Abstract

This study explored the effects of noticing and computerized dynamic assessment on the learning of Persian vocabulary through reading. In this quasi-experimental study, 75 intermediate learners of Persian as a Foreign Language (PFL) were assigned to three equal-sized groups. In the Noticing and Computerized Dynamic Assessment (CDA) groups, the learners were notified that there were highlighted unfamiliar words in the texts and they were required to infer their meanings by the help of their own knowledge and textual and contextual clues. In the CDA group, struggling learners received mediational hints through a software program which helped them to infer word meanings successfully. In the control group, the learners were not notified of unfamiliar words and they were not required to infer word meanings. It took four days to administer the four treatment texts. One day before the first treatment session, the pretest of unfamiliar words was given. One and thirty days after the last treatment session, vocabulary learning and retention posttests were administered. On learning and retention variables, the Noticing group’s mean was significantly higher than the control group’s; and the CDA group’s mean was significantly higher than the control and Noticing groups’ means. The results indicated that noticing of texts’ unfamiliar words and adoption of dynamic approach to assessment through the CDA software enhanced vocabulary learning from reading.

Public Interest Statement

Learning a foreign language is a wonderful yet at times an exhausting endeavor. One of the main obstacles in learning a language relates to the acquisition of multitudes of words which are encountered in foreign language communication. Since all words cannot be covered in the language classrooms, the learners need to equip themselves with strategies to tackle unfamiliar words which are met during communication in foreign language. One of these strategies involves inferring the meaning of unfamiliar words from context. In this study, we focused on inferring the meaning of unfamiliar words in reading texts. We hypothesized that drawing learners’ attention to unfamiliar words and assisting them in inferring their meanings could result in more vocabulary learning. Our results confirmed these hypotheses.

1. Introduction

One of the main problems of Persian as a Foreign Language (PFL) learners relates to the acquisition of Persian vocabulary (Vakilifard, personal communication). Because of time and resource limitations, usually a limited number of Persian words which are judged by instructors or syllabus designers to be among basic words are included in the syllabus and thus receive direct teaching in class. Second language (L2) learners must learn the rest of the words as a byproduct of language use activities (Nation, Citation2001). One of the language use activities which could lead to the acquisition of unfamiliar words involves reading of L2 texts in and out of class. It is expected that level-appropriate L2 texts could provide enough textual and contextual clues for the learner to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words and gradually learn them (Hulstijn, Citation2001).

As in first language (L1), vocabulary learning through reading is possible in L2 but “is not always an efficient or an easy strategy for L2 students to use” (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004, p. 226). Studies have reported significant vocabulary gains from L2 reading (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004; Day, Omura, & Hiramatsu, Citation1991; Dupuy & Krashen, Citation1993; Horst, Cobb, & Meara, Citation1998; Hulstijn, Citation1992; Min, Citation2008; Pitts, White, & Krashen, Citation1989; Waring & Takaki, Citation2003; Zahar, Cobb, & Spada, Citation2001), however, considering the time invested in reading, these gains have not been substantial (Waring & Takaki, Citation2003). Compared to advanced learners, low and intermediate L2 learners experience difficulties in inferring the meaning of unfamiliar words and consequently fail to learn them (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004; Morrison, Citation1996).

In the current study, a review of the literature was done to identify some of the main variables behind low vocabulary gains from reading. Two methodological problems were noticed in previous research. First, measures were not taken to ensure noticing of the unfamiliar words by the learners (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004). In his Noticing Hypothesis, Schmidt (Citation2001) argued that learners must notice the learning targets in the input, otherwise, they will not learn it. Hulstijn (Citation2001, p. 275) stated that “the more a learner pays attention to a word’s morphological, orthographic, prosodic, semantic and pragmatic features and to intraword and interword relations, the more likely is it that the new lexical information will be retained”. It is not important whether the attention is intentionally or incidentally directed to the word. Bengeleil and Paribakht (Citation2004) stated that, in reading for comprehension, the learners’ attention is on grasping the message of the text and since sometimes the message could be understood without the need for knowing all of the text’s words it is possible that the learners skip the unfamiliar words or do not recognize them as being unfamiliar. When a word is not recognized by the learner as unfamiliar, no processing of that word would take place.

Second, we noticed that static approaches to assessment (SA) were adopted in studies of word learning through reading. In SA, there is a one-way relationship between the teacher and the learner in which the learner responds to teacher’s questions. The teacher does not intervene in the assessment process since instruction and assessment are treated as separate entities. Furthermore, the focus is on the product of learning and thus, due attention is not paid to the process of learning (Stenberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002). When the focus of an assessment approach is on measuring the product of learning, it is presupposed that the learners have already had instruction in the ability which is being observed and have practiced it enough. In studies of word learning through reading, focus has been on the amount of word learning which would follow a certain amount of reading and the learners have not been observed during reading to see whether they are proficient in inferring word meanings from context or not. It is quite possible that some learners, especially the intermediate ones who had been reported to have problems with this skill (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004), were not experienced in inferring word meanings from context.

In this study, measures were taken to address the above problems and to improve word learning through reading. Noticing of unfamiliar words was ensured through highlighting of the target words and explicit instructions which required the learners to infer the meanings of those words. Computerized dynamic assessment (CDA) was also used. CDA is the computer-adapted version of dynamic assessment (DA). DA falls within the framework of socio-cultural theory of learning. According to this learning theory, cognitive development germinates in interpersonal interactions in which one side is the learner and the other side is a more capable person. The more capable person mediates between the learner and the learning subject and through contingent graduated hints helps the learner to secure the learning objective. These measures reveal the learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) which includes the learner’s developing as well as developed abilities and in the meantime, promote those developing abilities (Lantolf & Poehner, Citation2008; Poehner & Lantolf, Citation2003). ZPD refers to “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky, Citation1978, p. 86).

In DA, a two-way interactive relationship is developed between the teacher and the learner whereby both parties could initiate questions. Since instruction and assessment are viewed as two aspects of a single entity, the teacher could intervene in the assessment process and assist the learner to achieve the task objectives. In DA, the process of learning is prioritized over the product of learning (Stenberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002). Focus on the process of learning necessitates that the learners be observed during learning and, if need be, be assisted and instructed in the ability that is being developed. This justified focus on the process of learning and development inevitably leads to better actualization of learning products.

In this study, through a CDA software we intervened in the reading process and, whenever the learners indicated problems in inferring of word meanings, provided the learners with inference hints which enabled them to successfully infer word meanings. Through these hints, the learners were acquainted with the various types of clues and knowledge sources which facilitate inference making and gained experience in drawing on them.

Thus, the study aimed to explore the effects of noticing and CDA on vocabulary learning through reading in PFL learners. To this end, two research questions were raised. What effect does noticing of an L2 text’s unfamiliar words have on the learning and retention of those words? What effect does use of CDA during L2 reading have on the learning and retention of inferred words?

2. Review of literature

L2 reading and L2 vocabulary knowledge are intimately interrelated. Large vocabulary sizes could help learners to read L2 texts fluently and comprehend them and, in return, ample amounts of reading could lead to vocabulary learning (Nation, Citation2001). Studies have reported significant correlations between L2 learners’ vocabulary knowledge and their reading comprehension (Nation, Citation2006; Qian, Citation2002). Significant vocabulary gains have also been reported from L2 reading (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004; Day et al., Citation1991; Dupuy & Krashen, Citation1993; Horst et al., Citation1998; Hulstijn, Citation1992; Min, Citation2008; Pitts et al., Citation1989; Waring & Takaki, Citation2003; Zahar et al., Citation2001).

Though significant, vocabulary gains from L2 reading have not been substantial. Day et al. (Citation1991) asked 92 high school and 200 university learners of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) to read a 1032-words short story. There were 17 unfamiliar words in the text. Immediately after reading, a multiple-choice vocabulary test was administered. The results showed that high school and university learners acquired 5.8 and 17.6 percent of the unfamiliar words respectively.

In Zahar et al.’s study, 144 learners of English as a Second Language (ESL) read a short novel of 2383 words. Thirteen days before and two days after reading, pretest and posttest of 30 unfamiliar words were administered, respectively. Across five research groups, mean vocabulary gain from pretest to posttest amounted to 7.2 percent of the unfamiliar words.

This trend of low vocabulary gains from L2 reading was also reported in other studies which mostly employed immediate posttests (Dupuy & Krashen, Citation1993; Horst et al., Citation1998; Hulstijn, Citation1992; Pitts et al., Citation1989; Waring & Takaki, Citation2003). Waring and Takaki (Citation2003) argued that, considering the time that was invested in reading the texts, these amounts of vocabulary gains are not substantial.

Bengeleil and Paribakht (Citation2004) attributed low vocabulary gains from L2 reading to the lack of noticing of unfamiliar words by the learners. In Noticing Hypothesis, Schmidt (Citation2001) stated that the prerequisite of any learning is that the learners be aware of what they do not know yet. Following this hypothesis, Bengeleil and Paribakht (Citation2004) argued that in previous studies, the learners attended to the messages of the reading texts and because of that did not notice the texts’ unfamiliar words. As the learners did not notice the unfamiliar words, naturally they did not attempt to infer their meanings through textual and contextual clues or their own knowledge.

To explore the effect of noticing of the texts’ unfamiliar words on the acquisition of those words, Bengeleil and Paribakht (Citation2004) presented a 1000-words text to ten intermediate and seven advanced EFL learners. The text contained 26 unfamiliar words. First, the learners read the text for general comprehension. Then, they read another copy of the same text in which unfamiliar words had been underlined and tried to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words. These measures were taken to ensure noticing of the unfamiliar words by the learners. Posttest results showed a 20 percent improvement in the learners’ knowledge of unfamiliar words. In comparison to Day et al. (Citation1991) and Zahar et al. (Citation2001), Bengeleil and Paribakht (Citation2004) experiment led to more vocabulary acquisition. This motivated us to include the noticing variable in the Noticing and DA groups of this study.

It has been shown that directing learners’ attention toward the unfamiliar words through annotations, marginal glosses, production tasks, or use of bilingual dictionaries enhances word learning through reading (Chun & Plass, Citation1996; Hulstijn, Hollander, & Greidanus, Citation1996; Hulstijn & Laufer, Citation1998; Hulstijn & Trompetter, Citation1999; Knight, Citation1994; Watanabe, Citation1997). There is also empirical support that vocabulary enhancement activities positively affect word learning through reading (Min, Citation2008; Paribakht & Wesche, Citation1997; Wesche & Paribakht, Citation1998, Citation2000).

In reviewing the literature, we noticed another possible cause for low vocabulary gains from L2 reading. In previous studies (Day et al., Citation1991; Dupuy & Krashen, Citation1993; Horst et al., Citation1998; Hulstijn, Citation1992; Pitts et al., Citation1989; Waring & Takaki, Citation2003; Zahar et al., Citation2001), researchers generally required the learners to read texts containing unfamiliar words, however, did not train them how to deal with unfamiliar words. Yet, immediately or after some interval, learners were post-tested on texts’ unfamiliar words. This shows that the focus has been on measuring the amount of word learning through reading and due attention has not been devoted to whether the learners could draw on textual and contextual clues in the text and consequently infer the meanings of unfamiliar words or not. Also, it has not been explored whether the learners were familiar with various types of textual and contextual clues and knowledge sources involved in lexical inferencing or not. Thus, we suspect that low vocabulary learning through reading could partially be explained in terms of the fact that the learners might have not been familiar with various clues and knowledge sources involved in lexical inferencing and have not been trained in drawing on those clues and knowledge sources.

Since previous studies did not train learners in dealing with the texts’ unfamiliar words, it can be induced that they adopted static approaches to assessment. In SA, focus is on measuring the amount of learning which was the product of development in the past and the process of development is neglected to a large extent (Stenberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002). To enhance vocabulary learning through reading, we need to experiment with assessment approaches which focus on the development process. As an educational approach to assessment, DA is a good candidate to start with.

In DA, both the product and the process of development are duly attended to through the conception of two zones of actual and proximal development. Zone of actual development (ZAD) could be observed in the learning tasks which the learner can handle independently. ZPD reveals itself in learning tasks which are beyond learner’s independent control, but the learner could perform them in collaboration with more capable persons (Lantolf & Poehner, Citation2008; Poehner & Lantolf, Citation2003). Exploring ZPD of a learner could reveal the learner’s developed and developing capabilities. To turn the developing abilities to established ones which are under independent control of the learner, the instructors could mediate between the learner and the learning task. In the mediation process, they might provide contingent graduated hints to the learners to help them solve the learning problem and successfully implement the skill that is being learned. When a learner successfully implements the skill that is the object of learning, the learning process is properly addressed. The proper addressing of the learning process inevitably leads to the gradual realization of the learning products. This motivated us to explore vocabulary learning through reading within dynamic assessment approach in the CDA group of this study.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

Since previous studies reported that intermediate L2 learners experience problems in inferring unfamiliar words’ meanings (Bengeleil & Paribakht, Citation2004; Morrison, Citation1996), we adopted purposive sampling for participant selection. Seventy-five PFL learners who had been placed in intermediate-level courses based on their respective schools’ placement tests agreed to participate in this quasi-experimental study. The learners were randomly assigned to three equal-sized groups. In the first, second, and third groups, respectively five, six, and two learners did not complete all the study tasks. Thus, their data were removed from statistical analyses. The participants were 18 to 28 years old and in terms of education ranged from high school diploma to master’s degree. The participants were learning Persian in Persian language schools across Germany, UK, Australia, and US and were recruited to the study through email correspondence. The study was conducted in Iran. Pretest, posttests, and treatments were delivered to the participants through email and the Internet.

For participant selection, the following procedure was taken. Fifteen Persian language instructors and tutors who placed teaching ads in teaching websites were contacted to introduce intermediate PFL learners for the study. Eleven instructors agreed to cooperate. After securing the consent of their respective clients, each instructor provided us with the email addresses of 2–6 PFL learners. The 37 PFL learners were invited through email to participate in the study and to introduce other intermediate PFL learners. In the end, 75 participants agreed to participate in the study. 53 were males and 22 were females. British, Australian, and American participants spoke English as L1. The German participants’ L1 was German. However, communication between them and the researchers was conducted in English. The participants consented to the administration of treatments and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any stage. They were assured that their personal identities and identifying information would remain confidential and would not be shared with others.

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. The CDA software

Twenty short stories which had less than 1000 running words were presented to a panel of three instructors who taught intermediate Persian language courses to foreign students at an Iranian university. The instructors subjectively judged the texts in terms of interest for the intended participants of the study. When two instructors agreed on the appropriateness of a text, it was submitted to judgment of difficulty level. Twelve texts emerged as interesting. Employing their expert knowledge, two of the instructors ordered the texts in terms of difficulty. Through Spearman rank order correlation, an interrater agreement of 0.87 was obtained. Then, the two instructors resolved their differences and collaboratively assigned the texts to four difficulty levels of easy, appropriate, slightly complex, and very complex. Four texts emerged as appropriate for our participants. The texts were 325, 364, 502, and 324 words in length and were sourced from http://yekibood.ir/stories, http://dehnavi1341.ir, http://www.peykneka.ir, and http://hdmmsr.blogfa.com, respectively. With regard to vocabulary and grammar, the texts were written in contemporary Persian. For each text, three essay-type comprehension questions were written.

The texts were given to 20 intermediate PFL learners other than the study participants. They were asked to read the texts and underline the words which were unfamiliar to them. The words which were judged as unfamiliar by more than 75 percent of the participants were selected for further analysis. Drawing on textual and contextual clues and knowledge sources involved in lexical inferencing, for each of the unfamiliar words at least one inference clue was identified (Appendix A in Supplementary material). For some words, inference clues could not be found and we had to make some minor modifications to the text to devise appropriate clues. The words for which we could not find or create inference clues were not selected as target words. In the end, 20 unfamiliar words for which the texts afforded inference clues were selected as target words. For each target word, one paraphrase and four distractors were written.

To prepare mediational hints for the target words, three taxonomies of textual and contextual clues and knowledge sources involved in lexical inferencing were consulted (De Bot, Paribakht, & Wesche, Citation1997; Haastrup, Citation1991; Nassaji, Citation2003). From the agreement of these taxonomies, five types of clues and knowledge sources for lexical inferencing were identified which included 1) co-text and discourse knowledge, 2) world and background knowledge, 3) the structure of the unfamiliar word and its relationships with other words, 4) syntactic knowledge, and 5) knowledge of languages other than L2. Drawing on these types of clues and knowledge sources, for each unfamiliar word of study texts, at least one inference clue was identified. Based on the inference clue, for each target word four hints were prepared and arranged from the most implicit to the most explicit. The texts, target words and their respective alternatives and hints, and comprehension questions were used to devise a software program as the treatment of CDA group.

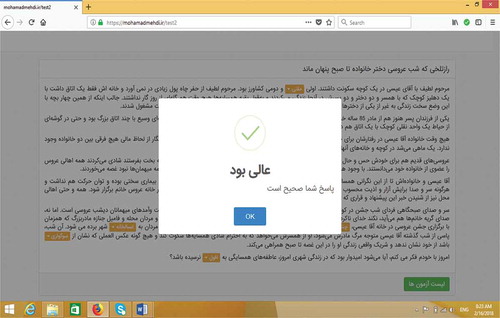

In each treatment session, the software first presented the instructions to the participants. Then, the participants read the text for comprehension and, while reading, tried to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words and from the drop-down menu, to select the option which best paraphrased each target word. When a learner selected the correct option, the software verified the correctness of the response and the learner continued reading (Figure ).

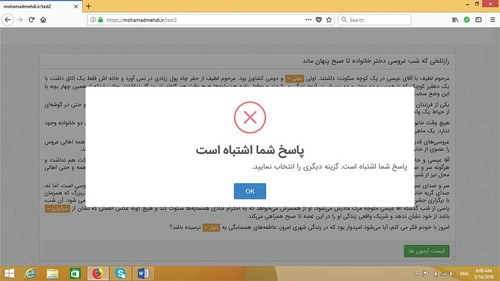

However, if the learner selected the incorrect option, the software presented the implicit hint to the learner. This hint informed the participant that the response was not correct and the learner had to choose another option (Figure ).

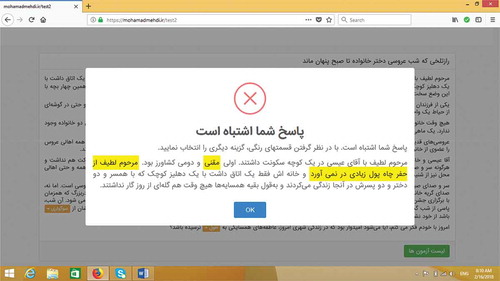

When at this stage the learner got the item right, the software verified the response and the learner continued reading. However, in case of failure, the software presented the less implicit hint to the learner. In this hint, the target word and a portion of the text which provided clues to the word’s meaning were highlighted and the learner was asked to consider them and reattempt the item (Figure ).

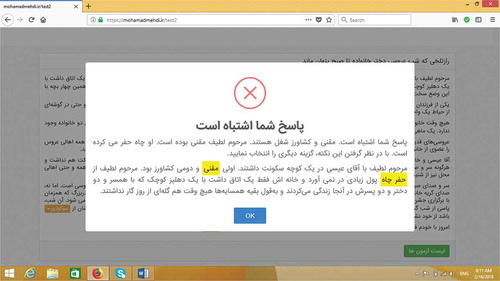

If at this point the learner selected the correct option, the software verified the response and encouraged the learner to continue reading. In case of an incorrect response, the software provided the partially explicit hint which explicated the relationship between the target word and the highlighted part of the text and asked the learner to attempt another option (Figure ).

If at this stage the learner got the item right, the software verified the response and the learner continued reading. Otherwise, the software presented the fully explicit hint which indeed was the correct option and the learner read on (Figure ).

Through the provision of these hints, the learners were expected to be peripherally acquainted with various clues and knowledge sources which enabled the inferring of unfamiliar words’ meanings. Additionally, they were to be indirectly trained in drawing on those clues and knowledge sources which would help them infer unfamiliar words’ meanings and learn them. After finishing the reading, the software presented the comprehension questions to the participants.

For readers who do not know Persian, a paragraph containing one of the target words is translated here to illustrate how the mediations progressed from the most implicit to the most explicit.

He proposed two camels to obtain the horse, but the man did not agree. He was not even willing to swap his horse with all the nomadic man’s camels.

The nomadic man thought to himself: Now that he is not willing to exchange his horse with all my assets, I have to set up a trick.

When the reader could not select the correct option which was closest in meaning to the underlined word, the first mediation would read “Your answer is not correct. Select another option.” When the reader selected the incorrect option, the second mediation would read “Your answer is not correct. Consider the highlighted parts and select another option.”

He proposed two camels to obtain the horse, but the man did not agree. He was not even willing to swap his horse with all the nomadic man’s camels.

The nomadic man thought to himself: Now that he is not willing to exchange his horse with all my assets, I have to set up a trick.

When the learner chose the incorrect option, the third mediation would read “Your answer is incorrect. Consider the highlighted phrases. ‘Exchange’ and ‘swap’ seem to have similar meanings. Try another option.”

He proposed two camels to obtain the horse, but the man did not agree. He was not even willing to swap his horse with all the nomadic man’s camels.

The nomadic man thought to himself: Now that he is not willing to exchange his horse with all my assets, I have to set up a trick.

When the learner got the item wrong again, the fourth mediation would read “Your answer is incorrect. The second option is the correct answer.”

3.2.2 The noticing group’s treatment

The texts, target words and their respective alternatives, and comprehension questions which were used to devise the CDA group’s treatment appeared in the Noticing group’s treatment as well. However, there were some differences. The treatment was not in software format. Each treatment session included a word file which consisted of four pages (Appendix B in Supplementary material). On the first page, the instructions were given. On the second page, the text was presented to the readers. In the text, the target words were highlighted for the participants and the learners were instructed to infer the meanings of target words. On the third page, the alternatives for each target word appeared. For each target word, the learner had to choose the option which best paraphrased it. On the fourth page, comprehension questions were given.

3.2.3 The control group’s treatment

The texts and comprehension questions which were used to devise the CDA group’s treatment were utilized to develop the control group’s treatment. Each treatment session included a word file which consisted of three pages. On the first page, the instructions were given. On the second page, the text was presented to the readers. The target words were not highlighted for the participants and the learners were not instructed to infer the meaning of unfamiliar words. On the third page, comprehension questions were given.

3.2.4 Pretest of target words

e of the target words prior to the administration of treatments. Although there were 20 target words in this study, the pretest included 100 items (Appendix C in Supplementary material). This measure was taken to mask the target words and decrease the learners’ chances of remembering them. In this test, the learners had to signal their familiarity with the target words. When a learner identified a word as familiar, for verification the learner had to write its meaning in front of it. For each “yes” response for which correct word meaning was provided, a point was awarded. For each “no” response, zero points were awarded. As stark differences between the learners in terms of the number of unfamiliar words could threaten sample homogeneity and influence the interpretation of pretest to posttest word gains, for each participant the number of unfamiliar words were tallied and compared to others’. This analysis showed that at least 17 of the 20 target words (85 percent of the target words) were unfamiliar for all the participants.

3.2.5 Learning and retention posttests

Learning and retention posttests measured the learners’ knowledge of the target words one and thirty days after the administration of treatments, respectively (Appendix D in Supplementary material). In the posttests, each target word appeared in a non-defining sentential context. For each target word, there were five paraphrases one of which expressed the word’s meaning. In the two posttests, the order of test items and their respective alternatives were different. In the learning posttest, for each correct or incorrect response one or zero points were awarded to the participant, respectively. To arrive at sheer learning scores, each participant’s pretest points were subtracted from that participant’s learning points. In the case of retention posttest, the same scoring scheme was followed to arrive at sheer retention scores.

3.3. Procedure

The four treatment texts were administered to all groups within four days, one text a day. One day before reading the first text, pretest of target words was held. One day after reading the fourth text, a posttest was administered to all groups which measured learning of the target words. Thirty days after reading the fourth text, a second posttest was administered to all groups which measured retention of the target words.

The treatment administration procedure was as follows. The control group read the texts containing unfamiliar words and answered some comprehension questions. The Noticing group read the same texts and answered the same comprehension questions, however, in their texts, unfamiliar words had been underlined. The learners of the group were explicitly required to infer the meanings of unfamiliar words by drawing on their own knowledge and textual and contextual clues and to select the option which best paraphrased the target word. The CDA group’s treatment was much similar to the Noticing group’s. The only difference was that, in the CDA group, through a software program, mediational hints were provided to the learners who could not infer the word meanings independently.

4. Results and discussion

Table presents the control, Noticing, and CDA groups’ means and standard deviations on learning and retention tests. On the learning variable, the means of the control, Noticing, and CDA groups were 1.76, 4.68, and 7.26 respectively. That is, the Noticing group’s mean was higher than that of the control group and the CDA group’s mean was higher than those of the control and Noticing groups. On the retention variable, the control, Noticing, and CDA groups’ means were 0.95, 3.21, and 5.69 respectively. In other words, the Noticing group’s mean exceeded that of the control group and the CDA group’s mean exceeded those of the control and Noticing groups.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

One-way MANOVA analysis (Table ) showed that adopting one of the three levels of the independent variable significantly affected the performances of groups’ participants on the dependent variables: F (2, 60) = 15.43, p < 0.05; Wilk’s Λ = 0.43.

Table 2. Results of MANOVA analysis

Tests of between-subjects effects (Table ) indicated that, on the learning scores, the three groups’ means were significantly different: F (2, 60) = 38.84, p < 0.05; Partial Eta Squared = 0.56. This showed that group differences in terms of the administered treatment led to significant group differences in the learning of target words. On the retention scores, the groups’ means were also significantly different: F (2, 60) = 27.41, p < 0.05; Partial Eta Squared = 0.47. This indicated that group differences in terms of the administered treatment led to significant group differences in the retention of target words.

Table 3. Results of tests of between-subjects effects

Table displays the results of Bonferroni post hoc tests. In learning variable, the mean difference between the control and Noticing groups was 2.92 words which was significant. The mean difference between the control and Noticing groups on the retention variable was 2.25 words which was also significant. Since on both learning and retention variables the Noticing group’s mean was higher than that of the control group (Table ), it can be stated that in the Noticing group learning and retention of target words was higher than that in the control group. Since the control and Noticing groups differed in terms of noticing of unfamiliar words and the group in which noticing of unfamiliar words was ensured performed better on learning and retention posttests, it could be stated that noticing of the text’s unfamiliar words could improve the learning and retention of those words.

Table 4. Results of Bonferroni post hoc tests

The Noticing group’s means on learning and retention tests were 4.68 and 3.2 words (23.4 and 16 percent of the target words) respectively (Table ). This amount of word learning through reading was more substantial than those reported in other studies. In many studies in which noticing of target words was not ensured by design (Day et al., Citation1991; Dupuy & Krashen, Citation1993; Horst et al., Citation1998; Hulstijn, Citation1992; Pitts et al., Citation1989; Waring & Takaki, Citation2003), a few percent of the target words were recalled on immediate posttests. However, in the Noticing group of the current study in which by design the learners were made to notice the target words, 23.4 percent of the target words were remembered on the

posttest which was given one day after the treatment. This showed that noticing of a text’s unfamiliar words could positively affect the learning of those words. The main difference between this study’s Noticing group and the above-cited studies was in the point that in this study’s Noticing group, unfamiliar words of the texts were underlined and the learners were explicitly asked to infer their meanings.

The current study’s findings were in line with Bengeleil and Paribakht (Citation2004) results. They presented a 1000-words text to 10 intermediate and 7 advanced learners of English. The participants read the texts twice, first for general comprehension and then for inferring the meanings of underlined words. The results indicated a 20 percent improvement in knowledge of target words.

Godfroid, Boers, and Housen (Citation2013) explored the effect of noticing the texts’ unfamiliar words on the acquisition of those words. Through an eye-tracking device, they measured L2 learners’ amount of attention to the texts’ unfamiliar words. The length of eye fixation on an unfamiliar word was taken as a measure of attention to that word. An unannounced posttest was used to measure the learning of unfamiliar words. The results showed that in comparison to familiar words, unfamiliar words received longer eye fixations and that there was a positive correlation between the length of eye fixation on unfamiliar words and the learning of those words.

The results of Bonferroni post hoc tests (Table ) showed that on learning and retention variables, the mean differences between the Noticing and CDA groups were 2.92 and 2.48 words respectively which were significant. On both the learning and retention variables, the mean of the CDA group was higher than that of the Noticing group (Table ). Since two groups differed in terms of assessment framework and the CDA group which adopted DA outperformed the other on learning and retention tests, it could be stated that adopting the DA enhanced the learning and retention of unfamiliar words through reading.

The CDA group’s means on learning and retention tests were 7.26 and 5.69 words (36.30 and 28.45 percent of the target words) respectively (Table ). The amount of word learning in the CDA group of this study which adopted DA was more substantial than studies like Pigada and Schmitt (Citation2006) and Brown et al. (Citation2008) which adopted SA. Despite the fact that Pigada and Schmitt's (Citation2006) participants read four long texts which in total included 30,000 running words and encountered some of the target words five to twenty times throughout the texts, they reported that one month after the treatment, learners’ knowledge of the target words improved 15.4 percent. Brown et al. (Citation2008) measured their participants’ vocabulary gain from reading immediately, one week, and three months after the treatment. In the long term, only 3.57 percent of the target words were retained. The main difference between the CDA group of this study and the above two studies was in the assessment approach. Thus, from the comparison of the current study with the previous studies which adopted SA it could be stated that employing DA could substantially improve learning and retention of words through reading. This substantial difference in learning and retention could be explained in terms of differences between DA and SA.

It was mentioned in the review of literature that in SA the main focus is on the amount of learning which resulted from past development and the process of development itself receives less attention (Stenberg & Grigorenko, Citation2002). However, in DA the process of development receives due attention (Lantolf & Poehner, Citation2008; Poehner & Lantolf, Citation2003). To learn vocabulary through reading, the learners must be familiar with various types of clues and knowledge sources which are involved in lexical inferencing and they must be trained in drawing on these resources when unfamiliar words are encountered in the course of reading. In this study, through a software program the learners who could not independently infer word meanings were assisted to draw on clues and knowledge sources which are involved in inferencing and to infer word meanings successfully. Through this procedure, the focus was taken off the product of lexical inferencing and redirected toward the process of lexical inferencing. Focus on the process of lexical inferencing peripherally acquainted the learners with various clues and knowledge sources involved in inferencing and in the meantime trained them in drawing on those resources and in dealing with texts’ unfamiliar words. The successful implementation of lexical inferencing skill inevitably led to improvements in the amount of word learning as the product of lexical inferencing. This is in stark contrast with studies which adopted SA. In such studies, usually the learners read some texts and after an interval took vocabulary posttests. In such circumstances, it cannot be established whether the learners were familiar with lexical inferencing clues and knowledge sources or not and if yes, whether they indeed could draw on those resources or not.

5. Conclusions and implications

In this study, there were two research questions which dealt with the effects of noticing and CDA on vocabulary learning through reading. The results showed that the Noticing group’s mean scores on learning and retention posttests were significantly higher than those of the control group; and that the CDA group’s mean scores on the posttests were significantly higher than those of the control and the Noticing groups. Thus, both research questions were answered affirmatively. It was concluded that the noticing of texts’ unfamiliar words and the adoption of CDA had a positive effect on vocabulary learning through reading.

There were some limitations to this study that should be considered before discussing the implications which could be drawn from the above conclusion. First, the sample was restricted to intermediate PFL learners and did not include advanced or low proficiency learners. Second, the learners’ perspectives on the tasks and the experiment were not investigated through post-treatment questionnaires. Third, the learners’ thought processes during inferencing were not explored through think-aloud or stimulated recall protocols.

Until further studies explore the above limitations and shed more light on vocabulary learning through reading, the following tentative implications could be drawn from the current study. It is suggested that Persian language instructors who wish to encourage word learning through reading might consider to mark the unfamiliar words of the reading texts, to explicitly require the learners to infer their meanings, and to interactively provide contingent graduated hints to the struggling learners to ensure successful inference of word meanings. Through these steps, noticing of the learning targets might be promoted; and also the assessment would focus on both the product and the process of word learning through reading. These measures may enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of teachers’ instructional activities and possibly help solve part of the L2 learners’ vocabulary learning problems.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (603.6 KB)Supplementary data

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed here http://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1507176

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saman Ebadi

Dr. Saman Ebadi holds a PhD degree in Applied Linguistics and is an Associate Professor at Razi University. His main area of research involves socio-cultural theory and dynamic assessment (DA). In collaboration with his students and colleagues, he has applied DA to diverse aspects of second language acquisition. Traditional DA requires one-to-one teacher-learner interactions and thus, is costly to conduct. One of the developments in the field has been to computerize DA practices and to administer them to multiple learners at once. In line with this development, Dr. Ebadi has also developed studies to explore language learning through computerized dynamic assessment (CDA). In this study, Dr. Ebadi and his colleagues, Dr. Amirreza Vakilifard and Dr. Khosro Bahramlou, developed a CDA experiment to explore vocabulary learning through reading.

References

- Bengeleil, N. F., & Paribakht, T. S. (2004). L2 reading proficiency and lexical inferencing by university EFL learners. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 61(2), 225–250. doi:10.3138/cmlr.61.2.225

- Brown, R., Waring, R., & Donkaewbua, S. (2008). Incidental vocabulary acquisition from reading, reading-while-listening, and listening to stories. English Language Teaching Journal, 20(2), 136–163.

- Chun, D. M., & Plass, J. L. (1996). Effects of multimedia annotations on vocabulary acquisition. The Modern Language Journal, 80, 183–198.

- Day, R., Omura, C., & Hiramatsu, M. (1991). Incidental EFL vocabulary learning and reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 7(2), 541–551.

- De Bot, K., Paribakht, T. S., & Wesche, M. (1997). Towards a lexical processing model for the study of second language vocabulary acquisition: Evidence from HSL reading. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 309–329.

- Dupuy, B., & Krashen, S. (1993). Incidental vocabulary acquisition in French as a foreign language. Applied Language Learning, 4, 55–64.

- Godfroid, A., Boers, F., & Housen, A. (2013). An eye for words: Gauging the role of attention in incidental L2 vocabulary acquisition by means of eye tracking. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(3), 483–517.

- Haastrup, K. (1991). Lexical inferencing procedures, or talking about words: Receptive procedures in foreign language learning with special reference to English. Tubingen, Germany: Gunter Narr.

- Horst, M., Cobb, T., & Meara, P. (1998). Beyond a Clockwork Orange: Acquiring second language vocabulary through reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 11(2), 207–223.

- Hulstijn, J. (1992). Retention of inferred and given word meanings: Experiments in incidental vocabulary learning. In P. Arnaud & H. Bejoint (Eds.), Vocabulary and applied linguistics (pp. 113–125). London: Macmillan.

- Hulstijn, J. H. (2001). Intentional and incidental second-language vocabulary learning: A re-appraisal of elaboration, rehearsal and automaticity. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 258–286). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hulstijn, J. H., Hollander, M., & Greidanus, T. (1996). Incidental vocabulary learning by advanced foreign language students: The influence of marginal glosses, dictionary use, and reoccurrence of unknown words. Modern Language Journal, 80, 327–339.

- Hulstijn, J. H., & Laufer, B. (1998) What leads to better incidental vocabulary learning: Comprehensible input or comprehensible output? In Third Pacific Second Language Research Forum. Tokyo, Japan, 26-29 March 1998.

- Hulstijn, J. H., & Trompetter, P. (1999). Incidental learning of second-language vocabulary in computer-assisted reading and writing tasks. In D. Albrechtsen, B. Henrikse, M. Im, & E. Poulsen (Eds.), Perspectives on foreign and second language pedagogy (pp. 191–200). Odense, Denmark: Odense University Press.

- Knight, S. (1994). Dictionary: The tool of last resort in foreign language reading? A new perspective. Modern Language Journal, 78, 285–299.

- Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2008). Dynamic Assessment. In E. Shohamy & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education, 2nd edition (Vol. 7, pp. 273–284). New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

- Min, H.-T. (2008). EFL vocabulary acquisition and retention: Reading plus vocabulary enhancement activities and narrow reading. Language Learning, 58(1), 73–115.

- Morrison, L. (1996). Talking about words: A study of French as a Second Language Learners’ lexical inferencing procedures. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 53, 41–75.

- Nassaji, H. (2003). L2 vocabulary learning from context: Strategies, knowledge sources, and their relationship with success in L2 lexical inferencing. TESOL Quarterly, 37(4), 645–670.

- Nation, I. S. P. (2001). How many high frequency words are there in English? In M. Gill, A. W. Johnson, L. M. Koski, R. D. Sell, & B. Wårvik (Eds.), Language, learning and literature: Studies presented to Håkan ringbom english department publications (pp. 167–181)). Åbo: Åbo Akademi University.

- Nation, I. S. P. (2006). How large a vocabulary is needed for reading and listening? The Canadian Modern Language Review, 63, 59–82.

- Paribakht, T. S., & Wesche, M. (1997). Vocabulary enhancement activities and reading for meaning in second language vocabulary acquisition. In J. Coady & T. Huckin (Eds.), Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy (pp. 174–199). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pigada, M., & Schmitt, N. (2006). Vocabulary acquisition from extensive reading: A case study. Reading in a Foreign Language, 18(1), 1–28.

- Pitts, M., White, H., & Krashen, S. (1989). Acquiring second language vocabulary through reading: A replication of the Clockwork Orange study using second language acquirers. Reading in a Foreign Language, 5(2), 271–275.

- Poehner, M. E., & Lantolf, J. P. (2003). Dynamic assessment of L2 development: Bringing the past into the future. CALPER Working Papers Series, No. 1. The Pennsylvania State University, Center for Advanced Language Proficiency, Education and Research. Retrieved from http://calper.la.psu.edu/publication.php?page=wps1. Accessed August 10, 2013.

- Qian, D. D. (2002). Investigating the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and academic reading performance: An assessment perspective. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 56, 282–308.

- Schmidt, R. W. (2001). Attention. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Cognition and second language instruction (pp. 3–32). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stenberg, R. J., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2002). Dynamic testing: The nature and measurement of learning potential. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In M. Lopez-Morillas, M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (pp. 79–91). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Waring, R., & Takaki, M. (2003). At what rate do learners learn and retain new vocabulary from reading a graded reader? Reading in a Foreign Language, 15, 130–163.

- Watanabe, Y. (1997). Input, intake, and retention: Effects of increased processing on incidental learning of foreign language vocabulary. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 287–307.

- Wesche, M., & Paribakht, T. S. (1998). The influence of task in reading-based vocabulary acquisition: Evidence from introspective studies. In K. Haastrup & A. Viberg (Eds.), Perspectives on lexical acquisition in a second language (pp. 19–59). Lund: Lund University Press.

- Wesche, M., & Paribakht, T. S. (2000). Reading-based exercises in second language vocabulary learning: An introspective study. The Modern Language Journal, 84, 196–213.

- Zahar, R., Cobb, T., & Spada, N. (2001). Acquiring vocabulary through reading: Effects of frequency and contextual richness. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 57(3), 541–572.