Abstract

The quantitative information resulting from student evaluation of teaching (SET) surveys is used extensively in higher education to evaluate teaching faculty, to determine academic promotion and to assure quality of instructional programmes, but rarely is it the case that the qualitative information available is given much attention in the development of learning and teaching. Grounded in the scholarship of teaching and learning, this study explores English as a foreign language (EFL) teachers’ receptivity of and reaction to student qualitative feedback on various aspects of their teaching in SET surveys. Using data from a SET survey and discrete and open-ended questions gathered from 35 EFL instructors at Sultan Qaboos University in Oman, I have analysed the nature and qualities of reactions the data reveal. Questions relating to instructors’ overall receptivity to student feedback and their interaction with the data in the way they respond to student feedback and relate it to their teaching are explored. Key findings centre on the development of a quadratic typology characterising an interplay of feedback that is positive, negative, general and specific, and consisting of three orientations to feedback by instructors: blame, frame and reframe. Finally, the implications for using SET for course and teacher development are outlined and future research directions are suggested.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This research highlights the role of learners in the scholarship of learning and teaching. It specifically explores how 35 teachers in an English as a foreign language context in Oman respond to student feedback. In higher education, it is often the practice students are encouraged to rate courses and instructors by means of surveys, which are internationally known as student evaluation of teaching surveys (SETs). In theory and in many tertiary education settings, the information generated from SETs is used in the promotion of faculty, in employment and in quality-assurance of programmes. However, this paper makes the argument that there is an important formative function of SETs for teacher development i.e. that the qualitative comments given by students in these surveys could be used by instructors to reflect on and improve their teaching practice, or at least to gather information about how students perceive their learning experiences in these courses.

1. Introduction

Student evaluation of teaching (SET) is a method of instructional evaluation which is usually conducted to evaluate teaching provision in higher education, typically at the end of a course of study/semester. SET surveys, rendered in pen-and-paper or electronic questionnaire-format, are conducted by students and typically assess the teacher, teaching and course on a “cafeteria-like” style scale. SET forms may be used at the local institutional level, though there are SET surveys such as “Rate my Professor” available online (http://www.ratemyprofessors.com). SET results are usually employed for faculty tenure and promotion, etc., and rarely for teacher and course development especially in EFL, although it is readily available, and can be considered in the following of Walsh and Mann (Citation2015) a data-led approach.

The ELT evaluation literature e.g., Rea-Dickins and Germaine (Citation1992) recognizes the formative nature of evaluation, but juxtaposes this with a summative function which is often seen to be in conflict with the developmental track. Research suggests that in their efforts to resolve this functional conflict, teachers sometimes resort to reconciling student expectations with their own values and interests (Kiely, Citation2001) in what Hiver and Whitehead (Citation2018) call “sites of struggle” (p. 70). If teachers see the evaluation of their teaching not guided by a supportive purpose and/or that mentoring is not available to guide them (Karimi & Norouzi, Citation2017), a skeptical culture develops of such evaluation in which teachers doubt any role for this evaluation to improve classroom teaching and learning (Burden, Citation2008). This renders the process futile and unnecessary.

Guarding against this hazard vis-à-vis conducting developmental evaluation is a commendable yet challenging affair however; and the ELT literature discusses at length how this formative intention should be implemented though in practice this may not always be possible. Different models exist to scaffold teachers to pursue this developmental goal. For example, T. S. C. Farrell (Citation1999) demonstrates development in teaching and learning may be facilitated institutionally through 1) collaborative language teacher groups, 2) clear rules to support group activities, 3) sufficient time for reflection, 4) data to guide development such as classroom data, and 5) anxiety-free atmosphere to allow relaxed reflection. Further, other methods e.g., Centra’s (Citation1993) NVHM model emphasize the central role of the teacher. This model posits that in their encounter of new knowledge, teachers, given they have the motivation, are more likely to effect change in their classroom practice if they value this knowledge, and seek guidance on how to change.

Furthermore, the body of research in English language teacher education in teacher cognition, classroom practices, teachers’ agency and identity, and teacher learning and professional development emphasizes reflection in the preparation of pre- and in-service English language teachers. Out of this body of work, reflection is seen as yet another useful strategy in which teachers develop their practice and challenge existing beliefs and practices. In his review of reflective practice in ELT, T. S. Farrell (Citation2016) lists the data-based tools used as stimuli for English language teacher learning. In order of predominance, these include teacher discussion, journal writing, classroom observations, video analysis, action research, narrative, lesson study, cases, portfolio, team teaching, peer coaching, critical friend/incident transcripts, and finally a combination of online tools such as blogs podcasts, chats, and forum discussions (p. 237).

The fact that student evaluation of teaching (SET) was not listed as a data-based method for teacher development is not unexpected. This is because according to the present author’s best knowledge no such study exists in ELT, in stark contrast to studies in mainstream higher education which show that lecturers respond to student feedback in ways that enhance the learning experience of their students (Arthur, Citation2009). While the concept of teaching effectiveness has been explored in-depth in research on the good language teacher, it is not the same as research in SET. Research on SET is naturalistic dedicated to the exploration of teaching practices as a coherent whole as embodied in institutional teaching surveys; that is, the evaluation is seamless, and comes at the conclusion of a course of study with student comments grounded in that particular teaching experience or teacher. By contrast, research on the good language teacher is interventionist in nature, meaning that the researcher intervenes in the natural setting through the research design. Second, the current research on SET focuses especially on student feedback and the ways in which teachers perceive and respond to it rather than on what learners merely perceive to be a “good” or “effective” teacher. This means that while research on the good language teacher is about student perceptions only, recent SET research transcends these to include instructor responses to these perceptions.

The above data sources as cited in T. S. Farrell (Citation2016) all originate from teachers or from their peers. While this does not invalidate them, it means student-based sources are not exactly represented. This comes at a time when learners are increasingly seen to be co-partners in the educational process, and learners’ feedback based on student-teacher classroom data (Walsh & Mann, Citation2015), during language lessons (Ho, Citation1995), and via learner observation of teaching and learning (Khen, Citation1999) is being used in teacher development. However, the qualitative student feedback in SET, although readily available, is seldom used to demonstrate teacher development. Exploring this dimension of SET is important because of the rising need to use “various conceptual tools and perspectives to explore and understand what drives language teachers to learn and what sustains this drive” (Guo et al., Citation2019, p. 138).

The data in SET comes from the learners who are “observers in their own right” (Khen, Citation1999, p. 241). Learners have a unique voice, and can make “a valuable contribution to [the] development [of] teachers” (Gray, Citation1998, p. 29). As such, they are considered to be equal agents of change and contributory to classroom teaching and learning. While the quantitative information in SET is used in faculty evaluation, academic promotion and quality assurance of instructional programmes, to the best of the author’s knowledge little is known about how any developmental role may be sought from this data-based method in EFL settings.

To address this gap, this exploratory study specifically addresses experienced EFL instructors’ receptivity of and reaction to student qualitative feedback in SET surveys, and gauges how this interaction may have impacted their English language teaching cognition and practice. This question is addressed in relation to EFL instructors at an English Language Centre, at Sultan Qaboos University in the Sultanate of Oman.

2. Student evaluation of teaching: a bird eye’s view of the field

In one of his major reviews of research on student evaluation of teaching (SET) in general higher education, Marsh (Citation2007) listed at least 45 SET review papers with the first review dating back as early as Aleamoni (Citation1981) spanning the period between 1924 and 1998 (p. 320). Ever since Marsh (Citation2007), several other major SET reviews have appeared, markedly telling of the long and rich history of one of the most researched and controversial means of evaluating instructional performance in higher education.

2.1. The case against student evaluations of teaching

Sproule (Citation2000, Citation2002) are major critiques of SET. Sproule (Citation2000) offers two conceptual and two methodological arguments against the use of SET ratings in higher education. Conceptually, he argues that SET assumes that students are a source, or only source, in determining teaching effectiveness, raising concerns by faculty that students may not be adequately informed about effective teaching (Spooren et al., Citation2013). He also maintains that the construct under measurement, “teaching effectiveness,” is not agreed upon. Methodologically, Sproule argues that it is not admissible to consider the ratings as meaningful cardinal or ordinal indicators of teaching effectiveness. In other words, the use of the Likert-scale to compare instructors is not appropriate.

Different metaphors have emerged to supply ammunition against SET. Such surveys were described as “a necessary evil” (Ory, Citation1991, p. 33) a measure of a “teacher’s popularity” rather than teaching effectiveness (Sproule, Citation2000), and that the ratings can be bought (Wachtel, Citation1998). Some call them “happy forms” (Harvey, in Penny, Citation2003, p. 400) suggesting teachers who know how to make students happy receive higher ratings. They were also equated with “personality contests” (Kulik, Citation2001, p. 10) with the most charming and charismatic teachers bagging the highest ratings. One study even suggested a link between higher ratings and chocolate in such a way that those students who were offered chocolate gave higher ratings (Youmans & Jee, Citation2007).

2.2. The case for student evaluations of teaching

Marsh (Citation1984, Citation2007) are a major support of SET. Marsh (Citation2007) states that SET ratings are generally valid and reliable and can provide information for students, teachers and administrators. Theall and Franklin (Citation2001) respond to several myths about SET. For example, they contend that students can accurately assess instructors and instruction, there is no evidence that popular teachers are not effective teachers, SET ratings are positively correlated with student learning, there is enough general consensus on what constitutes effective teaching, ratings are not affected by gender and situational factors such as optional/required courses, they solicit feedback different from that offered by superiors and peers, and they constitute a solid indicator of teaching performance superior to anecdote and hearsay.

Furthermore, constructivist methodologies require that we as teachers move from “an isolated and impoverished transmission model” into “the rich, complex, je-tu community of our students, heeding—or at least interacting with—their viewpoints, prior knowledge, and experience” (Smith, Citation2001, p. 227). This self-examination requires that we “become learners’ of the learners” (Khen, Citation1999, p. 241) and give learner-data methods such as SET a chance to prove their contribution to teacher professional development.

2.3. Developmental line of SET research in general higher education

In terms of the purposes of SET, a thorough reading of the literature in general/higher education reveals two strands of research. Strand 1, the classic burgeoning of research in the field, is closely guided by an industrial viewpoint of education, and focuses more on the summative function of SET for uses such as academic promotion, salary raise, etc., and Strand 2, which is a new development, involves SET research informed primarily by constructivist orientations focusing on the formative functions of SET, with more recent explorations being undertaken on the role of SET as a teacher professional development tool (e.g., Ballantyne et al., Citation2000; Golding & Adam, Citation2016).

For example, Ballantyne et al. (Citation2000) illustrated the use of a booklet collaboratively designed by student and staff groups in response to student evaluations, demonstrating student and staff teaching priorities. Also, the teachers awarded teaching excellence certificates in Golding and Adam (Citation2016) exemplified the developmental role of SET, thus exhibiting high degrees of student-centredness and had formative and reflective orientations toward student evaluations.

A more recent line of inquiry addresses faculty perceptions and reaction to qualitative comments in SET. Moore and Kuol (Citation2005) found lecturers react to positive and negative feedback in various ways which showed either a teacher’s endorsement of performance feedback, commitment to execution of feedback in minority problem areas, commitment to improvement or even ego-protection. Arthur (Citation2009) also found that lecturers had feelings of shame, blame, tame and reframe depending on whether they could influence change.

2.4. Developmental line of SET research in English language education

In English language education, SET research has not kept pace in comparison to SET research in general education, and may best be described to be at the “crawling” stage, to borrow Fisk et al.’s (Citation1995) metaphor, as cited in Walker (Citation2011, p. 497). EFL SET research viewed from both stages is characterized by two shortcomings, one relating to quantity, and the other relating to quality. The first is that pertaining to Strand one, research on SET in EFL is still embryonic, restricted to addressing teachers’ and students’ perceptions in its entirety. The literature in EFL SET locatable by the present author amounts only to four studies conducted by Wennerstrom and Heiser (Citation1992) in ESL programmes in the Burden (Citation2008, Citation2009) and Al-Maamari (Citation2015) in EFL contexts in relation to Japan and Oman respectively.

Wennerstrom and Heiser (Citation1992) investigated student bias in their evaluation of their instructors in two ESL programmes at the University of Washington. The results pointed to a systematic bias due to learner’s ethnic background, English language proficiency, course content and attitude towards the course. Al-Maamari (Citation2015) found a very small significant association between teaching effectiveness and instructor gender, class size and course type (foundation vs. credit-bearing English courses) in over 2000 student ratings. These two studies are technical in nature, exploring validity and bias.

Burden (Citation2008) explored university EFL teacher views of how appropriate SET is for teacher development in Japan. Sixteen ELT teachers were presented with questions collected from 50 SET surveys and asked to judge how well they represented a communicative English language teaching approach. The findings indicated that the teachers were dubious about the information collected from such evaluations. Burden (Citation2009) was an exploration of six university EFL teachers of SET implementation in Japan. The findings suggested that teachers saw the evaluation to be threatening, and far from formative. Both studies investigated the appropriateness of the questions in the SET survey; they did not address student qualitative feedback in SET surveys.

The second shortcoming of EFL SET research is that whatever scant research available has generally stayed away from the formative potential of SET for EFL teacher development and learning, which is the mark of current research on SET in higher education in the mainstream. It is over 95 years since the first published paper on SET appeared in 1924 (Aleamoni, Citation1999), and in the year 2020, TESOL remains largely unrepresented in this research heritage.

3. SET at Sultan Qaboos university

Over the past four decades, Higher Education in the Sultanate of Oman has expanded considerably in quantity and quality terms. State-owned and private higher education institutions (HEIs) have grown exponentially and access to higher education has also widened. In addition to one public government university, there are now at least ten government colleges and approximately seven private universities and 19 private colleges in Oman offering a variety of qualifications in different disciplines. Although English is taught as a foreign language in the country with Arabic being the official language of governance and communication, almost all higher education institutions (HEIs) have adopted English as a medium of instruction (Al-Issa, Citation2007).

To match this quantitative expansion, academic programs have sought to achieve national and international quality, and towards this goal, Oman Academic Accreditation Authority was founded in 2008 to oversee the academic affairs of these HEIs (Al-Mahrooqi et al., Citation2015). Indeed, recently academic program quality has become an important concern in these HEIs, leading some of these academic programs to be recognized nationally and internationally.

At the institutional level, the Omani HEIs have instituted internal review mechanisms and established other formative systems to promote the quality of their academic programs and to contribute to the professional development of their faculty (Al-Issa & Sulieman, Citation2007). One such tool is the student evaluation of teaching (SET), which is adopted as part of the Omani higher education provision in line with international standards and procedures.

Universities in the Arabian Gulf including the Sultanate of Oman have adopted SET as one means of assessing instruction (Al-Issa & Sulieman, Citation2007). At the research site, Sultan Qaboos University, the form of SET in use is an in-house questionnaire-based electronic survey hosted on the university’s server and is dubbed the Course and Teaching Survey (CTS, henceforth).

The CTS is bilingual (English and Arabic) comprising two sections: a set of fourteen discrete statements in three core areas (instructor performance, teaching activities and course) bearing on a four-point scale (Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Agree, Strongly Agree), and a free response section, thus allowing students to express their views on what they like about the course, what difficulties they have encountered and suggestions for improvement. Students complete each CTS anonymously at the conclusion of the semester, and the results are shared with instructors after the announcement of final grades.

Summarily, for every course each instructor receives a CTS report with four means (individual mean per statement, the instructor’s section mean, the course mean, and the departmental mean). The instructors also receive the comments written by students, which are often in English and/or Arabic. Institutionally, a briefer report is sent from the SQU Administration Office containing two scores (the instructor’s teaching mean, and SMIQ). This report is used in a summative way to judge promotion and renewal of contracts, but never formatively—as a tool for teacher development. Locally, this study attempts to explore the ways in which EFL teachers at the grassroots use feedback received from students in SET—on the face of the policy makers and administrators at the ivory towers. Theoretically, this exploratory study points to a gap in the existing ELT literature in the limited formative uses to which SET data is put.

4. The research

This study belongs to inductive, exploratory research. Reiter (Citation2017) defines this type of research as a way “to make sense of the world, offering new approaches and angles, and counter-hegemonic alternatives to the act of explaining the world” where the exploratory researcher is equipped “to perceive more, better and differently” (p. 139). Applied to this research, the discourse and hegemony predominant in the SET literature centre around the judgmental function of SET especially in English language education. The developmental function to which SET can be put, an act of perceiving more, better and differently, holds great potential for teacher development, and this is where research in general higher education is making progress and English language education is lagging as was demonstrated in the review above.

This study is located at Sultan Qaboos University in Oman and addresses EFL teachers’ response to student feedback in SET at an English Language Centre. Given there is little evidence of SET data being used formatively in the setting and in the literature, the research question leading the study was formulated thus,

In what ways do experienced EFL instructors at Sultan Qaboos University respond to student feedback in the form of the written comments on a SET survey?

This core question is broken down into four areas in relation to (1) instructors’ overall receptivity towards SET, their approaches in reading SET data (i.e. students’ ratings and comments), (3) comments instructors choose to respond to, and (4) their response to student feedback.

4.1. Data gathering

A large body of empirical studies in ELT indicate reflection enhances teaching and promotes teachers’ critical thinking through encouraging teachers to collect data relevant to teaching or to examine available data. Richards (Citation2004) states that reflection “involves conscious recall and examination of the experience as a basis for evaluation and decision-making” (p. 2).

Richards (Citation2004) definition was employed as a broad framework to guide the design of the study because it encompasses (i) a conscious and critical reflection of one’s practice and (ii) acting on this understanding by planning a change. In responding to the questionnaire, instructors were expected to identify a specific student feedback area from the SET survey and additionally explain how it may have impacted their cognition and teaching practice.

4.2. The questionnaire

The questionnaire developed for this study was written in English and it comprised two sections: Section I (1–4) and Section II (A, B, C and D). Question 1 addressed the steps the respondents took upon the receipt of the SET survey. Questions 2–4 were premised on Richards (Citation2004) three part model of reflective practice i.e. the event, a recall of the event, and a response to the event. Question 2 required respondents to identify at least one comment appearing in their latest SET report. Question 3 required them to respond to the student’s comment as it relate(s) to their teaching beliefs/strategies. Question 4 asked respondents to gauge how they intend to review their teaching practice as a result of the student feedback they have identified in Question 2.

Section II of the questionnaire comprised three demographic questions (A, B & C) corresponding to gender, country of origin and teaching experience, and one attitudinal question (D) relating to instructors’ overall receptivity towards SET i.e. whether the instructors were prepared to consider change to their teaching practice. The questionnaire was designed on Google Forms, a free to use platform accompanying the Google tools suite. The questionnaire is given in Appendix 1.

As researchers “cannot escape a critical positioning of [themselves or their] interest and positionality with regard to the research conducted” (Reiter, Citation2017, p. 143), it is important to lay bare my subjectivities in this research. Before conducting this research, I was a full time instructor at the university, and had just completed a two year post as an academic administrator, where one of my responsibilities was to oversee SET administration in the context. This meant reminding instructors to encourage their students to complete the SET survey. The results of the SET survey, together with other performance measures, were used to decide on promotion, renewal of contracts, etc of the instructors at the language centre. As such, I was quite well acquainted with the setting and participants. However, at the time of the administration of the questionnaire, I was a regular instructor with no administrative responsibilities bearing on SET in the setting.

To conduct the study, I undertook purposive, expert sampling (Palys, Citation2008). Therefore, I emailed 152 English instructors inviting them to complete the questionnaire followed up with a reminder before the questionnaire closed. At the time of conducting the research, the new research committee had been inactive for two years, and therefore, a formal application could not have been made. However, completion of the questionnaire by participants was considered as agreeing to participate in the research and was taken as informed consent plus the fact that I was insider in the setting.

4.3. Participants

As stated, the three demographic questions (A, B & C) targeted instructors’ gender, country of origin and overall EFL teaching experience. Thirty-five EFL instructors working in two departments (Humanities and Sciences) at SQU English Language Centre completed the questionnaire, making up a response rate of 23% of the 152 initially contacted. The response rate relative to the population demonstrates the predominance of the summative function of SET surveys. The respondents included 27 female instructors (77%) and eight male instructors (23%). Eighty per cent of the respondents had an overall EFL teaching experience above ten years, 20% had experience ranging from six to ten years, and none had experience below six years. The respondents came from 12 countries: Armenia (3), Australia (1), Belarus (1), Canada (2), India (7), Iran (1), Oman (5), the Philippines (1), Sri Lanka (1), Tunisia (2), the UK (4), and the USA (3), and four did not indicate their nationality.

4.4. Data analysis

Immediately, after the questionnaire closed, I imported the data into WEFT-QDA free software for analysis. To analyse the data, I adopted the principles of a grounded approach. This meant that I did not formulate any a priori categories, thus allowing these to emerge from the analysis. I adopted a mixed methods model to make sense of the data by pursuing both quantitative and qualitative information.

As such, my analysis of the data was driven by both the recurring patterns in the teacher responses as well as key highlights or “gems”, as it were, in an attempt to focus on both the explicit and implicit (Morse, Citation1995, p. 148). This also enabled me to focus on “contradictions and forces in tension, working in different directions”, go beyond “the common knowledge” in SET and not contend with “simplistic, dualistic models” (Reiter, Citation2017, p. 147). Examination of the teachers’ responses to qualitative student feedback revealed those lay on a continuum and were more complex rather than clear cut or polarized.

5. Findings

In this section, I present the 35 respondents’ general inclination towards student feedback, their reading approaches of the SET data, the comments they focused on, their perceptions of the evaluations, and finally the changes they reported to have made in response to student feedback. In the Discussion section later, I relate these findings to the body of the literature in SET.

5.1. Respondents’ approaches towards student feedback

Questions A, B, and C were used above to describe the study participants. Question D gave the respondents the option to indicate their general inclination towards student feedback in the SET survey. The results were as follows:

69% (n = 24) reported they were willing to consider change to their teaching as a result of the student feedback in the form of student comments in SET;

23% (n = 8) reported they treated student feedback merely as a method into their student cognition, and did not consider it necessarily with a view to changing their teaching practice; and

8% (n = 3) claimed they did not subscribe to either option.

Overall, 92% of the respondents were receptive to student feedback and perceived it to be useful to them.

5.2. Respondents’ approaches to reading SET data

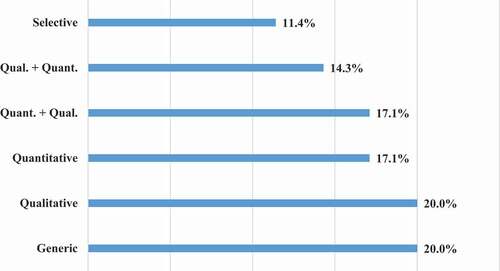

Question 1 asked respondents how they approached the reading of the information in the SET survey. summarizes the adopted reading approaches.

Twenty per cent (n = 7) of the respondents reported general actions (generic) represented by such statements as: “I read the results; I check survey”. Another 20% reviewed the student feedback in the free response section (qualitative) and wrote statements such as: “I read carefully students’ comments/suggestions”, 17% (n = 6) surveyed the CTS statements (quantitative) and included comments such as “I check my scores to see if my students were satisfied with my instruction”, and another 17% surveyed the student ratings before they examined the student qualitative feedback (quant./qual.). This included statements such as “I read the score out of 4 first. I then read the students’ comments on the open-ended questions”. A total of 14% (n = 5) reviewed the student comments before they viewed the student ratings (qual./quant.). An example statement here included: “First I read the students’ comments. Next, I check to see where my highest and lowest points are”. Finally 11% (n = 4) of the respondents were selective, i.e. the respondents concentrated on the relevant/irrelevant or positive/negative comments/items including statements such as “I highlight positive and negative areas, and those which are different to my idea of how things went that term”. In the whole, 11 of the respondents followed a mixed approach in the sense that they read the combination of qualitative (students’ comments) and quantitative data (discrete items).

Furthermore, the data showed three respondents used a further strategy (learners’ mother tongue) in the free response section to make sense of student feedback:

I access the reports, read the student comments and look at my scores overall. I then ask my Omani colleagues or Arabic-speaking friends to translate any comments that are not in English. [Participant 1]

I read the comments and if they are in Arabic, I ask a peer to translate them for me. [Participant 2]

A third respondent resorted to her “smatterings” which she had learnt from an Arabic as a Foreign Language (AFL) course to interpret her students’ comments in the survey.

5.3. Feedback comments selected by respondents

Question 2 asked the respondents to select a student’s comment of particular importance/relevance to them. Comments were then coded into areas. The areas were plotted in and took four forms: teacher characteristics (29%), subject matter (26%), teaching methodology (17%) and teacher language (11%). The direction of the comments (+, -, or ±) will be discussed in the next section. Comments relating to “teacher characteristics” were identified by 10 respondents and an example statement included “A student stated my strong support and encouragement was the main reason they felt they had passed the course and I was so happy to receive this comment”. Nine respondents identified feedback relating to “subject matter” and an example statement included “Writing is not Quran. Why should we follow a strict structure?”. Six respondents identified feedback relating to “teaching methodology” illustrated by such statements as “I like the instructor’s way of explanation and how he tries to use different methods to explain the lesson”. Also, 4 respondents identified feedback relating to “teacher language” and an example statement included “My teacher’s language is easy and I can understand. She used her body language in an effective way”.

Finally, 6 responses could not be designated a pedagogical area. These were coded “other”, and were represented by such statements as “None at all because no such example is available”.

5.4. Respondents’ reaction to student feedback

While the analysis conducted for Question 2 above addressed the type of feedback area the respondents focused on from the SET survey, Questions 3 and 4 in the questionnaire addressed the respondents’ reactions to the student feedback. Question 3 gauged respondents’ reaction in the way the comment may have made them think about their teaching, and Question 4 gauged their reaction in the way it may have impacted their teaching in the classroom. Overall, three different types of responses were observed in the examination of answers to these questions.

Of the 35 reactions received, 21 respondents (60%) highlighted negative student feedback, 8 respondents (23%) focused on positive feedback and 6 respondents (17%) reported students did not volunteer any (useful) feedback. These will now be explained in turn before a typology summarizing how students’ comments are related to the EFL instructors’ feedback intake to effect change in their teaching is presented.

No feedback

This group of 6 respondents included 4 females, 5 had teaching experience above 10 years, and one respondent had experience below 10 years, 4 were willing to change teaching based on student feedback and 2 considered feedback to merely understand how students think. The ± sign in indicated “no (useful) feedback”.

These respondents reported they sought feedback, but maintained students did not write any or the latter’s comments were not “thought-provoking”. The fact that four claimed they were willing to change their teaching based on student feedback if given to them demonstrates this. They stated students “rarely put constructive feedback”; they either left the question blank, wrote “N/A”, or respondents indicated they are always improving their teaching methods, regardless of student feedback. All comments were generic in nature and lacking in substance; naturally, all respondents stated their reports provided no rationale for changing their teaching. Two example statements include:

After 4 months of commitment and effort, to read or hear the word “nothing” is not very satisfying. [Participant 3]

That the student learned NOTHING. [Participant 4]

Positive feedback

These respondents selected and focused on positive remarks. Of the 8 respondents in this category, 5 were female, all 8 had teaching experience above 10 years, 5 were prepared to consider change to their teaching, 2 saw student feedback as a mere method to understand how students think about their teaching, and one did not commit to either. The + sign in indicated respondents’ selection of positive feedback which focused on teacher characteristics (4 comments), teaching methodology (3 comments), and teacher language (1 comment).

Interesting here was that the comments took a range between specificity and generality. Exemplary statements include:

Nearly all of the comments are along the lines of “I like this teacher,”etc. [Participant 5]

One of the inspiring comments was “The teacher communicated very well with all students”. [Participant 6]

“I like the practice which the teacher gave me.” [Participant 7]

In terms of the specific feedback from Participant 6 and 7 above, the respondents’ reactions were more introspective, revealing the exact beliefs guiding their teaching. The respondents felt the praise from students reinforced their teaching, which they in turn appreciated, and drove them to giving more. The respondents’ reaction to the above comments are respectively:

They reinforce my belief that a teacher’s main job is to make the learners like him or her. [Participant 5]

The fact that my students felt that I was effectively communicating with EVERYONE in class is really a credit to me. It basically made me think of more ways to involve everyone in class. [Participant 6]

It is the teacher’s job to build up students’ confidence and raise self-awareness. [Participant 7]

Naturally, all respondents who identified positive feedback perceived it in a positive manner. However, it terms of their response to it, there was more variety determined by whether the comment was general or specific. For those comments which were specific, two respondents expressed plans to do more in the same vein, and two respondents proudly elaborated on the student comments by providing more pedagogical details. For the general comments, four stated outright they did not review their practice. One respondent commented:

Actually, I never recall reviewing my teaching practice as a result of a comment I get in CTS! And in case I did then it must have happened unconsciously! [Participant 6]

5.5. Negative feedback

Twenty-one of the respondents (60%) selected negative feedback given by students in the SET survey, and expressed willingness to consider it. This feedback was characterized by being extremely specific in nature. This group consisted of 18 female, 15 had teaching experience above 10 years and 6 had experience below 10 years, 15 were prepared to change their teaching practice, 4 were oriented to understanding student feedback, and 2 did not fit in either category. The negative feedback () came as follows: subject matter (9 comments), teacher characteristics (6 comments) and teacher language and teaching methodology (3 comments each).

Respondents here welcomed student feedback although it was negative. General feelings included realistic analysis of suggestions, commitment to improvement and reflectivity i.e. epistemic humility. Statements expressed by the respondents are listed below indicating a positive emotional reaction or stance:

It was an eye-opener! [Participant 8]

I questioned to what extent my … [Participant 9]

This comment by the student made me more alert to … I realise that sometimes I need to … [Participant 10]

It made me realise that [Participant 11]

Yes, this comment is something that had a strong effect on me. [Participant 1]

I do feel that we should [Participant 12]

comments like this made me stop to consider if maybe my … [Participant 13]

It reminded me that just [Participant 14]

It made me think about how I [Participant 15]

In this case, the student’s comment made me more aware of [Participant 16]

I could understand how [Participant 17]

The student’s negative comment helped me realize that [Participant 18]

All the 21 respondents who identified negative feedback in their evaluation reported a high degree of commitment to changing their teaching even though, as indicated earlier, 6 of them did not indicate this attitude in their overall receptivity to student feedback. A closer examination of the 21 responses to the feedback revealed there are two trends, either that instructors already introduced changes to their teaching or that they showed a clear intention to effect pedagogical change in the future. below summarizes a sample of these two types of responses from the instructors.

Table 1. Responses to student feedback vs. change in pedagogy: implemented or future

To illustrate, in response to the student negative feedback in the statement “The teacher speaks quickly”, the respondent aimed to adjust his teaching behaviour, thus:

Now, I decided to address this issue. I have ended each class by questioning my students with what I spoke about … I’m trying to make them comfortable so they will stop me if I speak too fast and they get lost. However, I am also explaining the benefits of natural speech and ways they can improve by stretching their abilities.

At other times, though this is of a lesser magnitude, respondents vowed to introduce change to their teaching as in the comments made by Participants 9, 10, 11, and 18.

5.6. Model of feedback intake by EFL teachers

below summarizes the data and presents a synthetic typology of the teachers’ reaction to student feedback in SET as a function of the interaction between the perceived positivity and negativity of the feedback, and its specificity and generality.

Figure 3. Typology of the relationship between instructor response to feedback and type and direction of feedback

The quadrants roughly correspond to the following instructor orientations to feedback:

Blame: This traverses quadrants 1 and 3. This happens where regardless of the positivity/negativity of the feedback because the feedback is general in nature, instructors blame the students for this ambiguity, and hence see no justification for making any changes to their teaching;

Same frame: where the feedback is clearly positive and specific. In this case, I suggest instructors take a stance best characterised by endorsement and reinforcement of current practice, leading to a stagnant and complacent attitude rather than improvement or change. When change is considered, it is only within the limited areas identified by the feedback.

Reframe: This is the unshaded area in the chart, where the feedback is negative and specific. Here, instructors respond genuinely to the student feedback and feel committed to introducing change to their teaching.

Based on , none of the discrete variables in the questionnaire (gender, teaching experience or general receptivity to feedback) could capture the complex picture of how instructors perceive and respond to student feedback. On the contrary, it is the direction (+, -) and the nature of the student feedback (general or specific) selected by each instructor group which determined their response to it.

In its construction of teacher response to student feedback, what this model does is place emphasis on both the instructor and student towards the feedback process. Teachers should be open to feedback from students and should encourage their students to complete SET and provide them with comments; students should be offered guidance and mentoring to provide feedback that is honest, direct, and clear.

6. Discussion

This study started with a single research question regarding the ways experienced EFL instructors at an English Language Centre at Sultan Qaboos University in Oman respond to written comments on an in-house student evaluation of teaching (SET) survey. The question was formulated in that way as a response to the negative perceptions held towards SET in the literature and in the researched context. In addition, the question focused on the qualitative feedback (student comments) rather than the quantitative information. This is because more recently research in general education has begun to explore the contribution of student comments towards professional development and teacher learning, contrary to the previous overemphasis on the quantitative information, which was mostly used for judgemental purposes such as promotion and contract renewal.

The findings of this study indicate that 92% of the EFL instructors were receptive to student feedback; however, they differed in the way they responded to this feedback. While very few instructors reported that the students’ feedback was not helpful, the majority of instructors responded to the students’ comments positively in the sense that they were ready to incorporate students’ suggestions in their teaching in the future. In this study, this variation was tracked to the nature of the feedback the students provided in the SET survey rather the discrete variables included in the questionnaire such as gender and teaching experience. This is not to negate teacher role in making this decision, but it is that this research was not designed to untangle this relationship.

Overall, the findings indicate that when the instructors perceived student feedback to be negative and specific, they responded positively to it. By contrast, when the feedback was negative and general, the instructors did not see how they were able to incorporate it. Likewise, when the feedback was perceived to be positive and specific, the instructors were not required to make any changes and it was enough to just acknowledge the feedback.

Previous research positing a positive intake of student feedback by lecturers came from general education. Moore and Kuol (Citation2005) found that lecturers who received negative feedback were more likely to plan change to their teaching. The present study qualifies Moore and Kuol’s finding in the sense that it was found that the EFL instructors planned change only when the student feedback was negative and specific. In cases where the student comments were negative but broad in nature, it was not possible for the instructors to discern how they can respond to these comments.

Another study linking student qualitative evaluation of lecturers and the latter’s reception and response to it was conducted by Arthur (Citation2009). Arthur linked lecturers’ planned change in their teaching to an interaction between negative feedback and the lecturers’ locus of control. This meant that the lecturers effected change in their teaching when the topic of the negative feedback fell in an area that the lecturers had control over. Otherwise, in cases where the students’ comments fell in areas relating to students, the lecturers were not able to introduce any change.

7. Conclusions and implications

This SET study has important implications for the implementation of student evaluations and teacher education. First, as the pitfalls of top-down continuous professional development (CPD) are well-acknowledged in the literature (Mann & Walsh, Citation2013), student evaluations provide a data-led, bottom-up CPD tool offering an emic learner perspective for reflective practice. Comments on teaching are provided by the learners themselves and are often ones grounded in practice. To gain useful feedback on the pedagogical process, the formative role that student evaluations may potentially play need to be foregrounded. Teachers and students need to know that the SET surveys are not just another additional institutional mechanism that has to be satisfied; rather, via SET students and teachers enter into a symbiotic relationship mutually benefiting the learning and teaching process in significant ways.

In an evaluation of an EAP programme in a British University, Kiely (Citation2001) draws the distinction between teacher effectiveness—“performing to externally set criteria”—and teacher development—“adjusting an internal belief system” (p. 259)—and makes the point that though these are usually seen in exclusive terms in the evaluation literature, they need not be so. This paper makes the same point: Although its quantitative information is overly used, and its summative function is foregrounded, SET, and especially the qualitative information in it, did a formative function, most visible when the instructors framed and reframed student feedback to undertake improvements in their teaching. This is the methodological contribution of this study.

Also in several places in their review article, Guo et al. (Citation2019) emphasise that “teacher educators need to support teachers” to improve the learning experience of their students. This is correct. However, we must not forget teachers are also independent decision-makers and are co-partners in initiating and effecting change. The fact that teacher cognitions are characterised by being “complex and heterogonous,” “dynamic,”, “nonlinear” and “self-organizing”

Feryok, Citation2010) is evidence of this and means the teachers exercise “agency in their classroom practice as a way of deliberately enacting their individual values, beliefs, and goals” (Hiver & Whitehead, Citation2018, p. 77), but also that student feedback about teaching and learning promotes “dialogic engaged, and evidence-based practice” (Walsh & Mann, Citation2015, p. 360).

The main strength of this study is its analysis of student feedback in SET for EFL teacher development. There is scope to reflect this work with larger groups of teachers and in different EFL/ESL contexts. However, the use of an exploratory approach and the absence of in-depth interviews highlight one limitation. Because the study is exploratory in nature, the findings are tentative and it is therefore difficult to generalize outside this researched context. Also, the lack of observational and self-reported data do not elevate the reported practices to the level of actual changes. Analysing student feedback in EFL settings poses a unique challenge in the ways these learners use a language other than their mother tongue to communicate their feedback. At least two of the respondents provided the students’ Arabic comments verbatim, and three non-native teachers of Arabic mentioned they asked their Arab colleagues for the translation of their student comments. A future line of inquiry is to conduct the same linguistic analysis conducted by Stewart (Citation2015) of a corpus of white British university student qualitative SET feedback to examine evaluative language and interpersonal positioning in texts to explore how EFL students construe and present feedback in their contribution to teaching and learning.

Finally, it is time that the teacher and student’s “worlds of difference” (McDonough, Citation2001, p. 404) be depolarized, reconciled and cohabited. SET is one useful way to do this, but this time it is for reasons to do with why the teacher and learner are primarily in the classroom—to conduce learning.

Declarations of interest: none

This is an original publication and has not been published elsewhere and has not been submitted elsewhere.

Full-research paper

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the reviewers for the insightful comments they have provided to strengthen the paper as it appears in its final version.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Faisal Said Al-Maamari

Faisal Said Al-Maamari (ORCID: 0000-0003-3640-2274) is an assistant professor of English, the English Department, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Sultan Qaboos University, Oman. Previously, he was Deputy Director of Professional Development and Community Service at the Language Centre, SQU. He has been teaching and researching in the field of ELT since 1999. He received a BA in TEFL from Sultan Qaboos University (1999), an MA in English Language Teaching from the University of Warwick (2001), United Kingdom, and a PhD at the University of Bristol (2011). His main research interests include language assessment, teacher cognition and teacher education, programme quality, and research methods. In a study published in 2016, Dr Al-Maamari addressed the reliability and validity of student evaluation of teaching (SET) using multiple regression analysis. In this study, he foregrounds the developmental role that SETs can play in the scholarship of teaching and learning. He can be contacted at [email protected].

References

- Aleamoni, L. M. (1999). Student rating myths versus research facts from 1924 to 1998. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 13(2), 153–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008168421283

- Aleamoni, L. M., & Millman, J. (1981). The student ratings of teachers. Handbook of teacher evaluation. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc

- Al-Issa, A., & Sulieman, H. (2007). Student evaluations of teaching: Perceptions and biasing factors. Quality Assurance in Education, 15(3), 302–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880710773183

- Al-Maamari, F. (2015). Response Rate and Teaching Effectiveness in Institutional Student Evaluation of Teaching: A Multiple Linear Regression Study. Higher Education Studies, 5(6), 9–20.

- Al-Mahrooqi, R., Denmann, C., & Al-Issa, A. (2015). Student perspectives of quality assurance mechanisms in an EFL program in the Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 8(5), 81–106.

- Arthur, L. (2009). From performativity to professionalism: Lecturers’ responses to student feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903050228

- Ballantyne, R., Borthwick, J., & Packer, J. (2000). Beyond student evaluation of teaching: Identifying and addressing academic staff development needs. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(3), 221–236. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/713611430

- Burden, P. (2008). ELT teacher views on the appropriateness for teacher development of end of semester student evaluation of teaching in a Japanese context. System, 36(3), 478–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2007.11.008

- Burden, P. (2009). A case study into teacher perceptions of the introduction of student evaluation of teaching surveys (SET) in Japanese Tertiary Education. The Asian EFL Journal Quarterly, 11(1), 126–149.

- Centra, J. (1993). Reflective faculty evaluation: Enhancing teaching and determining faculty effectiveness. Jossey-Bass.

- Farrell, T. S. (2016). Anniversary article: The practices of encouraging TESOL teachers to engage in reflective practice: An appraisal of recent research contributions. Language Teaching Research, 20(2), 223–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168815617335

- Farrell, T. S. C. (1999). Reflective practice in an EFL teacher development group. System, 27(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00014-7

- Feryok, A. (2010). Language teacher cognitions: Complex dynamic Systems? System, 38(2), 272–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2010.02.001

- Fisk, R. P., Brown, S. W., & Bitner, M. J. (1995). Services management literature overview: A rationale for interdisciplinary study. Understanding Services Management, 11–27.

- Golding, C., & Adam, L. (2016). Evaluate to improve: Useful approaches to student evaluation. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.976810

- Gray, J. (1998). The language learner as teacher: The use of interactive diaries in teacher training. ELT Journal, 52(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/52.1.29

- Guo, Q., Tao, J., & Gao, X. (2019). Language teacher education in System. System, 82, 132–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2019.04.001

- Hiver, P., & Whitehead, G. E. K. (2018). Sites of struggle: Classroom practice and the complex entanglement of language teacher agency and identity. System, 79, 70–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.04.015

- Ho, B. (1995). Using lesson plans as a means of reflection. ELT Journal, 49(1), 66–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/49.1.66

- Karimi, M. N., & Norouzi, M. (2017). Scaffolding teacher cognition: Changes in novice L2 teachers’ pedagogical knowledge base through expert mentoring initiatives. System, 65, 38e48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.12.015

- Khen, D. K. (1999). Through the eyes of the learner: Learner observations of teaching and learning. ELT Journal, 43(4), 240–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/53.4.240

- Kiely, R. (2001). Classroom evaluation – Values, interests and teacher development. Language Teaching Research, 5(3), 241–261.

- Kulik, J. A. (2001). Student ratings: Validity, utility and controversy. New Directions for Institutional Research, 27(109), 9–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.1

- Mann, S., & Walsh, S. (2013). RP or ‘RIP’: A critical perspective on reflective practice. Applied Linguistics Review, 4(2), 291–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2013-0013

- Marsh, H. W. (1984). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases, and utility. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(5), 707–754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.5.707

- Marsh, H. W. (2007). Students’ evaluations of university teaching: Dimensionality, reliability, validity, potential biases and usefulness. In R. P. Perry & J. C. Smart (Eds.), The scholarship of teaching and learning in higher education: An evidence-based perspective (pp. 319–383). Springer.

- McDonough, J. (2001). The teacher as language learner: Worlds of difference? ELT Journal, 56(4), 404–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.4.404

- Moore, S., & Kuol, N. (2005). Students evaluating teachers: Exploring the importance of faculty reaction to feedback on teaching. Teaching in Higher Education, 10(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251052000305534

- Morse, J. (1995). The significance of saturation. Qualitative Health Research, 5(2), 147–149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239500500201

- Ory, J. C. (1991). Changes in evaluating teaching in higher education. Theory into Practice, 30(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849109543473

- Palys, T. (2008). Purposive sampling. In L. M. Given (Ed.), The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods (Vol. 2, pp. 697–698). Sage.

- Penny, A. R. (2003). Changing the agenda for research into students’ views about university teaching: Four shortcomings of SRmoT research. Teaching in Higher Education, 8(3), 399–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510309396

- Rea-Dickins, P., & Germaine, K. (1992). Evaluation. Oxford University Press.

- Reiter, B. (2017). Theory and Methodology of Exploratory Social Science Research. International Journal of Science and Research Methodology, 5(4), 129–150.

- Richards, J. (2004). Towards reflective teaching. The Language Teacher, 33, 2–5.

- Smith, J. (2001). Modeling the social construction of knowledge in ELT teacher education. ELT Journal, 55(3), 221–227. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.3.221

- Spooren, P., Brockx, B., & Mortelmans, D. (2013). On the validity of student evaluation of teaching: The state of the art. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 598–642. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313496870

- Sproule, R. (2000). Student evaluation of teaching: Methodological critique. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8, 50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n50.2000

- Sproule, R. (2002). The underdetermination of instructor performance by data from the student evaluation of teaching. Economics of Education Review, 21(3), 287–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00025-5

- Stewart, M. (2015). The language of praise and criticism in a student evaluation survey. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 45, 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.01.004

- Theall, M., & Franklin, J. (2001). Looking for bias in all the wrong places: A search for truth or a witch hunt in student ratings of instruction? New Directions for Institutional Research, 2001(109), 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.3

- Wachtel, H. K. (1998). Student evaluation of college teaching effectiveness: A brief review. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23(2), 191–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293980230207

- Walker, J. (2011). English Language Teaching management research in post-compulsory contexts: Still ‘crawling out’? Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 16(4), 489–508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2011.630919

- Walsh, S., & Mann, S. (2015). Doing reflective practice: A data-led way forward. ELT Journal, 69(4), 351–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv018

- Wennerstrom, A. K., & Heiser, P. (1992). ESL student bias in instructional evaluation. TESOL Quarterly, 26(2), 271–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3587006

- Youmans, R. J., & Jee, B. D. (2007). Fudging the numbers: Distributing chocolate influences student evaluations of an undergraduate course. Teaching of Psychology, 34(4), 245–247. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00986280701700318

Appendix I

SECTION 1

For Questions 1–4, you may write as much/little as you think would be necessary to respond to the prompts below.

1. Describe briefly what you do after your CTS is released by SQU Administration.

2. Describe/quote (an) example student comment(s) appearing in more recent CTS evaluations (e.g., Fall 2016/Spring 2016) which caused you to stop to reflect on it/them.

3. Explain how the comment(s) above has (have) made you THINK about your teaching in terms of philosophy or principles or beliefs, etc.

4. Describe how, if at all, you have REVIEWED (or plan to REVIEW) your actual teaching practice in class in the light of the comment(s) above.