Abstract

The present study seeks to investigate the role of portfolios in EFL (English as a Foreign Language) writers’ metacognition as well as their writing skill. Therefore, the participants were assigned to two groups (experimental and control). The students in both groups received a writing test, a researcher-made Metacognitive Writing Questionnaire (MWQ), and a students’ attitude questionnaire for pre- and post-test. The experiment group was provided with specific guidelines and reflection sheets. The results indicated that portfolios significantly contribute to empowering both the metacognition and writing proficiency of EFL learners. As to the learners’ attitudes toward EFL writing assessment, it was generally revealed that portfolio students have a positive view of formative assessment, and teacher/peer feedback. The study suggests that not only can portfolios be used as assessing tools, but also they are indirect means of introducing self-reflection into writing courses.

Public Interest Statement

Over the past few decades, different scholars have talked about the importance of awareness of one’s mental processes. They have proposed that by making students aware of their thinking, they would understand their capabilities, and would also monitor and evaluate their learning process more effectively. With respect to foreign language writing, in particular, portfolio is a helpful tool that can be used to promote the learners’ awareness because it is a collection of students’ texts which showcases the process of their writing development.

In the present study, we show that how reflection on writing skills for EFL learners through portfolios may help them improve their metacognition or thinking about thinking process as well as their writing proficiency. There was also an attempt to show how such a reflection affects students’ attitude toward portfolios as an assessment tool.

1. Introduction

In recent years, ongoing and dynamic classroom assessments have been highly emphasized in educational, as well as EFL contexts since they are fundamentally learner-centered approaches with many positive effects on the learning process (Gipps, Citation1994). In addition, “there are increasing calls for involving participants in the learning process” (Ng, Citation2014, p. 3). This approach toward assessment and learning in educational settings is highly influenced by the Vygotskian view of learning and development (Lee, Citation2017). This view argues that individual development and learning have a social source, thereby new skills grow and develop within an enriched context where individuals extend their abilities through their interaction with more skilled members within the realm of their zone of proximal development (ZDP) (Vygotsky, Citation1980). This grand theory has contributed to a paradigm, called constructivism that views learners as active constructors of information in social negotiations (Ertmer & Newby, Citation1993). Within this conception, John-Steiner and Mahn (Citation1996), stated “by internalizing the effects of working together, the novice acquires useful strategies and crucial knowledge” (p. 192).

Among alternative forms of formative assessment is the portfolio which “is a purposeful collection of students’ works that demonstrates to students and others their efforts, progress, and achievement in given areas” (Genesee & Upshur, Citation1996, p. 99). With regard to the impact of portfolio assessment on target language writing proficiency, many have remarked that portfolio is a useful tool in helping students write better in FL (Foreign Language)/SL (Second Language) (Barootchi & Keshavarz, Citation2002; Lam, Citation2016). All in all, portfolio assessment can be a very useful tool to enhance FL writing provided that teachers train and employ it appropriately by considering the main features of a full portfolio (see the nine characteristics of portfolios in Hamp-Lyons & Condon, Citation2000).

It needs to be noted that portfolios should not be considered just a collection of materials produced by learners; rather, they provide comprehensive information about students and provide feedback on students’ performance (Rao, Citation2006). Moreover, as put forward by Jones and Shelton (Citation2011), portfolios are “a medium for reflection” (p. 21). It means that portfolios can encourage students to monitor and think about their learning process and evaluate their skill development. As Lam (Citation2018) highlighted, self-reflection plays a vital role in the promotion of learners’ autonomy as well. Moreover, Djoub (Citation2017), argued that portfolios can promote critical thinking since learners who engage in reflective writing are active agents who can make judgments and decide how they can improve their writing skills. Such an ability to reflect upon thinking is an issue which is highly related to metacognition.

Metacognition was clearly defined by Paul (Citation1993) as “thinking about your thinking while you are thinking to make your thinking better” (p. 91). It is noteworthy to mention that the very notion of metacognition is embedded in the social view of learning (Cross, Citation2010). Indeed, “central to awareness and self-regulation of higher mental functioning is that these attributes are enabled, transformed, and organized in socially situated activity which is mediated by auxiliary means” (Cross, Citation2010, p. 282). Accordingly, it seems that portfolio is fundamentally built upon sociocultural view of metacognition.

In recent decades, metacognitive strategies and their applications by effective SL/FL writers have been recognized by researchers (e.g. Flavell, Citation1979; O’Malley & Chamot, Citation1990; Wenden, Citation1998). For example, Victori (Citation1999), suggests that behind all strategies employed by successful language writers are metacognitive knowledge and these “informed decisions guide the choice of those strategies that best suit the demands, purposes, and constraints of the task” (p. 538). Along the same line, Devine (Citation1993) remarked that metacognitive awareness factors may even be more important than linguistic competence. Furthermore, Jones and Shelton (Citation2011) highlighted that the portfolio process “provides not only a means for internalizing learning at a deeper level, but also a means for developing and/or refining higher order thinking skills” (p. 25).

As Moya and O’Malley (Citation1994) suggest, learners’ involvement in the assessment process may result in an increase in their metacognitive awareness. Gottlieb (Citation2000) also notes that self-reflection and metacognitive strategies involved in portfolios “shape the students’ identity” (p. 97). In the same vein, Brown (Citation2004) implicitly refers to various potential benefits of portfolios among which reflection and self-assessment are related to metacognitive knowledge of the learners. Additionally, the effects of using portfolios on EFL autonomy have also been studied (e.g. Rao, Citation2006). While some research has been carried out on the connection between writing portfolio and EFL learners’ reflection and autonomy, no studies have attempted to focus on the special role played by portfolios in the improvement of metacognitive knowledge in particular.

Despite the agreement over the importance of the role of metacognition in learning, especially EFL learning, there is no consensus over the definition, categories, and subcategories of metacognition (See Brown, Bransford, Ferrara, & Campione, Citation1983; Flavell, Citation1979; Schraw & Moshman, Citation1995). However, the metacognition theory proposed by Flavell in the 1970s is considered to be well established. As Hongyun (Citation2008) notes, for Flavell, metacognition knowledge which regulates cognitive activities is of two dimensions: knowledge and experience. Flavell (Citation1987) expanded his theory and proposed that there are three distinct and highly interactive variables in metacognitive knowledge: “Person knowledge”, “Task knowledge”, and “Strategic knowledge”. As Yanyan (Citation2010) notes, person knowledge is the general understanding of individuals about themselves as learners. This may enhance learning or act as a barrier and inhibit it. Task knowledge is the knowledge an individual possesses regarding the task he is going to undertake. This is the information that helps the person manage the task. Strategic knowledge is the general knowledge which helps the individual to identify types of strategy he is going to use, evaluate their usefulness, and recognize their utility. Flavell’s influential theoretical taxonomy has been used in the present study to develop the MWQ.

The main reason behind the creation and development of the MWQ was a critical research gap in FL/SL writing studies in general and the portfolio studies in particular. That is, the majority of previous studies treat metacognitive ability in writing as a unidimensional ability and very few studies investigated the Flavell’s metacognitive subscales in FL/SL writing studies (Maftoon, Birjandi, & Farahian, Citation2014). Moreover, the measurement tools used in EFL writing studies are of a more abstract nature and seem to have little practicality for EFL writing pedagogy (e.g. Farahian, Citation2017). Taking these issues into account, we tried to address the above-mentioned research gaps that have also been noticed by Mak and Wong (Citation2017). As they remarked, “… there is a lack of empirical research on how students’ self-regulation can be effectively fostered in writing classrooms, and how the use of PA (Portfolio Assessment) [words added] can develop students’ self-regulated capacities” (Mak & Wong, Citation2017, p. 1). Moreover, many studies have merely targeted the positive impacts of portfolio writing and passed the important role of learners’ perceptions over and this aspect of portfolio received inadequate attention, especially in the EFL context (Lam, Citation2013).

Consequently, the current study is a further attempt to investigate the role of portfolio both in improving metacognitive knowledge in EFL writing and its critical role in the improvement of EFL learners’ essays. Based on Flavell (Citation1979), the deliberate activation of metacognitive knowledge is contingent upon learners’ conscious thinking when doing the task. Portfolio, therefore, may enhance learners’ metacognitive development (Yang, Citation2003). Furthermore, we aimed to compare the portfolio and non-portfolio EFL writers’ ideas about writing assessment so as to examine the impacts of the portfolio on both pedagogical and attitudinal levels. Accordingly, the following research questions were formulated:

| (1) | Does portfolio assessment have a significant effect on raising writing skills of EFL writers? | ||||

| (2) | Does portfolio assessment have a significant effect on raising metacognitive awareness of EFL writers? | ||||

| (3) | Is/are there any significant difference(s) between the portfolio and non-portfolio EFL writers’ attitudes toward writing assessment? | ||||

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The participants of this study consisted of 69 undergraduate TEFL (teaching English as a foreign language) students studying in a university in Kermanshah, a city in the west of Iran. The age range of the students was between 20 and 32. Besides, they were mainly in their third or fouth semesters. Based on the proficiency test, the students were spread over four levels of proficiency; elementary, pre-intermediate, intermediate, and advanced. Since the participants who were at the elementary level did fit into the purpose of the study, they were excluded due to the fact that they could not handle the tasks in the treatment. Moreover, some of the participants in the intermediate and advanced levels were also removed from the study since there was the concern that they had already developed their metacognitive writing ability (see Sasaki, Citation2000). Ultimately, out of the original pool (78), 69 students with pre-intermediate English proficiency participated in the study. They were randomly assigned to a control and an experimental group with 31 (10 male and 21 female) and 38 (13 male and 25 female) students, respectively. The two classes were two-credit “Writing” courses which were taught by the same instructor, and the data used in this research were gathered from the participants attending these classes.

It should be noted that only a few students had received writing instruction before attending university and while studying in university they only had taken a two-credit writing course.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Metacognitive writing questionnaire (MWQ)

The instrument designed for the study was developed by the researchers (Appendix B). The theoretical framework for developing the questionnaire was based on the Flavell’s (Citation1987) framework and Wenden’s (Citation1998) exposition of the concept. The following steps were taken to develop the questionnaire.

First, the related literature (e.g. Brown, Citation1987; Flavell, Citation1979; Schraw & Dennison, Citation1994; Schraw & Moshman, Citation1995; Yanyan, Citation2010) was carefully reviewed and the first pool of the items consisting of 64 items was compiled. Following this, to check the content validity of the questionnaire, some colleagues (TEFL PhD professors) were asked to pass their judgments on the statements. Afterward, the scale was revised based on the comments. As the next step, in a pilot study, 20 participants took the questionnaire and identified confusing items. They also left some comments on the draft of the questionnaire. After further revision, the final draft of the instrument was carefully checked by 5 experts in the field and the final version with 34 items created. Cronbach’s alpha was used to check the reliability of the questionnaire (0.76). The questionnaire was translated into Persian which is the native language of the participants to minimize the participants’ cognitive burden while completing the survey. This was also done to avoid any misunderstanding caused by the participants’ low proficiency level.

2.2.2. Essay tests

Together with the questionnaire, two short essay tests were also used (as a pre-test and a post-test). Since research has confirmed that writing proceeds much more easily on familiar topics than on unfamiliar ones (McCutchen, Citation2000), the students in both groups were asked to write short essays of 80–120 words for the pre-test and post-test on two different but familiar topics. For the pre-test, all the participants were asked to write an essay on “What are the characteristics of a good teacher?”, and for the post-test, they were asked to write an essay on “One of your best memories”. The texts were used as data to evaluate writing ability from the perspectives of “Content”, “Organization”, “Vocabulary”, and “Language Use” in an objective way (Jacobs, Zinkgraf, Wormuth, Hartifiel, & Haughey, Citation1981). Since time management is controlled by task metacognition and because the researchers were interested to study task metacognition we set a time limit of 45 min for the students to write the tasks. The participants wrote the essays in the classroom.

2.2.3. Student reflection sheet

An instrument was developed by the researchers to help the participants in the experimental group reflect on their learning process. The sheet (see Appendix A) consisted of two sections, namely the writing process (6 questions), and reflection on writing (5 questions). It was developed based on the related literature (Meltzer, Citation2010; Wright, Citation2010) and the researchers’ experiences. The questions presented in the sheets asked the participants to describe their writing performance, critique their performance, and focus on their future plans. It should be noted that in the “writing process” section questions 1 and 6 were in multiple-choice format (with the chance of writing further ideas). For the rest of the questions, we provided the students with open-ended questions (provided with some choices) so as to have students rely on their expressive writing skills (see, Meltzer, Citation2010). It was also essential for students to have a chance to write about their writing experiences in order to reflect more deeply on the process of their writing development and progress. On the whole, the first section of the sheet dealt with what was done during the writing process while the second section mostly dealt with students’ evaluations and forward-looking views and plans.

After the first draft of the reflection sheet was developed, it was revised based on two PhD colleagues’ comments. It was also modified after being completed by five students with similar proficiency level. Thereafter, the received comments and feedback helped us revise and finalize both the format and content of the reflection sheet.

2.2.4. Students attitude questionnaire

Following Lee (Citation2007), a set of questions were designed to assess participants’ ideas and attitudes about their writing assessment preferences (Appendix C). It should be mentioned that the content validity of the questionnaire was acknowledged by five TEFL professors. Although the questions were written in simple English, the participants answered the questions under the guidance of their teacher to prevent any misunderstanding.

2.3. Procedure

At the beginning of the study, the homogeneity of all the participants was determined through a proficiency test, namely Oxford Placement Test (OPT), and then the participants were randomly assigned to control and experimental groups. The participants were members of two classes taking a writing course. After the participants took the proficiency test, the classes were randomly assigned to experimental and control groups. The data related to those whose proficiency level was lower or higher than the intended purpose of the study was not included in the data analyses.

As the pre-test, both groups were given the MWQ together with an essay topic on “What are the characteristics of a good teacher?” Two instructors who were more proficient than others in teaching composition writing and had more experience than the other teachers were requested to score the papers based on a scale taken from Jacobs et al. (Citation1981). The results showed a .84 inter-rater reliability between the two raters. After one week, the treatment began and the experimental group went under its specific treatment, while the control group went through the conventional (non-portfolio) method of teaching writing.

One of the researchers who has a PhD in TEFL was the teacher of both classes. Each session the participants of both groups were assigned the same amount of writing tasks. They were required to write a short essay (80–120 words) on a familiar topic which seemed to be interesting and related to student’ needs and favorites. The participants’ agreement on the selected topics was considered as well. The classes were 12 90-minute sessions (once a week) in 12 consecutive weeks.

During the last week of the term, all students were post-tested with the same instruments used in pre-testing in the classroom. Finally, they completed a short questionnaire about their views concerning English writing assessment at the end of the writing courses. In the following lines, the steps taken in each of the non-portfolio (control) and portfolio (experiment) groups are described.

2.3.1. Control group

Each session, the participants in the control group wrote a short essay (which took around 45 min), on topics familiar the same as the ones given to the experimental group. Next, the teacher made some comments and gave written feedback within 2 days and then sent students the pictures of their texts via Telegram (an instant messaging service which is widely used in Iran). The types of feedback provided by the teacher were the same and addressed both form and content feedback (see, Ashwell, Citation2000) of the learners’ drafts. As an example of a form of indirect feedback, the teacher asked the participants to revise the agreement of verb and subject. As the type of content feedback, the teachers suggested that the sentence is incomprehensible.

Since a time limit of 5 days was imposed on the students to return their papers in the following session, the teacher made sure that the participants took the feedback seriously. The instructor gave credits to students for any revisions they made.

2.3.2. Experiment group

Meanwhile, the portfolio assessment was used for the experimental group. In each session, the students, like their counterpart in the control group, were required to write a short essay in class. Based on the feedback which was the same as the one given to the control group, the participants had to edit the first draft of their writing. In addition, the students had to reflect upon what they had done on the basis of the reflection sheet (Appendix A) given to them during the treatment. Before submitting the final draft of each essay, the participants were encouraged to analyze the quality of their writing by reflecting critically upon it so as to get aware of the patterns presented in the feedback and consciously apply them in the final draft of their essay. As a result, students in the portfolio group had enough time to think about their writings and polish them before coming to the class the next session. After handing in both their revised texts and reflection sheets, students had the chance to ask the teacher their questions and share their ideas and experiences with the class as well (around 20–30 min). In the meantime, the teacher gave oral feedback, where necessary, and provided the students with the chance of having peer discussions in order for students to receive feedback from their classmates as well.

It is noteworthy that the researchers were not interested in assessing and scoring students’ portfolio. Rather, they merely wanted to find out the effect of metacognitive awareness on improving students’ writing and how these issues help them enhance their writing ability; however, if students realized this, they would not have done their best. Accordingly, the teacher asked them to hand in their polished papers. That is why, at the end of the semester, students were asked to submit a portfolio of their works to their teacher so as to be evaluated and scored. In the portfolios, there were two polished papers (final drafts) together with the two drafts of each paper written, respectively, during the term. In the end, students selected the two papers which represented the best of their works. They were also encouraged to extensively revise these papers. All prewriting, drafts, and evidence of revisions for each of the two papers were included in the portfolio.

It should also be mentioned that at certain points throughout the semester, for both groups, the teacher directed the revisions by giving the participants awareness regarding certain strategies for combining sentences and organizing the text along with useful strategies to produce effective introduction, title, and also writing mechanics in general.

3. Results

3.1. Portfolio and EFL learners’ writing proficiency

As mentioned above, the scale proposed by Jacobs et al. (Citation1981) was used to rate students’ compositions. Table presents the descriptive statistics of the portfolio and non-portfolio groups one week before the treatment.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of control/experimental groups pre-test

As indicated in Table , the groups were much similar to each other in terms of their EFL writing proficiency. The following table illustrates the actual similarity between the groups.

Based on Table , there was no significant difference between the writing performance of learners in the control group and that of the experimental group. In other words, the findings obtained from inferential statistics acknowledge that the participants were homogeneous regarding their FL writing skills at the beginning of the study. The following tables report the findings of the writing post-tests.

Table 2. T-test for independent samples (writing task pre-test)

In general terms, there can be seen a difference between the portfolio and non-portfolio groups concerning the means of their writing scores after the treatment. In other words, the mean of the experimental group significantly exceeds that of the control group in post-test. To confirm the difference, a t-test was conducted as an inferential assessment (Table ).

Table 3. T-test for independent samples (writing task post-test)

According to Table , the difference illustrated in Table is statistically significant. In fact, the portfolio group’s EFL writing skills considerably improved after the portfolio treatment. Note that the results in the second row are included because the Levene’s homogeneity test was significant.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of control/experimental groups post-test

3.2. Portfolio and EFL learners’ metacognitive awareness

Based on the findings in Table , language learners in the control and experiment groups were not different with respect to their metacognitive awareness of EFL writing before the study.

Table 5. T-test for independent samples (metacognitive awareness pre-test)

Afterward, the effects of each of the three metacognitive factors (Person, Task, and Strategic knowledge) were checked one by one after the treatment to look into the changes occurred in students’ metacognitive awareness more closely. To do so, analysis of variance was run (See Table ).

Table 6. One-way ANOVA comparing person, task, and strategic knowledge

As it is shown, there is a significant difference between the Control and Experimental groups regarding Person and Strategic Knowledge, but there is no significant difference between the performances of the two groups concerning Task Knowledge. To put it another way, strategic knowledge has the highest level of impact (with an F equal to 56.08). The second highest impact belongs to Person Knowledge (with an F equal to 50.91). However, there is no significant level of impact for Task Knowledge (with an F equal to 2.11). In other words, there is no significant difference between the Control and the Experimental Groups in terms of their Task Knowledge.

To acquire the strength and magnitude of the obtained significant differences, Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated. Accordingly, the effect size for Person knowledge is 2.56 which is a large one. In addition, Strategic knowledge gained the effect size of 2.69 that is, again, a large effect.

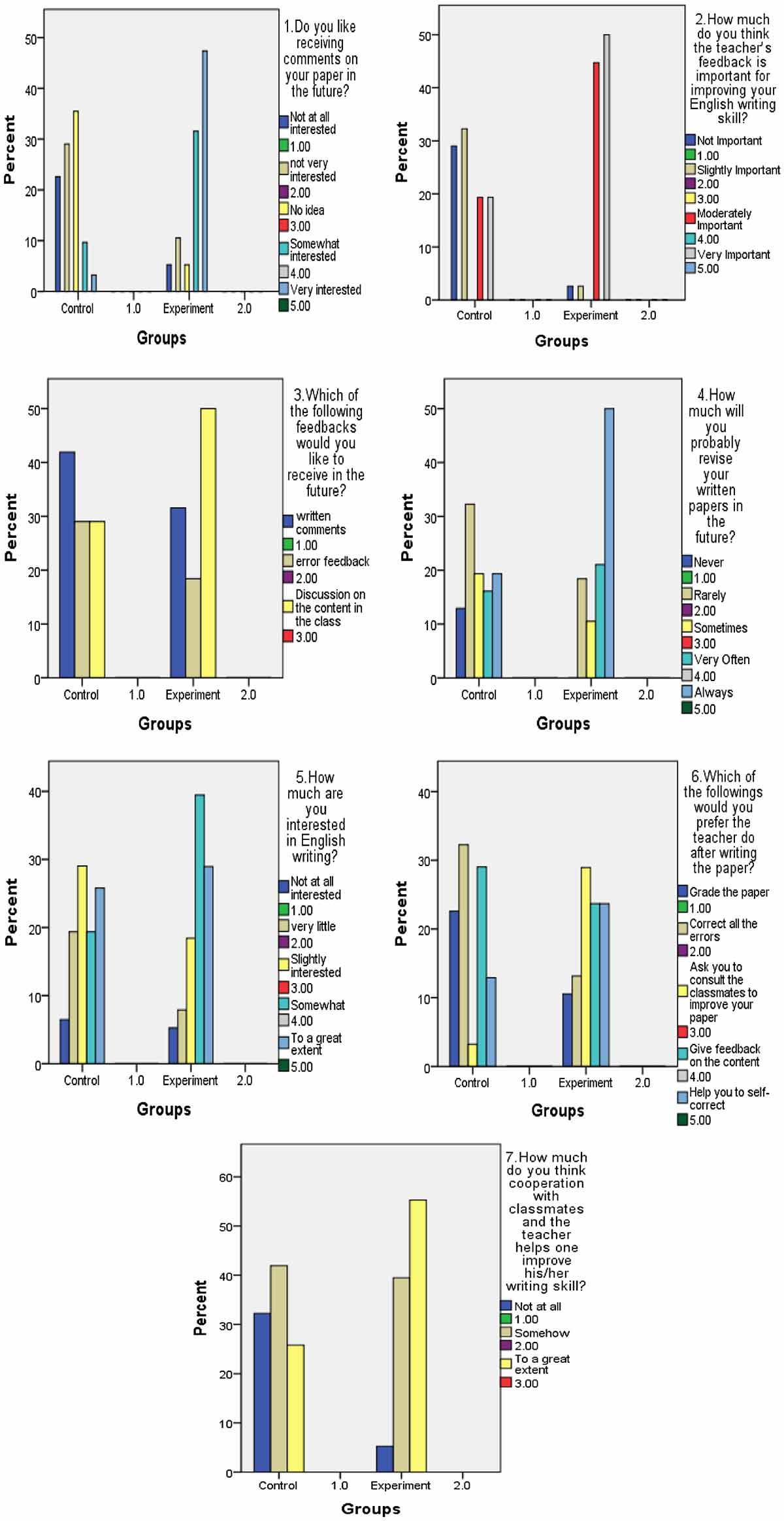

3.3. Portfolio and EFL learners’ attitudes

Besides tracking the changes in both writing and awareness of the EFL learners, we aimed to explore the participants’ attitudes toward English writing and writing assessment types. The preliminary findings are depicted in the graphs below. The results from inferential statistics are reported so as to give readers a more precise view as well .

.

As can be perceived holistically, the experiment (portfolio) group had a positive view of portfolio assessment in general, and its tasks and activities in particular. With regard to questions 1, 2, 4, and 7, this difference can be seen easier in comparison with the rest of questions. Finally, Mann–Whitney (Table ), and χ2 tests (Tables and ) were run in order to find out statistically significant differences for further interpretation.

Table 7. Mann–Whitney U nonparametric test for comparison of the groups’ attitude

Table 8. Pearson χ2 inferential statistics for the third and sixth questions

Table 9. χ2 residuals post hoc testing for Q6

As it is shown in Table , the differences were significant in terms of participants’ responses to the first, second, fourth, and seventh questions. In fact, EFL learners in portfolio group were more inclined to receive both teacher and peer feedback along with reflecting and revising their own writing drafts. Interestingly, no difference was found regarding the groups’ general interest in English writing.

Since questions 3 and 6 referred to the feedback and assessment categories, they underwent Pearson chi-square analysis. According to the Table , participants’ ideas about their preferred type of feedback were not significantly different. On the other hand, the groups had totally different preferences concerning the teacher’s writing assessments. To find out exactly which types of assessment were favored by the groups, we conducted a post hoc test for the obtained result from χ2 using the residuals (Table ).

Of all the responses, item C was the one which contributed the most to the significance level obtained in Q6 (see Table ). To put it simply, the learners in experiment group preferred peer assessment and feedback much more in comparison to their counterpart.

4. Discussion

As a response to the first research question, we found that the portfolio writing group outperformed the control group with regular writing instruction. This means that the produced texts of the students who experienced portfolio writing improved considerably from pretest to post-test in terms of both structure and content-related dimensions of EFL writing. This is in harmony, in particular, with the findings of Barootchi and Keshavarz (Citation2002) and Nezakatgoo (Citation2011) studies in the Iranian context. The results of studies in other contexts (Chinese, Canadian, and Turkish) also corroborate the obtained results of the study (Armstrong, Citation2011; Baturay & Daloğlu, Citation2010; Li, Citation2010).

Although many studies have acknowledged that portfolio enhances FL writers’ skills, it is yet to be shown how this improvement happens (Mak & Wong, Citation2017). On the other hand, some studies did not support the positive impacts of portfolios since learners were confused about the purpose of the portfolio and their teachers’ written feedbacks (Patthey-Chavez & Ferris, Citation1997). It seems that various types of feedbacks (both written and verbal) along with classroom conferences may reinforce the benefits of portfolio instruction and assessment.

Regarding the obtained results for the second question of the study, a caveat is in order. Although metacognition is separately teachable (Serra & Metcalfe, Citation2009), the present study suggests an indirect means of giving extended practice and reflection through portfolios to EFL writers to get command of the metacognitive awareness in their writings which is in line with Belgrade (Citation2013) who found that there is a chance in every stage of portfolio writing to engage in metacognitive thinking. Based on the findings, if properly employed, portfolios can foster EFL learners’ metacognitive awareness. This is in line with Schraw (Citation1998) who recommends teachers to give learners extended practice and reflection to incorporate metacognitive knowledge in FL writing courses. It can also be inferred from the findings that the development of metacognition is developmental and not static. It is a process in which learners should continuously plan, monitor, and check their progress. Therefore, teaching and learning metacognitive awareness cannot be considered a one-shot effort.

With regard to the three types of metacognitive awareness of writing, it was found that learners’ person and strategic knowledge improved considerably through the portfolio treatment. The former means that portfolio could enhance EFL writers’ self-awareness as learners. This is understandable since portfolio writers got an ongoing teacher and peer feedback on one hand and self-reflected their works on the other hand, and thus their progress in writing was well documented and evidenced in their portfolios. As to the critical role of reflection, the Faculty Learning Community (Citation2015–2016) stated “reflection provides the evaluator with a much better understanding of who students are because through reflection students share how they feel about or make sense of their learning experiences” (p. 1). All of these activities seem to have influenced the person knowledge improvement due to the fact that they had the experience of such an enriched formative self-assessment during their writing course.

Moreover, portfolio students’ strategic knowledge has concurrently upgraded as well. Although both groups were provided with useful strategies at certain points during the writing courses, the portfolio group’ strategic knowledge enhanced significantly. It may be due to the fact that the students reflected more deeply on their texts via reflection sheets and thus they became more aware of the suitable strategies that can help them finalizing their drafts. Surprisingly, no difference was found in terms of task knowledge. This may be due to the abstract nature of the writing tasks which did not differentiate between the control and experimental group. In fact, the task metacognition or procedural knowledge is a difficult construct to assess. Therefore, future studies are essential in this regard.

As a further investigation to the impacts of portfolios, we employed an attitudinal questionnaire so as to answer the third question regarding the difference between the groups. What motivated us to do so was based on the notion that reflection can alter one’ perception (Usher, Citation1985). It was revealed that the portfolio group’s tendency to receive comments and feedbacks (Q1 & Q2) was almost twice as much as the control group’ inclination. By the means of ongoing feedbacks, students not only can track their improvement, but they also become more metacognitively aware while planning and writing their subsequent drafts. In this regard, Lee (Citation2017) stated “students need feedback that consists of concrete, specific information about their progress with reference to the learning goals/success criteria so that they know how to proceed with their writing” (p. 114). Although Q3 showed no statistically significant difference concerning the type of preferred feedback, the portfolio group tended to have more interest in discussing and analyzing their texts in class. By contrast, non-portfolio students preferred teacher’s written feedbacks (see the bar graph of Q3).

Regarding the type of correction that learners preferred (Q6), we found that the portfolio group was significantly inclined to peer assessment. It means that they have a positive view of peer feedback in general and do not get anxious when they are corrected by their classmates. Lam (Citation2013) acknowledged that students in working (processed-based) portfolio group have positive view of peer feedback and even benefited more from this type of feedback. Students’ attitude toward classroom cooperation (both with teacher and classmates) in portfolio group was also positive in comparison to their counterpart (Q7). This is not surprising due to the fact that portfolio group viewed the peer feedback as a useful tool. Moreover, the socially situated essence of portfolio writing may have enhanced students’ motivation to cooperate with others.

The finding related to Q4 showed that EFL students in the non-portfolio group showed notably much less interest to revise their texts in comparison to the other group. It is again understandable since the regular writing instruction in the non-portfolio group did not necessitate text revisions. In fact, non-portfolio students settled for the things they were supposed to do in the regular writing class and did not go beyond the product-oriented writing assignments.

Interestingly enough, the participants in the groups were not significantly different regarding their general interest in English writing (Q5). This shows that the obtained positive impacts of the portfolio on both writing proficiency and metacognitive awareness of writing were not mediated by the higher motivation of the experiment group before the treatment. Although the bar graph of Q5 shows that a larger percentage (around %30) of portfolio students was highly interested in English writing, the difference is not significant. The slight difference may be due to the encouraging characteristics of portfolio assessment among which is the learner-centered nature of portfolios. This motivation booster characteristic of the portfolio is acknowledged by Tagg (Citation2003).

Generally speaking, many studies found that portfolio students have a positive attitude toward portfolio writing (Barootchi & Keshavarz, Citation2002; Prasad, Citation2003; Yang, Citation2003; Yilmaz & Akcan, Citation2012) which are in line with our findings. However, some studies remarked students’ dissatisfaction since they get confused regarding both feedbacks and purposes of portfolio tasks and consider portfolio writing as a demanding and time-consuming work (Chen, Citation2006; Struyven & Devesa, Citation2016; Williams, Citation2005) which push them out of their comfort zone (Bevitt, Citation2014). Notwithstanding, these issues can be controlled since portfolios are flexible and can be time-efficient and more encouraging (Jones, Citation2012). In our view, learners’ needs assessment can help in this regard because in this way teachers can diagnose the gaps and encourage students to follow the portfolio instructions.

5. Conclusion

As a critical element of portfolio instruction, metacognition plays a vital role both directly and indirectly. The direct role was revealed from its positive impact on metacognitive awareness of writing. It also helped learners improve their writing by the means of reflection in the self-assessment phases of portfolio assessment. To put in another way, the use of MQW with the three subscales informed us of how portfolios can facilitate EFL writing from the metacognitive point of view which is at the heart of this type of writing instruction.

Thereupon, it seems necessary to encourage teachers to take the role of metacognitive awareness more seriously, especially when they employ portfolio as a toolkit for writing courses. In this regard, many helpful suggestions can be found in the literature. For instance, Schraw (Citation1998) recommends a method that comprises four steps. It begins with introducing metacognitive strategies into the classroom which includes giving learners an awareness regarding the important role of metacognition, enabling them to improve their knowledge of cognition, teaching them to regulate their cognition, and providing a meaningful context for the promotion of metacognitive awareness. Despite the benefit(s) that learners gain from such a method, especially in writing courses, the metacognitive and reflective skills are rarely taught, specifically in the educational contexts where test-driven and output-oriented approaches are valued. On top of that, the employment of portfolios needs time and expert teachers to implement the strategies in classrooms and thus especial portfolio training is vital in pre-service teacher training courses (Lam, Citation2015).

Moreover, in some EFL writing course contexts (e.g. Zhang, Citation2003) EFL teachers teach in the same way that they have been taught and show little interest in incorporating metacognitive strategies in the classrooms. This problem is a big challenge, especially in the East Asian context in which test results and summative assessment are typically valued (Lam, Citation2015). According to Lee, “most in-service teacher training may not include instruction on how to give effective written feedback to students, let alone how to align teaching, learning and assessment of writing through formative feedback” (as cited in Lam, Citation2015, p. 11). Fortunately, due to the flexibility of portfolio assessment, this type of instruction can be adjusted based on the dynamic nature of FL classrooms where contexts, culture, learners’ needs, and proficiency level can be notably different. In this regard, teachers should take their students’ needs, ideas, and complaints seriously; otherwise, “the learning potential of the tasks is compromised” (Struyven & Devesa, Citation2016, p. 131). That is why the participants’ ideas toward writing assessments were also explored in the present study.

As some recommendations for further studies, we suggest further investigations on some critical issues so as to bridge the existing research gaps. First and foremost, the role of metacognition in portfolio writing should become clearer. This can be done by investigating different metacognitive constructs and factors in order to capture the usefulness of metacognition in an objective manner. Moreover, to strengthen the results, the interview may help scholars track the trajectory of metacognitive support during the journey of portfolio writing as a formative type of assessment. Secondly, future studies with in-depth investigations using longitudinal research designs can help researchers observe and examine the development of FL writing skills more closely. The reason for this suggestion is that portfolio is a multifaceted type of instruction within which learning and assessment are intertwined.

Although we attempted to fill some research gaps, some other critical questions and issues remained unaddressed. There were no ongoing observations or interviews in this study as to how textual improvements have happened. Moreover, the sample size was small and this, per se, could lower the generalizability of the findings. Nevertheless, what can be gained as a take-home-message is that metacognitive awareness in writing is quite essential for text improvement and thus this ability should be fostered in writing classrooms by promising techniques such as portfolio writing.

Funding

The authors received no direct funding for this research.

Cover image

Source: http://www.softicons.com/web-icons/practika-icons-by-dryicons/portfolio-icon which holds a freeware image license and the co-author Farnaz Avarzamani.

Corrigendum

This article was originally published with errors. This version has been corrected. Please see Corrigendum (https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1462549).

Acknowledgment

We greatfully acknowledge helpful pieces of advice provided by Dr Paul Barrett concerning the data analysis of the study, we thank Mr Ali Ahmadi (Department of ELT, IAUKSH) for language editing of this manuscript. Many thanks also go to the reviewers for their comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Majid Farahian

Majid Farahian is an Assistant Professor of Applied Linguistics at Islamic Azad University (IAUKSH), Kermanshah, Iran. His main research interests are foreign language writing, metacognitive awareness in FL writing, and the study of plagiarism in EFL settings.

Farnaz Avarzamani

Farnaz Avarzamani holds MA in TEFL and is an English teacher in Kermanshah, Iran. Her areas of interest include educational psychology and language education.

References

- Armstrong, C. L. (2011). Understanding and improving the use of writing portfolios in one French immersion classroom. Ontario Action Researcher, 11(2), 1–29.

- Ashwell, T. (2000). Patterns of teacher response to student writing in a multi draft composition classroom: Is content feedback followed by form feedback the best method? Journal of Second Language Writing, 9(3), 227–257.10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00027-8

- Barootchi, N., & Keshavarz, M. H. (2002). Assessment of achievement through portfolios and teacher-made tests. Educational Research, 44(3), 279–288.10.1080/00131880210135313

- Baturay, M. H., & Daloğlu, A. (2010). E-portfolio assessment in an online English language course. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(5), 413–428.10.1080/09588221.2010.520671

- Belgrade, S. F. (2013). Portfolios and e-portfolios: Student reflection, self-assessment, and global setting in the learning process. In J. H. McMillan (Ed.), Sage handbook of research on classroom assessment (pp. 331–346). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Bevitt, S. (2014). Assessment innovation and student experience: A new assessment challenge and call for a multi-perspective approach to assessment research. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(1), 103–119.

- Brown, A. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. In F. E. Weinert & R. H. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and understanding (pp. 65–116). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Brown, A. L., Bransford, J. D., Ferrara, R. A., & Campione, J. C. (1983). Learning, remembering, and understanding. In P. H. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Cognitive development (4th ed., pp. 515–529). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

- Chen, Y. M. (2006). EFL instruction and assessment with portfolios: A case study in Taiwan. Asian EFL Journal, 8(1), 69–96.

- Cross, J. (2010). Raising L2 listeners’ metacognitive awareness: A sociocultural theory perspective. Language Awareness, 19(4), 281–297. doi:10.1080/09658416.2010.519033

- Devine, J. (1993). The role of metacognition in second language reading and writing. In J. G. Carson & I. Leki (Eds.), Reading in the composition classroom: Second language perspectives (pp. 105–127). Boston, MA: Heinle and Heinle.

- Djoub, Z. (2017). Enhancing students’ critical thinking through portfolios: Portfolio content and process of use. In C. Zhou (Ed.), Creative problem-solving skill development in higher education (pp. 235–259). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.10.4018/AHEPD

- Ertmer, P. A., & Newby, T. J. (1993). Behaviorism, cognitivism, constructivism: Comparing critical features from an instructional design perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 6(4), 50–72.

- Farahian, M. (2017). Developing and validating a metacognitive writing questionnaire for EFL learners. Issues in Educational Research, 27(4), 736–750.

- Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906–911.10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

- Flavell, J. H. (1987). Speculations about the nature and development of metacognition. In F. E. Weinert & R. H. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation and understanding (pp. 21–29). Hillside, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- FLC. (2015–2016). Active learning, metacognition & the E-portfolio in 1st year & transfer learning experiences. Teaching Deep Reading & Information Literacy in GE & Major Gateway Courses, 1–7.

- Genesee, F., & Upshur, J. A. (1996). Classroom-based evaluation in second language education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gipps, C. V. (1994). Beyond testing: Toward a theory of educational assessment. London: Falmer Press.

- Gottlieb, M. (2000). Portfolio practices in elementary and secondary schools: Toward learner-directed assessment. In G. Ekbatani & H. Pierson (Eds.), Learner directed assessment in ESL (pp. 89–104). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Hamp-Lyons, L., & Condon, W. (2000). Assessing the portfolio. Principles for practice, theory and research. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

- Hongyun, W. (2008). A longitudinal study of metacognition in EFL writing of Chinese university students. CELEA Journal, 31(2), 87–92.

- Jacobs, H. L., Zinkgraf, S. A., Wormuth, D. R., Hartifiel, V. G., & Haughey, J. B. (1981). Testing ESL composition: A practical approach. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

- John-Steiner, V., & Mahn, H. (1996). Sociocultural approaches to learning and development: A Vygotskian framework. Educational Psychologist, 31(3–4), 191–206.10.1080/00461520.1996.9653266

- Jones, J. (2012). Portfolios as “learning companions” for children and a means to support and assess language learning in the primary school. Education, 40(4), 401–416.

- Jones, M., & Shelton, M. (2011). Developing your portfolio-enhancing your learning and showing your stuff: A guide for the early childhood student or professional. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

- Lam, R. (2013). Two portfolio systems: EFL students’ perceptions of writing ability, text improvement, and feedback. Assessing Writing, 18(2), 132–153. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2012.10.003

- Lam, R. (2015). Convergence and divergence of process and portfolio approaches to L2 writing instruction: Issues and implications. RELC Journal, 46(3), 1–16. doi:10.1177/0033688215597119

- Lam, R. (2016). Taking stock of portfolio assessment scholarship: From research to practice. Assessing Writing, 31, 84–97. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2016.08.003

- Lam, R. (2018). Promoting self-reflection in writing: A showcase portfolio approach. In A. Burns & J. Siegel (Eds.), International perspectives on teaching the four skills in ELT: Listening, speaking, reading, writing (pp. 219–231). Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Lee, I. (2007). Students’ reactions to teacher feedback in two Hong Kong secondary classrooms. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17, 144–164.

- Lee, I. (2017) Portfolios in classroom L2 writing assessment. In: Classroom writing assessment and feedback in L2 school contexts (pp. 105–122). Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3924-9_8

- Li, Q. (2010). The impact of portfolio-based writing assessment on EFL writing development of Chinese learners. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 33(2), 103–116.

- Maftoon, P., Birjandi, P., & Farahian, M. (2014). Investigating Iranian EFL learners’ writing metacognitive awareness. International Journal of Research Studies in Education, 3(5), 37–51. doi:10.5861/ijrse.2014.896

- Mak, P., & Wong, K. M. (2017). Self-regulation through portfolio assessment in writing classrooms. ELT Journal, doi:10.1093/elt/ccx012

- McCutchen, D. (2000). Knowledge acquisition, processing efficiency, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational Psychologist, 35, 13–23.10.1207/S15326985EP3501_3

- Meltzer, L. (2010). Promoting executive function in the classroom. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Moya, S. S., & O’Malley, J. M. (1994). A portfolio assessment model for ESL. The Journal of Educational Issues of Language Minority Students, 13, 13–36.

- Nezakatgoo, B. (2011). The effects of portfolio assessment on writing of EFL students. English Language Teaching, 4(2), 231–241.10.5539/elt.v4n2p231

- Ng, F. S. D. (2014). Complexity-based learning – An alternative learning design for the twenty-first century. Cogent Education, 1(1), 970325. doi:10.1080/2331186X.2014.970325

- O’Malley, J. M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.10.1017/CBO9781139524490

- Patthey-Chavez, G., & Ferris, D. (1997). Writing conferences and the weaving of multi-voiced texts in college composition. Research in the Teaching of English, 31(1), 51–90.

- Paul, R. W. (1993). Critical thinking: Fundamental to education for a free society. In J. Willsen & A. J. A. Binker (Eds.), Critical thinking: What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world (3rd ed.). Santa Rosa, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking.

- Prasad, N. (2003). Portfolio assessment in secondary education: The case of one school in Hong Kong (Unpublished MEd dissertation). University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.10.5353/th_b2705706

- Rao, Z. (2006). Helping Chinese EFL students develop learner autonomy through portfolios. Reflections on English Language Teaching, 2, 113–122.

- Sasaki, M. (2000). Toward an empirical model of EFL writing processes: An exploratory study. Journal of Second Language Writing, 9, 259–291.10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00028-X

- Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26, 113–125.10.1023/A:1003044231033

- Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460–475.10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

- Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351–371.10.1007/BF02212307

- Serra, M. J., & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Effective implementation of metacognition. In D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. C. Graesser (Eds.), Handbook of metacognition and education (pp. 278–298). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Struyven, K., & Devesa, J. (2016). Students’ perception of novel forms of assessment. In G. T. L. Brown & L. R. Harris (Eds.). Handbook of human and social conditions in assessment (pp. 129–141). Taylor & Francis.

- Tagg, J. (2003). The learning paradigm college. Bolton, MA: Anchor Publishing.

- Usher, R. (1985). Beyond the anecdotal: Adult learning and the use of experience. Studies in the Education of Adults, 17(1), 59–74.10.1080/02660830.1985.11730447

- Victori, M. (1999). An analysis of writing knowledge in EFL composing: A case study of two effective and two less effective writers. System, 27, 537–555.10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00049-4

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. London: Harvard University Press.

- Wenden, A. L. (1998). Metacognitive knowledge and language learning. Applied Linguistics, 19(4), 515–537.10.1093/applin/19.4.515

- Williams, J. (2005). Teaching writing in second and foreign language classrooms. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

- Wright, G. A. (2010). Improving teacher performance using an enhanced digital video reflection technique. In J. Spector, D. Ifenthaler, P. Isaias, & S. D. Kinshuk (Eds.), Learning and instruction in the digital age (pp. 175–190). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Yang, N. D. (2003). Integrating portfolios into learning strategy-based instruction for EFL college students. IRAL, 41, 293–317.

- Yanyan, Z. (2010). Investigating the role of metacognitive knowledge in English writing. HKBU Papers in Applied Language Studies, 14, 25–46.

- Yilmaz, S., & Akcan, S. (2012). Implementing the European language portfolio in a Turkish context. ELT Journal, 66(2), 166–174.10.1093/elt/ccr042

- Zhang, L. J. (2003). Research into Chinese EFL learner strategies: Methods, findings and instructional issues. RELC Journal, 34(3), 284–322.10.1177/003368820303400303

Appendix A.

Reflection sheet

Name: _____________________

Date: ______________________

Essay No.: ___________________

Reflections on your writing Process

Please think about the following questions and answer them in the process of writing your essay. Keep a copy of your reflections in your portfolio for further reference by you and your teacher.

You are free to write in English or in Persian.

Section 1: The writing process

| (1) | Did you plan or prepare an outline for your essay before starting to write?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

If yes, how do you think an outline may help you have a better piece of writing?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

(2) Did you think about the followings while writing?

| • | content | ||||

| • | organization | ||||

| • | vocabulary | ||||

| • | grammatical or spelling errors | ||||

| • | spelling | ||||

If yes, how do you think having close attention on the points helped you have a better piece of writing?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

(3) Did you have a draft of your essay? If yes, how did it help you?

————————————————————————————

(4) Did you correct the …?

| • | grammar | ||||

| • | Vocabulary | ||||

| • | Content (if you have clearly expressed your ideas) | ||||

| • | Organization of the paragraph(s) (how you have put together sentences and paragraphs) | ||||

| • | spelling | ||||

When did you do the correction? (While writing, after the first draft was prepared, or after the final draft was prepared? Explain your answer——————————————————

(5) Did you revise the essay in terms of the content, organization, vocabulary, grammar, spelling or…….after you finished writing? Why/why not?

—————————————————————————— ——————————————————————————

(6) Did you get help from your classmates, the teacher, the Web, etc.? If yes, what kind of help you received?

……… helped me with

| • | Brainstorming | ||||

| • | Organizing the essay | ||||

| • | Finding suitable vocabulary items or expression | ||||

| • | The structure | ||||

| • | The content or conveying the meaning | ||||

——————————————————

Section 2: Reflection on writing

(1) Do you think you have tried your best in writing this essay? Why or why not?

(2) Do you consider it a good piece of work? Why or why not?

| • | Comment on the positive points of your essay. | ||||

| • | Comment on the negative points of your essay and what you need to do to improve it. | ||||

(3) How do you find your progress in writing in English compared to the last time you wrote an essay?

| • | Outstanding | ||||

| • | Very good | ||||

| • | Satisfactory | ||||

| • | poor | ||||

(4) Can you predict what kind of problems (structural, meaning, vocabulary) you may have in the next essays?

(5) How are you going to solve the problems you had in writings?

Appendix B

Metacognitive writing questionnaire

Appendix C

| (1) | Do you like to receive comments on your paper in the future? | ||||

| (2) | How much do you think the teacher’s feedback is important for improving your English writing skill? | ||||

| (3) | Which of the following feedbacks would you like to receive in the future? | ||||

| (4) | How much will you probably revise your written papers in the future? | ||||

| (5) | How much are you interested in English writing? | ||||

| (6) | Which of the followings would you prefer the teacher do after writing the paper? | ||||