to receive care for lung cancer would be to travel over 2,000 km from Iqaluit, Nunavut to Ottawa, Ontario [Citation23]. [Citation17] identified that 74% of Inuit patients lived outside of Iqaluit, in more remote settings, and that 73% of patients did not speak English. Around 70% of Inuit diagnosed with cancer travel to urban areas for treatment [Citation23]. Despite a relatively quick median referral time for specialist care in Ottawa of 4 days (within a range of 0–97), patients often spent a median 64.5 days in Ottawa [Citation17]. Concerningly, the median survival time of all cancers was 5.2 months, where patients often spent at least 2 months out of their final 6 months away from family and friends [Citation17]. However, these articles did not cover how the medical travel is experienced by Urban Inuit during their extended time away from home.

Métis

Only two extracted articles explicitly addressed the intersection of Métis people and lung cancer. In one Alberta study, the age standardised incidence rate of lung cancer was statistically higher in Métis people (RR = 1.47, CI 1.14–1.80; p = 0.02) compared to non-Indigenous peoples [Citation32]. The study also found that 33% of all cancer mortalities were due to lung cancer, compared to 25% for non-Indigenous peoples [Citation32]. [Citation28] also noted a higher lung cancer mortality rate in Métis women yet a heightened lung cancer incidence amongst Métis men nationally.

Discussion

The literature extracted in this scoping review suggests that lung cancer incidence is generally higher for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples across Canada with notable differences amongst each group.

The literature pertaining to First Nations peoples tends to be quantitative, often using data from the census or other databases. Although quantitative data can provide a broad understanding on incidence, prevalence, and mortality, it is not clear how lung cancer is experienced by First Nations individuals and their families, or the ways in which cancer care may or may not be culturally safe for First Nations populations. Further, the literature often provided contrasting evidence. For example, one study found that adjusting for income and rurality reduced lung cancer risk [Citation28] while another found that the adjustment translated into a higher excess mortality ratio [Citation33].

Similarly, First Nations individuals were just as likely to be seen at specialised cancer centres in Ontario [Citation31], yet First Nations individuals with lung cancer had a higher mortality ratio. These findings suggest that there is a qualitative gap not being addressed in the literature, such as how racism or structural and social determinants of health contribute to health disparities in First Nations peoples, rather than using individual behaviour as an explanatory factor [Citation35–37].

Amongst Métis people, the literature reviewed is broadly about cancer and there are no further studies at the time of search that investigated in detail lung cancer and Métis, despite it being one the most common cancers by incidence and mortality [Citation28,Citation32]. Furthermore, it is unclear how Métis people experience the healthcare and cancer care systems in Canada, given the lack of Non-Insured Health Benefits recognition and whether there exists culturally safe care.

There are a notably larger number of publications that specifically address Inuit and lung cancer in Canada, however these mostly describe the cancer trends rather than examining factors contributing to these trends. Although it is a net positive that there exists an abundance of literature that describe lung cancer amongst Inuit, future studies could consider research practices, health treatments, and prioritising Inuit decision making or agency. This would be beneficial in addressing the research gap concerning Inuit patient-provider experiences in lung cancer care. Qualitative research approaches that are Indigenous-sensitive and done in respectful partnership with First Nations, Inuit, Metis, and Urban Indigenous organisations and communities would help bridge this gap, as such research would contextualise quantitative data depicting high incidence and mortality rates.

Of the information that is available on lung cancer in Inuit, several other themes emerged that are worth discussing: high incidence rates, late diagnoses, remote living without much access to even primary care, and the impact of travel on decision-making, screening, and treatment outcomes. Inuit have much higher incidence rates compared to NIC [Citation15,Citation16,Citation18,Citation34]. It is also much more common for cancer in Inuit patients to be diagnosed at later stages. Resultingly, cancer mortality rates are higher in Inuit compared to NIC. Many studies attribute these outcomes to the high rates and intensity of smoking within Inuit. However, other risk factors such as environmental exposure, pollution, and nutritional deficiencies from food insecurity may also be contributing to this higher incidence of lung cancer in this population, which identifies areas for further research on preventive measures. Structural components of the healthcare system such as availability and access to health care services, including preventive services such as lung cancer screening, and the need to travel to receive health care further contribute to poorer lung cancer outcomes. Qikiqtani General Hospital, the only major hospital in Iqaluit, received its first CT scanner in 2014. The addition of CT scan may have alleviated some barriers but there are other factors that may still be affecting different variables regarding lung cancer. Moreover, there is not enough documentation in literature about the quality and barriers to healthcare experienced by Inuit in-transition during their time away from home including those temporarily living in urban centres for extended periods of time.

Future studies could focus on the qualitative experiences of lung cancer amongst First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. More specifically, research that addresses the patient-provider experience throughout the care journey from diagnosis to treatment or palliative care would provide an essential perspective for policymakers and other researchers. Likewise, more thorough quantitative data using linked data and cancer registry data is essential to better understand lung cancer outcomes. Importantly, this research should be done by engaging in meaningful research partnerships with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis medical centres, groups and communities rather than relying heavily on census data or postal code estimates to identify First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples and lung cancer data. Furthermore, census data and postal code estimates have been proven to significantly underestimate and underrepresent Indigenous health statistics [Citation38–47]. Future research could also aim to be strengths-based, identifying individual or First Nations, Inuit, and Metis population strengths that may promote wellbeing. Prospective research could identify areas of cultural resilience that can be leveraged to reduce the burden of lung cancer.

The literature in this field remains scarce. The search terms and PCC framework further narrowed the scope of material resulting in only 22 included studies, which is significantly fewer articles than most scoping reviews. Nonetheless, the PCC approach allowed for a precision in search terms that would not have been possible using another search protocol. Furthermore, the topic of lung cancer amongst Indigenous Peoples in Canada is a limited topic that can be characterised by a dearth of comprehensive quantitative and qualitative research. This review summarised relevant studies to provide a general overview of the research on lung cancer for three distinct populations in Canada and describe some of the unique challenges and strengths of each group highlighted by the literature. The breadth of literature included in the scoping review could have been expanded by considering jurisdictional areas beyond Canada. However, due to the specific lung cancer screening environment in Canada, where programs are being developed, the aim was to ensure the findings were highly relevant.

Conclusions

The literature published from 2000 till 2023 highlights that lung cancer incidence and mortality tend to be disproportionately higher in First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples compared to the non-Indigenous population in Canada, and lung cancer survival is poorer in these populations.

However, there are still research gaps in the discussion of lung cancer incidence amongst First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Given this, to better support evidence-informed policy recommendations and interventions to improve the lung cancer care, further research is necessary to better understand the health, social, economic, and political mechanisms that influence poorer lung cancer outcomes amongst First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.

Additional References for Lung Cancer Scoping Review.docx

Download MS Word (19.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2024.2381879.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Statistics Canada. Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in Canada. [cited 2022 Jan 4]. Available from: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/238-lung-cancer-leading-cause-cancer-death-canada

- Cancer Care Ontario. Cancer fact: lung cancer incidence higher in first nations people than other people in Ontario. [cited 2019 Nov]. Available from: cancercareontario.ca/en/cancerfacts

- Elias B, Kliewer EV, Hall M, et al. The burden of cancer risk in Canada’s indigenous population: a comparative study of known risks in a Canadian region. Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:699–10. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S24292

- Horrill TC, Linton J, Lavoie JG, et al. Access to cancer care among indigenous peoples in Canada: a scoping review. Soc Sci Med. 2019;238:112495. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112495

- Meharg DP, Naanyu V, Rambaldini B, et al. The global alliance for chronic diseases researchers’ statement on non-communicable disease research with indigenous peoples. Lancet Glob Health. 2023;11(3):e324–e326. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00039-6

- Borondy-Kitts A. Patient perspective on lung cancer screening and health disparities. J Thorac Oncol. 2021 Mar 1;16(3):S76–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.030

- Chen Y, MacIsaac S, Young M, et al. Nunavimmi puvakkut kaggutimik aanniaqarniq: Qanuilirqitaa? Lung cancer in Nunavik: how are we doing? A retrospective matched cohort study. CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J = J de l’Assoc Medicale Canadienne. 2024;196(6):E177–E186. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.230682

- Horrill TC, Dahl L, Sanderson E, et al. Cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis and outcomes among manitoba first nations people living on and off reserve: a retrospective population-based analysis. CMAJ Open. 2019;7(4):E754–E760. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20190176

- Klein-Geltink J, Saskin R, Manno M, et al. Cancer in the Métis Nation of Ontario Technical Report. Ottawa: Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences: The Métis Nation of Ontario; 2012.

- Canadian Cancer Society. Diagnosis of lung cancer. 2020 May. Available from: https://cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-types/lung/diagnosis

- Cancer Care Ontario. Lung cancer. 2024. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/types-of-cancer/lung

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. 2020. https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL

- Asmis TR, Febbraro M, Alvarez GG, et al. A retrospective review of cancer treatments and outcomes among Inuit referred from Nunavut, Canada. Curr Oncol. 2015;22(4):246–251. doi: 10.3747/co.22.2421

- Carrière GM, Tjepkema M, Pennock J, et al. Cancer patterns in Inuit Nunangat: 1998–2007. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2012;71(1):18581. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v71i0.18581

- Chan J, Friborg J, Chernov M, et al. Access to radiotherapy among circumpolar Inuit populations. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(10):e590–e600. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30394-8

- Chan J, Linden K, McGrath C, et al. Time to diagnosis and treatment with palliative radiotherapy among inuit patients with cancer from the arctic territory of Nunavut, Canada. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020;32(1):60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2019.07.001

- Kelly J, Lanier A, Santos M, et al. Cancer among the circumpolar inuit, 1989-2003. II. Patterns and trends. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(5):408–420. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i5.18349

- Friborg JT, Melbye M. Cancer patterns in Inuit populations. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(9):892–900. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70231-6

- Galloway T, Horlick S, Cherba M, et al. Perspectives of Nunavut patients and families on their cancer and end of life care experiences. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2020;79(1):1766319. doi: 10.1080/22423982.2020.1766319

- Goss GD, Spaans JN, Huntsman D, et al. Histologic and Genotypic Characterization of Lung Cancer in the Inuit Population of the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Curr Oncol (Toronto, Ont). 2022;29(5):3171–3186. doi: 10.3390/curroncol29050258

- Jamal S, Jones C, Walker J, et al. Cancer in first nations people in Ontario, Canada: incidence and mortality, 1991–2010. Health Rep. 2021;32(6):14–28. doi: 10.25318/82-003-x202100600002-eng

- Jull J, Sheppard AJ, Hizaka A, et al. Experiences of inuit in Canada who travel from remote settings for cancer care and impacts on decision making. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):328. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06303-9

- Kirk LG, Hammond A, Nwafor A, et al. Improving treatment experience for nunavut patients with lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;104(1):247. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.01.054

- Louchini R, Beaupré M. Cancer incidence and mortality among Aboriginal people living on reserves and northern villages in Quebec, 1988-2004. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008;67(5):445–451. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v67i5.18355

- Macaulay A, Orr P, Macdonald S, et al. Mortality in the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut, 1987-1996. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63(Suppl 2):80–85. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v63i0.17819

- Marrett LD, Chaudhry M. Cancer incidence and mortality in ontario First Nations, 1968-1991 (Canada). Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14(3):259–268. doi: 10.1023/a:1023632518568

- Mazereeuw MV, Withrow DR, Diane Nishri E, et al. Cancer incidence among First Nations adults in Canada: follow-up of the 1991 census mortality cohort (1992–2009). Can J Public Health. 2018;109(5–6):700–709. doi: 10.17269/s41997-018-0091-0

- McDonald JT, Trenholm R. Cancer-related health behaviours and health service use among Inuit and other residents of Canada’s north. Soc Sciamp; Med (1982). 2010;70(9):1396–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.008

- McGahan CE, Linn K, Guno P, et al. Cancer in first Nations people living in British Columbia, Canada: an analysis of incidence and survival from 1993 to 2010. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28(10):1105–1116. doi: 10.1007/s10552-017-0950-7

- Nishri ED, Sheppard AJ, Withrow DR, et al. Cancer survival among First Nations people of Ontario, Canada (1968-2007). Int J Cancer. 2015;136(3):639–645. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29024

- Sanchez-Ramirez DC, Colquhoun A, Parker S, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality among the Métis population of Alberta, Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75(1):. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v75.30059

- Withrow DR, Pole JD, Nishri ED, et al. Cancer survival disparities between First Nation and non-aboriginal adults in Canada: follow-up of the 1991 census mortality cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(1):145–151. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0706

- Young TK, Kelly JJ, Friborg J, et al. Cancer among circumpolar populations: an emerging public health concern. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2016;75(1):29787. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v75.29787

- Paradies Y. Colonisation, racism and indigenous health. J Pop Res. 2016;33(1):83–96. doi: 10.1007/s12546-016-9159-y

- Turpel-Lafond ME. In plain sight: addressing indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in B.C. Health care. Addressing racism review data report. 2021.

- McLane P, Mackey L, Holroyd BR et al, Impacts of racism on first nations patients’ emergency care: results of a thematic analysis of healthcare provider interviews in Alberta, Canada. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:804. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08129-5

- Smylie J, Firestone M. Back to the basics: identifying and addressing underlying challenges in achieving high quality and relevant health statistics for indigenous populations in Canada. Stat J IAOS. 2015;31(1):67–87. doi: 10.3233/SJI-150864

- Chiefs of Ontario, Cancer Care Ontario, and Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences. Cancer in first nations people in Ontario: incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence. 2017. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/sites/ccocancercare/files/assets/CancerFirstNationsReport.pdf

- Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How is lung cancer diagnosed and treated? 2022 Oct 26. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/diagnosis_treatment.htm

- Fraser J. Rendering inuit cancer “visible”: geography, pathology, and nosology in Arctic cancer research. Sci Context. 2020;33(3):195–225. doi: 10.1017/S0269889721000016

- Government of Canada. Indigenous peoples and communities [ Administrative page; fact sheet; resource list]. 2009 Jan 12. Available from: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100013785/1529102490303

- Government of Canada DOJ. Department of justice—principles respecting the government of Canada’s relationship with indigenous peoples. 2017 July 14. Available from: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles-principes.html

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. About Canadian inuit. 2024. Available from: https://www.itk.ca/about-canadian-inuit/

- Mazereeuw MV, Withrow DR, Nishri ED, et al. Cancer incidence and survival among métis adults in Canada: results from the Canadian census follow-up cohort (1992-2009). CMAJ: Can Med Assoc J = J de l’Assoc Medicale Canadienne. 2018;190(11):E320–E326. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.170272

- Métis Nation of Ontario. Culture & heritage – who are the métis? Available from 2024. Available from: https://www.metisnation.org/culture-heritage/#:~:text=The%20M%C3%A9tis%20are%20a%20distinct,unions%20were%20of%20mixed%20ancestry

- Orisatoki R. The public health implications of the use and misuse of tobacco among the aboriginals in Canada. Global J Health Sci. 2013;5(1):28–34. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n1p28