Abstract

While the adaptive nature of classroom teaching among teachers, learners, and materials has been well noted, there is little literature on how to represent the activities where teachers selectively leverage material resources to design and enact instruction in language classrooms. This paper is mainly methodological and conceptual, which proposes an approach to analyzing materials use in language classrooms. Building on the instructional design arc model proposed by Remillard, we introduced the materials use arc (MUA) as a unit of analysis to represent one pedagogical episode of a lesson prompted by the teacher and defined by an identifiable pedagogical purpose. By drawing on observational and interview data from two English-as-a-foreign-language teachers in one university in China, teachers’ MUA maps were then portrayed as examples to visualize the episodic and emerging contours of the enacted instruction. This innovative analytical tool offered the methodological potential for comparing and contrasting materials use within and across individual teachers in various language education contexts. It is hoped that the findings of this study will advance our limited theoretical understanding of the on-the-spot materials use that prevails in language classrooms both locally and globally.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

We provide an innovative approach, i.e., the materials use arc (MUA) as a unit of analysis to represent one pedagogical episode of a lesson prompted by the teacher and defined by an identifiable pedagogical purpose, to analyzing language teachers’ use of materials at the discourse level. The study is mainly methodological and conceptual. The findings will advance our limited theoretical understanding of the on-the-spot materials use that prevails in language classrooms both locally and globally.

1. Introduction

In language education, the pivotal role of materials in terms of defining the content of teaching has been well documented (Littlejohn, Citation2011). Prior studies have provided convincing evidence that textbooks alone constitute the legitimate curriculum in language classrooms across the world (Guerrettaz & Johnston, Citation2013; Karvonen, Tainio and Routarinne, Citation2018). Scholars in materials development have long reached the consensus that materials are adapted systematically or intuitively in teachers’ daily practice (Garton & Graves, Citation2014; Harwood, Citation2017; Tomlinson, Citation2012). However, how teachers translate the materials into “lived” instruction is still under-explored (Li, Citation2020; J Remillard, Citation2018). Recent educational studies have noted that teachers’ approaches to using materials have a significant impact on teaching and thereby students’ learning. In other words, materials are what we teach, what we teach indeed matters to how we teach, and thereby how students learn (Steiner, Citation2018). As such, it is a propitious time for us to probe into teachers’ daily work of materials use.Footnote1 through mapping the relationship between the materials and enacted instruction at the classroom level.

To address this issue, this heuristic study has developed an analytical tool to represent and examine the ways in which teachers use materials in language classrooms, i.e., the materials use arc (MUA) model. It builds on the assumption that classroom teaching encompasses a range of adaptive activities where teachers selectively leverage materials to design and enact instruction in the classroom ecology (Guerrettaz & Johnston, Citation2013; Matsumoto, Citation2019). MUA refers to a pedagogical episode with a distinct pedagogical purpose entailing a series of interactions among teachers, learners, and materials (Li, Citation2020). An MUA is a unit of analysis to represent how teachers and learners construct the pedagogical episode through the use of materials in light of instructional goals. Thus, one teacher’s lesson is consisted of a plethora of MUAs, which will constitute the teacher’s MUA map of a lesson and demonstrate the characteristics of the teacher’s materials use in classroom settings. It is hoped that the MUA model will facilitate the comparison and contrast of materials use within and among teachers. Drawing on the similarities and differences of one individual teacher or a group of teachers’ use of the same materials, it is possible to identify teachers’ distinct features of materials use and thereby add to our limited theoretical understanding of this ubiquitous yet under-specified teaching phenomenon that prevail in language classrooms.

2. Literature review

2.1. Approaches to adapting materials in ELT

The literature review starts with looking at the term “adaptation,” which is broadly used in the field of materials development in ELT and has various interpretations. Madsen and Bowen (Citation1978:3) believed that effective adaptation is to balance the tensions among “teaching materials, methodology, students, course objectives, the target language and its context, the teacher’s personality, and teaching style.” To accomplish this goal, teachers may use a variety of techniques to supplement, edit, expand, personalize, simplify, modernize, localize or modify cultural or situational content (Madsen & Bowen, Citation1978). Tomlinson (Citation2011) noted that the process of adapting entails reducing, adding, omitting, modifying, and supplementing. According to McGrath (Citation2013), adaptation has two layers of meanings: adaptation as addition and adaptation as change. Adaptation as addition means that teachers adopt what the textbook contains and supplement materials from other resources through extemporizing, supplementing, exploiting, or extending (McGrath, Citation2013). Adaptation as change is in line with McDonough et al.’s (Citation2013) definition, and they unveiled two supportive processes for adaptation, i.e., first evaluating the materials against contextual criteria, and then customizing the materials to cater to these standards through adding, deleting, modifying, simplifying and reordering.

Although suggestions on how to adapt materials are crucial for the effective use of materials in theory, the on-the-spot use of materials is still under-researched (Remillard, Citation2018).Footnote2 There are only a handful of classroom-based empirical studies on materials use in ELT.

2.2. Materials use research in ELT

It is only recently that researchers have begun exploring how materials are used inside language classrooms (Matsumoto, Citation2019). After extensively reviewing empirical studies of materials use in language classrooms, Tomlinson and Masuhara (Citation2018) identified two primary research foci, namely teachers’ approaches or techniques of adaptation (how) and the rationales for their adaptation (why). Among the “how” Shawer (Citation2010, Citation2017)) advanced our understanding of the classroom-level curriculum.Footnote3 development through conceptually categorizing 10 EFL college teachers’ approaches to attending to curriculum materials in the U.K. The EFL teachers were theorized as curriculum developers, curriculum makers, and curriculum transmitters depending on the congruence that their curriculum approaches were with the original curriculum materials. Guerrettaz and Johnston (Citation2013) examined the use of an English grammar textbook at a large public university in the U.S. The powerful role of materials in the ecology of the language classroom was highlighted concerning three issues. First, the materials alone constituted the legitimate curriculum of the class. Second, classroom discourse was strongly influenced by the materials in terms of topic, type, and organization of discourse. Third, language learning occurred when the content of the materials and the students’ lives were connected. These studies proved the adaptive nature of materials use even at the level of classroom discourse in language classrooms.

The “why” studies were to unravel the influencing factors in materials use, including teaching environment (e.g., at national, regional, institutional, cultural levels), learners (e.g., age, language level, prior learning experience, learning styles), teachers (e.g., personality, teaching styles, beliefs regarding teaching and learning), curriculum (e.g., objectives, syllabus, intended outcomes), and materials (texts, tasks, activities, visuals, teacher book, multimedia extras, etc.) (Tomlinson & Masuhara, Citation2018).

In sum, the slim body of research in ELT illuminates the complex and multifaceted nature of materials use. However, until now, no studies have been consolidated to generate an analytical tool to represent how individual teacher uses materials, particularly in language teaching contexts although similar studies have been done in mathematics (see, for example, Machalow et al., Citation2020; Remillard, Citation2018).

2.3. Materials use research in mainstream education

Albeit with the limited research in materials use in ELT, research in mainstream education has generated detailed descriptions and explications of how and why teachers use curriculum materials. Two studies are worth mentioning due to their analytical innovations in examining and representing materials use.

In the first study, Sherin and Drake (Citation2009) proposed an analytical framework to examine how teachers engage with the materials. They analyzed ten elementary school teachers’ use of a non-commercially published curriculum and subsumed teachers’ interactions with materials at three different phases, i.e., before, during, and after the lesson. In each phase, three key processes of materials use were identified, i.e., reading, evaluating, and adapting. By using this analytical tool, each teacher’s unique curriculum strategy was presented and analyzed to make cross-case comparisons. In the second study, Brown (Citation2009) examined three middle school teachers’ use of the curriculum materials for a ten-week inquiry-based science unit. He generalized three ways of materials use, i.e., offloading (relying on curriculum materials), adapting (changing curriculum materials), and improvising (devising spontaneous curriculum approaches). The theoretical assumption in this study is that teaching is design, and teachers make design decisions when using materials to craft instructional episodes (Brown, Citation2009; Remillard, Citation2018).

Although both studies contribute to the theorization of materials use at classroom levels, they only focused on the interaction between materials and teachers while lacking a substantial description of such processes at the level of classroom discourse, i.e., teachers’ interactions with students and instructional materials to construct instructional episodes.

3. Theoretical perspectives

This study builds on two overlapping theoretical perspectives: teaching as design (Brown, Citation2009) and a participatory view of the enactment of materials (Remillard, Citation2005). From Brown’s (Citation2009) perspective, teachers are critical decision-makers when designing and enacting instruction through the use of materials. This view indicated the interactive and dynamic relationship between humans (e.g., teachers and students) and tools (e.g., multimodal materials). From the participatory perspective (Remillard, Citation2005), teachers’ agentive power of adapting materials only represents one side of the story. As reviewed in the literature, materials use is also influenced by other factors, including students, features of materials, and the context. The fundamental theoretical thread running through these two perspectives is Vygotsky’s (Citation1978) notion of practice that is goal-oriented and mediated by tools. Materials are regarded as artifacts or tools (Vygotsky, Citation1978) with the potential to mediate human activity. In other words, the activity of materials use is the result of a participatory relationship among all elements of classroom ecology, such as teachers, students, and materials in certain educational contexts, which echoes with the ecological perspective in language classrooms (Van Lier, Citation2004).

4. Methodology

4.1. Setting and target materials

This study was set in China, where currently, there are more than 26 million university students (National Bureau of Statistics of China, Citation2018). The setting was chosen as one typical institution in Chinese higher education due to its academic status (i.e., it was funded by the Chinese government’s “Double First-Class” projectFootnote4). All university students other than those majoring in English need to take a compulsory English course, i.e., College English, for at least one year, depending on their entry-level of English proficiency in China (Xu & Fan, Citation2017). Textbooks for College English are compiled by scholars and adopted by the local institutions to represent the designated curriculum (Liu & Wu, Citation2015). To date, more than 200 universities have adopted the target textbook series (New Standard College English) for College English courses.

4.2. Participants

The teacher participants (Fiona and Penny, both pseudonyms) were female non-native English speakers with master’s degrees. They were selected due in part to practical considerations (i.e., the teachers’ willingness to discuss and reflect on their materials use), and in part to being information-rich cases in terms of educational background and teaching experiences. Both teachers were teaching the same course to students at the intermediate language proficiency level, using the same materials, and working at the target university. lists the demographic information of teacher participants.

Table 1. Demographics of teacher participants

4.3. Data sources

The data set consists of lesson observations, teachers’ post-lesson interviews, and the documents. I observed two complete units of lessons per teacher. Totally 18 lessons (45 minutes per lesson) were video recorded. shows the number and content of the observed lessons. Post-lesson interviews were designed and recorded to uncover teachers’ reflections on materials use. All the materials, including the students’ book, teachers’ guide, auxiliary PowerPoint slides, and teacher-designed materials in various modalities, were collected as the documentary data of the study.

Table 2. Summary of lesson observations

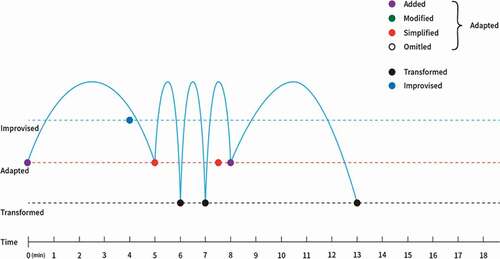

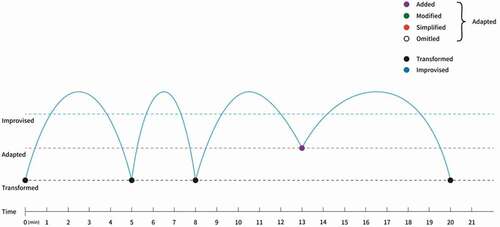

4.4. Data analysis

The data analysis is divided into two major stages. First, the lesson observations in the form of classroom interactions were transcribed verbatim (see ). By comparing and contrasting the enacted instruction with the given materials and referring to adaptation approaches in ELT (e.g., McDonough et al., Citation2013; Tomlinson, Citation2011), I coded three ways in which teachers utilized materials via classroom discourse, i.e., transforming, adapting (including adding, modifying, simplifying, and omitting), and improvising. The definitions of these codes will be given below in the findings section (cf. Li, Citation2020). Second, by drawing on the instructional design arc model (i.e., an approach to representing and examining the relationship between curriculum resources and the performance of teaching, to analyze teachers’ design work) (Remillard, Citation2018), the MUA model was proposed to visualize how teachers translated the materials into classroom interactions. By using the MUA model, two teachers’ lead-in activities were portrayed into MUA maps (see ) to exemplify the implementation of MUA.

5. Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained for all participants in the study, and confidentiality was addressed using pseudonyms for the teachers. All transcriptions and lesson observations were given to the participants for member-checking.

6. Findings

The findings unveiled that the teachers would transform, adapt, and improvise when using materials in classrooms to cater to students’ needs, to maintain the fluidity of the classroom discourse, and to execute pedagogical agendas. The transformation refers to changing the modes of materials, such as from written texts to verbal interactions, without changing the content. Adaptation became manifest in classroom discourse as teachers supplemented extra activities, modified the given instruction, simplified the requirements of tasks, and omitted materials. Improvisation occurred when teachers inserted new knowledge or tasks spontaneously while transforming or adapting the materials. A brief delineation of three ways of materials use in classroom settings will be presented with concrete examples in the following sections.

6.1. Transforming

In most cases, the enacted instruction was heavily reliant on the textbook. Teachers merely transformed the modes of the materials from written texts into verbal interactions. For instance, teachers enacted sentence completion exercises in the mode of IRF/E: teacher Initiation, student Response, and teacher Feedback or Evaluation (Sinclair & Coulthard, Citation1975). reproduces a lead-in task in Unit 7 of Book 2, and shows how teacher participants partly enacted the same exercise.

Table 3. A lead-in exercise in Unit 7 of Book 2

Table 4. Teachers’ partly enactment of the lead-in exercise

As shown above, both teachers adopted the same interactional mode, i.e., IRF/E, to enact this sentence completion exercise.

6.2. Adapting

It revealed that teachers would add extra materials, modify or simplify the given materials to execute their pedagogical agendas, and to maintain the fluidity of classroom discourse.

6.2.1. Adding

When enacting lead-in activities, all teachers supplemented materials (see ). outlines the two teachers’ enacted lead-in activities in unit 7 of Book 2 with the origins and length of each activity in the corresponding brackets.

Table 5. Comparison of teachers’ enacted lead-in activities

Where the teachers used the same materials (i.e., Penny’s activity 3 and Fiona’s activity 2), these were all taken from the textbook, and the rest of the activities were added by on their own.

6.2.2. Modifying

It was observed that teacher would specify the instruction by either adhering to or expanding the original pedagogical goals of the given materials. For instance, Penny adapted the given task of testing students’ English-to-Chinese translation skills into an integrated activity to cultivate students’ oral and translation skills. In , the instruction of the original task “Look at the pictures and identify what fables they refer to in Chinese” was changed into “Tell the complete stories of these fables in groups” together with five more pictures. These two activities were divergent in terms of both content and pedagogical goals.

Table 6. Penny’s modification of an activity

6.2.3. Simplifying

Teachers not only supplemented materials to enrich the activities but also simplified the given materials to maintain the fluidity of the classroom discourse. For instance, when enacting an activity (Talking Point of Unit 4 in Book 2) of asking students to rank ten contributing factors in people’s early childhood to personalities as adults, Fiona merely let her students select the most important factor, as this interview excerpt shows:

I think it is hard to say which one is more important than the other. So when doing this kind of exercise, I will let my students choose the most important one, only one, and illustrate their rationales. (Fiona’s post-lesson interview)

6.2.4. Omitting

Teachers also deliberately omitted some teaching content. For instance, as shown in , Penny prepared six pictures for the activity. She only asked students to describe three out of the six pictures due to the limitation of time.

6.3. Improvising

Teachers’ improvisation mainly manifested itself by inserting new knowledge or tasks. For instance, in Extract 3, when teaching the new word “glide,” Penny improvised a translation task (line 8), which was stimulated by the word “reefs” occurring in her sample sentence (lines 2 to 4).

Extract 3. Penny’s improvisation of a translation task

In sum, teachers demonstrated three major ways of using materials in classroom settings. In the following sections, Penny’s and Fiona’s MUA maps () were portrayed to demonstrate their enacted lead-in activities of the same unit and to exemplify the implementation of this analytical tool. Then I will draw on the two MUA maps to compare and contrast two teachers’ divergent approaches of on-the-spot materials use.

7. Visualizing the two teachers’ enacted lead-in activities in MUA maps

7.1. Example one: Penny’s lead in activities

The MUA map for Penny was from the lead-in segment of her lesson in Unit 7 of Book 2. The timeline along the bottom of the map represents the time of the lesson in minutes. The colored dotted horizontal lines represent three major ways of materials use, i.e., transforming (black), adapting (red), and improvising (blue). The colored dots represent the prompts initiated by the teacher. The color of each dot indicates the relationship between the prompt and the materials, i.e., transforming (black), adding (purple), modifying (green), simplifying (red), omitting (black circle), and improvising (blue). The arc represents a pedagogical episode (an activity or task), which is initiated by the teacher and defined by an identifiable pedagogical purpose. An arc ends when a new instruction was offered, which usually occurred when the teacher’s pedagogical goal was met, or the teacher deemed that a new prompt was appropriate.

In this segment of Penny’s lesson, she conducted five activities as five arcs of materials use in the map indicate. Penny adapted three of the five activities as three start dots fall on the red dotted horizontal line. The purple dot followed by the first arc means that Penny started the lesson with a supplementary activity for 5 minutes (see ). In this activity, Penny assigned students in pairs to describe two of their favorite animals. Compared with the original activity of describing the characteristics of given animals, her design was more engaging through associating the task with students’ personal experiences.

The classroom discourse also proved the active participation of her students, as Extract 4 shows:

Extract 4. Penny’s enactment of a supplementary activity

At time 4 min, Penny inserted a “why” question (line 15), which was stimulated by S3’s answers (line12), marked by the blue dot. The second arc started at 5 min, marked by the red dot, indicating an activity simplified by Penny. At 6 min, Penny continued the lesson by using the given exercise (see ), marked by the black dot. The following task (i.e., fourth arc) was also drawn from the textbook, beginning at 7 min. Amid the fourth arc, at 7ʹ30 min, Penny deleted the negative views on dogs in the auxiliary PowerPoint slide, marked by the red dot (see and Extract 5).

Table 7. Penny’s supplementary activity

Table 8. Comparison of the PPT slides with Penny’s adaptation

Extract 5: Penny’s deletion of negative views on dogs

While speaking of dogs, in both western and eastern cultures, the dog represents a loyal friend, dependable friend, and they are courageous,and they are intelligent. And that’s why dogs are man’s best friends.

The purple dot followed by the fifth arc, indicating that the activity was supplemented by Penny, which lasted 5 minutes (see ). From 13 min on, Penny adopted a reading comprehension task printed in the textbook, and the end of the fifth arc implied the end of the lead-in segment of her lesson.

7.2. Example two: Fiona’s lead-in activities

The MUA map for Fiona was from the lead-in segment of the same lesson as Penny’s in Unit 7 of Book 2. In this segment of Fiona’s lesson, she conducted four activities as four arcs of materials use in the map show. Three of the four activities were transformed directly from the textbook as three start dots fall on the black dotted horizontal line. Fiona adhered strictly to the instruction of the exercises while enacting them (see ). The purple dot, followed by the fourth arc, means that Fiona ended the lead-in section with a supplementary activity for 7 minutes (see ). In this activity, the only extra activity in the lead-in segment, Fiona introduced English idioms about dogs. According to the lesson observation, Fiona first broadcast a video clip to offer the usage of three idioms in English. She then let students jot down the idioms.

Extract 6. Fiona’s supplementary task

It could be seen that Fiona’s students could hardly catch these idioms, even after their teacher demonstrated some English examples (see ). During the task, Fiona relied heavily on her PowerPoint slide and almost read through the examples without any changes.

Table 9. Fiona’s PowerPoint slides of three idioms

7.3. Compare and contrast two teachers’ MUA maps

Although two teachers were using the same materials to introduce the topic, showed the dramatic discrepancies between how Penny and Fiona enacted the materials, which had threefold implications. First, Penny’s students had more learning opportunities. One more MUA in Penny’ MUA map than in Fiona’s one implies that Penny employed one more activity. Since all activities were designed with the same pedagogical goal, i.e., to lead in the topic, more activities or tasks imply more potential for learning through the materials. Second, Penny exercised more agentic power of mobilizing materials. In Penny’s MUA map there are more adaptations than Fiona’s. Adaptations are driven by teachers’ agentive power of drawing on various knowledge resources to orchestrate pedagogical episodes (Li, Citation2020). Thus, more adaptations indicate higher levels of teacher agency in materials use. Third, more teacher learning happened in Penny’s class. Teacher learning occurred when teachers had to make decisions regarding the specific activities they were to enact with students (Davis & Krajcik, Citation2005; Remillard, Citation1999). Penny’s MUA map shows one improvisation, which means Penny made the on-the-spot decision of changing the materials to cater to students’ reactions. However, there is no sign of on-the-spot decision-making in Fiona’s MUA map, and thereby there is no teacher learning in this segment of her teaching.

7.4. Discussion

This study offers an analytical tool to measure and visualize materials use in classroom settings. The MUA map provides a powerful potential for mapping the relationship between teachers and materials at individual and collective levels. By categorizing the commonalities and discrepancies of teachers’ use of similar materials during a longer term, we may identify salient points in teachers’ materials use, which will thereby provide in-depth insights into how to make productive and effective use of materials in the long run.

First, at the individual level, teachers could explore the patterns and themes of their materials use by analyzing each MUA map of the lessons. For instance, if several MUA maps of Penny’s lead-in segments in a series of lessons were depicted, it is possible to identify the consistency or inconsistency of her using a particular type of material. The findings could raise further analytical questions, such as why the teacher made decisions on maintaining or changing the ways of materials use during class. The in-depth analysis of teachers’ MUA map will become food for thought and self-reflection towards more effective use of the materials. Wehypothesize that individual teacher’s personalized patterns of materials use, which are constructed through reflections on their MUA maps over time, will constitute their curriculum thinking, or curriculum literacy (Steiner, Citation2018) and foster teacher learning through materials use (Matewos et al., Citation2019).

Second, at the collective level, the MUA map will allow a cohort of teachers using similar materials to cross-analyze the ways of materials use in similar teaching contexts. The comparison and contrast among different teachers’ materials use will facilitate the construction of collective knowledge concerning materials use and the development of a community of practice (Wenger, Citation1998).

Third, when it comes to using this analytical tool in an empirical study, wewould suggest that the patterns of teachers’ decisions on materials use, and the factorsinfluencing teachers’ pedagogical decision-making could be interesting areas of further investigation. The MUA maps allow researchers to identify the patterns and themes of materials use in terms of the types of pedagogical episodes, time allocations, approaches to materials use, and pedagogical goals. Wehypothesize that the shifts of MUA can reflect teachers’ on-the-spot decision-making, which is influenced by a range of factors. For instance, in Penny’s MUA map, more teacher-student interactional episodes were observed in her supplementary activities than in the given ones (see ), and students were more engaged, too. This implied that teachers’ expertise in adapting materials played an essential role and is equally crucial as teachers’ interactional competence (Walsh, Citation2013) in the classroom instruction. Webelieve that through using the MUA model, more commonalities and discrepancies of materials use within and among teachers could be captured, which will, in turn, deepen our understanding of why materials are used in particular ways.

7.5. The significance of the study

The significance of this study is twofold. First, it contributes to the field of materials use in terms of theory building. Since communication in classrooms is the experienced curriculum or “hidden curriculum” (Barnes, Citation1992), analyzing materials use in classroom settings offered a way to conceptualize fidelity between the written and enacted curriculum (Remillard, Citation2018). The findings of the study remind us of the importance of looking at how materials are used because only through the enactment of materials do teachers’ plans in multi-modalities (e.g., paper-based/digital, audio/visual artifacts) become “living” teaching practice (Gueudet et al., Citation2012). In other words, classroom-level materials use is at the heart of bridging the planned curriculum and the enacted one. Different from the how-to books published in ELT materials development that merely suggest selecting and adapting materials in the phase of lesson planning, this study unveiled the situated, interactive, and complex nature of materials use. The findings of this study indicated that a nuanced and robust analysis of materials use requires looking at materials use via classroom discourse. Second, this study benefits the field of classroom discourse by adding materials to the analysis of inter-human interactions. Instead of unraveling teacher-teacher, teacher-student, student-student interactions in classroom discourse research, this study examined and represented the interactions between actors (teachers) and artifacts (materials) and thereby broadened the scope of examining the classroom instruction.

In sum, this study is mainly methodological and conceptual. Although the MUA model is proposed based on data from language classrooms, it has the potential to be transferred to other disciplines because materials use via classroom discourse addresses the general issue of how teachers use materials to design and enact instruction. The exploratory nature of our study on a limited data set would benefit from further validation in larger scale studies that look into the processes of materials use over a longer time.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zhan Li

Dr. Zhan Li is an associate professor at the School of Foreign Languages, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China. She received her doctoral degree at the Faculty of Education, the University of Hong Kong in 2016. Her research interests include English language teaching, curriculum development, professional development, and materials use. Her publications appear in both local and international journals and books. From 2021 to 2022, she will be an academic visitor to the University of Sheffield.

Mr. Hongshun Li is an associate professor at the School of Foreign Languages, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China. His research interests include translation theories and children’s literature. From 2021 to 2022, he will be an academic visitor to Durham University.

Notes

1. Materials use as a bourgeoning field refers to various ways that participants in natural learning environments actually employ and interact with materials.

2. “On the spot” use of the materials refers to the spontaneous adaptations that teachers make in classroom settings, driven by their decision-making on materials use.

3. The term “curriculum” is used interchangeably with “curriculum materials” in general education, which refers to any teaching and learning materials that are provided by the institution to represent the institution’s formal curricular frameworks or standards.

4. The “Double First-class” project is a tertiary education development initiative conceived by the People’s Republic of China government in 2015, which aimed at comprehensively developing elite Chinese universities and their individual faculty departments into world-class institutions by the end of 2050.

References

- Barnes, D. (1992). From communication to curriculum. Penguin.

- Brown, M. (2009). The teacher-tool relationship: Theorizing the design and use of curriculum materials. In J. T. Remillard, B. A. Herbel-Eisenmann, & G. M. Lloyd (Eds.), Mathematics teachers at work: Connecting curriculum materials and classroom instruction (pp. 17–14). Routledge.

- Davis, E. A., & Krajcik, J. S. (2005). Designing educative curriculum materials to promote teacher learning. Educational Researcher, 34(3), 3–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034003003

- Garton, S., & Graves, K. (2014). Identifying a research agenda for language teaching materials. The Modern Language Journal, 98(2), 654–657. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12094

- Guerrettaz, A. M., & Johnston, B. (2013). Materials in the classroom ecology. The Modern Language Journal, 97(3), 779–796. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12027.x

- Gueudet, G., Pepin, B., & Trouche, L. (eds). (2012). From text to ‘lived’ resources: Mathematics curriculum materials and teacher development. Springer.

- Harwood, N. (2017). What can we learn from mainstream education textbook research? RELC Journal, 48:(2), 264–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688216645472

- Karvonen, U., Tainio, L., & Routarinne, S. (2018). Uncovering the pedagogical potential of texts: Curriculum materials in classroom interaction in first language and literature education. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 17, 38–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.12.003.

- Li, Z. (2020). Language teachers at work: Linking materials with classroom teaching. Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-5515-2

- Littlejohn, A. (2011). The analysis of language teaching materials: Inside the Trojan horse. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Material development in language teaching (pp. 179–211). Cambridge University Press

- Liu, D., & Wu, Z. (eds). (2015). English language education in China: Past and present. People’s Education Press

- Machalow, R., Goldsmith-Markey, L. T., & Remillard, J. T. (2020). Critical moments: Pre-service mathematics teachers’ narrative arcs and mathematical orientations over 20 years. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 1-27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-020-09479-9

- Madsen, H. S., & Bowen, J. D. (1978). Adaptation in language teaching. Newbury House Publishers.

- Matewos, A. M., Marsh, J. A., McKibben, S., Sinatra, G. M., Le, Q. T., & Polikoff, M. S. (2019). Teacher learning from supplementary curricular materials: Shifting instructional roles. Teaching and Teacher Education, 83, 212–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.005

- Matsumoto, Y. (2019). Material moments: Teacher and student use of materials in multilingual writing classroom interactions. The Modern Language Journal, 103(1), 179–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12547

- McDonough, J., Shaw, C., & Masuhara, H. (2013). Materials and methods in ELT: A teacher’s guide. John Wiley and Sons.

- McGrath, I. (2013). Teaching materials and the roles of EFL/ESL teachers. Bloomsbury.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2018). China statistical yearbook 2018. China Statistics Press.

- Remillard, J. (2018) Mapping the relationship between written and enacted curriculum: Examining teachers’ decision making. In G. Kaiser, H. Forgasz, M. Graven, A. Kuzniak, E. Simmt, & B. Xu (eds.). Invited Lectures from the 13th International Congress on Mathematical Education. ICME-13 Monographs. Springer, pp. 483–500.

- Remillard, J. T. (1999). Curriculum materials in mathematics education reform: A framework for examining teachers’ curriculum development. Curriculum Inquiry, 29(3), 315–342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0362-6784.00130

- Remillard, J. T. (2005). Examining key concepts in research on teachers’ use of mathematics curricula. Review of Educational Research, 75(2), 211–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075002211

- Shawer, S. F. (2010). Classroom-level curriculum development: EFL teachers as curriculum-developers, curriculum-makers and curriculum-transmitters. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 173–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.03.015

- Shawer, S. F. (2017). Teacher-driven curriculum development at the classroom level: Implications for curriculum, pedagogy, and teacher training. Teaching and Teacher Education, 63, 296–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.017

- Sherin, M. G., & Drake, C. (2009). Curriculum strategy framework: investigating patterns in teachers’ use of a reform‐based elementary mathematics curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 41(4), 467–500. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270802696115

- Sinclair, J., & Coulthard, M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford University Press.

- Steiner, D. (2018). Curriculum literacy in schools of education? The hole at the center of American teacher preparation. https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/bitstream/handle/1774.2/62968/curriculum-literacy-in-schools-of-education-final-2911-1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Tomlinson, B. (2011). Materials development in language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143–179. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

- Tomlinson, B., & Masuhara, H. (2018). The complete guide to the theory and practice of materials development for language learning. Wiley Blackwell.

- Van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Kluwer Academic.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental process. Harvard University Press.

- Walsh, S. (2013). Classroom discourse and teacher development. Edinburgh University Press.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Xu, J., & Fan, Y. (2017). The evolution of the college English curriculum in China (1985-2015): Changes, trends and conflicts. Language Policy, 16(3), 267–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-016-9407-1