ABSTRACT

Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) scholars have explored how businesses perceive the goals and processes of RRI and have developed tools to enable entrepreneurs to integrate such principles into their practices. While these tools often adopt a formative approach and may include measurable self-assessment indicators, external assessment approaches have so far received little attention. This study addresses this gap by applying the Responsible Innovation in Health (RIH) Tool, which adopts an external assessment approach, to 16 health innovations from Canada and Brazil. Combining publicly available information sources and interviews, our findings show the extent to which the nine attributes of the Tool are fulfilled and shed light on how entrepreneurs materialize these responsibility considerations. Such an external assessment increases transparency and makes more explicit the responsibility trade-offs entrepreneurs face. In view of the RRI tools available, reconciling formative and summative ends in their development could make RRI's expectations towards businesses more actionable.

Introduction

Efforts by the Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) community to reach out to businesses are limited, but rapidly growing (Jarmai, Tharani, and Nwafor Citation2020). RRI scholars have explored how businesses perceive the aims and processes of RRI and how for-profit and social enterprises may integrate its principles into innovation development (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2016; Brand and Blok Citation2019; Long et al. Citation2020). A number of RRI tools have also been developed. While these tools adopt a formative approach (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2016; Stahl Citation2017; Long et al. Citation2020) and may include measurable self-assessment indicators (Flipse Citation2018; Tharani, Jarmai, and Nwafor Citation2020), a ‘crucial issue’ lies with determining whether assessment should be done by the firms themselves or should include external assessment approaches (van de Poel et al. Citation2020). Because the Responsible Innovation in Health (RIH) Tool adopts a summative external assessment approach (Silva et al. Citation2020), the aim of this paper is to contribute to the literature on RRI and businesses by sharing findings from the application of the RIH Tool to 16 health innovations. The latter were developed by organizations from two Canadian provinces (Quebec, Ontario) and the Brazilian state of São Paulo recruited for a broader longitudinal case study.

This paper is comprised of four sections. Below, we provide an overview of the frameworks and tools meant to support the integration of RRI into businesses and introduce the RIH Tool, which relies on nine attributes measured through a four-level scale. Then, we describe the public documents used to apply the RIH Tool and the interviews we conducted with entrepreneurs. Our quantitative findings establish the extent to which the nine attributes are fulfilled and the interviews shed light on how entrepreneurs materialize these responsibility considerations. In view of the RRI tools currently available for businesses, our discussion highlights how an external assessment like the one supported by the RIH Tool increases transparency and can provide entrepreneurs with a concrete set of responsibility trade-offs to consider at an early stage of development. We also argue that reconciling formative and summative ends in the development of RRI tools has the potential to make the field's normative expectations towards businesses more actionable.

RRI frameworks and tools for businesses, entrepreneurs and innovatorsFootnote 1

RRI emphasizes the need to anticipate the unintended consequences of innovation, to set in place inclusive development processes, to be reflexive about the underlying values and norms of innovation, and to secure responsive regulatory pathways. These four processual requirements, articulated in the RRI framework of Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013), are often used to structure reflections and empirical research in RRI (see Box 1). As Long et al. (Citation2020) underscore, the growing interest within the RRI community for the development of business-oriented tools is rooted within the emergence of the field itself. Important groundwork was achieved by European initiatives, including the Karim Network (Hin et al. Citation2014), the PRISMA project (Flipse and Yaghmaei Citation2018; Porcari et al. Citation2019) and the RRI Toolkit. The latter led to an impressive online repository of tools that can support different activities, ranging from raising awareness about RRI to implementing its processual principles.

-

Anticipation: ‘determining what are the desired impacts of innovation, how to prevent or mitigate negative ones and uncover the pathways to achieve this while still remaining aware of uncertainty’;

-

Inclusion: obtaining ‘the commitment and contributions of a diversity of stakeholders, who bring the resources necessary’;

-

Reflexivity: ‘critically thinking about actions and responsibilities, values and motivations, knowledge and perceived realities, and how they have an impact on the innovation process and its desired outcomes’;

-

Responsiveness: making ‘the necessary internal or external adjustments to meet the innovation's desired outcomes’ with stakeholders who can ‘adjust their role along the way.’

Yet, for Jarmai, Tharani, and Nwafor (Citation2020), RRI ‘is currently not tailored towards businesses’ and research on the integration of RRI in R&D-intensive sectors should ‘build on what businesses are already doing.’ After piloting the implementation of RRI in eight enterprises from the United Kingdom, Italy, Switzerland and the Netherlands operating in synthetic biology, nanotechnology, autonomous vehicles and the Internet of Things, van de Poel et al. (Citation2020) came to similar conclusions. Focusing on social entrepreneurs, Lubberink et al. (Citation2019) examined what they call ‘de facto’ responsible innovation practices to explore inductively how responsibility may take shape without ‘clear frameworks or guidelines.’ Rather than ‘constructing yet another framework to specify the normative content’ of RRI, the Res-AGorA project took a similar approach (Lindner et al. Citation2016).

As we further elaborate in our discussion, choosing to adopt or not a normative evaluation standpoint conditions the kinds of tools RRI scholars may envisage and develop (Scriven Citation1997). For instance, a formative self-assessment approach may, on the one hand, prove ‘easier to implement and less sensitive for a company,’ which would thus be more likely to learn from the experience (van de Poel et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, self-assessment ‘may raise doubts to the outside world’ if positive results are frequently communicated, suggesting ‘a form of window-dressing rather than a real commitment to RRI’ (van de Poel et al. Citation2020). The respective merits and flaws of different evaluation approaches have been at the core of the evaluation scholarship for decades (Scriven Citation1997). While a number of RRI tools have been developed and applied (Fisher et al. Citation2015), most tend not to be used primarily in the private sector. To gain a better understanding of the key characteristics of the tools specifically developed to support the integration of RRI into innovators’ and entrepreneurs’ practices in business settings, we compiled in those mentioned in peer-reviewed publications.Footnote 2

Table 1. An overview of the tools developed to support the implementation of RRI in innovators’ and entrepreneurs’ practices.

The ORBIT Self-Assessment Tool was developed for Information and Communication Technology (ICT) developers (Stahl Citation2017). Because ‘the process of reflection in RRI is likely to benefit from a more clearly defined structure,’ this tool provides innovators with a series of questions organized into a 4 × 4 matrix (see ). It can thus trigger ‘ideas for actions that will help put RRI in practice’ (Stahl Citation2017). In the long run, it is hoped that the tool will allow comparisons between ‘projects, users, technologies or sub-disciplines.’ Yet, the rationale is not ‘to identify objective measures or metrics,’ but to stress that ‘an attempt to quantify stages of RRI development’ can fruitfully inform discussions on the practice of RRI (Stahl Citation2017).

To provide CEOs, senior executives and innovation project managers with guidance in their strategic role as implementors of RRI, the Res-AGorA project generated ‘a practice-oriented governance tool’ (Lindner et al. Citation2016). The Responsibility Navigator puts forward 10 principles that cover 3 processual dimensions: (1) ensuring quality of interaction; (2) positioning and orchestration; and (3) developing supportive environments (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2016). The assumption of this Tool is that ‘legitimate and effective governance’ should not only rely on self-regulation, but also on external control and accountability mechanisms (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2016).

Seeking to provide ‘an easy to use and accessible tool’ for small entrepreneurial teams, Long et al. (Citation2020) developed the RMoI tool, which they tested with 12 ‘sustainability orientated start-ups.’ Relying on experiential learning principles, this tool provides innovators with ‘a systematic way to identify and consider socio-ethical risks and opportunities’ (Long et al. Citation2020). Its application involves a workshop where participants: (1) identify socio-ethical issues raised by their innovation; (2) are then prompted to discover additional issues using the visuals of the Product Impact Tool; and (3) after being explicitly introduced to RRI dimensions, rank the top 3 socio-ethical issues and reflect on ways to address them (Long et al. Citation2020).

The aim of KARIM is to help companies ‘to reconsider their business model, develop new products and services, new technologies or even improve their production processes’ (Hin et al. Citation2014). It combines a self-diagnostic tool with a summative analytical grid comprised of 24 criteria. The latter are organized around the three sustainable development pillars, highlighting the social, economic and environmental impacts that may arise along an innovative project. By engaging in a formative process, the innovation team can use responsibility ‘as a lever of creativity’ and ensure that ‘performance and responsibility are combined towards paving a more sustainable and competitive path’ for the organization (Hin et al. Citation2014).

The Responsible Innovation Compass is a self-check ‘learning instrument’ that aims to help small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in innovative sectors to implement RRI (Tharani, Jarmai, and Nwafor Citation2020). Embedded within an online platform, the tool is comprised of 4 modules that cover the entrepreneurial pathway. As participants go through brief surveys with a choice of answers reflecting ‘good practices’ in RRI, the tool establishes scores and compares the participant's results to other results. The logic is to enable entrepreneurs to know how their organization compares to others and identify ways to ‘make their innovation practices more responsible’ (Tharani, Jarmai, and Nwafor Citation2020).

The goal of PRISMA is to help companies implement RRI in ‘their innovation and social responsibility strategies’ (Porcari et al. Citation2019). Targeting top managers, a formative toolbox approach that includes summative indicators is adopted, e.g. a self-assessment questionnaire, a set of 5 criteria to perform an impact analysis, and 10 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). The penultimate component of the toolbox is the creation of a roadmap specific to each organization, which graphically synthetizes the drivers and challenges to adopt RRI practices, risks and barriers that RRI may help address, the organization's RRI actions, and key milestones in its innovation pathway.

Using similar social, economic and technical KPIs, Flipse (Citation2018) developed and tested with a contract research organization an ICT-based tool to help ‘researchers reflect on their practices and explore possibilities for improvement.’ Taking the form of a collective dashboard, the tool brings forward ‘soft’ socio-ethical issues that can be scored and visualized. To this end, previous projects considered successful by the organization are used as benchmarks, which push innovators to become ‘reflective practitioners’ who take RRI ‘as a starting point rather than an add-on’ (Flipse Citation2018).

Overall, efforts by the RRI community to support the implementation of RRI are diversified and substantial (Iatridis Citation2015). Initiatives adopting a formative evaluation approach generally favor self-reflective tools (i.e. fostering learning and improvement within an ongoing process). When measurable indicators are provided, self-assessment is still emphasized: metrics are generated by, and for each organization's own internal purposes. One key problem with such a formative approach is that it cannot generate a solid and openly accessible empirical basis (Scriven Citation1997) allowing RRI scholars to learn about the extent to which entrepreneurs do commit, in practice, to RRI and how they integrate responsibility considerations into their innovations and business models (Jarmai, Tharani, and Nwafor Citation2020). In addition, while self-reflective tools may succeed in prompting new ways of thinking about the socio-ethical issues raised by innovation, they provide little guidance about the concrete ways in which those who design innovations can produce outcomes aligned with RRI's expectations (Brand and Blok Citation2019). The fact that process-dimensions are largely emphasized exacerbates this problem because anticipation, inclusiveness, reflexivity and responsiveness may fail to address product- and organization-level dimensions that directly affect responsibility (von Schomberg Citation2013). Lastly, to our knowledge, only ORBIT, RMol and the ICT-based tool were empirically tested and we found no publications establishing the validity and reliability of the tools listed in .

The responsible innovation in health (RIH) tool

By supporting an evidence-informed external assessment, the RIH Tool (Silva et al. Citation2020) bridges the gaps highlighted above. Firmly anchored in the RRI scholarship, RIH was developed in view of the large contingent of RRI scholars who do research on health innovations (Timmermans Citation2017) with the aim of defining in greater depth responsibility concerns specific to the health sector (Silva et al. Citation2018). The way businesses operate in healthcare differs substantially from other sectors and responsibility issues are distinct and wide-ranging. First, patients are typically the end-users of innovation, but they rarely make the decision to purchase or use healthcare products and services. Second, organizations that develop and commercialize innovations are subject to stringent regulatory frameworks where risks and liability issues are salient. Lastly, these innovations have to align with the mission of health systems which is to provide safe, effective, equitable and sustainable health and social care services to their insured patients. Though responsibility has been institutionalized in this sector since the late 1980s through multiple mechanisms (e.g. professional codes of conduct, market approval for drugs and medical devices), complex, costly and labor-intensive technologies continue to raise major challenges for health systems (Roncarolo et al. Citation2017). Because the health sector strongly values evidence-informed decisions, decision-makers must seek to improve the basis upon which they decide to adopt new technologies while remaining able to address other pressing population health and social care needs (Borowy and Aillon Citation2017).

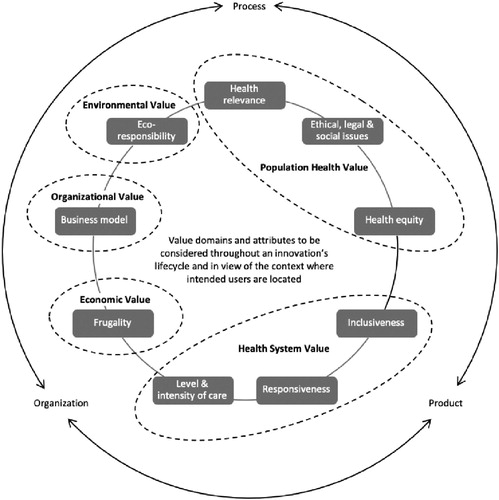

For these reasons, the development of the RIH Tool was informed by an extensive multidisciplinary literature review and a horizon scan of a large set of innovations (n = 105) illustrating various responsibility considerations, which led to the development of the RIH framework (Silva et al. Citation2018). This framework is comprised of nine attributes that capture process-, product- and organization-level dimensions (see ). Its five value domains emphasize the notion that RIH should: (1) increase the ability to meet collective needs while tackling health inequalities (population health); (2) provide an appropriate response to system-level challenges (health system); (3) deliver affordable high-quality products (economic value); (4) rely on business models through which more value is provided not only to users and purchasers, but also to society (organizational value); and (5) reduce as much as possible the environmental impacts of health innovations along their whole lifecycle (environmental value) (Silva et al. Citation2018). Following this normative framework, the definitions of the RIH Tool's attributes and scales were iteratively consolidated through a two-round Delphi study with international experts in RRI, bioethics, biomedical engineering and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) (Silva, Lehoux, and Hagemeister Citation2018).

Figure 1. The value domains and attributes of the RIH framework. Source: Silva et al. (Citation2018).

As further explained in the methods, the RIH Tool entails scoring nine attributes using a four-level scale in light of the scientific literature and publicly available documentation. Thus, in comparison to the tools in , the RIH Tool: (1) supports an external assessment by individuals holding research skills who can access and critically read scientific literatureFootnote 3 ; (2) relies on a limited number of summative indicators to assess the degree of responsibility of a given innovation; (3) generate metrics that are meant to inform multiple innovation stakeholders such as investors, innovators, entrepreneurs, incubators, Technology Transfer Offices, etc. (as opposed to serving a single organization's purposes); and (4) its reliability has been measured through an inter-rater agreement study that showed ‘almost perfect’ agreement for 7 attributes, ‘substantial’ agreement for 2 attributes and ‘almost perfect’ agreement for its overall score (Silva et al. Citation2020). Hence, to shed light on the role external assessments may play in the operationalization of RRI in businesses, we applied the RIH Tool to 16 innovations and supplemented its summative findings with qualitative interviews.

Methods

Case sampling strategy

The current study is nested within a broader longitudinal case study that began in 2017 (Yin Citation2009). Its goal is to generate a better understanding of why and how innovative organizations that possess responsibility features can develop and bring to market responsible health innovations. The broader study focuses on the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario and the Brazilian state of São Paulo for theoretical and practical reasons. First, notwithstanding the largely European focus in the RRI scholarship (Timmermans Citation2017), it is important to look at how RRI may transform entrepreneurial practices in both mature and emerging economies (Voegtlin et al. Citation2019). The need for international research is especially acute in the health sector where innovations that address the broader determinants of health (e.g. education, gender, environmental issues, etc.) can contribute to multiple Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs), which represent key purposes for RRI (Lehoux et al. Citation2018). Such challenges are deeply interconnected across countries and call for international study designs that can generate a more robust and encompassing understanding of why and how RRI can be operationalized in different contexts. Since there is an important publicly financed health system in Brazil and a mix of population health needs that call for products and services that Western countries tend to neglect, the state of São Paulo (the most populous and economically developed state in the country) offers a particularly rich innovation research setting (Mazzucato and Penna Citation2016). Health systems in Quebec and Ontario are also publicly funded and the Canadian drug and medical devices industries are concentrated in these two provinces. Practical reasons included our research team's location (Quebec) and linguistic skills (three members were born and trained in Brazil).

Following a theoretical case sampling strategy where cases are chosen in view of their potential to generate rich and diversified data about the phenomenon of interest (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007), we aimed to recruit 8 innovative organizations in each country. Using the responsibility features of the RIH framework (Silva et al. Citation2018) as selection criteria, we conducted an online search that was iteratively refined (using websites and social media accounts dedicated to health innovations and entrepreneurship with a social mission). Since different users and stakeholders may express different kinds of demands, the innovation types (e.g. assistive devices, diagnostic tools, patient-oriented tools, etc.) served as an internal diversification criterion (Goffin et al. Citation2019). Overall, 6 organizations in Quebec were contacted and 2 refused to participate, 14 organizations were contacted in Ontario, 1 did not meet our criteria and 9 refused to participate, and 8 organizations in Brazil were recruited (none refused). Reasons to decline included lack of time, interest and/or perceived benefit for the organization.

Application of the RIH ToolFootnote 4

The RIH Tool is applied to a given innovation to assess its degree of responsibility. The Tool is comprised of nine attributes that rely on a four-level scale, ranging from A to D, where A implies a high degree of responsibility (5 points), B a moderate degree of responsibility (4 pts), C a low degree of responsibility (2 pts) and D no particular signs of responsibility (1 pt). Obtaining a D score for a given attribute does not mean the innovation is ‘irresponsible’: it rather signals the absence of this RIH feature. All attributes are assessed in light of the available evidence and in view of the geographical context where users are located. The types of information sources that can be used are indicated in the RIH Tool itself (available as a 8-page Supplementary file in Silva et al. [Citation2020]), which provides a simple classification of their quality level:

-

Type 1. Low quality sources (1 pt): technical documentation made available by the organization that produces the innovation;

-

Type 2. Moderate quality sources (2 pts): reports by multilateral organizations, governments, regulatory agencies, certification bodies or independent not-for-profit organizations that monitor human and labor rights, animal welfare and environmental regulation;

-

Type 3. High quality sources (3 pts): peer-reviewed scientific articles and systematic reviews of the literature.

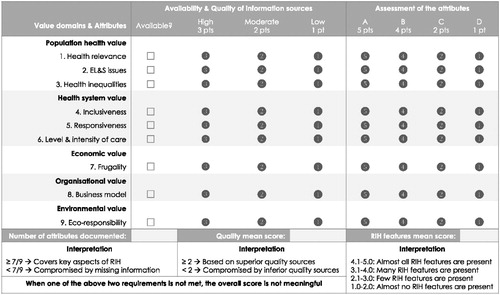

The assessment outcomes are determined after having compiled on a scorecard (see ): (1) the number of attributes for which information was available; (2) the mean score for the quality of the information sources usedFootnote 5 ; and (3) the mean score of all documented attributes. The interpretation of the latter – the overall RIH score – relies on a four-level interval according to which ‘almost all’ (4.1–5.0), ‘many’ (3.1–4.0), ‘few’ (2.1–3.0) or ‘almost no RIH features are present’ (1.0–2.0). Yet, this score is considered meaningful only if two conditions are met: (1) a sufficient number of documented attributes (≥7/9 attributes); and (2) information sources of superior quality (mean score ≤2 pts).

Figure 2. The RIH Tool scorecard.

Note: The RIH Tool itself can be found as a Supplementary file in Silva et al. (Citation2020).

Data sources and analyses

shows the interviews (n = 23) conducted at the outset of our case study for each organization. Interviews with founders, CEOs and members of the management team lasted around 90 minutes and explored the genesis of the organization (why it was created, its mission), its business model, its organizational capacity and the challenges it faces (interview questionnaire available upon request). Depending on informants’ preferences, interviews took place in French, English or Portuguese. With the consent of each participant, interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The qualitative data analysis software Dedoose™ was used to categorize interview transcripts. The coding scheme was initially developed by two co-authors and refined with the input of other team members. In this paper, we rely on interviewees’ descriptions of their products and services, innovation processes and organizational capacity to provide more depth to the quantitative findings, i.e. eliciting ‘why’ and ‘how’ the nine RIH attributes are materialized (Goffin et al. Citation2019).

Table 2. Role of the interviewees (n = 23).

The application of the RIH Tool requires searching for and summarizing publicly available documents containing statements that describe, for each of the nine attributes, which level of the scale is fulfilled. For instance, the Inclusiveness scale asks whether those who developed the innovation:

-

Engaged a diverse and relevant set of stakeholders through a formal method and explained how their input was integrated in the design process;

-

Engaged a diverse and relevant set of stakeholders through a formal method, but did not explain how their input was integrated in the design process;

-

Either engaged a limited set of stakeholders or did not explain the method used;

-

Did not engage stakeholders.

We gathered publicly available documents in early 2019. This included scientific publications, reports by external bodies and documentation made available on each organization's website (e.g. media articles, publications, press releases, etc.). Detailed extracts from these sources were tabulated in an Excel spreadsheet structured around the nine attributes. All attributes were scored independently by two raters and justifications for the scores reported. Discrepancies in ratings were resolved afterwards with a third team member. Quantitative analyses involved performing descriptive statistics to derive mean scores and frequency distributions.

Below, to provide readers with a chain of evidence supporting our empirical observations (Yin Citation2009), quantitative findings are supplemented with participant quotes that were translated from French to English or from Portuguese to English when needed. We use uppercase letters to designate the organization and the region (e.g. K-SP for organization K in São Paulo) and numbers to designate interviewees.

Findings

We first provide an overview of the 16 organizations, the information sources we used to apply the RIH Tool and the quantitative results. Then, by drawing on the interviews, we further explore how entrepreneurs seek to materialize the 9 attributes.

An overview of the sample and quantitative findings

describes the 16 organizations, their legal structure and the various types of innovation they developed. It shows that about half of the organizations has a for-profit structure (n = 9) and the other half a not-for-profit structure (n = 7). Following our internal diversification criterion, 4 innovations are diagnostic and research tools, 4 innovations were designed to support patients and/or informal caregivers, 3 are technical aids, 2 are bottom-up multidimensional interventions and the last 3 innovations include a nutritional supplement, a set of sustainable drug packaging solutions and mobile care units. Up to 10 innovations also include digital components (e.g. online platforms, apps, artificial intelligence-based solutions).

Table 3. The legal structures and innovations of the 16 organizations.

shows the availability and quality of the information sources used to apply the RIH Tool to the whole sample. It shows that 94% of the innovations have a sufficient number of attributes documented (≥7/9), whereas the assessment of 6% of them is compromised by missing information (<7/9). Information related to the Eco-responsibility attribute is often missing (11/16: data not shown), followed by Health inequalities (3/16). For 25% of the innovations, the assessment is based on sources of moderate to high quality (≥2), while it is compromised by sources of low to moderate quality (<2) for 75% of the sample. Following the conservative interpretation rules of the RIH Tool when applied to summative ends, the overall RIH score is considered only meaningful when the above two thresholds are met, which is the case for 25% of the sample, a point we address in the discussion.

Table 4. Results of the availability and quality of the information sources used to apply the RIH Tool to the 16 innovations.

shows the results of the assessment for the whole sample. A large majority of the innovations obtains the highest score (A) for 3 attributes: Responsiveness (86%), Health relevance (81%) and Level and intensity of care (73%). This suggests that the innovations are: (1) providing a solution to a system-level challenge documented as being of high importance in the target region; (2) addressing a health problem falling within the top quarter of all causes of death, injury, disability or risk factors; and (3) providing a solution that is mostly under the care of the patient, an informal caregiver or a health and social care provider operating in a non-clinical environment. Half of the sample obtains the highest score (A) for Health inequalities (54%) and Frugality (50%), which highlights that these innovations: (1) cater to the needs of a vulnerable group that are unmet by current solutions; and (2) were designed with a focus on affordability, core functionalities and ease of use, and optimized performance level in view of the context of use.

Table 5. Results of the assessment and rating steps for the 16 innovations.

The majority of the innovations obtains a C score for Ethical, Legal and Social Issues (ELSIs) (73%) and Inclusiveness (64%). The former implies that mitigation means are available for few of the applicable ELSIs. The latter underscores that those who developed the innovations either engaged a limited set of stakeholders or did not explain the method used. Scores are more evenly distributed across the scale for Eco-responsibility (respectively, 40%, 20%, 40% and 0%) and Business model (38%, 19%, 31% and 13%). These variations may be partly explained by the lack of information about environmental impacts and the mix of organizational structures in our sample. The 5 innovations for which information about Eco-responsibility is available integrated such concerns at either 3 (A), 2 (B) or 1 (C) key stages in their lifecycle (raw material sourcing, manufacturing, distribution, use and disposal). The Business model scale examines whether 3 (A), 2 (B), 1 (C) or none (D) of the following characteristics are met: (1) the organization pursues a social and/or environmental mission, operates on a not-for-profit basis or reinvests the majority of its revenues in its mission; (2) makes the innovation freely usable or exploitable by others; (3) adopts a pricing scheme based on ability to pay or a redistributive logic (e.g. ‘buy one, give one’ model); (4) employs people with particular needs (e.g. low literacy, disabilities); or (5) complies with social responsibility programs.Footnote 6

also shows that the overall RIH score of 5 innovations (31%) falls within the highest interval (Almost all RIH features are present) and 8 of them (50%) within the second highest interval (Many RIH features are present). While the overall RIH score of 3 innovations (19%) is within the third interval (Few RIH features are present), none falls within the lowest (Almost no RIH features are present). This of course reflects the selection criteria of our case study.

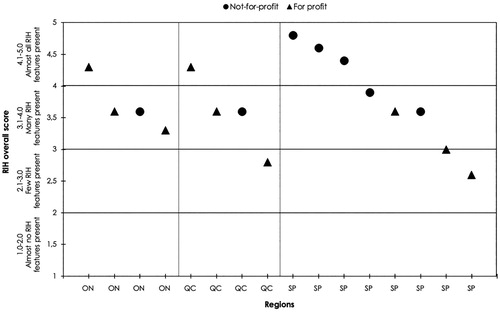

offers a visual illustration of the distribution of all innovations according to their overall RIH score, region and legal structure. It indicates that 2 out of the 5 organizations whose innovation scores between 4.1 and 5.0 operate on a for-profit basis and are located in Ontario and Quebec and the other 3 are not-for-profit entities located in São Paulo. Among the 8 organizations whose innovation scores between 3.1 and 4.0, for-profit and not-for-profit structures are equally distributed and 3 are located in Ontario, 2 in Quebec and 3 in São Paulo. The 3 organizations whose innovation scores between 2.1 and 3.0 are for-profit entities in Quebec and São Paulo. Data are further aggregated in , which compares the mean overall RIH scores across regions and legal structures. Whereas variation across regions is limited, ranging from a mean of 3.5 in Quebec to a mean of 3.8 in São Paulo, the variations across legal structures is more important: innovations produced by for-profit organizations tend to obtain a lower score (3.5 on average) than those produced by not-for-profit organizations (4.1).

Figure 3. Distribution of the 16 innovations according to their overall RIH score, region and legal structure.

Table 6. Comparison of the overall RIH mean score across regions and legal structures.

Overall, in light of the documentation available at the time of our assessment, our quantitative findings suggest that the cohort is well aligned with the goal of RIH, which is to support the development of innovations that can foster equity and sustainability in health systems. Indeed, five attributes are fulfilled to a great extent: Responsiveness, Health relevance, Frugality, Level and intensity of care and Health inequalities. However, the mean scores for Inclusiveness and ELSIs are particularly low. We explore below these findings in greater depth through the interviews.

Exploring why and how the 9 attributes are more or less frequently fulfilled

Within the RIH framework, Responsiveness (mean score: 4.5) is focused on the needs and challenges of health systems and refers to the ability to provide dynamic solutions to existing and emerging system-level issues. For instance, in collaboration with the Brazilian public health system, the mobile care clinics of P-SP are dedicated to bridge service delivery gaps in underserved areas by providing ‘efficient’ and ‘humanized’ care (P-SP, 1). F-ON, whose founder had training and experience with health problems affecting older adults, created printed and digital books adapted to individuals who live with dementia. N-SP developed its thyroid cancer diagnostic tool after medical specialists explained their problem: for 30% of the nodules, they ‘cannot tell whether it's benign or malignant’ (N-SP, 1). A-ON's ‘motivation was a problem encountered in practice’ too (A-ON, 1). Its tablet-based hearing test is a less costly solution that can be easily administered, for instance, to offshore drilling rigs workers whose potential hearing losses have to be closely monitored. Hence, the capacity to materialize this attribute is linked to innovators’ background and experience, but also to their ability to respond to health and social care stakeholders’ needs.

Health relevance (4.3) refers to the importance of the health needs addressed by the innovation in view of the overall burden of disease in the region where its users are located. As one may expect, this attribute captures an important entrepreneurial motivation. While interviewees use metrics that differ from the RIH Tool scale, they nonetheless underscore the needs they strive to meet. Realizing that up to ‘13,000 children’ in Brazil are diagnosed with cancer every year, J-SP created illustrated books that explain in simple terms the disease and its treatment (J-SP, 1). M-SP created its eye fundus imaging device stressing that diabetes, which is associated with retinopathy, ‘increased 60% in Brazil over the last 10 years’ and ‘almost 10% of the population’ is affected (M-SP, 1). Interestingly, the motivations behind Q-SP's lighting solutions for communities deprived of access to electricity combine health relevance and eco-responsibility concerns: families live ‘in the dark or with a diesel lamp, which has an impact on health’ and ‘we replace it with clean, solar energy’ (Q-SP, 1). Conversely, B-QC, which provides drug retailers and pharmacies with eco-responsible drug packaging solutions, fosters ‘a series of simple actions’ for its employees to contribute to sustainable development including ‘cycling to work’ (B-QC, 1).

Frugality (4.3) entails delivering greater value to more people by using fewer resources such as capital, materials, energy and labor time. This is achieved by substantially reducing an innovation's costs of production, use and maintenance, providing the core functionalities its users need and optimizing its fit with the context of use. Since D-QC's research tool entails producing antibodies by using chicken egg yolk rather than extracting animal blood serum, it is a less invasive and costly option (D-QC, 1). K-SP developed highly affordable hearing aids with batteries rechargeable through solar energy and Q-SP trains community members to install and take charge of the maintenance of cleaner lighting solutions. These examples indicate that Frugality and Eco-responsibility attributes can be synergistic.

Level and intensity of care (4.2) refers to the subsidiarity principle according to which the most decentralized health system unit should be mobilized to provide care when it is possible to do so effectively and safely. Since its platform supports those who attend to the complex needs of a relative at home, C-QC illustrates well this attribute as well as the other user-oriented tools in our sample such as E-ON's solution for reducing iron deficiency, which is deployed at the community level. Though M-SP's portable device requires a medical specialist to establish a diagnosis, pictures of the eye fundus can be taken in a primary care facility, which could expedite the care pathway of rural patients (M-SP, 1). Interestingly, A-ON's hearing test was developed by a medical specialist for whom family doctors could provide more complete care if they had access to a ‘simple, inexpensive’ solution (A-ON, 1).

Health inequalities (4.2) refers to the avoidable health status differences across individuals and groups associated with one's socioeconomic status, social position and capabilities. Whereas H-QC shares on its platform practical information about the accessibility of public buildings for people with limited mobility, E-ON aligned its nutritional cooking tool with the SDGs, including ‘gender equality’ (E-ON, 1). L-SP's multidimensional intervention aims to support the economic and environmental contribution of informal waste-pickers and improve their safety and health. One of the challenges raised by its app, which connects waste-pickers to people who have recyclable materials to collect, is to address inequalities within this already vulnerable group:

I have a reality of waste-pickers who do not have a cell phone, and when you leave the state capital, it's much more visible. […] And I have an audience that has never developed the capacity to be a direct service provider for the general population or companies. So, I think the biggest technological challenge is human: how do we make it possible for them to use a cell phone? […] but also how do we educate the population to understand that our app is not an Uber […] many users say things like: ‘I’ve a cardboard box, why doesn't he come to pick it up?’ Well, a cardboard box is not worth 0.0001 cent for the waste-picker. (L-SP, 1)

Information about Eco-responsibility (3.6) was available for 5 innovations, including E-ON which carefully chooses its suppliers: ‘we think throughout our supply chain about our impact […] using boxes in recycled cardboard and vegetable ink’ (E-ON, 1). Since the population is ageing and the consumption of pharmaceuticals is growing from 8% to 10% every year, B-QC designed a pill bottle whose cap remains linked to it, so it could be entirely recycled. It also has ‘a very strict selection of suppliers’ who must demonstrate ‘an eco-responsible conscience,’ including the carrier ‘who won several awards for its greener trucks’ and the ‘closest possible’ polypropylene supplier (B-QC, 1). These examples suggest that Eco-responsibility may come with systemic effects over one's supply chain.

Since a Business model (3.4) typically entails a tension between the redistribution of financial returns to shareholders and the provision of a high-quality innovation, the RIH Tool considers whether the organization also seeks to provide value to society. While its cofounders had envisaged creating a cooperative, D-QC adopted the life sciences industry's typical for-profit model (D-QC, 1). In contrast, E-ON ‘worked very hard to become a B-Corp’Footnote 7 because the cofounders wanted the social mission to be laid out ‘in by-laws so that both the Board of directors and shareholders’ adhere to this commitment. Because of its mission, B-QC obtained environmental certifications. As K-SP's mission is to ‘break the cycle of poverty’ in which children with hearing losses grow, it employs individuals with particular needs (K-SP, 1). H-QC, J-SP, Q-SP and L-SP made their innovations freely available to end-users and E-ON, A-ON and G-ON offered significant discounts for specific groups.

For Inclusiveness, one of the two attributes with a low mean score (2.6), the RIH Tool's scale highlights the importance of making explicit the rationale and scope for stakeholder engagement and its impact on the innovation process. Interviewees described how they sought the input of stakeholders. Yet, this was not necessarily achieved through a formal method and, even though interviewees described the impact of stakeholders on the design process, their technical documentation did not always clarify such impacts (two conditions required for obtaining A on the scale). For instance, R-SP did surveys and obtained feedback from wheelchair users and their relatives:

the camera got smaller, the stem got much better [and we looked at] how design changes other people's perception of the person in the wheelchair […] when they stop using the competitor's technology and start using ours [it's] positive feedback that we […] even exploited commercially. (R-SP, 1)

For ELSIs, the second attribute with a low mean score (2.6), the RIH Tool considers the means by which negative impacts can be mitigated (e.g. patient decision-aids, data privacy policies, stigma-reduction measures). It thus brings into focus the sociocultural, legal and regulatory contexts in which the innovation is deployed. Interviews indicate ways in which ELSIs are considered throughout the innovation process and how certain means to mitigate them can be made available. For instance, ‘long before any data transparency policy was instituted in Latin America,’ R-SP developed and ‘customized’ a policy for the various facial recognition solutions it develops:

if you walk into [client's organization], you see a little sticker that says: ‘here, you have R-SP facial recognition technology. If you scan this QR Code, you will have access to the entire data transparency policy, you can opt-out and never be identified by R-SP technology again’. (R-SP, 1)

I started saying ‘do you want me to build a [3D printing] system that has the Black people do the manual labor and the White people do the intellectual labor? Because that's what you’re asking for. If they do the scanning and the printing and all the cool design still happens over here’. (G-ON, 1)

Overall, the interviews contextualize the different ways in which entrepreneurs materialize, to a varying extent, the RIH Tool's attributes. They also illustrate the tension between Health Inequalities and ELSIs, the synergies between Health relevance, Eco-responsibility and Frugality as well as practices related to Inclusiveness and ELSIs that are not necessarily made publicly explicit.

Discussion

To pursue the RRI community's efforts to better understand how different RRI assessment approaches and tools may enable entrepreneurs and innovators to integrate responsibility concerns into their practices, we summarize below our study's contribution and its research implications.

Contribution of our study

First, our study adds empirical findings to the scholarship on business-oriented RRI tools, which is limited by a lack of studies on their validity, reliability, applicability or uptake. Acknowledging that ‘feasibility’ of RRI matters as much as its ‘desirability’ (Rivard and Lehoux Citation2020), our findings showed that an external assessment relying on a circumscribed number of attributes, like the one underlying the RIH Tool, highlights concrete responsibility trade-offs and synergies. The large disparity we observed between the mean scores for Health inequalities and ELSIs (respectively, 4.2 and 2.6) is compatible with the notion that responsibility is a multifaceted concept (van Oudheusden Citation2014; Genus and Stirling Citation2018). Yet, our findings clarified why an innovation that scores high on Health inequalities since it addresses the needs of a vulnerable group may concurrently score low on ELSIs because identifying means to adequately mitigate nearly all applicable ELSIs may prove more complex with marginalized populations. Conversely, five attributes were fulfilled by the majority of the 16 innovations (Responsiveness, Health relevance, Frugality, Level and intensity of care and Health inequalities) and our qualitative findings highlighted synergies between Health relevance, Frugality and Eco-responsibility. Innovative practices that actively seek to combine such features would thus benefit from the joint insights of RRI, frugal innovation and sustainability scholars (Thorstensen and Forsberg Citation2016; Bhaduri and Talat Citation2020).

Second, acknowledging that a multiple case study design is meant to generate insights into ‘why’ and ‘how’ research questions, our study brings empirical support as well as nuances to the literature on RRI and businesses. Following an extensive literature review, Lubberink et al. (Citation2017) stressed the challenges of aligning innovation with societal goals that may not be in the direct interest of businesses. Our qualitative findings highlighted different subsector-specific dynamics that affect both the Inclusiveness and Business model attributes. These variations are aligned with the notion that entrepreneurs do not operate in a vacuum: policy incentives and institutional behaviors influence their disposition towards RRI processes as well as their business model (Stahl Citation2013; Genus and Stirling Citation2018). While innovations produced by not-for-profit organizations obtained higher overall RIH scores (4.1 on average) than those produced by for-profit organizations (3.5 on average), variations across regions were limited (from 3.5 to 3.8). Nonetheless, a larger number of not-for-profit organizations in our sample were located in São Paulo State (5/7). One possible explanation would lie with the fit between such legal structures and the aim of tackling social inequalities through technoscientific innovation in Brazil (Gaiger, Ferrarini, and Veronese Citation2015), a fit that may be less frequent in Quebec and Ontario where not-for-profit organizations more often rely on social innovation to pursue a similar mission (McMurtry and Brouard Citation2015). This interpretation would be compatible with social finance research which recognizes that an organizational model should be understood as ‘a means to an end, and not an end in itself’ since no model is inherently neither ‘more (or less) profitable’ nor ‘more (or less) socially impactful than any other’ (Cheng et al. Citation2010).

Lastly, our findings indicated that ELSIs and Inclusiveness were much less frequently fulfilled, which is puzzling in view of RRI's processual requirements. While the interviews clarified: (1) how data protection and privacy regulations were anticipated by some digital solutions developers; (2) how innovators attended to the rights and cultural specificities of vulnerable groups; and (3) why certain organizations work more collaboratively with users and communities and others focused on their clients and business partners, such practices were not always described in public documentation. This raises an important issue for external assessment approaches that rely solely on publicly available information. In our study, information about Eco-responsibility concerns was missing for 69% of our sample and the two requirements for interpreting the overall RIH score were met for 25% of the sample only. Does this imply that the Eco-responsibility attribute should be removed? Or that the Tool's requirements for interpreting its overall score should be relaxed? We do not think so. One valuable function of a summative tool like the RIH Tool is to signal the need for more environmental lifecycle analyses to be performed (Thorstensen and Forsberg Citation2016; Borowy and Aillon Citation2017). Otherwise, meeting RRI's expectations for responsible outcomes will remain elusive in view of established practices that disregard environmental impacts. In other words, summative tools may contribute to the political salience of RRI (van Oudheusden Citation2014). Even when the overall RIH score cannot be considered meaningful, the application of the Tool remains instructive. Our qualitative findings indicated how entrepreneurs materialized to varying extent its nine attributes, pointing to the potential of the RIH Tool to be used beyond strictly summative ends. For instance, innovation stakeholders such as investors, incubators or TTOs could use the RIH Tool as a ‘design brief’ to explain to the innovators they support why its nine attributes matter and should be documented in an accountable and transparent way. Since each attribute comes with a tangible four-level scale, the Tool could trigger creative reflections during the innovation process about ways to meet multiple attributes concurrently. Our findings indeed pointed to the way design efforts around Frugality and Eco-responsibility are mutually beneficial and can create entrepreneurial opportunities within the value chain (Ghosh and Rajan Citation2019; Bhaduri and Talat Citation2020).

The RIH Tool is of course not without limitations. While it seeks to influence innovation processes, fewer high quality information sources are typically available at an early stage. The score an innovation may obtain at a later stage is also likely to evolve because of changes brought to product- or organizational-level dimensions. Lastly, the RIH Tool does not include an exhaustive list of factors influencing corporate responsibility more broadly (e.g. user training, customer support, social and environmental performance reporting, etc.) and it was not designed to assess how impactful are different organizations (Voegtlin et al. Citation2019).

Implications for research: reconciling formative and summative ends in the development of RRI tools

The implications of our study for the RRI community lies with recognizing the value of the complementarity that exists between tools relying on a formative self-assessment approach and those relying on a summative external assessment (Scriven Citation1997). One important strength of the Responsibility Navigator is to support strategic-level reflections about ways to promote different responsibility-related goals across the organization (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2016). Such a higher-level formative approach is important to address how innovators working in large organizations can be adequately supported by top-level managers to implement RRI at the operational level. For smaller organizations, the ICT-based tool (Flipse Citation2018) and the RMoI tool (Long et al. Citation2020) can bring to innovators’ attention key process- and product-dimensions. To our knowledge, only the Responsible Innovation Compass (Tharani, Jarmai, and Nwafor Citation2020) and the RIH Tool combine process-, product- and organization-level dimensions, framing responsibility as a concept that links together the innovation, its development processes and the organization that makes it available to users. Because the RIH Tool supports an external accountable assessment, it may pre-empt ‘responsibility-washing’ and the ‘cherry-picking’ of certain RRI principles. In view of the social, economic and environmental responsibilities of businesses (Hin et al. Citation2014) and the large variations one can find across industries in terms of what behaving responsibly means (Voegtlin et al. Citation2019), tools that support evidence-informed transparent assessment processes are not sufficient but are necessary ‘to provide normative ground’ for RRI (Ceicyte and Petraite Citation2018). External assessment tools also resonate with social finance investors who already seek to measure and account for social, environmental and economic impacts and could provide an ‘effective lever’ for RRI (Voegtlin et al. Citation2019).

Because innovators and entrepreneurs are ‘bombarded’ with ‘myriads of tools’ and may ‘be perplexed rather than enlightened’ (Iatridis Citation2015), seeking to increase consistency in the way RRI's expectations are articulated in these tools may prove important. Rather than seeking to identify which is the ‘best’ approach or which is the ‘best’ tool, we believe RRI scholars should build on the community's diversified efforts to improve their overall capacity to transform entrepreneurial practices. A formative orientation is more conducive to the development of self-assessment and self-reflective tools and this tendency may be associated to the disciplinary traditions underlying RRI, where a critical in-depth stance towards innovation typically characterizes how scholars in social sciences and humanities develop new knowledge (van Oudheusden Citation2014). Groves (Citation2017) rightly underscores the risk of simplifying socio-ethical issues into quantifiable indicators and of ‘sliding into using RRI as a means of meeting pre-defined criteria.’ He thus points out the importance of resisting ‘a sensus communis in which all within the RRI community “know” what it means to do RRI before it is in fact done’ (Groves Citation2017).Footnote 8 Fostering both self-assessment and external assessment approaches that remain grounded in practice may avoid this pitfall and counterbalance the tendency to see business-oriented RRI tools as having to primarily ‘satisfy business needs’ (Iatridis Citation2015). Overall, reconciling formative and summative ends in the development of tools may prove sensible if the goal is to make RRI more actionable, that is, capable of making clear what the ‘right impacts’ are and how to get there (von Schomberg Citation2013).

Limitations of the study and further research

Performed within the context of an ongoing case study on organizations showing various responsibility features, this study's sample did not include innovations with a very low degree of responsibility. The transferability (or external validity) of our findings is thus limited to innovations that possess a number of RIH features and emerge from settings similar to Quebec, Ontario and São Paulo State. Despite these limitations as well as those of the RIH Tool, the internal validity of our findings is high since two raters independently scored the attributes and then resolved discrepancies with a third team member. In addition, publicly available documentation was supplemented with interviews, which clearly enriched the Tool's application process.

Further research could explore how different types of firms may benefit from the joint use of formative and summative RRI tools, examining the conditions in which self-assessment and external assessment approaches can reinforce each other and at different points in time. Since a business model is typically fleshed out at the point of inception of an organization, a period when entrepreneurs often ‘shoot in all directions’ to obtain financial support (Mazzucato and Penna Citation2016), further research on how business models may support the outcomes RRI is looking for is warranted (Lubberink et al. Citation2017).

Conclusion

Even if the values and practices of certain entrepreneurs may align well with RRI, the field has not emerged from their concerns (Kuhlmann et al. Citation2016). Whereas business-oriented RRI tools relying on self-assessment have the advantage of starting from what businesses are already doing (Jarmai, Tharani, and Nwafor Citation2020; van de Poel et al. Citation2020), RRI also calls for innovation-based entrepreneurial activities that differ from those established (Genus and Stirling Citation2018). Our study showed how the RIH Tool's external assessment approach can increase transparency and rigor in the way entrepreneurs’ commitment towards RRI gets materialized. Its attributes and scales can also provide them with concrete options and trade-offs to consider at the outset of their entrepreneurial journey. Because it is important to establish common grounds between the supply of RRI tools and their likely uptake by innovation practitioners, reconciling formative and summative ends in their development could contribute to make RRI's expectations towards businesses more actionable.

Contributorship

PL and HPS contributed substantially to the design of the study. HPS and RRO were responsible for data collection and HSP, RRO and PL were involved in data analyses. PL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings, revised critically preliminary versions of the paper and contributed important intellectual content. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Data statement

As per agreements with our study participants and following requirements of our Research Ethics Review Board, data is confidential.

Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Montreal (CERES-D #17-024) and from the National Commission of Ethics in Research in Brazil (CONEP #2.673.002).

Geolocation information

Canada and Brazil.

Acknowledgments

This article stems from the In Fieri research program (www.infieri.umontreal.ca) on Responsible Innovation in Health, which is led by the corresponding author. We are grateful to the entrepreneurs who generously shared their experiences and insights, and made room in their busy schedule to contribute to our research activities. Members of our research team provided us with insightful comments throughout the study: Dominique Grimard, Renata Pozelli, Andrée-Anne Lefebvre, Hassane Alami and Carl-Maria Mörch. We thank the Editor and two anonymous reviewers for helpful criticisms of an earlier version of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Pascale Lehoux completed a bachelor degree in Industrial Design, a Ph.D. in Public Health (University of Montreal) and postdoctoral studies in Science & Technology Dynamics (University of Amsterdam). She is Professor with the Department of Health Management, Evaluation and Policy at the School of Public Health of University of Montreal. When holding the Canada Research Chair on Innovation in Health (2005–2015), her research clarified the impact of business models, capital investment and economic policy on technology design processes in academic spin-offs. Her current work focuses on Responsible Innovation in Health, examining the way hybrid organizations, impact investing and alternative business models lead to innovations that better address the needs and challenges of health systems.

Hudson P. Silva holds a bachelor's degree in economics (State University of Campinas), a Ph.D. in Public Health (University of São Paulo) and completed his postdoctoral studies in Health Innovation (University of Montreal). He is a Senior Research Advisor with the In Fieri research program on Responsible Innovation in Health, based at the Public Health Research Center (CReSP) of University of Montreal. Before moving to Montreal, Canada, he was a Public Policy and Management professor at the State University of Campinas. He also worked as a technical advisor for the Brazilian Ministry of Health and as a research assistant at the Center for Public Policy Studies (University of Campinas) and at the Department of Social and Preventive Medicine (University of São Paulo).

Robson Rocha de Oliveira holds a MD degree, a Ph.D. in Preventive Medicine, and a Preventive and Social Medicine fellowship (University of São Paulo), with a particular emphasis on health management. He is a postdoctoral fellow with In Fieri research program on Responsible Innovation in Health (RIH) at the Center for Public Health Research of the University of Montreal (CReSP). He was a medical manager at the Hospital das Clínicas of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine, clinical professor and director of the undergraduate medical program at Anhembi Morumbi University (Laureate International Universities). His current research interests include clinically-oriented RIH practices and networked responsibility approaches for responsible digital innovation in health.

Lysanne Rivard holds a bachelor's degree in Psychology, a master's degree in Child Studies, and a Ph.D. in Educational Studies (McGill University). She is Senior Research Advisor with the In Fieri research program on Responsible Innovation in Health (RIH) at the Center for Public Health Research of the University of Montreal (CReSP). Health, gender equality, technology and innovative practices that value and integrate participants’ knowledge and priorities are at the heart of her research interests. With In Fieri, she conducts qualitative and participatory research with health innovators on the design and operationalization of RIH.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We use the term ‘entrepreneurs’ to refer to actors who may base their entrepreneurial activities around an innovative product, service or business model and the term ‘innovators’ to refer to actors who directly contribute to the design of an innovation (e.g. biomedical engineers, designers, clinicians, etc.). In certain cases, innovators also become entrepreneurs, but this is not automatic.

2 We excluded Corporate Social Responsibility tools as their capacity to support RRI is fully described by Iatridis (Citation2015).

3 This characteristic is informed by best practices in the field of health innovation. However, it does not imply that experts’ views are considered more important than those of non-experts. As illustrated in the findings, the RIH Tool's Inclusiveness attribute recognizes the importance of integrating multiple stakeholders’ views in innovation development processes and its Health inequalities and ELSIs attributes capture an innovation's key societal impacts.

4 The first step when applying the RIH Tool entails examining two inclusion criteria (Determinants of health, Innovativeness) and two exclusion criteria (Unavailability, Corporate social irresponsibility). The former are meant to select novel solutions that safely and effectively address a determinant of health. The latter exclude from the assessment process innovations that are not available to intended users or that are produced by organizations involved in irresponsible corporate actions.

5 If more than one type of information is used to score an attribute, the source of highest quality is reported.

6 The innovation policy scholarship that examined how financing strategies (such as venture capital) directly affect business models at an early stage proved particularly instructive when developing the Business model attribute. Equally useful was the concept of ‘blended value’ (Emerson Citation2003), which identifies how business models may simultaneously generate social and economic value.

7 Organizations that obtain a B Corporation certification are committed to monitor and improve their social and environmental performance and to demonstrate transparency and accountability. The certification examines the impact of the company's operations and business model on its workers, its clients, the community and the environment. It also examines the supply chain, raw material sourcing, charitable giving and employee benefits.

8 This is one of the reasons why the constructs of the RIH Tool were consolidated over time, through an iterative deductive and inductive process, and feedback from health innovators gathered (Rivard and Lehoux Citation2020).

References

- Bhaduri, Saradindu , and Nazia Talat . 2020. “RRI Beyond Its Comfort Zone: Initiating AdDialogue with Frugal Innovation by ‘the Vulnerable’.” Science, Technology and Society , 1–18. doi:10.1177/0971721820902967.

- Borowy, Iris , and Jean-Louis Aillon . 2017. “Sustainable Health and Degrowth: Health, Health Care and Society Beyond the Growth Paradigm.” Social Theory & Health 15 (3): 346–368.

- Brand, Teunis , and Vincent Blok . 2019. “Responsible Innovation in Business: A Critical Reflection on Deliberative Engagement as a Central Governance Mechanism.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (1): 4–24.

- Ceicyte, Jolita , and Monika Petraite . 2018. “Networked Responsibility Approach for Responsible Innovation: Perspective of the Firm.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1720.

- Cheng, Paul , Emilie Goodall , Rob Hodgkinson , and John Kingston . 2010. “Financing the Big Society: Why Social Investment Matters.” Kent: CAF Charities Aid Foundation September 2010: 16.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M , and Melissa E Graebner . 2007. “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 25–32.

- Emerson, J. 2003. “The Blended Value Proposition: Integrating Social and Financial Returns.” California Management Review 45 (4): 35–51.

- Fisher, Erik , Michael O’Rourke , Robert Evans , Eric B. Kennedy , Michael E. Gorman , and Thomas P. Seager . 2015. “Mapping the Integrative Field: Taking Stock of Socio-Technical Collaborations.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 2 (1): 39–61.

- Flipse, Steven. 2018. “Using an ICT Tool to Stimulate Multi-Disciplinary Innovation Teams in Establishing Responsible Research and Innovation Practices in Industry.” ORBIT Journal 1 (3): 1–13.

- Flipse, Steven M. , and Emad Yaghmaei . 2018. “The Value of ‘Measuring’ RRI Performance in Industry.” In Governance and Sustainability of Responsible Research and Innovation Processes , edited by F. Ferri , 41–47. Cham, Switzerland: SpringerBriefs in Research and Innovation Governance.

- Gaiger, L. I. , Adriane Ferrarini , and M. Veronese . 2015. “Social Enterprise in Brazil: An Overview of Solidarity Economy Enterprises.” In: ICSEM Working Papers.

- Genus, Audley , and Andy Stirling . 2018. “Collingridge and the Dilemma of Control: Towards Responsible and Accountable Innovation.” Research Policy 47 (1): 61–69.

- Ghosh, S. , and J. Rajan . 2019. “The Business Case for SDGs: an Analysis of Inclusive Business Models in Emerging Economies.” International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 26 (4): 344–353.

- Goffin, Keith , Pär Åhlström , Mattia Bianchi , and Anders Richtnér . 2019. “State-of-the-Art: The Quality of Case Study Research in Innovation Management.” Journal of Product Innovation Management . doi:10.1111/jpim.12492.

- Groves, Christopher. 2017. “Review of RRI Tools Project, http://www.rri-tools.eu .” Journal of Responsible Innovation 4 (3): 371–374.

- Hin, Gaelle , Michel Daigney , Denis Haudebault , Kalina Raskin , Yann Bouché , Xavier Pavie , and Daphné Carthy . 2014. “KARIM (Knowledge Acceleration Responsible Innovation Meta Network). Introduction to a Guide to Entrepreneurs and Innovation Support Organization.” In.

- Iatridis, Kostas. 2015. Identification of CSR Tools Related to Responsible Research and Innovation Principles . https://www.researchgate.net/publication/290974319_Identification_of_CSR_tools_related_to_Responsible_Research_and_Innovation_principles?enrichId=rgreq-800985149cbb9cf2c3537c50d9c327bd-XXX&enrichSource=Y292ZXJQYWdlOzI5MDk3NDMxOTtBUzozMTkyNTQ2OTg2MjcwNzRAMTQ1MzEyNzY1OTU5Ng%3D%3D&el=1_x_3&_esc=publicationCoverPdf

- Jarmai, Katharina , Adele Tharani , and Caroline Nwafor . 2020. “Responsible Innovation in Business.” In Responsible Innovation , edited by Katharina Jarmai , 7–17. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Kuhlmann, Stefan , Jakob Edler , Gonzalo Ordóñez-Matamoros , Sally Randles , Bart Walhout , Clair Gough , and Ralf Lindner . 2016. “Responsibility Navigator.” In: edited by Stefan Kuhlmann and Ralf Lindner. Karlsruhe, Germany: Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI.

- Lehoux, Pascale , Hudson Pacifico Silva , Renata Pozelli Sabio , and Federico Roncarolo . 2018. “The Unexplored Contribution of Responsible Innovation in Health to Sustainable Development Goals.” Sustainability 10 (11): 4015.

- Lindner, Ralf , Stefan Kuhlmann , Sally Randles , Bjørn Bedsted , Guido Gorgoni , Erich Griessler , Allison Loconto , and Niels Mejlgaard . 2016. “Navigating Towards Shared Responsibility in Research and Innovation. Approach, Process and Results of the Res-AGorA Project.” In. Karlsruhe, Germany: Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI.

- Long, Thomas B , Vincent Blok , Steven Dorrestijn , and Phil Macnaghten . 2020. “The Design and Testing of a Tool for Developing Responsible Innovation in Start-up Enterprises.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 45–75.

- Lubberink, Rob , Vincent Blok , Johan van Ophem , and Onno Omta . 2017. “Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Responsible, Social and Sustainable Innovation Practices.” Sustainability 9 (5): 721. doi:10.3390/su9050721.

- Lubberink, Rob , Vincent Blok , Johan van Ophem , and Onno Omta . 2019. “Responsible Innovation by Social Entrepreneurs: An Exploratory Study of Values Integration in Innovations.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 6 (2): 179–210. doi:10.1080/23299460.2019.1572374.

- Mazzucato, Mariana , and Caetano Penna . 2016. “The Brazilian Innovation System: A Mission-Oriented Policy Proposal.” In Avaliação de Programas em CT&I. Apoio ao Programa Nacional de Ciência (Plataformas de Conhecimento) , 119. Brasília, DF: Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos.

- McMurtry, J. J. , and F. Brouard . 2015. “Social Enterprises in Canada: An Introduction.” Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research 6 (1): 6–17.

- Porcari, Andrea , Daniela Pimponi , Elisabetta Borsella , and Elvio Mantovani . 2019. “PRISMA RRI-CSR Roadmap. Deliverable 5.2.” In. European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, Grant Agreement No 710059.

- Rivard, Lysanne , and Pascale Lehoux . 2020. “When Desirability and Feasibility Go Hand in Hand: Innovators’ Perspectives on What Is and Is Not Responsible Innovation in Health.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (1): 76–95.

- Roncarolo, Federico , Antoine Boivin , Jean-Louis Denis , Rejean Hébert , and Pascale Lehoux . 2017. “What Do We Know About the Needs and Challenges of Health Systems? A Scoping Review of the International Literature.” BMC Health Services Research 17 (1): 636.

- Scriven, Michael. 1997. “Truth and Objectivity in Evaluation.” In Evaluation for the 21st Century: A Handbook , edited by Eleanor Chelimsky , and William R. Shadish , 477–500. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Silva, H. P. , A.-A. Lefebvre , R. O. Rocha , and P. Lehoux . 2020. “Fostering Responsible Innovation in Health: An Evidence-Informed Assessment Tool for Decision-Makers.” International Journal of Health Policy and Management . doi:10.34172/IJHPM.2020.34

- Silva, Hudson Pacifico , Pascale Lehoux , and Nicola Hagemeister . 2018. “Developing a Tool to Assess Responsibility in Health Innovation: Results from an International Delphi Study.” Health Policy and Technology 7 (4): 388–396.

- Silva, Hudson Pacifico , Pascale Lehoux , Fiona Alice Miller , and Jean-Louis Denis . 2018. “Introducing Responsible Innovation in Health: A Policy-Oriented Framework.” Health Research Policy and Systems 16 (1): 90.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten. 2013. “Responsible Research and Innovation: The Role of Privacy in an Emerging Framework.” Science and Public Policy 40 (6): 708–716.

- Stahl, Bernd Carsten. 2017. “The ORBIT Self-Assessment Tool.” ORBIT Journal 1 (2). doi:10.29297/orbit.v1i2.59.

- Stilgoe, Jack , Richard Owen , and Phil Macnaghten . 2013. “Developing a Framework for Responsible Innovation.” Research Policy 42 (9): 1568–1580. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008.

- Tharani, A. , K. Jarmai , and C. Nwafor . 2020. “Responsible Innovation Compass.” http://self-check-tool.innovation-compass.eu/faq.

- Thorstensen, Erik , and Ellen-Marie Forsberg . 2016. “Social Life Cycle Assessment as a Resource for Responsible Research and Innovation.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 3 (1): 50–72.

- Timmermans, Job. 2017. “Mapping the RRI Landscape: An Overview of Organisations, Projects, Persons, Areas and Topics.” In Responsible Innovation 3 , edited by L. Asveld , R. van Dam-Mieras , T. Swierstra , S. Lavrijssen , K. Linse , and J. van den Hoven , 21–47. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- van de Poel, Ibo , Lotte Asveld , Steven Flipse , Pim Klaassen , Zenlin Kwee , Maria Maia , Elvio Mantovani , Christopher Nathan , Andrea Porcari , and Emad Yaghmaei . 2020. “Learning to Do Responsible Innovation in Industry: Six Lessons.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 7 (3): 697–707. doi:10.1080/23299460.2020.1791506

- van Oudheusden, Michiel. 2014. “Where Are the Politics in Responsible Innovation? European Governance, Technology Assessments, and Beyond.” Journal of Responsible Innovation 1 (1): 67–86.

- Voegtlin, Christian , Andreas Georg Scherer , A. McWilliams , Deborah Rupp , Donald Siegel , Günter Stahl , and David Waldman . 2019. “New Roles for Business: Responsible Innovators for a Sustainable Future.” In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological and Organizational Perspectives , edited by Abagail McWilliams , Deborah E. Rupp , Donald S. Siegel , Günter K. Stahl , and David A. Waldman , 338–357. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- von Schomberg, René . 2013. “A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society , edited by R. Owen , J. R. Bessant , and M. Heintz , 51–74. Southern Gate: John Wiley & Sons.

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Los Angeles: SAGE.