ABSTRACT

During the summer of 2020, the United Kingdom, like many countries in Europe, witnessed a strong upsurge in mobilisation for Black Lives. Inspired by protests in the United States following the murder of George Floyd, British demonstrators took to the streets in order to make their voices heard. Peculiarly, they lacked something which we generally associate with substantial episodes of mobilisation: a conducive political opportunity structure. Rather, the political context present in the United Kingdom was generally prohibitive of movement success. This article examines the case of the UK’s 2020 protests to consider how mobilisation can be stimulated despite a palpably politically inopportune context. It draws on contemporary open-source data to characterise and detail the prohibitive structure of political opportunities in the UK domestic setting before laying out three factors that can nonetheless help stimulate mobilisation in such circumstances: quotidian disruption, frame diffusion, and remaindered resources.

Introduction

The summer of 2020 saw hundreds of thousands of Britons join ‘Black Lives Matter’ mobilizations. Sparked by protests in the United States, the UK’s 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations constituted the country’s first major protests of the COVID-19 pandemic. After a spate of solidarity actions targeted principally against the United States government in late May, an anglicised expression of the US movement’s demands gathered pace in the month of June, creating the basis for a rejuvenated protest movement that remained active long after.

Britain’s 2020 Black Lives Matter mobilizations exhibit a peculiar characteristic: the absence – in the UK at least – of a discernible ‘political opportunity’ on which the movement might have been able to capitalise (McAdam, Citation1996; Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2006; Wahlstrom & Peterson, Citation2006). This case of mobilisation without opportunity invites us to reflect on whether a political opportunity is indeed a necessary condition for mobilisation and, moreover, what configuration of factors might be at least partly sufficient for mobilisation to take place in its absence. Accordingly, this article investigates the UK’s 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, contextualising their emergence, evaluating the scope of political opportunities, and detailing other factors which nonetheless facilitated the mobilisation process. It shows that despite the lack of a conducive political opportunity structure, three factors nonetheless encouraged substantial mobilisation: quotidian disruption arising from the COVID-19 pandemic; cross-national frame diffusion from movements in the United States; and the remaindering of excess movement resources.

In order to develop an analysis of the UK Black Lives Matter case, with particular attention to the structural and organisational context of protest mobilisation, this article draws on open source data. As opposed to closed-source methods such as qualitative interviews or private archival research, open source research (sometimes termed ‘open-source investigations’, or – in humanitarian and military contexts – ‘Open Source Intelligence’) draws on non-privileged information potentially accessible to anyone, such as broadcast media, public online discussions, video footage, open repositories, the proceedings of public meetings, government data, and commercial or organisational reports (McPherson et al., Citation2020; Steele, Citation2007). This wide range of data sources provides researchers with the capacity to make informed causal inferences while reducing the need to collect sensitive personal data or procure rare archival documents. It is thus a highly propitious method for the study of novel and emergent cases in informationally rich settings. A key strength of this method is that ‘anyone – not just journalists or researchers at select institutions – can contribute to investigations’ into a particular phenomenon, allowing research findings to be queried, refuted or iterated upon within a common informational setting (Fiorella, Citation2021).

In this instance, sources spanned television news and newspaper reports, live footage recorded and shared publicly by participants, government data and legal documents, reports by international bodies and public investigations by non-governmental organisations. As is common with other forms of data-rich research (such as archival research or ethnography), a wider variety of sources (in this case, approximately 100 further individual sources of data) than those cited in text were consulted during the research process. Those sources referenced in text are intended to point readers to evidence that establishes little-known matters of fact or evinces an important sense of context. These are cited in a standard format in the reference list.

The UK’s Black Lives summer

On 31 May 2020, two young students – Aima and Tash – organised their first ever protest. The duo responded to the murder of George Floyd – a Black man from Minneapolis – by taking to Instagram and Twitter and proposing that Londoners march to the American embassy (Baah, Citation2020). Despite the fact that the pair had no prior experience organising protests, thousands of people turned out in support, marking the UK’s first major racial justice protest since the beginning of the COVID-19 lockdown. Though they might have been the most successful, Aima and Tash weren’t the only British organisers mobilising in response to George Floyd’s killing. Seeking to exhibit solidarity with American protesters in Minneapolis and elsewhere, a number of activists and organised groups had planned protests over the last weekend of May. These included long-running racial justice groups, neophyte activists in similar situations to Aima and Tash, and a smattering of formally and informally constituted left-wing groups (BBC, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Mohdin, Citation2020). At this early stage in the protests – which would go on to reportedly constitute the UK’s largest anti-racist protest since the abolition of slavery (Mohdin et al., Citation2020) – energy and messaging was focused primarily on demonstrating solidarity with struggles in the United States. The US embassy in London was a regular target, and signs and slogans conveyed messages such as ‘Your pain is our pain’, ‘Justice for George Floyd’, and Floyd’s dying words: ‘I can’t breathe’. Protesters primarily chanted names of Black Americans killed by the police, though British names were occasionally mentioned (albeit with less recognition from the crowd) (Made, Citation2020; Media, Citation2020).

By the end of May, major organised groups such as Stand Up to Racism, Unite Against Fascism and Black Lives Matter UK began to throw their weight behind further mobilising efforts. Many of these groups had not been engaged in sustained large-scale protest against anti-Black racism for quite some time, with the last major explicitly ‘Black Lives’ oriented protests having taken place as far back as 2016. In addition to these groups, the youth activists behind the May protests formed their own collective association: ‘All Black Lives’ (Mohdin et al., Citation2020). This spectrum of established groups, neophyte organisers and the various networks in-between began coordinating a new phase of mobilisation, moving beyond events in the United States to advance the cause of Black lives in the United Kingdom. As they did so, they were met with an enormous amount of energy, enthusiasm, and commitment from young Brits who – amid the COVID-19 lockdown – had more time than usual to commit to other activities, and who had been strongly affected by recent events. An approximate agenda also emerged, comprising three central goals: an overhaul of British policing by reform, divestment or even abolition; an end to the glorification of slaveholders and prominent racists; and a need to undo serious structural and institutional racism in the UK (see, e.g. McIntosh, Citation2020).

Drawing upon this surge energy protests took place practically every single day in the early weeks of June, beginning on 3 June, in London’s Hyde Park. The day attracted large number of ordinary people alongside organised groups (Dugomore, Citation2020). There was also a distinct change of focus underway, with the onus shifting from George Floyd’s murder to the case of Belly Mujinga – a Black woman who, following a racist incident in which she was spat on, was hospitalised with COVID-19 and died (PANews, Citation2021). Chants and speeches raised the names of other Black British victims of police and racist violence such as Mark Duggan and Stephen Lawrence.

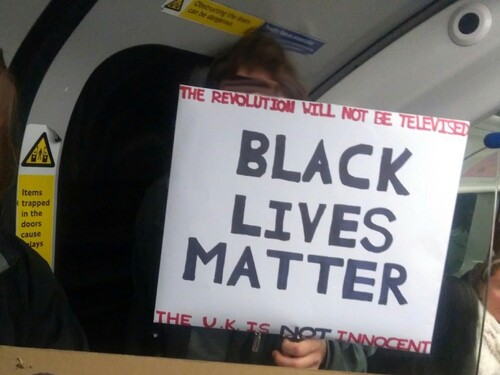

The arrival of the weekend on Saturday, 6 June hailed even larger protests. While social distancing had been attempted with some success at prior demonstrations, the scope of attendance that day made it practically impossible. The planned location – Parliament Square – was far too small to fit the enormous surge of attendees, and so an impromptu march around Westminster was conducted in order to buy new arrivals some (literal) breathing room.Footnote1 A vast crowd, holding signs made with cardboard boxes and felt-tip pens, descended upon the seat of government. Though George Floyd’s name and cause still featured, much on display that day was decidedly British in focus. Signs featuring slogans such as ‘Racist UK birthed Racist America’, ‘The UK is not Innocent’, and ‘Fuck the Government and Fuck Boris [Johnson]’, replaced the America-focused placards from the prior week, and prominent statues and government buildings were defaced with the movement’s acronym – BLM ().

Figure 1. A protester in Parliament Square on 6 June shows off a hand-made sign listing the names of UK victims of police and racist violence in parallel to those in the US. Author’s photo.

Figure 2. Defaced statue in Parliament Square on 6 June, bearing the acronyms ‘BLM' and ‘ACAB'. Author’s photo.

Figure 3. A protest sign reading ‘Fuck the Government and Fuck Boris’ [Johnson], at the feet of protesters preparing to go home for the day. Author’s photo.

![Figure 3. A protest sign reading ‘Fuck the Government and Fuck Boris’ [Johnson], at the feet of protesters preparing to go home for the day. Author’s photo.](/cms/asset/8dc6bd99-a703-439f-a73d-5702b33d48c4/recp_a_2239328_f0003_oc.jpg)

Figure 4. A protest sign reading ‘THE REVOLUTION WILL NOT BE TELEVISED. BLACK LIVES MATTER. THE U.K. IS NOT INNOCENT', held by a protester on a London Underground train. Author’s photo.

Figure 5. A protest sign illustrating a silhouette of a pregnant woman superimposed with a British flag. In her womb, there is a silhouette of a fetus, superimposed with an American Flag. The sign reads ‘RACIST UK BIRTHED RACIST AMERICA’.

Alongside Saturday’s London protest, tens of thousands demonstrated in cities across the UK. These protests exhibited a similarly domestic shift in their agenda. In Glasgow, activists replaced street signs named after slave traders with the names of Black radicals and victims of police violence. In Bristol, protesters toppled a statue honouring Edward Colston – a prominent seventeenth century slaver – and threw it into the harbour. After this weekend peak, substantial protests continued for a further two weeks, and consistent movement activity ensued for another year-and-a-half.

Continuing the process of contention initiated during the UK’s May/June protests would prove a challenge. Despite plentiful participants, enthusiastic activists and available resources, the UK’s political opportunity structure heralded very little room for institutional political change. Rather, amid a profoundly politically inopportune context, countermovement activity surged. The UK government worked with the National Police Chiefs Council to put in place a raft of new powers enabling the use of greater force against protesters, arguing that the current status quo was ‘too readily in favour of protesters’, explicitly citing ‘the BLM protests’ (Home Office, Citation2021a). On the broader question of structural and institutional racism, the government commissioned a report that claimed institutional racism did not exist in the UK and instead called for more attention to the struggles of ‘White British’ groups (Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, Citation2021). It was to this backdrop that highly visible right-wing counter-protests and hate crimes surged, the latter soaring by 12%, reaching their highest ever level (Home Office, Citation2021b). This severe backlash left the movement – and Black Britons – ‘in a worse position … than we were prior to the eruption and protests in the first place’, Kehinde Andrews, an activist scholar involved in the movement recounted in a review of its progress in March 2021 (Agarwal et al., Citation2021). ‘We’re now in a position where we’re again having to justify whether racism exists … we’ve gone backwards’.

The presence and absence of political opportunities

Scholars have long discussed how ‘political opportunities’ structure the activities of social movements and other contentious political actors (Giugni, Citation2009; McAdam, Citation1996; Tarrow, Citation1994). The term ‘political opportunity’ refers – broadly speaking – to those features of a particular case that advantage a movement’s attempts to pursue changes to the political system. Some of these might be long-standing, others might be temporary, and are of course defined relative to the contentious political actor in question. As Tilly and Tarrow (Citation2006, p. 75) note in their review of political opportunity approaches, opportunities are understood to be a central determinant of movement activity, shaping ‘the costs and benefits of collective claim making, the feasibility of various programs and the consequences of different [contentious] performances’. First of all, however, they ‘shape the ease or difficulty of mobilization’.

The question of exactly how the scope of political opportunities might be delimited has been subject to quite some scholarly back-and-forth over the years, especially during the turn away from structural approaches to social movements seen in the 1990s (Gamson & Meyer, Citation1996; Goodwin & Jasper, Citation1999). Amid this period of dispute there arose a very popular ‘consensual definition’ advanced by Doug McAdam (Citation1996, p. 27) that – though not without its own subsequent variants (e.g. Tilly & Tarrow, Citation2006; Wahlstrom & Peterson, Citation2006) and adaptations (e.g. Kay, Citation2005; Van der Heijden, Citation2006Footnote2) – is still widely in use by scholars today.Footnote3

McAdam’s (Citation1996, p. 27) approach outlines four key dimensions of political opportunity, first among which is ‘the relative openness or closure of the institutionalized political system’ in a given state. This refers to the formal, structured opportunities for a movement to flourish, and encompasses matters such as how the state or polity is currently structured and what meaningful points of access to power or power-holders are available. These factors may fluctuate depending on the government of the day, system-reforms, temporary laws, and the alignment of institutionally ordained arbiters (including – in some circumstances – publics).

Alongside the role played by the institutionalised political system, political opportunities often arise from the relationships between power-holders and others that originate outside of highly formalised institutional contexts. These power relations constitute ‘the stability or instability of that broad set of elite alignments that typically undergird a polity’, and encompass the way in which political parties, politicians, newspapers, and public bodies serve to represent particular groups or ideologies, providing (or ruling-out) avenues of movement or countermovement influence. Relatedly, a third element of political opportunity comprises the more general ‘presence or absence of elite allies’, who might be able to aid a movement by disrupting power relations among the elites. These may take the form of opposition politicians, influential celebrities, and well-positioned economic elites who can use their position to assist a movement. Finally, a fourth – highly important – element of political opportunity structure comprises ‘the state’s capacity and propensity for repression’, by formal or informal means. This may range from anti-protest laws and temporary powers given to police forces and intelligence agencies, right the way to informal violence from state-aligned forces or armed repression by regime troops.

McAdam’s four dimensions of political opportunity provide a useful starting point for imagining what its absence might look like: (1) a relatively closed-off political system in which (2) existing power relations remain stable and (3) elites unsympathetic, and where (4) the state is willing and able to shut down contentious political activity. As we shall see, such a characterisation accurately depicts the state of political opportunities during the UK’s 2020 Black Lives Matter movement.

The scope of political opportunities in the 2020 United Kingdom

Periods of inopportune contention (i.e. contention in the absence of political opportunity) are characterised by hostile political systems, elite alignments, absent allies and a highly repressive state. As we shall see, the summer of 2020 was one such period of inopportune contention. The UK political system was substantially closed off to the movement and its associated demands, a status quo supported by highly stable alignments within the ruling party and political elites. Moreover, the movement lacked politically efficacious elite allies of its own, and supportive politicians were wavering or inconsistent in their commitment to the cause. Mobilisation also occurred during a period of unprecedented repressive power afforded to UK government and police forces, both of which possessed even greater capacity for further repression, as demonstrated by a subsequent upsurge in anti-Black Lives Matter repression in the aftermath of mobilisation.

A closed political system

To say that the UK’s institutionalised political system was unreceptive to Black Lives Matter protest would be an understatement. The UK’s Black population stands at approximately 4% of all Britons (compared with – for example – 13.6% in the US, and 8.5% in France) and – being almost entirely concentrated in urban constituencies that seldom change hands – has the misfortune of exerting minimal influence on the formation of government (Saggar, Citation2016). Telling of this minimal influence was the fact the UK Prime Minister at the time of the protests, Boris Johnson, enjoyed a certain domestic infamy for his use of racist discourse. Johnson has referred to Black and African peoples variably as ‘aids-ridden’, ‘picanninnies’, ‘tribal warriors … [with] watermelon smiles’, and prone to ‘orgies of cannibalism and chief-killing’ (Attewill, Citation2006; Busari, Citation2019). Prominent conservatives and cabinet members framed the Black Lives Matter movement as comprised of ‘mobs’ and ‘thugs’, underpinned by a ‘Neo Marxist organisation that wants to overthrow capitalism and get rid of the Police, … not a force for good’ (Patel, Citation2020; Stone, Citation2020). At the time of the 2020 protests, the Johnson government held an unshakeable majority in parliament enabling executive dominance at the level of what had been termed an ‘elected dictatorship’ (Rogers, Citation2022). Tory government was set to persist until the next general election, some four years after the 2020 protests.

Moreover, public opinion was substantially aligned against the movement, a factor which made political influence or access difficult within the context of an electoral democratic system. Even in remote areas of the country entirely untouched by protest, a narrative highly hostile to the movement found clear public expression. “BLM protests in England have stirred up the worst racial tension seen in a generation, while a minority see racism in every scenario. [The] Government … has said Britain is one of the best countries in the world to be a black person”, one letter published in The Herald (Citation2021) declared. Such an opinion was similarly reflected in the public mainstream. Only 17% of Britons polled in October 2020 disagreed with the notion that the Black Lives Matter movement was responsible for an increase in racial tensions. One quarter of those polled alleged that the movement was in fact a Marxist organisation. Among supporters of the ruling Conservative party, these figures were 6% and 48% respectively (Opinium, Citation2020).

This closure of the UK political system to movement demands was a serious hurdle for the Black Lives Matter movement. Distant horizons for electoral reform, a broadly hostile voting public, and well-entrenched incumbents with a racist pedigree meant that those mobilising in 2020 very evidently faced a system that would be unreceptive to their demands, but was there a chance this system might be successfully disrupted?

Unfavourable power relations

One fruitful route of potential disruption to a closed-off political system would be exploiting unstable relations between elements of that particular system, or structurally entrenched relations between movement protagonists and system insiders. Here too the UK’s Black Lives Matter movement faced an inopportune context.

After a decade of Conservative rule, previously apolitical public bodies intended to give voice to civil causes and marginalised racial groups had been reoriented in alignment with the ruling party. Perhaps the most formerly promising avenue through which Black Lives Matter protesters’ concerns might be heard was the Equalities and Human Rights Commission. However, this institutional pathway had closed off due to a tightening of relations between the institution and the UK’s Conservative government. By the summer of 2020 (July), the organisation had no Black or Muslim directors at all. Two directors (one from each category) who had their employment terminated concluded that ‘race equality generally was put on the back burner’, and that they had been relieved of their roles because they had been too vocal on issues of racism. Meanwhile, directors whose services were retained by the body were found to have been clandestine donors to the Conservative party. Accordingly, the organisation’s former legal director has since concluded that it ‘No longer meets the conditions for UN accreditation. It is not independent. It does not support human rights for everyone’, (Skwawkbox, Citation2020). Other whistleblowers from within the organisation have alleged that it has switched from challenging racism to a process of ‘racial gaslighting’, in which claims of racism are outright denied rather than investigated. As one whistleblower’s email to their colleagues read: ‘Our senior leadership in England has helped dismantle the backbone of the commission – its integrity and authenticity – when it comes to race'. The commission itself was beset by the very ‘structural and institutional racism’ it was denying the existence of (Siddique, Citation2021).

Another potential avenue through which the UK Black Lives Matter movement might have been able to advance its agenda was the country’s long-standing major opposition party, the Labour Party. Labour was the historic party of choice for Black Britons and had constitutionally enshrined representation for its Black and minority ethnic members at the level of policymaking and executive governance (BAME Labour, Citation2021). Unfortunately, the party’s leader – Sir Keir Starmer, QC – presided over a deterioration of the party’s relationship with its left-wing Black supporters, meaning that by the summer of 2020 Black members were leaving the party, which had failed to address a string of racist incidents by senior officials (White, Citation2020). Moreover, Starmer was the former UK Director of Public Prosecutions, and an especially close ally of the country’s most powerful police official at the time – Metropolitan Police Commissioner Dame Cressida Dick. Thus, the party’s leadership had not only weakened the party’s traditional ties to the UK Black community but was actively aligned with one of the targets of the Black Lives Matter movement’s claims: the senior leadership of Britain’s police forces.

The creation of stable alignments between anti-racism watchdogs and the Conservative party, combined with a destabilisation of the traditional alignments between the Labour Party and Black British communities meant that the UK Black Lives Matter movement was very poorly served by the structure of power relations. Moreover – as we shall see – the most sympathetic elites who supported the movement lacked sizeable political power, while those with more political influence fell back on pre-existing alignments rather than supporting the movement’s aims.

Limited elite allies

Black Lives Matter protesters in the UK possessed only a limited contingent of quasi-elite allies. Not only are there disproportionately few Black (and minority ethnic) people in the UK elite (which, as of 2017, stood at 97% white), but structural, institutional and systemic forms of discrimination also serve to deny people of African descent access to elite spaces and influence on public and private institutions (Duncan & Holder, Citation2017; United Nations, Citation2023). Rather than full-fledged elites, these movement’s quasi-elite allies predominantly constituted charismatic and attention-grabbing but not politically powerful figures situated on the periphery of cultural and political spheres. In neither case did these allies wield sufficient political power to implement prospective demands from the movement, or to considerably shape public opinion beyond their extant audiences.

The movement’s most vocal potent allies came from among the UK’s pop-culture elites, many of whom were from ethnic minority backgrounds. Prominent celebrities such as actor John Boyega, footballer Marcus Rashford, rappers Stormzy and Akala, as well as Meghan, Duchess of Sussex (née Markle) vocally supported the movement, using their cultural capital to popularise the cause. Rashford became particularly involved in the movement, leading his fellow England players in anti-racist protest prior to every single football match of the 2020 European championship. These figures helped galvanise support among their supporters, professional colleagues and other celebrities (Venn, Citation2020). While there is no reason to suggest that the impact of celebrity allies was inconsiderable, their position in the UK elite was bounded by institutional, racial, and political factors which left them unable to exercise any decisive influence over mainstream print and broadcast media outlets and everyday cultural products (Hammond et al., Citation2021).

A second set of allies were opposition politicians, who expressed wavering and inconsistent alignment with the movement at the outset of protest in May/June, and whose allegiance further dissipated over time. The UK’s major opposition party – the Labour Party – initially expressed lukewarm gestures of support with the movement, including the party leader (Keir Starmer) and deputy leader (Angela Rayner) participating in a posed photo opportunity in which they ‘took the knee’ (an anti-racist gesture popularised by protests in the United States) not in explicit support of the movement, but rather caveated as expressing solidarity ‘with all those opposing anti-Black racism’. The Scottish National Party (the third largest party in the British parliament, and the governing party in Scotland), issued statements in support of the movement, but simultaneously urged the public not to attend protests – citing public health concerns (Salmond, Citation2020).

The UK political opposition’s initial lukewarm political support was the fullest extent of elite allegiance the movement would attract among the political class. Within a month, Labour’s caveated support had descended into outright critique, with Starmer decrying movement demands for police reform as ‘just nonsense’, and relegated public discontent to ‘a moment across the world’, and declaring that it was ‘a shame it’s getting tangled up’ with organised Black Lives Matter groups (BBC, Citation2020d). Further pivoting against the movement, and falling back on his aforementioned strong relationship with UK police elites, Starmer declared: ‘Nobody should be saying anything about defunding the police. I would have no truck with that … my support for the police is very very strong’ (Muir, Citation2020).

Heightened state capacity for repression

Atop all the other unfavourable aspects of the UK’s political opportunity structures, the summer of 2020 was an especially vulnerable moment for any protest movement. The period constituted a high-point in the repressive capacity of the British state. Coronavirus lockdown laws permitted police to use force to disperse any gathering of more than six people, as well as to arrest anyone deemed to have participated in such a gathering.Footnote4 Even before the protests, these powers were being used to disproportionately target black and minority ethnic Britons by an estimated factor of 90% (Gidda, Citation2020). This forms part of a long history of structural and institutional racism that has been widely assessed to have been endemic in British policing and across public life (Elliot-Cooper, Citation2021; Joseph-Salisbury et al., Citation2020).

Heightened repressive powers were readily employed against participants in the UK Black Lives Matter movement, both during and after the peak of protest activity. Moreover, police wielded these powers – in combination with existing repressive measures – in ways that have been understood to go well beyond the limits of the law. Expert legal opinion found that in June 2020 police were liable to use their new powers so broadly with regard to Black Lives Matter protest that they would breach Human Rights laws (Chada, Citation2020). In some parts of the UK, police forces used charges of ‘aiding and abetting’ breaches of the coronavirus rules to pre-emptively target protest stewards and organisers. In London, police readily brutalised and arrested protesters, using legislation designed to prohibit antisocial behaviour and breaches of the peace to instead target protesters who had not engaged in either activity (Network for Police Monitoring, Citation2020).

The surge of repression directed against protesters in the summer of 2020 pushed already enriched anti-protest laws to or even beyond their limits. However, this initial police repression was only the opening salvo in a more sustained campaign against the movement. State repression has continued for a full three years after the protests, up to and including the period during which this article has been written. In February of 2022, the UK government instituted a ban on staff expressing support for Black Lives Matter in UK schools, and covert police operations designed to compromise Black Lives Matter groups are reported to have resulted in their collapse, intimidating activists and potential supporters (Department for Education, Citation2021; Evans & Morris, Citation2022). In March, the government passed anti-protest laws with an unprecedented level of harshness. The ‘Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill’ allowed government ministers to ban any demonstrations they anticipate may be ‘seriously disruptive’ – a term used to refer to anything which may cause undue noise or annoyance (McGuiness, Citation2021). Powers have since been strengthened with the 2023 Public Order Act, which has created an infrastructure for the repression of a wider variety of political causes. Participants in demonstrations judged to have engaged in disruptive behaviour (such as undue noise, obstructing a roadway, or locking oneself to another person or object) can now be punished with substantial prison sentences. Police are allowed to stop and search individuals and vehicles suspected of carrying materials for use in protest, and are allowed to ban individuals (even those not convicted of a crime) from participating in a protest or encouraging others to do so online (Taylor, Citation2022).

Mobilising without opportunity

In view of the striking absence of a conducive political opportunity structure, one may rightly wonder how it came to be that the UK’s Black Lives Matter protesters mobilised quite so dramatically. Other advances in the study of contentious politics – both intersecting with and diverging from the political opportunity literature – help explain some of the factors which may have contributed to mobilisation without opportunity in the British case. Namely, I draw here on work and ideas concerning quotidian disruption, biographical availability, frame diffusion and resource mobilisation. By paying attention to these areas of contentious politics we can come to better understand atypical instances of movement activity, such as inopportune mobilisation.

Quotidian disruption

One important backdrop to the study of mobilisation is the fact that people’s everyday routines are – at least in the context of advanced capitalist societies – predominantly prohibitive of participation in contentious political action. The various diurnal patterns into which people fall – going to and from work, seeing friends and caring for family, engaging in commercial leisure activities – serve to structure their time such that there is usually a relatively high opportunity cost for movement participation. Thus, participants in social movements are often those with the greatest ‘biographical availability’ (McAdam, Citation1986; see also, more recently, Hart, Citation2021): a freedom from substantial constraints that might otherwise inhibit participation. But one’s availability for participation is not fixed. Certain circumstances can produce disruptions to quotidian routines and constraints which may – in turn – reduce the cost of participating in contention or eliminate competing alternatives (Pinckney & Rivers, Citation2021; Snow et al., Citation1998).

The summer of 2020 was one such period of disruption. Until 13 May 2020, the UK’s Coronavirus ‘lockdown’ restrictions prohibited socialising with anyone outside one’s own household – even outdoors. As of 1 June – after the start of the summer protests – this was modestly loosened to a maximum of six people (still outdoors only). In major cities, a sizeable bulk of the population were working from home – some 57.2% in London (Cameron, Citation2020). Many major social leisure activities and entertainment/hospitality venues were either prohibited or closed-down, with the exception of dining. These combined constraints on activity created a great deal of biographical availability among certain segments of the population. The scope of one’s pre-scheduled social engagements was strictly limited by pandemic restrictions, while commuting hours were freed-up by work-from-home practices. Moreover, a considerable portion of the working population were furloughed – approximately 1/3 of employees, rising to 2/3 in the youngest age categories, causing considerable disruption to otherwise congested daily routines (HM Revenue & Customs, Citation2020). As for young people in education, schools and university campuses remained closed throughout the month of May and much of June, further heightening biographical availability among the youth who made up the visible bulk of participants in the May and June protests (BBC, Citation2020c).

While quotidian disruptions such as those occurring during the UK’s COVID-19 lockdown may lead to an increase in protest by fostering increased biographical availability, quotidian disruption alone is not enough to motivate people to protest. After all, one may choose to respond to a disruption in diurnal routines and obligations in a plethora of different ways. Rather, we need to turn to another element of contentious politics to help understand why those with the means to protest chose to pursue that activity rather than staying at home or doing something else, as well as why those with the means to organise or assist with those protests saw fit to exert their energies. To do this, we have to consider motivational questions. While it is beyond the scope of this article to analyse participants’ micro-level affinity for movement participation (but see: Abrams, Citation2023), we can nonetheless consider one major factor which served to encourage participation on a macro-level: framing.

Frame diffusion

How movements respond to a political context is affected not only by the empirical presence or absence of opportunity but also by the framing of the situation (Gamson & Meyer, Citation1996). In the case of the UK’s Black Lives Matter protests, we can note the presence of two important shifts in framing that can help explain a rise in movement activity amid a barren opportunity structure: a moral shock following George Floyd’s murder, and diffused opportune framing of protest arising from Black Lives Matter protesters’ successes in the United States. Both of these shifts involved a process of cross-national diffusion, in which Britons came to adopt frames generated elsewhere, and adapt them to their own contentious political struggles.

Moral shocks arise when events – or their framing – provoke ‘such a sense of outrage in a person that she becomes inclined toward political action’, with the effect of amplifying participation both among relatively unaffiliated individuals and established movement partisans (Jasper, Citation1997, p. 106). These conditions propel contact between activists, organisations and movement participants, galvanising social movement activity (Jasper & Poulsen, Citation1995). Analysis by Priniski et al. (Citation2021, p. 4) of US social media discourse supports the notion that a genuine moral shock was generated following Floyd’s murder. Their research – using a sample drawn from Los Angeles twitter data – found a dramatic spike in Black Lives Matter associated discourse in the period between George Floyd’s murder and 1st June, and further content analysis showed that this discourse was consistent with ‘models of how moralized discussions catalyze activism – where positive ingroup attitudes emerge as a shared moral outrage takes hold surrounding an issue’. Of course, in an era of digital media and networked communications, moral frames are seldom bounded by geography, further evidenced by an enormous uptick in attention to racism across the world following Floyd’s murder (see Barrie, Citation2020).Footnote5

Responding to this moral shock, more than 50 countries held solidarity protests with the United States, during which they capitalised on an opportune context in the US in order to further bolster the American movement for Black Lives. In this case, an opportune frameFootnote6 already present in the United States crossed the Atlantic and made landfall in the UK. By responding to an internationally diffused opportune frame – rather than domestic political opportunity structures – many of the concerns that might have otherwise disincentivised participation could have been overlooked by participants in the UK movement’s earliest protests (della Porta, Citation1999, p. 11). Such participants could instead direct their attention to an international political context that would be generative of feelings such as outrage, hope, or confidence, thereby creating a sense of opportunity that defied a domestic structural analysis.

With each successive protest, the framing of movement activity underwent a further process of adaptation, a variety of cross-national diffusion in which ‘an adopter strategically and selectively borrows aspects of another [protest] culture and adapts the imported items to fit with the adopter’s culture … values, beliefs and practices’, (Snow & Benford, Citation1999, p. 30) This was carried out by participants, organisers and other framing agents associated with the movement. This process of adaptation involved foregrounding UK-specific issues like the killing of Belly Mujinga, Steven Laurence and others, as well as a long-running struggle over institutional racism and the UK’s own black radical traditionFootnote7 while also incorporating US-style demands like police divestment, statue-removal and certain symbolic objectsFootnote8 and contentious performances that had proved effective in the US case. This process of frame-adoption then frame-adaptation enabled a sense of opportunity chiefly focused on the United States to galvanise domestic struggles in the United Kingdom, short-circuiting the process by which movements might otherwise weigh their chances in a given political context.

Remaindered resources

Generally speaking, savvy movement partisans are understood to maximise the effectiveness of their resources by carefully responding to fluctuations in opportunity structures and mobilising them accordingly (Giugni, Citation2009; Tarrow, Citation1994). However, movements (or their precursors) may encounter circumstances where they accrue considerable resources but are not immediately presented with conducive political opportunities. Under these circumstances, resources cannot always be perfectly preserved, and so untapped resources (or those waiting in the wings) may be lost (see, e.g. Sawyers & Meyer, Citation1999).

Movement resources are seldom non-perishable, exchangeable goods like fuel or precious metals. Rather, they can be convincingly categorised into five separate groups: ‘material, human, social- organizational, cultural, and moral’ (Edwards et al., Citation2018, p. 80). Many resources within these categories offer diminishing utility the longer they remain idle. Human resources, such as activist commitment are even ‘muscular’ in character, being strengthened by judicious use, and atrophying when idle. Others may become outmoded, physically or informationally decay, or become detached from the movement over time (problems of aggregation and source-constraint). Even those that may seem to maintain their value or utility over time may give rise to certain strategic dilemmas that consume other resources such as money or storage space (Jasper, Citation2006; Slosarski, Citation2023). Except in the case of large-scale endowed organisations, very few movement resources take the form of appreciating assets. Rather, an overall tendency of idle movement resources to diminish means that movements are sometimes well served by mobilising resources in comparatively inopportune contexts. In circumstances where resource decay is ongoing or expected, resource-holders have a greater incentive to take up perceived avenues for resource mobilisation, even where political opportunities seem relatively limited or difficult to ascertain.

Players in UK progressive social movement arenas had gone almost half-a-year without employing their various resources in any serious mobilising capacity by the time the George Floyd protests kicked off in the United States. Given the ongoing context of the COVID-19 pandemic, they would have had little reason to believe that they would be mobilising them in the future. In addition to these retained resources, UK anti-racist movements witnessed a surge in novel human, cultural and moral resources in the form of prospective participants, movement media, and legitimating discourses (respectively). These types of resources cannot be readily held ‘in reserve’ by movements for very long: levels of commitment, cultural attention or moral legitimacy are liable to attenuate or shift according to factors beyond movement control.

Alongside this sudden, novel surge of human, cultural and moral resources came socio-organisational support in the form of pledges of organisational fealty and protest assistance from a litany of law firms, human rights groups and sympathetic journalists.Footnote9 By the end of June, popular financial support was also gathering pace, as hundreds of thousands of pounds poured into movement-associated accounts. One group, ‘UKBLM’ attracted more than £1.2 million in fundraising – far more than it was able to organisationally sustain at the time. Lacking the legal and financial apparatus to handle such a large volume of donations, the group halted their crowdfunder and instead encouraged fundraisers to direct their donations elsewhere while the group worked to disburse the resources it had accrued and begin organising protest actions (UKBLM, Citation2020).

An overwhelming volume of resources flowed into the UK Black Lives Matter movement during the summer of 2020, many of which were – in effect – remaindered between 2020 and 2022. This is to say that – akin to a bookseller’s remaindered stock – they were disbursed in a context where, despite the sub-optimal opportunity structure, retention would have been impractical or impossible. Resource mobilisation thus served as a means of cutting or averting resource losses that would have otherwise been incurred. These remaindered resources helped facilitate short and longer-term mobilisation by grassroots Black Lives Matter groups and organisations from 2020 until the present. Those more ephemeral resources – such as the movement’s influx of human, cultural and moral resources – were rapidly mobilised over the course of the summer, while others, such as material and socio-organisational resources have been more gradually released, with some portion being successfully retained. Indeed, movement funds are still being disbursed as of the writing of this article, and Black Lives Matter groups continue to mobilise against repression by the UK state (BLMUK, Citation2022).

Conclusions

Even though the structural circumstances of their struggle were not politically opportune, protagonists in the UK’s Black Lives Matter movement were nonetheless furnished with conducive conditions for mobilisation in the form of rising biographical availability due to pandemic-related quotidian disruption, moral shocks and opportune frames adopted and adapted from struggles in the United States and relatively incentivized resource mobilisation dynamics. Quotidian disruption increased the pool of potential participants, frame diffusion helped galvanise their readiness for mobilisation, and resource-flows propelled activists and organisers to plan new actions. Under these circumstances, a great many participants, activists and organised groups mobilised in support of Black Lives in the United Kingdom in what appears to be a clear-cut exception to the political opportunity hypothesis (at least in its conventional or consensual form). Here, a marginalised, excluded and discriminated-against group was able to overcome the constraints of opportunity structures and mobilise a broad anti-racist coalition on British streets.

But what does all this mean for the political opportunity hypothesis writ-large? While the UK case may demonstrate that political opportunities are not always necessary for large-scale mobilisations, this exception in the case of mobilisation may in fact help ‘prove the rule’ for other elements of the political opportunity thesis by providing a useful ‘negative case’.Footnote10 When we set aside the relationship between opportunity and mobilisation, the UK case is otherwise strongly consistent with the political opportunity hypothesis, suggesting that inopportune mobilisation does indeed augur ill for movements. The UK’s inopportune national context led to devastating outcomes for the country’s Black Lives Matter movement, as shown in the way that mobilisation begat a surge in anti-movement activity comprising repression, criminalisation, countermovement mobilisation and prohibitions on anti-racist discourse. Such a fate is consistent with arguments made by black radicals such as Kwame Ture (Citation1996), who contended that enemies of racial justice movements ‘will use mobilization to demobilize us [emphasis original]’, in those circumstances where people are ‘instinctively ready to respond against acts of injustice’, but where the opportunity for (or presence of) effective organisation is lacking. Angela Davis (Citation2005, pp. 128–130) has similarly called for a distinction between the potential for mass mobilisation and the development of an efficacious movement. While mobilisation alone might indeed be possible in the absence of opportunity, Davis reminds us that ‘protracted movements … require very careful strategic organizing interventions that don’t always depend on our capacity to mobilize demonstrations’.

But is such a grim fate always inevitable for causes that mobilise in inopportune contexts? One option for protagonists in marginalised or excluded social movements that engage in inopportune contention may be to attempt to shift opportunity structures rather than directly pursue social change. A promising avenue might – for example – involve the staging of ‘eventful protests’ (della Porta, Citation2008) which have the capacity to build longer-running movement commitment and identification and even transform ‘[opportunity] structures … by constituting and empowering new groups of actors or by re-empowering existing groups in new way’ (Sewell, Citation1996, p. 271). Future research might productively compare instances of inopportune mobilisation that feature different protest strategies, in order to establish whether – under the right circumstances – the causal impact of political opportunity structures might be further circumvented. A further direction of value would be more systematic or nuanced investigation of how international political contexts may influence both the perception and structure of opportunity in domestic contexts, what the amplifying or mitigating factors may be to such influence, and how it would affect the formation and development of social movement ‘offshoots’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The author was physically present at this protest, but one may also see the march in, for example, live footage from GlobalNews (Citation2020).

2 Kay’s (Citation2005) concept of ‘Transnational Political Opportunity Structures’ and Van der Heijden’s (Citation2006) notion of the ‘International Political Opportunity Structure (IPOS) take political opportunities beyond the state level and instead study intergovernmental institutions and transnational struggles over issues such as trade and environmentalism’. Though both preserve McAdam’s core framework, these variants replace state structures with ‘a composite of a number of International Governmental Organizations (IGOs) like the UN, the EU, the World Bank, and the IMF … formal treaties, international regime systems of global governance, as well as, sometimes, structures of norms and values’, (Citation2006, p. 32).

3 See, for example: Ellefsen (Citation2021) Giugni and Grasso (Citation2016); Zachrisson and Lindahl (Citation2019).

4 See guidance provided by the Green and Black Cross (Citation2020) for an explanation of these powers as they pertained to protest.

5 Moreover- and I am grateful for one of the anonymous reviewers for emphasising this point- this may be especially unsurprising in the context of countries that share a common language and strong cultural ties.

6 Conceptualised as ‘characterized by … the perception that a contentious accomplishment is possible or achievable … in response to domestic or world events [or] consciously presented as motivational collective action frames by organised agitators that explicitly attribute a specific set of opportunities to the situation at hand' (Abrams, Citation2023, p. 48).

7 Within Europe, this phenomenon is not unique to the UK. France and the Netherlands – for example – play host to their own rich traditions of black radicalism.

8 ‘Symbolic objects' refer to the various material items that can manifest meanings, narratives, emotions and other substantive content through their appearance in contentious political activity. See: Abrams & Gardner (Citation2023).

9 See, for example, INQUEST’s letter of support (Citation2020) signed by 19 law firms, 100 further legal professionals and 56 civil rights organizations, declaring their commitment to ‘a social movement that must see radical structural change’.

10 Something which political opportunity theories have long been accused of sorely lacking. See: Goodwin & Jasper (Citation1999).

References

- Abrams, B. (2023). The rise of the masses: Spontaneous mobilization in contentious politics. University of Chicago Press.

- Abrams, B., & Gardner, P. R. (Eds.) (2023). Symbolic objects in contentious politics. Michigan University Press.

- Agarwal, P., Figueroa, M., Andrews, K., & Meghji, A. (2021, March 31). Black Lives Matter: Has anything really changed? YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KC9saW-davE.

- Attewill, F. (2006, September 9). Johnson eats his words after cannibal gaffe. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2006/sep/09/uk.conservatives.

- Baah, N. (2020 June 2). ‘This Is the Turning Point Now’ – Meet the young black women behind London’s George Floyd protest. Vice. http://vice.com/en/article/bv8z95/george-floyd-protests-black-lives-matter-london.

- BAME Labour. (2021, June 7). BAME Labour. https://www.bamelabour.org/.

- Barrie, C. (2020, November 4). Searching racism after George Floyd. Socius. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120971507.

- BBC. (2020a, May 10). Stretford Taser arrest: Campaigners protest at petrol station. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-manchester-52598702.

- BBC. (2020b, May 24). Coronavirus: Schools in England reopening on 1 June confirmed, PM says. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-52792769.

- BBC. (2020c, May 31). George Floyd death: Thousands join UK protests. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-52868465.

- BBC. (2020d, July 2). Black Lives Matter: Sir Keir Starmer ‘Regrets’ calling movement a ‘Moment’. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-53267989.

- BLMUK. (2022, February 12). FAQ – Black Lives Matter. https://ukblm.org/faq/.

- Busari, S. (2019, July 23). ‘Watermelon Smiles’ and ‘Piccaninnies’: What Boris Johnson has said previously about people in Africa. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2019/07/23/africa/boris-johnson-africa-intl/index.html.

- Cameron, A. (2020, July 8). Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK. Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020#homeworking-by-ethnicity.

- Chada, R. (2020, June 3). Protests and arrests under Regulation 7 of Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2000. Hodge Jones & Allen Solicitors. https://netpol.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Letter-to-Met-final.pdf.

- Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities. (2021, March 31). Foreword, introduction, and ull recommendations. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-report-of-the-commission-on-race-and-ethnic-disparities/foreword-introduction-and-full-recommendations.

- Davis, A. Y. (2005). Abolition democracy: Beyond empire, prisons and torture. Seven Stories Press.

- della Porta, D. (1999). Social movements in a globalizing world: An introduction. In D. della Porta, H. Kriesi, & D. Rucht (Eds.), Social movements in a globalizing world (pp. 3–22). Palgrave Macmillan.

- della Porta, D. (2008). Eventful protest, global conflicts. Distinktion: Journal of Social Theory, 9(2), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1600910X.2008.9672963

- Department for Education. (2021, November 9). Political impartiality in schools. Gov.Uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/political-impartiality-in-schools/political-impartiality-in-schools.

- Dugomore, O. (2020, June 3). Speaking to Black Lives Matter protesters in London. YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1wxFnDdPXc.

- Duncan, P., & Holder, J. (2017, September 25). Revealed: Britain’s most powerful elite is 97% white. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/inequality/2017/sep/24/revealed-britains-most-powerful-elite-is-97-white.

- Edwards, B., McCarthy, J. D., & Mataic, D. R. (2018). The resource context of social movements. In D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, H. Kriesi, & H. J. McCammon (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell companion to social movements (2nd ed., pp. 79–97). Wiley.

- Ellefsen, R. (2021). The unintended consequences of escalated repression. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 26(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.17813/1086-671X-26-1-87

- Elliot-Cooper, A. (2021). Black resistance to British policing. Manchester University Press.

- Evans, R., & Morris, S. (2022, February 15). British BLM Group closes down after police infiltration attempt. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2022/feb/15/swansea-black-lives-matter-british-blm-group-closes-down-after-police-infiltration-attempt.

- Fiorella, G. (2021, November 9). First steps to getting started in open source research. Bellingcat.com. https://www.bellingcat.com/resources/2021/11/09/first-steps-to-getting-started-in-open-source-research/.

- Gamson, W. A., & Meyer, D. (1996). Framing political opportunity. In D. McAdam, J. D. McCarthy, & M. N. Zald (Eds), Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings (pp. 275–290). Cambridge University Press.

- Gidda, M. (2020, May 26.). BAME people disproportionately targeted BY coronavirus fines. Liberty Investigates. https://libertyinvestigates.org.uk/articles/bame-people-disproportionately-targeted-by-coronavirus-fines/.

- Giugni, M. (2009). Political opportunities: From tilly to tilly. Swiss Political Science Review, 15(2), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1662-6370.2009.tb00136.x

- Giugni, M. and Grasso, M.T. (2016). How civil society actors responded to the economic crisis: The interaction of material deprivation and perceptions of political opportunity structures. Politics & Policy, 44(3), 447–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/polp.12157

- GlobalNews. (2020, June 6). George Floyd protests: Anti-Black racism demonstrators rally in London's Parliament Square. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mMTst2ztdyo.

- Goodwin, J., & Jasper, J. (1999). Caught in a winding, snarling vine: The structural bias of political process theory. Sociological Forum, 14(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021684610881

- Green and Black Cross. (2020, March 1). Coronavirus police powers and their use on protests. Green and Black Cross. https://web.archive.org/web/20200617000013/https://greenandblackcross.org/guides/coronavirus/2-police-powers/.

- Hammond, C., Ncube, M., & Fido, D. (2021, October 7). ). A Foucauldian discourse analysis of the construction of People of Colour (POC) as criminals in UK and US print media following the Black Lives Matter protests of May 2020. PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/3yp45.

- Hart, R. J. (2021). A penchant for protest? Contention, 9(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3167/cont.2021.0902OF

- The Herald. (2021, June 20). Letters: Britain is not racist — It’s the BLM protests that are stirring up racial tension. HeraldScotland. https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/19385588.letters-britain-not-racist—-blm-protests-stirring-racial-tension/.

- HM Revenue & Customs. (2020, July 15). Coronavirus job retention scheme statistics: July 2020. Gov.Uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-july-2020/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-july-2020.

- Home Office. (2021a, March 10). Police, crime, sentencing and Courts Bill 2021: Protest powers factsheet. Gov.Uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/police-crime-sentencing-and-courts-bill-2021-factsheets/police-crime-sentencing-and-courts-bill-2021-protest-powers-factsheet.

- Home Office. (2021b, October 6). Hate crime, England and Wales, 2020 to 2021. Gov.Uk. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crime-england-and-wales-2020-to-2021/hate-crime-england-and-wales-2020-to-2021.

- INQUEST. (2020, June 12) Civil rights and civil liberties lawyers and campaigners stand with family of George Floyd and Black Lives Matter. Inquest. https://www.inquest.org.uk/george-floyd-blm-letter.

- Jasper, J. (1997). The art of moral protest: Culture, biography and creativity in social movements. University of Chicago Press.

- Jasper, J. (2006). Getting your way: Strategic dilemmas in the real world. Chicago University Press.

- Jasper, J., & Poulsen, J. D. (1995). Recruiting strangers and friends: Moral shocks and social networks in animal rights and anti-nuclear protests. Social Problems, 42(4), 493–512. https://doi.org/10.2307/3097043

- Joseph-Salisbury, R., Connelly, J., & Wangari-Jones, P. (2020). “The UK is not innocent”: Black Lives Matter, policing and abolition in the UK. Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal, 40(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-06-2020-0170

- Kay, T. (2005). Labor transnationalism and global governance: The impact of NAFTA on transnational labor relationships in North America. American Journal of Sociology, 111(3), 715–756. https://doi.org/10.1086/497305

- Made, T. (2020, June 2). George Floyd March in London [Full Day] – Black Lives Matter Protest ✊. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EyllxLTNkuk.

- McAdam, D. (1986). Recruitment to high-risk activism: The case of freedom summer. American Journal of Sociology, 92(1), 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/228463

- McAdam, D. (1996). Conceptual origins, current problems, future direction. In D. McAdam, J. D. McCarthy, & M. N. Zald (Eds), Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings (pp. 23–40). Cambridge studies in comparative politics. Cambridge University Press.

- McGuinness, A. (2021, March 15). Police, crime, sentencing and Courts Bill: What’s in it and why it’s caused controversy after Sarah Everard’s death. Sky UK. https://news.sky.com/story/mps-back-governments-crime-bill-whats-in-it-and-why-its-caused-controversy-after-sarah-everards-death-12246992.

- McIntosh, K. (2020, September 25). Everything you need to know about Black Lives Matter UK. gal-dem. https://archive.ph/4FKwx.

- McPherson, E., Guenette Thornton, I., & Mahmoudi, M. (2020). Open source investigations and the technology-driven knowledge controversy in human rights fact-finding. In S. Dubberley (Ed.), Digital witness: Using open source information for human rights investigation, documentation and accountability (pp. 68–86). Oxford University Press.

- Media, R. (2020, June 2). Black Lives Matter – London protest 31ST May. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ua8bsSHJsJA.

- Mohdin, A. (2020, July 29). ‘We couldn’t be silent’: The new generation behind Britain’s anti-racism protests. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jul/29/new-generation-behind-britain-anti-racism-protests-young-black-activists-equality.

- Mohdin, A., Swann, G., & Bannock, C. (2020, July 29). How George Floyd’s death sparked a wave of UK anti-racism protests. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/jul/29/george-floyd-death-fuelled-anti-racism-protests-britain.

- Muir, E. (2020, July 3). Labour no longer stands with black people – So I’m leaving. Metro. https://metro.co.uk/2020/07/03/labour-party-no-longer-safe-place-black-people-who-vote-now-2-12933468/.

- Network for Police Monitoring. (2020 June 10). 8–9 June update. Policing the Corona State. https://policing-the-corona-state.blog/2020/06/10/8-9-june-update/.

- Opinium. (2020, November 30.). Black history month – Black Lives Matter report. Opinium. https://www.opinium.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Perceptions-of-the-Black-Lives-Matter-movement-Report.pdf.

- PANews. (2021, April 6). Family of belly Mujinga call for police to disclose spitting suspect’s name. News and Star. https://www.newsandstar.co.uk/news/national/19210812.family-belly-mujinga-call-police-disclose-spitting-suspects-name/.

- Patel, P. (2020, October 4). Fixing our broken Asylum system. Conservatives.Com. https://www.conservatives.com/news/2020/priti-patel–fixing-our-broken-asylum-system.

- Pinckney, J., & Rivers, M. (2021). Sickness or silence: Social movement adaptation to COVID-19. Journal of International Affairs, 73(2), 23–42.

- Priniski, J. H., Mokhberian, N., Harandizadeh, B., Morstatter, F., Lerman, K., Lu, H., & Brantingham, P. J. (2021). Mapping moral valence of tweets following the killing of George Floyd. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.09578 (2021).

- Rogers, A. (2022, January 21). Rory Stewart delivers withering attack on Boris Johnson. HuffPost UK.. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/rory-stewart-withering-attack-boris-johnson-whip-system_uk_61ea83b5e4b0c24d4dd46558.

- Saggar, S. (2016). British citizens like any others? Ethnic minorities and elections in the United Kingdom. In A. Bilodeau (Ed.), Just ordinary citizens? Towards a comparative portrait of the political immigrant (pp. 63–82). University of Toronto Press.

- Salmond, C. (2020, June 7). Black Lives Matter: Nicola Sturgeon urges public not to attend protests. Edinburgh News. https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/politics/black-lives-matter-nicola-sturgeon-urges-public-not-attend-protests-2877137.

- Sawyers, T. M., & Meyer, D. (1999). Missed opportunities: Social movement abeyance and public policy. Social Problems, 46(2), 187–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/3097252

- Sewell, W. H. (1996). Three temporalities: Toward an eventful sociology. In T. J. Mcdonald (Ed.), The historic turn in the human sciences (pp. 245–280). Ann Arbor University of Michigan Press.

- Siddique, H. (2021, April 28). Anti-protest curbs in UK policing bill ‘Violate International Rights Standards’. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/apr/28/policing-bill-will-have-chilling-effect-on-right-to-protest-mps-told.

- Skwawkbox. (2020, June 26). EHRC director failed to declare donations to Tory party – And EHRC defends her. Skwawkbox.org. https://skwawkbox.org/2020/06/26/ehrc-director-failed-to-declare-donations-to-tory-party/.

- Slosarski, B. (2023). A strategic toolbox of symbolic objects: Material artifacts, visuality and strategic action in European street protest arenas. In B. Abrams & P. R. Gardner (Eds), Symbolic objects in contentious politics (pp. 39–53). Michigan University Press.

- Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. (1999). Alternative types of cross-national diffusion in the social movement arena. In D. della Porta, H. Kriesi, & D. Rucht (Eds.), Social movements in a globalizing world (pp. 23–40). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Snow, D. A., Cress, D., Downey, L., & Jones, A. (1998). Disrupting the “Quotidian”: Reconceptualizing the relationship between breakdown and the emergence of collective action. Mobilization, 3(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.3.1.n41nv8m267572r30

- Steele, R. D. (2007). Open source intelligence. In L. K. Johnson (Ed.), Handbook of intelligence studies (pp. 147–165). Routledge.

- Stone, J. (2020, October 5). Black Lives Matter is ‘Not Force For Good’ says Tory MP Sajid Javid. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/sajid-javid-black-live-matter-blm-racism-tory-mp-b806336.html.

- Tarrow, S. (1994). Power in movement (1st ed). Cambridge University Press.

- Taylor, M. (2022, January 13). How will the police and crime bill limit the right to protest? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/law/2022/jan/13/how-will-the-police-and-bill-limit-the-right-to-protest.

- Tilly, C., & Tarrow, S. (2006). Contentious politics (1st ed). Oxford University Press.

- Ture, K. (1996). Converting the unconscious to conscious [Audio Recording]. https://archive.org/details/Dr.KwameTureAkaStokelyCarmichaelConvertingTheUnconsciousToTheConsciousOURWorldsHiSTORY.

- UKBLM. (2020, October 30). UKBLM fund, organised by UKBLM fund. GoFundMe. https://www.gofundme.com/f/ukblm-fund.

- United Nations. (2023, January 27). UK: Discrimination against people of African descent is structural, institutional and systemic, say UN experts. OHCHR. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/01/uk-discrimination-against-people-african-descent-structural-institutional.

- Van der Heijden, H.-A. (2006). Globalization, environmental movements, and international political opportunity structures. Organization & Environment, 19(1), 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086026605285452

- Venn, L. (2020, June 3). The celebrities attending Black Lives Matter protests. The Tab https://thetab.com/uk/2020/06/03/these-are-the-celebs-attending-the-black-lives-matter-protests-159959.

- Wahlstrom, M., & Peterson, A. (2006). Between the state and the market: Expanding the concept of ‘Political Opportunity Structure’. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699306071677

- White, N. (2020, June 5). Thousands back open letter citing BAME voters’ ‘loss of trust’ in Labour Party. HuffPost UK. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/labour-leaked-report-letter-bame-voters_uk_5eda495cc5b6adc2ed8b88c7.

- Zachrisson, A., & Lindahl, K. B. (2019). Political opportunity and mobilization: The evolution of a Swedish mining-sceptical movement. Resources Policy, 64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.101477