ABSTRACT

As this study reports, in times of global health crisis interactions between users on social media platforms such as Pornhub seem to form solidarity links that grow into global digital communities. This article applies quantitative, qualitative, and network analysis to the comments of a sample of 166 videos identified as belonging to the ‘COVID-19 porn genre’. The analysis leads to the quest for a community of practice that builds and negotiates shared meanings and values, and demonstrates forms of complicity and purpose, and forms of recognized hierarchical structure. The study builds under the shadow of a platformization dynamics that drives the whole environment of Pornhub penetrating the social relations between users. The article contributes to a discussion on online communities and, specifically, the possibility of the rise of a global community based on solidarity on porn sites.

Introduction

In March 2020, a coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization (Adhanom Citation2020) with lasting global and massive consequences. The measures and their impact disrupted the global economy, and the lockdowns to prevent the spread of the coronavirus altered the patterns of media consumption. In many countries, working, learning, and all sorts of entertainment activities moved online (Guld Citation2020). Under these circumstances, social media platforms thrived and often became central environments for social interaction. Since the remote work by Shirky (Citation2011), it is a common trope to understand social media platforms as instruments for social interaction, informal cooperation, and even political mobilization; but the COVID-19 pandemic increased vastly the digital communicative activity (Nguyen et al. Citation2020). This increase was not homogeneous around the world; it created deeper social inequalities, while it also contributed to the growth of certain NSFW cultural platform imaginaries, as is the case of ‘Only Fans’ (Van der Nagel Citation2021). But globally, such online traffic surge has gravitated towards streaming services, news sources, and porn sites (Wright Citation2020).

Pornhub, the self-proclaimed world-leading platform of adult video, promptly changed its policies of access, offering free premium memberships first for the countries affected most by lockdown measures such as Italy (on 12 March 2020), France, and Spain (16 March 2020); and then shifting it to the whole world (24 March 2020) as the pandemic spread globally. The policy shift could be seen as a viral marketing strategy of the company, but the platform users also demonstrated a high level of resilience and interest: Cerdán Martínez, Villa-Gracia, and Deza (Citation2021) contrasted the search trends to confirm the alignment with reports published by Pornhub, according to which users’ engagement with the platform peaked. At the same time, Pornhub showed attempts to raise health and safety awareness and immediately adapted the newly posted contents to the timely demands of the audiences – growing a trend of ‘COVID-19 porn’ (Pornhub Citation2020).

This article explores to what extent, in times of global health and economic crisis, the human networks connected through social media platforms such as Pornhub might highlight forms of solidarity forming digital communities. The idea of community includes at least a double sense: on one side is the designed platformizing intention of the company that incorporated the disclaimer ‘Pornhub community’ at the beginning of every single video, kidnapping the meaning of the word. On the other side is the user’s practice interacting and participating in the comments sections of the videos, building what appears to be a human social mesh of interactions. This article approaches Pornhub as a platform that has successfully adopted features available in other social networking sites fitting it within the platformization dynamics (Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018); but the article also approaches Pornhub as a community of practice that builds and negotiates socially shared meanings and values through digitally enabled communicative interactions.

The quantitative, qualitative, and network analysis of the comments from 166 videos from the COVID-19 porn genre (Belinskaya and Rodriguez-Amat Citation2021) shows that a community of practice of shared values and meanings, complicity, and hierarchy might be emerging. Be it because the interface of Pornhub is designed for it or because there is an unsatiated human thirst for civic contact, the question of online communities and the arousal of solidarity networks on platformized porn sites is served.

From networked society to platformized porn

The complex nature of digital platforms makes them a challenging object of study. The notion of platformization is also an opportunity to open debates (involving ownership, extension, power) that are typically invisibilized in the social media research strand, often focused on their societal impact. In the field of platforms and platformization, there are a variety of perspectives and concepts that have covered multiple facets of the complex process. These perspectives have linked platformization with an overwhelming body of literature on social media and cultural change (among many others Sutherland and Jarrahi Citation2018; Poell, Nieborg, and van Dijck Citation2019; Rieder, Coromina, and Matamoros-Fernandez Citation2020; Chia et al. Citation2020).

The concept of platform, closely associated with Web 2.0, describes it as a space for personalized interactions between users provided by the digital infrastructure that not only collects but monetizes the data produced by those users (Poell, Nieborg, and van Dijck Citation2019). Platformization as a process was introduced ‘to describe the growing integration of digital platforms’ business models, infrastructures, algorithms, and the surrounding practices into every facet of society’ (Chia et al. Citation2020, 4). The emphasis on the process immediately includes the society as a whole and the changes in societal structures in terms of technological advances, policies, business models, competition, and everyday practices: ‘In this process, platforms construct new value regimes and economies’ (Van Dijck, Poell, and De Waal Citation2018, 24).

The process of platformization is seen by Poell, Nieborg, and van Dijck as:

… the penetration of the infrastructures, economic processes, and governmental frameworks of platforms in different economic sectors and spheres of life. And in the tradition of cultural studies, we conceive of this process as the reorganisation of cultural practices and imaginations around platforms. (Citation2019, 5–6)

Pornhub has allegedly been a platform per design since its start, but its features and affordances also have changed over time. Its interface enables social interaction that includes the possibilities of posting self-made videos, likes, views, rewards, subscription systems, and comments (Belinskaya and Rodriguez-Amat Citation2021). This shows that the industry is openly embracing the most successful features of other social media platforms. Pornhub follows the Tube principle by combining amateur content with videos starred by what the platform classifies as semi-professional models and pornstarsFootnote1 (Pornhub Citation2020b). This organization of creators is similar to bottom-up YouTube communities, curating and releasing previews or excerpts from professionally made videos (described by Burgess and Green Citation2018).

Tyson et al. explored the features of Pornhub as a platform, and the factors of popularity such as ‘profile views received, users subscribed to, wall comments sent’ (Citation2015, 440), among others. The authors pioneered the research on the social-media-like dynamics of platforms such as Pornhub, claiming that in social media research ‘the adult domain remains largely untouched’ (Citation2015, 437). Half a decade later, this article aligns with the work that has already been done while it digs deeper into the community of users of Pornhub. To do this, it is also convenient to explore a little further how the notions of community unfold in the context of platformized societies.

Platformized societies, algorithms, and connected communities

Indeed, social media and digital platforms constitute an integral part of modern post-industrial society. The supranational tech corporations (built as platforms) such as Facebook, Twitter, or Google-owned YouTube have been considered instrumental in redefining forms of public engagement, deliberation, inclusion, civic action, and solidarity (Castells Citation2008). The whole internet (often used as a generic for Web 2.0) has been too often treated as a utopian rebirth of the Habermasian concept of public sphere: a promised low-barrier entry and the mitigation of structural symbolic fences such as class, race, gender, and ‘border crossing without mobility’ (Shaw Citation2017, 140). Such idealization of the internet evolved into a participatory and a co-productive environment also provided a promise for ‘imaginary cosmopolitanism’ (Zuckerman Citation2013). In this sense, the concept of ‘network society’ (Castells Citation2000) seemed to anticipate a new stage of developments of human organization granted by new technological advances, and allowing the decentralization of the community and distributed decision-making processes.

However, the dream of a globally connected network of citizens in equality has been critically nuanced over the years. Habermas (Citation2006) himself or Van Dijk (Citation2020) among other scholars have pointed to it as a fragmented, or as platformised society:

After a decade of platform euphoria, in which tech companies were celebrated for empowering ordinary users, problems have been mounting over the past three years. Disinformation, fake news, and hate speech spread via YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook poisoned public discourse and influenced elections. (Van Dijk Citation2020, 1; original emphasis)

As much as the notion of public sphere updates to adapt to the new transforming and platformized communication ecosystem, an idea of social community remains close to the core. McMillan and Charvis in 1986 defined four elements that constitute the ‘sense of community’ that were further developed by Rotman, Golbeck, and Preece (Citation2009): membership or feeling of belonging; influence; fulfilment of various needs; and shared emotional connection. The participatory online culture of Web 2.0 has also been theorized by scholars concerning user communities (Burgess and Green Citation2018, among others) – ‘Yet the term “community”, in relation to these sites [with user-generated content], appears to cover a range of different meanings’ (Van Dijk Citation2020, 45). On the apocalyptic end, authors like Byung-Chul Han (Citation2021) have dismissed the idea of online community and preferred to talk about ‘hysteria of survival’ as a mechanism that dehumanizes society, leading to the sacrifice of solidarity and community. But some other authors have paid attention to describing online communities either underlining the needs of a shared cause (Hirsch Citation1990) or mutual interests (Rotman, Golbeck, and Preece Citation2009). More recently, and within the context of social media platforms, a discussion of the idea of community progressively emerges as moving away from the transcendental notion of ‘shared project’ or ‘shared cause’ or ‘shared interest’ to highlight the functionally phatic idea of connection as interaction. In this sense, for instance, Shaw argued: ‘Cosmopolitan connectivity between members of digital networks […] results in “solidarity by connectivity” rather than “by origin or by shared values”, distancing and isolating individuals from active interaction in society’ (Citation2017, 146). Connectivity is seen as an extension of nodes of communication, which can be considered as a rather reductive, abstract, and superficial experience. The research into YouTube networked communities by Rotman, Golbeck and Preece revealed that ‘larger communal interaction patterns were rarely demonstrated. For the users, these singular interactions were enough to form a feeling of belonging and attachment to the amorphous community’ (Citation2009, 47).

Fisher sees solidarity as an ‘emergent product’ of various repeated interactions, meaning that ‘within an online community, where social capital and mutual trust exist, community members are likely to show solidarity in the form of loyalty and willingness to do things for one another’ (Citation2019, 289). Narayan insists that social media can provide a necessary communicative space for such emerging solidarity ‘while promoting the patterns of interaction that shape our information practices and is easily integrated into one’s social fabric, making it an ideal candidate for a public sphere’ (Citation2013, 36). Also, more recently, Airoldi (Citation2021) has suggested that algorithm-enabled social connections are constructed by, and construct culture and society at the same time. Regardless of the algorithm activity, then, the network of interactions can be understood as developing a community of networked users in interaction that develop a form of shared solidarity that builds towards that notion of public sphere.

The case of coronavirus porn

Pornhub’s global marketing campaign at the beginning of the pandemic has been connected to a record traffic increase in March and April 2020 (Pornhub Citation2020a). The campaign started with the granting of free premium access and the launching of the informational campaign ‘staying at home’. Users and contributors to the platform were asked to use the hashtag #StayHomeHub, and part of the resulting traffic revenue was donated to Italian hospitals (Silver Citation2020). Verified users were also granted a 100% pay-out as well, without the usual Pornhub commissions. After that, Pornhub itself stated that in Italy the traffic went up to 57%. Globally, by March 2020, the world traffic increase – correlated with the implementation dates of the lockdown measures – had risen by 30% too (these are data according to Pornhub Citation2020a).

Pornhub has referred to timely search-term increases, such as the surge of ‘The Joker’-related terms coinciding with the global release of the Oscar-awarded film (Pornhub Citation2020). Similarly, in early 2020, search terms on Pornhub saw a significant increase in coronavirus topics: ‘coronavirus porn’ or ‘covid’ exceeded 9.1 million searches (Mestre-Bach, Blycker, and Potenza Citation2020) and so have shown Cerdán Martínez, Villa-Gracia, and Deza (Citation2021). Pornhub has actively intended to construct a socially accepted brand (Gorbatch Citation2019); but its actions have also been systematically put into question. The New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof (Citation2020) published an exploitative article (Turner Citation2020) sharing concerns on privacy, misogyny, or abuse related to revenge porn practices and the Pornhub responsibility. Criticized by Grant (Citation2020), Kristof also mentioned issues involving the monetization of rape porn, or the use of spy cams, and the possibility to download the content from the webpage – as this would allow videos to be re-uploaded and spread incessantly.

As a response to the public discussion triggered by the article, in December 2020 Pornhub implemented a three-strand change in the platform publication policies: first, videos could only be uploaded by verified users. Until the implementation of a new verification program, all of the unverified users’ uploaded content would be held inaccessible. Second, to eliminate the download button and only allow download under payment conditions within the model program, adding control over the re-uploads of any deleted content. And third, the moderation system was expanded to include an additional layer of moderation that would discover, flag, and ban any potentially illegal content (Pornhub Citation2021).

Methodology

This article builds from previously published research about the video contents and the genre of ‘COVID-19 porn’ (Authors 2021). The networks of interactive activity among members of the Pornhub community are explored by using those same previously collected data. This has allowed the authors to track the impact of the new Pornhub policies, which changed the sample slightly, as will be described in the following results.

After checking the changes in the sample against the new platform policies, this study analyzes the comments of the available videos (166 videos) from a triple perspective: a qualitative analysis of the algorithm-provided, most-relevant comments of the users (not the video contents); a quantitative textual analysis of the most commonly used words and emojis in those comments; and a network analysis of the relationships between users through the comment conversations. This serves to identify the relational network between users, and the comment contents.

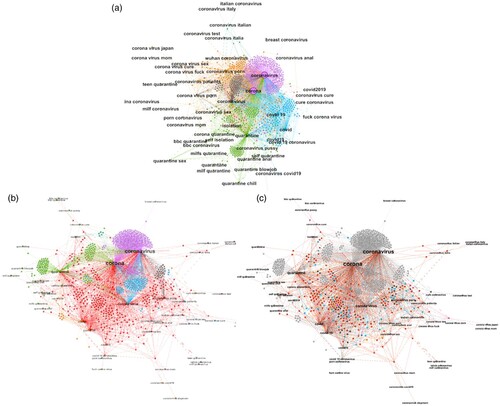

The data were collected on 3 April 2020 using a set of search keywords that led to the videos provided by the platform algorithm: ‘coronavirus’, ‘coronavirus porn’, ‘Coronavirus Patients’, ‘Coronavirus Quarantine’, ‘Coronavirus Sex’, and ‘Covid 19’. The initial search brought up around 7000 videos, many repeated because they appeared in several searches (3468 unique videos). The hashtags associated with all of those videos helped design a sampling process based on hashtag affinity: the combination of COVID-19-relevant hashtags with videos that contained three or more of them. This operation delivered a final sample of 285 videos. shows how the 3468 unique videos related to the hashtags. The network graph (a) shows 3468 video nodes grouped around hashtags (every dot is a video, hashtags seen as text). The videos are organized around seven modules of keywords: the modularity communities are statistically identified following Blondel et al.’s (Citation2008) model that consists of calculating the strongest probability of connection between two points and grouping them, forming clusters that are graphically represented as the colours of the edges. The translation of the probable connection into a community of interaction is common practice in social media-related research (Guerra et al. Citation2013). The 285 videos shown in red in indicate the sample (for more on this, see Belinskaya and Rodriguez-Amat [Citation2021]) ().

Figure 1. (a) Network graph of 3468 video nodes grouped around hashtags. (b) The 286 videos of the first sample (red). (c) All of the videos collected (grey), the videos of the sample still working (red), and the videos not working (colours; see Table 1).

Table 1. Network of non-working videos of the initial sample (reasons provided by platform).

On 1 February 2021, the sample of 285 was searched again to identify any videos that had been disabled after the new Pornhub policies. A total of 166 videos were still available; but the rest had been deleted, disabled, or not verified, or were pending verification, private, or unavailable due to newly implemented country restrictions. This new sample (c) still serves for the analysis of the comments; as do the metadata of the disappeared videos.

The results’ section starts with a review of the absent videos. After that, the analysis focuses on the relational data obtained through the engagement of the commenting users. These data are analyzed as a network of comments and users. A quantitative textual analysis identifies the most frequent words and emojis in the comments. The qualitative analysis starts with documentation of the comments available from the automated collection. The comments were taken apart and then put back together in a more meaningful way (Creswell Citation2015, 156). This process helped the coding process that led to the posterior categorization following the lines suggested by Elliott (Citation2018). This coding process is a way of processing the high density of the comments’ textual data and metadata. The purpose of coding was to identify forms of interaction between the participants in the comment conversation. The codes then led to the development of categories pointing to expressions, appeals, and interactions to identify complicities between users. The analysis was driven by a specific attention paid to comments mentioning coronavirus, or any other forms of connection or complicity. That qualitative analysis increased in depth as soon as combined categories could show patterns of discourses that revealed forms of solidarity, of complicity, and of shared community values.

These three forms of analysis complement each other, too. The network analysis (relational data) complements the quantitative analysis (word and emoji frequencies), and the qualitative analysis (attributes–meanings–complicities) that sheds some light on the ‘nature’ of those social interactions. The combination of these three forms of analysis allows one to identify patterns that represent norms, solidarity, and relationships built through the commenting interaction process, and leads to the identification of key traits compatible with the process of platformization. The platformization of Pornhub is a process that penetrates and also shapes some relations between participants.

This article deals with online data. This means that the findings have some limitations and that we took some ethical considerations. Among the limitations are the dependence on the algorithm and the issues related to data-borrowing from the internet that edges ethical difficulties and concerns. This research, this small sample, and this very specific context of COVID-19 porn can only know what is presented by the algorithm, and must ignore the features concealed by it. The comments collected are also determined by the site criteria of relevance, which might not be the most significant for the project. We cannot deal with all of the comments, and therefore can only approach issues like repetition, horizontal participation of users, and deeper networks within these limitations. However, and in spite of these conditions, this exploration is a stimulating inspiration for further research.

Users identified through the data collection were unaware of the research because their comments are in the public domain – accessible without a password – and freely available on the platform. Still, the ethics process has been thorough, and the decisions are made in a tension between the precision of the references to the available data and then making sure that in no identifiable way can the material be traced back to single individuals. This article does not mention any single user(name) and the qualitative and literal textual analysis of the comments was safely kept. Following the guidelines of the Internet Research Association (Franzke et al. Citation2020) in the writing, the authors have made sure that the reproduced verbatim is untraceable to the origin, authorship, or context (absence of author or identification of the video the text is responding to). Furthermore, the data obtained have been only borrowed for this specific research, and will be made accessible for further research exploration following the principle of the open data policy. In doing this, still, the authors commit to maintaining the identity of any user anonymous, and to prioritizing the protection of their individual integrity.

Findings

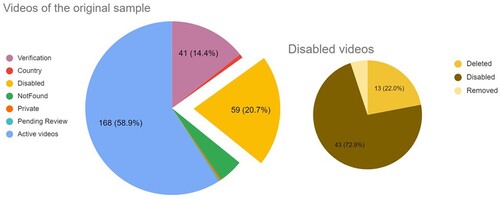

The initial data collection (April 2020) was planned early after the first lockdowns, expanding globally during March 2020. The initial stages of the research were oriented towards the understanding of the features of the user activity around what was known as ‘COVID-19 porn’ (Authors 2021). This article is part of the second phase of that programme, and focuses on the users’ interactions. However, due to the Pornhub policies implemented in December 2020, only 60% of the original videos remain available. Fourteen per cent of those early videos were not verified and at the stage of the second data collection (February 2021) only one video was pending review. Also, one of the videos went private. Two videos were ‘not accessible from your country’, which indicates a change in the policies of access and distribution: from these two videos, one was posted by a still existing profile located in Australia with no videos on it. The user’s profile of the other video is currently unavailable.

The 13 ‘Not Found’ videos return the same technically oriented message: ‘Error Page Not Found’. This message leads to the belief that the videos have changed URL location or that the user might have deleted them, or re-posted them under another title (see for a graphic representation of the two samples).

Figure 2. Videos available and absent in February 2021 in relation to the earlier sample of April 2020.

Removing videos from the platform might not help the number of viewers, but re-uploading them can help increase subscription: surges of viewership related to keywords – as described – relate the interest of viewers to trending topics; and a video that is successful because it contains a particular hashtag or a particular word in the title earns subscribers. Re-uploading with new titles and new hashtags can therefore be a strategy for users to gain subscribers, too. As described by Rieder, Coromina, and Matamoros-Fernandez (Citation2020), subscription and viewership are factors that intervene in the remuneration of the users; more the former than the latter – this is what the Pornhub model program does.

The stability of subscribers suggests that around particular profiles some clusters of users, fans, could have formed; and if these subscribers interact (for instance, in the comments), then networks forming communities can start to emerge.

Network analysis

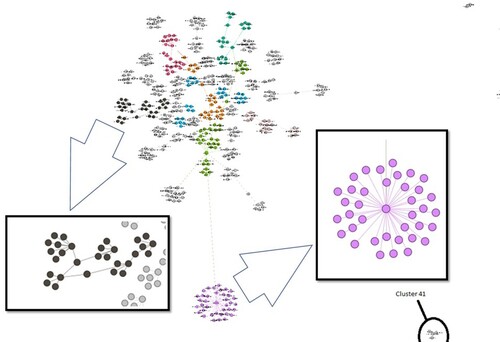

Considerations about the relations between users and posts (539 user nodes) show the presence of groups of comments–users (488 links–edges) forming differently shaped networks of participants in the comments section of the videos. The core of the graph representing those relations can be seen in ; and the examples of clusters formed by the network of interactions.

Figure 3. Network of comments and interactions between users in the videos of the sample. Cluster 8 (enhanced, right side) is isolated from the core network. The network enhanced (left side) shows a cluster of interactions between videos within the core network; and Cluster 41 (circled, bottom right) is an example of cluster isolated from the core network.

There are 57 modular clusters or ‘communities’: in the graph, each is identified by a different colour (). This section is a clear feature of how most of the clusters work: the central node is the user who posted the video, and the comments include that same user illustrating who has responded to the comments. This is a recurrent shape that can include more or fewer users, showing the participation of the same user posting as the respondent. The image only shows the few clusters closest to the core; but around this centre there are multiple smaller clusters, similar to cluster 41 (, far bottom right, circled). They are formed by one video-post and three or four comments. These networks are linear and do not generate conversation-like interactions. These smaller clusters are abundant in the outside edge of this network graph.

On other occasions, like cluster 8 (, bottom centre, enhanced), the network has another shape. The cluster is formed by 38 nodes and is also almost isolated from the core of the network – it is only connected through a user ‘unknown’ in cluster 48. Multiple users (37 users) comment to a central post that is non-responsive. In this case, the network could be showing that the video was posted by a celebrity with a lot of fan-followers; and most of the users are not even expecting a response.

Yet for another case (, bottom left, enhanced), the network stretches because several users intervene in multiple comments, building what looks like a conversation spreading across the nodes, with some repeated nodes. The comments form a modular cluster out of the 57 nodes. This is closer to what this research is looking for: users repeating across comments establishing a conversation that carries, and accumulates, building a form of shared knowledge with it. The forthcoming qualitative analysis of the attributes of the comments can show whether such shared knowledge builds towards some forms of solidarity, trust, and social capital accumulated through the culture emerging from these networks.

Quantitative analysis

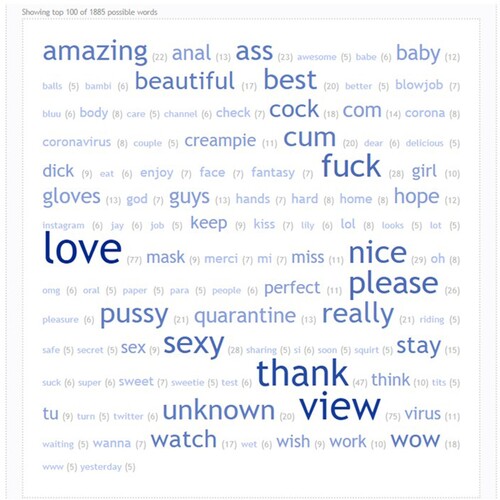

As a transition compromise between the analysis of the network of users and comments, and the qualitative analysis of the meanings of the comments, it is useful to quantitatively explore the wording in the comments. In this case, the word-frequency count is particularly illustrative (). The 100 most used words across all of the texts available in the comments (extracting the stop words and some meta-words including ‘comments’, ‘http’, or ‘videos’) are shown in this visualization.

The word ‘view’, still very prominent, stands as an artefact from the ‘video views’ but has been left because it also points to the users’ requests. There is an abundance of words showing support, appreciation, and general positive attitude such as ‘love’ (the most used, 77 mentions) or ‘thank’, ‘merci’, ‘amazing’, ‘perfect’, ‘enjoy’, ‘awesome’, and ‘wow’. The COVID-19-related sample also shows a line of often-used words referring to the cloud of associated meanings: coronavirus–corona, gloves, quarantine, mask, virus. Of course, sex-related words extend from ‘please’ in its extensive meaning associated with pleasure to body parts, sensations, and practices. Some words point at gender-discriminatory uses, too.

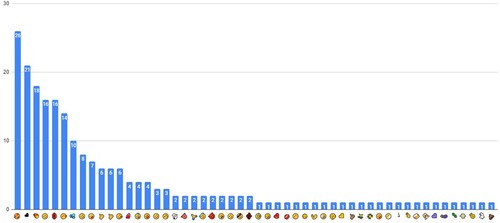

In line with this analysis of word frequency, shows the quantified use of emojis. The emoji references to body parts are very few, mostly pointing to facial traits: kiss, lips, or tongue. Instead, it seems that emojis point to emotions or sensations (fire, or heart in multiple colours) and contribute to build a friendly (rather than explicit or sexual) complicity via wink, thumb up, smile, hearted eyes, or kiss. Many of these emojis are repeated within the messages, which might slightly alter this very rough count; and obviously, not all emojis always carry the same meanings.

Qualitative analysis

The analysis of the comments themselves started by a first approximation to the wording and construction of the messages. The analysis started by paying particular attention to mentions of coronavirus or similar, but soon expanded from their searching for forms of social connection. The texts of the comments were read and labelled, identifying diverse elements in every text including expressions of emotion, appealing to other users, responses, any trace of identification, or complicity. These elements led towards the identification of forms of community-related categories that were consistently identified, and later to forms of solidarity.

Solidarity: emerging forms of complicity

Complicity between the users and between the participants appeared immediately in the analysis of the comments. The COVID-19 conditions of lockdown, global pandemic, and sanitary measures not only inform the contents of the videos but also inform the presence of tag-words in the comments: ‘#FUCKCORONAVIRUS ![]() ’. To a certain extent, the COVID-19 conditions also inform networks of solidarity growing among the members – this is what we have labelled as coronavirus complicity.

’. To a certain extent, the COVID-19 conditions also inform networks of solidarity growing among the members – this is what we have labelled as coronavirus complicity.

This analysis of the comments shows multiple forms of interactions between users that turn around COVID-19: for instance, appealing to general awareness and sharing global wishes, such as ‘take care of yourself’(Q1)Footnote2, pointing also to the context and conditions related to coronavirus (users discussing the relevance of coronavirus and global panic).

Other examples show supportive, compassionate and accompanying tone messages to users that suffer from COVID-19 (‘i hope you feel better soon’[Q2]; ‘get well[Q3]’) or mention lockdown-related vulnerability such as loneliness (‘lonely people like me’[Q2]).

Some COVID-19 related messages, however, include an ironic turn that sometimes presents itself as clean and innocent (‘Ok who else just looked for “coronavirus” to check what would appear’Footnote3), whereas in other cases COVID-19 slips the discussion towards the erotic field (‘No coronavirus can leave us without sex’) or adding playfulness to the safety measures by commenting on the video that social distancing rules require at least six feet between the actors (Q5).

All of these diverse types of comments seem to have in common that they build a form of closeness between users through the context of COVID. This is what in the analysis was categorized as coronavirus complicity. More detailed attention to the comments shows that comments build other forms of complicity between participants: gender complicity and national complicity are only two of the most prominent.

For the examples of gender complicity, it must be insisted that this research stems from the default search engine in heterosexual mode. Topics and gender stereotypes emerge more often than not within this heteronormative dual frame. This was already noted by Tyson et al. (Citation2015). In whatever case, the analysis has detected subtle complicities among female profiles: for instance, calling each other ‘girl’ or ‘sis’ in the conversation seems to appeal to proximity and to a form of understanding: ‘Hihihi thank you sis![]() ’. In other cases, this complicity includes empowering through comments about the body, and positive support, mentioning the good technical quality of video and a ‘perfect pair of tits’(Q9).

’. In other cases, this complicity includes empowering through comments about the body, and positive support, mentioning the good technical quality of video and a ‘perfect pair of tits’(Q9).

National complicity is also present in the comments. A user from Italy stated that he/she has uploaded the video to stay closer to other people in his/her country(Q6). The collection point of the sample was late March, when Italy was suffering the full swing of the COVID infection.

However, the national complicity extends also towards the language. Whereas most of the comments still are in a dominant English language, a diversity of languages has been detected in the comments (Italian – the second most popular – Spanish, French, Tagalog [Philippines] Russian, Portuguese, German, or Finnish). Comment languages tend to correlate with the language and declared country of the user who posted the video. This continuity between comment language and users’ language posting is one of the factors that coincide with the interactions graph insisting that comments and users tended to form relatively closed comment circuits around the videos. This is a form of national order that shows the network; but still it is a form of reproducing a national/linguistic sense of community.

All of the described forms of complicity are indicative of at least a very basic level of respect and of solidarity between the users – no aggression, no discouragement, no criticism; and instead multiple forms of encouragement, solidarity, confession, and declaration of physical attraction.

A community of shared knowledge and shared values

The network analysis has shown a relational link between the multiple user nodes; and while those links were rather weak, there are two aspects worth considering understanding the attributes of these – first is the level of social norms or values, and second is the structure of relations between participants. If there is a form of community it is because there are sets of norms shared and practised and negotiated among the users; and as in any community, it is expected that the relations among them are not entirely horizontal but that some hierarchy might be revealed from the practice.

The level of the social norms adopts multiple shapes: from the uses of language to the recurrent repetition of traditional – and sometimes comfortably and recurrently conservative – practices. However, sometimes, cases of lucidity also emerge among the comments, and smartly deconstruct the apparently popular genre of step-family quarantine porn. One of the commentators (Q7) shares the feeling of being disturbed by this genre, which, however, in his/her opinion normalizes the fantasy of intercourse with a stranger.

Among males, there are also forms of communication that emerge clearly appealing to their capacity or their intentions. In one of the cases, there was a slight disagreement between two (supposedly) males commenting on the body of a female: one preferring curves but still stating that the forms of the model were ‘too much’, and the second commentator agreeing but claiming desire to ‘pound her ass’(Q8). This is one of the comments that also points at a relative form of body-shaming, and it is exceptional all along within the analyzed comments.

Indeed, all across the analysis, the aroused attitude of the comments tends to praise and to positively express support and admiration for the contouring bodies exhibited on the videos. This support is not always the same: from explicit declarations of love/attraction (such as invitation to stay in quarantine together[Q11]) to words of encouragement inviting for more (‘please more of … ’[Q12]); and then the tension between the direct expression of the sexual wishes towards the model (‘I want to have sex with [your ass]’[Q13]), and the less invasive and almost intimate personal confession of arousal (‘I almost came in my pants’). Among these ranges of expressions, the underlying accepted feeling of arousal and sexual intention crosses all of the activity, and it becomes natural and common practice to express it with words.

In their confessional openness, users also seem to agree on the claim for authenticity as a form of truth: fake behaviours, filters, or unnatural body shapes are signalled and discouraged (‘please stop with the snapchat filters’[Q14]), whereas authentic behaviours are the material of confession and uncontrollable body reactions are supported.

These sets of norms do not emerge spontaneously. The practices of a structured (at least lightly) community help them. Users set up and practice and reproduce relationships among them, and this is the whole purpose of the community: many of these relations are egalitarian, and the users show forms of horizontal understanding. Among others, users call each other in first and second-person pronouns: you and me, or address the models by the first name (‘Jess was on fire’). This is a horizontal form and a form of circumventing – or even negotiating – authority, if required.

The celebrity/model user structure

These categories are defined by Pornhub (see Belinskaya and Rodriguez-Amat Citation2021). At the top of such a hierarchical system of relations are the celebrities. They are known by the participants as a form of shared knowledge within the Pornhub community culture. They are referred to mostly in the third person: ‘Chanty has such a hot and fit body!’. Celebrities not only embody the top of a hierarchical structure – as pornstars – but are also a product of a process of platformization that has enthroned such internal pyramidal structure by enabling algorithms based on sets of criteria of relevance. Pornstars are not only encouraged (‘liked this video, super hot’) but also asked to respond to the demands of the users in terms of clothes, make-up, surroundings, and poses (‘try to sexy talk and make up’). In the comments, the models respond to those requests: ‘Absolutely! I will make more tonight ![]() ’.

’.

Such a celebrity system, and the awareness of users and comments, point to another level of discussion. Users, and the videomakers, know how the platform works, and bring the comments towards a meta-level of technical production. There are mentions to the location of the videos (‘ … please have more outdoor public creampie fucking??’) or to the focus (‘Your videos are perfectly in focus, well rendered and the fucking is perfect’). This is parallel to the authenticity that is claimed as a shared value: the understanding here is that whereas the bodies are expected to spontaneously and sexually react in an authentic manner, the preparation of the videos requires a level of craft that is everything but natural. The models also participate in those technical interactions: ‘You’re right, my 2nd camera moved out of focus … Next time!!’.

Users that promote themselves in the comments establish a form of consumerist relation with the other users; instead of setting horizontal relations, they set relationships masked by the expression of some fundamental desire. These users intend to monetize their comments and their relationship with other users. This is another example of the platformization process penetrating the network of social interactions. Self-promotion (or rather spam) comments create a de-solidarizing effect:  ‘ Fuck me somebody!

‘ Fuck me somebody!  visit free gift – [web page address]’. Some of them are intended to build a social network with aspirational aims (‘Agree! And you can rate my video, I'm a beginner.

visit free gift – [web page address]’. Some of them are intended to build a social network with aspirational aims (‘Agree! And you can rate my video, I'm a beginner. ![]() ’, ‘Follow my channel’, ‘consider subscribing to my profile, thanks!’).

’, ‘Follow my channel’, ‘consider subscribing to my profile, thanks!’).

There are also multiple comments referring to (other) social media: offers to follow users on Snapchat or Twitter (‘Just sent you a Twitter follow request. Keep in touch’); or discussions that involve having been exiled from other platforms with tighter behavioural moderation criteria (‘this isn’t youtube, it’s Pornhub, nobody cares,’). There are also known common practices and a set of skills acquired from activity in other platforms: ‘DM me if you wanna collaborate’ or ‘private message me’.

All these forms of the complex inter-connection of Pornhub with other platforms, in this case through the behaviour of the users themselves, clearly resonates with that media convergence that engages viewers ‘immediately with multiple media simultaneously when landing on a pornographic video streaming site’ (Keilty Citation2018, 340). This is a design strategy, and also a symptom whatever the relations between the users, and even if those might mask or be genuinely driven by pure human solidarity, they are only enabled, steered, and managed through the design features of affordances established, moderated, and perverted by the platformized reason.

Conclusions

The analysis of the comments under the COVID-19 porn videos points to a specific form of a shared language between the users. There is something more than the wording, too: some of the interactions show that there are conversations between common participants that expand across videos. The textual analysis demonstrates how these interactions carry shared meanings: from the world complicity of persons in lockdown to the complicity of persons sharing sexual arousal. These connections are embedded in the aprioristic conditions of the COVID-19 porn sample, but they enhance other forms of pragmatic connection detected (gender, or national complicity). An extended complicity that slowly and discretely slips into forms of richer contact, and shared cultural meanings and values.

These indicators seem to resonate with previous research that already pointed to an early scent of a community (Belinskaya and Rodriguez-Amat Citation2021); and in this case, the common ground includes practices, knowledge, and values that substantiate this idea of a community built through links that might be of a fundamental solidarity that involves a sort of naked and transgressive form of human trust and of shared social capital.

Among the very human reactions and explicit language, the ties of close contact are alive and somehow seem to build a common communicative place: a territory where admiring and expressing desire is permitted and a community liberated from some traditional or conservative values could be emerging. However, among those reactions, gender discrimination still appears and the stereotypes of the patriarchal society seem to have gained, again, permission to be.

Other expressions, instead, take a novel shape: the ‘like me’ or ‘follow me’ messages, or the calls for continuity on other platformized sites. These messages do not fit in the porn languages – they are imported and implanted from an extended platform culture. Such transposition of messages dangerously assimilates Pornhub to any other participatory Web 2.0 social media site that moderates its contents; and this favours Pornhub. Whatever bad press the notion of platformization might carry (copyright, ownership, ringfencing, censorship, data protection, data traffic, or privacy issues among many others), Pornhub benefits from it; because the design and affordances of social participation are part of a platform-laundering strategy that assimilates Pornhub to other less body abusive platforms like Twitter or Facebook. In other words, the pretending to be a social media platform design of the Pornhub interface humanizes a tube network where the unregulated porn industry is allowed to possibly exploit bodies globally.

This research has shown that the comments of the videos present deep connections between users that build forms of proximity and trust with each other. Of course, the small sample of COVID-19 porn might have generated an artefact: the common cultural meanings might be provoked by the pandemic situation – users needed to express solitude and desire for sexual proximity. It could also be that this community, detected through the analysis, is the product of the platform interface – it is known that platforms design their sites to promote interaction and to monetize active engagement and count visits, interactions, and clicks. The network analysis has shown a clique of nodes but they might be just a hashtag community that will fade with the COVID-19 porn moment. Yet this research must be read as a promising start. Beneath the global tentacles and the difficult wires of the porn industry, and below the platform economy and the culture of the exploitation of the emotional interactions, there is a community of human solidary members that still wish each other to stay safe while being aroused.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 The article uses the terms ‘model’ for verified amateur performers and ‘pornstar’ for professional performers engaged in studio work (see https://www.modelhub.com/blog/8601). These two terms replicate the classification provided by Pornhub and kept in the users analysis by Belinskaya and Rodriguez-Amat (Citation2021), and both correspond to ‘porn performer’ as a more established term (see Pezzuto Citation2019).

2 In order to grant users’ anonymity, quotes have been decontextualized and codified.

3 The quote was rephrased to grant anonymity.

References

- Adhanom, Tedros. 2020. ‘WHO director-general’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020’. World Health Organization (11 March 2020), at https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020. March 11. Accessed 11 January 11, 2022.

- Airoldi, M. 2021. Machine Habitus: Toward a Sociology of Algorithms. New York. John Wiley & Sons.

- Belinskaya, Yulia and Joan Ramon Rodriguez-Amat. 2021. ‘Strip-Teasing COVID-19 Porn: A Promising Silhouette of a Community, or the Dark Alley of a Platformized Industry?’ First Monday 26 (10). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v26i10.11078

- Blondel, Vincent D., Jean-Loup Guillaume, Renaud Lambiotte and Etienne Lefebvre. 2008. ‘Fast Unfolding of Communities in Large Networks.’ Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment 10: P10008.

- Brantner, C., Joan Ramon Rodríguez-Amat and Yulia Belinskaya. 2021. 'Structures of the Public Sphere: Contested Spaces as Assembled Interfaces.' Media and Communication 9 (3): 16–27.

- Burgess, Jean and Joshua Green. 2018. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Castells, Manuel. 2000. ‘Toward a Sociology of the Network Society.’ Contemporary Sociology 29 (5): 693–699.

- Castells, Manuel. 2008. ‘The new Public Sphere: Global Civil Society, Communication Networks, and Global Governance.’ The aNNalS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (1): 78–93.

- Cerdán Martínez, Víctor, Daniel Villa-Gracia and Noelia Deza. 2021. ‘Pornhub Searches During the Covid-19 Pandemic.’ Porn Studies 8 (3): 258–269.

- Chia, Aleena, Brendan Keogh, Dale Leorke and Benjamin Nicoll. 2020. ‘Platformisation in Game Development.’ Internet Policy Review 9 (4): 1–28.

- Creswell, John W. 2015. 30 Essential Skills for the Qualitative Researcher. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Elliott, Victoria. 2018. ‘Thinking About the Coding Process in Qualitative Data Analysis.’ The Qualitative Report 23 (11): 2850–2861.

- Fisher, Greg. 2019. ‘Online Communities and Firm Advantages.’ Academy of Management Review 44 (2): 279–298.

- Franzke, Aline Shakti, Anja Bechmann, Michael Zimmer and Charles Ess. 2020. ‘Internet research: Ethical guidelines 3.0.’ Association of Internet Researchers.

- Gorbatch, Alina. 2019. ‘Pornhub case study: 5 marketing steps that made it #1’. Awario. https://awario.com/blog/Pornhub-case-study-marketing/. October 29. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Guerra, Pedro Calais, Wagner Meira Jr, Claire Cardie and Robert Kleinberg. 2013. ‘A measure of polarization on social media networks based on community boundaries.’ In Seventh international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media.

- Guld, Ádám. 2020. ‘Project (I) Solation–Everyday Life and Media Use During the COVID-19 Pandemic.’ Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Communicatio 7: 25–41.

- Grant, Melissa. 2020. G. ‘Nick Kristof and the Holy War on Pornhub’. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/160488/nick-kristof-holy-war-Pornhub. December 10. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 2006. ‘Political Communication in Media Society: Does Democracy Still Enjoy an Epistemic Dimension? The Impact of Normative Theory on Empirical Research.’ Communication Theory 16 (4): 411–426.

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2021. The Palliative Society: Pain Today. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hirsch, Eric L. 1990. ‘Sacrifice for the Cause: Group Processes, Recruitment, and Commitment in a Student Social Movement.’ American Sociological Review 55 (2): 243–254.

- Keilty, Patrick. 2018. ‘Desire by Design: Pornography as Technology Industry.’ Porn Studies 5 (3): 338–342.

- Kristof, Nicholas. 2020. ‘The Children of Pornhub. Why does Canada allow this company to profit off videos of exploitation and assault?’ NY Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/04/opinion/sunday/Pornhub-rape-trafficking.html. December 4. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Mestre-Bach, Gemma, Gretchen R. Blycker and Marc N. Potenza. 2020. ‘Pornography use in the Setting of the COVID-19 Pandemic.’ Journal of Behavioral Addictions 9 (2): 181–183.

- Narayan, Bhuva. 2013. ‘From Everyday Information Behaviours to Clickable Solidarity in a Place Called Social Media.’ Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 5 (3): 32–53.

- Nguyen, Minh, H. Jonathan Gruber, Jaelle Fuchs, Wille Marler, Amanda Hunsaker and Eszter Hargittai. 2020. ‘Changes in Digital Communication During the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for Digital Inequality and Future Research.’ Social Media + Society 6 (3): 1–6.

- Pezzuto, S. 2019. ‘From Porn Performer to Porntropreneur: Online Entrepreneurship, Social Media Branding, and Selfhood in Contemporary Trans Pornography.’ About Gender 8 (16): 30–60.

- Poell, Thomas, David Nieborg, and José van Dijck. 2019. ‘Platformisation.’ Internet Policy Review 8 (4): 1–13.

- Pornhub. 2020a. ‘Coronavirus Insights’. Pornhub Insights. https://www.Pornhub.com/insights/corona-virus. March 23. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Pornhub. 2020b. ‘Model partner program | How to make money on Pornhub’. https://www.pornhub.com/partners/models. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Pornhub. 2021. ‘Our Commitment to Trust and Safety’. https://help.Pornhub.com/hc/en-us/categories/360002934613 Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Rieder, Bernhard, Oscar Coromina and Ariadna Matamoros-Fernandez. 2020. ‘Mapping YouTube: A Quantitative Exploration of a Platformed Media System.’ First Monday 25 (8).

- Rodeschini, Silvia. 2021. ‘‘New Standards of Respectability in Contemporary Pornography: Pornhub’s Corporate Communication.’.’ Porn Studies 8 (1): 76–91.

- Rotman, Dana, Jennifer Golbeck and Jennifer Preece. 2009. ‘The community is where the rapport is–on sense and structure in the youtube community.’ In Proceedings of the fourth international conference on Communities and technologies, 41-50.

- Shaw, Kristian. 2017. ‘‘Solidarity by Connectivity’: The Myth of Digital Cosmopolitanism.’ In Cosmopolitanism in Twenty-First Century Fiction, 139–178. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shirky, Clay. 2011. ‘The Political Power of Social Media: Technology, the Public Sphere, and Political Change.’ Foreign Affairs 90 (1): 28–41.

- Silver, Curtis. 2020. ‘Coronavirus Searches Spike On Pornhub As We Self-Isolate With Porn And Toilet Paper’. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/curtissilver/2020/03/13/coronavirus-searches-spike-on-Pornhub-as-we-self-isolate-with-porn-and-toilet-paper/. March 13 2020). Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Sutherland, Will and Mohammad Hossein Jarrahi. 2018. ‘The Sharing Economy and Digital Platforms: A Review and Research Agenda.’ International Journal of Information Management 43: 328–341.

- Tiidenberg, Katrin. 2021. ‘Sex, Power and Platform Governance.’ Porn Studies 8 (4): 381–393.

- Turner, Gustavo. 2020. ‘Opinion: New York Times Fights Pornhub With Emotional Pornography’. XBIZ Industry Source. https://www.xbiz.com/news/256091/opinion-new-york-times-fights-pornhub-with-emotional-pornograph. December 4. Accessed February 22, 2021.

- Tyson, Gareth, Yehia Elkhatib, Nishanth Sastry and Steve Uhlig. 2015. ‘Are People Really Social in Porn 2.0?’ In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 9 (1): 436–444.

- Van der Nagel, Emily. 2021. ‘Competing Platform Imaginaries of NSFW Content Creation on OnlyFans.’ Porn Studies 8 (4): 394–410.

- Van Dijk, Jan. 2020. The Network Society. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell and Martijn De Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wright, David. 2020. ‘COVID-19: Expectations and Effects on children online. Executive summary’. UK Safer Internet Centre. https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/health/healthy-schools-london/awards/sites/default/files/covid-19-expectations-and-effects-on-children-online_0.pdf. Accessed 22 February, 2021.

- Zuckerman, Ethan. 2013. Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection. London: WW Norton & Co.