ABSTRACT

Colombia provides a unique setting to understand the complicated interaction between health systems, health insurance, migrant populations, and COVID-19 due to its system of Universal Health Coverage and its hosting of the second-largest population of displaced persons globally, including approximately 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants. We surveyed 8,130 Venezuelan migrants and Colombian nationals across 60 municipalities using a telephone survey during the first wave of the pandemic (September through November 2020). Using self-reported enrollment in one of the several Colombian health insurance schemes, we analyzed the access to and disparities in the use of health-care services for both Colombians and Venezuelan migrants by insurance status, including access to formal health services, virtual visits, and COVID-19 testing for both groups. We found that compared with 3.6% of Colombians, 73.6% of Venezuelan telephone survey respondents remain uninsured, despite existing policies that allow legally present migrants to enroll in national health insurance schemes. Enrolling migrants in either the subsidized or contributory regime increases their access to health-care services, and equality between Colombians and Venezuelans within the same insurance schemes can be achieved for some services. Colombia’s experience integrating Venezuelan migrants into their current health system through various insurance schemes during the first wave of their COVID-19 pandemic shows that access and equality can be achieved, although there continue to be challenges.

Introduction

Providing health-care services for displaced populations is challenging in all health-care systems, complicated further by the current COVID-19 pandemic, which continues to have a profound impact on health systems globally.Citation1–4 The strain on health systems put forward by COVID-19 has been even more acute in many countries grappling with the presence and acute needs of vulnerable migrant and non-citizen populations. At the same time, the need to provide services to these populations is increasing as the number of displaced populations has continued to rise globally. Since the 1990s, the number of migrants has grown by more than 50%, with an estimated 281 million migrants globally in 2020.Citation5 This movement of populations due to various political, social, economic, and environmental reasons has especially impacted developing countries and urban areas. Approximately 85% of forcibly displaced populations worldwide now live in developing regions, and within these, the majority of migrants live in urban settings.Citation6

There are multiple ways for health systems to provide services to non-citizen, migrant, or internally displaced populations. Some countries set up parallel systems (refugee camps or separate health facilities),Citation7,Citation8 while other countries allow migrants and/or non-citizens to utilize the same health-care facilities as the host population.Citation9 Countries may also utilize multiple mechanisms to provide health-care services to these populations.Citation10 Colombia provides an example of a country that has attempted to integrate Venezuelan migrants into its current system, utilizing its system of health insurance that has been developed as part of efforts to achieve Universal Health Coverage.

Using results from a telephone survey of 8,130 Colombians and Venezuelans residing in Colombia, this paper examines levels of integration and health-care utilization of migrant populations within the Colombian health system during the first wave in Colombia, which took place from March to November 2020. Colombia provides a unique opportunity for an analysis of the response to COVID-19 among vulnerable populations, given the history of cross-border migrations from Venezuela combined with Colombia’s expansion of Universal Health Coverage for all populations, citizens, and non-citizens alike, for a number of years. Today, the Colombian health system faces the additional strain of caring for the more than 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants currently residing within Colombian borders—the world’s second highest share of displaced persons residing in a host country, only after Turkey, and the largest refugee crisis in Latin American history.Citation11–13 Venezuelan migrants now make up approximately 3% of Colombia’s population and the number of migrants continues to rise.Citation14

The complex political, demographic, and health system context in Colombia, together with data collected throughout the pandemic on use of the health-care system by insurance type for both Colombians and Venezuelans make the results reported in this manuscript extremely relevant to inform the ongoing COVID-19 response for health systems globally and, especially, for systems with large migrant populations. To date, there remains limited research on health systems’ ability to integrate migrant needs—Citation15 made even more urgent by the COVID-19 epidemic.Citation11,Citation16 This study aims to address this gap, as one of the few studies collecting telephone survey data to assess individuals’ first-hand experiences with accessing health-care services during the COVID-19 pandemic in a country with a large migrant population.

Migrant Policy and Access to Health Care Services Globally

Like Colombia, many countries have migrant populations, and each country has its own regulations and policies on access to health-care services for migrant and non-citizen populations. These regulations and policies depend on whether the migrants and/or non-citizens are eligible to utilize the same health-care facilities as the host population or if there are parallel systems of services (refugee camps or separate health facilities). In places like Colombia, integration of migrants into the standard health system often has its own administrative and other challenges. In the United States, for example, access to health-care services varies considerably depending on which state one resides in, with states having differing policies on eligibility for several public programs (SNAP, TANF, and Medicaid and/or CHIP).Citation9 As of 2016, out of all states and federal territories (50 states and Washington DC), only 30 states offered public health insurance coverage for lawfully present immigrant children during their first five years in the country, and only seven states provided public health insurance coverage to adults during the same time period.Citation17 Other countries with large migrant populations also offer limited access to formal services and unaffordability of health services remains a substantial barrier for accessing care for migrants.Citation15 Jordan, for instance, offers health-care services for refugees both through camps and through the Jordanian health-care system. Hosting more than 700,000 refugees and asylees—mainly from Syria—Jordan requires refugees residing outside of camps to pay for health services out-of-pocket at the same rate as uninsured Jordanians, after presenting documentation of their legal status.Citation10 This follows a roll-back of free public health services provided to all refugees in Jordan prior to 2014.Citation18 In Bangladesh, the government provides free curative care to all registered refugees in official camps; however, these services have been deemed insufficient to cover the entire population, address the poor health and hygienic conditions within the camps,Citation7,Citation8 and have also not reached the more than 200,000 refugees estimated to have settled outside the camps in unofficial settlements.Citation19,Citation20 Due to differing health systems, populations, and culture and history, no one policy on health-care access for migrant and non-citizen populations can be applied to all countries.

History of Cross-Border Migration in Colombia

While nations around the world have been increasingly restricting the entry of new migrants, Colombia sets a more positive example in terms of migration policy, winning praise from humanitarian institutions in recent years.Citation14 The Colombian government has acknowledged the challenges of the Venezuelan crisis—which has caused a steady stream of migrants into the country since 2016—as well as a culture of reciprocity between the two countries, due to Venezuela’s role in hosting Colombian citizens during the nation’s own political crises during the 1980s and 1990s.Citation21 During the 1950s to 1970s, Venezuela enjoyed a period of economic growth and income equality, with a strong public health and education system, offering free public services to all residents of the country.Citation22,Citation23 This drew many Colombian citizens to the country for economic reasons, in addition to a large number of displaced persons—often the rural poor—due to internal conflict in Colombia.Citation14 However, falling oil prices since 2008, along with subsequent economic and political mismanagement, resulted in a grave social and political crisis characterized by hyperinflation, shortages of food and medicines, and an increase in crime and homicide rates.Citation23 It is important to note that the resulting Venezuelan emigration, starting as early as 2016, is larger than just the migrants entering Colombia. According to a recent Brookings Report, as of 2019 there were 4.6 million Venezuelan migrants globally and this was predicted to grow to 6.5 million by 2020.Citation24 This means that between 28% and 39% of all Venezuelan migrants reside in Colombia. While these numbers highlight the broader context of the Venezuelan migrant crisis for not only Colombia, but also in the rest of Latin America and the Caribbean, the focus of this paper will be the integration of Venezuelan migrants into the Colombian health-care system.

Venezuelan Migrants and the Colombian Health Care System

Colombia’s health system has been moving effectively toward Universal Health Coverage since 1993, when the country enacted Law 100,Citation25 establishing a mandatory health insurance model.Citation26,Citation27 As a result, the National Health System adapted to expand options of insurance through public and private Health Promoting Entities (EPS), which were to offer a standardized health benefits package to insured individuals and maximize quality and efficiency by controlling service provision costs through contracts with Health-care Provider Institutions (IPS). Expanded coverage was achieved by offering two main co-existing insurance schemes. On the one hand, the contributory scheme (EPS-C) was co-financed by contributions from employers (68%) and employees (32%) with a formal labor contract. On the other hand, the subsidized scheme (EPS-S) covered vulnerable populations and those that did not participate in the formal workforce (unemployed or informal workers), and was financed by the national government through national and local tax revenues as well as with contributions from the contributory regime.Citation25 There are also special regimes for insuring members of the armed forces, national police, and teachers at public schools and universities, which are financed through income tax and private mechanisms.Citation25 However, these amount to less than 5% of the insured population.Citation28 Today, these systems of health insurance together provide insurance to approximately 97.8% of the Colombian population (approximately 50 million).Citation28

In an effort to expand access to formal health insurance for non-citizens in Colombia, in 2017, the Colombian government developed a temporary permit for residence—the Special Permit of Permanence (PEP)—to allow temporary legal residence and access to public services for the increasing number of Venezuelan migrants entering the country. At the time, PEP allowed migrants up to 90 days of residence that could be extended up to 24 months. Migrants enrolled in PEP were also granted access to enroll in either EPS health insurance schemes, depending on their employment status. However, less than half of all Venezuelan migrants have actually enrolled in PEP, and hence less than half have health insurance.Citation29 Those who have remained unregularized, or without PEP, have been classified as “non-affiliated” and only have access to emergency health- care when the visit is deemed life-threatening or special health prevention services, such as vaccination campaigns.Citation29,Citation30 In some rare cases, migrants with special vulnerability, such as children and those with life threatening conditions, have filed petitions (“tutelas”) with local courts to be granted broader protections, drawing upon Colombia’s Constitutional Court’s recognition of the need for special protection by those with specific vulnerability. However, these cases are decided upon a case-by-case basis.Citation31–33

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the pressure on the Colombian health system, the government of Colombia initially announced in late 2020 that only regularized Venezuelan migrants would have access to the COVID-19 vaccine as it became available.Citation34 As it became apparent that vaccines would become more accessible, the Colombian government subsequently pledged to provide vaccines to everyone regardless of their status. In addition, on February 8, 2021, the government also announced a new regularization process, the Estatuto Temporal de Protección para Migrantes Venezolanos (ETPMV), that would allow the approximately 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants currently residing in Colombia the ability to obtain a 10-year temporary permit for residence. This policy should, over time, give these migrants the legal right to formal employment, access to education, social protection networks, and health insurance. This change, especially access to formal health insurance, should facilitate access to health-care—including COVID-19 vaccines—to many additional migrants.Citation35 As of May 2021, 383,000 Venezuelans were registered to begin the ETPMV process.Citation36

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

Telephone surveys were conducted with individuals across 60 municipalities in Colombia, for a total of 8,130 respondents. The study’s sample of municipalities were the 60 municipalities with the largest population of Venezuelan migrants, summing approximately 82% of the total Venezuelan population living in Colombia. For each municipality, approximately 70 Venezuelans and 50 Colombians were recruited and invited to respond to the telephone survey to achieve sufficiently narrow 95% confidence intervals on individual questions and indices combining several questions. Surveys were carried out by an experienced Colombian survey research firm. A telephone survey was utilized in place of in-person interviews due to COVID-19 restrictions. Surveys were carried out from September through November 2020, during the first wave of the pandemic in Colombia, and prior to the ETPMV announcement by the Colombian government and roll out of COVID-19 vaccinations, which both took place from February of 2021.

The telephone survey (Supplementary Materials) was developed in English and then translated to Spanish. The content of the survey was validated and adapted to the local context by a team of experts who made up the study consortium, including experts from Brandeis University, University of Los Andes, and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Surveys were piloted with respondents who were not part of the final sample. The final survey comprised 68 mostly multiple-choice questions and took an average of 25 minutes to complete. Using snowball sampling methods, the survey captured information from both Colombian citizens and Venezuelan migrants within each sampled municipality on demographics as well as health insurance status, work/economic activity, knowledge of COVID-19, adherence to public health and social distancing measures, symptoms of COVID-19, and access to and payment of health-care services during COVID-19. Questions for this survey were either created by the authors or based on questions from previously developed surveys.Citation37–39 For effective recruitment, each respondent was given mobile airtime compensation of 3 USD for their own response, plus 1 USD for a referred contact’s response.

Inclusion criteria for participation in the survey were selected to ensure comparability between Colombian and Venezuelan respondents. The inclusion criteria for Colombian citizens included: being a Colombian national; falling within the lowest two strata in the socio-economic household classifications (estrato) which entitled the household to receive important subsidies on public utilities (water, sanitation, electricity and gas); and being at least 18 years of age. Inclusion criteria for Venezuelan migrants included: being a Venezuelan national; falling within the first three socio-economic household classifications (estrato); and being at least 18 years of age. Stratum three was included for Venezuelan migrants, as it was determined that many migrants who were classified as being in the third stratum might have actually experienced lower socio-economic status after discounting classification by housing situation (Venezuelan migrants are more likely to have shared housing expenses and reside within multi-family homes).

The telephone survey collected key information on each respondent including health insurance status and health-care utilization measures, including (1) utilization of formal health services by any member of the household in the past 30 days, (2) utilization of virtual health services at any time, (3) utilization of COVID-19 testing at any time. Insurance status captured the health insurance plan that each individual was enrolled in (contributory or subsidized) or if the individual was uninsured (not affiliated with any formal insurance scheme).

Statistical Analyses

Health insurance and health-care utilization indicators were summarized for Venezuelans, Colombians, and the entire telephone survey population. Individual models were developed to measure the impact of insurance status on the measures of access and use of health-care services. All models also controlled for the following individual and household covariates: population group (Venezuelan migrant or Colombian citizen), gender (female or male), a continuous variable for age, educational attainment (high-school graduate or higher), employment status (reporting any paid work—formal or informal—at the time of the survey), and socio-economic status (income stratum 1 or higher). As explained above, all households in Colombia were classified by the Colombian government into socio-economic household classifications, with the lowest two strata qualified to receive significative public subsidies from the government.

All models also included a measure of current new COVID-19 cases per 100,000 that were extracted at the municipal level from the Colombian National Epidemiological Surveillance System (SIVIGILA) database. Models examining utilization of virtual visits and COVID-19 testing additionally included an indicator measuring whether or not the respondent had experienced any COVID-19-related symptoms in the previous 3 months (fever, dry cough, difficulty breathing, loss of taste or smell, or any other symptoms similar to cold or flu). All models were estimated using a mixed-effects logit model (melogit), a two-level (individual and municipality) random-intercept model analagous to a xtlogit model. All models also clustered standard errors at the municipal level. Model results were used to predict probabilities for three outcomes (access to health-care services, virtual visits, and COVID-19 tests) for Colombians and Venezuelans in each insurance scheme, holding all covariates at their mean values. Individual coefficients in the model that were found to have p-values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant in our analysis. Predicted probability values were utilized to measure disparities in access to health-care services, virtual visits, and COVID-19 tests between Colombians and Venezuelans both within and across insurance and uninsured categories. A final descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the variable in the telephone survey that captured time since entering Colombia for those Venezuelans who reported “unaffiliated.”

This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Boards at Brandeis University (protocol number 21010R-E) and University of Los Andes (protocol number 1235). All respondents were informed of the potential risks, protections, benefits, and knowledge to be gained for participating in the study through a script read by the interviewer, and then gave informed consent. The database contained no personal identifiers.

Results

provides a summary of the sample. The telephone survey includes 8,130 individuals, of which 36.5% (N = 2,971) of the respondents are Colombian and 63.5% (N = 5,159) are Venezuelan. The average age of respondents is 38 years old (Colombian) and 33 years old (Venezuelan). A smaller percent of Colombian respondents have higher educational levels when compared to Venezuelan respondents (36.6% of Colombians have completed high school and 5.0% completed University, compared with 42.4% of Venezuelans completing high school and 12.8% completing University). COVID-19 symptoms and cases per 100,000 are both higher for Colombians versus Venezuelans.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for study population from the telephone survey (N = 8,130), by Colombian and Venezuelan, % (N)

summarizes the health-care utilization results during the first wave of COVID-19 for Venezuelans and Colombians. Colombians consistently reported higher levels than Venezuelans in all the measures related to health-care use. For example, Colombians reported higher utilization of health-care services compared to Venezuelans (77.1% versus 70.0%), higher use of virtual health-care visits compared to Venezuelans (23.3% versus 9.0%), and higher ability to access a COVID-test than Venezuelans (14.1% versus 10.4%). Colombians also reported more COVID-19 symptoms than Venezuelans (22.3% versus 18.0%).

Table 2. Summary of health-care utilization, by Venezuelans and Colombians (%, N)

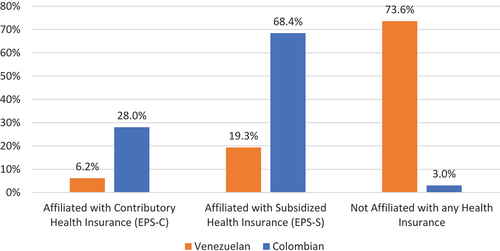

Given the importance of the various health insurance schemes in Colombia on their transition to Universal Health Coverage, we further explored the reported rates of insurance enrollment in the various insurance schemes, by Colombians and Venezuelans (). Within our sample, 73.6% of Venezuelans reported to not be affiliated with any scheme or not having health coverage compared to only 3% of Colombians. While these results are comparable to Colombia’s national insurance enrollment figures, where 98% of the Colombian population are insured,Citation28 there are minimal statistics available for comparison for Venezuelan migrants. According to administrative data from the Colombian Ministry of Health, as of October 2021, 68.7% of the Venezuelan migrants in Colombia who received health-care (1,000,366 persons) were not enrolled in any of the insurance schemes.Citation28

Figure 1. Insurance enrollment (%) in various insurance schemes, by Colombians and Venezuelans.

Additional characteristics of the nonaffiliated Venezuelans taken from the telephone survey provide a description of this population group. A small percentage (6%) of the nonaffiliated Venezuelans had entered Colombia in 2020; the remaining had entered in 2019 or earlier. Based on the new regulation for Venezuelan migrants in February 2021, these individuals would now be able to obtain a 10-year temporary permit for residence, providing access to formal health insurance. The Venezuelan nonaffiliated group also had the following characteristics: being an average of 32 years old, 63% female, 48% reporting having a job (95% of whom reported working in the informal sector), 49% having higher than a high-school education, and 47% in the lowest income strata.

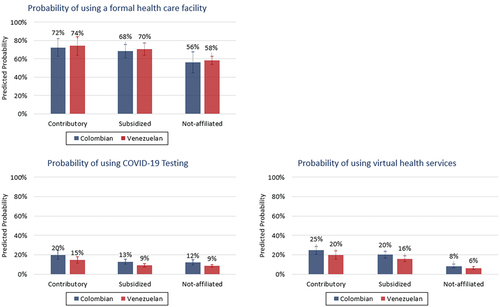

shows the relationship between insurance status and our three outcome measures for Colombians and Venezuelans: utilization of formal health-care services, receiving a COVID-19 test, and use of virtual health services. The results show that being enrolled in either the contributory or subsidized regime is associated with higher access and use of health-care services than not being affiliated with any health insurance scheme. The results also show that access improves for both groups as individuals move from one scheme to the next. For all three services, for both Colombians and Venezuelans, the use of services is higher in the contributory and subsidized regimes than for the nonaffiliated. In addition, for routine health-care services (accessing a health facility in the last 30 days), within each insurance scheme, including the uninsured, equality has been achieved; there is minimal difference in access between Colombians and Venezuelans. The data actually show that for accessing health-care services in the last 30 days, Venezuelans have slightly higher probability of accessing health-care services than Colombians within all insurance schemes. However, differences remain between Colombians with access to insurance and the majority of Venezuelans, who remain unaffiliated. Colombians in the contributory insurance regime had a 4.2, 2.2 and 1.2 times higher probability of having access to a virtual visit, a COVID-19 test, and a formal health-care facility, respectively, than a Venezuelan not affiliated with any health insurance. Also, for new services offered because of the COVID-19 pandemic—testing and virtual visits—there are disparities in access for Colombians and Venezuelans within each scheme and for the uninsured. The largest inequality is between Colombians and Venezuelans in the subsidized regime in accessing COVID-19 tests, showing a 44% difference in access between Colombians (13%) and Venezuelans (9%).

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of utilization of a formal health facility (panel 1), using COVID-19 testing (panel 2), and using virtual health services (panel 3), by Venezuelans (red) and Colombians (blue), and insurance status (contributory, subsidized, or not affiliated) with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

This is one of the few studies where telephone survey data were collected on access to health-care services during the COVID-19 pandemic in a country with a large migrant population. The results are important as we contemplate the impact of COVID-19 on health systems globally and also what lessons we can learn from Colombia to apply in other countries with migrant and non-citizen populations. The results show that universal health coverage and access to health-care services go hand in hand. Enrolling migrants in either the subsidized or contributory regime increases their access to health-care services, and equality between Colombians and Venezuelans within the same insurance schemes can be achieved for some services. The results of this analysis provide useful information for policy makers, implementers, and government officials who are providing services to host and migrant populations.

Colombia provides a unique example to examine access to services for Venezuelan migrants, as a country with a health system that can, in theory, absorb Venezuelan migrants rather than setting up a parallel system. As is shown above, 26% of Venezuelan migrants from the telephone survey were absorbed into either the contributory or subsidized regimes and reported increased access to health-care services in comparison to those not affiliated with any insurance scheme. Despite this positive result, the data also show that 74% of those Venezuelan migrants in the telephone survey, living in Colombia, had not been absorbed into any scheme and had reduced access to health-care services, especially for new services that were offered since the start of the pandemic—virtual visits and COVID-19 testing. These findings are strengthened by their consistency with health service utilization rates, drawing from administrative data from the Colombian Universal Health Insurance system. Those data also showed that Colombians had higher rates of utilization of health-care services than Venezuelans.Citation40

Our survey was conducted during the first wave of COVID-19 in Colombia when testing for COVID-19 and virtual visits in place of in-person visits were just beginning to be rolled out. As our data show, inequalities are higher both within and across schemes between Colombians and Venezuelans for these two services. While this could be related to lower rate COVID-19 symptoms, as reported by Venezuelan migrants above, in a companion study, we also found that there was a lower number of officially registered COVID-19 cases among Venezuelans. This implies that since official registration of COVID-19 cases requires the detection of the virus by an official test, Venezuelans most likely face greater difficulty and barriers in accessing testing and treatment, especially for those who do not have regularized status.Citation40 These results suggest that if a country has the ability to absorb migrants or non-citizens into their current health system, access to routine services will increase while access to new services (like virtual visits and COVID-19 tests) may be more difficult.

Enrolling migrants into already established systems is difficult. Our data show that 74% of the Venezuelan migrants surveyed were unenrolled in either the subsidized or contributory regime at the time of the survey—September through November 2020. This result suggests that challenges may persist on multiple levels. First, barriers remain in obtaining legal status (before and after ETPMV) as migrants must enter the country through an official checkpoint, present a valid passport, and have no judicial record or deportation measure in force.Citation22,Citation41 There are also additional reasons why Venezuelans may not apply for PEP or ETPMV, including registration constraints, lack of information, distrust of Colombian authorities and/or fear of deportation, unclear expected net benefits of regularization, or anticipated migration back to Venezuela or another country.Citation42 Second, multiple steps remain to enroll in an insurance scheme once one has ETPMV status, including providing the appropriate individual or family member identification (in the case of minors) and an identification of migratory status.Citation43 As our findings show that access to comprehensive health services is directly related to affiliation with an insurance scheme, this raises issues of tying access to health services with regularization, especially during the COVID-19 era. Other studies are currently underway to analyze how to improve the process of migrant integration, with lessons for other countries.

While our results show that insurance does assist with reducing disparities in health-care utilization more generally, the use of virtual health-care visits is low and unequal between Colombians and Venezuelans. One positive outcome of the COVID-19 pandemic for health systems around the world has been the improved structure and acceptability of virtual health-care visits for many services. The use of virtual visits has increased substantially in many places, supported through financial and system investments. In the United States alone, with federal financing and structural support, the number of weekly telehealth visits increased substantially by 14 percentage points, compared to baseline figures at the start of the pandemic.Citation44

These study results present a timely baseline assessment of access to health-care services before the ETPMV in February 2021. The Colombian system is unique in that it has a formal health insurance scheme and regularization mechanism—ETPMV—that Venezuelan migrants can use to enroll in various health insurance schemes. Our data show that enrolling in any scheme increases one’s access to health-care services in comparison to nonaffiliated. This study is an excellent baseline to compare the change in enrollment and access to health-care services since the ETPMV in 2021. These results combined with a post-ETPMV study would be valuable to those developing policies for migrant populations in countries around the world and would include important lessons on the implementation of the ETPMV.

The study highlights the importance of analyzing data for host and migrant populations in order to begin to understand how the rights of non-citizens, as upheld in international human rights law, can be met in practice. Both the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights and the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its Protocol guarantee the right of all residents to “the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health,”Citation45 irrespective of migration status.Citation46,Citation47 However, countries have struggled to uphold and enforce the delivery of these rights due to problems of resource allocation and the importance given to citizenship.Citation15,Citation48 This study’s findings from Colombia—a signatory to these conventions—highlight the potential of universal health coverage for guaranteeing access to both citizen and non-citizen populations, with the understanding that creating systems that further integrate migrant populations into national systems for insurance and delivery of care will benefit both populations and carry positive gains for the entire community. As one of the few countries that provide a pathway to regularization for migrants without extensive eligibility criteria, Colombia has high potential for extending services to non-citizen populations given its existing system of health insurance. However, with 74% of Venezuelans surveyed still unregularized, this study highlights the need to make current structures more accessible to migrant populations.

Despite the importance of this study, there are several limitations. First, this study does not analyze the costs of services for Venezuelan migrants, nor limits to regularization and enrollment in either the contributory or subsidized regime that could contribute to higher health-care costs. As mentioned above, any individual (Colombian or Venezuelan) who is not affiliated with any formal health insurance scheme has access only to emergency health-care services. As we know from many studies done in multiple settings, providing emergency care is significantly more expensive than treating non-emergent conditions in a primary care setting and expanding access to primary and preventative health services is an economic investment in the long term.Citation49–52 An analysis of the cost of services for Venezuelan migrants is needed. Secondly, as noted in the Supplementary Materials, there are a number of other variables in the telephone survey that could not be analyzed within this particular study and could contribute to further analyses of access to and barriers to health-care services for Venezuelan migrants. Finally, even though the telephone survey sample is large, some subgroups (unenrolled Colombians), comprise a smaller group limiting the power of these results.

Conclusion

Colombia provides one example of a country that has opted to absorb non-citizen, migrant populations, into their standard health system, increasing access to some health-care services for Venezuelan migrants integrated into their contributory or subsidized health insurance schemes. For non-citizens who were affiliated to an insurance scheme, access to routine health services was virtually on par with the Colombian host population. However, barriers to integration and access still remain, especially for the 74% of Venezuelan migrants without any form of health insurance. These individuals had reduced access to health-care services, especially for new services that were offered since the start of the pandemic—virtual visits and COVID-19 testing—highlighting the need to make current structures more accessible to migrant populations. While the February 2021 presidential decree offers a path toward regularization for more migrants, the process is likely to be complex and slow. Given the challenges found in enrolling in various health insurance schemes after regularization in Colombia, additional supportive policies should be contemplated to hasten integration that would benefit both Colombians and Venezuelans.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.1 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Natalia Iriarte Tovar for supporting and coordinating the fieldwork preparation and implementation during the telephone survey data collection as well as other University of Los Andes and Brandeis University researchers including Adelaida Boada and Jamie Jason. The authors also thank IQuartil for collecting data through a telephone survey format during the COVID-19 pandemic. The authors would like to thank Thomas Bossert and other consortium members, who provided key input on initial telephone survey results, and Clare L. Hurley for editorial assistance.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DMB, upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/23288604.2022.2079448.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet. 2021;397(10268):61–11. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5.

- Armocida B, Formenti B, Ussai S, Palestra F, Missoni E. The Italian health system and the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet. 2020;5(5):e253. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30074-8.

- Blumenthal D, Fowler EJ, Abrams M, Collins SR. Covid-19 — implications for the health care system. N Eng J Med. 2020;383(15):1483–88. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb2021088.

- Tessema GA, Kinfu Y, Dachew BA, Tesema AG, Assefa Y, Alene KA, Aregay AF, Ayalew MB, Bezabhe WM, Bali AG, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and healthcare systems in Africa: a scoping review of preparedness, impact and response. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(12):e007179. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007179.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration; 2022. [accessed 2022 Apr 14]. https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2022.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). Norwegian Refugee Council. Global Report on Internal Displacement 2020. 2020. [accessed 2022 Apr 14]. https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2020-IDMC-GRID.pdf.

- Ullah AA. Rohingya refugees to Bangladesh: historical exclusions and contemporary marginalization. J Immigr Refug Stud. 2011;9(2):139–61. doi:10.1080/15562948.2011.567149.

- Rawal LB, Kanda K, Biswas T, Tanim I, Dahal PK, Islam R, Nurul Huda T, Begum T, Sahle BW, Renzaho AMN, et al. Health problems and utilization of health services among forcibly displaced myanmar nationals in Bangladesh. Global Health Res Policy. 2021;6(1):39. doi:10.1186/s41256-021-00223-1.

- Chaudry A, Fortuny K. Overview of Immigrants’ Eligibility For SNAP, TANF, Medicaid, and CHIP. Urban Institute. 2014. [accessed 2022 Apr 26]. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/overview-immigrants-eligibility-snap-tanf-medicaid-and-chip.

- UNHCR. UNHCR fact sheet: Jordan. 2021. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://reporting.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/Jordan%20country%20factsheet%20-%20February%202021.pdf.

- Zard M, Lau LS, Bowser DM, Fouad FM, Lucumí DI, Samari G, Harker Roa A, Shepard DS, Zeng W, Moresky RT, et al. Leave no one behind: ensuring access to COVID-19 vaccines for refugee and displaced populations. Nat Med. 2021;27(5):747–49. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01328-3.

- UNHCR. UNHCR - refugee data finder. 2021. [accessed 2022 Jan 18]. https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

- Arnson CJ. The Venezuelan refugee crisis is not just a regional problem. The Atlantic. 2020 Apr 16. [accessed 2022 Jan 18]. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/venezuela/2019-07-26/venezuelan-refugee-crisis-not-just-regional-problem.

- Baddour D. Colombia’s radical plan to welcome millions of Venezuelan migrants. 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/01/colombia-welcomes-millions-venezuelans-maduro-guaido/581647/.

- Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, Orcutt M, Burns R, Barreto ML, Dhavan P, Fouad FM, Groce N, Guo Y, et al. The UCL–lancet commission on migration and health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet. 2018;392(10164):2606–54. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7.

- Mushomi JA, Palattiyil G, Bukuluki P, Sidhva D, Myburgh ND, Nair H, Mulekya-Bwambale F, Tamuzi JL, Nyasulu PS. Impact of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) crisis on migrants on the move in Southern Africa: implications for policy and practice. Health Syst Reform. 2022;8(1):e2019571. doi:10.1080/23288604.2021.2019571.

- Gelatt J, Bernstein H, Koball H. State immigration policy resource. Urban Institute. 2017. [accessed 2021 May 14]. https://www.urban.org/features/state-immigration-policy-resource.

- Doocy S, Lyles E, Akhu-Zaheya L, Oweis A, Ward N, Burton A. Health service utilization among Syrian refugees with chronic health conditions in Jordan. PloS One. 2016;11:e0150088. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0150088.

- Tan V. The young and the hopeless in Bangladesh’s camps. UNHCR. 2013. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.unhcr.org/news/latest/2013/1/50ffe3c29/young-hopeless-bangladeshs-camps.html.

- Amnesty International. “I Don’t Know What My Future Will Be”: Advocacy Update on Rinhingya Refugees in Bangladesh. 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.amnestyusa.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/I-dont-know-what-my-future-will-be.pdf.

- Baddour D. This country is setting the bar for handling migrants. The Atlantic. 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2019/08/colombias-counterintuitive-migration-policy/596233/.

- Así se vivía cuando la ola migratoria era de Colombia hacia Venezuela. El Tiempo. 2018. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.eltiempo.com/mundo/venezuela/anteriormente-la-ola-migratoria-era-de-colombianos-hacia-venezuela-181258.

- López Maya M. Chavismo crisis in today´s Venezuela. Estudios Latinoamericanos. 2016;(38):159–185–185. doi:10.22201/cela.24484946e.2016.38.57462.

- Bahar D, Dooley M. Venezuela refugee crisis to become the largest and most underfunded in modern history. Brookings. 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 14]. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2019/12/09/venezuela-refugee-crisis-to-become-the-largest-and-most-underfunded-in-modern-history/.

- Giedlon U, Villar- Uribe M. Colombia’s universal health insurance system. Health Aff. 2009;28(3):853–63. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.853.

- Rosa RM, Alberto IC. Universal health care for Colombians 10 years after Law 100: challenges and opportunities. Health Policy (New York). 2004;68(2):129–42. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.10.004.

- OECD. OECD reviews of health systems: Colombia 2016; 2015 [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. doi:10.1787/9789264248908-en

- Dirección de Epidemiología y Demografía Viceministerio de Salud Pública y Prestación de servicios. Seguimiento a La Situación de Salud de La Población Migrante Procedente de Venezuela, Para El Período Comprendido Entre El 1 de Marzo de 2017 y El 31 de Agosto de 2021; 2021: Annex 3, 28. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/VS/ED/GCFI/informe-circular-029-agosto-2021.pdf.

- Villamil SL, Dempster H. Why Colombia granted full rights to its 1.7 million Venezuelans, and what comes next. Center for global development: ideas to action. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.cgdev.org/blog/why-colombia-granted-full-rights-its-17-million-venezuelans-and-what-comes-next.

- Guerrero R, Prada SI, Pérez AM, Duarte J, Aguirre AF. Universal health coverage assessment: Colombia. Global Network for Health Equity. 2015. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.icesi.edu.co/proesa/images/GNHE%20UHC%20assessment_Colombia%204.pdf.

- Bolívar LR. Dejusticia intervenes in defense of Venezuelan migrants’ right to health. Dejusticia. 2018. [accessed 2022 Apr 14]. https://www.dejusticia.org/en/dejusticia-intervenes-in-defense-of-venezuelan-migrants-right-to-health/.

- Albarracín M, Rozo V, Bolívar LR, Ruiz S, Yepes RU, Rodrigez-Garavito C. Colombia must obtain resources to guarantee the right to health of Venezuelan migrants: constitutional court. Dejusticia. 2018. [accessed 2022 Apr 14]. https://www.dejusticia.org/en/litigation/colombia-must-obtain-resources-to-guarantee-the-right-to-health-of-venezuelan-migrants-constitutional-court/.

- Sarralde Duque M. Derechos que han ganado venezolanos en la Corte a través de tutelas. El Tiempo. 2018. [accessed 2022 Apr 25]. https://www.eltiempo.com/justicia/cortes/derechos-que-han-ganado-los-venezolanos-en-la-corte-con-tutelas-279168.

- Agence France Presse. Colombia excluirá de vacunación a venezolanos que estén irregulares en su territorio. France 24. Published December 21, 2020. [accessed 2022 Apr 25]. https://www.france24.com/es/minuto-a-minuto/20201221-colombia-excluir%C3%A1-de-vacunaci%C3%B3n-a-venezolanos-que-est%C3%A9n-irregulares-en-su-territorio.

- Welsh T. In brief: legal status for Venezuelans in Colombia to improve vaccine access. DEVEX. 2021. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.devex.com/news/in-brief-legal-status-for-venezuelans-in-colombia-to-improve-vaccine-access-99118.

- Cancillería de Colombia. Estatuto Temporal de Protección para Migrantes Venezolanos. 2022. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.cancilleria.gov.co/estatuto-temporal-proteccion-migrantes-venezolanos.

- Canning D, Karra M, Dayalu R, Guo M, Bloom DE. The association between age, COVID-19 symptoms, and social distancing behavior in the United States. medRxiv.2020.04.19.20065219. doi:10.1101/2020.04.19.20065219.

- AlRasheed MM, Alsugair AM, Almarzouqi HF, Alonazi GK, Aleanizy FS, Alqahtani FY, Shazle GA, Khurshid F. Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice of security and safety workers toward the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2021; 9 accessed 2022 Jan 19. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpubh.2021.631717.

- Azlan AA, Hamzah MR, Sem TJ, Ayub SH, Mohamed E. Public knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: a cross-sectional study in Malaysia. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0233668. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0233668.

- Shepard DS, Boada A, Newball D, Sombrio A, Rincon CW, Iriarte N, Catalina D, Agarwal-Harding P, Jason J, Harker Roa A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Colombia on Utilization of Medical Services by Venezuelan Migrants and Colombian Citizens. 2021. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/covid_colombia_brief_v60.pdf.

- Acosta D, Blouin C, Freir LF. La emigración venezolana: respuestas latinoamericanas. 2019. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.fundacioncarolina.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/DT_FC_03.pdf.

- Ibánez AM, Moya A, Ortega MA, Chatruc MR, Rozo SV. Life out of the shadows: impacts of amnesties in migrant’s life. In: 2nd Research Conference on Forced Displacement. 2021. [accessed 2022 Jan 22]. https://www.jointdatacenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Life_Out_of_the_Shadows_PEP_Survey-4-002.pdf.

- Ministro de Salud y Protección Social. Circular No. 000025 de 2017. 2017. [accessed 2022 Apr 28]. https://www.minsalud.gov.co/Normatividad_Nuevo/Circular%20No.%20025%20de%202017.pdf.

- Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient visits: a rebound emerges. To the Point (Blog), Commonwealth Fund. 2020. doi:10.26099/ds9e-jm36.

- UN General Assembly. International covenant on economic, social and cultural rights. Vol United Nations Treaty Series. 1976;993:3. [accessed 2022 Jan 19]. https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/cescr.aspx.

- UN General Assembly. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. 1954. [accessed 2022 Jan 19]. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/StatusOfRefugees.aspx.

- UN General Assembly. Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. 1967. [accessed 2022 Apr 28]. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/ProtocolStatusOfRefugees.aspx.

- Dittrich R, Cubillos L, Gostin L, Chalkidou K, Li R. The international right to health: what does it mean in legal practice and how can it affect priority setting for universal health coverage? Health Syst Reform. 2016;2(1):23–31. doi:10.1080/23288604.2016.1124167.

- Engström MF Lars Borgquist S. Is general practice effective? A systematic literature review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2001;19(2):131–44. doi:10.1080/028134301750235394.

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x.

- Hone T, Gurol-Urganci I, Millett C, Başara B, Akdağ R, Atun R. Effect of primary health care reforms in Turkey on health service utilization and user satisfaction. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(1):57–67. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw098.

- Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Effect of restricting access to health care on health expenditures among asylum-seekers and refugees: a quasi-experimental study in Germany, 1994–2013. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0131483. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131483.

- ELRHA. 15 research studies awarded to support COVID-19 response. 2020. [accessed 2022 Apr 27]. https://www.elrha.org/news/research-studies-support-covid-19-response/.