Abstract

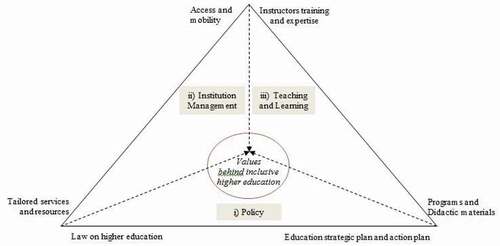

Students with special needs experience various barriers to higher education inclusion that are highly diverse. However, studies examining the challenges of students with special needs in higher education are scattered and fail to address context-based problems. The purpose of this study, thus, was to investigate the challenges and prospects that students’ with special needs experience in Kosovo’s higher education. The study used an analytical framework for understanding inclusive higher education as a (i) policy problem, (ii) management problem, and (iii) teaching and learning problem. The study conducted 10 interviews with institutional management and academic staff, 2 in-depth interviews with students with special needs within higher education, and analysed numerous policy and programing documents at the national and institutional level. The goal of ensuring the full inclusion of students with special needs in higher education requires a multifaceted and long-term approach. This study contributes to the lack of literature by showing that values behind an inclusive higher education and formal efforts towards an inclusive higher education interact as push and pull factors that hinder the inclusive transformations in higher education. Hence, findings recommend strong collaborative efforts between policy, institutional management, and teaching and learning variables, coupled with positive values and attitudes cultivation, to ensure the successful inclusion of students with special needs towards an inclusive higher education environment.

Public interest statement

Inclusion of students with special needs in higher education remains a worldwide challenge. The problem is the lack of shared understanding by relevant higher education stakeholders in how to tackle such challenges. Correspondingly, providing higher education stakeholders (policy-makers, institutional management, academic and administrative staff, and students) with applied knowledge is vital to ensuring the practical inclusion of students with special needs in higher education. This study aimed at understanding the opportunities and challenges for the inclusion of students with special needs and explores how different higher education components (policy, institution management, and teaching and learning) interact to ensure the development of inclusive higher education. The themes and modalities that emerged from this study will help the relevant higher education stakeholders to move beyond just granting physical access to students with special needs and will commit them to implement inclusive policy and practice by ensuring an inclusive higher education practice.

1. Introduction

The past two decades have marked widespread developments in higher education (Marginson, Citation2016). Various studies have confirmed a rapid increase in the demand for higher education (Giannakis & Bullivant, Citation2015; Mok & Neubauer, Citation2015; Powell & Solga, Citation2011; Scott, Citation2005). Nations states have witnessed an expansion in all education levels, resulting in a period of education massification. Higher education institutions stakeholders (management, academic staff, and students), thus, had to cope with the new challenges brought by the “expansionism” (Powell & Solga, Citation2011). Challenges of developing an inclusive higher education can be grouped in terms of stakeholders’ responsibilities as follows: government (group 1), institutional management (group 2), and academic staff (group 3). The three groups of stakeholders are accountable to address, funding in higher education (1), accreditation, diversity and equality, curriculum alignment with labour market needs, enhancing student participation, student employability and social impact (2), and development of students’ professional and intercultural competencies, assessment, student-centeredness (3), among others (see: Brandt, Citation2011; Bunbury, Citation2018; Hanafin et al., Citation2007; Moriña, Citation2017; Mutanga & Walker, Citation2015; Smith, Citation2014).

Amid various responsibilities of higher education, diversity and inclusion have been placed at the forefront of higher education reform discussions (Moriña, Citation2017). While studies confirm that the number of students with special needs in higher education has increased (Majoko, Citation2018), students with special needs experience various barriers to higher education that are as diverse as physical, difficult access to facilities, poor support or lack of facilitation services within the university, lack of funding for additional support, difficulties or other barriers related to rigid curriculum, inappropriate teaching and assessment methods, etc. Hence, the implementation of inclusion principles and the practical involvement of students with special needs in higher education remains a persistent challenge at the global, national, and institutional level (Moriña, Citation2017).

In this article, the term “student with special needs” will be used as the key notion in reference to the education terminology in Kosovo (Zabeli et al., Citation2020). This term includes all students who have difficulties in the learning process and have difficulties accessing the education system in general. Thus, within this notion, no distinction is made between diversity and impairment which are termed “disability”, but in the Albanian language, this term is considered unfitting as it receives negative or offensive connotations (Zabeli et al., Citation2020). Therefore, we will use the notion “students with special needs” to refer to students with “disabilities” (hence the term not preferred in the Albanian language).

1.1. The context of the study

Kosovo’s education system was part of the system of the former Yugoslavia until 1980. In 1990, the entire education system developed separately by two ethnicities (Albanian and Serbian) in which Kosovar Albanians attended “home schools” during the so-called parallel education system (Shatri, Citation2010). Kosovo gained its independence in 2008, and currently, its higher education functions under the Law on higher education no.04/37 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Kosova, Citation2011). Today, higher education in Kosovo is undergoing large-scale higher education reforms (Kaçaniku, Citation2017, Citation2020) and has expanded with 9 public and 22 private universities.

The University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina” is the leading higher education institution in the country with the highest number of Faculties, academic staff and students (Kaçaniku, Citation2017, Citation2020). There are currently 14 faculties within the University of Prishtina (Faculty of Philosophy; Faculty of Mathematical-Natural Sciences; Faculty of Philology; Faculty of Law; Faculty of Economics; Faculty of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Architecture; Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering; Faculty of Mechanical Engineering; Faculty of Medicine; Faculty of Arts; Faculty of Agriculture; Faculty of Sport Sciences and Faculty of Education). Also, the University comprises 900 academic staff and 300 administrative staff are employed and 42,006 students are enrolled (University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”, Citation2020).

Similar to other universities in the region, the University of Prishtina (hereafter UP) is in the process of transformation and continuous change. Faculties, curricula and other academic aspects are aligned with the Bologna Process (Kaçaniku, Citation2020). The reforms have also aimed at developing a learner-centred teaching and learning environment (Zabeli et al., Citation2018). The most important University documents are the Statute and Strategic Plan (2017–2019). The purposes of the UP Statute are to promote the right to education for everyone by indicating that the University shall be obliged to create equal opportunities for all without discrimination (Tahirsylaj, Citation2010). In addition, among seven priorities of the strategic plan (2017–2019), one of them aims to promote diversity by showing the importance of learning about a world with diversity, implementing new strategies to improve diversity and foster a supportive and inclusive climate for all.

While this legislative basis guarantees the right to higher education for all, the question concerns the practical implementation of these documents concerning accommodating students with special needs in Kosovo’s higher education. In fact, there are numerous problems, even barriers of various kinds, which are also reported in research at universities around the world (Brandt, Citation2011; Bunbury, Citation2018; Fuller et al., Citation2004; Hanafin et al., Citation2007; Moriña, Citation2017; Mutanga & Walker, Citation2015; Ramaahlo et al., Citation2018; Ryan & Struhs, Citation2004), and Kosovo, in particular. This is the first study of this kind in the context of Kosovo.

1.2. Literature review

Alongside major changes in the universities around the world, diversity and inclusion present both great opportunities and major challenges for institutions, states, and regions (Smith, Citation2014). In recent years, the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education has increased. According to Majoko (Citation2018), around 10% of the students with special needs have enrolled in higher education. The inclusion of students with special needs in higher education has been facilitated by regulatory policy documents, inclusive physical and social environments, innovative technologies, inclusive program design and delivery, and a shared belief among students with special needs regarding the positive influence of higher education in their future employment and well-being. In addition, Hadjikakou and Hartas (Citation2008) have shown that effective service delivery for students with special needs hinges on accurate information on their needs, sustainability and access to resources and expertise, the existence of an inclusive ethic, a receiving culture of higher education and, also, institutions willingness to anticipate the needs of students, and engage responsibly in inclusive pedagogy. Hence, there are various aspects that higher education institutions should consider to ensure the inclusion of students with special needs.

The education of students with special needs and the implementation of inclusion principles remains a persistent challenge for all levels of education, starting from pre-school to higher education (Moriña, Citation2017; Mortier et al., Citation2010; Ypinazar & Pagliano, Citation2004). For pre-university education, debates arise over whether special education or regular (inclusive) education should be provided to students with special needs. In light of this debate, various studies report on both the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, i.e. special school or regular school approach (Boer et al., Citation2011; Miles & Singal, Citation2010; Mortier et al., Citation2010; Ypinazar & Pagliano, Citation2004). Similar discussions arise regarding alternative approaches to inclusive higher education. A general rule of thumb would indicate that if students who received support in the pre-university education system should receive even greater support in higher education. On the contrary, the reality of higher education meeting the needs of students with learning difficulties is discouraging, considering the fact that this group of students receives less support in higher education as compared to pre-university education (Riddell & Weedon, Citation2011). Studies show that students with different learning disabilities face many barriers to higher education and this poses various challenges for the future, both for students and the academic staff within universities (Brandt, Citation2011; Bunbury, Citation2018; Fuller et al., Citation2004; Hanafin et al., Citation2007; Moriña, Citation2017; Mutanga & Walker, Citation2015; Ramaahlo et al., Citation2018; Ryan & Struhs, Citation2004). Therefore, inclusion for students in higher education is considered a major issue for universities.

While there is an abundance of research on the education of students with special needs in the pre-university education system (see for example, Boer et al., Citation2011; Loreman et al., Citation2014; Miles & Singal, Citation2010; Mortier et al., Citation2010; Watkins & Ebersold, Citation2016; Ypinazar & Pagliano, Citation2004), existing research on the education of students with special needs in higher education is recent and limited. The literature recognizes three groups of perspectives when examining the issues related to achieving inclusive higher education, as follows: 1) inclusive higher education as a policy problem tackling the lack of inclusive higher education policy implementation and identifying alternatives to improving higher education prospects for students with special needs, 2) inclusive higher education as an institutional management problem focusing on institutional regulatory frameworks, priorities, and organizational culture that influence physical and other higher education environment opportunities and challenges for the inclusion of students with special needs, and 3) inclusive higher education as teaching and learning problem regarding the identification and analysis of specific student learning difficulties and barriers (for instance: curriculum design and delivery) for both students and staff and identification of potent approaches to addressing them.

In the first group of literature, Brandt (Citation2011) identifies the experiences of students with special needs in Norway in relation to inclusive policy goals and challenges to implementing them. The study concluded that while inclusive policy has significantly influenced students with special needs, such attempts have to be coordinated and constant support should be provided to students within institutions. In other words, an inclusive higher education policy as a detached variable cannot be effective. Similarly, Mutanga and Walker (Citation2015) attempted to understand productive approaches to inclusive higher education policy, suggesting that regardless of policy interventions, students with special needs continue to experience various barriers to higher education. In addition, other studies suggest the need for a tailored inclusive policy framework to guide higher education institutions during their support of students with special needs (Ramaahlo et al., Citation2018).

Regarding the second group of literature, Fuller et al. (Citation2004) identified several higher education access and participation barriers of students with special needs, such as lack of tuition waivers, additional services, dormitory, and transportation. The study discusses the perspectives of students with special needs on how higher education environment can employ both structural and value-driven ways to ensure their full inclusion. The study concludes by recommending future studies to investigate institutional culture towards more inclusive higher education. Correspondingly, Hanafin et al. (Citation2007) revealed specific restricting aspects of the higher education environment on educating students with special needs, rather than the general physical access to higher education. They identify inadequate access in higher education conceptualizations regarding special needs students and support the need for establishing a common understanding. Also, Hughes et al. (Citation2016) explore experiences with already enrolled students with chronic illnesses on how are their needs met and how this process can be improved in the broad sense of higher education environment.

Last but not least, within the third group of literature, Ryan and Struhs (Citation2004) sought to identify students with physical or sensory disability and examined their prospective in higher education, in general, and specific fields of study. Furthermore, Savvidou (Citation2011) clusters the narratives of the academic staff and their involvements and barriers of teaching English to groups of students with physical and learning difficulties. Moreover, Kochung (Citation2011) has depicted additional barriers on teaching and learning, ranging from lack of appropriate teaching methodologies used by the instructors, negative attitudes received from academic staff and student colleagues, formal exams being at the forefront of an assessment strategy, content-based teaching and learning is promoted, among others. In addition, Kioko and Makoelle (Citation2014) show various learning experiences of students with special needs in higher education. Their study emphasizes the need to abandon the current use of rigid curriculums and formal examination systems since it prevents inclusive teaching and learning. Moriña (Citation2017) argues that although constant awareness for inclusion in higher education might have eliminated the immediate physical barriers, higher education institutions have not been able to address problems related to lack of inclusive curricula, formal teaching, learning, and assessment approaches, preventing a full involvement of students with special needs. Additional studies focused on the relevance of implementing inclusive curriculum to change attitudes to cultivate sustainable inclusion in higher education (Bunbury, Citation2018).

As has already been discussed, the literature confirms that students with special needs experience various barriers to higher education that are as diverse as physical, difficult access to facilities, poor support or lack of facilitation services within the university, lack of funding for additional support, difficulties or other barriers related to rigid curriculum, inappropriate teaching and assessment methods, etc. Brandt (Citation2011) however reported that the existing literature is scattered, inhibiting researchers to undertake studies that can clearly illustrate and influence the current situation in students with special needs. Additionally, Kioko and Makoelle (Citation2014) have argued that the current literature tries to deal with complex undertakings that move away from simple and context-based problems to address the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education. The goal of ensuring the full inclusion of students with special needs in higher education requires a multifaceted and long-term approach set against a “quick fix” (Moriña, Citation2017). Hence, this study contributes to the lack of literature by using the three stakeholder-relevant groups: 1) policy level, 2) higher education institutional management level, and 3) teaching and learning level (programs, academic staff, and students) as a guiding framework to investigate the whole picture of prospects and challenges towards the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education in Kosovo.

2. Methods

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the challenges and prospects that students’ with special needs experience in Kosovo’s higher education. Specifically, the study is situated within initial teacher education considering its leading role in building an inclusive higher education environment.

The study addresses the following research questions:

What are opportunities and challenges for the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education in Kosovo?

In what ways do policy, institution management, and teaching and learning influence the development of inclusive higher education?

The study uses qualitative methods grounded on phenomenological research paradigm (Cohen et al., Citation2018). According to Marshall and Rossman (Citation2016), there are several purposes as to why researchers focus on phenomenological research paradigm, namely: 1) study of culture and society, 2) investigation on the lived experiences of individuals, 3) attention on texts and conversation, to name few. Moreover, Cohen et al. (Citation2018) have suggested that while there are alternative ways to approach the phenomenological paradigm, there is a consensus among researchers on its following characteristics:

A belief in the importance, and even the primacy, of subjective consciousness

The importance of documenting and describing immediate experiences

The significance of understanding how and why participants’ knowledge of a situation comes to be what it is

The social and cultural situatedness of actions and interactions, together with participants’ interpretations of a situation

An understanding of consciousness as active, as meaning bestowing

A claim that there are certain essential structures to the consciousness of which we gain direct knowledge by a certain kind of reflection (Cohen et al., Citation2018, pp. 20–21).

Hence, qualitative methods grounded on phenomenological research paradigm were considered appropriate since our study focuses on different higher education stakeholders’ experiences, attitudes and perceptions regarding the opportunities and challenges of the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education.

2.1. Sample

The study focused on three groups of stakeholders in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the situation of students with special needs in higher education in Kosovo. The University of Prishtina was selected as the sample institution, considering that it was the first established University in Kosovo, has the largest number of students, staff and academic staff, and is a leading institution in the region (Kaçaniku, Citation2017, Citation2020; Shatri, Citation2010; Tahirsylaj, Citation2010). Also, the Faculty of Education was selected as a sample academic unit because its programs indicate promising grounds for inclusive education. provides details of the study sample.

Table 1. Study sample details

Table 2. Themes and sub-themes from content analysis (policy problem)

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes from content analysis (institutional management problem)

Table 4. Themes and sub-themes from content analysis (teaching and learning problem)

2.1.1. Higher education policy

The documents under this group of stakeholders are in the corpus of higher education policy, which regulate general aspects of higher education in Kosovo. Purposive sampling was used to identify the main documents regulating and planning higher education in Kosovo (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Creswell, Citation2014). The sampled documents are open sources that are easily accessible to the public.

2.1.2. Higher education institutional management

In order to better examine this group of stakeholders, both document analysis and interviews were used. The main documents regulate to internal matters of the university and were selected using purposive sampling (Cohen et al., Citation2018). As such, the vice-dean responsible for academic and teaching issues at the institutional level and the quality assurance coordinator at the institutional level were interviewed. Interviews with Vice deans and quality assurance coordinators stressed management challenges and approaches to inclusive higher education. Interviews lasted about an hour each, were audio-recorded, and transcribed verbatim. It should be noted that the initial plan was to involve more management representatives. However, we have faced tremendous barriers and resistance from the institutional management side. Cohen et al. (Citation2018) certify that resistance and access to study respondents can be challenging, especially when dealing with sensitive topics.

2.1.3. Teaching and learning

Similar to higher education management group of stakeholders, teaching and learning also used documents analysis and interviews. Also, for this cluster of representatives, in-depth interviews were deemed important. According to Matthews and Ross (Citation2010), in-depth give a face to human problems. Both document analysis and interviewees were selected with purposive sampling (Cohen et al., Citation2018; Creswell, Citation2014). To select (N = 2) study programs, study level was used as a criterion to examine one Bachelor and one Master’s program. In addition, maximum variation sampling was used to select academic staff that currently teach in different programs, program levels (BA/MA), courses, and disciplines (Creswell, Citation2014; Given, Citation2008). Lastly, total population sampling was used to select students with special needs already participating in higher education (Given, Citation2008). Students were attending the last year of their studies, student 1 (Bachelor) and student 2 (Master) when in-depth interviews were conducted. Interviews lasted about an hour each, while in-depth interviews about two hours each. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Similar barriers were experienced also with academic staff who suggested they do not feel conformable and knowledgeable enough to participate in our study. Resistance and access to study respondents can be challenging, especially when dealing with sensitive topics like ours (Cohen et al., Citation2018). While an opposite situation transpired with organizing in-depth interviews with special needs students, who were highly enthusiastic to discuss their experiences attitudes and feelings about challenges and inclusion possibilities in higher education.

2.2. Data coding and analysis

Data coding and analysis followed a thematic analysis (Matthews & Ross, Citation2010). In analysing the transcribed interviews and document text, the coding approach was applied. The interviews were first transcribed verbatim and document text was selected and entered into ATLAS.ti qualitative software to conduct the analysis. To analyse the data, the following cluster categories served as a guiding framework: (1) higher education policy, (2) higher education institutional management, and (3) teaching and learning. The study generated various themes and open coding.

3. Findings

This section presents findings from both document analysis and interviews. As presented in the methodology, the transcribed interviews and documents were analysed using the thematic analysis. Findings convey important themes that are presented in three main clusters, namely (1) inclusive higher education as a policy problem, (2) inclusive higher education as an institutional management problem, and (3) inclusive higher education as teaching and learning problem and coded data were organized in the tables presented in sections dedicated to each cluster.

3.1. Inclusive higher education as a policy problem

This subsection presents themes: Exclusion mindset and Inclusive policy as part of a larger policy problem preventing an inclusive higher education. The themes are described in detail in the and the analysis presents direct statements from interviewees.

3.1.1. Exclusion mindset

The data conveys that Kosovo society, in general, carries a negative approach regarding the possibilities of engaging future teachers with special needs in the schooling system. Such a result indicates that, regardless of the existing inclusive policy, the mass mindset sometimes is more powerful and dictates students’ exclusion. A statement from a student confirms the societal barriers as follows:

In general, I have experienced infrastructural access in higher education. However, the problem is that I can sense a general doubt about the possibilities of me being a future teacher. I can clearly state that the problem now begins with barriers to access to the labour market. Being a teacher with special needs is a situation that is difficult to be accepted in the Kosovo context. (Interviewee, 6)

The statement supports that there is a societal hesitation about students’ with special needs abilities and their potential to be successful. Clearly, the results show a negative understanding of accepting teachers with special needs indicating lack of societal readiness to accept teachers with special needs. An academic staff showed that:

As a society, we still have problems accepting teachers with special needs in the school system. I believe that even when the municipality and the school would grant prospective teachers with special needs the opportunity to get involved, the parents would be a strong opposing group. (Interviewee, 4)

This statement shows that not only students but also academic staff understand the existing hesitation and possible resistance about future teachers with special needs entering the school system. This shows that various contextual barriers are guided by a mindset and a values system that hint reluctance about the true inclusion of students with special needs.

3.1.2. Inclusive policy

In its attempt to joining the European Union, Kosovo has harmonized its education policies. As such, the document analysis has shown that the national policy framework guarantees an inclusive higher education (Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. (MEST), Citation2016). Inclusion has been considered a priority goal in policy documents. For instance, some of the principles by the Law on higher education guarantee:

1.2. Equality before the law of all bearers of higher education

1.3. Equal opportunities for all students and staff in higher education institutions without discrimination

1.4. Diversity and quality in programmes of study and in support of learning (Official gazette of the Republic of Kosova, p. 1).

However, while more focus is dedicated to the inclusion of pupils in pre-University, there is a lack of tailored inclusive higher education policy. An academic staff indicates that:

There is a need to institutionalize and develop internal institutional mechanisms to ensure the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education and beyond. (Interviewee, 3)

This statement confirms similar results that there is a lack of existing strategies and personalized approaches in higher education institutions to address students’ inclusion. Another academic staff argues that:

Today, institutions have been burdened with bureaucracies and formalities that have moved the attention away from substantial aspects such as inclusive higher education. (Interviewee, 9)

As such, the results confirm that the development of an inclusive policy is not considered an institutional priority. Another interviewee argues that:

The inclusion of students with special needs within higher education is never seen as a priority in our strategies and is considered to be something very difficult to be accomplished and as a result, nothing is done in that direction. The Faculty of Education must operate as a role model in order to raise awareness about students with special needs capabilities and potentials. However, I think that we as a Faculty are currently failing in that regard. (Interviewee, 4)

The findings support the conclusion that inclusive policy is only superficial and operates at a formal level. There is a lack of action plans and individualised tailored growth policy plans for students with special needs in higher education.

3.2. Inclusive higher education as a management problem

This subsection presents themes: University entry barriers, Welcoming infrastructure, and Resource focused that were identified as institutional management problems within higher education and teacher education. The themes are described in detail in the and the analysis presents direct declarations from the interviewees.

3.2.1. University entry barriers

The findings convey that higher education poses barriers for prospective students in ways which entrance exam is organised. The entrance exam is offered in a formal format of multiple-choice questions that limits various prospective students to undertake it. An academic staff belies that:

We as an institution do not offer alternative opportunities for students with special needs to undertake the entrance exam. We as staff have received requests from specific individuals and we have tried our best to accommodate them. But this does not justify the fact that entry into higher education is an issue that is not regulated at the institutional level but depends on individual staff willingness. (Interviewee, 1)

This statement indicates that there is no prior consideration for accommodating students with special needs unless there are individual student cases that demand special services. Furthermore, the results show that there is a lack of institutionalized inclusion in the absence of institutional guided special services, an office that addresses students’ needs, tailored counselling services, and student orientation services. As such, a student suggests that:

I am very satisfied with Professors that have responded positively to my requests. However, since there is no regulation to assure my access and inclusion in higher education, not all Professors and administrative staff welcome my requests with a positive attitude and sometimes I feel excluded. (Interviewee, 2)

Hence, as long as there is a lack of institutionalized regulations and strategies to treat the inclusion of students with special needs into higher education, there will always be cases of student exclusion.

3.2.2. Welcoming infrastructure

The results have confirmed that the infrastructure of the institution is its strong suit when it comes to cases of students with special need inclusion. There is a consensus among the interviewees that the institution meets minimum inclusive infrastructure requirements (criteria) set by standards. A student reveals a story about how welcoming the institutional infrastructure is and how it influenced her application and enrolment:

The Faculty of Education has physical entry advantages over other Faculties. When I was diagnosed with this disability, I realized that later on, it will get worse. I have researched Faculties that only had the available physical (infrastructural), such as having the steep slope, the elevators, and more accessible hallways, since for me it was important to have access and physical space to move around with a wheelchair. Therefore, my decision of choosing a degree was not because of my interest, but because of the available infrastructure. However, when the elevator was not functional from time to time, I experienced serious difficulties to attend lectures and tutorials. (Interviewee, 6)

This discussion reveals an interesting result from students with special needs side, the main indicator of their decision to enter higher education is related to physical access. As the interviewer purported, the Faculty of Education is the only institution that has provided the necessary infrastructure for students’ inclusion in higher education. The investments made to the building infrastructure have facilitated better access for students’ and ensure student mobility within institutional premises. Moreover, a member from institution management argued that:

Physical inclusion of students with special needs in higher education does not mean that they are fully involved with the full meaning of inclusion. We as an institution fail to employ different modalities of involving students with special needs that go beyond physical access, such as developing a questionnaire with students to identify eventual needs of students who have not been declared marginalized, opening an advisory office for students with specific problems, encouraging students to support each other, organizing teamwork through joint projects, eliminating barriers to communication, and organizing different clubs for extracurricular activities, etc. (Interviewee, 9)

3.2.3. Resource focused

There was a consensus among the interviewees that in order to ensure inclusive higher education, adequate human and financial resources are necessary. There is a general resource orientation approach when it comes to addressing inclusion problems from the perspective of inclusion as a management problem. A representative from the management argued about the limited resources to accommodate the requests of students with special needs as follows:

I would say that little has been done and that most of our students who have learning disabilities or have special needs have no real place to go within the Faculty or University for any particular service. For example, in our libraries, there is no literature which is easily accessible for students with visual impairments or blind students. Furthermore, we do not have literature that is in the Braille alphabet. And for students who have hearing difficulties or deaf students, we do not have sign language interpreters and other relevant instruments. So, we do not have any form, service or assistance that makes it easier for students to reach their maximum potential. (Interviewee, 4)

To do all of this, it is normally necessary to prioritize this issue and put it as a separate activity in an action plan that we aim to achieve and allocate the resources needed to create such a mechanism. (Interviewee, 4)

This indicates that management decisions revolve around the availability of resources and lack thereof. In other words, the availability of resources is considered an important indicator of management that determines inclusion within the higher education institution.

3.3. Inclusive higher education as teaching and learning problem

The following themes have derived from the analysis: Inclusion as a formality, Teacher educator readiness, Tailored teaching and learning, and Collective efforts. These themes represent barriers and opportunities regarding teaching and learning cluster. The themes are summarised in the and extensively discussed throughout the section.

3.3.1. Inclusion as a formality

The results give the impression that the inclusion of students with special needs is only treated as a formality. A faculty member considers that only structural inclusion has guided the reforms in higher education.

I would not say we provide specific services for students with special needs. What is currently possible is student access i.e. both ramps to the Faculty entrance and elevator access. But, of course, this is not enough! Our students with special needs do not benefit from any other services, that is to say, they do not benefit from any assistance provided by special assistants or do not have an office where they can turn to for any form of counselling or for diverse needs they might have. This reflects that our Faculty has only accomplished to ensure access to lectures and access to the Faculty’s premises. So, I would say that little has been done and that most of our students who have learning difficulties or have special needs have no real place to go within the Faculty for any particular service. (Interviewee, 4)

This analysis of a faculty member suggests that higher education institutions should engage in more substantial forms of assistance that aid the true inclusion of students, especially in aspects concerning teaching and learning. However, on a more positive note, a member of the management staff claimed that:

The Faculty of Education is open for the admission of all students without distinction. Content-wise, all BA and MA programs have included at least one subject that promotes inclusive education. The accreditation process encouraged the design of a Master’s level program on inclusive education that welcomes teachers from different backgrounds (Interviewer, 9)

This report suggests that there are ways in which the Faculty of Education has attempted to cultivate an inclusive environment. Courses as such are intended to develop an inclusive education philosophy that will be carried out through different generations and, ultimately, influence society. As a consequence, an academic staff has pointed out that:

Inclusive education courses can be a step towards increasing collective awareness. (Interviewee, 8)

However, while there is a positive attitude about the importance of such course in developing an inclusive culture, there is a consensus that inclusive courses and access into Faculty’s building can only be perceived as a formality. A student with special needs explains that:

Higher education institutions cannot simply consider themselves inclusive when they only provide access to the building or classroom for students with special needs. I haven’t had a problem getting into the facility or the classroom; even on the entrance exam, I have been granted the opportunity to ask a family member to help with reading entrance exam questions and writing my answers on the exam. However, inclusion does not only mean access but also encompasses many other aspects. For example, lack of literature is a major aspect that I have encountered or lack of a computer that reads text for the blind. In principle, I think there is no inclusive culture within higher education. Inclusion does not mean when professors favour a student with special needs with higher grades or in other cases when they discriminate him/her because of their disability to reading the required literature. (Interviewee, 2)

Therefore, access and courses on inclusive education alone cannot ensure inclusive higher education.

3.3.2. Academic staff readiness

Results hint towards a general understanding that only a few teacher educators show willingness to assist students both physical and practical inclusion. An academic staff argues that inclusion is not an ad hoc process and should be regulated at the institutional level:

I believe many of these issues related to inclusion depend on the mindset and individuals willingness. However, we should not depend on individual staff willingness to lead inclusion processes forward. There should be a functional mechanism instituted within the Faculty of Education, to serve as a model for other higher education institutions inclusion. (Interviewee, 3)

Moreover, a member of the management staff has questioned the level of professionalism of the staff to handle the teaching and learning of student with special needs.

We as an institution have not yet been able to handle and realize inclusion in the full sense of this word because of staff not prepared to deal with students with special needs. (Interviewee, 8)

In a more narrow sense of teaching inclusive courses, there is a lack of common understanding among academic staff regarding the main concepts and notions related to inclusion and inclusive education. As such, the following statement confirms the need for further efforts.

There is a lack of adequate staff to teach inclusive education subjects and also lack of understanding and application of inclusive principles by all staff regardless of professional background. There is an urgent need for academic staff capacity-building activities. (Interviewer, 10)

3.3.3. Tailored teaching and learning

Regarding the possibility to offer tailored teaching and learning, a representative from management indicates the urgency of this matter:

We cannot talk about generic modalities as we have to treat each student with special needs as an individual and to shape an individual approach in order to address their needs. (Interviewer, 4)

Furthermore, academic staff find it challenging to work with special needs students. An academic staff suggests that

Yes, it is difficult, the very nature of the human being is very complex, with the addition of disability then the situation becomes even more complicated. The biggest difficulties come from societal prejudice. This can influence students with disabilities to distance themselves during the process of teaching and learning. However, we as academic staff should strive to find tailored ways to involve students with special needs inside the classroom activities (Interviewer, 1)

Regarding students with special needs perceptions, they can vary depending on the individual student experience. For instance, a student explained a good experience with a professor:

For example, during class discussions, one of the professors asks us to come out on the whiteboard and write the key points from our reflections. When I was allowed to express my reflection, I told the professor that I was not able to come up to the board because of my condition. But in this case, the professor has told me to express my opinion while he writes that on the whiteboard. This experience has made me feel equal to all my fellow colleagues. So, I was given the opportunity to discuss and challenge other classmates’ opinions and engage in discussion within the entire classroom. (Interviewer, 6)

However, the analysis of the interviews has indicated also not such positive student experiences.

Professors in most cases have made inadvertent mistakes, meaning they did not involve me in the teaching and learning process. For example, one might mention a bad experience when the professor has read from the slide or presented the statistical tables derived from SPSS. In this case, though unintentionally, I could not feel included when the instructor kept referring to tables and I cannot see. (Interviewer, 2)

Another situation can be mentioned when we had a guest lecturer on a subject. The guest lecturer presented through slides and at one point displayed a story that required us to be silent and to read. Due to my inability to see and read, at that moment, I felt excluded from learning, as all colleagues began to read the text quietly until one colleague reminded the mass that I am not able to see and someone had to read the slides from the story. In this case, the presenter had begun reading for me. I will never forget that story (laughs). (Interviewer, 2)

The results, thus, show that there is a variation between different experiences and tailored teaching and learning is ad hoc and inconsistent, depending on individual staff efforts.

3.3.4. Collective efforts

The final theme within teaching and learning cluster urges all member of the higher education community to find alternative ways which facilitate the inclusion of students with special needs. It has been collectively argued that inclusion is not an easy process and takes time, recourses, and continuous dedication. A representative from the management of the institution recommends the following:

As a community of higher education, we have to find different ways and projects through which we can engage students with special needs. At the same time, through such projects, we can create an inclusive culture that highlights the importance of students with special needs being an integral part of higher education and society. (Interviewer, 9)

Largely, there was a collective understanding among the interviewees that collaborative projects and activities among stakeholders have significant influence toward removing societal prejudices. Furthermore, the collective involvement of the entire community follows a process in which awareness-raising initiatives are promoted. Hence, all these declarations together confirm that collaborative efforts can make students with special needs feel equal and empowered, as well as active members within the higher education community.

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the challenges and prospects that students’ with special needs experience in Kosovo’s higher education. Specifically, the study was situated within initial teacher education considering its leading role in building an inclusive higher education environment.

Findings show that while higher education has managed to formally ensure the inclusion of students with special needs, societal and individual value manifestations have a stronger influence. This is influenced by individuals and groups values behind inclusive higher education. Consequently, values behind an inclusive higher education and formal efforts towards an inclusive higher education interact as push and pull factors that hinder the inclusive transformations in higher education (see a detailed presentation of the findings in ). Hence, findings support that strong collaborative efforts between policy, institutional management, and teaching and learning groups, coupled with positive values and attitudes cultivation, will ensure the successful inclusion of students with special needs towards developing an inclusive higher education environment.

First, at the i) policy level, the results present two contradictory higher education efforts. On the one hand, higher education system ensures an inclusive higher education through a well-developed Law on higher education and an Education strategic plan and action plan. However, on the other hand, results purport a general societal hesitation and doubt reflected within values behind inclusive higher education that produces practical exclusion of students with special needs from the higher education system. Similar results have been discussed in the literature by Mutanga and Walker who confirm that inclusive higher education policy as a standalone variable cannot be effective (Mutanga & Walker, Citation2015). This line of arguing is also supported by other researchers’ endorsing that regardless of properly drafted inclusive higher education policies, students with special needs will continue to encounter barriers related to quality teaching and learning (Brandt, Citation2011; Ramaahlo et al., Citation2018). Hence, our first finding supports the first recommendation that the higher education system needs to move beyond the provision of formal inclusive policy.

Second, at the ii) institution management level, management priorities and inclusive attitudes contradict with the institutional welcoming infrastructure. Although findings confirm that the institution ensures access and mobility for students with special needs, institutional management promotes a passive attitude, whereby failing to prioritise other aspects of inclusive higher education that go beyond access and mobility. While in the past, more studies have reported higher education physical entry barriers (Fuller et al., Citation2004), recent studies discuss higher education entry barriers that exceed general physical access to higher education (Hanafin et al., Citation2007). In order to address such barriers, our study respondents have collectively discussed the need to provide counselling services that are available at students’ disposal. This finding corresponds with Moriña’s finding on the importance of counselling and tailored services, such as tutoring, special orientation sessions, and support groups with faculty and students, among others, that are provided to students with special needs (especially during the early months of their studies) (Moriña, Citation2017). As a result, our study recommends that higher education institutions management needs to prioritise and dedicate their efforts and resources to achieving full inclusion of students with special needs into higher education.

Third, at the iii) teaching and learning level, academic staff generally shares positive attitudes concerning the inclusion of students with special needs in higher education. However, most of them lack the necessary training and expertise to productively engage students with special needs within the classroom context. Kochung (Citation2011) has correspondingly depicted barriers related to inadequate teaching methodologies in higher education. Furthermore, our findings have identified that lack of tailored study programs and didactic materials (including literature, the Braille Alphabet, hearing apparatuses, to name few) inhibit academic staff to properly facilitate student teaching and learning. In this context, various researchers have argued that rigid curriculums, formal assessment criteria, and lack of innovative and engaging teaching and learning approaches will serve as barriers for the full inclusion of students with special needs in higher education (Kioko & Makoelle, Citation2014; Moriña, Citation2017; Ryan & Struhs, Citation2004; Savvidou, Citation2011). As such, regardless of their positive values and attitudes about achieving an inclusive higher education, as long as academic staff have limited capacities and resources, they will not achieve inclusive teaching and learning goal. Therefore, our study suggests that higher education institutions should constantly support academic staff to achieve their teaching and learning objectives through embedding lifelong inclusive professionalism.

4.1. Limitations and future research

Although our study contributes to the field, it has some limitations. The study was based on one higher education institution. It conducted 12 interviews with management and academic staff, and students (due to the extensive hesitation of study respondents to participate) and examined numerous policy and programing documents at the national and institutional level. Moreover, the study was conducted only in the context of Kosovo’s higher education.

This study, nevertheless, can be used to frame additional research that could be generalized to a larger population in higher education systems. Consequently, there is great potential for future studies in this field. Firstly, studies with larger and representative samples are welcomed. Secondly, comparative studies that cover a range of contexts can offer a bigger picture of the issue at the global higher education setting. Lastly, intervention studies in the frame of action research are endorsed to introduce new and inclusive practices in higher education and evaluate potential changes incurred.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, higher education institutions should dedicate their efforts towards initiatives that provide more than just assuring access and mobility to students with special needs. Institutions should commit to implementing inclusive policy and practice by ensuring resource availability and tailored services to students with special needs. Moreover, higher education institutions are also responsible for restructuring study programs design and delivery. This effort will ensure the organizing of academic staff training and guarantying the availability and application of didactic materials and other learning resources and tools towards quality teaching and learning. In addition, higher education institutions should identify means aimed at ensuring the cultivation of shared values and attitudes for inclusive higher education. All in all, higher education institutions should treat students’ diversity and inclusion with appreciation considering that all stakeholders involved will gain a fruitful teaching and learning experience that guarantees a mutual transformation.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fjolla Kaçaniku

Naser Zabeli is Associate Professor and Head of Pedagogy Department at the University of Prishtina’s Faculty of Education in Kosovo. His research interest focuses on inclusive education and effective teaching and learning. He authored and co-authored several scientific articles, as well as various books and monographs, including his tremendous contribution to adopting the Index of Inclusion for Kosovo context needs.

Fjolla Kaçaniku is a PhD researcher at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Education and a Teaching Assistant at the University of Prishtina’s Faculty of Education in Kosovo. Her research interest focuses on teacher education policy and initial teacher professionalism.

Donika Koliqi is a Teaching Assistant at the University of Prishtina’s Faculty of Education in Kosovo. Her research interest focuses on inclusive education and teaching and learning theory. Currently, she is a PhD student in the field of inclusive education at the University of Prishtina, Faculty of Education.

References

- Boer, A., Pijl, S. K., & Minnaert, A. (2011). Regular primary schoolteachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15(3), 331–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110903030089

- Brandt, S. (2011). From Policy to Practice in Higher Education: The experiences of disabled students in Norway. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 58(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2011.570494

- Bunbury, S. (2018). Disability in higher education – Do reasonable adjustments contribute to an inclusive curriculum? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 24(9), 964-979. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1503347

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Fuller, M., Bradley, A., & Healey, M. (2004). Incorporating disabled students within an inclusive higher education environment. Disability & Society, 19(5), 455–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000235307

- Giannakis, M., & Bullivant, N. (2015). The massification of higher education in the UK: Aspects of service quality. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 40(5), 630–648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.1000280

- Given, L. M. (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Sage Publications.

- Hadjikakou, K., & Hartas, D. (2008). Higher education provision for students with disabilities in Cyprus. Higher Education, 55(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9070-8

- Hanafin, J., Shevlin, M., Kenny, M., & Neela, E. M. (2007). Including young people with disabilities: Assessment challenges in higher education. Higher Education, 54(3), 435–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9005-9

- Hughes, K., Corcoran, T., & Slee, R. (2016). Health-inclusive higher education: Listening to students with disabilities or chronic illnesses. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(3), 488–501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107885

- Kaçaniku, F. (2017). The impact of the Bologna process in Kosovo: Prospects and challenges. Journal of the European Higher Education Area, 8(4), 57–76. https://www.ehea-journal.eu/en/handbuch/gliederung/#/Beitragsdetailansicht/483/1820/The-Impact-of-the-Bologna-Process-in-Kosovo—Prospects-and-Challenges

- Kaçaniku, F. (2020). Towards quality assurance and enhancement: The influence of the Bologna Process in Kosovo’s higher education. Quality in Higher Education, 26(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2020.1737400

- Kioko, V. K., & Makoelle, T. M. (2014). Inclusion in Higher Education: Learning Experiences of Disabled Students at Winchester University. International Education Studies, 7(6), 106–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n6p106

- Kochung, E. J. (2011). Role of Higher Education in Promoting Inclusive Education: Kenyan Perspective. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 2(3), 144–149. http://jeteraps.scholarlinkresearch.com/articles/Role%20of%20Higher%20Education%20in%20Promoting%20Inclusive%20Education.pdf

- Loreman, T., Forlin, C., Chambers, D., Sharma, U., & Deppeler, J. (2014). Conceptualising and Measuring Inclusive Education. Measuring Inclusive Education, 3, 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620140000003015

- Majoko, T. (2018). Participation in higher education: Voices of students with disabilities. Cogent Education, 5(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2018.1542761

- Marginson, S. (2016). Higher Education and the Common Good. MUP Academic.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2016). Designing Qualitative Research (sixth edition). Sage.

- Matthews, B., & Ross, L. (2010). Research methods: A practical guide for the social sciences. Pearson Longman.

- Miles, S., & Singal, N. (2010). The Education for All and inclusive education debate: Conflict, contradiction or opportunity? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802265125

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology. (MEST). (2016). Kosovo Education Strategy Plan 2017-2021. Prishtina, Kosovo: MEST. http://www.kryeministri-ks.net/repository/docs/KOSOVO_EDUCATION_STRATEGIC_PLAN.pdf

- Mok, K. M., & Neubauer, D. (2015). Higher education governance in crisis: A critical reflection on the massification of higher education, graduate employment and social mobility. Journal of Education and Work, 29(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1049023

- Moriña, A. (2017). Inclusive education in higher education: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2016.1254964

- Mortier, K., Van Hove, G., & De Schauwer, E. (2010). Supports for children with disabilities in regular education classrooms: An account of different perspectives in Flanders. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(6), 543–561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504929

- Mutanga, O., & Walker, M. (2015). Towards a Disability-inclusive Higher Education Policy through the Capabilities Approach. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 16(4), 501–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19452829.2015.1101410

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Kosova. (2011). Law No.04/L-037 on higher education in the Republic of Kosovo. Prishtina, Kosovo: Assembly of Kosovo. https://masht.rks-gov.net/uploads/2015/06/02-ligji-per-arsimin-e-larte-anglisht.pdf

- Powell, J. W., & Solga, H. (2011). Why Are Higher Education Participation Rates in Germany so Low? Institutional Barriers to Higher Education Expansion. Journal of Education and Work, 24(1–2), 49–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2010.534445

- Ramaahlo, M., Tönsing, K. M., & Bornman, J. (2018). Inclusive education policy provision in South African research universities. Disability & Society, 33(3), 349–373. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1423954

- Riddell, S., & Weedon, E. (2011). Access to higher education for disabled students: A policy success story? In S. Haines & D. Ruebain (Eds.), Education, disability and social policy (pp. 131–146). Policy Press.

- Ryan, J., & Struhs, J. (2004). University education for all? Barriers to full inclusion of students with disabilities in Australian universities. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 8(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360311032000139421

- Savvidou, C. (2011). Exploring teachers’ narratives of inclusive practice in higher education. Teacher Development: An International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 53–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2011.555224

- Scott, P. (2005). Mass Higher Education – Ten Years on. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 9(3), 68–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13603100500207495

- Shatri, B. (2010). Arsimi shqip në Kosovë 1990-1999: Shtëpitë Shkolla-Sfidat, arritjet dhe aspiratat [Albanian education in Kosovo 1990-1999: House-schools-Challenges, achievements, and aspirations]. Libri Shkollor-Prishtinë.

- Smith, D. G. (2014). Diversity and Inclusion in Higher Education: Emerging perspectives on institutional transformation. Routledge.

- Tahirsylaj, A. (2010). Higher Education in Kosovo: Major Changes, Reforms, and Development Trends in the Post-Conflict Period at the University of Prishtina. Interchange, 41(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-010-9117-0

- University of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”. (2020). 50 years of University of Prishtina. Universitry of Prishtina “Hasan Prishtina”.

- Watkins, A., & Ebersold, S. (2016). Efficiency, Effectiveness and Equity within Inclusive Education Systems. International Perspectives on Inclusive Education, 8, 229–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-363620160000008014

- Ypinazar, V., & Pagliano, P. (2004). Seeking inclusive education: Disrupting boundaries of “special” and “regular” education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 8(4), 423–442. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1360311042000273746

- Zabeli, N., Anderson, J., & Saqipi, B. (2018). Towards the Development and Implementation of Learner-centered Education in Kosovo. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(4), 49–64. https://jsser.org/index.php/jsser/article/view/354/346

- Zabeli, N., Shehu, B. P., & Gjelaj, M. (2020). From segregation to inclusion: The case of Kosovo. International Journal of Sociology of Education, 12(2), 201–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14658/pupj-ijse-2020-2-9