Abstract

Learner autonomy has been a focus of research for last more than three decades. Teachers are considered a potential instrument in bringing change but their role, however, received little space which is observed recently, particularly in developing learner autonomy in language classrooms. This paper examines the beliefs of Pakistani English teachers about the feasibility of autonomy in learners at BS level and investigates the potential socio-cultural constraints restricting the development of learner autonomy. A sample of 16 English language teachers was selected from four public universities and data were gathered through semi-structured interviews. Data were later analysed thematically. Pakistani learners and teachers believed that learner autonomy is a new concept. Culture has been found playing a major role in limiting the role of learner autonomy. The present study indicates that perceived barriers should be removed for successful promotion of autonomy in learners.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Over the last 30 years, researchers have been interested in understanding learners’ control of their learning. It is intended that a student should not be dependent fully on others so that one can become a useful and active member of the society. Present study uncovered the barriers that may prevent learners and teachers to enable their students to make decisions about their learning. Awareness of barriers would help teachers and students to look for the possible solutions and find the ways to remove these barriers. Hence, a society with self-sufficient life-long learners would better be in a position to combat challenges and prosper fast.

1. Introduction

Learner Autonomy (LA) has been a focus of interest in foreign language learning and teaching (Benson, Citation2011; Little, Citation1991; Palfreyman & Smith, Citation2003) for more than 30 years. Though extensive literature is available on nature and prospects of LA, yet the factors constraining these prospects received a limited space in scholastic work on LA. Such lack of focus is a significant gap particularly in the context of Pakistan where LA is a new concept despite recent efforts of introducing active learning in the classrooms. The present study is a part of PhD research that intended to bridge this gap by exploring teachers’ views on perceived potential constraints in promoting LA in Pakistan.

2. Literature review

An extensive literature on LA defines LA in the words of Holec’s (Citation1981, p. 3) who defined LA as the “ability to take charge of one’s own learning” where this ability means

‘to have and to hold, the responsibility for all the decisions concerning all aspects of this learning, i.e. determining the objectives; defining the contents and progressions; selecting methods and techniques to be used; monitoring the procedure of acquisition properly speaking (rhythm, time, place, etc.); evaluating what has been acquired’.

According to Benson (Citation2006), LA has been defined with a variety of terminology as replacing “ability” with “capacity” (as in Little, Citation1991), and “take responsibility for” with “take charge of.” This variation sometimes occurred in focus, centring on one of the perspectives more than other which were termed as technical, psychological and political by Benson (Citation2011). Dam (Citation1995) included the notion of learner’s “willingness” irrespective of his/her capacity. Then the individualistic tone of independence (Palfreyman & Smith, Citation2003) was mediated by interdependence (Boud, Citation1988). Esch (Citation1998, p. 37) tried to define LA regarding what it is not by trying to eliminate the mistaken beliefs linked to the term such as the idea that the role of a teacher got redundant, or LA is a teaching pedagogy or observable behaviour (Author, Sohail, Sarkar, & Hafeez, Citation2017). Learner autonomy, as Holec (Citation1981) argued, must be understood as learner’s attribute and not a learning situation. This led to defining an autonomous learner with characteristics such as self-awareness of his/her capabilities, curiosity, motivation, flexibility, independence, interdependence, creativity, confidence and persistence as Candy (Citation1991) listed. It should also be noted, Nunan (Citation1997, p. 192) argued that LA is a matter of degree and not “all-or-nothing concept” and that degree may fluctuate due to some external or internal factors which may either enhance or block the promotion of LA.

3. Constraints in learner autonomy

A plethora of research on restrictions on learner’s role has focused adult learning (Bowl, Citation2001; Cross, Citation1981; Saar, That, & Roosalu, Citation2014; Valentine & Darkenwald, Citation1990). A major part of existing research laid emphasis on psychological constraints (Blair, McPake, & Munn, Citation1995), some researchers like Gooderham (Citation1993), Babchuk and Courtney (Citation1995) focused on social barriers while a part of research investigated institutional barricades (Jung & Cervero, Citation2002; Saar et al., Citation2014; Schaffer, Citation2010). Studies on learner autonomy investigated barriers as an aspect of the main studies investigating the nature and prospects of LA (Borg & Al-Busaidi, Citation2012; Nguyen, Citation2014).

Cross (Citation1981) identified three main categories of constraints making learner participation low: Situational, Institutional and Dispositional. For her, situational constraints were related to learner’s situation in life like lack of time or money required; dispositional barriers included features of personality which affect learning as lack of motivation or confidence, while institutional constraints included the practices that may hamper learners from participation. Among these three, external barriers of institutional practices were conceived easier to remove by educational system (Saar et al., Citation2014). Constraints in promoting LA were categorised by Benson (Citation2011) as policy constraints, institutional constraints, language learning conceptual constraints and language teaching approaches (p. 116) and by Borg and Al-Busaidi (Citation2012, p. 19) as three “sets of concerns” comprising of teacher-related, learner-related or institution related.

Irrespective of classification, multifarious constraints were highlighted by researchers in last one decade (Afshan, Askari, & Manickam, Citation2015; Borg & Al-Busaidi, Citation2012; Huang, Citation2006; Nakata, Citation2011; Nasri, Eslami Rasekh, Vahid Dastjerdy, & Amirian, Citation2015; Nguyen, Citation2014; Reinders & Lazaro, Citation2011). Most frequently cited constraints included learners’ lack of previous experience of autonomous learning, learners’ little contact with English outside the classroom, learners’ focus on passing tests, lack of incentives among learners, learner dependence on the teacher, learners’ proficiency level, lack of learner ability to exploit resources, teacher–learner interaction, teachers’ little trust on learner abilities, lack of teacher autonomy, traditional teaching practices, lack of relevant resources for teachers and learners, fixed curriculum, examination system, university entrance exams, lack of time, and educational policies.

Most of these studies overlooked indigenous cultural factor that influences the learning process in many ways. The cultural background of students can impede learning process (Palfreyman & Smith, Citation2003), or can facilitate them (Nasri et al., Citation2015) in supporting their autonomy. Asian learners experience reactive autonomy (Farahani, Citation2014) that “regulates the activity while the direction has been set” (Littlewood, Citation1996, p. 75) while researchers like Chan (Citation2001) considered LA and Asian culture as on poles apart as Asian teacher enjoys authority and respect and is supposed to be responsible for all learning by teachers and learners both while teachers are also reluctant to empower learners (Pham & Renshaw, Citation2013). A hierarchal inequality between teachers and learners posed an actual and common problem, Fischer and Sugimoto (Citation2006) argued quoting the example of Chinese learners who are trained to respect their teacher and become good listener and follower. This inbuilt cultural feature limits the chances of successful collaborative learning.

The review of existing literature manifests two gaps. First, most of the research was quantitative confirmatory depending on a survey only, and it is contended that a qualitative study that digs out and uncovers different aspects would be more beneficial and exploratory study might uncover the barriers faced by learners and teachers that a list of pre-determined themes cannot. Second, existing research has been conducted in some parts of Asia whereas subcontinent area remained unexplored. Moreover, Pakistani culture differs from other cultures as it is quite diverse with shades of Arab, Indian subcontinent and European colonial period and a shared history with Indian culture (Author, Sarkar, & Sohail, Citation2016; Author et al., Citation2017). It is established that religion influences the values of regional culture which, in turn, impacts educational practices. In Pakistani culture, learners are supposed to be obedient, and do not speak in front of elders unless they are spoken to; learners have a great reliance on teacher which encourages rote learning among students (Author & Sohail, Citation2018). As the interaction between male and females is not appreciated, there are separate schools for male and female students. In higher education institutions where coeducation is in practice, female learners are encouraged to be reserved in front of their male teachers, and distance is considered modesty (Amroun, Citation2008). According to Hofstede’s cultural model, “students from strong uncertainty avoidance countries expect their teachers to be experts who have all the answers” and “intellectual disagreement in academic matters is felt as personal disloyalty” (Citation2005, p. 179). Hierarchy discourages critical skills to be developed in learners. Being the first-ever study carried out in the specific context of Pakistan, an Asia Pacific country, the present work intends to address both gaps.

4. Research question

What socio-cultural barriers do Pakistani teachers face in promoting learner autonomy in English language classrooms?

4.1. Method

Following an interpretive paradigm, researchers employed a qualitative approach with a focus on exploring social relationships and processes. Researchers were interested in the meaning participants attached to the concept of LA.

4.2. Participants

The target population for the present research consisted of regular teachers teaching the English language at BS level in all 20 public universities of Punjab, whereas visiting faculty or teachers on the contract were excluded. A sample of 16 teachers was selected through purposive sampling from four universities of province Punjab. It was maintained that the sample should include two universities from the oldest and two from the youngest institutions of province Punjab as both old and young universities vary in quality regarding leadership, establishment, infrastructure and experienced faculty. The old universities were founded as early as 1800s, while the youngest institutes were set up in 2000s. Single-gender and single discipline universities were excluded to keep the sample homogeneous.

Among selected participants, four teachers were selected from each university on the basis of their teaching experience and their subject expertise and background in English linguistics or literature as shown in Table . As the most of faculty in young universities had an experience range of 1–10 years, so a cut-off value for teaching experience was decided as five years. Teachers with five years or less were considered less-experienced while teachers with more than five year experience were considered as experienced teachers. Again, as English language teachers vary regarding their academic background also, so selection of teachers was made from both sub-disciplines of English department. These two criterions were made to keep the sample homogenous and to see whether due to these categories they vary in their perceptions about the viability of LA in Pakistan.

Table 1. Sample profile

5. Method of data collection

A qualitative approach was followed to answer the research question. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to explore the teachers’ perceptions in depth. As researchers did not find any interview instrument, so question for the interview was generated after reviewing the literature on LA. Interview question asked participants about socio-cultural barriers they face in the promotion of LA in their language classrooms (see in Appendix A).

Consent form signed by the participants informed them about the purpose, procedure to be followed, their level of involvement and the voluntary nature of their participation. Participants’ names were replaced by initials to ensure confidentiality, e.g. MI, SJ, RM, SS, SB, FM, AP, MA, KN, RJ, JJ, IG, SH, and SM. All interviews were recorded individually face-to-face each with time duration of 40–60 min. Recorded data were transcribed later.

6. Method of data analysis

An inductive approach to constant-comparison analysis was followed, to meet the research objectives, and data were analysed thematically (Creswell, Citation2003). The thematic analysis involved multiple readings of data which helped in breaking up the text into codes (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, Citation2006) which were identified as initial and focused codes as Bailey (Citation2007) categorised. These codes were reduced into themes (see Appendix C). Though a review of literature informed about major themes but coding was kept open intentionally with no pre-decided set to guarantee that subsequent classification mirror the reality as was perceived by participant and not researcher’s previous ideas. Identified themes were then interpreted with a rich description of respondents’ opinion and connected to literature. Lincoln and Guba’s (Citation1985) suggestions were followed to ensure trustworthiness: respondents were requested to verify the truthfulness of transcriptions to enhance credibility and objectivity, thick verbatim descriptions of contributors’ reports were incorporated.

7. Results and discussion

Participants’ responses showed similar beliefs among all teachers from literature and linguistics background. Their response to the research question led to nine socio-cultural barriers.

7.1. Lack of awareness about La among teachers

LA is a quite new concept in Pakistan’s education system where teaching and learning is teachers’ responsibility as one participant AP perceived. He did not observe autonomous learning in Pakistani culture as he reported. Recent studies on student-centred learning also supported that the concept is introduced recently in Pakistan (Qutoshi & Poudel, Citation2014). Therefore, AP considered its presence only at a theoretical level. Practically in Pakistani culture, learner enquiry is not appreciated at large, thus, turning LA not only into a foreign concept but also a challenge to instructor’s power. AP called it a borrowed term taken from foreign education system to a system where teachers feel threatened by learners’ questions.

Learners and teachers were reported as unaware of the nature and significance of LA according to few respondents. This unfamiliarity leads to unawareness about expected roles of learners and teachers as one participant SJ said. Another respondent SB related lack of awareness in teachers to previous educational experiences as she added, “this is how they grew up, and there hasn’t been any professional development workshops on learner autonomy so that they can practice it in their classrooms/teaching.” Developing awareness about learner’s autonomy among learners and teachers was considered the first step by Nunan (Citation1997) and Smith (Citation2003) in the promotion of LA. It can be argued here that teachers who themselves had not experienced LA would not be able to develop this in their learners as was analysed by Little (Citation2000) and empirically confirmed by Reinders and Lazaro (Citation2011), Borg and Al-Busaidi (Citation2012) and Humphrey and Wyatt (Citation2014).

7.2. Expected roles of teachers and learners

Institutionalised expected roles of learners and teachers are also influenced by culture as MA said, “in Jumma prayer, there is Imam (who leads the prayer) who would deliver a lecture, and that is totally Imam-centred lecture… that kind of teaching practice perhaps has transferred to our formal teaching practices as well.” Similarly, the teacher is considered an expert and source of knowledge and this general behaviour lead to the teacher-centred classroom. However, one needs to be cautious of the fact that a teacher-centred class may work in other disciplines but not in a language learning class.

7.3. Authoritative teachers

A majority of participants found Pakistani teachers authoritative in class that reflects Asian culture (Pham & Renshaw, Citation2013). One participant MI expressed their behaviour in words, “They are not trained to listen to. They are trained to enforce their own things on others” that seems interpretation of Merriam-Webster’s definition of an authoritative person which if translated for a Pakistani teacher would state as someone who wants learners’ submission and power to decide about their learning process. In Pakistani culture and religion, the role of a teacher is akin to that of a parent. Thus, the teacher takes an authoritarian status in the classroom as a father does at home. Learners get attuned to the way they are brought up, and consequently, they act to an expected set of behaviour, first from parents and later from teachers. As they had been overprotected and were supposed to follow what was decided by their elders, they turn to become careless, and dependent with higher expectations from others as research showed (Bernstein, Citation2013; Paulussen-Hoogeboom, Stams, Hermanns, Peetsma, & Van Den Wittenboer, Citation2008). It is interesting to note the link between the authoritative attitude of teachers and Pakistani culture from IG’s comparison of Pakistani teachers qualified from Pakistan and abroad that how teachers get more sympathetic once they get a foreign learning exposure.

An obvious consequence of authoritative attitude is the learner–teacher distance that affects the goal of good teaching as one participant SJ pointed out. In such scenario, the teacher is unable to understand learner’s needs and abilities while learner turns to be submissive. Male learners were reported to vary in attitude, and it is evident how female learners become more submissive than male learners. An authoritarian learning culture stems from a power–distance relationship which is a common feature of South and East Asian countries as Hofstede (Citation1986) perceived and as Fischer and Sugimoto (Citation2006) found it affecting classroom interaction.

7.4. Lack of teacher-tolerance towards learner-opinion

Autonomy in learners requires them to become individual who can hold an independent opinion, but Pakistani learners’ right of opinion, similar to other Asian contexts (Nguyen, Citation2014) is not encouraged rather one participant SB described it a nightmare of the teachers particularly from public sector institutions. Many participants like SJ, SB, MI, KN and MN found teachers intolerant to new ideas, particularly when forwarded by some learner as well as towards difference of opinion as MI stated, “ If a student comes down with a kind of novel idea or assignment, teachers in our community, they crush it. How could they (learners) do this”? Hence, a novel concept might be wasted only for the reason that the world teacher might not know about, might not exist. Intolerance towards learners’ opinion can be related to their authoritarian mind-set. The most obvious damage from lack of tolerance results in short-sightedness thus impeding learning process and also in lack of flexibility to accommodate others in the long run.

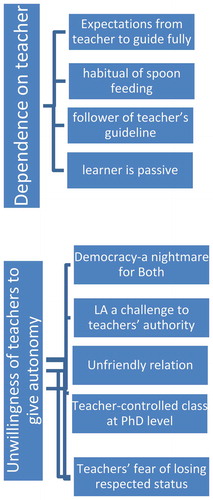

7.5. Lack of teacher-willingness for LA

Teachers are not willing to transfer learning control to learners, SB reported. Teachers enjoy an honourable place in the society as was mentioned above and for this reason, SB expounded, “We cannot dare even to give learners autonomy as we fear that concept of a Teacher will be gone … Mater sb had respect, and they enjoy that tag-that very thing will be gone.” In a hierarchal society where a respectful power distance lies, young children and learners are taught to respect and they are not expected to argue with their elders so they turn to be listeners and followers only. Students, hence, can never become co-learners (Fischer & Sugimoto, Citation2006). Nguyen (Citation2014) found teachers unwilling to share power that they enjoy in Asian culture. Qutoshi and Poudel (Citation2014) called it a fear of losing authority.

7.6. Learners’ dependence on teacher

Some participants found learners dependent upon being taught. SJ described Pakistani learners as “aspirant of teachers’ spoon-feeding only” who in RM’s words “expect everything to be told to them, everything to be explained to them, everything to be made clear to them.” Learners have great expectations from their teachers to direct them entirely. They were reported to respond when they were demanded to do so by their teachers. This finding brings Pakistani learners in the line of reactive autonomous learners as were found in the studies of Reinders and Lazaro (Citation2011) and Farahani (Citation2014) where latter reported learner’s view of their dependence, “they (teachers) are paid for it.” MI and others linked this attitude to cultural training where learners had been familiar to a teacher-dominated class and without previous experience of autonomy; they are not ready for such a change.

7.7. Shyness in interacting with peers of opposite sex

Another cultural barrier highlighted by some participants including RM, FM, SH, and JJ was shyness in interacting with peers of opposite gender, and particularly female learners were reported feeling shy in interacting with male peers. SH said, “this is the case with most of the girls of the class because in their families they are not allowed to even have an interaction with their male cousins, or there are girls who are not allowed to argue with their brothers and father in a louder voice.” Shyness restricts language learning when the teacher tries to engage learners in language use and a shy learner avoids opportunity of target language use with a fear that opposite-sex may laugh at. Shy learners were reported to prefer group work in a recent study (Mohammadian, Citation2013) but the present study showed that culturally shy learners avoid group work as one participant RM shared his problem of creating mix-gender groups and found less interaction among them as compared to the group with single-sex learners. Research showed that shyness is negatively correlated with extroversion (Afshan et al., Citation2015). In the Asian context, shyness is regarded as a quality (Sinha, Citation2011) and shyness should be considered more a religious trait than a psychological issue when dealing with it. One participant FM found faith-oriented constraint harder to remove than others.

7.8. Teacher bias for learner

Few participants pointed out some socially influenced deficiencies in teacher which may restrict their supportive role for all learners. One of them, SM, found that teachers showed a favourable response to bright learners as compared to learners with average cognitive abilities. This finding is in line with results of Buzdar, Ali, Akhtar, Maqbool, and Nadeem (Citation2013) who directed focus on a semester system that made teachers favour few learners. Present study found other types of biases which are linked with social class, gender and religious or political inclination of learners. Past research also highlighted a sizable discrimination effect against learners of different race, ethnicity and gender. As Tenenbaum and Ruck (Citation2007) showed that teachers’ expectations vary with learners’ ethnic background. A report from US data has showed that teachers’ perceptions about their learners’ performance are biased towards their sex and race. Teachers were reported to assess female learners’ performance higher than male learners’. Research suggests that assigning learners to a same gender or same race teacher significantly improves the achievements of male and female learners (Dee, Citation2005). A study of Swedish public highschools recommends blind grading to reduce the educational inequality Hinnerich et al., 2015). Teachers’ unequal treatment with learners on the base of any factor mentioned above may affect learner motivation badly as previous research also showed (Cooper, Citation2001).

7.9. Influence of British colonial past

Previous British occupation resulted in negative attitudes towards language learning and these attitudes still prevail as present finding showed. Beliefs, as Dornyei (Citation2001) propagated, can be created or changed with the help of family, peer or instructor. SB perceived that a prejudiced view filtered from elders to learners, and that wipes out chances of integrative motivation in learners. A tension between linguistic heterogenization and cultural homogenization exists. Few people still consider it a remnant of the colonization rather than taking it as an opportunity. It is established that to speak means to accept the culture the language comes from. Research also showed that learners’ image about a place is correlated with their performance and a negative image of a language if not addressed by the instructor (Despagne, Citation2010) affects the performance of its learners (Normazidah, Koo, and Hazita Citation2012).

Above results and discussion highlights few things. Present study, in line with past research (Appendix B), shows that traditional practices and teachers’ authoritative attitude damages learner–teacher’s relation, and learners’ confidence (Omaggio, Citation1986). When learners loses confidence on his abilities, they start looking towards their teacher to be guided fully. Hence, teachers’ behaviour turns learners passive and deprives them of any chance of becoming proactive in life. In a similar vein, shyness spoils the chances to initiate and interact with peers; hence the opportunities of learning from each other are lost. Research has shown that teacher is a source of motivation and demotivation of learners and that autonomy depends on teachers’ attitudes towards learner (Bernstein, Citation2013; De Naeghela, Keera, & Vanderlindea, Citation2014; Guthrie, Citation2008; Jang, Reeve, & Deci, Citation2010).

8. Conclusion

The purpose of present study was to explore teachers’ perceived socio-cultural constraints in developing learner autonomy in their educational context. The above analysis showed that Pakistani teachers identified various constraining factors that could hamper the development of learner autonomy in Pakistani contexts. Among perceived socio-cultural barriers, the most common and significant factors hindering the promotion of learner autonomy included lack of awareness about learner autonomy, the authoritative attitude of teachers, intolerance towards learner creativity and intelligence, learner dependence on the teacher, shyness in interaction with opposite sex and teacher bias.

Despite the recent focus on learner-centred approach in some institutes, teachers’ beliefs show that development of LA in public sector is an ideal hard to achieve. As teachers and learners are grown up in Pakistani culture, so they are socially and psychologically attuned to its hierarchal structure that they have no motivation to change the roles. It is also inferred from teachers’ opinion that Pakistani learners possess reactive autonomy and can become proactive only when along with institutional changes socio-cultural constraints are addressed.

By highlighting constraints, present findings guide parents, teachers, learners and educational authorities to map the line of action as socio-cultural constraints cannot be overcome by any single party involved. Following implications are made to pave the way for LA promotion: teachers should be trained to meet the challenges. Training can be a pre-requisite to teacher hiring or teachers can be trained during their service period. However, training programmes should be updated and focused on LA as the main goal should be enabling teachers to become autonomous in their professional lives and understand how to shift responsibilities to learners gradually. Also, teacher trainings must have a moral aspect to teach them to be neutral and unbiased towards learners. Moreover, these trainings should be frequent. Lastly, post-training checks are essential to see whether training is translated in the classrooms or not. This study focused on teachers’ beliefs as potential agents of change. The role of the learner, as a central stakeholder to the process, needs to be equally examined but it is beyond the scope of this paper. Future studies may want focus on the role the student, and further our understanding of this phenomenon.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Musarat Yasmin

Musarat Yasmin is an Assistant Professor of English at University of Gujrat, Pakistan. Her main research interest is Applied Linguistics. Her published work includes area of language, gender and media, English for specific purposes and learner autonomy. She is Associate editor of Hayatian Journal of Linguistics and Literature.

References

- Afshan, A., Askari, I., & Manickam, L. S. S. (2015). Shyness, self-construal, extraversion-introversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism: A cross-cultural comparison among college students. SAGE Open, 5(2), 1–8. doi:10.1177/2158244015587559

- Amroun, F. P. (2008). Learner autonomy and intercultural competence. Dissertation submitted to University of Westminster, UK.

- Babchuk, W. A., & Courtney, S. (1995). Towards a sociology of participation in adult education programs. International Journal of Lifelong Learning, 14(5), 391–404. doi:10.1080/0260137950140505

- Bailey, C. A. (2007). A guide to qualitative field research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press.

- Benson, P. (2006). Autonomy in language teaching and learning. Language Teaching, 40(1), 21–40. doi:10.1017/S0261444806003958

- Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching autonomy (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bernstein, D. A. (2013). Parenting and teaching: What’s the connection in our classrooms? Psychology Teacher Network, 23(2), 1–6. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/ptn/2013/09/index.aspx

- Blair, A., McPake, J., & Munn, P. (1995). A new conceptualisation of adult participation in education. British Educational Research Journal, 21(5), 629–644. doi:10.1080/0141192950210506

- Borg, S., & Al-Busaidi, S. (2012). Teachers’ beliefs and practices regarding learner autonomy. ELT Journal, 66(3), 283–292. doi:10.1093/elt/ccro65

- Boud, D. (Ed.). (1988). Developing student autonomy in learning. New York, NY: Kogan Press.

- Bowl, M. (2001). Experiencing the barriers: Non-traditional students entering higher education. Research Papers in Education, 16(2), 144–160. doi:10.1080/02671520110037410

- Buzdar, M. A., Ali, A., Akhtar, J. H., Maqbool, S., & Nadeem, M. (2013). Assessment of students’ learning achievements under semester system in Pakistan. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research, 3(6), 79–86.

- Candy, P. C. (1991). Self-direction for lifelong learning. California: Jossey-Bass.

- Chan, V. (2001). Readiness for learner autonomy: What do our learners tell us? Teaching in Higher Education, 6(4), 505–518. doi:10.1080/1356251020078045

- Cooper, C. M. W. (2001). School choice reform and the standpoint of African American Mothers: The search for power and opportunity in the educational marketplace ( Doctoral dissertation). University of California, Los Angeles

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Cross, K. P. (1981). Adults as learners: Increasing participation and facilitating learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Dam, L. (1995). Learner autonomy: From theory to classroom practice (Vol. 3). Dublin: Authentik Language learning resources.

- De Naeghela, J., Keera, H. V., & Vanderlindea, R. (2014). Strategies for promoting autonomous reading motivation: A multiple case study research in primary education. Frontline Learning Research, 3, 83–101.

- Dee, T. S. (2005). A teacher like me: Does race, ethnicity, or gender matter? The American Economic Review, 95(2), 158–165. doi:10.1257/000282805774670446

- Despagne, C. (2010). The difficulties of learning english: Perceptions and attitudes in Mexico. Canadian and International Education, 39(2), 55–74.

- Dornyei, Z. (2001). New themes and approaches in second language motivation research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 43–61. doi:10.1017/S0267190501000034

- Esch, E. (1998). Promoting learner autonomy: Criteria for the selection of appropriate methods. In R. Pemberton, E. S. L. Li, W. W. F. Or, & H. D. Pierson (Eds.), Taking control: Autonomy in language learning (pp. 35–48). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Farahani, M. (2014). From spoon feeding to self-feeding: Are iranian EFL learners ready to take charge of their own learning? Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 11(1), 98–115.

- Fischer, G., & Sugimoto, M. (2006). Supporting self-directed learners and learning communities with sociotechnical environments. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 1, 31–64. doi:10.1142/S1793206806000020

- Gooderham, P. N. (1993). A conceptual framework of sociological perspectives on the pursuit by adult access to higher education. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 12(1), 27–39. doi:10.1080/0260137930120104

- Guthrie, J. T. (2008). Engaging adolescents in reading. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hesse-Biber, S., & Leavy, P. (2006). The practice of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Hinnerich, B. T., Hoglin, E., & Johannesson, M. (2015). Discrimination against students with foreign backgrounds: Evidence from grading in Swedish public high schools. Education Economics, 23(6), 660–676. doi:10.1080/09645292.2014.899562

- Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 11, 301–320. doi:10.1016/0147-1767(86)90015-5

- Hofstede, G., & Hofstede, G. J. (2005). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (2nd ed.). USA: McGraw-Hill.

- Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Huang, J. (2006). Fostering learner autonomy within constraints: Negotiation and mediation in an atmosphere of collegiality. Prospect: an Australian Journal of TESOL, 21(3), 38–57.

- Humphrey, G., & Wyatt, M. (2014). Helping Vietnamese university learners to become more autonomous. ELT Journal, 68(1), 52–63. doi:10.1093/elt/cct056

- Jang, H., Reeve, J., & Deci, E. L. (2010). Engaging students in learning activities: It is not autonomy support or structure but autonomy support and structure. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 588–600. doi:10.1037/A0019682

- Jung, J.-C., & Cervero, R. M. (2002). The social, economic and political contexts of adults’ participation in undergraduate programmes: A state-level analysis. International Journal of Lifelong Learning, 21(4), 305–320. doi:10.1080/02601370210140977

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues and problems. Dublin: Authentik.

- Little, D. (2000). We’re all in it together: Exploring the interdependence of teacher and learner autonomy. Retrieved December 16, 2005, from www.encounters.jp/mike/professional/publications/tchauto.html

- Littlewood, W. (1996). “Autonomy”: An anatomy and a framework. System, 24(4), 427–435. doi:10.1016/S0346-251X(96)00039-5

- Mohammadian, T. (2013, November). The effect of shyness on iranian EFL learners‟ language Learning motivation and willingness to communicate. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3(11), 2036–2045. doi:10.4304/tpls.3.11.2036-2045

- Nakata, Y. (2011). Teachers’ readiness for promoting learner autonomy: A study of Japanese EFL high school teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 900–910. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.03.001

- Nasri, N., Eslami Rasekh, A., Vahid Dastjerdy, H., & Amirian, Z. (2015, July). Promoting learner autonomy in an Iranian EFL high school context: Teachers’ practices and constraints in focus. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 4(3), 91–105. doi:10.5861/ijrsll.2015.925

- Nguyen, T. N. (2014). Learner autonomy in language learning: Teachers’ beliefs ( Doctoral dissertation). Queensland University of Technology, Australia.

- Normazidah, C. M., Koo, Y. L., & Hazita, A. (2012). Exploring English language learning and teaching in Malaysia. GEMA Online™ Journal of Language Studies, 12(1), 35–55.

- Nunan, D. (1997). Designing and adapting materials to encourage learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 192–203). London: Longman.

- Omaggio, A. C. (1986). Teaching language in context: Proficiency-oriented Instruction. Boston: Heinle and Heinle.

- Palfreyman, D., & Smith, R. C. (2003). Learner autonomy across cultures: Language education perspectives. Bangsingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Paulussen-Hoogeboom, M. C., Stams, G. J., Hermanns, J. M., Peetsma, T. T., & Van Den Wittenboer, G. L. (2008). Parenting style as a mediator between children’s negative emotionality and problematic behavior in early childhood. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 169, 209–226. doi:10.3200/GNTP.169.3.09-226

- Pham, T. T. H., & Renshaw, P. (2013). How to enable asian teachers to empower students to adopt student-centred learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(11), 65–85. doi:10.14221/ajte.2013v38n11.4

- Qutoshi, S. B., & Poudel, T. (2014, March). Student centered approach to teaching: What does it mean for the stakeholders of a community school in Karachi, Pakistan? Journal of Education and Research, 4(1), 24–38. doi:10.3126/jer.v4i1.9620

- Reinders, H., & Lazaro, N. (2011). Beliefs, identity and motivation in implementing autonomy: The teachers’ perspective. In G. Murray, X. Gao, & T. Lamb (Eds.), Identity, motivation, and autonomy in language learning (pp. 125-142). Bristol

- Saar, E., That, K., & Roosalu, T. (2014). Institutional barriers for adults’ participation in higher education in thirteen European countries. Higher Education, 68, 691–710. doi:10.1007/s10734-014-9739-8

- Schaffer, J. M. (2010). Accessibility, affordability, and flexibility: The relationship of selected state sociopolitical factors and the participation of adults in public two-year colleges ( Doctoral dissertation). University of Montana.

- Sinha, M. (2011). Shyness in Indian context ( Unpublished doctoral thesis). National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, India.

- Smith, R. C. (2003). Teacher education for teacher-learner autonomy. In Symposium for Language Teacher Educators: Papers from Three IALS Symposia (CD-ROM). Edinburgh: IALS, University of Edinburgh. Retrieved from http://www.warwick.ac.uk/elsdr/Teacher_autonomy.pdf

- Tenenbaum, H. R., & Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 253–273. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.2.253

- Valentine, T., & Darkenwald, G. G. (1990). Deterrents to participation in adult education: Profiles of potential learners. Adult Education Quarterly, 41(1), 29–42. doi:10.1177/0001848190041001003

- Yasmin, M., Sarkar, M., & Sohail, A. (2016). exploring english language needs of hotel industry in Pakistan: An evaluation of existing teaching material. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education. doi:10.1080/10963758.2016.1226846

- Yasmin, M., & Sohail, A. (2018). A creative alliance between learner autonomy and english language learning: Pakistani university teachers’ beliefs. Creativity Studies, 11(1), 1–9. doi:10.3846/23450479.2017.1406874

- Yasmin, M., Sohail, A., Sarkar, M., & Hafeez, R. (2017). Creative methods in transforming education using human resources. Creativity Studies, 10(2), 145–158. doi:10.3846/23450479.2017.1365778

Appendix A

Interview Question

(1) Please introduce yourself.

(a) What is your highest qualification?

(b) How long have you been teaching English as a foreign language?

(2) What are the socio-cultural barriers do you face in developing learner autonomy in your English language classrooms?