ABSTRACT

This paper considers Responsible Innovation (RI) in relation to the design, construction and use of new schools. Drawing on empirical findings from recent international research we apply four dimensions of a RI Framework to gain a more specific understanding of RI in new school design and identify what might guide future innovation. Our analysis suggests that professional learning, evidence and participatory practices are important for engaging users in design processes. Flexibility and autonomy are key for adapting designs for occupation and for sustainability. Transparent value-based decisions are integral to aligning education agendas with school designs and educational practices. We believe RI offers a frame to think about how we might address challenges of alignment going forward. We conclude our analysis with a call for cross-disciplinary and multi-sectoral applied research, integrating expertise across education, data science, and architecture and design, and through which future-resilient design and successful occupancy can be supported.

Introduction

Innovation in education is on-going and critical to the improvement in equity and quality of outcomes across educational sectors (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Citation2019). Innovation in education and its associated policy initiatives are in response to the global trends that shape the future of our learners (Vincent-Lancrin et al. Citation2019). The OECD's international programme aims to prepare students as lifelong learners who have global competencies that will equip them for success in the twenty-first century (OECD Citation2017; Schleicher Citation2018). In our rapidly changing world this goal presents significant challenges for educational systems which are responsible for educating an increasing and diverse student population for an unknown future. To meet these challenges, educational systems in many countries have invested in the innovative design and construction of schools. Some examples include: Building the Education Revolution (BER) infrastructure programme in Australia (ANAO Citation2010); Building Schools for the Future programme in England and Wales (DfES Citation2003) and Innovative Learning Environments in Canada and New Zealand (OECD Citation2017). Schools built under these schemes have been purposefully designed to create state-of-the-art environments that will foster the development of twenty-first century learning competencies, namely: communication, collaboration, critical thinking and creativity and that can be adapted for the needs of tomorrow's learners. This paper draws on empirical findings from recent international research in relation to the design and construction and use of new schools to gain a more specific understanding of Responsible Innovation (RI) in new school design and identify what might guide future innovation.

Innovation and responsibility in school design

Innovative school learning environments have been variously termed as modern learning environments, contemporary learning environments, new generation learning environments, flexible learning environments, and twenty-first century learning environments, with common features of future-focused design (Byers et al. Citation2018; Gislason Citation2010). The OECD programme on innovative learning environments (Citation2013, Citation2017) has likely resulted in wider adoption of this term internationally (Mulcahy and Morrison Citation2017).

While innovation in school design has become a key feature of international education policy, there are competing debates on what designs will achieve the policy intent (Benade and Jackson Citation2017). The predominant design philosophy has emphasised open, flexible, aesthetically pleasing and comfortable learning spaces, that are integrated with technology and that can be organised in various ways to foster a wider range of teaching and learning experiences (Benade and Jackson Citation2017). Compared with the traditional schools, it is expected that students in ‘innovative’ learning environments will spend more time collaborating with others and working individually to design their own learning and less time being taught in a teacher-led whole class setting. These forms of active learning may translate into beneficial learning outcomes, such as improved knowledge retention and academic performance (Byers et al. Citation2018; Kariippanon et al. Citation2019).

Research evidence that these physical spaces do make a difference to learning is complex and not yet fully understood (Woolner, Thomas, and Tiplady Citation2018). Although there is some evidence that these innovative physical spaces can influence educational practices and students’ perceptions of their learning (Byers et al. Citation2018), the research findings are far from straightforward. Our understanding is evolving through a growing body of research framed by diverse theoretical frameworks and methodologies being undertaken. Researchers most notably in Australia, (e.g. Byers et al. Citation2018; Deed and Lesko Citation2015; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015) New Zealand (Benade Citation2019; Benade and Jackson Citation2018; Charteris, Smardon, and Nelson Citation2017) and the U.K. (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Woolner, Thomas, and Tiplady Citation2018) but also in the European contexts of the Netherland (Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017), Austria (Schabmann et al. Citation2016), Germany (Reh, Rabenstein, and Fritzsche Citation2011), and Finland (Mäkelä et al. Citation2018) are building a significant body of evidence to improve innovation in new school design and use.

Increasingly, these studies have provided evidence that the organisational, social and cultural aspects of individual schools can influence how the physical spaces are used in different contexts (Blackmore et al. Citation2011; Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2017; Mulcahy Citation2016). When these conditions are aligned with system agendas and designs it is expected that schooling will result in engaged students achieving deep learning (Byers et al. 2018b; Kariippanon et al. Citation2019; OECD Citation2015). In order to guide future planning decisions, we need to better understand how innovations in school design align with different users and contexts. We also need to consider how today's schools might be able to respond to changed conditions in the future. While change in response to innovation has long been a feature of education and extensively documented (Elmore Citation1996; Elias et al. Citation2003; Fullan Citation2016), in the context of school design ensuring that innovation is introduced responsibly is far less visible.

Responsible Innovation is an emerging concept that aims to balance economic, social, cultural and environmental needs during innovation to result in ‘more responsible solutions for meeting the challenges’ of the future (Lubberink et al. Citation2019, 179). Around the globe there have been growing and significant efforts around Responsible Innovation (RI) (Fisher Citation2020). Since its inception, RI has been variously defined and debated in both policy and scholarly contexts (Fisher Citation2020). A fundamental idea emphasised by most approaches to RI is inclusion (Valkenburg et al. Citation2020). Frameworks developed to shape RI processes include stakeholder views for building knowledge, anticipating and managing future needs (von Schomberg Citation2013; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013) and to achieve a better alignment between the aims of the innovation and the values of diverse users (Ribeiro et al. Citation2018). The RI framework developed by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013), has been widely adopted and applied to a wide range of cultural and political contexts. The RI framework by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) provides four dimensions: Anticipation, inclusion, reflexivity and responsiveness. The authors emphasised that all four dimensions are connected and should be considered as part of an integrated framework.

Anticipation ‘involves systematic thinking aimed at increasing resilience, while revealing new opportunities for innovation and the shaping of agendas for socially-robust risk research’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1570). Anticipation involves considering the potential impacts of an innovation before its introduction along with potential opportunities for on-going evaluation and the shaping of socially robust innovative solutions. Anticipation is thus ‘distinguished from prediction in its explicit recognition of the complexities and uncertainties … ’ in the social environment and the need for examination of both future intended and unintended and or unfavourable consequences of the innovation (p. 1571). In the context of LE, anticipation might engage planners and architects in critically assessing the potential impacts of the school design for a diversity of contexts and different user groups and for expected changes (e.g. increase or decrease in student population) and unexpected conditions (e.g. floods, wildfires, or a pandemic).

Reflexivity ‘at the level of institutional practice, means holding a mirror up to one's own activities, commitments and assumptions, being aware of the limits of knowledge and being mindful that a particular framing of an issue may not be universally held’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1571). Reflexivity is built through mechanisms that facilitate critical examination of the education policies, standards, values, beliefs and assumptions that are held at the institutional, school and individual user levels and that guide the school designs and educational practices.

Inclusion of ‘public and stakeholder voices to question the framing assumptions not just of particular policy issues but also of participation processes themselves’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1572). The expectation is that the participatory processes of inclusion can bring to light various points of view and differences in positions of power. It is suggested that this kind of engagement can improve the implementation of the innovation. The education sector has long engaged in various stakeholders including: teachers, principals, parents, students and various disability and community groups in inclusive processes to inform policy and the development of practice guidelines. In the context of building new schools, this dimension calls for incorporating participatory processes that engage various stakeholders in the design, build and occupation of schools.

Responsiveness ‘Responsible innovation requires a capacity to change shape or direction in response to stakeholder and public values and changing circumstances’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1572). Making adjustments to innovation is inevitable and an important part of any innovation in our increasingly fast-paced and rapidly changing world. In school design, the need to be futures focused and adaptive to evolving changes in perspectives, needs and the environment is integral to innovation in school design.

This framework anticipates multiple effects of change on the basis of inclusive participation that values diverse stakeholder perspectives and that fosters reflexivity (Ludwig and Macnaghten Citation2020). These dimensions appear to be particularly appropriate to frame and assess empirical findings of the experiences of those involved in newly designed schools. Our work echoes that of Demers-Payette, Lehoux, and Daudelin (Citation2016) application to the health care system. There are a few examples of the application of RI to frame and guide education policy and development. (e.g. in higher education Richter, Hale, and Archambault Citation2019), in science education (Heras and Ruiz-Mallén Citation2017), and in engineering education (Hallinan et al. Citation2019). It is not clear, however, how a RI framework such as Stilgoe, Owen and Macnaughten's might translate to the context of innovation in school design.

Method

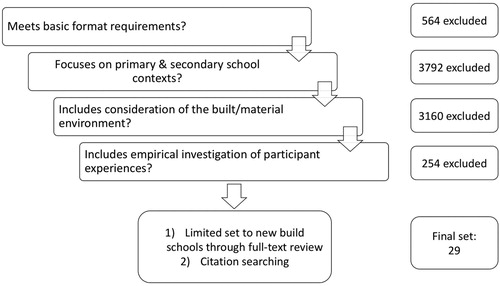

We systematically identified empirical papers focusing on the experiences and perspectives of participants involved in the design and occupancy of new-build schools designated as innovative or flexible learning spaces. We limited our review to recent peer-review research published in the last five years, from 2015 to 2019, including online publication in advance of print date. In order to ensure comprehensive representation of the international research literature, we performed database searches, followed by reference list searches and cited reference searches.

We developed a set of search terms focused on participant experiences in school learning environments, through consulting related literature reviews (Byers et al. Citation2018) and reading abstracts and keywords of relevant articles already gathered through a previous, non-systematic review of the international literature. We selected broad search terms that would capture the diversity of terms in use across international school systems. For a summary of keywords used in our search process, as well as operational definitions of terms, refer to and .

Table 1. Search terms used in comprehensive database searches. Including an asterisk character (*) permits multiple endings for search terms (e.g. family and families).

Table 2. Operational definitions of terms.

The following questions guided our research:

-

How are the dimensions of responsible innovation applied in the design and occupation of the newly built schools?

-

What are the educational needs and outcomes/challenges/processes reported/?

-

What dimensions of the RI model can be applied to support the future design processes of schools in education?

In recognition of the diversity of school systems, we included schools in both primary and secondary sectors (Kindergarten through Grade 12), encompassing all system governance types (public, private, hybrid, religious). In order to preserve coherency and translatability of findings across contexts, we excluded preschool learning environments, as well as learning centres established outside of mainstream schooling, such as Forest Schools. We considered all research reporting on new build schools and which used descriptors of innovation/innovative, modern, flexible, or twenty-first century learning environments.

Our database searches were conducted in the full suite of ProQuest and Scopus databases, with a final search date of 8 January 2020. ProQuest permits upfront exclusion based on pre-assigned categories and we therefore excluded research from higher education contexts in the ProQuest platform prior to export. We imported an initial set of 8,096 articles into the Rayyan systematic review platform (Ouzzani, Hammady, and Fedorowicz Citation2016) for review by two analysts (Deppeler, Aikens and research assistant, White). Articles were excluded in a step-wise process, as documented in . We completed a formal inter-analyst reliability assessment with a subset of 300 articles with inter-analyst agreement on all but one of these articles (299/300; or agreement >99.6%). We therefore had high confidence in decisions of articles assigned to the final set.

Prior to quality appraisal of the articles for inclusion, we searched the reference lists of all articles for relevant literature, which contributed three additional papers to our final set. Finally, we searched for all citing literature within Google Scholar, which yielded an additional five papers.

All relevant articles were assessed for quality using a systematic quality appraisal tool for qualitative research (Lockwood, Munn, and Porritt Citation2015). The quality appraisal tool includes a list of ten criteria related to research framework objectives, methods, analysis and interpretation, ethics, and conclusions. Rather than determining a specific cut-off threshold in terms of the number of criteria obtained, this appraisal tool supports overall assessment of the quality of the article. We excluded a single article at this stage, due to mis-alignment between research objectives and findings. A final total of 29 articles were included in this analysis.

The Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) framework was used as an analytical tool to code the content of the empirical findings, to identify recurring themes, and common and divergent points of interest across the papers. We used a hybrid deductive-inductive approachFootnote 1 (Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006) to compare and contrast what educational needs and challenges the framework's four dimensions (anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness) helped to articulate. We identified the elements that were considered important in aligning the design of the school with the education system and its users.

Summary of literature included in the review

Of the 29 articles that satisfied the inclusion criteria for this review, three countries, Australia (9 articles), the United Kingdom (8 articles), and New Zealand (8 articles) are represented as contexts of study in greater than 80% of these.Footnote 2 The Netherlands is represented by two articles while the remaining countries are represented by a single article each: Canada, Iceland, Indonesia, Portugal, and the United States. A full list of articles, titles, and countries of origin is available in the appendix (S1).

The articles incorporated a range of educational stakeholder perspectives, from architects and designers of school buildings (Daniels et al. Citation2017; Tse et al. Citation2015), to builders (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019), to school leaders (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Wright and Adam Citation2015), teachers and other school staff (Deed et al. Citation2019; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015), and students (Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan Citation2018). Throughout the following text, we use the term ‘school leaders’ to refer to those in formal school leadership roles, i.e. school principals and headteachers.

Elements of responsible innovation in the design, build and use of schools

In the context of responsible innovation in the design, build, and use of new schools we identified a number of elements that were organised around the dimensions of Anticipation, Inclusion, Reflexivity and Responsiveness of the RI framework (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). summarises the main themes present across each of the dimensions and provides a comprehensive list of studies in which each theme presented.

Table 3. Main themes present across 29 empirical articles, organised by four dimensions of responsible innovation.

In the following sections, we outline key findings within each dimension, emphasising how the existing research evidence on stakeholder's perspectives can contribute to responsible innovation with respect to new build schools. We draw attention to the connections across the dimensions, outline remaining gaps in the research literature, before concluding with recommendations for future applied research. Across all dimensions, there was a dearth of empirical research examining the involvement of students, families, and members of the wider community in decision-making processes.

Anticipation – understanding potential impacts of school design for diverse stakeholders and conditions

The RI dimension of anticipation plays a critical role in designing and building innovative learning environments that are fit for school needs. Here, the research literature can highlight at which junctures in the design, build, and occupancy process, resource investment is crucial for success. This involves identifying common challenges in innovative learning environments, visioning how these might play out in local school contexts, and addressing these challenges before they present as major barriers.

Across our analysis, professional learning was consistently recommended as anticipatory support for teaching staff. Recommendations included a variety of forms of professional learning and included both short-term and on-going engagement (e.g. workshops, discussion groups, experimental and authentic ‘real-world’ experiences). Though less often a focus of empirical research, there was also compelling evidence that specialised professional learning for other key stakeholders- architects and designers, educational planners, and school leaders is necessary. In the following section, we introduce evidence and examples of how different forms of teacher-focused professional supported transition into innovative learning environments. We then discuss the limited, but critical evidence about the role of school leaders in providing anticipatory forms of leadership to support transition to new spaces.

To support effective transition into new school buildings, staff must be provided with professional learning opportunities that are sustained and authentic, providing opportunities to shape school design processes, alongside the reshaping of teaching practices (Campbell Citation2020; Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Deed et al. Citation2019; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; Mackey et al. Citation2017; Mulcahy and Morrison Citation2017; Nelson and Johnson Citation2017; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017; Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan Citation2018). To date, teachers’ professional practices have largely been shaped within walled classrooms, and employed teacher-centric spatial arrangements. Transitioning to more open, flexible learning environments involves building trust and skills to facilitate co-teaching processes and new forms of student behaviour management.

Our analysis indicated that professional learning should involve both discussion and visioning processes that establish design intentions and shared understandings and emotional buy-in to the process, as well as experiential components. Discussions of shared understandings must be ongoing and authentic; acknowledging teacher feedback, concerns, and overall design processes must be informed by professional expertise (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2017).

Effective professional learning also addressed the development of socio-emotional skills that facilitate adaptation to new circumstances. These included communication and conflict mediation, problem solving, and negotiation (Daniels et al. Citation2019; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; Mackey et al. Citation2017; Mulcahy et al. Citation2015). Focus group research by Könings, Bovill, and Woolner (Citation2017), including architects, designers, teachers, and students, highlighted the crucial role of empathy building during the design process, with one group of participants reporting that effective compromise was enabled through ‘getting to know each other, building a relationship, building a connection. Actually, maybe even affection for each other and for each other's experiences and each other's expertise … ’ (p.310).

Professional experiences as an anticipatory learning process required built-in budgetary investments. Several articles reported concrete examples of professional learning experiences, including staff field trips to schools that had successfully transitioned into modern new buildings (Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017) and experimental spaces, such design mock-ups or pilot spaces contained within older school buildings (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019). Daniels et al. (Citation2017) described a case study school in which an experimental mock-up space was constructed in the school gymnasium prior to transition: ‘we mocked up open plan learning spaces and learnt how to use them effectively to improve progress for our students. We were preparing a good two years before we moved. (Headteacher A1 interview)’ (p.776).

Multiple evidence streams indicated that school leaders play critical roles in supporting transition to new school buildings (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Wright and Adam Citation2015). When school leaders were able to follow through the design, build, and transition processes, they effectively served as communication bridges between stakeholder groups, as well as anticipated and mitigated challenges through all aspects of the process (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2017). However, there was no indication of professional learning offered to school leaders, nor what forms of preparation might differentiate leaders who were able to secure successful transitions and those that were not.

Anticipatory professional learning was not limited to school staff; rather, within ‘good practice’ scenarios, it also included planners, designers, and other stakeholders involved in the design and build processes, as well as students and families (Daniels et al. Citation2017; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017). Experimental co-learning, through the development, trial, and feedback processes of model or mock-up innovative learning environments supported the detection and mitigation of mistakes before they were built into new school spaces. This co-learning process built up affective ties and increased emotional investment in project success across stakeholder groups (Daniels et al. Citation2017; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017). Based on this body of literature, there is however, little empirical evidence focused on anticipatory forms of learning for students and their families.

Reflexivity – mechanisms for aligning design intentions and educational aims with social and educational practices

The Reflexivity dimension is linked to questions about the purpose of education and thinking about how school architecture supports that purpose. Reflexivity applied across all levels of education from system level authorities and educational planners to architects and designers and to the school principal, teachers, and students. Research studies connected with reflexivity were primarily concerned with mechanisms for aligning design intentions and institutional educational aims with social and educational practices, in varying contexts.

Researchers emphasised the importance of the involvement of different stakeholders, as their varied experiences bring different expertise and understandings to a design process (Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017). Our analysis suggested that the need for different stakeholder involvement changed throughout the design process, with stakeholders having different roles in different phases of the process (Daniels et al. Citation2017; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017).

At the level of planning and design educational planners, designers and architects need to first assess and reflect on the alignment between the design of the new school learning environments and the educational aims. Several articles indicated that architects should critically assess and reflect on both what learners are benefiting from in the various spaces in the school and what they are learning (Kong, Yaacob, and Ariffin Citation2015; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017).

At the level of the school, reflection and reflective practice have long been a feature of quality teaching and considered essential for improving practice (Loughran Citation2010; Schön Citation1987). School leaders noted that their experiences of innovative spaces prompted reflexivity and created learning opportunities for changing practices which in turn prompted the changing of spaces (Mulcahy Citation2016; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015). These findings are further extended by the work of Daniels and his colleagues on the relationship of the physical environments to the experiences of stakeholders in new schools the UK (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Tse et al. Citation2015). Daniels and colleagues make the case that school design should be analysed as a social practice that is driven by multiple motives and that when the motives of professional groups differ at particular stages, this can cause tensions (Daniels et al. Citation2019; Tse et al. Citation2015).

I joined the project after we had won the bid, and to me the whole process of developing the design with the school after that seemed wrong. I expected open, informed and dynamic discussions, held within openly stated constraints of affordability. Instead we got only very limited contact with the school, carefully choreographed by the main contractor so that we didn't say a word out of place. The school probably felt they should have had a lot more say in the development of the design than they ended up having. ([Delivery architect] Tse et al. Citation2015, 75)

In summary reflexive issues that arose across studies made it clear that aligning the visions and social practices of schools is a necessary, albeit challenging task. This process is likely to strengthen reflexivity and empower participants to adapt and further innovate over time in response to the specific needs of their context. While students and parent voices were largely absent in the reviewed research it would appear critical that their reflections would bring unique contributions to the design processes.

Inclusion – incorporating participatory processes in the design, build and occupation of schools

Reflexivity and inclusion are highly interconnected concepts, particularly in the context of educational systems where inclusive access to schooling has been a persistent concern. There is increasing evidence that incorporating diverse perspectives into decision-making processes both supports innovation and avoids mistakes (Page Citation2007). However, when diversity is enacted through an accommodation model, where diverse components or stakeholders are introduced without intention toward system change, diversity becomes little more than a celebration of difference. Bringing diverse viewpoints, with associated histories of exclusion related to ability, race, gender, class, sexuality, into collaborative contexts requires recognition of differential powers and privileges, both individually and institutionally wielded (Anyon Citation1980; Sensoy and DiAngelo Citation2017).

Across the literature included in this analysis, aspects of inclusion were mainly addressed through analysis of participatory design processes and of student autonomy during occupancy of new school spaces. Overall, this body of literature provides evidence that participatory design processes encourage affective investments in project outcomes, which are critical to the design of successful school innovative learning environments (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017). For example, van Merriënboer et al. (Citation2017) described a three-phase participatory design process that foregrounded pedagogical considerations and encouraged equal participation of educational and architectural/construction stakeholders. They argued that participatory design should be synergistic, combining perspectives and knowledge of different groups throughout the process. In this model, educational stakeholders took the lead through the initial phases of specifying underlying pedagogical models and spatial arrangement, with architects and builders leading the final participatory design phase.

Through their focus on the social experiences of both design and occupancy processes, the work of Daniels and colleagues provides strong empirical evidence of the processes and actors implicated in the design and occupancy of new school buildings (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Tse et al. Citation2015). This body of work supports the inclusion of teachers at key decision points in the design process (Daniels et al. Citation2017). Communication across stakeholder groups is especially critical at key juncture points, when new stakeholders are introduced, and understandings of design processes and principles may be re-configured. For example, in the case of the Building Schools for the Future programme in the UK, the initial architectural firm that created school design was not successful during the construction build process. Instead, a company that had not been involved in design processes won the bid, which eventually resulted in frustrations in consulting redundancies, communication breakdowns, and cost-cutting measures that rendered the final buildings not fit for use according to school staff (Daniels et al. Citation2017).

It is also critical to note significant gaps in empirical evidence for participatory design. While several papers noted the affordances of including students in design processes (Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017; Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan Citation2018; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017), we found only one empirical research paper examining how students were effectively engaged in a school design process (Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan Citation2018). Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan (Citation2018) documented the redesign process of a ‘makerspace’ where students were included in creative prototyping processes in designing the new space.

Similarly, we note an absence of research focused on inclusion of community perspectives in school design. There has been increasing recognition of schools as multi-use spaces, with the ability to support community needs (Cleveland Citation2016; McShane, Watkins, and Meredyth Citation2012). Inclusion of community members as key stakeholders in the design process helps ensure that schools can more effectively serve the needs of students, families, and diverse surrounding communities.

Across the majority of reviewed papers that examined student perspectives in the transition, or occupancy stages of innovative learning environments, students indicated that they preferred new school spaces to traditional school plans (Daniels et al. Citation2019; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017). Students reported innovative learning environments as fostering a greater sense of community and belonging, particularly through the inclusion of informal social space. However, this sense of belonging was mediated by the underpinning values of the school. In cases where schools actively fostered community values, students experienced school openness as inviting social space (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2019; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017). In contrast, in schools that focused on behaviour management, surveillance, and vandalism prevention, students experienced open spaces as sites of surveillance and avoided these spaces (Daniels et al. Citation2019; Wheeler and Malekzadeh Citation2015).

Across diverse contexts, researchers reported descriptions of innovative learning environments as supporting increased student autonomy and agency (Byers et al. Citation2018; Charteris and Smardon Citation2018a; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan Citation2018; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017). Student agency and ability to enact their personal learning preferences within a given space is an important element of inclusion in educational innovation. Flexibility and openness of work spaces permitted students to choose where and how to work according to their learning needs: they could choose to escape peer distractions by moving to quieter spaces or, conversely seek out peers for help with challenging work. The following illustrative quote is taken from Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton (Citation2015, 588), in the context of a Victorian public school, in Australia:

I actually find it a lot easier to work, because the environment changes your emotion. It sounds kind of cheesy, but it changes the way that you look at the work … [it is] easier to concentrate on the work, but it is also your decision [as a student] … I need to get this work done, I need to move away from the distractions.

Team teaching provided students with access to multiple teachers in their cohort, and there was some evidence that this supported increased personalised access to teacher mentoring (Mackey et al. Citation2017; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015). For example, one student described how the flexibility of the learning space permitted one-on-one learning akin to tutoring (Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015). These observations of student access to teacher expertise were echoed by teachers in a New Zealand study (Mackey et al. Citation2017).

Similar to (some) student perspectives, teachers experienced increased feelings of surveillance in some open-plan schools, particularly as they adjusted to new forms of teaching (Mulcahy Citation2016; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015). Open plan learning requires a shift in management of student behaviour, from enacting control through walled classrooms to creating supporting structure and routines through other means (Mackey et al. Citation2017; Mulcahy Citation2016; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015). Some articles reported a period of limited period of tension for teachers, followed by adaptation and adjustment to the new space (Deed et al. Citation2019; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019), while others reported a larger scale failure to adapt across the school (Daniels et al. Citation2019; Deed and Lesko Citation2015).

The literature included in this analysis addressed inclusion mainly in terms of participatory design and transition processes (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Könings, Bovill, and Woolner Citation2017) and student autonomy within new build schools (Mulcahy Citation2016; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015; Stornaiuolo, Nichols, and Vasudevan Citation2018). Other aspects of inclusion, for example, inclusion for diverse abilities and disabilities, were largely unaddressed. The issues of power and privilege related to various exclusions, both historic and present, were also absent from this literature.

Responsiveness – adjusting practice and adapting flexible designs for change

Our review highlighted that responsiveness was primarily concerned with adapting practices to align with flexible and open spaces in new schools (Deed and Lesko Citation2015; Deed et al. Citation2019). In cases considered to be successful transitions to new buildings, adaptation was often driven by testing and experimenting with various teaching and learning arrangements that included critical reflection and then action (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; LeBlanc et al. Citation2015). Several articles reported that these transitions disrupted traditional ways of working and created some tension for teachers (Campbell Citation2020; Deed and Lesko Citation2015; Deed et al. Citation2019; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015).

The importance of school leadership in supporting change within the school environment was emphasised across multiple studies in our review (Deed et al. Citation2019; Fletcher, Mackey, and Fickel Citation2017; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Wright and Adam Citation2015). Rather than innovative learning environments determining school practices, our analyses indicated that ‘savvy’ school leaders, principals and head teachers recognised that new learning spaces represented invitations or provocations to do things differently (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015). One principal of a secondary school in Australia described using space as a ‘crowbar’ to transform school practices (Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015). Leadership requires both vision and coaching skills, as articulated by one architect in the case of a school struggling to adapt to their newly-built school: ‘you can have a visionary Head but you’ve got to take your staff along with you as well, there was no prior preparation or involvement for staff and students at the school’ (Daniels et al. Citation2017, 779).

Indeed, opportunities for teachers to experiment, adapt spaces and change practices were enabled by the organisational conditions shaped by leaders in schools (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015). Flexibility fostered responsive cultures and teacher and learner autonomy. These conditions support the alignment of the various elements of the learning environment and enabled users to drive change (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Charteris and Smardon Citation2018b; Deed et al. Citation2019; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015).

Structure and constrained flexibility also play a role in supporting transitions to new school spaces. For example, in their comparative case study analysis of four schools in Australia and New Zealand, French, Imms, and Mahat (Citation2019) described how physical features of the school can serve as ‘enabling constraints’, a term coined by a school principal in their study. Enabling constraints refers to ‘design and organisational features intended to constrain one behavioural choice while encouraging another’ (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019, 9) and thus support sustainable behaviour change. Absence of teacher desks and extension of the school timetable were examples of enabling structural constraints (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019). In line with other case studies, however, the authors noted the importance of fostering a mindset of risk-taking, and a culture of trust, in order for these structural nudges to function effectively.

Collaborative teaching practices figured prominently within new school spaces (Byers et al. Citation2018; Charteris and Smardon Citation2018b; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; Mulcahy and Morrison Citation2017; Sigurðardóttir and Hjartson Citation2016; Wright and Adam Citation2015), though these practices were not universally adopted (Campbell Citation2020; Charteris, Smardon, and Nelson Citation2017; Daniels et al. Citation2019; Deed and Lesko Citation2015; Mulcahy and Morrison Citation2017; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015). In a 10-year post-transition evaluation, Sigurðardóttir and Hjartson (Citation2016) found that team teaching practices were sustained amongst primary teachers but not secondary teachers, who reverted to more traditional single-subject teaching. Multiple studies reported the development of a culture of trust within the school was crucial for effective team teaching (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Saltmarsh et al. Citation2015; Wright and Adam Citation2015) and that these collaborative relationships must be developed over time (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019). Nelson and Johnson (Citation2017) reported on student teachers’ experiences in innovative learning spaces and emphasised that teacher education presents an opportunity to prepare new teachers for these conditions (Nelson and Johnson Citation2017).

Student collaboration within new build school environments was a key research finding within this body of research (Byers et al. Citation2018; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017). Collaborative learning was both a structured part of the school design and routines (Byers et al. Citation2018; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017) and an ad-hoc process in which students accessed peer support as the need arose. In their investigation of teaching and learning in innovation learning environments, Byers et al. (Citation2018) described how spaces ‘specifically designed for dynamic and fluid occupation’ (p.163) provided more opportunities for collaborative student learning, while more rigidly structured space appeared to encourage more teacher-centric and individual learning approaches.

Our analysis indicated that barriers limiting user responsiveness were a consistent source of misalignment in innovative learning environments. These barriers include both material limitations such as inflexible designs, lack of social space and absence of quiet/withdrawal space, as well as socio-political limitations such as communication barriers and contractual obligations that prevented users from remedying design barriers (Daniels et al. Citation2017, Citation2019; Wheeler and Malekzadeh Citation2015; Veloso and Marques Citation2017). Using a participatory approach to post-occupancy evaluation, Wheeler and Malekzadeh (Citation2015) documented a litany of design challenges within three case study schools, including inadequate social space and poor acoustics, ventilation and temperature control. Compounding the physical challenges were overly bureaucratic response procedures: ‘school management cited prolonged administration processes to achieve simple maintenance tasks, along with excessive penalty costs imposed on them’ (Wheeler and Malekzadeh Citation2015, 452).

Synthesis of strategic responses to RI elements for consideration in new school design

provides a summary of strategic responses to the identified RI elements for consideration in new school design, synthesising across findings for all four dimensions of responsible innovation. These strategic responses support the alignment of diverse perspectives and needs across the diverse stakeholders implicated in school design and occupancy. Many of these RI strategic responses are supported by well-established education research literature, for example, the critical importance of leadership for effective schools, continuous professional learning, or the challenges of inclusion in educational processes. While the strategic responses identified here are not meant to be prescriptive, they provide an evidence informed platform for further research and policy development.

Table 4. Strategic responses to the responsible innovation elements arising from the synthesis of research on school design.

Discussion

Despite widespread agreement that the innovative learning environments can support better learning outcomes and increased well-being for staff and students, newly designed schools do not always accomplish these desired outcomes. A key reason for this was due to the misalignment among the intentions of the school design and the needs, values and practices of users in diverse contexts. If schools were not ‘fit for purpose’, retrofits, and adaptations could involve considerable financial and social resources that may or may not achieve the intended aims of innovation (Daniels et al. Citation2019; Veloso and Marques Citation2017; Wheeler and Malekzadeh Citation2015). Despite challenges, recent research also confirmed many overall benefits of ‘well-designed’ schools that were ‘well used’ and resulted in benefits for: students including, increased student autonomy, self-regulation, flexible and collaborative learning (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2019; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019); for teachers, including increased agency, creative and high-trust collaborative teaching environments (French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Wright and Adam Citation2015); and for all school community members, an increased sense of belonging (Cardellino and Woolner Citation2019; Daniels et al. Citation2019; French, Imms, and Mahat Citation2019; Mulcahy, Cleveland, and Aberton Citation2015; van Merriënboer et al. Citation2017; Wright and Adam Citation2015).

This paper has provided a synthesis of strategic elements in a RI framework () that were highlighted by our review of recent research on innovation of school learning environments. We have identified the importance of building understanding among stakeholders regarding design intentions and the critical roles of participatory design and professional learning as both anticipatory and ongoing elements in the RI framework. These two elements align closely with a long history of education research literatures, participatory research approaches, and institutional change theory, which have placed an emphasis on the importance of context and local knowledge to inform on-going and future development and the shaping of innovation (e.g. Fullan Citation2016; Manzini and Rizzo Citation2011; Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner Citation2014).

Our analysis indicated that investments in participatory design processes can support successful transition and occupancy of innovative environments in schools. When co-learning takes place across stakeholder groups such as designers, builders, and educators, it builds social and emotional capital amongst participants. This encourages relations of care and investment from all in making a successful transition.

Participatory processes do not necessarily require that all stakeholders participate equally at all stages and are not intended to invalidate the expertise of architects and designers. Rather, initial design processes can make transparent the values that underpin the design and that are critical for broad participation. Consistent oversight of the design and build process by a designated school leader can support new school builds that are fit for purpose.

Teacher professional learning is important across all stages of transition to new build schools. Our analysis indicates that professional learning provides an opportunity to develop clarity around the purpose and use of the particular design and its underlying values. Absent this, teachers struggle to understand the intent of the design and may be more likely to revert to traditional teaching methods. Relatedly, experimentation with prototypes or observation in pilot schools may smooth transition processes as teachers are provided with the opportunity to re-envision their teaching practices in new spaces. Professional learning programmes must be adequately resourced and provide sufficient time for teachers to engage conceptually and practically, rather than approached as an add-on to an already overcrowded teaching schedule (Webster-Wright Citation2009). Support for effective professional development must be a continuous learning process, providing individual and collaborative learning opportunities within communities of practice (Webster-Wright Citation2009; Lave and Wenger Citation1991).

While the teacher continues to be the primary focus for adapting practices and improving student learning and agency in schools, our review highlighted the critical role of school leadership. This finding is not surprising in light of the growing research regarding effective school leadership. For over four decades, educational research has demonstrated that leaders are pivotal to improving the learning environment and enabling teachers’ efforts, which in turn impacts student learning and the effectiveness of the school (Hitt and Tucker Citation2016). Many of the leadership dimensions identified by Hitt and Tucker (Citation2016) in a synthesis of empirical research were highlighted in our review as particularly important for creating effective learning environments:

-

Establishing school wide commitment to the identified practices,

-

Building professional capacity and communities of practice,

-

Promoting the use of student data as a mechanism for improving teaching and learning and well-being,

-

Creating a culture that includes collaborative decision-making and the on-going development of positive relationships with members of the school community.

Leaders who are committed to creating effective and equitable school environments must continually refine and improve practices, which necessarily includes building professional capacity and improving their own effectiveness (Hooper and Bernhardt Citation2016). What is clear from research is that the effectiveness of innovative learning environments, regardless of the specific context or challenges, require effective leaders with the autonomy to flexibly adapt their school environment sustainably.

A research agenda for responsible innovation in the design and use of new-build schools

This paper has drawn on peer-review empirical literature evaluating stakeholders’ experiences in the design, build, and use of innovative learning environments/new build schools. A proliferation of research in the last five years has provided evidence to support the critical role of participatory design, professional learning, and effective school leadership. However, there remain significant gaps in our understanding of how to support responsible innovation within the school building sector. Here, we propose an agenda for future research focused on (1) cross-disciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary research, and underpinned by (2) collaborative multi-sectoral engagement.

Cross-disciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary research

Internationally, governments are investing billions of dollars in new-build schools, all while facing rapidly-changing future conditions. It is critical that new school investments are future-resilient or able to adapt to uncertainty and variance. Here, the anticipatory element of responsible innovation is especially important, as is research that crosses traditional disciplinary boundaries. We argue that educational researchers need to work alongside sustainability scientists, futures analysts, economists, and others to create research programmes that inform the design of future-resilient schools.

Both forecasting and foresight (the use of quantitative and qualitative data, respectively), need to play prominent roles in designing new school buildings. In the case of forecasting, this involves using recent data on climate predictions, and population growth patterns including rural-urban, inter-state and international migration. Foresight requires synthesising expert judgment across a range of educational, architectural, and scientific disciplines, as well as using deliberative democracy, community asset-mapping, and other participatory methods to elicit ideas and concerns from school community and broader community members.

Future-planning must include design considerations that are flexible enough to adapt to planned, potential, and unforeseen circumstances. These three categories of circumstance exist as points along a spectrum of co-varying predictability and uncertainty. To elaborate, we provide illustrations of each category. An example of planned change includes designing schools in urban/suburban growth corridors that are flexible enough to accommodate growth in student enrolments, in both the near and longer-term future. As an example of failure to adequately plan for growth, we offer the case of Victoria, Australia, where some schools built in growth corridors were faced with enrolment numbers well in excess of their intended capacity. The urgency of the need to accommodate the increased numbers of students resulted in a proliferation of portable classrooms added to the school grounds. In one such case the numbers of added portables exceeded the number of built classrooms – undermining the design intentions of the newly built school (Deppeler and Corrigan Citation2019).

As an example of future planning for potential circumstances, we raise the question of the role of school buildings in adapting to extreme wildfire seasons, such as those recently experienced in Australia, California (US), and Greece. We might ask, what are some of the plausible scenarios for wildfires within the next 10–20 years? How will we deal with school-aged populations, and their families, who may be temporarily displaced but still have a need and right to appropriate education? In anticipation of these conditions, flexibility must be embedded in the design of schools, allowing users easily adapt and reshape physical spaces for uncertain climactic conditions as well as accommodation of temporarily displaced learning communities.

Finally, as the year 2020 has demonstrated, school buildings must also be able to accommodate unforeseen circumstances. The conditions under CoVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019), have forced education policymakers and school leaders to grapple with how their school buildings might be adapted to increase social distancing for teachers and vulnerable students. Evidence on the transmissibility of CoVID-19 in schools is preliminary, and while modelling approaches yield some indication of potential harms (e.g. Viner et al. Citation2020), the relative balance of managing reduced transmission and supporting the needs of diverse student populations is precarious.

Combining the anticipatory dimension of RI with reflexivity, what values do we wish to underpin our decisions, particularly when precedent is absent? The CoVID-19 crisis has highlighted that school buildings are critical sites of social relationship and wellbeing for students (Lee Citation2020; Van Lancker and Parolin Citation2020). Some countries are currently implementing socially-distant school returns which prioritise students on the basis of age, marginalisation (e.g. poverty, food security), and parents’ employment (i.e. as essential workers) (Melnick and Darling-Hammond Citation2020). Evidence supporting which school building configurations might best support these adaptations is currently anecdotal. Thinking beyond the immediate crisis, the International Commission on the Futures of Education released a report in June 2020 which called on ‘all educational stakeholders to protect and transform the school as a separate space–time … where there is as much growth and expansion of social understanding’ (UNESCO Citation2020).

Collaborative multi-sectoral research

This leads into our second, and highly related research recommendation: a focus on collaborative, multi-sectoral research. This is critical in both the design process, as we alluded to the previous section, as well as post-occupancy evaluation. We wish to emphasise here that decisions about new-build schools must be evidence-informed and involve authentic, multi-sectoral engagement. We note the current dearth of empirical evidence supporting how and when to include students, families, and diverse communities in the design of new schools and propose that this be a major focus of future research.

As governments increase investments in innovative learning environments, there needs to be ongoing evaluation of how these school spaces are experienced by system stakeholders, both immediately following the transition period, as well as an additional longitudinal follow-up. While this exercise is important for remedying challenges as they arise, it is critical that this evaluation is conducted through systematic and comparative methods, and in conversation with international research findings. Evaluation of social and educational outcomes of individual schools and school designs is critical for determining the effectiveness and potential future educational and cost benefits and challenges and for informing future development and innovation in design. With this applied research focus, we can develop a robust body of evidence supporting contextualised good practice in the design and use of innovative learning spaces.

Moving forward in innovative school design

The application of Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten’s (Citation2013) RI dimensions provided a conceptual frame to review recent research in school design. As highlighted by our analysis and the empirical research on school design, the approach by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013), offered us an opportunity to think productively about the design and use of new schools. Our review has drawn attention to the key challenges that responsible school design faces and pointed to the strategic elements that could be used in the future to address these challenges. We believe that applying the RI concepts of anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness can bring to light potential limitations in school design processes and thus provide opportunities for further development of what is important across diverse groups.

While the RI framework of Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) has supported our analysis and interpretation of empirical findings in school design, our study has several limitations. Our analysis was restricted to new schools and therefore did not include research on schools with combinations of traditional and newly renovated spaces or partially renovated environments. Thus, the synthesis ignores findings regarding the potential impacts on teachers and learners who experience both kinds of environments. We also chose to frame our data collection and research findings around stakeholders’ experiences in the design and use of innovative learning environments, rather than quantitative impacts or outcomes. Byers et al. (Citation2018) recently completed a systematic assessment of the impacts of innovative learning environments on student learning outcomes, finding support that innovative learning environments improve student achievement. The review emphasises the need for further research evidence that goes well beyond evaluation of the physical attributes of school design to evaluate the educational and social relational experiences of teachers, students and other members of the community who use these environments.

The benefits of further developing our understanding of the physical space school through participatory research and evidence informed collaboration are highlighted not only as mechanisms for improving alignment of policy with design and use, but also for on-going transformation of innovation in school design and educational practices. Our findings have implications for policy as they enable the field to consider the preparedness and experiences of planners, architects, school leaders as well as teachers in creating effective school learning environments that are ‘well-designed’ and ‘well used’ and sustainable – adapting to changes over time.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (17.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of research assistant Antoinette White in the first stages of data collection for the systematic review. We would also like to thank Lorenne Wilks, Deborah Corrigan, and Lucas Walsh for their feedback on earlier manuscript drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Joanne Deppeler is a professor in the Faculty of Education at Monash University. As a qualified educational psychologist and teacher, Joanne's work has focused on the examination and development of effective practices of teaching and learning with diverse students, structures and practices in school learning environments.

Kathleen Aikens is a postdoctoral fellow in Education Futures at Monash University. She researches system change in schools and other learning contexts, with a focus in environmental and sustainability education. She is particularly interested in how educational policy and practice can support better planning for a sustainable future.

Notes

1 Fereday and Muir-Cochrane (Citation2006) emphasise that qualitative analysis is an iterative process involving both inductive and deductive stages. After an initial reading of a subset of papers, we determined that the framework proposed by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) would be a generative approach for analysis, and used the framework as a deductive tool to analyse our set of research articles. Within each dimension of our deductive framework, we developed themes inductively through repeated discussion and comparison across lead analysts.

2 A number of authors in these three countries had published several articles included in this review which were clearly part of an overarching research project. This contributed to the over-representation of these countries in the review and also evidences governmental investment in innovative learning environments research through national-level grants.

References

- Anyon, J. 1980. “Social Class and the Hidden Curriculum of Work.” Journal of Education 162 (1): 67–92.

- Australian National Audit Office . 2010. Building the Education Revolution – Primary Schools for the 21st Century . Canberra : Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Benade, L. 2019. “Flexible Learning Spaces: Inclusive by Design?” New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 54 (1): 53–68. doi:10.1007/s40841-019-00127-2.

- Benade, L. , and M. Jackson . 2017. “Intro to ACCESS Special Issue: Modern Learning Environments.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (8): 744–748. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1317986.

- Benade, L. , and M. Jackson , eds. 2018. Transforming Education Design & Governance in Global Contexts . Singapore : Springer.

- Blackmore, J. , D. Bateman , J. Loughlin , J. O’Mara , and G. Aranda . 2011. Research into the Connection Between Built Learning Spaces and Student Outcomes . Melbourne : Education Policy and Research Division, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

- Byers, T. , M. Mahat , K. Liu , A. Knock , and W. Imms . 2018. Systematic Review of the Effects of Learning Environments on Student Learning Outcomes . Melbourne : University of Melbourne, LEaRN. https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/bitstream/handle/11343/216293/iletc_Technical%20Report%204_2018.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y .

- Campbell, L. 2020. “Teaching in an Inspiring Learning Space: An Investigation of the Extent to Which One School’s Innovative Learning Environment Has Impacted on Teachers’ Pedagogy and Practice.” Research Papers in Education 35 (2): 185–204. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1568526.

- Cardellino, P. , and P. Woolner . 2019. “Designing for Transformation – A Case Study of Open Learning Spaces and Educational Change.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society , 1–20. doi:10.1080/14681366.2019.1649297.

- Charteris, J. , and D. Smardon . 2018a. “A Typology of Agency in New Generation Learning Environments: Emerging Relational, Ecological and New Material Considerations.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 26 (1): 51–68.

- Charteris, J. , and D. Smardon . 2018b. “‘Professional Learning on Steroids’: Implications for Teacher Learning Through Spatialised Practice in New Generation Learning Environments.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 43 (12): 12–29.

- Charteris, J. , D. Smardon , and E. Nelson . 2017. “Innovative Learning Environments and New Materialism: A Conjunctural Analysis of Pedagogic Spaces.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (8): 808–821. doi:10.1080/00131857.2017.1298035.

- Cleveland, B. 2016. “A School But Not As We Know It! Towards Schools for Networked Communities.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE), Melbourne, November 27–December 1.

- Daniels, H. , H. M. Tse , A. Stables , and S. Cox . 2017. “Design as a Social Practice: The Design of New Build Schools.” Oxford Review of Education 43 (6): 767–787.

- Daniels, H. , H. M. Tse , A. Stables , and S. Cox . 2019. “Design as a Social Practice: The Experience of New Build Schools.” Cambridge Journal of Education 49 (2): 215–233.

- Deed, C. , D. Blake , J. Henriksen , A. Mooney , V. Prain , R. Tytler , T. Zitzlaff , et al. 2019. “Teacher Adaptation to Flexible Learning Environments.” Learning Environments Research , 1–13. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10984-019-09302-0.

- Deed, C. , and T. Lesko . 2015. “‘Unwalling’ the Classroom: Teacher Reaction and Adaptation.” Learning Environments Research 18 (2): 217–231.

- Demers-Payette, O. , P. Lehoux , and G. Daudelin . 2016. “Responsible Research and Innovation: A Productive Model for the Future of Medical Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (3): 188–208. doi:10.1080/23299460.2016.1256659.

- Deppeler, J. , and D. Corrigan . 2019. “Teaching and Learning in Schools Shaped for Innovation.” Symposium paper presented at ECER 2019, Education in an Era of Risk – The Role of Educational Research for the Future, Hamburg, Germany, September 3–6.

- DfES . 2003. Building Schools for the Future: Consultation on a New Approach to Capital Investment . London : DfES.

- Elias, M. J. , J. E. Zins , P. A. Graczyk , and R. P. Weissberg . 2003. “Implementation, Sustainability, and Scaling Up of Social-Emotional and Academic Innovations in Public Schools.” School Psychology Review 32 (3): 303–319.

- Elmore, R. 1996. “Getting to Scale with Good Educational Practice.” Harvard Educational Review 66 (1): 1–27.

- Everatt, J. , J. Fletcher , and L. Fickel . 2019. “School Leaders’ Perceptions on Reading, Writing and Mathematics in Innovative Learning Environments.” Education 3-13 47 (8): 906–919.

- Fereday, J. , and E. Muir-Cochrane . 2006. “Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (1): 80–92.

- Fisher, E. 2020. “Reinventing Responsible Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 1–5.

- Fletcher, J. , J. Mackey , and L. Fickel . 2017. “A New Zealand Case Study: What Is Happening to Lead Changes to Effective Co-teaching in Flexible Learning Spaces?” Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice 32 (1): 70–83.

- French, R. , W. Imms , and M. Mahat . 2019. “Case Studies on the Transition from Traditional Classrooms to Innovative Learning Environments: Emerging Strategies for Success.” Improving Schools , 1–15. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/1365480219894408.

- Fullan, M. 2016. “The Elusive Nature of Whole System Improvement in Education.” Journal of Educational Change 17 (4): 539–544.

- Gislason, N. 2010. “Architectural Design and the Learning Environment: A Framework for School Design Research.” Learning Environments Research 13: 127–145.

- Hallinan, J. S. , A. Wipat , R. Kitney , S. Woods , K. Taylor , and A. Goñi-Moreno . 2019. “Future-proofing Synthetic Biology: Educating the Next Generation.” Engineering Biology 3 (2): 25–31.

- Heras, M. , and I. Ruiz-Mallén . 2017. “Responsible Research and Innovation Indicators for Science Education Assessment: How to Measure the Impact?” International Journal of Science Education 39 (18): 2482–2507.

- Hitt, H. D. , and P. D. Tucker . 2016. “Systematic Review of Key Leader Practices Found to Influence Student Achievement: A Unified Framework.” Review of Educational Research 86 (2): 531–569.

- Hooper, M. A. , and V. L. Bernhardt . 2016. Creating Capacity for Learning and Equity in Schools: Instructional, Adaptive, and Transformational Leadership . New York : Routledge.

- Kariippanon, K. E. , D. P. Cliff , S. Lancaster , A. D. Okely , and A. Parrish . 2019. “Flexible Learning Spaces Facilitate Interaction, Collaboration and Behavioural Engagement in Secondary School.” PLoS ONE 14 (10): e0223607. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0223607.

- Kong, S. Y. , N. M. Yaacob , and A. R. M. Ariffin . 2015. “Physical Environment as a 3-D Textbook: Design and Development of a Prototype.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 35 (2): 241–258.

- Könings, K. D. , C. Bovill , and P. Woolner . 2017. “Towards an Interdisciplinary Model of Practice for Participatory Building Design in Education.” European Journal of Education 52 (3): 306–317.

- Lave, J. , and E. Wenger . 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

- LeBlanc, M. , M. T. Léger , M. Lang , and N. Lirette-Pitre . 2015. “When a School Rethinks the Learning Environment: A Single Case Study of a New School Designed Around Experiential Learning.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 174: 3577–3586.

- Lee, J. 2020. “Mental Health Effects of School Closures During COVID-19.” The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4 (6): 421.

- Lockwood, C. , Z. Munn , and K. Porritt . 2015. “Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 179–187.

- Loughran, J. 2010. What Expert Teachers Do: Enhancing Professional Knowledge for Classroom Practice . Crows Nest : Allen & Unwin.

- Lubberink, R. , V. Blok , J. van Ophem , and O. Omta . 2019. “Responsible Innovation by Social Entrepreneurs: An Exploratory Study of Values Integration in Innovations.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (2): 179–210.

- Ludwig, D. , and P. Macnaghten . 2020. “Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Innovation Governance: A Framework for Responsible and Just Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 26–44.

- Mackey, J. , N. O’Reilly , J. Fletcher , and C. Jansen . 2017. “What Do Teachers and Leaders Have to Say About Co-Teaching in Flexible Learning Spaces?” Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice 32 (1): 97.

- Mäkelä, T. , S. Helfenstein , M. Lerkkanen , and A. Poikkeus . 2018. “Student Participation in Learning Environment Improvement: Analysis of a Co-design Project in a Finnish Upper Secondary School.” Learning Environments Research 21: 19–41. doi:10.1007/s10984-017-9242-0.

- Manzini, E. , and F. Rizzo . 2011. “Small Projects/Large Changes: Participatory Design as an Open Participated Process.” CoDesign 7 (3-4): 199–215.

- McShane, I. , J. Watkins , and D. Meredyth . 2012. Schools as Community Hubs: Policy Contexts, Educational Rationales, and Design Challenges . Sydney : Australian Association for Research in Education (NJ1).

- Melnick, H. , and L. Darling-Hammond . (with Leung, M., Yun, C., Schachner, A., Plasencia, S., & Ondrasek, N.). 2020. Reopening Schools in the Context of COVID-19: Health and Safety Guidelines from Other Countries (Policy Brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- Mulcahy, D. 2015. “Re/Assembling Spaces of Learning in Victorian Government Schools: Policy Enactments, Pedagogic Encounters and Micropolitics.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 36 (4): 500–514.

- Mulcahy, D. 2016. “Policy Matters: De/Re/territorialising Spaces of Learning in Victorian Government Schools.” Journal of Education Policy 31 (1): 81–97.

- Mulcahy, D. , B. Cleveland , and H. Aberton . 2015. “Learning Spaces and Pedagogic Change: Envisioned, Enacted and Experienced.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 23 (4): 575–595.

- Mulcahy, D. , and C. Morrison . 2017. “Re/Assembling ‘Innovative’ Learning Environments: Affective Practice and Its Politics.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (8): 749–758.

- Nelson, E. , and L. Johnson . 2017. “Learning to Teach in ILEs on Practicum: Anchoring Practices for Challenging Times.” Waikato Journal of Education 22 (3). doi:10.15663/wje.v22i3.374.

- OECD . 2013. Innovative Learning Environments, Educational Research and Innovation , Paris : OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264203488-en.

- OECD . 2015. Schooling Redesigned: Towards Innovative Learning Systems . Paris : Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264245914-en.

- OECD . 2017. The OECD Handbook for Innovative Learning Environments . Paris : Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264277274-en.

- OECD . 2019. Measuring Innovation in Education . Paris : Educational Research and Innovation, OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/education/measuring-innovation-in-education-2019-9789264311671-en.htm .

- Ouzzani, M. , H. Hammady , and Z. Fedorowicz . 2016. “Rayyan—A Web and Mobile App for Systematic Reviews.” Systematic Reviews 5: 210. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

- Page, S. E. 2007. “Making the Difference: Applying a Logic of Diversity.” Academy of Management Perspectives 21 (4): 6–20.

- Reh, S. , K. Rabenstein , and B. Fritzsche . 2011. “Learning Spaces Without Boundaries? Territories, Power and How Schools Regulate Learning.” Social & Cultural Geography 12 (1): 83–98. doi:10.1080/14649365.2011.542482.

- Ribeiro, B. , L. Bengtsson , P. Benneworth , S. Bührer , E. Castro-Martínez , M. Hansen , K. Jarmai , et al. 2018. “Introducing the Dilemma of Societal Alignment for Inclusive and Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 5 (3): 316–331.

- Richter, J. , A. E. Hale , and L. M. Archambault . 2019. “Responsible Innovation and Education: Integrating Values and Technology in the Classroom.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (1): 98–103.

- Saltmarsh, S. , A. Chapman , M. Campbell , and C. Drew . 2015. “Putting ‘Structure Within the Space’: Spatially Un/Responsive Pedagogic Practices in Open-Plan Learning Environments.” Educational Review 67 (3): 315–327.

- Schabmann, A. , V. Popper , B. M. Schmidt , C. Kühn , U. Pitro , and C. Spiel . 2016. “The Relevance of Innovative School Architecture for School Principals.” School Leadership & Management 36 (2): 184–203. doi:10.1080/13632434.2016.1196175.

- Schleicher, A. 2018. World Class: How to Build a 21st-Century School System . Paris : OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264300002-en.

- Schön, D. A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward A New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions . 1st ed. The Jossey-Bass Higher Education Series. San Francisco, CA : Jossey-Bass.

- Sensoy, O. , and R. DiAngelo . 2017. Is Everyone Really Equal? An Introduction to Key Concepts in Social Justice Education . New York : Teachers College Press.

- Sigurðardóttir, A. , and T. Hjartson . 2016. “The Idea and Reality of an Innovative School: From Inventive Design to Established Practice in a New School Building.” Improving Schools 19 (1): 62–79. doi:10.1177/1365480215612173.

- Stilgoe, J. , R. Owen , and P. Macnaghten . 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42: 1568–1580.

- Stornaiuolo, A. , T. P. Nichols , and V. Vasudevan . 2018. “Building Spaces for Literacy in School: Mapping the Emergence of a Literacy Makerspace.” English Teaching: Practice & Critique 17 (4): 357–370.

- Tse, H. M. , S. Learoyd-Smith , A. Stables , and H. Daniels . 2015. “Continuity and Conflict in School Design: A Case Study from Building Schools for the Future.” Intelligent Buildings International 7 (2-3): 64–82.

- UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) . 2020. Education in a Post-COVID World: Nine Ideas for Public Action . Paris : UNESCO.

- Valkenburg, G. , A. Mamidipudi , P. Pandey , and W. E. Bijker . 2020. “Responsible Innovation as Empowering Ways of Knowing.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 6–25.

- Van Lancker, W. , and Z. Parolin . 2020. “COVID-19, School Closures, and Child Poverty: A Social Crisis in the Making.” The Lancet Public Health 5 (5): e243–e244.