ABSTRACT

This paper applies the methodological premise of the ‘social life of things’ to give insight into the context and movements of a collection of records found at the Norwegian National Archive, that contribute to the documentation of the Armenian Genocide. A study of the life of this collection tells the story of Norwegian missionaries in the Ottoman Empire in 1915, their witnessing of the Genocide and the subsequent activations of the records. It explores the use and impact of these records in Norway, which have led to international collaborations for the historical memory of Armenia and acknowledgement of the Genocide, taking a different political stand to that of the Norwegian government. Nevertheless, silences have been encoded in the making of the archives, the making of narratives, and at the moment of retrospective significance. It highlights the circumscribing predominance of national narratives to documents and raises questions about the silences in other missionary archives in Norway.

Introduction

In the early 2000s,Footnote1 documents surfaced at the Norwegian National Archive (from here on Riksarkivet) of a Norwegian missionary nurse living and working in the Ottoman Empire in 1915.Footnote2 As a member of the missionary organization Kvinnelige Misjonsarbeidere (KMAFootnote3), Bodil Biørn travelled to the Ottoman Empire in 1905 where she lived on and off until 1925.Footnote4 Biørn and her KMA colleagues recorded their work with the use of photography and texts capturing moments of this period, from the early 1900s to the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide. Laying quiet in Riksarkivet for many years, these records suddenly became the centre of attention after their discovery and 2005 exhibition by senior archivist Vilhelm Lange called Norwegian Women Document Genocide. Riksarkivet’s use of the term genocide was ‘controversial’ in that it went against the Norwegian government’s official position of not acknowledging the events as genocide. Nevertheless, Lange’s exhibition produced collaborations mainly focused on helping to contribute to the historical memory of the global Armenian community by working against the negation of the Genocide.

The paper builds on, and is inspired by Michelle Caswell’s use of the social life of thingsFootnote5 to give insight into the social and human context of a collection of records and the consequences of its movements,Footnote6 of creation, capture, organization and pluralization. The social life of things is used as a methodological tool for looking at the circulation of Biørn’s records in a variety of ‘regimes of value’ and the meanings that are projected onto them, their uses, their trajectories and silences.Footnote7 The Bodil Biørn collectionFootnote8 is referred to as ‘records of trauma’ as it contains affective aspects carrying within them collective trauma and, to paraphrase Haugland Sørenson, ‘haunted images’Footnote9 of the Armenian Genocide.

The paper starts by giving an account of how the records were created, adapted, then institutionalized and finally activated, all for different reasons, producing during this trajectory, which is not necessarily linear, silences and contestations. This paper shows how a document is ‘a powerful resource for constructing and negotiating social space’.Footnote10 These negotiations of social spaces are perhaps more poignantly demonstrated when the events are contested, such as with the Armenian Genocide. The lives of records are framed and deployed in different directions amid contestations. Caswell uses Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s framework to understand the silences encoded in historical production at four key moments: ‘the moment of fact creation (the making of sources); the moment of fact assembly (the making of archives); the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives); and the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance).’Footnote11 Whilst not all silences nor trajectories in the life of this collection can be mentioned nor documented here, the aim is to document the main activations and narratives surrounding this collection and the impact they have had, focusing on Riksarkivet’s role as a central actor in the collection’s life. Answering the question of how these records have been deployed in Norway may tell us about how Norway responds to records of its missionary past. Caswell’s framework, which helps look for encoded silences in the life of a collection, is useful for understanding records of trauma, as power is a decisive factor in historical production deciding which stories get told, by whom, how, and which stories are forgotten. These silences help tease out relationships of power and in this case are particularly useful to understand the narratives surrounding a case of Norwegian missionary records which also document a Genocide. Examining the making of the records, the making of the archives, the making of the narratives and then the moment of retrospective significance, helps understand what the focus in the discussion on these records is, has been and what is missing.Footnote12

Capturing the moment

The KMA work in the Ottoman Empire began in 1901 when missionaries travelled to take care of the orphan children left from the large-scale massacres of Armenians in 1894–96.Footnote13 Bodil Biørn travelled to the Ottoman Empire in 1905 settling in Mush in Eastern Anatolia, a region which was designated by mapmakers outside the empire as Armenia.Footnote14 Just like the term Kurdistan, the term Armenia was used simply to refer to the land inhabited by Armenians.Footnote15 The term supported a claim of a people to a territory that linked six provinces (Erzurum, Van, Bitlis, Sivas, Diyarbkir and Mamuretülaziz) which had been home to Armenian kingdoms and principalities for more than 1000 years.Footnote16

Documentation before 1915

With the aid of her personal camera, Biørn documented her work with the local community, the places she visited, the people she met, and her life in general. Biørn’s photographs are initially compiled in photographic diaries, where she writes the name of the people she is photographing, the places, the date and in many cases the context. The photographs cover a spectrum of images that fall into categories: landscapes, buildings, groups of people she meets on the road, families working for the mission stations or attached to one of the KMA units of care (orphanage, school or health centre), the orphans, the widows, the starvation. Most of the photographs are of people, both adults and children. These images can be classified as portraits, as they mostly depict the people posing for the photographs. A small number portray starving children lying on the streets of Mush or standing looking at the camera.

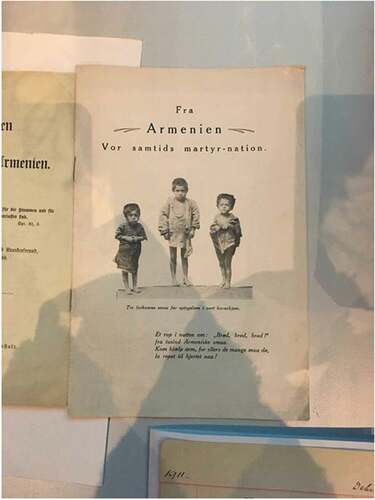

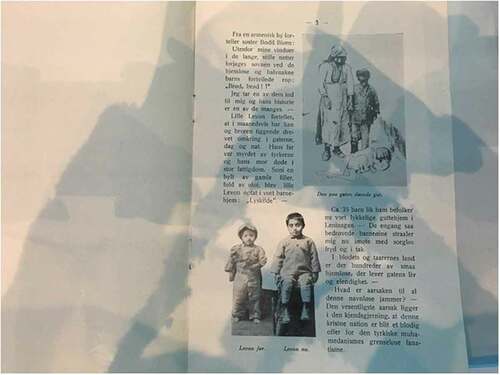

Biørn’s photographs served the purpose of raising funds abroad, similar to the contemporary use of photographs in charities and non-governmental organizations. Biørn would take portraits of the children in extreme poverty which would then be printed on pamphlets describing the destitution, the work that was needed and the work that was being done (). Biørn would then capture the improvements made with the funds raised ().Footnote17 Alongside the photographs, the missionaries wrote letters about their daily lives which were published in the organization’s international newsletter Kvartalshilsen.Footnote18

The nature of all these documents, photos and correspondence, changed during Biørn’s stay in Mush. Whilst at first they were for recording destitution, raising funds, and disseminating the results of the Mission’s work, in 1915 they became a way to record the victims of genocide and inform the outside world.

The Genocide

In 1908, the Young Turks staged a revolution against the autocratic rule of sultan Abdul Hamid (1876–1909).Footnote19 The Ottoman Empire had already created an institutionalization of violence against the Armenians, and the Young Turks embraced ‘an exclusivist ideology of Turkism’ that embraced long-standing racial and religious prejudices dating back to the Ottoman Empire.Footnote20 Built onto this were a number of intersecting reasons laid out by scholars such as Adalian and Hovannisan who explain the reasons for the Genocide: the internal failures to address non-Muslim needs and protections, which led to demands and appeals by the Armenians both to the Turkish authorities and foreign powers. This invited further resistance, suspicion and intransigence from the Turks. Social and political discontent was met with increasing violence, and as external and internal threats towards the regime increased, a cycle of increasing brutality grew.Footnote21

Beginning in April 1915, what the Turkish authorities euphemistically called ‘the resettlement policy’ dictated the mass deportation of Armenians from their homeland, which together with execution and starvation, constituted and resulted in their genocide.Footnote22 There is a considerable amount of literature and documentation that confirms and explains the Genocide in more comprehensive and sophisticated manner than I can possibly do here: the deportations and annihilation campaigns, the interrogations and torture, the extermination camps and the fate of women and girls.Footnote23

In 1915, Biørn was running Deutsche Hülfbund’s policlinic in Mush, which was an orphanage for boys and a day-school for girls.Footnote24 All foreigners were told to leave the area before the killings began. Yet Biørn and her colleague Alma Johansson stayed, as Biørn had caught typhoid fever and was bedridden.Footnote25 Biørn witnessed the arrests, deportation and massacring of Armenians at the hands of the Turkish authorities.Footnote26

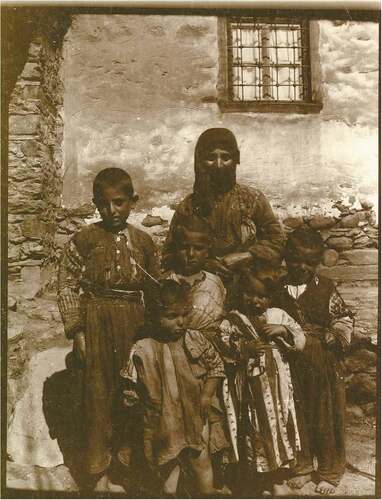

Biørn attempted to corroborate the atrocities by using her photographs as a medium through which to show who the victims were. The pictures taken during her years working and living in Mush were copied (presumably by Biørn herself), and a new text was added with the names of the people, dates and their eventual deaths. Whilst an entry in her diary before 1915 described the people in the photograph as ‘The widow Heghin with her 5 sons’, an unpasted copy of the same photograph was later amended to add ‘Heghin with her 5 sons, two were received in our orphanage. They were burnt in their house during the murders in Mush in 1915. She helped us in the orphanage with her son. She was a good woman of faith’ ().Footnote27

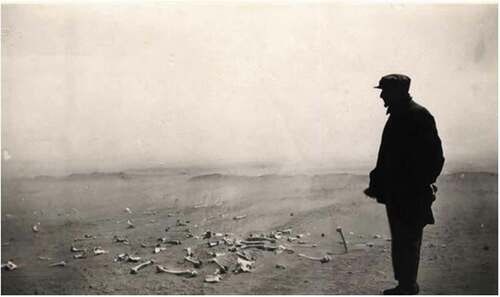

The original photographs Biørn took were converted once the Genocide was taking place, into a form of identifying the victims. Not only were copies made of the original portraits with a different text on the back, but photographs taken by others (it is not known by whom) were edited by Biørn by adding text to explain what had happened ().

Figure 1. ‘Here is the class from the day-school with teacher Margarid… I had for many years a day-school in Mush. The teacher Margarid Nalbanchiani and most of the 120 children were murdered in 1915ʹ. Source: Riksarkivet Norge, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Wikimedia_Norge_Bodil_Biørn_project#/media/File:Kvinnelige_Misjonsarbeideres_arbeid_i_Armenia_-_fo30141712200036.jpg.

Figure 2. ‘Heghin with her 5 sons, two were received into the orphanage. Burned in their house during the murders in Mush in 1915. Helped us in the orphanage with her son. She was a good woman of faith’ Source: Riksarkivet Norge, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Wikimedia_Norge_Bodil_Biørn_project#/media/File:Armenisk_enke_med_barn_-_fo30141712180002.jpg.

Figure 3. ‘Our Armenian helpers, of whom 6 were murdered in the massacre of the times in 1915. Musch’ Source: Riksarkivet Norge, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hjelpearbeidere_og_misjonærer_-_fo30141712180008.jpg.

Figure 4. ‘The Armenian leader Papsian removes the last remains after the gruesome massacre at Der ez Zor in 1915–1916. The other bones have been washed away by the Eufrates’ (Anonymous). Source: Riksarkivet Norge.

Figure 5. Biørn’s fundraising pamphlet ‘Armenia our current martyr nation: Three small exhausted children before admission into our orphanage’. Source: Riksarkivet Norge.

Figure 6. Biørn’s pamphlet where she tells the story of ‘Little Levon’, taken in by her orphanage and pictures him before and after: ‘Levon før’ ‘Levon nu’. Source: Riksarkivet.

Presented here are only six photographs. The entire collection has been digitalized and can be found both on the Riksarkivet websiteFootnote28 and Wikimedia NorgeFootnote29 which have published the photographs along with the text. The texts at the back of the photographs or written on the pages of the albums or diaries are short and descriptive, never claiming to speak for the victims, yet humanizing them by informing us of their identity and calling attention to an atrocity. The photographs depict the extermination of people through starvation and deprivation, as well as the faces of future victims ‘returning the gaze’,Footnote30 in their daily routines or posing for a picture.

The organization’s international newsletter Kvartalshilsen, which printed the correspondence of missionaries, provides the context of what was happening in the different missionary locations. Kvartalshilsen no.4 1917 includes a letter where she describes a meeting with an Armenian parliament minister from Mush. She quotes the minister:

“think of all the women and children that were murdered, burnt and (raped) and thousands thrown into the rivers, it is awful to think that our people have been nearly destroyed”. Even though it was better in Constantinople than in other places, thousands of Armenians have been exiled or killed, but from the small villages most were sent to Asia Minor or to the desert and most of the men and boys were killed along the way.Footnote31

Described in the correspondence are the reasons behind the starvation, the sickness and the levels of deprivation experienced.Footnote32 These records corroborate the strategic massacre of Armenians by the Turkish authorities and became Biørn’s educational tools during her later years, when she travelled around Europe giving lectures about the Armenian people, their culture and what she had witnessed.Footnote33

Creating records for different purposes

The nature of the photographs in this collection reveals the fascination at the beginning of the century with the technological possibilities, the confidence and imperial vestiges in the way they are taken. Were they taken with consent? If they were, did the people know what they were consenting to? Photography is affiliated to systems of power haunted by what Sekkula calls, ‘bourgeoise science’ and ‘bourgeoise art’ which produce underlying tendencies in the history of photography that ultimately produce an objectifying commodity.Footnote34

There is a strong element of power at play in the relationship between the Armenians and the missionaries due to the dependency that is born from extreme needs and their educational and ethnic differences. Just as colonial systems were archive-dependent, so are missionary systems with their need to report to the head office, keep records of their projects, numbers, funding and experiences. E.L.Jenkins writes that, ‘Missionary photographs comprise a distinct category of colonial cultural production’.Footnote35 The documents described here were meant for public consumption in Scandinavia, to report to the head office, raise funds and share the progress with the Christian community. The important question of how the subjects responded to the depictions of themselves is never answered.Footnote36 These records at this point are the commodities of a Christian mission.

Nevertheless, Biørn repurposes those records during the Genocide to raise awareness outside the Ottoman Empire as to what is occurring. Even though the correspondence and photos were destined for the KMA in Norway there is an urgency in her letters and her actions as she used bible code to bypass Turkish censorship and had many of the records smuggled out of the country. Studying Okkenhaug’s work on Biørn, it is likely that Biørn had hoped more would have been done by foreign powers with the news of what was occurring. The prayers for the people expressed in her correspondence intertwine with her descriptions articulating a call for help that is not only directed to the readers of the newsletter, but to God as well. On the whole the impression is that Biørn’s articulations are for anyone who can listen and help. Biørn’s feeling are very present in her correspondence and articulate a close tie to the Armenian population that goes beyond her religious discourse.Footnote37 Biørn’s adoption of a small orphan boy during this period, as well as the following 30 years dedicated to the Armenian cause and commitment in securing the survival of the Armenian nation,Footnote38 testifies to her commitment and familiar relations to the local community.

The photographs taken walk a narrow path between the discourse of the Christian mission on the one hand, and Biørn’s personal concern and compassion with fellow human beings on the other. Biørn’s written records flesh out the photographic depictions and the victims whom we can now acknowledge when we talk about the Armenian Genocide. ‘Atrocity images’ of mass bodies do not necessarily lead people to ask about the individuals represented. Crane argues that on the contrary atrocity images, where the value is in the shock and revulsion, have led to an incapacity to absorb what has occurred.Footnote39 In Biørn’s images, the descendants can identify the victims and we remember them alive through the identities that are given life through Biørn’s correspondence. Nevertheless, her records stayed within the uses and aims of the KMA mission for nearly three quarters of a century.

The Making of Archives and Narratives

After Biørn’s death in 1960, the use of these records ended as they became buried in the KMA archive. When the KMA dissolved in 1983, their archive was offered as a gift to Riksarkivet. It included 1379 photographs, many taken by Biørn, Biørn’s personal photo album and diary, the correspondence of missionaries from around the world to the organization’s newsletter, loose photographs, slides, the fundraising pamphlets and the organization’s account book. It is difficult to know how ‘complete’ the collection is, how many photographs were kept privately by Biørn or how many were damaged or destroyed.

Riksarkivet

Between 1983 and 2005 Riksarkivet arranged and catalogued this material, yet the result of this cataloguing meant ‘no one knew what the fonds contained’.Footnote40 The archival description had not mentioned the Armenian Genocide, concentrating instead on the institutional creator, the KMA.Footnote41 The little knowledge at Riksarkivet about what lay behind this material meant little to no use of them before 2005.

In early 2000s, a senior archivist at Riksarkivet received a telephone call from Biørn’s grandson inquiring whether the archive had documents pertaining to his grandmother. The query led the archivist to the KMA archive. Some time later, the same archivist heard a radio interview where a man described his grandmother’s work as a nurse in the Ottoman Empire during the first decades of 1900. There, his grandmother adopted an Armenian orphan boy who was to become the father of the man being interviewed. The impression the interview left on the archivist prompted him to investigate further.Footnote42 It was at this point Biørn’s photographs were ‘discovered’.

This led to a more detailed arrangement and cataloguing of the records and an online exhibition a year later in 2005 called ‘Norwegian Women Document Genocide’. The exhibition, published in both English and Norwegian, consisted of photographs taken by Biørn and other anonymous sources, of the places and people affected by the Armenian Genocide. It included a photograph of an Armenian refugee camp in Aleppo, Syria, a photograph of the founders of the KMA, photos of the missionaries at work, including Biørn, but mainly the photographs were of the Armenian population in Mush with the text that Biørn wrote after the Genocide. The exhibition also included a copy of the organization’s newsletter Kvartalshilsen from 1907, a map of the Ottoman Empire and the UN’s definition of Genocide from the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention) of 1948.

The exhibition was put together through a process of selection, to tell a story. Due to the nature of the documents the archive had, it was the story of the missionaries, not the victims. The story of the missionaries however led to the larger story of the Armenian Genocide and the possibility of acknowledging the victims. This was significant because the Norwegian government at that time (and to this day) has not acknowledged the 1915 events as genocide. The official Norwegian argument as to why, follows the exact same lines made by the Turkish ambassador (see below) and the Turkish lobby internationally.Footnote43

It was a serendipitous find by an archivist who had an interest in photography and a knowledge about history.Footnote44 The silence of these records during roughly 20 years at Riksarkivet was not a deliberate policy, but the result of obscurity at the level of description. The KMA archive was received by Riksarkivet for being a significant national institution but its contents were not investigated even though the geographical reach of the Norwegian missionary work is generally well-known in Norway. Biørn’s records and the story behind them were buried for years due to the archival description (or lack of it), being anchored to the traditional concept of provenance, the creator of the collection, excluding thus the documented community. Questions arise here as to whether there is enough research into the contents of important missionary fonds in Norway and their role in documenting mass violations in other countries and how these fonds are being indexed.

Using the G-word

After the online publication of the exhibition, Riksarkivet received two letters from the Turkish Embassy in Oslo stating that the term genocide in the context of this exhibition is misused. That whilst tragic events did occur during the First world war on the territories of the Ottoman Empire it is ‘not a historical fact that these events can be labelled as “genocide”’.Footnote45

The senior archivist replied that they were not willing to omit the term from the text for three reasons: first, it is supported by internationally recognized historians; secondly, they follow the same line of reasoning of historical events as the United Nations and the European Parliament, ‘in both cases grounded in international law and professional historical research; and thirdly, due to the respect for the personal evidence contained within the archival material itself (…)’.Footnote46

The ambassador’s reply was to reiterate that the resolutions made by some parliaments are, ‘decisions taken with political considerations and not based on international law and professional historical research’.Footnote47 That the National Archive should differentiate between what the records say occurred from what is officially accepted or recognized as having occurred, in this case, the Norwegian government’s position towards the events. Due to the National Archive being a government entity using the term genocide ‘will be understood as the official view of the Norwegian Government … we believe that it would be more appropriate if the National Archive refrained from using a controversial wording … ’.Footnote48

The title stayed and Riksarkivet began collaborative efforts with Armenian stakeholders, Norwegian researchers and international groups that resulted in copies of the records in the Biørn archive being sent around the world. The 2005 exhibition on the Riksarkivet website created enough interest, collaborations and reactions that Vilhelm Lange gave a lecture in 2008 presenting the original 2005 collection, and the context of these records.Footnote49 Lange included a short problematization of the use of the term genocide in this context, explaining what the Norwegian government’s position was regarding the use of the term, and yet how the institution chose to use the word regardless of the government’s position. He noted how the use of this word to some may not have particular importance or meaning, yet to others is of enormous significance.Footnote50 He also described his personal affectations and emotions as a result of working with the records. Rather than distancing himself from the documents, Lange talked about the distress caused by the visual evidence of suffering and the impact the documents had on him.Footnote51

The choice of the term genocide for the Norwegian exhibition was not a neutral decision by the archivist. However, choosing not to use the term would not have been a neutral decision either. His choice of words was supported by the State Archivist at that time and the Ministry of Culture who were consulted.Footnote52 The choice of using the term genocide reflects a desire by an archivist to support not only the agreed view of specialist scholars, but that of the victims and families of victims.

In 2015 however, with the centennial of the Genocide, the word Genocide was taken down from the website and the centennial was commemorated with the term Massacre instead. This instruction came from the state archivist at that time, with the explanation that the increased attention to this subject during the centennial would cause more ‘controversy’. Riksarkivet reinserted the term Genocide once again in 2018. However, neither the 2005 exhibition, the 2008 lecture, nor the digitalization of the records by Wikimedia, made any impact in the Norwegian press. The press did cover the centennial of the Genocide in 2015, emphasizing the official Norwegian position of not acknowledging the events as genocide and noting the Norwegian government’s rejection of the Armenian invitation to mark the centennial.Footnote53 Much of the press called upon the government to recognize the Genocide, some of which used Biørn’s photographs to help describe the 1915 events.Footnote54 Yet the exhibition was not mentioned in the mainstream media, nor did it receive any attention by public officials. By 2018, when the word ‘Genocide’ was reinstated on the Riksarkivet website, the Norwegian media and political attention towards the question of the Genocide had abated and remains on the margins to this day.

Whether these documents are evidence of genocide or not is not the argument of this paper. This collection is part of an ever-growing global archive that does confirm genocide. ‘The Armenian genocide is the second most researched genocide after the Holocaust, and there is not only a consensus among historians, but also among genocide scholars (including legal scholars) that the crimes can be qualified as genocide’.Footnote55

Riksarkivet’s use of the word was the decision of one archivist who received institutional support up until increased public and state scrutiny was imminent. The question of ‘controversy’ over the word arises due to the success in lobbying efforts of those who deny the events, by applying a strategy of projecting that there is an ongoing scientific debate in an attempt to mask that it is a political strategy. In circles where there is little specialist knowledge about genocide there can easily be the impression that the Genocide is still a debatable fact.Footnote56

The decision on the side of the archivist to use the word reflects a growing international and cultural shift regarding perspectives on the Genocide, where it is increasingly recognized, as well as the growing recognition that archives have a duty to historical justice. In this particular case it has resulted in the faces and names being known, the denial of a genocide can be seen, and younger generations can be educated.Footnote57 Nevertheless, it also reflects the institutional limitations that archives have to contribute to political debates, depending on media and the public mood, existing as they do usually outside the public view,Footnote58 whilst simultaneously being contained within larger political structures that may restrict efforts towards social justice. The contributions to historical accountability that have been made in this case have come from collaborations and projects through personal connections or communications with people and organizations who have a stake in the records.

Collaborations

The two most significant collaborations have been with Wikimedia and the Armenian Genocide Museum in Yerevan. However, significant art projects have resulted from Biørn’s photographs such as the documentary film A Map of Salvation, by the Armenian director Aram Shahbazyan, which uses the records to tell the stories of several young missionary women in the Ottoman Empire, including Biørn and Johansson.

The art project ‘Red Hail: because it never ends’ developed by the Eiva Arts Foundation on the centenary of the Genocide focuses on, and reinterprets, one of Bodil Biørn’s photographs: the photograph portraying a group of girls with Norwegian dresses and dolls, lining up in rows called ‘Some of our little girls with dolls’.Footnote59 Red Hail recreates the original photograph with a new group of girls, building a new collection of contemporary photographs of mirroring images taken by Armenian photographer Vahan Stepanyan. The book tells the story behind the original photograph when Biørn raised funds one Christmas to buy dolls for the girls at the orphanage. After the Genocide, Biørn searched for the girls in the photograph, discovering that none of them survived. This story is narrated both in the book and the film (included at the back of the book) by Biørn’s grandson Jussi Biørn.Footnote60

Within Norway there have been increased publications and discussions around Biørn’s work as an example of the gendered side of missionary work and the empowered role of women at the turn of last century during atrocities.Footnote61 This discussion has been taken up by Wikimedia who have teamed up with Riksarkivet for conferences around the world to show the gender gap in Wikimedia and the importance of women’s stories in history.

Wikimedia

In 2017, the Arts Council of Norway (Kuturrådet) funded the digitalization of all Bodil Biørn’s photographs and texts, recognizing the importance of these records, both nationally and internationally. The digitalization project was a collaboration between the Riksarkivet and Wikimedia Norway. The collaboration led to a further collaborative project with Wikimedia Armenia. The Wikimedia page includes a link at the top of the page to Bodil Biørn’s biography on Wikipedia.Footnote62 Underneath are all the photographs from her collection and alongside is the corresponding text in the original Norwegian, followed by an English and Armenian translation.

On the Wikimedia page however, Biørn’s process of amending the records and the transformation that the records go through disappears. Gone are Biørn’s handwritten notes behind the photographs repurposing the records thus blurring her personal connection to the moment. Silences are produced during this transformation of the records into digital records. Online the most descriptive caption (post-Genocide) has been selected but it is not part of the photograph as an object any longer. The albums have also disappeared and so have the small rectangular boxes full of slides which Biørn used for her lectures on the Armenian people, which were so crucial to the fundraising.

The digitalized newsletter Kvartalshilsen is published on Wikisource, yet each issue must be searched for individually in the Wikisource search box, which means it does not have its own index page.Footnote63

The Genocide Museum in Yerevan

The Genocide Museum in Yerevan received Biørn’s photographs through a personal exchange with Vilhelm Lange. The records became an integral part of the physical and digital collection of the Museum. The Museum exhibition text gives a different context to the records, pointing to Biørn’s efforts at saving victims and her importance as a historical figure for the Armenian collective memory. The exhibition describes Biørn as a witness but also as a ‘messiah’.Footnote64 The focus of the records in this context is as documentary truth about the Genocide. Their project 100 Photographic Stories About the Armenian Genocide displays in their words,

partly known and unknown photos, which bear unique conceptual and iconographic information on the Armenian Genocide as an irrefutable evidences of the crimes committed in the Ottoman Empire against humanity and civilization (…).Footnote65

In this context, the collection becomes central to the cause of the Armenian Museum as, ‘irrefutable and undeniable proofs to condemn the heinous crime, to ponder on the elimination of its consequences, to speak and act, and to prevent such crimes in the future’.Footnote66 Not only are they evidence of genocide but evidence of the denial and the political challenges associated with this debate. The Armenian-Norwegian collaborative efforts resulting in the collection of Norwegian documents at the Genocide Museum in Yerevan is a new purpose for this collection as documentary support to pursue an official recognition of the Genocide.Footnote67 This aim is part of the identity of the international Armenian community.Footnote68

Silences and the national frame of reference

The social life of this collection has exposed silences not only in the records (the victims that were not depicted nor named), but silences at the moment of creation of the archive at Riksarkivet, the narratives surrounding the records and at the moment of retrospective significance regarding the Genocide. The initial indexing of the records at Riksarkivet failed to mention the Genocide because there was no knowledge of what the KMA archive actually contained. In the words of Simon Fowler they were ‘hiding in plain view’.Footnote69 The serendipitous nature of their discovery raises questions regarding the frame of reference in cataloguing practices around missionary archives in Norway.

Biørn’s photographs have been reproduced in newspapers and books in Norway since then, yet the conversation surrounding these records has mainly centred around Biørn’s role and less about the debates on the Genocide and Norway’s lack of acknowledgement. As with the exhibition in 2005, her story includes that of some of the victims, but these are ‘whispers’ as Caswell would call them.Footnote70 As worthy as it is to celebrate her heroism, if Biørn was alive today she would probably be lobbying the government to recognize the Genocide. The narrative of Biørn and her heroism easily becomes a commodity of the Norwegian nation to tell the congratulatory and benign story of the Norwegian mission abroad, whilst continuing to tow the Turkish line. It means that at times (in conferences, on the website and in the catalogue) Biørn’s narrative obscures that of the Genocide.

These very same records at the Armenian Genocide Museum also celebrate Biørn’s heroism as well as that of other missionaries and Fridtjof Nansen. In that context however, the purpose is the call for the global recognition of the Genocide. This again is tied to a sense of national identity, which proves Edensor’s point that documents tend to end up epistemologically and ontologically belonging to a nation.Footnote71

There seems to have been a lost window of opportunity during the centennial to create greater public engagement with the records and debate on the Norwegian lack of acknowledgement. The Armenian community in Norway, which has kept the issue of the Genocide alive in the Norwegian press, did not write about Riksarkivet’s exhibition of Biørn’s documents nor the Turkish complaints, which begs the question to what point were they involved in the making of the exhibition or the mediation of the records? Biørn’s grandson, however, has been a central figure behind the records, donating many private photographs and items to both the Museum in Yerevan and Riksarkivet. He has become a bond between the two countries and a link between people and institutions. He continues working for the Armenian cause and adding to the Biørn collection, which in turn adds to the global Armenian Genocide archive. This ‘community of records’ attests to the agency of the Armenian community behind the growth of the archive and spread of the documents.

Nevertheless, the impact of the records for a politics of human rights is closely entwined with the narrative of the nation state, whether it is Norway, Turkey or Armenia. Riksarkivet strategically deployed the records for uses in contexts that ‘perform human rights by memorializing the dead’,Footnote72 and attempts to bring about some historical accountability through the mediation of these records and the story of Genocide. However, Norway still finds itself caught in the trap of ‘controversy’ over the Armenian Genocide, thus the gap between the position of Riksarkivet and the Norwegian government, and the removal of the word from its website in 2015–2018. Officially, Norway is falling behind the growing global recognition of the Genocide. Unofficially however, its National Archive has moved, to a certain extent, beyond the national political framework to recognize the Genocide through its collaborations. Archives are restrained in their extent to which they can overcome national discourses and national politics due to the epistemological hold of national narratives, particularly within national archives. However, national archives can go beyond the national narratives through their involvement with communities of victims, families of victims and the descendants of atrocities where they can contribute the most to human rights justice.

Like all records, Biørn’s archives have a shifting frame of reference, becoming signs of communities’ own historical and geographical context.Footnote73 They have become a form of shared solidarity, they depict a moment of shared history between Norway and Armenia, they depict a sense of injustice, as well as a sense of a nation, both for the Armenian and the Norwegian community.

By understanding the collaborative and mediation efforts of Riksarkivet despite the Turkish pressure we see that Norwegian refusal to recognize the Genocide is neither deep-rooted nor ideological as it is in the case of Turkey.Footnote74 Riksarkivet’s position would not have been possible without the consent of the Ministry of Culture. Lange’s work and the work of current archivist Per Kristian Ottersland are contained within the institutional space that is the National Archive of Norway, which exists within the larger narrative and politics of the nation state. Yet through their collaborations, activations and uses, they are able to bypass the national framework to a certain extent, making sure the records become ‘touchstones’ for remembering, witnessing, and commemorating,Footnote75 responding to the needs of a different community, the descendants of genocide.

Yet the serendipitous nature of Lange’s finding reveals that more must be done in Norway to explore the archives of Norwegian missionary organizations and rethink the indexing of these collections. Norwegian missionary movements extended from East Africa to Madagascar and were present during atrocities, which as the case documented here shows, will carry the identities of the victims and their lives, regardless of who created the records.

Conclusion

The life of this collection of records attests to the centrality of a ‘community of records’ in determining the life of a collection even though national narratives are never far from the life of any document. This case shows that records sustain and transcend national boundaries simultaneously and national archives have a role to balance this in favour of historical accountability and human rights practice. Nevertheless, national archives will always be politically limited by their institutional functions as national structures. It is rather transnational communities of the records that network to socialize institutional change by weighing in on the side of the victims. The activation of records and the decisions of an archive and its parent organization reflect the values of the wider society. The silence of this collection from the time of Biørn’s death in 1960 up until their ‘discovery’ in Riksarkivet in the early 2000s reflects the period in which the world ‘fell into an apathetic silence over the Armenian genocide’.Footnote76 The growing interest in these records reflects the fast growing interest in and acknowledgement of the Genocide, the spread of digital records, and the fact that the memory of the Genocide is strongly linked to the identity of the Armenian community.Footnote77 It also attests to the fact that documents on the Armenian Genocide are found in archives around the world and contribute to the ever-expanding knowledge about the 1915 events.

The value of this collection is in the accumulative contribution to accountability, the memory of the victims, and as an exemplification of other stories still dug deep in archives. The impact of this collection, I would argue, could have been greater if media attention would have been given to the exhibition, to the use of the word genocide, or to any of the activations that have come about due to Biørn’s records. The issue of the Genocide, however, is a marginal issue in Norway, which contributes in a multifaceted manner to silences in the narratives, whether they come from the Nation State, the wider Norwegian public, or archival institutions. In other words, small silences built into the life of the records (the unequal power in the capturing of the moment, in the failure to index the contents of the records, in the mediation efforts, and the looming of national narratives) accumulate to affect the retrospective significance; the production of historical narratives. The very nature of atrocities requires people to ignore, bury, or deny them.Footnote78 The apathy or burying of atrocity is a multidimensional process that affects records at every stage of their life and thereby their narratives, not only those they wish to convey, but those they help create, in this case a genocide that is not fully acknowledged despite the goodwill of important individuals.

The impact of this collection is felt primarily in the activations for the international Armenian population as the art piece Red Hail expresses and the central place Biørn’s photographs have at the Genocide Museum and their website where they are depicted as direct evidence of the Genocide. The records have brought people from around the world with an interest in the Armenian community together. It is the ‘community of records’ that have formed an extrajudicial and international effort to create historical accountability when politicians and legal systems fail for a people who have sought it for generations.

In the context of Norway these records have a greater potential to force the Norwegian public and authorities to engage with the issue of the Armenian Genocide, not as a symbol of historical injustice but as a contemporary one, if the debate can move beyond Biørn to find the stories that lie behind the images and texts and push them into the public view. Only then may they help to become tools for historical accountability here in Norway too rather than a national footnote.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Per Kristian Ottersland from the Norwegian National Archive for bringing these documents to my attention, for his help, patience and kindness in answering all my questions.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup

Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup is a PhD candidate at Oslo Metropolitan University at the department of Archivistics, Library and Information Science. She has a BA in Library and Information Science from Oslo Metropolitan University, a BA in Humanities and an MA in the Theory and Practice of Human Rights from the University of Essex, UK. She was an intern at the Interamerican Human Rights Court in Costa Rica and the Bodleian Library at University of Oxford. She has worked as a Research Assistant at The University of Oslo and was the Information Coordinator for Childwatch International Research Network. Her research interests are libraries and archives for human rights and peacebuilding.

Notes

1. Appadurai, The Social Life of Things.

2. This is inspired by Michelle Caswell’s use of Appadurai’s concept ‘the social life of things’ in her work Archiving the Unspeakable.

3. Translated to English as the Norwegian Women Missionary Workers, referred to in this paper by the Norwegian acronym KMA.

4. Okkenhaug, ‘Refugees, Relief and the Restoration of a Nation’, 212.

5. Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable.

6. Appadurai, The Social Life of Things, 5.

7. Ibid.

8. This is the name given by Riksarkivet to the collection of records created by Bodil Biørn, within the KMA archive.

9. Sørensen, ‘Haunted Topographies’.

10. Brown and Duguid, ‘The Social Life of Documents’, paragraph 5.

11. Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable, 10.

12. Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable.

13. Okkenhaug, ‘Refugees, Relief and the Restoration of a Nation’, 211.

14. Suny, ‘They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else’, 31.

15. Sir Charles Norton Eliot quoted by Ibid, 31.

16. Ibid.

17. See ‘Asadur i hjemmet 1/2 år efter opptagelsen’ (Assadur at the orphanage half a year after admission — own translation): https://no.wikimedia.org/wiki/Prosjekt:Bodil_Biørn#/media/Fil:Kvinnelige_Misjonsarbeideres_arbeid_i_Armenia_-_fo30141712120004_546.jpg.

19. Adalian, ‘Chapter 4: The Armenian Genocide,’ 118.

20. Hovannisian, ‘Chapter 2: Confronting the Armenian Genocide,’ 42.

21. Adalian, ‘Chapter 4: The Armenian Genocide.’

22. Ibid.

23. The best-known Armenian scholars on the Genocide are Richard Hovannisian, Vahakn Dadrian and Levon Marashlian among others. Non-Armenian scholars include Yves Ternon, Robert Jay Lifton, Leo Kuper and Tessa Hofmann who write about the consequences and effects of the Genocide and its classification. Details as to the events of the Genocide are well catalogued in Gust, The Armenian Genocide as he gathers first-hand accounts. The fate of women and girls is analysed in Bjørnlund, ‘A Fate Worse than Dying. Sexual Violence during the Armenian Genocide.’

24. Okkenhaug, En Norsk Filantrop.

25. Gust, The Armenian Genocide, 468–473.

26. Gust, The Armenian Genocide, 468–473.

27. See . Own translation.

28. Most of the photographs referred to in this section are found in the first two links 33.1 and 33.2: https://www.digitalarkivet.no/search/sources?s=BI%C3%98RN&from=&to= &format=all&archive_key =

29. https://no.wikimedia.org/wiki/Prosjekt:Bodil_Biørn. Please note the Ø character in the link. Alternatively use the Wikimedia search engine to search ‘Bodil Biorn’ which offers corrected searches.

30. Crane’s article explores the nature of the gaze when looking at atrocity images.

31. Biørn, Kvartalshilsen no. 4 1917, 42.

32. See: https://no.wikisource.org/w/index.php?sort = relevance&search = Kvartalshilsen&title =Spesial%3ASøk&profile = advanced&fulltext = 1&advancedSearch-current = %7B%7D&ns0 =

33. Okkenhaug, ‘Refugees, Relief and the Restoration of a Nation’

34. Sekula, ‘The Traffic in Photographs’, 15–25.

35. Jenkins, ‘Missionary Photography’, 293.

36. Ibid.

37. Okkenhaug ‘Refugees, Relief and the Restoration’.

38. Ibid.

39. Crane, ‘Choosing not to Look’, 324.

40. Private correspondence with Riksarkivet’s archivist Per Kristian Ottersland.

41. Ibid.

42. Private correspondence with the former senior archivist Vilhelm Lange.

43. Larsen, Kronikk: Ingen forsoning uten innrømmelser.

44. Interview with Per Kristian Ottersland. 29, October 2019 at Riksarkivet, Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup.

45. Letter from the Turkish Ambassador Mehmet Gorkay to The Norwegian National Archive Director General John Harstad, 10 March 2006 — Letter provided by Riksarkivet Norge.

46. Letter from Director General of the Norwegian National Archive to the Turkish Embassy, 27 March 2006 — Letter provided by Riksarkivet Norge.

47. Letter from the Turkish Ambassador Mehmet Gorkay to The Norwegian National Archive Director General John Harstad, April19, 2006 — Letter provided by Riksarkivet Norge.

48. Ibid.

49. An edited version is available here: https://www.arkivverket.no/utforsk-arkivene/nyere-historie-1814-/norske-kvinner-dokumenterer-folkemord

50. Lange 2008 lecture notes from seminar at Riksarkivet given in an email correspondence. 27, April 2019 email correspondance between Vilhelm Lange and Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup.

51. Ibid.

52. Interview with Per Kristian Ottersland at the Norwegian National Archive. 29 October 2019 interviewed at Riksarkivet by Natalia Bermúdez Qvortrup.

53. Skjærli, ‘Erna Vil Ikke Delta I Folkemordmarkering’.

54. Tessem & Mauren, ‘Minst én million mennesker ble drept’.

55. Altanian, ‘Archives against Genocide Denialism?', 17.

56. Ibid.

57. Caswell, ‘Khmer Rouge Archives’, 38.

58. Wilson, ‘“Peace, Order and Good Government.”

59. Biørn, ‘Children with Dolls’, Wikimedia Commons link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Barn_ved_Musch_barnehjem%3F_-_fo30141712180050.jpg.

60. Barseghyan and Stepanian, Red Hail: because it never ends. A link to the book and exhibition can be found at https://massispost.com/2015/06/red-hail-works-by-armenian-photographers-on-display-at-kafka-house-in-prague/

61. See Informasjonsarbeid at https://no.wikimedia.org/wiki/Prosjekt:Bodil_Biørn;

64. The Armenian Genocide Museum Institute Foundation Online exhibition: Bodil Biørn Retrieved from http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/online_exhibition_4.php (7th November 2019).

65. Ibid.

66. Ibid.

67. Ibid.

68. Sindbæk Andersen and Törnquist Plewa, Disputed memory: emotions and memory politics in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe.

69. Thomas et al., Silence of the archive, 53.

70. Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable.

71. Edensor, ‘Material Culture and National Identity’.

72. Caswell, Archiving the Unspeakable, 7.

73. Edensor, ‘Material Culture and National Identity’, 116.

74. Zarifian, ‘The United States and the (Non-)Recognition of the Armenian Genocide’.

75. Millar, ‘Touchstones’.

76. Adalian, ‘Chapter 4: The Armenian Genocide’, 137.

77. Ibid.

78. Alayarian, Consequences of Denial, 75.

Bibliography

- Adalian, R.P. “Chapter 4: The Armenian Genocide.” Centuries of Genocide: Essays and Eyewitness Accounts. edited by. S. Totten and W.S. Parsons, 117–155. ProQuest Ebook Central. Abingdon, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.

- Alayarian, A. Consequences of Denial: The Armenian Genocide. London, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis Group, 2008.

- Altanian, M. Archives against Genocide Denialism? Basel Switzerland: SwissPeace, 2017.

- Appadurai, A., and W. Ethnohistory. C. Symposium on the Relationship Between, Culture, and W. Ethnohistory. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- The Armenian Genocide Museum Institute Foundation. Online exhibition: Bodil Biørn. Retrieved from http://www.genocide-museum.am/eng/online_exhibition_4.php 7, November 2019.

- Barseghyan, N., and L. Stepanian. Red Hail: Because It Never Ends. Eiva Arts Foundation: Armenia at PQ 2015, 2015.

- Bjørnlund, M. “A Fate Worse than Dying. Sexual Violence during the Armenian Genocide.” In Brutality and Desire: War and Sexuality in Europe’s Twentieth Century, edited by D. Herzog, 15–58. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2009.

- Brown, J.S., and P. Duguid. “The Social Life of Documents” First Monday. 1, nos. 1-6 (May1996). https://firstmonday.org/article/view/466/387 accessed November 2019. n.p.

- Caswell, M. “Khmer Rouge Archives: Accountability, Truth, and Memory in Cambodia.” Archival Science 10, no. 1 (2010): 25–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-010-9114-1.

- Caswell, M. Archiving the Unspeakable: Silence, Memory, and the Photographic Record in Cambodia. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 2014.

- Crane, S.A. “Choosing Not to Look: Representation, Repatriation, and Holocaust Atrocity Photography 1.” History and Theory 47, no. 3 (2008): 309–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2303.2008.00457.x.

- Digitalarkivet, KMA Archive, accessed2 October 2020 https://www.digitalarkivet.no/search/sources?s=BI%C3%98RN&from=&to=&format=all&archive_key=

- Edensor, T. “Material Culture and National Identity.” In National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life, edied by Tim Edensor, 103–137. Berg: Oxford, 2002.

- Gust, W. The Armenian Genocide: Evidence from the German Foreign Office Archives 1915-1916. New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2014.

- Hovannisian, R. “Confronting the Armenian Genocide.” In Pioneers of Genocide Studies, edited by Samuel Totten and Steven Leonard Jacobs, 27–46. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2002.

- Jenkins, E. L. “Missionary Photography: The Liberian Archive of Doctor Georgia Patton.” Visual Resources 34, no. 3–4 (2018): 293–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01973762.2018.1478556.

- Larsen, B. (2015). Kronikk: Ingen Forsoning Uten Innrømmelser. VG. Retrieved from https://www.vg.no/nyheter/meninger/i/12w4Q/kronikk-ingen-forsoning-uteninnroemmelser

- Millar, L. “Touchstones: Considering the Relationship between Memory and Archives.” Archivaria 61 (2006): 105.

- Norge, Wikimedia, Bodil Biørn Project accessed 2 October 2020. https://no.wikimedia.org/wiki/Prosjekt:Bodil_Biørn

- Okkenhaug, I.M. “Chapter Ten. Refugees, Relief And The Restoration Of A Nation: Norwegian Mission In The Armenian Republic, 1922-1925.” Protestant Missions and Local Encounters in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Unto the Ends of the World. edited by. H. Nielssen and I.M. Okkenhaug. Hestad-Skeie, 207–232. ProQuest Ebook Central . Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2011.

- Okkenhaug, I.M. En Norsk Filantrop: Bodil Biørn Og Armenerne. Kristiansand: Portal forlag, 2016.

- Sekula, A. “The Traffic in Photographs.” Art Journal 41, no. 1 (1981): 15–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.1981.10792441.

- Sindbæk Andersen, T., and B. Törnquist Plewa. Disputed Memory: Emotions and Memory Politics in Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe. 24. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

- Skjærli, B. (2015). Erna Vil Ikke Delta I Folkemordmarkering: - Ynkelig Og Feigt. VG. Retrieved from https://www.vg.no/nyheter/utenriks/i/121nQ/erna-vil-ikke-deltai-folkemordmarkering-ynkelig-og-feigt

- Sørensen, T.H. “Haunted Topographies: Landscape Photography as an Act of Remembrance in the Neues Museum, Berlin.” In Uncertain Images: Museums and the Work of Photographs, edited by E. Edwards and S. Lien, 113–129. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2014.

- Suny, R. G. “They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else”: A History of the Armenian Genocide (Fourth Printing, and First Paperback Printing. Ed.). Princeton, New Jersey;,Oxfordshire England: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Tessem, L. B., and A. Mauren (2015). Minst Én Million Mennesker Ble Drept under Folkemordet På Armenerne. Et viktig minne er fotografiene etter den norske misjonæren Bodil Biørn. Aftenposten. Retrieved from https://www.aftenposten.no/norge/i/d4mkw/jeg-har-vaert-med-aa-se-alt-detfrykteligste-som-tenkes

- Thomas, D., S. Fowler, and V. Johnson. The Silence of the Archive. London: Facet, 2017.

- Wikimedia Armenia. In the Footsteps of Bodil Biørn: From Norway to Armenia. Armenia: Wikipedia Armenia scientific education NGO, 2019.

- Wilson, I.E. ““Peace, Order and Good Government”: Archives in Society.” Archival Science 12, no. 2 (2012): 235–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-011-9168-8.

- Zarifian, J. “Les États-Unis et la (non) reconnaissance du génocide des Arméniens.” Études arméniennes contemporaines 1, no. 1 (2013a): 75–95.