Abstract

The present study aimed at investigating the effect of using collaborative translation tasks (CTTs) for teaching figurative language. The study also sought to explore the perceptions of the learners toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language through conducting interviews. The participants of the study included 60 English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners at the intermediate level who were randomly divided into an experimental and a control group each consisting of 30 learners. Next, a figurative language test developed by the researchers was administered to the two groups as pretest. Following that, the experimental group received CTTs for learning figurative language as treatment. As for the control group, no treatment was given and the participants and the teacher simply followed the conventional method of teaching based on the syllabus of the institute. After the treatment, the participants in both groups were given the figurative language test administered to them before the treatment as posttest. Moreover, 10 learners in the experimental group were also interviewed to explore their perceptions toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language. The results of statistical analyses indicated that the experimental group receiving CTTs outperformed the control group in terms of figurative language learning. Moreover, the results of the interviews indicated that overall the participants held positive attitudes toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language. Based on the findings, teachers are encouraged to use CTTs to teach figurative language.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Shall we use the mother tongue when teaching or learning a foreign language? Millions of people around the world are learning English as a foreign or second language and it is often heard that the use of mother tongue in classes where a foreign language is being taught has a negative point. In this perspective article, we have shown that the use of mother tongue (Persian) was of benefit to learning English. Apart from the use of mother tongue, the present article also highlights the fact that when students work together in the classroom, better learning takes place. In this article, we have also reported some interviews with the learners and came to the conclusion that the participants held positive attitudes toward the usefulness of both the use of mother tongue and working together. Therefore, we encourage the use of mother tongue and working together when learning a foreign language.

1. Introduction

As discussed by Kövecses and Szabó (Citation1996), figurative language is the most difficult field of foreign language learning to both teachers and learners. Historically, figurative expressions were considered equal to fixed idiomatic expressions when it came to second language learning. Accordingly, as Chen (Citation2010) mentions, memorization was viewed as the most commonly recognized way to learn and acquire such expressions. In accordance with the contemporary theories of cognitive linguistics, the current perspective toward figurative language is that figurative expressions serve as a reflection of the conceptual system regarding how L2 users think and act (Lakoff & Johnson, Citation1980). This suggests a systematic motivation for learning the meanings of figurative expressions (Kövecses, Citation2001).

To make L2 figurative language learning easier and more effective, cognitive linguists recommend that L2 learners increase their awareness of the semantic motivation underlying figurative expressions (Boers & Lindstromberg, Citation2006) instead of strictly memorizing their fixed forms. Learners’ comprehension of the meanings associated with figurative language is facilitated through drawing on learners’ L1 via translation exercises (Chen, Citation2010). Due to the introduction of various progressive methods related to language teaching, translation exercises have been marginalized, leading to a lack of attention to improving instruction through translation. This shortcoming is affirmed by Cook (Citation2010) who takes issue with the fact that neither practice nor research has considered translation exercises seriously. Cook (Citation2010) goes on, inquiring why the idea that translation activities/exercises interfered with successful acquisition never came under question. Can it be claimed that the effects of translation just seemed too self-evident to deserve investigation?

In fact, many scholars have sought to challenge the factual question that why Grammar Translation method came under attack so harshly, ultimately resulting in its disappearance in the field of English Language Teaching (ELT) (Abdullah, Citation2013). They say that the criticisms leveled against the Grammar Translation method were superficial and not necessarily scientifically warranted. These researchers demanded a focus on translation and its incorporation in L2 learning programs. As claimed by these scholars, the effect of translation exercises on different aspects of language learning need to be carefully analyzed and their long-term impacts determined.

The topic of some recent discussions in English as a Foreign Language (EFL) circles is whether or not translation and L1 should be incorporated in EFL contexts (Cook, Citation2010). As discussed by Cook (Citation2010), over the years, translation had an important role to play in ELT classrooms. Yet, with the introduction and widespread use of communicative methodologies, translation came to lose its relevance. Second language learning through drawing on first language has been examined by different researchers (e.g., Banos, Citation2009; Stanley, Citation2002). The findings have consistently indicated that L2 learners who have lower proficiency can reap better benefits when L1 is employed in the process of learning L2. As mentioned earlier, one dimension of language which can possibly be improved through the use of translation is figurative language. Translation exercises and tasks like other tasks can be performed individually or collaboratively.

As Al Odwan (Citation2012) has asserted, collaborative learning (CL) has to do with small groups of learners, helping one another to accomplish their goal and to complete the activities by enacting their role responsibly. Thanks to the application of this teaching strategy, L2 learners assume responsibility of both their own learning and that of their classmates to increase their knowledge. A review of the literature reveals that during the last century, efforts have been aimed at developing some CL theories. This was intended to facilitate designing an instructional framework of CL. Luckily, these theories have been in parallel with discussions on how best we can push learners to assume a more active role in their studies and inspire them to have more control over their own learning.

Throughout the world, a lot of studies and scholars have examined the concept of CL. Especially, researchers including Johnson and Johnson (Citation1992) and Kagan (Citation1994) have carried out their studies on this concept. Although the results of these studies may turn out to be conflicting in some points, they have provided insights on how CL unfolds in the classroom (Johnson & Johnson, Citation1992; Kagan, Citation1994). There have also been many studies addressing CL in the Iranian setting of ELT (e.g., Biria & Jafari, Citation2013; Haji Jalili & Shahrokhi, Citation2017; Tabatabaei, Afzali, & Mehrabi, Citation2015).

Haji Jalili and Shahrokhi (Citation2017) explored the effect of collaborative writing on Iranian EFL learners’ l2 writing anxieties and attitudes. The results revealed that collaboration led to the reduction of learners’ writing anxiety rates. Furthermore, it was found that the participants had a positive attitude toward collaborative writing.

Biria and Jafari (Citation2013) carried out a study to examine the impact of collaborative writing on the writing fluency of Iranian EFL earners. The findings indicated that CL did not contribute to the enhancement of writing fluency of the participants. Tabatabaei et al. (Citation2015) investigated the effect of collaborative work on improving speaking ability and decreasing stress of Iranian EFL learners. The results revealed that the participants in experimental group outperformed the control group in terms of speaking ability. Also, the results showed that the participants in experimental group had less stress after doing collaborative activities. The analysis of the responses to a questionnaire measuring learners’ attitudes toward collaborative leaning demonstrated that the participants had positive attitudes toward CL.

Thus, given the problems associated with learning figurative language and the possible contributions of the use of L1 in learning L2 in general and the contradictory results of the previous studies concerning CL, the present study aimed at investigating the effect of the use of collaborative translation tasks (CTTs) for teaching figurative language. Therefore, the hereunder research question was formulated:

RQ1: Does the use of collaborative translation tasks significantly affect learning figurative language?

RQ2: What are the perceptions of Iranian EFL learners toward the efficacy of collaborative translation tasks for learning figurative language?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

To accomplish the objective of the study, 60 male and female intermediate learners within the age range of 24 to 38 were selected non-randomly out of an initial 90 learners from Safir Language institute in Tehran. The Preliminary English Test (PET) was administered to the initial 90 participants and the results were used to select those participants whose scores fell within the rage of one standard deviation above and below mean. The 60 learners were randomly divided in two groups each consisting of 30 students in two classes. Moreover, 30 students with similar characteristics to the participants of the study participated in the piloting phase of PET as well as the figurative language test designed for the purpose of the present study. There were also two experienced EFL teachers with at least 15 years of teaching experience who rated the speaking and writing sections of the PET.

2.2. Research site

The current study was conducted in one branch of a private language school called Safir Language Academy in Tehran. The school was established in 1999, and at the time of conducting the research, it had 20 branches in Tehran and 34 branches in other cities of Iran. The school employed 900 (male and female) English teachers, and over 30,000 students were attending its classes. Out of the 20 branches in Tehran, 1 was the center for teaching French and 2 other for the preparation for IELTS examination, and the remaining 17 branches exclusively offered English courses. The classrooms in Safir are all equipped with DVD-players, LCD sets, and audio systems. Most of the classrooms have built-in cameras and microphones, which facilitates supervisory classroom observations. Supervisors can observe live classes through the monitor in the management room, or they can observe the classes later, as all video/audio data of all classrooms are automatically saved to a computer hard disc. Each classroom is large enough to seat 17 students comfortably. The maximum number of students in every classroom in Safir is 17. Seats in all classrooms are arranged in a U-shape, so that while everyone can face the teacher, interaction among students is facilitated and the teacher can easily move around the classroom.

3. Instruments

3.1. PET

A proficiency PET was administered to select a homogenous sample of participants with respect to their language proficiency. PET, the Cambridge Preliminary English Test, is a qualification in EFL by Cambridge ESOL. The test has these sections:

Reading Writing are taken together—90 min

Listening—30 min

Speaking—an interview, 10 min

3.2. Figurative language test

A test consisting of 30 figurative items (Appendix A) was developed by the researchers to measure the learners’ performance on figurative language use. The test included 30 English sentences collected from dictionaries, a corpus (the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)) and the Internet. The instructions for the test were written in learners’ L1 (Persian) and asked the learners to read each sentence and determine whether the sentence contained a figurative expression, or whether thinking figuratively was prerequisite to understanding the sentence. The learners were also asked to underline the figurative expression in each test item. To make sure that the test had the required content validity, the researchers appealed to expert opinion and thus the items were reviewed by two MA holders in TEFL with 15 years of teaching experience and due revisions were carried out on the items. To assure that the test had an acceptable reliability index for the present research context, it was piloted on 30 learners having similar characteristics to the main participants and Cronbach’s Alpha was run on the scores. The reliability index turned out to be .82 which was considered satisfactory.

3.3. Figurative language materials

The content containing figurative language was taken from dictionaries, a corpus (COCA) and the Internet.

3.4. Semi-structured interviews

In order to explore the perceptions of Iranian EFL learners toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language, the researcher developed a list of 5 semi-structured interview questions (Appendix B) and administered them to 10 participants in the experimental group in order to answer the second research question of the study. The responses of the learners to the interview questions were analyses via content analysis procedures proposed by Auerback and Silverstein (Citation2003). According to Auerback and Silverstein (Citation2003), content analysis is the best form of analysis when dealing with qualitative data. They further enumerate six stages which should be followed in order to to come up with established, meaningful patterns. These phases include: getting familiar with data, coming up with initial codes, looking for themes among codes, reviewing the themes, defining and labeling the themes, and producing the final report. The six stages proposed above were taken into account to analyze and report the interview contents.

4. Procedure

Initially, a PET was piloted on 30 participants. Following that, the test was given to 90 EFL learners at the intermediate level. Then, based on the descriptive data, only those learners whose scores fell within the range of ± 1 standard deviation from the mean were selected as the homogenized participants of the study in terms of language proficiency. Following that, the 60 selected participants were randomly divided into two groups each consisting of 30 learners. Next, a figurative language test developed by the researchers was administered to the two groups as pretest. Following that, the experimental group received CTTs for learning figurative language as treatment.

CTT is a kind of indirect consciousness-raising task. In this kind of task learners in pairs or groups perform some operations on L2 data via using L1 in order to reach an explicit understanding of concepts they are exposed to. These tasks unfold in three steps:

Isolation of the linguistic feature or the intended concept under scrutiny for focused attention,

Explicit description and explanation of the concept in L1 through translation

Intellectual effort to internalize the feature and gain a better understanding of the concept under focus

In the same vein, in this study, the learners in the experimental group were provided with L2 data containing the target feature to translate to the first language in pairs or groups. Moreover, the learners could count on the teacher’s collaboration as well. In this study, learners were given short reading extracts from the Internet containing figurative language to translate into Persian. The steps taken in this group were as follows:

Learners were given excerpts of English texts in which some figurative language instances had been used

The teacher brought the attention of the learners to the linguistic feature by asking learners to underline the instances of figurative language used in the text

The teacher explicitly elaborated on the figurative language instances in the text

The teacher asked the learners to work in pairs or groups to translate the figurative language instances from English into Persian.

The teacher asked the participants to surf the net for the following session and bring a short text including some instances of figurative language. The learners were asked to work in pairs and at times in groups to translate the figurative language instances into Persian

As for the control group no treatment was given and the participants and the teacher simply followed the conventional method of teaching based on the syllabus of the institute. In the language institute the syllabus was mainly based on the course book. The book used was Touchstone authored by McCarthy, Mccarten, and Sandiford (Citation2008). This book consisted of 12 units and each unit included four parts as A, B, C and D. The book consists of the following activities in each unit:

Extensive speaking, pronunciation and vocabulary sections

Thorough grammar sections with clear examples and practice

Comprehensive listening activities with scripts

Contemporary, engaging reading materials taken from authentic sources

And finally, the Review and Practice pages at the end of the book for each unit which bring all the learning activities in particular grammatical points together.

It should be noted that in the course book there is no specific part or content dealing with translation or figurative language. Thus, the control group was not exposed to translation tasks of any kind or any explicit teaching of figurative language. The whole treatment lasted for 10 sessions. Each session of the class lasted 1/5 h. At the end, the participants in both groups were given the figurative language test administered to them before the treatment again as posttest the results of which were used to investigate the research question. Finally, 10 participants in the experimental group were interviewed to explore their perceptions toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language.

5. Results

5.1. Reliability analysis of the instruments (pilot study)

The first instrument in need of reliability check was PET which was needed for homogenizing the participants in terms of language proficiency. To this end, PET was administered to a pilot sample of 30 EFL learners and then Cronbach Alpha formula was employed for checking the reliability of listening and reading sections of PET and inter-rater reliability for speaking and writing sections of PET. Table displays the Cronbach’s Alpha of reading and listening sections of PET.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha report of reading and listening section of PET

Based on Cronbach’s Alpha analysis, reading and listening sections of PET had reliability indices above 0.70, which points to the acceptability of listening and reading sections in terms of reliability. Regarding writing and speaking sections of PET inter-rater reliability was computed. The inter-rater reliability was estimated by correlating the writing and speaking scores of the two raters who were chosen for this purpose. Tabl shows the results of correlation coefficient between the scores of the two raters.

Table 2. Inter-rater reliability of writing and speaking sections of PET

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha report of figurative language test

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of the initial pool of language learners on PET

The correlation between the raters showed that both writing and speaking sections had acceptable levels of reliability. The writing and speaking had reliability indices of 0.79 and 0.78, respectively. The dependent variable of the present study was learning figurative language which was measured though a researchers-made test. This test was piloted on the 30 EFL learners and its reliability was measured using Cronbach’s Alpha Formula. Table shows the descriptive statistics as well as the reliability report of the figurative language test.

Based on the descriptive statistics of the test, the pilot sample scored 14.26 (SD = 3.41) and the reliability of the test was found 0.82.

5.2. Selection of the participants

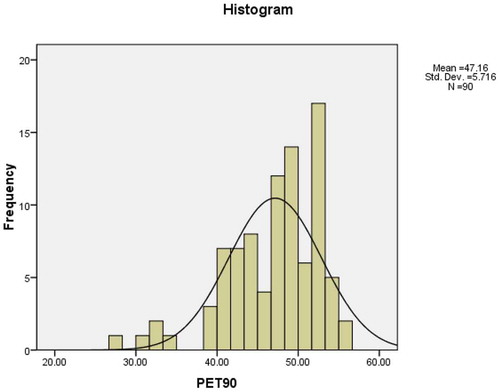

In order to minimize the effect of language proficiency on the outcome of the study, variation in the language proficiency of the participants was controlled. Therefore, a pool of 90 intermediate language learners was selected based on convenience sampling, and their PET scores were considered as a way to choose those with homogenized language proficiency. Table shows the PET score statistics for the 90 language learners.

Based on the results of PET, language learners had a mean score of 47.15 and standard deviation of 5.71 on PET. Figure shows the frequency of PET scores of the students.

In the next step, language learners whose scores were below or above ±1 SD were removed from the pool of 90 language learners so that only those learners with closest scores to the mean were selected as homogeneous participants. Table shows the descriptive statistics of the students with mean scores between ±1 SD.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics of the homogenized students on pet

After removing the learners with scores beyond ±1SD the mean score of the students was 47.93 (SD = 3.12). In the next step, these homogenized participants were further divided into two groups for the experimentation phase (receiving the treatment).

6. Addressing research question one

The present study sought to investigate if the use of CTTs significantly affects learning figurative language. To find the answer to this question, pretest and posttest (Figurative Test) scores of the experimental and control groups needed to be checked. Table shows the descriptive statistics for the pretest and posttest scores of the two groups.

Table 6. Descriptive statistics of the pretest and posttest scores

Based on descriptive statistics, the group receiving CTTs scored 14.56 (SD = 4.46) and the control group scored 14.16 (SD = 3.15) on pretest which suggests that the two groups had similar performances prior to the treatment. However, on posttest the experimental group scored 18.00 (SD = 3.57) while the control group scored 15.10 (SD = 3.38). Accordingly, a robust technique was needed to investigate the effect of treatment. The chosen method for analyzing data was ANCOVA which could allow the pertest scores to be taken into account when examining the difference between the performances of the two groups. However, since ANCOVA requires that data be normally distributed, it was not possible to run ANCOVA. Table shows the results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality for the pretest and posttest scores of the two groups of the study.

Table 7. The results of Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality for the pretest and posttest scores

As seen in Table , the pretest scores of the two groups and the posttest scores of the experimental group are not normally distributed (p ≤ 0.05) which means that ANCOVA is not suitable for the analysis. Accordingly, an alternative procedure was employed (i.e., gain score procedure). In gain score procedure, the pretest scores are subtracted from the posttest scores and the obtained scores are called gained scores. Then, the groups are contrasted in terms of gain scores and in case of any significant difference in gain scores, it can be claimed that there is a significant difference between the two groups in terms of the effect of treatment. Table shows the gain scores of the experimental and control groups.

Table 8. The gain scores of the experimental and direct control groups

Based on gain score statistics, experimental group scored higher (M = 3.43, SD = 2.68) than the control group (M = 0.93, SD = 1.38). To decide on the significance of the significant effect of treatment, Mann Whitney U test was run on the gain scores. The use of Mann Whitney U test was due to the fact that Kolmogorov-Smirnov test of normality indicated that gain scores were not normally distributed (p ≤ 0.05).

As seen in Table there is a significant difference between the two groups of the study (U = 176.50, p ≤ 0.05) which means that the experimental group outperformed the control group in terms of figurative language learning.

Table 9. Result of Mann-Whitney-U Test on gain scores

7. Addressing research question two

Since in social sciences experiments have inherent weaknesses, in order to further explore that the better performance of the learners in the experimental group has been due to the treatment, the researcher decided to explore the perceptions of Iranian EFL learners toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language through conducting interviews.

Overall, the participants believed that teaching figurative language via CTTs helped them learn figurative language more effectively. Moreover, most of the participants commented that CTTs were interesting for them. All of the participants expressed willingness to receive such instruction for other language components in their future courses. The participants believed that working together and the use of their mother tongue had helped them learn figurative language which had consequently led to their improvement in terms of figurative language. As for the point they liked most about the CTTs, the participants mentioned that the collaborative nature of the instruction helped them reduce their anxiety and also the use of their mother tongue had also helped them understand the materials.

8. Discussion

The present study aimed at investigating the effect of the use of CTTs for teaching figurative language. The study also sought to explore the perceptions of Iranian EFL learners toward the efficacy of CTTs for learning figurative language through conducting interviews. The results of statistical analyses indicated that the experimental group receiving CTTs outperformed the control group in terms of figurative language learning. Moreover, the results of the interviews indicated that overall the participants held positive attitudes toward the efficacy of CTTs.

The findings of the current study regarding the positive effect of using translation tasks are in congruence with previous studies indicating the positive role of the use of L1 in learning L2. Banos (Citation2009) conducted an investigation on the contribution of first language in L2 leaning. The results showed that the native language plays a facilitating role in second language learning. He asserts that the application of mother tongue is warranted as far as it is effective for students. Moreover, Banos claims that using L1 as long as it is justified has a motivating impact.

Stanley (Citation2002) performed a study on a multilingual class of learners. In her study, the learners were categorized into groups with the same first language so that they could engage in communication with each other. This makes it possible for the participants to help their peers. Stanley only spoke English in the class. Those learners who had no peers in class with respect to their first language quit quickly. The learners with the L1 support groups held on till the end of the course.

L1 use will cause L2 learners to feel more comfortable and motivated to take risks. Scholars (e.g., Banos, Citation2009; Stanley, Citation2002) have put emphasis on the application of first language during the instruction, making it possible to check how some learners understand the instruction. In the majority of the arguments given by researchers regarding the use of first language in language learning classes, it is generally agreed that L1 provides a familiar and effective way of quickly assisting the learners in understanding the concepts much better (Levine, Citation2003). Cook (Citation2001) has put forth several areas where L2 teachers can include mother tongue into L2 learning. Moreover, he maintains that teachers can use their first language to teach various concepts with the aim of helping the learners to better understand the targeted concepts. He continues that L1 use can save the time and effort needed by the teachers to instruct the rules and vocabulary. According to Atkinson (Citation1987; as cited in Bouangeune, Citation2009), the use of L1 might be beneficial in the instruction of L2. He says that translation is favorable to learners, and it encourages them to disclose their feelings regarding the points they may not understand very well.

The findings of the current study concerning the effectiveness of collaboration are in line with local studies (e.g., Haji Jalili & Shahrokhi, Citation2017; Tabatabaei et al., Citation2015) showing the positive effect of collaborative activities in learning different language skills and components. In congruence with the finding of the present study, Haji Jalili results indicated that collaborative writing was effective in the reduction of learners’ anxiety rates. The interview results in the present study also showed that the collaborative nature of the treatment had helped learners have less anxiety. Furthermore, Haji Jalili and Shahrokhi (Citation2017) in their study found that the participants had a positive attitude toward collaborative activities which is in line with the findings of the current study. Likewise, the results of the present study are consistent with those of Tabatabaei et al. (Citation2015) who investigated the effect of collaborative work on improving speaking ability and decreasing stress of Iranian EFL learners. The results revealed that the participants in experimental group outperformed the control group in terms of speaking ability. Moreover, the results indicated that the participants in experimental group had less stress after doing collaborative activities. The fi9ndings of their study also showed that the participants had positive attitudes toward CL.

The findings of this study showed that CTTs were effective in improving Iranian EFL learners’ performance in terms of figurative language. This result can be discussed on the theoretical foundations related to the notion of collaboration. For example, the very presence of teachers and their authentic interaction with learners are considered as the core principal of Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) and sociocultural theory proposed by Vygotsky (Citation1978). Based on this theory, these zones of development play an important role in learning. Put it other way, the learners in seeking to acquire new knowledge are helped by more knowledgeable people who act as scaffolding for less knowledgeable people. Besides, sociocultural theory contributes to a strong background to justify the efficacy of the treatment employed in this study. Sociocultural theory is basically related to social interactions within which conversation and dialogues take place.

For example, Lantolf and Aljaafreh (Citation1995) investigated the interactions between adult ESL learners and a teacher. Learners made progress in the ZPD through developmentally sensitive assistance in instruction sessions. The advent of a ZPD through pair-work led to performance at a higher level of competence for learners. This is because a learner does above his/her level of individual competence in the ZPD thanks to the helps given by the peer. Such kind of scaffolding leads to increasing independence and development. Similar process was found in this study as well. During this study, it was revealed that the teacher and learners participated in some kind of authentic interaction, with learners having the opportunity to make use of the language with authentic purposes in mind and taking advantage of a more knowledgeable individual.

9. Conclusion

Since the present study showed that Iranian EFL learners take benefit from CTTs in the learning of figurative language, therefore, language teachers are encouraged to employ this approach for teaching figurative language. Moreover, teacher trainers need to better prepare language teachers on how to appropriately employ the CTTs in teaching figurative language in their classrooms. Material developers are also encouraged to include appropriate directions and exercises which contain CTTs in the future materials. Since the participants of the present study were Persian speakers, and the interviewees held positive attitudes toward the use of L1 and collaborative tasks, EFL teachers in the Iranian context of ELT are encouraged to take CTTs more seriously when it comes to teaching different language skills and components in general and figurative language in particular.

Like any empirical study this study was not free from limitations which need to be compensated in future research. First of all, this study focused on intermediate language learners as the participants of the study. Thus, care should be taken in generalizing the findings of the study to language learners with other levels of language proficiency. Future studies may include students of other language proficiency levels so that the findings pertinent to learning figurative language would enjoy a more generalizability power. The native language of the participants in the present study was Persian. Future research may replicate the same study with participants whose mother tongue is a language other than Persian.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ramin Ahrari

Ramin Ahrari is an MA Student of Applied Linguistics at Islamic Azad university of Shiraz-Iran and EFL teacher for over three years. He has received his BA degree in Mathematics at Shiraz University but due to his interest in English language, teaching and psychology changed his major to Applied linguistics. His Research interests include EFL vocabulary, task-based language teaching, metaphorical competence and figurative speech.

The present study aimed at investigating the effect of the use of collaborative translation tasks for teaching figurative language and this research relates to wider projects relating the role of the use of L1 in learning L2.

References

- Abdullah, M. K. K. (2013). Goals of reciprocal teaching strategy instruction. The International Journal of Language Learning and Applied Linguistics World, 2(1), 18–27.

- Al Odwan, T. (2012). The effect of the directed reading thinking activity through cooperative learning on English secondary stage students’ reading comprehension in Jordan. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(16), 138–151.

- Atkinson, D. (1987). The mother tongue in the classroom: A neglected resource? ELT Journal, 41(4), 241–247. doi:10.1093/elt/41.4.241

- Auerbach, C. E., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Banos, M. O. (2009). Mother tongue in the L2 classroom: A positive or negative tool? Revista Lindaraja, 21(4), 321–329.

- Biria, R., & Jafari, S. (2013). The impact of collaborative writing on the writing fluency of Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(1), 164–175. doi:10.4304/jltr.4.1.164-175

- Boers, F., & Lindstromberg, S. (2006). Cognitive linguistic applications in second or foreign language instruction: Rationale, proposals, and evaluation. In G. Kristiansen, M. Achard, R. Dirven, F. J. Ruiz, & D. M. Ibáñez (Ed.), Cognitive linguistics: Current applications and future perspective (pp. 305–355). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Bouangeune, S. (2009). Using L1 in teaching vocabulary to low English proficiency level students: A case study at the University of Laos. English Language Teaching Journal, 2(3), 186–193.

- Chen, Y. (2010). Teaching idioms in an EFL context: The past, the present, and a promising teaching method. Proceeding of the 27th International Conference on English Teaching and Learning in R.O.C. (ROC-TEFL 2010), 182–193. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Crane Publishing Co

- Cook, G. (2010). Translation in language teaching: An argument for reassessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 402–423. doi:10.3138/cmlr.57.3.402

- Haji Jalili, M., & Shahrokhi, M. (2017). The effect of collaborative writing on Iranian EFL learners’ l2 writing anxiety and attitudes. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 4(2), 203–215.

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. (1992). Positive interdependence: Key to effective cooperation. In R. Hertz-Lazarowitz& & N. Miller (Eds.), Interaction in cooperative groups: The theoretical anatomy of group learning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kagan, S. (1994). Cooperative learning. San Juan Capistrano, CA: Kagan Cooperative learning.

- Kövecses, Z. (2001). A cognitive linguistic view of learning idioms in an FLT context. In M. Pütz, S. Niemeier, & R. Dirven (Ed.), Applied cognitive linguistics II: Language pedagogy (pp. 87–115). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- Kövecses, Z., & Szabó, P. (1996). Idioms: A view from cognitive semantics. Applied Linguistics, 17(3), 326–355. doi:10.1093/applin/17.3.326

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Lantolf, J. P., & Aljaafreh, A. (1995). Second language learning in the zone of proximal development: A revolutionary experience. International Journal of Educational Research, 23(7), 619–632. doi:10.1016/0883-0355(96)80441-1

- Levine, G. (2003). Target language use, first language use, and anxiety: Report of a questionnaire study. Modern Language Journal, 87(3), 343–364. doi:10.1111/1540-4781.00194

- McCarthy, P., Mccarten, T., & Sandiford, R. (2008). Touch stone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stanley, K. (2002). Using the first language in second language instruction: If, when, why, and how much? TESL-EJ, 5(4), 1–22.

- Tabatabaei, O., Afzali, M., & Mehrabi, M. (2015). The effect of collaborative work on improving speaking ability and decreasing stress of Iranian EFL learners. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(4), 274–280.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of the higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: The Harvard University Press.

Appendix A

Figurative language test

Read the following 30 sentences and

1. Determine whether the sentence contains a figurative expression,

2. Indicate if thinking figuratively is prerequisite to understanding the sentence

3. Underline the figurative expression in each test item.

1. The man was like a prowling lion.

2. The man was as hungry as a bear.

3. She jumped into a circus of activity once school started.

4. His voice was thunder, rattling the windows and the doors of the classroom.

5. The promise between us was a delicate flower.

6. He’s a rolling stone, and it’s bred in the bone.

7. He pleaded for her forgiveness but Janet’s heart was cold iron.

8. She was just a trophy to Ricardo, another object to possess.

9. The path of resentment is easier to travel than the road to forgiveness.

10. Katie’s plan to get into college was a house of cards on a crooked table.

11. The wheels of justice turn slowly.

12. Words are the weapons with which we wound.

13. She let such beautiful pearls of wisdom slip from her mouth without even knowing.

14. Scars are the roadmap to the soul.

15. The quarterback was throwing nothing but rockets and bombs in the field.

16. We are all shadows on the wall of time.

17. My heart swelled with a sea of tears.

18. When the teacher leaves her little realm, she breaks her wand of power apart.

19. The Moo Cow’s tail is a piece of rope all raveled out where it grows.

20. My dreams are flowers to which you are a bee.

21. The clouds sailed across the sky.

22. Each flame of the fire is a precious stone belonging to all who gaze upon it.

23. And therefore I went forth with hope and fear into the wintry forest of our life.

24. My words are chains of lead.

25. The computer in the classroom was an old dinosaur.

26. Laughter is the music of the soul.

27. David is a worm for what he did to Shelia.

28. The teacher planted the seeds of wisdom.

29. Phyllis, ah, Phyllis, my life is a gray day.

30. Each blade of grass was a tiny bayonet pointed firmly at our bare feet.

Appendix B

Semi-structured interview questions

1. Do you think teaching figurative language via collaborative translation tasks helped you understand this type of language better?

2. Did you find the way of teaching and learning figurative language via collaborative translation tasks interesting?

3. Would you like to receive collaborative translation tasks for other language components (e.g., grammar, vocabulary) in your future courses?

4. How did collaborative translation tasks help you learn figurative language under instruction?

5. What did you like most concerning the use of collaborative translation tasks for teaching figurative language?