ABSTRACT

The upcoming concept of responsible innovation seems to gain foothold in Europe and beyond, but it still remains unknown how it can be implemented in the business context. This article explores how social entrepreneurs integrate values into their de facto responsible innovations, and provides empirically informed strategies to develop, implement and scale these innovations. It is based on an empirical investigation of 42 case studies of best-practice social entrepreneurs. This empirical study shows that social entrepreneurs focus on creating direct socio-ethical value for their target beneficiaries. They coordinate collective stakeholder action to develop, implement and scale their systems-changing solutions. And their bottom-up innovations are evaluated and scaled for impact. Ultimately, institutional support is sought to create top-down systems change. This article suggests a synthesised model of integrated strategies for responsible innovation that also covers implementation and scaling of innovation.

Introduction

Responsible innovation is a new and emerging concept that aims to take social and ethical aspects explicitly into account during innovation while balancing economic, social, cultural and environmental aspects. It is a new approach to innovation to develop better novel practices, deliver more societal benefits, better grasp the impacts of technologies, and realise public acceptance (Ribeiro, Smith, and Millar Citation2017). It is about taking ‘care of the future through collective stewardship of science and innovation in the present’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1570). This is expected to result in more responsible solutions for the grand challenges of our time (Von Schomberg Citation2011; Wickson and Carew Citation2014).

As such, responsible innovation has a positive connotation (Bos et al. Citation2014) and the idea gets a foothold in Europe and beyond. The concept focuses predominantly on how to govern science and technological development in a responsible way, thereby focusing primarily on the development phase of science and innovation. However, if responsible innovation wants to realise a paradigm shift in society, it needs to be adopted by the business community as well, since companies not only develop innovations but also bring them to the market. That it is crucial to get companies on board becomes clear in an EU funded project COMPASS, which specifically aims to provide a business case (i.e. incentives) for high-tech firms to adopt responsible innovation processes. Unfortunately, there are several reasons related to the drivers for responsible innovation, the process itself and the subsequent outcome that make it questionable to implement it in a business context (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015).

First, grand challenges like climate change are often called ‘wicked’ because they are complex, ill-structured public problems that are hard to pin down or to solve (Batie Citation2008). It is then highly questionable how to become responsive to stakeholders when such grand societal challenges act as inputs for innovation. Second, responsible innovation presupposes a transparent and interactive innovation process. However, transparency and interaction can challenge the information asymmetries on which business opportunities and innovation are based. Hence, such processes can jeopardise the competitive advantage of the firm, and thus its reason of existence. Third, the presupposed mutual responsiveness between stakeholders and shared responsibility for both the innovation process and its marketable products is conflicting with the notion that the investor alone is responsible for the risk-reward assessment and the subsequent investment decision (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015). Lastly, responsible innovation has a narrow focus on innovation outputs as it is being understood as science and technological development. This excludes other innovation outcomes even though they can have major societal implications as well (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015; Lubberink et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, responsible innovation neglects the crucial stage of implementing the innovation and scaling for impact. This is unfortunate since responsible innovation is not only about innovating with society, but also for society (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012). The business context however focuses on scaling innovations to maximise (social) impact. But this likely creates new managerial challenges, which may challenge the ethical principles that are behind the innovation in the first place (André and Pache Citation2016).

One of the assumptions in this article is that the emerging field of responsible research and innovation can be advanced if it learns from de facto responsible innovation practices that are already taking place in a business context. De facto responsible innovation is in this research understood as innovation practices and processes that are in line with the current understandings of responsible innovation, but they are not initiated with clear frameworks or guidelines for responsible innovation in mind. Learning from de facto practices appears to be commonplace in the emerging field of responsible innovation, others learned for example from risk assessment practices (e.g. Chatfield et al. Citation2017), Corporate Social Responsibility (e.g. Pavie, Scholten, and Carthy Citation2014) or social- and sustainable innovation (e.g. Lubberink et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, Ruggiu (Citation2015) champions alternative entrepreneurial forms that may have a disposition to engage in responsible innovation. The second assumption in this article is therefore that social entrepreneurs form a business community where de facto responsible innovations are developed, implemented and scaled for impact. There are three main reasons that support this assumption.

First, social entrepreneurs are capable of finding innovative solutions for complex societal challenges while adopting a business logic that focuses on efficiency (Bacq and Janssen Citation2011; Phillips et al. Citation2015). Second, social entrepreneurs have the aspiration to innovate for the benefit of society as opposed to pursuing profit or shareholder value like profit-oriented entrepreneurs (Shaw and Carter Citation2007; Santos Citation2012). Furthermore, their core values and beliefs are directly related to their actions (Waddock and Steckler Citation2016). Third, social entrepreneurs often develop social innovations (Phillips et al. Citation2015) that are not only social in their process but also in their outcomes (Ayob, Teasdale, and Fagan Citation2016). It is therefore similar to responsible innovation, which is about science and innovation for society that takes place with society (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012). Studying de facto responsible innovation in a social entrepreneurship context can therefore expand the narrow understanding of innovation being understood as science and technological development.

This article therefore aims to obtain a better understanding of de facto responsible innovations in the business context of social enterprises. It is based on an exploratory empirical investigation of 42 best practice social entrepreneurs. This research aims to contribute to the literature in the following ways. First, it explores how substantive values for responsible innovation are embedded in the innovation outcomes and their implications for society. The normative substantive approach is more suitable for the purpose of this study as it focuses more on the ‘product dimension’ and the value that can be created by including societal values. This approach is for example present in von Schomberg’s definition of responsible innovation (Ruggiu Citation2015), which is the definition that is most often referred to in its field (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). Second, this article provides empirically informed strategies that social entrepreneurs follow to implement and scale de facto responsible innovations to create more social value. It is important not only to focus on the process of developing the innovation but to focus on its outcomes as well, because the final innovation outcomes create social value by solving societal problems or pressing social needs (Phillips et al. Citation2015). Third, ensuing from the findings in this article, the case will be made that the business logic in companies might not only conflict with the current concept of responsible innovation but they may be an opportunity to strengthening the concept instead.

The following section presents the theoretical framework in which the normative substantive approach to responsible innovation is discussed. The second part of the theoretical framework discusses the concept of social entrepreneurship, and the norms, values and beliefs that guide their innovation activities. The materials and methods section explicates what data are analysed in this research, and how they are analysed. The results show how the most encountered normative values are integrated into innovative solutions by social entrepreneurs, and how they are implemented and scaled for impact. The discussion and conclusion of this article finishes with the conclusions that can be drawn from the results, and a discussion where we make a case that the conditions in the business context are not only a barrier for responsible innovation, it may also function as an opportunity for the concept of responsible innovation at the same time.

Theoretical framework

The central idea behind the concept of responsible innovation is to steer innovations into desirable directions and to make sure that they have the right impacts for society. However, who is in the position to decide what a desirable direction is, or what the right impacts of innovation should be? People have different and sometimes competing values, and hold different views about desirable directions and the right impacts of innovation (Von Schomberg Citation2013). There are two main approaches in the field of responsible innovation that inform how these desirable directions and right impacts can be determined, and thus whether an innovation can be deemed responsible (Ruggiu Citation2015): the normative approach and the procedural approach.Footnote1

The normative approach is based on (predetermined) substantive values that should be embedded in innovation outcomes and their implications in order to be considered responsible. Hence, it focuses on the outputs of the innovation process, rather than the process itself (Von Schomberg Citation2013). The procedural approach (Ruggiu Citation2015) focuses primarily on the process of innovation; it is based on procedural reasoning where the process of responsible innovation should adhere to certain conditions or dimensions (Pellé Citation2016). It focuses on deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement, who are included at an early stage to establish the values that the innovation outcomes and their implications should respond to (Ruggiu Citation2015). In other words, it does not proclaim a predetermined normative view on the innovation outcome nor its implications but predominantly focuses on the ‘process dimension’ of responsible innovation.

However, these different approaches are not mutually exclusive and combinations can be found within conceptualisations of responsible innovation (Pellé Citation2016). The definition of responsible innovation by Von Schomberg (Citation2013) is illustrative for this, as he argues that the process dimension should be based on transparency and mutual responsiveness among stakeholders, while the product dimension should have the right impacts that follow from predetermined normative substantive values. This article focuses on the product dimension of responsible innovations, and therefore builds upon the normative substantive approach where the right impacts of innovations are articulated.

Norms, values and beliefs in responsible innovation

The normative (substantive) approaches focus predominantly on the innovation outcome and their implications (e.g. in van den Hoven et al. Citation2013 or Von Schomberg Citation2013) which rely on sets of outcome-oriented norms and values (Ruggiu Citation2015; Pellé Citation2016). Those norms and values can act as more practical ‘anchors’ to steer the innovation in a predetermined desirable direction or to assess whether innovation outcomes and their implications can be deemed responsible (Pellé Citation2016). Von Schomberg (Citation2013) argues that there are public values that are already determined and democratically agreed upon. These public values are communicated in the EU Treaty, and they are embedded in the principles, rights and freedoms that are stipulated in the European Union Charter of Fundamental Rights (henceforth EUCFR). These rights, principles and freedoms can be seen as the parameters of the right impacts of innovations.

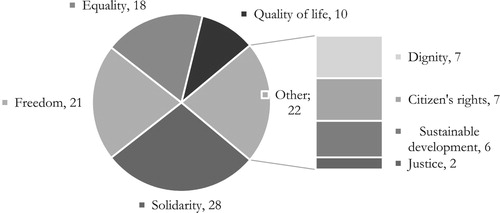

Based on the treaty and the EUCFR, Von Schomberg argues that innovations should be steered towards (ethical) acceptability, societal desirability and sustainability, which should act as the three normative anchor points for responsible innovation (Citation2013). Following from the EU treaty, one could say that innovations and their implications should be ‘founded on the values of respect for human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of persons belonging to minorities’ (European Union Citation2007, 11). Furthermore, innovations should be designed with a view to a desirable society, hence ‘a society in which pluralism, non-discrimination, tolerance, justice, solidarity and equality between women and men prevail’ (European Union Citation2007, 11). Inferring from the EUCFR, one could conclude that innovations and their impacts on society should not conflict, and preferably benefit social justice, gender equality, solidarity and human rights, quality of life, protection of human health and the environment, sustainable development and a competitive social market economy. shows a graphical overview of these normative anchor points, the public values and the subsequent rights, principles and freedoms.

Figure 1. An overview of the right impacts of responsible innovation outcomes and their implications.

Ruggiu (Citation2015) connects the focus on normative targets for the product dimension with what can be considered the problem or purpose dimension of responsible innovation. He argues that the grand challenges that are stipulated in the Lund Declaration (e.g. global warming, aging populations or energy supply) refer to societal needs and ambitions, which can therefore also be seen as normative ends for responsible innovation. He further argues that ‘the development of entrepreneurial forms that address these needs thus represent an alternative way of increasing productivity and expanding markets through responsible innovation’ (Ruggiu Citation2015, 226).

However, the normative approach is not without its caveats. For example, it does not give any guidance when it comes to colliding substantive norms and values; an innovation for enhanced security can for example conflict with privacy. However, this article aims to explore how substantive norms and values are integrated into innovation outcomes, and provides practical implications. The normative approach is more suitable due to its focus on the product dimension of innovation.

Norms, values and beliefs in social entrepreneurship

Definitions of social entrepreneurship should logically draw upon entrepreneurial processes that require opportunity exploitation and resource (re)combination processes (Newth and Woods Citation2014). The following working definition is therefore adopted in this article:

Social entrepreneurship is exercised where some person or group: (1) aim(s) at creating social value, either exclusively or at least in some prominent way; (2) show(s) a capacity to recognize and take advantage of opportunities to create that value (“envision”); (3) employ(s) innovation, ranging from outright invention to adapting someone else's novelty, in creating and/or distributing social value; (4) is/are willing to accept an above-average degree of risk in creating and disseminating social value; and (5) is/are unusually resourceful in being relatively undaunted by scarce assets in pursuing their social venture. (Peredo and McLean Citation2006, 64)

Social entrepreneurs are emphatic and driven by prosocial motivations and responsibility motives (Mair and Noboa Citation2006; Stephan and Drencheva Citation2017). Their values and beliefs play an important role for their enterprise, which is for example reflected in their dedication to create sustainable social impact over (personal) profit. These social logics can compete with market logics and raise ethical challenges (Zahra et al. Citation2009). However, social entrepreneurs are capable of staying loyal to their own values and beliefs even though they operate in an entrepreneurial setting that is full of dominating market forces (Dey and Steyaert Citation2016). This is important because their values and beliefs are deeply rooted in the mission of their enterprise (Zahra et al. Citation2009) and play an important role in their entrepreneurial decision-making (Koe Hwee Nga and Shamuganathan Citation2010). Visionary social entrepreneurs envision a desirable future state in which a certain societal problem or pressing social need is resolved. These visions are influenced by their own norms, values and beliefs. Not only do they have as such a normative vision, but they also have the capacity to visualise and advance a sustainable solution to reach that desirable future state (Waddock and Steckler Citation2016). However, ‘wayfinding’ social entrepreneurs act without having a clear vision yet; they act for example out of moral obligation. The sense making of their actions and subsequent translation into vision follows later. Yet, both have an internal drive to do something good for society (Waddock and Steckler Citation2016) and act upon their norms, values and beliefs.

Not only in responsible innovation but also in social entrepreneurship literature the issue is raised that there is no consensus about the common good. There can be contestation as to what is social about the innovation outcomes of social entrepreneurs (Cho Citation2006). Exactly this ‘social’ sub-concept is ill-defined in social entrepreneurship literature, and defining it is problematic because establishing the social ends is a political process that is full of values (Cho Citation2006; Choi and Majumdar Citation2014). Many social entrepreneurs organise the development of their solutions around values that they consider to be social. This implies that they make claims about their ability and position in society to articulate what is in the interest of the public. This is especially troublesome in cases where this ‘social’ is contested (Cho Citation2006) such as the public sector in which social entrepreneurs often operate (Santos Citation2012), not to mention cases where the values of radical social entrepreneurs differ from the prevailing societal morals and norms (Zahra et al. Citation2009). For example, Girls Not Brides is an organisation committed to ending child marriages in countries where this is still a tradition. However, Cho (Citation2006) argues that innovations in cases of contestation can only be considered social when they are the result of a public political process; otherwise, it is merely the entrepreneur’s conception of ‘the good’ that he or she aims to pursue. The call for a procedural approach in the governance of innovation is therefore not only confined to the field of responsible innovation.

This research can therefore act as a double-edged sword because it delineates what is social about the innovations of social entrepreneurs based on the normative substantive approach in responsible innovation. At the same time, it advances the field of responsible innovation by exploring how the rights, principles and freedoms are integrated into innovations, and it provides strategies for successful implementation and diffusion of responsible innovations in society.

Materials and methods

The research subjects of this study are 42 social entrepreneurs who are elected as Ashoka fellows.

Ashoka Fellows are visionaries who develop innovative solutions that fundamentally change how society operates. They find what is not working and address the problem by changing the system, spreading the solution, and persuading entire societies to take new leaps. […] social entrepreneurs persist however long the transformation takes. They are creative yet pragmatic, constantly adjusting and changing, with a committed vision that endures until they have succeeded. (Ashoka Citation2011, 11)

As part of a larger research project, we approached Ashoka social entrepreneurs to complete a self-assessment questionnaire regarding their innovation process and conducted content analyses of their profile descriptions which cover their innovation outcomes and implications. Based on the questionnaire-based data, we were able to differentiate between typologies of social entrepreneurs with regard to their innovation process (Lubberink et al. Citation2018). For more insights into the process of social innovation, and key characteristics of the social enterprises, we kindly refer you to the article (Lubberink et al. Citation2018). However, in this article, we concentrate on the outcomes of the innovation process (i.e. the product dimension), and the results are therefore based on content analyses of their profile descriptions. We contacted social entrepreneurs (n ≈ 270)Footnote2 who operate in Europe, the United States or Canada, and who are elected between 2009 and February 2016. We invited them to participate in this project by contacting them via e-mail, sending e-mail reminders, and having follow-up phone calls. In the end, there were 42 social entrepreneurs who completed the self-assessment questionnaire, and therefore the number of profile descriptions that were subject to content analyses totals 42 as well. The sample is confined to these countries because applying the concept of responsible innovation as an a priori framework becomes problematic beyond the global north (Macnaghten et al. Citation2014; Wong Citation2016).

The average length of a profile description is 2177 wordsFootnote3 (SD = 515), and they were analysed with Atlas.ti software package that involved both inductive and deductive coding methods. The EU Treaty and EUCFR were used as an initial coding scheme for deductive coding of quotations that indicated whether a certain right, principle or freedom was integrated into an innovative solution, such as the rights of the elderly or non-discrimination (the coding scheme is presented in in Appendix). During the analyses, we observed that social entrepreneurs do not develop a single innovation, instead they provide systems-shaping solutions that consist of several underlying and interrelated innovations (e.g. new financial products, skills-building activities, or medical treatments). These underlying innovations were deductively coded using the coding scheme of social entrepreneurship actions that is developed and tested in Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012, 370). Inductive coding took place to map different aspects that shape these innovations or that are shaped by these innovations (e.g. quotes related to scaling of the innovation, piloting/testing the innovation, or accessibility of the innovation). Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012, 371) also provide a coding scheme for deductive coding of the principles for justification of the innovation (e.g. enhances efficiency, productivity, creativity, market mechanisms or enhances problem awareness). These coding schemes can be found in their original forms in Appendix (Tables A2 and A3).

As opposed to Chandra and Shang (Citation2017), we did not use stratified sampling method of Ashoka profiles. Nevertheless, each of the six fields of work that Ashoka uses to classify their fellows is represented in our sample. The entrepreneurs in our sample focused predominantly on civic engagement (n = 11), economic development (n = 9), learning/education (n = 8), health (n = 8), human rights (n = 3) and environmental issues (n = 3). Also, Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012) conducted a random sampling of Ashoka profiles and included all entrepreneurs of the Schwab Foundation. Their sample ended up with a bias towards civic engagement and economic development. Compared to Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012), our sample has relatively a high share of entrepreneurs working in the fields of learning/education and health, whereas the fields of human rights and environmental issues are relatively underrepresented. The study by Meyskens et al. (Citation2010) is also based on Ashoka profile descriptions, yet they focused on the two most represented fields of work, which were economic development and learning/education. To conclude, the social entrepreneurs in our sample are heterogeneous with regard to the sectors in which they operate and the solutions provided.

Visual representation of the relationships between the codes was created for each individual case to better understand the relationships between the solutions provided, their implications, and how they relate to the right impacts for innovation. After a number of discussions with the researchers, the decision was made to first provide descriptive data of the rights, principles and freedoms behind the values addressed. This subsequently leaves room for a more detailed explanation of how the most encountered normative substantive values are integrated into the innovation outcomes, and to describe the strategies followed to develop de facto responsible innovations. This is done for the most encountered values (and the rights, principles and freedoms that substantiate these values) and the findings are accompanied by exemplary quotes.

Results

Most of the social enterprises (35 out of 42) in our sample integrate more than one right, principle or freedom into their innovation. Furthermore, these rights, principles or freedoms can span multiple categories of the EU Treaty and its Charter of Fundamental Rights. In the presentation of the results, HOFR serves as an exemplary case to show how this can be understood in practice.

[HOFR] pioneers a diagnostically superior, personal, low-cost breast examination method by training blind people as skilled diagnosticians. [Its] approach integrates them into the primary health care infrastructure, while enhancing women’s health care experience and opening an entirely new professional path to a differently-abled constituency.

HOFR is among many other social enterprises that integrate a variety of rights, principles and freedoms, which are part of multiple overarching categories (30 out of 42 cases). The categories that are most often addressed in the solutions of the social enterprises are solidarity (n = 28), freedom (n = 21) and equality (n = 18). Each of these categories is presented respectively, and tables are provided that show how their underlying rights, principles and freedoms are integrated into innovations. shows how often a category is addressed by solutions of the social enterprises.

Solidarity

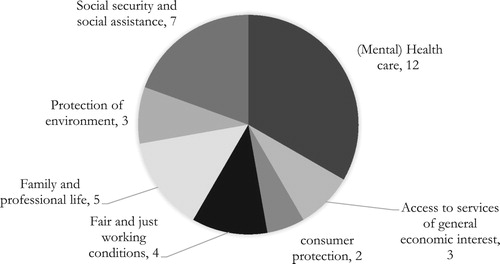

The right that is most often integrated into the solutions of social enterprises is the right to have access to preventive health care, medical treatment and human health protection (n = 12). Each of these social enterprises identified a different opportunity to realise its vision to strengthen the right to health care. For example, KEJO aims to improve emergency care for populations in rural areas, HOFR champions affordable breast examinations and BLBR fosters repurposing of drugs for debilitating and rare diseases. Another frequently encountered right is the right to social security and social assistance (n = 7) that is integrated into solutions that for example combat poverty, or provide services to elderly or homeless people who are dependent on others. With regard to family and professional life (n = 5), innovative solutions are provided that enhance work-family balance, that provide farming opportunities for families, or that provide income opportunities for underprivileged families. An overview of all rights, principles and freedoms that are part of the category Solidarity can be found in .

Figure 3. The occurrence of rights, principles and freedoms that are part of ‘Solidarity’, and are integrated in the solutions by the social enterprises.

None of the social enterprises work in isolation on their solution. They either work with the target beneficiaries or with other stakeholders in the innovation system. Social enterprises are true networking enterprises as their solutions depend upon a large network of stakeholders who often carry responsibility for a part of the solution. For example, KEJO is a social enterprise that connects general practitioners, specialists, firemen, and local councils to create communities who together provide emergency care in rural areas. The company is acting as a coordinator and provides them with ‘infrastructure development, intensive bespoke training, and communication strategies to ensure that volunteers are organized and enabled to respond to medical emergency calls quickly and succinctly’. While the company is responsible for its own revenues, each emergency community is responsible for raising theirs (but the social enterprise helps in coordinating this fundraising) and a university is responsible for scaling the training of personnel. KEJO is therefore an exemplary case of a social enterprise that does not provide the care itself. Instead, they create a stakeholder network around the solution and coordinate its collective action. This is a common strategy among many social enterprises in our sample.

Social enterprises do not only create communities of previously disconnected stakeholders, but they also employ more standardised approaches to empower communities for impact. For example, RINO first develops trust-relationships with the impoverished communities and aims to develop a movement that is capable of solving their own problems. The services that are provided by RINO (and LEIS too) focus on creating a movement, providing them with the tools to create the necessary change themselves, and to take care of themselves. More detailed descriptions of how KEJO, RINO and LEIS integrate values into their solutions can be found in .

Table 1. Overview of descriptions how the most common rights, principles or freedoms of Solidarity are integrated into innovations.

Freedom

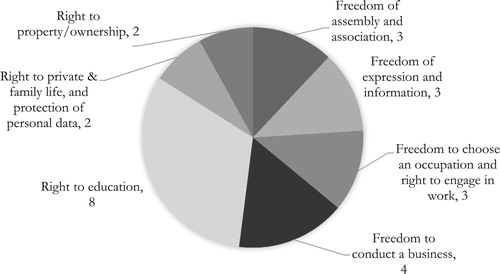

The right to education is most often integrated into the solutions developed by social enterprises (n = 8). This involves solutions that enhance access to (proper) education, solutions that improve the education system, or focus on specific competencies that education should develop. The freedom to conduct a business (n = 4) is most often integrated into solutions that provide the resources (human, social, and economic capital) to start a business. An overview of all rights, principles and freedoms that are part of Freedom can be found in .

Figure 4. The occurrence of rights, principles and freedoms that are part of ‘Freedom’, and are integrated in the solutions by the social enterprises.

Some of the social enterprises address challenges related to learning and education (n = 8), others changed entire education systems (n = 2). For example, SLZD is ‘empowering both schools and citizens to transform their education system from within. To do this, [it] repositions schools as centers of community life and incentivizes parents, experts, businesses and communities to become stakeholders in education’. Others integrated missing elements into already existing education curricula (n = 3) or focused on empowering the teachers in the education system (n = 2). Social enterprises in all cases develop a network of involved practitioners and provide training to teachers so they are able to provide quality education. The principles behind their solutions involve logics of collaboration, either between the different stakeholders involved in education or as in participatory learning for students. Furthermore, the solutions in our sample aim to enhance for example creativity, non-conformity and imagination, which can be achieved by engaging in arts, games and other ways to enhance and exploit their creativity. Their education programmes require the commitment of the schools and other stakeholders involved, while the social enterprise acts as a coordinator of the activities.

There are different ways in which the social enterprises integrate the freedom to conduct a business into a solution. One way is to act as an incubator, and hence provide expertise, finances and a supporting peer-network to help nascent entrepreneurs to start their enterprise. Another way is to focus on institutional change and create legislation for work integration social enterprises (see the case description of DUCH in ). And VOAT aims to improve the position of insolvent entrepreneurs and to strengthen their rights to start an enterprise again (see the case description of VOAT in ). Not only VOAT, but also other social enterprises are making use of peer support groups that include their target beneficiaries, who can subsequently help each other out. For example, DRJE is a social enterprise that aims to realise freedom of expression and information and stimulates peer support of journalists in countries where independent journalism is under threat (see ).

Table 2. Overview of descriptions how the most common rights, principles or freedoms of the category freedom are integrated into innovations.

Equality

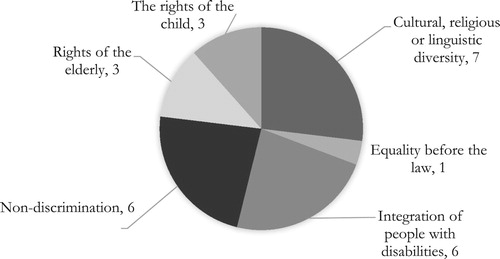

The principle to recognise cultural, religious, or linguistic diversity is often integrated into innovative solutions (n = 7). For example, FIKR offers mental health care in multiple languages to prevent the exclusion of people who or not proficient in the official language. Another interesting example of linguistic diversity comes from NEMI, which developed a code language for colour blind people. This enterprise has a normative view that this code language becomes as ‘mainstream’ language like braille (see ). The right to non-discrimination (n = 6) is integrated into solutions that aim to change the public’s opinion of marginalised, stigmatised or underprivileged communities (e.g. disabled, minorities, or rural population). This is often accompanied by an aim to empower these communities at the same time (n = 5), to subsequently foster their inclusion into society. The right to integration of people with disabilities (n = 6) is apparent in solutions where disabled people are integrated into work. JAAR, for example, aims to develop a business case for work integration social enterprises, whereas DUCH aims to create an enabling institutional environment for such enterprises. An overview of all rights, principles and freedoms that are part of Equality can be found in .

Figure 5. The occurrence of rights, principles and freedoms that are part of ‘Equality’, and are integrated in the solutions by the social enterprises.

Table 3. Overview of descriptions how the most common rights, principles or freedoms of equality are integrated into innovations.

NEMI is an interesting case as it is one of the few social enterprises that developed a single innovation (i.e. a colour code) and serves as an exemplary case for scaling. Scaling is in this case at least as important as the innovation itself for realising the impact. The social enterprise focuses on scaling-out by implementing the colour language in education (since the colour is important in textbooks), the health sector (e.g. for drug and pharmaceutical labels) and transport sector (e.g. for orientation signals). Moreover, it focuses on scaling-up by designing a national law for implementation of the colour code. Another example comes from FIKR; this social enterprise integrates linguistic diversity into its mental health care solution as the company provides its care in nine different languages, because vulnerable communities may not speak the official language well.

Three social enterprises respond to human rights issues and their solutions respect the right to non-discrimination, integration of people with disabilities and cultural, religious and linguistic diversity. Different strategies are put in place to foster this, which revolve around creating a network of previously disconnected stakeholders, providing counselling services for these overlooked communities, and changing the opinion that the public holds of these communities. Furthermore, these organisations are inclined to engage in policy making and lobbying. Together, these efforts aim to strengthen the position of the marginalised in society.

Synthesis of strategies to develop, implement and scale socio-ethical innovations

Added socio-ethical value

The social enterprises develop solutions for grand challenges that create direct socio-ethical value for the target beneficiaries, which are predominantly vulnerable and marginalised communities in society. The socio-ethical value is created by integrating the rights, principles and freedoms of the EUCFR in the innovative solution, in ways that are previously presented. The solutions that create socio-ethical value are a response to a violated right, principle or freedom (e.g. alternative breast examinations in response to the deteriorating right to preventive health care) or they further enhance the created socio-ethical value (e.g. providing mental health care in nine languages).

The solutions that are developed and implemented are systems-shaping solutions that consist of an interconnected set of innovations that influence each other and interrelate with the larger systems-shaping solution. For example, the systems-shaping solution of HOFR consists among others of a manual breast examination by visually impaired women (process innovation) that is accompanied by braille strips for coordination (product innovation). Likewise, the KEJO provides emergency care in rural areas which require new medical devices (product innovations) and new approaches to delivering emergency care in rural areas (process innovation).

Another design characteristic that comes with socio-ethical value creation for the target beneficiary is to enhance availability, accessibility, and acceptability of the solution. For example, social enterprises find ways to integrate affordability and accessibility as a design factor for the solution. FIKR is an exemplary case as it wants to make mental health care available to all. It, for example, engages in price differentiation to stimulate availability to all. People who cannot afford it get mental health care for free or for reduced fees, while the full fee is still half of the market rate. It also focuses on accessibility as the staff does not only have face-to-face sessions but also offers online programmes. Furthermore, they make sure that the setting is welcoming and discreet, and that it does not appear to be ‘medical’, which stimulates acceptability of their clients. These design characteristics are all developed to break down the barriers to access mental health care.

Bottom-up innovation

The main strategy to create socio-ethical value is by working closely with the target beneficiaries who are stimulated to be involved in the search for a solution. In other words, their solutions are developed at a grassroots level and as bottom-up innovation processes. This fosters empowerment of communities who then play an important role in strengthening their own position in society. For example, in the case of FOHA, ‘Roma people are co-creating solutions to their mutual problems’, and she helps them in identifying problems, organise resources, and developing and following a roadmap for change.

However, the target beneficiaries are not the only stakeholders who are involved in the development or implementation of the solution. For example, teachers are involved to improve or embed education-related solutions, while local authorities collaborate with social enterprises in community initiatives, and universities are involved by social enterprises to provide missing knowledge or to assess the impact of the solution. Other (civil society) organisations are also involved to implement and provide the solution, since all social enterprises that initiated the solution are either micro- , small- or medium-sized enterprises with limited resources. These social enterprises therefore predominantly act as coordinators of collective action in response to a grand challenge.

Radical incrementalism

The solutions and their underlying innovations result from multiple rounds of iterations. Together with the target beneficiaries and other stakeholders, social enterprises pilot, experiment and improve their idea to end up with a solution that works in a specific setting. It appears to be vital for social enterprises to pilot and validate their solutions (n = 17), for example, because it provides more legitimacy to operate. Once they know that their proposed solution works, they look for strategies to scale the solution. This is, for example, the case for OGTE, which developed a successful ‘consult, prototype, verify and spread’ approach and uses its proven approach for new types of needs.

Learning and innovating to develop a working solution is a necessary but not sufficient condition for creating socio-ethical value. It needs to be complemented with implementation and marketing of the solution, which is where scaling comes into play. However, it is a balancing act to find out when to stop innovating and start scaling, as both require the allocation of sufficient resources. The innovation can be developed, improved and validated in small community settings, and subsequently, it can be scaled for impact. When the right strategies for scaling are applied, it can have a profound impact on communities in other settings too, or even for larger societies. The incremental innovations in small community settings can therefore result in radical change in society in this way.

One way to scale the solution is by sharing the idea and encouraging other organisations to replicate the solutions in other settings. This scaling across is a strategy used by HOFR as it ‘is spreading the Discovering Hands® method through a newly found non-profit organization to all other German occupational schools, which then will be licensed to instruct MTEs on the standardized training curricula’. NEMI is scaling up by applying the colour code in new areas (e.g. transportation, education, fashion industry) to reach new target beneficiaries, while at the same time it is scaling deep by continuously improving its colour code. The previous example of OGTE, which uses its innovative approach for newly identified needs, is an example of diversification as a scaling strategy. These strategies for scaling are not only important for the growth of the venture, but it is also maximising social impact and thereby also its socio-ethical value creation. In the end, social enterprises may influence policy making or actually be involved in policy making within their specific field, thereby maximising social impact by sharing their expertise.

Engaging institutional support

Not all solutions are only the result of bottom-up processes. There are also successful ways of top-down approaches, or social enterprises involved in top-down and bottom-up processes of developing and scaling the solution. This is evident from the fact that a large share of social enterprises are engaged in policy making and lobbying activities (n = 15). For example, DUCH was involved in policy making and legislation to achieve a legal form of social enterprises in its country, with a specific focus on work-integration social enterprises. Sometimes social enterprises are invited to participate in policy making as they gained legitimacy through their work and became expert organisations with regard to the social problem that they address. This is, for example, likely when the social enterprise responded to a problem that the government did not recognise or failed to (properly) address. Another strategy for systems change is to engage in public communication activities to inform the public or more specific audiences, about the urgency of the social problem or neglected social needs. This can create awareness by the targeted audience for the problem, which is an important first step for subsequently creating systems-change. Other ways to gain legitimacy is through strategic partnering with well-regarded organisations, operating in transparent ways, and having third-party validation of the solution.

Overall, social enterprises create socio-ethical values for their target beneficiaries that require the involvement of a wide variety of stakeholders, who engage in collective coordinated action. These predominantly bottom-up innovative approaches are piloted and tested to become structured and validated approaches to social change, which are subsequently scaled for impact. In the end, this bottom-up process can be combined with higher-level institutional support, either because the social enterprise is invited to participate in policy making or through lobbying and media activities of the social enterprise.

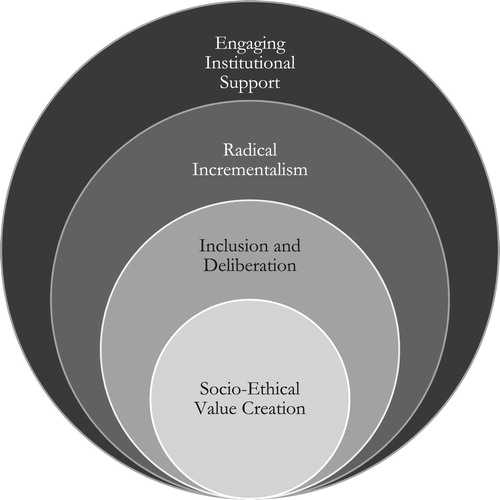

is a graphical representation of the interrelated strategies to develop responsible systems-shaping solutions. This starts at a small scale with an innovation that responds to a neglected social problem or unaddressed pressing needs, which can be directly linked to a right, principle or freedom that is violated or needs to be strengthened. Social enterprises integrate these rights, principles and freedoms in their solutions and thereby create direct socio-ethical value for their target beneficiaries. The development and implementation of their solution requires the involvement of a wide variety of stakeholders who engage in coordinated collective action. Subsequently, the final solution crystallises when pilots have taken place, and the impact of the solution is validated. This is followed by multiple strategies for scaling that are vital for enhancing socio-ethical value. In other words, they engage in radical incrementalism. Ultimately, social enterprises act as change agents in society by lobbying, creating public awareness, or taking part in policy making activities to develop supportive institutional change. These four interrelated layers of strategies can therefore be seen as an integrated approach of responsible innovation in a business setting, based on a synthesis of social enterprise cases in which different activities were performed and solutions provided.

Conclusions and discussion

This article aims to obtain a better understanding of de facto responsible innovation in the business community of social enterprises and explores how substantive values for responsible innovation are embedded in the product dimension of innovations. Additionally, empirically informed strategies are proposed to develop, implement and scale de facto responsible innovations in a business context. The conclusion can be drawn that social enterprises integrate multiple rights, principles and freedoms that cover multiple categories within the EUCFR. The findings indicate that social enterprises address a neglected social problem or pressing social needs that can be directly related to a violated right, principle or freedom, or that need to be strengthened. Additionally, they integrate other rights, principles and freedoms as well, and thereby creating even more socio-ethical value for their target beneficiaries.

This article proposes a new approach to responsible innovation in a business context based on a synthesis of empirically informed strategies. The business logic that is present in social enterprises stresses the importance of implementing and scaling innovation. First, because the founders of social enterprises often have a disposition to identify an opportunity for creating socio-ethical value directly for the target beneficiary, which is in line with the findings by Chandra and Shang (Citation2017). Socio-ethical value is created by providing solutions for social problems or pressing social needs while integrating important rights, principles and freedoms. Second, social enterprises often break down barriers to adopt the innovation, for example by price differentiation based on income or by providing the solution in multiple languages. The example of the solution provided by FIKR (see the section ‘Added socio-ethical value’) is exemplary for breaking down barriers to access the solution. Third, social enterprises coordinate collective action of a wide variety of stakeholders who are gathered around their vision. This stakeholder involvement is not only important for the development of the innovation, but also for its implementation and subsequent scaling. This, for example, becomes clear in the role that teachers play for social innovations in education or the Roma minorities who’s collective action is coordinated by FOHA (see the section ‘Bottom-up innovation’) The focus on implementing innovation that is present in business logics can therefore be an added value for the current notion of responsible innovation that focuses predominantly on stakeholder engagement and deliberation during the development of innovation (e.g. Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013)).

Subsequently, the small scale and bottom-up solutions of social enterprises are often validated before scaling takes place. This strategy can be related to the idea of radical incrementalism, where it is also described in more detail. Radical incrementalism is understood as a focused evaluation of new small-scale incremental solutions that can subsequently be strategically scaled for generating large societal impact. For example, Goldstein, Hazy, and Silberstang (Citation2010) also found that social entrepreneurs who first operate on a small scale develop solutions that have a profound impact on society in the future. The model is completed with the search for institutional support, which is achieved by lobbying for institutional change or when social enterprises become involved in policy making. Social enterprises can therefore play a role as signalling actors in society, since through their work they may alert members of society of the neglected social problem that they address, and the effective solutions that exist (Santos Citation2012). Responsible innovation is not only about innovating with society but also for society (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012). However, value for society is only created when innovation is implemented, and value creation is boosted with the scaling of innovation. The synthesis of strategies to develop, implement and scale responsible innovations in a business context can therefore serve as an opportunity to advance the current notion of responsible innovation.

It needs to be acknowledged that bringing innovation to the market and scaling for impact are positively portrayed in this article, and these are indeed crucial stages for creating socio-ethical value, besides the development of the innovation itself. However, scaling innovative solutions is not inherently good, just as innovations in general are not inherently good. Research by André and Pache (Citation2016) showed that scaling social innovation and realising growth of the enterprise can create tensions with the original aim of social enterprises, which is to provide care. However, such tensions within the firm may lead, for example, to mission drift, i.e. moving away from the core mission of the firm. Scaling may not only be a source of tensions for the firm but also for the innovation itself. For example, scaling across means that the innovation is disseminated among other actors who subsequently implement it in new contexts. This raises, for example, the questions: who is responsible for the consequences of the innovation. And how can one make sure that it will yield similar impacts? HOFR for example chose to license its innovative solution, by doing so it ensures that other actors cannot deviate from the approach and that the innovation is properly replicated. We therefore suggest to advance the concept of responsible innovation by not only focusing on socio-ethical considerations for the development of innovation, but also to prove its value by informing how implementing and scaling innovation can be done in a responsible manner. This will benefit socio-ethical value creation as it will scale for impact while at the same time it responds to social and ethical tensions that can come with scaling. We argue that this is a vital step for responsible innovation if it wants to live up to its ambition.

The previous sections included the results of this study, and the insights that were obtained from the analyses, which resulted in an empirically informed strategy for responsible innovation in a business context. This is based on profile descriptions of best practice social enterprises, which can be used as a window into human experience (Meyskens et al. Citation2010). They are best practice social enterprises because they went through a meticulous selection process. This brings us to the first limitation of this study, which is the representativeness of these well-established social enterprises and their profile descriptions. The selection process of Ashoka makes sure that only well-established social enterprises that developed and implemented systems-changing solutions become Ashoka fellows. Yet, Zahra et al. (Citation2009) argue that there are also social enterprises remain to work on atomic problems and develop small-scale solutions without subsequently looking for opportunities to scale for impact. The systems-changing solutions and subsequent scaling for impact that emerged from the empirical cases are therefore not representative for all manifestations of social entrepreneurship. This means that the process of radical incrementalism and engaging in institutional support are expected to be less prevalent in the works by social enterprises looking at atomistic problems and solutions. Also, the social enterprises in this sample predominantly operate in the third sector, which is representative for social entrepreneurship (Kerlin Citation2006; Santos Citation2012). However, social enterprises that are operating in sectors with competition of profit-oriented enterprises may have less space to focus on socio-ethical value creation and may be forced to focus on economic value capturing. Future research could therefore investigate how social enterprises in such competitive environments develop their systems-shaping solutions and scale for impact.

The second limitation comes from the fact that Ashoka is a supportive organisation for social entrepreneurship, and therefore it cannot be ruled out that the profile descriptions contain a more positive portrayal of social entrepreneurship than it actually is in practice. For example, information with regard to trade-offs that had to be made, conflicting values or other problems are only scarcely mentioned. However, the added value of the profile descriptions outweighs its limitations since the aim of this article is to identify successful strategies to integrate the values into innovative solutions. Combined with the fact that the case study descriptions are comparable as they have identical structures, it allows us to provide a valid stylisation of strategies to integrate values into solutions. Which is also why Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012) used Ashoka profile descriptions in their research as well, to describe how social entrepreneurs create change for the benefit of society.

The third limitation of this study is the fact that social enterprises do not focus on science practices nor on technological development. Therefore, we cannot assure that the findings of this article can be translated directly into trajectories of science and technological development that are often the phenomenon under study in the field of responsible innovation. However, technological solutions are not the panacea of grand challenges (Godin Citation2015) and other solutions have to be taken into account as well. The profile descriptions show that social innovations can be an interesting avenue to look for solutions that respond to grand challenges. Furthermore, non-technological innovation can have a profound impact on society as well, both of desirable and detrimental nature. Therefore, responsible innovation should not only be confined to science and technological development, and should broaden its narrow scope of innovation by including other forms of innovation as well, like social innovation. This article can thus be considered as one of the first efforts to include other forms of innovation as well, and provides a new approach to develop, implement, and scale responsible innovation based on empirical investigations of business practices.

Acknowledgements

The EIT is a European Union body whose mission is to create sustainable growth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Rob Lubberink is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Business Management and Organisation group of the Wageningen University. Rob started his PhD after graduating in Management, Economics and Consumer studies at the Wageningen University in 2013. His PhD research focused on Responsible Innovation in the context of Social Entrepreneurship. His current research focuses on entrepreneurship and innovation by marginalised smallholders in developing- and emerging economies.

Vincent Blok is associate professor in Business Ethics and Responsible Innovation at the Business Management and Organisation Group, and associate professor in Philosophy of Management, Technology & Innovation at the Philosophy Group, Wageningen University, Netherlands. Blok’s research group is involved in several (European) research projects at the crossroads of business, philosophy and innovation. Blok’s work has appeared in Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Cleaner Production, Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics and Journal of Responsible Innovation and other journals. See www.vincentblok.nl for more information about his current research.

Johan van Ophem is associate professor at the Urban Economics group of the Wageningen University. His teaching and research relate to the field of consumer behaviour, lifestyles, health economics and household economics. He has published in these fields and he has edited several publications in the field of economics and sociology of the household. He is (co)-organiser of various scientific conferences and an active member of European university networks.

Onno Omta graduated in biology in 1978 and after a management career he defended his PhD thesis on the management of innovation in the pharmaceutical industry in 1995 (both at the University of Groningen). In 2000 he was appointed as chaired professor in Business Administration at Wageningen University. He is (co-)author of many scientific articles on innovation management. His current research interest encompasses entrepreneurship and innovation in chains and networks in the life sciences.

ORCID

Rob Lubberink http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8940-5471

Vincent Blok http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9086-4544

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 As a matter of fact, Ruggiu (Citation2015) uses the term ‘socio-empirical’ approach, which is actually similar to the procedural approach that, for example, Pellé (Citation2016) and Oudheusden (Citation2014) talk about. For consistent use throughout the chapter there is chosen to use the term ‘procedural’ approach as it is more common in the discourse on responsible innovation.

2 These are the number of email recipients to whom the questionnaire was sent. However, some social enterprises were founded by two or more entrepreneurs. In other cases, other emails were suggested by the secretaries to get in direct contact with the founder. Therefore, the actual number of enterprises contacted was lower than 270.

3 2177 words is equivalent to approximately 5.5 pages, Font: Times New Roman, size 12, single line spacing.

References

- Alvord, Sarah H., L. David Brown, and Christine W. Letts. 2004. “Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 40 (3): 260–282. doi:10.1177/0021886304266847.

- André, Kevin, and Anne-Claire Pache. 2016. “From Caring Entrepreneur to Caring Enterprise: Addressing the Ethical Challenges of Scaling up Social Enterprises.” Journal of Business Ethics 133 (4): 659–675. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2445-8.

- Ashoka. 2011. Everyone a Changemaker: 2011 Annual Report. Arlington, VA. https://www.ashoka.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2011_annual_report.pdf.

- Ayob, Noorseha, Simon Teasdale, and Kylie Fagan. 2016. “How Social Innovation ‘Came to Be’: Tracing the Evolution of a Contested Concept.” Journal of Social Policy 45 (04): 635–653. doi:10.1017/S004727941600009X.

- Bacq, S., and F. Janssen. 2011. “The Multiple Faces of Social Entrepreneurship: A Review of Definitional Issues Based on Geographical and Thematic Criteria.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (5–6): 373–403. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.577242.

- Batie, Sandra S. 2008. “Wicked Problems and Applied Economics.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 90 (5): 1176–1191. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8276.2008.01202.x.

- Blok, Vincent, and Pieter Lemmens. 2015. “The Emerging Concept of Responsible Innovation. Three Reasons Why It Is Questionable and Calls for a Radical Transformation of the Concept of Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation 2, edited by Bert-Jaap Koops, Jeroen van den Hoven, Henny Romijn, Tsjalling Swierstra, and Ilse Oosterlaken, 2nd ed., 2: 19–35. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Bos, Colette, Bart Walhout, Alexander Peine, and Harro van Lente. 2014. “Steering with Big Words: Articulating Ideographs in Research Programs.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (2): 151–170. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.922732.

- Burget, Mirjam, Emanuele Bardone, and Margus Pedaste. 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9782-1.

- Chandra, Yanto, and Liang Shang. 2017. “Unpacking the Biographical Antecedents of the Emergence of Social Enterprises: A Narrative Perspective.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (6): 2498–2529. doi:10.1007/s11266-017-9860-2.

- Chatfield, Kate, Elisabetta Borsella, Elvio Mantovani, Andrea Porcari, and Bernd Stahl. 2017. “An Investigation into Risk Perception in the ICT Industry as a Core Component of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Sustainability 9 (8): 1424. doi:10.3390/su9081424.

- Cho, Albert Hyunbae. 2006. “Politics, Values and Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Appraisal.” In Social Entrepreneurship, edited by Johanna Mair, Jeffrey Robinson, and Kai Hockerts, 34–56. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Choi, Nia, and Satyajit Majumdar. 2014. “Social Entrepreneurship as an Essentially Contested Concept: Opening a New Avenue for Systematic Future Research.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (3): 363–376. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.05.001.

- Dacin, M. Tina, Peter A. Dacin, and Paul Tracey. 2011. “Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1203–1213. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0620.

- Dey, Pascal, and Chris Steyaert. 2016. “Rethinking the Space of Ethics in Social Entrepreneurship: Power, Subjectivity, and Practices of Freedom.” Journal of Business Ethics 133 (4): 627–641. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2450-y.

- Dufays, Frédéric, and Benjamin Huybrechts. 2014. “Connecting the Dots for Social Value: A Review on Social Networks and Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 5 (2): 214–237. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.918052.

- European Union. 2007. “Treaty of Lisbon Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community.” European Union. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=OJ:C:2007:306:FULL&from=EN.

- Godin, Benoît. 2015. Innovation Contested: The Idea of Innovation Over the Centuries. New York: Routledge.

- Goldstein, Jeffrey, James K. Hazy, and Joyce Silberstang. 2010. “A Complexity Science Model of Social Innovation in Social Enterprise.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1 (1): 101–125. doi:10.1080/19420671003629763.

- Hoven, Jeroen van den, Klaus Jacob, Laura Nielsen, Françoise Roura, Laima Rudze, Jack Stilgoe, Knut Blind, Anna-Lena Guske, and Carlos Martinez-Riera. 2013. Options for Strengthening Responsible Research and Innovation: Report of the Expert Group on the State of Art in Europe on Responsible Research and Innovation. Luxembourg.

- Kerlin, Janelle A. 2006. “Social Enterprise in the United States and Europe: Understanding and Learning From the Differences.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 17 (3): 246–262. doi:10.1007/s11266-006-9016-2.

- Koe Hwee Nga, Joyce, and Gomathi Shamuganathan. 2010. “The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Start Up Intentions.” Journal of Business Ethics 95 (2): 259–282. doi:10.1007/s10551-009-0358-8.

- Lubberink, Rob, Vincent Blok, Johan van Ophem, and Onno Omta. 2017. “Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Responsible, Social and Sustainable Innovation Practices.” Sustainability 9 (5): 721. doi:10.3390/su9050721.

- Lubberink, Rob, Vincent Blok, Johan van Ophem, Gerben van der Velde, and Onno Omta. 2018. “Innovation for Society: Towards a Typology of Developing Innovations by Social Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9 (1): 52–78. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1410212.

- Macnaghten, P., R. Owen, J. Stilgoe, B. Wynne, A. Azevedo, A. de Campos, J. Chilvers, et al. 2014. “Responsible Innovation Across Borders: Tensions, Paradoxes and Possibilities.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (2): 191–199. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.922249.

- Mair, J., J. Battilana, and J. Cardenas. 2012. “Organizing for Society: A Typology of Social Entrepreneuring Models.” Journal of Business Ethics 111 (3): 353–373. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1414-3.

- Mair, Johanna, and Ernesto Noboa. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: How Intentions to Create a Social Venture Are Formed.” In Social Entrepreneurship, edited by J. Mair, J. Robinson, and K. Hockerts, 121–135. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Meyskens, Moriah, Colleen Robb-Post, Jeffrey A. Stamp, Alan L. Carsrud, and Paul D. Reynolds. 2010. “Social Ventures from a Resource-Based Perspective: An Exploratory Study Assessing Global Ashoka Fellows.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (4): 661–680. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00389.x.

- Newth, Jamie, and Christine Woods. 2014. “Resistance to Social Entrepreneurship: How Context Shapes Innovation.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 5 (2): 192–213. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.889739.

- Oudheusden, Michiel van. 2014. “Where Are the Politics in Responsible Innovation? European Governance, Technology Assessments, and Beyond.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 67–86. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.882097.

- Owen, Richard, Phil Macnaghten, and Jack Stilgoe. 2012. “Responsible Research and Innovation: From Science in Society to Science for Society, with Society.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 751–760. doi:10.1093/scipol/scs093.

- Pavie, Xavier, Victor Scholten, and Daphné Carthy. 2014. Responsible Innovation: From Concept to Practice. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte.

- Pellé, Sophie. 2016. “Process, Outcomes, Virtues: The Normative Strategies of Responsible Research and Innovation and the Challenge of Moral Pluralism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 233–254. doi:10.1080/23299460.2016.1258945.

- Peredo, A. M., and M. McLean. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Concept.” Journal of World Business 41 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007.

- Phillips, W., E. A. Alexander, and H. Lee. 2017. “Going It Alone Won’t Work! The Relational Imperative for Social Innovation in Social Enterprises.” Journal of Business Ethics. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3608-1.

- Phillips, W., H. Lee, A. Ghobadian, N. O’Regan, and P. James. 2015. “Social Innovation and Social Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review.” Group & Organization Management 40 (3): 428–461. doi:10.1177/1059601114560063.

- Ribeiro, Barbara E., Robert D. J. Smith, and Kate Millar. 2017. “A Mobilising Concept? Unpacking Academic Representations of Responsible Research and Innovation.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 81–103. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9761-6.

- Ruggiu, Daniele. 2015. “Anchoring European Governance: Two Versions of Responsible Research and Innovation and EU Fundamental Rights as ‘Normative Anchor Points’.” NanoEthics 9 (3): 217–235. doi:10.1007/s11569-015-0240-3.

- Santos, Filipe M. 2012. “A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Ethics 111 (3): 335–351. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1413-4.

- Von Schomberg, R. 2011. “Introduction: Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields.” In Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields, edited by R. Von Schomberg, 7–15. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://doi.org/10.2777/58723.

- Von Schomberg, R. 2013. “A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In … Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science … , edited by Richard Owen, John Bessant, and Maggy Heintz, 51–74. John Wiley & Sons. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781118551424.ch3/summary.

- Shaw, Eleanor, and Sara Carter. 2007. “Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 14 (3): 418–434. doi:10.1108/14626000710773529.

- Stephan, U., and A. Drencheva. 2017. “The Person in Social Entrepreneurship.” In The Wiley Handbook of Entrepreneurship, edited by G. Ahmetoglu, T. Chamorro-Premuzic, B. Klinger, and T. Karcisky, 205–229. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118970812.ch10.

- Stilgoe, Jack, Richard Owen, and Phil Macnaghten. 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Waddock, Sandra, and Erica Steckler. 2016. “Visionaries and Wayfinders: Deliberate and Emergent Pathways to Vision in Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Ethics 133 (4): 719–734. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2451-x.

- Wickson, Fern, and Anna L. Carew. 2014. “Quality Criteria and Indicators for Responsible Research and Innovation: Learning from Transdisciplinarity.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (3): 254–273. doi:10.1080/23299460.2014.963004.

- Wong, Pak-Hang. 2016. “Responsible Innovation for Decent Nonliberal Peoples: A Dilemma?” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (2): 154–168. doi:10.1080/23299460.2016.1216709.

- Zahra, S., E. Gedajlovic, D. Neubaum, and J. Shulman. 2009. “A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges.” Journal of Business Venturing 24 (5): 519–532. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.007.