ABSTRACT

This article examines which notions of nation and nationality are connected to the early pornographic film and how this, in turn, is connected to the production and distribution of early pornographic films. The article is primarily built on three unique Swedish court cases from 1922, 1932 and 1943, respectively, where illegal screenings of pornographic films were prosecuted, that is, long before the notion of ‘Swedish sin’ was created. By putting these three trials into a historical context, I am able to discuss how the pornographic genre is connected to nation and nationality through sexual geographies that included the ‘French film’, notions of German decadence as well as American immorality, although many of the films on trial were in fact Swedish made.

Introduction

On Friday 23 September 1932, an anonymous man entered a police station in Stockholm and reported that an indecent film was to be shown in the banquet hall at a household school located on Klara Södra Kyrkogata later the same evening. The anonymous man left two tickets for the evening’s screening, which was to start at 11:15 p.m. The print on the tickets said ‘The M. L. Club 3 Crowns’ (Case 403 Citation1932, Appendix 3, 1).Footnote1

Two police constables in civilian clothes named Liljeson and Roos were ordered to Klara Södra Kyrkogata for ‘a closer inspection of the film’s nature’. As they approached the address, an unknown man opened the street door without asking who they were and let them in. The constables continued to the fourth floor where the household school was located. A woman permitted them access but did not ask for the tickets. They hung their clothes in the hall and entered the banquet hall where around 30 people, of whom three were women, sat on Windsor chairs in front of a white screen. Liljeson and Roos took their seats, the light was turned down and the screening of four pornographic films began. Three of the films were titled in Swedish, while the fourth film was untitled. In total, the screening went on for 60 minutes (Case 403 Citation1932, Appendix 3, 2–4).

Per Jerneman, a photographer, was called in for questioning by the police a few days later. He confessed and took sole responsibility for everything, but at the same time he referred to the principle of private parties. When asked about the films, Jerneman told a story about how he, as he worked at entertainment park Gröna Lund in Stockholm during the summer of 1932, had been approached by a sailor who wanted to sell a ‘French film’ for 70 crowns. Jerneman saw the film and decided to buy it. The film had been divided into three parts, but he cut it into four parts, and later the camera and photograph company, Nerliens Fotografiska Magasin located on Kungsgatan in Stockholm, had added Swedish intertitles to this ‘French film’ (Case 403 Citation1932, Appendix 3, 6–7).

As in other Western countries, pornography was illicit in Sweden during the first decades of the twentieth century. To publicly screen a pornographic film was a criminalized act that could lead to two years of imprisonment. Despite this, screenings of pornographic films occurred in Sweden well before the legalization of pornography in 1971, even as early as in the 1910s and 1920s. One particular outcome of this precarious legal situation is that most of the history of the early porn film is surrounded by a hush-hush mentality, legally and morally, that has hampered historical reconstructions of distribution situations and screening contexts in Sweden, as elsewhere in the world. Since these early films were always silent, sometimes with translated intertitles, the actual origin was often unknown, leaving much room for speculation. However, as will be demonstrated in this article, this was not just speculation but instead built on preconceptions of nation and nationality connected to sex, sin and the relatively new film medium. The uncertain origins of the early pornographic film had, consequently, a transnational quality that transcended the concept of the national, both on a cultural level as well as on a material level. Hence, while research on transnational cinemas urges a shift away from the concept of national cinemas (see, for example, Kääpä Citation2014, 11–13), the inherent transnationality of the early pornographic film encourages a transnational approach that focuses on cultural flows which do not just include different types of material cooperation (film funding, co-productions, distribution) between countries but also an imagined cultural dimension where ideas are created and sustained. This approach connects with work on the sociology of nations such as Benedict Anderson’s imagined communities (Anderson Citation1983), but here the ‘imagined’ is floating and thus transnational.

This article is primarily built on three unique Swedish court cases from 1922, 1932 and 1943, that is, long before the notion of ‘Swedish sin’ was created. These court cases constitute a selection out of a total of five different court cases concerning the screening of illicit pornographic films in Sweden between 1921 and 1950. Although there is a temporal distance between the first and last cases, change is not the primary approach in this article; partly because the law and its assessment of illicit pornographic films are more or less constant during the period, and partly because, as we shall see, the different national notions linked to the pornographic film did not replace each other, but rather excited in parallel with each other during the period. The court cases and the attached police reports are, of course, limited in the sense that we mostly are presented with evidence from a position of authority, rather than from the perspective of those accused. Nonetheless, due to the hush-hush mentality surrounding the early pornographic film, these court cases are the best, if not the only, way to gain insight into these illicit practices, although a careful consideration of the moral stance in the source material is necessary. With the intention of supplementing the legal material, I have, in addition, searched the Swedish press using the three keywords ‘pornographic film’, ‘immoral film’ and ‘filthy film’ in order to see how the contemporaries discussed pornographic films in relation to nation and nationality circa 1900–1950.Footnote2 The aim of the article is to answer the following questions: what notions of nation and nationality are connected to the early pornographic film; how is this, in turn, connected to the production and distribution of pornographic films; and is it possible to trace the origin of these early porn films? First, however, I will put the early pornographic film into context, by discussing how the genre is connected to nation and nationality through sexual geographies.

The notions of sex and porn as connected to nation and nationality

The notions of sex and porn as connected to nation and nationality can be traced back to the old Greeks and even further. Michel Foucault makes a distinction between ars erotica and scientia sexualis as two different approaches to producing and teaching truths about sexuality. Almost all of the great civilizations (China, Japan, India, Rome) have utilized ars erotica – erotic art. In contrast, early modern Western societies used scientia sexualis – a scientific approach that stands in opposition to art and that discloses the truth about sexuality through confession. However, a shift in views on sexuality took place during the nineteenth and at the beginning of the twentieth century. This happened primarily because sexuality slipped out of the church’s moralizing grip, instead ending up under the magnifying glass of science, where it was medicalized as a truth in moralizing forms. This led to an increase in the number of existing sexualities, most of which were described as deviations from the norm – sex within marriage with the intention of having children – and as scientific findings on masturbation, prostitution, hysterics, homosexuality and heterosexuality trickled down as increasingly permanent truths, this cast suspicion on all forms of sexuality (Foucault Citation1990, 36–49 and 54–69; see also Kulick Citation1997).

At the turn of the twentieth century and in the coming decades, the medicalization of sexuality enforced a sense of nationality, mainly through the scientificization of eugenics at the time. However, this nationalization was foremost a popularization consisting of a mixture of physical anthropology, medicine and dismal cultural observations – probably most explicitly expressed in Madison Grant’s (Citation1916) then renowned study The Passing of the Great Race (Broberg Citation1995, 7–11, 19–24 and 45–52). Furthermore, loosely connected to these ‘scientific’ beliefs are technical innovations and the industrialization during the second half of the nineteenth century which contributed to the first production of commercial visual pornography with a wider spread than, for example, erotic literature in the eighteenth century, namely what would be termed ‘French postcards’. These were mass-produced, postcard-sized cards featuring black and white photographs of nude or semi-nude women, sometimes in ‘lesbian’ positions, and every so often featuring an Orientalist theme with naked women from European colonies in North Africa and Southeast Asia. These postcards were sold in local stores and tobacco shops, or could discretely be purchased from street vendors in Europe as well as in the USA. However, many countries, including Sweden and the USA, prohibited such ‘filth’ and, as with alcohol prohibition in the 1910s and 1920s, the decision to make French postcards illicit made their production into a profitable business and around 1910 some 33,000 people were employed in the French postcard industry (Hammond Citation1988, 10–11). Nonetheless, these postcards were far from always produced in France, simply because it was illegal to make, own and transport this type of erotic products. For instance, these postcards could not be mailed since they would be banned from delivery and possibly lead to prosecution for the sender (Citation1988, 11).

Even so, in Sweden, Europe and the USA, all cards of this sort came to be known as ‘French postcards’, no matter where they originated. Where, then, did this French inclination come from? Besides the fact that many of these cards were manufactured in France, there are several cultural explanations, one being the presence of racial biology that connected certain physical and cultural traits to certain ‘races’. Madison Grant, for example, divided the white (Caucasian) ‘race’ into three sub-races, where the French firmly belonged to the ‘Mediterranean race’ who were believed to be passionate and emotional (Grant Citation1916, 148–166; see also Kushner Citation2005, 215). Another cultural explanation is the importance of Paris as the centre for art during the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but also for decadence and politics, with the period ending up in La belle époque when the bourgeoisie reaped the fruits of economic development and made the boulevards of the cities, cafes, cabarets, art salons and concert halls their social space (Wires Citation1977). Likewise, American film scholar Eric Schaefer points out how certain nationalities have been sexualized and associated with the erotic during different periods. In the early twentieth century, France – or, more specifically, Paris – was clearly eroticized in both the USA and Sweden (Schaefer Citation1999). This type of national eroticism could be found in the pin-up genre during the interwar years with Swedish magazines like Parisien, and foreign luxury magazines with erotic elements, often boycotted, with titles such as Paris Plaisirs, La Vie Parisienne and Paris Magazine.

In addition, the French association can be connected to what anthropologist Annette Hamilton calls sexual geographies: that the world can be understood according to dichotomous ideas such as the ‘south’ is more fiery and sexual than the cold ‘north’. What transpires is a libidinalization of a country, a nationality or a whole continent (Hamilton Citation1997, 145). This, in turn, is close to what Edward W. Said has theorized as Orientalism, the Western vision of the East as a place that suggested ‘not only fecundity but sexual promise (and threat), untiring sensuality, and unlimited desire’ (Citation2003, 188). Consequently, the notion of sexual geographies spread more easily in mass-media societies, on a transnational level, not least because images and the film medium (along with the radio) emerged as dominant mass media during the interwar period.

Furthermore, this libidinalization of France through these postcards is dependent on the fact that France was leading in the development and commercial manufacturing of the camera and development techniques (Waugh Citation1996; Frizot Citation1998). Later, of course, the budding film industry would find its first dominion in France with what would evolve into world leading production companies such as Pathé Frères and Gaumont, and, for example, Georges Méliès (dir. Citation1897) would produce a film like Apres le bal [After the Ball], where a women undresses in front of the camera. These factors pushed the development further and lowered prices, and in the end the accessibility, for camera and projector equipment. Put together, these cultural, technical and commercial factors explain the geographical associations with the ‘French’ in French postcards, but the notion of France as fiery and decadent, built of envisioned images of a decadent Paris, is what symbolically became, in this case, the commercial selling point equivalent to what ‘Swedish’ later would become for the image of Swedish sin. That is, it did not matter whether the postcards were manufactured in France or not, because it was the ‘French’ connection that sold the cards as much as the content did. This sexual–geographical association would eventually travel to the film medium and ‘French films’ would become an equivalent for erotic or pornographic films.

Looking more closely at the film medium in general, and the early porn film in particular, there are a number of similarities making the porn film interchangeable in relation to nationality. The films are short (usually one reel), they are silent, they are shot in black and white, there are no or only a few close-ups and the light is either natural or otherwise the actors are rather poorly lit. Together with the fact that there existed a rather limited number of basic scenarios for the early porn film, it becomes difficult to identify its origin (Williams Citation1999, 58–61; see also Rotsler Citation1973).

A case in point is perhaps the earliest known surviving porn film, El satario (Anon., dir. Citation1907), which was, allegedly, made in Argentina (Williams Citation1999, 61). Allegedly, because there are no markers that let us identify it as Argentinian and some have also claimed that is was made in Cuba in the 1930s (Thompson Citation2007, 67–68), thus showcasing the interchangeability in both time and geography regarding early porn films. Then again, El satario fits neatly into the sexual geography for the ‘south’ as more sexually inclined. Related to this national interchangeability is Frederic Tachou’s assertion that the early French stag film was built on a system of signs specific to these films, which combines illusion and reality, and which enabled a development by which sexual fantasies of individuals could be exchanged with a more collective phantasmagoria (Tachou Citation2014). That is, the early pornographic film was dependent on an elusive transnational level when fantasies became collective, especially when films travelled ().

Figure 1. Still from El satario (Citation1907).

In comparison, while the film medium in itself is, conceivably, without nationality, the film culture, the content, the regional film industry and the promotion of these factors are usually related to the national. When it came to decadent and sensational scenes, Denmark excelled in a way that made ‘Danish sensation’ into a profitable selling point around the world in the 1910s, for example, with Asta Nielsen’s gaucho dance in Afgrunden [The Abyss] (Gad, dir. Citation1910) (Thorsen Citation2017, 94 and 177). The point here is that the national and nationality can be sold as trademarks in films that are on an open market, while the secret underground porn film had to rely on an imagined nationality, connected to an envisioned libidinalization of nation and nationality.

Returning to the Jerneman case in 1932, he told the police, when asked about how he acquired the illegal porn film, that he had been approached by a sailor who wanted to sell him a ‘French film’, which he then edited and added Swedish intertitles to. Does this mean that the four films now were perceived as Swedish? Nothing in the source material identified this as such, and none of the witnesses made any remarks in that direction. That is, not until Jerneman was called into questioning one week later, as a rumour had started that the ‘French films’ in fact were made in Stockholm (Case 403 Citation1932, Appendix 4, 1).

Confronted with these allegations, Jerneman confessed that he had made the four films himself. It turned out that he had bought a used film camera, and sometime during the summer of 1932 he had got drunk in his Stockholm apartment together with a male actor and two women he knew. Jerneman suggested that they should make an erotic film and the others agreed. Jerneman handled the camera and the man and the two women acted out the scenes that included penetration, masturbation and fellatio between the man and the two women, and ‘lesbian love’ between the two women, which in itself was illegal in Sweden at the time. Concerning the question of nationality, Jerneman added a telling detail in his confession, which demonstrates just how elaborate the forgery was. He had in fact drawn and affixed a fake French trademark to the film before he handed it in to the camera and photograph company for the Swedish intertitles (Case 403 Citation1932, Appendix 4, 1–2). This demonstrates how porn films were perceived as ‘French’ in Sweden at the time, that is, as a symbolic shorthand for sex and erotica, and the fake trademark confirmed this notion. In addition, it hid the real Swedish origin of the films, probably as a way to detract attention from the Swedish origins of the films in case they got caught for this illicit activity.

Stockholm’s City Court sentenced Jerneman to one month in prison for having screened films that broke the law on decency and morality. His female accomplice, who had leased the premises, was sentenced to pay a fine of 100 crowns (Case 403 Citation1932, Verdict, 5). The audience and the actors in these Swedish-produced porn films were not indicted, confirming that the law prohibited exhibition of this sort of illicit material, not the production as such.

Sexual geographies, class and the alleged foreignness of pornographic material

The ‘French’ inclination was established by 1932 but the perceived foreignness of the pornographic film is also connected to the larger film culture as it developed at the beginning of the twentieth century, and then not just to the French per se. The thinking in sexual geographies could be attached to a set of different transnational cultural conceptions that only had one thing in common, the alleged foreignness of the immorality of pornographic material. Already in 1909, a writer in the newspaper Göteborgs Aftonblad identified a regular film as ‘immoral’ due to its obscene sexual context, saying that this film ‘was more suitable for Havana than for Gothenburg’, thus exploiting the sexual geography of the south to explain that this sort of indecent behaviour did not belong in Sweden (Tristan Citation1909, 4). Furthermore, the decadence of the upper classes were exploited in connection to the sexual geography of the south. In 1928, the trade paper Biografbladet reported about a secret cinema in Paris that screened ‘dirty films’ for the upper classes. The police raided the cinema and discovered luxury cars parked outside and ‘ladies and gentlemen in evening dresses’ inside. The owner of the cinema was a rich ‘lady’ living in Nice who apparently operated several secret cinemas and bordellos located in France, and the trade paper further reported that tickets were 3000 French francs, and that this did not include champagne, concluding that ‘only depraved rich people could afford the luxury of a visit’ (Anon. Citation1928, 57).

However, France was not the only nation that was sexualized. During the 1920s, that is, parallel to the libidinalization of France, the young Weimar republic often stood in focus as the press and trade papers retold different scabrous stories connected to the ‘immoral’ German Enlightenment film that dealt with social issues such as STDs, drug use and homosexuality (see, for example, H. Citation1923; Vanja Citation1927, 12), but there were also stories published about hardcore pornographic films. One article described an incident at one of Berlin’s top premiere cinemas where a fired projectionist changed the reel during an ongoing regular screening to a pornographic film, locked the projector room and then left the cinema, after which the following scenes took place:

Describing the impression that the new film made on the decent and tidy part of the audience is not possible. For this new film was an accumulation of the most horrific pornographic scenes imaginable, such as one could hardly believe that any human being would lower himself to record. The audience was gripped by an incredible excitement. The orchestra immediately stopped playing. Shouts sounded that the show had to stop. Hysterical screams echoed from a box. The outraged crowd crowded towards the exits. However, many ladies remained seated and thus provoked indignant protests from the decent part of the audience through their shameless behavior. (Anon. Citation1921a, 346)

The ‘south’ and ‘decadent’ metropolises such as Paris and Berlin were not the only imaginations for Swedish detractors of film culture. During the interwar period, Anglo-American culture in general and Hollywood in particular became the targets of heavy criticism for spreading immoral ideals among the youth and women (Gustafsson Citation2014, 32–34). For example, in 1937 an evening newspaper reported about raids against secret cinemas in London that screened smuggled and uncensored films, implicitly from the USA. According to the article, the audience consisted of ‘a few curious but the vast majority are perverts that night after night enjoy the disgusting entertainment’. Furthermore, the tickets were priced at between 40 and 100 Swedish crowns, only allowing, yet again, the rich. The article also claims that the ‘demand is currently so great that the smuggled films are not enough, and there are persistent rumors circulating about secret studios for pornographic films even in England’ (Anon. Citation1937, 17). Here, the notion of the lowest levels of Anglo-American culture is confirmed, both by the presence of ‘perverts’ but also by the rumour that the Brits themselves now are making porn films.

Moving back to 1921, and the provincial Swedish town of Gävle, there is another case where the notion of Anglo-American culture is targeted as indecent. Here, the first known Swedish trial regarding pornographic films was held against a cinema owner called Karl Kaeyér. He was charged for screening a pornographic film on three occasions in the three small villages around Gävle. In November 1921, a report was submitted to Gävle’s police department claiming that Kaeyér had ‘for a male audience, demonstrated a forbidden, very lewd film, showing among other things sexual intercourse between a man and a woman, and also sexual offense committed between two women’. Kaeyér was called in for questioning by the police and confessed everything at once, claiming that the screenings had been for private parties consisting of men only. However, the appearance of secrecy and men who sneaked into the various countryside venues in the cover of night collapses considering the testimonies that, put together, pointed to the fact that all three of these ‘midnight’ screenings were placed directly after the public screenings with regular films and newsreels that had had a mixed audience of men, women and children. After the public show, everybody left the cinema and the doors were closed. Outside waited a number of men who had not seen the public show, and when children, women and some of the men went home, others stayed for the additional screening of the ‘funny film’. This in turn points to an ‘open secret’ that must have been known by a larger number of people than what reasonably might be considered an initiated circle. For instance, the three screenings were reported to have been visited by between 25 and as many as 80 persons (Case 267 Citation1922, Trial Protocol and Appendix F).

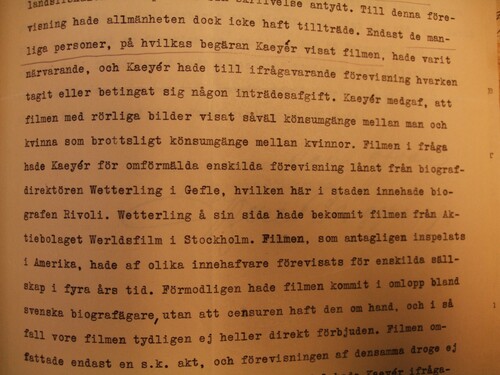

However, for the purpose of this article, two pieces of information surfaced during the questioning of Kaeyér. First, it transpired that the film in question ‘probably was filmed in America’, and that Kaeyér had borrowed it from the owner of Cinema Rivoli in Gävle. The owner had, in turn, supposedly obtained the film from ‘Werldsfilm Ltd’ in Stockholm. Second, the film had been in circulation for after-hours screenings for a period of four years (Case 267 Citation1922, Verdict and Appendix C) ().

Figure 2. Excerpt from the police report where Kaeyér states that the pornographic film was ‘American’ and was imported via Werldsfilm Ltd in Stockholm. Case 267. Citation1922. Uppsala läns norra domsaga. Dombok vårtinget. The Regional Archives in Uppsala.

The information that the pornographic film was American made and purchased from ‘Werldsfilm Ltd’ in Stockholm should be carefully considered. In fact, there did exist a short-lived distribution company called AB Världsfilm in Stockholm, which ceased operations already in 1920, but there is no evidence that the film in question was American. As with the French cards, the strong notion that everything decadent and immoral came from outside the boarders of Sweden prevailed, and this was probably exploited by Kaeyér. However, the North–South meridian, where the latter foremost was represented by the ‘French’ as an equivalent for sin and decadence, is here yet again completed by another sexual representation connected more to the media itself and to the industry of the inherently decadent film medium, here represented by a loose conception of ‘Hollywood’ but in fact built on another cultural stereotype, namely the European idea of American popular culture as commercial, inferior and dangerous (Alm Citation2002, 270). That is, as cultural ‘filth’ that had the ability to infiltrate and undermine the nation. Consequently, as the 1932 case also showed, our knowledge of the distribution and production of pornographic films is often based on hearsay, which in turn is often based on national perceptions and prejudices connected to sexual geographies.

Nevertheless, the Gävle case confirms the existence of a secret distribution system in which a forbidden film could circulate for four years in a relatively small geographical area without interference from the authorities. Shortly after the accusation of Kaeyér was made, the trade paper Biografbladet contacted Gävle police department, where they admitted that they had called in the owner of Cinema Rivoli – the owner of the ‘American’ film – for questioning. The cinema owner had, allegedly, ‘rolled films at midnight screenings for “full houses”, whereby ladies would also have been present’ (Anon. Citation1922, 333). The exact same pornographic film was even said to have been shown in Gothenburg – some 518 km from Gävle – and in other places at private screenings such as stag parties (Anon. Citation1921b, 2). However, the accusations against the owner of Cinema Rivoli in Gävle seems to have disappeared since there is no further record of it. Kaeyér, on the other hand, was sentenced to two months in prison for having shown a film which ‘must be deemed to have offended decency and morality, so that danger of others’ seduction has arisen’. He was also sentenced to pay 50 crowns in fines, which was turned into another eight days in prison (Case 267 Citation1922, Verdict).

Nazi propaganda and ‘perverse’ pornographic films

As French and American inclinations of sin and decadence continued to coexist on an imagined and transnational level in Sweden, the decadence of Interwar Berlin, with its somewhat sensational Enlightenment films that reached Swedish cinemas in the 1920s, had a profound impact on the imagination of the sexual geography of Weimar Germany. However, from 1933 onwards, Nazi Germany unintentionally inherited this sense of decadence and perversion, despite the fact that Nazi family politics primarily concerned itself with Volksgemeinschaft and pure and conservative family ideals (Heineman Citation1999, 1–16). Nonetheless, the inherent violent culture of Nazi Germany would pervert such chastity ideals and transform the male body of the soldier into a ‘fascist type’ formed by a secondary ego in the form of ‘body armor’, according to German sociologist Klaus Theweleit, that was toughened through beatings and by military drills. These male fantasies of the Third Reich were routinely put on display by the use of culture and art, not least via the naked male body but also by the increasingly tangible presence of soldier’s uniforms. The uniforms of Nazi Germany, and especially the uniforms of the SS, could therefore be perceived as an extension of the body armour that Theweleit examined as a fascist consciousness, leading among other things to a soldierly character that was unable to develop human relationships (Theweleit Citation1989, 143–153).

In her essay ‘Fascination Fascism’ first published in The New York Review of Books, Susan Sontag discusses the art of the Nazis – suggesting that it:

displays a utopian aesthetics – that of physical perfection. Painters and sculptors under the Nazis often depicted the nude, but they were forbidden to show any bodily imperfections. Their nudes look like pictures in male health magazines: pinups which are both sanctimoniously asexual and (in a technical sense) pornographic, for they have the perfection of a fantasy. (Sontag Citation1975, 12)

The cover already makes that clear. Across the large black swastika in the Nazi flag is a diagonal yellow stripe which reads ‘Over 100 Brilliant Four-Color Photographs’ and the price, exactly the way a sticker with the price on it used to be affixed – part tease, part deference to censorship – dead center, covering the model’s genitalia, on the covers of pornographic magazines. (Sontag Citation1975, 15)

These sadomasochistic fantasies, every so often connected to uniforms and Nazi Germany, were present in Sweden already during the interwar period. Swedish historian Andrés Brink Pinto has located these ideas in, among other places, leftist progressive medical literature, where the medical novelty of psychoanalysis is used to rationalize ‘deviant’ and ‘perverse’ sexual behaviours such as homosexuality, masturbation and sadomasochism. Consequently, class is thus used as an explanatory basis that partly explains the perversities of the upper class, and partly gives its explanation for how the Christian religion generates a distorted sexual life. While the perversities of the upper classes was a well-known phenomenon in Swedish society, as we saw earlier, the medical literature connected these ideas to questions about how Christian anti-sexualism (i.e. abstinence) had a particular impact on ‘military states’ such as Nazi Germany. The medical explanation was, perhaps not surprisingly, found in the suppression of normal (hetero)sexual drives, leading to homosexuality among soldiers, coupled with sadism and masochism as a result of the shared hardships on exercise yards and on the battlefields (Brink Pinto Citation2009, 402–403). In this way, the Nazis (and, in the long run, the whole German people) became pathologized on an imaginary level that intensified during the war.

For instance, in a translated article published during the ongoing Nuremburg trials in the evening newspaper Expressen in October 1946, Joseph Maier, who worked as an interpreter, and Sender Jaari, who worked for the Briefing and Research Section of the US Army Interrogation Division, described a number of high-ranking Nazi officials, including SS Obergruppenführer Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Chief of the Reich Main Security Office, and Julius Streicher, founder and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer, as sexually deviant individuals – ‘animals that belonged to the jungle rather than human civilization’ – based on the psychological causal explanations that were in vogue during this period. Streicher, for one, was said to have:

unleased his enthusiasm for the perfect Aryan superman to hide his own flaws. He himself was not exactly a representative of the human ideal he had set. Streicher was without a doubt the dirtiest man in Nuremberg. His collection of pornographic literature was the largest we have ever seen. (Maier and Jaari Citation1946, 8)

Thereafter, it was announced that there was going to be a screening of a ‘French film’ that was ‘around 50 years old’ but that ‘the subsequent films made in Stockholm were going to be more modern’. According to Lidblom’s testimony in the police report:

The French film was also very old and badly filmed with blurred images, but showed intimate relationships between both sexes, stripping scenes, etc. The film was equipped with Swedish inter-titles, which like in old movies came before the image. After […] a short pause, ‘The Stockholm films’ were screened. These were very ‘nasty’ and showed the sexual act between man and woman, different sadistic ‘treatments’, bared sexual organs, artificial penises, which were used by women, and also other similar ‘horrors’. ‘The Stockholm films’, which like the French film were silent films, probably consisted of two short films, since it was a short break between them. How the audience reacted during the screening of the latter films, Lidblom could not say since he felt very upset and even nausea. (Case 233 Citation1943, Appendix 2, 4–5)

In the following days, the four defendants were questioned by the police. It turned out that a cinema owner, Karl Söderström, and a white-collar worker, Ergon Weidenhayn, had collaborated to screen these films. Söderström specialized in screenings for ‘private parties’, and Wiedenhayn worked as a caretaker at Automobilpalatset, a combined car dealership and workshop in Stockholm. Weidenhayn gathered paying audiences among the male staff at Automobilpalatset, while Söderström acquired films and a location. Söderström in turn had contacted Emil Wallin, who owned a 16-mm projector and had access to two porn films made in Stockholm (). When the police asked Wallin how he had got hold of the films, he stated that he had borrowed them. However, the police seized the films at his brother’s glazing and framing shop a few days later, so we can suspect that Wallin and/or his brother were the actual owners. How Söderström found out about Wallin is unknown; both denied that they knew each other. But a witness, who had helped Söderström run the porn films at Blå Salen, claimed that he ‘had showed the same films at a stag party’ (Case 233 Citation1943, Appendix 2, 6–7 and 11–12). This means that the existence of these two Swedish-made porn films in fact were known, and that they circulated in Stockholm at private gatherings such a stag parties.

Figure 3. Automobilpalatset, a combined car dealership and workshop in central Stockholm, where the defendant Wiedenhayn worked and procured paying audiences to the illicit screenings of pornographic films and propaganda films. Photographer unknown.

The fourth defendant, the projectionist Axel Pettersson, was involved in the case because he owned the old ‘French film’ with Swedish intertitles. In fact, Söderström had received notice of Pettersson’s film at another stag party. When the police asked Pettersson how he had got hold of his film, he told them that one evening during the winter of 1937, when he was running a film at the cinema, an unknown man had come to the projectionist booth and wanted to borrow 50 crowns on a film that he had with him. Pettersson examined the film and saw that it was in good condition, and that it was of pornographic nature. Pettersson realized that the film was worth more than what the man asked for, and he lent the claimed sum. Pettersson asked where the man had got hold of the film but could not remember what the man had answered, probably abroad (Case 233 Citation1943, Appendix 2, 27–30). Once more, we have a story filled with secretive components, but the testimony also tells us that Pettersson had owned his film for six years. It therefore seems plausible that Pettersson’s ‘French film’, like the two ‘Stockholm films’, had circulated for years at private gatherings, not least based on Lidblom’s testimony that the ‘French film’ was very old and worn with blurred images (Case 233 Citation1943, Appendix 2, 4–5).

Furthermore, the story about the mysterious man who sold the pornographic film to Pettersson is quite similar to the one about how Jerneman was approached by a sailor who wanted to sell a ‘French film’, and where Jerneman tried to mislead the police by manufacturing a fake French trademark in 1932. The ‘southern’ origin of Pettersson’s ‘French film’ can therefore be questioned, not least on the basis that it had Swedish intertitles. These could, certainly, have been affixed afterwards by Pettersson, or by somebody else who had the necessary technical skills, but in the light of the fact that the rightful owners of these illegal films habitually tried so hard to distance themselves from their property, the doubt of the origin remains.

However, something that undermines this interpretation is the fact that the film was so old; not only worn but also that the intertitles came before the image – in order to explain them – just as they did in the early 1910s before film narration developed in the direction of classical cinema (Bordwell and Thompson Citation2010, 33). This does not give a final clarification about the origin of the film but, nevertheless, this ‘French film’ could possibly have been very old, perhaps even made in the 1910s, and thus could have been in circulation for a very long time. This gives an indication of the scarcity of such films and issues of access. In addition, the presumed innocence of earlier porn films could, with this film, be refuted, as the police report detailed its content:

This film shows both intercourse between a man and a woman in half naked condition and a woman who sucks on a male organ, and two women, who lies head to toe and lick each other on the genitals, and also two women, one of which has intercourse with the other in different positions by using an ‘artificial male organ’, tied to the woman’s waist. (Case 233 Citation1943, Appendix 3, 1)

The other association between porn films and nation in this case is, of course, the Nazi connection. These particular screenings of porn films were accompanied by German propaganda films, which were banned by Swedish censorship. According to a witness, Söderström had borrowed the two uncensored films from the German Legation in Stockholm, and according to the police report, Söderström had previously worked as a journalist, paymaster and printing manager, significantly at Den svenske nationalsocialisten, the Swedish equivalent to the Völkischer Beobachter in Nazi Germany, between 1936 and 1940 (Case 233 Citation1943, Appendix 2, 7). The ‘sticky nature’ of these pornographic films with ‘perverse’ and sadomasochistic elements, together with the Nazi sympathies of the organizer, are therefore almost unavoidably, regardless of the actual national origin, attached to an imagined pathological nature of Nazi Germany, present in Sweden during the period and even thereafter. Hence, this final court case contributed, by its very nature, to fuel these imaginations about the perverse Nazi.

The legal outcome of this case was that Stockholm’s City Court sentenced Weidenhayn as the instigator to pay 160 crowns in fines. He also lost his job due to the unwanted attention from his employer, Automobilpalatset. Söderström was sentenced to 120 crowns in fines, while Wallin was sentenced to 60 crowns in fines. However, Petterson was acquitted, as he was not aware that Söderström would screen his film publicly, but he lost his ‘French film’ as it was confiscated by the authorities (Case 233 Citation1943, Verdict, 6–7).

Conclusion

When examining all of the detailed content descriptions of the films in the police reports in these three cases, no film stands out as ‘French’, ‘American’, ‘German’ or ‘Swedish’ due to the content; quite the opposite, the sex acts – male/female intercourse, sucking, ‘lesbian’ love, the use of dildos – could be defined as the international standard fare of early porn films. The only film that appears to have stood out was one of the ‘Stockholm films’ with bondage that was screened together with German propaganda films in 1943, thus connecting it to a contemporary pathological view of Nazi Germany as ‘perverse’. The sadomasochistic nature of Nazi imagery became even more of an eroticized phenomenon after the Second World War. As Susan Sontag (Citation1975, 16) noted in her essay, fascism gained cultural potency from being illicit and forbidden, and this titillating aspect came to be exploited in both art films and exploitation films, such as Il portiere di notte [The Night Portier] (Cavani, dir. Citation1974) and Ilsa – She Wolf of the SS (Edmonds, dir. Citation1974).

Instead, as with the 1943 case, this article has demonstrated that the nationality of the current porn films is connected to different and coexisting sexual geographies, as well as conceptions about class rather than to specific national origins. These sexual geographies are foremost connected to a North–South meridian, where ‘French’ and in particular the metropole of Paris became an equivalent for sin and decadence. However, the German Wiemar Republic, and later Nazi Germany with its shared metropole of Berlin, did also constitute strong reminisces of sin and decadence in the interwar and war years (see, for example, Gordon Citation2008). The same could be said of the Swedish/European notions about an Anglo-American depravity, habitually connected to the imagined metropole of Hollywood, which spilled over on allegedly American-made porn films in the case of 1922 and in articles on pornographic films in the Swedish press.

In accordance with these imagined sexual geographies, we have seen examples of so-called French films, American-made porn films and Swedish-made porn films, which in several cases were transformed into ‘French films’, and in one case culturally connected to Nazi Germany. The legal source material has correspondingly presented us with several implausible stories of how these allegedly foreign films were covertly imported to Sweden as well as included testimonies about different secretive distribution systems within Sweden, even in a provincial town such as Gävle with its countryside surroundings. However, most of the evidence indicates that the majority, if not all of these films, were locally produced in Sweden and then transformed – using the sexual geography of the south – into, for example, ‘French films’.

Even so, regardless of their true national origin, in one sense these films were imported, namely through the imagined nationalization of sexual geographies where, for instance, ‘French’ was considered sexier and more daring, and the German inclination was thought of as more ‘perverse’ than what the, in most cases, actual Swedish origin could encompass at the time, thus balancing the untrustworthy transnational origin of the early porn films. It would be another 15–20 years before the concept of ‘Swedish sin’ would inherit the libidalinalization from the ‘French film’, although in reality they continued to coexist as expressions of different sexual geographies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 All translations from Swedish are mine unless otherwise noted.

2 The Swedish search words were ‘Pornografisk film’, ‘Osedlig film’ and ‘Snuskfilm’.

References

- Alm, Martin. 2002. Americanitis: Amerika som sjukdom och läkemedel. Svenska berättelser om USA åren 1900–1939. Lund: Studia Historica Lundensia.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities. London: Verso.

- Anon., dir. 1907. El satario. Argentina.

- Anon. 1921a. ‘En biografskandal. Obehagligt intermezzo i en Berlinska förstahandsteater.’ Filmbladet 16.

- Anon. 1921b. ‘Fängelse för osedlig film.’ Göteborgs Dagblad. May 6.

- Anon. 1922. ‘En sedlighetssårande film. Biografägare dömd till fängelse.’ Biografbladet No. 8.

- Anon. 1928. ‘Razzia på en hemlig snuskbiograf.’ Biografbladet 2.

- Anon. 1937. ‘Londonpolisen slår till mot olagliga “filmklubbar”.’ Aftonbladet. August 8.

- Anon. [Dick Lidblom]. 1943. ‘Pornografisk filmvisning: Lockbete för tysk propaganda.’ Social-Demokraten. March 12.

- Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. 2010. Film History: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Brink Pinto, Andrés. 2009. ‘Perversa direktörer och incestuösa pastorer: Skapandet av klass och sexuell normalitet i Populär tidskrift för sexuell upplysning och Stormklockan.’ Historisk tidskrift 129 (3): 397–409.

- Broberg, Gunnar. 1995. Statlig rasforskning: En historik över rasbiologiska institutet. Ugglan: Lund.

- Case 233. 1943. Stockolms rådhusrätt, avd 5. Stockholm City’s Archie.

- Case 267. 1922. Uppsala läns norra domsaga. Dombok vårtinget. The Regional Archives in Uppsala.

- Case 403. 1932. Stockolms rådhusrätt, avd 4. Stockholm City’s Archie, Sweden.

- Cavani, Liliana, dir. 1974. Il portiere di notte [The Night Portier]. Italy.

- Edmonds, Don, dir. 1974. Ilsa – She Wolf of the SS]. Canada.

- Foucault, Michel. 1990. The History of Sexuality. Volume 1: An Introduction. New York: Vintage Books.

- Frizot, Michel. 1998. ‘Light Machines: On the Threshold of Invention.’ In A New History of Photography, edited by Michel Frizot, 123–143. Colonge: Konemann.

- Gad, Urban, dir. 1910. Afgrunden [The Abyss]. Denmark.

- Gordon, Mel. 2008. Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin. Port Townsend: Feral House.

- Grant, Madison. 1916. The Passing of the Great Race or the Racial Basis of European History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Gustafsson, Tommy. 2014. Masculinity in the Golden Age of Swedish Cinema: A Cultural Analysis of the 1920s Films. Jefferson: McFarland.

- H. (pseudonym). 1923. ‘Pornografisk film. Berlinerbrev till Biografbladet.’ Biografbladet 1923: 4.

- Hamilton, Annette. 1997. ‘Primal Dream: Masculinism, Sin and Salvation in Thailand’s Sex Trade.’ In Sites of Desire, Economies of Pleasure: Sexualities in Asia and the Pacific, edited by Leonore Manderson and Margaret Jolly, 145–165. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hammond, Paul. 1988. French Undressing: Naughty Postcards from 1900 to 1920. London: Bloomsbury Books.

- Heineman, Elizabeth. 1999. What Difference Does a Husband Make? Women and Marital Status in Nazi and Postwar Germany. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kääpä, Pietari. 2014. Ecology and Contemporary Nordic Cinemas: From Nation-building to Ecocosmopolitanism. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Kulick, Don. 1997. ‘Är måsar lesbiska? Om biologins relevans för mänskligt beteende.’ Res Publica 35–36 (1–2): 221–232.

- Kushner, Tony. 2005. ‘Racialization and “White European” Immigration to Britain.’ In Racialization: Studies in Theory and Practice, edited by Karim Murji and John Solomos, 207–226. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maier, Jospeh, and Sender Jaari. 1946. ‘Sådana var alltså nazismens “övermänniskor”: Kaltenbrunner, Streicher, Sauckel och Frank “djungelmän” i Nürnberg’. Expressen. October 7.

- Méliès, Georges, dir. 1897. Apres le bal [After the Ball]. France.

- Murray, Thomas Edward, and Thomas R. Murrell. 1989. The Language of Sadomasochism: A Glossary and Linguistic Analysis. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Pia, Jack. 1974. SS Regalia. New York: Ballantine Books.

- Rotsler, William. 1973. Contemporary Erotic Cinema. New York: Ballentine Books.

- Said, Edward W. 2003. Orientalism. London: Penguin Books.

- Schaefer, Eric. 1999. Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Skoglund, Erik. 1971. Filmcensuren. Stockholm: PAN/Norstedt.

- Sontag, Susan. 1975. ‘Fascinating Fascism.’ The New York Review of Books. February 6.

- Tachou, Frederic. 2014. Et Le Sexe Entra Dans La Modernite: Photographie Obscene Et Cinema Pornographique Primitif, Aux Origines d’Une Industrie. Paris: Klincksieck.

- Theweleit, Klaus. 1989. Male Fantasies, Vol. 2: Male Bodies – Psychoanalyzing the White Terror. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Thompson, Dave. 2007. Black and White and Blue: Adult Cinema from the Victorian Age to the VCR. Toronto: ECW Press.

- Thorsen, Isak. 2017. Nordisk Films Kompagni 1906–1924: The Rise and Fall of the Polar Bear. Bloomington: John Libbey Publishing.

- Tristan (pseudonym). 1909. ‘I skrattspegeln.’ Göteborgs Aftonblad. November 13.

- UFA. 1939–1945. Die Deutsche Wochenschau [The German Weekly Review].

- Vanja (pseudonym). 1927. ‘Erfarenheterna I ett land där revolutionen sopade bort censuren.’ Dagens Nyheter. February 20.

- Waugh, Thomas. 1996. Hard to Imagine: Gay Male Eroticism in Photography and Film from Their Beginnings to Stonewall. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Williams, Linda. 1999. Hard Core: Power, Pleasure, and the ‘Frenzy of the Visible.’ Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Wires, Richard. 1977. ‘Paris: La Belle Époque.’ Conspectus of History 1 (4): 60–72.