?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study analyses the current supporting laws, regulations, strategies, national action plans, NDCs, scientific literature and other documents and policies in Vietnam to identify the barriers against the effective implementation of mitigation and adaptation agriculture activities committed in Vietnam’s NDC. It also identifies the redundancies and synergies between climate action and green growth plans of the country. As a result, the study found that there is a strong supporting legal framework for implementing NDC actions in Vietnam. However, challenges and gaps are identified in awareness and technical capacity; coordination and resource allocation; downscaling to the provinces; engagement of private sector and NGOs; regulatory framework, which are critical to NDC implementation. A set of key recommendations are proposed on how to address the challenges raised by identified barriers are developed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In October 2016, the Government of Vietnam ratified the National Action Plan on Paris Agreement Implementation to realize the country’s commitment as stated in the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Vietnam unconditionally committed to reduce by 8% its GHG emission by 2030 relative to the business as usual (BAU) levels and aims to achieve a 25% reduction conditional to international support. After a desk review, comparative analysis with similar countries in the region and key informant interviews, the study found that there is a strong supporting legal framework for implementing NDC actions in Vietnam. However, challenges and gaps are identified in awareness and technical capacity; coordination and resource allocation; downscaling to the provinces; engagement of private sector and NGOs; regulatory framework, which might affect the NDC implementation in Vietnam.

Competing Interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

1. Introduction

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) is the core of 2015 Paris Climate agreement that aims to limit the global warming from 1.5 to 2°C above pre-industrial levels. NDCs delineate a set of actions for each country intends to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and adapt to climate change (Amjath-Babu et al., Citation2018). Given the critical role of NDCs in determining the final outcomes on mitigation and adaptation goals at global level, is crucial to understand the barriers in their implementation and identifying the possible way outs. The current work aims at a systematic analysis of the impediments in achieving the agricultural part of NDC in Vietnam. The country ratified the Paris Agreement and unconditionally committed to reduce by 8% its GHG emission by 2030 relative to the business as usual (BAU) levels and aims to achieve a 25% reduction conditional to international support.

Agricultural emissions (62.5 Mt CO2eq) accounted for 23% of total greenhouse gas emissions (270.3 MtCO2e) in the country in 2014 (World Resources Institute [WRI], Citation2017). It is expected that the share of agricultural emissions may reduce to 15% by 2030 (BUR1, Citation2014). Within the agricultural sector, irrigated paddy production (around ≈50%), enteric fermentation (≈10%), manure management (≈10%), and direct and indirect emissions from agricultural soils (≈25%) are the major sources. Despite to the prospective of prominent decline of national aggregate emissions, the reduction of those from agricultural sector can be crucial in achieving the NDC commitments, as energy sector is expected to bear only the 4.4% of the unconditional target and the 9.8% of the conditional target (GEA, Citation2017).

It is also important to note that Vietnam is highly vulnerable to climatic changes in the form of rainfall deficit in drier months, excess rainfall in rainy months and the sea level rise. It is expected that Vietnam could face 2–3°C increase in average temperatures and 78–100 cm raise in sea levels by the end of the century without any hydraulic drainage (World Bank, Citation2011). Such a sea level can inundate 39% of Mekong Delta reducing 40% rice production in the region. Large-scale loss of agricultural area is expected in other provinces as well (up to 10%) (TNA-Vietnam, Citation2012). Given the large-scale impacts of climate change due to GHGs emissions, it is important for Vietnam to implement its NDC commitments to reduce the impacts through mitigation and adaptation actions and ensure food security. The National Strategy on Climate Change and the National Strategy on Green Growth are the major steps in this direction. Given the fact that the full-fledged implementation of the NDC starts in 2020, it is the right time to assess the legal environment, which regulates the effective NDC implementation and identify possible policy recommendations. Such an exercise is important to reduce wastage of scarce resources by avoiding redundancy of actions among the programmes and conflicts of interests (Charlery & Trærup, Citation2018). The considerations reached could be useful for directing implementation of NDC commitments by other countries as well. The current work is a step toward this direction, given its objectives:

Identify the technical, legal, institutional, economic and financial barriers in effective implementation of the agricultural NDC in Vietnam; and

Propose a portfolio of measures that can overcome the emerged barriers and lead to the achievement of NDC goals.

2. Methodology

This study is based on collected and analyzed relevant laws, policies, strategies, national action plans, NDCs, scientific literature and other documents. The content analysis of the existing legal and institutional frameworks aided in evaluating their potential for the NDC implementation in terms of awareness, knowledge and technical support, local and national coordination and resource allocation, downscaling of the NDC targets to scale-up implementation, engagement of private sector and development partners, and regulations for implementation, etc. In addition, the NDC is compared to other South East Asian and South Asian countries to widen the basket of options. Additionally, expert assessment and cross learning from other NDCs is used to augment the insights on the technical, legal, institutional, economic gaps and barriers for NDC implementation in the agricultural sector.

3. Implementation of the agricultural NDC—Mitigation

Based on the official dispatch No.7208/BNN-KHCN sent by Ministry of Agricultural Development (MARD) to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE), the NDC implementation plan for agricultural sector has mitigation and adaptation components. Under this official directive, the emission reduction commitment covers four sub-sectors such as crop production, livestock, fishery, and land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF). The total budget allocated for this activity is of 2.28 billion USD (50,740 billion VND) from various sources including the national budget, and contributions from the private sector and the community. The option with international support expands it to USD 3.46 billion with possible additional actions. The key components of Vietnam NDC from the agriculture sector are given in Table . The major sources of GHG emissions from agriculture is represented by methane emissions from paddy fields that depends mainly on water regime implemented (i.e., alternate wetting and drying (AWD), or the mid-season drainage). It is estimated that AWD technology can save up to 60 Mt CO2eq. of GHGs emissions by 2030 (TNA-Vietnam, Citation2012) but given the average efficacy of AWD method, a reduction of more than 20–30 Mt CO2eq can only be expected.

Table 1. Barriers to implementation of agricultural emission mitigation strategies suggested in the Vietnamese NDC

With regard to the livestock breeding, the only strategy to handle enteric fermentation, that account for about the 10% of the total emission, is the improvement of livestock feed quality. It is expected that the livestock feed improvement can reduce emissions by 7.90 Mt of CO2eq (TNA-Vietnam, Citation2012). This kind of management, can have implication on energetic sector reducing its emission (use of biogas for domestic use instead of wood). They are accounted in the 22.64 MT CO2eq by 2030 (TNA-Vietnam, Citation2012). No major actions to reduce soil based emissions (25%) are reported though agricultural waste recycling that can partly reduce synthetic fertilizer-based emissions. In Vietnamese technology needs assessment (TNA), these three technologies were prioritised using multi-criteria decision-making analysis (TNA-Vietnam, Citation2012). In case of LULUCF, the TNA exercise of Vietnam highlights sustainable forest management, afforestation and reforestation, and mangrove rehabilitation as possible actions in the LULUCF sector, which are also highlighted in NDC. Nevertheless, the rapid expansion of natural and plantation forests since 1990s, raised the share of forests to the 47.6% of the total land area in 2015. Further significant expansion of the forest area is indeed difficult (Cochard et al., Citation2016). The further expansion of forestry, depends of the value of timber and non-timber forest products as well as government policies. Given the fact that the expected agricultural emissions in 2030s is around of 110 Mt CO2eq, if LULUCF-based sequestration can be raised to 50–60 Mt CO2eq. and agricultural emissions can be brought down by 50%, the agricultural emissions will be nullified by LULUCF, which can be a target for the Vietnamese Government (NDC-Vietnam, Citation2015). Here also possibilities exist where agricultural interventions can support reduction of energy-based emissions. Production of third generation biofuels (like algal farming) that will not compete with food security goals can be a possible option. For instance, given the 0.5 million bpd (barrels per day) consumption of crude oil and potential of algal crude production rate of 0.5 barrel per ha from inland farms, conversion of 5% agricultural area can provide 50% of the crude needs (EESI, Citation2017). This option can be attractive especially in areas that face saltwater intrusion. Technology development and transfer can be a crucial aspect in realizing the potential of such transformative options. If the agricultural lands or forests can produce biofuel without competing with food production, further energy-based emissions can be offset.

When compared to Thailand, where more than 73% of emissions are related to energy sector, the mitigation activities are directed to energy including transport sector (NDC-Thailand, Citation2015). Similarly, Philippines that targets up to 70% emission reduction from BAU by 2030 conditional to financial and technology transfer, intends to use actions in energy, transport, industry and LULUCF sectors to achieve the goal (NDC-Philippines, Citation2015). There are no mitigation commitments for agricultural sector in Thailand or Philippines’ NDC. This is the pattern similar to countries like India. Indonesia concentrates on LULUCF sector while Malaysia projects biofuel use and development as a key mitigation action. It can be assumed that Vietnam envisages synergies of agricultural mitigation actions with food security and farm income. As the mitigation actions are not economically rewarded, co-benefits or economic viability can have a crucial role in upscaling of any given technology or intervention. Table lists the envisaged mitigation actions (agriculture), emission reduction potential and potential technical and social barriers.

4. Implementation of the agricultural NDC—Adaptation

Adaptation component includes eight sub-sectors (crop production; livestock; fishery; forestry; water resource; salt production; rural development; and natural disaster response, prevention and control). The major activities are: research in breeding to produce new varieties, which tolerate the climate change risks (rice, food crops, cash crops, forestry, cattle, and poultry); enhance agricultural production system [Integrated crop management (ICM), integrated system with animal, fish and farm (known as VAC in Vietnam), integrated food-energy systems (IFES), ecosystem-based adaptation (EBA)]; develop and scale up climate smart agriculture techniques; strengthen the weather and extreme events forecasting; enhance the management and conservation capacity of natural resource (water, forest, land, etc.); and improve and renovate the infrastructure to respond to climate change and natural disasters (dykes system, canals, sluices, reservoirs, etc.). The total budget for these actions is590 million USD (13.115 billion VND). The major aim is the transition to small scale bio-intensive farming. Nevertheless, similar to South Asian countries Vietnamese NDA emphasizes production over profit (Amjath-babu et al., Citation2018). It is to be noted if the adaptation costs are similar to Bangladesh on per ha basis, Vietnam may need 1.4 billion USD adaptation investment per year (Amjath-Babu et al., Citation2018). Given the fact that national and international support may prove inadequate given the adaptation needs, largescale autonomous adaptation strategy is required to enhance resilience. Value chain level interventions, especially a transition to processed and refined food products for export and domestic consumption that can enhance profitability of farming, have to be given adequate attention. Increasing the farmer’s share of the consumer dollar through value chain interventions can enhance the adaptation investment capacity of the farmers.

5. National climate change adaptation and mitigation regulations and goals

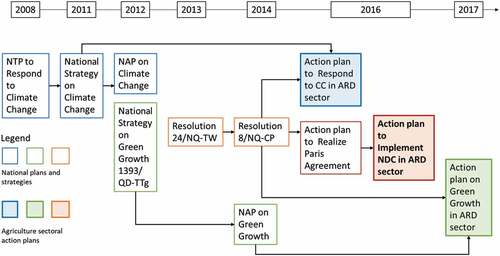

The National Strategy on Climate Change was issued by Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung in Decision No.2139 on 5 December 2011. MARD issued Decision No. 543 on 23 March 2011 to promulgate the Action Plan on Climate Change response of the agriculture and rural development (ARD) sectors from 2011–2015 and vision to 2050. This plan included 54 tasks of which only 21 tasks have been implemented with a total funding of 2.11 billion USD (47,180 billion VND). In 2012, the National Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation was developed as a guideline for sectors and provinces to develop their specific action plans. To revise and update the action plan for ARD sector, MARD Minister issued Decision No.819 on 14 March 2016 to promulgate the Action Plan from 2016 2020 and 2050 vision. Updating Action Plan indicated 73 tasks, including the activities for all sectors in general and specific activities for sub-sectors (crop production, livestock, forestry, and aquaculture), and 27 investment projects. The total budget estimated for this updated Action Plan was USD 2.16 billion (48,150 billion VND), in which the budget for climatic responses is USD 311.7 million (6,950 billion VND), and the budget for investment projects is USD 1.85 billion (41,200 billion VND). On 25 September 2012, the Prime Minister issued Decision No.1393 on the approval of the National Green Growth Strategy, which aimed to reduce the intensity of greenhouse gas emissions and to promote the use of clean and renewable energy. Two years later, on 20 March 2014, the Prime Minister issued Decision No.403 on the approval of the National Action Plan on Green Growth in the period 2014–2020. This action plan includes 47 activities with some specific ones directly related to agriculture and rural development. At the sectoral level, MARD issued Decision No. 923 on “Appointing the Responsibility to Implement Green Growth Action Plan of Agriculture and Rural Develop Sector to 2020” on 24 March 2017. The decision specified the tasks for agricultural sector regulated in the NAPGG covering 39 activities.

It can be seen that the mitigation tasks under the Action Plan on Climate change response of agriculture and rural development sector in the period 2016–2020 covers almost all the tasks indicated in the Agriculture NDC plan. The National Action Plan on Green Growth (NAPGG) listed the sources of the budget for each activity, including the state budget, socialized budget (from the private sector), community contribution, and international financial support. However, there is no breakdown of the budget for each activity, and no mechanism to allocate the state budget or attract the participation of private sector and international partners to implement the plan. As shown in Figure , there is no clear linkage between the three action plans in agriculture and rural development sector. Even though many activities indicated in the Agricultural NDC plan were also mentioned in the other two plans, there has been no harmonization of the NDC plan with climate change response plan and green growth plan to optimize funding and human resources in implementing these different activities.

Targets for 2011–2020: Reduce the intensity of greenhouse gas emissions by 8–10% as compared to the 2010 level; reduce energy consumption per unit of GDP by 1 to 1.5% per year (1.5 to 2% for 2020–2050); and reduce greenhouse gas emissions from energy activities by 10 to 20% (20 to 30% for 2020–2030) as compared to the business as usual case. These commitments include a voluntary reduction of approximately 10% (20% for 2020–2030), and an additional 10% (10% for 2020–2030) reduction with an additional international support. The strategy also stipulates that the People’s Committees of the different provinces and cities shall be responsible for formulating their respective programs and action plans that provide guidance in the implementation of green growth strategies; specify tasks; integrate into annual and 5-year economic-social development plans; and ensure funds for implementation at local levels. Resolution No. 24/NQ-TW of 6 June 2013 is intended to further enhance the mainstreaming of climate change and sustainable development in Vietnam while promoting the shift towards a model of green growth (see Green Growth Strategy below) (Ha, Citation2017). In order to do that, the resolution seeks to create favourable conditions for businesses to invest in green growth, with the government mandated to establish the legal framework and build specific policies to support business. Based on analysis of opportunities and challenges, the resolution set the direction and delegates responsibilities to realize immediate and long-term key tasks in response to climate change, resource management, and environment protection. The green growth strategies compliment the climate change action plan by including additional focus on renewable energy, circular economy approaches and biofuel production. It also emphasizes in research and development. Strengthening national systems of innovation is an important strategy to overcome technology deficits (Charlery & Trærup, Citation2018). Table compares the green growth plan with climate change action plan and suggests additional measures (from Amjath-Babu et al., Citation2018) that can be included in either of the plans.

Table 2. Barriers to implementation of adaptation strategies suggested in the Vietnamese NDC

Table 3. Comparative assessment of climate change action plan and green growth strategy of Vietnam

6. Implementation barriers and knowledge deficits

Based on the foregoing review of the key documents, challenges on the implementation of NDCs and deficits in the current knowledge have been identified in the areas of (1) awareness, knowledge, and technical capacity; (2) coordination; (3) downscaling; (4) engagement; and (5) regulatory. These are summarized in Table and explained in the following sections.

Table 4. Major challenges for NDC implementation in agricultural sector

6.1. NDC awareness, knowledge, and technical gaps

6.1.1. Lack of awareness and knowledge

Clar et al. (Citation2013) identified low awareness among policymakers as a key issue in implementation of mitigation and adaptation plans listed in NDCs. In Vietnam, the awareness of climate change mitigation measures, the Paris Agreement, and the NDC are very limited. This limited awareness and knowledge create a significant impediment to implement NDC plans. In contrast, government officials and communities have relatively good knowledge and understanding about climate change impacts. Based on the interviews with technical officials (i.e., crop production, livestock production, fishery, etc.), offices are focused on their technical mandate that excludes the implementation of climate change adaptation and mitigation measures. Despite the national plans, strategies, and policies formulated for responding to climate change, there is difficulties in developing detailed implementation procedures at a sub-national level. At present, most of provinces/cities have issued their Action Plan for responding to climate change; about one third of the provinces issued Action Plan on Green Growth and Action Plan on realization of Paris Agreement. However, most plans focus on responding to climate change in energy, transportation, and industrial sector, while climate change mitigation and adaptation in agriculture is still less detailed at provincial level. Hence, the agricultural adaptation and mitigation measures need to be mainstreamed in the relevant office’s mandate and programs. Capacity building on climate change issues and agricultural measures should be tailored the line of work of officials.

In addition, the limited awareness and knowledge of farmers and agricultural producers on climate change issues and measures have to be addressed for an effective NDC implementation. Farmers and agricultural producers need enhanced awareness and knowledge on climate change; climate change impacts on their crops; coping measures to such impacts; the contribution of agriculture to climate change; the measures to reduce the contribution of agriculture to worsening the climate change impacts; and also any opportunities brought by climate change (such as saline water for aquaculture). During discussions with experts, the need to enhance the knowledge awareness of farmers and agricultural businesses were emphasized to create a strong foundation for introducing and applying greenhouse gas emission mitigation technologies. It was suggested to adopt a “pull policy” (Incentives for farmers and agro-business to adopt technologies and practices that help mitigating GHG emission) as a prerequisite to entice farmers and agricultural businesses to implement the different NDC measures.

6.1.2. Insufficient technical capacity

Clar et al. (Citation2013) identified absence of adequate technological solutions to achieve adaptation and mitigation targets can often be a significant barrier. In case of major emission sources i.e., methane emissions from paddy, soil-based emissions and enteric fermentation of livestock, the technological options are limited. Another requirement of the mitigation technologies in agriculture is to have synergies with food security and it may preclude some mitigation technologies. Another constraint to the effective implementation of greenhouse gases inventory is insufficient technical infrastructure. Currently, there are only a few institutions capable of implementing the GHG inventory. Although many researchers proposed methodologies to conduct a GHG inventory in agriculture (i.e., rice production, livestock production, etc.), there are many challenges in developing a standardized methodology appropriate for the different agro-ecological zones. Measuring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) is a very important component in the NDC implementation. Respondents from the Institute for Agricultural Environment (IAE) noted that current MRV capacity is not enough to implement the NDC plan at the national level. IAE has been working as the leading agency in MRV for the agricultural sector, but the institute’s facilities, equipment, and human resources do not satisfy the requirements of MRV tasks, especially in complying with the UNFCCC-MRV Framework. It may need technology transfer and considerable research investment to tackle the issue. Possible use of atmospheric observations to infer GHG fluxes at subnational level can be explored to make sure of the quality of GHG measurements (Ganesan et al., Citation2018). For adaptation components, technical capacity is needed to develop to innovate the early warning system and to strengthen the irrigation and dyke infrastructure. Another barrier is the insufficient investment on scientific researches on new breeds of plants and animals, which can adapt efficiently with climate change impacts as well as the adaptive farming system.

6.2. Coordination and resource allocation

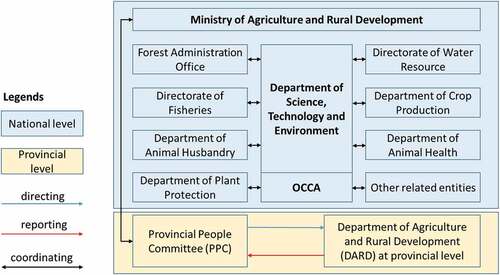

Another key challenge identified is the absence of a robust institutional frame to manage and coordinate the NDC implementation process. This void may lead to inadequate or unclear distribution of responsibilities (Clar et al., Citation2013) and act as a serious barrier to achieve the NDC goals. As Vietnam is currently revising the NDC plan, optimizing institutional arrangements can be a key mechanism for a successful implementation. Considering the different climate change action plans (Figure ) and MARD’s current organizational setup (Figure ), a review and harmonization of roles are needed to improve coordination. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) suggested that this should include strengthening the capacity of lead institutions to develop and implement NDC-related policies and programs, coordinating with sectorial line ministries, sub-national entities and engaging stakeholders in the NDC implementation process. According to the Decision No. 2053/QD-TTg issued by the Prime Minister on 28 October 2016, the government assigned MARD as the lead agency to collaborate with other ministries and agencies to implement the NDC plan for the agricultural sector. Department of Science and Technology (DOSTE) was assigned as the coordinating agency to work with departments under MARD in developing the NDC plan activities in different sub-sectors, including crop production (Department of Crop Production), irrigation (Directorate of Water Resources), LULUCF (Vietnam Forest Administration Office), livestock (Department of Animal Husbandry), and fishery (Directorate of Fisheries). Figure illustrates the organizational structure for implementing the Action Plan for the agriculture and rural development sectors in response to climate change.

Figure 2. Organizational structure for implementation of climate change policy in MARD (Rebugio & Ilao, Citation2016).

In the Official Dispatch No.7208/BNN-KHCN sent to MONRE on the Development of NDC Action Plan for Agricultural Sector, MARD assigned different tasks to its departments, but lacked directing, cooperating, monitoring, reporting, and verification mechanism. It can be envisaged that a specialized institution for NDC implementation is required to accomplish the coordination tasks. MARD need to consider appointing the Office for Climate Change Adaptation (OCCA) to be the coordinating agency for the NDC implementation with clear mandates and responsibilities. OCCA needs to synthesize the NDC activities from all sub-sectors, and develop detailed (sub-national) plan of activities and corresponding budgets from state and external sources. There is also a need to make sure that the budget allocation is in correspondence with mitigation potential and adaptation needs. For example, the activities to reduce irrigation in Coffee plantations may not be a mitigation activity that can be of national relevance though it is presented in various plans.

The ongoing review of the NDC Action Plan need to come up with an estimated budget for each activity and expected sources of funding (domestic or external). The amount of estimated budget has also identified the proportion of contribution from the private and the business sectors. But absence of clear guidelines for private sector participation and accounting its contribution can have implications in mobilizing private funds. Furthermore, it still lacks clear criteria for budget allocation mechanism. For example, the application of AWD irrigation for 200,000 hectares is assigned to the Department of Crop Production (DCP) with an estimated budget of VND 2 trillion (86 million USD) for this activity for 5 years. Given the fact that 5 tonnes of methane is produced per tonne of rice (Average production is around 5 tonnes per ha.) and the efficacy of AWD is around 50% in methane emission reduction, the proposed expenditure amounts 6.8 USD/tonne of CO2eq. emissions. Nevertheless, it is possible that farmer can gain a net revenue of 20 USD to 100 USD per ha per season by adopting the technology. Nevertheless, the source of the budget is not clear from the action plan. Tapping international carbon markets or creating domestic carbon markets after establishing clear MRV procedures can be an option for fund flows to mitigate the GHG emissions. The example of India in using an emission tax on coal and mandatory corporate social responsibility contribution (Amjath-babu et al., Citation2018) can be additional possible sources of revenue generation for mitigation and adaptation actions.

6.3. Downscaling the NDC to scale-up implementation

Clar et al. (Citation2013) proposes that insufficient knowledge-brokerage and networking can be a key impediment in implementation of the NDC targets. The Agricultural NDC needs the operationalization of the plan from the national level to provincial level, and from sectoral to sub-sectoral level. MARD tasked its departments and directorate to coordinate with the province in implementing the assigned activities. In case of DCP (department of crop production), it can prioritize the research and projects on climate change mitigation and adaptation such as new climate-smart varieties, and new cropping system suitable to new climatic conditions but implementing other activities can be a challenge such as water-saving irrigation, alternate wet and dry (AWD) method, and rice straw processing. In this case, DCP can develop a plan for these activities in collaboration with other departments and send it for the approval of the Department of Planning for budget allocation. It is likely that Department of Planning may disapprove or downscale the proposed activities depending on the government’s sectoral priorities reflected by the amount allocated for these activities in the central budget.

The implementation of NDC activities becomes more challenging with the absence of a planning mechanism in agricultural sector at the provincial level. The cost, benefits, and trade-offs when applying the new techniques; the investment required from the provinces; and the approaches appropriate when introducing, piloting, and upscaling are still unspecified. There is a need to clearly define the roles of the provinces and the national Project Management Unit. It should also be clarified how the NDC activities can be integrated into the provincial socio-economic development plan and provincial green growth plan. A new approach may be needed to delineate these roles and responsibilities and harmonize process. The model by Bangladesh Govt. which introduced a climate fiscal framework (CFF) that can balance the expenditure and supply of climate funds can be a possible path (Ministry of Finance, Citation2014). The Bangladesh government harmonized climate change spending with 37 different departments and assessed 13,000 budget codes. Efforts on similar lines are needed in Vietnam to harmonize budgetary allocations with NDC commitments.

6.4. Engaging the private sector and development partners

Almost all the legal documents emphasize the importance of the private sector and promote the participation of businesses and entrepreneurs in addressing climate change impacts. However, government still lacks support in encouraging participation of the private sector. In the implementation of all action plans, including the NDC plan, the government has not highlighted the incentives for the private sector to encourage them to participate in the implementation of climate change response activities. The current existing mechanisms regulated by the Decree 210/2013/ND-CP on Incentive Policies for Enterprises Investing in Agriculture and Rural Areas only provides a limited number of incentives and additional investment support of the State for enterprises which invest in agriculture and rural areas. It does not specify incentives for climate-smart agriculture or application of agricultural techniques that reduce GHG emission and enhance the response to climate change. Currently, there are some companies applying climate-smart agriculture (i.e. Loc Troi Group) for their production. However, they implement the techniques only to meet the needs of strategic project shareholders such as the IFC, the World Bank, international investment funds, and export markets, rather than to comply with the government’s roadmap. Private companies that tries working with the government for support/incentive to implement climate-smart agriculture model have to undergo long bureaucratic procedures. It indicates the need of simplifying bureaucratic procedures and introducing financial incentive mechanisms for private entities engaged in adaptation and mitigation activities.

The government can also take measures to oblige businesses to change their way of operating toward applying climate-smart technologies and practices, and contributing to GHG mitigation, by applying sanctions (Trinh, Citation2016). It can penalize non-compliance to certain emission standards in agriculture activities, require the adoption of climate-smart technologies for a specific time, and ban certain procedures or process detrimental to the environmental goals. Some of these rules may have been covered by existing rules, and could be reviewed for their applicability in supporting the Agricultural NDC implementation. Despite several regulations regarding international cooperation on climate change adaptation, green growth, and environmental protection, the development sector lacks an effective entry point for a coordinated response to climate change. Many development organizations within Vietnam (both International Non-Governmental Organizations and local Non-Governmental Organizations) currently working on climate change have expressed their support of the State in implementing the NDC plan, especially the National Adaptation Plan (NAP) within the agricultural sector. There are already several projects being implemented by NGOs across Vietnam in line with the proposed NDC plan. These initiatives can integrate into the Government implementation through improved information sharing between the NDC, implementing government agencies at the national level, and the NGO community. Furthermore, a working cooperation mechanism should be defined to identify the role of NGOs in implementing the NDC plan in the agricultural sector.

6.5. Regulatory gaps and challenges

Clar et al. (Citation2013) specifies that lack of experience in monitoring and evaluation practices can cripple measures such as NDCs. In The laws, strategies, and action plans are mainly for orientation at the national level, and not for orienting local and sub-sector levels. The current policies on climate change have very strong mandates but still lack implementing rules and regulations. The GHG emission reduction has been generally mentioned in all national strategies and action plans, but not yet comprehensively regulated in any law. The current legal documents do not specify responsibilities and roles of GHG emitters. Although the Law on Environmental Protection indicated that the government and local authorities should create a favourable condition to support individuals, institutions, and companies to mitigate GHG, the mechanism for incentives and/support for farmers, agricultural producers, and entrepreneurs to reduce the GHG emission has not been developed. The legal framework defining the emission reduction targets for province, and sub-sector (and company) needs to be developed. The Decree on roadmap and methodology for GHG reduction is being developed by MONRE and will be soon approved by the government, which is expected to act as the overarching guideline for mitigation efforts at national, provincial, and sectoral level. However, inconsistencies and overlaps among the different legal documents that could complicate the actions of implementing agencies need to be thoroughly addressed. The NDC Action Plan is the newest among the climate change responsive agenda at the national level, thus the need to align and synchronize it with NAPCCA and NAPGG. In 2017, the Prime Minister issued the Decision no.1670/QD-TTg on approval the Target Programme for Climate Change Adaptation and Green Growth for the period 2016–2020 as a merged action plan of NAPCCA, NAPGG and Action plan to implement Paris Agreement. The most recent action plan identified the target projects for climate change adaptation component and green growth component. It would be better for the implementation if the target projects will be fully developed with specific tasks for different sectors and regions.

7. Conclusions and recommendations

In general, Vietnam has a supportive national legal framework for the implementation of NDC. With many laws, national strategies, national action plans, and other legal documents, which are currently regulating and/or conducting similar activities for climate change mitigation and adaptation. Hence, the NDC plan has a strong legislative foundation for development and implementation. There are three major related programs working on climate change issues namely, the National Action Plan to Respond to Climate Change, the National Action Plan for Green Growth, and the National Action Plan to Implement NDC (Paris Agreement). The current work identified potential streamlining of the programmes by identifying the synergies and redundancies. At the sectoral level, MARD has also developed the action plan for the agriculture and rural development sectors. All those plans support Resolution No. 24/NQ-TW in actively responding to climate change and strengthening resource management and environmental protection. The overarching law that sets the basis for the implementation of NDC in the agricultural sector is the updated Law on Environment Protection issued by the National Assembly on 23 June 2014.

However, despite the above-mentioned favourable conditions, the implementation of agricultural NDC in Vietnam faces multiple challenges in terms of awareness and technical capacity, institutional coordination, planning and downscaling, stakeholder engagement, and regulatory issues (Table ). There is an urgent need to raise the awareness of government officials and communities. Mainstreaming NDC targets and activities as integral part of agriculture sectoral plans and programs with clearly specified the roles and responsibilities of each agency under a central coordinating agency (DOSTE) is needed in successfully implementing the NDC plan. Raising awareness could be implemented through campaigns, training courses, communication activities, and scientific seminars organized by DOSTE. Awareness-raising activities for farmers can be realized through the existing operated by MARD (i.e. VNSAT, World Bank project on Irrigated Agriculture Improvement), and other projects/programs in the field of natural disaster risk management and climate change response, or through mass media (i.e. Vietnam Television and Voice of Vietnam Radio).The content for awareness and information dissemination campaign for farmers, producers, and local officials should focus on the GHG mitigation and adaptation measures indicated in the Agricultural NDC Action Plan, and should be tailored to the specific needs of the target audiences. It should contain, among other things, suitable measures for their area, as well as details on when and where they can apply the measures. In this case, there is a need to identify the technical options for different agro-ecological zones, provinces, and communes. It is to be noted that perceived adaptation efficacy and perceived adaptation costs effectively determine the adaptation efforts (Le-Dang et al., Citation2014).

There is need to develop a comprehensive national MRV system and augment the capacity on MRV by enhancing the technical capabilities of the Department of Crop Production, Department of Livestock Production, Directorate of Fisheries, Directorate of Forestry, and other concerned agencies (e.g. Directorate of Natural Disaster Prevention and Control, Directorate of Water Resource). The officials from these departments and agencies need to be equipped with knowledge on NDC, GHG inventories, GHG measuring techniques, and reporting, in compliance with international procedures and requirements. An investment for improving and modernizing the infrastructure of the MRV, especially for measurement is needed to monitor the GHG emission and mitigation more accurately and to ensure the reliability of reported information. It can also be possible to develop atmospheric measures of gases like methane through international collaboration. When an MRV system is set up, it can be used by MARD to measure the progress in GHG mitigation of the other programs like Green Growth, Climate Change Adaptation, and Sustainable Production in Agriculture.

Set of feasibility studies on attaining Agricultural NDC goals at sub-national levels are required to develop a clear and comprehensive set of guidelines to translate contents of the NDC plan into specific activities/projects assigned to sectoral and provincial levels. The guidelines need to integrate various programmes such as socio-economic development plan, climate change action plan, green growth plan, etc and specify institutional arrangements. Having a clearly defined institutional arrangement for NDC implementation will provide a strong foundation for implementing the plan at both national and provincial levels. The climate fiscal framework (CFF) pioneered by Bangladesh can be a model institutional mechanism. An investment plan for the different components of the Agricultural NDC needs be developed and streamlined with potential funding from domestic and external sources (i.e. WB, ADB, GCF, NAMA facility). The development of CFF mechanism can be indeed helpful to attain the budgetary balance while achieving the goals. There is also a need of developing monitoring metrics for effective implementation and rewarding the effort.

It is to be noted that any activity can be strictly a mitigation of adaptation activity. Streamlining mitigation and adaptation actions can also be considered in agricultural sector. AWD supports reducing of water use and hence conservation of resources enhancing adaptive capacity. Biogas plants supports production of organic manure that can improve soil water holding capacity. Livestock feed improvement supports improving milk production and hence food security. In addition, LULUCF measures could improve timber and non-timer forests products-based income. There could be further possibilities to reduce emissions and enhance adaptive capacity if value chain level actions are considered but they are grossly missing in the agenda. Value chain level actions can also improve farmers’ investment capacity and support autonomous adaptation. Hence, the integration of NDC targets in the whole value chain as part of the good products standard and/or sustainability goals need to a major goal. Government agencies need to enable the private sector and NGO community to join forces in this endeavour as Vietnam is a leading agricultural exporter.

Similarly, adaptation activities with core social objectives that can prevent secondary impacts of climate change (Amjath-Babu et al., Citation2016) or foster landscape level adaptation are missing. India’s national employment guarantee scheme and Ethiopia’s productive safety net programme are guiding examples of such possibilities. In addition, crop insurance or weather insurance programmes that can enhance economic resilience of farmers are also to be considered in adaptation efforts. It can also be suggested that multi-country (South east Asia) weather insurance mechanisms can be considered given the climatic risk faced by south east Asian countries like Vietnam. It is to be noted that providing options to cushion climate-related health expenditure (e.g.: health insurance) along with protection of livelihood assets (e.g., weather insurance) can create resilient communities (Few & Tran, Citation2010). There is also a need to develop transformative adaptation options, especially in the wake of largescale seawater inundation in current rice farming areas. Transformative options such as sea algae farming for biofuel can be a possibility. Finally, there is a need to review the current regulations to provide a better regulatory framework and incentive mechanisms for investments. This could encourage the participation of farmers, the private sector, and other stakeholders in the NDC implementation of GHG mitigation. An improved and a more detailed regulatory framework could create a favourable condition for research, development, and investment to enable the uptake of recommended technologies and practices. Table summarizes the recommendations.

Table 5. Summary of recommendations that can address the identified barriers

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nguyen Duc Trung

The group of authors include Nguyen Duc Trung, Nguyen Trung Thang, Le Hoang Anh, TS. Amjath Babu, and Leocadio Sebastian. The authors have been collaborating with each other in various policy studies and researches in Vietnam under the framework of the CGIAR Research Program for Climate Change, Agriculture, and Food Security (CCAFS). CCAFS seeks to address the increasing challenge of global warming and declining food security on agricultural practices, policies and measures through strategic, broad-based global partnerships. The research program aims to define and implement a uniquely innovative and transformative research program that addresses agriculture in the context of climate variability, climate change and uncertainty about future climate conditions. Our research flagships are: Priorities and Policies for CSA; Climate-Smart Technologies and Practices; Low Emissions Development; Climate Services and Safety Nets; Gender and Social Inclusion; and Scaling Climate-Smart Agriculture. This study is under the research flagship on Priorities and Policies for CSA.

References

- Amjath-Babu, T. S., Aggarwal, P. K., & Vermeulen, S. (2018). Climate action for food security in South Asia? Analyzing the role of agriculture in nationally determined contributions to the Paris agreement. Climate Policy, 19(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1501329

- Amjath-Babu, T. S., Krupnik, T. J., Aravindakshan, S., Arshad, M., & Kaechele, H. (2016). Climate change and indicators of probable shifts in the consumption portfolios of dryland farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implications for policy. Ecological Indicators, 67, 830–838. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.03.030

- BUR1. (2014). Vietnam Biannual update report (BUR). UNFCC. December 2014. https://unfccc.int/documents/180728

- Charlery, L., & Trærup, S. L. M. (2018). The nexus between nationally determined contributions and technology needs assessments: A global analysis. Climate Policy, 19(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2018.1479957

- Clar, C., Prutsch, A., & Steurer, R. (2013, February). Barriers and guidelines for public policies on climate change adaptation: A missed opportunity of scientific knowledge‐brokerage. Natural Resources Forum, 37(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12013

- Cochard, R., Ngo, D. T., Waeber, P. O., & Kull, C. A. (2016). Extent and causes of forest cover changes in Vietnam’s provinces 1993–2013: A review and analysis of official data. Environmental Reviews, 25(2), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2016-0050

- EESI. (2017). Marine microalgae: The future of sustainable biofuel. Environmental and Energy Study Institute. https://www.eesi.org/articles/view/marine-microalgae-the-future-of-sustainable-biofuel

- Few, R., & Tran, P. G. (2010). Climatic hazards, health risk and response in Vietnam: Case studies on social dimensions of vulnerability. Global Environmental Change, 20(3), 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.02.004

- Ganesan, A. L., Stell, A. C., Gedney, N., Comyn‐Platt, E., Hayman, G., Rigby, & M., E. R. C. Hornibrook. (2018). Spatially resolved isotopic source signatures of wetland methane emissions. Geophysical Research Letters, 45, 3737– 3745. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/2018GL077536

- GEA. (2017). Implementation of nationally determined contributions: Viet Nam Country Report. The Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation. Building and Nuclear Safety.

- Ha, T. H. (2017). Proactively developing, implementing, inspecting and supervising the implementation of programs and plans to respond to climate change in each period. Vietnam Communist Review. Vietnam Communist Party's Central Committee. http://english.tapchicongsan.org.vn/Home/Culture-Society/2017/1047/Proactively-developing-implementing-inspecting-and-supervising-the-implementation-of-programs-and-plans.aspx

- Le-Dang, H., Li, E., Nuberg, I., & Bruwer, J. (2014). Farmers’ assessments of private adaptive measures to climate change and influential factors: A study in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Natural Hazards, 71(1), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0931-4

- Ministry of Finance. (2014). Bangladesh Climate Fiscal Framework. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.climatefinance-developmenteffectiveness.org/sites/default/files/publication/attach/Bangladesh%20Climate%20Fiscal%20Framework%202014.pdf

- NDC-Philippines. (2015). Nationally determined contribution of Philippines. Government of the Philippines. http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published%20Documents/Philippines/1/Philippines%20-%20Final%20INDC%20submission.pdf

- NDC-Thailand. (2015). Nationally determined contribution of Thailand. Government of Thailand. http://www4.unfccc.int/ndcregistry/PublishedDocuments/Thailand%20First/Thailand_INDC.pdf

- NDC-Vietnam. (2015). Nationally determined contribution of Vietnam. Government of Vietnam. http://www4.unfccc.int/ndcregistry/PublishedDocuments/Viet%20Nam%20First/VIETNAM’S%20INDC.pdf

- Rebugio, L., & Ilao, S. (2016). IRRI-SEARCA case study on institutional setting and process for vietnam’s climate change policy implementation. Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture.

- TNA-Vietnam. (2012). technology needs assessment for climate change mitigation - Synthesis report. Government of Vietnam. http://www.tech-action.org/-/media/Sites/TNA_project/TNA-Reports-Phase-1/Asia-and-CIS/Vietnam/TechnologyNeedsAssessment-Mitigation_Vietnam.ashx?la=da&hash=449103079474A2415D84000724947E3012880EFC

- Trinh, N. D. (2016). Policy gaps analysis for promoting investment in low emission rice production. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security - Southeast Asia.

- World Bank. (2011). Climate-resilient development in Vietnam: Strategic Directions for the World Bank, Sustainable Development Department, Vietnam country office. The World Bank.

- WRI (World Resources Institute). (2017). CAIT climate data explorer. World Resources Institute. http://cait.wri.org/profile/Vietnam