ABSTRACT

The rapid development of human genome editing (HGE) techniques evokes an urgent need for forward-looking deliberation regarding the aims, processes, and governance of research. The framework of anticipatory governance (AG) may serve this need. This article reviews scholarly discourse about HGE through an AG lens, aiming to identify gaps in discussion and practice and suggest how AG efforts may fill them. Discourse on HGE has insufficiently reckoned with the institutional and systemic contexts, inputs, and implications of HGE work, to the detriment of its ability to prepare for a variety of possible futures and pursue socially desirable ones. More broadly framed and inclusive efforts in foresight and public engagement, focused not only upon the in-principle permissibility of HGE activities but upon the contexts of such work, may permit improved identification of public values relevant to HGE and of actions by which researchers, funders, policymakers, and publics may promote them.

Human genome editing and anticipatory governance

Calls for responsibility in human genome editing

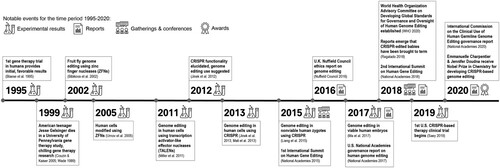

The prospect of human genome editing (HGE) has aroused significant concern and contention in scientific, bioethics, and policy communities over the last six years. This furor has emerged in response to a series of publications describing genome editing in nonviable and viable human embryos (Liang et al. Citation2015; Kang et al. Citation2016; Ma et al. Citation2017); to vast and rapid expansion in the use of facile CRISPR-based genome editing techniques (see STAT Citation2016); and to the 2018 announcement that U.S.-trained researcher He Jiankui had modified the genes of two recently-born ‘CRISPR babies’ (). International scientific and bioethics communities reacted to the latter development with shock and horror (Greely Citation2019a). This response belies the fact that concerns about human genome editing have been raised (and dismissed) for decades (Evans Citation2002; Hurlbut Citation2015; Mathews et al. Citation2015); and that a highly competitive scientific culture lionizing ‘breakthrough’ research, while often leaving it to researchers to set and interpret limitations on their own activities, might be expected to produce reckless and unaccountable behavior (Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha Citation2019).

Figure 1. Select major events in recent human genome editing history. Expanded from a figure in Kim (Citation2016).

The rapid pace of HGE development raises significant ethical, legal, and social challenges. HGE's possible courses implicate questions of patient and population risk; normativity and marginalization; access to medicine and economic inequality; the morality of (various types of) genome modification; ways of understanding and relating to human bodies and health; the political economy of research; democratic or other authority in and over innovation; biosecurity; and global governance, among others. Four decades ago, David Collingridge (Citation1980) observed that it is difficult to predict the outcomes of technological innovation early in development, and difficult to alter later-stage ‘locked-in’ technological systems in response to undesirable outcomes. Prior attempts to address this ‘dilemma of social control’ in the biosciences have suffered from a lack of institutional leverage, delayed ethical reckoning, a reactionary stance, and a failure to effectively engage citizens with scientists early in the development process (Jasanoff Citation2015; Juengst Citation2017; King, Lord, and Lemley Citation2017). Consensus reports from organizations including the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (Citation2017); hereafter National Academies Citation2017, the U.K. Nuffield Council on Bioethics (Citation2016, Citation2018), and the German Ethics Council (Citation2019) have asserted that genome editing governance should be informed by substantive foresight and public engagement, dealing with ‘both facts and values[,] and in particular how anticipated changes will affect the things people value’ (National Research Council Citation2008, 3; quoted in National Academies Citation2017, 127). These are only some of the most prominent entries in a voluminous and growing body of discussion regarding how HGE research may be made socially responsible.

It is unclear, however, how such calls might translate to practice. They are generally vague, with little explicit discussion of how public engagement might affect the direction and governance of research. Many expert statements contain specific and direct governance prescriptions for the management of conventional biomedical research concerns but address broader and more systemic issues only in passing. The literature is filled with detailed discussions of patient risk-benefit ratios, the licensing of research tools, and the management of data. But when addressing questions about the proper aims of innovation, the distribution of its costs, risks, and benefits, the different interests, constituencies, and ways of life which the development of new biomedical treatment regimes might support or harm, most authors are content to call for greater public involvement – usually after research but before deployment – and leave the discussion there. Even demands that ‘broad societal consensus’ precede any deployment of germline HGE do not define how such consensus could manifest or be discerned (Brokowski Citation2018). And even statements which ostensibly recognize public interests in HGE tend to prioritize researchers’ needs and values over others, where they recognize possible conflicts at all. A cynical observer might easily conclude that, beneath the discourse of ‘responsibilization,’ business proceeds as usual in HGE research. The interests of researchers and research funders predominate, shaping the aims and forms of innovation while leaving ‘public engagement’ to smooth the way and clean up the consequences.

Anticipatory governance as a framework for building societal values into innovation processes

In recent decades, scholars of science, innovation, and public administration have argued that more inclusive and participatory governance of innovation, variously, is normatively required; can improve the quality and efficacy of decision-making on complex, contentious, and socially important issues; and could reduce backlash (earned or unearned) to research and development enterprises (Felt and Wynne Citation2007; Funtowicz and Ravetz Citation1993; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013; Wilsdon and Willis Citation2004; Wynne Citation2001). Research responding to these arguments has aimed to bring not only the products, but the aims, aspirations, and processes of innovation under democratic governance; and, through strategies and practices of foresight, reflexivity, and broader inclusion and societal integration, to ‘bend … the long arc of technoscience more toward humane ends’ (Guston Citation2014, 218; see also European Commission [Citation2013] Citation2015; Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012; von Schomberg Citation2013). By building capacity for flexibility, evaluation, and adaptation, these practices hope to sidestep the dilemma of social control and prevent irreversible path dependencies. They aim less to predict the forms and impacts of particular technological interventions than to promote responsibility in development – to build capability within a broad array of social actors to identify, respond to, and learn from a plurality of potential development pathways.

The following discussion surveys the state of scholarly discourse on HGE governance, aiming to determine how the ongoing discourse of responsibility in HGE maps onto actual scholarly work. This is not a merely critical exercise. We hope here to lay groundwork for more robust and substantive work to align HGE development with societal needs and values.

For this purpose, we use the frame of ‘anticipatory governance,’ (AG) one of several emerging from recent efforts to improve the societal outcomes of research (Barben et al. Citation2008; see also Conley Citation2020; Fisher, Mahajan, and Mitcham Citation2006; Guston and Sarewitz Citation2002; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). Like other such frames, AG is polythetic and multivalent, referring more to a broad set of overlapping research and governance agendas than to a strict set of methodological principles and lines of inquiry. Nonetheless, it has consistently been identified with three broad ‘capacities’ useful or necessary to aligning innovation processes with public values under the Collingridge constraints (Barben et al. Citation2008; Fisher, Mahajan, and Mitcham Citation2006; Fisher and Maricle Citation2015; Guston Citation2014). Foresight focuses on the construction and evaluation of plural sets of rich and plausible futures as occasions for reflection, tools for planning, and exercises for capacity-building to prepare and respond for a broad swathe of potential developments and implications in emerging technologies. Engagement centers on the substantive exchange of ideas and reasons within and between publics and technoscientific decision-makers, aiming to identify public values at stake in technological development and implementation and to build capacities in publics and decision-makers to shape technologies to respect and support them. Integration refers to development among core research actors and decision-makers of capabilities and institutionalized processes to consider and respond to the social and normative contexts of their work. Barben et al. (Citation2008, 989) describe integration as the incorporation of normative considerations ‘into laboratory and other technoscientific decision processes.’ Processes and capacity-building mechanisms may include engagement and foresight activities, as well as collaborations and interchange with social and humanistic experts. These capacities are not merely academic ideals, but capabilities demonstrated in past efforts to reckon with and shape emerging technologies (Conley Citation2020). Our treatment of integration rests heavily on the notion of governance, drawing attention to how values become embedded in specific decision-making processes and concrete practices related to control and care.

The three capacities do not, of course, operate separately in theory or in practice. Robust foresight requires engagement between experts and publics, and between social and technical experts. Engagement requires a broad view on possible futures and their important constituents, and again the cooperation of social and technical expertise in discussing past and potential socio-technical developments with the publics. Integration aims to build reflective and forward-looking capabilities and insights of sorts often developed through foresight, engagement, and interdisciplinary collaboration therearound. The interdependent, synergistic implementation of AG strategies has been described as ‘ensembelization’ (Michelson Citation2016), and Conley (Citation2020) has suggested that such coordination should be considered a fourth ‘core capacity.’ We do not treat it separately here, noting that if it is difficult and artificial to disentangle foresight, engagement, and integration, it may be even more counterintuitive to pare out their joint deployment. We do, however, throughout remark on ways in which development of each capacity in HGE governance and research institutions bears upon development of the others.

We focus on HGE for three mundane and pragmatic reasons. First, as will be shown, much contemporary discourse around genome editing calls for more forward-looking, socially reflective, and publicly engaged research and governance in human genome editing, and we wish to examine whether and how this is being done. Second, this review is intended to provide an intellectual basis and conceptual frame for a research project using anticipatory governance techniques to produce governance recommendations around human genome editing. Third, while HGE is not wholly unique among emerging bioscience technologies and topics in institutional and systemic context, it is unique in cultural profile and the sheer volume of scholarly discourse dedicated to it. Any gaps or failures in HGE discourse and governance are rather more egregious than they might be in a less high-profile or frequently discussed domain. We do not expect that the conclusions drawn here are unique – indeed, we draw on related arguments on topics ranging from stem cell research (Hurlbut Citation2017) to gene drive (Kuzma et al. Citation2018) to the biosciences more generally (Jasanoff Citation2005). However, the practical limitations of a single project and manuscript oblige us to focus on our practical aims, i.e. to lay a foundation for AG of HGE, over comparison across different fields within the biosciences.

Given the breadth, diversity, and rapid growth of HGE discourse, we cannot aspire to a comprehensive treatment. Instead, we aim for a synoptic view, oriented to identify how preexisting scholarly discourse may inform anticipatory governance of genome editing; and what novel efforts an AG framing might suggest. Section 2 discusses the literature search process and its results. Section 3 surveys scholarly discussion of HGE governance, emphasizing that framings built around expert control ‘upstream’ in the innovation process and recommending public engagement around a limited set of ‘downstream’ issues do little to improve alignment between public values and research projects. This approach is contrasted to the thoroughgoing treatment of societal values suggested by the AG concept of integration. Section 4 discusses efforts toward foresight in the HGE space, arguing that excessive focus on what should happen in the HGE space has hamstrung efforts to consider or prepare for what could happen Section 5 reviews calls for and practice of public engagement around HGE, observing (1) that the former far outstrip the latter and (2) that both discussion and practice have tended to exclude from consideration many of the aspects of HGE activities most relevant to historical public concerns about innovation. Section 6 concludes with practical recommendations for work aiming to help researchers, policymakers, and publics to think about the possible futures of HGE in more robust and socially embedded ways.

Method and outcomes

To develop an understanding of the contemporary scholarly conversation around HGE governance, foresight, and engagement, relevant literature was identified via Google Scholar, JSTOR, EBSCO Academic Search Premier, and Web of Science search and practitioner recommendation between June and October of 2019 (inclusive). Keywords included ‘human genome editing,’ ‘human gene editing,’ ‘anticipation,’ ‘foresight,’ ‘futures,’ ‘engagement,’ ‘public engagement,’ ‘public opinion,’ and ‘public views.’ Searches were limited to publications from 2014 forward, as new, CRISPR-cas9-based techniques made human genome editing significantly more plausible over this timespan. Publications were included which (A) carried significant prominence in HGE governance discourse, as indicated by high citation counts or by origins with broadly influential organizations or persons; (B) represented or referenced views underrepresented in mainstream expert discourse; or (C) bore upon the aims or conduct of anticipatory governance in the HGE space.

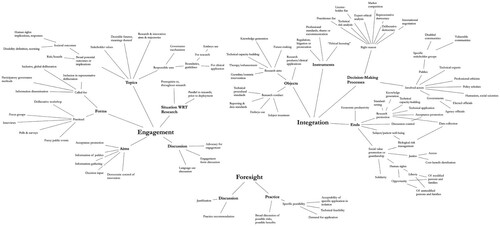

The search process yielded 133 documents, which were manually read and sorted for relevance. Review yielded zero reports of formal foresight efforts, as more thoroughly discussed below; though most documents regarding HGE included informal speculation and pronouncement about the future import of genome editing technologies. A single consensus report (German Ethics Council Citation2019) attempted to deal with future possibilities in a systematic way, but we found this approach not to meaningfully constitute ‘foresight’ for reasons discussed below. We found fifteen documents describing public engagements or public opinion studies around human genome editing (Appendix), one of which (Blendon, Gorski, and Benson Citation2016) was itself a metaanalysis of 17 public opinion polls. Attempts to identify integration efforts in HGE produced a broad topical mapping of topics treated in HGE governance literature, which in turn provides the basis for a critique of HGE discourse and articulation of the need for anticipatory governance presented in Section 3. A general topical map of the treated literature appears in . For a more systematic review of governance discourse on germline HGE, around which most discussion has centered, we refer the reader to Brokowski (Citation2018).

Figure 2. Conceptual map of topics treated in reviewed literature, organized by AG interests in engagement, foresight, and integration.

This procedure excluded activities and perspectives not represented in the academic or gray literature. Many bioscience laboratories include embedded bioethicists, but the work of those professionals is not always reported in the literature. In addition, foresight or engagement work conducted by and for policy or advocacy organizations, private corporations, or science museums may not be thoroughly reported. Furthermore, HGE governance discussions have to a significant extent taken place at a spate of expert conferences and meetings, the most important results of which are not always immediately textually reported. Last, our review has been limited to the English-language literature, which inescapably elides important parts of this international conversation. Despite these limitations, we feel our work provides a useful high-level overview of the state of scholarly governance discourse around HGE, identifies important gaps, and provides directions and guidelines for future research and practice.

Integration or not? Governance discourse and division of ethical labor in human genome editing

Integration in anticipatory governance and human genome editing

Although integration is conventionally discussed as the third pillar of anticipatory governance, we address it first here for purposes of conceptual framing. The overall aim of AG could be described as integration of societal needs and values throughout innovation systems and processes. Some articulations of integration as a subcomponent of AG are similarly expansive (e.g. Barben et al. Citation2008; Guston Citation2014; Rodríguez, Fisher, and Schuurbiers Citation2013). However, the term is usually used in the somewhat more constrained sense of building specifically in research practitioners, research decision-makers, and research organizations the capabilities to reflect upon and respond to the broader societal contexts of their research (Fisher et al. Citation2015). Integration can focus either or both on tacit habits of thought and personal skills in ‘laboratory life’ and on institutionalized procedures of interchange with social and humanistic scholars, institutionalization of feedback mechanisms on technology, foresight, and public engagement (Barben et al. Citation2008; Fisher, Mahajan, and Mitcham Citation2006; Fisher and Maricle Citation2015; Guston Citation2010). As defined here, integration is more flexible and potentially expansive than foresight or public engagement. It might even, in consonance with the linguistic parallel noted above, be taken to subsume both categories – particularly on the recognition that it is difficult to imagine effective foresight or engagement without integration of technical experts. It is, thus, more difficult to judge whether (and, if so, how well) integration has been called for or performed around HGE.

Discussions of ‘ethical, legal, and social implications’ of HGE at expert meetings, in the pages of journals, and in consensus statements and reports might be understood as efforts in integration – either conceived as an interchange between social and technical experts or more broadly understood as efforts to bring normative reflection and social value considerations into the planning and conduct of research. On another view, much of this discourse has bounded broader societal considerations outside of laboratory work and knowledge-producing research, to be addressed through as-yet-unarticulated mechanisms, often only on the brink of widespread HGE application. This impulse aligns with historical responses to societal or ethical concerns in biomedical research. These have tended to produce novel expert institutions claiming ownership over normative questions and offering bright lines constraining research topics and procedures (e.g. the profession of bioethics and special ethics commissions; see Hurlbut Citation2017; Jasanoff Citation2005), rather than to build societally oriented reflective capacities in practicing researchers or to throw fundamental research decisions open to public choice. Such orientation runs contrary to the aims of AG.

We thus face a conceptual and rhetorical difficulty. There is certainly societal reckoning going on, a fair portion of it by technical experts; but in rather constrained ways which elide many of the broad questions of political economy, societal context and the proper aims of research which AG seeks to democratize. Is the voluminous discourse on the ethical principles that ought to guide HGE and their implications for particular sorts of action integration? Going by assertions that integration (or some more sharply defined subvariety, e.g. ‘collaborative socio-technical integration’; see Fisher et al. Citation2015) should substantively alter the thought and practical routines of technical practitioners, the answer is probably ‘no.’ Yet this discourse is the primary means by which ethicists, policy scholars, and technical experts are attempting to bring societal values into HGE governance, which may align with more expansive definitions of integration as broadly concerned with decision-making throughout research systems (e.g. Barben et al. Citation2008).

Fortunately, the label is less important than the analysis. We went looking for examples of integration in the HGE space. We found an enormous body of discussion growing out of traditions in bioethics and ‘ethical, legal, and social implications’ research offering concerns, analyses, and prescriptions about the social dimensions of HGE research. For purposes of legibility, we focus our discussion on the different repertoires of values which have been discussed as at stake in the development of HGE; and on the specific questions or issues around which expert discussion has organized. Expert discourse has recognized an impressive set of values at stake in HGE. But its relatively tight focus on conditions of permissibility for particular varieties of HGE work and on mechanisms to operationalize these judgments has stymied full and substantive treatment of public values, and of the broad systemic and institutional factors which affect them.

Value articulations: what's at stake?

To develop an understanding of the stakes of HGE development for different professional and public communities, we turn first to prior scholarly treatment of values implicated in or by the development, practice, and governance of HGE. Expert discussion has recognized an impressive register of such values, here for purposes of legibility lumped into repertoires of ‘science values,’ ‘bioethics values,’ and ‘public values’ (see generally Toulmin Citation1966). ‘Science values’ tend to represent the technical interests and aspirations of practicing research communities; ‘bioethics values’ the traditional foci of professionalized bioethics, and ‘public values’ well-established public concerns or preferences (see Bozeman Citation2007; and Bozeman and Sarewitz Citation2011), often framed in the language of rights or public priorities. Though formation of an engagement with public concerns and constituencies around HGE has been limited thus far, scholarly treatments have recognized many ways in which HGE development cuts across longstanding public values.

We distinguish between bioethics and public values because, while bioethics has since its inception (as clinical ethics) been expected to ensure that research respects societal values, its ambit has in practice been mostly limited to concerns of patient risk, benefit, dignity, and property (e.g. HHS Citation1979). Conventional patient-risk orientations have in recent decades been complicated by increased attention to the relationships between biomedicine, social normativity, distributional justice, and social solidarity; and by publics advancing novel skepticisms or concerns against the remote authority of medical professionals. But professional bioethics still operates, despite a recent empirical turn, as its own specialized sphere of priorities discontinuous with many contemporary public concerns regarding science and innovation. Attention to ‘ethical, legal, and social implications’ of technologies often fails to account for the ways in which technologies are themselves implicated and shaped by societal and institutional understandings of and aspirations regarding moral right and authority, legal permissibility or incentive, and societal good, ill, or change (Hurlbut Citation2018).

By way of illustration, the aims of health research are strongly influenced by wealth distribution, with less than 10% of global research funding spent on diseases afflicting over 90% of the world's population (Ramsay Citation2001; Vidyasagar Citation2006). That is, research focuses on the diseases of the rich, not the diseases of the many. For another example of the ways in which human choices and institutions shape research, the ongoing patent battle between the University of California and the Broad Institute has already had and will continue to have significant impacts on which actors are able to use genome editing techniques for what purposes, who profits, and whether genome editing technologies will concentrate or distribute economic power (Cohen Citation2020). Overly broad patents can incentivize intellectually and economically wasteful duplication of effort and grant patent-holders disproportionate power over the future shape of innovation (Contreras and Sherkow Citation2017; Rai and Cook-Deegan Citation2017). Meanwhile, some scholars (e.g. Guerrini et al. Citation2017) have explicitly called for owners of genome editing IP to wield their licensing power as a form of ethical governance. As a third example, He Jiankui was able to create CRISPR babies because of political settlements that (1) permitted HGE technologies to develop to the point of applicability without significant societal review and (2) tend to leave scientists to self-govern (Hurlbut Citation2018). And, as a fourth, much of the impetus for preventative genome editing derives from the cultural value placed on allowing persons with severe genetic diseases to have genetically related children. In short, societal values, structures, political settlements, and power distributions significantly shape the aims and conduct of research; and which values are furthered, respected, or undercut by such work.

As manifested in HGE discourse, traditional ‘science values’ include rigorous development of knowledge and technical capacity (e.g. Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Brokowski Citation2018; Chan et al. Citation2015; Doudna Citation2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2018; Pei et al. Citation2017) and public support for and investment in research (e.g. Church Citation2015; Lancet Citation2017; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; Neuhaus and Caplan Citation2017). Standard ‘bioethics and clinical ethics values’ include the well-being and autonomy of research subjects and patients (e.g. Chneiweiss et al. Citation2017; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Mintz, Loike, and Fischbach Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018; Smolenski Citation2015), the morality of genome modification and the moral weight of research tools (e.g. embryonic stem cell lines; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Ormond et al. Citation2017), and biosecurity (e.g. Church Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016; National Academies Citation2017). Broader ‘societal’ or public values include development of effective medical treatments (e.g. Chan et al. Citation2015; Church Citation2017; Doudna and Charpentier Citation2014; Ormond et al. Citation2017), promotion of public health (German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018), human rights (e.g. Halpern et al. Citation2019; Juengst Citation2017; Knoppers and Kleiderman Citation2019), human dignity, social solidarity, avoidance of marginalization, social justice, equity (German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018), social responsibility in innovation, and democratic control of collective action (Bovenkerk Citation2015; Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha Citation2015).

Most expert statements on HGE recognize items from multiple value repertoires, though conceptions of relations between and priorities among such values vary. For example, Church (Citation2015, Citation2017) denies that HGE interventions are qualitatively novel in causing changes in the human genome and asserts that questions of future societal risk are irrelevant, concluding that calculations of potential benefit to patients should dominate genome editing decision-making. In contrast, Bovenkerk (Citation2015) prioritizes deliberative democratic norms, asserting that meaningful social responsibility in science (1) is necessary in the case of HGE and (2) entails inclusive, participatory public dialogue on ‘the direction of whole research programs’ (68) rather than only ‘the end results and consequences of particular research’ (67). The Nuffield Council (Citation2018) emphasizes bioethics values and public values, asserting that uses of edited gametes or embryos should proceed only (1) where it is consistent with the future welfare of a person who may be produced as a result and (2) where it ‘cannot reasonably be expected to produce or exacerbate social division or the unmitigated marginalization or disadvantage of groups within society’ (xvii). In keeping with longstanding bioethics tradition, the U.S. National Academies (Citation2017) report includes nods to all three repertoires of value; but permits science values to dominate within the domain of ‘basic research’ while claiming primacy for bioethics and public values outside the lab (Hurlbut Citation2018).

As Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha (Citation2019) observe, to define ‘the stakes,’ or the risks and benefits, of HGE development and governance is to define what hopes, concerns, preferences, and values are salient and important – that is, to make fundamentally political and evaluative choices regarding the rationales and priorities which should guide research. The question of who should do so, and how, is a question of political authority. When technical experts construct risks, benefits, and principles of governance, they tend to privilege the values most salient in their personal and professional worlds – that is, science values (see, e.g. Chan et al. Citation2015; Ormond et al. Citation2017). When bioethicists do the same, they emphasize bioethics values (e.g. German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018). We should not expect that any rarefied expert group will be able to adequately represent and advocate for public values in HGE research; at best, we can point out this fact, advocate for participatory governance of research, and facilitate dialogue (cf. Bovenkerk Citation2015; Saha et al. Citation2018). Democratic governance of research is not only a normative concern, though that should be enough. As demonstrated by public outcry around, e.g. nuclear power and genetically modified foods, publics often disagree with experts about what aspects of technological development merit public input and interest. When shut out of governance arrangements, as often occurs around emerging technologies, publics will tend to mistrust governance outcomes and will seek ways to ‘break in’ (Doubleday and Wynne Citation2011; Felt and Wynne Citation2007; Jasanoff Citation2005; Wynne Citation2001). Commentators fearful of public backlash insensitive to distinctions between different forms of HGE – e.g. somatic and germline research (Adashi and Cohen Citation2015; Lanphier et al. Citation2015) – should recognize that publics will likely be more willing to recognize and invest in such distinctions if they can readily access and feel ownership over decision-making processes than if they have to force their way in.

Issue framings: what are the foci of discussion?

In HGE as elsewhere, expert issue framings tend to focus on calculable, biological, and technically controllable ‘risks’ rather than longer-range and less analytically tractable questions regarding, e.g. human rights in biomedicine, the political economy of research, or the interplay of innovation with societal inequity – indeed, to dismiss the latter as outside the proper scope of scientific concern, or irrelevant because unpredictable. The Citation2017 National Academies report on human genome editing produces strong and precise recommendations about the technical features of permissible research, but – beyond endorsement of public discussion and involvement – does not offer any recommendations as to how to ensure that research serves public goods or does not exacerbate health inequalities. The Citation2020 National Academies report on heritable human genome editing defines protocols for determining the safety and efficacy of genome editing for individual patients and their descendants, but offers no recommendations for how to prevent parents with genetic diseases from feeling pressured to modify potential children. The 2018 Nuffield Council report insists that genome editing proceed only if it will not exacerbate health inequities but does not acknowledge how flatly implausible that condition is or offer ideas on how to make it less so. Though all three reports call for public engagement, none articulates in any detail what that might mean, how it could be conducted, and how it should affect or shape research. The committees which produced these reports would rightly respond that such questions are outside the scopes of their tasks. But when no august committees regard such problems as within scope, these important issues fall by the wayside while research and application march on.

When framings tightly focused on direct biological risks and benefits to individual patients dominate discussion, questions of broad societal, economic, and political context and import often go unaddressed, or, worse, labeled as the emotional concerns of an irrational and hysterical public. Many statements from scientists and even bioethicists already presume that human genome editing (and other techniques raising similar concerns, e.g. mitochondrial replacement therapy) can and must proceed, and that public opposition can only be founded in ignorance, religious fundamentalism, fear of the unknown, or undisciplined speculation (e.g. Adashi and Cohen Citation2017; Harris Citation2015; Neuhaus and Caplan Citation2017; Spivak, Cohen, and Adashi Citation2017). Yet research advocates often appeal to equally contingent or nebulous possibilities as justification for moving forward, asymmetrically confining ‘risks’ to the realm of the technically knowable while expanding ‘benefits’ to include highly uncertain or unpredictable outcomes (Callahan Citation2015). For George Church (Citation2017, 1910), the United States must pursue heritable genome editing because it ‘may be the highest impact technology of the century’ and could ‘be a way of reducing abortions and losses of embryos’ but the only dangers worth speaking of are the biological risks to the edited individual. Even statements ostensibly acknowledging the broad societal import of HGE direct far greater scrutiny and critique toward concerns about potentially harmful outcomes than toward the promise of beneficial ones (e.g. Brokowski Citation2018).

Definitions and assessments of risk and benefit are necessarily partial, cultural, and evaluative (Douglas and Wildavsky Citation1982; Rayner and Cantor Citation1987; Weinberg Citation1972). Strict delineation between technical (imagined as substantive and collective) and ethical (often denigrated as emotional and individual) issues can arrogate primary authority for definition and evaluation of noteworthy outcomes to technical communities, while pejoratively constructing public judgments or concerns as intellectually vacuous (Hurlbut Citation2017). This understanding occludes recognition of the ‘combined intellectual-ethical’ (Wynne Citation2001, 448) character of public apprehension around many controversial technical developments. Far from mere fear of the (foreseeable or unforeseeable) outcomes of technological developments, public concerns are often rooted in mistrust of expert claims to certainty, objectivity, and control in the framing and conduct of technology assessment, and to the often explicit portrayals of public apprehension as groundless and irrational that constitute their obverse.

With these cautions in mind, it may be useful to review the issues or questions that the existing scholarly literature addresses, with a particular eye toward gaps in the discussion. Many expert statements organize around distinctions between lab research and clinical application; between somatic and germline intervention; and between enhancement and therapeutic aims, judging societal relevance, permissibility, desirability, and forms of governance differently across different combinations of these categories.

Broadly, expert statements have focused most centrally on the permissibility or desirability of classes of HGE activities, offering both categorical and conditional prescriptions or proscriptions based upon analysis from ethical principles and risk-benefit assessment. Many have emphasized the importance of public engagement with HGE research, some from normative perspectives, some from instrumental ones; though statements often leave the means through which publics might engage with HGE work and what degree of authority they might exert over it ambiguous. Expert-led prescriptions have, with some variation, held that basic research efforts can and should proceed, and that societal input should bear on clinical use; that somatic interventions should proceed, but that germline application requires public deliberation or input; and that efforts toward therapeutic applications should proceed, while enhancement applications should move forward only with public support (e.g. Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Chan et al. Citation2015; Chneiweiss et al. Citation2017; Doudna Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Krimsky Citation2019; Lander et al. Citation2019; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018; Ormond et al. Citation2017). They tend to discount bioethical concern surrounding somatic cell applications of HGE, though such uses fit squarely within the fractious history of gene therapy, with its attendant risks, costs, and inequities of development and distribution. Some statements advocate for (or against) particular governance actions – most typically, the development of procedural and reporting standards for research (e.g. Doudna Citation2015; Ormond et al. Citation2017); the possibility of a (usually, voluntary) moratorium on germline genome editing (Brokowski Citation2018; e.g. Lander et al. Citation2019; Macintosh Citation2019); the use of soft or hard governance mechanisms to constrain research (e.g. Greely Citation2019a; Guerrini et al. Citation2017; National Academies Citation2017; National Academy of Sciences Citation2020; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018); and the problems of cross-jurisdictional governance (e.g. Lander et al. Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; National Academy of Sciences Citation2020; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018).

Most expert statements issue framings and prescriptions for action, to varying degrees privileging science values as relevant in contexts of ‘basic’ research, bioethics values in the conduct of research and experiments involving human subjects, and public values in clinical application and treatment diffusion. Commentators expect expert self-governance and professional standard-setting to manage concerns relevant to basic research and take broader society to have a legitimate interest in the conduct of research only when and where that research directly affects objects ‘outside the lab,’ such as research subjects, descendants thereof, or (in response to historical public interest) human embryos (Mathews et al. Citation2015; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016; Travis 2015; Ormond et al. Citation2017; Sherkow Citation2019). Furthermore, science values are held in important ways prior to other sorts; ethical and social reckoning are held unnecessary before the technical capacity to produce particular effects (e.g. human germline modification) is present, and research is held necessary to produce risk/benefit knowledge needed to inform considerations of individual or public good (Brokowski Citation2018; Chan et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018; Ormond et al. Citation2017). Scientific and expert analysis are furthermore expected to determine what risks and benefits are novel enough to merit public consideration, and which may be safely assimilated under previous standards and regulatory regimes (Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016).

But He Jiankui's actions, alongside the history of socio-technical path dependence (Jasanoff Citation2018) and contemporary claims that germline intervention and enhancement are inevitable (e.g. Church Citation2015; Juengst Citation2017) demonstrate that work labeled as basic research often builds capacity for, investment in, and, indeed, risk of societally momentous application. Perversely, research intended to generate knowledge about whether or how to apply HGE may build scholarly, political, and commercial constituencies that close off such choices. Capacity-building basic research intended to expand understanding of genetic systems created the technological base which He Jiankui used to modify embryos. Thus, the presumption that only or primarily science values are relevant in the lab, or human safety issues in clinical trials, ignores the ways in which ‘upstream’ choices in HGE development, remanded to the judgment of invested technicians and funders, will constrain the options available ‘downstream’ where most expert statements recommend public input.

A small cadre of scholars working in science and technology studies (STS) has articulated and criticized this distribution of authority, arguing that HGE research and application cannot be neatly separated – moreover, that both raise fundamental questions about the purposes of life; relationships between persons, genes, and societies; the sorts of futures within which humans wish and should wish to live; and the sciences’ roles in defining and constructing those futures (e.g. Hurlbut Citation2015; Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha Citation2015, Citation2019). Responsibility and democracy, they assert, both demand that the aims, aspirations, and conduct of HGE activities – including whether they occur at all – should be guided by ongoing, interdisciplinary and cross-cultural dialogues regarding not only expert-defined stakes, concerns, and bases for action, but the articulation and selection thereof (Hurlbut et al. Citation2018; Saha et al. Citation2018). This discussion, they argue, should both temporally and logically precede further development or application of HGE capabilities.

Thus, the relevant questions for HGE governance not only regard the permissibility or desirability of particular forms of HGE and the ways in which judgements thereabout may be operationalized in and across different contexts. They also include little-addressed questions of authority in defining the proper aims and conduct of innovation; of resource distribution between HGE and other activities of potential public value; of the distribution of the costs, benefits, risks, and opportunities of HGE work; of institutional responsibility in case of harm or injustice; and of how to define and pursue human lives worth living.

Gaps and agendas

Discussion of HGE governance has been carried on, for the most part, in terms of boundaries to acceptable research and application. It has included comparatively little examination of the systems and institutions that actually conduct such activities, or how the structures and values of such formations can or should shape HGE development. Even discussions of genuine mechanisms for HGE governance have focused primarily upon tools and prospects for setting and enforcing limitations, rather than designing to positively guide HGE efforts with respect to broadly inclusive public interests and values (e.g. National Academies Citation2017).

There exists a vast and intensive discussion about what sorts of HGE should and should not be permitted. A smaller conversation critiques this prior discussion, arguing for broader, publicly driven governance of HGE activities, including as objects of governance the aims and aspirations of research as well as its products and conduct. There is little discussion about where HGE work should be done and decisions made – by whom, how, and under what value-ordering structures of requirements, constraints, incentives, and disincentives. There has been very limited discussion, analytic, critical, or otherwise, about how resources should be distributed within the HGE space, or between HGE and other activities with relevance to biomedicine, public health, and societal outcomes – at best, bare gestures in these directions under the umbrella of calls for broader democratic control of technoscience. Even in these statements, the practical mechanisms and pathways by which, e.g. public interests and dialogue are to affect HGE decision-making often remain unclear.

Yet systemic and institutional structures will determine, in no small part, the values, criteria of right reason, and aspirational futures recognized and pursued by HGE research (or lack or prohibition thereof) (Joly Citation2015). Genuine integration of societal needs, preferences, and interests into HGE activities will require research systems, institutions, enterprises, and practitioners whose structures, routines, and incentives respond to broadly inclusive public values. Governance or social control of HGE must not be conceived in a purely negative and limiting fashion – constructed to prevent the inappropriate and harmful – but in a positive and constructive one – aiming to promote the good and the valuable. Mere external restraints upon research, development, and economic activity are insufficient to assure broadly beneficial processes and outcomes, and they can never predict or capture the full range of potential harms or benefits which innovation processes might perpetrate. Across scales from individual researchers to national funding distribution, innovation systems and actors themselves must be constructed to care for and respond to broadly inclusive social values. In other words, there is a need to integrate considerations of societal contexts, aims, and outcomes throughout the scoping, orientation, and conduct of research and innovation, thus to improve alignment between innovation and public values.

Foresight

Foresight in anticipatory governance

The phraseology of ‘anticipatory governance’ necessarily suggests foresight activity, which may in turn suggest delusions of prophesy (Jones, Whitaker, and King Citation2011; Nordmann Citation2010; Racine et al. Citation2014; Schick Citation2017). Advocates of scientific autonomy have long asserted that research outcomes cannot be predicted (and, thus, that science cannot be guided toward or away from particular desirable or undesirable outcomes) (Bush Citation1945; Polanyi Citation1962). This argument is, for the most part, overblown. In a banal sense, research on HIV has a better chance to produce AIDS treatments than does work on gravitational waves, or, indeed, than does cancer research. In a more nuanced sense, many historical areas of strong scientific advance have developed from strategic, forward-looking choices in government or industry investment, often guided by direct use interests (Bonvillian and Van Atta Citation2011; Rosenberg Citation1994; Sarewitz and Pielke Citation2007; Stokes Citation1997). And, as the foregoing discussion implies, much of the surprise occasioned by genome editing techniques’ implications may be attributed less to their inherent unpredictability than to a collective failure to consider those implications prior to or during development of the technical capability to produce them.

Nonetheless, a much more robust set of arguments about the limits of modeling in complex systems undercuts the dream of useful prediction in all but the most artificially simplified of contexts (Funtowicz and Ravetz Citation1993; Sarewitz and Pielke Citation2000; Toulmin Citation1961). It is true that the precise outcomes of complex and contingent processes of development and diffusion, and the values and interests served or harmed thereby, cannot be strictly predicted. But this does not mean that many such factors cannot be anticipated, if by ‘anticipation’ we understand efforts to expand the breadth and depth of possibilities considered and to build broadly applicable responsive capacity, rather than to enumerate and plan for all the details of a single predicted future. In the AG framing, foresight denotes efforts to articulate and explore plural possible futures for society, and technologies’ roles therein, as means to reflect upon options in the present. Such efforts aim to build capacities of flexibility and organization to support address of unknown future challenges; to broaden the scope of foreseeable issues and responses; and to build habits of reflexivity and permit explicit consideration of the values embedded or ignored in particular ways of organizing and conducting innovation (Barben et al. Citation2008; Guston Citation2014; Selin Citation2014).

Foresight, like all forms of knowledge-making, is necessarily partial and value-laden; futuring activities are performed by particular communities for particular purposes, thus integrate their descriptive and normative presuppositions and framings on the topics of discussion. Thus, in AG, foresight efforts aim to make explicit and reflect upon their aims, framings, presuppositions, and guiding values; and to bring different stakeholder communities into pluralistic dialogue to permit interchange on possible and desired futures.

Foresight efforts on human genome editing

Thus, by ‘foresight’ we identify deliberate efforts to map out a spread of multidimensional, plausible futures as tools for anticipation, reflection, or evaluation (Konrad et al. Citation2016; Miles et al. Citation2008). Using this definition, we have not found published records of any formal foresight activities regarding human genome editing (though some foresight activities have occurred in other domains within the biosciences, e.g. Baltzegar et al. Citation2018; Borgelt, Dharamsi, and Scott Citation2013; Harvey and Salter Citation2012; and Kuzma et al. Citation2018). The futures imagined in HGE literature are rarely multidimensional, are often implausible, and do not appear to be constructed according to a rigorous scenario development methodology. Rather, explorations of futures fall into two rough categories: broad statements regarding the potentially transformational importance of HGE (e.g. Doudna and Charpentier Citation2014; Kim Citation2016; Viotti et al. Citation2019); and narrower speculations, normative arguments, and occasional predictive efforts treating – mostly in respective isolation – possibilities of interest to technical and ethical expert communities (e.g. Chan et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018). Very often, both appear in the same publication, the former as context for the latter. The literature contains no rich, integrated imaginations, but rather disconnected forays and speculations – decomposed and abstract possibilities, not plausible and inhabitable futures. These possibilities arise mostly implicitly, as authors define by inclusion or exclusion sets of issues, thus elements of potential futures, worthy of consideration. As these issues, thus possibilities, are reviewed in Section 2, we will not cover them in depth here. Rather, we will focus on the modalities through which HGE actors have articulated and related to future possibilities.

Explicitly normative statements are, by far, the most dominant mode of relationship to futures in the present literature; and most predictive statements or assumptions arise as components of normative arguments. HGE publications offer many forward-looking prescriptions on topics including:

What, if any, research or interventions should proceed (e.g. Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Baylis and McLeod Citation2017; Church Citation2017; Lander et al. Citation2019; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018)

What government should do with respect to intellectual property (Abou El-Einen et al. Citation2017; Rai and Cook-Deegan Citation2017)

By what mechanisms HGE might be governed (e.g. Guerrini et al. Citation2017; Sherkow Citation2019)

What topics should be priorities for governance or discussion (e.g. Allyse et al. Citation2015; Juengst et al. Citation2018)

What principles or frameworks should guide governance (e.g. Chan et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Juengst Citation2017; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018).

Many pre- or proscriptions are argumentatively supported by reference to expected outcomes, including, most commonly, effects on subjects of intervention (e.g. Doudna Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018); on research (e.g. Chan et al. Citation2015; Church Citation2017; Knoppers and Kleiderman Citation2019; Macintosh Citation2019; Mathews et al. Citation2015; Rai and Cook-Deegan Citation2017); on public response to genome editing (e.g. Adashi and Cohen Citation2015; Greely Citation2019a; Lanphier et al. Citation2015); and on large-scale public health, solidarity, equity, and well-being (e.g. German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018), though these last are often portrayed as unknown or unknowable. A related genre of statements explicitly forecast particular elements of possible futures, including, for example, regulatory pathways through which HGE interventions would pass (Abou-El-Enein et al. Citation2017; National Academies Citation2017; Sherkow Citation2019); the plausibility of particular applications (Greely Citation2019b; Juengst Citation2017; National Academies Citation2017); and demand for clinical HGE interventions (Viotti et al. Citation2019).

Assessment of prior foresight

All reviewed future-oriented discussions treat possibilities in isolated abstract, without considering in detail how the potentialities under consideration would fit into the contexts and contours of personal and public life and experience. Even discussions of social implications home narrowly in on, e.g. the potential for HGE uses to affect understandings of disability, shift patterns of marginalization, or worsen socioeconomic health disparities, without exploring what worlds might eventuate should one (let alone all) of these possibilities be realized. Similarly, outside of narrow discussions regarding the ability of regulatory action and public response to promote, impair, or drive underground research, future-oriented discourse contains little discussion of what external factors might shape the development of HGE knowledge and capacities. Reports and position statements (e.g. German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018; Ormond et al. Citation2017) specify that germline editing should proceed only in fashion compatible with social equity, solidarity, and justice; but do not discuss what variables, e.g. intellectual property regimes, market interests, or political developments, might affect the targeting and accessibility of HGE treatments, the distribution of costs and benefits of research, or the contribution of genetic understandings of humanity to programs of discrimination or marginalization.

The German Ethics Council's (Citation2019) approach is illustrative. It constructs three future scenarios in tightly constrained fashion, designed to permit ethical analysis of three different prospective interventions. Each envisioned future contains an anonymous, typified subject of intervention; the intervention method itself; and an unexplored, presumed social backdrop. The Council aims, through analysis of these posited futures, to determine the in-principle moral status of each prospective intervention. Yet, precisely by severing such applications from the particularities of possible contexts, the Council excludes from exploration many or most of the factors which might determine the roles they would play with respect to, e.g. distributional or procedural justice, the freedom of persons treated and persons not, and social solidarity or marginalization. Rather, the Council can simply assert that all of these things matter – in particular ways and in particular cases, presumably, for others to discuss – and conclude that it finds no categorical inviolability of the human germline. But the moral status of the human germline, considered and constructed in isolation, has little to do with how modifications therein will affect individuals’ and communities’ lives.

This is no indictment; the Council has outlined many of the dimensions of social value with which human genome editing intersects. But it – and, indeed, HGE discourse in general – has not explored those dimensions, including specific possible outcomes and determinants thereof, in depth. This absence leaves research, governance, and public actors with limited practical guide to how they might promote public values, and avoid public harms or oversights, in the governance and conduct of research and development. More deliberate, systematic, and broadly scoped foresight efforts could help HGE actors to orient, situate, and focus their efforts within the developing landscape of research, governance, and potential application. Such activities might include both deliberate scenario construction and evaluation according to a variety of extant techniques (see Bishop, Hines, and Collins Citation2007; e.g. Kuzdas and Wiek Citation2014; Wiek, Gasser, and Siegrist Citation2009) and more creative and affective methods intended to broaden the sets of persons and considerations included in futuring activities (e.g. Selin Citation2008, Citation2015). Such activities should include more detailed, inclusive, and granular discussion of the potential and proper aims, qualities, and outcomes of HGE research and implementation, including focus on what sorts of institutional and systematic arrangements could promote these outcomes and not various forms of public value failure.

Formal foresight efforts could also help to illuminate both the expert-driven ‘vanguard visions’ (Hilgartner Citation2015) of desirable or inevitable futures implicitly or explicitly animating work around HGE, including potential oversights therein and alternatives thereto. Many of the richer aims, aspirations, and imaginations running through genome editing efforts do not appear in scholarly publication, but within the minds and conversations of researchers and supporters – e.g. the magazine Wired, which has imagined ‘No hunger. No pollution. No disease. And the end of life as we know it’ (Wired Citation2015); and ‘On-demand organs. Disease-proof babies. Horn-free cows. … [A] more humane world’ (Wired Citation2019), both as outcomes of genome editing. These promises reach far beyond even the boldest claims made in scholarly literature. But they are, as often as not, exactly the sorts of dreams supporting resource allocation within the highly capitalized biotech economy (Brown Citation2003). Human longevity, as a recent and prominent example, has been medicalized in a war against the ‘diseases of aging.’ Longevity research is bolstered by futuristic claims of radically extended lifespans, increased health spans, and a 30-year fascination with bioenergetic pathways that heretofore have yielded little results (Scott and DeFrancesco Citation2015; Kostick, Folwer, and Scott Citation2019).

More sober and reflective explorations of possible futures – ones recognizing and facing up to futures’ plurality, partiality, and contingency, and not shaped as instruments to secure funding – could help to open up the decision space around HGE and to make explicit the different values promoted, supported, undercut, and excluded by different sets of aspirations and programs of action (Stirling Citation2008; compare Pielke Citation2007). Publicly oriented foresight activities could, furthermore, foster agency in non-expert communities to envision and advocate for their own conceptions of progress and for futures including their own needs and interests, as opposed to only those of biotech entrepreneurs and investors or scholarly writers and publications (cf. Withycombe Keeler, Bernstein, and Selin Citation2019).

Engagement

Engagement in anticipatory governance

By name, ‘engagement’ is perhaps the most familiar component of anticipatory governance, thanks both to a several-decade history (Stilgoe, Lock, and Wilsdon Citation2014) and to an uptick in calls for science-society engagement in response to the ostensible present crisis of public reason (Gewin Citation2017; Jasanoff and Simmet Citation2017). The term itself, however, can denote a variety of activities with a variety of different aims, ranging from placation or enrollment of recalcitrant publics to serve scientific actors’ goals (Boaz, Biri, and McKevitt Citation2016; Wynne Citation2006) to diffusion of scientific understandings and framings in public dialogue (Hurlbut Citation2017) to genuine, though limited, efforts to empower publics in scientific decision-making (e.g. Bertrand, Pirtle, and Tomblin Citation2017; Kaplan et al. Citation2019) or conduct ‘engaged research’ guided by civil society interests and needs (Cavalier and Kennedy Citation2016; Jalbert, Rubright, and Edelstein Citation2017). This range of forms and aims evokes Arnstein’s (Citation1969) ‘ladder of citizen participation’ (1) in policy planning, sweeping from nonparticipation (or manipulation) through forms of tokenism to genuine citizen power. Imaginations of public engagement with HGE fall across several of these modes; while practice has, for the most part, been much narrower.

In anticipatory governance, engagement more specifically denotes efforts to promote ‘substantive exchange of ideas among lay publics[,] and between them and those who traditionally frame[,] set the agenda for, [and] conduct scientific research’ (Guston Citation2014, 226). Examples include consensus conferences, citizens’ panels, and deliberative public debates or forums (Barben et al. Citation2008; e.g. Kaplan et al. Citation2019; Tomblin et al. Citation2017; Selin et al. Citation2017), all of which aim to elucidate the value sets, material situations, and contingent rationalities underpinning public responses to technoscientific innovation. This approach contrasts with efforts to measure aggregate public opinion on a given innovation, which offers little sense for what publics actually care about or how trajectories of development might intersect with those cares and concerns. We argue that serious efforts to respect public will or to genuinely benefit publics through technological innovation can significantly benefit from such deepened understandings.

Engagement discussion on human genome editing

Nearly every scholarly report, article, or editorial treating HGE's broad social dimensions includes at least a nod toward public engagement (e.g. German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018), but they don't necessarily agree on what that means. Views on public engagement's proper aims, forms, and relationship to research governance can vary significantly (or go missing entirely); authors discuss engagement in varying depth, understand it through multiple framings, and justify it with reference to different value sets. Engagement is frequently understood to aim toward public input to (usually, policy) decisions; though the specific mechanisms by which it might do so, and the weight it might be expected to carry, often remain unclear (Chan et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Halpern et al. Citation2019; Knoppers and Kleiderman Citation2019; Lander et al. Citation2019; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; Mathews et al. Citation2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2015; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016; Ormond et al. Citation2017; Pei et al. Citation2017; Sarewitz Citation2015; Scott and Selin Citation2019; Sharma and Scott Citation2015; Wolpe, Rommelfanger, and the Drafting and Reviewing Delegates of the BEINGS Working Groups Citation2017). Several prominent actors and publications hope that public engagement could help to inform publics about HGE methods and applications, either pursuant to public discussion support or reduction of public backlash (Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Baltimore Citation2016; Doudna Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; The Lancet Citation2017; National Academies Citation2017; Wolpe et al. Citation2017). Several publications discuss public engagement as means to gather information and improve expert and policymaker understanding of public views, values, and preferences, sometimes explicitly as decision input (Allyse et al. Citation2015; Mathews 2015; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018).

Proposed topics of public engagement frequently include the boundaries of use, most especially the acceptability of clinical HGE applications, including in vivo, ex vivo and germline approaches (Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Chan et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Greely Citation2019a; Lander et al. Citation2019; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; Mathews et al. Citation2015; The Lancet Citation2017; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2015; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018; Ormond et al. Citation2017). Frequently referenced are expectations or concerns regarding the potential broad outcomes or implications of HGE, including risks, benefits, human rights implications, and effects on disability definition and normativity (Doudna Citation2015; Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Juengst Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018; Ormond et al. Citation2017; Shakespeare Citation2015). A variety of publications (e.g. Bovenkerk Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha Citation2019; Scott and Selin Citation2019; and Wolpe Citation2017) broaden proposed discussion to include the aims and trajectories of research, while others (e.g. Allyse et al. Citation2015; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018; Sarewitz Citation2015; and Shakespeare Citation2015) shift focus to public value identification.

As discussed above, the precise methodological details of proposed engagements or engagement programs frequently remain rather vague (as in, e.g. Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Harris Citation2015; Lander et al. Citation2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2015, Citation2018; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016). Some articles propose that engagement draw upon preexisting repertoires of participatory governance practices, e.g. deliberative public forums (Bovenkerk Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Knoppers and Kleiderman Citation2019; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; Mathews et al. Citation2015; National Academies Citation2017; Ormond et al. Citation2017; Sarewitz Citation2015; Scott and Selin Citation2019). At least two (Baltimore et al. Citation2015; Lander et al. Citation2019) propose a representative global deliberation of some sort, while others (e.g. Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha Citation2019; Mathews et al. Citation2015; and Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2018) call for an expansive and inclusive deliberation without providing much detail as to what that might look like in practice.

Many calls for public engagement leave the precise relationship between public engagement, scholarly discourse, and policymaking similarly vague (e.g. Baltimore Citation2016; Doudna Citation2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2018; and Wolpe Citation2017). Such commentaries do not make clear whether deliberation and engagement are to take place prior to or in parallel to research or deployment. Other discussions, however, are more explicit; one set, including many of the most prominent statements, imagines that discourse should proceed in parallel to research and technical development, and that its results should inform decisions regarding clinical application of (most frequently, germline) editing (Baltimore et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; Greely Citation2019a; Harris Citation2015; Lander et al. Citation2019; The Lancet Citation2017; Lanphier et al. Citation2015; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2015; National Academies Citation2017; Nuffield Council on Bioethics Citation2016, Citation2018; Ormond et al. Citation2017; Pei et al. Citation2017). Another set of publications (e.g. Bovenkerk Citation2015; Jasanoff, Hurlbut, and Saha Citation2019) hold that broad societal deliberation should precede research in both a temporal and logical sense, and continue to guide it through any approved research and deployment activities.

Many calls for public engagement or discussion (e.g. Chan et al. Citation2015; German Ethics Council Citation2019; National Academies Citation2017) are phrased with reference only to germline or enhancement-oriented editing. Other commentaries maintain that publics possess a greater interest in germline than in somatic editing. This is likely because experts tend to view germline editing as more significant, more broadly impactful, and perhaps riskier than somatic editing (though significant uncertainty remains about the actual and relative risk involved in both germline and somatic interventions, and both could be significant). But these may not be the qualities most salient to public concerns; and, even if they are, they are no reason to presume the public lacks legitimate interest in the development of somatic editing capabilities. Indeed, somatic editing is subject to many of the concerns that publics have, given opportunity, raised – most especially, irresponsible use and distributive injustice (Funk and Hefferon Citation2019; Whitman et al. Citation2018).

Engagement practice on human genome editing

Unsurprisingly, calls for public engagement far outstrip actual practice. Our review found 14 scholarly publications or reports of public opinion studies relating to human genome editing published since 2015, as well as one metaanalysis of polls conducted between 1985 and 2016 (Blendon, Gorski, and Benson Citation2016). Of the former, ten (Funk and Hefferon Citation2019; Gaskell et al. Citation2017; Harvard School of Public Health & STAT Citation2016; Pew Research Center Citation2015; Pew Research Center Citation2016a; Rose et al. Citation2017; Scheufele et al. Citation2017; Weisberg, Badgio, and Chatterjee Citation2017; Whitman et al. Citation2018; Michie and Allyse Citation2019) report on large-sample surveys; two (Pew Research Center Citation2016b; Riggan, Sharp, and Allyse Citation2019) regard sets of focus groups; one (Beckman et al. Citation2019) reports on a set of interviews with a narrow target population; and one (van Mil, Hopkins, and Kinsella Citation2017) deals with a set of deliberative public workshops on genome editing, along with a follow-up national survey. Only this final item constitutes substantive ‘engagement’ as conceived under AG; but conventional public opinion studies may still inform the design of future engagements.

Across polls and focus groups, including both Blendon et al.'s coverage from 1985–2016 and our own from 2015 through the present, topics of inquiry include the acceptability of intervention, often divided into therapy vs. enhancement applications and germline vs. somatic (often glossed as ‘prenatal’ vs. ‘adult’) changes; concerns about HGE and human identity; acceptability of embryo use in research; individual outcomes for subjects of intervention; expectations regarding societal outcomes of genome editing; risk/benefit perceptions; societal support for HGE research; support for government funding of HGE research; governance preferences (tightly framed in two of three cases as choice of decision-makers); and expectations regarding whether HGE will be used responsibly. Three studies focused broadly on the acceptability of genome editing in general rather than a specific form of application (Appendix). Several studies aimed to identify demographically linked differences in public opinion regarding the aforementioned topics.

Most studies, being polls or surveys, explored these topics primarily through immediate, quantitative metrics of support or response to particular possibilities, sometimes leavened with an open, explanatory comment. van Mil, Hopkins, and Kinsella’s (Citation2017) Royal Society-commissioned deliberative workshops constitute a rather singular exception to this pattern; they dealt not only with participant responses to discrete possible applications of genome editing (including HGE applications), but the situation of genome editing and alternative interventions relative to ‘global challenges’; and the contextual framings and rationales underlying participant views, including, especially, which actors participants might trust with genome editing research.

Cross-cutting results of studies included greater public support for therapy than for enhancement applications; for ‘adult’ (somatic) than for ‘prenatal’ (germline) interventions; and for research not involving human embryos than research involving human embryos. Where analyzed, religiosity and age associated negatively, and familiarity with genome editing positively, with support for HGE; three studies found women to be less supportive of genome editing than men, and the self-identified political right to be less supportive than the left (Funk and Hefferon Citation2019; Pew Research Center Citation2015; Rose et al. Citation2017; Scheufele et al. Citation2017; Weisberg, Badgio, and Chatterjee Citation2017). When given the opportunity, respondents expressed apprehension regarding the distributional outcomes of enhancement, but expected that recipients of enhancements would experience improved quality of life (Funk and Hefferon Citation2019; Whitman et al. Citation2018). Heterogeneity in results, engaged populations, and question framings prevents strong conclusions regarding, e.g. the absolute public acceptability of any particular intervention case. Heterogeneity in publics themselves should perhaps prevent such conclusions in any case.

Being rather differently framed than most other studies, van Mil, Hopkins, and Kinsella’s (Citation2017) workshops produced a rather different set of conclusions. Across both human and non-human uses, participants desired that research and application promote and prioritize equitable access; collective welfare; knowledge extension; reduction in healthcare costs; environmental health; the alleviation of suffering; and transparency in conduct. Participants opposed development pathways which promoted homogenization, monoculture, or biodiversity loss; prioritized the development of individual or corporate wealth; expended health resources better used elsewhere; permitted weaponization of lifeforms; lacked safety monitoring; might remove persons’ options to forego genome editing interventions; might carry environmental harms, including ‘contamination’ through, presumably, cross-breeding in the environment; or were ‘too heavily’ or ‘too lightly’ regulated, though presumably definitions of both would vary. Participants tended to trust research actors displaying expertise, ethical conduct, and a beneficent orientation toward ‘real[-]world challenges’ (v); and to mistrust actors perceived as possessing profit motivations, opaque processes, insufficient oversight or regulation, a lack of speed or competence, or a lack of regard for public interest. Taken together, these data strike at broad dimensions of research organization and direction often excluded from more conventional engagement methods in favor of narrow, isolated questions regarding categorical ethical and social acceptability.

Assessment of prior engagement