ABSTRACT

Expanding service coverage and achieving universal health coverage (UHC) is a priority for many low- and middle-income countries. Though UHC is a long-term goal, its importance and relevance have only increased since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The first step on the road to UHC is to define and develop essential packages of health services (EPHSs), a list of clinical and public health services that a government has deemed a priority and is to provide. However, the nature of these lists of services in low- and lower-middle-income countries is largely unknown. This study examines the contents of 45 countries’ EPHSs to determine the inclusion of essential UHC (EUHC) services as defined by the Disease Control Priorities, which comprises 21 specific essential packages of interventions. EPHSs were collected from publicly available sources and their contents were analyzed in two stages, firstly, to determine the level of specificity and detail of the content of EPHSs and, secondly, to determine which essential UHC services were included. Findings show that there are large variations in the level of specificity among EPHSs and that though EUHC services are included to a large extent, variations exist regarding which services are included between countries. The results provide an overview of how countries are designing EPHSs as a policy tool and are progressing toward providing a full range of EUHC services. Additionally, the study introduces new tools and methods for UHC policy analysts and researchers to study the contents of EPHSs in future investigations.

Introduction

Through the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals the world’s countries have committed to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) by 2030. Globally, UHC coverage improved from 2000 to 2017 as illustrated by the UHC service coverage index.Citation1 However, low-income countries (LICs) still have the smallest share of people covered by essential health services, and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) have the largest number of people who still lack coverage.Citation1 To achieve UHC, policymakers have to determine how to allocate resources for health efficiently and equitably. Essential packages of health services (EPHSs), defined as “a list of clinical and public health services that a government has determined as priority for the country … that the government is providing or aspiring to provide”Citation2(p2) have been regarded as a useful mechanism to prioritize resources for health on the grounds of effectiveness and relative cost, increasing equity, reducing poverty, and political empowerment and accountability.Citation3 EPHSs have also been said to be an essential element in the creation of a sustainable and effective system of UHC.Citation4,Citation5 For LICs and LMICs, EPHSs that are made available to all, regardless of ability to pay, have been described as a pathway to UHC.Citation6

The World Bank’s Disease Control Priorities third edition (DCP3) provides a standard that countries can follow when determining which health services to include in their EPHSs. In particular, the DCP3 defines a model of essential UHC (EUHC), comprising 21 essential packages of interventions (POIs) that each address the concerns of a particular health area through a mix of intersectoral policies and health sector interventions ().Citation7 The DCP3 EUHC model can inform program design when services and resources are being allocated. Designed to be acquired at an early stage of countries’ pathways to UHC, as well as having proven to be effective and cost-effective in low-resource settings,Citation8 the POIs include interventions that are context specific and can be prioritized by countries as they develop their EPHSs and progress toward achieving UHC. Collectively, the POIs consist of 218 interventions, systematically selected using criteria of value for money, disease burden addressed, and implementation feasibility.Citation7 A subset of 108 of these interventions forms a highest priority package (HPP) based on more stringent criteria. Though the costs estimated for HPP and EUHC are substantial, the incremental annual cost per person of the HPP is 26 USD, which has been deemed to be affordable for low-income countries.Citation8 Other frameworks, such as the UHC service coverage index and the UHC Compendium,Citation9 also delineate UHC services and interventions to progress toward UHC. However, the UHC service coverage index’s 14 tracer indicators, which fall under four essential health service areas, have been said to “not serve as a complete or exhaustive list of health services and interventions covered in a given country’s UHC programmes.”Citation1(p14) The World Health Organization’s UHC Compendium takes a comprehensive approach but is still not complete. Interventions in program areas such as child health and primary care are still being developed,Citation9 making it difficult to apply for a comprehensive review.

Table 1. List of DCP3 POIs7

The extent to which essential UHC services are included in country EPHSs is largely unknown. Previous studies have examined the contents of EPHSs using reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH)Citation2 and sexual and reproductive health and rightsCitation10 perspectives. Previous research has also examined countries’ provision of UHC services,Citation11 essential service coverage,Citation12 and the process and methods used to develop EPHSs.Citation13,Citation14 Though studies have noted that EPHSs vary across countries, not only in terms of their content and designCitation15 but also in terms of their specificity, intention, purpose, and scope across countries,Citation2–4 studying the content of EPHSs from a UHC lens has often been overlooked. The purpose of this study is to provide a better understanding of the inclusion of essential UHC services in EPHSs in low- and lower-middle-income countries based on the DCP3 model within a larger selection of countries. We examine the specificity of EPHSs’ contents to understand how countries are defining and designing their EPHSs as a policy tool, and we examine the comprehensiveness EPHSs to provide an overview of how countries are progressing toward offering a full range of essential UHC services from the HPP in their policies.

Material and Methods

Data Sources and Collection

Our study includes all 31 LICs and the 20 most populous LMICs, as classified by the World Bank country income classification.Citation16 The countries included face the greatest challenges in terms of disease burden and effective mobilization of and use of resources.Citation17 Data for six countries could not be located, and so the final data set consisted of 45 EPHSs in the form of government documents (see for details on documents included in the analysis). Data were collected in January and February 2020 from publicly available sources through an exhaustive Internet search by searching the websites and databases of government agencies, such as the Ministry of Health, as well as other relevant organizations to obtain primary data (i.e., government policy documents). Most EPHSs, defined in this study as a list of services that the government had determined as a priority or the country and are aspiring to provide, were found in documents such as health sector strategic plans, health development plans, and national health policies. Search terms used to locate countries’ EPHSs used a combination of keywords and phrases that included, but were not limited to, “essential package of health services,” “essential health service package,” “basic health service package,” “minimum health package,” “national health service package,” “essential universal health coverage package,” and “universal health coverage package.” This study focuses on the primary health care (PHC) level because achieving UHC is contingent on prioritizing investments in PHCCitation1 and most resources will be needed to support services at this level.Citation17 As such, EPHSs concerning only PHC or all levels of care were collected. EPHSs that were not in English were translated into English.

Analytical Approach

In order to better understand how the contents of low- and lower-middle-income countries’ EPHSs aligned with the DCP3’s HPP, the first objective was to categorize EPHSs based on the level of specificity and detail of their contents; that is, whether they contained a list of clinical and public health services. The second objective was to examine which essential UHC services from the HPP were included in EPHSs to identify trends and gaps. As such, the analysis was conducted in two stages: the first categorized the EPHSs based on the degree of specificity of contents, and the second matched the services in EPHSs against the DCP3 HPP packages of interventions. EPHSs were analyzed using policy content analysis, which focuses on the substance of policies.Citation18,Citation19

Case Classification Scheme

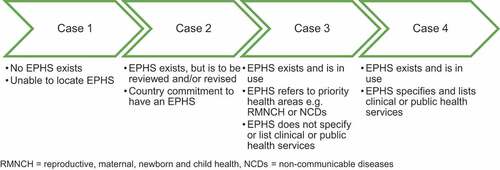

The first stage of analysis was performed by reviewing the contents of EPHSs through multiple readings and categorizing them according to a case classification scheme along a spectrum of four categories: case one, case two, case three, or case four (see ). The case classification determined which EPHSs’ contents were eligible for the second level of analysis, in which the content of the EPHS would be matched and mapped against the POIs that make up the DCP3’s HPP. To be eligible for the second level of analysis, EPHSs had to clearly outline a list of clinical and public health services and be categorized as case four.

Matching of EPHSs Against DCP3

The second stage of analysis consisted of a high-level matching performed through a second round of reviewing the EPHSs. This matching was conceptual rather than verbatim and was conducted by comparing the content of an EPHSs against the POIs that make up the DCP3’s HPP. The inclusion of POIs was evaluated by comparing and matching the list of services in EPHSs to the specific interventions under each POI (see ). Only 14 out of the 21 DCP3 POIs were considered because the remaining 7 POIs do not have specific interventions that are deliverable at the PHC level through community- and health center–level platforms (see ). POIs were marked as included if EPHSs contained services that explicitly or implicitly matched, or were conceptually related to, the specific interventions under each POI. EPHSs did not need to include all of the interventions contained within each POI to be marked as included in the analysis. Instead, it was sufficient for an EPHS to include one of the specific interventions from the POI. To increase reliability of the analysis, peer debriefing with two external experts was conducted. Furthermore, documents were reviewed twice to ensure dependability, and an audit trail in the form of extensive notes was kept.

Results

EPHS Case Classification

shows the case classification of the countries studied disaggregated by country income level. Twelve percent of countries’ EPHSs did not exist or were unable to be located at the time of data collection and were thus classified as case one. One-third were classified as case two, 24% as case three, and 31% as case four.

Table 2. Case classification results disaggregated by country income level

Inclusion of POIs in EPHSs

Case four EPHSs comprised 36% of the 45 EPHSs reviewed. All 16 case four EPHSs included 10 or more of the 14 POIs (see ). Three (19%) of the case four EPHSs, from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Congo, included all 14 POIs. More than half (51%) of case four EPHSs included 13 or more POIs in their EPHSs. Ghana’s EPHS included the least POIs, with 10 out of 14. POIs 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 15 were included in all case four EPHSs. POI 20 (palliative care and pain control) was included in only three (19%) of the EPHSs and was the least frequently included POI. Of all case four EPHSs, Ghana’s EPHS was the only one to not contain POI 3 (school-age health and development), and North Korea’s EPHS was the only one to not contain POI 13 (mental, neurological, and substance use disorders). As shown in , LICs included 80% of POIs in their EPHSs, whereas LMICs included 90%.

Table 3. Inclusion of the DCP3 POIs in EPHSs disaggregated by country income level

Discussion

Study results show that there are large variations in how detailed EPHSs are. EPHS range from being unspecific and aspirational to explicit and operational. Within the most specific (case four) EPHSs, most DCP3 packages of interventions were included, though variations were found both across packages and between countries.

Specificity of EPHSs

Despite EPHSs being defined as a list of clinical and public health services prioritized by a government, most EPHSs in this study did not fit this definition. We found large variations in specificity and detail in how health services were described in EPHSs, corroborating previous research.Citation10,Citation15,Citation20 The appropriate level of specificity for EPHSs has been discussed in different countries and contexts. For example, in the United States, there was an extensive discussion on the level of detail of the essential benefit package as part of a health reform.Citation21 After reviewing evidence, policy makers decided on a high level of specificity arguing that for contents of essential health plans to be guided by scientific evidence, there need to be specific definitions and descriptions of what is included and excluded.Citation21 However, others heed that packages should compromise between generalizability and specificity to strike a balance between detail and freedom for doctors to adjust approaches and treatments for individual patients.Citation20 The range of specificity among EPHSs can be attributed to countries using them for different reasons and heterogenous policy objectives.Citation2 EPHSs’ uses range from a political instrument to mobilize resourcesCitation3 and a practical tool for implementation and useCitation22 to an accountability mechanism for citizens to be made aware of what services are available to them.Citation4

Currently, there is no conceptual framework to facilitate how specific the list of services in EPHSs should be; therefore, countries must decide for themselves how to define and specify a list of clinical and public health services in their EPHSs.Citation20 This contributes to discrepancies across countries’ EPHSs, as seen in . The variation in design and specificity of EPHSs will continue to be inherent because there is a lack of consensus as to which level of specificity is optimal. This highlights the usefulness and relevance of the case classification scheme for understanding these variations and illustrates how countries have developed and use EPHSs differently as a tool to progress toward UHC.

Inclusion of Essential UHC Services from the HPP in EPHSs

We also found variations in the inclusion of essential UHC services within EPHSs. This corroborates previous research that has shown the contents of EPHSs vary between countries.Citation2,Citation10,Citation15,Citation22 With limited available resources, trade-offs are inevitable for countries in terms of which priority disease areas and related programs are included within EPHSs.Citation23 Packages of interventions from the HPP have been designed with LICs’ limited resources in mind,Citation7 provide value for money, and address disease burden that contributes most to impoverishment. These packages can be adopted by both LICs and LMICs that are committed to rapid improvements to population health and increase progress toward UHC.Citation8 Still, 12% of POIs were not included in the sample of EPHSs analyzed. This indicates that the HPP appears to be an appropriate reference for examining and tracking the progress of the content of UHC policies in low resource settings.

Many LICs and LMICs are recipients of development assistance for health (DAH) from both public and private funders,Citation24 and though most external funders strive to align with country priorities, donors also have their own interests. Therefore, levels of DAH, and what health priorities DAH supports, can change for reasons independent of the needs in the recipient country.Citation7 A challenge for LICs and LMICs moving toward UHC is that, although they have full responsibility for EPHSs, the content and priorities within these EPHSs and the resources available for implementing them are to some degree influenced by external funders and the level of DAH. As a consequence, countries that are highly dependent on DAH can find it difficult to finance an EPHS that includes all of DCP3’s POIs because development assistance for health is often fragmented and earmarked for certain purposes.Citation25

RMNCH and infectious disease POIs were included in 96% of the EPHSs analyzed, which aligns with previous findings.Citation2,Citation22 The high level of inclusion of RMNCH and infectious diseases was expected because both areas account for a high burden of morbidity and mortality in LICs and LMICs.Citation26 However, the very high level of inclusion of these POIs is also a reflection of DAH priorities. The Millennium Development Goals specifically focused on RMNCH through goals four and five, and the creation of disease-specific initiatives such as the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund has directed resources toward communicable diseases such as AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria.Citation24 Nevertheless, in the current Sustainable Development Goals era, RMNCH and infectious disease remain prioritized in DAHCitation7,Citation24,Citation27 and can partly explain why these POIs remain the most included in EPHSs. Countries also prioritize noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) and injury POIs in their EPHSs, despite only 2% of total DAH being allocated to NCDs in 2018.Citation27 Though NCDs account for approximately 60% of the global burden of diseaseCitation28 and 80% of NCD deaths occur in LMICs, donors are not coordinating their “… responses to NCDs with their responses to maternal, neonatal, and child health problems, …”Citation23(p305) which may explain why these POIs were not included in countries’ EPHSs to the same extent as RMNCH POIs. POI 20, palliative care and pain control, was included in only 19% of the EPHSs despite a wealth of evidence demonstrating the burden of remediable health-related suffering and the effectiveness of palliative care and pain treatment. Previous research similarly found that 74% of countries do not integrate palliative care into their mainstream service provision.Citation29 The noninclusion of this POI in the EPHSs may also be because palliative care extends beyond the health sector and necessitates intersectoral cooperation in order to meet the food, housing, and transportation needs of citizens.Citation23

The overview of the inclusion of essential UHC services in EPHSs seen in indicates how countries are progressing toward offering a full range of essential services in their UHC policies. Because this study focuses on the contents of EPHSs, the study cannot speak to the implementation of EPHSs and the practicalities related to this in the field but complements research that discusses the process and methods used to develop EPHSs. Findings on the inclusion and, by extension, exclusion of services can serve as a reference for accountability and be used by civil society in advocating for governments to include services within EPHSs and to hold them accountable for their commitments.

Limitations

Because the content of a country’s EPHS can be divided across several policy documents, the review may not have completely captured the studied countries’ EPHSs. Furthermore, because contents of EPHSs were compared against and matched against the DCP3 on a conceptual level, the results may not capture all details of what is included within each package of intervention. Though the reliability of the findings is ensured by the overall approach provided by the DCP3 framework, future research could adopt a stricter approach where EPHSs are matched with all services in the POIs.

Conclusions

An Essential Package of Health Services specifying a list of services based on context-specific health needs and that accounts for cost-effectiveness and equity as well as financial risk protection can be an effective tool for advancing UHC reforms. Our review found that, although most countries have an EPHS, the majority do not specify a list of clinical and public health services that are included. This study provides an overview of the content of countries’ UHC, which is necessary when assessing how services align with burdens of disease, implementation feasibility, and cost-effectiveness. The case classification framework offers a tool for policy researchers and analysts to conceptualize and understand the variations in how countries are currently defining and designing their EPHSs differently as a policy tool.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge valuable input on methods and analysis from Eoghan Brady and Jeanna Holtz.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- WHO. Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage 2019 monitoring report: conference edition. World Health Organization; 2019 [ accessed 2020 Jan 19]. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/uhc_report_2019.pdf?ua=1.

- Wright J, Holtz J . Essential packages of health services in 24 countries: findings from a cross-country analysis. Health Finance and Governance project, Abt Associates Inc.; 2017 [accessed 2020 Feb 23].https://www.hfgproject.org/ephs-cross-country-analysis/ .

- Waddington C. Essential health packages: what are they for? What do they change? 2013 [accessed 2020 Feb 22]. https://www.mottmac.com/download/file/6125?cultureId=127

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Sakuma Y, Smith PC. Defining a health benefits package: what are the necessary processes? Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(1):39–10. doi:10.1080/23288604.2016.1124171.

- Glassman A, Giedion U, Smith PC, eds. What’s in, what’s out: designing benefits for universal health coverage. Washington, DC: Center For Global Development; 2017.

- Aman A, Gashumba D, Magaziner I, Nordström A. Financing universal health coverage: four steps to go from aspiration to action. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):902–03. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32095-1.

- Jamison DT, Alwan A, Mock CN, et al. Chapter 1. Universal health coverage and intersectoral action for health. In: Nugent R, Watkins DA, Adeyi O, Anand, S, Atun, R, Bertozzi, S, Bhutta, Z et al, et al., editors. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd Jamison, DT, Gelband, H, Horton, S, Jha, P, Laxminarayan, R, Mock, CN, and Nugent, R ed. Washington, DC: World Bank 8 ; 2017. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1.

- Jamison DT, Alwan A, Mock CN, Nugent R, Watkins D, Adeyi O, Anand S, Atun R, Bertozzi S, Bhutta Z, et al. Universal health coverage and intersectoral action for health: key messages from disease control priorities, 3rd edition. Lancet. 2018;391(10125):1108–20. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32906-9.

- WHO. Interventions by programme area. UHC compendium, repository of interventions for universal health coverage. 2021 Oct 10 [ accessed 2021 Oct 10]. https://www.who.int/universal-health-coverage/compendium/interventions-by-programme-area.

- Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health. Prioritizing essential packages of health services in six countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Partnership for Maternal, Newborn & Child Health; 2019 [accessed 2020 Feb 20]. https://www.who.int/pmnch/media/news/2019/WHO_One_PMNCH_report.pdf?ua=1

- Lozano R, Fullman N, Mumford JE, Knight, M, Barthelemy, CM, Abbafat, C, Abbastabar, H, Abd-Allah, F, Abdollahi, M, Abedi, A et al, et al. Measuring universal health coverage based on an index of effective coverage of health services in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396(10258):1250–84. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30750-9.

- Hogan DR, Stevens GA, Hosseinpoor AR, Boerma T. Monitoring universal health coverage within the Sustainable Development Goals: development and baseline data for an index of essential health services. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(2):e152–e168. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30472-2.

- Eregata GT, Hailu A, Geletu ZA, Memirie ST, Johansson KA, Stenberg K, Bertram MY, Aman A, Norheim OF. Revision of the ethiopian essential health service package: an explication of the process and methods used. Health Syst Reform. 2020;6(1):e1829313. doi:10.1080/23288604.2020.1829313.

- Verguet S, Hailu A, Eregata GT, Memirie ST, Johansson KA, Norheim OF. Toward universal health coverage in the post-COVID-19 era. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):380–87. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01268-y.

- Giedion U, Alfonso EA, Díaz Y. The impact of universal coverage schemes in the developing world: a review of the existing evidence. World Bank; 2013 [accessed 2020 Feb 24]. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/13302

- World Bank. Country classification: world bank country and lending groups. 2020 [ accessed 2020 Feb 24]. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- Stenberg K, Hanssen O, Edejer TTT, Bertram M, Brindley C, Meshreky A, Rosen JE, Stover J, Verboom P, Sanders R, et al. Financing transformative health systems towards achievement of the health sustainable development goals: a model for projected resource needs in 67 low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(9):e875–e887. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30263-2.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Step by step—evaluating violence and injury prevention policies: brief 3: evaluating policy content. 2013 [ accessed 2020 Feb 25]. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/pdfs/policy/Brief%203-a.pdf.

- Collins T. Health policy analysis: a simple tool for policy makers. Public Health. 2005;119(3):192–96. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2004.03.006.

- Giedion U, Tristao I, Bitran RA, Cañón O. Making the implicit explicit: an analysis of seven health benefit plans in Latin America. In: Giedion U, Bitran RA, Tristao I, editors. Health benefit plans in Latin America: a regional comparison, Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank, p. 10-37; 2014 [accessed 2020 Feb 24]. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Health-Benefit-Plans-in-Latin-America-A-Regional-Comparison.pdf.

- Ulmer C, McFadden B, Cacace C. Perspectives on essential health benefits: workshop report. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. p. 13182. doi:10.17226/13182.

- Global Health Cluster. Working paper on the use of essential packages of health services in protracted emergencies. 2018 Feb [accessed 2020 Feb 24]. https://www.who.int/health-cluster/about/work/task-teams/EPHS-working-paper.pdf?ua=1

- Bendavid E, Ottersen T, Peilong L, et al. Chapter 16. Development assistance for health. In: Nugent R, Padian N, Rottingen JA, Schäferhoff, M, et al., editors. Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd Jamison, DT, Gelband, H, Horton, S, Jha, P, Laxminarayan, R, Mock, CN, and Nugent, R ed., Washington (DC): World Bank, p. 299-313; 2017. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0527-1.

- IHME. Financing global health 2019: tracking health spending in a time of crisis. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2020 [accessed 2020 Mar 26]. http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/FGH/2020/FGH_2019_Interior_Final_Online_2020.09.18.pdf

- Spicer N, Agyepong I, Ottersen T, Jahn A, Ooms G. ‘It’s far too complicated’: why fragmentation persists in global health. Glob Health. 2020;16(1):60. doi:10.1186/s12992-020-00592-1.

- Bhutta ZA, Sommerfeld J, Lassi ZS, Salam RA, Das JK. Global burden, distribution, and interventions for infectious diseases of poverty. Infect Dis Poverty. 2014;3(1):21. doi:10.1186/2049-9957-3-21.

- Chang AY, Cowling K, Micah AE, Chapin A, Chen CS, Ikilezi G, Sadat N, Tsakalos G, Wu J, Younker T, et al. Past, present, and future of global health financing: a review of development assistance, government, out-of-pocket, and other private spending on health for 195 countries, 1995–2050. Lancet. 2019;393(10187):2233–60. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30841-4.

- Murray CJL, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Ozgoren, AA, Abd-Allah, F, Abera, SF, Aboyans, V, Abraham, JP, Abubakar, I, Abu-Raddad, LJ et al, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145–91. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X.

- Connor SR, Sepulveda Bermedo MC, World Health Organization, World Palliative Care Alliance. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance; 2014 [ accessed 2020 Nov 29]. http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf.

Appendix

Table A1. List of countries’ essential packages of health services reviewed in analysis. All documents can be found here

Table A2. List of interventions within DCP3 POIs at the primary health care level in the HPP