Abstract

The present study explored nominalization use in a sample of research articles (RAs) of various types in physics and applied linguistics. To this end, 134 RAs from the related journals of these disciplines were carefully selected and studied to identify occurrences ofnominalization. Results indicated that the authors in applied linguistics significantly used more nominalization than their counterparts in physics. Moreover, the analysis brought out the findings that the deployment of nominalization Type Two (i.e., processes) is significantly different from the other three types of nominalization in each discipline. Further analysis showed no significant difference among various types of RAs regarding nominalization use in physics contrary to applied linguistics. In applied linguistics, one striking result emerging from the study was the frequent use of nominalization in experimental RAs. In addition, the study suggested 15 patterns of nominalization in the empirical RAs of the two disciplines. Of these, the RAs demonstrated distinct trends in using four patterns. This study has important implications in reference to academic writing teachers and course designers.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Scientists are characterized by the desire to communicate new knowledge to other members of their academic community, and the main way of transmitting scientific research is by means of Research Articles. One prevailing feature of the language of a research article is nominalization. This study explored lexico-grammatical features of nominalization in the various types of RAs across two disciplines of Physics and Applied linguistics to enhance writers’ awareness of how to participate in their respective field’s knowledge-making practices and how the language system operates in different disciplines. Overall, 134 RAs representing theoretical, experimental and review RAs in physics and applied linguistics formed the database for this study, amounting to 751,447 words. The results showed greater use and greater variation in using nominalization in applied linguistics RA types. Moreover, the study suggested four pervasive patterns which mark disciplinary distinctions. The findings of the study can sensitize researchers interested in disciplinary studies to draw on disciplinary differences and open the path for more cross disciplinary studies.

1. Introduction

Academic writing encompasses all writing tasks that are the product of thorough research, investigation, or inquiry used for the advancement of knowledge in academic or professional settings (Ezeifeka, Citation2014). It is a form of scientific writing in which certain words, and more significantly certain grammatical constructions, stand out as more highly favored while others correspondingly recede and become less favored than in other varieties of writings (Halliday & Martin, Citation1993). Along the same line, Hyland (Citation2006) argues that a high degree of formality in academic texts is a prominent feature that is obtained through the use of lexical density, nominal use, and impersonal constructions. Put another way, academic writing, therefore, requires specialized patterns of information packaging and texture in ways which not only make for the economy of words but also retain the sophistication and erudite touch which mark a particular text as an example of academic discourse (Ezeifeka, Citation2014). One overarching strategy of packaging for expressing sufficient and sophisticated information is nominalization (Biber & Gray, Citation2013; Billig, Citation2008; Halliday, Citation1994; Halliday & Martin, Citation1993; Prasithrathsint, Citation2014). Nominalization should be the concern of English for Academic Purposes classes, certainly one of the typical domains in which an understanding of nominalization should be transmitted to a range of audiences.

As the basis for describing grammatical metaphor (GM), of which nominalization is one example, in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL), language is construed as different and interrelated options to make meanings, and it provides a clear relationship between functions and grammatical systems (Halliday, Citation1994). Systemists focus on “how the grammar of a language serves as a resource for making and exchanging meanings” (Lock, Citation1996, p. 3). To analyze texts, systemists prefer to take different approaches, so they can clarify the main functions of a text served through linguistic forms. There does seem to be a considerable emphasis given to grammatical metaphor (GM) among these features. Martin and Rose (Citation2007) elaborate on GM as involving the transference of meaning from one grammatical form to another (p. 110).

Among the lexico-grammatical realizations of grammatical metaphor, nominalization is the most common form, particularly in science and technology discourse (Tabrizi & Nabifar, Citation2013). As an essential resource for creating scientific discourse, nominalization is used for a more formal, concise, and stylistic textual representation and packaging of meaning in an economical way. Reliance on nominalized constructions is particularly prominent in academic writing (e.g., Banks, Citation2008; Halliday, Citation2004). At the grammatical level, nominalization can be treated as a resource for deriving nouns from other word classes such as verbs and adjectives (M.A.K. Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2004). Obtaining the meaning of nominalization requires the analysis of both the metaphorical and the congruent realizations (Halliday, Citation1994; Heyvaert, Citation2003). Thus, in the following example, John’s natural way of requesting his supervisor to extend his defense would be (1). We could also talk about John’s request in an incongruent manner as in (2). Taking the Hallidayan analysis, the nominalized structures like extension and disapproval are viewed as the metaphorical counterparts of extend and disapprove. These changes illustrate what is meant by grammatical metaphor.

(1) John formally requested his supervisor to extend his defense. His supervisor disapproved of this change.

(2) John’s formal request for the extension of his defense was met with strong disapproval.

As mentioned earlier, scientists are characterized by the desire to communicate new knowledge to other members of their academic community, and the main channel of transmitting scientific research is through publication (Martı́n, Citation2003). Though numerous studies keep appearing on investigating RA and its subsections (e.g., Hyland, Citation2005; Jalilifar, Citation2012; Oztürk, Citation2007; Samar & Talebzadeh, Citation2006; Samraj, Citation2002; Swales, Citation1990, to cite a few), it is the experimental RA that has been the central focus of these works. Nevertheless, despite a sizable number of studies on nominalization, as cited in our reference list, the focus of a majority of these studies has been on RA abstracts, introductions, book chapters, book reviews, science writing, newspapers, etc. Moreover, past research seems to have provided little direction regarding lexico-grammatical features of nominalization across RAs of various types since as contended by Tarone et al. (Citation1998), not all RAs are experimental (or even empirical). Academic publications are not just limited to those having the conventional experimental procedures; rather, RAs as a genre host at least three sub-genres: theoretical papers, experimental papers, and review articles (Swales, Citation2004).

The scarcity is felt even greater when it comes to the status of using nominalization in the RA sub-genres across various disciplines. Although there has been a considerable surge of attention to research on nominalization through the study of the academic texts (Biber & Gray, Citation2013; Babaii & Ansary, Citation2005; Comrie & Thompson, Citation2007; Halliday & Martin, Citation1993; Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation1999; Heyvaert, Citation2003; Jalilifar et al., Citation2014, Citation2017a; Mair & Leech, Citation2006; Moltmann, Citation2007; Rathert & Alexiadou, Citation2010; Zucchi, Citation1993), the employment of nominalization is compared either in some parts of research articles i.e., introduction or method (e.g., Jalilifar et al., Citation2017a, Citation2018) or in some chapters of academic textbooks (e.g., Jalilifar et al., Citation2014, Citation2017b) or newspapers (Tabrizi & Nabifar, Citation2013) or university students’ writing (Pun & Webster, Citation2009). These studies have however been rather limited in type and amount of data. Close textual inspection and principled methods of analysis of these studies, which deal with specific disciplinary contexts, have depicted the prevailing utilization of nominalization which plays an important role in academic discourse (Fatonah, Citation2014; Galve, Citation1998; Starfield, Citation2004; Vu Thi, Citation2012).

However, other cross-disciplinary studies have gone further in analyzing the deployment of nominalization more profoundly. More recent studies surveyed nominalized expressions as unique discourse features in academic writings across disciplines and the results showed no significant differences in using nominalizations in the intended disciplines (Ahmad, Citation2012; Hadidi & Raghami, Citation2012; Jalilifar et al., Citation2014, Citation2017a). Jalilifar et al. (Citation2017a), for example, investigated nominalization types and patterns in eight academic textbooks from physics and applied linguistics. They reported similarities in the deployment of the first three most prevalent patterns in the sample textbooks and marked disciplinary distinctions in the distribution of these patterns. Nevertheless, other studies have acknowledged marked disciplinary characteristics by the use of nominalization, (Alise, Citation2008; Holtz, Citation2009; Pun & Webster, Citation2009; Tabrizi & Nabifar, Citation2013). This disparity in the use of nominalization across various branches of science suggests that influenced by the epistemological nature of the inquiry, nominalization may be used in different disciplines to account for the nature of discipline-specific academic writing and types of RA. However, research in this area has failed to provide conclusive answers as to the distribution and function of nominalization across disciplines.

As acknowledged by the orientation of the above studies, the manifestation of nominalization in the various types of RAs (e.g., experimental, descriptive, review, and book review articles) across different disciplines has heretofore attracted scant attention from researchers. It is thus worth exploring lexico-grammatical features of nominalization in the various types of RAs across various sciences, which seems to have been underrepresented in the existing literature, to enhance writers’ awareness of how to participate in their respective field’s knowledge-making practices and how the language system operates in different academic disciplines. The need to study disciplinary differences motivates researchers to shed more light on nominalization in academic writing, investigating how nominalization is manifested in different types of RAs, representing hard and soft sciences respectively, to reveal the probable intrinsic disciplinary peculiarities in the deployment of nominalization. More specifically, the current study targeted seeking answers to the following questions:

To what degree does the distribution of nominalization differ in a comparison of the sample RA types of applied linguistics?

To what degree does the distribution of nominalization differ in a comparison of the sample RA types of physics?

To what degree does the distribution of nominalization differ in a comparison of the sample RA types of applied linguistics and physics?

Is there any general trend in the rhetorical functions of nominalization in the sample RA types of applied linguistics and physics?

2. Methodology

This comparative, corpus-based study explored the extent of nominalization deployment in the RAs of various kinds as representative of applied linguistics and physics. The study drew on the qualitative and quantitative analyses of instances of nominalization to find out whether the distribution of nominal expressions marks any disciplinary distinctions. As a further objective, the study explored whether the deployment of nominalization in each discipline is influenced by article type. Likewise, to acquire a more comprehensive picture of nominalization use, we also investigated the emergence of nominal expressions in different patterns.

2.1. Disciplinary representation

Concerning the complexity of demarcating disciplines and the analytical frameworks used to classify them, the choice of the disciplines under the study was motivated by the classification scheme of science fields which is a way of grouping disciplines into four main areas: Sciences, Social Sciences, Humanities/Arts, and Applied Disciplines (Coffin et al., Citation2003; Glanzel & Schubert, Citation2003), following a cognitive approach, that is setting the categories based on both the experience of scientometricians and external experts. As displayed in , these four main areas are placed along a continuum from sciences to applied disciplines (Hyland, Citation2009, p. 63).

One assumption is that potential similarities tend to be greater across the disciplines within one area than the disciplines across these four areas. Alternatively, differences tend to bend toward the disciplines across areas than within one specific area. Taking the above classification schemes for the main discipline areas, we included physics [PH] to represent the Sciences at the so-called hard end of the continuum and applied linguistics [AL] to represent the Applied Disciplines at the soft end of the continuum, aiming to capitalize on the differences across the discipline areas.

2.2. Research article selection

To decide on journals we consulted five experts in each discipline. To this aim, the university professors in the related departments at Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz were met, and they were asked to recommend the most important and prestigious journals they consider as essential in their discipline. Their suggested journals were then juxtaposed to arrive at a final decision on the selected materials for analysis. Those journals which were recommended by at least three of the five experts in each discipline were selected for RA extraction. This is the reason for the mismatch between the number of journals in the two disciplines. The data for analysis were taken from 11 academic journals in applied linguistics and seven journals in physics (See appendix for a list of journals). All the journals were indexed in Clarivate Analytics, each with an IF score except for one journal in applied linguistics with a zero score. Acknowledging that genres, according to Ramanathan and Kaplan (Citation2000), are dynamic and likely to be temporal, we downloaded only RAs published since 2010 onward from the respective journals. All the papers were published between 2011 and 2016 except for two experimental papers in physics which were published in 2007 and 2008.

In determining the type of articles, following Montero and Leon (Citation2007), an RA was considered theoretical if it did not contain empirical data collected by authors or if the authors neither provided their own original data nor presented re-analysis from already collected or published data. A review article, sometimes called the review essay, general article, report article or state-of-the-art paper (Noguchi, Citation2006), is essentially a literature survey on a specific issue or area of research. Typically solicited from experts in the field and appearing in annual volumes (such as The Annual Review of Applied linguistics and The Annual Review of Information Science and Technology), a review article focuses on the most recent studies and presents a re-examination of the issue in light of the reviewer’s reading of the new publications in the field (Hyland & Diani, Citation2009). The third type of an RA, an experimental RA, reports research based on actual observations or experiments. The sample of experimental RAs in this study consisted of those RAs which featured the IMRD format.

It was intended that each RA type be represented by about 30 sample RAs amounting to 90 RAs representing theoretical, experimental and review RAs in each discipline. However, not all the journals included a sufficient number of intended article types, so overall 134 physics and applied linguistics RAs formed the database for this study. All parts of an RA, after removing the acknowledgements, keywords, footnotes, headings, excerpts, the writings under the tables and figures, and the reference list, amounting to 751,447 tokens, were subjected to analysis. A corpus of this size was expected to reveal the preferences for nominalization use by the members of the academic communities in the related disciplines (Holmes, Citation1997; Ruiying & Allison, Citation2003).

To facilitate referring to the sample RAs, first the articles were numbered, and each type was abbreviated as Exp for Experimental RAs, Theo for Theoretical, and Rev for Review articles. The disciplines were also coded as AL for applied linguistics and PH for physics. The codification of nominalization tokens will later be explained.

2.3. Procedure

The first phase in the analysis was identification, quantification, and classification of nominalization instances. To locate the instances of nominalizations in the RAs, one of the researchers first read the entire text. In light of Halliday and Matthiessen (Citation1999) taxonomy of nominalizations, all occurrences of nominalizations were extracted manually. According to Halliday (Citation1999), each metaphorical wording must have its equivalent congruent wording. Therefore, in this study, to make sure that the excerpted instances truly function as nominal, the congruent domains of extracted instances were discussed, a pursuit which Thompson (Citation2004) refers to as unpacking a grammatical metaphor (arriving at or hypothesizing about a potential wording that mirrors that an instance of grammatical metaphor in its congruent domain). Besides, to ensure that instances of nominalizations were identified with a high degree of accuracy, inter-coder procedures were implemented in the second stage: to check the coding reliability, about 10 percent of the samples was cross-checked by a second coder working independently.

Text analysis is a very demanding task because it assumes possessing analytical skills on the part of the analyst to arrive at sound analyses and avoid wrong interpretations and classifications. For instance, decision on a nominalization instance or a gerund can sometimes be an arduous task. To this aim, an extensive manual checking was carried out to correctly categorize the nouns ending in—ing as either instances of nominalization derived from verbs (e.g., After giving answers), or not, for example, as a gerund (e.g., Presenting them with such a model is …). In addition, the statistical expressions like regression, standard deviation, reliability, validity, etc. were not considered as nominalized expressions. This was followed by applying Pearson correlation to calculate the reliability of the analyses. The coefficient of correlation obtained for the analysis was 0.80 which is an acceptable index. The two researchers then discussed the results and adjudicated any disagreements before the main researcher continued locating nominalization instances in the rest of the papers.

The process of analysis was pursued by counting each instance of nominalization and then classifying the instances based on the four types of nominalizations enumerated by Halliday and Matthiessen (Citation1999) (see ). First, nominalization instances were identified manually and tagged based on suffixes: nouns ending in -ity and -ness were tagged as Type 1 (deriving from adjectives, originally realizing properties); nouns ending in -age, -al, -(e)ry, -sion/-tion, -ment, -sis, -ure, and -th were tagged as Type 2 (deriving from verbs, originally realizing processes); and nouns deriving from prepositions and conjunctions were tagged as Type 3 and Type 4 respectively.

Table 1. Halliday and Matthiessen (1999) classification of nominalizations

Determining nominalization depends on discerning the congruent rewording for all of the extracted grammatical metaphors according to the fact that metaphor is defined as a variation in the expression of the same meaning (Halliday, Citation1999). However, sometimes a metaphor cannot be unpacked to yield a plausibly more congruent form and this distinguishes a grammatical metaphor from a technical term (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation1999). For example, gene expression cannot be reworded as gene expresses, considering gene expression as a technical term. When a wording becomes technicalized, a new meaning is construed which has full semantic freedom (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation1999). Almost all technical terms appear as grammatical metaphors, but grammatical metaphors which can no longer be unpacked. Note the following examples extracted from the studied articles:

Ex 1: We take an approach grounded in Conversational Analysis to analyze selected segments of talk … .(Don & Izadi Citation2011)

Ex 2: At the same time, Roberta’s use of just kidding demonstrates a consideration of face, in that … (Skalicky, Berger & Bell, Citation2015)

Ex 3: This complicated interplay of the functions of just kidding and its variants demonstrates their flexibility and usefulness for rapport management. (Skalicky, Berger & Bell, 2015)

The above bold utterances were not regarded as nominalizations since they are fixed expressions that refer to phenomena that cannot be changed. For instance, in example 1, conversation analysis is a set of methods for studying social interactions. In examples 2 and 3, consideration and management do not refer to the process of considering and managing something and cannot be replaced by a congruent form. Besides these utterances, a host of other expressions were considered as technical terms in this study; for example, iron concentration, degradation rate, centrifugation, politeness, relevance marker, genre analysis. In addition to technical terms, nouns such as participants, interviewers, supervisor, authors, exchanger, carrier, complainant, or examiner indicating agents or instruments were not regarded as cases of grammatical metaphor and thus were excluded.

Moreover, there were some general terms like function, management, generalizability, combination, engagement … which sometimes are regarded as technical terms in applied linguistics. Thus, where used as technical terms, they were not counted as examples of nominalization. Note the following examples extracted from the studied articles:

Ex 4: We were mindful that further research is needed in order to fully realize the particular functions of certain formulaic language … (Skalicky, Berger & Bell, 2015)

Ex 5: Each rhetorical function was first examined in short extracts of discourse presented on paper and without direct use of corpus data (Charles, Citation2012)

In example 4, function is a general noun which can be replaced by the congruent form of how certain formulaic language functions, but function in example 5 is a fixed expression or a technical term in applied linguistics and thus it cannot be unpacked.

To answer the research questions posed in this study, in the first stage, all occurrences of nominalizations were calculated in relation to the RA types in the selected disciplines. To keep consistency in our analysis, the data were normalized because the length of articles in each discipline was different. The nominalized expressions were, then, counted. According to Biber et al. (Citation1998), frequency counts should be normalized to the typical text length in a corpus. “If a higher basis is adopted, then the counts can be artificially inflated”(p. 264). Since the average text length of some RAs in physics was about 500 words, the researchers decided to use 500 words as the basis. Several Chi-square tests were then administered to find out the significance of nominalization exploited in different types of RAs in each discipline and between the two disciplines.

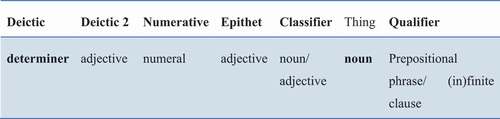

The second phase in the analysis included identification, quantification, and classification of the patterns in which the nominal groups appeared. In so doing, the main researcher extracted the patterns used in the experimental RAs through analyzing the lexicogrammatical contexts in which nominals occurred. As the purpose of this part of the study was identification and categorization of the nominalization patterns that appeared in the studied texts, the analysis of the texts ceased when dominant patterns were identified and no further similarities/differences emerged in the way these patterns were realized. The analysis of about 7 RAs from applied linguistics and only 4 RAs in physics resulted in data saturation. Extracting the patterns was made through the identification of the word order of the elements of the nominal groups in which instances of nominalization occurred. The basis for extracting the patterns was (Halliday, Citation2004, p. 320), as illustrated in :

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Comparison of the different RA types of applied linguistics

Regarding the first research question, the frequency of nominalization in the different types of RAs written by researchers in applied linguistics was counted. illustrates the related frequency and the number of nominal expressions per 500.

Table 2. Frequency of nominalized expressions in applied linguistics per 500 words

The analysis demonstrated a significant difference in terms of the deployment of nominalization among various types of articles in applied linguistics. In fact, a considerable decrease of nominalization was found with the experimental RAs compared to the other two types of articles (see ).

Table 3. Chi-square values of nominalization in applied linguistics RAs

(alpha = o.o5)

The more frequent use of nominalization in the theoretical and review articles can be explained by the differences in the nature of the two broad genres of academic discourse (empirical vs non-empirical) and the availability of a standardized text format. In this regard, according to Árvay and Tankó (Citation2004) and Pho (Citation2008), there is considerable variation in terms of the rhetorical structure and linguistic features of empirical and non-empirical articles. Authors of non-empirical RAs (Theoretical & Review articles), as Hu and Cao (Citation2011) point out, draw the required evidence from a more varied assortment of supports, including secondary sources of data, anecdotal examples, informal observations, theoretical speculations, and so on. These authors are likely to use nominalizations in their arguments, justifications and reasons more than authors of empirical research articles to give greater objectivity and formality to their thoughts, to avoid commitment and to cause their writing to sound technical or scientific.

3.2. Comparison of the different RA types in physics

To answer the second research question, the occurrences of the nominalized expressions in physics RAs were identified, and then the normalization of the data was carried out. displays the related statistical information.

Table 4. Frequency of nominalized expressions in physics per 500 words

A comparison of the frequencies indicated no major difference among various types of research articles regarding nominalization use in physics (Chi-square = 1.805, df = 2, P value = 0.4056). This suggests that the type of an article whereby a researcher conveys his/her intended knowledge has no significant influence on the deployment of nominalization. That is, irrespective of the type of an article, nominalization use by researchers in physics remains almost constant.

3.3. Comparison of the different RA types in applied linguistics and physics

The sample RA types of applied linguistics and physics were compared to find an answer to the third research question of the study. indicates that nominalization as a rhetorical strategy used in experimental, review, and theoretical RAs was variably treated in applied linguistics and physics. The use of nominalization in the sample applied linguistics RAs was more outstanding than that in physics. The greater tendency among applied linguistics writers to employ nominalizations points to the power of nominalization as a lexicogrammatical feature that can differentiate academic registers. The higher frequency of nominalization in the RAs in applied linguistics can be attributed to the greater stylistic preference of writers to create abstraction and maintain conciseness in their respective discourse via the strategy of nominalization. The underestimation of this rhetorical style by the writers in physics might allude to their inclination for the expression of abstraction through strategies besides nominalization. The difference between applied linguistics and physics RAs might reflect the attitudes of the writers of the two disciplines in construing academic knowledge. A flimsy explanation for the existing disparity, at least in relation to the empirical papers, might relate to the nature of the two disciplines, with

Table 5. Frequency of nominalization in physics & applied linguistics RAs per 500 words

applied linguistics dealing with more abstract topics (e.g., language proficiency, politeness, thematicity, metadiscourse, oral request) than physics, particularly empirical RAs (e.g., particles and nano-particles). Further research in this area is however required to arrive at a firm justification.

As indicated in , although the deployment of nominalization type two was significantly different from the other three types of nominalization in each discipline, no major frequency difference was ascribable to disciplinary variation. It is interesting to speculate on the reasons for the similarity in using the four types of nominalization across the disciplines. As Jalilifar et al. (Citation2014) contended, by preferring to use the second type (Verb to Noun) of nominalization, the author would satisfy the need for the depersonalization of the discourse, as to him underlining the effects and results of an action is more important than stressing who the author of the action is. That is why the agent is seldom expressed. Another possible explanation for the high interest in the use of deverbalization (Type 2), according to Biber and Gray (Citation2013), could be the historical shift, which began at the turn of the 20th century. This shift is the development in the use of nouns and a decline in the use of verbs in all academic writing registers (Banks, Citation2008), which suggests changes of attitude toward the nature of academic English.

Table 6. Nominalization types in various RAs per 500 words

3.3.1. Patterns of nominalized expressions in RAs of two disciplines

The subsequent qualitative analysis focused on putting the obtained nominalized expressions into their context of use to extract the most prevalent patterns used in each discipline. The investigation into the embedded patterns of nominalized expressions showed 14 common patterns for physics and 15 for applied linguistics experimental research articles.

reports the differences between the samples regarding the use of patterns in our datasets. Nevertheless, Chi-square analyses were run to help make sound conclusions about the observed discrepancies. The illustrated outcomes of Chi-square analyses, presented in , suggested statistically significant differences for patterns 1, 4, 5, and 6.

Table 7. Frequencies of nominalization patterns in the RAs

Table 8. Chi-square values of patterns in RAs of applied linguistics and physics

The distribution of patterns 1, 4, 5, and 6, which serve the textual function of increasing lexical density and information load of the texts, illustrates the disciplinary distinction. Therefore, in what follows, we only present an account of the above four patterns as distinct characteristics of applied linguistics and physics, considering the other patterns as marginal to our analysis. demonstrates that the most frequent pattern in physics and applied linguistics is pattern number 5 [Prepositional Phrase + (Premodifier) + Nominal + (Prepositional Phrase) + (Premodifier) + (Noun)], with more frequency of occurrence in physics (32.73%). Pattern 5 with the syntactic structure of [Premodifier] Head [Qualifier] contains compound and complex nominal phrases. In this pattern, the conversion of a process to an entity happens after a preposition. Put another way, nominal expressions occur after prepositions, as indicated below:

1. … as well as the changes that came with the emergence of satellites … (applied linguistics, Alfahad, Citation2015, p. 59)

In this example, the verb emerged is the unpacked form of the nominalized expression, emergence, and the congruent form is when the satellites emerged.

2. … was administered by email approximately one year after completion of the course (applied linguistics, Charles, 2014, p. 32)

3. … even after a relatively short course and in the absence of further input or help from a corpus specialist (applied linguistics, Charles, 2014, p. 33)

The congruent form of example 2 is approximately one year after the course was completed, and the congruent form of example 3 is even when the course is relatively short and further input or help from a corpus specialist is absent. In scrutinizing the corpus, it was revealed that in more than half of these utterances, the nominalized expressions are followed by preposition of, which follows Bloor and Bloor (Citation2004) claim that “the most frequent preposition in Qualifiers is of (p. 143).

Pattern 1 [(Verb) + Premodifier + (of) + Nominal + Prepositional Phrase] subsumes nominalizations that are qualified by prepositional phrases. This pattern occurs more frequently in the physics corpus (26.57%) than in the applied linguistics RAs (15.26%). In the following examples, the head noun is followed by a Postmodifier or Qualifier which is realized as a prepositional phrase (Bloor & Bloor, Citation2004). Using this pattern, the flow of information can be compacted through modifiers and qualifiers into fewer words.

4. … some statement can actually be a request for information … (applied linguistics, Alfahad, 2015, p. 60)

5. … a comprehensive study that analyzed the use of aggressive questions … (applied linguistics, Alfahad, 2015, p. 58)

6. Interviewers have control over the interview … (applied linguistics, Alfahad, 2015, p. 61)

7. … for detection of iron expression … (physics, Niu et al., Citation2013, p. 2309)

8. … for determination of blood vessel density … (physics, Niu et al., 2013, p. 2311)

9 … . after injection of Technetium-99 m-labeled PLGA nanoparticle … (physics, Niu et al., 2013, p. 2308) Results suggested significant differences in pattern 4 [Deictic + Nominal], acknowledging that using Deictic as the premodifier of nominal expressions is more popular in applied linguistics (21.72%) than in physics. The following examples were selected from the sample RAs in order to illustrate this pattern.

10. In order to compare our results with those of the Pt (II) analogue … (physics, Linfoot et al., Citation2011, p. 1199)

11. The ability to track endogenous precursors under pathophysiological conditions is therefore restricted … (physics, Eamegdool et al., Citation2014, p. 5549)

12. The studies on TiO2—DSSCs have become more diverse (physics, Lee et al., Citation2011, p. 179)

13. … based on their findings, Hyland and Tse (Citation2007) criticized the argument … (applied linguistics, Valipour et al, Citation2013, p. 250)

14. … the aim of pure mathematics is to achieve simplicity and generality by reducing … (applied linguistics, McGrath et al, Citation2012, p. 162)

15. … by clarifying the distinction between first and second order concepts … (applied linguistics, Tylor, Citation2015, p. 127)

Analysis of the sample texts also indicated a significant difference in using pattern 6 [Nominal], being more common in the applied linguistics texts (35.07) than in the physics data (19.05). In this pattern, nominal expressions are employed without any pre/postmodifiers to express generality in producing academic texts. Consider the following examples:

16. Results show that 70% of the respondents had used their corpus … (applied linguistics, Charles, 2014, p. 30)

17. … to convey knowledge which is recognized within an academic … (applied linguistics, Sheldon, Citation2011, p. 241)

18. … behaviors labelled as sarcastic do not always perform mock politeness … (applied linguistics, Tylor, 2015, p. 127)

19. Studies of the effects of potential pulse electrodeposition modes on structural … (physics, Sokol et al., 2014, p. 380)

20. Application of environmentally benign solvents instead of toxic … (physics, Khoobi et al., Citation2015, p. 217)

21. In addition to the aqueous conditions, excellent yields, operational simplicity, practicability, product purity, cost efficiency … (physics, Khoobi et al., 2015, p. 225)

In these examples, the congruent realizations of actions (what was resulted, what we know, to behave, to study, to apply, to be practical) are changed into entities (result, knowledge, behavior, study, application, practicality). These metaphoric manifestations refer to entities in general where their hypothetical unpacked versions cannot state such generality. Here, the authors in applied linguistics deploy nominalizations without any pre/post modifiers to convey the generality of their intended information. However, in comparison with other significant patterns, the occurrence rate of pattern six was small in both areas (731 instances (7.01%) in applied linguistics and 112 instances (3.81%) in physics).

The results highlight the fact that writers in these two different fields, irrespective of the common patterns, draw on distinct patterns to develop their arguments, establish their credibility, and persuade their readers. This conspicuous difference across disciplines, as revealed by our analysis, stems from the more polemic nature of linguists as authors and the more argumentative characteristics of linguistics texts vis-à-vis physicists and physics texts. Thus, in communicating scientific knowledge, linguists forge series of arguments and discussions and reiterate them in the brief form of nominalization through using the above patterns. However, the authors in physics mostly prefer to use different patterns via which they would be able to turn a dynamic process (verbs) into a static entity by re-categorization and thus provide a different way of construing the world, or of conceptualizing experiences from a different angle.

4. Conclusion

The current study examined nominalization use in a sample of applied linguistics and physics RAs. The higher frequency of nominalization in applied linguistics RAs was attributed to the more abstract nature of discourse in this field as an instance of soft fields and the tendency among writers to create abstraction by maintaining conciseness in their respective discourse. We, therefore, conjecture that the greater use of nominalization in applied linguistics RAs might reflect the greater degree of abstraction involved in this discipline. Results showed variation in using nominalization in various types of articles in applied linguistics. Moreover, the study suggested four pervasive patterns that mark disciplinary distinctions. That is, academic writers in applied linguistics tend to enhance the general volume of information into fewer words by deploying patterns 4 and 6, in which nominal structures are preceded by Deictic or employed without any premodifiers or postmodifiers to express generality in comparison to their counterparts in physics. However, to convey their scientific perspective, physics writers tend to increase the sophistication of the intended concepts through using more complex nominalization patterns 1 and 5.

The implications of this study are relevant to academic researchers. As the development of grammatical metaphor is a conscious design to create and control academic discourse in more technical terms in line with the current abundance of scientific, technical, and other academic advancements, the findings of the present study can equip academic writers with the required knowledge about the nominal patterns and dominant nominal expressions especially in these two fields of study. By incorporating these patterns, at least, researchers in these two disciplines will be able to condense several complex abstract ideas in a single clause, thus reducing the number of clauses in their writing and making the text more dense and formal. The findings of the study can also sensitize researchers interested in disciplinary studies to draw on disciplinary differences and open the path for more cross-disciplinary studies. Gaining insights into how scientific discourse is linguistically realized is of paramount importance since it allows for a better understanding of its discourse.

This study may provide additional insights for further research into nominalization. For instance, it would be fruitful that other contextual variables than those addressed in the current study such as native and non-native authors, novice and experienced authors also be taken into account for an in-depth study. Moreover, it is worth investigating whether the degree of abstraction involved in the topics discussed in a discipline relates to the degree of abstraction invoked by the use of nominalization. If so, researchers can then arrange disciplines on a continuum of abstraction with nominalization playing a pivotal role in this regard.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alireza Jalilifar

Alireza Jalilifar is professor of Applied Linguistics at Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran, where he teaches discourse analysis, applied linguistics and advanced research. His main research interests include second language writing, genre analysis, and academic discourse. Jalilifar has supervised more than 70 MA and 20 PhD theses in Iran. Most of these studies have had as their major goal a focus on diverse aspects of academic discourse including thematicity, lexical bundles, formulaic language, discourse markers, metadiscourse, and nominalization. In fact, my interest in nominalization took shape in 2015 and this led to the development of eight MA and PhD dissertations of which several joint papers results. The current study is an offshoot of a larger PhD study that was conducted aiming at investigating nominalization in various types of research articles across two disciplines with a reflection on expert and novice academic writing performances.

References

- Ahmad, J. (2012). Stylistic features of scientific English: A study of scientific research articles. English Language and Literature Studies, 2(1), 47–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5539/ells.v2n1p47

- Alfahad, A. (2015). Aggressiveness and deference in Arabic broadcast interviews. Journal of Pragmatics, 88, 58–72

- Alise, M. A. (2008). Disciplinary differences in preferred research methods: A comparison of groups in the Biglan classification scheme. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Louisiana State University, Louisiana.

- Árvay, A., & Tankó, G. (2004). A contrastive analysis of English and Hungarian theoretical research article introductions. IRAL - International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 42(1), 71–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2004.003

- Babaii, E., & Ansary, H. (2005). On the effect of disciplinary variation on transitivity: The case of academic book reviews. Asian EFL Journal, 7(3), 113–126.

- Banks, D. (2008). The development of scientific writing: Linguistic features and historical context. Equinox.

- Biber, D., & Gray, B. (2013). Nominalizing the verb phrase in academic science writing. In S. A. Tagliamonte, B. Aarts, J. Close, G. Leech, & S. A. Wallis (Eds.), The verb phrase in English: Investigating recent language change with corpora (pp. 99–132). Cambridge University Press.

- Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and language use. Cambridge University Press.

- Billig, M. (2008). The language of critical discourse analysis: The case of nominalization. Discourse & Society, 19(6), 783–800. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926508095894

- Bloor, T., & Bloor, M. (2004). The functional analysis of English: A Hallidayan approach. Arnold.

- Cameron, J. S. (2011). Comprehend to comprehension: Teaching nominalization to secondary ELD teachers. University of California, Davis.

- Charles, M. (2012). Proper vocabulary and juicy collocations: EAP students evaluate do-it-yourself corpus building. English for Specific Purposes, 31(2), 91–102.

- Coffin, C., Curry, M., Goodman, S., Hewings, A., Lillis, T., & Swann, J. (2003). Teaching academic writing: A tool kit for higher education. Routledge.

- Comrie, B., & Thompson, S. A. (2007). Lexical nominalization. In T. Shopen (Ed.), Language typology and syntactic description vol. III: Grammatical categories and the lexicon (pp. 334–381). Cambridge University Press.

- Don, Z. M., & Izadi, A. (2011). Relational connection and separation in Iranian dissertation defenses. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(15), 3782–3792.

- Eamegdool, S. S., Weible, M. W., Pham, B. T., Hawkett, B. S., Grieve, S. M., & Chan-ling, T. (2014). Ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle prelabelling of human neural precursor cells. Biomaterials, 35(21), 5549–5564

- Ezeifeka, C. R. (2014). Grammatical metaphor in SFL: A rhetorical resource for academic writing. Unizik Journal of Arts and Humanities, 12(1), 207–221.

- Fang, Z., & Schleppegrell, M. J. (2008). Reading in secondary content areas: A language-based pedagogy. The University of Michigan Press.

- Fatonah, F. (2014). Students’ understanding of the realization of nominalization in scientific text. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v4i1.602

- Galve, G. I. (1998). The textual interplay of grammatical metaphor on the nominalization occurring in written medical English. Journal of Pragmatics, 30(3), 363–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-2166(98)00002-2

- Glanzel, W., & Schubert, A. (2003). A new classification scheme of science fields and subfields designed for scientometric evaluation purposes. Scientometrics, 56(3), 357–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022378804087

- Hadidi, Y., & Raghami, A. (2012). A comparative study of ideational grammatical metaphor in business and political texts. International Journal of Linguistics, 4(2), 348–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v4i2.1853

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1994). An introduction to functional grammar. Edward Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1999). The language of early childhood. Continuum.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar. Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Martin, J. R. (1993). Writing science: Literacy and discursive power. The Falmer Press.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. M. (2004). An introduction to functional grammar. Arnold.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, M. I. M. (1999). Construing experience through meaning, a language based approach to cognition. Norfolk.

- Heyvaert, L. (2003). Nominalization as grammatical metaphor: On the need for a radically systemic and metafunctional approach. In S. Vandenberge, M. Taverniers, & J. Ravelli (Eds.), Grammatical metaphor: Views from systemic functional linguistics (pp. 65–99). Benjamins.

- Holmes, R. (1997). Genre analysis and the social sciences: An investigation of the structure of research article discussion sections in three disciplines. English for Specific Purposes, 16(4), 321–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(96)00038-5

- Holtz, M. (2009). Nominalization in scientific discourse: A corpus-based study of abstracts and research articles. In M. Mahlberg, V. González-Díaz, & C. Smith (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th Corpus Linguistics Conference Liverpool, UK. Retrieved from September 20, 2016 http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/publications/cl2009/

- Hu, G., & Cao, F. (2011). Hedging and boosting in abstracts of applied linguistics articles: A comparative study of English-and Chinese-medium journals. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(11), 2795–2809. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2011.04.007

- Hyland, K. (2001). Bringing in the reader: Addressee features in academic articles. Written Communication, 18(4), 549–574. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088301018004005

- Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge University Press.

- Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing. A&C Black.

- Hyland, K. (2006). Disciplinary differences: Language variation in academic discourses. In K. Hyland & M. Bondi (Eds.), Academic discourse across disciplines (pp. 17–45). Peter Lang.

- Hyland, K. (2009). Writing in the disciplines: Research evidence for specificity. Taiwan International ESP Journal, 1(1), 5–22.

- Hyland, K., & Diani, G. (Eds.). (2009). Academic evaluation: Review genres in university settings. Springer.

- Hyland, K., & Tse, P. (2007). Is there an academic vocabulary? TESOL Quarterly, 41(2), 235–253

- Jalilifar, A. (2012). Academic attribution: Citation analysis in master’s theses and research articles in applied linguistics. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 22(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2011.00291.x

- Jalilifar, A., Alipour, M., & Parsa, S. (2014). Comparative study of nominalization in applied linguistics and biology books. Research in Applied Linguistics, 5(1), 24–43.

- Jalilifar, A., Saleh, E., & Don, A. (2017a). Exploring nominalization in the introduction and method sections of applied linguistics research articles: A qualitative approach. Romanian Journal of English Studies, 14(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/rjes-2017-0009

- Jalilifar, A., White, P., & Malekizadeh, N. (2017b). Exploring nominalization in scientific textbooks: A cross-disciplinary study of hard and soft sciences. International Journal of English Studies, 17(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.6018/ijes/2017/2/272781

- Jalilifar, A., White, P., & Mehrabi, K. (2018). Investigating action nominalization in the introduction sections of research articles: A cross-disciplinary study of hard and soft sciences. Teaching English Language. (forthcoming).

- Khoobi, M., Delshad, T. M., Vosooghi, M., Alipour, M., Hamadi, H., Alipour, E., ... & Shafiee, A. (2015). Polyethyleneimine-modified superparamagnetic Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles: An efficient, reusable and water tolerance nanocatalyst. Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, 375, 217–226

- Lee, J. H., Park, N. G., & Shin, Y. J. (2011). Nano-grain SnO 2 electrodes for high conversion efficiency SnO 2–DSSC. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells, 95(1), 179–183

- Linfoot, C. L., Richardson, P., McCall, K. L., Durrant, J. R., Morandeira, A., & Robertson, N. (2011). A nickel-complex sensitiser for dye-sensitised solar cells. Solar Energy, 85(6), 1195–1203

- Lock, G. (1996). Functional English grammar: An introduction for second language teachers. Cambridge University Press.

- Mair, C., & Leech, G. (2006). Current changes in English syntax. In B. Aarts & M. April (Eds.), The handbook of English linguistics (pp. 318–342). Blackwell.

- Martin, J. R., & Rose, D. (2007). Working with discourse: Meaning beyond the clause. Continuum.

- Martı́n, P. M. (2003). A genre analysis of English and Spanish research paper abstracts in experimental social sciences. English for Specific Purposes, 22(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(01)00033-3

- McGrath, L., & Kuteeva, M. (2012). Stance and engagement in pure mathematics research articles: Linking discourse features to disciplinary practices. English for Specific Purposes, 31(3), 161–173

- Moltmann, F. (2007). Events, Tropes, and Truthmaking. Philosophical Studies, 134(3), 363–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-005-0898-4

- Montero, I., & Leon, O. G. (2007). A guide for naming research studies in Psychology. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 7(3), 847–862.

- Niu, C., Wang, Z., Lu, G., Krupka, T. M., Sun, Y., You, Y., ... & Zheng, Y. (2013). Doxorubicin loaded superparamagnetic PLGA-iron oxide multifunctional microbubbles for dual-mode US/MR imaging and therapy of metastasis in lymph nodes. Biomaterials, 34(9), 2307–2317.

- Noguchi, J. (2006). The science review article: An opportune genre in the construction of science (Vol. 17). Peter Lang.

- Oztürk, I. (2007). The textual organization of research article introductions in applied linguistics: Variability within a single discipline. English for Specific Purposes, 26(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2005.12.003

- Pho, P. D. (2008). Research article abstracts in applied linguistics and educational technology: A study of linguistic realizations of rhetorical structure and authorial stance. Discourse Studies, 10(2), 231–250. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445607087010

- Prasithrathsint, A. (2014). Nominalization as a marker of detachment and objectivity in Thai academic writing. Journal of Humanities, Special Issue, 20, 1–20.

- Pun, F. K., & Webster, J. (2009). Building of academic discourse in university students’ writing. ASFLA Conference: Practicing Theory: Expanding Understandings of Language, Literature and Literacy, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

- Ramanathan, V., & Kaplan, R. B. (2000). Genres, authors, discourse communities: Theory and application for (L1 and) L2 writing instructors. Journal of Second Language Writing, 9(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060-3743(00)00021-7

- Rathert, M., & Alexiadou, A. (Eds.). (2010). The semantics of nominalizations across languages and frameworks (Vol. 22). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Ruiying, Y., & Allison, D. (2003). Research articles in the applied linguistics: Moving from results to conclusions. English for Specific Purposes, 22(4), 365–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(02)00026-1

- Samar, R. G., & Talebzadeh, H. (2006). Professionals write like this: The case of ESP/EAP experimental research article abstracts. In First Post-Graduate Conference, University of Tehran, Iran.

- Samraj, B. (2002). Introductions in RAs: Variation across disciplines. English for Specific Purposes, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(00)00023-5

- Samraj, B. (2005). An exploration of a genre set: RA abstracts and introductions in two disciplines. English for Specific Purposes, 24(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2002.10.001

- Sheldon, E. (2011). Rhetorical differences in RA introductions written by English L1 and L2 and Castilian Spanish L1 writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10, 238–251.

- Skalicky, S., Berger, C. M., Bell, N. D. (2015). The functions of “just kidding” in American English. Journal of Pragmatics, 85, 18–31.

- Starfield, S. (2004). Word power: Negotiating success in a first-year sociology essay. In L. J. Ravelli & R. A. Ellis (Eds.), Analyzing academic writing: Contextualized framework (pp. 66–83). Continuum.

- Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English for academic and research settings. Cambridge University Press.

- Swales, J. M. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge University Press.

- Tabrizi, F., & Nabifar, N. (2013). A comparative study of ideational grammatical metaphor in health and political texts of English newspapers. Journal of Academic and Applied Studies, 3(1), 32–51.

- Tarone, E., Dwyer, S., Gillette, S., & Icke, V. (1998). On the use of the passive and active voice in astrophysics journal papers: With extensions to other languages and other fields. English for Specific Purposes, 17(1), 113–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(97)00032-X

- Taylor, C. (2015). Beyond sarcasm: The metalanguage and structures of mock politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 87, 127–141

- Thompson, J. (2004). Introducing functional grammar. Arnold.

- Valipouri, L., & Nassaji, H. (2013). A corpus-based study of academic vocabulary in chemistry research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12, 248–263

- Vu Thi, M. (2012). Grammatical metaphor in English pharmaceutical discourse. Unpublished MA thesis. Vietnam National University: Vietnam.

- Wenyan, G. (2012). Nominalization in medical papers: A comparative study. Studies in Literature and Language, 4(1), 86–93.

- Zucchi, A. (1993). The language of propositions and events. Issues in the syntax and semantics of nominalization. Kluwer.