ABSTRACT

Grammatical encoding has been suggested to be driven by communicative efficiency – a balance between production ease and communicative success. Evidence for this view comes from studies indicating that speakers balance their use of morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions with respect to animacy. However, these studies have not taken cues in the discourse context into account. In a picture-description task, we investigate the influence of animacy on the morphosyntactic encoding of grammatical functions in Swedish transitive sentences. These sentences are produced in discourse contexts with additional information about grammatical functions. We find various morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions (e.g. SVO word order and case marking) to more frequently be used when the object referent is animate. Speakers thus balance their use of cues to grammatical functions, even when the discourse context is informative about those functions. These findings provide direct evidence for the view that grammatical encoding is influenced by communicative efficiency.

Introduction

Speakers often have multiple ways to express a message linguistically. For example, a transitive event can either be expressed by an active clause (e.g. The dog bit the boy) or a passive clause (e.g. The boy was bitten by the dog). The linguistic expression of an event can thus differ with respect to its grammatical encoding – the assembly of its morphosyntactic structure (Bock & Levelt, Citation1994; Levelt, Citation1989). A central area of research in speech production is concerned with the factors that underlie such grammatical encoding choices. Many studies show that speakers often encode their message in a way that reduces production costs (see, e.g. MacDonald, Citation2013 for a review). However, speakers also want to be understood. Their utterances need to contain enough information for the recipient to be able to recover the message. It has thus been suggested that speakers’ choices also are influenced by the goal to successfully convey the message: Ultimately, speaker choices are driven by a balance between the goal to reduce production costs, and the goal to successfully communicate the message by providing enough information for the listener (e.g. Buz et al., Citation2016; Hörberg, Citation2016; Kurumada & Jaeger, Citation2015). There are different information types that in principle can play a role in communication, ranging from concrete, morphosyntactic cues in individual sentences, to abstract information-structural patterns in the discourse context. Although there is some evidence to suggest that speakers’ choices are influenced by communicative success, much of this has either been correlational (e.g. based on data in natural texts, see e.g. Hörberg, Citation2018; Lee, Citation2006; Temperley, Citation2003) or based on studies low in ecological validity (e.g. sentence recall studies, see Kurumada & Jaeger, Citation2015; Tanaka et al., Citation2011). To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that take information in the discourse context into account. In the present study, we investigate whether speakers are inclined to encode their message in a manner that provides enough information for the listener, even when the utterance is produced in a discourse context that provides additional information regarding the correct interpretation. More concretely, we ask whether speakers tend to balance their use of information on the sentence level, even when there is information regarding the correct interpretation on the discourse level. To this end, we investigate variations in the morphosyntactic encoding of grammatical functions in transitive sentences in Swedish, primarily focusing on word order, and how this encoding is affected by animacy. This is done using an open-ended picture-description task with structural priming, in which participants describe pictures depicting transitive events. Crucially, these events are presented in discourse contexts that facilitate interpretation of potential sentence-level ambiguities.

In the following, we give an overview of studies investigating factors that influence grammatical encoding, with a particular focus on the encoding of grammatical functions in transitive sentences. We then present the aims of the present study with reference to the sentence structure of Swedish transitive sentences and how the word order of Swedish transitives is affected by information-structural considerations.

Factors influencing grammatical encoding

As outlined above, some studies suggest that grammatical encoding is influenced by communicative efficiency, that is, by an optimal balance between production ease and communicative success (e.g. Buz et al., Citation2014, Citation2016; Hörberg, Citation2016; Kurumada & Jaeger, Citation2015; Piantadosi et al., Citation2011, Citation2012; for a discussion, see Jaeger & Buz, Citation2018; but see Caplan et al., Citation2020). Speakers thus avoid using redundant morphosyntactic information in order to reduce production costs, but only to the extent that it does not compromise the listener's ability to decode the message (Hörberg, Citation2016, pp. 204–205). For example, omission of an optional function word such as the complementiser that reduces production costs, but might result in an ambiguity. A sentence such as The reporter believed the president lied, for example, is temporarily ambiguous. Before the verb of the embedded clause (lied) is encountered, the NP the president can either be interpreted as the direct object of the sentence, or as the subject of an embedded clause.Footnote1 The former – and initially most probable interpretation (Frazier & Fodor, Citation1978; MacDonald et al., Citation1994) – might cause problems for the listener when the verb of the embedded clause (lied) is encountered. At this point, the initial interpretation of the sentence (that is, that the reporter thought the president spoke the truth) needs to be revised towards the opposite one (that the reporter thought the president was lying). With the use of that (i.e. The reporter believed that the president lied), however, the sentence is unambiguous, and only the latter interpretation is possible.

Production ease

Many studies provide evidence for the view that speakers structure their utterances in ways that reduce production costs (see, e.g. MacDonald, Citation2013 for a review), in particular in the domain of word ordering preferences. Speakers prefer to grammatically encode their utterances so that NP referents that are easily retrievable from memory – and thus are accessible – are ordered before less accessible referents that are harder to retrieve (Bock, Citation1982; Bock & Irwin, Citation1980; Bock & Warren, Citation1985; Levelt & Maassen, Citation1981; MacDonald, Citation2013 and see Jaeger & Norcliffe, Citation2009 for a review). If easily retrievable referents are encoded first, utterance execution can begin early, and there is more time to encode less retrievable referents. The accessibility of an NP can either depend on conceptual properties of the referents, such as animacy, concreteness or imageability (i.e. conceptual accessibility, see Bock & Warren, Citation1985), or on their current cognitive status in the discourse context (i.e. derived or referential accessibility, see Bock & Irwin, Citation1980; Prat-Sala & Branigan, Citation2000). NP referents that have been previously introduced in the discourse and are mentioned throughout are accessible, and referents that are new in the discourse are inaccessible. This cognitive status of NP referents in the discourse model, referred to as givenness, is often reflected in encoding: referents that are discourse-given are encoded by zero marking, bound morphemes, personal pronouns or definite NPs, and referents that are discourse-new are encoded with indefinite NPs (e.g. Ariel, Citation1990; Gundel et al., Citation1993; Gundel & Fretheim, Citation2004). In situations where alternative word orders are grammatically possible, speakers show a preference for ordering animate referents before inanimates (see Bock et al., Citation1992 and McDonald et al., Citation1993 for English; van Nice & Dietrich, Citation2003 for German; Feleki & Branigan, Citation1999 for Greek; Tanaka et al., Citation2005, Citation2011 for Japanese; and Branigan et al., Citation2008 for a review), concrete before abstract (see Bock & Warren, Citation1985 for English) and given before new (see Bock & Irwin, Citation1980 for English; Ferreira & Yoshita, Citation2003 for Japanese; and Prat-Sala & Branigan, Citation2000 for English and Spanish).

There is also some evidence suggesting that speakers grammatically encode their utterances so as to avoid interference between semantically similar information (see MacDonald, Citation2013 for a review). The retrieval of an NP referent may interfere with the retrieval of an upcoming, temporally close NP referent, when those NPs are semantically similar to each other. Utterance planning of coordinated NPs take longer time when those NPs contain semantically similar nouns (e.g. saw and axe), compared to more dissimilar nouns (e.g. saw and cat), indicating that the retrieval of the first noun interferes with the retrieval of the second (Smith & Wheeldon, Citation2004). Such interference seems to affect grammatical encoding (Gennari et al., Citation2012; MacDonald, Citation2013). Gennari et al. (Citation2012) found the agent (e.g. woman) of a transitive event to more frequently be demoted to a by-phrase or to be omitted when it was semantically similar to the patient (e.g. man) in comparison to when it was dissimilar to the patient (e.g. bag). Speakers thus seem to avoid structures with two semantically similar NP referents in close proximity to each other (e.g. The man who the woman is punching) in favour of structures where they are further apart (e.g. The man who was punched by the woman) or where only one of them is overtly expressed (e.g. The man who was punched), thereby avoiding potential similarity-based interference.

Speakers also tend to use grammatical structures that they recently have used or heard, a phenomenon referred to as structural priming (e.g. Bock, Citation1986; Bock et al., Citation1992; Bock & Griffin, Citation2000; Branigan et al., Citation2000; Pickering & Branigan, Citation1998). For example, speakers that have previously heard a passive sentence are more likely to produce a passive themselves. This suggests that there is a tendency for speakers to use grammatical structures that are more activated and therefore easier to retrieve (MacDonald, Citation2013). Structural priming has been suggested to involve re-activation of recently activated grammatical structures (Pickering & Branigan, Citation1998) or the procedures realising those structures (Bock, Citation1986). It has also been suggested to reflect long-term implicit learning of grammatical structures (Bock & Griffin, Citation2000; Chang et al., Citation2006, Citation2012; Reitter et al., Citation2011) or a tendency of interlocutors to coordinate their utterances in order to facilitate communication (Branigan et al., Citation2000; Carbary & Tanenhaus, Citation2011; Jaeger & Snider, Citation2013; Pickering & Garrod, Citation2004; and see Ferreira & Bock, Citation2006 for an overview). Whatever the underlying reasons, structural priming has a facilitatory effect on language production in the sense that it promotes the re-use of easily retrievable structures (see MacDonald, Citation2013).

Communicative success

Evidence for the view that speakers also structure their utterances in order to successfully communicate their message to the listener is more mixed. One way in which a speaker can accommodate the understanding of the listener is to avoid morphosyntactic ambiguities such as the omission of that in the example above. While some studies have found evidence for morphosyntactic ambiguity avoidance, others have not. On the basis of corpus data, Temperley (Citation2003) and Hawkins (Citation2003) showed that that tends to be used more frequently in contexts that otherwise would be ambiguous. Wasow et al. (Citation2011) found that to be more frequently used for relative clauses that are less contextually expected (see also Norcliffe & Jaeger, Citation2016 for similar findings in Yucatec Mayan). However, in a series of spoken sentence production experiments, Ferreira and Dell (Citation2000) did not find ambiguity avoidance to affect the use of that. On the basis of spoken corpus data, Jaeger (Citation2010) found weak evidence for an effect of ambiguity avoidance on that-mentioning, but only when omission would result in long-lasting ambiguities (see also Jaeger, Citation2006, Citation2011). Haywood et al. (Citation2005) found preposition phrase attachment ambiguitiesFootnote2 to be more frequently avoided when such ambiguities could lead to confusion, but Arnold et al. (Citation2004) did not find any evidence for avoidance of prepositional phrase attachment ambiguities.

However, it is still unclear what kind of information speakers and comprehenders are sensitive to in potentially ambiguous contexts. Although individual sentences might be morphosyntactically ambiguous, there is usually other lexical-semantic and contextual information available for the listener. In line with this, Roland et al. (Citation2006) found that the correct interpretation of direct object-relative clause ambiguities (resulting from that-omission) can be predicted by other information types, such as verb bias, constituent length, word frequency and lexical-semantic properties. Further, sentences that are morphosyntactically ambiguous in isolation are often unproblematic to interpret in appropriate discourse contexts (Ferreira, Citation2008; Rahkonen, Citation2006). The ambiguity can often be resolved from information in the discourse context. Indeed, it has been suggested that sentence-level ambiguities are beneficial for communication as long as they can be resolved in context (Piantadosi et al., Citation2012; see Wasow et al., Citation2005 for a discussion and Caplan et al., Citation2020 for arguments against this view). Unambiguous information that is redundant in the discourse might entail higher production costs for the speaker and therefore result in less efficient communication. Thus, the crucial question might not be whether speakers avoid sentences that are morphosyntactically ambiguous in isolation (independent of whether other information types can resolve the ambiguity), but rather whether they balance their use of morphosyntactic information with respect to any type of information that guides interpretation.

Information balance in the encoding of grammatical functions

Support for the view that the use of morphosyntactic cues is balanced with respect to other information comes from studies investigating variations in the encoding of grammatical functions in transitive sentences (see Hörberg, Citation2016 for a review), that is, the grammatical encoding of subjects and direct objects (henceforth referred to as objects). Grammatical functions are encoded by various morphosyntactic cues, such as word order, case marking and agreement. The availability of these cues often interacts with other discourse-pragmatic or lexical-semantic properties, such as givenness or animacy, which themselves can be informative about grammatical functions (for examples, see Hörberg, Citation2016, pp. 13–15). Animacy, for instance, is highly predictive of grammatical functions. Because of role-semantic properties of grammatical functions (see, e.g. Hörberg, Citation2016, pp. 9-10 for a description), subjects are more frequently animate than objects (see Dahl, Citation2000; Dahl & Fraurud, Citation1996; and Hörberg, Citation2018 for Swedish; Kempen & Harbusch, Citation2004 for German; Øvrelid, Citation2004 for Norwegian; and Bouma, Citation2008 for Dutch).Footnote3 Animacy, therefore, serves as a cue to grammatical functions during on-line comprehension (e.g. Hörberg & Jaeger, Citation2021).

Importantly, both corpus-based and sentence recall studies indicate that language producers are sensitive to animacy in their encoding of grammatical functions. Speakers and writers more frequently use overt morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions when those functions cannot be inferred on the basis of animacy. In Korean and Japanese, overt case marking particles can be omitted in colloquial speech (Kurumada & Jaeger, Citation2015; Lee, Citation2006, Citation2007). In corpus studies of spoken Korean, Lee (Citation2006, Citation2007) found overt nominative case marking to be used more frequently on subjects that are inanimate, but overt accusative case marking to occur more frequently on objects that are animate. Similarly, in a sentence recall study, Kurumada and Jaeger (Citation2015) found Japanese speakers to more often use overt object case marking on animate objects than on inanimate objects. Several corpus studies have further shown that the potentially ambiguous object-initial word order is preferred when either the subject is animate or the object is inanimate (see Hörberg, Citation2018 for Swedish; Øvrelid, Citation2004 for Norwegian; Bader & Häussler, Citation2010 for German; Bouma, Citation2008; van Bergen, Citation2009 and Lamers & de Hoop, Citation2014 for Dutch; and Butler et al., Citation2010 for Yucatec Mayan).Footnote4 Transitive sentences in written Swedish have also been found to more frequently contain morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions when both NPs are animate (Hörberg, Citation2018). Taken together, these findings indicate that both speakers and writers are inclined to provide additional morphosyntactic information regarding grammatical functions when those functions cannot be determined on the basis of animacy. That is, they tend to balance their use of morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions (i.e. case marking and word order) with respect to animacy.

However, most of this evidence is correlational, as it is based on corpus data. Although such findings show that there is a statistical relationship between the animacy of NP arguments and their morphosyntactic encoding, they are uninformative as to whether speakers’ morphosyntactic encoding choices are affected by animacy more directly, when other contextual factors are controlled for. As animacy correlates with many other referential properties (e.g. definiteness, givenness and person, see Hörberg, Citation2016) as well as discourse-pragmatic factors (e.g. topicality, see Foley, Citation2011), these statistical patterns might depend on other confounds in the discourse contexts. For example, subjects of object-initial sentences in Swedish more frequently consist of personal pronouns than subjects of subject-initial sentences, a pattern that might depend on information-structural considerations on the discourse-level (see Hörberg, Citation2018 for a discussion). However, since personal pronouns are always animate, this pattern results in a higher proportion of animate subjects in object-initial sentences, thereby affecting the relationship between word order and animacy.

Kurumada and Jaeger (Citation2015) did use an experimental paradigm to show that animacy affects Japanese speakers’ morphological encoding of NPs in a manner that controlled for contextual factors. Participants were asked to verbally recall transitive sentences that only varied with respect to animacy and case marking of the object NP. Sentences were more frequently recalled as containing overt object case marking when the object NP was animate, independent of whether case marking was used in the stimulus sentence. Although these findings provide some support for the notion that animacy affects grammatical encoding choices independently of contextual factors, it is unclear whether they would generalise to more ecologically valid situations (see Norcliffe & Jaeger, Citation2016, p. 175) that do not only involve recall of previously heard material.

Most importantly though, Kurumada & Jaegers’ study does not address whether animacy affects the encoding of grammatical functions in appropriate discourse contexts as well. In natural language, individual sentences most frequently occur in discourse contexts with additional background information about the information status of participants (e.g. givenness) and events (e.g. focus) that is shared by speakers and listeners. Such discourse-pragmatic information affects the encoding choices speakers make (see, e.g. Prat-Sala & Branigan, Citation2000), and can be utilised by listeners during interpretation (e.g. Kristensen, Engberg-Pedersen, & Poulsen, Citation2014; Kristensen, Engberg-Pedersen, & Wallentin, Citation2014). The discourse thus provides additional cues to grammatical functions that might render the need for additional information (such as overt case marking) redundant. Although transitive sentences might be ambiguous with respect to grammatical functions in isolation, they have been claimed to be unproblematic to interpret in its discourse context (see Rahkonen, Citation2006 for an example from Swedish). However, language comprehension is often assumed to involve interpretation at different stages. Accordingly, the interpretation of local structure on the sentence level – where grammatical function assignment occurs – temporarily precedes the interpretation of global structure on the discourse level (e.g. Bornkessel & Schlesewsky, Citation2006; Friederici, Citation2011 and see Hörberg, Citation2018 for a discussion). Sentence-level cues to grammatical functions might therefore be required to facilitate local structure building even when the discourse context provides additional cues to grammatical functions that can be utilised during the final stage of interpretation. A crucial question is thus whether the encoding of grammatical functions is affected by animacy also when such discourse-level cues are available. This is the question we investigate here.

The present study

In the present pre-registered study (see https://osf.io/jr48z), we investigate how the encoding of grammatical functions in transitive sentences in Swedish is affected by animacy, in particular with respect to word order. This is done in a picture-description task with syntactic priming, where participants freely describe transitive events. Importantly, these events occur in discourse contexts in which the information status of the NP referents is constrained. These contexts should affect the grammatical encoding of the participants’ descriptions, and facilitate interpretation for a potential listener. In the following, we describe the structure of the target transitive sentences. We then describe the information-structural properties that affect their word order, and the contexts in which they occur, and finally summarise our predictions.

Transitive sentences in Swedish

In Swedish transitive sentences, subjects and objects are morphologically distinguished for personal pronouns,Footnote5 but lexical NPs lack case marking and are thus ambiguous with respect to their functions. Grammatical functions are instead primarily encoded by word order, with subjects typically preceding objects (e.g. Hörberg, Citation2018). However, for information-structural considerations (described in more detail below), the object is occasionally positioned sentence-initially. In such sentences, the object is directly followed by the finite verb (e.g. Teleman et al., Citation1999 (4): p. 688; but see Josefsson, Citation2012 for exceptions), resulting in object-verb-subject (OVS) word order. Importantly, such sentences may be locally ambiguous with respect to grammatical functions. In (1a) below, the initial NP consists of a noun that lacks case marking and thus is ambiguous with respect to its grammatical function. By default, an initial NP is interpreted as a main clause subject (Hörberg et al., Citation2013). This interpretation cannot be maintained once the post-verbal subject pronoun is encountered, and the sentence needs to be re-interpreted as object-initial. In (1b), on the other hand, the initial NP is an unambiguous, case-marked object pronoun. The sentence is therefore interpreted as object-initial directly.

(1) a. Läraren gillade vi inte.

teacher.the liked 1PL.NOM not.

ʻThe teacher we did not like.ʼ

b. Henne gillade vi inte.

3SG.ACC liked 1PL.NOM not.

ʻHer we did not likeʼ

c. Soppan gillade vi inte.

Soup.the liked 1PL.NOM not.

ʻThe soup we did not likeʼ

However, since animacy serves as a cue to grammatical functions, sentences such as (1c), in which the initial object is inanimate, are less problematic to interpret. In a self-paced reading experiment, Hörberg and Jaeger (Citation2021) found faster reading times of the post-verbal subject in sentences such as (1c), in comparison to sentences such as (1a). The inanimacy of the initial NP provides support for an OVS interpretation at the sentence onset, thereby facilitating comprehension at the post-verbal subject (see Hörberg & Jaeger, Citation2021 for a formal account of how animacy and other cues affect on-line argument interpretation).

In the present study, we ask whether speakers are more likely to produce OVS sentences when the object referent is inanimate (thereby producing sentences such as (1c)), than when it is animate (resulting in sentences such as (1a)), even though those sentences are produced in discourse contexts where OVS word order can be expected. We also investigate whether OVS sentences are used more frequently with additional morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions. This primarily concerns whether the sentence subject consists of a case-marked personal pronoun (such as vi in (1a)–(1c)). However, there are also other syntactic cues to grammatical functions in Swedish that we consider. In SVO sentences, the object NP follows all the verbs, sentential adverbials and verb particles. In OVS sentences, the subject NP instead precedes non-finite verbs, sentential adverbials and verb particles (Teleman et al., Citation1999 (3): pp. 39–40). This is illustrated in (2) and (3), adopted from Rahkonen (Citation2006). In (2a), the initial NP must function as the subject since the final NP follows the main verb. In (2b), it must instead be the object, because the final NP precedes the main verb.

(2) a. Den äldsta av rävarna har lurat jägaren.

the oldest of foxes.the has cheated hunter.the

ʻThe oldest of the foxes has cheated the hunter.ʼ

b. Den äldsta av rävarna har jägaren lurat.

the oldest of foxes.the has hunter.the cheated

ʻThe oldest of the foxes, the hunter has cheated it.ʼ

(3) a. En av gästerna kastade ut värden.

one of customers.the threw out innkeeper.the

ʻOne of the customers threw out the innkeeper.ʼ

b. En av gästerna kastade värden ut.

one of customers.the threw inkeeper.the out

ʻThe innkeeper threw out one of the customers.ʼ

We also ask (in line with our pre-registration) whether speakers are more likely to use these morphosyntactic cues when the object NP is animate. We thus also aim to replicate the finding that these morphosyntactic cues are used more frequently when both NPs are animate (so that animacy cannot be used as a cue to grammatical functions; Hörberg, Citation2018).

Information structure and word order variation in transitive sentences

In typical, SVO sentences in Swedish, the subject NP most frequently refers to the topic and the object NP to new information that is part of or constitutes the focus. Object-initial word order is used to signal deviations from this norm and is first and foremost used when it is the object, rather than the subject, that is topical (Bohnacker, Citation2010; Bohnacker & Rosén, Citation2008, Citation2009; Rahkonen, Citation2006; Teleman et al., Citation1999 (4): p. 432; Teleman & Wieselgren, Citation1988). In line with this, sentence-initial objects tend to more frequently be given than post-verbal objects.Footnote6 However, object fronting can also be used to signal that the object is contrastive (Hörberg, Citation2018). In such cases, the object is positioned sentence-initially in order to emphasise that it stands in opposition with one or several alternatives. In (6), for example, the object NP lastbilen is positioned sentence-initially in order to signal that the toy truck in the event is opposed to the toy bricks in terms of involvement: Whereas the toy truck is being played with, the toy bricks are being ignored.

(6) Lastbilen lekte han med men klossarna struntade han i

Truck.the play 3SG.NOM with but bricks.the ignored 3SG.NOM in

‘He played with the toy truck, but he ignored the bricks’

In the present study, item contrast is used to motivate the use of OVS word order. Participants listen to spoken short stories that are accompanied with cartooned pictures. Their task is to freely describe the events that are depicted in the final scene of each story. Importantly, these events are contrastive in the sense described above: they involve an opposition in the way the protagonist of the story interacts with two previously introduced objects or antagonists. For example, in the final scene of one story, a little boy is playing with toy bricks while ignoring a toy truck, thereby depicting an event that is likely to be described with a sentence such as (6).

The discourse of each stimulus story sets the stage for such contrastive events. First, the story protagonist is introduced (e.g. a little boy), and the situational context is presented (e.g. the boys’ birthday party). Then, either two antagonists (e.g. two kids attending the party) or two objects (e.g. a toy truck and toy bricks that the boy received as gifts) are introduced. Finally, the contrastive event itself is presented. The discourse preceding the contrastive event thus motivates the use of an object-initial construction. It introduces a discourse topic (the protagonist), a situational context, and two alternatives (two antagonists or two objects). These alternatives are then contrasted against each other with respect to their involvement in the event. This discourse structure should motivate the use of an object-initial construction (such as (6)) and make the object-initial word order more expected for a potential interlocutor.Footnote7 As such, the discourse context provides a cue to grammatical functions on the discourse level which might influence the use of morphosyntactic cues on the sentence level. The question we ask is thus whether speakers balance their use of morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions with respect to animacy, even when this additional discourse-level information is available. The crucial manipulation of the experiment thus concerns the animacy of the affected entities in the contrastive events to be described. As mentioned above, these events either involve two human – and thus animate – antagonists or two inanimate objects.

In order to further motivate the use of object-initial word order, each story also contains an initial contrastive event that is described in the story. Participants are thus exposed to item contrast sentences such as (6). These sentences function as structural primes for the participants’ subsequent descriptions of the probe events. To the best of our knowledge, this type of priming differs from that of earlier studies. Typically, the priming sentences are unrelated to the probes used to elicit production. Here, the primes are instead part of the discourse contexts in which the probes (i.e. the contrastive events to be described) occur. Even though a potential priming effect is not directly relevant for the main research question that we wish to address, we therefore sought to investigate whether this type of priming has an observable effect on participants’ descriptions, and/or whether it interacts with animacy.Footnote8 The priming sentences in the stories therefore occur either with OVS or SVO word order. In line with previous findings, participants should thus more frequently use the word order – OVS or SVO – of the priming sentence at hand (e.g. Bock, Citation1986; Bock et al., Citation1992; Bock & Griffin, Citation2000; Branigan et al., Citation2000; Pickering & Branigan, Citation1998).

The main predictions of the experiment

To summarise, we investigate whether participants’ encoding of grammatical functions in Swedish transitive sentences is affected by animacy even when those sentences are produced in discourse contexts that provide information about grammatical functions. To this end, we perform a picture-description experiment with structural priming. Participants freely describe contrastive events that can be encoded with either a SVO or an OVS word order. Crucially, these events differ with respect to the animacy of the object referent. If participants’ encoding is sensitive to this animacy manipulation, events with inanimate object referents should more frequently be described with OVS word order. If participants’ encoding is sensitive to the availability of cues to grammatical functions more generally, OVS word order should also be used more frequently with other morphosyntactic cues, and such cues should further be used more frequently in sentences with two animate object NPs.

Materials and methods

Participants

A total of 65 native Swedish speakers (39 female) performed the experiment. Participants were recruited via advertisements around Stockholm University, through the on-line recruitment tool Accindi (www.accindi.se), and on social media. Their age had a median of 27 years and ranged from 18 to 68 years. Participants received a gift voucher of a value of approximately 23 USD as reimbursement for their participation. They were informed about the experimental procedure and the precautions taken in order to minimise the risk of the spread of the Covid-19 virus. They were further told that they could stop at any time without giving a reason. They provided written informed consent. Data from three participants whose responses were not in accordance with the instructions was excluded from further analysis.

Stimulus material

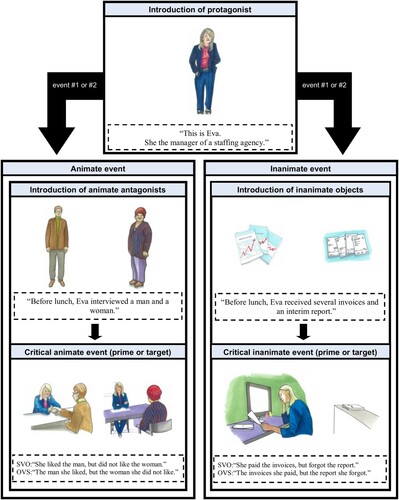

The material consists of spoken short stories that are accompanied with cartooned images. The actual stimuli of the stories are described in detail in the supplementary materials. Here, we present the structure of the stories. The stories consist of scenes, presented one scene at a time,Footnote9 that are divided into three parts (see ).

Figure 1. An illustration of the structure of the stories. First, the story protagonist is presented. Then, an animate or an inanimate event is presented. In these, two animate antagonists (animate event) or two inanimate objects (inanimate event) are introduced, and the protagonist interacts with these antagonists (animate event) or inanimate objects (inanimate event) in a contrastive manner.

Part 1 consists of one scene which introduces the protagonist of the story and presents the situational context. For example, in the story illustrated in , this is done as in (7):

7. Det här är Eva. Hon jobbar som chef på ett bemanningsföretag.

‘This is Eva. She is the manager of a staffing agency.’

8a. Innan lunch/efter lunch intervjuade hon en man och en kvinna.

‘Before lunch/after lunch, she interviewed a man and a woman.’

8b. Innan lunch/efter lunch fick hon flera fakturor och en kvartalsrapport.

‘Before lunch/after lunch, she received several invoices and an interim report.’

9a. Hon gillade mannen, men tyckte inte om kvinnan.

‘She liked the man, but did not like the woman.’

9b. Hon betalade fakturorna, men glömde bort rapporten.

‘She paid the invoices, but forgot the report.’

10a. Mannen gillade hon, men kvinnan tyckte hon inte om.

‘The man she liked, but the woman she did not like.’

10b. Fakturorna betalade hon, men rapporten glömde hon bort.

‘The invoices she paid, but the report she forgot.’

Two sets of 16 full stories with an animate and an inanimate event were constructed.Footnote10 The story pair of each set differ with respect to the pictures being used, the names and the genders of the protagonist and the antagonists, and in some cases with regard to the involvement of the objects in the event (e.g. the protagonist playing with a teddy in one of the stories but with a doll in the other). The verb describing an event was used to describe an event of opposite animacy in another story. Across stories, all verbs thus describe both animate and inanimate events. This ensures that any animacy difference in the use of OVS word order cannot be due to a difference between verbs (i.e. OVS more frequently being used with some verbs than others). In some stories, the exact wordings differed with presentation order (i.e. depending on whether an event was the first or the second event of the story).

Four story versions, corresponding to each of the four conditions, were constructed for each of the stories, resulting in 16 (item) × 2 (set) × 4 (condition) = 128 stories in total. These were divided into eight story lists with two blocks of 16 stories, one block of SVO priming stories and one with OVS priming stories. The priming manipulation was thus conducted across blocks, in line with the finding that syntactic priming is stronger in blocked designs due to a cumulative priming effect (e.g. Hartsuiker & Kolk, Citation1998; Hartsuiker & Westenberg, Citation2000; Jaeger & Snider, Citation2013; Kaschak, Citation2007). The animacy of the probe event (i.e. eight animate and eight inanimate probe events) as well as the story set (i.e. eight stories of set 1 and eight stories of set 2) was evenly distributed across blocks. Story items were evenly distributed across blocks so that each block only contained one of each item. The two occurrences of each item (i.e. from set 1 and set 2) therefore always appeared in separate blocks, and, within each list, differed with respect to animacy and word order. The gender of the protagonists and the antagonists, and in some cases the involvement of the objects, were thus counterbalanced across blocks (e.g. the protagonist of a story item was male in block 1 but female in block 2).

Procedure

Participants filled out an informed consent form and were instructed on how to perform the experiment. They were told that they would listen to stories with visual scenes and that their task was to finish each story by describing the depicted event of the final story scene with one or two sentences. Participants were seated about fifty centimetres from a monitor and thirty centimetres from a microphone (Zoom Handy Recorder, H2). The experiment was conducted on a Windows 10 PC, using PsychoPy software (Peirce et al., Citation2019). Before the experiment started, written instructions were presented and participants performed two practice rounds in order to get familiarised with the experimental procedure.

The experiment was conducted in two blocks with either SVO or OVS priming sentences. Block order was counterbalanced across participants. Each block was preceded by a screen informing that the next block was about to begin. At the beginning of each block, a story with the same structure as the stimuli stories was presented in writing. These stories contained two transitive sentences with either SVO (similar to 9a and 9b) or OVS (similar to 10a and 10b) word order. Under the pretence of being used for sound calibration, participants read these stories aloud while being recorded. The purpose of this was to further promote OVS or SVO word order priming in the subsequent free description task. In this reading task, participants started and stopped the recording by pressing a button on a response pad (Cedrus RB740).

The 16 trials of the block at hand were then presented. Each trial started with a screen that informed about the sequential number of the story that was about to begin (e.g. Press any key to start story number 3). The story was started by a button press. Each story was presented one scene at a time (with a total of five scenes, see ). Both the picture and the verbal narration of the story part (e.g. the introduction of the protagonist or the antagonists) was presented in all but the final scene (see Supplementary Materials for a more detailed description of the presentation timing and positioning of the pictures). In the final scene – depicting the probe event to be described – the picture was instead presented with the probe utterance Vad hände? (“What happened?”). Two seconds after this presentation, a red question mark appeared in the centre of the screen on top of the picture. At this point, participants could start recording their descriptions, either by starting to talk, or by pushing any response pad button. During recording, a red circle, blinking in one-second intervals, was displayed in the centre of the screen on top of the picture, showing that the microphone was recording. Participants stopped the recording – and thereby ending the trial – by pressing any response pad button.

Data pre-processing

The recordings were orthographically transcribed and the resulting transcriptions were divided into single clauses (see Supplementary Materials for a description of clause categorisation). On average, probe scenes were described with 2 clauses but the length of the descriptions varied considerably across participants. For example, one scene was described with 15 clauses by one participant. We categorised each clause as SVO, OVS, passive or “other”. In order to retain as many clauses as possible in the final data set, we used a fairly liberal categorisation scheme, described in the Supplementary Materials. For instance, in contrast to Hörberg (Citation2016, Citation2018), clauses with prepositional objects (e.g. Han började leka med flickan, “He started to play with the girl”), predicative constructions (e.g. Han var dålig på pussel, “He was bad at jigsaw puzzles”), and clauses with lexicalised predicates (e.g. Han tog tag i mannen, “He grabbed hold of the man”) were included. Clauses categorised as passives or “other” were excluded from further analysis, resulting in the exclusion of 49.64% of all clauses.

We annotated each clause for the following information: animacy of the direct object, type of subject and object pronoun (if any), verb particle, auxiliary verb(s) and sentence adverb. Clauses were also classified with respect to their “relevance” – whether they were produced in accordance with the instructions of the experimental task. The clauses should describe some aspect of the event depicted in the probe event and be part of the story discourse context. In some cases, participants simply repeated earlier parts of the stories. In other cases, they provided continuations of the stories that were unrelated to the depicted probe event. In a minority of cases, participants commented on the experiment or got interrupted due to a technical issue with the recording. All non-relevant transitive clauses were excluded from further analysis, resulting in the exclusion of 5.07% of all SVO- and OVS-clauses. All data from three participants who produced more than 50% irrelevant clauses was excluded. In total 44.64% of all clauses were included in the final data set.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in the statistical software R (R Core Team, Citation2020).Footnote11 These analyses involved Bayesian logistic mixed-effect models that were fitted with the R package Rstanarm (Goodrich et al., Citation2020).

Our first set of models predicted the probability of a transitive sentence to be produced with OVS word order (as opposed to SVO word order) in terms of log odds. Following the pre-registration protocol, we fitted one model investigating the influence of the animacy of the event on the choice of OVS vs. SVO word order. We also fitted three models that investigated whether word order choice is related to (1) the animacy of the object NP, (2) the case marking of the subject NP and (3) the other syntactic cues to grammatical functions: a verb particle, an auxiliary verb and/or an adverb. The last of these models thus contained a predictor that codes for whether the sentence contains any of these cues. All of these models also tested whether OVS vs. SVO word order choice is influenced by word order priming. As such, the models contained a fixed effect for the cue at hand; either animacy (sum-coded: .5 = animate vs. −.5 = inanimate), subject case (sum-coded: .5 = marked vs. −.5 = unmarked), or morphosyntactic marking (sum-coded: .5 = marked vs. −.5 = unmarked), a fixed effect for prime (sum-coded: .5 = SVO vs. -.5 = OVS), and for the cue × prime interaction effect. All models also included the maximal by-participant and by-story random effects structures, i.e. by-participant and by-story random slopes for all fixed effects.

In line with the pre-registration protocol, we also fitted two models that investigate whether the animacy of the object influences the use of morphosyntactic markers. We used one model that predicts whether the sentence contains a case-marked subject pronoun, and one that predicts whether the sentence contains any other syntactic marker (i.e. an auxiliary, a verb particle or a sentential adverb). In addition to object animacy, these models also included a predictor for word order, and an animacy × word order interaction term, thereby testing whether a potential effect of animacy is mediated by word order. As such, the models contained a fixed effect for animacy (sum-coded: .5 = animate vs. −5: inanimate), word order (sum-coded: .5 = SVO vs. −.5 = OVS) and for their interaction. Because of convergence issues likely due to the few numbers of OVS sentences, these models did not include any random slopes for word order.Footnote12 They contained by-participant and by-story random intercepts as well as by-participant and by-story random slopes for animacy.

In line with recommendations (e.g. Gelman, Citation2006; Gelman et al., Citation2008; Stan Development Team, Citation2017), standard, weakly regularising priors were used in the models. For fixed effect predictors, a 3 degree of freedom Student t prior with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 2.5 units was used (following Gelman et al., Citation2008). For random effect standard deviations, a Cauchy prior with location 0 and scale 2 was used, and for random effect correlations, a LKJ-Correlation prior with the shape parameter set to 1 was employed (Lewandowski et al., Citation2009). For the intercepts in the word order models, we used a normal prior with a mean of −3.04 and standard deviation of 2.5. This prior reflects the well-established baseline probability for OVS word order, observed in earlier studies (e.g. Hörberg, Citation2016, Citation2018). The intercepts in the morphosyntactic marking models instead had a normal prior with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 2.5. All models were fitted using 12 chains with 1000 warmup-samples and 5000 post-warmup samples per chain, resulting in 60,000 posterior samples for each analysis.

Inferences about effects (e.g. an animacy effect) are done on the basis of a (lack of) overlap between fixed effects credibility intervals (CIs) and the region of practical equivalence (ROPE; see e.g. Kruschke, Citation2014, pp. 336–340). A CI consisting of the 89% highest density interval (HDI) that does not overlap with the ROPE is considered as evidence for an effect. In line with the pre-registration, approximately a ±0.1 standardised ROPE interval was used. More specifically, the ±0.095 ROPE interval was used since it corresponds to an odds ratio interval of around 0.91–1.10. In other words, an effect that is equal to or smaller than a 10% change in the odds of the predicted morphosyntactic feature at hand (i.e. OVS word order, subject pronoun, or syntactic marker) is considered a null effect. We also report the posterior probability (P in ROPE) of a fixed effect being below (for negative effects) or above (for positive effects) the ROPE interval. This is similar to the frequentist, one-sided p-value. It represents the probability that the effect at hand is greater than a null effect – an effect equal to or below a 10% change in the odds of the morphosyntactic feature at hand.

Results

Word order choice

In the analysed transitive sentences, 1618 have SVO word order and 193 have OVS word order. Thus, the OVS word order sentences make up only 10.66% of all transitive sentences. Although this percentage of OVS sentences is somewhat lower than expected, it is substantially higher than the overall percentages observed in earlier, corpus-based studies (Bohnacker & Rosén, Citation2008; Hörberg, Citation2016, Citation2018; Jörgensen, Citation1976; Westman, Citation1974), indicating that participants indeed were sensitive to the contrastive contexts.

shows the number of occurrences as well as the percentages of all OVS and SVO sentences that contain an inanimate object, a case-marked subject pronoun, or any or all of the syntactic cues (a verb particle, auxiliary verb or an adverb). Strikingly, all of these cues occur more frequently in OVS than in SVO sentences, mirroring the results of Hörberg (Citation2018).

Table 1. Number of occurrences and percentages of OVS (total N: 194) and SVO (total N: 1616) sentences with an inanimate object, a case-marked subject, a verb particle, an auxiliary verb, an adverb or any syntactic cue to grammatical functions. CIlower and CIupper are the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals, calculated on the basis of normal approximation.

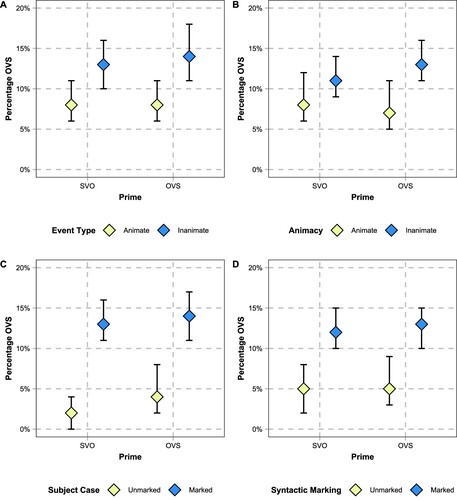

and (Panel a) shows the distribution of produced OVS sentences as a function of probe event (Animate event vs. Inanimate event) and prime type (OVS vs. SVO). OVS word order is produced more frequently in descriptions of inanimate events. There is, however, hardly any effect of prime type. OVS word order is used more or less equally frequently in the descriptions of both SVO and OVS prime stories.

Figure 2. Percentage of OVS sentences differentiated by Prime and (a) Event type, (b) Animacy of the direct object, (c) Subject case marking and (d) Syntactic marking. Error bars illustrate 95% confidence intervals, calculated on the basis of normal approximation.

Table 2. Number of occurrences and percentages of OVS sentences as a function of prime (SVO or OVS) and event type (Animate vs. Inanimate). CIlower and CIupper are the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals, calculated on the basis of normal approximation.

and (Panels b–d) show the percentage of OVS sentences, differentiated on the basis of prime type (OVS vs. SVO), object animacy, subject case marking, and all of the syntactic cues combined. OVS word order co-occur more frequently with any of these cues, independent of prime type.

Table 3. Number of occurrences and percentages of OVS sentences as a function of prime (SVO or OVS) and cue availability of object animacy, subject case marking and syntactic marking. CIlower and CIupper are the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals, calculated on the basis of normal approximation.

In order to determine whether the choice between SVO or OVS word order is influenced by the probe event and the prime type, the data was analysed with Bayesian logistic mixed effects regression.

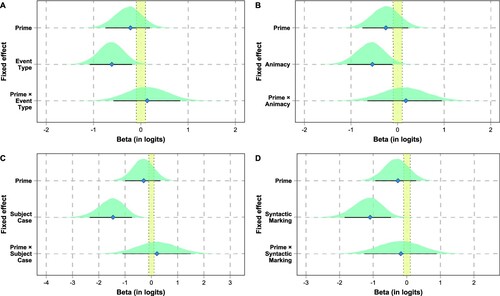

Additional models were also run to investigate whether there is a relationship between the availability of each of the three different cues (animacy, subject case and a syntactic marker) and word order, and whether such a relationship is mediated by prime type. As explained above, we ran one model that investigates the effect of probe event type, prime type and their interaction on word order choice, as well as three separate models concerned with the relationships between the three different cue types and word order. The results of these models are shown in and illustrated in .

Figure 3. Fixed effect estimates in the Bayesian models. Points show maximum a-posteriori estimates, lines show 89% HDIs and density plots illustrate posterior distributions. Shaded areas around zero illustrate the ROPE (±0.095). (a) Event type (Inanimate vs. Animate event); (b) Object animacy (Animate vs. Inanimate); (c) Subject case marking (Marked vs. Unmarked); (d) Syntactic marking (Marked vs. Unmarked).

Table 4. Results of the Bayesian logistic mixed effects models of word order choice. βMAP is the maximum a posteriori probability estimate of the β parameter at hand. Credibility intervals (CIs) are the lower and the upper limits of the 89% highest probability density intervals of the β:s. Shaded areas mark fixed effects whose CIs do not overlap with the ROPE (±0.095).

These analyses show strong support for the hypothesis that the probe event type influences the choice between SVO and OVS word order. They also show that all three cue types are related to word order. None of the CIs of the Event type, Animacy, Subject case and Syntactic marking fixed effects overlap with the ROPE, and the probability of any of the effects to overlap with the ROPE is below 0.05. In other words, there is more than a 95% chance that participants are at least 10% more likely to produce an OVS sentence (over SVO) when the probe event is inanimate. There is also more than a 95% chance that a transitive sentence is at least 10% more likely to have OVS word order if it contains an inanimate object, a case-marked subject pronoun or any of the syntactic cues.

Participants are 1.81Footnote13 times more likely to use OVS word order when describing an inanimate event in comparison to when describing an animate event. A transitive clause is also 1.71 times more likely to have OVS word order when the object is inanimate compared to when it is animate, 4.31 times more likely when the subject is a case-marked pronoun, and 2.97 times more likely when it contains a verb particle, an auxiliary or an adverb.

Other morphosyntactic marking

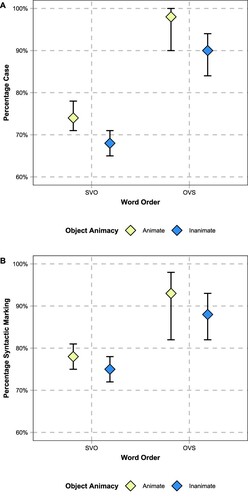

Out of the selected sentences, 72.4% contains a case-marked subject pronoun and 77.6% some kind of syntactic marker. and shows the distribution of these morphosyntactic cues as differentiated by animacy and word order.

Figure 4. Percentage of morphosyntactic marking differentiated by word order and animacy of the object. Panel (a) Subject case marking. Panel (b) Syntactic marking (auxiliary verb, verb particle or sentential adverbial). Error bars illustrate 95% confidence intervals, calculated on the basis of normal approximation.

Table 5. Number of occurrences and percentages of morphosyntactic marking (case marking and other syntactic marking) as a function of word order (SVO or OVS) and animacy (Animate vs. Inanimate). CIlower and CIupper are the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence intervals, calculated on the basis of normal approximation.

As already shown in , all of these morphosyntactic markers are more frequent in OVS sentences than in SVO sentences, suggesting that OVS word order is preferred when other morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions are available. In addition, both subject case marking and syntactic marking occur somewhat more frequently in sentences with animate objects, in comparison to sentences with inanimate objects.

In order to determine whether the choice of morphosyntactic marking is influenced by object animacy – possibly in interaction with word order – two additional Bayesian logistic mixed effects models were fitted. As explained above, we fitted one model that investigates the effect of word order, animacy and their interaction on subject case marking, and one that investigates the effects of these properties on syntactic marking. The results of these models are shown in .

Table 6. Results of the Bayesian logistic mixed effects models of the use of morphosyntactic marking. βMAP is the maximum a posteriori probability estimate of the β parameter at hand. Credibility intervals (CIs) are the lower and the upper limits of the 89% highest probability density intervals of the β:s. Shaded areas mark fixed effects whose CIs do not overlap with the ROPE (±0.095).

This analysis confirms the finding that the use of morphosyntactic cues is related to word order. In both models, the CIs for the word order effects do not overlap with the ROPE, and the probability for these effects to overlap with the ROPE is below 0.05. Speakers are thus more likely to use morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions in OVS sentences than in SVO sentences. The analyses also support that speakers are more likely to use a case-marked pronoun when the object NP is animate than when it is inanimate. In the Subject case marking model, the CI for the animacy effect does not overlap with the ROPE and the probability for this effect to overlap with the ROPE is lower than 0.05. According to the model, speakers are roughly 2.2 times more likely to use a case-marked subject pronoun when the object NP is animate. There is no support for an animacy effect on syntactic marking, however.

Discussion

Grammatical encoding choices have been suggested to be driven by communicative efficiency – an optimal balance between production ease and communicative success. Evidence for this view comes from studies investigating the grammatical encoding of grammatical functions. Language producers more frequently use overt morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions when those functions cannot be inferred on the basis of animacy (e.g. Hörberg, Citation2018; Kurumada & Jaeger, Citation2015; Lee, Citation2006, Citation2007), indicating that they balance their use of cues to grammatical functions in a communicatively efficient manner. The evidence of these studies has, however, either been correlational, or based on studies with low ecological validity. Most importantly though, additional cues to grammatical functions in the discourse context have not been taken into account. Information about grammatical functions on the discourse level might render the need for information on the sentence-level redundant (see Rahkonen, Citation2006 for an example from Swedish). On the other hand, sentence-level cues might still be required to facilitate initial stages of language comprehension, which have been suggested to only involve interpretation of local sentence structure and thus to be independent of information in the discourse context (e.g. Bornkessel & Schlesewsky, Citation2006; Friederici, Citation2011 and see Hörberg, Citation2018 for a discussion). Using a picture-description task with structural priming, we thus investigated whether Swedish speakers’ encoding of grammatical functions is affected by animacy also when additional information about grammatical functions is available in the discourse.

We focused on the encoding of grammatical functions in Swedish transitive sentences, with respect to word order, subject case marking and other syntactic markers. The default word order of such sentences is SVO, but OVS can also be used in order to signal that the object is contrastive (e.g. Hörberg, Citation2018). Outside appropriate contexts, such sentences can be ambiguous with respect to grammatical functions when other semantic or morphosyntactic cues are unavailable. However, contexts that licence their use – such as item contrast contexts (Wälchli, Citationunder review) – provide an additional cue to grammatical functions, possibly rendering the need for other morphosyntactic cues redundant (e.g. Rahkonen, Citation2006). The probe events to be described in the study occurred in such licensing contexts: they involved an opposition in the way the protagonist interacts with one of two antagonists or objects. Crucially, these events differed with respect to the animacy of the object referent. We investigated if this animacy difference affects speakers’ choice between OVS and SVO word order although the sentence is produced in a contrastive context. We also investigated whether animacy is related to other morphosyntactic cues such as subject case marking.

Animacy influences on the morphosyntactic encoding of grammatical functions

The results provide clear evidence for an animacy effect on speakers’ choice of SVO versus OVS word order. Speakers more frequently used OVS word order in their descriptions of inanimate events, where the object referents are inanimate, in comparison to their descriptions of animate events, where the object referents are animate. Word order choice was thus influenced by the animacy of the object referent. OVS word order was also more frequently used when the object NP in the sentence was inanimate, compared to when it was animate (independent of whether the sentence described an animate or an inanimate event), thereby also showing a statistical relationship between the animacy of the object NP and word order. These findings provide strong support for the hypothesis that speakers’ choice of OVS versus SVO word order in Swedish is influenced by animacy, even when the sentence is produced in a discourse context where OVS can be expected.

The results also show that OVS is more frequent than SVO in sentences with other morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions, such as a case-marked subject NP or another syntactic marker such as a verb particle, an auxiliary, or an adverb. These findings support the hypothesis that Swedish speakers’ choice between OVS and SVO is influenced by the availability of other cues to grammatical functions – semantic as well as morphosyntactic – even when the sentence is produced in a discourse context where OVS can be expected.

Importantly, these word order patterns cannot be explained on the basis of accessibility. If speakers’ word order choices were sensitive to NP accessibility only, OVS would more frequently be used with animate object referents, since animate NPs are more accessible than inanimate NPs. The same reasoning holds for case marking: since case marking only is used on personal pronouns – which are highly accessible – OVS should be less frequently used with case-marked subject NPs than with other, less accessible subject NPs. The observed patterns cannot be explained in terms of avoidance of similarity-based interference either. Interference between the subject and object NPs should be higher when the object referent is animate, in comparison to when it is inanimate. In such cases, both NP arguments are animate and therefore more similar to each other. The retrieval of the first NP might therefore interfere more with the retrieval of the second. Although there is no reason to assume that such interference would affect the relative ordering of the arguments per se, it could affect their relative distance so that they are further apart in sentences with animate objects. However, we find no evidence for such an effect. The distance between the NP arguments (in terms of the average number of intervening words) is the same in sentences with animate objects (1.88 words) as in sentences with inanimate objects (1.89 words), as evidenced by a paired samples t-test, t(1809) = −0.32, p = .749. Thus speakers’ word order choices do not seem to be influenced by a motivation to avoid similarity-based interference either. Instead, speakers seem to be sensitive to the availability of other cues to grammatical functions: OVS word order is used more frequently when grammatical functions instead can be determined on the basis of animacy or case marking. Speakers’ morphosyntactic encoding choices thus seem to be influenced by a motivation to be informative enough for the listener.

Our findings corroborate those of Hörberg (Citation2018), who found OVS word order to occur more frequently in sentences with inanimate direct objects or other morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions, in comparison to both SVO sentences and passives. However, whereas Hörberg (Citation2018) only found a statistical relationship between word order and these cues to grammatical functions using corpus data, the present study shows that the choice of word order is affected by the animacy of the object referent more directly. As such, our findings provide further support for the notion that language producers actively avoid potentially ambiguous OVS sentences when those sentences will contain two animate NP arguments.

The results also show that sentences are more likely to contain a case-marked subject pronoun when the direct object is animate, compared to when it is inanimate, independent of the sentence word order. Animacy was not found to be related to other syntactic cues, however. These findings parallel those of Lee (Citation2006, Citation2007) and Kurumada and Jaeger (Citation2015), who also found a relationship between overt case marking and animacy in spoken Korean and spoken Japanese. Importantly, this indicates that it is not only word order choice that is affected by animacy, but also the morphological encoding of the subject NP. It suggests that speakers prefer to encode the subject NP in a way that is informative about its grammatical function when the object NP is animate and therefore more likely to be misinterpreted as the subject. Our findings are also in line with those of Rahkonen (Citation2006), who found case-marked subjects to more frequently be used in OVS sentences with two animate NP arguments (compared to sentences with one animate NP argument), and to more frequently occur in OVS sentences than in SVO sentences more generally. Rahkonen (Citation2006) did not, however, interpret these findings as being driven by communicative success. He argued that potential grammatical function ambiguities most likely are unproblematic in natural discourse contexts, and that there therefore is no need for the speaker to tailor her utterance to avoid such ambiguities. However, sentence-level cues to grammatical functions might still be required in order to facilitate interpretation of local sentence structure, which, on many accounts temporally precedes interpretation of global structure on the discourse level (e.g. Bornkessel & Schlesewsky, Citation2006; Friederici, Citation2011 and see Hörberg, Citation2018 for a discussion).

Our findings provide evidence for this account and the main hypothesis of this study: that speakers balance their use of sentence-level cues to grammatical functions even when there is additional information regarding those functions on the discourse level. If this discourse-level information had rendered the availability of additional sentence-level cues obsolete, the observed pattern of the results would not have been expected. Speakers’ word order choice would have been unaffected by animacy and the availability of morphosyntactic cues, and subject case marking would have been unrelated to animacy, because there would be no need for the speaker to balance their use of sentence-level cues. Our findings thus support the notion that grammatical encoding is driven by communicative efficiency. That is, that speakers encoding choices are influenced not only by the goal to reduce production costs, but also by the goal to successfully communicate the message by providing enough information to the listener.

An underlying assumption of this hypothesis is that speakers adapt their productions as to accommodate the understanding of a physical interlocutor. In our study, however, there was no interlocutor available. In line with previous studies (e.g. Kurumada & Jaeger, Citation2015), we thus make the assumption that speakers’ choices are automatic and implicit, and that they are driven by communicative success even in the absence of other interlocutors. It would have been possible to include an interlocutor, such as a confederate, in the experimental setup. However, given the observed patterns of results, there is no reason to assume that this would be required. A possible venue for future research would be to further explore whether our findings would be influenced by the availability of a physical interlocutor.

OVS and SVO word order priming

In order to further motivate the use of OVS word order, each story contained an initial contrastive event that was described with a transitive sentence that functioned as a prime for the subsequent description of the probe event. As this priming is part of the discourse contexts in which the probe events occur, it differs from that of earlier studies. We thus sought to investigate whether we could observe a priming effect, and therefore included both OVS and SVO priming sentences in the experiment. Somewhat surprisingly, however, participants’ choice of word order was unaffected by prime type.

The lack of a priming effect is possibly due to the difference in the implementation of structural priming in our experiment as compared to that of earlier experimental studies. In previous studies, prime sentences were either pragmatically unrelated to the probe stimuli, or not part of a coherent discourse structure. In most studies, participants were exposed to written or spoken prime sentences and then either freely described pictures or videos (e.g. Bock, Citation1986; Bock et al., Citation1992, Citation2007; Bock & Griffin, Citation2000; Branigan et al., Citation2000, Citation2007; Bunger et al., Citation2013; Jaeger & Snider, Citation2013; Song & Lai, Citation2021; Vernice et al., Citation2012), or completed sentence fragments (Branigan et al., Citation2006; Hartsuiker & Westenberg, Citation2000; Kantola & van Gompel, Citation2011; Kaschak, Citation2007; Kaschak et al., Citation2006; Pickering & Branigan, Citation1998; van Gompel et al., Citation2012) that were unrelated to the events described in the prime sentences. Some studies have investigated priming in dialogue tasks, where each trial consists of one of the dialogue partners orally instructing the other on some task, with priming being conducted across trials (e.g. Branigan et al., Citation2000; Carbary et al., Citation2010; Carbary & Tanenhaus, Citation2011). These procedures are highly different from the type of priming employed here, where the prime sentence is part of the story that the participants are to complete themselves. This could suggest that structural priming is limited to situations in which the prime and the probe occur outside of a coherent context, and thus are pragmatically unrelated. However, evidence for structural priming also comes from corpus studies. Here, the “prime” and the “probe” sentences occur together in coherent discourse contexts (see, e.g. Bresnan et al., Citation2007; Gries, Citation2005; Jaeger & Snider, Citation2013) where they likely are pragmatically related to each other.

Similar to our findings, Song and Lai (Citation2021) also did not find a priming effect on object-initial, OSV sentences in Cantonese. They speculated that this null finding might stem from OSV sentences being more costly to produce than canonical SVO sentences outside of appropriate discourse contexts. In the present study, however, the target sentences were produced in appropriate contexts that should facilitate their production. The lack of an OVS priming effect in our study is therefore unlikely to stem from higher production costs of OVS sentences.

Another possible explanation for our null finding is the lack of a physical interlocutor in our experiment. If structural priming serves to facilitate communication by means of coordination between interlocutors (Branigan et al., Citation2000; Carbary et al., Citation2010; Carbary & Tanenhaus, Citation2011; Jaeger & Snider, Citation2013; Pickering & Garrod, Citation2004), priming effects should be stronger or only be observed when the probe utterance is directed towards a recipient, such as a dialogue partner. In line with this, Carbary et al. (Citation2010) found structural priming to only occur when the prime was produced by an interlocutor (rather than being recorded). However, Schoot et al. (Citation2014) did not find an interlocutor effect on priming, and an extensive meta-analysis also failed to find evidence for such effect (Mahowald et al., Citation2016). In sum, further research is needed in order to address why no priming effect was observed in the present study.

Conclusions

In the present study, we have shown that speakers’ morphosyntactic encoding of grammatical functions in transitive sentences in Swedish is influenced by animacy, even when the target sentence at hand is produced in discourse contexts that license the use of OVS word order, and the discourse thus provides an additional cue to grammatical functions. Speakers more frequently describe a transitive event with OVS word order when the object NP referent of that event is inanimate, in comparison to when it is animate. OVS word order is also more frequent in sentences where other morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions are available, and subject case marking occurs more frequently in sentences with an animate object NP, as compared to sentences with an inanimate object NP. Speakers thus balance their use of morphosyntactic cues to grammatical functions with respect to the availability of other sentence-level cues, even when there is additional information regarding those functions on the discourse level. These findings provide support for the hypothesis that grammatical encoding is influenced by communicative efficiency – a balance between the goal to minimise production costs, and the goal of successful communication.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (744 KB)Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this work were presented at Discourse Expectations: Theoretical, Experimental, and Computational perspectives (DETEC) 2019, Leibniz-Centre General Linguistics (ZAS), Berlin, Germany and at Architectures and Mechanisms for Language Processing (AMLaP) 2020, the University of Potsdam, Potsdam, Germany. The authors are particularly grateful to Anna Eriksson and Tove Krabo for their great work with the stimulus materials. The authors also want to thank Caroline Arvidsson, Christoffer Forbes Schieche and Mar Santamaria for their help with sentence annotation. The authors also thank Östen Dahl, Florian Jaeger, an anonymous reviewer and the associate editor Dr Stefan Frank for insightful comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the open science framework (OSF) at http://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/DKT85.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In spoken language, there are subtle prosodic cues that differentiate these interpretations, however.

2 In sentences such as Put the fruit in the basket on the blender in which the prepositional phrase in the basket initially can be interpreted as the goal of the action rather than as an attribute of the fruit.

3 In a corpus of spoken Swedish, for example, Dahl (Citation2000) found that 93.2% of the subjects but only 9.9% of the objects in transitive sentences were animate.

4 Although we remain agnostic regarding the processes that underlie grammatical encoding, we note that functional processing, involving lexical selection and grammatical function assignment, often is assumed to precede positional processing, involving the construction of the syntactic structure of the utterance (e.g. Bock & Levelt, Citation1994). Word order choice is thus influenced by lexical-semantic and functional properties of NPs.

5 The subject form of the third-person pronoun is used both for subjects and objects in some Swedish dialects and in colloquial Swedish more generally.

6 For example, in a corpus of written texts, Hörberg (Citation2018) found that 63.1% of all sentence-initial objects were given, in comparison to 31.3% of all post-verbal objects.

7 For example, in terms of increasing the baseline probability for the object-initial word order, see Hörberg and Jaeger (Citation2021).

8 Initial power analyses did not show a substantial difference in power between a design with both an animacy and a prime manipulation, and one with only an animacy manipulation. See https://osf.io/dkt85/.

9 Video recordings of two of the stories can be found at the OSF site (https://osf.io/dkt85/).

10 The full list of sentences can be found at the OSF site (https://osf.io/dkt85/).

11 Analysis scripts are available at the OSF site (https://osf.io/dkt85/).

12 For example, 16 participants did not produce any OVS sentences at all.

13 Calculated as 1/(exp(βMAP)) – i.e. the reciprocal of βMAP expressed on the odds scale.

References

- Ariel, M. (1990). Accessing noun-phrase antecedents. Routledge.

- Arnold, J. E., Wasow, T., Asudeh, A., & Alrenga, P. (2004). Avoiding attachment ambiguities: The role of word ordering. Journal of Memory and Language, 51(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2004.03.006

- Bader, M., & Häussler, J. (2010). Word order in German: A corpus study. Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue internationale De Linguistique Generale, 120(3), 717–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2009.05.007

- Bock, J. K. (1982). Toward a cognitive psychology of syntax: Information processing contributions to sentence formulation. Psychological Review, 89(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.89.1.1

- Bock, J. K. (1986). Syntactic persistence in language production. Cognitive Psychology, 18(3), 355–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(86)90004-6

- Bock, J. K., Dell, G., Chang, F., & Onishi, K. (2007). Persistent structural priming from language comprehension to language production. Cognition, 104(3), 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2006.07.003

- Bock, J. K., & Griffin, Z. M. (2000). The persistence of structural priming: Transient activation or implicit learning? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 129(2), 177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.129.2.177

- Bock, J. K., & Irwin, D. E. (1980). Syntactic effects of information availability in sentence production. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19(4), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(80)90321-7

- Bock, J. K., & Levelt, W. (1994). Language production: Grammatical encoding. In M. A. Gernsbacher (Ed.), Handbook of psycholinguistics (pp. 945–984). Academic Press.

- Bock, J. K., Loebell, H., & Morey, R. (1992). From conceptual roles to structural relations: Bridging the syntactic cleft. Psychological Review, 99(1), 150–171. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.99.1.150

- Bock, J. K., & Warren, R. K. (1985). Conceptual accessibility and syntactic structure in sentence formation. Cognition, 21(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0277(85)90023-X

- Bohnacker, U. (2010). The clause-initial position in L2 Swedish declaratives: Word order variation and discourse pragmatics. Nordic Journal of Linguistics, 33(02), 105–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/S033258651000017X