Abstract

This paper aims to report on the development of a rubric and formative assessment targeting pre-service teacher instructional planning in an English teacher education programme in Indonesia. Ten curriculum components as proposed by Van den Akker were incorporated to develop the rubric. Educational Design Research (EDR) as an approach was employed to guide this study. The findings suggest that the rubric is useful in the formative assessment of the pre-service teacher instructional planning. Teacher challenges in instructional planning were also found, particularly in the five aspects: writing good learning objectives, defining teacher roles, determining learning activities, assessing outcomes, and allocating times needed for learning activities. The rubric is also effective in assessing not only cognitive and psychomotor learning, but also affective/attitude learning. Finally, the rubric can also be used to assess the internal consistency of the instructional planning.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Teaching is not an event, but a process of planning a lesson, teaching the planned lesson, and evaluating the lesson. Quality teaching is therefore inseparable from good planning. To better prepare teacher candidates (pre-service teachers) for the teaching profession, they need to understand and be able to plan good lessons in order to better teach their students. In this paper, a rubric for assessing instructional planning documents by pre-service teachers was developed and then used for such purpose. This rubric was used to improve the quality of instructional planning and the logical connection among its components. By using the rubric, it is found in this study that the pre-service teacher challenges in instructional planning revolve around writing good learning objectives, determining how teachers facilitate student learning, providing powerful learning activities for students to learn, developing appropriate instruments to assess student achievement, and allocating sufficient time for student learning activities.

1. Introduction

In teacher education, instructional planning has become an important and required skill (Baylor, Citation2002; Kitsantas & Baylor, Citation2001; Yildirim, Citation2003); just as important as the practice of teaching itself (Carlgren, Citation1999). Effective teaching usually begins with effective lesson planning and it makes lessons more integrated, makes teachers more confident, and can be use as a future reference (Jensen, Citation2001). It also helps teachers evaluate their own knowledge concerning the content to be taught (Reed & Michaud, Citation2010). Considering these significances, instructional planning skill has been stated clearly in some curriculum standards for English pre-service teachers’ education. For example, a professional organisation in the US, the Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) Association, has included planning for standards-based ESL and content instruction as one of the K-12 professional teaching standards under the domain of instruction (Fenner & Kuhlman, Citation2012). In Indonesia, the association of teachers and lecturers of English Linguistics, Literature, and Education (ELITE) also includes instructional planning as one domain of professional teaching standards for pre-service English teacher education in Indonesian Islamic universities and colleges (ELITE, Citation2016). The inclusion of this standard has shown that planning is a required knowledge and skill for pre-service teachers of English both in the contexts of English as a first/second and English as a foreign language.

In spite of the research on instructional planning assessments developed in different contexts and for different purposes (e.g., Albashiry, Citation2015; Ruys, Keer, & Aelterman, Citation2012; Theoharis & Causton-Theoharis, Citation2011), there is a need for a specific rubric that incorporates certain subject matter, local curriculum policy, context and instructional planning need. This paperreports on the development of such a rubric and formative assessment targeting pre-service teacher instructional planning challenges. The rubric created was grounded in and developed from Van den Akker’s ten curricular spider web components as it was developed in the context of an English teacher preparation programme in Indonesia and used as a framework to formatively assess the pre-service teachers’ instructional planning challenges.

Table 1. Specifications of the elaborated curricular spider web components

Table 2. Results of pre-service teacher instructional planning assessment

2. Theoretical foundations

2.1. Instructional planning approach

The terms “instructional planning” or “instructional design” in this study are used interchangeably which refers to a process of “considering the students, thinking of the content, materials and activities that could go into a course or lesson, jotting these down, having a quiet ponder, cutting things out of magazine and anything else that you feel will help you to teach well and the students to learn a lot, i.e., to ensure our lessons and courses are good (Woodward, Citation2001, p. 1)”. At a programme level, this process is usually carried out through a systematic approach (Gustafson & Branch, Citation2002).

Instructional Design (ID) is systematic, and it is deemed an appropriate approach that can help pre-service teachers plan lessons or instruction. Smith and Ragan (Citation2005, p. 2) defined it as “a systematic process of translating principles of learning and instruction into plans for instructional materials and activities”. Carr-Chellman (Citation2016) gives a more elaborated definition, stating that it is “the process by which instruction is created for classroom use through a systematic process of setting goals, creating learning objectives, analysing student characteristics, writing tests, selecting materials, developing activities, selecting media, implementing and revising the lesson (p, 3)”. As summarised by Hilgart, Ritterband, Thorndike, and Kinzie (Citation2012), the term ID can be differentiated in three specific contexts: as a science, field of practice, and process. ID as a science deals with the research-based ways people learn most effectively. As a field of practice, it is professionals working together to produce instruction, and as a process, it is seen as a model of systematic ID and development. For the purpose of this study concerning pre-service teacher instructional planning, the ID model is contextualised as a process.

In this study, the Smith and Ragan (Citation2005) was used to help pre-service teachers develop instruction as it is systematic, iterative in nature, and can improve the internal consistency of the curriculum design (Kessels & Plomp, Citation1999). The Smith and Ragan (Citation2005) has three main stages: analysis, strategy and evaluation. In the analysis phase, the learner identifies and formulates instructional needs, problems, target users, and learning tasks. In the strategy phase, the learner designs and develops instruction based on the results of the analyses and instructional theories. Finally, in the evaluation phase, the learner formatively evaluates whether the instruction has met the design principles and guidelines to achieve the desired outcomes. The result of this formative evaluation helps designers make a decision to proceed or to rethink the instruction.

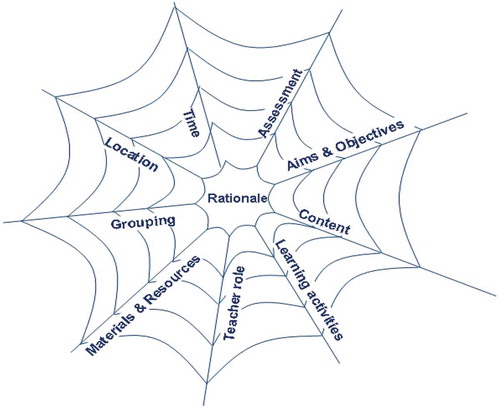

2.2. Curriculum level, components, and consistency

A simple definition of curriculum is a plan for learning (Taba, Citation1962), or the academic plans or blueprints for student learning (Wiles, Citation2009). In language teaching, Stern (Citation1992) refers to curriculum as a comprehensive plan of language teaching that organises objectives, contents, teacher development, teaching strategies, learning strategies, timing, and assessment in an integrated manner. Dependent on the products and stakeholders involved, curriculum can be categorised into five levels: supra (international), micro (national), meso (school), micro (classroom), and nano (pupil) level (Thijs & van den Akker, Citation2009; van den Akker, Citation2003, Citation2005). van den Akker (Citation2003) further provided a more elaborate list of the interrelated curriculum components of the so-called curricular spider web consisting of rationale, aim and objective, content, learning activities, teacher role, materials and resources, grouping, time, location, and assessment (see Figure ). In this curricular map, the rationale is the central point to which the other components are linked; therefore, the other nine components are susceptible to change when any one is altered. The connectedness of the components establishes consistency and coherence, the so-called internal consistency (Thijs & van den Akker, Citation2009; van den Akker, Citation2003, Citation2005). Although these ten components may differ in their scopes in different levels, for the purpose of this study, the internal consistency of the curriculum and its components here refers to the logical connection of the instructional planning components at the classroom level developed by pre-service teachers. This logical connection is also referred to as constructive alignment (cf. Biggs, Citation1996).

3. Context of study

This study was conducted in a Bachelor’s Degree programme in English teacher education at an Indonesian Islamic State University. The current curriculum of the programme has been used since 2015 to prepare the students to be teachers of English and instructional designers as their main learning profiles. For the profile of educational designers, students in their third year are offered 14 credit hours (one credit equals a 170-minute learning load) through several courses, such as Curriculum, Instruction, and Media, and, Curriculum and Course Design (CCD). CCD is a six-credit course during which students mostly spend their time designing and developing instruction during one semester (mostly a four-month learning process).

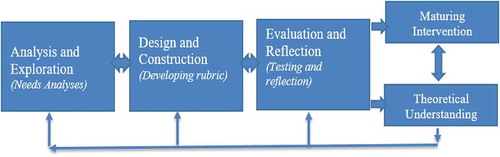

4. Method

This study employed Educational Design Research (EDR) as an overall research methodology (Figure ). This is “a genre of research in which the iterative development of solutions to practical and complex educational problems also provides the context for empirical investigation, which yields theoretical understanding that can inform the work of others” (McKenney & Reeves, Citation2012, p. 7). van den Akker, Mckenney, and Nieveen (Citation2006) characterise EDR as interventionist (oriented towards design of an intervention), iterative (a cyclic process), process oriented (understanding and improving interventions), utility oriented (practicality of the intervention in the real context) and theory oriented (theory-based design and contribution to theory development).

4.1. Analysis and exploration phase (needs analysis)

In order to develop the rubric, needs analyses were conducted to discover the curriculum needs, current problems of instructional planning, the context where the study was conducted, and the perceptions of pre-service teachers’ needs of instructional planning in the programme curriculum. These analyses were done to obtain practical information of the current condition of instructional planning in the programme. The results of the analyses showed that one of the newly implemented curriculum goals is to prepare pre-service teachers to have the ability to design instruction, but the existing rubric was so general that it was insufficient to assess the pre-service teachers’ skills. Moreover, an analysis on ten samples of the pre-service teachers’ instructional planning documents also showed that they lacked a constructive alignment among components. In other words, the connections between learning objective, activities and assessment were not clear. A learning objective targeting higher-order thinking skills was assessed minimally using a simple written test. During the analysis, the pre-service teachers also admitted that instructional planning was challenging particularly regarding writing the learning objective(s), developing learning activities and assessment. Relevant literature was also reviewed to get theoretical insight in relation to the practical problem of instructional planning. The results are summarised in Table :

4.2. Design and construction phase: development of instructional planning assessment rubric

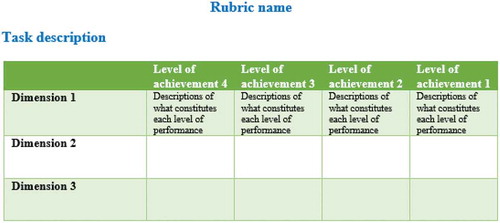

Both the results from the analyses and literature review were taken into account for developing the initial model of the rubric. Considering the complexity of implementing the curriculum and the results of the analyses, guidelines were then formulated for the development of the intended rubric. It was wise to adopt a systematic approach to develop a sound rubric that can help and support pre-service teachers in developing good instruction. In this respect, the rubric should contain information about task description (the assignment), levels of achievement, the dimensions of the assignment, and descriptions of what constitutes each level of performance, as shown in Figure . It should also be designed to reflect consistency in its performance criteria descriptors and to be useful for assessing learning by containing qualitative descriptions of the performance criteria that work well within the formative evaluation process of instructional planning.

Figure 1. Curricular spider web (Source:van der Akker, Citation2003; Citation2005)

Figure 2. Generic model of educational design research McKenney & Reeves, Citation2012)

4.3. Evaluation and reflection phase: testing and revision of the initial rubric

4.3.1. Expert appraisal

For the purpose of formative evaluation of the initial model of the rubric, three experts in English-language teaching (ELT) were invited for rubric appraisal. The negative aspects as identified by the experts were classified into three broad categories namely: inconsistency of performance level and its description, clarity of description, and the use of ambiguous or unclear terminology. Under the performance level 3 “approaching”, for instance, some descriptions did not fully show the criteria of the level; they should show that the student is moving towards the standard and may not be necessarily failing. Some descriptions also showed a trait of a failing student, not of one who is approaching the standard. This was the main issue raised in the expert appraisal. The issue of clarity was also addressed, especially pertaining to the component of “teacher role” that was insufficiently described, and thus needed more description. For example, in the “grouping” and “place” components, the word “learning characteristics” was vague and not comprehensible. Therefore, the word “outcomes” was suggested instead of “learning characteristics”.

4.3.2. Testing the rubric with independent assessors

After being revised based on the feedback from experts, the rubric was then tried out with two independent assessors who used the rubric to assess ten samples of instructional planning documents. This was done to find out the usability and the level of raters’ agreement on using the rubric or the interrater reliability of the rubric. The result of the interviews with the assessors shows that the revised rubric is easy to use since it is practical in assessing instructional planning documents. The assessment results from the ten samples were also calculated to obtain interrater reliability, and the result indicates a perfect agreement (.90) between the two assessors.

5. Results and discussion

5.1. Formative assessment on instructional planning

To investigate the pre-service teachers’ challenges with instructional planning, this study used 50 documents of the pre-service teacher instructional planning documents. These documents were collected from one of the assignments given during the CCD course with the student permission. To avoid subjectivity, the assessment involved two independent assessors who have background in ELT using the final rubric that was previously developed for the purpose of this study (see attachment 1). Overall the results indicate that 60.4% of the instructional planning met the passing standard (those who got “achieving” and “extending” performance criteria), while the rest 39.6% did not meet the minimum standard. In other words, these student assignments need further improvement.

The following sections will discuss the number of instructional planning documents (the student assignments) based on four performance criteria and the challenges pre-service teachers faced to show consistency in the ten components of instructional planning.

5.2. Challenges on instructional planning

Of the ten components or aspects, below are the five salient challenges the students faced in instructional planning, and these five challenges are sequenced from the most to the least challenging component (see Table ).

5.2.1. Objective (towards which goals were the students learning?)

Of the fifty documents assessed, the number of documents that did not achieve the performing level was 39 (78%). In other words, most pre-service teachers could not write good learning objectives that incorporated a clear audience, an action verb, a condition and a degree of mastery (ABCD). Pre-service teacher challenges in writing learning objectives revolved around the use of operational verbs, statements of condition and degree of mastery. Most learning objectives were poorly written and contained only the audience and some general verbs, but the statements of condition and degree of mastery were missing. The findings also show that the learning objectives written in the 50 documents are cognitive (60%), psychomotor (30%), and affective (10%) consecutively. This generally indicates that most instructional planning documents were designed to focus on the students’ cognitive aspect (knowledge). Concerning learning objectives, Piskurich (Citation2006) states that objectives are statements developed to explain what the students will achieve. In general, learning objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Action-oriented, Reasonable, and Timely (SMART) or SMARTER (plus Evaluate consistently and Recognise mastery) (Piskurich, Citation2006). According to Heinrich et al. (Citation1996), a good learning objective should have clear audience, behaviour, condition, and degree of mastery (ABCD Model for writing objective). Audience (A) answers the questions of who the learners are, Behaviour (B) is concerned with the teacher’s expectations of what the students will be able to do as indicated in the operational verbs used, Condition (C) is related to the circumstances or context under which the learning will take place, and finally Degree of mastery (D) is about how much, how well, or what level the learners have to achieve.

5.2.2. Teacher role (how did the teacher facilitate learning?)

The number of instructional planning documents that did not achieve the performing level in this aspect was 35 (70%). Based on the assessment, it was found that pre-service teachers’ challenges were related to (1) pedagogical content knowledge (PCK) or selecting appropriate pedagogical techniques for certain instructional content and (2) teacher pedagogical behaviour (Ruys et al., Citation2012). In many cases in this study, for example, pre-service teachers selected the instructional technique (pedagogy) without considering the content being taught. Different contents require appropriate techniques that fit the content characteristics. Another issue was instructional techniques in which pre-service teachers still adopted a teacher-centred approach. They tended to see teachers as more knowledgeable people who transfer knowledge to their students. In other words, teachers are active givers while students become passive recipients. Student’s role changes from passive recipients to engaged learners and active agents in the learning process, and teachers’ roles expand from knowledgeable teachers to student learning mediators or facilitators (Barman, Citation2013). In communicative language teaching (CLT), students’ needs and experiences are central to language teaching (Harmer, Citation2007; Richards & Rodgers, Citation2001), and therefore teachers may become thinkers, stimulators, challengers, risk takers, jugglers, timekeepers, lecturers, and even storytellers too (Kuhlman, Citation2010).

5.2.3. Learning activity (how were the students learning?)

The number of instructional planning documents that did not achieve the performing level was 32 (64%). Pre-service teachers’ challenges revolved around varying learning activities to meet the target students’ needs and characteristics in terms of learning formats (individual, pairs, or groups), learning stages, and types of learning activities (e.g., role-play, jigsaw, etc.). In some cases, individual learning dominated learning activities; pair work or group work were not encouraged as tools to make student learning better. Moreover, the stages of student learning progress stages were not clearly stated in the pre-service teachers’ instructional planning. Student learning activities consisted mostly of listening or paying attention to teachers, and there were limited opportunities for student language practice and production. In an authentic learning environment, students may progress from guided or semi-guided to free practice activities (Richards, Citation2001). Learning activities should enable students to use the target language for meaningful interaction and comprehensible communication (Atkins, Hailom, & Nuru, Citation1995). Common communicative activities in language learning include information gaps, role plays, jigsaws, debates, projects, etc. In relation to learning organisation, common models of organising or sequencing learning activities especially in ELT are PPP (presentation, practice, and production), Test, Teach, Test (TTT), Pre, While, Post activities for receptive skills, and Task-based Learning (TBL) (Woodward, Citation2001).

5.2.4. Assessment (how was the student learning assessed?)

Another pre-service teacher challenge in designing instructional planning was assessment, and the number of instructional planning documents that did not achieve the performing level was 29 (58%). Learning should be assessed to find out if learning objectives are achieved or not. This challenge is related to selecting and developing appropriate assessment instruments that are consistent with the learning goals/objectives. In some cases, for example, the learning objective was to enable students’ speaking, but learning achievement was assessed with a written test. Another example was a reading assessment which focused on comprehension/understanding. In the reading test, some items focused on the generic structure of narrative texts. These questions did not fully measure the students’ reading comprehension skills. Also, many assessment instruments were poor in terms of content and face validity. Some instruments were poorly spelt out or had many grammatical mistakes and inappropriacy of language use. In the literature, it is well established that learning should be assessed to find out if the learning objectives are achieved or not. In general, Earl (Citation2006) and West and Hopkins (Citation1997), as cited in Scheerens (Citation2002), classified assessment into three different categories: assessment of learning, assessment for learning, and assessment as learning. Assessment of learning measures the result of the learning effort or is used to confirm what students know and can do. This type of assessment is intended to measure the quality of learning, the so-called summative assessment. Assessment for learning is conducted to give teachers information to modify and differentiate teaching and learning activities (formative). Finally, assessment as learning is a process of developing and supporting metacognition for students. In assessing student learning, assessment instruments or methods include tests, interviews, observations, etc.

5.2.5. Timing (when and how long did the student learn?)

The number of instructional planning documents that did not achieve the performing level was 25 (50%). The challenges faced by pre-service teachers here concerned setting up or determining the sufficient time needed for every learning activity. Time really matters for student learning because education or instruction has a time limit for students to undergo. Instructional designers, for instance, need to analyse the required time for students to complete a course or a certain task or activity, especially how to structure time for students (Woodward, Citation2001). The time for a class session in a centralised curriculum such as in Indonesia is normally set by the government, but teachers are free to define the time required for each learning activity. Teachers sometimes think that the time allocated is not appropriate (Ostovar-Namaghi, Citation2017). In this case, O’Mahony (Citation2005) argues that a well-thought out instructional plan enables teachers to use such limited time more effectively. A particular learning task or activity might take more time than others, depending on its difficulty or complexity. Failing to define or allocate learning time could make it harder for students to achieve learning objectives.

6. Conclusion and reflection

This study reports on the development of a rubric and formative assessment targeting pre-service teacher instructional planning documents using a rubric which was developed based on Van den Akker’s ten curricular spider web components. This study reinforces that Van den Akker’s ten elaborated curriculum components are vital in instructional planning assessment, and that the rubric is useful in formative assessment.

The needs analyses and findings indicate that instructional planning is assumed to be a taken-for-granted skill by pre-service teachers of English. In other words, when someone becomes a teacher, he or she is assumed to have the ability of instructional planning. As a result, pre-service teachers sometimes underestimate instructional planning skill as one that supports their capacity in the teaching English profession. In this study, it is evident that some pre-service teachers found challenges in instructional planning, particularly in the five aspects of instructional planning explored in this study: learning objective, teacher role, learning activities, assessment, and times needed for learning activities. Another issue in this study is related to the use of the rubric for formatively assessing learning that focus not only on cognitive and psychomotor learning, but also on affective learning. In other words, the rubric used in this study also can be used to assess instructional planning documents that focus on affective or attitudes. The last issue is that the rubric can also assess the internal consistency of the instructional planning documents. The consistency can be measured from how all components of the instructional planning are logically related with one another. Consistency can be determined by looking at the similarity of the scores from all components; the more similar the scores from all components, the higher the consistency will be (see appendix 2 for guidance). Last but not least, this study may serve as a foundational study for other designers or researchers in the construction of instructional planning assessment rubrics in different contexts.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muhammad Fauzan Ansyari

Muhammad Fauzan Ansyari is an associate professor of curriculum development at the Faculty of Education and Teacher Training at the State Islamic University Sultan Syarif Kasim in Riau (UIN Suska Riau), Indonesia. His research interests include curriculum innovation, instructional and media design, Content-Based Instruction (CBI)/Content Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) and data use for curriculum improvement. He is now conducting a longitudinal research on English teacher professional development for data use to improve curriculum and instruction in higher education.

References

- Airasian, P. W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Pearson, Allyn & Bacon.

- Albashiry, N. M. (2015). Professionalization of curriculum design practices in technical vocational colleges: Curriculum leadership and collaboration. Doctoral Degree, University of Twente, Enschede.

- Atkins, J., Hailom, B., & Nuru, M. (1995). Skills development methodology (part 1). Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University Printing Press.

- Barman, B. (2013). Shifting education from teacher-centered to learner-centered paradigm Paper presented at the International Conference on Tertiary Education (ICTERC 2013), Daffodil International University, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

- Baylor, A. L. (2002). Expanding preservice teachers’ metacognitive awareness of instructional planning through pedagogical agents. Educational Technology Research and Development, 50(2), 5–22. doi:10.1007/BF02504991

- Biggs, J. (1996). Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. Higher Education, 32, 347–364. doi:10.1007/BF00138871

- Brown, J. D. (1995). Elements of language curriculum: A systematic approach to program development. Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

- Carlgren, I. (1999). Professionalism and teachers as designers. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(1), 43–56. doi:10.1080/002202799183287

- Carr-Chellman, A. A. (2016). Instructional design for teachers: Improving classroom practice (2 ed.). New York: Routledge.

- De Jong, T. (2010). Cognitive load theory, educational research, and instructional design: Some food for thought. Instructional Science, 38(2), 105–134. doi:10.1007/s11251-009-9110-0

- Dijkstra, S. (2004). The integration of curriculum design, instructional design, and media choice. In N. M. Seel & S. Dijkstra (Eds.), Curriculum, plans, and processes in instructional design: International perspectives (pp. 145–170). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Earl, L. (2006). Rethinking classroom assessment with purpose in mind. Winnipeg: Manitoba Education, Citizenship and Youth.

- ELITE. (2016). Professional teaching standards. Jakarta: Author.

- Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc.

- Fenner, D. S., & Kuhlman, N. (2012). Preparing effective teachers of English language learners: Practical applications for the TESOL P-12 professional teaching standards. Virginia: TESOL International Association.

- Graves, K. (2000). Designing language courses: A guide for teachers. Boston: Thomson Heinle.

- Gustafson, K. L., & Branch, R. M. (2002). Survey of instructional development models (4 ed.). Syracuse, NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Information & Technology.

- Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

- Heinrich, R., Molenda, M., Russell, J. D., & Smaldino, S. E. (1996). Instructional media and technologies for learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill.

- Hilgart, M. M., Ritterband, L. M., Thorndike, F. P., & Kinzie, M. B. (2012). Using instructional design process to improve design and development of internet interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(3), 1–18. doi:10.2196/jmir.1890

- Jensen, L. (2001). Planning lessons. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign laguage (pp. 403–413). Boston: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

- Kessels, J., & Plomp, T. (1999). A systematic and relational approach to obtaining curriculum consistency in corporate education. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 31(6), 679–709. doi:10.1080/002202799182945

- Kitsantas, A., & Baylor, A. (2001). The impact of the instructional planning self-reflective tool on preservice teacher performance, disposition, and self-efficacy beliefs regarding systematic instructional planning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(4), 97–106. doi:10.1007/BF02504949

- Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing technological pedagogical content knowledge. In A. C. o. I. a. Technology (Ed.), Handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Kuhlman, N. A. (2010). Developing foreign language teacher standards in Uruguay. Gist Education and Learning Research Journal, 4(1), 107–126.

- McKenney, S. E., & Reeves, T. C. (2012). Conducting educational design research. New York, NY: Routledge.

- O’Mahony, C. (2005). Planning for social studies learning throughout the day, week and year. Social Studies and the Young Learner, 18(1), 29–32.

- Ostovar-Namaghi, S. A. (2017). Language teachers’ evaluation of curriculum change: A qualitative study. The Qualitative Report, 22(2), 391–409.

- Piskurich, G. M. (2006). Rapid instructional design: Learning ID fast and right. San Fancisco: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Reed, M., & Michaud, C. (2010). Goal-driven lesson planning for teaching English to speakers of other languages. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Richards, J. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Richards, J., & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and methods in language teaching (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ruys, I., Keer, H., & Aelterman, A. (2012). Examining pre-service teacher competence in lesson planning pertaining to collaborative learning. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(3), 349–379. doi:10.1080/00220272.2012.675355

- Scheerens, J. (2002). School self-evaluation: Origins, definitions, approaches, methods and implementation. In D. Nevo (Ed.), School-based evaluation: An international perspective (pp. 35–69). Kidlington, Oxford: Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14. doi:10.3102/0013189X015002004

- Smith, P. L., & Ragan, T. J. (2005). Instructional design. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Stern, H. (1992). Issues and options in language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Taba, H. (1962). Curriculum development: Theory and practice. New York: Harcourt Brace and World.

- Theoharis, G., & Causton-Theoharis, J. (2011). Preparing pre-service teachers for inclusive classrooms: Revising lesson-planning expectations. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(7), 743–761. doi:10.1080/13603110903350321

- Thijs, A., & van den Akker, J. (2009). Curriculum in development. Enschede: The Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development (SLO).

- van den Akker, J. (2003). Curriculum perspectives: An introduction. In J. van den Akker, W. Kuiper, & U. Hameyer (Eds.), Curriculum landscapes and trends. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- van den Akker, J. (2005). Curriculum development re-invented. Paper presented at the The invitational conference on the occasion of 30 years SLO 1975-2005, Leiden, the Netherlands.

- van den Akker, J., Mckenney, S., & Nieveen, N. (2006). Design research from a curriculum perspective. In J. van den Akker, D. Gravemeijer, S. Mckenney, & N. Nieveen (Eds.), Educational design research (pp. 67–91). New York: Routledge.

- West, M., & Hopkins, D. (1997). Using evaluation data to improve the quality of schooling. Frankfurt: ECER-Conference.

- Wiles, J. (2009). Leading curriculum development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Woodward, T. (2001). Planning lessons and courses: Designing sequences of work for the language classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yildirim, A. (2003). Instructional planning in a centralized school system: Lessons of a study among primary school teachers in Turkey. International Review of Education, 49(5), 525–543. doi:10.1023/A:1026361208399

Appendix 1:

Instructional Planning Assessment Rubric (IPAR)

Purpose:

This rubric is designed to be used in a formative context to assess the quality and consistency of pre-service teacher instructional planning documents.

Instruction:

To assess quality, for each performance component circle or highlight the level that best describes the observed performance.

Appendix 2:

Consistency Scoring Guidance

Purpose:

This rubric is used to assess internal consistency of instructional planning document.

Instruction:

To assess consistency, for each performance component circle or highlight the level that best describes the characteristic of the observed performance. The more similar the scores from all components the higher the consistency will be. For example, if each component is scored with a level of 2, then the document shows higher consistency. On the other hand, if the scores vary, then it shows lower consistency.