Abstract

The aim of this normative study was to verify recognition and name agreement of 70 black and white line pictures on a large Czech population sample using an electronic form. The set of pictures was selected based on previous research showing preliminary evidence of high name agreement with one word only. The pictures were arrayed into an electronic form that was distributed via the internet and filled in by 6,055 participants across the whole country. The group for final evaluation comprised of 5,290 respondents (age range 11–90 years, average ± SD: 53 ± 15 years, 77% of women, years of completed education: range 8–28 years, 15 ± 3 years) from all regions. The average name agreement for all pictures was 98%. Name agreement in the majority of pictures was not influenced by gender, age, and education. The most useful 14 pictures are entirely independent of all sociodemographic factors and include table, scissors, bell, ski, crown, chimney, glasses, steering wheel, heart, chain, ladder, horseshoe, bone, and alarm clock. The presented set of pictures named by one word only can be used for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. The pictures and the electronic form are freely available for replication in other languages at our website www.abadeco.cz.

Introduction

Pictures are a popular tool for cognitive testing, memory training, and speech therapy. Picture naming is a useful task in which the patient is required to identify and correctly name a series of pictured objects. It simultaneously explores several cognitive functions. They involve semantic long-term memory and visuo-semantic properties such as translation of a visual stimulus into a conceptual representation, the retrieval of the name of the picture and lexical production (Dell et al., Citation1997; Ghasisin et al., Citation2015). All these processes can be simply summarized and assessed as the name agreement in clinical practice and research. Name agreement indicates the extent to which the subjects use the same word for a given picture (Ghasisin et al., Citation2015). Naming processing may be altered in patients with different brain disorders, e.g., with Alzheimer disease (Moayedfar et al., Citation2019).

An assessment and interpretation are quite problematic if a picture provokes several ambiguous names. In contrast, standardized pictures with consistent naming can be useful in search of cognitive or linguistic deficits. Therefore it is important to identify a set of pictures that are named easily and correctly using one uniform term by many normal individuals from the general population. The correct naming of a picture depends on the drawing itself (how well it depicts the object), age, education, and other factors.

The picture stimuli should have specific properties, including high name agreement as pictures with low name agreement can be a source of incorrect or ambiguous answers (Bartos et al., Citation2013; Bonin et al., Citation2002; Torrance et al., Citation2018; Vitkovitch & Tyrrell, Citation1995).

The first study that provided complex information on picture stimuli properties including name agreement was the study of Snodgrass and Vanderwart (Citation1980) that validated 260 pictures. The same set of pictures was validated in many other languages including Persian (Ghasisin et al., Citation2015; Bakhtiar et al., Citation2013) Croatian (Rogić et al., Citation2013), Greek (Dimitropoulou et al., Citation2009), Turkish (Raman et al., Citation2014), Spanish (Sanfeliu & Fernandez, Citation1996), Russian (Tsaparina et al., Citation2011) Icelandic (Pind et al., Citation2000), and Chinese (Yoon et al., Citation2004). Other studies validated a set of 400 pictures by Cycowitz et al. (Cycowicz et al., Citation1997). This large set has been validated in Portuguese (Pompéia et al., Citation2001), French (Alario & Ferrand, Citation1999), Arabic (Boukadi et al., Citation2016) and more. Some studies (George & Mathuranath, Citation2007; Torrance et al., Citation2018; Yoon et al., Citation2004) report variance in name agreement of particular pictures in different languages.

We decided to develop own picture set that will have a high name agreement in the Czech language. The set includes 70 line pictures that can be named with one word. The development of the set was described in previous studies (Bartos et al., Citation2013; Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018). The purpose of the study Bartos & Hohinova was to draw and exclude inappropriate pictures, to draw and show pictures, record answers and re-draw pictures several times to have adequately drawn and uniform pictures with consistent naming. The final goal was to compare name agreement between older adults and patients with cognitive disorders. The pictures were named with one word only and had different levels of naming difficulty for patients with cognitive disorders. Both healthy participants and patients with cognitive disorder easily named some pictures. On the other hand, patients with cognitive impairment had more difficulties to name some other pictures which were easily named by healthy people. The sample was limited in the size of about 200 participants due to personal testing and limited to a region of the capital city of Prague, Czech Republic. The main outcome was a set of pictures for further national validation which is described here (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018).

Most of the previous studies used personal testing that allows including only a limited sample of tens or hundreds of participants. The results of such studies may not cover regional or other differences in naming. To eliminate these problems, an electronic way of testing can be used. An electronic form accessible through the internet can be filled in by a large sample of participants across the whole country in a short time and thus detect differences in different dialects or slang.

Czech is a West Slavic language spoken by 10 milion people and is the official language of the Czech Republic. The main variety known as Common Czech is spoken thorough most of the Czech Republic. In the eastern part of the country is Moravian Dialect which is also classified as Czech. Czech has a moderately-sized phoneme inventory, comprising ten monophthongs, three diphthongs, and 25 consonants. Czech distinguishes three genders—masculine, feminine, and neuter. Its word order is flexible since Czech uses the grammatical case to convey word function in a sentence. Czech has 31 graphemes representing thirty sounds and it contains only one digraph: ch. Czech also distinguishes vowel length; long vowels are indicated by an acute accent or, occasionally with ů, a ring. Czech has also the capability to create many words as derivates or diminutives.

In the Czech Republic, several dialects are spoken in different parts of the country. The main dialect groups can be found in Central Moravia, East Moravia, and Silesia. In these regions the pronunciation is different from common Czech but also naming of particular objects may differ. The significance of these dialects is declining due to mass media and education but there can still be some differences found compared to the common Czech language. These differences were not evaluated in the previous research. The dialect words may influence the name agreement as pictures with more than one name are more difficult to name and cannot be recommended to be used in picture naming.

This normative study aimed to verify recognition and name agreement of a set of black and white pictures from our previous research on a large Czech population. We created the electronic form accessible via the internet for this purpose and wondered whether this electronic way of picture name agreement is feasible. The sample included more than 6,000 participants from all regions of the country and they were of different ages and education which is unique. We explored the influence of sociodemographic factors on name agreement. The outcome of this study is the set of well-characterized, unambiguously named and standardized pictures freely available for multicultural replication.

Methods

Procedure

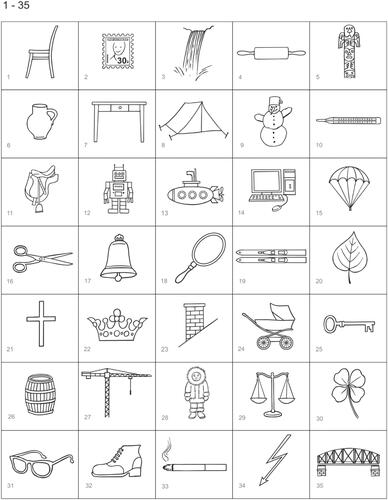

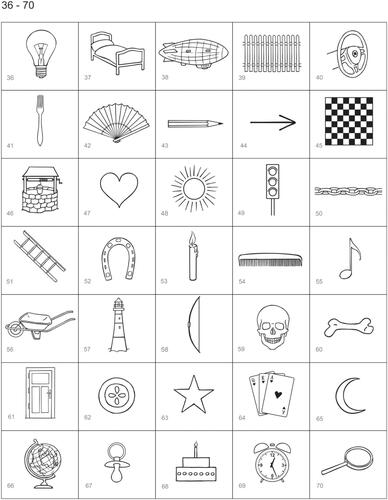

A set of 70 pictures for this study () was chosen based on our previous research (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018). The current study extends it, uses the best pictures on a large population across the whole country and with the different data collection.

Figure 1. Seventy pictures used individually for name agreement in an electronic form completed by 5,290 participants in the Czech national study.

The name agreement of this set of pictures was verified via the internet. Electronic way of testing was chosen in order to disseminate the test across the whole country and to obtain as many respondents as possible. All the 70 pictures were arrayed into an electronic form together with informed consent, sociodemographic questions (age, gender, education, a region of residence, mother language), questions regarding the past medical history (epilepsy, neurological brain disorder, addiction, unconsciousness, and psychiatric disorder), and the Czech version of the Alzheimer Dementia 8 questionnaire (AD8-CZ). The AD8 is a brief, sensitive questionnaire querying memory, orientation, judgment, and function that reliably differentiates between nondemented and demented individuals. Using a cutoff of two items endorsed, the area under the curve was 0.8, suggesting good to excellent discrimination, sensitivity was 74%, and specificity was 86% (Galvin et al., Citation2005). The pictures were presented consecutively, and the participants had to write their names into an empty field under each picture without any clue. They were instructed to use one word only. We asked them to be honest and to complete the form by themselves without any help that would invalidate the results of the test. There was no time restriction for filling-in the form. Our aim was just to find out whether a picture was named correctly or differently than was expected or at all. The form was distributed using links on different websites, advertising agencies, email, etc.

The pictures were considered as correctly named when the name was correct and correspond to the expected modal name stemming from our previous report (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018). Typing errors were tolerated. Dialect or slang names were considered as errors. Unnamed pictures were considered as errors.

The name agreement was calculated using two measurements. Firstly, the name agreement was counted as a percentage of correct answers out of the total number of answers. Secondly, the H statistic indicates the alternative names that the subjects used for the particular picture. It shows the diversity of the names used for a given picture. H index was computed following Snodgrass and Vanderwart (Citation1980). A picture that was given the same name from every subject in the sample (excluding unnamed items) has an H-value of 0.00. Increasing H values indicate decreasing name agreement due to naming diversity.

Participants

The electronic form was filled in by 6,055 participants across the whole country. It was open to everyone willing to participate in and to sign electronic informed consent. Incomplete responses (n = 552) and respondents whose mother language was not Czech (n = 213) were excluded from further analysis. The group for final evaluation comprised of 5,290 respondents (age ranged from 11 to 90 years, the average age ± SD was 53 ± 15 years, 77% of women, years of completed education 15 ± 3 years, education range 8–28 years). The participants came from all regions of the country. The proportion of participants in each region corresponds with the number of inhabitants in that region, except for Prague, where most of the participants came from. This can be explained by the geographical proximity of the capital city and our institute ().

Table 1. The number of study participants from each region in comparison with the total number of inhabitants in each region.

The whole normative sample was divided into several subgroups according to the following factors: gender, education, age, subjective cognitive impairment and history of brain impairment. Subgrouping details follow.

Education was used to divide the sample into the following groups: primary education, secondary education without and with a school-leaving general certificate of secondary education (GCSE) and university education. The GCSE certificate is the final high school examination before entering university or college studies and usually corresponds to 12–13 years of schooling in the Czech Republic.

The sample was dichotomized into a younger and older group according to age median of 56 years.

Subjective memory impairment was assessed by self-evaluation using the AD8-CZ questionnaire. It enables to estimate cognition in this remote way. Participants with a score of two points or higher were considered as having possible subjective cognitive impairment. The majority of participants (n = 4,283, 81%) had no subjective cognitive problems according to AD8-CZ score below two points. The results of participants with subjective memory impairment were compared to those without subjective memory impairment.

History of brain impairment was evaluated using questions of past medical history regarding disorders or factors that could affect mental function such as (1) any serious brain damage in the past (e.g., stroke, trauma, neurological infections, tumor, surgery), (2) a history of unconsciousness lasting longer than five minutes, (3) seizures, (4) a history of psychiatric illness or treatment, (5) current use of psychoactive medication (e.g., antidepressants, neuroleptics, anxiolytics, or hypnotics), and (6) abuse of drugs or alcohol. We usually use them in our normative studies of cognitive tests, for example, the Mini-Mental State Examination or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (Bartos & Fayette, Citation2018; Bartos & Raisova, Citation2016). Participants were considered healthy if none of the conditions was present. The criteria for participants with no history of brain impairment were fulfilled by 4,035 participants (76%).

If at least one of the conditions was present the subject was considered as having a history of brain impairment. The sample was subdivided intotwo subgroups involving healthy individuals and those with some history of brain impairment that might influence the results of the study.

The analysis was conducted on two groups: the whole sample and the subset of older individuals (56 years and older, 56 years was the median age of the whole sample) to evaluate name agreement on the population where decline of cognitive functions is more prevalent.

Statistical analysis

Pictures’ names were dichotomized into two categories only—correct naming and wrong naming/unnamed. Therefore the Chi-square test was used to evaluate the influence of gender, education, history of brain impairment, subjective cognitive impairment and age on the name agreement. To assess the simultaneous sociodemographic influence on the name agreement we also performed a binomial logistic regression with naming agreement as the dependent categorical variable and age, gender, education and AD8 score as predictor variables in the whole group (n = 5,290). The correlation between word frequency in the Czech language and name agreement was calculated using the Spearman correlation coefficient. p-Value was adjusted for multiple comparisons of 70 pictures (0.05/70 = 0.000714). Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS (Version 23). Multiple logistic regression was analyzed for each single picture name using the enter method in MedCalc.

Results

Description of normative results

The name agreement of all 70 pictures is presented in . Most of the pictures had a name agreement above 90%, only four pictures (saddle, mirror, zeppelin, and lighthouse) had name agreement between 85 and 90%. The average name agreement of all pictures was 98%.

Table 2. List of all the 70 picture names in Czech and English equivalents obtained from 5,290 participants and their naming and demographic characteristics.

The results in the subset of older individuals showed similar results. Most of the pictures had name agreement above 90%, only four pictures (saddle, mirror, zeppelin, and lighthouse) had name agreement between 80 and 90% (three pictures had name agreement below 85%—saddle, mirror, and lighthouse).

also contains H indices for all pictures. The average H is 0.18 which is very low and indicates a high name agreement of the picture set. Only several pictures have a little raised H index values (saddle, mirror, zeppelin, lighthouse, and wheelbarrow) which correspond to their lower name agreement in %.

The binomial logistic regression of all the pictures is also presented in . Pictures can be classified into three groups. The first most useful group of 14 pictures for future research is entirely independent of all sociodemographic factors and has a high name agreement at the same time. They include (the order is according to ): table, scissors, bell, ski, crown, chimney, glasses, steering wheel, heart, chain, ladder, horseshoe, bone, alarm clock. Half of them were influenced by AD8 score: table, ski, crown, chimney, steering, heel, chain, and ladder. The second group comprised of five pictures which correlated with all sociodemographic factors: waterfall, crane, zeppelin, chessboard, and soother. The third group of all the other pictures was influenced by one or two sociodemographic factors.

The influence of variables on the name agreement

Gender influence

The influence of gender on name agreement is summarized in Table 3. The results between men and women in the whole sample did not differ in 58 pictures. Name agreement between men and women was statistically different in 12 pictures: snowman, saddle, computer, crane, Eskimo, clover, cigarette, zeppelin, chessboard, well, moon, and soother (). The differences were mostly small, ranging from 0.9 to 7.7%.

Table 3. Pictures with significant difference in name agreement between men and women.

The biggest difference, albeit up to 8% only, was found in moon, soother, saddle, chessboard, and zeppelin. Women performed better in naming objects concerning babies, cooking or daily life.

Gender differences in the older participants subgroup were found in nine pictures: saddle, submarine, crane, Eskimo, clover, zeppelin, chessboard, well, and soother. The differences in naming ranged from 2.4 to 9.9% (not shown). These results correspond closely to those in the whole population group.

Education influence

To assess the influence of education on name agreement, the participants were divided into four categories according to their education level: primary education (n = 148), secondary education without the general certificate of secondary education (GCSE) (n = 706), secondary education with GCSE (n = 2,353) and university education (n = 2,083).

The results among all education groups in the whole sample did not differ in 61 pictures. Name agreement was statistically different in nine pictures: waterfall, totem, crane, zeppelin, chessboard, note, lighthouse, globe, and soother. The difference between primary and university education groups ranged from 3.7 to 10.9% ().

Table 4. Pictures with significant difference in name agreement across different education categories.

The older participants subgroup was divided into the same four categories according to their education level: primary education (n = 90), secondary education without GCSE (n = 397), secondary education with GCSE (n = 1,305) and university education (n = 904).

The results among education groups in the older participants sample did not differ in 66 pictures. Name agreement was statistically different in four pictures: totem, scale, zeppelin, and note. The difference in naming ranged from 1.6 to 13.4% (not shown). These results correspond closely to those in the whole population group.

Age influence

To perform age influence analysis, the whole sample was divided into two groups based on median age of the whole sample which was 56 years. The differences between younger (˂56 years) and older (≥56 years) participants were analyzed.

The results between these two groups did not differ in 53 pictures. Name agreement was significantly different in 17 pictures: rolling pin, jug, thermometer, saddle, submarine, computer, mirror, leaf, clover, fork, chessboard, well, note, lighthouse, door, cake, and moon. However, the differences were small, ranging from 1.0 to 12% ().

Table 5. Pictures with significant difference in name agreement between younger and older participants.

Influence of subjective cognitive impairment

The name agreement between participants with and without subjective cognitive impairment (according to the results of the AD8-CZ questionnaire) in the whole sample did not differ in 68 pictures. A significant difference was found in two pictures: chair and chain. The differences were very small, 0.9 and 0.8%, respectively ().

Table 6. Pictures with significant difference in name agreement between participants with and without subjective cognitive impairment.

Name agreement was not different between participants with and without possible subjective cognitive impairment in the subgroup of older individuals (not shown).

Influence of the history of brain impairment

The name agreement between participants with and without a history of brain impairment in the whole sample did not differ in 64 pictures. A significant difference was found in six pictures: saddle, steering wheel, arrow, chain, longbow, and moon. The differences were very small, ranging from 0.7 to 3.9% (). Name agreement was not different between participants with and without a history of brain impairment in the subgroup of older individuals (not shown).

Table 7. Pictures with significant difference in name agreement between participants with and without history of brain impairment.

Word frequency influence

The influence of word frequency of the picture names in Czech language on the name agreement was analyzed. Name agreement and word frequency correlated significantly (rs = −0.361, p = 0.007).

Discussion

The main outcome of this normative study is the set of 70 carefully drawn and selected pictures that can be named with one word only and with perfect name agreement (). All the pictures had the name agreement above 85%, 66 of them have name agreement above 90%, and the average of all pictures was 98% despite thousands of responses. Each picture is also well-characterized in terms of sociodemographic and other factors. These are outcomes of a long-term development. Firstly, we created and re-drew black-and-white pictures several times. Then they were named by more than 200 respondents from Prague and Central Bohemia (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018). Finally, we increased the number to 5,290 participants, their age range (11–90 years), their education range (8–28 years) and expand to all regions of the country in the current study. The correct drawings of concepts from our previous preliminary research (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018) was confirmed and validated by high name agreement and absent or minimal sociodemographic influence. This is an important prerequisite for further use of these representative pictures in research, diagnosis, and therapy.

We and others suggest that name agreement is a crucial variable for picture naming (Kremin et al., Citation2003). However, some standardized stimuli have modal name agreement below our arbitrary cutoff of 90%. The multilingual naming test surprisingly contains pictures with a low naming agreement or more expressions from healthy individuals (e.g., gauge, barometer, manometer—82%, mortar—61%, mallet—67%, anvil—75%, swing—75%) (Gollan et al., Citation2012; Ivanova et al., Citation2013). Other groups offer their picture sets that also contain much lower agreement, for example, as low as 20%! (Bates et al., Citation2003; Brodeur et al., Citation2010; Cycowicz et al., Citation1997; Snodgrass & Vanderwart, Citation1980). The average name agreement was from 72 and 85% (depending on the language) using line-drawn pictures (Bates et al., Citation2003) or 64% using even photos of objects and presented as a normative study (Brodeur et al., Citation2010). One would expect a higher percentage for photos than those for black-and-white drawings. A mean of H index values was also higher for photos (1.7) or those with black-and-white drawings (0.6 or 0.7–1.2) than our result (0.2) (Bates et al., Citation2003; Brodeur et al., Citation2010; Snodgrass & Vanderwart, Citation1980). Such a finding indicates that the participants used fewer alternative names to identify our selection of objects. Recognition and naming of some pictures seem to be more dependent on the way how the concept itself is drawn or shown than the way of presentation (a black-and-white drawing, a colored picture or a photo). It could also explain a rather contra intuitive finding for photos in comparison with black-and-white drawings. The authors’ intention was to have a wide range and diverse objects which resulted in a reduction of modal name agreement and an increase of the H value. The name agreement was 87% obtained for the 260 Snodgrass & Vanderwart original pictures (Snodgrass & Vanderwart, Citation1980). Cycowicz and colleagues reported a name agreement of 67 or 73% (Cycowicz et al., Citation1997). Bonin and colleagues have created a set of 299 new pictures to complement the Snodgrass and Vanderwart set. They obtained a modal name agreement of 78% and an H value of 0.7 (Bonin et al., Citation2003). Navarrete and colleagues achieved a name agreement of 56% and H index value of 1.5 (Navarrete et al., Citation2019). Altogether, it is difficult to imagine how cognitive or language deficits can be identified correctly in patients when some pictures are not properly named even by healthy individuals. We propose to select those objects with high or perfect name agreement with one word only by healthy individuals for development of new picture naming tests. It is better to have a smaller number of high quality pictures than plenty of pictures with moderate or poor name agreement. Less is more.

We think that there is one important condition in a picture selection, that is, to use pictures that can be named by one word only in a given language. This may increase response consistency and consequently name agreement. Some examples show problems with multi-word naming which has an impact on name agreement (“pepper” or “red pepper,” “gift box” or “decorative box” or just “box”) (Brodeur et al., Citation2010).

The percentage of correct naming of the same pictures also varies according to the cultural background and language (Kremin et al., Citation2003). For example, our door (99% name agreement) has high name agreement equivalents of 98% in English, 99% in French, 78% in Dutch, 96% in German, 98%, in Italian, 98% in Spanish, 90% in Swedish and 100% in Russian. So this object can be considered very suitable and universal for further use on a global scale because it has a good degree of matching in many different languages regardless of their different designs. Conversely, the chain may be problematic for some languages (Czech 100%, English 98%, French 93%, Dutch 67%, German 48%, Italian 92%, Spanish 89%, Swedish 51%, Russian 40%) (Kremin et al., Citation2003). Reasons for the discrepancy in naming quality may include the type of a particular drawing or different related terms in a given language, and other factors.

Name agreement of almost all the pictures or the majority of them was not influenced by sociodemographic and other factors (age, education, gender, cognitive health) (). The name agreement was influenced mostly by the existence of multiple names for a particular picture, due to dialect, slang word or abbreviation (e.g., wheelbarrow, computer), which are the most common reasons for naming disagreement found in other sources (Vitkovitch & Tyrrell, Citation1995).

The extent of this study is unique not only in the Czech Republic, but also in the world, as it was conducted on an extensive sample of more than 6,000 participants. Due to the electronic form of testing, it was possible to recruit participants from all regions of the country, covering the whole age and education spectrum of the population. The age of the participants ranged from 11 to 90 and the education level contained all educational levels in the Czech Republic, from elementary school to university. The participants came from all regions of the country and their number in each region corresponds with the number of inhabitants of that particular region. The results of this study are thus very representative. In addition, we proved that the electronic way of name agreement validation via the internet is feasible.

The involvement of participants from all the regions in the study was useful as it helped to uncover some issues that were not apparent in our previous studies. One of the issues was the regional differences in naming. Several dialects different from official Czech language are spoken in the Czech Republic, especially in Moravia and Silesia. The participants in previous studies (Bartos et al., Citation2013; Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018) came from Prague and its surroundings so these differences did not appear. People living in regions where the dialect is spoken, frequently use dialect words and names instead of correct Czech words. This fact influenced the naming agreement of some pictures in this study, for example, wheelbarrow, as the participants often used dialect words to name these pictures. From previous research, it is known that pictures with more than one name are more difficult to name and cannot be recommended to be used in picture naming tests (Vitkovitch & Tyrrell, Citation1995). Our finding suggests that picture naming tests should be validated on subjects coming from different regions to capture regional differences in naming.

The gender differences in naming were quite small and women performed almost identically as men, contrary to other findings, where men outperformed women (Randolph et al., Citation1999). But there were significant differences in the naming of particular objects in our study. Men performed better in naming technical objects, tools or machines, while women performed better in naming objects concerning babies, cooking or daily life. This finding indicates, that performance of a particular gender in the naming test may be dependent on a selection of pictures, because some objects are more familiar to a particular gender. This is in line with other research on this issue (Hall et al., Citation2012) and it implicates that a naming test should contain only pictures that have the same name agreement for both men and women or the selection of pictures should be balanced in order to avoid systematic gender bias.

Some limitations in the current study should be mentioned. Picture aspects other than name agreement were not acquired, e.g., image agreement, conceptual familiarity, age of acquisition, or visual complexity. Our main aim was to verify the high name agreement of previously selected pictures (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018) in a very large Czech population across every region. Participants filled in several questionnaires followed by naming of 70 pictures which was a time-demanding task. We did not want to put more burden on them. In contrast, we did want to ensure more compliance to complete a long electronic form. Thus we achieved a high 91% filling rate of the electronic form. Complex data collection of all picture aspects can last for five hours for each subject as experienced in the Persian study (Ghasisin et al., Citation2015). It would not be feasible to carry out with our participants. Moreover, the purpose of our study was to obtain Czech norms just for name agreement. The subsequent studies will be focused on picture naming in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative dementias to rank these pictures into easy, moderate and difficult categories according to the naming difficulty of these patients. Therefore we focused on name agreement since it has key importance for our purposes and goals.

Another limitation is caused by the electronic way of data collection. Some participants might have mild cognitive impairment in the older group. It is a disadvantage of convenient testing. However, we assume that the number of such individuals capable to use computers was negligible in our very large sample size. In addition, they are representatives of the usual general population. Moreover, the results correspond to what we obtained using personal testing (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018). We also included the AD8 questionnaire which is a valid proxy of cognitive status (Galvin et al., Citation2005). All but two pictures were not statistically significant between two subgroups based on AD8 scores (). The best answer can give personal examinations in patients with cognitive impairment. This subsequent study is currently underway for a subset of the most relevant pictures stemming from this report, that is, those which are easy to name by the normal elderly and are difficult to be named by the patients with cognitive disorders.

The level of education could affect name agreement but it was not found for most pictures in this study. The reason may be carefully selected and precisely drawn pictures that can be easily recognized and named by everybody regardless of educational attainment. In addition, the best pictures were selected after the previous picture sorting (Bartos & Hohinova, Citation2018). The sample was well educated similarly to other studies (Ghasisin et al., Citation2015). Secondary education with GCSE and university education was present in 84% of participants. It would be interesting to explore the name agreement specifically in lower educated people.

The great advantage is to collect many responses in an easy, quick, cheap and representative way. The drawback of this approach is the fact that participants are not overseen and may use some external help. Since we anticipated it the participants were asked to be honest and complete the form by themselves. Our sample is so considerable that these exceptions would not alter the results. In addition, we assume that the majority of people are honest during completing the form. They were not in a testing situation or experiment with the aim to succeed. We just asked them to help us with our research and to name pictures. This assumption is confirmed by the fact that pictures were named using several terms as evidenced by H index or were left unnamed.

In conclusion, the electronic form was found to be a useful tool for name agreement evaluation in a large population. The form can be easily used in other countries and languages to find unambiguously named pictures. We offer dozens of black and white pictures that were precisely drawn and selected several times. This set with high name agreement with one word can be validated in other languages and cultural backgrounds and can be used for research and therapeutic purposes or naming test development. A subgroup of drawings can be used for multilingual picture naming test worldwide if consistency is proved for them across different languages. We provide materials free of charge to all interested readers, researches or practicing personnel. You can download all the pictures and you can be inspired by the electronic form for your data collection in the English section of our website www.abadeco.cz/english.

Ethical approval

The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charles University, Third Faculty of Medicine, Prague. All participants signed an informed consent in the electronic form.

Author contributions

Ales Bartos: the design of the study, the electronic form and tables, data collection, naming evaluation, statistical analysis, major manuscript revisions. Michaela Hohinova: the design of the study, data collection, naming evaluation. Marie Holla: statistical analysis, manuscript draft.

Disclosure statement

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alario, F., & Ferrand, L. (1999). A set of 400 pictures standardized for French: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, and age of acquisition. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 31(3), 531–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200732

- Bakhtiar, M., Nilipour, R., & Weekes, B. (2013). Predictors of timed picture naming in Persian. Behavior Research Methods, 45(3), 834–841. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0298-6

- Bartos, A., Čermáková, P., Orlíková, H., Al-Hajjar, M., & Řípová, D. (2013). A set of high name agreement pictures for evaluation and therapy of language and cognitive deficits. Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery, 109(4), 453–462.

- Bartos, A., & Fayette, D. (2018). Validation of the Czech Montreal Cognitive Assessment for mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease and Czech norms in 1,552 elderly persons. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 46(5–6), 335–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000494489

- Bartos, A., & Hohinova, M. (2018). A set of pictures with the opposite difficulty of naming. Czech and Slovak Neurology and Neurosurgery, 81(4), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2018466

- Bartos, A., & Raisova, M. (2016). The mini-mental state examination: Czech norms and cutoffs for mild dementia and mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 42(1–2), 50–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1159/000446426

- Bates, E., D’Amico, S., Jacobsen, T., Székely, A., Andonova, E., Devescovi, A., Herron, D., Ching Lu, C., Pechmann, T., Pléh, C., Wicha, N., Federmeier, K., Gerdjikova, I., Gutierrez, G., Hung, D., Hsu, J., Iyer, G., Kohnert, K., Mehotcheva, T., … Tzeng, O. (2003). Timed picture naming in seven languages. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10(2), 344–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196494

- Bonin, P., Chalard, M., Méot, A., & Fayol, M. (2002). The determinants of spoken and written picture naming latencies. British Journal of Psychology, 93(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000712602162463

- Bonin, P., Peereman, R., Malardier, N., Méot, A., & Chalard, M. (2003). A new set of 299 pictures for psycholinguistic studies: French norms for name agreement, image agreement, conceptual familiarity, visual complexity, image variability, age of acquisition, and naming latencies. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers: a Journal of the Psychonomic Society, 35(1), 158–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195507

- Boukadi, M., Zouaidi, C., & Wilson, M. A. (2016). Norms for name agreement, familiarity, subjective frequency, and imageability for 348 object names in Tunisian Arabic. Behavior Research Methods, 48(2), 585–599. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0602-3

- Brodeur, M. B., Dionne-Dostie, E., Montreuil, T., & Lepage, M. (2010). The Bank of Standardized Stimuli (BOSS), a new set of 480 normative photos of objects to be used as visual stimuli in cognitive research. PLoS One, 5(5), e10773. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010773

- Cycowicz, Y. M., Friedman, D., Rothstein, M., & Snodgrass, J. G. (1997). Picture naming by young children: Norms for name agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 65(2), 171–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1996.2356

- Dell, G., Schwartz, M., Martin, N., Saffran, E., & Gagnon, D. (1997). Lexical Access in Aphasic and Nonaphasic Speakers. Psychological Review, 104(4), 801–838. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.104.4.801

- Dimitropoulou, M., Duñabeitia, J. A., Blitsas, P., & Carreiras, M. (2009). A standardized set of 260 pictures for Modern Greek: Norms for name agreement, age of acquisition, and visual complexity. Behavior Research Methods, 41(2), 584–589. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.2.584

- Galvin, J. E., Roe, C. M., Powlishta, K. K., Coats, M. A., Muich, S. J., Grant, E., Miller, J. P., Storandt, M., & Morris, J. C. (2005). The AD8: A brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology, 65(4), 559–564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000172958.95282.2a

- George, A., & Mathuranath, P. S. (2007). Community-based naming agreement, familiarity, image agreement and visual complexity ratings among adult Indians. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 10(2), 92–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-2327.33216

- Ghasisin, L., Yadegari, F., Rahgozar, M., Nazari, A., & Rastegarianzade, N. (2015). A new set of 272 pictures for psycholinguistic studies: Persian norms for name agreement, image agreement, conceptual familiarity, visual complexity, and age of acquisition. Behavior Research Methods, 47(4), 1148–1158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0537-0

- Gollan, T. H., Weissberger, G. H., Runnqvist, E., Montoya, R. I., & Cera, C. M. (2012). Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: A multi-lingual naming test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 15(3), 594–615. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728911000332

- Hall, J. R., Vo, H. T., Johnson, L. A., Wiechmann, A., & O’Bryant, S. E. (2012). Boston Naming Test: Gender differences in older adults with and without Alzheimer’s dementia. Psychology, 3(6), 485–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.36068

- Ivanova, I., Salmon, D. P., & Gollan, T. H. (2013). The multilingual naming test in Alzheimer’s disease: Clues to the origin of naming impairments. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 19(3), 272–283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617712001282

- Kremin, H., Akhutina, T., Basso, A., Davidoff, J., De Wilde, M., Kitzing, P., Lorenz, A., Perrier, D., van der Sandt-Koenderman, M., Vendrell, J., Weniger, D., Apt, P., Arabia, C., De Bleser, R., Cohen, H., Corbineau, M., Dolivet, M. C., Hirsh, K., Lehoux, E., … Vish-Brink, E. (2003). A cross-linguistic data bank for oral picture naming in Dutch, English, German, French, Italian, Russian, Spanish, and Swedish (PEDOI). Brain and Cognition, 53(2), 243–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00119-2

- Moayedfar, S., Purmohammad, M., Shafa, N., Shafa, N., & Ghasisin, L. (2019). Analysis of naming processing stages in patients with mild Alzheimer. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2019.1599894

- Navarrete, E., Arcara, G., Mondini, S., & Penolazzi, B. (2019). Italian norms and naming latencies for 357 high quality color images. PLoS One, 14(2), e0209524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209524

- Pind, J., Jónsdóttir, H., Gissurardottir, H., & Jónsson, F. (2000). Icelandic norms for the Snodgrass and Vanderwart (1980) pictures: Name and image agreement, familiarity, and age of acquisition. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 41(1), 41–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00169

- Pompéia, S., Miranda, M. C., & Bueno, F. A. (2001). A set of 400 pictures standardised for Portuguese: Norms for name agreement, familiarity and visual complexity for children and adults. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 59(2B), 330–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X2001000300004

- Raman, I., Raman, E., & Mertan, B. (2014). A standardized set of 260 pictures for Turkish: Norms of name and image agreement, age of acquisition, visual complexity, and conceptual familiarity. Behavior Research Methods, 46(2), 588–595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-013-0376-4

- Randolph, C., Lansing, A. E., Ivnik, R. J., Cullum, C. M., & Hermann, B. P. (1999). Determinants of confrontation naming performance. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 14(6), 489–496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/14.6.489

- Rogić, M., Jerončić, A., Bošnjak, M., Sedlar, A., Hren, D., & Deletis, V. (2013). A visual object naming task standardized for the Croatian language: A tool for research and clinical practice. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1144–1158.

- Sanfeliu, M. C., & Fernandez, A. (1996). A set of 254 Snodgrass-Vanderwart pictures standardized for Spanish: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28(4), 537–555. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03200541

- Snodgrass, J. G., & Vanderwart, M. (1980). A standardized set of 260 pictures: Norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6(2), 174–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.6.2.174

- Torrance, M., Nottbusch, G., Alves, R. A., Arfé, B., Chanquoy, L., Chukharev-Hudilainen, E., Dimakos, I., Fidalgo, R., Hyönä, J., Jóhannesson, Ó. I., Madjarov, G., Pauly, D. N., Uppstad, P. H., van Waes, L., Vernon, M., & Wengelin, Å. (2018). Timed written picture naming in 14 European languages. Behavior Research Methods, 50(2), 744–758. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0902-x

- Tsaparina, D., Bonin, P., & Méot, A. (2011). Russian norms for name agreement, image agreement for the colorized version of the Snodgrass and Vanderwart pictures and age of acquisition, conceptual familiarity, and imageability scores for modal object names. Behavior Research Methods, 43(4), 1085–1099. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0121-9

- Vitkovitch, M., & Tyrrell, L. (1995). Sources of disagreement in object naming. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A, 48(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749508401419

- Yoon, C., Feinberg, F., Luo, T., Hedden, T., Gutchess, A. H., Chen, H.-Y M., Mikels, J. A., Jiao, S., & Park, D. C. (2004). A cross-culturally standardized set of pictures for younger and older adults: American and Chinese norms for name agreement, concept agreement, and familiarity. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 639–649. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206545