Child welfare (CW) workers, who play a critical role in the delivery of services to children and families, have a fundamental right to workplace well-being and opportunities to develop their job-related capacities. According to the human development capability approach, the freedom to achieve well-being is a moral imperative; people must have the opportunity to do what is needed to achieve the kind of life they want to lead (Nussbaum, Citation2011). This approach is anchored in social justice and equity and generally applied at the societal and political levels. It is the responsibility of the individual workers to exercise this freedom to achieve their capabilities and the organization’s responsibility to provide employees with an equitable, supportive, and safe work environment (Cumming, Citation2017). Several other professional (e.g., National Association of Social Workers) and political (e.g., Service Employees International Union and the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees) organizations similarly call attention to and advocate for the professional well-being of human services workers.

However, there are currently no frameworks or best practice guidelines that consider the multiple dimensions of worker well-being within the CW context, a profession totaling around 30,000 workers in the United States (Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, Citation2020). Outside of the CW context, Danna and Griffin (Citation1999) provided an organizational framework of the antecedents and consequences of workplace well-being based on a synthesis of the general workforce literature. However, this framework includes only two dimensions of health and well-being, (i.e., mental and physical health) and as previously noted, is not specific to the CW workforce. This leaves CW organizations and leaders lacking guidance on a comprehensive approach to understanding and addressing their workforce’s well-being. The lack of a holistic worker well-being framework makes it difficult to know how to measure its absence or presence and how to create optimal work environments to ensure and support worker well-being.

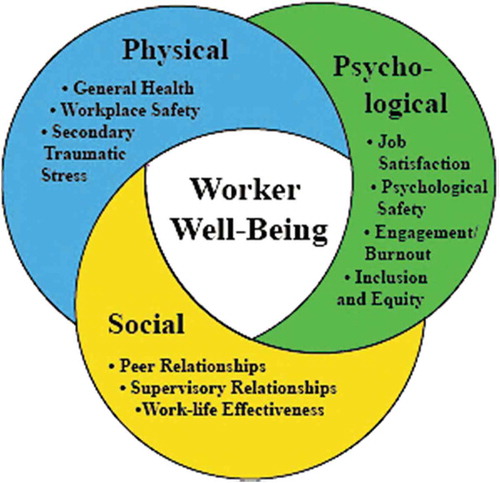

To address this gap in the literature, we developed a framework of worker well-being specific to the CW workforce and context, guided by Engel’s (Citation1978) biopsychosocial model of health and a review of the current CW workforce literature. The proposed biopsychosocial framework includes conceptual definitions for three key dimensions of worker well-being: (a) physical well-being (e.g., low secondary traumatic stress), physical safety in the workplace, and general health); (b) psychological well-being (e.g., psychological safety, job satisfaction, inclusion and equity); and (c) social well-being (e.g., peer and supervisory support, work-life effectiveness). This biopsychosocial framework takes into account that understanding well-being in the CW context requires consideration of the complexity embedded within workers’ job functions. This includes the multifaceted job demands of working with children and families with repeated experiences of trauma (Kisiel et al., Citation2014); high workload and time pressure (He, Phillips, Lizano, Rienks, & Leake, Citation2018); and regulatory, political, and bureaucratic job environments (Ellett, Ellis, Westbrook, & Dews, Citation2007). Notably, some of the same job demands and complex work conditions CW workers face are generalizable to related fields such as mental and behavioral health, nursing, and education.

We suggest that by taking a holistic view of workforce well-being, CW organizational leaders can guide efforts to support workforce well-being and stability. In addition to our biopsychosocial framework of CW worker well-being, we present a discussion of practice implications and organizational strategies that can be used to support workforce well-being.

Background

The workforce is the most valuable asset for most organizations and particularly for those in the health and human services sectors (International Labour Organization, Citation2020). As such, research focused on workforce health and well-being has gained global traction, with clinicians and researchers highlighting the need to build worker resilience, empathy, and well-being to counter the impacts of burnout and stress on health care providers (Haramati, Cotton, Padmore, Wald, & Weissinger, Citation2017). Internationally, the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2019) emphasizes that stressful and difficult work conditions have deleterious effects on workers’ health and mental health. In 2019, the WHO added job burnout to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) as an occupational phenomenon influencing the health status of workers.

Research on health and well-being in the workplace is based on the assumption that lived physical, emotional, psychological, and social experiences have an effect on workers’ health and well-being (Danna & Griffin, Citation1999). Employees’ well-being has measurable financial impacts on health insurance costs, productivity, absenteeism, and retention (Danna & Griffin, Citation1999). Similarly, CW studies have linked staff well-being indicators to retention. For example, Kim and Kao’s (Citation2014) meta-analytic study on turnover found that well-being indicators – stress, emotional exhaustion (a dimension of job burnout), and other well-being experiences (e.g., safety in the workplace) – had the strongest effect sizes related to turnover intention, more so than salary, work demands, and caseload. Vicarious or secondary trauma, another indicator of worker well-being, has also been associated with worker turnover (Middleton & Potter, Citation2015). Given the high cost of replacing and training a new CW worker due to turnover (Patel, McClure, Phillips, & Booker, Citation2017) and the moral and ethical argument that well-being is a human right (Nussbaum, Citation2011), supporting worker well-being is central to building a healthy workforce, retaining workers, and reducing the financial burden on the system.

Biopsychosocial framework of CW worker well-being

George Engel’s (Citation1978) biopsychosocial model proposed a holistic view of health and well-being involving an interplay among an individual’s physical, psychological, and social environments. Drawing from Engel’s biopsychosocial model, our workplace well-being framework includes dimensions of physical, psychological, and social (interrelationships) workplace experiences. These experiences comprise the workplace well-being of a worker (see ). This framework is not an exhaustive collection of well-being indicators nor do we posit directionality or causality between well-being dimensions. Rather, our framework presents salient well-being concepts that have been studied broadly and are relevant to the CW workforce.

Physical (bio) well-being

Physical well-being is the first dimension of our framework. Current CW literature identifies three important aspects of physical workforce well-being: general physical health, safety in the workplace, and secondary traumatic stress (STS). It should be noted that workplace safety (physical safety) and STS have elements that effect both physical and psychological well-being.

General physical health is a critical component of overall health and well-being (World Health Organization, Citation2020), but little data exists on the general physical health of the CW workforce. Limited studies have attempted to gather objective health data of CW workers (e.g., cholesterol levels, somatic physical complaints; Danna & Griffin, Citation1999; Jayaratne, Chess, & Kunkel, Citation1986), with the majority of studies relying primarily on self-report. Griffiths, Royse, and Walker (Citation2018) study indicated that CW workers “attributed fatigue, weight gain, other conditions, high blood pressure, and headaches as a result of job stress” (p. 51). However, physical health has been widely examined in related professions such as nursing and social work. A robust body of physical health research on nurses has tracked their quality of sleep, general health status, and experience of physical pain (Landa, López-Zafra, Martos, & Aguilar-Luzon, Citation2008; Lin, Liao, Chen, & Fan, Citation2014). Among social workers, general physical health (e.g., sleep disturbances, headaches, and respiratory infections; Kim, Ji, & Kao, Citation2011) has also been assessed.

Workplace safety is conceptualized as the absence of experiencing workplace violence (e.g. behaviors causing physical harm [e.g., kicking, biting] or psychological violence [e.g. verbal threats such as yelling, intimidation, threats]; Lamothe et al., Citation2018). CW workers are regularly exposed to unsafe work environments and have some of the highest risk levels of workplace violence compared to other social services fields (Kim & Hopkins, Citation2015; Newhill & Wexler, Citation1997). In their literature review of work related violence toward social workers Robson, Cossar, and Quayle’s (Citation2014) found a prevalence rate of experiences of verbal aggression ranging from 37% to 97% and reports of experiences of physical violence ranging from 2% to 34%. An evaluation of organizational health among 4,000 CW workers found that 3 in 4 indicated being shouted or sworn at by clients in the past 6 months and 1 in 3 reported being threatened by clients (He, Grenier, & Bell, Citation2020). These experiences contribute to feelings of distress, hypervigilance, or irritation among CW workers (Lamothe et al., Citation2018; Robson et al., Citation2014). Concerns about personal safety on the job also impact workers’ commitment to the organization (Kim & Hopkins, Citation2015). Feelings of workplace safety could lead to a positive state of worker well-being. One study found that CW staff members who perceived that their agency had higher levels of commitment to safety reported lower levels of emotional exhaustion (Vogus, Cull, Hengelbrok, Modell, & Epstein, Citation2016).

Secondary traumatic stress is categorized under physical well-being in our framework due to its associated physiological responses (Figley, Citation1995). STS is described as emotions and behaviors that result from knowing about a traumatic event experienced by another and having a desire to help the traumatized person (Figley, Citation1995; Sprang, Ford, Kerig, & Bride, Citation2019). Symptoms can include avoidance of reminders of the event, feeling numb when reminded of the event, persistent arousal, trouble sleeping and concentrating, heightened startle responses, and other physiological responses (Figley, Citation1995; Sprang et al., Citation2019). In CW, STS is considered a potential byproduct of working with clients who have experienced traumatization (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Citationn.d.). While no concrete rates of STS among CW workers in the U.S. exist, a report of workforce health found that, among 2,000 CW caseworkers, almost half met the threshold for STS, indicating they experienced PTSD-level symptoms related to STS (He et al., Citation2020). Further, higher levels of STS among CW workers have been correlated with a greater likelihood of leaving the workplace (Bride, Jones, & MacMaster, Citation2007).

Psychological well-being

Psychological and affective well-being is the second dimension of our conceptual framework and focuses on job satisfaction, psychological safety, job stress, job burnout, and workplace inclusion. Given that most employed adults spend almost nine hours a day working (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Citation2019), work is a central part of an individual’s life, providing income and a sense of purpose and satisfaction (Warr, Citation1999). Work can also have a direct impact on workers’ mental health and can contribute to harmful affectivity if work experiences are negative (Warr, Citation1999).

Job satisfaction, a “positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences” (Locke, Citation1976, p. 1300), is a critical component of workers’ psychological well-being (Spector, Citation1997; Warr, Citation1990) that can spill over and affect other domains in life including life satisfaction and overall happiness (Bowling, Eschleman, & Wang, Citation2010). National job satisfaction rates among CW workers are unknown, but studies by Barth, Lloyd, Christ, Chapman, and Dickinson (Citation2008) and He et al. (Citation2020) suggested that CW workers are between “undecided” and “somewhat satisfied with their jobs.” Job satisfaction also has organizational implications, with research indicating that job satisfaction affects workers’ organizational commitment (Landsman, Citation2008) and retention (DePanfilis & Zlotnik, Citation2008; Mor Barak, Levin, Nissly, & Lane, Citation2006).

Psychological safety has been widely studied in business literature (Frazier, Fainshmidt, Klinger, Pezeshkan, & Vracheva, Citation2017) and more recently in CW. Psychological safety influences internal work motivations and is defined as the “feeling of being able to show and employ one’s self without fear of negative consequences to self-image, status, or career” (Kahn, Citation1990, p. 708). Workers experience psychological safety when they trust they will not suffer negative consequences if they make a mistake or fail to meet work outcomes (Kahn, Citation1990) and perceive that their agency demonstrates a commitment to identifying systemic causes of failure rather than seeking to assign blame to workers (Cull, Rzepnicki, O’Day, & Epstein, Citation2013). Psychological safety also includes team psychological safety, which depends on interpersonal exchanges among individuals at work and is defined as “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking” (Edmondson, Citation1999, p. 354). Psychological safety has key organizational implications, including greater engagement at work, creativity, and innovation (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014). In CW-specific studies, psychological safety has been found to relate to lower levels of emotional exhaustion (Vogus et al., Citation2016), a higher likelihood of staying on the job (Kruzich, Mienko, & Courtney, Citation2014), and lower reports of moral distress (He, Lizano, & Stahlschmidt, Citation2021).

Job burnout and work engagement are closely related concepts of psychological well-being (Leiter & Maslach, Citation2017). Job burnout has been studied widely both in and outside the CW field and is commonly defined as feelings of emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and lowered feelings of personal accomplishment (self-efficacy) that result from chronic stress (Maslach, Schaufeli, & Leiter, Citation2001). Job burnout research suggests that CW workers might experience higher levels of job burnout than those in other fields. In a study of social workers in California, Kim (Citation2011) found that those employed in the public CW field reported higher levels of depersonalization (i.e., cynicism) and lower levels of personal accomplishment (i.e., self-efficacy) than those in other settings. Similarly, in a national study of helping professionals, Sprang, Craig, and Clark (Citation2011) found CW workers had higher rates of job burnout when compared to their counterparts in the study. Job burnout has been associated with greater turnover (Kim & Kao, Citation2014; Strolin, McCarthy, & Caringi, Citation2006) and emotional exhaustion among CW workers (a dimension of job burnout), which in turn has contributed to less positive outcomes for children who are served by those workers (Glisson & Green, Citation2011).

Work engagement research developed in response to job burnout research and is defined as “a positive, fulfilling, affective-motivational state of work-related well-being that can be seen as the antipode of job burnout” (Leiter & Bakker, Citation2010, p. 1). Work engagement has three domains: vigor, dedication, and absorption (Bakker, Schaufeli, Leiter, & Taris, Citation2008). Previous research provides evidence that work engagement and job burnout are negatively related and are independent and separate constructs (Goering, Shimazu, Zhou, Wada, & Sakai, Citation2017). For example, Fragoso et al.’s (Citation2016) study of health care workers found that burnout and engagement were negatively correlated and differentially related to health and motivational outcomes; burnout also had a greater influence on overall worker health, whereas engagement had a greater impact on worker commitment.

To our knowledge, no previous research has been published on work engagement among CW workers, and there is one study examining work disengagement in this profession. In a three-wave longitudinal study of CW workers, Travis, Lizano, and Mor Barak (Citation2016) examined several antecedents (e.g., job stressors and job burnout) of work disengagement, which the authors defined as work withdrawal and exit-seeking behaviors. Although they operationalized work engagement differently than the previously noted conceptual definition (i.e., vigor, dedication, and absorption), their study findings suggested that greater job burnout leads to greater work disengagement.

Inclusion in the workplace is defined as a worker’s feelings of being part of both formal and informal organizational processes (Mor Barak, Citation2011). Inclusion literature builds on diversity in the workplace and focuses on how included workers feel in their organizations (Mor Barak, Citation2011). In their meta-analytic study of human service workers, Mor Barak et al. (Citation2016) included two articles that measured inclusion (incidentally, both used CW samples). These studies found that inclusion led to positive organizational outcomes, including greater job engagement and intent to stay (see Hwang & Hopkins, Citation2012; Travis & Mor Barak, Citation2010). Kim and Kao (Citation2014) meta-analytic study of CW workers found that perceptions of fairness in the workplace (e.g., pay, benefits, promotions) also correlated with intention to stay.

Efforts to capture workplace inclusion and equity indicators also include their counterpart, workplace discrimination. Workplace discrimination is the “prejudicial treatment of an individual based on membership of a certain group or category” (Wood, Braeken, & Niven, Citation2013, p. 617) and results in prejudice and exclusion (Ali, Yamada, & Mahmood, Citation2015). Workplace discrimination can be viewed as the opposite of inclusion and equity and a work stressor that negatively affects worker well-being (Wood et al., Citation2013). Outside of CW literature, a strong body of literature has examined the relationship between workplace discrimination and worker well-being in various professions (e.g., mental health, occupational health; Hammond, Gillen, & Yen, Citation2010; Xu & Chopik, Citation2020) and identities (e.g., gender, race, sexual orientation, religion; Ali et al., Citation2015). Studies indicate that workplace discrimination has a deleterious impact on psychological well-being, including mental health, job satisfaction, and burnout (Wood et al., Citation2013).

Social well-being

The third dimension of our CW workplace well-being framework is social well-being. Classic theories by Freud (Citation1930) and Erikson (Citation1950) explained the centrality of social relationships in people’s everyday life and well-being. Their work has been applied to research on social well-being in the workplace, which generally focuses on socially supportive relationships and interactions between workers (Araújo & Pestana, Citation2017; Stansfeld, Shipley, Head, Fuhrer, & Kivimaki, Citation2013). We include social support in the workplace and work-life effectiveness in our social well-being dimension.

Social support is one of the most important qualities of a relationship (House, Umberson, & Landis, Citation1988) and has the capacity to be “health promoting or stress-buffering” (p. 302). Research points to how important healthy and supportive working relationships with peers and supervisors are to CW workers’ well-being (DePanfilis & Zlotnik, Citation2008; Kim & Kao, Citation2014; McFadden, Campbell, & Taylor, Citation2015). Greater levels of peer support are positively associated with job satisfaction and intention to stay on the job (Johnco, Salloum, Olson, & Edwards, Citation2014; Sedivy, Rienks, Leake, & He, Citation2020). Supervisor support has also been widely examined in CW research (Kim & Kao, Citation2014; Lietz & Julien-Chinn, Citation2017). Findings associated higher satisfaction and supportive relationships with supervisors to job satisfaction and retention (Griffiths & Royse, Citation2017; Lietz & Julien-Chinn, Citation2017).

Work–life effectiveness, which entails the effective management of work and personal life (Gornick & Blair, Citation2005; Koppes & Swanberg, Citation2008), is included in the social dimension of our well-being framework. Work–life effectiveness is a holistic view of worker well-being and requires an acknowledgment of the worker as a whole person with personal responsibilities and life experiences outside of work. Workers experience work–life conflict when work demands interfere with their personal life responsibilities, negatively affecting their well-being (Kossek & Lee, Citation2017). There are different schools of thought on the relative benefits of work-life balance (separately managing work and personal obligations) versus work-life integration (strategies that bring work and personal life closer together) as means of greater work-life effectiveness. However, in their review of their research on work-life effectiveness, Williams, Berdahl, and Vandello (Citation2016) argued that the concept of work-life integration is based on class-based assumptions that people desire to have work be salient and ever-present in their lives. There is not enough research in human services to address this debate, and, in fields that require intensive work with families impacted by complex trauma, the ability to separate work and home life might be considered an important and adaptive coping strategy.

In organizations, work–life effectiveness could mean the implementation of practices and policies that are responsive to the work–life needs of employees (Koppes & Swanberg, Citation2008), including assisting workers in managing their time (e.g., flexible scheduling), providing resources for work–life demands (e.g., childcare options in the community), providing financial assistance (e.g., tuition reimbursement), and offering direct services to the worker (e.g., on-site medical services, fitness facility; Koppes, Citation2008). Although work–life effectiveness has been minimally studied in CW, evidence from previous research points to work–family conflict as a challenge in the profession. Studies of work–family conflict in CW have linked it to job burnout (Lizano, Hsiao, Mor Barak, & Casper, Citation2014) and intentions to leave the job (DePanfilis & Zlotnik, Citation2008). Given that most CW workers are women (Dolan, Smith, Casanueva, & Ringe, Citation2011; He et al., Citation2020) and that women disproportionately carry the burden of caregiving (Swinkels, Tilburg, Verbakel, & Broese Van Groenou, Citation2019), providing avenues for work–life effectiveness could have a positive impact on the social well-being of this workforce.

Practice implications

Although many studies attest to how the health and well-being of CW workers are instrumental to the healthy functioning of CW agencies (Casanueva, Horn, Smith, Dolan, & Ringeisen, Citation2011; Kim & Kao, Citation2014), CW organizations vary in their ability to create and support a strong and healthy workforce. CW organizations perennially struggle with high turnover rates and the accompanying cost of turnover. Their response is to focus resources on recruitment of new staff members.

We propose that creating an organizational climate that comprehensively supports worker well-being could be pivotal for supporting worker retention. Therefore, we propose that this holistic CW worker well-being framework needs to be considered when assessing, designing, and implementing organizational practices and policies geared toward improving well-being. Efforts to promote CW worker well-being must begin with an understanding and consideration of the unique and complex demands of the job, as well as the state and federal regulatory environment that oversees CW (Ellett et al., Citation2007; He et al., Citation2018).

Additionally, in our review of the literature, we found that efforts made by CW agencies to address well-being often focused on modifying the thoughts, behaviors, and actions of employees to be more resilient to stress and cope better with time pressure rather than changing the conditions of the organization to provide better resources and supports (Cummings, Singer, Moody, & Benuto, Citation2020; McFadden et al., Citation2015). However, workforce well-being is the mutual responsibility of the employee and the organization (Dickson-Swift, Fox, Marshall, Welch, & Willis, Citation2014). Organizational structures need to create supportive and equitable work environments in which CW workers are empowered to perform to their highest ability and gain skills for self-care and resilience practices. Therefore, we provide a list of strategies that CW organizations could implement to support their workforce’s well-being across the three well-being dimensions in our framework (see ).

Table 1.. Organizational strategies to support CW workforce well-being

Further, CW organizations need to conduct ongoing assessments and data collection that is inclusive of all the worker well-being dimensions. While some CW organizations expend a great deal of time and resources on organizational assessment and workforce development strategies, many more are under-resourced and do not prioritize workforce development or well-being. A multi-dimensional assessment will provide a more accurate perspective of worker well-being, and CW agencies’ efforts to develop and support their workforce can be further bolstered by considering the biopsychosocial dimensions of worker well-being. This framework is an addition to a robust body of literature on workforce development, but despite this proliferation of research studies, there remains a large science-to-service gap. Notably, many CW agencies struggle to develop and implement sustainable strategies to improve workforce well-being (Huffman, Citation2020), with some agencies addressing certain aspects of worker well-being while not attending to others. For example, an agency may choose to focus on addressing STS, which is ubiquitously high among CW workers, but fail to address other key well-being indicators such as psychological safety, workplace inclusion, and racial equity. Hence, while we do not operationalize or provide measures for each well-being dimension, this framework does provide a foundation for conducting a holistic assessment and identifying a range of implementable strategies to address the physical, psychological, and social dimensions of CW worker well-being.

Organizational leaders can use this framework to plan for and implement assessments tailored to their agency context to capture and evaluate worker well-being and develop targeted organization-level changes that address well-being gaps. Existing CW organizational health assessment tools and resources are available (see Gagnon, Paquet, Courcy, & Parker, Citation2009; Glisson, Citation2007). Further, the National Child Welfare Workforce Institute (NCWWI, Citation2021) and the Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development (Citation2020) are both federally funded centers that produce and compile resources focused on CW workforce health and well-being. Our biopsychosocial framework for CW worker well-being can be used in conjunction with the NCWWI Workforce Development Framework (National Child Welfare Workforce Institute, Citation2019). The Workforce Development Framework describes critical elements of an effective workforce, including supervision, community engagement, and recruitment and selection of staff, as well as an implementation process for identifying and addressing overall workforce gaps.

It should be noted that our biopsychosocial framework is intended for public and private CW organizations and reflects a Western perspective of well-being that may not capture nondominant cultural views of well-being. Therefore, when working with tribal CW programs that primarily have American Indian or Alaska Native and Indigenous staff, this framework should be applied alongside well-being frameworks and models that are grounded in traditional and community values, beliefs, and cultural norms. For example, many American Indian people hold a relational worldview that features the medicine wheel; the medicine wheel is often used as a framework to illustrate the importance of alignment, balance, and interconnectivity of the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual connections to the natural world (Cross, Citation1997). Additionally, the Seven Grandfather Teachings are used by many American Indian people; they offer instructions for living in balance and achieving well-being and include core elements such as wisdom, love, respect, honesty, humility, truth, and bravery (Ontario Native Literacy Coalition Social Community Enterprise, Citation2012). We need to explore and expand our biopsychosocial worker well-being framework to include other cultural, spiritual, and Indigenous concepts of well-being. Still, adapting this biopsychosocial well-being framework may allow other similar human services organizations, such as mental health, substance treatment, early education, and social work fields, to apply and use the framework.

Conclusion

The biopsychosocial framework for CW worker well-being has the potential to contribute to the development of evidence-based prevention and intervention practices that address CW workforce needs (e.g., burnout, turnover). Moreover, CW work is deeply rooted in social work practice and the inherent values of social justice and equity that are the foundation of social work. In accordance with these values, Nussbaum (Citation2011) contended that there is a moral argument to be made for systems to work to preserve human dignity and the freedom to pursue well-being. Hence, CW workers have a right to a high-quality work environment in which they can thrive, not just because it will reduce the cost of turnover or ensure better outcomes for children and families, but because it is a moral and ethical imperative (Cumming, Citation2017). Only by becoming organizations that care for the well-being of the workforce primarily because we value the human beings in our organizations and believe in their rights can we truly commit to preserving the inherent rights of families that interact with the CW system.

References

- Administration on Children, Youth, and Families. (2020). Child maltreatment 2018. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment

- Ali, S. R., Yamada, T., & Mahmood, A. (2015). Relationships of the practice of hijab, workplace discrimination, social class, job stress, and job satisfaction among Muslim American women. Journal of Employment Counseling, 52(4), 146–157. doi:10.1002/joec.12020

- Araújo, J., & Pestana, G. (2017). A framework for social well-being and skills management at the workplace. International Journal of Information Management, 37(6), 718–725. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.07.009

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Taris, T. W. (2008). Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work and Stress, 22(3), 187–200. doi:10.1080/02678370802393649

- Barth, R. P., Lloyd, C. E., Christ, S. L., Chapman, M. V., & Dickinson, N. S. (2008). Child welfare worker characteristics and job satisfaction: A national study. Social Work, 53(3), 199–209. doi:10.1093/sw/53.3.199

- Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., & Wang, Q. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83(4), 915–934. doi:10.1348/096317909X478557

- Bride, B. E., Jones, J. L., & MacMaster, S. A. (2007). Correlates of secondary traumatic stress in child protective services workers. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 4(3–4), 69–80. doi:10.1300/J394v04n03_05

- Casanueva, C., Horn, B., Smith, K., Dolan, M., & Ringeisen, H. (2011). NSCAW II baseline report: Local agency (ORPE Report # 2011–27). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- Cross, T. (1997). Relational worldview model. Pathways Practice Digest, 12(4). Retrieved from https://www.sprc.org/sites/default/files/resource-program/Relational-Worldview-Model.pdf

- Cull, M. J., Rzepnicki, T. L., O’Day, K., & Epstein, R. A. (2013). Applying principles from safety science to improve child protection. Child Welfare, 92(2), 179–195. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24199329/

- Cumming, T. (2017). Early childhood educators’ well-being: An updated review of the literature. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(5), 583–593. doi:10.1007/s10643-016-0818-6

- Cummings, C., Singer, J., Moody, S. A., & Benuto, L. T. (2020). Coping and work-related stress reactions in protective services workers. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(1), 62–80. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcz082

- Danna, K., & Griffin, R. W. (1999). Health and well-being in the workplace: A review and synthesis of the literature. Journal of Management, 25(3), 357–384. doi:10.1177/014920639902500305

- DePanfilis, D., & Zlotnik, J. L. (2008). Retention of front-line staff in child welfare: A systematic review of research. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(9), 995–1008. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.017

- Dickson-Swift, V., Fox, C., Marshall, K., Welch, N., & Willis, J. (2014). What really improves employee health and well-being. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 7(3), 138–155. doi:10.1108/IJWHM-10-2012-0026

- Dolan, M., Smith, K., Casanueva, C., & Ringe, H. (2011). NSCAW II baseline report: Caseworker characteristics, child welfare services, and experiences of children placed in out-of-home care (No. OPRE Report #2011-27e). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/nscaw2_cw.pdf

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. doi:10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 23–43. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Ellett, A. J., Ellis, J. I., Westbrook, T. M., & Dews, D. (2007). A qualitative study of 369 child welfare professionals’ perspectives about factors contributing to employee retention and turnover. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(2), 264–281. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.07.005

- Engel, G. L. (1978). The biopsychosocial model and the education of health professionals. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 310(1), 169–181. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb22070.x

- Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

- Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary stress disorder in those who treat the traumatised (pp. 1–20). New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Fragoso, Z. L., Holcombe, K. J., McCluney, C. L., Fisher, G. G., McGonagle, A. K., & Friebe, S. J. (2016). Burnout and engagement: Relative importance of predictors and outcomes in two health care worker samples. Workplace Health & Safety, 64(10), 479–487. doi:10.1177/2165079916653414

- Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta‐analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. doi:10.1111/peps.12183

- Freud, S. (1930). Civilisation and its discontents. Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag Wien. London: Penguin.

- Gagnon, S., Paquet, M., Courcy, F., & Parker, C. (2009). Measurement and management of work climate: Cross-validation of the CRISO Psychological Climate Questionnaire. Healthcare Management Forum, 22(1), 57–65. doi:10.1016/S0840-4704(10)60294-3

- Glisson, C. (2007). Assessing and changing organizational culture and climate for effective services. Research on Social Work Practice, 17(6), 736–747. doi:10.1177/1049731507301659

- Glisson, C., & Green, P. (2011). Organizational climate, services, and outcomes in child welfare systems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(8), 582–591. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.04.009

- Goering, D. D., Shimazu, A., Zhou, F., Wada, T., & Sakai, R. (2017). Not if, but how they differ: A meta-analytic test of the nomological networks of burnout and engagement. Burnout Research, 5, 21–34. doi:10.1016/j.burn.2017.05.003

- Gornick, M. E., & Blair, B. R. (2005). Employee assistance, work-life effectiveness, and health and productivity: A conceptual framework for integration. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 20(1–2), 1–29. doi:10.1300/J490v20n01_01

- Griffiths, A., & Royse, D. (2017). Unheard voices: Why former child welfare workers left their positions. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(1), 73–90. doi:10.1080/15548732.2016.1232210

- Griffiths, A., Royse, D., & Walker, R. (2018). Stress among child protective service workers: Self-reported health consequences. Children and Youth Services Review, 90, 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.05.011

- Hammond, W. P., Gillen, M., & Yen, I. H. (2010). Workplace discrimination and depressive symptoms: A study of multi-ethnic hospital employees. Race and Social Problems, 2(1), 19–30. doi:10.1007/s12552-010-9024-0

- Haramati, A., Cotton, S., Padmore, J. S., Wald, H. S., & Weissinger, P. A. (2017). Strategies to promote resilience, empathy and well-being in the health professions: Insights from the 2015 CENTILE conference. Medical Teacher, 39(2), 118–119. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1279278

- He, A. S., Grenier, A., & Bell, K. (2020). Comprehensive organizational health assessment public Workforce Excellence Sites: Cross-site summary report: September 2020. Albany: National Child Welfare Workforce Institute.

- He, A. S., Lizano, E. L., & Stahlschmidt, M. J. (2021). When doing the right thing feels wrong: Moral distress among child welfare caseworkers. Children and Youth Services Review, 122, 105914. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105914

- He, A. S., Phillips, J. D., Lizano, E. L., Rienks, S., & Leake, R. (2018). Examining internal and external job resources in child welfare: Protecting against caseworker burnout. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 48–59. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.013

- House, J. S., Umberson, D., & Landis, K. R. (1988). Structures and processes of social support. Annual Review of Sociology, 14, 293–318. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.14.080188.001453

- Huffman, R. (2020). Thinking out of the box. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(1), 5–18. doi:10.1080/15548732.2020.1690186

- Hwang, J., & Hopkins, K. (2012). Organizational inclusion, commitment, and turnover among child welfare workers: A multilevel mediation analysis. Administration in Social Work, 36(1), 23–39. doi:10.1080/03643107.2010.537439

- International Labour Organization. (2020). Workplace well-being. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety–and–health–at–work/areasofwork/workplace–health–promotion–and–well–being/WCMS_118396/lang–en/index.htm

- Jayaratne, S., Chess, W. A., & Kunkel, D. A. (1986). Burnout: Its impact on workers and their spouses. Social Work, 31(1), 53–59. doi:10.1093/sw/31.1.53

- Johnco, C., Salloum, A., Olson, K. R., & Edwards, L. M. (2014). Child welfare workers’ perspectives on contributing factors to retention and turnover: Recommendations for improvement. Children and Youth Services Review, 47(3), 397–407. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.10.016

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. doi:10.2307/256287

- Kim, H. (2011). Job conditions, unmet expectations, and burnout in public child welfare workers: How different from other social workers?. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(2), 358–367. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.10.001

- Kim, H., & Hopkins, K. M. (2015). Child welfare workers’ personal safety concerns and organizational commitment: The moderating role of social support. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 39(2), 101–115. doi:10.1080/23303131.2014.987413

- Kim, H., Ji, J., & Kao, D. (2011). Burnout and physical health among social workers: A three-year longitudinal study. Social Work, 56(3), 258–268. doi:10.1093/sw/56.3.258

- Kim, H., & Kao, D. (2014). A meta-analysis of turnover intention predictors among US child welfare workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 214–223. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.015

- Kisiel, C. L., Fehrenbach, T., Torgersen, E., Stolbach, B., McClelland, G., Griffin, G., & Burkman, K. (2014). Constellations of interpersonal trauma and symptoms in child welfare: Implications for a developmental trauma framework. Journal of Family Violence, 29(1), 1–14. doi:10.1007/s10896-014-9603-8

- Koppes, L. L. (2008). Facilitating an organization to embrace a work–life effectiveness culture: A practical approach. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 11(1), 163–184. doi:10.1080/10887150801967712

- Koppes, L. L., & Swanberg, J. (2008). Introduction to special issue: Work-life effectiveness: Implications for organizations. The Psychologist Manager Journal, 11(1), 1–4. doi:10.1080/10887150801963760.

- Kossek, E. E., & Lee, K. H. (2017). Work-family conflict and work-life conflict. In Oxford research encyclopedia of business and management. https://oxfordre.com/business/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190224851.001.0001/acrefore-9780190224851-e-52

- Kruzich, J. M., Mienko, J. A., & Courtney, M. E. (2014). Individual and work group influences on turnover intention among public child welfare workers: The effects of work group psychological safety. Children and Youth Services Review, 42, 20–27. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.005

- Lamothe, J., Couvrette, A., Lebrun, G., Yale-Soulière, G., Roy, C., Guay, S., & Geoffrion, S. (2018). Violence against child protection workers: A study of workers’ experiences, attributions, and coping strategies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 81, 308–321. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.04.027

- Landa, J. M. A., López-Zafra, E., Martos, M. P. B., & Aguilar-Luzon, M. D. C. (2008). The relationship between emotional intelligence, occupational stress and health in nurses: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(6), 888–901. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.03.005

- Landsman, M. J. (2008). Pathways to organizational commitment. Administration in Social Work, 32(2), 105–132. doi:10.1300/J147v32n02_07

- Leiter, M. P., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Work engagement: Introduction. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 1–9). Psychology Press.

- Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2017). Burnout and engagement: Contributions to a new vision. Burnout Research, 5, 55–57. doi:10.1016/j.burn.2017.04.003

- Lietz, C. A., & Julien-Chinn, F. J. (2017). Do the components of strengths-based supervision enhance child welfare workers’ satisfaction with supervision?. Families in Society, 98(2), 146–155. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.2017.98.20

- Lin, S. H., Liao, W. C., Chen, M. Y., & Fan, J. Y. (2014). The impact of shift work on nurses’ job stress, sleep quality and self‐perceived health status. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(5), 604–612. doi:10.1111/jonm.12020

- Lizano, E. L., Hsiao, H. Y., Mor Barak, M. E., & Casper, L. M. (2014). Support in the workplace: Buffering the deleterious effects of work–family conflict on child welfare workers’ well-being and job burnout. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(2), 178–188. doi:10.1080/01488376.2013.875093

- Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). New York: Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- McFadden, P., Campbell, A., & Taylor, B. (2015). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. The British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1546–1563. doi:10.1080/09503153.2019.1620201

- Middleton, J. S., & Potter, C. C. (2015). Relationship between vicarious traumatization and turnover among child welfare professionals. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(2), 195–216. doi:10.1080/15548732.2015.1021987

- Mor Barak, M. E. (2011). Managing diversity: Toward a globally inclusive workplace (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Mor Barak, M. E., Levin, A., Nissly, J. A., & Lane, C. J. (2006). Why do they leave? Modeling child welfare workers’ turnover intentions. Children and Youth Services Review, 28(5), 548–577. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.06.003

- Mor Barak, M. E., Lizano, E. L., Kim, A., Duan, L., Rhee, M. K., Hsiao, H. Y., & Brimhall, K. C. (2016). The promise of diversity management for climate of inclusion: A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 40(4), 305–333. doi:10.1080/23303131.2016.1138915

- National Child Welfare Workforce Institute. (2019). The workforce development framework. Retrieved from https://ncwwi.org/files/Workforce_Development_Framework_Brief.pdf

- National Child Welfare Workforce Institute. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.ncwwi.org/

- Newhill, C. E., & Wexler, S. (1997). Client violence toward children and youth services social workers. Children and Youth Services Review, 19(3), 195–212. doi:10.1016/S0190-7409(97)00014-5

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Harvard University Press.

- Ontario Native Literacy Coalition Social Community Enterprise. (2012). Seven Grandfather Teachings. Retrieved from http://www.7grandfatherteachings.ca/teachings.html

- Patel, D., McClure, M., Phillips, S., & Booker, D. (2017). Child protective services workforce analysis and recommendations. Retrieved from https://www.texprotects.org/media/uploads/improving_the_protection_of_texas_children_workforce_analysis._january_2017_final_release.pdf

- Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.qic-wd.org/

- Robson, A., Cossar, J., & Quayle, E. (2014). Critical commentary: The impact of work-related violence towards social workers in children and family services. The British Journal of Social Work, 44(4), 924–936. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu015

- Sedivy, J. A., Rienks, S., Leake, R., & He, A. S. (2020). Expanding our understanding of the role of peer support in child welfare workforce retention. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 14(1), 80–100. doi:10.1080/15548732.2019.1658020.

- Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Sprang, G., Craig, C., & Clark, J. (2011). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in CW workers: A comparative analysis of occupational distress across professional groups. Child Welfare, 90(6), 149–168. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22533047/

- Sprang, G., Ford, J., Kerig, P., & Bride, B. (2019). Defining secondary traumatic stress and developing targeted assessments and interventions: Lessons learned from research and leading experts. Traumatology, 25(2), 72–81. doi:10.1037/trm0000180

- Stansfeld, S. A., Shipley, M. J., Head, J., Fuhrer, R., & Kivimaki, M. (2013). Work characteristics and personal social support as determinants of subjective well-being. PLoS One, 8(11), e81115. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0081115

- Strolin, J. S., McCarthy, M., & Caringi, J. (2006). Causes and effects of child welfare workforce turnover: Current state of knowledge and future directions. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 1(2), 29–52. doi:10.1300/J479v01n02_03

- Swinkels, J., Tilburg, T. V., Verbakel, E., & Broese Van Groenou, M. (2019). Explaining the gender gap in the caregiving burden of partner caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(2), 309–317. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx036

- Travis, D. J., Lizano, E. L., & Mor Barak, M. E. (2016). ‘I’m so stressed!’: A longitudinal model of stress, burnout and engagement among social workers in child welfare settings. The British Journal of Social Work, 46(4), 1076–1095. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct205

- Travis, D. J., & Mor Barak, M. E. (2010). Fight or flight? Factors influencing child welfare workers’ propensity to seek positive change or disengage from their jobs. Journal of Social Service Research, 36(3), 188–205. doi:10.1080/01488371003697905

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Charts from the American Time Use Survey. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/charts/american-time-use/emp-by-ftpt-job-edu-h.htm

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (n.d.). Secondary traumatic stress. What is secondary traumatic stress? Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/trauma-toolkit/secondary-traumatic-stress

- Vogus, T. J., Cull, M. J., Hengelbrok, N. E., Modell, S. J., & Epstein, R. A. (2016). Assessing safety culture in child welfare: Evidence from Tennessee. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 94–103. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.020

- Warr, P. (1990). The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(3), 193–210. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00521.x

- Warr, P. (1999). Well-being and the workplace. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 392–412). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Williams, J. C., Berdahl, J. L., & Vandello, J. A. (2016). Beyond work-life “integration.”. Annual Review of Psychology, (67), 515–539. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033710

- Wood, S., Braeken, J., & Niven, K. (2013). Discrimination and well-being in organizations: Testing the differential power and organizational justice theories of workplace aggression. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(3), 617–634. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1404-5

- World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

- World Health Organization. (2020). Occupational health: Stress at the workplace. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/occupational_health/topics/stressatwp/en/

- Xu, Y. E., & Chopik, W. J. (2020). Identifying moderators in the link between workplace discrimination and health/well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 458. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00458