?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

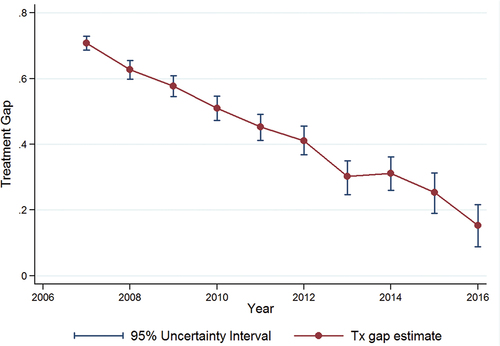

As Mexico’s government restructures the health system, a comprehensive assessment of Seguro Popular’s Fund for Protection against Catastrophic Expenses (FPGC) can help inform decision makers to improve breast cancer outcomes and health system performance. This study aimed to estimate the treatment gap for breast cancer patients treated under FPGC and assess changes in this gap between 2007 (when coverage started for breast cancer treatment) and 2016. We used a nationwide administrative claims database for patients whose breast cancer treatment was financed by FPGC in this period (56,847 women), Global Burden of Disease breast cancer incidence estimates, and other databases to estimate the population not covered by social security. We compared the observed number of patients who received treatment under FPGC to the expected number of breast cancer cases among women not covered by social security to estimate the treatment gap. Nationwide, the treatment gap was reduced by more than half: from 0.71, 95% CI (0.69, 0.73) in 2007 to 0.15, 95%CI (0.09, 0.22) in 2016. Reductions were observed across all states . This is the first study to assess the treatment gap for breast cancer patients covered under Seguro Popular. Expanded financing through FPGC sharply increased access to treatment for breast cancer. This was an important step toward improving breast cancer care, but high mortality remains a problem in Mexico. Increased access to treatment needs to be coupled with effective interventions to assure earlier cancer diagnosis and earlier initiation of high-quality treatment.

Introduction

As in other middle-income countries, in Mexico breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality in women.Citation1 Breast cancer is a high priority in Mexico’s health policy agenda, with legally binding guidelines to promote early detection,Citation2 a national policy providing financing for treatment for the population without social security (2007–2019), and a Breast Cancer National Program aimed at reducing mortality. Yet, breast cancer incidence and mortality in Mexico in 2020 were on the rise.Citation1,Citation3 Mortality rates increased from 6.9 per 100,000 Mexican women in 2000 to 9.9 per 100,000 in 2020,Citation1 and age-standardized Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) rates likely increased 12.1% between 1990 and 2013, from 283.4 to 319.2 DALYs per 100,000 women.Citation4

The Mexican health system is fragmented in three main sectors: (1) several social security institutions that provide health services for employees and families of private companies through IMSS (Instituto Mexicano de Seguro Social) and for those of federal and state government organizations through ISSSTE (Instituto de Seguridad y Servicios Sociales de los Trabajadores del Estado) and other smaller institutions, (2) Ministry of Health (MoH) facilities at the federal and state levels that are mostly used by the population without social security, and (3) private sector facilities (including hospitals and pharmacies) that are used by a small population with private health insurance, but also frequently by the rest of the population (including people with and without social security) who pay out of pocket.Citation5,Citation6

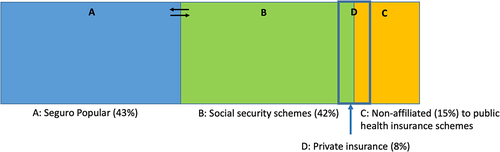

In 2004, Mexico implemented a voluntary insurance scheme known as Seguro Popular, for people not covered by social security institutions, that provided financing for its affiliates to receive coverage from an explicit list of health interventions (mainly prevention and health promotion services, emergencies, general surgery and obstetrics) plus treatment for high-cost diseases paid through a special fund, the FPGC (Fund for Protection against Catastrophic Expenses).Citation7 By 2018, 43% of the Mexican population was covered by Seguro Popular, 42% was covered by several social security schemes, and 15% of the population was not affiliated with either Seguro Popular or social security ().Citation6

Figure 1. Health insurance coverage in Mexico in 2018.

In 2007 FPGC began covering breast cancer treatment for people not covered by social security.Citation8 Once the diagnosis of breast cancer was confirmed through a biopsy, people could receive FPGC financing for treatment at an accredited facility.Citation9 The breast imaging tests for diagnosis and the biopsy were not covered by FPGC and had to be paid out of pocket. Treatment for breast cancer was provided mostly at public facilities under the Ministry of Health at state and federal levels, but also at some private centers (mostly nonprofit).

A treatment gap is defined as the number of people with a condition or disease who need treatment for it but who do not receive it.Citation10 Most studies that estimate treatment gaps have focused on mental health and epilepsy treatment.Citation10–12 However, there is a dearth worldwide of studies that estimate cancer treatment gaps. Additionally, there is no published report analyzing FPGC’s coverage of breast cancer treatment in Mexico. Seguro Popular and its FPGC were eliminated in 2019,Citation13,Citation14 and replaced by INSABI (Instituto Nacional de Salud y Bienestar).Citation15 As Mexico’s national government is currently restructuring the health system (with a focus on the Ministry of Health), an assessment of the FPGC mechanism and its consequences can help decision-makers in improving the performance of Mexico’s health system, especially the operations of INSABI, which is supposed to provide free healthcare services for all citizens. For breast cancer, this commitment includes the provision of publicly funded treatment and also diagnostic tests.

This study is the first to assess treatment gaps for breast cancer in Mexican women, by comparing data on treatments financed under FPGC with estimates of expected breast cancer cases. The main objectives were to: (1) estimate the treatment gap for breast cancer financed by FPGC between 2007 and 2016, both nationally and by state, and (2) determine whether there were changes in these gaps over time.

Materials and Methods

Design

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using nationwide administrative claims data for patients whose breast cancer treatment was financed by FPGC between 2007 and 2016, and estimated breast cancer incidence for the same period.

Data Sources and Estimations

Treated Breast Cancer Cases

To ascertain the number of treated breast cancer cases by age-group, as well as patient covariates, we used administrative claims data collected by FPGC between 2007 and 2016. This database provided nationwide comprehensive breast cancer reimbursement data. Claims were submitted by accredited treatment facilities in order to be reimbursed by the FPGC, therefore it is very unlikely that any covered cases would be missing from this database or that uncovered cases would be included. Prior to 2011, there was one reimbursement claim per patient and one bundled payment per case. After 2011, the reimbursement method changed to fee-for-service, with multiple claims (observations) per individual patient. There were 268,703 claims in the database corresponding to 60,846 reimbursed breast cancer cases. We excluded 1,815 recurrent or persistent cancer cases, 1,731 for whom staging information was missing, 328 male patients, 84 with implausible dates of treatment, 27 with a sarcoma diagnosis, and 14 with missing identifier information. We included 56,847 patients in the analysis.

The descriptive variables for treated patients in the FPGC database include: the patient’s age, state of residence, state where the cancer center of care is located, and the type of FPGC accredited cancer center where the patient received treatment (public or private). The cancer clinical stage at treatment start was categorized as 0 (in situ), early-stage (I–IIA), locally-advanced (IIB-IIIC), and metastatic (IV) disease.

Women without Social Security

To estimate the number of women without social security we obtained data on the type of health insurance affiliation from: the National Censuses of 2000Citation16 and 2010,Citation17 the Intercensal Survey of 2015,Citation18 and the National Surveys of Health and Nutrition (ENSANUT is the acronym in Spanish) of 2006.Citation19 and 2012Citation20 We used Stata’s survey function to estimate the proportion of women without social security by year (between 2007 and 2016), state, and age group. To do so, we fitted 608 ordinary least square models with exponential links (32 states and 19 age-groups), with the form shown in Equationequation [1](1)

(1) .

Where represents the probability of a woman not being covered by social security (d) in the year t, for age group e in the k-th state. The log-link was chosen because it avoided the possibility of negative probability estimates. This modeling strategy was chosen, rather than alternative strategies such as linear interpolation, because it smooths out random variation in the point estimates, and allows for more than one data source for each state, year, and age group. Once the models were fitted, we obtained the predicted proportions of women without social security, for each age group, state, and year. In response to comments from a reviewer, we re-estimated these proportions using multilevel modeling and found similar results. The proportions estimated with both methods showed a Pearson’s correlation of 0.997, thereby confirming the robustness of our initial analysis. Finally, to obtain the number of women without social security, we multiplied CONAPO’s (Consejo Nacional de Población) annual estimations of population in each state and age group by the proportions of women without social security we estimated by Equationequation [1]

(1)

(1) .

Expected Breast Cancer Cases

To estimate breast cancer expected incidence we used breast cancer incidence estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) for Mexico for the years 2007 to 2016, which are stratified by state and age group.Citation21 We obtained the expected number of breast cancer cases among women in each state and age group by multiplying the GBD Incidence Rates by the estimated number of women without social security (from the above described procedure) in each strata. The number of expected cases for each state was obtained by adding across all age-groups.

Treatment Gap

We defined treatment gap for breast cancer as the proportion of expected breast cancer cases among the at-risk population without social security who did NOT receive breast cancer treatment financed by FPGC. We defined the population at risk to be women over 15 years of age to match with the GBD database’s age group classification. We operationalized the treatment gap as 1 minus the estimated proportion of treated population. The treatment proportion was estimated by the ratio of the breast cancer cases financed by FPGC between 2007 and 2016 to the expected breast cancer incident cases between 2007 and 2016 among women aged 15 and more who would have been eligible for breast cancer treatment financing by the FPGC in that period, as shown in EquationEquation [2(2)

(2) ].

We estimated the yearly treatment gaps nationally and per state of residence. Patients living in each state could have received cancer care financed by FPGC either in their state of residence or in another state. FPGC was intended to expand access nationally. Patients could get care in any accredited facility. Therefore, our state-specific treatment gap calculations include all patients living in each state regardless of where they received cancer treatment. For patients whose information on the state of residence was missing in the FPGC database (3521, 6.2%), we assumed that they lived in the state where they received care.

Data Analysis

We described categorical sociodemographic and clinical variables in the FPGC claims database with frequencies and percentages. For the patients’ age we estimated median and interquartile range. We estimated the yearly treatment gaps nationally and for each state. For states where the treatment gap estimate was negative, we assigned it a value of 0. We estimated uncertainty intervals for the yearly treatment gaps by assessing uncertainty present in both the GBD Incidence Rate and the estimates of population without social security. This was done by means of repeating the following procedure one-thousand times. In each iteration, for each state and age group stratum, instead of using the point estimate for the GBD Incidence Rate, we used the natural exponential of a randomly drawn number from a normally distributed variable with mean equal to the natural logarithm of the point estimate, and a variance that was inferred by taking the logarithm of the upper and lower limits of the 95% uncertainty interval reported by the GBD. At the same time, in each of the iterations, we used a randomly chosen number from a normal distribution with mean equal to the point estimate of the non-insured population, and variance equal to npq where n is the total population of women in the stratum (as estimated by CONAPO), p is the estimated proportion of un-insured women for the stratum, and q is 1-p. Finally, we defined the uncertainty interval by taking the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the distribution of the 1,000 treatment gap estimates by the above procedure.

Results

We included 56,847 breast cancer patients who received treatment at 63 hospitals accredited by FPGC between 2007 and 2016. The patients’ characteristics are presented in . The majority were younger than 62 years of age (75%), had locally advanced or metastatic disease (64.6%), lived in Mexico City (15.2%), Estado de Mexico (11.1%) and Jalisco (7.9%), and received treatment in their state of residence (71.4%) at public hospitals (85.1%).

Table 1. Breast cancer patients covered by Seguro Popular (FPGC) 2007–2016 (n = 56,847).

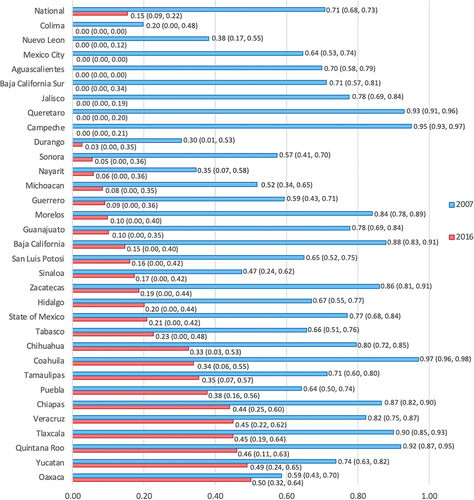

Our analysis shows that the treatment gap declined at the national level from 0.71 (0.69, 0.73) in 2007, when breast cancer treatment started being covered by FPGC, to 0.15 (0.09, 0.22) in 2016 (). The treatment gap for all states with an accredited treatment center showed a declining trend over time, although the magnitude of these decreases differed among states (). The treatment gap was reduced to zero for 8 out of the 32 (25%) states, and in 6 of these 8 states there were negative treatment gaps. For most states these reductions in treatment gaps were due to increased access to treatment within the same state. In 18/32 states more than 90% of patients received treatment in the state where they lived (Supplementary Table 3). In another 9/32 states, between 68% and 89% cases were treated in their state of residence, but between 5% and 20% were treated in a neighbor state with a large cancer center. In the cases of the State of Mexico, Morelos and Hidalgo, between 70% and 80% of women living in these states received care in the neighbor state of Mexico City. Thus, the observed reduction in treatment gaps for these three states were mainly driven by the increased supply of cancer services in Mexico City. Supplementary Table 1 shows yearly estimates of the treatment gap and the uncertainty interval, nationally and by state, obtained using the proportions of women without social security estimated by ordinary least squares modeling. Supplementary Table 4 shows the yearly estimates of the treatment gap using the proportions of women without social security we obtained by multilevel modeling. Supplementary Table 2 shows our estimations of expected breast cancer cases and covered cases for each year and the 32 states.

Figure 2. Yearly nationwide treatment gap between 2007 and 2016.

Figure 3. Treatment gap reduction from to 2007 to 2016 by state.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess the treatment gap for breast cancer patients who were candidates for financial coverage by Seguro Popular (FPGC) in Mexico. Nationwide, the treatment gap for this population was reduced by more than half between 2007 and 2016. This reduction occurred through a sharp expansion in breast cancer treatment access for women without social security and covered by FPGC during the ten years analyzed. Reductions in the treatment gap were observed across all states with accredited cancer centers, although the magnitudes varied.

Our estimates of the treatment gap should not be interpreted to mean that 70% of breast cancer patients among the uninsured population did not receive any treatment before Seguro Popular’s FPGC began covering breast cancer in 2007. Before coverage of breast cancer treatment was implemented under FPGC, people without social security coverage could receive breast cancer treatment at federal and state hospitals by paying fees out-of-pocket (determined by each hospital) according to patient socioeconomic status. Although there are no systematic data to compare treatment adherence before and after the FPGC was launched, a few reports attribute improved survival rates for some patients under FPGC to enhanced access, lower patient out-of-pocket costs, and better patient adherence to standard multimodal treatment.Citation22,Citation23

Treatment gaps for breast cancer among women without social security came close to zero in 8 out of 32 states. The negative figures that we observed in 6 out of these 8 states could suggest over-provision of breast cancer treatment in those states. This over-provision could be due to the inclusion of patients from different states (especially in states with the largest cancer centers like Mexico City, Jalisco and Nuevo León) and also the inclusion of patients with social security seeking treatment under Seguro Popular at a FPGC-reimbursed institution (which can be considered a form of leakage). An analysis of Seguro Popular in 2018 identified 3 million duplicate affiliations with IMSS (the largest social security institution in Mexico).Citation8 Patients insured by social security in Mexico often face long waiting times for appointments and for access to certain treatments, and some patients therefore decide to use other types of health care services (such as the private sector or Ministry of Health facilities).Citation24

This study has some limitations. First, our treatment gap estimations rely on GBD incidence estimates because Mexico does not have cancer registry incidence data. Even though GLOBOCAN is recognized as providing the best cancer incidence estimates worldwide, it does not offer estimates in sub-national units (states in Mexico).Citation1 The national breast cancer incidence estimates for Mexico provided by GLOBOCAN and GBD are very similar. Therefore we decided to use the state-stratified incidence estimates provided by GBD. We assumed that incidence estimates incorporate undiagnosed positive cases, including patients who did not seek care and those who did not have access to (or could not pay for) diagnostic tests (which required out-of-pocket payment by patients). Second, the treatment gap could be underestimated as the program expanded due to the inclusion of patients covered by social security who sought and received breast cancer treatment under Seguro Popular at a FPGC-reimbursed institution. We do not know how many patients covered by social security received treatment financed by FPGC (as a form of leakage). The population without social security is difficult to determine because it is a dynamic population, and people move in and out of formal sector employment and related social security schemes,Citation6 and a single family could have access to multiple insurance schemes due to the employment status of different family members. In addition, Mexico did not have adequate information systems to determine the social insurance status of people seeking care under FPGC, especially in the early years of the program. A third limitation is that we do not have indicators on the timeliness, quality of treatment provided, and completion of treatment. The treatment gap reductions that we estimated only reflect an increase in initial access to breast cancer treatment. A final limitation concerns our selected statistical model for estimation of the proportions of women without social security, which could be subject to misspecification. However, in response to reviewers’ comments, we repeated the analyses with a multilevel model and found the results to be robust.

The dearth of studies that provide estimations of the treatment gap for cancer patients in the international literature is probably due to difficulties inherent in estimating cancer incidence and prevalence as well as the number of treated cases in countries that lack cancer registries and/or administrative data collection that is comparable across different health service providers. The present study was possible due to the unique opportunity of having access to administrative data that were systematically collected for cancer patients treated at all FPGC-accredited institutions for treatment financed by the program.

As Mexico’s government restructures the health systemCitation13 there are important lessons to be learned from the experience of the FPGC financing mechanism for breast cancer treatment. Previous studies have shown that breast cancer survival rates by clinical stage of patients treated under the FPGC were comparable to international standards.Citation22,Citation25 This is largely because the interventions and medications covered by FPGC followed standard international recommendations. Nevertheless, most breast cancer patients covered by this program started treatment at advanced stages (55% with locally advanced cancers and 10% with metastatic cancers). Further analysis of the clinical stage at treatment across time of implementation of the FPGC will be reported in a separate publication, but preliminary findings show that the survival rates and distribution of cancer stage at presentation remained unchanged throughout a decade of treatment financing by the FPGC.Citation26 This reveals the importance of coupling programs to enhance access to cancer treatment (number of cases treated) with interventions that improve early cancer diagnosis and treatment start (quality of treatment). To improve Mexico’s breast cancer survival rates, reduce increasing mortality rates and improve patients’ quality of life while assuring good investment of public finances, policies need to be revised to incorporate explicit mechanisms to improve quality of care, expand access for early diagnosis, and expedite referral of patients.

In 2019 the Mexican government eliminated Seguro Popular (and the related FPGC) and declared that the population without social security was entitled to use MoH healthcare facilities for all kinds of treatment without spending out-of-pocket.Citation15 Three years into this national administration, there is still substantial uncertainty about how the government will finance and deliver all health care services for the entire population.Citation14 Thus far, the national government has canceled funding for breast cancer treatment for all private facilities (including nonprofit organizations) that previously received public funds from FPGC,Citation13 and there are reliable reports of patient treatment interruptions and delays due to chemotherapeutic drug shortages and budget shortfalls at government hospitals.Citation27

Conclusion

This study shows that access to breast cancer treatment in Mexico increased substantially under Seguro Popular (FPGC) between 2007 and 2016. This was an important step toward improving breast cancer care, but high mortality remains a significant problem in Mexico. Increased access to treatment needs to be coupled with effective interventions to assure earlier cancer diagnosis and earlier initiation of high-quality treatment.

Additionally, the study shows the importance of data collection and analysis for monitoring quality and evaluating the impacts of health policies and programs. Governments that introduce health reforms have a moral obligation to assure data collection that allows the evaluation of impacts on access to treatment and on ultimate health outcomes. This study demonstrates how treatment claims data can be used to assess the different impacts of a program, in this case Seguro Popular’s FPGC positive impact on access to breast cancer treatment in Mexico. It also raises questions about how that assessment can be continued in evaluating the impacts of INSABI’s actions on access to diagnosis and treatment for Mexican women with breast cancer.

Author Contributions

KU, ML and MR conceived the study. KU, MR, ML and HL designed the study. KU, HL, AC, PE and ES contributed to data management and statistical analysis. KU and MR drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mexico’s National Cancer Institute (number 2021/076).

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the CNPSS (Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud). These data were used under license for the study. Therefore, restrictions apply to the availability of the data. Data are available from the authors with the permission of the CNPSS.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (57.7 KB)Supplementary Material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2022.2064794.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Global Cancer Observatory https://gco.iarc.fr/ Accessed 01 Feb 2022. Lyon, France: GLOBOCAN Database, IARC (International Agency for Research in Cancer); 2020.

- NOM 041-SSA2-2011: norma Oficial Mexicana para la prevención, diagnóstico, tratamiento, control y vigilancia epidemiológica del cáncer de mama. Secretaría de Salud, México 2011. Available online: http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5194157&fecha=09/06/2011 Accessed 01 Feb 2022.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global burden of disease study 2019 (GBD 2019) results. Seattle (United States): Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME; 2020.

- Gomez-Dantes H, Fullman N, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Cahuana-Hurtado L, Darney B, Avila-Burgos L, Correa-Rotter R, Rivera JA, Barquera S, Gonzalez-Pier E, et al. Dissonant health transition in the states of Mexico, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet. 2016;388(10058):2386–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31773-1.

- Gomez Dantes O, Sesma S, Becerril VM, Knaul FM, Arreola H, Frenk J. The health system of Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2011; 53(Suppl 2): s220–232. https://saludpublica.mx/index.php/spm/article/view/5043/10023.

- González Block MA, Reyes Morales H, Cahuana Hurtado L, Balandrán A, Méndez E, Allin S. Mexico: health system review. Health Systems in Transition. 2020;22:i–222.

- Aracena-Genao B, Gonzalez-Robledo MC, Gonzalez-Robledo LM, Palacio-Mejia LS, Nigenda-Lopez G. Fund for protection against catastrophic expenses. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53(Suppl 4):407–15. doi:10.1590/s0036-36342011001000004.

- Chemor Ruiz A, Ratsch AEO, Alamilla Martinez GA. Mexico’s Seguro Popular: achievements and challenges. Health Syst Reform. 2018;4(3):194–202. doi:10.1080/23288604.2018.1488505.

- Catálogo Universal de Servicios de Salud. 2018. Anexo I: intervenciones del Fondo de Protección contra Gastos Catastróficos. Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Protección en Salud http://www.documentos.seguro-popular.gob.mx/dgss/CAUSES_2018c.pdf Accessed 01 Feb 2022.

- Kale R. The treatment gap. Epilepsia. 2002;43(Suppl 6):31–33. doi:10.1046/j.1528-1157.43.s.6.13.x.

- Kohn R, Ali AA, Puac-Polanco V, Figueroa C, Lopez-Soto V, Morgan K, Saldivia S, Vicente B. Mental health in the Americas: an overview of the treatment gap. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2018;42:e165. doi:10.26633/RPSP.2018.165. PMC6386160.

- Evans-Lacko S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, Florescu S, de Girolamo G, Gureje O, et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1560–71. doi:10.1017/S0033291717003336. PMC6878971.

- Reich MR. Restructuring health reform, Mexican style. Health Syst Reform. 2020;6(1):1–11. doi:10.1080/23288604.2020.1763114.

- Agren D. Farewell Seguro Popular. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):549–50. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30408-6.

- Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar, Gobierno de México. ( Cited 2021May16) Available at: https://www.gob.mx/insabi/que-hacemos.

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda 2000, México [ cited 2021 May 2]. Available from: https://inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2000/.

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010, México [ cited 2021 May 2]. Available from: https://inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2010/.

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). Encuesta Intercensal 2015, México (cited 2021 May 2). Available from: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/intercensal/2015/.

- ENSANUT (Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición) 2006. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, México. [Cited 2021 May 2]. Available from: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2006/descargas.php.

- ENSANUT (Encuesta Nacional de Salud y Nutrición) 2012. Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, México. [Cited 2021 May 2]. Available from: https://ensanut.insp.mx/encuestas/ensanut2012/descargas.php.

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global burden of disease study 2017 (GBD 2017) results. Seattle (United States): Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2018. (cited 2021 May 3) Available from http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

- Reynoso-Noveron N, Villarreal-Garza C, Soto-perez-de-celis E, Arce-Salinas C, Matus-Santos J, Ramirez-Ugalde MT, Alvarado-Miranda A, Cabrera-Galeana P, Meneses-Garcia A, Lara-Medina F, et al. Clinical and Epidemiological profile of breast cancer in Mexico: results of the Seguro Popular. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(6):757–64. doi:10.1200/JGO.2016.007377. PMC5735969.

- Lozano R, Garrido F. Improving health system efficiency: Mexico. Catastrophic health expenditure fund https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/186476 . . 2015 (Geneva: World Health Organization) Accessed 2 May 2021 Health Systems Governance and Funding

- Unger-Saldana K, Ventosa-Santaularia D, Miranda A, Verduzco-Bustos G. Barriers and explanatory mechanisms of delays in the patient and diagnosis intervals of care for breast cancer in Mexico. Oncologist. 2018;23(4):440–53. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0431. PMC5896704.

- Huerta-Gutierrez R, Lajous M, Zamora-Muñoz S, Hernández-Ávila JE, Mohar A, Muñoz-Aguirre P. Breast cancer survival disparities in Mexican women under a comprehensive health reform. JCO Global Oncology. 2020;6(Supplement_1):67–67. doi:10.1200/go.20.64000.

- Bandala-Jacques A, Huerta-Gutierrez R, Muñoz SZ, Cabrera P, Mohar A, Lajous M. Abstract 47: survival of breast cancer in women treated under Mexico’s Seguro Popular. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarker and Prev. 2021;30(7_Supplement):47–47. doi:10.1158/1538-7755.ASGCR21-47.

- Villarreal-Garza C, Aranda-Gutierrez A, Ferrigno AS, Platas A, Aloi-Timeus I, Mesa-Chavez F, Ayensa-Alonso A, Platas A. The challenges of breast cancer care in Mexico during health-care reforms and COVID-19. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(2):170–71. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30609-4. PMC8080161.