ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to report on a collaborative project that investigated the value and use of the contents of estate archives. Context is provided by outlining the type of information often found within estate records, its potential value to a wide range of users, indicating some of the initiatives which have helped to open up estate archives, before exploring some of the difficulties associated with accessing these records and making optimal use of them. This is followed by a description and evaluation of the initial stage of the project, which collected data about the significance, discoverability, accessibility and use of estate archives. This was achieved by inviting a purposive sample of archive users to attend one of the three knowledge exchange workshops in different parts of Wales. Participants were asked for their views on the value of estate archives, current and potential uses of estate records, and they were asked to suggest ways in which these records could be promoted more widely and used more effectively. Finally, opinions were gathered about the desirability of creating an online toolkit for estate records. Data gathered at these events was used to create a detailed blueprint of the proposed toolkit.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The sheer breadth and richness of information that can be found within estate archives confirms their place as an important cultural heritage asset in the UK and beyond. A number of initiatives to widen access to estate archives have taken place in recent years, including cataloguing projects, the production and publication online of finding aids and guidance for specific estate archives, or particular types of records commonly found within these collections. Nevertheless, anecdotal evidence suggests that many people remain unaware of the value of the records found within estate archives and, consequently, they are not used as much or as effectively as they might be. This paper reports on the first stage of a project which set out to capture user views of estate archives and ways in which their contents could be promoted and used more effectively.

Estate archives

An estate archive has been described as, ‘an accumulation of records relating to the acquisition and management of a landed estate.’Footnote1 This explanation can be expanded by the definition given in the introduction to the Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts’ (HMC) Guide to Principal Family and Estate Collections to encompass ‘the whole archive created by a family and its employees,’ including, ‘not only papers accumulated by successive heads of the family and their wives or husbands but also material created by stewards, land agents, solicitors, architects, house keepers, private secretaries, librarians and others.’Footnote2

Estates come in all shapes and sizes: some have been owned by the same family since medieval times and continue to operate as private businesses whilst others are held in trust for the nation and are open to the public. Corporate estates, like those of the Duchy of Lancaster and the Crown Estate, also own significant assets in Wales as does the Welsh Church Commission,Footnote3 Natural Resources Wales (which includes the former Forestry Commission) and various Oxbridge colleges. Estates can be spread all over the country or concentrated in one part of a county. Hence, the archives generated by the activities that have taken place on landed estates vary in range, size and chronological span.

Each archive is unique, and the records found within them are dictated by the location and nature of the estate, as well as by the business concerns and interests of current and former owners. The owners of larger estates may well have a number of interests in different businesses which may, or may not, be inter-connected and managed by the same personnel. A flavour of the diverse nature of these businesses can be deduced when it is considered that they can include tenancies of property and land, leases of mineral and fishing rights, sale of timber, fees for the use of property and land for specific events, as well as the exploitation of historical material relating to the estate for various heritage activities.Footnote4 For example, as well as 68,700 acres of common land, and mineral-only interests in 247,000 acres in Wales, the Crown Estate enjoys the rights to any resources lying in the seabed up to 12 nautical miles from the Welsh coast. This provides various opportunities to profit from mineral extraction, and the development of renewable energy, as well as charge for underwater pipes and cables.Footnote5 Similarly, the Duchy of Lancaster’s holdings include the Ogmore estate in South Wales, comprising a castle, c. 4,000 acres, a golf course and a working limestone quarry.Footnote6

Family and estate collections can be found in a wide range of archives across the sector, from local authority, to university and specialist repositories, making them potentially relevant for many types of research. An article was published in the Journal of the Society of Archivists that advocated a scheme of arrangement designed to help archivists deal with large amounts of unlisted material commonly found in these collections. This plan provides a flavour of the extent, richness and diversity of records found within estate archives.Footnote7 It is worth citing the major record types identified by the authors to appreciate the wide range of material, which can appear in these collections. These can include: manorial records, title deeds, wills and settlements, legal case papers, estate management papers, household records, charity records, school records, ecclesiastical records, business records, family and personal papers, official papers, maps and plans, printed and pictorial material, and any miscellaneous material falling outside the categories already listed. Browsing the Family section of The National Archives’ (TNA) Discovery webpages dedicated to record creators provides examples of different types of estate records falling within these broad categories.Footnote8

A guide concerned with the retention of modern estate records outlines the main types of records generated by landed estates in operation today.Footnote9 Current and future records are and will be created in different formats from their traditional counterparts, which has storage and access implications. However, their content remains closely tied to retaining title to land and property, asset management and exploitation, as well as records related to employees, health and safety matters, amongst other things. A portion of these records will form accruals to existing archives and the imposition of considered retention policies should ensure their survival for the future.

Potential value

Anyone who is unfamiliar with the contents of family and estate collections may fail to appreciate the potential of these records for researchers of all types and the public in general. Not only do the records constituting these collections form an important group alongside others, such as those created by local and central government, and law courts, but they can be used together profitably to gain new and deeper insights into various aspects of research.Footnote10

One of the comments within the Logjam Report, which assessed the extent of uncatalogued archive collections in North West England c. 2003, asserted that there is a ‘false perception that [estate and family collections] represent the interest and views of the landed elite. In fact they are very revealing of the lives of ordinary people: tenants, servants, trades people, etc.’Footnote11 Similarly, John Habakkuk’s foreword to HMC’s Principal Family and Estate Collections stated that, ‘the estate and family records of the great British landowners are probably, of their kind, unequalled in range and continuity… these families occupied until recently so central a role in national life that the records also illuminate the activities of most other groups in society … there is scarcely an aspect of social and economic history for which these family collections do not provide useful material.’Footnote12 The historic and cultural value of estate archives is recognized publicly through the Waverley Criteria,Footnote13 which is employed when appraising privately owned collections offered in lieu of, or to obtain conditional exemption from, Inheritance Tax in return for public access.Footnote14

It is possible to identify particular types of records that are especially valuable for specific research. For example, Lomas suggested that, ‘employment records, rent rolls and cash books running over long periods indicate the complex social and economic structure of the estate and are crucial for an understanding of its running and organization,’ whereas, ‘records of shoot returns, vermin destruction, maps and plans’ are useful for environmental research which seeks to explore changes in the estate’s landscape and the wildlife living within it.Footnote15

A great investment in terms of time and expertise is required to catalogue large estate archives. In the past, this has resulted in these archives often forming a significant proportion of backlogs in archive repositories, thus sometimes remaining invisible to potential users until appropriate finding aids have been created. More recently, funding from various bodies has been made available for financing cataloguing or upgrading existing catalogues to make these collections more accessible for research purposes and public engagement activities alike. Five out of the 13 projects awarded National Cataloguing grants in 2012 featured family and estate collections,Footnote16 enabling those collections to be catalogued to current international standards. The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) has also financed other access initiatives that have involved upgrading existing catalogues, such as the Estates Records Project at King’s College, Cambridge University.Footnote17

Guides and guidance

Many UK archive repositories with rich holdings of estate archives have published guides online to assist researchers make effective use of this material for various historical research purposes. For instance, the ‘Research Guide for Landed Estates,’Footnote18 created by TNA, provides brief background information about the significance of landed estates, the records which may have survived, and links to other useful websites. Nottingham University’s Manuscripts and Special Collections’ online guide for Family and Estate CollectionsFootnote19 not only offers an introduction to the significance of these records, but outlines the types of research they can be used for, the potential users of this material, as well as drawing the reader’s attention to various issues when using these collections. The online guide produced by the National Records of ScotlandFootnote20 offers information about locating the land owners of specific estates and also identifies some of the main surviving estate records and a description of what they can offer researchers. Bedfordshire & Luton Archive Service’s ‘Researching Garden History’ guideFootnote21 provides pre-visit advice before providing an indication of source material likely to be of help to searchers. Anyone seeking an indication of the richness and diversity of the material which can be found in an estate archive can browse the contents of the Staffordshire & Stoke on Trent Archive Service’s webpages on the Sutherland Collection.Footnote22 This website enables people to explore these papers thematically, providing contextual information, digitized images of sample records complemented by transcriptions of related material.

Searching the ‘Family’ webpages of TNA’s websiteFootnote23 provides a brief description of the nature and extent of surviving records relating to the numerous families listed on the database; it provides information about where these collections are held and whether they are freely accessible to the public. Similarly, the adjoining ‘Manor’ webpagesFootnote24 provide the same information for collections of manorial records. Resources such as Discovery, the online archival networksFootnote25 and archive catalogues enable researchers to track down material of interest. What might not be so apparent to users are the potential difficulties using estate records effectively or even or at all, but more will be said about this later.

As mentioned above, manorial records can be a sub-set of estate archives, and the only estate records which are afforded legal protection via the Manorial Documents Rules.Footnote26 Anyone with an interest in these particular records can access the Cumbrian Manorial Records website, published in 2006. This resource is a result of an HLF initiative between Lancaster University, the Cumbrian Archive Service and TNA. The introductory page state that ‘this project aimed to raise awareness and encourage use of an important but under-used class of local historical evidence, the records generated by manorial administration. These records shed vivid light on past local communities … and [manorial] records give rare glimpses of the lives of ordinary men and women, particularly in the 15th to 18th centuries.’Footnote27 Undoubtedly this resource is extremely useful for anyone who has encountered manorial records and wants to find out more about their significance, and the meaning of legal and archaic terminology. The Gallery features digitized images of examples of a wide range of manorial records accompanied by commentary, which identified the record type and explained what it was about. Finally, web links are given for a number of other websites and online resources which can assist users to locate of manorial records, use and interpret them, as well as pointers to general family and local history resources. The project website complements TNA’s online Manorial Documents Register,Footnote28 and was designed to assist anyone interested in family and local history to locate and effectively use manorial records.

Another initiative which aims to widen access to a specific type of record which can be found within estate archives is the Mapping the Medieval Countryside Project: Properties, People and Places. The purpose of this collaboration between the University of Winchester and King’s College, London, is to create an online edition of medieval Inquisitions Post Mortems (IPM) by digitizing and enhancing the printed calendars. Information is provided about the legal and administrative significance of these records and access is given to an online glossary of legal and specialist terms commonly found in this type of record. Although this project is currently a work in progress, by the time that it has been completed, it will be possible for users to browse all the IPMs (1320–1480) generally, or specifically by person or place.Footnote29

Finally, valuable research guidance on manorial records, title deeds, accounting records, maps and plans, weights and measures, as well as dating documents is provided via the University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections webpages.Footnote30 It is claimed that ‘researchers using archives from any English record office will find the advice relevant’Footnote31 but this resource is of greater significance, and of interest to anyone using archives.

Educational programmes and initiatives

As well as the investment of public funds in cataloguing and other initiatives to widen access, there is evidence of greater use of estate archives to further academic studies, particularly in the history of country houses, landed estates and landscapes. For example, the ‘Study’ webpages pages of The Country Seat website, maintained and updated by Matthew Beckett,Footnote32 (‘find out about the history of the UK’s country houses and stately homes’) contains links to various University modules and degree programmes. A number of Higher Education institutions offer certificate courses (for continuing education) and individual modules within degree schemes based around the country house, and associated studies of the landscape, gardens and architecture. Leicester University’s MA in the Country HouseFootnote33 was at the forefront of this initiative in the UK. The University of Groningen, in the Netherlands, has gone further than most by creating its own interdisciplinary teaching and research programme focussed on country houses and landed estates, with a specially appointed Professor and lecturer attached.Footnote34

Other universities host national or regional centres for teaching, inter-disciplinary research and public engagement activities, which collaborate fruitfully with institutions and bodies outside higher education. For example, in Wales, the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates (ISWE) was established at Bangor University in 2013 with the aim to ‘develop… a world-class research profile, driven by projects and initiatives inspired by Wales’ incredibly rich estate heritage.’Footnote35 Similarly, the Yorkshire Country House Partnership (YCHP)Footnote36 comprises staff based in a number of departments in York University together with representatives drawn from a number of the county’s country houses. There are also numerous examples of direct partnerships between universities and country houses, such as various collaborative doctoral projects focussed on Chatsworth.Footnote37

Finally, it is possible to find other educational institutions offering evening classes and other courses featuring landed estates, the landscape, the people and the structure and contents of buildings associated with them. A well-known example of this is the Attingham Trust, established in 1952, which has offered many courses over the years concerning the study of historic houses and collections, which are, ‘highly regarded by museums, universities, historic preservation societies and architectural practices throughout the world.’Footnote38

Barriers to use

Despite the rich research potential of estate archives, and the increasing availability of resources and courses to help users discover and access estate records, it has been suggested anecdotally that these remain some of the least used records in many archives today. Many of these barriers are either technical or cultural.

In the past, one of the main obstacles preventing or restricting use has been the initial difficulty discovering the whereabouts of specific estate records and, perhaps, obtaining permission to view them since the public does not have automatic rights to access privately owned material.Footnote39 The potential scale of this problem can be seen when considering the claim that it is unusual for records associated with the largest landed estates records to be found in fewer than four different places, and sometimes they can be found in more than 20 locations.Footnote40 As Habakkuk noted, ‘tracking down the component parts [of family and estate archives] in public and private repositories can be a frustrating and often unsuccessful enterprise.’Footnote41 In more recent years, this situation has been alleviated by the ability to conduct online searches for records relating to the family and estate collections featuring in TNA’s Discovery webpages dedicated to record creators.Footnote42 Also, HMC’s GuideFootnote43 provides an outline of the creation of the 118 principal family and estate collections in the UK, together with a summary description and location information of their contents. Many estate archives have been retained as ‘private’ collections by their creators, some of which are represented by the Historic Houses Archivists Group.Footnote44 Some private landowners do allow bona fide researchers to use their material but there may be conditions imposed, including financial charges. Access to archives held within publicly funded archives, libraries and other institutions is usually permitted, but restrictions can be applied if the papers are uncatalogued, in a poor state of preservation, if there is an embargo in place, or the owner requires prior permission to have been obtained. The sheer size of some of these collections, preservation issues, and difficulties understanding and using accompanying finding aids might deter many potential users. Even people who have successfully identified and obtained access to the material they wish to read may still be thwarted when they find they are unable to read the hand in which the records are written, or they don’t understand the language used — be it Latin, archaic English or legalese.

As alluded to earlier in the section on potential value, there has sometimes been a public misconception that the content of family and estate papers represents the views and interests of a narrow section of society with little relevance to most other people. However, efforts are underway to reinterpret the past to highlight the wider societal value of estate archives and heritage as a whole. This can be detected in the views of people like Hilary McGrady, the director-general of the National Trust, who spoke last year about the organization’s efforts to broaden its appeal to those living in urban areas by making visitors’ experiences more relevant to their everyday lives.Footnote45

‘Opening the vaults’ project

Project background

ISWE was set up at Bangor University 5 years ago with the specific task of ‘promoting research into the history, impact and functioning of estates on a Wales-wide basis … [it] seeks to advance outstanding research into the subject and ensure that the knowledge we generate regarding Wales’ past is accessible and contributes constructively to its future.’Footnote46 In an effort to foster and promote the use of estate archives within Wales, the Director of ISWE at Bangor University invited staff based in Welsh archive repositories, ISWE, and the Department of Information Management, Libraries and Archives (iMLA) at Aberystwyth University to meetings convened at the Glamorgan Archives, Cardiff and at Bangor University in March 2016. A representative from each of the Welsh archives was also asked to complete a survey concerning estate archives which, amongst other things, asked about the types of estate records most/least used by researchers in their repository, and their perceptions of barriers to the use of estate collections.

Participants and questionnaire respondents identified a number of common problems associated with estate records, which could explain the perceived under-use of this type of material. Common issues identified by archivists and academics alike included:

the sheer size of these collections

the extent and depth of cataloguing

the variety and diversity of extant material

located in various places

different rights of access/no access

varying states of preservation

the requirement for specific palaeographic, linguistic and interpretative skills to use this material effectively

Toolkit

As a result of these consultations, one of the suggestions for encouraging more people to use estate archives was to create an online toolkit, inspired partially by the website of the Cumbrian Manorial Records Project and Nottingham University’s online Research Guidance, previously referenced.Footnote47 It was proposed initially to gather opinion from users and custodians about the desirability of developing a resource to aid the discoverability, accessibility, and usability of estate records. As well as assisting estate administrators and lawyers, and external researchers like local and family historians, and postgraduate students, such a device could lead to greater public engagement with estate archives, which would accord with government agenda for archives.Footnote48 The discussions would also broach the subject of the shape and content of an online toolkit, so that it would be designed to cater for the needs of current and future users as far as possible.

A toolkit is ‘a collection of related information, resources, or tools that together can guide users to develop a plan’Footnote49 or equip them with the knowledge and resources to enable them to pursue their research interests more effectively. Increasingly, toolkits comprise web-based resources and guidance which can be adapted to evolve over time in response to the prevailing environment, as well as the development and availability of relevant material. There is no shortage of ‘toolkit examples’ on the internet, or information on how to design, build and develop these resources. Toolkits figure prominently in education and have been used to bring together digital resources and related guidance of interest to learners/educators on a single online platform, making it far simpler and quicker for people to access a range of information. A good example of this is the University of Aberdeen’s Toolkit. This ‘multi-award winning, digital information resources for staff and students’ incorporates information about the University and its systems, tools to enable people to carry out their work more efficiently and effectively, as well as provides access to a suite of resources designed to equip users with the knowledge and capabilities to keep pace with the digital environment.Footnote50 This is the sort of resource which could be developed for users of estate archives; it could provide a focal point for guidance and any other type of information likely to equip people with the skills needed to optimize their use of these records.

Project planning

In March 2017, a successful bid was made to Bangor University’s ESRC Impact Acceleration Account,Footnote51 which offers funding specifically to ‘build networks with potential users of … research’ and to ‘improve engagement with … civil society … and publics.’Footnote52 The project was an initiative of Bangor University’s ISWE and its purpose is clearly shown by its title, Opening up the Vaults’: Co-producing an Online Toolkit to Improve the Discoverability and Accessibility of Welsh Estate Archives. The proposal involved a Principal Investigator and two Co-Investigators collaborating with representatives of the archive and user communities to gather information about the significance, use and limitations of estate archives and opinions about the value, or otherwise, structure and content of a bespoke toolkit.

In an effort to build on the previous consultations carried out with archivists via survey feedback and two face-to-face meetings in 2016, it was decided to convene three knowledge exchange workshops in archive repositories in North, Mid and South Wales, respectively. These all-day regional events would bring together both users and custodians of estate archives to discuss the promotion and use of estate records, and ensure that views, expertise and needs from all perspectives were taken into account in the design of a toolkit blueprint. An initial list of groups to be represented at these fora was drawn up after speaking to various archivists about the types of people who used/might use estate records. These groups included members of family and local history societies, the academic community (staff and students), independent researchers and record agents, land managers, curators and heritage professionals, as well as staff based in Welsh archive repositories and private estate offices. It was planned that each event would begin with a welcome from the project team outlining the purpose and structure of the day, followed by brief introductions by all participants. The display of a showcase of material drawn from the host’s collections, as well as the distribution of copies of selected records were designed to aid group discussions on the value and potential difficulties associated with using estate archives. It was hoped they would also stimulate debate at the end of the workshop about the design and content of the proposed toolkit. To meet ethical guidelines, drafts were produced of an invitation to participate in a workshop, an information letter explaining the purpose of the project and promising confidentiality, as well as a consent form.Footnote53

Knowledge exchange workshops

A pilot study of the knowledge exchange workshop was carried out during a dissertation study school for MA Archives Administration students at Aberystwyth University in April 2017. Three participants reviewed and commented constructively on the supporting documentation relating to the workshops to ensure it was coherent, well structured, and likely to generate the sort of data required to achieve the purpose of the project.Footnote54 As a result, amendments were made to the participant profile questionnaire and the proposed programme of workshop activities. In addition, useful data about the participants’ own experiences of using estate archives was obtained, as well as valuable suggestions about information, guidance and resources which could form part of the proposed toolkit.

People drawn from a range of backgrounds, ages, locations and experience of using archives generally and estate archives in particular were invited to participate in the one-day workshops. Everyone who accepted the invitation to participate was asked to read an information letter and complete the accompanying consent form and the profile questionnaireFootnote55 beforehand. The letter and consent form outlined the purpose of the project and explained what the workshop would involve. Confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed, and participants were told they could withdraw from the project at any time without explanation.

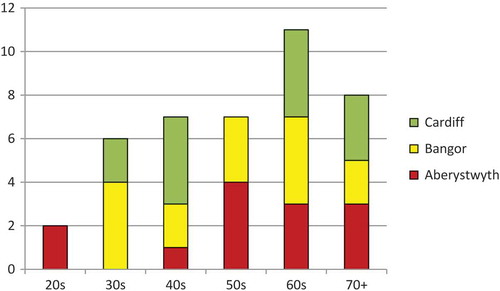

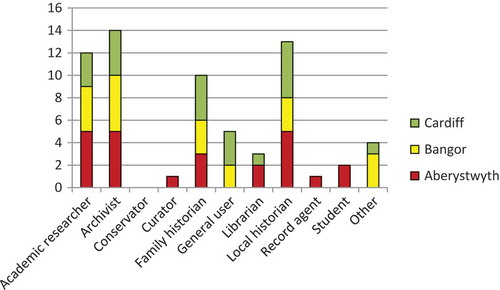

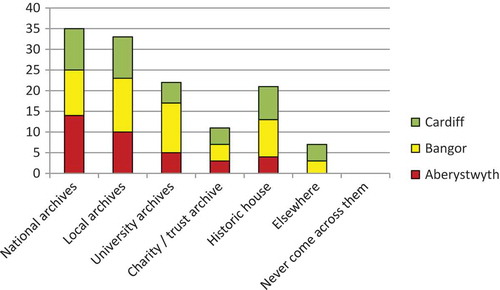

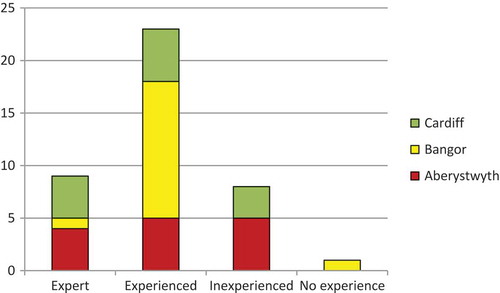

The one day workshops took place as follows: the National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth (21 April 2017), Glamorgan Archives, Cardiff (3 May 2017) and Bangor University (9 August 2017), and were attended by 17, 15 and 18 people, respectively plus the three members of the project team.Footnote56 Not all participants completed the questionnaire,Footnote57 but an indication of the profiles of attendees can be obtained from the following graphs

.Participants ranged in age from people in their 20s to over 70 (). Although the majority of participants were middle-aged or above, efforts were made to target younger people in order to obtain their views about the research potential of estate archives and discover whether they thought a toolkit could assist users of estate archives.

The bar chart above () indicates that each workshop was attended by people from a range of backgrounds with different types of expertise and perspectives. Information and research professionals, representatives from academia, as well as from the community were represented at each workshop. The final category called ‘other’ contained the following self-descriptions: conservation worker, estate administrator, trustee of the Welsh Historic Gardens Trust and volunteer researcher. Again, it was considered important to gather the views of a wide range of people when seeking people’s views on estate archives and their opinions about the structure and content of a toolkit.

Participants were asked where they had encountered estate archives (). The seven respondents who ticked ‘Elsewhere’ noted that they had come across estate archives at the British Library (2), in their personal collection, online, in solicitors’ offices (2), and in merchant companies. These locations together with the others named on the chart demonstrate the wide range of places where estate records can be found. Nobody stated that they had never come across them.

Only one respondent admitted they had no experience using estate archives, whereas most people claimed to be experienced users (). Again, it was useful to know that people attending the workshops came with different levels of experience and expertise.

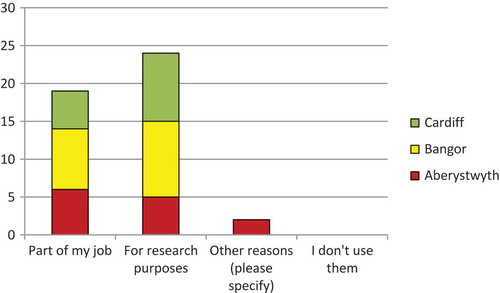

Participants were asked why they used estate archives (). Two people ticked ‘other reasons,’ stating that they used estate archives out of interest rather than for work or research purposes. Those that said they used them as part of their job included a student archivist, a place name researcher, a project worker linked to a specific estate, and someone who was writing the history of a particular estate. Participants who indicated they used the records for research purposes included people undertaking research into family/local/parish/estate/industrial and political history, academic research, researching historical parks and gardens, and the history of Grade I properties in Wales, as well as volunteering for a Regency project.

Summary of findings from group activities

Workshop participants were divided into pre-determined groups comprising a range of ages, experiences and background. As far as possible each group also contained one of the project team. The structure for each workshop followed the same basic pattern, as summarized in Appendix 2 but a different speaker was invited to each workshop to give a short presentation about their experience of using estate archives. The archive repository hosting each event provided photocopies of a selection of estate records for the group activity, Records in focus, to generate group discussion about the information to be found in these records, potential uses, and the information and skills required to effectively use them. A representative from each group summarized their findings and provided feedback to everyone at the workshop at the end of each activity. In addition, participants were given the opportunity to view some of the estate records held by the host, which led to further insights. The final hour was set aside specifically to discuss the desirability of creating an online resource to assist people use estate records, and to offer people the opportunity to make suggestions about its structure and content.

Short quotations and extracts taken from the data collected during each activity are reproduced in the tables below. They do not represent the full set of data by any means but provide a flavour of the nature of discussions during the workshops and insights obtained from the group activities.

Table 1. Group activity 1.

The first activity focussed on the value of estate archives (). Perhaps the comment ‘all human life is there’ sums up the wide-ranging nature of the material to be found in them and the multiple research opportunities they offer to many people. Also some suggested that in recent years there have been changes in the nature of researchers’ interests, which may affect the type of records being used.

Table 2. Group activity 2.

A number of broad categories of current users were identified by all groups in the second activity (), but potential users included people perhaps engaged in more specialized branches of research. Again, this may impact on the sort of estate records people are interested in using now and will consult in the future.

Table 3. Group activity 3.

The third activity () involved the distribution to each group of five photocopied examples of common types of records drawn from different estates held at the host repository. Working as a group, participants were asked to identify the records, if possible, and comment on the information they contained and ways in which it could be used. They were also asked to identify any barriers which could affect the use of these records. This was a particularly useful exercise and revealed some large differences in knowledge and skills between individuals and groups of users. It also confirmed the view that estate records are not always being used to optimal effect due to issues, such as language, unfamiliar handwriting, lack of context and condition.

Table 4. Group activity 4.

The next exercise built on the previous activity by revealing other factors which might potentially hinder the use of estate archives, including the availability and accessibility of finding aids which would enable users to identify the records required for their research (). Interesting it emerged that not all contributors were aware of some of the resources which are currently freely available online, such as the archive networks and the ability to browse various type of record creators on TNA’s Discovery.

The final hour of the workshop was devoted to a discussion about how to promote more widespread and effective use of estate archives. Everyone present was asked to state one thing they would like the toolkit to do/contain, which led naturally to an open discussion on the subject. Some of the ideas expressed during these sessions are summarized in .

Table 5. Open discussion.

There was widespread support at each event for the development of an online resource which would contain information and guidance of relevance to anyone using estate records. Although some of the suggestions made at various events are recorded in the above table, given the large number offered, it is probably not practical or possible to accommodate all of them. Instead, common issues/themes have been identified. Some can easily be accommodated, such as providing links to online cataloguing networks and guidance. Conversely, creating examples illustrating the sort of information which can be obtained from specific types of documents which will assist carrying out different types of research will take far more time and resources.

Feedback

Every participant was asked to complete a feedback formFootnote58 before they left the workshop. Responses helped to evaluate these sessions, as well as provide people with a further opportunity to comment on the proposed toolkit initiative. The results of this exercise are shown below.

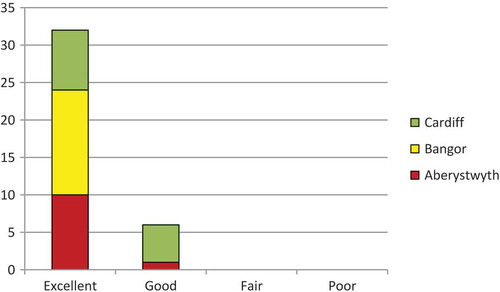

As can be seen in the chart above, the feedback from all three workshops was very positive ().

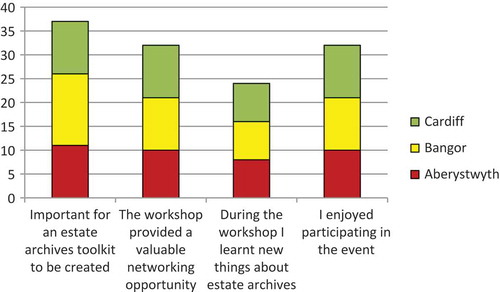

Thirty-seven (out of 41) respondents agreed that it was important for an estate archives toolkit to be created. Most (32) agreed that they had enjoyed taking part in the workshop, and that it had provided a valuable networking opportunity ().

Finally, people were given the opportunity to comment on the aspirations of ISWE generally and the toolkit project specifically. The following comments provide a flavour of the overwhelmingly positive feedback:

‘happy to contribute/co-operate further’;

‘I was left feeling very encouraged despite being very aware of how much I don’t know’;

‘the toolkit is an excellent idea and will be useful for archivists and researchers.’

The extracts cited above help to validate the case for creating an online toolkit for estate records. They also indicate people’s enthusiasm and wish to be involved in such an enterprise. Collaboration is essential to ensure such a resource is developed and adapted as necessary to reflect the needs and wishes of users and potential users.

Conclusion and next steps

The interest in, and perceived value of, estate archives can be confirmed by the willingness of people to give up their time to discuss the significance and value of the material within them, and explore ways in which it can be made more accessible to all. A purposive sample of estate archive users and custodians contributed to this project so the views expressed will not necessarily represent the opinions of all but strenuous efforts were made to ensure that the views of a broad group of people were recorded.

The three workshops were located deliberately in North, Mid and South Wales, in locations likely to be familiar to, and within easy reach of, the majority of people taking part. The profile questionnaire results indicated that the participants had come across estate archives in a range of settings, and they claimed to possess varying levels of expertise using them. Participants were of various ages, drawn from the community, academia and the information professions, and they used estate archives for research or work purposes or for leisure activities.

The activities that took place at the knowledge exchange workshops were deliberately designed to capture data concerning the significance of estate archives from different perspectives; and provoke discussion about current and potential uses of these records. When reflecting on the methodology employed in this research project, it was felt that things had gone according to plan and had resulted in the collection of a great deal of valuable data about estate records. In hindsight, perhaps greater efforts could have been made to capture the views of people employed by estates to carry out administrative or legal work.Footnote59 In addition, the emphasis of the project was very much on physical estate records rather than those which have been born digital.Footnote60 Considerations of ownership and Data Protection legislation mean that many of these records are not available to the public at present but further thought is needed on this subject if the toolkit is to be relevant to current and future audiences.

Notes made during the workshops were reviewed by the project team to identify common themes and issues. The results from this exercise were used to create a detailed blueprint for the proposed online toolkit, as shown below ().Footnote61 It was considered desirable that this resource would:

be easy to use and navigate by the audience, including postgraduate students, local and family historians, land managers, heritage curators, etc.

assist users prior to visiting the archive/whilst at the archive

provide information on the location of estate archives

include sections on different themes/subjects that can be pursued using estate records

feature record profiles (building on existing publications and guidanceFootnote62)

offer links to existing guidance and other resources, etc.

The next stage of this project is to identify funding opportunities that will translate the project findings into a workable resource which will be tested and refined via public participation workshops; and evolve over time in line with user needs.

On a final note, the purpose of the toolkit project was to explore ways in which the use of Welsh estate archives can be optimized. The ‘Wales’ nature of the toolkit will include particular types of record created in the context of the Welsh medieval legal systemFootnote63 and reflect the cultural, economic, social and geographical factors which give Wales its distinguishing characteristics. However, potentially this resource could have broader significance and applicability beyond Wales and the UK.

Acknowledgments

The project team would like to thank the ESRC for funding this project, and acknowledge the help and support provided by the Archives and Records Council Wales, the staff at the National Library of Wales, Glamorgan Archives, and Bangor University Archives and Special Collections. We would like to thank everyone who participated in the workshops or contributed to this project in other ways. Finally, we would like to thank the reviewers who offered constructive comments which have enhanced this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. White el al., “The Arrangement,” 1.

2. Royal Commission, Family Names A-K, x.

3. These holdings were originally ecclesiastical preferments later controlled by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners before the dis-establishment of the Church of England in Wales.

4. Lomas, Guide, 8, 65–66.

5. Crown Estate, “Wales Highlights 2017/18,” 2.

6. Duchy of Lancaster, “Southern Survey.”

7. White et al., “The Arrangement,” 1–8.

8. Discovery, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse.

9. Lomas, Guide.

10. For example, records and maps generated by the National Farm Survey (1941–1943) contain information about the ownership of farms and their management during World War II, complementing and enriching information obtained from specific estate archives. More information is provided about this survey material (MAF32 and MAF73) in the guide produced by TNA, http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/national-farm-survey-england-wales-1941–1943/.

11. North West Museums, Libraries and Archives Council, “Logjam,” 21.

12. Royal Commission, Family Names A-K, v.

13. See https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/supporting-collections-and-cultural-property/reviewing-committee#section-2 for more information on this subject.

14. The names of collections which have met the Waverley Criteria are listed in the ‘Cultural Gifts Scheme and Acceptance in Lieu’ annual reports produced by Arts Council England. Recent examples taken from the 2017/18 Report at https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/publication/cultural-gifts-scheme-acceptance-lieu-annual-report-201718 include the Grafton and the Cradock-Hartopp archives (pp. 64–65), which both feature estate papers dating from the early modern and modern periods.

15. Lomas, Guide, 9.

16. A list of the projects funded by the National Cataloguing Grants Programme for Archives in 2012 is given in the post by James Travers to JiscMail-Archives-NRA, 12 November 2014, at https://www.jiscmail.ac.uk/cgi-bin/webadmin?A2=ind1411&L=ARCHIVES-NRA&P=R14014&1=ARCHIVES-NRA&9=A&J=on&d=No+Match%3BMatch%3BMatches&z=4 The National Cataloguing Grants scheme is now a strand of Archives Revealed. For more information, please see http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/archives-sector/finding-funding/archives-revealed/cataloguing-grants/ .

17. King’s College, Cambridge, “King’s College.”

18. The National Archives, “Research Guide: Landed Estates.”

19. Manuscripts and Special Collections, Nottingham University, “Family and Estate Collections.”

20. National Records of Scotland, “Estate Records.”

21. Bedfordshire & Luton Archive Service, “Researching Garden History.”

22. Staffordshire & Stoke on Trent Archive Service, “The Sutherland Collection.”

23. Please see Discovery: Browse record creators: Family, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/c/family.

24. Please see Discovery: Browse record creators: Manor, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/browse/c/manor.

25. Examples include the Archives Hub at https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/ which helps to discover collections held by institutions of Higher and Further Education; Archifau Cymru / Archives Wales at https://archives.wales/ for archives held by certain Welsh repositories; and the Scottish Archive Network at http://www.scan.org.uk/ for archives held by Scottish repositories (as well as other online resources, such as a digital archive and access to online research tools).

26. For information about the Manorial Document Rules and associated legislation see http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/legislation/other-archival-legislation/manorial-documents/.

27. Cumbrian Manorial Records, http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/manorialrecords/.

28. Manorial Documents Register, http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/manor-search .

29. Inquisitions Post Mortem, http://www.inquisitionspostmortem.ac.uk/.

30. Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham, “Research Guidance,” https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/introduction.aspx.

31. Ibid.

32. The Country Seat, https://thecountryseat.org.uk/the-study/.

33. More information about this postgraduate course, which is offered via distance learning, is available at https://www.postgraduatesearch.com/university-of-leicester/55267330/postgraduate-course.htm .

34. For more information, please see University of Groningen, Courses: Historic Country Houses, https://www.rug.nl/research/kenniscentrumlandschap/hoofdpagina/onderwijs/colleges_historische_buitenplaatsen/colleges-historische-buitenplaatsen?lang=en.

35. ISWE, http://iswe.bangor.ac.uk/about.php.en Similarly, Maynooth University is the home of CSHIHE: Centre for the Study of Historic Irish Houses & Estates (https://www.maynoothuniversity.ie/centre-study-historic-irish-houses-and-estates). The Centre for Scotland’s Land Futures (Working together to investigate Scotland’s land issues, past, present and future) (https://scotlandslandfutures.org/) is run by Dundee, Stirling and the University of the Highlands and Islands. Finally, the Thames Valley Country House Partnership (TVP) (http://www.tvchp.org/) is a consortium made up of academics from Oxford University and staff working in a number of country houses located in the South East; its purpose is to promote and further research into country houses in that area.

36. YCHP: The Yorkshire Country House Partnership (http://www.ychp.org.uk/).

37. Details of a number of collaborative doctoral studentships on the themes of ‘From Servants to Staff: the Whole Community in the Chatsworth Household 1700–1900’ and ‘Serving the House and Housing the Servants: Understanding and Interpreting the Domestic Service Spaces in the North Wing at Chatsworth’ are available at https://history.dept.shef.ac.uk/collaborative-doctoral-awards-supervised-chatsworth-house-university-sheffield/ and https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/english/chatsworthserving respectively.

38. The Attingham Trust, http://www.attinghamtrust.org/ .

39. The records relating to many great estates are often in the hands of an estate administrator or land agent, making it difficult to obtain information of what is held in the first instance. Permission from the estate owner is required before anyone can see the records.

40. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Family Names A-K, xi.

41. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Family Names A-K, v.

42. See above 8.

43. Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts, Family Names A-K.

44. Historic Houses Archivists Group, http://www.hhagarchivists.org/ .

45. Marshall, “National Trust,” https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-43819762 .

46. ISWE, http://iswe.bangor.ac.uk/ .

47. Cumbrian Manorial Records, http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fass/projects/manorialrecords/index.htm and Research Guidance, University of Nottingham, https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/researchguidance/introduction.aspx.

48. More information about national policy on archives can be obtained from ‘Archives for the 21st Century,’ http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/archives-for-the-21st-century.pdf and https://gov.wales/docs/drah/publications/091203archives21stCenturyen.pdf .

49. AHRQ, “Toolkit Guidance,” https://www.ahrq.gov/research/publications/pubcomguide/pcguide6.html.

50. University of Aberdeen, “Toolkit,” https://www.abdn.ac.uk/it/services/toolkit.php.

51. Bangor University, “Bangor University ESRC,” https://www.bangor.ac.uk/research-support/esrc-iaa/index.php.en Research impact is defined by the ESRC as, “the demonstrable contribution that excellent research makes to society and the economy. ESRC, ‘What is impact?.’

52. Bangor University, “Bangor University ESRC,” https://www.bangor.ac.uk/research-support/esrc-iaa/index.php.en.

53. Please see Bryman, Social Research Methods, 138–142. For more about the issue of informed consent.

54. Please see Bryman, Social Research Methods, 263–264. For more information about the purpose of pilot studies.

55. The questionnaire was produced in English and Welsh. A copy of the English version is provided in Appendix 1.

56. Additional data about people’s perceptions of the value of estate archives and their suggestions for the design and content for the toolkit was gathered at the Spring meeting of the Ceredigion Local History Forum, entitled, Mansions and their Estates in Ceredigion, at Llwyncelyn, Ceredigion, on 22 April 2017.

57. Figures for each event are as follows: 14 out of 17 participants completed their questionnaire in Aberystwyth; 15 out of 18 in Bangor; and 13 out of 15 in the Cardiff workshop.

58. Feedback forms were available in English and Welsh.

59. Although there were 3 participants from this category, including one estate administrator.

60. Databases are commonly used for estate management purposes; increasingly estate records themselves are created in digital formats. For example, the diocese of Carlisle has made electronic versions of the Terrier and Inventory (a register of Church property) available online at https://www.carlislediocese.org.uk/our-diocese/other-resources/churchwardens.html. Users are permitted to alter them as necessary but requested to keep an updated electronic version as the master copy (as well as a print copy). Also, Ordnance Survey geographic tools are used by the Church Commissioners to manage the land and mineral rights held on behalf of the Church of England — please see https://www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/business-and-government/case-studies/church-commissioners-digitise-mapping-database.html .

61. The project team welcome constructive criticism on the proposed structure and content of the toolkit.

62. For instance, Alcock, Old title deeds.

63. For example, the tir prid had its origins in native Welsh law and differed from the forms of conveyance operating in medieval England (Carr, “This My Act,” 225.).

Bibliography

- AHRQ. “AHRQ Publishing and Communications Guidelines. Section 6: Toolkit Guidance.” Accessed September 20, 2018. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/publications/pubcomguide/pcguide6.html

- Alcock, Nathaniel. Old Title Deeds. 2nd ed. Chichester: Phillimore, 2001.

- Arts Council England. “Cultural Gifts Scheme and Acceptance in Lieu Annual Report 2017/18.” Accessed January 8, 2019. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/publication/cultural-gifts-scheme-acceptance-lieu-annual-report-201718

- Bangor University. “The Bangor University ESRC Impact Acceleration Account. ” Accessed September 20, 2018. https://www.bangor.ac.uk/research-support/esrc-iaa/index.php.en

- Bedfordshire & Luton Archive Service. “Researching Garden History at Bedfordshire & Luton Archives Service.” Accessed September 20, 2018. http://bedsarchives.bedford.gov.uk/PDFs/How-To-Research-Garden-History.pdf

- Bryman, Alan. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Carr, Antony. “This My Act and Deed’: The Writing of Private Deeds in Late Medieval North Wales.” In Literacy in Medieval Celtic Societies. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature 33, edited by H. Pryce, 223–237. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- The Crown Estate. “Wales Highlights 2017/18.” Accessed January 8, 2019. https://www.thecrownestate.co.uk/media/2593/250618_tce_en_welsh_report_web.pdf

- Duchy of Lancaster. “The Southern Survey.” Accessed January 8, 2019. https://www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk/properties-and-estates/rural-surveys/the-southern-survey/

- ESRC. “What Is Impact?” Accessed September 20, 2018. https://esrc.ukri.org/research/impact-toolkit/what-is-impact/

- HM Government. “Archives for the 21st Century.” Accessed September 20, 2018. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/archives-for-the-21st-century.pdf

- King’s College, Cambridge. “King’s College Estate Records.” Accessed September 20, 2018. http://www.kings.cam.ac.uk/archive-centre/estates-records/index.html

- Lomas, Elizabeth. A Guide to the Retention of Modern Records on Landed Estates. Letchworth, Herts: Hall-McCartney, 2007.

- Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham. “Family and Estate Collections.” Accessed January 8, 2019. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/collectionsindepth/family/introduction.aspx

- Marshall, Claire. 2018. “National Trust Should Be Radical, Says Hilary McGrady.” BBC News, Science and Environment, April 20. Accessed January 8, 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-43819762

- The National Archives. “Archives for the 21st Century in Action: Refreshed 2012-15, 2012.” Accessed September 20, 2018. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/archives21centuryrefreshed-final.pdf

- The National Archives. “Manorial Documents.” Accessed January 8, 2019. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/legislation/other-archival-legislation/manorial-documents/

- The National Archives. “Research Guides: Landed Estates.” Accessed September 20, 2018. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/landed-estates/

- The National Archives. “Research Guides: National Farm Survey of England and Wales 1941-1943.” Accessed January 8, 2019. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/national-farm-survey-england-wales-1941-1943/

- National Records of Scotland. “Estate Records.” Accessed September 20, 2018. https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/research/guides/estate-records

- North West Museums, Libraries and Archives Council. “Logjam: An Audit of Uncatalogued Collections in the North West.” Accessed September 20, 2018. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/Logjamfullreport.pdf

- Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. Principal Family and Estate Collections. Family Names A-K. Guides to Sources for British History Based on the National Register of Archives 10. London: HMSO, 1996.

- Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts. Principal Family and Estate Collections. Family Names L-W. Guides to Sources for British History Based on the National Register of Archives 11. London: HMSO, 1999.

- Staffordshire & Stoke on Trent Archive Service. “Welcome to the Sutherland Collection.” Accessed January 22, 2019.

- White, Philippa, Ruth Bagley, Elizabeth Cory, Malcolm Underwood, and Gareth Williams. “The Arrangement of Estate Records.” Journal of the Society of Archivists 13, no. 1: 1–8.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Profile questionnaire (English version only)

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR WORKSHOP PARTICIPANTS

1. What is your age group?

20s ◽ 30s ◽ 40s ◽

50s ◽ 60s ◽ 70+ ◽

2. How would you describe yourself? (Please tick all options that apply)

Academic researcher ◽ Archivist ◽ Conservator ◽

Curator ◽ Family historian ◽ General user ◽

Librarian ◽ Local historian ◽ Record agent ◽

Student ◽

Other (please specify)

3. Where have you encountered estate archives? (Please tick all options that apply)

National archive (e.g. National Library of Wales) ◽

Local archive (e.g. Glamorgan Archives) ◽

University archive (e.g. Bangor University Archives & Special Collections) ◽

Charity/Trust archive ◽

Historic house ◽

Elsewhere (please specify)

Never come across them ◽

4. What level of experience do you have of using estate archives?

Expert ◽

Experienced ◽

Inexperienced ◽

No experience ◽

5. Why do you use estate archives? (Please tick all options that apply)

Part of my job ◽

For research purposes (please give more detail)

Other reasons (please specify)

I don’t use them ◽

Thank you for your help. This information will help us produce a profile of all participants in the knowledge exchange workshops.

FEEDBACK QUESTIONS

1. Overall how would you rate the event? (Please tick one option)

Excellent ◽

Good ◽

Fair ◽

Poor ◽

2. Do you agree with any of the following statements? (Please tick all options that apply)

I feel that it’s important for an estate archives toolkit to be created ◽

The workshop provided a valuable networking opportunity ◽

During the workshop I learnt new things about estate archives ◽

I enjoyed participating in the event ◽

3. Were you satisfied with the organisation and delivery of the event?

4. How do you feel about the aims and aspirations of the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates?

5. Any other comments

Appendix 2. Summary of workshop activities

1. Group Activity 1: Significance (15 minutes)

What is the value of estate archives? 10 minute group discussion to come up with an agreed statement on the value and significance of estate archives, written out and presented by representative.

2. Group Activity 2: Use (30 minutes)

a) Existing: How frequently are estate archives being used? By whom? What for?

b) Potential: What opportunities are there for estate archives to be used differently, by a wider range of users, to contribute to new or emerging agendas?

3. Guest Speaker (30 minutes)

4. Group Activity 3: Records in focus (45 minutes)

N.B. Each group handed a pack of photocopies of a range of estate records for this task

a) Insights: What is this record, what information does it contain and in what ways could it be used?

b) Barriers: What skills and/or information do you need in order to understand this record?

Is there anything about this record which may makes it difficult to access, identify, read or understand?

5. Group Activity 4: Discovery, access and use (45 minutes)

What issues do users of archives face in their attempts to identify, locate and use estate archives?

What issues do archivists face in their attempts to make estate archives accessible to users?

6. Exhibition of estate records (30 minutes)

7. Open Discussion: Toolkit suggestions (60 minutes)

What information/guidance/resource would it be useful to include in an estate collections toolkit?