ABSTRACT

Through four qualitative case studies, we explore how smaller nonprofit human service organizations (SNHSOs) in England and Wales responded to the COVID-19 pandemic and consider the implications for state-nonprofit relations. SNHSOs pandemic response was immediate, dynamic, flexible, and adaptive in response to urgent needs. They supported communities most severely affected by the pandemic due to factors such as health, economic status, geography race, and ethnicity. Whereas several theories of state-nonprofit relations position the relationship as relatively settled at an organizational level, we argue for greater attention to how these relationships can be fluid, dynamic, and subject to change over time.

PRACTICE POINTS

During times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, smaller nonprofits are typically first responders to urgent needs, but larger public sector organizations are likely to play a more central role as time progresses.

Smallness confers limited organizational hierarchy and minimal bureaucracy, which enables smaller nonprofits to respond dynamically and flexibly during crises to meet urgent and developing needs. Larger, more bureaucratic and hierarchical organizations take longer to respond to crises and can be less flexible due to their size.

Smaller nonprofits often work with people who were most severely and acutely affected by crises due to factors such as health, economic status, geographic location, race, and ethnicity. These groups tend to be less well-served by mainstream human services provided by public sector bodies and larger nonprofits.

Partnership and collaboration between smaller and large nonprofits and public bodies, that maximizes the strengths of each and mitigates their weaknesses, is vital for an effective and well-coordinated crisis response.

Introduction

This article presents the findings from an empirical qualitative study of how smaller nonprofit human service organizations (SNHSOs) in England and Wales responded during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–September 2020). The research is built upon a previous study on the distinctiveness of SNHSOs delivering welfare services undertaken between 2016–18 (see Dayson et al., Citation2018, Dayson et al., Citation2022). Both studies defined SNHSOs as those with an annual income under £1 million but over £10,000 which could also be classified as “voluntary agencies”. These organizations retain certain voluntary characteristics such as volunteers and donations but employ at least one paid member of staff and are formally registered as charities (see Dayson et al., Citation2018, Billis & Glennerster, Citation1998). We use the term “smaller” rather than “small” to emphasize the relationality of our study. Throughout the research participants contrasted the work of small locally based nonprofit organizations to that of large organizations, commonly public sector bodies or regional or national human service delivery charities.

Our article is positioned within wider international debates about the extent to which SNHSOs are distinctive from other (larger) human service providers in the nonprofit and public sectors (Dayson et al., Citation2022, DiMaggio & Anheier, Citation1990, Macmillan, Citation2013) and the corresponding implications this has for public service delivery and the relationship between SNHSOs and the state (Buckingham, Citation2009, Kramer, Citation1994, Milbourne and Cushman, Citation2015, Rochester, Citation2013, Smith and Lipsky, Citation1993). These distinctiveness debates are themselves nested within wider questions about why nonprofit organizations exist at all; the relative importance of their size, form, and function; why and how they provide human services; and why they have not been crowded out by the state and market (Billis & Glennerster, Citation1998, Dahlberg, Citation2005). Although our study and findings are England and Wales focussed, these debates are recurrent in international discussions about the definition and boundaries of the nonprofit sector, and its role in human service provision (Evers & Laville, Citation2004).

The global nature of the COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique contemporary lens through which to study smaller nonprofits and their contribution to human services, as well as the broader implications for state-nonprofit relations. In late March 2020, the emergence and rapid spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), led Governments around the world to enact policies requiring all those who could to remain at home except for essential shopping, daily exercise, or medical treatment. Schools and many workplaces were shut down for most people. In the UK people identified as “clinically extremely vulnerable” were required to “shield” from almost all physical human contact. Only essential “key workers” – health, frontline transport staff, essential retail and some public services – were exempt. Thus, for almost three months the whole of the UK entered a severe “lockdown” until gradual easing in May, with the lifting of most restrictions only occurring in July 2020.

The unique global health, economic and societal dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent Government responses have led scholars to describe it as a “syndemic”, the effects of which interacted with and exacerbated existing inequalities, giving rapid rise to a diverse range of personal, financial, and community needs (Bambra et al., Citation2020). In this context, it should perhaps not be a surprise that the smaller end of the nonprofit sector around the world was central to how societies responded to the immediate and longer-term impacts of the pandemic (Rees and Bynner, Citation2022). Numerous accounts describe how many smaller nonprofit organizations’ instinct was to identify and then meet the emergent needs of their communities and beneficiary groups in real-time. They often adapted to deliver services in new ways (including online using digital technology) and worked collaboratively with local public and other nonprofit human service providers and existing and new community and mutual aid groups (Dayson et al., Citation2021).

In light of the unprecedented nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the scale and scope of smaller nonprofit organizations’ response, this article draws on in-depth, qualitative case study research undertaken in England and Wales to address three main research questions:

How did smaller nonprofit human service organizations respond to the COVID-19 pandemic?

Drawing on the perspectives of local stakeholders, to what extent was their response similar or different from other (larger) providers of human services in the nonprofit and public sectors?

How do these findings add to our understanding of the role of smaller nonprofit human service organizations in contemporary welfare systems?

In addition to providing original and in-depth empirical insights about the role of SNHSOs during the pandemic, our key contribution is to show that a more dynamic and nuanced understanding of nonprofit-state relations is needed in order to understand their respective roles during times of crisis. Most “traditional” theories of sector relations have tended to position these relationships as being relatively settled at the organizational level, involving partnership and collaboration. But the COVID-19 pandemic unsettled the human welfare service landscape in profound ways such that these relationships became – for a time – much more dynamic and fluid, with for example many SNHSOs shifting between supplementary and complementary roles (Young, Citation2000) as the pandemic evolved.

We situate our account in the “strategic action field” (SAF) framework developed by Fligstein and McAdam (Citation2011, Citation2012). In developing their field-based account, they were particularly concerned to build a theory of social change and stability. We see this account as a compelling way to understand the dynamics of change in SAFs occupied by organizations acting collectively and in contention, within a shared understanding of the norms shaping the field. Fields, for example, can experience long periods of relative stability, or “rolling turbulence,” and change in a neighboring or “proximate” fields can influence those around it (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011). Moreover, the SAF framework pays attention to the detailed stages of change, positing a process by which fields can experience exogenous shocks, which may cause crisis in the field and the onset of contention, which if severe enough can lead to an episode of contention, followed usually by a new and revised settlement.

Clearly, COVID-19 was a profound exogenous shock to all social fields globally, and the notion of a destabilizing “episode of contention” is particularly applicable to the radically “unsettling” nature of the COVID-19 crisis (Macmillan, Citation2020). The SAF framework has been extended in the last decade, but some uncertainties remain, for instance in the exact nature of the different stages of change (which inevitably will vary in reality). Our study demonstrates that the SAF framework performs well in accounting for the radical unsettlement of the pandemic in the field of human services. SNHSOs demonstrated great absorptive and adaptive capacity during this time (Dayson et al., Citation2021) whilst at the same time contending with increasing financial and human resourcing challenges (Clifford et al., Citation2023) that threatened their sustainability and position in the contemporary welfare system.

Background

For more than 40 years, a large international body of literature has attempted to explain the value and continued existence of the nonprofit sector based on its comparative advantages over other sectors. Some explanations of their comparative advantage are what organizational theorists refer to as “instrumental” in nature. Here, the understanding of nonprofit organizations’ behavior is driven by a focus on features or practices that enable rational goal attainment (see Considine, Citation1988, Mitchell, Citation2018). For example, Weisbrod (Citation1986) argued that the value and existence of the sector hinged on the relative failure of the state and for-profit sectors to provide collective good. Therefore, the sector provided an alternative source of public good to those left behind (Kingma, Citation1997). Equally, Hansmann (Citation1980) identified how nonprofit’s “non-distribution constraint” generated trustworthiness for potential donors and funders that is perceived to be lacking in for-profit organizations. By contrast, Salamon (Citation1987), argued that although nonprofits often provide the first response to human needs, they require partnership with the state to redress purported “failings” relating to a lack of resources, inequitable provision, paternalism, and amateurism. Building on that, Smith and Lipskey (Citation1993) described a “mutual dependence” between nonprofit and state sectors in the provision of welfare services whilst Young (Citation2000) highlighted how nonprofits can both supplement and complement state requirements, whilst also fulfilling a more adversarial campaigning and advocacy role in some instances.

Although instrumental views provide a window of understanding into the effectiveness and functionality of nonprofit organizations, they risk reducing a complex phenomenon to a limited set of functional aspects (Alvesson, Citation1989). Billis and Glennerster (Citation1998) echo this point by suggesting more detail should be paid to the relational features of nonprofit organizations over instrumental and functional views. They argued that nonprofits are distinctive from other forms of human service providers because of their roots in the associational “world.” Associations are able to resolve problems and coordinate action based on membership, shared ownership and voting. Even though they are prone to taking on some bureaucratic attributes of other types of human service providers, such as paid staff, they also retain several informal associational characteristics. For example, they are more likely to involve volunteers, receive donations or membership fees, and be accountable to diverse stakeholders, including board members, staff, funders, members, volunteers and users. These relational features, Billis, and Glennerster argued, allow nonprofit human service organizations to be more effective at addressing financial, personal, and community disadvantage due to greater motivation, sensitivity to and knowledge about user needs.

The relatively small size of nonprofit human service organizations is central to the theories discussed above. Billis and Glennerster (Citation1998) suggested that as nonprofits grow larger, their distinctiveness and comparative advantage over other human service organizations – in terms of efficiency, effectiveness, and user experience – is likely to decrease. More recent studies have leant further credence to these arguments with varying degrees of caveat (see for example Harris et al., Citation2003, Milbourne and Cushman, Citation2015, Rochester, Citation2013). Being smaller, these authors claim, might mean that nonprofit human service providers have a better understanding of user needs, a more personal approach, and greater innovation, creativity, flexibility, and sensitivity (Bovaird, Citation2014, Hogg and Baines, Citation2011). These hypotheses are borne out in our own previous research which also highlights the importance of related features of SNHSOs such as being embedded in local geographic communities, informal, familial organizational cultures, and adhering to a person-centered ethic of care (Dayson et al., Citation2022).

The types of “distinction” claims referenced above are assertions of value (Macmillan, Citation2013) and are used by SNHSOs and their advocates to “jockey” or contend for position and resources within different fields of activity (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011, Macmillan et al., Citation2013). Fligstein and McAdam’s concept of Strategic Action Fields (SAF) is particularly apposite in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. SAFs are meso-level social orders in which actors interact under a common set of understandings including the purpose of the field and what is at stake, and fields might be geographically based, for instance, a local assemblage of voluntary sector organizations (Taylor et al., Citation2016). Fields are subject to shocks which can create conditions of crisis where these shared understandings are destabilized, re-interpreted and contested, and a new “settlement” is established – this clearly happened on a global scale as the COVID-19 crisis unfolded. The SAF framework is helpful for it enables us to conceive of episodes of contention – moments of significant societal upheaval – as “unsettlements” (Macmillan, Citation2020) through which developments in one “field” of activity (in this case a global public health crisis) rapidly cascade through others, including human services and the nonprofit sector (Fligstein and McAdam, Citation2012, Macmillan et al., Citation2013).

The SAF framework is an ambitious attempt to create a “general theory” of social change and stability, but there is some ambiguity in the temporal phasing proposed, both in the theoretical terms and the likely way this plays out in reality. In short, it posits a process by which fields are subject to exogenous shocks which if severe enough can lead to an episode of contention, followed usually by a new and revised settlement. Change in SAFs unfold through a “process that speaks to the capacity for social construction and strategic agency” (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011, p. 9) and in an episode of contention we may witness the collective construction of the threat, organizational appropriation, mobilizing, and sustaining action in face of the threat, and innovative action that violates current field rules in relation to acceptable practices. An episode of contention lasts as long as a “shared sense of uncertainty regarding the structure and dominant logic of the field persists” (Ibid, p 10) and, finally, the field gravitates toward a new – or refurbished – institutional settlement around (revised) field rules and cultural norms. End of crises signal a generalized sense of order in which certainty has returned. As we have seen, the COVID-19 crisis was exactly the kind of volatile context that required nonprofit organizations to make sense of what’s changing and develop new ways of working, relating to stakeholders and responding to need (Taylor et al., Citation2016, Macmillan, Citation2020).

Considering the turbulence brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, as with other moments of “unsettlement” such as the 2008 economic crisis (Macmillan et al., Citation2013), it is appropriate to revisit prior evidence and debates and consider the extent they hold true or need updating in light of new evidence. Prior to the pandemic, numerous authors had highlighted the fragility of SNHSOs compared to larger providers due to their often over-reliance on key individuals and limited resources (Aiken & Harris, Citation2017; Dayson et al., Citation2022). This fragility is likely to have been exacerbated by the pandemic, creating a “three-dimensional crisis” for the nonprofit sector of resourcing, operation, and demand (Macmillan, Citation2020) which could undermine many of the advantageous features of SNHSOs discussed in this section. These downsides echo Salamon (Citation1987) (see also Dayson et al., Citation2022), who argued that nonprofit’s purported “failings” need to be balanced through action (i.e. a supportive partnership) from the state, and necessitate a more rounded discussion of how SNHSOs may play a role that is complementary or supplementary to larger human service providers within the ‘organized welfare mix (Bode, Citation2006, Dayson & Damm, Citation2020, Macmillan and Rees, Citation2019, Young, Citation2000), particularly during times of crisis.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. Next, we present the methodology for this research, including how it built upon the original 2016–18 study. Then, we present our main findings in relation to the first two research questions, outlining how SNHSOs organizations respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, drawing on comparative accounts from key stakeholders to contrast their response with that of larger nonprofits and public sector human service providers. Finally, in response to the third research question, we situate these findings in the context of the literature outlined above and consider the extent to which they add to our understanding of the role of SNHSOs in contemporary welfare systems.

Methodology

This article draws on data from a qualitative study of SNHSOs in four case study localities in England and Wales undertaken between August 2020 and January 2021. Research fieldwork took place between August and October 2020 and focussed on the initial period of lockdown between March and June 2020, and the subsequent July–September 2020 period during which society began to “reopen”. The study built on previous research in the same four localities undertaken from 2016 to 18, which explored the key characteristics and value of SNHSOs and whether they provide any benefits in tackling disadvantage through human services (see Dayson et al., Citation2018, Dayson et al., Citation2022). Building upon the original study, this second study sought to understand if these characteristics conferred specific advantages during a global pandemic. Both studies were commissioned by the Lloyds Bank Foundation for England and Wales, an independent philanthropic funder of “smaller SNHSOs” (defined as those with an annual income under £1 million but over £10,000 - see Dayson et al., Citation2018). The studies were limited to nonprofits who could also be classified as “voluntary agencies” which retain voluntary characteristics such as volunteers and donations but employ at least one paid member of staff and are formally registered as charities (Billis & Glennerster, Citation1998, p. 90). Drawing on data from the National Council of Voluntary Organizations (NCVO, Citation2022), the overall population of UK nonprofits that meet this criteria is approximately 85,000, or around 51% of the whole nonprofit sector.

How to define the size of nonprofit organizations is contested and the boundary line between “smaller” and “larger” organizations risks being arbitrary, particularly for borderline cases. Our chosen definition, however, was developed by the Small Charities Coalition in the UK, so aligns with the thresholds used in contemporary policy discourse. Our sampling also made a clear conceptual distinction between smaller organizations, which often operate locally, and larger organizations with multi-million budgets, which tend to operate regionally or nationally.

For the original study, administrative data sources and qualitative insights were used to purposively sample four local authority areas as case studies. They are distributed geographically across England and Wales, covered the different tiers local authority administrative statuses (District, Metropolitan and County), varied according to levels of economic deprivation, and the qualitative characteristics of the local nonprofit sector (such as levels of public funding, local philanthropic practices, and levels of informal and formal volunteering) were also taken into account. An overview of the four selected areas is provided in .

Table 1. Overview of case study areas.

In 2016–18 the main source of data for the study was 12 nested qualitative organizational case studies of SNHSOs with annual income under £1 million and over £10,000 (four in each local authority area). Additional data included four further case studies of “larger” SNHSOs with annual income more than £1 million (one in each area) and 7–8 semi-structured interviews in each area with key stakeholders (other SNHSOs, public sector human service providers, LIOs etc) to explore key themes in more depth.

For this follow-up study, we revisited each of the four areas with the aim of engaging with each SNHSO case study organization from the original study and between four and six local stakeholders who had been interviewed previously. SNHSO participants tended to be senior leaders (employees and trustees) with strategic or operational oversight of their pandemic response. Local stakeholders included public sector employees from the NHS and local authority (referred to as “Public Sector Stakeholders” in the findings), employees from local nonprofit umbrella bodies, and representatives of larger nonprofits active in the area (both referred to as “nonprofit stakeholders” within the findings). Stakeholders were selected based on their understanding of the human services provision within the area, their awareness of how the specific SNHSO (or SNHSOs in general in that area) had responded during the pandemic, and their understanding of the wider local pandemic response by different organizations.

Each qualitative interview explored the participant’s experience of and perspectives on how their SNHSOs and/or SNHSOs in their area responded to the pandemic and how this contrasted with their knowledge and experience of how large nonprofit providers and public sector bodies responded. Overall, we interviewed 39 people for this study, as outlined in . The study received ethical approval from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Ethics Committee.

Table 2. Overview of research participants.

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVIVO software for analysis. Data were analyzed thematically and iteratively in two stages. First, key themes and sub-themes were generated at case study level through a process of induction and deduction (Langley, Citation1999). Second, case study level themes were compared for generalizability and points of departure and common themes and sub-themes were generated and organized in relation to the research questions stated earlier in this article.

Findings

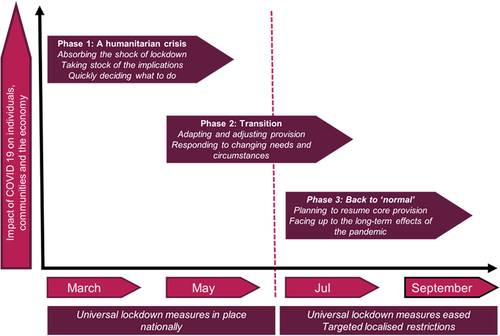

We present our empirical findings from the study in relation to different roles SNHSOs engaged in over the course of the pandemic. The initial phase can be understood as a rapid response to a humanitarian crisis brought about by the first Government lockdown; the second as a phase of transition, during which organizations adapted and adjusted their provision to meet evolving need and changing public health restrictions; whilst the third phase was characterized as “getting back to normal” over an extended period (as initially outlined in Dayson et al., Citation2021 and illustrated in ).

Figure 1. The three phases of the COVID-19 pandemic for SNHSOs (March-September 2020).

Within each phase, we discuss the kind of work SNHSOs did during the pandemic, how they approached that work and the people they worked with (research question 1); and the extent to which this set them apart from other types of (larger) human service organizations (research question 2). The resourcing and sustainability of SNHSOs are also considered given the fragility of SNHSOs prior to the pandemic (Aiken & Harris, Citation2017, Rees and Bynner, Citation2022) and suggestions that the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have exacerbated such issues (Dayson & Damm, Citation2020, Clifford et al., Citation2023). Overall, the findings tell a story of the dynamic and responsive work of these organizations as they shifted to supplementary roles and then complementary roles based on the urgent and developing needs. They also describe how smaller organizations were able to respond to a range of service users in different and distinctive ways, acknowledging the particular and acute challenges faced by subsets of the wider community.

The initial phase – supplementary role of SNHSOs

Our findings demonstrate the supplementary role SNHSOs played during the rapid response to a humanitarian crisis brought about by the first Government lockdown.

Supplementary activities

In the initial phase of the pandemic, we found that SNHSOs in our study focused on addressing the following key areas of need: keeping people physically safe and well through providing access to food and medicine (i.e., delivering personal prescriptions); providing regular and accessible information about the pandemic; and mitigating the impact on mental health, particularly through tackling isolation and loneliness. These activities illustrate the supplementary role of SNHSOs as they met the most basic needs for disadvantaged and vulnerable communities and individuals as wider public sector systems and processes failed.

i. Keeping people physically safe and well

SNHSOs very quickly recognized the requirement within many communities to support the most basic of needs – that of access to food and medication. With whole communities being asked to stay at home, and with many of the most vulnerable being asked to shield in order to protect themselves and reduce risk of infection, there was a very sudden shift in need without preexisting, tried-and-tested processes for meeting it. Overnight, voids appeared in the formal and informal support systems of vulnerable people, and it became difficult for some of their most basic needs to be met. We found that it was commonly the smaller nonprofit organizations that were able to implement solutions to meet these needs quickly, as explored by one participant as they narrated their experiences:

By the end of the week [the first week of lockdown in March 2022], we were doing home care to all our vulnerable clients. So, all our staff that we had in the building we released to go to people’s homes, to try to support them at home. We also did meals on wheels straight away to make sure we could take proper nutritious meals into everyone’s homes, and afternoon tea as well, so that everyone was fed still … For people that had carers, we would send out wellbeing packs, so in that was lots of activities and things to keep yourself active and mentally OK during lockdown. And we also did wellbeing calls, where we had staff running through the list of clients and calling them to check on clients and carers. (SNHSO, Area 4)

The example outlined in this quote is indicative of how numerous participants perceived SNHSOs as playing a supplementary role to state during the early stages of the pandemic because of the speed and flexibility in their response to needs were identified in real time. Local public sector stakeholders recognized that this responsiveness to local needs was something that set SNHSOs apart from public bodies and larger nonprofits in the early days of the pandemic.

They responded in such an agile way. They went from providing services in person, to providing at distance, doing different things if you’re not going to be driving people anymore, they moved to doing people’s shopping for them, they just found really creative ways of working. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 1)

This extract above demonstrates the perception held by many participants, regarding the distinctive response of many SNHSOs. This participant’s knowledge of organizational responses during this period clearly underpins their sense in which SNHSOs adapted creatively during their supplementary role.

ii. Providing regular and accessible information

What was important to participants in this study was the way in which smaller nonprofits were able to use existing trust-based relationships and well-established communication channels, and how these proved effective as a means of conveying key information to people at a community level, as explored by the following stakeholder:

I think for me what the sector can do is, to talk to their communities in a way that public sector organizations can’t, so the trust is built. … And a message coming from them carries a lot more weight. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 3)

The scale of SNHSOs was seen as an important feature of their supplementary role, as they were able to reach out to engage with community members in very targeted ways that took account of specific needs and circumstances, including language and communication norms and preferences, as is illustrated by the following perspective provided by a public sector participant:

Everyone [each SNHSO] has their own pocket of the borough, their own patch … If you’re concentrating on a small, concentrated area that’s what people who are feeling vulnerable want. Ultimately, they want to feel like they’ve got a friend. (Public sector stakeholder, Area 2)

As explored in this extract, a number of participants highlighted the sense in which local, targeted activities met the specific needs of this period of time in ways which others were failing to achieve.

iii. Mitigating the impact on mental health

Reflecting the relational and trust-based nature of their approach, SNHSOs found multiple ways to supplement existing efforts through the maintenance of human contact by checking up on vulnerable and isolated people, keeping in touch with them and connecting them to one another wherever possible. One stakeholder explained that they felt this was a feature which distinguished SNHSOs during this early phase:

What the [SNHSOs] can do is what we struggle with – that personal touch, getting to know someone, offering them a consistent face, they speak to the same person and build a relationship. If you’re that resident and you’ve not spoken to someone all week that continuity is really important. (Public sector stakeholder, Area 2)

How SNHSOs activities were supplementary to larger providers

The supplementary role of SNHSOs during this phase of the pandemic is evident when we compare their response to larger nonprofit and public sector providers. Across the four case study areas, stakeholders from the public sector contrasted the work of smaller nonprofit organizations to that of larger organizations, commonly large public sector providers or regional or national charities. Our findings tell an important story about stakeholder perspectives on the responsiveness of smaller organizations, and the agility with which they could develop new responses very quickly as compared to larger organizations. Specifically, it was the small size and local embeddedness of these organizations that facilitated this supplementary role.

During the early stages of the pandemic the size of these organizations, and the relative simplicity of their administrative and governance structures, was an important feature which made a significant difference to the speed of their response. The small scale of SNHSOs enabled them to adapt and move quickly to fill a void left by the sudden shift in priorities and service capacity of mainstream public services. In each of the data extracts below, a public sector stakeholder is acknowledging the importance of organizational size, and the way in which this resulted in SNHSOs being able to move more quickly within a crisis context.

As opposed to a public body or larger organization, I do feel that a smaller organization, third sector particularly so, can be quite responsive … they may be on the ground, more local level and can identify more quickly to a changing need. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 4)

It is that value of small, where [in contrast] if you were cogs in the chain [of a bureaucracy] that need to be signed off, they can just do it. And the reduced level of governance definitely helps. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 1)

As the following data extract further highlights, there was also acknowledgment amongst study participants that they felt that larger organizations do move and respond, but it can take longer:

A small organization can color itself differently much more quickly than a larger organization. It can be responsive far more coherently. That’s what this organization has really demonstrated. The public bodies did that in a time frame, but it was a timeframe because these larger organizations tend to move a little more slowly. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 4)

Another feature which set SNHSOs apart during the initial “humanitarian response” phase of the pandemic was the relationships that these organizations already had within a diverse range of communities who were adversely affected by the pandemic. As we identified in our previous research, the importance of relational features of SNHSOs such as being embedded in local geographic communities, informal, familial organizational cultures and a person-centered ethic of care (Dayson et al., Citation2022) enabled these organizations to use their established relationships to ensure the flow of information and resources to people and communities where they were most needed. One stakeholder explained how SNHSOs in their area performed this vital role:

In some parts of the city … the VCSE organizations come into their own because they’ve … driven the infrastructure that made those nicer places to live in, be educated in, and work in. Therefore, the reach into those families and communities has to be via those organizations. If we don’t take those groups with us, we would get pilloried. You know we have to collaborate, and work, and co-produce with those groups all the time. (Nonprofit stakeholder, Area 4)

Our findings demonstrate, therefore, how SNHSOs were an essential component of the initial response to the pandemic, playing a supplementary “first responder” role that larger nonprofits or public bodies arguably could not have fulfilled. However, we do not suggest that they were the only responders, that they met all needs, or indeed that this alone would have been sufficient in the longer term. Rather, our findings demonstrate that SNHSOs moved quickly into the human service voids created by the pandemic and associated restrictions, holding the space and modeling ways of meeting urgent need whilst other organizations adapted and devised new ways of working.

It is important to note that in framing the response of SNHSOs as supplementary we are not suggesting larger providers were unwilling to act, or unable to recognize what was required within communities. In many cases, stakeholders reflected on the greater levels of bureaucracy faced by larger public sector providers, which at times stifled urgent responses and rendered these organizations unable to generate the urgent humanitarian response required within the early stages of the pandemic. But crucially, not being rooted in a locale or immediate community of need was perceived to blunt the immediacy and moral urgency of their response. In contrast, SNHSOs reported how they felt compelled to respond, “above and beyond” any contractual necessity.

Transition phase – SNHSOs complementary role

In the second phase of the pandemic, there was a transitionary period during which organizations adapted and adjusted their provision to meet the evolving need. The role of SNHSOs shifted from supplementary to complementary as they worked in collaboration with larger organizations and focused on groups disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

Complementary activities

A consistent theme within our data was how smaller nonprofit organizations tended to support people facing multiple forms of disadvantage due to intersecting factors such as health, economic status, geographic location, race, and ethnicity. For many of these people, smaller nonprofit organizations represented their primary source of support and information, as they tended to be those who were already less well served by mainstream statutory provision prior to the pandemic.

This is about poverty. A lot of the charities are geared to refugees and migrants, homeless people and people who are out of work – all of them have been double whammy’d by COVID. (SNHSO, Area 2)

SNHSOs ability to work with people who didn’t reach the increasingly high threshold for support from some public services help to create the conditions for which they could play a complementary role to large providers.

So you know it is recognizing that [SNHSOs] were already helping to do a lot of the work with people who probably would not reach the criteria for services and recognizing that [they] had probably a much wider reach than our services … (Public sector stakeholder, Area 2)

These smaller SNHSOs had the existing relationships with these groups and communities to quickly recognize the needs emerging during this phase of the pandemic. This included the “knock-on” effects of the pandemic like rent arrears, debt arising from job losses and the withdrawal of informal mutual aid and more formal statutory support as lockdown eased. A consequence of this complementary activity was the sharp increase in service demands:

So, the furlough [UK Government scheme to recompense people who were unable to work] was a huge, huge, massive, additional amount of enquiries. And we were getting that from new clients that wouldn’t normally get in touch. (SNHSO, Area 1)

Participants talked about how smaller SNHSOs were able to complement existing provision by scaling up their services whilst still retaining their close links with people. This was despite the pressures presented by increasing levels of need during this phase of the pandemic. Participants suggested this adaptability enabled some smaller nonprofits to ensure a degree of consistency in terms of user experience, further supporting and embedding the trust-based relationships that they already had with communities:

The small charities have scaled up, increased their capacity and in a short space of time. As a big organization – the council call center – we had 20 people trained on our inquiry line and you speak to a different person each time. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 2)

The ability of SNHSOs to play a complementary role in the transitionary phase was bolstered by the visibility their response in the initial stages of pandemic, making them more visible to larger organistions. One stakeholder explained how they were keen to use this experience to inform their strategy moving forwards:

So you know it is recognizing that [SNHSOs] were already helping to do a lot of the work with people who probably would not reach the criteria for services and recognizing that [they] had probably a much wider reach than our services, which is absolutely right but how do we work that and recognize that in our kind of overall strategy. So I think, I think that really sort of shaped the things we’re going to progress forward on for the next five years. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 3)

Therefore, new collaborations and ways of working emerged as the pandemic progressed. One example of this collaborative activity was the creation of an area level approach to provide mental health support to people who were not visible to statutory services.

So, [they] came together very very quickly to pull together an offer for people who were not known to the mental health trust and who needed that mental health support. And we wouldn’t have been able to mobilize something that quickly with a statutory organization. The flexibility they had to deliver something in a very different way, in a COVID way. But the way in which they responded to do that in such a short space of time, and with the link that they have in the reach that they have into wider [voluntary sector] partners was really well valued … (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 3)

There was a mixed response to this collaborative working across the case study areas. In some areas, participants suggested that the larger organizations wanted to take the lead to establish top-down processes, which caused some tensions. However, in other areas this has led to new and positive collaborations between organizations and sectors, with greater power sharing and two-way accountability.

How SNHSOs activities were complementary to larger providers

The role of SNHSOs was complementary in this phase because of how they understood the needs of the vulnerable communities and individuals with whom they were working. Participants consistently argued that SNHSOs recognized the need to make every effort to deliver a face-to-face service wherever it was safe and possible to do so. This often involved lengthy and onerous risk assessments, but these organizations recognized the significance of remaining visible and being physically present, as explained by the following stakeholder:

The voluntary sector organizations continued to do frontline face-to-face services whereas the local authority were working from home. (Public Sector Stakeholder, Area 2)

This wasn’t necessarily about numbers reached by a service, but rather the significance these SNHSOs placed on retaining a physical, visible presence in the lives of their beneficiaries, despite the restrictions the pandemic enforced. Both SNHSO respondents and public sector stakeholders reflected that it was this visible presence, and the way in which they adapted their services and approaches that complemented the approach of other services.

SNHSOs desire to retain their familial values was a key driver in their striving for face-to contact wherever possible. The following extract illustrates how significant they perceive this familial approach to be:

And because you’re based in communities, working with communities, it’s hard, if somebody’s got a real face, and you know their name, and where they live, it’s very hard to say, ooh actually we’re a bit risk averse so we won’t deliver any services. You can’t can you? You just can’t do it. It is that, if we’re saying we’re a family, then you honor that family don’t you? (SNHO, Area 4)

Public bodies and larger nonprofits were able to maximize the impact of their own provision by working through these smaller nonprofits who reached groups and communities that were disproportionately and multiply affected by COVID-19 (due to ethnicity, poverty, and preexisting health inequalities).

Back to normal phase – SNHSOs complementary role in a crisis

In this third phase of the pandemic, SNHSOs continued to act in a complementary role but in the context of a number of persistent organizational challenges created by the pandemic. These challenges related to resources and sustainability and risked undermining their contribution in the longer term. These resource challenges were both financial, relating to funding reductions and unpredictability, and human, relating to the effects of the crisis on staff and volunteer wellbeing and the potential for “burnout.” Moreover, the syndemic nature of the COVID-19 crisis exacerbated existing inequalities and complex social issues in the communities and individuals SNHSOs support, further straining financial and human resources. The organizational challenges facing the SNHSOs in this study reflect the acute three-dimensional crisis (resourcing, operation, and demand) facing the sector identified by Macmillan (Citation2020).

In terms of financial resources, SNHSOs reported that the pandemic would have a lasting impact for their sustainability. Although there was an increase in some short-term funding related to the pandemic (Dayson et al., Citation2021), they were also conscious of needing to lay foundations for increases in future demand, with the rise of mental health problems a particular concern. For example, one SNHSO highlighted the way in which, despite being recognized during the pandemic emergency response, they were concerned that this would not filter through to future funding and commissioning decisions, despite representing a large minority ethnic community, stating:

During COVID we were recognized, our contribution. With funding, we have to be recognized. (SNHSO, Area 2)

For some SNHSOs, the concerns about financial sustainability were more immediate, however. In Area 2 several were struggling to access funding prior to COVID-19 as a result, they thought, of the wider trends in the funding environment and had “found their funding significantly and adversely affected as a result of the pandemic … with sector cuts on the horizon alongside expected spikes in need” (SNHSO). Some SNHSOs lost all or some of their core sources of income almost overnight, for example, income from room or building hire and community fundraising events, whilst others were struggling to secure funding for ongoing priority work due to the emphasis funders were placing on the response to the pandemic:

All the funding [bids] we have sent out, they are just telling us that priorities have changed because they are just taking applications for COVID-related activities. If it’s not COVID-related it is a bit difficult for you to secure finding (SNHSO, Area 1).

There was near unanimous concern across the case studies about the availability and stability of future longer-term funding. One SNHSO said that the emergency funding had been helpful in terms of enabling them to respond to the immediate situation, for example enabling them to buy Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and erect partitions to continue delivering face-to-face services. However, they were hugely concerned that there would not be reliable funding in the years following the pandemic:

For the funders, they need to realize that right now small charities need unrestricted funding because things can change before they know it (SNHSO, Area 1)

In terms of human resources, several SNHSOs expressed concerns about staff and volunteer wellbeing. For example, one participant explained how the SNHSO in Area 1 found it extremely challenging to work remotely:

So, with the COVID situation, people were completely out of their comfort zones. They were using equipment; they were using a different telecom system that they hadn’t used before. And we had about a week because we were OK for people to come in the office, so we started planning that we could get them in and give them some training on this. But then we set up remote supervision which, again, was difficult for the supervisors because they’d never done that before. (SNHSO, Area 1)

As this participant explained, they felt that this organization needed to provide additional emotional support to the workforce due to working from home but also heightened emotional burden due to the intensity of frontline delivery. Similarly, in Area 4 one SNHSO reported that they tried to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the wellbeing of staff, volunteers, and trustees, by putting in place mutual support systems to ensure people remained connected and supported. This was something they believed was vital to the strength of their external response to the crisis but would also need to be sustained in the future.

Discussion: implications for our understanding of the role of SNHSOs in contemporary welfare systems

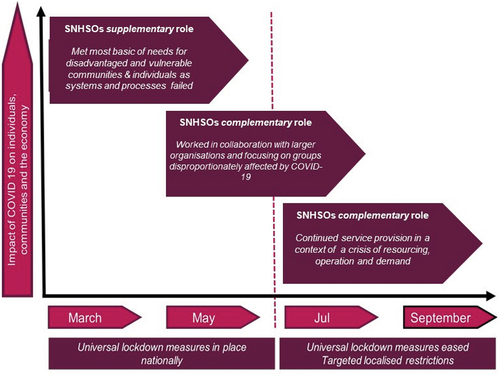

In this section we discuss the key findings of our study in relation to the final research question about the implications for how we understand the role of SNHSOs in contemporary welfare systems during and beyond times of crisis. Many of the mainstream theories of state-nonprofit relations implicitly position SNHSOs as static or fixed at an organizational level, in response to a specific set of circumstances. Such frames work well in periods of relatively settled relationships, but our findings highlight the importance of understanding how these change over time and in response to external contexts and stimuli at an organizational level, particularly in a time of crisis and thus significant “unsettlement” (see ).

Figure 2. The evolution of SNHSOs-state relations during the COVID-19 pandemic (March–September 2020).

Over the period of the crisis, our study shows how many SNHSOs fulfilled varying supplementary and complementary roles in relation to the state in combination and at different points in time (Dayson & Damm, Citation2020, Young, Citation2000). This provides a contrast to traditional views of nonprofit-state relations which pay scant attention to how organizational roles may change over time (Hansmann, Citation1980, Weisbrod, Citation1986, Salamon, Citation1987). Early on during the pandemic, our findings demonstrate that SNHSOs moved quickly into the human service voids created by the pandemic and associated restrictions. Here, SNHSOs played a supplementary role to the state (e.g. Weisbrod, Citation1986) by “holding the space” and modeling ways of meeting urgent need whilst large public and nonprofit organizations adapted and devised new ways of working in order to meet need in the longer term. The effectiveness of SNHSOs response in this phase made them more visible to the state and enabled new collaborations and complementary ways of working (Young, Citation2000) from the transition phase onwards. At this point, state-SNHSO relations were probably better reflected by Salamon’s (Citation1987) argument that although nonprofits often provide the first response to human needs, they require a sustained partnership with the state to redress purported “failings” relating to a lack of resources, inequitable provision, paternalism, and amateurism. Of these purported failings, our findings suggest that resources, both financial and human, are a particular challenge for many SNHSOs in the short, medium, and longer term and that additional investment, from the state or philanthropic sources, was necessary to sustain their work over a longer period. These concerns are echoed by Clifford et al (Citation2032), who found that smaller nonprofits, particularly those with an income under £100k, have been most significantly affected by declines in income during the pandemic. By taking a relational view of nonprofits posited by Billis and Glennerster (Citation1998) (see also Dayson et al., Citation2022) we show how SNHSO’s understanding of user needs, flexibility, sensitivity, local embeddedness, informal, familial organizational cultures, and person-centered care ethics enabled a rapid and successful response to the pandemic. These positive and distinctive features of SNHSOs equipped these organizations to fulfill supplementary and complementary roles during the early stages of roles during the COVID-19 pandemic.

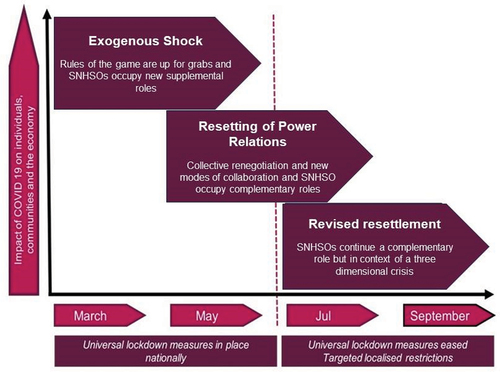

Given the dynamic and fluid nature of state-nonprofit relations during the pandemic, we argue other frames such as strategic action field (SAF) theory (Fligstein & McAdam, Citation2011) are more fruitful in helping to understand how these shifted and evolved over the course of the pandemic. Macmillan (Citation2020), for example, utilized SAF theory to suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic was a form of “unsettlement” through which relational boundaries between key actors may be redrawn as nonprofit organizations sought to negotiate a “three-dimensional crisis” for the nonprofit sector of resourcing, operation, and demand. In SAF terms, fields contain both “incumbent” and “challenger” organizations, vying or jockeying for the strongest position within the field, by deploying resources at their disposal which can be material or symbolic: fields are therefore marked by “routine, rolling turbulence” even in times of relative stability (and where shared norms and rules of the game are negotiated by field actors) (Fligstein and McAdam, Citation2012, p. 19). Crucially for our account, SAFs are often linked proximately and at different scales, and can be hit by exogenous shocks – the pandemic is an obvious example – that lead, in a stepped or phased manner, to an “episode of contention” or major unsettlement in the field, marked by great uncertainty and a scramble to understand, reinterpret, and ultimately reestablish new rules and norms, and potentially, the opportunity to materially recast roles within the field. sets out visually how these circumstances played out for SNHSOs during the first 6 months of the pandemic.

Figure 3. Conceptual framework of evolving SNHSOs-state relations as strategic action fields during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although there is some inconsistency evident in Fligstein and McAdam’s (Citation2011, Citation2012) identification of discrete stages following an exogenous shock, as well as a general precaution that theory cannot precisely predict empirical reality, the key point is that the SAF framework alerts us to the dynamics of change in a field and the strategic agency of field actors. In the early stage of the pandemic, in our local case fields, we saw “challenger” SNHSOs scrambling to occupy new roles, in the relative absence of “incumbent” local authorities and the wider public sector; as well as discursively buttressing these new roles and expectations at different scales. Relationships between SNHSOs and larger public sector and nonprofit organizations were up for grabs, perceived by the former as resetting power relations and new modes of collaboration; while as described above, ultimately “incumbents” gradually restored their preeminent position within the local field. Towards the end of the research study, there were indications of a return to a “new normal”, revised settlement (see ).

Conclusion

This article has presented insights from an empirical study of how smaller nonprofit human service organizations (SNHSOs) in England and Wales responded during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic (March–September 2020). As discussed in sections 1 and 2, we built upon our own research into the distinctiveness of SNHSOs delivering welfare services (Dayson et al., Citation2022) alongside wider debates about the extent to which SNHSOs are distinctive from other (larger) human service providers and the relationship between SNHSOs and the state. Our findings document a response to the pandemic that was immediate, dynamic, and responsive, and in which SNHSOs adapted flexibly to meet urgent and developing needs. The findings also document how smaller organizations were able to respond to different service users in different and distinctive ways, often working with subsets of the community most severely and acutely affected by the pandemic due to intersectional factors such as health, economic status, geographic location, race, and ethnicity.

Our findings have some important implications for how we understand the nature of state-nonprofit relations, particularly during times of crisis. Whereas a number of traditional theories of state-nonprofit relations position these as relatively static or stable, we argue that a more dynamic and nuanced understanding is required. Static accounts work well in times of relative stability, the situation termed in the SAF approach as a “settled” action field (in our case an action field comprised local public-SNHSO collaborative relationships to provide human welfare services). But the COVID-19 crisis was so pervasive it introduced a profound “episode of contention” into all social action fields and consequently the SAF framework provides a persuasive account that captures the dynamic and contested and indeterminate impact of the pandemic on local fields of SNHSOs. Importantly, it better accounts for the temporal dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic, with positions in the field suddenly up for grabs and a collective renegotiation of the purpose, boundaries and “rules of the game” underway in a context of extreme urgency. At the same time, it alerts us to how SNHSOs are necessarily locked into complex webs of relationships with larger organizations (especially public sector) in the local strategic action field, and that powerful (usually larger) actors are likely to reassert their dominance over time. If nothing else, this cautions against overly optimistic extrapolation from the initial experiences of SNHSOs during the pandemic, while alerting us to their agency in reshaping the local strategic action field. Understanding (local) welfare systems in this way sets us up to better understand how best to support and engender a response to future crises. By applying this learning in other international contexts beyond the UK we can gain a deeper understanding of the dynamism of relationships during future periods of resettlement.

Although this was a relatively large empirical study that builds on previous pre-pandemic research into the role of SNHSOs in a contemporary welfare state context, it is important to reflect critically on its limitations. As we only undertook the research in four areas, our ability to generalize beyond these geographical areas or the English and Welsh context should not be overstated. Examples from other areas and jurisdictions would certainly have provided broader insights. Future qualitative research on this topic would also benefit from a more systematic comparative approach with similar numbers of larger (public, nonprofit, and private) providers. Further contextualized insights could also have been gleaned from research micro-sized nonprofits, including mutual aid groups, whose prominent role during the pandemic has been well documented.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aiken, M., & Harris, M. (2017). The “Hollowing out” of smaller third sector organisations. Voluntary Sector Review, 8(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080517X15090106925654

- Alvesson, M. (1989). The culture perspective on organizations: Instrumental values and basic features of culture. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 5(2), 13–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/0956-5221(89)90019-5

- Bambra, C., Riordan, R., Ford, J., & Matthews, F. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74, 964–968. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401

- Billis, D., & Glennerster, H. (1998). Human services and the voluntary sector: Towards a theory of comparative advantage. Journal of Social Policy, 27(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279497005175

- Bode, I. (2006). Disorganised welfare mixes: Voluntary agencies and new governance regimes in Western Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(4), 346–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928706068273

- Bovaird, T. (2014). Efficiency in third sector partnerships for delivering local government Services. Public Management Review, 16(8), 1067–1090. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930508

- Buckingham, H. (2009). Competition and contracts in the voluntary sector. Policy & Politics, 37(2), 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557309X441045

- Clifford, D., McDonnell, D., & Mohan, J. (2023). Charities’ income during the COVID-19 pandemic: Administrative evidence for England and Wales. Journal of Social Policy First View Online, 1, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279422001015

- Considine, M. (1988). The corporate management framework as administrative science: A critique. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 47(1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.1988.tb01042.x

- Dahlberg, L. (2005). Interaction between voluntary and statutory social service provision in Sweden: A matter of welfare pluralism, substitution or complementarity? Social Policy and Administration, 39(7), 740–763. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2005.00467.x

- Dayson, C., Baker, L., & Rees, J. (2018). The value of small: In depth research into the distinctive contribution, value and experiences of small and medium-sized charities in England and Wales. Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research.

- Dayson, C., Baker, L., Rees, J., Bennett, E., Patmore, B., Turner, K., Jacklin-Jarvis, C., & Terry, V. (2021). The ‘value of small’ in a big crisis: The distinctive contribution, value and experiences of smaller charities in England and Wales during the COVID-19 pandemic. Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research.

- Dayson, C., Bennett, E., Damm, C., Rees, J., Jacklin-Jarvis, C., Patmore, B., Baker, L., Turner, K., & Terry, V. (2022). The distinctiveness of smaller voluntary organisations providing welfare services. Journal of Social Policy, 1–21. FirstView publication online February 2022. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279421000970

- Dayson, C., & Damm, C. (2020). Re-making state-civil society relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic? An English perspective. People, Place and Policy Online, 14(3), 282–289. https://doi.org/10.3351/ppp.2020.5796569834

- DiMaggio & Anheier. (1990). The sociology of nonprofit organizations and sectors. Annual Review of Sociology, 16(1), 137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.001033

- Evers, A., & Laville, J. L. (2004). Defining the third sector in Europe. In The third sector in Europe, A. Evers & J. L. Laville. Edward Elgar (pp. 11–42).https://doi.org/10.4337/9781843769774.00006

- Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2011). Toward a general theory of strategic action fields. Sociological Theory, 29(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01385.x

- Fligstein, N., & McAdam, D. (2012). A theory of fields. Oxford University Press.

- Hansmann, H. B. (1980). The role of nonprofit enterprise. The Yale Law Journal, 89(5), 835–902. https://doi.org/10.2307/796089

- Harris, M., Halfpenny, P., & Rochester, C. (2003). A social policy role for faith-based organizations? Lessons from the UK Jewish voluntary sector. Journal of Social Policy, 32(1), 93–112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279402006906

- Hogg, E., & Baines, S. (2011). Changing responsibilities and roles of the voluntary and community sector in the welfare mix: A review. Social Policy & Society, 10(3), 341–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746411000078

- Kingma, B. R. (1997). Public good theories of the non-profit sector: Weisbrod revisited. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary & Nonprofit Organizations, 8(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02354191

- Kramer, R. M. (1994). Voluntary agencies and the contract culture: “Dream or nightmare?”. Social Service Review, 68(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1086/604032

- Langley, A. (1999). Strategies for theorizing from process data. The Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 691–710. https://doi.org/10.2307/259349

- Macmillan, R. (2013). Distinction in the third sector. Voluntary Sector Review, 4(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080513X661572

- Macmillan, R. (2020). Somewhere over the rainbow – third sector research in and beyond coronavirus. Voluntary Sector Review, 11(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080520X15898833964384

- Macmillan, R., & Rees, J. (2019). Voluntary and community welfare. In M. Powell, Ed. 2nd. Understanding the mixed economy of welfare, Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.56687/9781447333258-008

- Macmillan, R., Taylor, R., Arvidson, M., Soteri-Proctor, A., & Teasdale, S. (2013) The third sector in unsettled times: A field guide. Third Sector Research Centre Working Paper 109. Third Sector Research Centre.

- Milbourne, L., & Cushman, M. (2015). Complying, transforming or resisting in the new austerity? Realigning social welfare and independent action among English voluntary organisations. Journal of Social Policy, 44(3), 463–485. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279414000853

- Mitchell, G. E. (2018). ‘Modalities of managerialism: The ‘double bind’ of normative and instrumental nonprofit management imperatives. Administration & Society, 50(7), 1037–1068. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399716664832

- NCVO. (2022) UK Civil Society Almanac 2022. National Council of Voluntary Organisations. Retrievedonline on February 15, 2023. https://www.ncvo.org.uk/news-and-insights/news-index/uk-civil-society-almanac-2022/#/

- Rees, J., & Bynner, C. (2022). COVID 19 and the UK voluntary sector. (Dayson, C., Damm, C., & Macmillan, R., Eds). Policy Press.

- Rochester, C. (2013). Rediscovering voluntary action: The beat of a different drum. Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137029461

- Salamon, L. M. (1987) Of Market Failure, Voluntary Failure and Third-Party Government: Toward a Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations in the Modern Welfare State. Journal of Voluntary Action Research, 16(1–2), 29–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976408701600104

- Smith, R. S., & Lipsky, M. (1993). Nonprofits for hire: The welfare state in the age of contracting. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674043817

- Taylor, R., Rees, J., & Damm, C. (2016). UK employment services: Understanding provider strategies in a dynamic strategic action field. Policy & Politics, 44(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557314X14079275800414

- Weisbrod, B. A. (1986). Toward a theory of the voluntary nonprofit sector in a three-sector economy. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), The economics of nonprofit institutions (pp. 21–45). Oxford University Press.

- Young, D. (2000). Alternative models of government-CSOs sector relations: Theoretical and international perspectives. Nonprofits and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 29(1), 149–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764000291009