ABSTRACT

Between May 2017 and September 2018, the Staffordshire Record Office and the University of Liverpool ran a collaborative volunteer research project titled Historic Flooding and Drought in Staffordshire, part of the AHRC funded project Learning from the Past — exploring historical archives to inform future activities. As researchers working closely within an archive service alongside staff and closely with volunteers, the Flooding and Drought project presented the opportunity to examine collaboration from multiple perspectives at once — the archive, the researcher or collaborating partner, and the volunteers. This paper argues that while not ideal for all archive volunteer activities (such as cataloguing), such projects can facilitate activities that an archive cannot achieve alone. Moreover, by providing stimulating and challenging activities, collaborations can capture volunteer interest, draw in new volunteers, develop volunteer skills and deepen volunteer loyalty and connection to the archive. Further, by working closely with the volunteers and valuing their experience and skills, the researcher can benefit from the support of those who have an intimate knowledge of the archive and the surrounding area. By fostering these collaborations and relationships, archives can provide valuable support for both their volunteers and researchers that might not otherwise be possible.

Introduction

This project is important for the SRO as the way it is run is a new development for them. This style of working will be more important in the future as the SRO is encouraged by the HLF to have more community engagement with fewer staff.Footnote1

This was written by one of the volunteers working with the Flooding and Drought project at the Staffordshire Record Office (SRO), coordinated by two PhD students from the University of Liverpool (UoL) at the SRO and jointly supervised by both faculty from the UoL and archivists from the SRO. The volunteer represents the kind of ‘expert’ volunteer described by Caroline Williams with pre-existing knowledge and skillsFootnote2: he had been volunteering at the record office for fourteen years, was chairman of the Friends of the Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service and on the committee of the Staffordshire Archaeology and History Society. This volunteer’s remarks show collaborative projects being valued by an expert volunteer.

This article sets out to understand the challenges and benefits of collaborations between archive services and academics, in contrast to the bulk of literature on the archive/academic relationship which is about academics as users rather than partners. It is clear both from academic literature and sectoral knowledge that collaborative projects are not new and bring benefits to both the archive and the collaborating partner. As demonstrated by Shaun Evans and Elen Wyn Simpson in discussion of the development of the Institute for the Study of Welsh Estates, such projects build connections and relationships across sectors.Footnote3 In an article focused on archivist/academic collaboration, Alix R. Green and Erin Lee urged an ongoing conversation between archivists and academics, recognition of each other’s professional structures and expertise and a flexibility towards change.Footnote4 Although this guidance is too recent to have influenced the Flooding and Drought project, it does ring true. The project did not play out entirely as expected, but flexibility from the parties involved and working in partnership allowed the project to develop in unexpected and fruitful ways.

Examining Flooding and Drought will also contribute to the understanding of the impact of such projects on volunteers. Archive volunteers have been studied, although not in relation to specific research interests. The present research therefore adds valuable case study data to existing literature. Williams’ 2014 report to the Archives and Records Association (ARA) provides data on volunteers, focusing on volunteer management, while her 2018 report examines the impact of volunteering, using eighty-three case studies (mostly local authority).Footnote5 Earlier work by Louise Ray in 2009 for the National Council on Archives (whose responsibilities passed to the Archives and Records Association and The National Archives (TNA)) provides similar data on volunteers to Williams.Footnote6 As bodies with a vested interest in ensuring volunteering is well managed, the ARA and TNA have both produced statements and advice on archive volunteering.Footnote7 TNA published its own guidance on volunteer cataloguingFootnote8 and Helen Lindsay has produced a ‘Best Practice Guide’ on volunteering in collection care on behalf of the ARA.Footnote9 While Williams discusses the motivations of volunteers, there is little work on the loyalty of volunteers towards the archive and what motivates volunteers to continue volunteering. As maintaining the interest of existing volunteers was highlighted as a benefit of this project by the archive service, its findings in this regard will be beneficial to other services.

Historic flooding and drought in Staffordshire

Between May 2017 and September 2018, a volunteer research project was run as a collaboration between the SRO and the UoL departments of Geography and History intended to (as described in the funding bid):

Construct histories of flood/drought and associated impacts

Explore whether and how events affected the lives of local people and became inscribed into the cultural and infrastructural fabric and social memory of local communities

How the above shaped practices and management actions

It was led by two PhD students on Collaborative Doctoral Awards, an AHRC scheme in which doctoral students work with a partnering non-higher education institution (HEI) organization for their research and was designed from the outset to involve volunteers. The project, Historic Flooding and Drought in Staffordshire, engaged a group of volunteers in researching past flooding, drought and weather in Staffordshire and providing catalogue enhancement for the archive. It resulted in two PhD theses: one focusing on drought in the eighteenth century onwards and the other using flooding and water management in the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries to examine challenges for environmental research in archives.Footnote10 This article has drawn from the latter, as I used the research as a case study into the challenges of using archives for environmental research, and potential solutions, from the perspective of both researchers and archivists.Footnote11 Although the volunteer project Flooding and Drought was not planned as a piece of action research and therefore the associated mechanisms were not incorporated from the start, in retrospect it will be used as a springboard for discussion of the benefits of collaborative projects.

As part of the Flooding and Drought project, volunteers were used in several ways:

Transcription of mill accounts and relevant sections of records

Basic data analysis (e.g. recording grain sales, mill expenses and repairs or terms of leases into a pre-formatted spreadsheet)

Assistance with catalogue enhancement by recording information that could be used to improve catalogue description or add index terms to catalogue entries

The funding bid identified source types that would potentially be valuable for environmental research, including chronicles, parish registers, Quarter Sessions records, diaries, and estate records. At the beginning of the project, the PhD students reassessed which sources would be of interest and choose which would be examined by volunteers. Quarter sessions records were very valuable for my thesis (‘Learning from the Past: Exploiting Archives for Historical Water Management Research,’) but were the subject of another long-running project at the SRO, so were examined by me rather than the volunteers. Parish registers were also not prioritized to avoid replicating recent research that had made use of parish registers at the SRO.Footnote12

Seven volunteers examined diaries from the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for the ‘drought’ half of the project. Two volunteers were involved in the nominally named ‘flood’ half of the project, working with title deeds and mill accounts. They were able to examine more material than a researcher could have done alone in the same timeframe. The volunteer examining title deeds provided over one hundred hours to the project and consulted over two hundred documents. They often continued working on material outside the project sessions, both by consulting documents at the record office and by taking photographs to examine later or pursuing research to understand more about the records being examined. For example, this volunteer discovered that a lease from the crown in 1587Footnote13 had an almost identical maintenance clause (barring references to water) to one identified by J.N. Bagnall in the Augmentation Office Records for a property in Wednesbury.Footnote14 He was not the only volunteer to give time to the project beyond its ‘official’ hours — some of the volunteers examining diaries continued after the project had ended, emailing the coordinators with updates.

While the Flooding and Drought project was running, there were several other volunteer activities occurring including research projects, conservation, and several projects to catalogue series of records. Many of these were projects run in-house by the SRO, and some (including the Quarter Sessions and the conservation volunteers) had been running for several years. However, there were others which, like Flooding and Drought, were run as collaborations. These include the Victoria County History research, The Staffordshire Place-Names Project (with the University of Nottingham) and Criminal Quilts (an art project inspired by photographs and documents relating to women held in Stafford Prison 1877–1916 run by Ruth Singer).

Methodology

To understand the benefits of collaborative projects such as Flooding and Drought, the project needed to be placed in the context of other volunteering at the SRO. Some basic data, including names, reported volunteer hours and descriptions of projects are provided by the Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service’s annual reports.Footnote15 Between 2016 and 2019, the archive service named 124–155 volunteers per year, and well over 8,500 volunteer hours each year.Footnote16 These reports provide numbers of volunteers, but do not reflect the experiences of the volunteers.

To resolve the absence of volunteer data and support the coordinators’ personal experience of the project, I ran a survey between June and September 2018 to produce data on SRO volunteers from across different projects and gather a sample of volunteers’ opinions and experiences. The volunteer survey consisted of three sections, using a variety of question styles to prompt different styles of answer and opportunities to provide their own comments.

The first section established their volunteering history and habits, asking the volunteers to list the projects they were part of, that they had previously been part of, how long they had volunteered for and whether they volunteer for other heritage or cultural organizations. The second section aimed to understand their experience of volunteering and asked if they had visited the record office before volunteering and whether they consider themselves a regular archive user. They were asked why they volunteer, with a range of options to choose from including ‘other,’ and what benefits they had experienced from volunteering, with a range of statements to mark ‘agree,’ ‘disagree’ or ‘not applicable’ against (such as ‘I enjoyed myself’). Then they were asked whether they feel valued as volunteers (and why), whether volunteering had changed their perception of Staffordshire’s history and whether they were likely to volunteer for the record office again. The final section consisted of some basic demographic questions.

The results of the survey of volunteers suggest that the demographic of SRO volunteers might be considered typical of a local archive, but the findings may not be as applicable for a project working in a different setting. Most SRO volunteers are retired. They have different skills, experience, and time to give to volunteering than, for example, volunteers seeking experience for a future career. Both Ray in 2009 and Williams in 2014 found that the majority of volunteers were between fifty-five and seventy-four years old.Footnote17 The age profile of SRO’s volunteers are typical of this, with around ninety-six per cent of volunteers being over fifty-five. All SRO volunteers who were willing to state their ethnicity said they were white, consistent with Williams’ finding of ninety-seven per cent white volunteers.Footnote18 The gender ratio is also completely typical, almost exactly fitting Williams’ findings of sixty-three per cent female to thirty-seven per cent male.Footnote19 Because the profile of SRO volunteers is so close to that of the national average, experience from the SRO can be considered reasonably likely to be applicable elsewhere.

There were thirty-two responses to the survey, representing twenty to thirty per cent of the archive service’s volunteers (depending on whether the annual report from 2017–18 or 2018–19 is considered most accurate for the time of the surveyFootnote20). The results were consistent with the experience of the project coordinators and there is no reason to doubt that they are representative of SRO volunteers. Of volunteers surveyed, sixty-two per cent had visited the Record Office prior to volunteering, and half of the volunteers reported having been involved in previous projects. Meanwhile, most volunteers reported hearing about their projects through means that are more likely to reach people who are already familiar with the SRO, such as word of mouth or the Archive and Heritage Service email newsletter.

After the conclusion of the Flooding and Drought project, I held an interview with an archivist from the SRO who had guided the researchers in coordinating the project. The interview was semi-structured to allow discussion to arise organically, as I already had a well-established relationship with the archivist. Questions included why the archive pursued collaborative projects, what they hoped to gain from them (both in general and specifically the Flooding and Drought project), and whether there were any unexpected benefits of the project. This led to discussion of skill building for volunteers and a shift in priorities during the project, which was partly due to interaction between the limits of available archive material and the needs of different parties involved.

Lindsay’s best practice guidance on volunteering notes that any arrangement between volunteers and an organization must benefit both parties.Footnote21 However, a collaboration with an HEI involves a further party, or set of parties. This affects the activities which are appropriate for the project and sometimes limits what is possible, while bringing the benefit of the perspective of the researcher or HEI and their experience to the project. The project coordinator has their own research goals as well as requirements from their home organization or funding body. This is likely to include research outputs such as publications but can also involve public outreach. HEIs need to demonstrate ‘impact’ to the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Research Excellence Framework (REF), defined as ‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia.’Footnote22 A project funded by a body such as the AHRC (like Flooding and Drought) will also have requirements from both the funding body and the academic partners expressed in the project proposal.

Flooding and Drought therefore needed to produce research for two PhD theses exploring these research themes within the timeframe of a PhD (including planning beforehand and writing afterwards). This determined the materials used and focus of the project, with the PhD students prioritizing research themes rather than archival structures (such as a fonds, collection, or series).

Benefits

The benefits for each party involved in the project are not fully separable as they often arose from the relationships that developed. When asked in interview why the record office pursued collaborations with HEIs, and what benefits they hoped to gain, the archivist described three main reasons, which reflected the interaction between the archive and the researchers and between the archive and the volunteers. First, they already had developed relationships with academics, and they wished to formalize these arrangements. Second, by collaborating (and jointly applying for funding), the record office can pursue bigger, more meaningful projects, saying:

We hoped to be able to sort of punch above our weight. We have a small staff but working in partnership with universities means we can take on more adventurous projects, which not only enhances our reputation within our organisation, which is actually quite an important thing for us, but it also means that we can build on relationships to reach out and get new ones.

By being able to demonstrate the value of potential projects, being a trusted partner, and by being able to apply for funding jointly, the record office can take on projects beyond their usual scope. Flooding and Drought demonstrates how these ‘adventurous’ projects can develop. Having itself grown from an existing partnership between the UoL and the SRO, it has led to further research with Clandage: Building Climate Resilience. The social media account from the Flooding and Drought project has now been subsumed into this new AHRC project (from November 2020), to take advantage of these existing connections and continuity of research themes.Footnote23 Flooding and Drought was one stage in a long-term partnership.

The third reason described was that academics as project coordinators give volunteers a sustained period with someone with expertise and enthusiasm for the volunteers’ work. While there is work required on the part of the archivists in setting up projects, the collaborating researchers can provide most of the time needed to supervise and guide the volunteers. Where a record office has a loyal body of experienced volunteers, it can be a challenge to find appropriately challenging and rewarding work for them to do. The archivist made specific reference to one of the Flooding and Drought volunteers, describing him as ‘somebody who had a strong skillset, but just needed something to do with it, which is what you gave him.’

As Williams notes, retirees often bring highly detailed knowledge of the organization they involve themselves with.Footnote24 Williams frames this as a benefit to an archive team, however this can be very useful to a project coordinator on a collaborative project who is less familiar with the archive. Although over ninety per cent of the SRO catalogue is now online, there is still material that is still best found through the paper catalogue (which is more challenging and time consuming to search). The volunteer engaged in examining title deeds was able use his own experience to find documents that had not been identified when creating the initial list for him to consult. He was also able to contribute his own knowledge of Staffordshire’s history to the project, possessing a detailed knowledge of the county’s geography, landmarks, and the landowning families (among many other topics).

Profile raising and widening archival engagement

Williams notes that thematic projects focus on more cross-cutting approaches and can support strategic and partnership initiatives, as well as being useful for profile-raising, publicity and marketing.Footnote25 With the contemporary relevance of environmental topics, and frequent UK headlines about flooding, environmental projects such as Flooding and Drought present an opportunity to showcase the material held by an archive in a new light. The Flooding and Drought social media drew some attention, with the project blog receiving 2,212 views from 689 visitors during the seventeen-month run of the project (along with six followers). From the end of the project in September 2018 to December 2019 there were a further 402 views and 177 visitors.Footnote26 These figures do not show whether engagement with the projects online presence came from academic researchers or the public, or whether many of them were existing users of the archive. However, some of the most frequently viewed posts were the calls for volunteers (after the home page and profiles of each project coordinator).

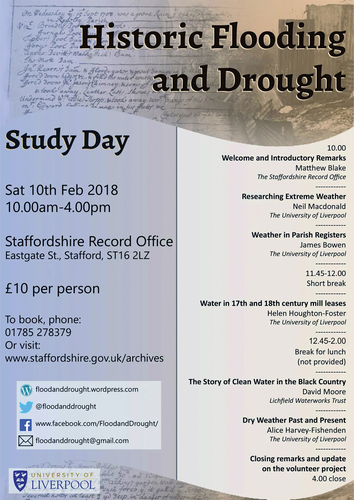

Further evidence of public impact comes from outreach activities. In February 2018 a ‘study day’ was held, which comprised of talks by researchers around the themes of flooding, drought, and water (). Study days on new or different topics can be an opportunity to attract new visitors. The study day for Flooding and Drought was fully booked, with a waiting list for places to attend. Attendees included academics, members of the public, and record office volunteers. The SRO always offers free tickets for their study days to the volunteers, so they provide a valuable opportunity to give something back and showcase volunteer achievements as they see their work used and appreciated, providing benefits for the volunteers as well as helping the SRO’s profile with different audiences.

Collaborative projects with novel themes, such as the environment, have the potential to widen archive engagement to volunteers or researchers who might not be ‘typical’ archive users, or have previous archive experience. This was explored by Buchanan and Bastian with Mr Seel’s Garden, which investigated the potential of archives for local food activism,Footnote27 and more recently Annie Tindley et al have examined how collaborative projects using estate records can be a vital resource for local communities.Footnote28 The SRO has a strong community of loyal volunteers who have been with the SRO for periods up to twenty years. On projects run in-house and focused on traditional archival activities such as cataloguing, indexing, preservation, or digitization the survey found more established volunteers than newer ones (defined as starting in the past year and comprising forty-one per cent of responses). While collaborative projects do draw ‘expert’ volunteers, their novelty can also attract new volunteers to an archive. Of the volunteers from Flooding and Drought who completed a survey, half had started volunteering with the record office within the past year, a higher proportion than across the service. These new volunteers might include those who would not be drawn in by traditional archival activities.

New volunteers have the potential to develop into experienced ‘expert’ volunteers. Among the first-time volunteers on Flooding and Drought, one signed onto another project running concurrently to Flooding and Drought, and several more enquired about further volunteering opportunities. However, one volunteer from the Criminal Quilts project responded that they were unlikely to volunteer again (although they had enjoyed the project). It was a novel project, and although there are many reasons why someone might not continue volunteering, it is possible that the more conventional style of project at the record office may not suit the individual’s interests. The Criminal Quilts project offered a variation to many of the projects available with the archive service.Footnote29 It was coordinated by artist Ruth Singer and involved researching women held in Stafford Prison 1877–1916 and creating textile artwork inspired by them, and therefore was very unusual in comparison to other archive projects.Footnote30 Partnering with an external organization and running a project of a different style to usual has the potential to draw in volunteers who may not have considered (or been aware of) volunteering opportunities with an archive service. While some may not choose to continue volunteering, others will, and the archive can both expand engagement and attract new volunteers.

Volunteers: a two-way exchange

As previous guidance on working with volunteers has identified, it is essential that volunteering projects consider the impact on volunteers, both to ensure that their needs are met and to demonstrate societal impact for the record office. There has been some work on the ‘costs’ of volunteering on volunteers, including time, hazards, and inconvenience,Footnote31 however these costs were not found in the survey of SRO volunteers, or they were not considered costs by the volunteers. It seems unlikely that volunteers would continue to volunteer enjoy working at the record office if they did not enjoy it, but that does not mean that they would not have criticisms of their experience. However, the survey responses did not contain criticisms, or evidence of ‘costs’ to the volunteers.

The SRO has a body of loyal volunteers, willing to engage with multiple projects or continue volunteering after their project ends. Around thirty-eight per cent of SRO volunteers were found to be engaged in more than one project simultaneously. This enthusiasm speaks to an enjoyment of volunteering with the record office just as much as it reflects the Flooding and Drought project. Half of volunteers surveyed had volunteered for at least one project prior to their current ones, while ninety-one per cent said they were likely to, or definitely would, volunteer in the future. Among the six Flooding and Drought volunteers who completed a survey, four were involved in other current projects, including the Magistrates Records, Criminal Quilts, and Parish Rights of Way. Two of these had also volunteered for prior record office projects, naming eight different projects between them. Responses to open-ended survey questions bear this out, with volunteers expressing a love of volunteering and that they ‘will continue volunteering for as long as I am able.’

Volunteers bring both their existing skills to the SRO and a desire to learn new things. The knowledge transfer happens in both directions: while they contribute to projects, they develop their own skills and knowledge. When surveyed, sixty-six per cent of volunteers expressed a desire to learn new skills or improve existing ones, and eighty-one per cent said they had developed new or existing skills while volunteering. Cultivating relationships with volunteers benefits both the volunteers and the record office. Long-term volunteers and those eager to learn and develop skills are useful to the archive, such as with conservation, whilst the evidencing of skills learned can support an archive’s claims to community benefit for its parent organization.

The benefit to the volunteers is one of the reasons for collaborating on projects that was described by the record office archivist. The archivist observed that the curiosity, existing skills, and intelligence of many of their volunteers meant that:

… it’s good for them to feel stretched by people with their specialist knowledge and also they often, because our volunteers tend to be older, they often come with a very strong set of skills, and it’s good to be able to make use of their skills and help them to develop their skills further, and we generally wouldn’t have time to do that on our own. But you know that work you did with [name of volunteer].

Later in the interview, the archivist mentioned ‘stretching’ again, discussing academic-led projects. It was noted that even if the volunteer activities themselves are straightforward, the volunteers enjoy feeding into a more challenging project and learning about the research.

In May 2018, Susan Kilby from the University of Leicester ran a series of palaeography sessions for the Staffordshire Place-Names project. This has the added benefit of novelty, providing variation from the usual running of projects and making the volunteers feel that their needs are appreciated. There is evidence from the survey conducted that this was appreciated by volunteers who attended, with one response mentioning the sessions as one of the reasons they felt valued as a volunteer. The same respondent specifically indicated that they had developed their palaeography skills in response to the question ‘What benefits have you experienced from volunteering?’ and added a note on the end of their survey, saying, ‘If you have any trouble with my writing, I am a semi-trained palaeographer and can possibly help you.’

Responses such as this display a great deal of gratitude (and wit) towards the SRO for facilitating their desire to learn. The most common comment given when asked to elaborate on why they felt valued was the helpfulness of record office staff, the word ‘helpful’ was used to describe staff by seven volunteers, and another three mentioned ‘help’ from record office staff. This enthusiasm for learning proved invaluable to the Flooding and Drought project. It meant that volunteers not only brought their own knowledge and skills to the project but were also willing to learn and develop with the project, adapting to the project material.

Survey responses also showed that volunteers enjoy expanding their knowledge of their county and local history, something that a local record office can facilitate. Research projects have the potential to enrich volunteers’ local geographical knowledge, particularly if the research is in historical geography such as with the Place-Names project or Flooding and Drought, with one of the volunteers for the former saying that the project ‘is enriching my knowledge of my local area.’ A volunteer from the Flooding and Drought project also mentioned being very interested in new water management and agricultural practices on Lord Stafford’s estate in the eighteenth century. While being encouraged to examine archive material in new ways, the volunteers also found their own interests reflected in the records. For example, one volunteer examining diaries for weather became very interested in details of eighteenth-century gardening. As observed, the volunteers seem potentially more excited by learning more about the social or environmental history of their county, noting that it was a pleasant change from ‘kings and earls.’ Whatever the precise nature of the volunteers’ interest in their projects, it is clear that the projects can inspire them to learn more about their area and demonstrate the community value of a local record office, with one saying that volunteering has ‘Given me a taste for finding another local project.’

Supporting research

This project has demonstrated measurable impact on volunteers, but this can be valuable in an academic context. The questions asked of volunteers were not designed to measure this impact in terms applicable to the UKRI REF, however the impacts of this project certainly fit the REF definition of impact.Footnote32 As well as providing the outreach and engagement outlined above, collaboration with an archive service creates opportunities for research that might not be available to most academic archive users. Working with volunteers brings benefits that are particularly useful for environmental research. For a geographical study of a specific area, an intimate knowledge of the area is extremely useful for a researcher. If the researcher does not possess this, volunteers can provide valuable assistance. On the Flooding and Drought project, social bonds were formed between researchers and volunteers, and between the researchers and archive staff. This helped foster a sense of familiarity with Staffordshire, even of belonging, that became an unexpected benefit to the PhD researchers, who were neither originally from the local area nor resident in the area over the course of the project.

The Flooding and Drought volunteers were often able to bring their own knowledge to the project. For example, the search for mill leases uncovered two plans of the Shugborough estate from the late eighteenth century. The first plan, from circa 1780, has a hole in part of the plan, including part of where the mill pool is.Footnote33 It was hard to recognize some of the features on the plan as it was not drawn with much accuracy and the estate landscape has since changed. However, the volunteer examining leases was very familiar with the estate and was able to instantly identify landmarks such as the Tower of the Winds and the shape of Essex Bridge. The mill pool has since changed shape, and the Tower is no longer in the water, so the assistance of the volunteer was useful in identifying a landmark which on the plan is marked only with a black circle. Volunteers have an extensive knowledge of their local area. Their perception of that knowledge is not framed according to academic disciplinary concerns, but it is extremely valuable for research rooted in a local area.

As already identified, the SRO can attract very highly skilled volunteers as well as enthusiastic new ones. The newer volunteers were less likely to have advanced research skills (i.e. be confident with palaeography or Latin), and projects cannot always expect to attract many volunteers with these skills. However, the newer volunteers were eager to learn, and often adapted readily to new tasks. Most of the volunteers on the project were not working with Latin documents at all and only four leases were in Latin. However, Flooding and Drought was fortunate to involve one individual who had excellent Latin and palaeography skills who had been a volunteer for the record office for fourteen years, as well as extensive enough experience with title deeds that he could reliably identify uncatalogued deeds.

Challenges: catalogue enhancement

Flooding and Drought was intended to provide catalogue improvement and indexing for the archive, following the Revisiting Archive Collections methodology, which aims to open archives to new audiences.Footnote34 Some catalogue enhancement was achieved: spreadsheets of mill accounts and diary entries were transferred to the SRO after the project was completed. Catalogue entries for relevant records were updated and the index terms for flooding and types of mill were added to catalogue entries for records that had been examined. In addition, four bundles of deeds were identified for property in the manor of Cannock and Rugeley that had poor existing cataloguing,Footnote35 which may be legacy data originating with the accession of the deeds in 1953.Footnote36 These bundles were re-catalogued as part of the project in a manner consistent with both ISAD(G) and the rest of the collection and series to which they belong.

Many archival processes can be slow, archives often have a substantial backlog of material, and in 2003 the logjam audit recorded that twenty-nine per cent of archives in the North-West remained inaccessible.Footnote37 Recent emphasis has been on improved access for the archive user,Footnote38 and to facilitate making archive material available efficiently, the need to catalogue to item level has been challenged with the call for More Product, Less Process (MPLP) by Mark Greene and Dennis Meissner.Footnote39 This approach has been adopted by many archival institutions to tackle backlogs of unprocessed (and therefore inaccessible) material by focusing on series and folder level or finding aids rather than item level description in order to provide faster cataloguing.Footnote40 In addition to any backlog, a record office such as the SRO has legacy data to contend with, which is not always fit for purpose. When Gateway to the Past was created, the priority was to input as much of the paper catalogue as possible to make it available online, rather than improving the existing catalogue data.

Adapting to changing research interests is challenging when access needs to be prioritized. It has been noted that the use of volunteers can provide a solution to some issues with MPLP. Volunteers are able to capture details while the archivist continues to make collections and series-level description, streamlining the archivist’s work.Footnote41 The detailed catalogue information for the Quarter Sessions records has been created by volunteers, as they can pay attention to details that an archivist may not be in a position to linger over. The volunteer-based catalogue-enhancement for the Quarter Sessions was very beneficial for one of the theses resulting from the project, even though it was not created with environmental research in mind. Therefore, volunteer catalogue enhancement can potentially provide a middle ground between MPLP and volunteer cataloguing in line with guidance by Kevin Bolton and Sue McKenzie: the archivist can provide the fundamental structure of the catalogue and ensure archival tenets are followed (including the principles of provenance, respect for original order and hierarchical structures), while the volunteers can fill in details to provide greater accessibility.Footnote42

Flooding and Drought provided some catalogue enhancement for SRO, but not entirely as expected. One unexpected example noted in interview with a record office archivist was that ‘we got a load of quite poorly described deeds described really well! And we weren’t anticipating that at all!’ However, Flooding and Drought did not result in the level of catalogue enhancement that had been hoped. The project had been intended to achieve this through the means of volunteer input, however when interviewed, an archivist from the record office observed that these two strands (catalogue enhancement and a volunteer project) ‘swapped emphasis,’ saying that:

it has been an interesting project, a good project. But it didn’t turn out to be what I expected it to be. It became, our main focus, our benefit for us, and a really good benefit, was a great volunteer project, which the volunteers enjoyed.

One reason for this is the thematic nature of Flooding and Drought. Williams identifies several different types of volunteer project that archives can run, which carry different benefits for an archive.Footnote43 Thematic projects are also usually the result of collaborations with external partners, as with Flooding and Drought with the UoL or The Staffordshire Place-Name Project with The Institute for Place-Name Studies at the University of Nottingham. Material was selected around a research theme rather than from one archive group, fonds, or series, and it was limited by the duration of a PhD programme. Because of selecting material based on a theme, which might be scattered, thematic projects are better suited to cross-cutting approaches, and less suited to systematic archive work. They are also more likely to be time-limited (as Flooding and Drought was) so cannot continue indefinitely to ensure completion of cataloguing.

The archivist described further reasons for the volunteer research becoming more important than the cataloguing. She explained that the material that SRO holds was very useful but did not fully match the expectations of UoL. This was partly due to a lack of specific ‘gem’ collections that were readily accessible. Some of the anticipated records were not ideal for the volunteers to work with, due to being in Latin or a particularly challenging hand and having few volunteers with the needed skills. Others were being used for other projects or research (as with Quarter Sessions and parish registers). She also mentioned that the PhD students became interested in different material than expected, potentially due to these difficulties. However, the lack of catalogue improvement does not mean similar projects are not valuable. Volunteer groups perform many functions to support archives, and there are other ways in which collaborations can support research and both organizational and sectoral objectives.

Conclusions

Although not without challenges, collaborative projects can deliver a wider range of benefits to archive services and their volunteers than those developed in-house, with additional benefits to academic partners. The objectives of all parties need to be discussed in detail at the outset and revisited across the course of the project to ensure that any ‘mission drift’ is acceptable to all parties. As this project involved regular supervisory meetings with the PhD students there was ample opportunity for shifts in emphasis to be discussed. The archival resources relating to flooding proved rather different from what had initially been anticipated by the academic initiator of the project, but nevertheless resulted in new understandings about everyday water management practices, which have contributed to historical hydrology research. The record office archivist observed that the project become an engaging volunteer project, but without the intended level of catalogue enhancement as different strands of the project ‘swapped emphasis’ (though it should be noted that these comments were not expressed as criticism).

The expectations in relation to volunteers also need to be borne carefully in mind, both so that their motivations are rewarded and the benefits they bring to the project are recognized. It needs to be considered that different types of projects may bring different strategic benefits, which needs to be recognized from the outset and to form part of the project design. Traditional in-house projects are more likely to attract experienced volunteers who already volunteer with the archive. Collaborative thematic projects can be highly stimulating for volunteers and attract a mixture of experienced volunteers seeking a new challenge and those that might not usually consider volunteering for an archive, bringing an injection of fresh enthusiasm to the service. Many of the volunteers expressed a desire to find new volunteer opportunities after the project finished (through both the survey results and directly asking the project coordinators).

Flooding and Drought demonstrates how collaborative projects can provide a stimulating and novel opportunity for volunteers. Every single Flooding and Drought volunteer who completed a survey reported having improved their knowledge, enjoyed themselves, been inspired to find out more and having met or socialized with people. Nearly all of them reported having developed skills, and most recorded an increased knowledge of Staffordshire (the others replied with ‘not applicable,’ and not all records studied by the volunteers related directly to Staffordshire). When asked about how volunteering has affected their knowledge and perception of Staffordshire, Flooding and Drought volunteers said that volunteering had made them more aware of the kinds of records that the archive holds, while others mentioned learning about agricultural practices and estate management. The Flooding and Drought volunteer who reported the longest period of volunteering with the record office replied that their involvement with the record office had developed their knowledge ‘in many ways — I could write a thesis on this.’

Academic-led volunteer projects in partnership with record offices can enhance the scope of research, add value to the experience of both volunteers and archivists by involving them in cutting-edge research, add impact to the research by demonstrating its real-life value and potentially by incorporating values beyond those of academia into the research design. By far the biggest benefit to the Flooding and Drought project of working with volunteers was the experience and enthusiasm of the volunteers who brought their own knowledge and desire to learn to the project. The project was successful in attracting a mixture of established and new volunteers and was helped by the experience, knowledge, and enthusiasm of both. Experienced volunteers contributed their skills and knowledge in many ways, including their familiarity with their local area, experience with the archive catalogue, palaeography skills and (in one case) understanding of Latin. New volunteers were eager to learn and very quickly became valuable assets to the project. The experience was reciprocal, with volunteers developing or gaining skills and satisfying their curiosity.

Some of the benefits and impacts of the project can go beyond those initially anticipated and some means of capturing evidence of both intended and unintended benefits needs to be built into the project design, to help participants reflect on what has been gained and to demonstrate value to funding bodies and other external stakeholders. Flooding and Drought was not intended as action research, so was not planned as a means of testing solutions to archival problems. The survey and interviews which formed part of the research were invaluable, but the use of an action-research methodology might have provided additional opportunities for reflection.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to my supervisors, Alex Buchanan and Neil MacDonald for their support throughout my PhD, and to Alex for advice in preparing this article. The project would not have been possible without the archivists at the Staffordshire Record Office, or their loyal and dedicated volunteers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Helen Houghton-Foster

Helen Houghton-Foster is a recent graduate of the University of Liverpool where she completed her doctorate in Environmental Sciences (joint with the department of History) as a Collaborative Doctoral Award with the Staffordshire Record Office. Her research focused on flooding and water management in Staffordshire circa 1550-1750. The experience of working so closely with record office staff and volunteers led her thesis to develop into an examination of researching environmental topics in UK archives. Prior to this, she completed a Master’s degree in Renaissance and Early Modern Studies at the University of York and worked in museums in York for several years. She is now the Volunteer and Digital Coordinator for Norton Priory Museum and Gardens in Runcorn, Cheshire.

Notes

1. Response to survey of Staffordshire Record Office volunteers, 2018 conducted for PhD research.

2. Caroline Williams, “The Impact of Volunteering in Archives,” 2018, 8.

3. Shaun Evans and Elen Wyn Simpson, “Assessing the Impact of Collections-Based Collaboration across Archives and Academia: The Penrhyn Estate Archive,” Archives and Records 40, no. 1 (2019): 37–54.

4. Alix R Green and Erin Lee, “From Transaction to Collaboration: Redefining the Academic-Archivist Relationship in Business Collections,” Archives and Records 41, no. 1 (2020): 32–51.

5. Williams, “Managing Volunteering in Archives: Report,” 2014.

6. Louise Ray, “Volunteering in Archives: A Report for the National Council on Archives,” 2009.

7. The National Archives, “Volunteering at The National Archives: The National Archives’ Approach to User Participation.”

8. Kevin Bolton and Sue McKenzie, “Guidance for Volunteer Cataloguing in Archives,” 2017.

9. Lindsay, “Volunteering in Collections Care: Best Practice Guide,” 2011.

10. Alice Harvey-Fishenden, “Learning from past droughts: reconstruction and understanding from Staffordshire,” PhD diss., University of Liverpool, 2021; Helen Houghton-Foster, “Learning from the Past: Exploiting Archives for Historical Water Management Research,” PhD diss., University of Liverpool, 2021.

11. Houghton-Foster, “Learning from the Past: Exploiting Archives for Historical Water Management Research.”

12. Lucy Veale, James P. Bowen, and Georgina H. Endfield, “’Instead of Fetching Flowers, the Youths Brought in Flakes of Snow’: Exploring Extreme Weather History through English Parish Registers,” Archives and Records 38, no. 1 (2017): 119–42.

13. D(W)1734/J/1614.

14. J.N. Bagnall, A History of Wednesbury, in the County of Stafford (Wolverhampton: William Parke, 1854), 158.

15. Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service, “Annual Report 2016/2017,” 2017; “Annual Report 2017–2018,” 2018; “Annual Report 2018–2019,” 2019.

16. Ibid.

17. Williams, “Managing Volunteering in Archives: Report,” 13; Ray, “Volunteering in Archives: A Report for the National Council on Archives.”

18. Williams, “Managing Volunteering in Archives: Report,” 13.

19. Ibid.

20. Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service, “Annual Report 2017–2018;” “Annual Report 2018–2019.”

21. Helen Lindsay, “Volunteering in Collections Care: Best Practice Guide,” 2011.

22. Research England, “REF Impact — Research England,” UK Research and Innovation, 2020.

23. “Clandage: Building Climate Resilience (@FloodandDrought) / Twitter.”

24. Williams, “The Impact of Volunteering in Archives,” 9.

25. Williams, “Managing Volunteering in Archives: Report,” 52.

26. Based on the statistics available through WordPress as the blog admin for floodanddrought.wordpress.com.

27. Alexandrina Buchanan and Michelle Bastian, “Activating the Archive: Rethinking the Role of Traditional Archives for Local Activist Projects,” Archival Science 15, no. 4 (2015): 429–51.

28. Annie Tindley, Micky Gibbard, and Alison Diamond, “Archived in the Landscape? Community, Family and Partnership: Promoting Heritage and Community Priorities through the Argyll Estate Papers,” Archives and Records 40, no. 1 (2019): 5–20.

29. Ruth Singer, “Criminal Quilts | Ruth Singer,” 2018.

30. Ibid.

31. Robert A. Stebbins and Margaret Graham, Volunteering as Leisure/Leisure as Volunteering: An International Assessment (Wallingford: CABI Publishing, 2004); Cantillon and Baker, “Serious Leisure and the DIY Approach to Heritage: Considering the Costs of Career Volunteering in Community Archives and Museums,” Leisure Studies 39, no. 2: 266–279.

32. Research England, “REF Impact — Research England.”

33. D603/H/1/2.

34. Val Bott et al., “Revisiting Archive Collections: A Toolkit for Capturing and Sharing Multiple Perspectives on Archive Collections,” 2009; Jon Newman, “Revisiting Archive Collections: Developing Models for Participatory Cataloguing,” Journal of the Society of Archivists 33, no. 1: 57–73.

35. D260/M/T/4/20-23.

36. Staffordshire Record Office accessions register.

37. Mark A Greene and Dennis Meissner, “More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing,” The American Archivist 68, no. 2 (2005): 210; Janice Tullock and Alexandra Cave, ‘Logjam: An Audit of Uncatalogued Collections in the North West,’ 2003.

38. Greene and Meissner, “More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing,” 212.

39. Greene and Meissner, “More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing”; Dennis Meissner and Mark A. Greene, “More Application While Less Appreciation: The Adopters and Antagonists of MPLP,” Journal of Archival Organization 8, no. 3–4 (July 2010): 174–226.

40. Explore York Archives Service, “MPLP,” York: A City Making History, 2012.

41. Jane Stevenson, “More Product, Less Processing? — Archives Hub Blog,” 2012.

42. See note 8 above.

43. Williams, “Managing Volunteering in Archives: Report.”

Bibliography

- Bagnall, J.N. A History of Wednesbury, in the County of Stafford. Wolverhampton: William Parke, 1854.

- Bolton, Kevin, and Sue Mckenzie. “Guidance for Volunteer Cataloguing in Archives.” 2017. Accessed March 17, 2018. http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

- Bott, Val, Newman, Jon, Grant, Alice, Reed, Caroline. “Revisiting Archive Collections: A Toolkit for Capturing and Sharing Multiple Perspectives on Archive Collections.” 2009. Accessed November 11, 2022. https://collectionstrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Collections-Trust-Revisiting-Archive-Collections-toolkit-2009.pdf.

- Buchanan, Alexandrina, and Michelle Bastian. “Activating the Archive: Rethinking the Role of Traditional Archives for Local Activist Projects.” Archival Science 15, no. 4 (2015): 429–451. doi:10.1007/s10502-015-9247-3.

- Cantillon, Z., and S. Baker; Cantillon and Baker. “Serious Leisure and the DIY Approach to Heritage: Considering the Costs of Career Volunteering in Community Archives and Museums.” Leisure Studies 39, no. 2 (2020): 266–279. doi:10.1080/02614367.2019.1694571.

- “Clandage: Building Climate Resilience (@floodanddrought)/twitter.” Accessed February 1, 2021. https://twitter.com/FloodandDrought.

- England, Research. “REF Impact - Research England.” UK Research and Innovation, 2020. Accessed August 8, 2021. https://re.ukri.org/research/ref-impact/.

- Evans, Shaun, and Elen Wyn Simpson. “Assessing the Impact of Collections-Based Collaboration across Archives and Academia: The Penrhyn Estate Archive.” Archives and Records 40, no. 1 (2019): 37–54. doi:10.1080/23257962.2019.1567307.

- Greene, Mark A., and Dennis Meer. “More Product, Less Process: Revamping Traditional Archival Processing.” The American Archivist 68, no. 2 (2005): 208–263. doi:10.17723/aarc.68.2.c741823776k65863.

- Green, Alix R, and Erin Lee. “From Transaction to Collaboration: Redefining the Academic-Archivist Relationship in Business Collections.” Archives and Records 41, no. 1 (2020): 32–51. doi:10.1080/23257962.2019.1689109.

- Harvey-Fishenden, Alice. “Learning from past Droughts: Reconstruction and Understanding from Staffordshire.” PhD diss., University of Liverpool, 2021.

- Houghton-Foster, Helen. “Learning from the Past: Exploiting Archives for Historical Water Management Research.” PhD diss., University of Liverpool, 2021.

- Lindsay, Helen. “Volunteering in Collections Care: Best Practice Guide.” 2011. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://www.archives.org.uk/ara-in-action/publications/best-practice-guidelines.html.

- Lucy, Veale, James P. Bowen, and Georgina H. Endfield. “’Instead of Fetching Flowers, the Youths Brought in Flakes of Snow’: Exploring Extreme Weather History through English Parish Registers.” Archives and Records 38, no. 1 (2017): 119–142. doi:10.1080/23257962.2016.1260531.

- The National Archives. “Volunteering at the National Archives: The National Archives’ Approach to User Participation.” Accessed April 18, 2018. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/volunteering-at-the-national-archives.pdf.

- Newman, Jon. “Revisiting Archive Collections: Developing Models for Participatory Cataloguing.” Journal of the Society of Archivists 33, no. 1, April (2012): 57–73. doi:10.1080/00379816.2012.666404.

- Ray, Louise. “Volunteering in Archives: A Report for the National Council on Archives.” 2009. Accessed May 5, 2018. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120215211544/http://research.mla.gov.uk/evidence/documents/volunteering-in-archives-nca.pdf.

- Singer, Ruth. “Criminal Quilts | Ruth Singer.” 2018. Accesssed October 22, 2018. https://ruthsinger.com/criminalquilts/.

- Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service. “Annual Report 2016/2017.” 2017. Accessed May 29, 2018. https://www.staffordshire.gov.uk/leisure/archives/about/AnnualReport/Annual-Report-2016-17.pdf;

- Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service. “Annual Report 2017 - 2018.” 2018. Accessed October 17, 2018. https://www.staffordshire.gov.uk/leisure/archives/about/AnnualReport/Annual-Report-2017-2018.pdf;

- Staffordshire and Stoke on Trent Archive Service. “Annual Report 2018 - 2019.” 2019. Accessed May 29, 2020. https://www.staffordshire.gov.uk/Heritage-and-archives/Documents/Annual-Report-Final-2018-19-web.pdf.

- Stebbins, Robert A., and Margaret Graham. Volunteering as Leisure/Leisure as Volunteering: An International Assessment. Wallingford: CABI Publishing, 2004.

- Stevenson, Jane. “More Product, Less Processing?” Archives Hub Blog. 2012. Accessed October 23, 2018 http://blog.archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/2012/01/05/more-product-less-processing/.

- Tindley, Annie, Micky Gibbard, and Alison Diamond. “Archived in the Landscape? Community, Family and Partnership: Promoting Heritage and Community Priorities through the Argyll Estate Papers.” Archives and Records 40, no. 1 (2019): 5–20. doi:10.1080/23257962.2019.1567305.

- Tullock, Janice, and Alexandra Cave. “Logjam: An Audit of Uncatalogued Collections in the North West.” 2003. Accessed September 11, 2022. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/archives/Logjamfullreport.pdf.

- Williams, Caroline. “Managing Volunteering in Archives: Report.” 2014. Accessed October 1, 2018. https://www.archives.org.uk/images/documents/ARACouncil/ARA_Managing_Volunteering_in_Archives_2014_Report_and_appendices_final.pdf

- Williams, Caroline. “The Impact of Volunteering in Archives.” 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018. http://www.archives.org.uk/images/Volunteering/Williams_The_Impact_of_Volunteering_in_Archives_2018.pdf.

- York Archives Service, Explore. “‘MPLP.’ York: A City Making History.” 2012. Accessed November 15, 2018. https://citymakinghistory.wordpress.com/the-project/mplp/.