ABSTRACT

3D printers are hailed as the next revolutionary technology, but will they be responsible innovations and help decrease poverty and inequality? This paper determines the availability and accessibility of 3D printing technology in low-income communities through public libraries and gives insights on how libraries use 3D printers. By examining the 2013 Digital Inclusion Survey and conducting interviews, we find that libraries are quickly acquiring 3D printers; however, the technology is not being fully adopted by the patrons due to the lack of training, software and practical applications of the technology. Also, we found out that the cost to use a 3D printer in public libraries is relatively low, and does not prevent patrons from accessing the technology. Overall, we believe that libraries will only play a small role in providing availability and accessibility to 3D printing technology for marginalized communities.

Introduction

Public libraries are unique institutions in a country’s innovation system. From early in their inception, public libraries were designed to give broad access to information and knowledge, build community cohesion, and expose people to different cultures and ideas (Wiegand Citation2015). Studies show that libraries provide a variety of benefits to the community. They can contribute to the economic well-being of the neighborhood by helping residents learn job skills, find employement, and start businesses (Baker and Evans Citation2011). Libraries enhance the quality of life of the neighborhood; contribute to the success of local writers, homeschoolers and business professionals; build social capital in the community; and create links between people that enhance social trust (Ishengoma and Mtaho Citation2014; McClure and Bertot Citation1998).

As technology and the means to access information change, libraries are shifting from being book repositories to proactive service providers involved in responsible innovation and learning (Shrestha and Krolak Citation2014). Libraries are often the early adopters of emerging technologies, and many people go to libraries to learn about and demo new technology (Flaherty and Miller Citation2016; Walter Citation2010). If libraries embody responsible innovation philosophies and practices, then their example will impact learning, development and innovation in the surrounding community.

In recent years, some libraries added 3D printers to their collections. 3D printing is an additive manufacturing technique where 3D objects are printed by layering material, such as plastic or metals, to build a 3D shape. The technology has been available for a few decades, but it was very expensive and only used by businesses or extremely dedicated hobbyists (Scalfani and Sahib Citation2013). However, over the last ten years, innovators have developed low-cost 3D printers which make the technology accessible to individual consumers and they are changing the discourse around responsible innovation (de Jong and Bruijn Citation2013; Dickel and Schrape Citation2017). The shift to affordable 3D printers opened new opportunities for research and education, and resulted in a significant movement for libraries to acquire and support the technology. As explained by Moorefield-Lange, Makerspaces and 3D printing can be an inexpensive way for libraries to provide their patrons with ways to explore, create, and innovate (Moorefield-Lang Citation2014).

Problem statement

Although public libraries are rapidly adopting 3D printers, the responsible innovation and science policy communities have not fully explored the technology’s impacts on inequality, nor have they investigated the impact of libraries in responsible technology development. This project examines the role that public libraries play in responsibly diffusing 3D printer technology to marginalized and underserved communities.

We have two main research questions. First, are 3D printers available to patrons in low-income communities in the United States? Availability is a major issue in responsible innovation (Voegtlin and Scherer Citation2017). If a technology is not available to a population, then the technology will exacerbate inequality.

Second, is the technology accessible to patrons in low income communities in the United States? Accessibility is related to availability, but there is a small difference. The accessibility of technology is heavily covered in the disability studies literature and discusses if someone can use a product (Olkin Citation2002; Seelman Citation2000). Even if a product is available to an individual, it is useless if it is not accessible. Is there training to use 3D printers and are the printers cheap enough to be used by patrons?

Our first hypothesis is that, despite the increased adoption of 3D printers in public libraries, libraries in wealthy communities are more likely to have 3D printers than libraries in poor communities, and as a result, the technology is increasing inequality. There is little availability of the technology to marginalized communities.

Our second hypothesis is that even if a library has a 3D printer, the technology will not be accessible to most of the patrons due to the cost of printing and the lack of training to use the printer. To answer these questions, we analyzed survey data and interviewed librarians to map the distribution of 3D printers, understand why they did (or did not) install 3D printing, how the technology was being used, and what was the goal for the technology.

Literature review

Inequality and the digital divide

For a technology to be responsible, it needs to address inequalities that can naturally arise with new innovations. Technological inequality has always existed, and in some fields, like the military, inequality is encouraged (James Citation2007; Woodhouse and Sarewitz Citation2007). One type of technology that has received attention for causing inequality is information communication technologies (ICTs). The digital divide, or inequality in ICTs, began taking shape in the 1990s when computers and the Internet became mainstream (Kinney Citation2010). Institutions quickly adopted ICTs to become more competitive and efficient. Companies bought computers to increase employee productivity and E-commerce opened new markets and business opportunities. ICTs transformed communication, entertainment, and knowledge generation (James Citation2007). With the rise of ICTs, it became clear that wealthy parts of society had more access to the technology while less affluent areas of the world were left behind (James Citation2007). The ‘digital divide’ naturally grew.

Academics, innovators, and government officials have spent significant time battling the digital divide (James Citation2007). Some of the more common solutions are providing low cost computers to marginalized groups, incorporating ICTs in education and training, creating new internet networks and changing the economic incentives for companies to invest in ICT infrastructure in low income communities (Kraemer et al. Citation2009; Poor, Warschauer, and Ames Citation2010; Turpin and Cooper Citation2005). Some of these interventions were successful while others maintained the status quo or increased inequality.

A less discussed solution to the digital divide are libraries. As ICTs spread, public libraries became an entry point to the technology. Libraries adopted high speed internet, computers, e-readers, MP3 players, digital editing software, and recently, 3D printers (Jue et al. Citation1999). Given all the investment in technology, are libraries decreasing the digital divide? In one study, scholars used geographic information system (GIS) mapping techniques to show that there are fewer public libraries in extremely poor areas, partially in response of decreased population density (Jue et al. Citation1999). Another study finds that there is a significant inequality in library funding, staff, and library programing and that libraries in high-income areas receive more funding than libraries in low-income areas (Sin Citation2011).

3d printing in public libraries

3D printers have been hailed as another revolutionary technology for manufacturing, consumption, design and daily life. Many of the novel capabilities stemming from 3D printing help make it a more inclusive and responsible technology (Beyer Citation2014; Huang et al. Citation2013). 3D printers allow individuals to design, customize and print complex shapes without having to build a new manufacturing facility. With traditional manufacturing, it is very expensive to produce a custom product. In comparison, it is much easier to create tailored 3D prints because the designers simply change a part of the 3D model and then reprint the figure (Beyer Citation2014; Huang et al. Citation2013). 3D printing also uses less material than other manufacturing techniques based on subtractive creation processes. Since there is less material used and wasted, 3D printing can be more environmentally friendly than traditional manufacturing (Kreiger and Pearce Citation2013).

3D printing was invented in the 1980s, but recently the technology has received renewed interest due to a variety of changes and improvements in the field (Huang et al. Citation2013). First, many of the 3D printing patents that launched the technology expired in the last ten years. This led to an explosion of new and cheaper 3D printers (Schoffer Citation2016). Second, the printers have gotten faster and use better materials. An item that took hours to print and clean up might now take thirty minutes and be ready to use right out of the machine. Third, there has been a rapid expansion in open source forums that allow people to build their own 3D printers (Weber et al. Citation2013). This fact drives down the market price of printers and pressures companies to produce cheaper consumer 3D printers. These changes increased the diffusion of 3D printers and moved the technology from being a niche device for large companies and enthusiasts to a technology that mainstream consumers operate. Once 3D printing technology became more popular, libraries added them to their inventory. In fact, libraries are adding many design and manufacturing tools and creating Makerspaces and hackerspaces to fulfill their mission in the twenty-first century (Slatter and Howard Citation2013).

There are only a few studies about 3D printers in public libraries and most of them give advice to practitioners on starting 3D printing programs. In one study, the author provides six case studies of how the technology was implemented in libraries across the country. The study discusses some of the insights, logistical challenges and successes of the programs (Moorefield-Lang Citation2014). Another study analyses makerspaces and 3D printing in Australian libraries (Slatter and Howard Citation2013). These are important studies, but they do not delve into the impact the technology has on inequality.

Methods

Our study consists of a quantitative analysis of libraries and 3D printing patents and a qualitative analysis using semi-structured interviews with librarians. For the quantitative analysis, we used two main datasets and several administrative datasets. First, we examined data from 2013 Digital Inclusion Survey conducted by the Information Policy & Access Center at the University of Maryland and the American Library Association (ALA) (Bertot, Real, and Jaeger Citation2016). The survey was sent to public libraries in the USA from September-November 2013, and it asked questions about the library’s infrastructure, technology services and resources, technology training, and other programs and initiatives. The 2013 Digital Inclusion Survey sampled libraries as defined by the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). Bookmobiles, libraries designated as closed in the file, branches that did not have a locale status (urban, suburban, town, rural) designation and territory libraries (e.g. Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands) were removed from the survey. Data were gathered from the libraries on a branch/outlet level, with a 70.1% response rate (Bertot, Real, and Jaeger Citation2016).

The survey contains information on 4,602 libraries across 803 variables. The size and depth of the survey make it a powerful dataset to explore the role of libraries in responsible innovation. In particular, the survey asks whether the library has a 3D printer and we use the responses for this question as one of the main variables in our study. Unfortunately, despite our best intentions, a limitation of the study is we only have data from the 2013 survey. 3D printing development and adoption is changing so rapidly that a cross section analysis only gives a narrow purview of the impacts of 3D printing.

In addition, another limitation of the survey is that the survey is based on self-reported data from librarians. Self-reported answers might lack accurate judgment or be exaggerated. Also, subjects might choose to report a socially acceptable response instead of unpleasant facts. The wording of the questions might even have a different meaning for various people and, therefore, be interpreted differently. Despite these and some other limitations, self-reported data are a source of valuable insight. To ensure the reliability of the data as much as possible, we checked for outliers and eliminated cases with apparent mistakes.

The second major data source we used was the Castle Island Rapid Prototyping Patent database (Grenda Citation2015). This data contains a list of all the 3D printing related patents (about 10,000) in the US Patent Office up to 2015. Each patent entry includes a title, list of inventors, correspondence address, and patent class. This proprietary dataset is one of the most comprehensive 3D printing patent databases and it has been used by other scholars studying 3D printing (Weber et al. Citation2013).

One of the smaller datasets we used lists US State R&D expenditures. The data were taken from the 2013 Survey of State Government R&D, sponsored by the National Science Foundation (NSF) (National Science Foundation Citation2013). Data on median household income were added from 2009–2013 5-Year American Community Survey, U.S. Census Bureau (US Census Bureau Citation2020).

After combining and analyzing the datasets, we mapped the relevant variables using ArcGIS software, and then conducted a logistic regression where the dependent variable is whether the library has a 3D printer (techtdpr). The independent variables in the analysis fall into two main categories, characteristics of the library and characteristics of the surrounding community. First, it is expected that individual library characteristics, like the physical size of the library (sqfeet), total number of PC computers in the library (pactotal) and the number of different types of technology in the library (othertech) will impact the likelihood that the library has a 3D printer. We hypothesize that larger libraries with more computers and technology will be more likely to have 3D printers than small libraries with less technology.

The second category of variables describe the community surrounding the library. Library resources are heavily dependent upon local taxes and the quality of libraries in the same region vary based on local characteristics. At the most local level, there are variables to measure the median household income of the library’s zip code (mhi) and the population of the community surrounding the library (pop). Studies show that poorer areas are less likely to have a library and fewer technology resources (Jue et al. Citation1999; Sin Citation2011). We hypothesize that libraries in wealthier and more populated communities are more likely to have a 3D printer because these libraries have the means to support a 3D printer.

Moving out from the local zip code, we include a variable for whether the library is in a rural community (rural), town (town), suburb (suburb) or city (city) based on the NCES locale codes found in the Digital Inclusion Survey. Libraries in rural communities have fewer computers and less internet access than cities and suburbs(Sin Citation2011), so it is likely that rural libraries will have fewer 3D printers than libraries in other locations. Finally, we examine the R&D climate of the community surrounding the library. If a library is in a state or community with a lot of R&D spending and innovation, as measured in patents, it is hypothesized that the local library will have more technology. Patents and R&D spending are crude proxies for local innovation because patents do not measure informal innovations or non-patentable innovations (Toivanen and Suominen Citation2015). Nevertheless, understanding the relation between the innovation climate around the library and the technology inside a library provides useful information on how libraries mirror existing inequalities or change inequality in the community. It is known that libraries can help community development and empowerment (Abu, Grace, and Carroll Citation2011) but it is less clear whether communities with strong economic development, innovation, and R&D improve the libraries. summarizes the list of variables used in the quantitative analysis.

Table 1. List of the variables used in the data analysis.

In the second part of the analysis, we interviewed librarians from around the country to understand why they installed 3D printers and how library patrons are using the technology. We contacted over 100 libraries from the 4,602 that participated in the survey. We conducted 14 interviews with librarians; four of the interviews were done in person, and ten by Skype or phone. The interviews were conducted in the Fall of 2016 by two interviewers. The interviews were based on semi-structured, open-ended questions that allowed for discussion. Each conversation lasted between 30 and 60 min.

The goal of the librarian interviews was to gain insight about library funding, their community served, technologies available on site, rules, and requirements, decision-making process, and programs offered. To do this, we drew a sample of libraries that considered three factors: 1) whether the library had a 3D printer; 2) median household income of area: Low (less than $40,000), Medium ($40,000-$60,000), High (more than $60,000); and 3) the community of the library (town, rural, suburban, and city). shows the breakdown of libraries by community type. Of the librarians we interviewed, 10 of the them had working 3D printers, one of the libraries had a broken 3D printer, one library borrowed their 3D printer from the central system, and two libraries did not have 3D printers. It was important to interview a variety of libraries that both have and do not have 3D printers so we can understand the reasons different libraries adopted the technology and whether the technology is accessible. Unfortunately, we were not able to get representation from all types of the libraries because of the low response rate from the librarians. The low response rate is a limitation of the study and it could bias the results of the qualitative data.

Table 2. Descriptive information about the libraries in the analysis.

To minimize non-response bias, we slightly adjusted the interview solicitation and interview questionss for libraries with and without 3D printers. We contacted libraries without 3D printers and asked for an interview about the technology in their branch. The interview protocol for libraries with 3D printers asked about the libray’s technology offerings for patrons, but we also included a series of questions about 3D printers.

After conducting the interviews, we transcribed and coded them using the RQDA package for R Studio. The list of the codes with descriptions can be found in .

Table 3. List of the Codes and questions used in transcribing and coding of interviews with librarians.

Results and discussion

Quantitative analysis

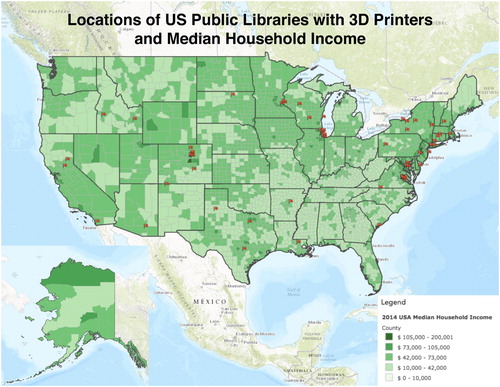

Using the survey and patent data, we mapped public libraries with 3D printers with median household income by county (see in Attachments). The libraries with 3D printers are primarily found on the East Coast and/or in large metropolitan areas like Chicago, Minneapolis, and Denver. In 2013, there are large swaths of the country where public libraries did not have a 3D printer.

Figure 1 This map shows the locations of US public libraries overlayed on a heat map showing median household income.

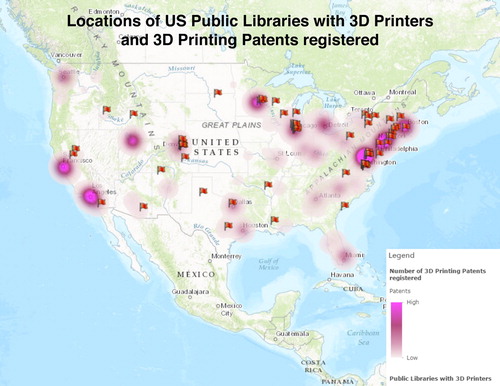

We also mapped public libraries with 3D printers and 3D printing patents registered by zip-code (see in Attachments). There is no clear pattern of correlation between locations of libraries with 3D printers and registered 3D printing patents. There are big clusters of libraries with 3D printers and patents grouped around large metropolitan areas like Denver, Chicago, Washington DC, and New York.

Figure 2 This map shows the locations of US public libraries with 3D printers overlayed on a heat map showing registered 3D printing patents in the US.

The results of logistic regression analysis are in . The analysis shows the only variables that are statistically significant are othertech, city, and pop (see for variables description). In the analysis, the reference group for location is ‘suburbs’. To verify the model was well specified, we ran a Homer-Lemeshow goodness of it test and found no evidence of a bad fit (Bartlett Citation2014; Yu, Xu, and Zhu Citation2017).

Table 4. Results of the multivariate logistic regression.

The most important variable in the model is othertech. This variable shows that increasing the number of other technology types in a library, such as e-readers, tablet computers, or video editing software, by 1 unit increases the estimated odds of the library having a 3D printer by a factor of 1.87, holding the other variables in the model constant. This result is not surprising. Some public libraries are known for being cutting edge and having numerous technologies. It is very likely that libraries with a propensity for acquiring new technology will also have a 3D printer.

The model also shows that city libraries are less likely than suburban libraries to have 3D printers. It is not clear why city libraries are less likely than suburban libraries to have 3D printers, but one of the reasons might be the necessity for city libraries to spend resources on other services for patrons. In cities, libraries may use more resources on activities like career support and printing official documents, while suburban libraries have space and resources to invest in novel technologies.

Surprisingly, the median household income of the community surrounding the library is not statistically significant, and it is not highly correlated with other variables in the model (see in Attachments). This result is unexpected because public library budgets usually rely heavily on local property taxes (Sin Citation2011). Wealthier neighborhoods have a larger tax base per capita which allows the libraries to buy more technology and host a wider array of programs. Our results could be inconclusive for two major reasons. First, the survey was conducted in 2013 and the libraries with 3D printers were very early adopters, and therefore, their adoption of 3D printers has little to do with the wealth of the community. Rather, the mindset of the individual librarians and their propensity to adopt technology may impact their technology purchases. Second, although studies show that there is a relationship between community income and public library funding, the relationship between community income level and the public libraries spending on technology is less clear (Sin Citation2011). A variety of political and cultural factors could impact technology adoption in libraries.

Table 5. Correlation between variables used in the analysis.

State R&D (rd) and 3D printing patents (pat) had no impact on whether libraries in the area adopted 3D printers. Again, this is an unexpected result. In general, it is easy to reason that communities with high levels of R&D and 3D printing patents would be technologically sophisticated, and therefore, the public libraries in those areas would also be technologically advanced. However, we find no evidence to support this conclusion.

Qualitative analysis

The second part of the analysis relied on 14 interviews with librarians from a variety of communities that both have and do not have 3D printers (see for details about the libraries). The interviews give insights into the availability and accessibility of 3D printing by asking about the purpose, operations, and challenges of having a 3D printer in the library. Below is a summary of the main findings.

Getting a 3D printer

To understand the availability and accessibility of the printers, an essential interview question is, ‘Did your library get a 3D printer, why or why not?’. Libraries had a variety of reasons for getting 3D printers, but their answers centered on providing new technologies to their patrons. Librarians see their role as extending beyond providing books and filling a technology gap. As one librarian said,

I think it is a huge part of our library, our mission – educating and providing information. I think in our world, technology is such a part of that now, that exposing people to different things and granting them access to things that they may not have at home is one of our biggest jobs here.

For libraries that did not get 3D printers, their primary reason for foregoing the technology is that it is too expensive. This finding holds in both low-income and high-income communities. In one wealthy community, the librarian said ‘That is probably why we would not buy it. There are other things we need before we get a 3D printer.’ In a low-income area, the library said, ‘ … . But money is an issue. Not only buying it but keeping it in a working condition and buying supplies.’

Another reason why libraries did not get 3D printers is that they lacked some key component to maintain a 3D printer. Some libraries have very little floor space, and the physical constraints of the library make adding a printer very challenging. Other libraries lack the staff to run a 3D printer. We found that libraries with 3D printers dedicated significant amounts of staff hours to maintaining and operating them. Before a printer can be installed, the staff must be trained to operate it and troubleshoot any problems. In general, libraries require 1–2 staff members to dedicate a part of their day to care for the machine. One librarian mentioned they did not get 3D printers because there was no demand in the community to buy and operate one. Their community would rather have access to a new computer or faster Internet. Finally, one interesting comment from a librarian in a wealthy community was that some patrons already have access to a 3D printer at school or even at home. In this case, the library bought the 3D printer as an on-site technology demonstration. Patrons could demo the printer in order to make an informed decision about buying it for a personal use.

Once a library decided to get a 3D printer, they used a variety of avenues to secure the device. Libraries in low-income communities often relied on the largess of donors or the city’s central budget. In one low-income community, the library received a grant to buy the 3D printer, and in another low-income community library, their larger library system provided them a 3D printer. Libraries in richer communities usually bought the 3D printer out of their operating budget, however, in a few cases they also relied on grants or donations from the community.

Operation of 3D printing

The libraries have a variety of ways to use their 3D printers. While some libraries have very centralized and controlled operations, others are more open with the management of their devices. At one end of the spectrum, some libraries use 3D printers simply as a demonstration project. At these branches, the library will display the technology in the lobby, print out preselected designs, and discuss how to use it. However, at these libraries, patrons cannot use the technology. The second type of library lets patrons submit print jobs, and the librarians will print them out. This approach allows the library to have direct control over the machine to ensure that nothing breaks and the 3D printer is not misused. These libraries have rules that limit the size of the object, but in general, patrons can submit any appropriate design. On average, it takes a day or two for a library to print a design. In the rare cases, one or two weeks are required. For example, one librarian mentioned that they had a two-week backlog for 3D printing the models. Finally, at the other end of the spectrum, there are a few libraries that allow patrons to operate the 3D printer independently. Only one of the libraries we interviewed allowed patrons to print their own designs without direct oversight from library staff. However, before the patron could use the printer without supervision, they had to complete a training program. The training has a series of courses and tests to verify that the patrons can safely operate the 3D printer without supervision. However, at the time of our interview, no patron had completed the training program.

To keep the printer operational, libraries charge a small sum to use the printer. Libraries either charge based on how long the printing takes (for example, $1 per hour) or based on the amount of material used (for example, $0.25 per gram used). With these models, printing a smart phone case costs about $4. Regardless of the pricing structure, none of the interview participants mentioned that the price of the printer limited demand. Also, on numerous occasions, the librarians said the reasoning behind the user fee was not to make a profit, but simply a way to cover the cost of operating the printer. If a patron had financial difficulties, the library might waive the fee.

Training and software

All the libraries in the study with 3D printers offer introductory classes in downloading 3D print designs from websites, such as Thingiverse, and brief discussions about properties of good 3D printing designs. Librarians emphasize topics like creating objects with the necessary support structure and building hollow structures. The courses tend to be geared towards children and teenagers. In fact, only one library we interviewed has 3D printing activities specifically designed for adults.

The libraries are eager to use free and open source software like TinkerCad and Sketchup. Librarians believe this software is easier to teach and to learn the basics of design. Libraries tend to stay away from more robust software like AutoCAD. The librarians mentioned that though rigorous software is great for 3D printing, it takes too long for patrons to learn it and the libraries do not have the staff to train patrons on these tools. In addition, libraries have high turnover and dropout rates in the courses, so they want to teach patrons on quick and easy to use software.

Problems

Librarians described patrons as having mixed feelings about 3D printers. At first, patrons are very interested in the technology. Librarians shared countless stories of children sitting in front of a 3D printer waiting for their design to be finished. When libraries have courses on 3D printing, they are overrun with requests to attend the classes. But the hype for technology quickly wanes as patrons run into problems. One issue is that 3D printing is still an emerging technology, and a variety of technical problems make it difficult to use. For example, one widespread issue is that the printer head gets clogged and must be fixed. This issue shuts down the printer until a librarian can repair it.

Another technical problem is the print job may have an error and get botched in the process. This forces the library to rerun the job which takes up resources and causes delays for subsequent 3D printings. One librarian mentioned, ‘For us, the greatest challenge was the actual functionality of the machine. We had to replace a couple of parts, so for us, troubleshooting and finding out why it is not working [was the greatest issues].’

A third problem is there is a perception gap between the technology’s capabilities and the expectations of the public. Patrons expect 3D printers to be easy to operate and they do not realize creating a design is a challenging process that requires knowledge of 3D design principles and computer aided design (CAD). Creating a customized structure involves hours of designing on CAD, and then once the printing begins, there is no guarantee that the printed object will turn out right.

In addition, patrons must design an item that fits within the constraints of the printer and has the proper structural integrity to be printed with the given materials. 3D printing advocates regularly tout that 3D printers can create shapes that were previous impossible manufacture, but they cannot defy the laws of physics to print a file. These challenges are a major hurdle for people to use the printers. One library commented, ‘The complexity of using 3D Printing requires some level of skills and knowledge. There might be some problems occurring during the printing process, and people just give up.’

Other patrons overestimated the quality of the printer. They assumed the 3D printers will produce perfectly smooth, production level items. Cheaper 3D printers, which are the type public libraries tend to own, print objects using plastics like polylactic acid (PLA) or acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS). The limitations of the printer make it unreasonable to print something that requires precision or more robust materials. As a result, patrons are not using the 3D printers to create prototypes or finished products. Rather, the printers are used by children to print toys.

A sixth problem with 3D printers is patrons often do not understand the unique design power of 3D printers and tend to use 3D printers just to create objects they currently use: ‘A lot of people do not understand what it is, and why you do the 3D Printing. Also, people do not know how to do a 3D design.’ They do not realize the nature of 3D printing allows them to create previously unthinkable shapes. For example, a company recently created a key with the teeth in an outside shell. This type of key could only be 3D printed (The Economist Citation2017 ).

Below is a list of some other problems that make 3D printers challenging in libraries:

-

The extruder of the printer can be very hot, and it is a safety hazard for children at the library.

-

The technology is still expensive, and with rapid development, it requires constant investments: ‘It is technology, so it is updating quickly. However, because of high price, the library is not able to update the 3D printer as fast as the technology is updating.’

-

The printers can be loud and distracting in library spaces. As one of the interviewed librarians mentioned, ‘The noise associated with the printing process bothers people.’

-

Navigating copyright issues with 3D print designs is complicated. It is a librarian’s responsibility to ensure no illegal or inappropriate designs are printed at the library. It is challenging to know whether the object is illegal to print.

-

It can take hours to print an object. Librarians told stories of parents angrily waiting around as the printer had another 30 min to go.

Inequality

Throughout the project, librarians were very keen to say that part of their primary mission was to provide the technology to all their patrons and act as forces to decrease inequality. All the librarians interviewed addressed various types of inequality in their statements. One librarian said:

In our community, there are a lot of people who do not have computers at home, who do not have the Internet, and our role is to bring it to them for free, to put them on the equal standing as people who have it at home. Yes, it is less convenient to come to the library, but it is free.

Other librarians mentioned that they play a powerful role in mitigating horizontal inequalities like those based on age, gender, race or religious affiliation. ‘The library is open to everyone regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, and economic status. The library is always there to strengthen democracy and to make knowledge available for all citizens. We don’t discriminate against anyone.’

Another librarian stated,

… we are trying to make sure that everyone in our community is served and has access to these technologies. It might seem like a lot of these are focused more towards males, but we are trying to make sure that females also have an opportunity to realize that working in technology is not something that is just for males even if it looks that way.

One aspect of inequality the libraries do not fully address is that libraries themselves are in spatially diverse regions that perpetuate inequality. As stated before, libraries in wealthy communities tend to have more resources than libraries in poor communities (Sin Citation2011). Libraries in this study mitigate the effect by letting all patrons use their resources. From our interviews, only one library restricted the access to 3D printer to its patrons.

Conclusion and discussion

This study discusses library adoption of 3D printing. The central question of the research project is if 3D printers are available and accessible to low-income communities through the US public libraries. Based on the statistical analysis of the available data, we cannot confirm the first hypothesis. We are unable to determine whether libraries in affluent communities are more likely to have 3D printers than libraries in poor communities. However, from the statistical analysis, we can determine that libraries with lots of technologies, areas with larger populations, and the suburbs compared to cities are more likely to have a 3D printer.

The qualitative analysis gives slightly different results than the quantitative analysis and it supports the hypothesis that libraries in wealthy communities are more likely to have a 3D printer than poor communities. Librarians mentioned that funding and budget constraints are the main factors determining whether they purchase a 3D printer. Libraries in wealthy communities tend to have larger budgets than libraries in middle and low-income communities, and therefore, they can afford to buy a 3D printer. As a result, the technology could make the social and educational gap between poor and wealthy communities even bigger. The relationship between the wealth of the local community and owning a 3D printer is strongly influenced by the employees at the library, and the library’s local support network.

Scholars need to further study the relationship between library funding and technology to resolve the differences we found between the quantitative analysis and the qualitative analysis.

The second hypothesis is that even if a library has a 3D printer, the technology would be inaccessible to patrons because it is too expensive to print an item or patrons are not trained to use the technology. This hypothesis is partially confirmed. We find libraries provide very little training on 3D printing. They tend to offer introductory courses on finding and printing objects, but they provide few instructions on creating new printable 3D objects. This circumstance corroborates that libraries will not be intermediaries to decrease inequality in 3D printing. However, to counter this point, there is evidence public libraries will make the technology accessible. In general, the 3D printer is open to any person regardless of their membership status, and it is not very expensive. These factors alone will not make the technology accessible, but it does lower the barriers preventing people from using a 3D printer.

Public libraries are important spaces that allow everyone, including people from marginalized groups, to use technology. In the past, public libraries were key institutions for reducing the ICT digital divide, but will they overcome the digital divide that arises in 3D printing? Given the cost and training involved to use 3D printers, public libraries will only provide a basic level of access to the technology. Moreover, library resources vary tremendously across regions and communities based on income level. Though income is not a significant factor in the statistical model at this point, it is possible that as the technology spreads, the median household income of a community will become a major factor in the diffusion of the technology. Public libraries can help decrease technology inequality, but these institutions cannot solve the 3D printing digital divide. We think that other institutions, like schools or Maker Spaces, are better positioned to solve the 3D printing divide but answering this questions is beyond the scope of our current research.

Given these findings, how do innovation scholars, policymakers and librarians ensure that the 3D printers have a bigger impact on responsible innovation, decrease local poverty and inequality, and increase learning, education and accessibility in their communities? One policy recommendation is that policymakers need to continue to invest in libraries and help those institutions evolve as technology develops. For the most part libraries actively embrace their evolving role in society (Erich Citation2015; Vårheim, Steinmo, and Ide Citation2008). They quickly adopt new technologies and are converting old spaces to community rooms, makerspaces, and active learning areas. However, libraries cannot develop these spaces and buy the technology if they are not funded. It is especially important to fund to libraries in low income communities. Often these communities are the last to receive new technology because they do not have the budget for it.

Another recommendation is to give libraries the staff and resources to train people to use 3D printers. The technology is time consuming and if the staff do not have adequate resources to train people to use 3D printers, the technology will be underutilized.

Finally, libraries need to ensure that the technology is accessible and they have strategies to do outreach so that people will use the printer. They must keep the price of using a 3D printer low so that cost is not a prohibitive factor. They also need classes for a variety of patrons, not just kids and teens. Libraries could work with local schools, universities and makerspaces to create a pipeline of 3D printer training. Libraries should partner with local businesses to help them see business applications for 3D printing. The library could be the first place that a small business goes to prototype a new product on a 3D printer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Thomas Woodson is an assistant professor in the Department of Technology and Society at Stony Brook University. He investigates the effects of technology on inequality throughout the world and the causes/consequences of inclusive innovation.

Nataliia Telendii is pursuing her Ph.D. degree in Technology, Policy, and Innovation at Stony Brook University, Department of Technology and Society. Her major research interests lay in the area of applications of Technologies and Innovations in Education and Development, Distance Learning, and Professional Development.

Robert Tolliver is the Sciences Librarian at North Dakota State University and has his PhD in geology. His research interests include the science information lifecycle, geoscience information, and scientist/librarian research collaborations.

References

- Abu, R. , M. Grace , and M. Carroll . 2011. “The Role of the Rural Public Library in Community Development and Empowerment.” International Journal of the Book 8 (2): 63–74. doi: 10.18848/1447-9516/CGP/v08i02/36863

- Baker, D. , and W. Evans . 2011. Libraries, Society and Social Responsiblity. In: Libraries and Society . Oxford : Chandos Publishing.

- Bartlett, J. 2014. The Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness of Fit Test for Logistic Regression. Accessed December 20, 2017. http://thestatsgeek.com/2014/02/16/the-hosmer-lemeshow-goodness-of-fit-test-for-logistic-regression/ .

- Bertot, J. C. , B. Real , and P. T. Jaeger . 2016. “Public Libraries Building Digital Inclusive Communities: Data and Findings From the 2013 Digital Inclusion Survey.” The Library Quarterly 86 (3): 270–289. doi:10.1086/686674.

- Beyer, C. 2014. “Strategic Implications of Current Trends in Additive Manufacturing.” Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering 136 (6): 064701. doi:10.1115/1.4028599.

- de Jong, J. P. J. , and E. Bruijn . 2013. “ Innovation Lessons From 3-D Printing.” M I T Sloan Management Review: MIT’s Journal of Management Research and Ideas 54 (2): 43–52.

- Dickel, S. , and J. F. Schrape . 2017. “The Renaissance of Techno-Utopianism as a Challenge for Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 4 (2): 289–294. doi:10.1080/23299460.2017.1310523.

- The Economist . 2017. A 3D-printed Key that Can ‘t be Copied.

- Erich, A. 2015. “The Public Library and its Role in the Community.” Library and Information Science Research 19 (1): 27–33.

- Flaherty, M. , and D. Miller . 2016. “Rural Public Libraries as Community Change Agents: Opportunities for Health Promotion.” Journal of Education for Library and Information Science Online 57 (2): 143–150. doi:10.12783/issn.2328-2967/57/2/6.

- Grenda, E. 2015. RP Intellectual Propety Data Products. Accessed July 1, 2015. http://www.additive3d.com/rpml.htm .

- Huang, S. H. , P. Liu , A. Mokasdar , and L. Hou . 2013. “Additive Manufacturing and its Societal Impact: A Literature Review.” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 67 (5–8): 1191–1203.. doi: 10.1007/s00170-012-4558-5

- Ishengoma, F. R. , and A. B. Mtaho . 2014. “3D Printing: Developing Countries Perspectives.” International Journal of Computer Applications 104 (11): 30–34. doi:10.5120/18249-9329.

- James, J. 2007. “From Origins to Implications: Key Aspects in the Debate Over the Digital Divide.” Journal of Information Technology 22 (3): 284–295. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jit.2000097.

- Jue, D. K. , C. M. Koontz , J. A. Magpantay , K. C. Lance , and A. M. Seidl . 1999. “Using Public Libraries to Provide Technology Access for Individuals in Poverty : A Nationwide Analysis of Library Market Areas Using a Geographic Information System.” Library & Information Science Research 21 (3): 299–325. doi:10.1016/S0740-8188(99)00015-8.

- Kinney, B. 2010. “The Internet, Public Libraries, and the Digital Divide.” Public Library Quarterly 29 (2): 104–161. doi:10.1080/01616841003779718.

- Kraemer, B. Y. K. L. , J. Dedrick , P. Sharma , et al. 2009. “One Laptop Per Child : Vision vs . Reality.” Communications of the ACM 52 (6). ACM: 66–73. Accessed November 15, 2011. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1516063 . doi: 10.1145/1516046.1516063

- Kreiger, M. , and J. M. Pearce . 2013. “Environmental Life Cycle Analysis of Distributed Three-Dimensional Printing and Conventional Manufacturing of Polymer Products.” ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering 1: 1511–1519. doi:10.1021/sc400093k.

- McClure, C. R. , and J. C. Bertot . 1998. Public library use in Pennsylvania: Identifying uses, benefits, and impacts. Final report. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED419548 .

- Moorefield-Lang, H. M. 2014. “Makers in the Library: Case Studies of 3D Printers and Maker Spaces in Library Settings.” Library Hi Tech 32 (4): 583–593. doi:10.1108/LHT-06-2014-0056.

- National Science Foundation . 2013. 2013 Survey of State Government R&D. Alexandria, VA. https://www.nsf.gov/statistics/staterd/ .

- Olkin, R. 2002. “Could you Hold the Door for me? Including Disability in Diversity.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 8 (2): 130–137. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.130

- Poor, W. S. , M. Warschauer , and M. Ames . 2010. “Can One Laptop Per Child Save the.” Journal of International Affairs 64 (1): 33–51.

- Scalfani, V. F. , and J. Sahib . 2013. “A Model for Managing 3D Printing Services in Academic Libraries.” Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship Spring , doi:10.5062/F4XS5SB9.

- Schoffer, F. 2016. “How Expiring Patents are Ushering in the Next Generatio of 3D Printing.” TechCrunch. https://techcrunch.com/2016/05/15/how-expiring-patents-are-ushering-in-the-next-generation-of-3d-printing/ .

- Seelman, K. D. 2000. “Science and Technology Policy: Is Disability a Missing Factor?” Assistive Technology 12 (2): 144–153. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10400435.2000.10132020 .

- Shrestha, S. , and L. Krolak . 2014. “The Potential of Community Libraries in Supporting Literate Environments and Sustaining Literacy Skills.” International Review of Education 61 (3): 399–418. doi: 10.1007/s11159-014-9462-9

- Sin, S. C. J. 2011. “Neighborhood Disparities in Access to Information Resources: Measuring and Mapping U.S. Public Libraries’ Funding and Service Landscapes.” Library and Information Science Research 33 (1). Elsevier Inc.: 41–53. doi:10.1016/j.lisr.2010.06.002.

- Slatter, D. , and Z. Howard . 2013. “A Place to Make, Hack, and Learn: Makerspaces in Australian Public Libraries.” The Australian Library Journal 62 (4): 272–284. doi:10.1080/00049670.2013.853335.

- Toivanen, H. , and A. Suominen . 2015. “The Global Inventor gap: Distribution and Equality of World-Wide Inventive Effort, 1990-2010.” PloS one 10 (4): e0122098. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122098.

- Turpin, T. , and R. Cooper . 2005. “Technology, Adaptation, and Public Policy in Developing Countries: The ‘Ins and Outs’ of the Digital Divide.” Minerva 43 (4): 419–427. doi:10.1007/s11024-005-2471-x.

- US Census Bureau . 2020. American Community Survey 2009-2013 . Washington, DC : US Census Bureau. Accessed March 5, 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ .

- Vårheim, A. , S. Steinmo , and E. Ide . 2008. “Do Libraries Matter? Public Libraries and the Creation of Social Capital.” Journal of Documentation 64 (6): 877–892. doi:10.1108/00220410810912433.

- Voegtlin, C. , and A. G. Scherer . 2017. “Responsible Innovation and the Innovation of Responsibility: Governing Sustainable Development in a Globalized World.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (2). Springer Netherlands: 227–243. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2769-z.

- Walter, V. A. 2010. Twenty-First-Century Kids, Twenty-First-Century Librarians . American Library Association. https://www.amazon.com/Twenty-First-Century-Kids-Librarians-Virginia-Walter/dp/0838910076, https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C31&q=+Twenty-First-Century+Kids%2C+Twenty-First-Century+Librarians&btnG=.

- Weber, C. L. , V. Pena , M. K. Micali , et al. 2013. The Role of the National Science Foundation in the Origin and Evolution of Additive Manufacturing in the United States. Alexandria, VA.

- Wiegand, W. A. 2015. Part of Our Lives: A People’s Hstory of the American Public Library . Oxford : Oxford University Press.

- Woodhouse, E. , and D. Sarewitz . 2007. “Science Policies for Reducing Societal Inequities.” Science & Public Policy (SPP) 34 (2). Beech Tree Publishing: 139–150. doi:10.3152/030234207X.195158data doi: 10.3152/030234207X195158

- Yu, W. , W. Xu , and L. Zhu . 2017. “A Modified Hosmer–Lemeshow Test for Large Data Sets.” Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods 46 (23). Taylor & Francis: 11813–11825. doi:10.1080/03610926.2017.1285922.