Abstract

The subject of this paper is a macroethical, nonclassroom ethics education experience on the topic of human enhancement, encompassing the spectrum from therapy to alteration beyond observed natural bounds, offered by the lead author as embedded educator and investigator. It reports the research results of a pre- and post-intervention (group viewing of the documentary film FIXED) survey administered to faculty investigators and doctoral students directly involved in research pertaining to biologically inspired future computer architectures applied to devices interfacing with humans. Taken together, initial participant responses reflect normative discrimination in evaluating aims and outcomes of technological interventions on the spectrum of body modification possibilities. Responses to individual survey items and factor analysis reveal the impact of viewing FIXED on innovator thinking about ethical and societal issues surrounding human enhancement, including the ways human attributes are valued and personal outlook on life in the context of prospective physical disability.

1. Introduction and background

1.1. Macroethics education for STEM practitioners

Recent innovations in ethics education approaches for scientists and engineers have tended toward unprecedented integration, embedded formats, and nonclassroom environments (Fisher et al. Citation2010; May and Luth Citation2013). In this way, the format and content of education mutually reinforce the concept that ethics is not a subject separate from research, or a neatly compartmentalized and administrative component of laboratory management, but something inextricably interwoven through every strand, area, and layer of practice (Harris et al. Citation1996). This conceptual grasp is the foundation of a mature commitment to participation in the broader societal enterprise of responsible technological innovation. Microethical or Responsible Conduct of Research approaches, while valuable in conveying particular knowledge objectives of ethics instruction (Newberry Citation2004), are inherently insufficient to facilitate holistic understanding and competency related to responsible technological innovation. Thus, ethics education for scientists and engineers – including the research and pedagogy reported in this article – has expanded in scope from an emphasis on acts of wrongdoing by individual researchers to the societal level (Herkert Citation2005) – extending across geographical, temporal (including future-orientation), and cultural diversity.

1.2. Human enhancement and disability, relevance both professional and personal

Technological innovators, however focused in work on esoteric details within the realm of inanimate materials, are citizens of laboratory/professional communities and the societies in which they live. As such, their scientific and engineering work occurs in the context of the broader societal status quo in parts of the world where advanced research is pursued, technologically advanced nations where the increasing role of direct interaction with electronic devices in everyday life is observable and directly experienced in nonprofessional contexts. Questions about the possible trajectories, proper limits, and meanings of technologically based change on human life are being debated in real-time, in every social sphere including religious organizations (Hughes Citation2012; Lustig Citation2008). As such, they are primed for thoughtful consideration of normative questions surrounding human enhancement, regardless of prior familiarity with transhumanist philosophies (Bostrom Citation2005; Kurzweil Citation2006), vehement and uncategorical bioconservative objections to them (Fukuyama Citation2002; Kass Citation2002), or the middle ground of ‘truly human’ moderate enhancements as permissible and prudential (Agar Citation2013).

Whether explicitly articulated or not, the distinction between therapy and enhancement is the crux of a range of current debates and controversies, such as the use of performance-enhancing substances by athletes, so-called designer babies, and cosmetic neuropharmacology. Both therapies and enhancements intervene with a human body's present state, improving functionality. Therapies, as commonly understood, address a pathological condition or need toward restored health or species-typical functioning. A specific intervention with the human body may be considered an enhancement when the goal or end result is a better-than-well or superhuman state. In some cases, clearly making the morally significant distinction between therapy and enhancement at a murky middle point along the spectrum between them can prove difficult for individuals, and may become even more challenging at the societal level due to varying moral and cultural norms about health and wellness among constituents (Resnik Citation2000).

Increasing technological pervasiveness into self-care generally has implications for societal norms about the handling of disability: ‘when your whole society is relying on technological tweaks and boosts, then your own ventilator or anti-psychotic drugs or power chair perhaps becomes less noticeable, more acceptable’ (Shakespeare Citation2014, ix). Phenomena related to ethical and societal dimensions of disability – such as global aging (Longman Citation2010), income inequality (Reich Citation2010), and amputees surviving recent violent conflicts and acts of terrorism (Weaver, Smith, and Fleisher Citation2013) – are prominent in public discourse. The aim to impart physical functionality on humans is common to the research projects represented by participants in this study. Per their project websites (as of 8 December 2014), the CONTEST (COllaborative Network for Training in Electronic SkinTechnology) project aims to ‘trigger transformations in diverse sectors such as healthcare and robotics’ and OLIMPIA strives to ‘impact a wide variety of fields, from biomedical research, to neuro-regenerative medicine’.

1.3. Multidimensional learning at the human–computer interface

Most attendees of the jointly organized summer school were associated with the CONTEST or OLIMPIA training initiatives funded by the European Commission related to electronic sensors, system integration, and robotic technologies. CONTEST is a multi-site initial training network (ITN) funded by European Commission directed toward flexible, wearable ‘smart skin’. OLIMPIA's topical focus is the integration of organic optoelectronics and neural cells. Both of these research frontiers involve an ultimate aim of a direct human-mechanoelectronic interface that imparts functionality to the user, a descriptor that pertains to revolutionary therapies and inherent potential for human enhancement use. Surveys were administered in the context of the summer school to explore two areas of investigation. First, the survey was designed to probe the normative thinking of researchers engaged in relevant fields on the topic of human enhancement. The study has a pre-post design, where the intervention was viewing of the documentary film FIXED in the context of the joint summer school. Thus, the second area of investigation is about the impact of this film, provoking thought about human enhancement and disability from diverse perspectives, as a potential tool for macroethics education, raising questions that stimulate critical, nuanced thought related to the types of innovations their research is driving toward.

2. Methods

2.1. Survey

The survey instrument for this study was designed and refined in collaboration with the University of Notre Dame's Center for Social Research, to reflect best practices in social scientific data collection. The study, formally approved by the University of Notre Dame's Institutional Review Board, took place 27–28 May 2014 at the Fraunhofer Research Institution for Modular Solid State Technologies in Munich, Germany, in the context of the Joint Summer School of the Projects CONTEST – OLIMPIA – EAGER on System Integration. The survey was administered pre- and post-intervention, where the intervention constituted viewing of the 2013 documentary film FIXED: The Science/Fiction of Human Enhancement (produced and directed by Regan Pretlow Brashear, New Day Films, copyright Making Change Media). In addition to demographic information, the survey questions fell into two major sections. The first section contained normative questions about the goals of human enhancement, asking whether technologies applied to the human body should provide changes ranging from those constituting therapy to radical enhancements. The second section asked about the different ways society values humans and two questions about life outlook – in general, then in the event of a severe spinal cord injury. These two categories were selected because the film raised issues about human enhancement specifically as well as general questions about the societal context in which human enhancement technologies are being pursued and disability is experienced.

2.2. Context: a joint summer school

The viewing took place in the context of a summer school, jointly organized by the two participating research initiatives funded by the European Commission, CONTEST and OLIMPIA, and one project funded by the United States National Science Foundation (US NSF), EAGER: Computer Architectures for 2020 and Beyond, for which the lead author is a Co-Principal Investigator for ethical and societal dimensions. Technical talks were provided by the other two organizations (CONTEST and OLIMPIA) of the joint school. In addition to the viewing of FIXED, with the related survey research and wrap-up discussion, the EAGER project contributed three lectures pertaining to ethical and societal dimensions to students and faculty at the school: (1) ‘Brain-inspired Computing Philosophy: From Vision Systems to Cyberphysical Systems’ by Klaus Mainzer of the Technical University of Munich; ‘Robot Ethics’ by Don Howard of the University of Notre Dame; and ‘Material Enhancement: From dead matter to smart environments’ by Alfred Nordmann of the Technical University of Darmstadt. It should be noted that the lectures related to ethical and societal dimensions of technological innovation were interspersed throughout the schedule – one per day, with different start times – and were plenary. This stands in contrast to the scheduling of event content related to ethical and societal dimensions in breakout sessions, contiguous blocks, and/or limited to the final day of a multi-day event, practices associated with diminished overall attendance and a low degree of disciplinary diversity.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

Pre- and Post-surveys were administered online through Qualtrics. The interval between pre-and post-tests spanned just one day; a one-day span was selected due to the short duration of the summer school event, and the study design preference to collect responses after an overnight (to allow for private reflection), yet while the film experience was still fresh in participants' minds. The pre-test was administered at 2:00 PM on 27 May 2014, immediately followed by the screening of the film. The post-test was administered the following day, 28 May 2014 at 11:35 AM. Analyses were conducted using the [psych] package (Revelle Citation2014) and figures were generated with the [ggplot2] package (Wickham Citation2009), both in [R] (R Core Team Citation2014). Responses were subjected to factor analysis. Each section of questions was analyzed with exploratory factor analysis using Promax (oblique) rotation. Furthermore, reliability (Cronbach's α) was assessed for both pre- and post-test questions. Each section across pre- and post-tests was found to have unidimensional factor structures and were of adequate reliability for making comparisons. Individual scores were obtained by computing Bartlett factor scores. Bartlett scores are frequently used because they provide unbiased estimates of the true score (Hershberger Citation2005).

2.4. FIXED as strategic intervention

The film FIXED, produced and directed by Regan Pretlow Brashear, is a recent work, copyright 2013 by Making Change Media. The documentary film is a blend of archival footage, interviews, observational cinema, and segments of performances by integrated dance companies featuring disabled and nondisabled dancers. The film's value as a research and teaching tool for higher education is described on its website (as of 5 December 2014) through a tab designated for educators, listing diverse disciplines including those represented by the participants in this study – Bioengineering, Genetics, Neuroscience, and Biomechatronics. This film was selected as a means for this particular educational experience and research study because it provides a whirlwind showcasing of diverse human perspectives, including technological experts such as Hugh Herr of MIT, on questions of what it means to technologically modify the human body, for both therapeutic and enhancement purposes. FIXED explores the ethical and societal issues surrounding these interventions, probing individual self-understandings and social tensions related to ability and disability, normalcy, and the body. These considerations ripple out to the eponymously begged questions about what we are trying to fix, and what really needs to be fixed, toward reflection about the myriad individual and societal wounds related to merely conditional regard for the value of human life. The objectives for ethics education include both intellectual engagement and emotional engagement (Newberry Citation2004). The interviews in the film, including multiple persons with disabilities, are direct and personal, delivering through the media of film an intimacy that allows for empathy and perspective taking in receptive viewers. Empathy and perspective taking experiences are key components for moral development, long considered essential for moral sensitivity and moral behavior (Rest Citation1986); perspective taking is classically considered the foundation of moral judgment development (Kohlberg Citation1984). More recent research has demonstrated a correlation between high levels of empathy/perspective taking and the confrontation of socio-cognitively complex ethical dilemmas (Myyry and Helkama Citation2007). Technological innovators, particularly where human modification is concerned, face dilemmas of staggering complexity. Thus, the facilitation of empathy and perspective taking by the candid testimonials in FIXED is considered as a strategic asset in providing fitting macroethics experience among scientists and engineers.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

All participants were attendees of the Joint Summer School of the Projects CONTEST – OLIMPIA – EAGER on System Integration; as such, each is considered by the author to have demonstrated a high level of interest and involvement in technological innovation with a human–electronic dimension. Diverse in multiple respects, the 26 participants in this study include faculty (11) and students (14); female (7) and male (18); technical (21) and nontechnical (4) disciplines; and aged 24–58 years. Eleven different nationalities were represented, including Estonia (1), France (1), Germany (4), India (2), Iran (1), Italy (9), Pakistan (1), Spain (1), Switzerland (1), Turkey (1), and the USA (3). (Totals do not sum to 26 due to nonresponses on individual questions.)

3.2. Limitations

The small sample size (N = 26) of this study precludes many types of statistical analysis and limits the scope of reasonable interpretation, especially with respect to generalizability. Results cannot be discussed with respect to effect sizes, confidence intervals, estimates, or the like, as there was insufficient power for finding even large effect sizes. Despite these limitations, the data collected in this study allow for visual exploration, including the observation of interesting trends. Although the diversity of the sample may be a drawback for analysis with respect to subdivision into exceedingly small subgroups, its inclusivity is appropriately representative of this specialized population of technological innovators at the biological–mechanical interface. Likewise, the ways the sample is not diverse, such as a uniformly high level of formal education, are inherent to the participants in the study by design.

3.3. Therapy versus enhancement, initial perspectives

Though not mutually exclusive and ultimately ambiguous descriptors of interventions improving some aspect of human functionality, there is a descriptive difference between therapy and enhancement that allows for a conceptual spectrum from what would qualify as therapy, but not enhancement to what would qualify as enhancement, but not therapy. Study participants were presented a conceptual therapy-enhancement spectrum through a series of related questions and asked to provide a normative judgment with five-point Likert response option formats. The survey items and pre-test response data are presented in . Not surprisingly, approval of therapy was unanimous, with most respondents strongly agreeing and the remainder agreeing. With incorporation of increasing elements of human enhancement (top to bottom on ), however, responses overall indicate a trend toward diminished approval and increased disapproval. On the four of the five items with any dimension or degree of enhancement, responses represented the full range from strongly disagree to strongly agree. While encompassing the tri-level range of therapy-enhancement alteration delineated for neuroscientific interventions (Jotterand Citation2008), phrasing the questions with five points along the spectrum as in achieves a pedagogical aim. This verbal presentation simultaneously raises the intertwined ethical issues of intention (Why is the body being changed in the first place?) and consequence (evaluation of the resulting state).

3.4. Impact of FIXED on human enhancement responses

‘In the future, the disabled may prove more abled; we may all want their prostheses’ (Kotler Citation2002). FIXED explicitly links prosthetics developed for the disabled and the realistic prospect of their desirability by the nondisabled as the means for enhanced functionality. (a) shows that factor scores with respect to human enhancement varied pre- and post-FIXED viewing. While some participants' responses shifted only modestly on the post-test, a majority exhibited a notable shift. The changes in factor scores were split between increasing and decreasing favorability (). Responses to individual questions are shown in (b), comparing pre-test and post-test responses. High levels of response shuffling pre- to post-test are evident on all four of the five items extending beyond therapy.

Figure 2. Changes in normative evaluations along human enhancement spectrum post-FIXED. (a) The dot plot indicates the change in factor scores from pre-test to post-test (post minus pre) for each person. Factor scores were obtained by performing an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with the items. Factor analysis generates a score based upon factor loadings for each item. Each circle represents one respondent and stacked circles indicate the same difference score. Values on the positive side of zero (i.e. to the right of the vertical line positioned at 0) indicate a shift toward favorability in assessment, while values on the negative side of zero indicate a decrease in agreement or approval, or an increase in concern. The density plot is shown as the line above the dot plot. (b) Survey question items with pre- versus post-test responses on left.

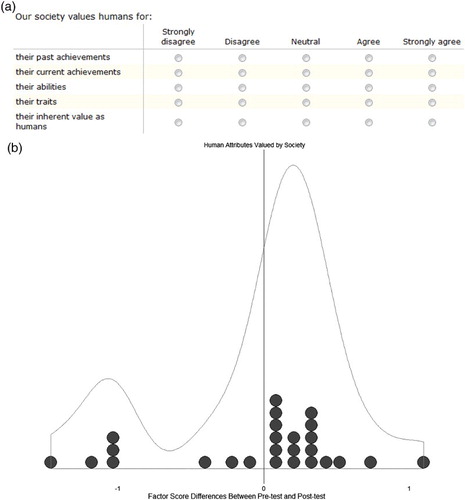

3.5. Impact of FIXED on responses about ways human attributes are valued by society

Through multiple interviewees, the film FIXED confronts the social reality of ‘ableism’ wherein persons are valued primarily for what they do, or can do, rather than who they are. Participants were queried about the ways society values humans on both pre- and post-test. The specific items – related to achievements, abilities, traits, and inherent value – are shown in (a). (b) displays the factor score differences with respect to the ways society values humans. Most respondents exhibited a modest shift in the positive direction, though as with human enhancement responses (), shifts in opposite directions were observed. The minority of respondents who came to view society's valuing of humans in a more negative light after viewing FIXED are represented by a distinct peak at −1 on the density plot of factor score differences shown in (b).

Figure 3. Technological innovator perspectives on ways society values humans, pre- and post-FIXED. (a) The query about the different ways society values humans is displayed as encountered by survey respondents. (b) The dot plot indicates the change in factor scores from pre-test to post-test (post minus pre) for each person. Factor scores were obtained by performing an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with the items. Factor analysis generates a score based upon factor loadings for each item. Each circle represents one respondent and stacked circles indicate the same difference score. Values on the positive side of zero (i.e. to the right of the vertical line positioned at 0) indicate a shift toward favorability in assessment, while values on the negative side of zero indicate a decrease in agreement or approval, or an increase in concern. The density plot is shown as the line above the dot plot.

3.6. Impact of FIXED on responses about prospective disability and outlook on life

In FIXED, scientist Gregor Wolbring demonstrates a positive outlook on life with a variation that impacts physical mobility. Born without legs, he chooses not to use prosthetic ones. In the context of “Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance: Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Information Technology, and Cognitive Science”, a report sponsored by the US NSF/DOC, Wolbring calls attention to studies revealing a major discrepancy between the observed self-images reported by spinal cord injury survivors (which closely resemble those of nondisabled respondents) and nondisabled respondents imagining themselves in the context of spinal cord injury (Gerhart et al. Citation1994; Wolbring Citation2003). FIXED provides a close up view of realities experienced by those with spinal cord injuries – with vivid visuals and clearly articulated statements – that allows viewers to form a more informed personal imagination of life in the hypothetical eventuality of severe physical disability. Intriguingly, the variety of experiences in these influential testimonials does not establish a single direction of heightened awareness. The inspirational achievement of Hugh Herr's return to mountain climbing is offset by hearing Patty Berne reveal that discomfort can rapidly set in when an electric wheelchair is malfunctioning, and that a sudden downpour of rain can strand her without a functioning chair. The moving beauty of the experience of Tim Hemmes touching his girlfriend's hand sharply contrasts with the ugliness of haunting, deeply offensive words attributed to the aunt of Dominika Bednarska. The potency of these experiences and the perspective taking afforded by them led to the hypothesis that viewing FIXED would impact responses to a question about one's life outlook in the event of spinal cord injury. On both pre- and post-tests, participants were asked to respond on a five-point Likert response option format, ranging from very negative to very positive, to the following two statements: ‘In general, my outlook on life is … ’ and ‘If I suffered a severe spinal cord injury, my outlook on life would be … ’. (a) shows that, consistent with expectations, most respondents self-reported a positive outlook on life and that viewing FIXED did not change that – only one respondent made a change between pre- and post-tests, a shift from very positive to positive. Responses regarding life outlook in the hypothetical case of severe spinal cord injury, shown in (b), reveal the expected shift toward negativity in the pre-test. Post-FIXED, the number who had responded with positive or very positive on the pre-test was maintained, as was the quantity who responded very negative. Shifts in responses about life outlook in the event of severe spinal cord injury were observed in the neutral and negative pre-test response categories, in both directions. Viewing each individual respondent's general outlook on life versus outlook on life in the context of hypothetical spinal cord injury, pre- and post-test, in (c), reveals that those with a positive or very positive general outlook on life varied broadly when considering the prospect of spinal cord injury, both before and after the viewing of FIXED.

Figure 4. Life outlook responses, general and in spinal cord injury context, pre- and post-FIXED. (a) Survey question about general outlook on life with pre- versus post-test responses. (b) Survey question about outlook on life in the event of severe spinal cord injury with pre- versus post-test responses. (c) Outlook on life responses, general versus spinal cord injury context. General life outlook responses are mapped onto named categories along the X-axis, while spinal cord injury context life outlook responses are coded according to the key on the right. Pre-test responses are shown at left, with post-FIXED responses shown on the right.

4. Discussion

The potential of technology to positively impact humanity is implicit in the choice of engineering or science as a major area of study and work by benevolent citizens. This does not imply, however, that STEM researchers uniformly adopt an indiscriminate techno-optimism. As a group, this small sample of technological innovators recognized nuance and an is-ought distinction in moral reasoning about the end results of advancements in human enhancement technologies. While debate between philosophical proponents and critics of human enhancement has become so charged and unproductive that reframing with neutral terminology (body modification) is being proposed (Rembold Citation2014), the potency, importance, and intrigue of the normative questions inherent to human enhancement technologies served to draw STEM practitioners into macroethical considerations with genuine interest. Their engagement and thoughtfulness are evidenced in their voluntary participation in the survey, and their considered personal responses. For many questions pertaining to human enhancement, the individual-to-individual variation covered the full breadth of possible responses. Although the small size of this study does not allow for statistical analyses related to sub-divisions of the sample, the exploratory results did not suggest a correlation of responses with gender, age, or nationality. Because norms and communications about the human body vary with these factors (Adams Citation2009; Blum Citation2002), some correlation – perhaps observable even in a small data set – would be consistent with sociologically based expectations. The preliminary results from the small pilot study reported in this article suggest the expansion of this research to include higher numbers of participants, varying constituencies, control groups, and longitudinal aspects – Are changes observed at the one-day time point maintained, reversed, or increased over time? Furthermore, do the thoughts provoked by FIXED encourage anticipatory consideration of ethical and societal dimensions of technological innovations, or action toward justice in their implementation?

Given the balanced content and open, exploratory style of FIXED, it is not surprising that its influence was changed thinking within individuals, with opposing directions of change represented within a group. Unlike many films in the documentary genre, this work of art evokes feeling without functioning primarily in advocacy for a particular viewpoint or stance. As one reviewer aptly put it, ‘Ultimately, Fixed is effective not because it answers the questions it poses well, but because it refuses to answer them at all’ (de Saille Citation2014). The high frequency of response deviation between pre- and post-viewing of FIXED, merely one day apart, on matters as fundamental as life outlook and the ways human beings are valued by society, is striking indeed.

Is it truly consistent with a positive or very positive outlook on life to consider oneself one accident away from the remainder of life with a negative or very negative outlook? Despite the limitations to interpretation inherent to small sample size, the proportion of participants who responded in this way () is notable, evidencing need for improvements with respect to the psychological and sociological aspects of disability in addition to technological advances. FIXED itself, and the research and educational initiatives drawing on it, including the work reported here, responds to this need – and the opportunity to include research innovators more meaningfully in thought and conversation about the ethical and societal dimensions of life-changing technologies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Center for Nano Science and Technology and the Center for Social Research at the University of Notre Dame.

Notes on contributor

Kathleen Eggleson is a biological scientist and practical ethicist at the University of Notre Dame, Center for Nano Science and Technology (NDnano), serving as the lead instructor of Technology and Ethics for entrepreneurial MS students in the Engineering, Science, & Technology Entrepreneurship Master's Program (ESTEEM) program, and as past Associate Director of the Reilly Center for Science, Technology, and Values.

Seth Berry is the Survey Methodology Consultant for the Center for Social Research at the University of Notre Dame. Through his work, he gets to collaborate on surveys with researchers from many different departments on campus. In his own research, he focuses on design issues within web-based surveys.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, J. 2009. “Bodies of Change: A Comparative Analysis of Media Representations of Body Modification Practices.” Sociological Perspectives 52 (1): 103–129. doi: 10.1525/sop.2009.52.1.103

- Agar, N. 2013. Truly Human Enhancement: A Philosophical Defense of Limits. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Blum, L. 2002. “Body Wars, the Clash of the Paradigms.” Qualitative Sociology 25 (2): 305–314. doi: 10.1023/A:1015427003600

- Bostrom, N. 2005. “In Defense of Posthuman Dignity.” Bioethics 19 (3): 202–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2005.00437.x

- De Saille, S. 2014. “Fixed: the Science/Fiction of Human Enhancement.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 142–145. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.882096.

- Fisher, E., S. Biggs, S. Lindsay, and J. Zhao.2010. “Research Thrives on Integration of Natural and Social Sciences.” Nature 463: 1018. doi:10.1038/4631018a.

- Fukuyama, F. 2002. Our Posthuman Future: Consequences of the Biotechnology Revolution. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

- Gerhart, K. A., J. Koziol-McLain, S. R. Lowenstein, and G. G. Whiteneck. 1994. “Quality of Life Following Spinal Cord Injury: Knowledge and Attitudes of Emergency Care Providers.” Annals of Emergency Medicine 23 (4): 807–812. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70318-3

- Harris, C. E., M. Davis, M. S. Pritchard, and M. J. Rabins. 1996. “Engineering Ethics: What? Why? How? And When?” Journal of Engineering Education 85 (2): 93–96. doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.1996.tb00216.x

- Herkert, J. R. 2005. “Ways of Thinking about and Teaching Ethical Problem Solving: Microethics and Macroethics in Engineering.” Science and Engineering Ethics 11: 373–385. doi: 10.1007/s11948-005-0006-3

- Hershberger, S. L. 2005. “Factor Scores.” In Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science, edited by B. S. Everitt and D. C. Howell, 636–644. New York: John Wiley.

- Hughes, J. 2012. “The Politics of Transhumanism and the Techno-millennial Imagination, 1626–2030.” Zygon 47 (4): 757–776. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9744.2012.01289.x

- Jotterand, F. 2008. “Beyond Therapy and Enhancement: The Alteration of Human Nature.” NanoEthics 2: 15–23. doi:10.1007/s11569-008-0025-z.

- Kass, L. 2002. Life, Liberty, and Defense of Dignity: The Challenge for Bioethics. San Francisco, CA: Encounter Books.

- Kohlberg, L. 1984. The Psychology of Moral Development. San Fransisco, CA: Harper & Row.

- Kotler, S. 2002. “Vision Quest.” Wired 10 (9): 94–101.

- Kurzweil, R. 2006. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York: Viking.

- Longman, P. 2010. “Think Again Global Aging: A Gray Tsunami is Sweeping the Planet – and Not Just in the Places You Expect. How did the World Get So Old, So Fast?” Foreign Policy 182: 52–58.

- Lustig, A. 2008. “Enhancement Technologies and the Person: Christian Perspectives.” The Journal of Law, Medicine, and Ethics 36 (1): 41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00235.x

- May, D. R., and M. T. Luth. 2013. “The Effectiveness of Ethics Education: A Quasi-Experimental Field Study.” Science and Engineering Ethics 19: 545–568. doi: 10.1007/s11948-011-9349-0.

- Myyry, L., and K. Helkama. 2007. “Socio-cognitive Conflict, Emotions and Complexity of thought in Real-life Morality.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 48 (3): 247–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00579.x

- Newberry, B. 2004. “The Dilemma of Ethics in Engineering Education.” Science and Engineering Ethics 10: 343–351. doi: 10.1007/s11948-004-0030-8

- R Core Team. 2014. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

- Reich, R. 2010. “Principles before Heroes.” Democracy 16: 29–33.

- Rembold, S. 2014. “‘Human Enhancement’? It's all About ‘Body Modification’! Why We Should Replace the Term ‘Human Enhancement’ with ‘Body Modification’.” NanoEthics 8: 307–315. doi:10.1007/s11569-014-0205-y.

- Resnik, D. 2000. “The Moral Significance of the Therapy-Enhancement Distinction in Human Genetics.” Cambridge Quarterly Journal of Healthcare Ethics 9: 365–377.

- Rest, J. 1986. Moral Development: Advances in Research and Theory. New York: Praeger.

- Revelle, W. 2014. psych: Procedures for Psychological, Psychometric, and Personality Research. Version 1.4.8.11 (August 12).

- Shakespeare, T. 2014. “Foreword: Five Thoughts about Enhancement.” In The Human Enhancement Debate and Disability, edited by Miriam Eilers, Katrin Grüber, and Christoph Rehmann-Sutter, ix–xiii. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weaver, C., J. Smith, and L. Fleisher. 2013. “Boston Marathon Amputees Face New Reality.” Wall Street Journal, April 18.

- Wickham, H. 2009. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. New York: Springer.

- Wolbring, G. 2003. “Science and Technology and the Triple D (Disease, Disability, and Defect).” In Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance: Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Information Technology, and Cognitive Science, edited by Mihail C. Roco and William S. Bainbridge, 232–243. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.