Abstract

European railways have been reorganized to allow for market competition. Thus, train services have been vertically separated from infrastructure management which allows several operators to compete. Different ways have emerged for vertical separation, capacity allocation and track access charges. This paper reviews important deregulation aspects from a number of European countries. The study compares how competition has been introduced and regulated with focus on describing capacity allocation and track access charges. Although guided by the same European legislation, we conclude that the studied railways have different deregulation outcomes, e.g. market organization, capacity allocation. Besides, few countries have so far managed to have efficient and transparent capacity allocation. Although allowed by the legislation, market-based allocation is absent or never used. To foster more competition which can yield substantial social benefits, the survey indicates that most European railways still need to develop and experiment with more efficient and transparent capacity allocation procedures.

1. Introduction

In the past, railway markets in most European countries were organized as single monopolistic companies controlling both infrastructure and railway services. In recent decades, however, many countries have introduced competition in railway markets by vertical separation, i.e. separating the responsibility for infrastructure from the provision of railway services for freight and passengers. Such developments have been further stimulated by the European legislation EC (Citation1991, Citation2001, Citation2012, Citation2016b).

These recent reforms in Europe have brought new and various types and variants of market organizations, capacity allocation and track access charging. Allowing different (often competing) operators on the same track means that their capacity requests may come into conflicts. The process of allocating capacity and resolving conflicting capacity requests is therefore central for the functioning of these railway markets. This is highlighted in several studies in the literature (Gibson Citation2003) as well as by the European legislation (EC Citation2001). Ideally, the conflict resolution process needs to be both transparent, i.e. clear and non-discriminatory, and efficient, i.e. lead to societally and economically optimal outcomes. Such capacity conflicts may occur also in other vertically separated and deregulated markets, e.g. telecommunications (Klein Citation1999) and air transportation (Gilbo Citation1993), but these are not nearly as complex and have been more extensively researched compared to the railway sector.

This review provides an updated overview of the European railway deregulation focusing on capacity allocation and track access charges. Both are crucial instruments in deregulated railway markets where different operators compete for capacity. Based on the analysis of publicly available documents, we perform an up-to-date comparison (in selected markets) on how competition was introduced and regulated, how capacity is allocated between competing train operators, and how track access charges are levied. The survey aims to add to the existing literature by describing, comparing and discussing various existing approaches in Europe. The current review is also one of relatively few studies that is the result of extensive desk research based directly on the national network statements, i.e. official documents providing descriptions of, among others, capacity allocation and track access charges.

The paper starts with this introductory section. Section 2 presents the main existing related surveys in the literature, some general information on railway market organizations, and an overview of European Union (EU) railway market policy and legislation. The main part of this paper is in Section 3 where we review the railway deregulation in a number of markets, selected to illustrate a range of different market organizations and capacity allocation processes. Section 4 concludes the review.

2. Existing surveys

Structural reforms of European railway markets date back to the first European directive (EC Citation1991), but the questions about market organization and capacity allocation are older. A number of existing surveys have reviewed, compared and/or analyzed aspects of these reforms, e.g. market organization, competition, capacity allocation and access charges. In this section, we present some related studies, and show how our study contributes to the existing literature. Table provides a comparison between this paper and the main existing surveys in terms of the main reviewed aspects as well as the studied markets.

Table 1. Comparative overview of existing surveys.

In the late 1980s and after the pioneering vertical separation and deregulation in Sweden, Hansson and Nilsson (Citation1991) described the market reorganization, institutional aspects and practical problems inherent to the new reforms. After directive 91/440 (EC Citation1991), a few other countries (e.g. the UK and Germany) followed shortly after Sweden, and new market organizations emerged. Monami (Citation2000) compared different organizational models in certain markets (i.e. Belgium, France, Germany, the UK), and identified key dimensions to describe each model and how they are connected.

In 2001, the directive 2001/14/EC set guidelines for railway capacity allocation and track access charges (EC Citation2001). Since then, railway market reforms have been successively implemented in many other member states of the European Union (EU), and more studies have followed covering more aspects of the reforms. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) published a comprehensive summary of the structural reforms that have happened in all the OECD member countries (OECD Citation2005). Another extensive survey by Laurino, Ramella et al. (Citation2015) reviewed the market organization in 20 countries worldwide with different regulatory approaches to deal with the monopolistic nature (i.e. natural monopoly) of railway infrastructure.

There are many reviews on competition and/or efficiency in railway markets. In Germany, Link (Citation2004) discussed the problems facing on-track competition in the regional passenger market by analyzing the effects of access conditions and charges. In a similar Swedish study, Alexandersson and Rigas (Citation2013) studied the European effects of the Swedish policy for opening access to the passenger market since 1988 until the complete deregulation in 2012. In a related comparative study, Nash, Nilsson et al. (Citation2013) reviewed the introduction of competition in Britain, Germany and Sweden. With increasing competition on open access passenger lines in the Czech Republic, Tomeš, Kvizda et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016) reviewed several effects at the national level, e.g. price, frequency and service quality. However, few studies, e.g. the policy paper by Crozet, Haucap et al. (Citation2014), focus on competition in freight traffic. At the European level, Crozet, Nash et al. (Citation2012), in a report for the Centre on Regulation in Europe (CERRE), discussed vertical separation as a first attempt to increase railway efficiency. Based on analyzing lessons from opening markets to competition, the authors identified key issues and policy recommendations to tackle the regulatory challenges for the implementation of competition in the European markets. Similar topics were also discussed within the OECD’s policy competition roundtables on the recent development in railway markets (OECD Citation2013). A later study by CERRE focused on the liberalization of passenger rail services, the authors reviewed and analyzed the markets in France (Crozet Citation2016b), Germany (Link Citation2016), Great Britain (Smith Citation2016) and Sweden (Nilsson Citation2016). Closely related, a discussion paper from the International Transport Forum (ITF) by Crozet (Citation2016a) described how competition was introduced in several European countries.

A number of authors have focused on the efficiency and performances of different market organizations, e.g. Jensen and Stelling (Citation2007), Asmild, Holvad et al. (Citation2009), Friebel, Ivaldi et al. (Citation2010), Van de Velde, Nash et al. (Citation2012), Nash, Smith et al. (Citation2014) and Abbott and Cohen (Citation2017). Although important, these aspects fall mostly outside the scope of the current survey.

Reviews of capacity allocation and conflict resolution processes are more scarce, but there are some, mostly covering a relatively small number of countries each. An early paper by Gibson (Citation2003) examined the problem of railway capacity allocation and congestion-based track charges in the UK. The author distinguishes between rule-based, cost-based and market-based allocations. Bouf, Crozet et al. (Citation2005) focused on conflict resolutions in the allocation process in France and Britain. The study looked specifically at the dispute/conflict resolution systems between the infrastructure manager (IM) and railway undertakings (RUs) as a result of the vertical separation. A more recent study by Smoliner, Walter et al. (Citation2018) analyzed how capacity allocation (referred to as timetable coordination) have been recently implemented for open access traffic in Austria, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands.

As to track access charges, Crozet (Citation2004) reviewed the charging systems in several European countries a few years after the 2001 directive (EC Citation2001). The author attempted to find some best practices for infrastructure charging easily transferable between countries. While attempting to define railway capacity, Kozan and Burdett (Citation2005) developed an access charging methodology that is more suitable for vertically separated railways. The European Conference of Ministers of Transport (ECMT) also reported several challenges for access charges in the different OECD’s member states (ECMT Citation2005). Thus the need to develop and promote more coherent charging systems. A more specific report from the International Union of Railways (UIC) focused on noise-related access charges in Europe (UIC Citation2009). In another recently published study by CERRE, case studies reviewed how track access charges are levied in four European railways, i.e. France (Crozet Citation2018), Germany (Link Citation2018), Sweden (Nilsson Citation2018) and Great Britain (Smith and Nash Citation2018).

In addition to the papers that deal with capacity allocation in vertically integrated markets, e.g. by Talebian, Zou et al. (Citation2018), an increasing number of studies focuses on deregulated markets and looks at the potential of using market-based methods to allocate capacity, e.g. using congestion charges/pricing and/or bidding processes. An early attempt by Nilsson (Citation2002), on capacity allocation to competing operators, described an auctioning procedure to improve the outcome welfare based on the operators’ willingness-to-pay for capacity. To bridge the gap between theory and practice, Perennes (Citation2014) describes the application of combinatorial auction to allocate capacity in deregulated markets. Different types of (hybrid) auctions have been further simulated by Stojadinović, Bošković et al. (Citation2019) using iterative capacity allocation algorithms. In a doctoral thesis, Pena-Alcaraz (Citation2015) studies the capacity allocation in a deregulated market (referred to as shared railway in the American context), and investigates a solution that combines operations (train timetabling) and infrastructure management (capacity pricing). A recent thesis by Ait Ali (Citation2020) describes a new market-based approach to allocate capacity between subsidized and commercial train services using differentiated congestion pricing as part of the track access charges.

3. Railway deregulation in Europe

In this section, we review several aspects that relate to the railway deregulation. In particular, we present the European reforms and legislation, and analyze the market organization, vertical separation, competition, capacity allocation and track access charges. These aspects are reviewed and discussed in the context of the following European countries: Austria (AT), Belgium (BE), the Czech Republic (CZ), France (FR), Germany (DE), Great Britain (GB, Northern Ireland is omitted), Italy (IT), the Netherlands (NL), Spain (ES), Sweden (SE) and Switzerland (CH).

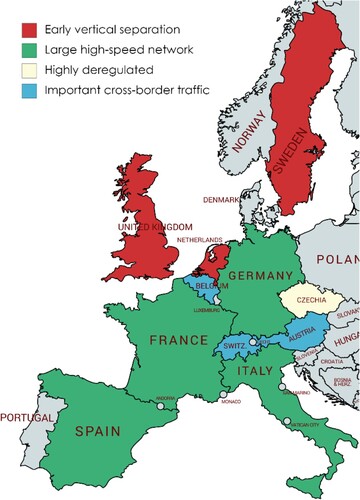

The selected markets illustrate different market organizations, and various ways capacity is allocated, and have been selected as examples for various reasons. Some railways were early adopters of vertical separation (i.e. SE, GB, NL) or highly deregulated (e.g. CZ) while others have important European cross-border traffic (e.g. AT, BE and CH) or extensive high-speed networks (e.g. FR, DE, IT and ES). These reasons all mean that these railway markets have to deal with potentially complex issues regarding regulation and competition, and hence their regulatory processes and framework provide interesting insights and conclusions as European railway markets become increasingly deregulated and potentially more open for competition between several operators. Note that some markets are selected for more than one cited reason. Moreover, Japan (JP) and the United States (US) are briefly mentioned in certain discussions, mainly to contrast with their special market organizations which are presented in more details later in this section. Figure presents a map showing the selected railways and main selection reasons.

Figure 1. Map of the studied European railways and the corresponding main reason for selection (created using mapchart.net).

The selected markets are used as case studies that serve for illustration, analysis and discussion, and were also selected based on data availability to illustrate the broader range of market organization and competition, capacity allocation and access charges. For that, country-specific documents are used as the primary source material, most importantly the latest national network statements describing (among other things) capacity allocation and access charges. These are complemented with updated information from recent comparative studies. Secondary references, e.g. reports and data from inter-governmental organizations and academic papers, are also used but to a less extent.

A historical overview is first presented including the main developments toward the deregulation of the European railway. Second, different market organizations are described and discussed before focusing on vertical separation. A review of competition and capacity allocation follows. This section is concluded with a brief discussion on track access charges and their use to solve capacity conflicts.

3.1. Historical overview

Early railways were built, operated, maintained and owned by private companies. Railway networks continued their expansion thanks to the many private investors during the industrial revolution (sometimes called the railway mania). Further developments, such as increasing passenger traffic and fierce competition between investors, made governments pay increasing attention to rail transport. A combination of railways’ growing societal importance, decreasing profitability for railway companies and a strive to take advantage of various economies of scale made most (although not all) European countries nationalize large parts of the railway networks and establish national railway monopolies during the early twentieth century.

During the late twentieth century, the railway sector faced new challenges such as declining rail modal share due to increasing competition from other modes. Decreasing efficiency and increasing government expenditures with poor performances meant that state-controlled railways came under pressure (OECD Citation2005), and a trend of deregulation reforms emerged to allow private actors in the market once again (Laurino, Ramella et al. Citation2015). Sweden was the first country to initiate such deregulation (as early as 1988) after the vertical separation between railway operations and infrastructure management (Hansson and Nilsson Citation1991). SJ (that managed the Swedish railways until 1988) became a railway undertaking (i.e. operator) whereas the infrastructure management was transferred to Banverket (the Swedish Rail Administration). In 2001, SJ was further split into several state-owned companies (e.g. the passenger operator SJ and the freight operator Green Cargo). In 2010, Banverket was merged with Vägverket (the Swedish Road Administration) to form Trafikverket (the Swedish Transport Administration).

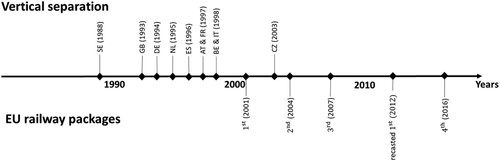

After the Swedish deregulation and to stop the decline in the rail sector and increase its competitiveness, several EU reforms and policies have been introduced as early as 1991 in the form of different directives and regulations grouped in successive railway packages. The European Commission (EC) first introduced directive 91/440/EEC about vertical separation distinguishing between three alternatives, i.e. accounting, organizational and institutional separation (EC Citation1991). The first type guarantees separate financial accounts and the second is about independent units within one larger institution and the third is complete separation. The directive required at least a separation in terms of accounting. A timeline in Figure shows the history of European vertical separation as well as EU railway packages. Note that slight differences may exist between the reported years of separation in the different sources since reforms often occur in the end/beginning of the year. However, Figure is mainly based on data reported by Friebel, Ivaldi et al. (Citation2010).

Figure 2. Timeline of EU railway packages and vertical separations, data by Friebel, Ivaldi et al. (Citation2010).

Several EU member states followed to vertically separate their national railways before the 1st railway package in 2001 (EC Citation2001) as illustrated in Figure , except for the Czech republic where separation occurred in 2003, shortly before joining the EU in 2004 (Tomeš, Kvizda et al. Citation2014). The deregulation of a number of train services followed, e.g. international and long-distance passenger, freight, and maintenance (Monami Citation2000; Nash Citation2008). These reforms came as a response to different calls from the European Commission (EC) to, among other things, promote transparent access and efficient utilization of existing rail infrastructure (EC Citation2001) in a Single European Railway Area or SERA (EC Citation2012). Table presents different European railway legislation (including the railway packages in Figure ) and the corresponding treated issues.

Table 2. European railway legislation and its main topics (and/or requirements).

The first directives focused on the fundamental reforms of the market reorganization and regulation, e.g. vertical separation and licensing. The 1st package of 2001 required all EU markets to be vertically separated (at least in accounting), making their markets ready for open access or new entrants and hence deregulation. The following packages aimed at the successive deregulation of different market segments, i.e. cross-border freight (2001), domestic freight (2004), international passenger (2007) and domestic or national passenger (2016) in the recent fourth railway package (EC Citation2016b). Thus, open access for passenger services (except for international services) has only been recently required, and competitive tendering is not yet a requirement (EC Citation2016a).

Several legislations provided guidelines for deregulation aspects such as safety, interoperability and licensing, and more importantly capacity allocation and access charges. In the SERA directive, capacity allocation is treated in the 1st pointFootnote1 of Article 39 stating that it is the responsibility of the infrastructure manager to allocate capacity in a fair and non-discriminatory manner (EC Citation2012). Another important aspect of the allocation process relates to solving conflicts between capacity applicants. In the same directive, the 4th pointFootnote2 of Article 31 as well as 3rd and 4th pointsFootnote3,Footnote4 of Article 47 treat access charges and congested infrastructure where capacity conflicts occur. The first points state that access charges can include an additional charge for scarcity. If conflicts persist, the two other points suggest the use of priority criteria to allocate capacity to the most important services to society.

3.2. Market organization

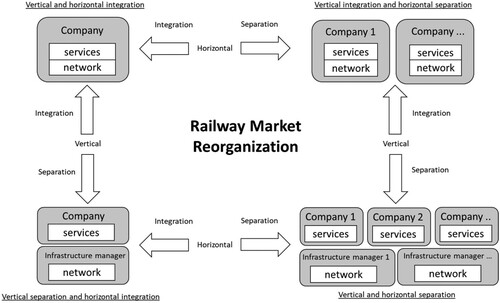

The structure of railway markets can be characterized according to the extent of vertical and/or horizontal separation (or integration). Figure illustrates the main market reorganizations based on the two dimensions. The arrows indicate the structural reforms (vertical or horizontal, separation or integration) that are needed to move from one market organization to the other.

The vertical dimension involves the division of responsibility between infrastructure management and railway services. The responsibilities of the former include tasks such as development and maintenance, traffic control and capacity allocation, sometimes also real estate and stations. As for railway services, these include running trains and related tasks such as ticket sales. Licensed operators, also called railway undertakings, are allowed to provide train services.

A common structure is vertical (and horizontal) integration, see top left in Figure . One actor, often a state-owned company, is responsible for the entire national railway system, being at the same time the infrastructure manager and a monopolistic operator. Another variant with a long history is one with several distinct railway networks or sub-markets where each is vertically integrated, see top-right in Figure . An example of the latter is Japan after the 1987 privatization of the Japanese National Railways (JNR) into Japan Railways Group JRG. The group consists of six (horizontally separate) private passenger companies (the government is the sole shareholder), organized by regions (e.g. JR Hokkaido, JR East). Each one is responsible for both infrastructure management and railway operations (vertical integration) in their respective regions (Trafikanalys Citation2014). Another example is the United States which is dominated by freight services, while passenger services have a relatively small market share. The freight market includes many private operators which generally own the infrastructure they use (vertical integration) but are separated (horizontally in infrastructure) into several distinct railway systems.

As a result of the reforms, vertical separation became the main market organization in Europe, see bottom in Figure . Although not illustrated in the figure, various forms of vertical separation exist leading to players that have different legal status, e.g. state-owned or holding companies, subsidiaries or governmental agencies. A more detailed discussion about vertically separated market organizations is presented later in the section.

The horizontal dimension concerns the relationship between different market players with similar roles or responsibilities, such as different infrastructure managers or different railway undertakings (Yeung Citation2008). In a horizontally separated market (i.e. to the right in Figure ), there may be several railway operators providing competing or complementary services (separation in services), or several infrastructure managers with responsibilities for different parts of the network (separation in infrastructure). There are various ways to allocate capacity if the market is also vertically separated (bottom-right in Figure ), e.g. franchising, competitive tendering or open access. To foster competition in such markets, no company must be discriminated or favored, and capacity allocation is regulated, as in Europe, by an independent rail regulator.

Table presents examples of market organizations in different countries. In contrast to the European markets, Japan and the US have different structures, where passenger (in JP) and freight (in the US) companies are vertically integrated (Trafikanalys Citation2014). However, the state-owned (horizontally separated) freight (in JP) and passenger (in the US) companies have certain rights regarding access to the infrastructure capacity (Talebian, Zou et al. Citation2018). Although horizontally separated, Switzerland is one of few remaining vertically integrated railways in Europe.

Table 3. Examples of market organization in different countries.

All EU member states have reorganized their railway markets by vertically (and horizontally) separating their monopolistic national railways. Although stipulated by the same European legislation, the market reorganizations (or vertical separation) were not always similar in different European markets.

3.3. Vertical separation

Already in the late 1980s, Sweden began to vertically separate their railway markets into infrastructure management and railway services (bottom-left in Figure ). This was a first step towards opening the market for competing new entrants. The vertical separation was later adopted by several EU policies, and aimed to foster competition and interoperability (EC Citation2001). The study of the effects of the reforms is outside the scope of this survey; see an analysis of the reforms in the freight markets by Ludvigsen (Citation2009), interoperability by Abbott and Cohen (Citation2017) or transaction costs for by Merkert (Citation2012).

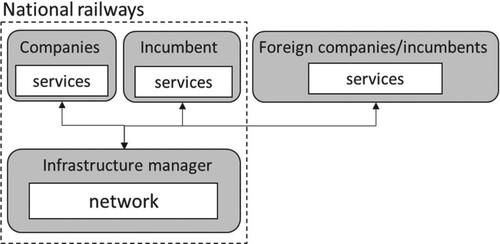

A typical example of vertical separation is when a government agency is responsible for infrastructure management, while one (incumbent) company (or more) is responsible for providing railway services. This corresponds to the bottom-right in Figure with a single main infrastructure manager as represented in Figure . The railway undertakings, responsible for operations, can include the existing incumbent (if any), new national companies and/or other players from abroad (incumbents or new entrants). These companies (privately or publicly owned) can operate passenger and/or freight services (commercial or subsidized). Note that the distinction is sometimes blurred, and no general rules exist for which services should be subsidized. In Europe for instance, commuter and regional services are often subsidized by local or central public transport agencies, but intercity, long-distance, high-speed, international and freight train services are generally market-based.

Most of the selected countries have adopted a vertically (and horizontally) separated railway market organization. The exception is Switzerland which mostly remained vertically integrated. It has adopted, however, a horizontal separation between several railway companies since there are several networks and operators mostly owning their infrastructure, the largest of which is SBB controlling around 58% of the Swiss railway network (SBB Citation2020).

There are currently two equally frequent forms of vertical separation, from the three possible alternatives that are allowed by the legislation. Table presents the vertical separation and infrastructure management in selected markets. The institutional (or complete) separation is mostly found in countries with early deregulation and high level of market competition, e.g. SE and GB. Many other countries have adopted a separation where the infrastructure management (together with the incumbent operator) is a subsidiary of a parent or holding company, e.g. DE and FR.

Table 4. Vertical separation and infrastructure management in selected European markets.

Note that Switzerland, Japan and the US are not included in the table since all are vertically integrated. In Japan and the US, infrastructure management (including capacity allocation) is the responsibility of the state-owned companies, for passengers in JP and freight in the US. Switzerland has, however, a not-for-profit agency, Trasse, which is the infrastructure manager and thus allocates capacity for licensed railway companies (e.g. SBB, BLS and SOB).

Besides the various types of vertical separation, Table shows that there are different forms for managing the infrastructure. In institutional vertical separation, the infrastructure manager may be a state-owned company which is not a subsidiary or part of any other parent or holding company unlike organizational vertical separation. Another form for infrastructure management is an independent government agency which has no commercial or business interest. Such form is found in the Netherlands with ProRail (ProRail Citation2020) and in Sweden with Trafikverket (Citation2020b).

In markets with organizational separation, the infrastructure manager is usually either a subsidiary of a holding company which is built to solely hold shares such as in Austria and Italy, or otherwise of a larger parent company which has other activities inside (and outside) the rail industry such as in Belgium, France and Germany. Both variants may lead to conflicts of interests when it comes to solving capacity conflicts, since the parent or holding company controlling the infrastructure manager may also have companies in the market. Link (Citation2004) concludes that failing to find an appropriate organizational framework could be an obstacle for fostering competition and system efficiency.

In addition to the infrastructure manager, vertically separated markets include important players such as the incumbent and the regulator. Incumbent companies may remain after the vertical (and horizontal) separation of the national railways, whereas the independent regulator exists to ensure that there are no discriminatory practices in the market, for example the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) in Britain. In some cases, no incumbent remains after the separation – this is for example the case in Britain. A list of the existing incumbent operator(s) and their relation to the infrastructure manager is given in Table for the selected markets. Note that GB and CH are not included since GB has no incumbent, and CH has a non-vertically separated market.

Table 5. The incumbent(s) in selected markets and their link to the infrastructure manager.

As mentioned before, the incumbent is completely independent from the infrastructure manager after institutional vertical separation, also called complete separation. However, in the case of organizational separation, dependencies may remain, meaning that conflicts of interests may emerge. The independent regulator must ensure that the incumbent and the infrastructure manager have no anti-competitive practices during capacity allocation to the different players in the market.

3.4. Competition

The new market organization is not an ultimate goal in itself, but a means to foster more competition in the market in order to increase the efficiency and quality of the railway sector. In this context, introducing vertical separation (and hence competition) is not even a necessary condition for good quality train services, e.g. CH. However, such separation is a necessary step towards a more competitive market as promoted by the European legislation.

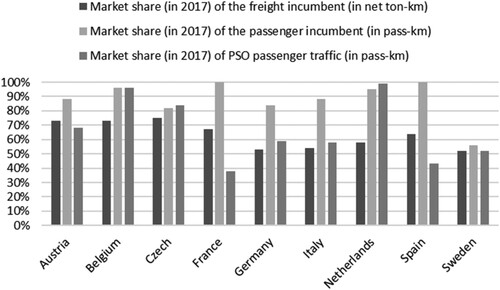

Even in vertically separated markets, the incumbent operator(s) can still hold large shares of the freight and/or passenger market. In some cases, incumbents in their own home market are themselves new entrants or have subsidiaries in other markets (e.g. the German DB and the French SNCF). The presence of a dominant incumbent as the main player in the market can sometimes prevent competition on the track (e.g. open access) as well as the upcoming competition for the track (e.g. competitive tendering). This is since benefits of scale make it difficult for new entrants to compete often due to high initial investment costs. Other entry barriers might also exist such as access to ticket sales platforms and asymmetry of information. The market shares are presented in Figure for both freight (in net ton-km) and passenger (in pass-km) incumbents in the selected markets. It also presents the market share for passenger services (in pass-km) with public service obligation (PSO) contracts. Note that GB is not included since there is no incumbent in the market.

Figure 5. Market share (in 2017) of the PSO passenger traffic (in pass-km) and the incumbent for freight (in net ton-km) and passenger services (in pass-km), data by IRG (Citation2019).

Figure indicates that incumbents have larger shares in the passenger market segment compared to the freight segment. This is partly due to the fact that a considerable share of passenger market is operated under PSO contracts, still often by the incumbents. In this context, the 4th railway package attempts to foster competition for such contracts by promoting competitive tendering as one way to award these contracts for passenger traffic (EC Citation2016b). Thus, competition in passenger markets is generally on few open access lines, e.g. West Bahn (in AT), Stockholm-Malmö line (in SE), Prague-Ostrava and Prague-Bratislava/Vienna (in CZ). In some countries (e.g. FR, ES), there is almost no competition for passenger services. The exception in this survey is Britain (with mostly franchising contracts and no incumbent) and Sweden which were both among the first countries to deregulate their markets. In addition to the competitive market for regional services, Germany has, to some extent, competitive freight market, and has also recently increased the shares of new entrants with more open access contracts for passenger services, e.g. Flixtrain. Moreover, it is important to mention that some countries (e.g. NL, BE) are mostly dominated by passenger traffic which could also play an important role in the market organization and in fostering competition.

Most of the competition in the passenger market segment is on profitable commercial lines, e.g. international long distance and high-speed lines. Competition on these lines is often in the form of open access for train path(s). Publicly controlled subsidized passenger services (e.g. regional) are also expected to have more competition in the form of competitive tendering for long term contracts. There is a substantial gray area here and drawing a clear line between these two types of services is often difficult. As a rule, intercity services are usually commercial, whereas local and regional services are often subsidized. In this context, the fourth European railway package from 2016 aims to increase competition in rail passenger markets by adopting open access for commercial lines and competitive tendering for subsidized ones (EC Citation2016a).

An important feature of vertically separated markets with high competition is that solving capacity conflicts should be done in a both transparent and (socio)economically efficient way. This is the aim, at least, in the EU (as well as GB and CH), as opposed to first ensuring the benefits of the infrastructure owners (e.g. JP and the US). Most of the reviewed countries with a low degree of competition have a market organization in which the infrastructure manager is somehow linked to the incumbent operator (e.g. BE, FR and IT). As mentioned before, this conflict of interest may discourage new entrants and decrease competition. This is particularly salient in the case of capacity conflicts in the allocation process where both new entrant(s) and the incumbent request conflicting train path(s) from an infrastructure manager which is owned by the same parent/holding company (that controls the incumbent). As described in the next sections, certain countries (e.g. FR) have more general (less precise) rules for capacity allocation and conflict resolution criteria than others (e.g. BE and IT). Such more general rules tend to increase the uncertainty for the new entrants. One way to avoid this could be to develop and use clearer conflict resolution procedures. Alexandersson and Rigas (Citation2013) also conclude that tools to address issues related to capacity allocation and access charges must be further developed.

Another issue that hinders competition is the large initial costs and financial losses related to acquiring the necessary rolling stock and operating services (Murillo-Hoyos, Volovski et al. Citation2016). New entrants often need several years to become profitable (see for example the case study by Tomeš, Kvizda et al. (Citation2016) regarding RegioJet in CZ). One way to help new entrants is to use framework agreements in the capacity allocation process for long term allocation over several annual timetables (EC Citation2016a). Most of the reviewed countries already have it in their allocation process.

3.5. Capacity allocation

In vertically separated markets, the capacity allocator (which is usually the same as the infrastructure manager) is often a subsidiary of a (state-owned) company, or sometimes a governmental agency. Table lists examples of how this can be organized. This contrasts with allocation that is made within one vertically integrated railway company as in Japan (for passenger) and the US (for freight). In this case, capacity allocation is done internally within the integrated company, and capacity conflicts never become explicit or public. In such markets, no railway regulator is needed to oversee the market in this respect.

Table 6. The capacity allocation body and the regulator in selected countries.

However, in the studied vertically separated markets the regulator is required to be independent in order to supervise the work of the infrastructure manager, and to make sure that the capacity allocation is non-discriminatory. Table indicates that the legal status of the regulator is generally similar across the studied markets. Slight differences exist as some regulators are under the control of the government (executive) whereas others are controlled by the parliament (legislature).

Although vertically integrated, Switzerland (not in the EU) ensures certain compliance with EU policies. The capacity allocation is performed by a nonprofit company (Trasse), which is under the supervision of an independent commission of experts (BAV). Thus, both the allocator and the regulator are completely independent bodies. Note, however, that the main infrastructure manager in Switzerland (SBB) also operates train services, but it does not allocate capacity.

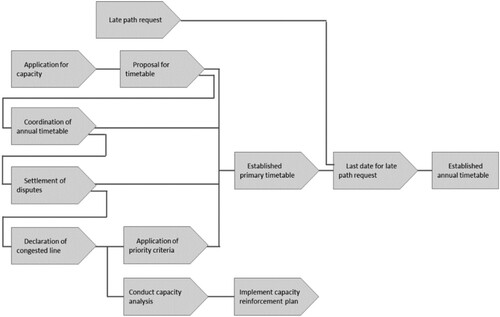

The capacity allocation in the selected vertically separated markets follows similar steps as presented in Figure which summarizes the Swedish allocation of railway capacity. The process starts with the infrastructure manager receiving applications for capacity from licensed railway undertakings. Based on the conditions and terms specified in the national network statement, the process generally starts with operators submitting train path requests with all information needed for the infrastructure manager to propose a draft of the annual timetable. Minor conflicts can usually be resolved by small adjustments of path requests, so the framework often specifies certain time intervals with which the infrastructure manager can unilaterally do adjustments (without negotiating with the applicants). Major conflicts are usually solved in a coordination process where the different applicants conduct informal discussions with the infrastructure manager to settle conflicts. These applicants can further apply for settlement of disputes if there are remaining conflicts (after the coordination process). These conflicts are usually resolved by the infrastructure manager taking a unilateral decision (without further consultation of the applicants) based a conflict resolution procedure (often priority criteria or decision rules). At this stage, the infrastructure managers are often obliged to declare the infrastructure as congested, and to conduct capacity analysis and implement reinforcement plans to improve the supply of capacity and its utilization for the next timetables. Applicants can appeal the capacity allocation decisions to the independent national railway regulator. Such appeals can be used against any discriminatory behavior from the capacity allocation body.

Figure 6. Overview of capacity allocation in the Swedish railways (Trafikverket Citation2020b).

Although capacity processes are, to a large extent, similar in the reviewed countries, specific procedures to solve capacity conflicts have been relatively developed in some markets more than in others. Major variations can be found when it comes to the settlement of disputes and/or the application of priority criteria. To illustrate these differences, Table presents a comparative overview of the priority criteria that are applied to settle capacity disputes.

Table 7. Comparative overview of priority criteria used in selected countries for solving capacity conflicts.

The table presents three criteria in their order of priority as mentioned in the national network statement in Austria (ÖBB-Infrastruktur Citation2020), Belgium (Infrabel Citation2020), Czech (SŽDC Citation2020), Germany (DB-Netze Citation2020), Italy (RFI Citation2020) and Spain (Adif Citation2020). These countries have an explicit list of criteria which is ordered in priority. Some countries list the criteria without any explicit order whereas others use models for total social costs as in Sweden (Trafikverket Citation2020a) or robustness as in France (SNCF-Réseau Citation2020).

As mentioned before, some countries with organizational separation (and mostly lower competition) have a capacity allocator with links to the incumbent which may create various conflicts of interest, and potential new entrants may see this as a risk when considering entering the market. Such conflicts and risks can be avoided with more transparent capacity allocation rules, i.e. clearer conflict resolution procedures. Table indicates that there are various procedures to allocate capacity in case of conflicting train path requests.

Table 8. Summary of the different procedures to solve capacity conflicts.

The allocation rules are mainly either based on general principles (e.g. SE, FR) or specific priority criteria (e.g. CZ). Specific criteria are clearer allocation rules that can depend on the speed (e.g. BE), the type of traffic (e.g. CZ) or the level of congestion of the infrastructure (e.g. AT). Although transparent, such rules do not always yield (socio)economically efficient allocation outcomes. Additional special rules may be applied in certain countries, e.g. CZ where the running time in any allocated train path in the country is never beyond 20 h (SŽDC Citation2020).

More general criteria require the development and use of a certain capacity allocation model. For instance, the French procedure for capacity allocation is generally based on models for improving the robustness of the final annual timetable (Perez Herrero Citation2016). In Sweden, the infrastructure manager uses an efficiency-based model that aims at evaluating the total societal benefits (and costs) of different outcomes and choose the best alternative (Trafikverket Citation2020a). These models may lead to efficient solutions but are often less transparent, e.g. unclear to the railway undertakings.

The more specific the criteria are, the more transparent the procedure becomes. However, it is not always easy to list specific and transparent priorities valid for all conflict situations since these may sometimes lead to inefficient outcomes. Market-oriented procedures exist as allocation rules in some countries in the form of auction. In addition to the track access charges, the winner pays either the second highest bid, called Vickrey auction (e.g. CH), or the highest bid (e.g. DE). Although allowed by the EU legislation, such procedures are rarely, if ever, used.

3.6. Track access charges

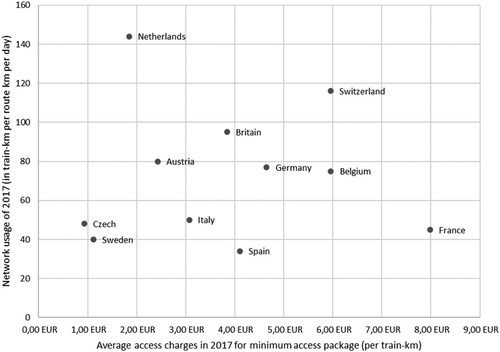

When the market was vertically integrated, i.e. the same railway company was responsible for both infrastructure and operations, there was no need for access charges. This is not the case in vertically separated markets where access charges are regulated (EC Citation2001), and become important for the capacity allocation (Nash, Crozet et al. Citation2018). For instance, too low charges can lead to capacity overutilization from railway undertakings and financial deficit for the infrastructure manager(s), whereas too high charges can lead to capacity underutilization. This relationship between network capacity utilization and track access charges is presented in Figure . Note that the access charges in the figure are calculated as the average charges that are paid by a (freight/passenger) railway undertaking (per train-km) to the IM for the minimum access package (IRG Citation2019).

Figure 7. Capacity usage and average access charges in 2017, data by IRG (Citation2019).

The figure indicates that markets with low utilization often have lower charges. Such (lower) charges can be intended to increase the demand for capacity in these markets. However, this decreases the revenues of the infrastructure manager and can therefore increase its financial deficit.

Although charging systems have such importance, EU policy only gives general guidelines on its principles, e.g. 1st packages and its recast in the SERA directive (EC Citation2001, Citation2012). Based on such principles, the minimum access package ensures access to essential components of the infrastructure. Thus, railway undertakings pay minimum access charges to the infrastructure manager based on the costs that are directly incurred as a result of the train service operation. Access to certain infrastructure facilities (e.g. freight marshaling yards and terminals, passenger stations) and additional services (e.g. ticket sales, telecommunication and traffic information) are also subject to additional charges.

Although these track access charges vary between the reviewed countries, this survey indicates that many include similar components and converge to a similar charging system, just as predicted by Crozet (Citation2004). This is illustrated in Table showing the various cost components that are included in the track access charges in the different selected countries based on their respective 2020 network statement documents.

Table 9. The track access charges including the cost components in the selected markets (X if it exits).

Table indicates that all the reviewed markets include charges for the minimum (or basic) access package covering direct costs (including administration) for the requested train paths, i.e. (marginal) costs for maintenance due to the wear and tear, costs for the needed administrative staff. In certain countries, additional (reservation) costs may also apply for processing different requests. The table also indicates that most countries include performance regimes to encourage railway undertakings to use better rolling stock and ensure certain level of service punctuality. Moreover, financial bonus (or malus) is often used to incentivize (or penalize) the use of capacity which decreases the number of unused (or canceled) allocated train paths. Proper use of capacity is further ensured through capacity allocation-related charges, e.g. timetable planning, markup costs and congestion charges.

The values of the parameters that are used to calculate the costs are mostly set by the infrastructure manager itself and sometimes with approval from the regulator, e.g. ORR in GB (ORR Citation2017). Even though the charging systems are similar, the values of the cost parameters can vary significantly from one market to the other as illustrated in Figure . For instance, countries such as SE and CZ have significantly lower values than others such as FR (Crozet Citation2018). In some countries, the minimum package may also allow access to certain facilities such as passenger stations (IRG Citation2019). This may also explain some of the differences in the access charges between the selected markets. Such differences do not only depend on the capacity utilization, but also on how each country interprets and implements the marginal cost of track use. It can also depend on whether the infrastructure manager collecting the charges is a governmental agency, nonprofit or for-profit company. In some cases, costs or benefits are simply difficult to estimate or not well estimated, e.g. noise and environmental effects (Lan and Lin Citation2005). The latter environmental effects are sometimes controlled beforehand when providing the license for the undertakings to operate in the national railways, e.g. GB (Network-Rail Citation2020).

With a few minor exceptions (e.g. DE and CH), it is uncommon that access charges are used as a conflict resolution procedure. This appears to be a severely underused opportunity as it is allowed by EU legislation; it is difficult to understand why this is not more common. One hypothesis is that it is because most railway markets were vertically integrated until recently, and it simply takes time to develop the access charges principles to solve capacity conflicts necessary in a vertically separated market. However, the survey indicates that access charges are more commonly used to incentivize the railway operators to efficiently use the allocated capacity. For instance, through differentiated track access charges such as congestion charges, i.e. charging a higher price where capacity is scare, and also through performance regimes, i.e. delay compensation.

Note that track access charges may also change from one year to the other. Major revisions can be brought to the components as well as the cost values of these components to account for the recent developments in the national railway infrastructure and operations as well as the European legislation.

4. Conclusions

All European countries aim to introduce or increase competition among operators, both for passenger and freight services. The survey shows that they adopted different reforms for market organizations, vertical separation, competition, capacity allocation and track access charges.

Although legislation requires all European countries to have a market organization with vertical separation (at least in accounting), important differences in market structure exist between the studied countries. Some (e.g. SE) have adopted complete separation, whereas others (e.g. FR) have opted for less separation with an infrastructure manager as a subsidiary of a holding/parent company, i.e. organizational separation.

The survey indicates that market competition is also different from one country to the other. In certain markets (e.g. FR), the incumbent controls almost all the market share (for passenger traffic). Markets where the incumbent has a smaller market share (e.g. SE) see most of the competition occurring on open access (mostly non-PSO passenger) lines, i.e. on-track competition. In this context, recent European legislation (i.e. 4th railway package) aims at fostering another type of competition, i.e. for-track competition, for PSO passenger services, e.g. through competitive tendering.

For the introduction of market competition to succeed, the capacity allocation process needs to be transparent and to some extent predictable, allowing prospective operators to foresee what capacity they will be allocated. It also needs to yield efficient outcomes, ensuring that the operator which is able to provide the best value for money for its customers also gets the capacity to provide its services. Few, if any, countries have capacity allocation processes that satisfy all these criteria.

As to transparency and predictability, most countries have processes where it is difficult, especially for an outsider, to understand which path requests get priority when a conflict occurs, and it is even more difficult for a potential new operator to understand how it should act in order to get the capacity it needs to provide its services. There are a few exceptions where it is relatively clear how priority is given, and even fewer with market-based procedures (e.g. auctions). But there are many more cases where capacity conflicts are resolved through various kinds of general priority criteria, where it is often difficult for an outsider to understand how they are applied. For example, several countries have priority criteria or decision rules which are not necessarily consistent or mutually exclusive, or where it is not clear in what order they take precedence.

An additional concern is that the agency responsible for capacity allocation (usually the infrastructure manager) has sometimes organizational links to the incumbent, often dominating operator. A new operator considering whether to enter the market may have reasonable concerns that this may bias the judgment of priorities in a capacity conflict in favor of the incumbent operators – especially if the capacity allocation process is informal and non-transparent (e.g. using general principles as allocation rules). As noted in this survey, markets where the capacity allocator appears to have conflicts of interest generally tend to have less competition, and incumbents often have larger market shares of the passenger and/or freight markets.

The capacity allocation process is crucial for a multi-operator railway market to function efficiently. The purpose of operator competition is to ensure, in the long run, that operators provide the services which give the best value for money to customers. For this to work, it is essential that the most efficient operator, i.e. the one providing the most attractive services from the market’s point of view, also gets priority in a capacity conflict. From our review, we can conclude that such considerations are surprisingly absent. With a few exceptions, priority criteria have at best a vague relation to consumer demand and market efficiency. A vast majority of priority criteria and decision rules instead relates to simple administrative or technical criteria, for example, that longer train paths have higher priority than short ones, or that passenger services (or high-speed trains) get priority over freight services (or slower trains). There appears to be few explicit arguments based on market efficiency or social benefits for how such criteria have been formulated. The legislation allows the use of track access charges as an instrument to resolve capacity conflicts, either by differentiating track charges to make supply meet demand, or to resolve conflicting capacity requests. However, the survey indicates that charges are rarely used as such. In addition to the minimum access package, current access charges often include (at best) performance markups that incentivize (or penalize) the railway undertakings to ensure certain level of service quality, e.g. punctuality.

Admittedly, designing capacity allocation mechanisms that are both transparent and ensure an efficient use of capacity is certainly difficult. Highly simplified, there are three different principles to resolve conflicting path requests: purely administrative criteria (such as ‘first come-first served’ or ‘passengers before freight’), methods based on some calculation of conflicting services’ social benefits, and willingness-to-pay (WTP) based methods. They all have their different advantages and drawbacks. Administrative criteria are often transparent and easy to apply, but do not guarantee a socially efficient use of capacity. Social benefits-based methods, such as cost–benefit analysis, can give efficient outcomes provided that necessary information is available, but certain information, such as ticket prices and passenger volumes, is often sensitive business information or even unknown at the time of the decision. WTP-based methods (such as auctions or scarcity pricing) do not require such detailed information about the services in a conflict, and give socially efficient resolutions of conflicts between commercial operators under certain conditions, but designing auctions or pricing schemes of railway capacity is a very complex task due to the numerous links and interactions in time and space between tracks and vehicles. Moreover, societal benefits of public service obligation traffic do not necessarily correspond to the responsible public agency’s willingness (or ability) to pay, since there is no obvious link between the societal benefits generated by commuter train services and the responsible agency’s financial resources (Ait-Ali, Eliasson et al. Citation2020a). Hence, designing transparent and efficient capacity allocation methods is certainly difficult – but it is an essential part of a deregulated railway market. The SERA directive specifies that conflicts can be resolved by ‘charges’, and that otherwise conflicts shall be resolved using ‘priority criteria’ which ‘take account of the importance of a service to society relative to any other service’. However, such ‘charges’ and ‘priority criteria’ can in practice be interpreted and designed in several different ways. There is a relatively large literature on the topic suggesting various methods, such as (to mention just a few examples) Nilsson (Citation2002), Johnson and Nash (Citation2008), Broman, Eliasson et al. (Citation2018) and Ait-Ali, Warg et al. (Citation2020b).

Opening the market for railway services to competition can in principle yield substantial social benefits, partly because operators get more incentives to become more cost-efficient and more responsive to consumer demand, partly because evolutionary selection will ensure that services are weeded out whenever production costs exceed the market’s willingness to pay. But for this to work, it is necessary that the process for resolving capacity conflicts between different operators is efficient and transparent. Our survey indicates that most countries still have some way to go in this respect. Thus, there is a need to develop and experiment with more efficient and transparent allocation procedures.

Acknowledgements

This research is part of the project Socio-economically efficient allocation of railway capacity, SamEff (Samhällsekonomiskt effektiv tilldelning av kapacitet på järnvägar) which is funded by a grant from the Swedish Transport Administration (Trafikverket). The authors are grateful to Jan-Eric Nilsson and Yves Crozet for reference recommendations as well as Russell Pittman, Steven Harrod, Roger Pyddoke and several anonymous reviewers for the valuable discussions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 […] The infrastructure manager shall perform the capacity-allocation processes. In particular, the infrastructure manager shall ensure that infrastructure capacity is allocated in a fair and non-discriminatory manner and in accordance with Union law.

2 The infrastructure charges [referred to in paragraph 3] may include a charge which reflects the scarcity of capacity of the identifiable section of the infrastructure during periods of congestion.

3 Where charges [in accordance with Article 31(4)] have not been levied or have not achieved a satisfactory result and the infrastructure has been declared to be congested, the infrastructure manager may, in addition, employ priority criteria to allocate infrastructure capacity.

4 The priority criteria shall take account of the importance of a service to society relative to anyother service which will consequently be excluded.

References

- Abbott, M., and B. Cohen. 2017. “Vertical Integration, Separation in the Rail Industry: a Survey of Empirical Studies on Efficiency.” European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research 17 (2): 207–224.

- Adif. (2020). “Network Statement 2020.”

- Ait-Ali, A., J. Eliasson, and J. Warg. 2020a. “Are Commuter Train Timetables Consistent With Passengers’ Valuations of Waiting Times and In-Vehicle Crowding”? VTI Working Papers, Swedish National Road & Transport Research Institute.

- Ait-Ali, A., J. Warg, and J. Eliasson. 2020b. “Pricing Commercial Train Path Requests Based on Societal Costs.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 132: 452–464.

- Ait Ali, A. 2020. Methods for Capacity Allocation in Deregulated Railway Markets Doctoral thesis, comprehensive summary, Linköping University Electronic Press.

- Alexandersson, G., and K. Rigas. 2013. “Rail Liberalisation in Sweden. Policy Development in a European Context.” Research in Transportation Business & Management 6: 88–98.

- Asmild, M., T. Holvad, J. L. Hougaard, and D. Kronborg. 2009. “Railway Reforms: do They Influence Operating Efficiency?” Transportation 36 (5): 617–638.

- ÖBB-Infrastruktur. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- Bouf, D., Y. Crozet, and J. Leveque. 2005. “Vertical Separation, Disputes Resolution and Competition in Railway Industry.” Thredbo 9, 9th conference on competition and ownership in land transport, 5-9 september 2005, Lisbonne., Lisbon Lisbon Technical University.

- Broman, E., J. Eliasson, and M. Aronsson. 2018. “A Mixed Method for Railway Capacity Allocation.” 21st Meeting of the Euro Working Group on Transportation 2018. Braunschweig.

- Crozet, Y. 2004. “European Railway Infrastructure: Towards a Convergence of Infrastructure Charging?” International Journal of Transport Management 2 (1): 5–15.

- Crozet, Y. 2016a. “Introducing Competition in the European Rail Sector.” Discussion Paper prepared for the Roundtable on Assessing regulatory changes in the transport sector.

- Crozet, Y. 2016b. Liberalisation of Passenger Rail Services - France.

- Crozet, Y. 2018. Case Study – France: Logic and Limits of Full Cost Coverage. Track access charges: reconciling conflicting objectives. CERRE, CERRE & University of Lyon (LAET).

- Crozet, Y., J. Haucap, B. Pagel, A. Musso, C. Piccioni, E. Voorde, T. Vanelslander, and A. Woodburn. 2014. Development of Rail Freight in Europe: What Regulation Can and Cannot Do - Policy Paper.

- Crozet, Y., C. Nash, and J. Preston. 2012. “Beyond the Quiet Life of a Natural Monopoly: Regulatory Challenges Ahead For Europe’s Rail Sector.” Policy paper, CERRE, Brussels, December 24.

- DB-Netze. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- EC. 1991. Council Directive 91/440/EEC of 29 July 1991 on the Development of the Community's railways, European Commission.

- EC. 2001. Directive 2001/14/EC on the Allocation Of Railway Infrastructure Capacity and the Levying of Charges for the Use of Railway Infrastructure And Safety Certification, EU Parliament.

- EC. 2012. Directive 2012/34/EU on Establishing a Single European railway area, EU Parliament.

- EC. 2016a. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/545 of 7 April 2016 on Procedures and Criteria Concerning Framework Agreements for the Allocation of Rail Infrastructure Capacity, European Commission.

- EC. 2016b. Fourth Railway Package of 2016, European Commission.

- ECMT. 2005. Railway Reform and Charges for the Use of Infrastructure, European Conference of Ministers of Transport.

- Friebel, G., M. Ivaldi, and C. Vibes. 2010. “Railway (De)Regulation: A European Efficiency Comparison.” Economica 77 (305): 77–91.

- Gibson, S. 2003. “Allocation of Capacity in the Rail Industry.” Utilities Policy 11 (1): 39–42.

- Gilbo, E. P. 1993. “Airport Capacity: Representation, Estimation, Optimization.” IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 1 (3): 144–154.

- Hansson, L., and J. E. Nilsson. 1991. “A new Swedish Railroad Policy: Separation of Infrastructure and Traffic Production.” Transportation Research Part a-Policy and Practice 25 (4): 153–159.

- Infrabel. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- IRG. 2019. Seventh Annual Market Monitoring Working Document, Independent regulators’ group rail.

- Jensen, A., and P. Stelling. 2007. “Economic Impacts of Swedish Railway Deregulation: A Longitudinal Study.” Transportation Research Part E-Logistics and Transportation Review 43 (5): 516–534.

- Johnson, D., and C. Nash. 2008. “Charging for Scarce Rail Capacity in Britain: a Case Study.” Review of Network Economics 7: 1.

- Klein, M. 1999. Competition in Network Industries.

- Kozan, E., and R. Burdett. 2005. “A Railway Capacity Determination Model and Rail Access Charging Methodologies.” Transportation Planning and Technology 28 (1): 27–45.

- Lan, L. W., and E. T. J. Lin. 2005. “Measuring Railway Performance with Adjustment of Environmental Effects, Data Noise and Slacks.” Transportmetrica 1 (2): 161–189.

- Laurino, A., F. Ramella, and P. Beria. 2015. “The Economic Regulation of Railway Networks: A Worldwide Survey.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 77: 202–212.

- Link, H. 2004. “Rail Infrastructure Charging and on-Track Competition in Germany.” International Journal of Transport Management 2 (1): 17–27.

- Link, H. 2016. Liberalisation of Passenger Rail Services - Germany.

- Link, H. 2018. Case Study – Germany. Track access charges: reconciling conflicting objectives. CERRE, German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin).

- Ludvigsen, J. 2009. “Liberalisation of Rail Freight Markets in Central and South-Eastern Europe: What the European Commission Can Do to Facilitate Rail Market Opening.” European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research 9 (1): 46–62. doi:10.18757/ejtir.2009.9.1.3285.

- Merkert, R. 2012. “An Empirical Study on the Transaction Sector Within Rail Firms.” Transportmetrica 8 (1): 1–16.

- Monami, E. 2000. “European Passenger Rail Reforms: A Comparative Assessment of the Emerging Models.” Transport Reviews 20 (1): 91–112.

- Murillo-Hoyos, J., M. Volovski, and S. Labi. 2016. “Rolling Stock Purchase Cost for Rail and Road Public Transportation: Random-Parameter Modelling and Marginal Effect Analysis.” Transportmetrica A: Transport Science 12 (5): 436–457.

- Nash, C. 2008. “Passenger Railway Reform in the Last 20 Years - European Experience Reconsidered.” Reforms in Public Transport 22: 61–70.

- Nash, C., Y. Crozet, H. Link, J.-E. Nilsson, and A. Smith. 2016. Liberalisation of Passenger Rail Services - Project Report.

- Nash, C., Y. Crozet, H. Link, J.-E. Nilsson, and A. Smith. 2018. Track Access Charges: Reconciling Conflicting Objectives - Project Report. CERRE, CERRE.

- Nash, C., J. E. Nilsson, and H. Link. 2013. “Comparing Three Models for Introduction of Competition Into Railways.” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 47: 191–206.

- Nash, C. A., A. S. J. Smith, D. van de Velde, F. Mizutani, and S. Uranishi. 2014. “Structural Reforms in the Railways: Incentive Misalignment and Cost Implications.” Research in Transportation Economics 48: 16–23.

- Network-Rail. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- Nilsson, J.-E. 2002. “Towards a Welfare Enhancing Process to Manage Railway Infrastructure Access.” Transportation Research Part A 36 (5): 419–436.

- Nilsson, J.-E. 2016. Liberalisation of passenger rail services - Sweden.

- Nilsson, J. E. 2018. “Case Study – Sweden: Track Access Charges and the Implementation of the SERA directive - promoting efficient use of railway infrastructure or not?” Track access charges: reconciling conflicting objectives. CERRE, VTI Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute.

- OECD. 2005. Structural Reform in the Rail Industry. Competition Policy Roundtables.

- OECD. 2013. Recent Developments in Rail Transportation Services. Competition Policy Roundtables.

- ORR. 2017. “Track access guidance Office of Rail and Road.” http://www.orr.gov.uk/rail/access-to-the-network/track-access/guidance.

- Pena-Alcaraz, M. M. T. 2015. “Analysis of Capacity Pricing and Allocation Mechanisms in Shared Railway Systems.” PhD, MIT - Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Perennes, P. 2014. “Use of Combinatorial Auctions in the Railway Industry: Can the “Invisible Hand” Draw the Railway Timetable?” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 67: 175–187.

- Perez Herrero, M. 2016. “Rail Capacity Constraints: An Economic Approach.” PhD, Université Lumière Lyon 2.

- ProRail. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- RFI. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- SBB. 2020. Network Statement 2020.

- SŽDC. 2020. “Network statement 2020.”.

- Smith, A. 2016. Liberalisation of Passenger Rail Services - Britain.

- Smith, A., and C. Nash. 2018. Case Study – Great Britain. Track Access Charges: Reconciling Conflicting Objectives. CERRE, CERRE & University of Leeds.

- Smoliner, M. S., S. Walter, and S. Marschnig. 2018. “Optimal Coordination of Timetable and Infrastructure Development in a Liberalised Railway Market.” Journal of Management and Financial Sciences 33: 97–115.

- SNCF-Réseau. 2020. Network statement 2020.

- Stojadinović, N., B. Bošković, D. Trifunović, and S. Janković. 2019. “Train Path Congestion Management: Using Hybrid Auctions for Decentralized Railway Capacity Allocation.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 129: 123–139.

- Talebian, A., B. Zou, and A. Peivandi. 2018. “Capacity Allocation in Vertically Integrated Rail Systems: A Bargaining Approach.” Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 107: 167–191.

- Tomeš, Z., M. Kvizda, M. Jandová, and V. Rederer. 2016. “Open Access Passenger Rail Competition in the Czech Republic.” Transport Policy 47: 203–211.

- Tomeš, Z., M. Kvizda, T. Nigrin, and D. Seidenglanz. 2014. “Competition in the Railway Passenger Market in the Czech Republic.” Research in Transportation Economics 48: 270–276.

- Trafikanalys. 2014. Railway in Sweden and Japan - a comparative study.

- Trafikverket. 2020a. Järnvägsnätsbeskrivning 2020 - Prioriteringskriterier, Swedish Transport Administration.

- Trafikverket. 2020b. Network Statement 2020, Swedish Transport Administration.

- UIC. 2009. Noise Differentiated Track Access Charges, International Union of Railways.

- Van de Velde, D., C. Nash, A. Smith, F. Mizutani, S. Uranishi, M. Lijesen, and F. Zschoche. 2012. “Economic effects of Vertical Separation in the Railway Sector.” Report CER and Inno-V Amsterdam.

- Yeung, R. 2008. Moving Millions: The Commercial Success and Political Controversies of Hong Kong's Railway. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.