Abstract

This paper looks at ‘Japan’s secular stagnation and beyond’ from the perspective of institutional and ideational change and coherence (or complementarity). The coherence of Japan’s postwar productionist model began to fray in the 1980s, and was lost at both macro and micro levels in the 1990s, contributing to secular stagnation. The paper steers a nuanced path between the view that this stemmed from Japan doggedly maintaining its postwar model, and conversely, from abandoning it. Since the mid 2010s, Japan has embarked on digital and green transformations under the banners of Society 5.0, DX, ESG/SDGs, green growth and sustainable capitalism. These are bringing about institutional and ideational change, but if a new coherence is to be attained, an internal contradiction must be acknowledged and addressed.

Introduction

This paper looks at ‘Japan’s secular stagnation and beyond’ from the perspective of institutional and ideational change and coherence (or complementarity). It steers a nuanced, middle ground between attributing Japan’s secular stagnation to an increasing lack of fit with a changing world (which it helped to change), and to abandoning its erstwhile successful model under a combination of external pressure and seduction. Many studies have analyzed aspects of Japan’s ‘lost decades,’ focusing on macroeconomic policies, financial sector crisis, innovation loss, demography and other factors, but an important aspect when considering prospects for Japan’s future is how these interact, in addition to its responses to a drastically changing external geopolitical and economic environment.Footnote1 The complexity implied by this will be addressed through visual organizing constructs consisting of state-market and organization-technology dyads, which broadly correspond to the macro and microeconomy, extending the institutionalist perspective.

These dyads will help to visualize the coherence of Japan’s postwar high growth system or model, and how this coherence began to break down in the 1980s, both institutionally and ideationally, with growing tensions within and between the dyadic pairs, and geopolitical contextual change. Japan’s secular stagnation can be seen through the lens of growing institutional misalignment, as well as ideational (ideological and motivational) conflict at both the macro and micro levels. The outcome of the breakdown of coherence may be seen in the government emerging as the largest holder of listed company shares, banks amassing huge stocks of government bonds, companies building up massive internal reserves (and using some for share repurchase schemes), and workers struggling to meet their daily needs while trying to save for an uncertain future.

The dyads will also help to consider the prospects for a new coherence with the emergence of the digital and green economies, under the banners of ‘Society 5.0’′ and ‘sustainable capitalism,’ and digital transformation and ESG (environment, social, governance) corporate governance and management. A new coherence which is reflected not just ideationally but also – eventually – institutionally would modify the above imbalances, but would not necessarily reinstate higher GDP growth levels.

The paper is organized in four sections. The first section briefly revisits the literature on institutional complementarity. Drawing on and extending the concept, it proposes two dyads as conceptual scaffolding for the paper. The second section relates these dyads to Japan up until the 1980s. The institutional and ideational coherence of Japan in this period creates a contrast with what follows. The third section introduces an evolutionary dynamic into the dyads, and through this examines the breakdown of institutional and ideational coherence, accompanied by secular stagnation. The fourth section adds a further detail to the dyads, of Society 5.0 and digital and sustainable transformation respectively, to consider Japan’s prospects for restoring its lost coherence. The four sections comprise a progressive chronological, conceptual and empirical exploration of Japan’s secular stagnation and beyond.

Revisiting institutional complementarity

The importance of institutional complementarity has been debated from a variety of viewpoints, particularly in relation to ‘varieties of capitalism’ (VoC). Boyer (Citation2005, 367) defines it as ‘a configuration in which the viability of an institutional form is strongly or entirely conditioned by the existence of several other forms, such that their conjunction offers greater resilience and better performance compared with alternative configurations.’ Even defined as such, it is a slippery concept. ‘Complementarity’ can be based on similarity of intent or affinity, as in financial regulation and labor market protection, or upon difference – the latter in a countervailing or compensating relationship (Campbell Citation2011) – and the same institutions may interact on a basis of similarity under one variety of capitalism, and on a basis of difference under another (Kang and Moon Citation2012).

Kang and Moon attempt to break the over-simplified liberal market economy (LME) – coordinated market economy (CME) dichotomy of VoC (Hall and Soskice Citation2001) by introducing a third category of state-led market economy (SLME), but as Boyer points out, any variety of capitalism, or country, will exhibit a variety of coordinating mechanisms, which are not necessarily tightly coupled, and which change over time.Footnote2 Through trial and error, initially disconnected institutional forms may attain a (temporary) coherence.

Furthermore, some institutions may be central, or hierarchically influential. In Boyer’s Régulation approach the (postwar) Fordist wage-labor nexus was the lynchpin for a configuration of institutions, but was replaced by a monetary and financial regime in the US in the 1980s, and to varying degrees in other countries, Japan included. We will return to this point later in the article.

The perspective of institutional complementarity adopted here overlaps with Boyer’s nuanced, expansive and evolutionary view, and also draws on Dore’s (Citation1987) ‘institutional interlock and motivational congruence’ of the postwar Japanese model, re-expressed here as ‘institutional and ideational coherence.’ In short, I will argue that this coherence, which was built up in the postwar period, began to fray at the macro level from the 1980s, and the micro level from the 1990s, giving rise to Japan’s secular stagnation. I will also argue that Japan is attempting to re-create institutional and ideational coherence around a new configuration of institutions at both the macro and micro levels, and subject this to the Régulation test of institutional centrality or hierarchy. This will surface an apparent contradiction, which may or may not be overcome in time, as new institutions are built and tested.

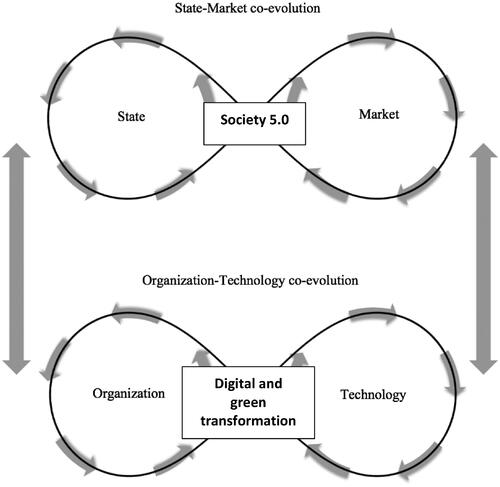

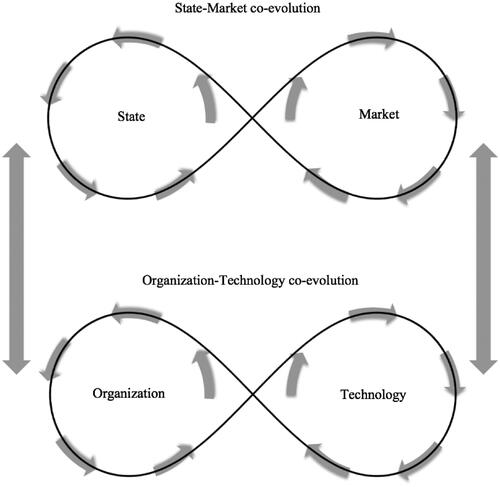

Finally, a broad perspective is adopted here, extending to political economy on the one hand, and (neo-Schumpeterian) technology and organizations on the other. This is done in order to bring the state and technology, which are often missing or shadowy in institutionalist writing, into the picture. The organizing constructs can be presented visually as dyads ().Footnote3 The dyads broadly correspond to a macro- and micro-level of analysis respectively. The upper dyad shows states and ‘markets’ (encompassing corporations and finance) – a combination familiar to political economy – which mutually interact, as shown by the arrows moving in opposite directions. The mutual interaction, which can be supportive or conflictual, signals a co-evolutionary process, which will be described in Section 3. Modern nation states and capitalism emerged together in this process.Footnote4 The lower dyad depicts a mutual relationship between organization and technology which is also co-evolutionary; major new technologies give rise to new forms of organization, and vice versa.

Figure 1. State-market and organization-technology dyads. Source: Whittaker et al. Citation2020, 7.

In addition to the interactions within the dyad pairs, there are interactions between them, indicated by the vertical arrows, which are two-ended because causal influences work in both directions. Finance and financial (de-)regulation, which plays an important role in state-market relations, have an important impact on industrial organization and technology development. The latter, on the other hand, influence state-market relations through effects on employment, the geography of production systems, and so on. Broadly speaking, the lower dyad represents the ‘engine’ of economic growth, and the upper dyad the regulatory mechanisms, which direct resource allocation, and influence incentives, regulation and distribution.

Importantly, though not shown in the figure, the dyads of dominant power(s) form the basis of an international geopolitical and economic system, which has a strong influence on institutional development in countries incorporated into the system. The influence depends on the timing of that integration; Japan was initially integrated into the British-led international order of imperialism and the gold standard in the 19th century, and re-integrated under US-led embedded liberalism and the Cold War after 1945, resulting in quite different institutional development.

Japan’s postwar productionist model

Let us consider Japan’s postwar productionist system in terms of . Japan’s postwar rise from ruin in 1945 of course came on top of an earlier period of modern nation building and industrialization, in a very different world. The global order that Japan was progressively integrated into in the late nineteenth century, capped by its adoption of the gold standard in 1898, was British-led, and imperialist, reflecting the tensions and contradictions of that period.Footnote5 National institutions were built, with a tension between finance and industry. Technologically and organizationally, Japan was trying to master factory production, electricity, the production of steel, the organization of railways, and mechanical weaponry in a condensed period of time. In fact, Taylorist principles were introduced to Japan in 1911, the same year as The Principles of Scientific Management was published (Tsutsui Citation1998).

As the scale of industry grew and management started to become more professionalized, however, and as the British-led order crumbled, there arose in the 1920s an intense debate about the roles of both capital and labor in the pursuit of national goals. The Showa Financial Crisis (1927), Wall Street Crash (1929) and disastrous return to the gold standard (1930–31) led to a fundamental re-orientation of the financial sector, curbing of shareholder rights, increasing government direction over the economy… and militarization. Japan was not alone in these developments.

Noguchi (Citation1998) argues that Japan’s ‘1940 system’ was carried over into the postwar era. Yet it should be noted that government involvement in economies increased everywhere in the 1930s and 1940s, the U.S. included.Footnote6 The new U.S.-led postwar order was not a re-run of British order; Ruggie (Citation1982) called it ‘embedded liberalism’:

The task of post-war institutional reconstruction… was to manoeuvre between these two extremes [of liberal orthodoxy and its rejection] and to devise a framework which would safeguard and even aid the quest for domestic stability without, at the same time, triggering the mutually destructive external consequences that had plagued the interwar period. This was the essence of the embedded liberalism compromise: unlike the economic nationalism of the thirties, it would be multilateral in character; unlike the liberalism of the gold standard and free trade, its multilateralism would be predicated upon domestic interventionism (Ruggie Citation1982, 393).

This stance informed the Occupation, whose priorities changed over time, from democratization to economic rehabilitation, with the emerging Cold War. Japan set about rebuilding its economy under partially reformed state institutions guiding partially restructured economic organizations. The Finance Ministry created a tiered and mixed banking system to deliver short- and long-term finance which from the 1950s oversaw a massive expansion of credit. Labor and industrial relations were regulated broadly along the lines of the US New Deal – labor unions and collective bargaining were recognized, as long as they did not threaten political stability.

The institutions of class compromise and conflict resolution were a product of their time. They included the tripartite Japan Productivity Center in 1955, whose three principles of employment stability, prior consultation and a fair distribution of the fruits of productivity improvement did not mention shareholders – this was an age of managerial, productionist capitalism. Also in 1955 Shuntō (the Spring Wage Offensive) was formalized, becoming a mechanism to distribute the fruits of rapid growth and productivity increases, before tipping to wage restraint in the 1970s. Public and private sector wage increases were linked in the 1960s.

Concerning the organization-technology dyad, the U.S. not only opened its markets to Japanese exports, but also its factories to productivity missions from Japan, as well as European allies. The latest organization principles were quickly absorbed, with modification. Quality and industrial relations experts visited Japan; their ideas were also quickly absorbed, and large companies reformed their management and employment relations in what became known as the ‘three pillars’ of ‘Japanese-style management.’Footnote7 As the name suggests, this complex of institutions was central to Japan’s productionist system; in Régulationist terms, its wage-labor nexus.

Thus Japanese managerial or productionist capitalism flourished within a context of postwar embedded liberalism, and Japan developed its own variant of Fordism, on the basis of quasi vertical integration. Its macro- and micro-level institutions achieved a high degree of coherence or interlock, giving rise to the perception of ‘Japan Inc.’ This was not just about the ‘developmental state’ directing the economy (Johnson Citation1982). It was also about stable macroeconomic management, stable and reciprocal shareholding which complemented indirect financing through main banks, and long-term interfirm relations, including supplier relations, which enhanced cost competitiveness and facilitated technology upgrading and diffusion among supplier firms. These complemented intra-firm management and employment relations.

While less benign for those who were on its periphery – especially female workers, and workers in small firms – this system was highly effective in generating economic growth, and arguably became even more effective in the 1970s. Japan navigated the ‘Nixon shocks’ (1970) and ‘oil shocks’ (1973, 1979), taming inflation, and paving the way for a massive increase in exports of machine tools, electric goods and vehicles. This resulted in intense trade conflict, and pressure on Japan to change its ‘system’ or model. Conversely, however, it also played a part in changing the US, and the nature of its geopolitical dominance, by putting pressure on the US production system, prompting restructuring and the propagation of emerging neoliberal capitalism. Embedded liberalism gave way to neoliberalism, financialization, and globalization.

The fall of the postwar model, and secular stagnation

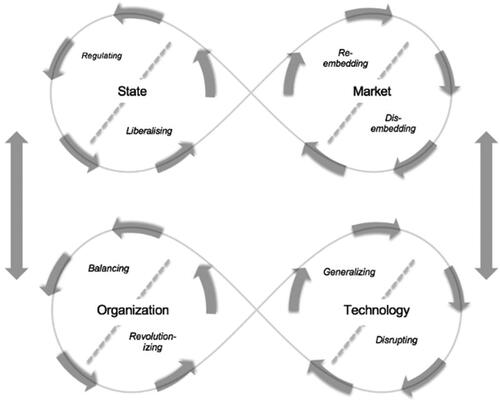

Capitalism in the early twentieth century, under the British-led international order (or disorder), evolved via the 1930s wartime economy to postwar managerial, productionist capitalism under the influence of US-led embedded liberalism. This upheaval and evolution can be made more understandable with added detail to our dyads, as shown in .

Figure 2. State-market and organization-technology double movements. Source: Whittaker et al. Citation2020.

The upper dyad introduces a ‘dis-embedding’ and ‘re-embedding’ dialectic in markets, and ‘liberalizing’ and ‘regulating’ in states to reflect the role of the state in creating markets. This draws on Karl Polanyi’s (Citation1944) ‘double movement,’ in which state-led ‘dis-embedding’ of markets provokes a counter-action, which may take many forms, some of them – like the rise of Nazi Germany – malign.Footnote8 Unsurprisingly, there has been a resurgence of interest in Polanyi’s work, with parallels drawn between the late nineteenth-early twentieth century and US-led neoliberalism a century later (e.g. Vercelli Citation2013). For in fact that is what postwar embedded liberalism gave way to from the 1970s. It is in this geopolitical context that we must situate Japan’s secular stagnation.

The second dyad draws on a similar – but neo-Schumpeterian – schematic of the co-evolution of technology and organizations by Bodrožić and Adler (Citation2018), whose conceptual innovations are, first, to link the technology cycles to organizational paradigms (as in ), and to management ideologies; and second, to identify a dialectic of ‘revolutionizing,’ and ‘balancing’ phases in organization paradigms, which we have linked to the disrupting and generalizing processes of technology evolution and diffusion. In Bodrožić and Adler’s model, which focuses on the US, the technological revolution brought about by steel and electricity was accompanied organizationally by the unitary, centralized ‘factory,’ whose revolutionizing phase was scientific management, and balancing phase was human relations. This was superseded in the postwar period by automobiles and oil, and ‘strategy and structure’ phases in the Fordist corporation, whose revolutionizing phase was ‘strategy and structure’ and balancing phase was ‘quality management.’ This postwar system began to give way to computers and telecoms, and the network form of organization, from the 1980s. We must situate Japan’s secular stagnation in this context as well.

Japan’s secular stagnation has been attributed by some to its conversion to neoliberalism, and by others to continued adherence to its postwar model when it became increasingly inappropriate. Representing the first view – (partial) conversion – Lechevalier (Citation2014) argues that the infiltration of neo-liberal concepts, first under 1980s’ PM Nakasone, produced an asset bubble, change with unintended consequences, a decline in institutional complementarity, a rupture of the social compromise, and a precipitous rise in inequality. Representing the second view – loss of fit with a changing environment – Katz (Citation1998) attributed Japan’s economic travails to following ‘mainframe economics in a PC world,’ both literally in the 1980s and early 1990s, and figuratively.Footnote9 Although these views differ in their starting (and normative) assumptions, they are not entirely mutually exclusive, and the dyads help to unpack and allocate them – crudely put, the (partial) conversion thesis more to the state-market dyad, with caveats, and the loss of fit thesis more to the technology-organization dyad. Let us develop this view by first considering how Japan’s environment changed, and then changes within Japan itself.

Changing environment

The two great changes in Japan’s environment have originated from the dominant postwar power, the US, and the rise of Asia respectively. Starting with the US, in response to growing economic and social problems, postwar embedded liberalism was abandoned in favor of neoliberalism, market solutions, and indeed a marketization of the state itself (Galbraith Citation2008). A driving force was finance, which by the 1970s had already begun to chafe at its regulatory constraints, rising inflation and declining manufacturing profitability, which Japanese exports contributed to. Progressively de-regulated from the late 1970s, finance was globalized; a new era of financialization had begun.Footnote10 Minsky (Citation1992) depicted this as a transition from managerial capitalism to money manager capitalism. The US sought to export this model, more aggressively than it had in the postwar period (cf. Amsden Citation2007).

Relatedly, by the early 1980s US managers, under growing pressure from assertive shareholders and Japanese competitors, began to outsource production – in some cases all of their production – to domestic contract manufacturers, to emerging Korea and Taiwan, and ultimately to mainland China (Sturgeon Citation2002; Milberg Citation2008). The era of vertically integrated Fordist corporations gave way to a new era of vertical specialization, of networked firms linked by global value chains (GVCs), facilitated by the emerging information and communication technologies (ICT). The challenge to Japanese manufacturing accelerated with restructuring in the US after the dotcom bubble burst, and China’s WTO accession in 2001.

Further, with the deepening of the digital revolution yet another organizational form subsequently emerged, namely platforms. Smart phones incorporate layers of platforms, each with dominant platform ‘owners’ and a variety of complementors, in nested ecosystems which are global, handle high volumes, and change very quickly. Platform innovation and organization is now spreading to new industries, with automobiles in its sights. These successive new technologies and organization forms, it should be noted, bear the imprint of neoliberalism and financialization.

From a Polanyian perspective, the inevitable happened. As markets expanded globally, becoming insulated from state control, resistance erupted, and crises escalated. Yet the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 resulted in a bail out for the financial sector, at huge social cost, splitting the middle class and raising inequality to 1920s levels, paving the way for Trump – and Brexit in the UK – in 2016.

Domestic problems

Japan in the 1980s came under pressure to curb its massive trade surpluses and open to inward trade and investment, through ‘voluntary’ export restraint, allowing the yen to appreciate, and addressing ‘structural impediments.’ To some extent this external pressure suited Prime Minister Nakasone’s own domestic agenda, and it set in motion the unraveling of the postwar system. The Reagan-initiated Plaza Accord of 1985 led to a steep appreciation of the yen, the fiscal and monetary responses to which ultimately created a massive asset bubble, which the Bank of Japan (BOJ) belatedly popped in late 1989.Footnote11 Japan was plunged into a recession which was deepened by further BOJ prevarication. As the cumulative effects of plunging asset prices surged through the financial sector, including housing loan corporations (jūsen), the ‘convoy system’ began to fray, and in 1997 a full-blown financial crisis emerged. Politically, Japan was unsettled by scandals, ending in 1993 the Liberal Democratic Party’s long single party reign, and growing criticism of bureaucrats, especially of the Ministry of Finance.

As confidence in Japan’s postwar model plummeted, the resurgent U.S. actively promoted its neoliberal solutions, including financial de-regulation and investor-favouring corporate governance. Japan responded with regulatory reform, an ill-timed financial ‘Big Bang,’ and separation of the BOJ from the Ministry of Finance. Regulatory reform enabled corporate restructuring, the unpicking of protective postwar labor legislation, and changes to corporate governance. As it slipped into deflation, Japan appeared to be on the way to dismantling its postwar system in favor of neoliberal market solutions.

Not quite. The dotcom bubble burst and Enron scandal of 2001 took the luster off the new US model, and while PM Koizumi did pursue a neoliberal agenda, the public became increasingly alarmed about growing inequality. The fall from grace of flamboyant financial entrepreneur Horie Takafumi along with Murakami Yoshiaki in 2006, and the ‘Lehman Shock’ of 2008, arguably marked a turning point of the visible neoliberal tide in Japan.Footnote12 State-market relations were thus shifting, contested, and unsettled.

At the company level, after restoring their balance sheets, companies built up massive internal reserves, aided by cuts to the corporate tax rate. While the stock prices of large companies were kept buoyant, aided by BOJ purchases, the companies themselves invested abroad, or began to repurchase their own shares to raise returns on investment. Households, on the contrary, were hit by stagnant wages, increased employment precariousness and no returns on their savings. In a bifurcated labor market, ‘non-regular’ employment rose steadily to over 35% by the mid 2010s, and 40% by 2020. Not even a tightening labor market could reverse the decline in labor’s share of value added. Thus in some respects the conversion narrative is apt, however as Kurosawa (Citation2020) points out, a much greater proportion of household finances than in the US or even Europe continued to be held in the form of cash or deposits with banks, and as in Europe, companies maintained their relations with banks and bank loans; financialization was thus partial.

We must also consider organization-technology dynamics, our second visual dyad. If one industry encapsulates Japan’s spectacular rise and subsequent fall in the face of a changing external environment, it is semiconductors. The success of the government’s VLSI (very large scale integration) project in the 1970s created the technological foundations for Japanese companies – notably giants Hitachi, Toshiba, NEC and Fujitsu – to dominate the global semiconductor memory (DRAM) market by the mid 1980s. Their fall was equally rapid; a decade later, the semiconductor divisions of these companies were making huge losses, and ceding market share, mainly to competitors from South Korea. Yunogami (Citation2006, Citation2021) notes that Japan’s DRAM production was premised on use in mainframe computers, which required an extremely high level of quality. The giants failed to adjust to the shift to PCs in the 1990s, with less demanding memory chips which could be produced much more cheaply, a fact seized upon by Micron Technologies in the US and emerging South Korean producers. At the level of final product assembly Japanese producers also failed to respond to the new outsourcing and Taiwanese foundry model (Sturgeon Citation2007), and to the rapid diversification of semiconductor types required to support the multiplication of functions users were performing on computers. A succession of government projects and consortia if anything made the situation worse rather than better, according to Yunogami. Today, Japan’s remaining semiconductor strengths mostly reside specialist companies rather than the giants which once dominated the industry.

Across the ICT sector as a whole Japan lost ground, struggling to adapt to the (less quality stringent) TCP/IP internet protocol (Cole Citation2006), and indeed the growing importance of software in product and organization design (Cole and Nakata Citation2014).Footnote13 And Japanese companies were slow to appreciate the implications of platforms, and their ‘winner-take-most’ potential in unregulated and globalized markets. To be sure, as Schaede (Citation2020) argues, Japanese companies strategically repositioned, claimed strategic niches in advanced equipment and materials, and underwent organization renewal. And throughout, Japanese companies remained dominant in automobiles, where monozukuri strengths are still critical, but this vital industry is now being challenged by the modularization and digitization that transformed the electric and electronic industries.

In brief, one source of Japan’s challenges from the 1990s was the flip-side of the strengths of its postwar productionist system – especially its successful resolution of employment and industrial relations tensions – which were bypassed in the new outsourcing production systems and technologies centered on Silicon Valley from the 1990s. This compounded the loss of institutional coherence and tensions in the state-market dyad. But Japan still has significant manufacturing strengths, and its balance of payments has remained positive throughout its secular stagnation. Its goods surplus has largely disappeared, but it has been replaced by returns from investments abroad (primary income), signaling an underlying shift in the structure of the economy.

Beyond secular stagnation: a new future?

Most studies of the contemporary Japanese economy end around about here, with Japan stuck in secular stagnation, and a loss of institutional and ideational coherence. Firm-level studies point to hybrid governance (Aoki Citation2007), while macro-economic studies, especially those concerned with finance, dwell on ‘Japanization’ and export of the malaise to other countries (Ito Citation2015). Official publications suggest that Japan has become an ‘advanced country in terms of its challenges’ (kadai senshinkoku), that other countries are facing or will face as well. But in the past five years a number of developments have begun to coalesce which may mark the beginnings of a new form of institutional and ideational coherence which is quite distinct from that of the postwar period. It may well be that Japan’s social institutions are ill-suited to the revolutionary phase of Schumpeterian technological innovation, but come into their own as a balancing phase, which may be starting to take shape (cf. Lechevalier Citation2019).

These developments are associated with Japan’s digital and green economic transitions, and are as yet mainly expressed as ideas, visions and policies; institutional change will take longer. Could they point to a reorientation toward a more sustainable future, which combines both wealth and wellbeing? We represent this possibility with the addition of ‘Society 5.0’ to the state-market dyad, and ‘digital transformation’ (DX) and ‘sustainability/green transformation’ (SX) to the organization-technology dyad (). The positioning of ‘Society 5.0’ indicates the possibility of a rebalancing of state-market relations, with the reinvigoration of industrial policy (although not in its postwar form) and new forms of state-market interaction. The positioning of DX and SX indicates a new focus of corporate innovation and entrepreneurship, management and organization transformation. Together, they indicate the possibility of a new type of macro-micro interaction, and institutional and ideational coherence. Of course digital and green transformations in themselves may create new institutional and ideational tensions, but let us examine how they are unfolding in practice.

‘Society 5.0’ was first articulated in the 5th Science and Technology Basic Plan of 2016. It has been defined as ‘a sustainable, human-centered society in which the physical and cyber worlds are highly integrated by digital transformation, no one is left behind, and everyone works together to create safe and comfortable lives and new growth opportunities,’ or ‘a sustainable, human-centered society created through digital transformation’ for short (Keidanren and Tokyo University and GPIF Citation2020). Its origins reflect a shift in thinking about science, technology and innovation policy, from a ‘technology-driven’ to a more ‘society-centered and challenge-driven’ approach, prompted at least in part by the triple disaster of 2011 (Carraz and Harayama Citation2019). It was Japan’s attempt to steer a path to a digital society which is different from the market-oriented Silicon Valley approach on the one hand, and China’s state-dominant approach on the other.Footnote14 In this respect it might be at the forefront of a ‘balancing’ phase of development, rather than a Schumpeterian laggard.

It is possible to dismiss Society 5.0 as empty rhetoric, as something Japan came up with in response to the clamor around the ‘fourth industrial revolution,’ and Germany’s Industrie 4.0. As rhetoric, however, it has been effective in fostering debate and action toward digital transformation. The concept soon found its way into a wide range of government policy documents, as well as Keidanren’s policy documents, and even annual reports of individual companies. Hitachi and Tokyo University established a joint Society 5.0 research center.Footnote15

A related development has been the re-invigoration of industrial policy around the concepts of digital and green transformation. In 2018 a Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry METI-sponsored research group produced a ‘DX Report’ which warned that Japanese companies were heading for a 2025 ‘digital cliff,’ and that their legacy IT systems would start costing more to maintain than value they created.Footnote16 In fact, if unaddressed they would cost Japan ¥12 trillion a year from 2025, but if addressed, they would boost Japan’s GDP by ¥130 trillion by 2030. The report emphasized that DX entailed more than upgrading IT systems to carry on business as usual; it involved a whole-of-business transformation, including business models. METI followed this up in 2019 with a report called ‘DX Promotion Indicators and Guidance,’ which set out detailed quantitative measures for five levels of implementation, and a questionnaire for Boards of Directors to prompt high-level involvement in DX. Together with the Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) METI also set up a ‘DX stocks’ and ‘noteworthy DX companies’ scheme, recognizing 35 companies for the former and 21 companies for the latter designation in 2020.

Regarding green transformation, in 2020 the Japanese government committed Japan to carbon neutrality by 2050, and in 2021, to a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of 46 percent by 2030. Following the carbon neutrality announcement, in December 2020 a ‘Green Growth Strategy’ was published which, as the name suggests, insisted that green and growth are compatible (Naikaku kanbō et al. Citation2021). It proposed five industrial policy tools and fourteen ‘growth sectors’ to create a ‘virtuous cycle of economy and environment.’ The fourteen sectors, which span energy, transport and manufacturing, and home and office, each had action plans and road maps, which envisage the policy tool mix changing according to the phase.

Japan has a long way to go in its green transformation in terms of renewable energy share in the power mix, but as DeWit (Citation2020) suggests, a more comprehensive set of indicators which include the circular economy, waste reduction, resource efficiency and resilience measures, suggest a more positive picture. They point to a gradual joining up of government policy, and the incorporation of sustainability and resilience into the Society 5.0 narrative, which marks a considerable shift from the neoliberal rhetoric of freeing up markets from excessive regulation. On the other hand, the DX and SX shifts do often conflict with existing regulations, and hence are promoted under special zone measures organized by the Cabinet Office. The need for innovation in governance – or ‘agile governance’ – for Society 5.0 has been identified in a number of METI reports.

Digital and green transformation, and corporate governance

Company-level digital and green transformation are diverse, but have accelerated since 2016, at least in leading companies. The automobile industry, which is vital for the Japanese economy, is currently undergoing multiple upheavals, summarized as ‘CASE’ (connected, autonomous, shared/subscription, and electric). Toyota’s shift from automobile manufacturer to ‘mobility company’ began to take shape in 2018 with its e-Palette ‘mobility services platform.’ The same year it established the Toyota Research Institute-Advanced Development (TRI-AD) to develop CASE-related software, as well as an ‘open vehicle programming’ software platform called Arene. TRI-AD was renamed Woven Planet Holdings in 2020, which is leading the development of Woven City, a smart city near Mt Fuji. In re-orienting itself, Toyota has entered into a vast number of alliances, with other automobile makers, as well as IT companies and service providers, which are reshaping and changing the boundaries of a once clearly defined industry.

Electronics is another key sector, which struggled in the 1990s and 2000s, as we have seen. Hitachi was emblematic of this struggle, but it gradually rebuilt its businesses, and in recent years has accelerated its digital and green transformation with a similar combination of a platform and alliances, as well as acquisitions and diverstitures. It’s platform is called Lumada, unveiled in 2016 to deploy ‘business domain knowledge, co-creation and digital technologies to resolve social and management issues.’ Like Toyota, this platform combines cyber and physical systems (as envisaged in Society 5.0), meaning it retains manufacturing and combines it with IT, which is quite different from the Silicon Valley approach. In terms of its green transformation, Hitachi’s goal is to become carbon neutral by 2030, and throughout its supply chains by 2050, through a combination of investment, visibilizing and optimizing energy use and emissions, and an internal carbon pricing mechanism.Footnote17

A third, critical sector which is also currently undergoing rapid change is finance, where a new generation of fintech startups is being enabled through the opening of banks’ application programming interface (API), and Big Data. New legislation seeks to promote such innovation, while maintaining stability and depositor protection. Despite such developments in key sectors, there has been a growing within-sector gap between leading firms and stragglers in terms of innovation, which alongside growing labor market inequality Lechevalier and Monfort (Citation2018) attribute much of Japan’s inability to restore growth to.

There is insufficient space to explore company-level DX and SX changes in any detail. We do need to consider, however, a parallel set of developments, in corporate governance, as they have a direct bearing on whether Japan has in fact embarked on a new path, as well as on institutional coherence. In 2014, as part of the Abe administration’s attempts to make Japan more attractive for foreign investors, the Financial Services Agency (FSA) published ‘Principles for Responsible Investors (Japan’s Stewardship Code).’ It was intended to put pressure on hitherto silent fund managers to engage in ‘purposeful dialogue’ over medium- long-term ‘corporate value creation’ and ‘sustainable growth.’Footnote18 A subtext was increasing return on equity (ROE), although not necessarily ROE maximization. By the end of August 2014, 160 institutional investors had signed up to the code.

The second prong of this strategy was a Corporate Governance Code, issued in 2015, which exhorted Boards to engage constructively with investors. The code set out principles rather than rules, coupled with a ‘comply or explain’ requirement. It required at least two independent non-executive directors, aiming to strengthen meaningful external voice. The code was revised in 2018, accompanied by ‘Guidelines for Investor and Company Engagement,’ covering amongst other things CEO appointment/dismissal and responsibilities of the Board. Both codes, and the guidelines, were further revised in 2020 and 2021 in anticipation of the 2022 Tokyo Stock Exchange (TSE) reorganization into Prime, Standard and Growth sections, with stricter profitability, and reporting requirements.

Against this background of increased investor engagement, in 2015 the GPIF, then the largest holder of Japanese stocks, signed up to the UN Principles of Responsible Investment. It soon began to formalize its ESG (environment, society and governance) principles for the managers of its funds. In 2017 and 2018 it selected five ESG indexes for them to consider when making investment decisions. It, too, insisted on the compatibility of ESG investment and profitability, arguing that ‘skeptics… should realize that they are quickly becoming the minority.’Footnote19 By 2022 all companies listed on the Prime section of the TSE will be required to report on emissions and environmental impact and risks, in line with the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) criteria.

In sum, in the space of a few short years since 2014, through the two-pronged Stewardship and Corporate Governance Code strategy, investor relations and reporting requirements for listed companies have been both tightened and expanded, representing an unprecedented intervention in corporate governance. They have created a new set of normative expectations – that companies should generate a higher level of return on equity than the past, but also that they should engage in ESG, which is also being tightened up to include supply chains, and increasingly diversity and other ‘social’ criteria. They also place the normative expectation on investors to engage with their investee companies, based on mid- to long-term ‘corporate value’ creation rather than short term profit.

The assertion that profit and sustainability are compatible is also made in Keidanren’s 2020 ‘NEW Growth Strategy,’ which presents a ‘future vision for 2030’ that will ‘bring together the wisdom of diverse stakeholders and establish sustainable capitalism with Society 5.0, which co-creates diverse value through DX.’Footnote20

Institutional coherence and institutional hierarchy

It appears, then, that under the banner of Society 5.0 Japan has set a new economic path which combines digital and green transformation, asserting their compatibility, and compatibility with growth and profit making. Urgency is fanned by pointing to the danger of Japan falling behind other countries, alarm which is amplified by the Nikkei newspaper and other media. Target dates − 2050, 2030, 2025 – and action plans, road maps and milestones are set which, whatever else they achieve, have already had some success in orienting economic actors toward the future, and generating a level of ideational congruence.

But there is a potential contradiction in these developments. The Society 5.0 vision claims to be ‘people-centric,’ and to address social needs through technology and innovation. Keidanren cites ‘workers’ as one of its five stakeholders, alongside consumers, local communities, the environment and the global community. Its NEW Growth Strategy only mentions shareholders and investors once. Yet the ever-increasing demands being placed on managers, not just to deliver returns for investors, but to demonstrate ESG compliance through integrated reports and participating in green indexes, and to dispose of mutually held shares, has a different sub-text. Intentionally or unintentionally, it privileges investors as central arbitors of both digital and green transition, attributing to them discernment of long-term corporate and social value, even as it ostensibly places limits on investor greed.

‘People’ in Society 5.0 appear to have the role of surfacing problems, and benefiting from their technological solutions. Workers in Keidanren’s NEW Growth Strategy ‘will command digital technologies with rich imagination and creativity and will create value through flexible work styles that are not confined by time or space.’ But they won’t necessarily be participating in decisions concerning corporate strategies or building Society 5.0. Asserted to be central, ‘people’ and ‘workers’ may in fact be marginalized.Footnote21

An important part of the postwar model was the stake in economic growth it offered to blue collar workers, of prospects for a better future. Secular stagnation has seen those prospects dim, especially for significant portions of the 40 percent of the workforce who are now employed as ‘non-standard’ workers. It is not clear what transformation will offer them, apart from flexible working, or how inequality and social divisions will be addressed, other than by ‘trickle down.’ Shibata (Citation2021), for example, offers a pessimistic view of digitalization in Japan and its impact on work, seeing it as an extension of neoliberal labor market flexibilization.

This brings us back to the Régulationist insight about institutional hierarchies: if the wage-labor nexus (industrial/employment relations) was central to the postwar Fordist – and Japanese productionist – regime, what will be central in this nascent regime? Currently it appears to be an investor-company director/entrepreneur nexus (investor relations), and the government-business nexus. What appears on the surface to be a decisive break with neoliberalism may in fact be partial. Time will tell whether this will be modified, possibly through new forms of civil society participation. And it remains to be seen whether PM Kishida’s ‘new capitalism’ and ‘growth with distribution’ agenda will bear fruit.

As we noted in Section 1, viable institutional configurations are seldom achieved by design; they emerge over time through diverse interactions and adjustments. Japan’s pursuit of digital and green transformation may, through a combination of design and trial and error, achieve a new, viable configuration. Demographics suggest it may not be readily visible in GDP growth figures – there is a need for new macro-level measures which incorporate wealth, wellbeing and sustainability to gauge progress.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Ian Neary, Timothy Sturgeon, two anonymous referees and the guest editors for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. Remaining faults are attributable to the author.

Notes

1 ‘Lost decades’ is not a helpful term. Much changed in Japan during the 1990s and 2000s, and there were extended periods of growth, albeit at a lower rate than the preceding decades. ‘Secular stagnation’ (as opposed to a business cycle downturn) partly fits, and while Japan is very different from the 1930s US, when Hansen (Citation1939) proposed the term, the breakdown of institutional complementarities depicted through the dyads of this paper links the two cases.

2 Kang and Moon assign South Korea and France to the SLME category, and Japan to the CME economy. However, Japan was Asia’s original ‘developmental state,’ and the state is playing a major role in Japan’s current transitions, as we shall see later in the paper. For an earlier, more extended view of institutional complementarity, see Boyer Citation1997.

3 The dyads derive from Whittaker et al.’s (Citation2020) comparative study of ‘Compressed Development,’ where they are elaborated more fully. Compressed Development has two main features – ‘compression’ or the tendency for processes which previously unfolded sequentially, over time, to be compacted into virtual simultaneity; and ‘era’ which refers to the influence of prevailing ideologies and institutions when countries become incorporated into the global economy and experience high growth.

4 As Weiss and Hobson (Citation1995, 4) put it, the modern state ‘gradually sought more institutionalized, cooperative relations with civil society, enhanced their penetrative and extractive capacities, and hence their infrastructural power.’

5 Sometimes, and in some respects, depicted as ‘liberal,’ it simultaneously prompted the development of ‘crustacean-like’ national institutions: Polanyi Citation1944; Desai Citation2021.

6 As J. K. Galbraith (Citation1967, 14) wryly noted: ‘The services of the Federal, state and local governments now account for between a fifth and a quarter of all economic activity. In 1929 it was about eight percent. This far exceeds the government share in such an avowedly socialist state as India… and is not wholly incommensurate with the share in Poland.’

7 The ‘three pillars’ were long-term/‘lifetime’ employment, nenkō wages and promotion, and enterprise unions. Blue collar workers were incorporated into the enterprise community, with substantial welfare entitlements for community members. ‘Japanese-style’ management also relied on a highly gendered social division of labour, and various categories of peripheral workers, who did not benefit from the ‘three pillars.’

8 As several writers (e.g. Block and Somers Citation2014) have pointed out, markets are always socially, institutionally and ideologically embedded, hence ‘dis-embedded,’ like ‘de-regulated’ is a misnomer (cf. Vogel Citation2018). Polanyi’s concept of embedding was deployed in Ruggie’s ‘embedded liberalism,’ referred to above.

9 Cf. also Dore (Citation2009) for the first view. The second view has been held by many who believed Japan should undertake root-and-branch ‘structural reform.’

10 Epstein (Citation2005, 3) defines financialization as ‘the increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of domestic and international economies.’ Globalization of finance was followed by a succession of financial crises, starting with Mexico in 1982.

11 Following the Plaza Accord in 1985 the Yen-Dollar rate surged from roughly ¥240: $1 to ¥160: $1 in less than a year later, and it kept climbing to ¥79: $1 in 1995.

12 Gotoh (Citation2020) depicts a struggle between neo-classical economists, Keizai Doyukai (Japan Association of Corporate Executives), non-Japanese firms and US credit rating agencies, which were ascendant from the 1990s until the early 2000s, and interventionist bureaucrats, anti-free market politicians, Keidanren (Japan Business Federation), banks, legal elites and Japanese credit rating agencies, who regained ascendance in the mid 2000s.

13 From 2000 to 2011 Japan’s production of electronics products declined by 50 percent, and exports by 37 percent: Cole and Nakata Citation2014.

14 The state-market dichotomy here is misleading; see Zuboff (Citation2019) on ‘surveillance capitalism’ in the U.S.

15 Keidanren Chairman (and former Hitachi President) Nakanishi Hiroaki and Tokyo University President Gonokami Makoto were influential members of the S&T Policy Council which came up with the concept.

16 Keizai sangyō shō, Citation2018. The government was under pressure to carry out its own DX. Previous attempts in the early 2000s had failed, but in 2021 a Digital Agency was established in the Cabinet Office alongside the Cybersecurity Strategic Headquarters and National Security Council with its own budget and authority to draft legislation.

17 Nikkei Asia, 14 September, 2021 (‘Hitachi to Eliminate Greenhouse Gases From Supply Chain by 2050’).

18 https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/refer/councils/stewardship/20140407/01.pdf accessed 4 September, 2021, p. 2.

19 https://www.gpif.go.jp/en/investment/Our_Partnership_for_Sustainable_Capital_Markets.pdf accessed 5 September 2021.

20 https://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2020/108_proposal.html accessed 3 September 2021.

21 This is reminiscent of what researchers concluded about multinationals’ corporate social responsibility (CSR) codes of conduct 15 years ago: ‘codes of conduct are radically inconsistent with workers’ participation in the company. A concern for workers’ protection can be observed. But at the top of the hierarchy of values that the codes sketch out, there is the impersonal property of the company’ (Béthoux, Didry, and Mias Citation2007, 88). The codes were effectively substituting for workers’ participation and social rights.

References

- Amsden, A. 2007. Escape from Empire: The Developing World’s Journey through Heaven and Hell, Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Aoki, M. 2007. “Conclusion: Whither Japan’s Corporate Governance.” In Corporate Governance in Japan: Institutional Change and Organizational Diversity, edited by M. Aoki, G. Jackson and H. Miyajima, Ch. 15, 427–448. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Béthoux, É., C. Didry, and A. Mias. 2007. “What Codes of Conduct Tell Us: Corporate Social Responsibility and the Nature of the Multinational Corporation,’.” Corporate Governance: An International Review 15 (1):77–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2007.00544.x.

- Block, F., and M. Somers. 2014. The Power of Market Fundamentalism: Karl Polanyi’s Critique, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bodrožić, Z., and P. Adler. 2018. “The Evolution of Management Models: A Neo- Schumpeterian Theory.” Administrative Science Quarterly 63 (1):85–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839217704811.

- Boyer, R. 1997. “The Variety of Institutional Arrangements and Their Complementarity in Modern Economies.” In Contemporary Capitalism: The Embeddedness of Markets, edited by R. Hollingsworth and R. Boyer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boyer, R. 2005. “‘Complementarity in Regulation Theory,’ in ‘Dialogue’ on Institutional Complementarity and Political Economy.” Socio-Economic Review 3:359–382.

- Campbell, J. 2011. “The US Financial Crisis: Lessons for Theories of Institutional Complementarity.” Socio-Economic Review 9 (2):211–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwq034.

- Carraz, R., and Y. Harayama. 2019. “Japan’s Innovation Systems at the Crossroads: Society 5.0.” Panorama: Insights into Asian and European Affairs, January 1:33–45.

- Cole, R. 2006. “The Telecommunication Industry: A Turnaround in Japan’s Global Presence.” In Recovering from Success: Innovation and Technology Management in Japan, edited by D. H. Whittaker and R. Cole. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cole, R., and Y. Nakata. 2014. “The Japanese Software Industry: What Went Wrong, and What Can We Learn from It?” California Management Review 57 (1):16–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.57.1.16.

- Desai, R. 2021. “Commodified Money and Crustacean Nations.” In Karl Polanyi and Twenty First Century Capitalism, edited by R. Desai and K. Polanyi Levitt. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- DeWit, A. 2020. “Is Japan a Climate Leader? Synergistic Integration of the 2030 Agenda.” The Asia-Pacific Journal/Japan Focus 18 (2):1–21.

- Dore , 1987. Taking Japan Seriously: A Confucian Perspective on Leading Economic Issues. London: Athlone and Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Dore, R. 2009. “Japan’s Conversion to Investor Capitalism.” In Corporate Governance and Managerial Reform in Japan, edited by D. H. Whittaker and S. Deakin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Epstein, G. 2005. “Introduction.” In Financialization and the World Economy, edited by G. Epstein. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Galbraith, JohnK. 1967. The New Industrial State. Boston MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Galbraith, JamesK. 2008. The Predator State: How Conservatives Abandoned the Free Market and Why Liberals Should Too. New York: Free Press.

- Gotoh, F. 2020. Japanese Resistance to American Financial Hegemony: Global versus Domestic Social Norms. London: Routledge.

- Hall, P., and D. Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hansen, A. 1939. “Economic Progress and Declining Population Growth.” American Economic Review 29 (1):1–15.

- Ito, T. 2015. “Japanization: Is It Spreading to the Rest of the World?” In Economic Stagnation in Japan: Exploring the Causes and Remedies of Japanization, edited by D. Cho, T. Ito and A. Mason, 17–55. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Johnson, C. 1982. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925–1975, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Kang, N., and J. Moon. 2012. “Institutional Complementarity between Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility: A Comparative Institutional Analysis of Three Capitalisms.” Socio-Economic Review 10 (1):85–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwr025.

- Katz, R. 1998. Japan, the System That Soured: The Rise and Fall of the Japanese Economic Miracle. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

- Keidanren. 2020. Shin Seichō Senryaku. Tokyo: New Growth Strategy.

- Keidanren, Tokyo University and GPIF. 2020. “The Evolution of ESG Investment, Realization of Society 5.0, and Achievement of SDGs: Promotion of Investment in Problem-Solving Innovation.”

- Keizai sangyō shō. 2018. “DX repōto: IT shisutemu ‘2025 gake’ no kuppuku to DX no honkakuteki na tenkai’ (Report on DX [Digital Transformation]: Overcoming the ‘2025 Digital Cliff’ Involving Digital systems and Full-Fledged Development Efforts for DX.” Tokyo.

- Kurosawa, Y. 2020. “Nihon Keizai: Teitai no 30 nen no gen’in – chōwa ga torenai baburu hōkaigo no keizai no shikumi (‘The Japanese Economy: Causes of 30 Years of Stagnation’).” In Toshika kenkyū kōshitsu Rondan, Vol.12: 1–8.

- Lechevalier, S. 2014. The Great Transformation of Japanese Capitalism. London: Routledge.

- Lechevalier, S. 2019. “Innovation Beyond Technology - Introduction.” In Innovation Beyond Technology: Science for Society and Interdisciplinary Approaches, edited by S. Lechevalier. Berlin: Springer.

- Lechevalier, S., and B. Monfort. 2018. “Abenomics: Has It Worked? Will It Ultimately Fail?” Japan Forum 30 (2):277–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2017.1394352.

- Milberg, W. 2008. “Shifting Sources and Uses of Profits: Sustaining U.S. Financialization with Global Value Chains.” Economy and Society 37 (3):420–451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03085140802172706.

- Minsky, H. 1992. “Schumpeter and Finance.” In Market and Institutions in Economic Development: Essays in Honour of Paulo Sylos Labini, edited by S. Biasco, A. Roncaglia and M. Salvati. London: MacMillan.

- Naikaku kanbō (Cabinet Secretariat) plus 8 ministries and agencies. 2021. ‘2050 nen kābon nyūtoraru ni tomonau gurīn seichō senryaku’ (Green Growth Strategy Through Achieving Carbon Neutrality in 2050), Tokyo.

- Noguchi, Y. 1998. “The 1940 System: Japan under the Wartime Economy.” The American Economic Review 88 (2):404–416.

- Polanyi, K. 1944. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. New York: Farrar and Rinehart.

- Ruggie, J. 1982. “International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the Post-War Economic System’.” International Organization 36 (2):379–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300018993.

- Schaede, U. 2020. The Business Reinvention of Japan: How to Make Sense of the New Japan and Why It Matters. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Shibata, S. 2021. “Digitalization or Flexibilization? The Changing Role of Technology in the Political Economy of Japan.” Review of International Political Economy 2021:1–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2021.1935294.

- Sturgeon, T. 2002. “Modular Production Networks: A New American Model of Industrial Organization.” Industrial and Corporate Change 11 (3):451–496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.3.451.

- Sturgeon, T. 2007. “How Globalization Drives Institutional Diversity: The Japanese Electronics Industry’s Response to Value Chain Modularity.” Journal of East Asian Studies 7 (1):1–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1598240800004835.

- Tsutsui, W. 1998. Manufacturing Ideology: Scientific Management in Twentieth-Century Japan. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Vercelli, A. 2013. “Financialization in a Long-Run Perspective’.” International Journal of Political Economy 42 (4):19–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/IJP0891-1916420402.

- Vogel, Stephen. 2018. Marketcraft: How Governments Make Markets Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weiss, L. and J. Hobson. 1995. States and Economic Development: A Comparative Historical Analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Whittaker, D. H., T. Sturgeon, T. Okita, and T. Zhu. 2020. Compressed Development: Time and Timing in Economic and Social Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yunogami, T. 2006. “Technology Management and Competitiveness in the Japanese Semiconductor Industry.” In Recovering from Success: Innovation and Technology Management in Japan, edited by D. H. Whittaker and R. Cole. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Yunogami, T. 2021. “Nihon no handōtai buumu wa ‘nisemono’: Honki no saisei ni wa gakkō kyōiku no kaikaku ga hitsuyō da” (Japan’s Semiconductor Boom is Fake: For Real Recovery School Education Reform is Needed) in EE Times Japan, 22 June https://eetimes.itmedia.co.jp/ee/articles/2106/22/news042.html, accessed 1 July, 2021.

- Zuboff, S. 2019. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. London: Profile Books.