Abstract

The Apinayé are a Brazilian indigenous ethnic group that live in a transition zone between the Cerrado and the Amazon. This study primarily aims to understand the meaning that art holds for Apinayé indigenous students at a Brazilian Indigenous School. We used an ethnographic research methodology, while also observing art classes and distributing open questionnaires to these students. The results showed that the arts produced by the indigenous people mostly refer to the body paintings and cultural artifacts they produce, such as necklaces made of beads, fans, coufo, and babassu coconuts, among others. In addition, the indigenous people characterize the Brazilian indigenous culture as something that is extremely significant for their lives, as art represents not only their reality but also their history, struggle, and resistance. Finally, the study suggests that the discipline of art in the indigenous school can help the students understand that the handicrafts they develop and the body painting, babassu coconut straw beds, and other artifacts they produce are also artistic and aesthetic objects that represent their story. Therefore, they are not dissociated from Brazilian art and culture.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The Apinayé are a Brazilian indigenous ethnic group that live in a transition zone between the Cerrado and the Amazon. This study primarily aims to understand the meaning that art holds for Apinayé indigenous students at a Brazilian Indigenous School. Research suggests that the art discipline at school can help students to understand that the crafts they develop, such as body painting, necklaces, babassu coconuts, and the straw beds they build, are also artistic and aesthetic objects that represent the history of their people. Therefore, they are not dissociated from Brazilian art and culture. However, for this process to occur, we understand that it is interesting for the discipline of art to be both valued in Brazilian education and considered of fundamental importance in the teaching and learning processes of so many children, young, and adult students.

The Apinayé are a Brazilian indigenous ethnic group that live in a transition zone between the Cerrado and the Amazon. This study primarily aims to understand the meaning that art holds for Apinayé indigenous students at a Brazilian Indigenous School. Research suggests that the art discipline at school can help students to understand that the crafts they develop, such as body painting, necklaces, babassu coconuts, and the straw beds they build, are also artistic and aesthetic objects that represent the history of their people. Therefore, they are not dissociated from Brazilian art and culture. However, for this process to occur, we understand that it is interesting for the discipline of art to be both valued in Brazilian education and considered of fundamental importance in the teaching and learning processes of so many children, young, and adult students.

1. Introduction

The first contact between the Apinayé people and mainstream society occurred at the end of the 18th century when the pioneers.Footnote1 sailed along the Tocantins River in order to capture slaves (Albuquerque, Citation2008). According to the author, much like other Brazilian indigenous communities, the Apinayé have faced problems regarding their land being invaded by farmers and land grabbers,Footnote2 among others, causing armed conflicts in many of these indigenous communities. The extent of this trend can be seen in the recent massacres that have occurred in rural areas of Brazil. In 2019, the number of indigenous deaths in the country increased by 11% compared to 2018 (Passos, Citation2020), with 87.5% of the indigenous people killed in conflicts in the countryside being indigenous leaders. According to this author, these deaths have mostly related to land disputes.

In this regard, it is important to make an important observation: In February 2020, the Brazilian government sent a controversial project to the National Congress which, if approved, would allow the commercial exploitation of mineral resources in indigenous lands (Guardian, Citation2020). According to the government, the presence of indigenous people occupying many lands has made it difficult to explore these territories in search of gold and diamonds (Guardian, Citation2020). We have no doubt that a project like this concerns indigenous leaders and environmentalists, as this mineral exploration would accelerate the destruction of the Amazon and increase the number of violent conflicts brought against indigenous people. Consequently, this exploitation would encourage the use of pesticides by companies that support this exploitation of mineral resources, seriously affecting the health of indigenous peoples and further destroying the environment (Oliveira & Araújo, Citation2020).

Any debate in Brazil involving indigenous people leads us to mention the land disputes and violence they have suffered in recent years. This has become especially visible internationally since the 2018 presidential election (Guardian, Citation2020; Oliveira & Araújo, Citation2020; Passos, Citation2020). In line with these events is the debate about the mandatory study of art in high school in Brazil: arts education has been diminished in Brazilian education due to the High School Reform Law n. 13.415 (Brasil, Citation2017a), which removes the mandatory arts curriculum in high school, considering it “studies and practices” rather than a curricular subject. Add to this the publication of the document of the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communication no. 1.122 (Brasil, Citation2020) which reduces the areas of arts, humanities, and social sciences to “basic sciences,” stating that they are no longer priorities in the current government because they do not contribute to the economic and social development of the country. This has generated much controversy in the scientific and academic communities of Brazil.

We understand that talking about indigenous people in the country is not disconnected from their reality and the problems they face in maintaining their culture and tradition (in which art is present in their daily and school life). As a characteristic of ethnographic research, contextualizing the object of study and its participants from the reality they live situates the reader for the debate about the ethnographic interpretations produced. Considering the journal’s international readers, it is important to inform them about this.

This research forms part of a broader study.Footnote3 developed at the Federal University of Tocantins (UFT), campus of Tocantinópolis, Brazil, within the scope of the Research Group on Visual Arts and Education (GPAVE), registered with the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). Its main objective is to understand the meaning of art for indigenous elementary school students at a Brazilian Indigenous School located in the state of Tocantins, which is in the northern region of the country.

UFT was the first university in Brazil to establish quotas for indigenous students in their admission processes, a practice that began in 2004. Thus, the Federal University of Tocantins has a responsibility and a commitment to raising the schooling level of the population of the State of Tocantins “by offering contextualized and inclusive education. In this way, the university has developed actions aimed at indigenous education, rural education and youth and adults” (Course Pedagogical Project, Citation2019, p. 09).

By virtue of having a significant heterogeneity in its population, which highlights the large proportion of indigenous peoples and the state’s rural population, Tocantins is characterized by being multicultural. This has presented the Federal University of Tocantins with the challenge of proposing and developing educational practices that promote the development of its population. It is important to highlight that the different territorialities of Tocantins were occupied by indigenous people and Afro-descendants, among other groups. To gain an idea of this diversity, Tocantinópolis has an indigenous population of more than 3,000, most of whom are of Apinayé ethnicity. This population is distributed across several villages located in the rural region of that municipality.

The primary motivation behind this research was the contact between the researchers and Apinayé indigenous students from the Rural Education course with degrees in Arts and Music at the Federal University of Tocantins, Brazil, as well as through experiences carried out in academic activities relating to the same course with these students. During some classes, the indigenous people verbally shared (many speak the Portuguese language) the history and knowledge of their communities (located in the rural region of Tocantinópolis) with the other students and teachers (non-indigenous) of the university, both during the curricular disciplines of this course.Footnote4 and through events and academic activities held at this institution.

These experiences, as well as our contact with these indigenous people, motivated us to improve our understanding of both their culture and the art they produce. This was partly due to the fact that a significant number of indigenous students were taking this course at the university, as well as that this course concerns arts and music (that is, the course trains teachers to work in rural schools in the discipline of art).

In this sense, researching this topic is important, because, in studies conducted by one of the authors of this article, we found that almost none of schools located in this region have teachers trained in the arts (visual arts, theater, dance, or music) to work in this discipline, and the teachers were instead trained in other areas, such as pedagogy, linguistics, mathematics, physical education, etc. (Araújo et al., Citation2019). In a similar study, Miranda and Cover (Citation2016) mention that the choice of the arts for the UFT (Rural Education) course is justified by the fact that it solves the problem regarding the lack of art teachers in schools located in the north of the State of Tocantins. It was this information, combined with our experiences, that created an interest in developing this research.

In addition, considering the scarcity of studies in the academic literature on pedagogical practices in arts with indigenous people developed in the discipline of art, at the school level, this research hopes to contribute to the broadening of the understanding of other educational contexts that address this theme, since focusing on art education (which addresses the main areas of arts: visual arts, theater, dance, and music), may be relevant when thinking about public policies aimed at training teachers in arts in this context.

It is essential to point out that as a theoretical/analytical framework, this research was based on educational research regarding the education of indigenous peoples, art/education and ethnography in Brazilian and international literature, which helped in the development of interpretations regarding the object of study listed in this research.

By developing an ethnographic study that is placed in the context of the arts and education, we aim to complement research that addresses this theme in different international contexts, contributing more broadly to our understanding of the importance and meaning of indigenous art produced in an ethnic group. In this sense, this study will contribute toward the production of knowledge by providing valuable information regarding the culture and knowledge produced by an indigenous ethnicity in terms of their art.

2. Materials and methods

We used an ethnographic research methodology, “a research approach that involves the construction of knowledge through access and staying in an environment for a sufficient time … ” (Franco, Citation2018, p. 894). This methodology allowed us to study the behaviors, beliefs, customs, and habits of the Apinayé ethnic group at a Brazilian public school called Tekator Indigenous State School, which is located in Mariazinha village, a rural region of the city of Tocantinópolis, state of Tocantins, Brazil.

In this sense, we seek to describe and analyze the data from the method proposed by Geertz (Citation2008) called Thick Description, which refers to an observation method that aims to provide the understanding of the significant structures that are part of the observed action in which it is apprehended and presented. In other words, it is necessary for the researcher to make an intellectual effort in the analysis and interpretation of the collected data, because “to practice ethnography is to establish relationships, select informants, transcribe texts, raise genealogies, map fields, keep a diary … ” (Geertz, Citation2008, p. 4).

Thick Description does not aim to diagnose a particular culture, but instead to broaden the universe of human discourse (Geertz, Citation2008); for example, in this study, by giving indigenous people a voice in what art means to them, and how learning in the arts is developed in the arts classes of an indigenous school.

In this sense, our role as researchers was, from the immersion in a new culture, to observe and understand the social actions built in the indigenous reality. This immersion is necessary to effect Thick Description and observation as methods of the ethnographic approach (Geertz, Citation2008).

The research participants are indigenous students from two classes at this school (each class contained 15 indigenous people); namely, those in fifth grade and ninth grade of elementary school. Regarding the choice of these classes, they were chosen as they were the only ones available to voluntarily participate in this study. As a methodological strategy, we used a case study, which allowed us to use “observations, documents, field notes and contact with the study participants” to study and understand the actions of the participants (André, Citation1984, p. 52). In other words, the case study allowed us to address descriptive and qualitative aspects of the studied reality by analyzing the data of this reality through these methodological instruments, as well as through interpretations of the data generated in the events that occurred in the field of investigation (Yin, Citation2005).

To generate the data used by this research, we conducted direct observation (Lakatos & Marconi, Citation1991) of ten art classes in the fifth year class, with each 50-minute class held once a week (i.e., the art classes took place only once a week, the subject with the least workload in the school curriculum). This helped us to analyze and observe the events that occurred in the classroom. It is important to clarify to readers that the teacher of the art discipline authorized the observation of a maximum of ten art classes.

To carry out the methodology, we used open questionnaires with ten indigenous students from the ninth year of the same school. These questionnaires were applied during the field research and included 13 questions about art and culture. It is important to highlight that we selected the most assiduous of the 15 students enrolled in this class, interviewing those who volunteered to participate in the study. It is essential to emphasize that we used the questionnaires to complement data collection, which is important to expand the field of description and explanation of the phenomenon studied and, consequently, interpret the actions observed.

Therefore, the data were collected from these two methodological instruments: open questionnaires with the indigenous and observation of art classes, from an ethnographic perspective. Regarding the amount of data collected, we were able to collect 15 questionnaires answered and ten classes observed and transcribed in the field journal. These instruments were the forms of data used in the survey. In the form of data analysis, the study followed the ethnographic interpretive perspective, since this analysis interprets the flow of social discourse (Geertz, Citation2008).

We would like to point out that the images used in this research have the function of illustrating, in a conscious and ethical way, the culture and the indigenous knowledge, being relevant in ethnographic research, as Russell (Citation2007) points out. For the author, the images make it possible to broaden the interpretations of the data collected in the research, since they are extensively used in qualitative research. Specifically, in this study, the images help to understand the arts and pedagogical practices developed with the Brazilian Apinayé Indians. More than expressing feelings and identities, the images show the drawings and paintings produced by the indigenous students, revealing a culture and knowledge that would perhaps otherwise remain unexplored or unknown. Similarly, Geertz (Citation2008) argues that the images contribute to a better understanding of the cultural and symbolic dimensions of social action.

3. Research participants: who are the Apinayé Indians?

The Apinayé.Footnote5 are an ethnic group that inhabit 24 villages located in the extreme north of the state of Tocantins, Brazil, in a transition zone between the Cerrado and the Amazon (Albuquerque, Citation2012). As its territory is located between the banks of the Tocantins River and the Baixa Araguaia, there are no official records that its ancestral lands were ever inhabited by other groups.

According to Almeida (Citation2012), and based on the demarcation that took place in 1985, the area occupied by the indigenous people in Tocantinópolis spans 141.904 hectares. The author points out that before these demarcations, the indigenous people were limited to only two villages: São José and Mariazinha. Subsequently, the demarcations expanded to form 42 new villages, which gave them greater control over their lands and allowed them to hunt, fish, and plant crops.

According to Almeida (Citation2012), the São José and Mariazinha villages are the most important of this ethnic group, as well as the most inhabited. For this author, the ethnic group can be divided into approximately 25 villages. They comprise indigenous people who still survive by means of fishing, harvesting rice, beans, and cassava, and local commerce, in addition to the retirement of older people and some federal government programs such as the Bolsa Família program.Footnote6

The Apinayé are bilingual (mother tongue and Portuguese). Their mother tongue is the first language acquired by children within the family domain. The families themselves are large and, in most cases, up to six families live in one house, starting from the first generation to the fourth generation (Albuquerque, Citation2012). According to the same author, the first contact of the Apinayé people with the non-indigenous (kupen), a term used by them to designate non-indigenous people or “white men,” took place during the 17th century in a place called Villa Real.

The indigenous people survived off fishing, hunting, collecting wild vegetables, and using the collection of babassu coconut straw to cover their houses, which are built mostly in circular shapes. They also produce household objects and plant various vegetables to sustain their livelihoods. In addition, Luciano (Citation2006) points out that each indigenous people has a way of planning their social, political, and economic relations, based on the family of the patriarch or matriarch.

The customs of dividing the tasks of women and men in the villages are evident: women are required to collect firewood, fruit, and make handicrafts (), in addition to taking care of the house and children; men’s tasks are limited to working in the forest, hunting, and fishing.

4. Research site: tekator indigenous state school

The Mariazinha village is located 20 kilometers from the city of Tocantinópolis, in the northern region of the State of Tocantins. According to the last census of the IBGE (Citation2010)), the village contains 257 indigenous people. For Almeida (Citation2012), Mariazinha is the closest village to the Tocantins River, and its population is mixed. There are few Indians who are of another ethnicity (krikati), and also few kupen people (that is, “white men”). During the development of this research, we had the opportunity to participate in some cultural events in these villages. These included the log race, during which we observed a considerable number of Indians who are married to kupens (Araújo & Santos, Citation2020).

Regarding language, the Apinayé indigenous people of the Mariazinha village speak both Portuguese and their mother tongue. They are influenced in this regard by the union of their parents, as some of them are married to kupens. It is also important to note that some indigenous people also speak the Portuguese language as a result of their contact with the school. According to Albuquerque (Citation2008) and Almeida (Citation2012, p. 38), “this situation contributes to the weakening of the Apinayé language within the family.” However, “the Apinayé are aware of their ethnic position and are aware of the importance that is currently attached to the struggle of the indigenous people in terms of maintaining their linguistic and cultural identities” (Almeida, Citation2012, p. 39).

From a similar perspective, Tsuwaté and Leão (Citation2017, p. 17) state that “the mother tongue … is the first language, followed by Portuguese, spoken primarily on occasions that are in contact with the non-indigenous. Children begin to speak Portuguese at school, between six and seven years of age.” In other words, this process happens when the indigenous people have their first contact with the school, as this is where the Portuguese language is taught.

Regarding schooling, the Mariazinha village features the Tekator Indigenous State School. According to Almeida (Citation2012), the school started its activities in 1960. Currently, the school offers basic education (early childhood education, elementary school, high school, and adult education) and employs 28 people, among them the (indigenous) director, general secretary, pedagogical coordinator, school support coordinator, administrative support assistant, school counselor, and 13 teachers (seven of whom are indigenous), plus cleaning, lunch box workers, and watchmen (Course Pedagogical Project, Citation2017).

In 2014, the school served 299 students. By 2018, this had expanded to 312 students, according to verbal information obtained from the school principal. The students are all indigenous, and the school is open in the morning, afternoon, and evening. However, the school does not have a library. In an attempt to remedy this problem, an empty room is used to store books and other bibliographic materials. There are also no sports courts, so a space outside the school in front of the indigenous peoples’ houses is used for sports activities. These consist primarily of football, while a net is used for indigenous girls to play volleyball.

It is important to highlight that the school features indigenous teachers who work on literacy from the first to the fifth year of the first phase of elementary education, as well as with specific subjects, such as indigenous language, art, indigenous diversities, and indigenous knowledge. From the sixth year of elementary school to the third year of high school, there are some non-indigenous teachers who work with the other disciplines, including Portuguese, mathematics, and science. The school’s painting is based on Apinayé culture, with a predominance of red, white, and black colors, aspects that can be seen in .

In this research, we developed the following categories of data analysis, which were extracted from the questionnaires assigned to indigenous students and from observations of art classes conducted in the field research, from the ethnographic analyses and interpretations made:

a) Pedagogical practices in art teaching with Brazilian Apinayé indigenous people.

b) The thoughts and opinions of the Apinayé indigenous people concerning art.

In the elaboration of the questions and the observations of the art classes, we considered the objectives and the central question of this research. Taking the length of the article into consideration, this study presents the analyses of only some of the observed art classes, as well as a sample of the 13 questions answered by the indigenous people, since these statements refer to the reality in which they live and work. However, this did not limit the analysis of the data, since these analyses dialogue empirically and theoretically with the other classes observed and the results of their questionnaires in the developed research.

5. Indigenous peoples and Brazilian education: a debate under construction

According to Muniz and Albuquerque (Citation2017) and Albuquerque (Citation2012), Brazilian Indians started to gain greater visibility in the late 1980s following the creation of the 1988 Federal Constitution, and subsequently in the 1990s with the introduction of the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education in 1996 (Brasil, Citation2013a), the National Reference for Indigenous Education (Brasil, Citation1998), and the Curriculum Guidelines for Basic Indigenous Education Brasil (Citation2013b). However, even with education playing a fundamental role in this process, their rights were recognized primarily through the creation of the National Foundation of the Indian—FUNAI in 1967.

The official indigenous organ of the Brazilian State is FUNAI. Created by Law no. 5.371, of 5 December 1967 year, linked to the Ministry of Justice, it is the coordinator and main executor of the Federal Government’s indigenous policy. Its institutional mission is to protect and promote the rights of indigenous peoples in Brazil. (Fundação Nacional do Índio - FUNAI, Citation2018).

The quote above is clear: this agency was responsible, among other functions, for coordinating indigenous education, as well as introducing the obligation of having bilingual education in their territories. This was highlighted by the Law of Guidelines and Bases of Brazilian Education (LDB) no. 9.394/1996, in article 32, which states that in elementary education, teaching should be taught in Portuguese, but that the teaching of the mother tongue will also be ensured in the learning process (Brasil, Citation2013a).

It is necessary to clarify that it was through FUNAI that indigenous people first began to exercise the functions of teachers in their villages’ schools. This was coordinated through the Ministry of Education (MEC) in partnership with the Education Departments of the states and municipalities, which are responsible for indigenous education in schools located in villages in different Brazilian regions (Câncio & Araújo, Citation2016).

According to the latest Census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, Citation2010) there are 896,900 indigenous people in Brazil, 36.2% of whom are concentrated in urban areas (compared to 63.8% in rural areas). According to this Census, a large number of these people are located in the country’s northern region, with a greater concentration of women in urban areas and men in rural areas. Based on studies by Rocha et al. (Citation2020) and from IBGE, in the State of Tocantins there are eight ethnic groups: Karajá, Xambioá, Javaé, Xerente, Krahô, Krahô Kanela, Avá Canoeiros, and the Apinayé, with the latter located in the region surveyed by us (Tocantinópolis region, far north of that State). It is essential to point out that these ethnicities correspond to approximately 13,171 indigenous people present in the state of Tocantins (Tocantins, Citation2016).

In addition, there are 82 indigenous villages in Tocantins, distributed throughout the state (Muniz & Albuquerque, Citation2017). For the authors, the villages represent the characteristics and skills of each people, drawing attention to the beauty of handicrafts, paintings, and adornments that decorate their bodies in traditional festivals.

This diversity of ethnicities and languages spoken, as highlighted by Carjuzaa and Ruff (Citation2017), is particularly important. Carjuzaa and Ruff reports that before Europeans discovered the Americas, there were about 500 tribal groups speaking indigenous languages in what would later become the United States, which means there has been a significant reduction in the number of indigenous languages spoken. In research conducted by Johnson (Citation2011a), by the end of the 21st century, it is estimated that half of the 7,000 languages in the world will have disappeared, since a portion of these languages refer to languages spoken by grandparents but not by their children or grandchildren. In other words, some languages have not had a sequence in generations (Johnson, Citation2011b). This situation was also confirmed by Rymer (Citation2012), who warned that there is a great possibility of indigenous languages being reduced over the next 30 years.

In a Brazilian context, and in partnership with FUNAI, the Census of the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) identified 505 indigenous lands which represent 12.5% of the country’s territory. The Census counted 305 indigenous ethnicities, including Apinayé, and 274 indigenous languages, with a predominance of Tikúna (more than 30,000 people) (Araújo & Santos, Citation2020). Regarding the location of this study, according to official data from Fundação Nacional do Índio—FUNAI (Citation2018), Tocantins has 25,805 km2 of regularized indigenous lands, which corresponds to approximately 9.3% of the territory of this state.

However, when talking about Indigenous Education, it is important not to conclude that they have no education. It is necessary to differentiate Indigenous Education from Indigenous School Education:

Indigenous education is organized in traditional learning processes, which involve knowledge and customs characteristic of each ethnic group. This knowledge learned orally on a daily basis … However, several indigenous ethnic groups have sought school education as a contribution to reducing inequality, affirming rights and achievements, in addition to promoting intercultural dialogue between different social agents … school education complements traditional knowledge and guarantees access to non-indigenous school codes … (Sobrinho et al., Citation2017, pp. 59-60).

This understanding of Indigenous Education and Indigenous School Education is particularly important, as it is essential that schools located in this environment deliver an education that considers the specificities of indigenous cultures in the educational process (Araújo & Santos, Citation2020).

In this discussion, it is important to note that in 2003, the Ministry of Education (MEC) created Law no. 10.639/2003, which establishes the mandatory nature of indigenous themes in Brazilian Basic Education. This was important for society in terms of increasing their understanding of the roles that indigenous people play in both the national culture and the production of knowledge. Consequently, the construction of these schools within indigenous communities was extremely significant for the education of indigenous peoples, as it made it possible to receive an education without having to leave their villages (Araújo & Santos, Citation2020).

As these above studies show, the recognition of Indigenous School Education was necessary for the construction of school units within the villages, providing a formal education without forcing villagers to leave their social and cultural milieus. However, this education is still based on a rural perspective, as these villages are mostly located in rural areas (Feitosa & Vizolli, Citation2019).

Similarly, Almeida (Citation2012, p. 47) asserts, “at LDB no. 9394/96, indigenous school education must be treated differently from other schools in the Brazilian education system, signaling the practice of bilingualism and interculturality.” In the context of this research, it is curious to note that in January 2018, the Tekator Indigenous State School was awarded the Multifunctional Resource Room (Multifunctional Room), a demand imposed by the Mariazinha village community itself, to serve indigenous students with disabilities (Araújo & Santos, Citation2020).

Consequently, after the implementation of indigenous education in their cultural territories, it was necessary to create a federal body that would defend the interests and needs of indigenous people while also protecting their rights. This federal body is FUNAI.

In this sense, we understand that addressing these indigenous issues in educational literature is important because indigenous people bring many significant contributions to a nation’s culture and art. Therefore, we believe it is necessary to emphasize what the scientific literature has been saying about indigenous people and how we could relate these reflections to art education, contextualizing this research.

5.1. Indigenous Brazilians without art classes? Removal of the discipline of art in the Brazilian high school curriculum

Rather than reviewing the history of art education in Brazil and its relationship with indigenous school education, this article instead proposes some current reflections in this area and enunciates the theoretical bases on which we analyze the central research question. In this sense, we consider it important to situate art/education as a vast theoretical-reflective field that has consolidated itself as a relevant research object in academic studies and can dialogue with different individuals and research contexts, such as with indigenous people of Brazilian ethnicity.

To situate the reader in this discussion, in one of the surveys conducted by one of the authors of this article, we show that art has been taught in Brazilian schools for almost 50 years (Brasil, Citation1971). However, this came about as a result of a long historical process that is considered subsidiary knowledge, which is not important for the curriculum. Rather, it is sufficient to compare its total workload with the other curricular disciplines, and with teachers who lack training in the arts. In the researched indigenous school itself, this discipline is offered only once a week, with a 50-minute workload per class and with a teacher (even though he is indigenous) who does not have a degree in the arts.

In addition, due to the fact that the discipline of art operates under Brazilian law via the approval of the High School Reform (Brasil, Citation2017a), which excludes High School art and the non-democratic construction of the Common Curriculum National Base (BNCC) (Brasil, Citation2017b), we argue that this area deserves to be valued as an independent area of knowledge that should be inserted in the school curricula of Basic Education in each of its respective areas (visual arts, theater, dance, and music). In the middle of the 21st century, and after important achievements.Footnote7 about art in Brazilian education, it is inconceivable that art teachers and researchers in this area still have to face such a worrying situation, which makes it impossible to develop this form of teaching in school curricula in either urban or rural areas.

In the cycle under discussion, the art educator Barbosa (Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c)) raises an argument that broadens this debate: the withdrawal of the discipline of art by the Reform of High School has taken 49 years, dating back to the start of the education project in Brazil. This also decreases the formation of important skills in other disciplines, as evidenced by research.Footnote8 confirming that the study of drawing improves the quality of a student’s writing. In addition, studying and analyzing artistic images improve reasoning regarding scientific images and the ability to read, as well as aiding in the interpretation of texts.

In this Reform, it was not understood whether the discipline of art is mandatory, nor how it would be worked into the curriculum of Brazilian schools; that is, in the words of Barbosa (Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c), nobody knows what will happen with this area in Basic Education in Brazil. This implies that art can increasingly lose its importance in the curriculum, as it can be taught by anyone who says they are an artist, for example, so long as the Ministry of Education (MEC) approves. As we consider both the audience of this journal and the need to expand the discussion about the importance of art not only in urban schools but also in indigenous schools, it is relevant to share this information with its international readers.

In this sense, we understand that besides being necessary and important in the school curriculum, art is also culture, because it is knowledge, and it is through the arts that one can understand and know the cultural diversity among different peoples, because “we cannot understand the culture of a country without knowing its art. Without knowing the arts of a society, we can only have partial knowledge of its culture” (Barbosa, Citation1998, p. 16). In other words: through Apinayé indigenous art, it is possible to understand and know a little more about its tradition and, consequently, Brazilian culture.

In fact, culture is essential for learning in art, because it provides the indigenous with rich experiences of knowing the cultural diversity among peoples and presenting their culture from art, which reveals not only the knowledge of their ancestors, but an enormous cultural plurality indigenous to Brazil. Therefore, we understand in this research that art and culture are not dissociated from human knowledge.

6. Pedagogical practices in art teaching with Apinayé indigenous people

It is important to draw attention, however, to the fact that we focus the analysis of the data according to our perspective as researchers. Although we have used ethnography as a methodological strategy, we believe it is important to highlight the actions developed and analyzed from the researchers’ perspectives, as the subjects of this investigation (indigenous students) are very shy and did not socialize with the researchers during the eight months in which we had contact with them in order to collect the data from the village. Therefore, out of respect for their culture and understanding, we chose to adopt this position. In effect, this does not mean that the analyses performed were done from a dominant perspective.

The name Tekator refers to an indigenous person called Tekator (Albuquerque, Citation2012). This information was confirmed during our immersion in the village; according to one of the indigenous people we had contact with during the ethnographic research, the name comes from an indigenous person whose name was Tekator who had an Apinayé mother and a Krikati father. Before his mother’s death, Tekator lived in the Apinayé ethnic group; after his mother’s death, he returned with his father to the state of Maranhão to live with the Krikati ethnic group. However, he did not get used to this ethnicity and later returned to Tocantins to live with some relatives, living for a long time in the Botica village, returning to his ethnicity of Apinayé origin.

In this village, he met his wife, and after a few years Tekator gathered his family and traveled to a new place to live. After a long time, Tekator returned to the Botica village in order to convince the indigenous people to move to his new village. The village chief accepted the proposal to live in his village, he talked to the people of the village and it was decided to get together to form only one family and live in this new village. After agreeing to this proposal, the entire population accompanied Tekator and immediately built their houses. Soon after everyone was present, they decided to name the village Mariazinha, whose name came from Tekator’s mother who was called Maria. And so began their new village.

However, their farm services were all community-based; decisions within the village were made collectively. Tekator preserved for his villagers their customs such as paintings (regardless of the occasion, everyone had to paint themselves). Tekator gave names and meanings to each of them.

During our the research time in the village Mariazinha, we identified that several teachers live in the city of Tocantinópolis, and go by bus to work in the village practically every day. When we arrived in the village we met the director of the school who is indigenous and talked to him about our research and how it would happen in his school. He received us very well and welcomed us. Then we took his signature on the research authorization form and left with him to talk to the pedagogical advisor who would pass on some explanation about the art teachers and the outline of the Pedagogical Political Project of the village school (PPP) that is in progress. We talked a lot, he showed us the whole school and also welcomed us.

When collecting the data from the school we returned on the same bus arriving at a certain place we got off and walked another 3 km on the road without being paved along with some teachers who live in town to catch another bus to the city. But it is worth noting that on that day we only returned at that time because all teachers were closing the semester, so the indigenous students were dismissed earlier. So the buses returned to the city earlier, but when they are in normal operation, the teachers who work for the afternoon and night only leave at 10:30 pm, and the others who stay until 5:30 pm stay until a certain and walk these 3 km to reach a town called Ribeirão Grande, to try to get there in time to catch the bus from the city hall. However, when they happen to miss these buses they choose to get a ride.

In some observed art classes with the fifth grade class at the Tekator Indigenous School, which took place throughout 2018, the subject’s teacher worked on theoretical and practical contents of visual arts, focusing on the study of colors and their meanings, the types of paintings, both from the past and the present in the researched indigenous community, as well as drawings about the Apinayé culture. This work was conducted in both their mother tongue and the Portuguese language.

It is interesting to note that the classroom in which these classes took place was small, with the 17 tables and chairs representing the total number of students who attended. The vast majority of these students were male. Further, we found that these spaces were decorated with drawings and paintings produced by the students themselves, with representations of different elements from nature.

6.1. The use of the Apinayé indigenous language in class

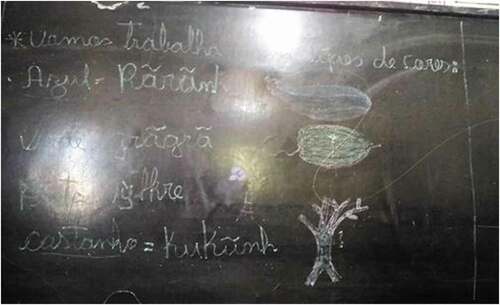

In the class on colors, the teacher (who was indigenous) wrote an activity on the board that represented a selection of colors, such as blue, green, and black. Using chalk, he wrote the names of each color on the board in Portuguese and subsequently asked the indigenous students which name the color referred to in their mother tongue. Few managed to respond. Later, he wrote a certain color on the board in Portuguese and subsequently showed the image through a colored pencil, referring to that color written in Portuguese. In this instance, most students answered the teacher’s question correctly. The teacher then said the color in their indigenous language. At that moment, all of the students came to know the corresponding color that the teacher was presenting to them.

In these observations, we identified that among fifth year indigenous students, the Portuguese language is still rarely spoken. This is why some students did not know how to answer when the teacher wrote the color on the board in the Portuguese language. This procedure also occurred with the other colors. In another moment, the teacher asked each student to draw in front of the color something that referred to a drawing of their culture, as can be seen in .

In this image, it is possible to observe the name of the color in Portuguese (left side of the blackboard) and how to write that color in the students’ mother tongue (middle of the blackboard). For example: blue = rãrãnh. In front of the translation of their respective colors are the drawings designed to represent each color, such as blue being represented by a jenipapo, green by a cashew, black by a coconut, and brown represented by the branch of a tree.

In another observed art class, the indigenous teacher worked on paintings that characterize the Apinayé culture. To begin, the teacher spoke about aspects of the paintings used by people in this culture. For example, women only use “wamnhêmê,” which carries straight and rounded lines. This is because each indigenous woman chooses which painting to use.

On the other hand, the paintings used by men are called “katân,” which have straight and triangular shapes. However, there is only one painting for men, because the only thing that can change and form different drawings is the position of their shapes in the painting, which makes it possible to create other drawings even while the triangular shape remains the same in each.

After this brief explanation, the teacher told the students about the paints used to make these paintings, which are based mainly on jenipapo (which makes all the tracing of both female and male paintings), and urucu (the red color of which is used for filling in the lines made by jenipapo). The teacher also said that these paintings are used mainly in ceremonies or rituals of the Apinayé community, allowing them to express feelings of joy or sadness.

The teacher then asked each student to produce a drawing about what was explained in class but related to their culture. In this process, the students could choose between female and male paintings to make as an activity in the art class. shows some drawings produced by indigenous students during that moment:

The figure above depicts some drawings of faces seen in profile, as well as human figures in different positions. However, we noticed that some students also decided to draw the shapes of their own houses in the village. It is important to note that all of the drawings were made on A4 sheets of paper, the majority with pens and pencils. In some of the drawings, they wrote the name “panhi” in their mother tongue, which means Indian in Portuguese. After finishing their drawings, the teacher collected each one to exhibit them on the classroom wall, allowing everyone to observe the activity performed.

Most Apinayé drawings and paintings inspire the production of other drawings, as they represent forms of nature and the indigenous people themselves. This leads us to affirm that the elements present in these productions reveal Apinayé culture and daily life.

We observed that the drawings obey the spatial limitation of the paper and are organized in a composition formed by faces, bodies, and elements of nature, such as trees, indigenous houses, animals, and others that belong to their culture. This analysis is important, as it demonstrates the aesthetic understanding of the Apinayé Indians. In this sense, Portes (Citation2015) points out that indigenous productions elaborated from their experiences and culture reveal not only the authorship of works of art but also the values, meanings, and senses that the indigenous people have built and which they struggle to preserve and maintain within the Apinayé community.

However, according to the teacher’s report, all activities related to the drawings made in the art classes are exposed in the classroom, as he believes that this helps the indigenous people to better appreciate the value of their artistic production. In our understanding, this practice is a way of working with artistic exposure based on the works created by students, positioning them as authors of the works created by themselves.

6.2. The learning attitude of Apinayé students

In order to proceed with the analyses, in another class, the teacher sought to expand a little more on the understanding of Apinayé culture by exposing drawings he had produced himself. At that moment, he informed the students that he himself had assembled the material as follows: he selected the drawing from the internet before painting and pasting it on a piece of paper. Subsequently, he covered the drawing with a piece of transparent plastic and elaborated the name of each figure on paper, cutting it out later. That day, he brought this material to the class with the following figures: the kuati, the jaguar, the paca, the Indian, the alligator, the gourd, the tree, the fish, the arrow, the design of his community, and the anteater, which can best be viewed in .

The teacher, when placing the drawings on the board, asked each student to get up from their chair, walk in front of one of these drawings, and write their name on them. It is important to remember that the names of the figure, as shown in the image above, were all in their mother tongue. The teacher said that this activity aimed to work the Apinayé language to strengthen the knowledge of their community.

We found that most of the students had difficulties in doing some drawing work. Because it is a discipline that combines theory and practice, when faced with works of art that require a certain skill to produce, as is the case with drawing, the students feel insecure in their performance of it, as it implies greater attention from the teacher of the art discipline.

It is important to emphasize that the artistic discipline can provide the indigenous student with a way to develop their aesthetic education, expand their cultural knowledge, leading them to master different artistic and conceptual techniques, build knowledge from contact, and access different artistic manifestations such as drawing, painting, photography, dance, music, theater, and computer art, among many others, including theories of art history.

In other words, creative development is related, among other factors, to the knowledge in the art that the individual has, that is, in his aesthetic experience. This became clear in the drawings of the indigenous people observed, even though they presented some difficulties in finishing them. However, art teaching at school needs to promote situations of this experience, by allowing students opportunities to build knowledge with more critical sense, producing relevant discussions about the visuality of several productions around them (Pillar, Citation2013). In fact, if the indigenous have contact and continuous access to the artistic manifestations of their locality and other peoples, either through visits to museums, research in books and on the internet, of the artistic objects produced by their village, or even in art classes, they can significantly expand their fields of aesthetic and artistic knowledge, and consequently, their awareness of reality.

… the interest in studying or appreciating art arises from the relationship with artistic language … the art educator can research around the school, in the neighborhood where he works, make an attentive walk and perceive the images and artistic manifestations that emerge in the place and elaborate an artistic inventory - culture of the region. Identifying the manifestations that contain arts can be a collective work of the students, guided by the teacher (Arslan & Iavelberg, Citation2009, pp. 41-42).

The above quotation is important because it makes clear in this discussion that the arts are directly related to the aesthetic and artistic aspects of knowledge, which leads to the understanding that education in art is not only knowing the life, work, and technical procedures used by the artist, but also understanding and building knowledge in art from the experiences of a people—their culture and traditions.

In this sense, recognizing creative teaching practices and developing inclusive thinking is fundamental for a successful teaching and learning process (Arrazola & Bozalongo, Citation2014). It is in this perspective that we highlight the work developed by the art teacher with the indigenous people; even though the school lacked didactic materials of arts, the teacher sought to work with the indigenous peoples’ drawing and painting that would help them to develop their motor skills and to know a little more about the culture not only of their people, but of their country.

In this sense, based on these analyses of art classes at an indigenous school, we identified some points that deserve to be highlighted: a) the indigenous people of the researched class are very shy, mainly in terms of answering the questions asked by the teacher during art classes. However, in no instances did this hinder them in the development of the activities proposed in this discipline; b) the indigenous teacher works with the students’ reality, emphasizing the Apinayé culture as the main theme of his classes. All of the activities they worked on during the observations aimed to increase the knowledge of the indigenous student, which is important for advancing his teaching and learning process; c) we also observed that not all indigenous students participate in the classes (however, most do). In some of our observations, we asked if they were shy because of our presence, and the teacher replied that they were not, adding that they are like that normally and that it is part of the Apinayé indigenous culture.

Based on this information, we can affirm that Apinayé indigenous art has an important role in the development of the learning of indigenous students who, through contact with this art, can expand their knowledge of the culture of which they are a part. Consequently, it can be said that art has an important role in society, as it is the means by which the individual can communicate with the reality around them, expressing themselves in different ways, which allows us to claim that art changes reality (Araújo, Citation2018a). In this way, this expression of the real carries a load of experiences that the individual has built throughout his life and expressed through art. When conceiving reality and materializing it in the artistic object, an indigenous person transforms it, constructing significant interpretations of their own reality.

7. The thoughts and opinions of the Apinayé indigenous people regarding art

In order to expand the reflections built on the Apinayé indigenous art, as well as to try and answer the problem of this research, we applied open questionnaires to 10 students in the 9th grade class of the researched indigenous school. It is important to clarify that the questions were translated by an Apinayé teacher from the school itself into their language, thus enabling the indigenous people to both understand the questions and answer them. Subsequently, the answers were translated, organized, and analyzed for the purposes of this research.

When asked about the materials used to produce indigenous art, the Apinayé presented the following answers:

Jenipapo, urucu and babassu straw.Footnote9 (EI 01)

Crafts with babassu straw. (EI 02)

Jenipapo and urucu. (EI 03)

Village materials. (EI 04)

Jenipapo and urucu. (EI 05)

Village seeds. (EI 06)

Handicraft made from babassu coconut straw. (EI 07)

Handicraft produced with babassu straw. (EI 08)

Babassu straw. (EI 09)

Village seeds. (EI 10)

Jenipapo and urucu. (EL 11)

In the accounts of the indigenous people, it is evident that the materials they use to produce indigenous art can be summarized as jenipapo, urucu, and babassu straw. Of these, jenipapo is one of the most used. Regarding its meaning, we highlight the following quotation:

… It is originally from Central America and is currently distributed in the tropical regions of several countries in America, Asia and Africa. It is found sub-spontaneously in tropical regions … the plant is of great importance to the Indians, due to its medicinal properties and used to produce their paintings.. (Souza, Citation2007, p. 04)

This fruit is planted and preserved by the indigenous people in the village, as it serves to make their paintings by providing a lasting black color. When applied to the skin, these paints last between 15 and 20 days. For Apinayé natives, genipap is very special and has a great degree of cultural importance. This is because the fruit is extracted from the body painting of the Indians. However, they do not consume it, instead only using it for paintings.

Another product that is used to complement this, with jenipapo representing the color red, is the urucu, which means “ … a plant of the magnoliópsida class, of the malvales order, of the bixaceae family, of the genus bixa and of the species bixa orellana, the seed is monocotyledonous, native to tropical America, which reaches a height of six meters”. (Tsuwaté & Leão, Citation2017, p. 79). Unlike jenipapo, urucu is a less durable ink, which has a red color and is used together with jenipapo to produce body paintings.

It is important to note that the majority of these objects are made up of drawings that represent Apinayé culture, because as they are people who preserve and respect nature, they make objects with drawings that represent their place of origin and life. They also produce other objects, such as handicrafts made of babassu coconut straw in the production of matting and bags. These objects form part of their culture and require knowledge of specific techniques for their creation. This is because within the village, the art teacher has to be an indigenous person, meaning they can share knowledge on the production of these materials in a more appropriate way.

7.1. Art as culture and protest

To advance the conclusions of this article, we asked the Apinayé what art means to them. Here are their testimonials:

Fights and marks. (EI 01)

It means history. (EI 02)

History. (EI 03)

Culture. (EI 04)

It means culture. (EI 05)

It means learning. (EI 06)

It is history. (EI 07)

Art is to resist. (EI 08)

And culture. (EI 09)

It means struggle. (EI 10)

It means culture. (EI 11)

We note in their responses that art represents their life trajectory built in the village, since the drawings and paintings they produced in art classes serve as historical and cultural records of their people. For them, by seeing this culture in artistic forms, the Apinayé culture does not cease to exist, as art is marked by history and passed down from generation to generation. Apinayé culture therefore continues to live through the artistic objects they produce, as highlighted in this research.

It is essential to point out that a significant portion of the students’ testimonies stated that art means to resist, and we believe that this response occurred due to a number of reasons: a) a lack of land for the indigenous people (many indigenous people have lost their land or have been expelled by farmers present in the region, as was mentioned at the beginning of this article); b) some are forced to leave their villages to live in the city; among other reasons. In addition, their reports reveal a rich cultural identity, permeated by meanings and knowledge. This is because it was through this struggle that their knowledge and artistic objects are still present in society and give significance to their history (Cohn, Citation2001).

These testimonies are rich because they reveal that indigenous art is permeated with symbologies, customs, and beliefs. For the Apinayé, art is synonymous with culture. This counters research conducted by Barbosa (Citation2010), who affirmed that there is no way for us to know the culture of other peoples without knowing their art; however, this knowledge can be expanded based on the artistic activities developed in the art classes at the village school itself.

The village is a place where indigenous people live, work, and produce their culture. It was there that they had their first contact with indigenous art, which they learned through their parents. Therefore, when given access to formal education, they already carry with them a cultural and artistic experience taught by their family members. These are worked and socialized experiences within the school. Within these institutions, part of this knowledge is passed on to students through their indigenous teachers, as evidenced by this research.

These testimonies are important because they reveal that the participants see artistic education as something that is present in their social and cultural environment; for example: seeds of village plants to produce natural paints, land to create pots to store food, leaves of trees to build beds to lay, and many other ornaments and objects. They also see artistic education as a form of resistance and culture, for example, when painting their bodies, performing rituals, and having parties. Art is important in their daily lives and naturally has an impact on their school education as another opportunity to expand their knowledge of the world.

7.2. No art subjects in the school curriculum, no learning and knowledge building in art for indigenous people

In the thoughts and opinions expressed by the indigenous people, and reading between their lines, a conception of art is implicit. However, it is also necessary to make an important observation: when talking about art, you immediately think of art that is displayed in galleries or museums around the world. This does not apply to indigenous art, however, because in their culture:

… there is no specific context that defines what is art and what is not; there is no “theory of art” in the strict sense; in other words, among indigenous cultures, there is no “world of art”, because there is no art as a different activity from the production of “useful” objects. Those who understand “indigenous art” as “art”, therefore, are not “them” - it is us. (Nunes, Citation2011, p. 146)

The above quote is revealing: indigenous people do not depend on the canonical concept of what art is in order to produce art, since it is manifested in their dances, paintings, and handicrafts. Thus, the artistic concepts they build come from their life stories and the knowledge built throughout their lives. However, this does not exclude us from expanding our concept of art via contact with the different artistic manifestations of other peoples and cultures in the contents worked in the discipline of art. It is important to expand our aesthetic and cultural understanding, but as long as their culture is respected.

Art significantly develops a student’s intellectual aspects. This is because it can help to improve their performance at school, while also enabling them to better understand the reality into which they are inserted, making them a more creative, critical, and participative individual with an advanced awareness of reality. This is important in expanding their knowledge of the world in terms of both its cultural and aesthetic forms (Barbosa, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2017c).

When reflecting on the findings of this research, it is important to highlight that art accompanies the very development of society. It is manifested by different means, and has in education a relevant method of knowledge sharing through which an indigenous person can develop their skills, learn about the different artistic manifestations around them, expand their cultural knowledge, form concepts, create ideas, interpret reality, and develop an aesthetic sensitivity, because “as an essentially human creation, art is produced at a certain time, context, culture and society”. (Araújo & Oliveira, Citation2015, p. 686); therefore, the social and cultural context in which art is produced and analyzed must always be considered.

For this reason, we advocated that to remove the discipline of art from the curriculum of Brazilian schools is to stop working with the aesthetic and cultural formation of indigenous people, as well as to limit the representation of the identity of a people. In addition, without contact with the arts at school, students may become less critical, participatory, and less aware of reality, since they would be limited to building knowledge in the arts from their indigenous reality (Barbosa, Citation1998).

8. Conclusions

The research conducted in this study showed that the arts produced by the indigenous people refer, mostly, to the body paintings and cultural artifacts they make, such as necklaces made of beads, coufo, and babassu coconuts, among others. We also found that they themselves teach the techniques of how other arts are made, rather than just having the teacher of the discipline of art explain their meanings and teach the younger ones which of these arts are most used by the Apinayé. This ensures that their knowledge of their cultural and artistic heritage is passed on from generation to generation.

The data generated and analyzed in this research enabled us to understand that the Apinayé characterize their culture as something important for life. In other words, art means the essence of a people that struggles to keep alive its identity and the knowledge it has produced over time. Although many students reported that they like art, they also made it clear that it represents not only their reality, but the history, struggle, and resistance of their people. In addition, the Apinayé continue to maintain traditional rituals and festivals as a way of relating to their ancestors. In other words, art and culture have the same meaning for the indigenous people, as they do not dissociate themselves from their lives and tradition. Moreover, it was evident in their statements that art for them is a form of protest.

Research suggests that the art discipline at school can help students to understand that the crafts they develop, such as body painting, necklaces, babassu coconuts, and the straw beds they build, are also artistic and aesthetic objects that represent the history of their people. Therefore, they are not dissociated from Brazilian art and culture. However, for this process to occur, we understand that it is interesting for the discipline of art to be both valued in Brazilian education and considered of fundamental importance in the teaching and learning processes of so many children, young, and adult students. This will allow schools to offer this discipline not only in urban areas but also in indigenous regions, enabling them to offer better working conditions for teachers and students; for example, by providing teaching materials that are appropriate for indigenous cultures and offering art labs for practical classes.

When observing how indigenous arts are produced, we identified that the teacher of the discipline of art showed that the main materials used for the production of body paintings are based on annatto and genipap, which are materials typical of their culture and easily found in the village. In terms of handicrafts, meanwhile, indigenous people use babassu coconut straw and the seeds of foods found in the community to produce their accessories.

It is important that the Apinayé indigenous people have their socio-cultural and educational specificities considered in indigenous schools located in rural areas, rather than being forced to learn about this culture from a mainstream perspective. In this way, working with contents disconnected from the indigenous reality may contribute little to the development of a student’s learning, as they will make few inferences from reality and will not show any interest in the activities to be conducted. Therefore, the role of the teacher during pedagogical practice is important in creating a dialogue within the context of the indigenous Apinayé.

It is important to remember that it is not only in museums that art is learned, but also in schools. Schools allow indigenous people to share their knowledge and culture through cultural objects they produce themselves. Schools provide this important opportunity for indigenous people to assimilate how the learning process in art occurs and consequently make significant interpretations of their own reality.

With this research, we hope that this study will be able to yield other interpretations that dialogue with the ethnographic interpretive perspective, as new social phenomena emerge. This is important to expand the production of knowledge in the area, since there is a lack of research on pedagogical practices in the arts and school indigenous communities in scientific literature.

Fulfilling one of its objectives, this research suggests the elaboration of other studies that focus on the differences and similarities of other international experiences regarding indigenous art. This will help to expand research on this theme, while not exhausting the discussion proposed in this manuscript. In this study, we wanted to show that it is possible to generate valuable discoveries from the methodological procedures implemented, even given the cuts to the data made for the purposes of this article.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Apinayé indigenous people for accepting voluntary participation in this research and the Tekator Indigenous State School for having authorized this study.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gustavo Cunha de Araújo

Gustavo Cunha de Araújo. Ph.D. in Education from São Paulo State University - UNESP. Master’s Degree in Education from Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso. Graduated in Visual Arts from Universidade Federal de Uberlândia. Professor at the Universidade Federal do Tocantins, Brazil. He has experience in Education, focusing on Art/Education, acting on the following subjects: Visual Arts, Art Teaching, Youth and Adult Education, Teacher Training, Comics Books, Literacy Aesthetic and Cultural-Historical Theory. He is a professor at the Universidade Federal do Tocantins, campus of Tocantinópolis, in the course degree of Rural Education with Qualification in Arts and Music. It is important to highlight that this research on indigenous people is part of a broader project on literacy aesthetic and adult education.

Notes

1. They were men who had the objective of capturing fugitive slaves and looking for precious stones in the interior of Brazil.

2. Term used to designate people who seize other people’s land through false deeds (Araújo, Citation2018b).

3. The research is part of a larger project approved by the Ethics and Research Committee (CEP): 59,558,116.6.0000.5406.

4. One of the disciplines is called “Life History”.

5. In order to comply with the ethical principles of research with human beings and the National Foundation of the Indian (FUNAI), their identities were preserved. Therefore, we use codes (EI = Indigenous Student) to refer to the indigenous participants in this study. We also emphasize that the school institution issued authorization to conduct this study.

6. This is a Social Income Program for families in extreme poverty in Brazil designed to protect them from this vulnerability.

7. One is the approval of Law no. 13.278/2016, which, for the first time in the history of Brazilian education, places the mandatory Visual Arts, Dance, Theater, and Music (this, in fact, has been mandatory since 2008) in the curriculum of Basic Education Brazilian schools (Brasil, Citation2016, Citation2008).

8. Studies by James Catterrall (PhD from Stanford University and Director of the Creative Research Center at the California Institute of the Arts) (Barbosa, Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

9. Babassu straw refers to “the leaf as the art most used by extractivists, its leaves measure up to 8 to 9 meters in length each, each plant has about 40 stems”. (Silva et al., Citation2017, p. 207); that is, it is a plant native to their territory that they use to produce the mat, the coufo, the basket, and to cover their houses.

References

- Albuquerque, F. E. (2008). A situação sociolinguística dos Apinayé de Mariazinha. Cadernos De Letras Da UFF, 18(36), 75–22. http://www.uft.edu.br/lali/uploads/04_cadernosdeletrasdauff001.pdf

- Albuquerque, F. E. (2012). Educação escolar indígena e diversidade cultural. América.

- Almeida, S. A. (2012). A educação escolar Apinayé de são josé e mariazinha: Um estudo sociolinguístico. Editora da PUC Goiás.

- André, M. (1984). Estudo de caso: Seu potencial na educação. Cadernos De Pesquisa, 14(49), 51–54. http://publicacoes.fcc.org.br//index.php/cp/article/view/1427/1425

- Araújo, G. C. (2018a). The arts in Brazilian public schools: Analysis of an art education experience in Mato Grosso state, Brazil. Arts Education Policy Review, 119(3), 158–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2016.1245164

- Araújo, G. C. (2018b). The aesthetic literacy in the consolidation of the reading and writing processes of young and adults of the rural education [Doctoral Thesis], São Paulo State University - UNESP, Marília.

- Araújo, G. C., & Oliveira, A. A. (2015). The teaching of art in adult education: An analysis from the experience in Cuiabá city, Brazil. Educação E Pesquisa, 41(3), 679–694. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/s1517-97022015051839

- Araújo, G. C., Oliveira, S. B., & Almeida, L. S. (2019). The training of art teacher in Tocantins: Old challenges and problems in Brazilian education. Laplage Em Revista, 5(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24115/S2446-6220201952638p.176-189

- Araújo, G. C., & Santos, G. (2020). Art in the village: Analysis of an experience with indigenous Apinayé from Special Education. Eventos Pedagógicos, 11(1), 1–24. http://sinop.unemat.br/projetos/revista/index.php/eventos/article/view/3663

- Arrazola, B. V., & Bozalongo, J. S. (2014). Teaching practices and teachers’ perceptions of group creative practices in inclusive rural schools. Ethnography and Education, 9(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2014.881721

- Arslan, L. M., & Iavelberg, R. (2009). Ensino da Arte. Cengage Learning.

- Barbosa, A. M. (1998). Tópicos Utópicos. C/Arte.

- Barbosa, A. M. (2010). Arte Educação no Brasil. Perspectiva.

- Barbosa, A. M. (2017a). O dilema das artes no ensino médio no Brasil. Pós:Revista Do Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Artes, 7(13), 9–16. https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/revistapos/article/view/15702

- Barbosa, A. M. (2017b). Artes no ensino médio e transferência de cognição. Olh@res, 5(2), 77–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.34024/olhares.2017.v5.746

- Barbosa, A. M. (2017c, November 22). Educação sem arte, educação para a obediência. Entrevista Concedida Ao Jornal Extra-Classe, 22(219). https://www.extraclasse.org.br/geral/2017/11/educacao-sem-arte-educacao-para-a-obediencia/

- Brasil. (1971). Lei no. 5.692 de 11 de agosto de 1971. MEC.

- Brasil. (1998). Referencial curricular nacional para as escolas indígenas. Ministério da Educação.

- Brasil. (2008). Lei nº 11.769 de 18 de agosto de 2008: Altera a Lei n° 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, para dispor sobre a obrigatoriedade do ensino da música na educação básica. Câmara dos Deputados, Edições Câmara.

- Brasil. (2013a). Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional - LDB: Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional (8. ed.). Câmara dos Deputados, Edições Câmara.

- Brasil. (2013b). Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais da Educação Básica. MEC; SEB; DICEI.

- Brasil. (2016). Lei n. 13.278 de 2 de maio de 2016. MEC.

- Brasil. (2017a). Lei n. 13.415 de 16 de fevereiro de 2017. MEC.

- Brasil. (2017b). Base Nacional Comum Curricular – BNCC: Educação é a base. MEC.

- Brasil. (2020). Portaria no. 1.122 de 19 de março de 2020. Define as prioridades, no âmbito do Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações (MCTIC), no que se refere a projetos de pesquisa, de desenvolvimento de tecnologias e inovações, para o período 2020 a 2023. Diário Oficial da União. Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovações e Comunicações. Retrieved July 24, 2020, from http://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-n-1.122-de-19-de-marco-de-2020-249437397

- Câncio, R. N., & Araújo, S. M. S. (2016). In the border of faith: Education, knowledge and cultural practices of “Rezadores de Almas”. Revista Cocar, 10(20), 185–211. https://periodicos.uepa.br/index.php/cocar/article/view/971

- Carjuzaa, J., & Ruff, W. G. (2017). Revitalizing indigenous languages, cultures, and histories in Montana, across the United States and around the globe. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1371822. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1371822

- Cohn, C. (2001). Culturas em transformação, os índios e a civilização.

- Course Pedagogical Project. (2017). Course pedagogical project for the tekator indigenous state school. State Department of Education.

- Course Pedagogical Project. (2019). Course pedagogical project for a degree course in rural education with a degree in arts and music. Federal University of Tocantins.

- Feitosa, L. B., & Vizolli, I. (2019). Violence, struggle and resistance: Historicity of rural education to indigenous school education. Revista Brasileira De Educação Do Campo, 4, e6233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20873/uft.rbec.v4e6233

- Franco, C. P. (2018). An Ethnographic Approach to School Convivencia. Educação & Realidade, 43(3), 887–907. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623674800

- Fundação Nacional do Índio - FUNAI. (2018). Ministério da Justiça. Retrieved March 15th, 2020, from http://www.funai.gov.br/

- Geertz, C. (2008). Interpretation of cultures (13th Reprint ed.). LTC.

- Guardian. (2020). Brazil’s Bolsonaro unveils bill to allow commercial mining on indigenous land. The Guardian: London. Retrieved April 19th, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/06/brazil-bolsonaro-commercial-mining-indigenous-land-bill

- IBGE. (2010). Censo demográfico 2010: Características gerais dos indígenas.

- Johnson, T. (2011a). Languages dying off around the globe. McClatchy Newspapers (MCT). Arc Publishing. Retrieved February 12th, 2020, from https://www.popmatters.com/article/144425-silenced-voices-languages-dying-offaround-the-globe/.

- Johnson, T. (2011b). When voices go silent. McClatchy News Services. The Wenatchee World; Jeffrey Ackerman. Retrieved February 13th, 2020, from https://www.wenatcheeworld.com/news/world/when-voices-go-silent/article_6b7a26eb-7f96-509a-8542-03efa0b99d10.html

- Lakatos, E., & Marconi, M. A. (1991). Metodologia Científica. São Paulo: Atlas