Abstract

This study was conducted to evaluate a potential new way of assessing reading comprehension at the college level in Afghanistan. In this study, synthesis writing is evaluated to determine if reading-writing integration can help in assessing the reading comprehension of Afghan sophomore students. Furthermore, a gap-filling activity was used to examine if a cognitively less challenging activity can provide support (scaffolding) in completing a more complex task. Participants were divided into two groups. Gap-filling and reading-to-write-a-synthesis activities were presented in reverse order to the groups. A 2-by-2 mixed ANOVA was conducted to assess the main effects of task and group and the interaction effect between the two factors. Results of the study suggest that order of presentation affects the performance of participants in these two tests and, contrary to expectations, presenting the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity prior to the gap-filling activity may result in better performance on the more challenging reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Assessing reading comprehension is one of the most challenging tasks for language instructors. In EFL (English as a Foreign Language) contexts, language teachers often opt for traditional reading assessment methods. This research article explores reading comprehension of the intermediate level EFL students. The findings of this study will help EFL language instructors and curriculum developers to bring modification in the way reading assessment is approached. The intent of this study is to promote reading-writing integration and synthesis writing in assessing reading comprehension, which would also help students in their future academic endeavors. The findings imply that students at this university require extensive support in the form of instruction in developing critical thinking skills and in synthesizing information from multiple sources to successfully implemented reading writing integration in assessing reading comprehension.

1. Introduction

Language assessment has changed drastically over time; modern methods for assessing language skills are replacing old methods and approaches. However, test developers have always considered the importance of each individual test item and whether it assesses the language skill or sub-skill it was initially designed to assess. Test-developing companies invest considerable financial resources in ensuring that test items are valid and reliable. Standardized testing companies such as ETS (Educational Testing Service) and its well-established standardized proficiency test, TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language), assesses language proficiency through multiple-choice items for reading and listening skills. Often, decisions regarding students’ futures are made based on the results of such high-stakes standardized tests.

In Afghanistan, over the last decade, efforts has been made to bring changes to the way English language is assessed. All the higher education institutions follow the curriculum set by the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) of Afghanistan. The current curriculum implemented in higher education institutions require both formative and summative assessments (Noori et al., Citation2017). Moreover, Basheer and Naeem (Citation2015) believe that English language testing has evolved in Afghanistan. According to them, behaviorist approach is giving way to more of cognitive and constructivist approach. Therefore, the language teachers are encouraged to emphasize more on assessment for learning rather than the assessment of learning” (p. 131).

Reading assessment can be intimidating and daunting for teachers and challenging for test developers; there is no single technique for developing test items that would provide information on all the relevant aspects of reading abilities. Any language assessment technique will have its limitations and advantages; therefore, it is best that teachers and test developers seek to use multiple methods and techniques. Moreover, the claims and conclusions drawn from test results should be modest (Alderson, Citation2000). Deciding to use a particular test type needs to be contingent on the goals and objectives of giving the test. In ideal circumstances, test items are designed, taking into consideration which aspects of language are targeted for assessment. If carefully designed, a range of test tasks can be used to assess reading comprehension. When a test with a gap-filling task, for example, is well-constructed, it can help in assessing students’ ability to identify main ideas and details, their comprehension ability, and even their ability to synthesize information from multiple sources.

Test developers need to ensure that the test items that they design capture students’ reading comprehension ability. For more challenging reading skills, such as reading to integrate information or summarize, it is important that students are provided with opportunities to demonstrate understanding. In EFL (English as a Foreign Language) or ESL (English as a Second Language) contexts, reading comprehension is usually measured through objective test items such as gap-fills, true/false, and multiple-choice; sometimes, a few performance-test items are included. Performance items, as defined by Miller et al. (Citation2009), require students to produce responses (e.g., write an essay, complete a task, give a speech). Teachers and test developers usually rely on objective test items, which, as explained by Miller et al. (Citation2009), are highly structured and demand the selection of (a) one or two words or (b) the right answer from alternatives, of which only one is a correct response.

Trites and McGroarty (Citation2005) believe that reading to synthesize requires readers to use “sophisticated discourse processes and critical thinking skills” (p. 199). Therefore, when learners engage in synthesis activities, their cognitive and critical thinking skills develop. By integrating writing activities into the assessment of reading comprehension, the reader becomes engaged in more complicated cognitive processes such as inferring from the text, putting information from the text(s) together to write a synthesis, comparing or contrasting ideas, or taking a stance. According to Trites and McGroarty (Citation2005), in completing synthesis essays, students are engaged in more complex cognitive processes such as inferring from the reading texts, putting information from multiple sources together, comparing and contrasting, or taking a stance. Therefore, the lower the reading ability of the reader is, the weaker they are in synthesizing information. When students write a synthesis essay or a summary of the material that they have read, they are provided with more opportunities to demonstrate comprehension and creativity. When the students’ level is not advanced, they struggle in completing performance assessment activities.

In this study, I aim to find out the degree to which synthesis writing can help in assessing reading comprehension. I also explore the incorporation of other reading comprehension assessment approaches such as reading to integrate information in an essay format may reveal students’ reading comprehension. Furthermore, I have also explored how information about reading proficiency obtained from synthesis writing may be similar to or different from information obtained from a classic gap-filling task and whether the order in which the tasks are administered makes a difference. Reading to integrate or reading to synthesize information is a new approach for assessing reading comprehension in the Afghan context; however, gap-filling is the most frequently used way of assessing reading comprehension.

2. Literature review

2.1. Comparing L1 (first language) and L2 (second language) reading assessment

There is a considerable amount of research on L1 reading comprehension. L1 research studies have investigated reading abilities and reading comprehension of readers ranging from 3 years of age to the university level. However, research on L2 comprehension is more complex in comparison to that of L1 reading comprehension because L2 students have a wide range of language proficiencies (Grabe & Stoller, Citation2011) and unevenly distributed gaps in their proficiency. Therefore, carrying out large-scale studies of L2 comprehension is more complex.

Grabe and Stoller (Citation2011) identify a number of individual and experiential differences between L1 and L2 reading. These differences include factors that influence L2 reading, for example, the students’ literacy level in their L1, their previous involvement in L2 reading, their level of motivation with regard to their L1 and L2 reading comprehension, their experiences with and training in reading authentic materials, and their attitudes towards them. Dronjic and Bitan (Citation2016) also provide insights into the cognitive basis of reading and the differences between an individuals’ reading ability in their L1 and L2. According to Dronjic and Bitan, these differences depend on the ways in which the human brain processes orthographies and the effects that they have on L1 and L2 reading. These differences also depend on the proficiency of the individual in their L2. Another important factor that influences reading abilities is the degree to which the L1 phonology and/or orthography interacts with the L2. Hedgcock and Ferris (Citation2009) provide reasons for developing a workable reading assessment plan that measures students’ L2 reading performance in relation to the goals and content of well-recognized curricula. These reasons serve as guidelines that test developers can use to design items that would efficiently assess students’ L2 reading performance. However, designing items that effectively assess the intended aspect of reading comprehension is a challenging process, which has undergone a great deal of change over time.

3. Reading assessment over time

Reading comprehension assessment has evolved through time. In looking at the way reading comprehension was assessed in the past, scholars have adapted and criticized different methods and built on them to come up with new methods and strategies to help individuals better demonstrate their comprehension of the material that they have read. According to Taylor (Citation2013), before the 1960s, there was no precise formulaic way of testing reading comprehension. But in the 1960s, reading was recognized as a sub-skill of language development, and tests were designed to assess this sub-skill. However, Taylor (Citation2013) believed that year 1975 marked the beginning of a new approach to assess reading comprehension; according to him, 1975 signifies the emergence of reading comprehension as an individual measurable skill rather than a skill that needed to be integrated with translation, reading aloud, and summary writing for adequate assessment.

Since the 1970s, test developers in various parts of the world have attempted to design activities that precisely test reading comprehension. Depending on the purpose of the reading assessment, a test is designed to assess readers’ general reading abilities or their academic or professional reading abilities (Taylor, Citation2013). Over time, test designers have developed multiple task types to assess reading comprehension including multiple choice, true/false, matching, sentence completion, short-answer questions, and information transfer activities. These tasks can be divided into two distinct formats. The first is the select response format, where test takers select a correct answer among available options. For example, multiple-choice, sentence completion, true/false, and information transfer fall into this category. The second format, called the construct response format, is when test takers produce a written answer themselves. Test-taker responses are usually in the form of summary writing, synthesis writing, and other types of writing. It was not until the 1970s that items were commonly designed to give test takers the opportunity to produce written answers and demonstrate their understanding of the material in a more productive way. However, there are advantages and limitations to both formats.

Similarly, performance assessment has advantages and limitations. Performance assessment, as the name implies, provides students with ample opportunities to construct responses; this assessment format assesses students’ ability to think critically, synthesize and integrate information, and solve problems. Performance assessment also minimizes guessing, and test developers need only a few items to assess students’ performance. Students also have the freedom to demonstrate their creativity, as this type of assessment emphasizes originality. On the other hand, the performance assessment format has limitations. These assessment items are inappropriate for measuring the knowledge of facts, they are time-consuming to score, and because scoring is not objective, scores can be inconsistent.

Since the 1980s, tasks that were used to assess reading ability were designed in the select response format. One activity that became very prominent was reading to fill in the gaps; therefore, it is important to examine this activity type more closely. As the goal of this thesis is to examine the usefulness of the select response format and the construct response format in one specific instructional and assessment context, an example of one construct response format, reading-writing integration, is also discussed in more detail.

4. Reading to fill in the gaps

There is no simple answer when it comes to deciding on the type of test to use for measuring reading comprehension. However, activities like gap-filling can be designed to help in demonstrating students’ comprehension and inferencing abilities based on information given in the text. In a study by Yamashita (Citation2003), it was found that gap-filling is an appropriate measure to assess students’ reading comprehension because gap-filling tests assess students’ text-level knowledge; it can also help in distinguishing between skilled and less skilled readers. It is important to note that there should be a distinction between gap-filling and cloze activities. According to Alderson (Citation2000), gap-filling activities are designed with a rationale for deleting words; however, cloze activities have a fixed ratio for deleting words in a text. In cloze activities, there is systematic word deletion in the text. Grabe (Citation2009a) warns that cloze tests “are not automatically valid assessments of reading abilities, particularly when students are expected to write in the missing words. Such tests become production measures and are not appropriate for L2 reading assessment” (p. 359), while in gap-filling activities, there is no systematic word-deletion process, which makes them much more useful indicators of reading comprehension. Alderson (Citation2000) also claims that gap-filling activities can be used to assess reading comprehension, but cloze tests cannot provide information about the reading comprehension of the test-takers. A study by Jonz (Citation1987) on gap-filling and cloze activities suggests that gap-filling activities are more challenging than cloze activities. He found that for gap-filling activities, test-takers needed to know the context to process semantic and linguistic information to score high. But for cloze activities, test takers were not required to understand the context; they could fill in the blanks using local clues.

Gap-filling activities help teachers diagnose and target specific types of language items; such activities can reveal to the teacher if students are struggling with a certain aspect of language, such as parts of speech or with the comprehension of the text, these activities also help in differentiating between skilled or less skilled readers (Yamashita, Citation2003). Cloze tests, on the other hand, can only provide information about students’ ability to recognize and respond to local syntactic constraints (Alderson, Citation1979). Hedgcock and Ferris (Citation2009) claim that implications drawn from cloze tasks are limited because these tasks do not provide extensive information on students’ comprehension of the text. Hedgcock and Ferris assert that cloze tasks only provide information that is fundamentally word-based. However, the effectiveness and the degree to which gap-filling and cloze tests reveal test takers’ reading comprehension depend on how carefully the items are designed. The purpose behind designing gap-filling activities varies. These activities can be designed to assess basic reading comprehension, or they can be designed to assess a reader’s ability to infer, synthesize information, identify main ideas or details, and compare or contrast information. These activities are most effective in assessing reading abilities when students are asked to fill in words that they have already encountered in the text or that they already know (Grabe, Citation2009a).

5. Reading–writing integration

There has been a tendency, among test developers to integrate writing in assessing reading comprehension either in the form of writing summaries, essays, or reading-to-write-a-synthesis. Perfetti et al. (Citation1999; see also Zhang, Citation2013) defined reading to integrate information as a process during which learners synthesize information from multiple sources and compile information from various parts of an extended text, for example, bringing together complex and lengthy information from a chapter in a textbook.

Although reading-writing integration in assessment seems contradictory to the original goal of assessing reading as an individual skill, over time, it has become clear that reading and writing are overlapping skills. Shanahan and Lomax (Citation1986; see also Grabe & Zhang, Citation2016) proposed three reading-writing theoretical models; through these models, they explained the complex relationship between reading and writing. They found that reading influences writing development and writing skill effects reading development. Grabe and Zhang (Citation2016) provide an overview of the historical development of the reading-writing relationship; they report that the reading-writing relationship is complex and bidirectional, and that the development of one skill will result in the development of the other skill as well.

Reading to complete a writing task can be more challenging than reading for basic comprehension tasks, depending on the nature of the writing task. Tasks such as reading-to-write-a-synthesis essay are more challenging than, for example, writing short responses. In a study of Korean EFL learners by Brutt-Griffler and Cho (Citation2015), it was found that students struggled with integrating information from multiple sources and that they required more instruction and practice in integrating information from the texts they read into their writing. Trites and McGroarty (Citation2005) claim that scanning to find specific information and reading for basic comprehension of a text are easier in comparison to reading to synthesize information from texts. Zhang (Citation2013) states that synthesizing information is challenging because when students are engaged in synthesizing information from multiple sources, they are using their reading, writing, and critical thinking abilities.

Scaffolding is defined as providing assistance to learners in completing a task that they could not complete on their own (Graves & Graves, Citation2003). Scaffolding also helps learners to complete tasks in less time and in a better manner; scaffolding also provides support for better learning. The concept of scaffolding is taken from Vygotsky’s social constructivist view of learning. Vygotsky (Citation1978) stated that language develops via social interaction; he called this collaboration the zone of proximal development. The zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the difference between what a child can achieve alone and what he/she can achieve with the help of the adult teacher/parent or more skilled peer.

Reading to integrate, often referred to as reading-to-write-a-synthesis, is different from summary writing. In synthesis writing, the reader/writer must organize textual information in their own frame, different from the information provided in the source texts (Grabe, Citation2009a). When writing a synthesis, the reader goes beyond basic comprehension of the material. As part of the synthesis, according to Grabe and Zhang (Citation2013), the writer synthesizes information, infers, draws conclusions, compares and/or contrasts across texts, and forms arguments.

6. Research question(s)

This experimental study aims to investigate the following research questions:

How appropriate is reading-to-write-a-synthesis assessment for upper-intermediate students of the English language?

How appropriate is a gap-filling activity for assessing the reading comprehension of the upper-intermediate students of the English language?

How does the order of presenting the tests affect students’ performance?

7. Methodology

7.1. Participants

This experimental study focused on sophomore students in the English Department of Herat University. A total of 54 Afghan sophomore students volunteered to participate in the study. Their level of English proficiency is considered to be intermediate (band B1). This estimation is made based on the level of the textbooks taught in their current courses. Data gathered through a demographic survey show that there were 37 female and 17 male participants; 54 of them were Persian speakers (Dari) while 3 did not answer the question about their native language. They all started studying English in the fourth grade, which suggests 9 years of instruction in English; most of them attended private English classes as well. After a national placement test, which tests all the subjects taught at school except English, they entered the university. At the university, the participants had three courses of reading comprehension and at least one course of writing composition and grammar for writing. Participants had completed three semesters of reading courses and used Interaction 1 and 2 (Kirn & Hartmann, Citation2002, Citation2006) in their first year. In their most recent reading course, they studied Mosaic 1 (Wegmann & Knezevic, Citation2001). The objective of the reading courses, as specified by the department curriculum, is to help students with reading comprehension of academic texts.

8. Data collection instruments

Six different instruments were developed for the study. The first instrument was a demographic survey (see Appendix 1A), which was developed to ascertain the characteristics of the target participants such as their gender, language background, comfort level in reading and writing in English, and their percentage of reading and writing per week in English. The reading-to-write-a-synthesis prompt was the second instrument of the study (see Appendix 1B). The prompt required participants to refer to the two texts and compose an essay on the similarities and differences between the two types of pollution. They were also asked to indicate which type of pollution was a concern for their community or country; they were directed to build their opinion based on the information and details given in the texts.

A gap-filling task was the third instrument (1 C) used in the study. The same texts assigned for the reading-to-write-a-synthesis task were used for the gap-filling task. A 15-item gap-filling activity was designed. The first 10 items were created to check comprehension of both reading passages simultaneously. The last five items were synthesis statements. There were 11 sentences with multiple blank spaces; there were exactly 3 sentences with a single-blank space, and there was one multiple-choice item included in this activity.

The fourth instrument comprised two reading texts (see Appendix 1D). These were composed of 700 words each. The texts were carefully selected after going through several processes. Initially, texts were selected on the basis of topics with opposing points of view. Five textbooks were selected for review. Eighteen texts from these textbooks were typed and two readability tests (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Flesch Reading Ease) was used to determine the word count, average word count per sentence/paragraph, and readability of each text. The criteria for selection were (a) the topic of the text and (b) the results of the readability test. Texts were rejected when the topic was too controversial, irrelevant to potential participants, or gender-biased. For example, topics such as terrorism or studies of cybercrime were rejected because they did not meet the above-mentioned criteria.

The fifth instrument was a scoring rubric for the synthesis essay (see Appendix 1E), which was adapted from Trites and McGroarty (Citation2005). Finally, the sixth instrument entailed the answer key for the gap-filling activity (see Appendix 1 F).

9. Data collection procedures

Sophomore students volunteered to participate in the study. They were randomly divided into two groups (Group A and Group B) using the class roster. Their seating was arranged so that no two students from the same group would be seated next to each other. Their seating arrangement was A-B-A-B-A.

Both groups received material packets that included the two reading texts, instructions for reading-to-write a synthesis (printed on yellow paper), the gap-filling activity with instructions (printed on blue paper), an informed consent form, and a demographic survey. All material packets were marked with a code (different for each student) and the participant’s group (Group A or Group B).

All participants first read, signed, and agreed to participate voluntarily in the study. After they agreed to participate in the study, they were asked to complete the demographic survey (see Appendix 1A). They were given 5 minutes to complete the survey. A local administrator (with whom the researcher was in close contact) explained the process of data collection to the participants and, in order to complete the process, each student needed to complete both timed tasks.

To start the process, all groups were asked to read both texts. They were given 15 minutes to read, annotate, take notes, and highlight the parts of the texts they considered important. At the beginning of both tasks, participants were asked to copy the code from the back of the material packet on the top right corner of all materials.

Next, Group A was asked to start Task 1, which was the reading-to-write a synthesis activity, and Group B was asked to start with the gap-filling activity. Both groups had 30 minutes to complete Task 1. In the reading-to-write a synthesis activity, participants were required to compose an essay on the similarities and differences of the two types of pollution. They were also asked to indicate which type of pollution was a concern for their community or country; they could form their opinion based on the information and details given in the texts. They could also refer back to the texts if they wanted to reread or to look for any details they needed to build their argument. Group B, on the other hand, began Task 1 by completing the gap-filling activity. During the gap-filling activity, they could also go back to the texts, reread them, and look for any information that they needed to fill in the gaps in the statements. After 30 minutes, both groups were asked to stop working on Task 1 and place the material for Task 1 back in the materials packet.

In Task 2, Group A was asked to complete the gap-filling activity and Group B was asked to complete the reading-to-write a synthesis activity. For Task 2, participants were again given 30 minutes to complete the task. Participants completing the activities could refer to texts at any point. After 30 minutes, the administrator asked both groups to stop working on the activities and place all the materials back into the materials packet.

10. Pilot study

This experimental pilot study focused on three different participant groups: a group of 4 native English speakers and a group of 6 sophomore Afghan students from the English Department of Herat University, Afghanistan. The participants had differing levels of English proficiency.

The first four participants of the study were native speakers of English. Among them, there were 3 female participants and 1 male participant. They were all first-year MA Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) students at Northern Arizona University. This group was included in the pilot study to provide a baseline for the study; after taking the tests (reading-to-write-a-synthesis and gap-filling), the participants were asked for feedback on and comments about the test items, whether they felt the time they were given to complete the tests was sufficient or if they needed more or less time; they were also asked about the clarity of the instructions for the tests and if they felt the wording was confusing, clear, or needed revision.

Sophomore students from the English Department of Herat University constituted the second participant group of the study. There were 3 female and 3 male participants. They all started studying English in the fourth grade of school. In total, they had at least 9 years of instruction in English. Most of them attended private English classes as well. After a national placement test, which tests all the subjects taught at school except English, they entered the university. At the university, they had taken three English courses of reading comprehension, at least one course of writing composition, and one course on grammar and writing. The pilot study enabled me to find and correct problems with the materials and procedures. Things I learnt from this pilot study that were changed for the larger scale study include the following:

The texts used for the pilot study were too lengthy; by cutting down the length of the texts, it would be possible to assess participants’ ability to synthesize the information presented in the texts while spending less time on the activity.

I changed some items in the gap filling activity to create a balance in the items with regard to the number of items assessing participants’ ability in (a) identifying main ideas and details and (b) synthesizing information. To respond to the limitations revealed in the pilot, the instruments was changed to include 5 main idea items for the Air Pollution passage, 5 main idea and details items for the Garbage passage, and the final 5 items were rewritten to find out if participants can synthesize information in both passages or not

I also learnt that the instructions for the reading-to-write-a-synthesis were not explicit enough, which caused confusion for the participants from Herat University, Afghanistan. Therefore, I revised the prompt with more elaborate and more explicit instructions to solve this problem.

It was decided that in the full-scale study, participants would take both tests (Reading-to-write-a-synthesis and Gap-Filling), but in a different order. The plan was to divide all the participants into two random groups and present the tests in two orders to find out whether the order of presentation, gap-filling before synthesis or synthesis before gap-filling, results in better performance or not.

I also adapted the scoring rubric for the Reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity. It was decided that there would be points allocated for the organization and format of the synthesis essay unlike the rubric used by Trites and McGroarty (Citation2005). The rubric that was used by Trites and McGroarty only focused on participants’ ability to integrate ideas from two texts without looking at the organization or format of the synthesis essay.

11. Data analysis

In this study, the independent variables were the type of reading comprehension test (a within-participants factor) and the order in which the tests were completed by the participants (a between-participants factor). There were two types of test, reading-to-write-a-synthesis (RWS) and gap-filling (GF), and the outcomes of these tests were measured through the scores the participants received on the tests. So, the range of possible scores for gap-filling was a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 40 while the range of scores for reading-to-write synthesis was a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 25. As described above, the two groups of participants differed in the order in which they completed the two tests. To analyze the data collected in this study, a 2-by-2 mixed ANOVA was used. Post-hoc t-tests with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha levels were conducted to determine the significance of individual contrasts. Spearman rho correlations were also calculated to find the inter-rater reliability for the reading-to-write a synthesis activity. The Spearman correlation was used due to the fact that the data were ordinal in nature.

12. Results and discussion

12.1. Item analysis for the gap-filling task

Test items in the gap-filling task were analyzed, and it was found that the item facility (the proportion of students who answered a particular item correctly) for all the items was positive; there was a balance between difficult, moderate, and easy questions. There were 13 intermediate items (range between 0.3 to 0.7), 8 difficult items (range lower than 0.3), and 19 easy items (range higher than 0.7) in the test. The discrimination power of the items was also analyzed. Item discrimination refers to the degree to which students with high overall exam scores also got a particular item correct (Miller et al., Citation2009). There were only 3 items out of 40 with negative discrimination values, indicating that, on these items, participants with lower overall scores outperformed participants with higher overall scores. There were also 7 items with discrimination power of less than 0.3; the other 30 items ranged from 0.3 to 0.89, which indicates that these items were successful in discriminating between participants with different levels of reading comprehension ability as indicated by the gap-filling task. KR-21 was used to estimate the reliability of the gap-filling task. The KR-21 statistic was r = 0.85, indicating high reliability. presents descriptive statistics for the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity:

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for the Reading-to-Write-a-Synthesis Activity

Total Possible score for RWS = 25

In reading-to-write-a-synthesis, there were 54 participants, 27 participants were assigned to Group A, where participants completed reading-to-write-a-synthesis before gap-filling, and 27 participants were assigned to Group B, where participants completed gap-filling before reading-to-write-a-synthesis. presents the descriptive statistics for the gap-filling activity.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for the Gap-Filling Activity

Total possible score for GF = 40

To find out how participants performed in the reading-to-write-a-synthesis and gap-filling activities, a 2-by-2 mixed ANOVA with the factors “test” (2 levels: gap-filling, and reading-to-write-a-synthesis) and “group” (2 levels: Group A completed reading-to-write-a-synthesis before gap-filling; Group B completed gap-filling before reading-to-write-a-synthesis) was conducted to assess the main effects of task and group and the interaction effect between the two factors. The ANOVA was performed on logit-transformed proportions.

In order to find out the outliers in the data, an outlier analysis was run to see whether any outliers were skewing the data and therefore reducing the power of the independent t-test to detect differences between reading-to-write-a-synthesis scores for the two groups. Two outliers were identified. They were removed from the analysis, and the entire analysis was rerun. However, this did not alter the pattern of results. Therefore, the results are reported for the entire (unreduced) sample.

The Shapiro-Wilk test of normality was run on the data in each of the four cells of the factorial design and did not indicate any departures from normality. Levene’s test of equality of variances indicated that the variances were equal. The results of the 2-by-2 mixed ANOVA indicated that the main effect of group was not significant. The main effect of test was significant, F (1, 52) = 6.24, p = .02, ηp2 = .11, and there was a significant interaction between group and test, F(1,52) = 10.31, p = .002, ηp2 = .16. Figure 5.1 summarizes this pattern of results:

Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc tests indicated that, in Group A, who completed the gap-filling task before the reading-to-write-a-synthesis task, the scores on gap-filling were higher than the scores on reading-to-write-a-synthesis, t(26) = 3.64, p = .001, with a medium effect size, d = .50. In Group B, where students completed the reading-to-write-a-synthesis task before the gap-filling, the scores on the two tasks did not exhibit a statistically significant difference. Moreover, the reading-to-write-a-synthesis scores tended to be higher for Group B than for Group A, although this contrast only approached significance after the Bonferroni correction had been applied, t(52) = 2.05, p = .05, with a medium effect size, d = .54. There were no differences between the two groups’ gap-filling scores.

13. General discussion and conclusion

i. How appropriate is a reading-to-write-a-synthesis assessment for Afghan students of the English language?

The results of the students’ reading-to-write-a-synthesis essays indicate that reading-to-write-a-synthesis is a challenging activity. The essays they composed to synthesize the information from the two texts were scored based on a rubric (see Appendix 4E) that was designed to evaluate (a) the integration of information from multiple sources, (b) the use of relevant details, and (c) the organization and language use. Participants’ performance in this activity indicated that they had little or no experience in integrating information and forming an opinion based on the ideas presented in the two reading texts. As results indicate, the mean score for reading-to-write-a-synthesis in Group A was 35.8 % and in Group B, it was 48.3%. The overall performance was low which implies that participants had a difficult time completing this activity that require the critical thinking inherent in synthesis tasks. Therefore, it can be concluded that participants lack sufficient instruction in reading, writing, and completing activities that require critical thinking.

ii. How appropriate is a gap-filling activity for assessing the reading comprehension of Afghan students?

Participants also completed a gap-filling activity where they were asked to fill in the blank spaces using the words and phrases that would complete a main idea, a specific detail, and words and phrases that synthesize information presented in the two reading texts. As mentioned earlier, participants were divided into two groups; in Group A, they first completed the gap-filling activity and then the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity and in Group B, the order of the tests was reversed. The results for gap-filling suggest that gap-filling was relatively an easier activity in comparison to reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity. Participants in Group A got 50.4% and participants in Group B got 46.8% on the gap-filling activity. Scores in the gap-filling activity were low.

14. Iii. How does the order of presenting the tests affect students’ performance?

As mentioned earlier, participants were divided in two groups to manipulate the order of presenting the tests to find out whether presenting the gap-filling activity first would result in better performance on the more challenging activity, reading-to-write-a-synthesis. The results for reading-to-write-a-synthesis and gap-filling tests show that when students completed gap-filling before reading-to-write-a-synthesis, the scores on reading-to-write-a-synthesis were significantly lower. However, when the order of the tasks was reversed, and participants completed reading-to-write-a-synthesis before gap-filling, the scores on reading-to-write-a-synthesis were much higher in comparison to the other group. In Group A, the mean score for reading-to-write-a-synthesis was 35.8 % and in Group B, it was 48.3%. The scores on the gap-filling activity were unaffected by the order of presentation.

15. Interpretation of the results

This study was conducted to find out if synthesis-writing is an appropriate measure for assessing the reading comprehension of Afghan sophomore students in the English Department at Herat University. Since reading to synthesize was a new activity for the target participants, a more familiar activity, gap-filling, was designed to help prepare students for the more challenging activity; as gap-filling was designed to help participants identify the main ideas, details, definitions, and make inferences from the two reading texts. Faraj (Citation2015) and Vonna et al. (Citation2015) claim that scaffolding techniques significantly improve students’ writing skills. Therefore, gap-filling activity was expected to scaffold participants to perform better in the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity. In order to test this with the target population, Group A completed the gap-filling before reading-to-write-a-synthesis, and Group B completed the tasks in reverse order.

As mentioned earlier, the manipulation of the order of presentation of the task did not help in producing better results in reading-to-write-a-synthesis; on the contrary, the scores dropped significantly when the activity was scaffolded. There may be several reasons for this: it could be due to the unfamiliarity of the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity or the lack of instruction and practice in integrating and synthesizing information from multiple sources. According to Zhang (Citation2013), instruction plays an important role in developing the synthesis writing skills of the language learners. It could also be also due to the fact that the guiding questions in the prompt for reading-to-write-a-synthesis essay were limiting to just answering the questions, and/or it could be simply due to participants’ fatigue after completing several tasks before getting to write their synthesis essay.

Afghan students had not had practice and instruction in how to integrate information from multiple sources to compose an essay based on information from multiple sources. According to Numrich and Kennedy (Citation2017), learners require guided practice in reviewing materials, highlighting and paraphrasing key points, and organizing the material into a synthesis essay. Therefore, the unfamiliarity and lack of practice with the type of activity could have resulted in the low overall scores. In order to write a better synthesis essay, students will need instruction on identifying the main ideas from multiple sources, connecting them together, and forming opinions based on the information presented in the reading texts; that is why Hirvela (Citation2004) believes integrating information from multiple sources is more challenging because in order to do this successfully, students need to be able to (a) find and identify relevant information and to (b) put it together in their written work and then (c) assess it critically. Therefore, students need to be instructed, and they should be provided with enough opportunities to practice integrating information from multiple sources and forming opinions based on them if this type of assessment is to be used.

The reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity was designed such that participants were provided with guiding questions to help them organize the structure of their essay in a meaningful and systematic way. These questions not only required participants to find the main ideas and integrate them, but also were designed to tap into their critical thinking abilities and guide them in forming opinions or presenting a case based on the information in the readings. According to Grabe and Zhang (Citation2013), when writing a synthesis, the reader goes beyond basic comprehension of the material. As part of the synthesis, the writer synthesizes information, infers, draws conclusions, compares and/or contrasts across texts, and forms arguments. However, participants simply read the texts and answered the questions based on the information presented in the readings without putting the information together or synthesizing ideas. Therefore, the way these guiding questions were presented may have limited students’ ability to finding specific details; thus, resulted in an essay that presents answers to the series of questions intended to guide the structure of the essay.

Another reason for the low scores in the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity, after providing scaffolding through the gap-filling activity, could be simply due to fatigue. Participants were required to complete a series of tasks before writing their synthesis essay. They had to read and sign the consent form, complete a demographic survey, read two texts of 593 words each, fill in the gaps in the gap-filling activity, and then write their synthesis essay. However, this is also true for the gap-filling activity when completed after the reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity, yet performance on the gap-filling task did not suffer significantly.

16. Conclusion

This study was intended to find out the reading and writing relationship in assessing reading comprehension of the Afghan EFL learners. Students were randomly divided into two groups where they had to complete a synthesis and a gap-filling activity, Group A completed the activities in the reverse order of the Group B. These activities were designed to assess the reading comprehension of the language learners. Results of the study suggest that reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity was cognitively demanding for the students to complete; moreover, gap-filling activity did not provide significant support to prepare learners for a more challenging activity.

17. Implications for instruction and assessment practices

This study was conducted to explore one possible way of modifying the way reading comprehension is assessed in the English Department at Herat University. A reading-to-write-a-synthesis activity was used to assess reading comprehension; the task required complex cognitive skills to complete. However, the results indicate that there were other issues with this assessment type, particularly when students were provided with what was meant to function as a scaffolding activity. The results of the study help us identify ways that can inform teaching and assessing reading in the English Department at Herat University. The intended use for reading-to-write-a-synthesis was measuring the reading comprehension of students in the classroom context.

Grabe and Zhang (Citation2013) highlighted several studies that emphasized the development of reading comprehension skills. The authors state that in order for students to perform better on reading and writing tasks, it is important to develop their reading abilities. The results of this study show that reading-to-write-a-synthesis is a challenging activity and therefore, students require instruction and practice in completing such activities. The psychological theory of transfer-appropriate processing suggests that to be tested a certain way, students need practice with that exact activity (Morris et al., Citation1977). Therefore, teachers need to provide detailed instruction on identifying main ideas from multiple sources, connecting ideas together, and forming opinions based on readings. Students require sufficient practice and opportunities for repeating such activities to learn how to integrate information from various sources to compose a synthesis essay.

18. Future directions for research and concluding remarks

This study helped us identify and suggest a reading comprehension assessment type that would facilitate reading assessment in a more reliable and effective manner in the English Department at Herat University. However, there are areas that can be improved upon if similar studies are carried out in the future. Some of the issues highlighted in this study as well as the limitations of the study could be considered future avenues for research. It is mentioned earlier that the participants in this study did not have prior experience with activities that require the integration of ideas from multiple sources and critical commentary. It would be worth looking at the following areas in future studies:

How much practice and instruction on synthesizing information from multiple sources would be sufficient?

Would this study have yielded different results if instruction on reading-writing integration had been provided to the participants?

How effective would various objective tests be (e.g., true/false, multiple-choice) when used as scaffolding activities for more complex reading activities?

The prompt for reading-to-write-a-synthesis was found to be misleading for some students. Synthesis essays suggested that the guiding questions limited the students; therefore, for future studies, it would be important to format the prompt to direct students to write an essay instead of simply answering the guiding questions. This can be done by limiting the number of guiding questions or by not adding comprehension check questions.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shagofah Noor

Shagofah Noor completed her degree in Teaching English as a Second Language (TESL) from Northern Arizona University in 2018 through Fulbright scholarship. She has been teaching English major undergraduates at Herat University, Afghanistan, for last eight years. She has carried out multiple research projects, most of which were published locally. She is interested in exploring reading and speaking skills, and she is inclined towards studying pragmatics as well. Therefore, the current research project is aligned with the previous research projects.

References

- Alderson, J. C. (1979). The cloze procedure and proficiency in English as a foreign language. TESOL Quarterly, 13(2), 219–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3586211

- Alderson, J. C. (2000). Assessing reading. Cambridge University Press.

- Basheer, A., & Naeem, A. (2015). Teachers’ perceptions about constructivist learning in Afghan Schools.: Mathematics teachers’ perceptions and usage of question-answer, individual and group work methods considering constructivism.

- Brutt-Griffler, J., & Cho, H. (2015). Integrated reading and writing: A case of Korean English language learners. Reading in a Foreign Language Journal, 27(2), 242–261.

- Dronjic, V., & Bitan, T. (2016). Reading, brain, and cognition. In Reading in a second language (pp. 32–69). Routledge.

- Faraj, A. K. A. (2015). Scaffolding EFL Students’ Writing through the Writing Process Approach. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(13), 131–141.

- Grabe, W. (2009a). Expanding reading comprehension skills. In Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice (pp. 287–340). Cambridge University Press.

- Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2011). Teaching and researching reading (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Grabe, W., & Zhang, C. (2013). Reading and writing together: A critical component of English for academic purposes teaching and learning. TESOL Journal, 4(1), 9–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.65

- Grabe, W., & Zhang, C. (2016). Reading-writing relationships in first and second language academic literacy development. Language Testing, 49(3), 339–355.

- Graves, M. F., & Graves, B. B. (2003). Scaffolding reading experiences: Designs for student success (2nd ed.). Christopher-Gordon.

- Hedgcock, J. S., & Ferris, D. R. (2009). Teaching readers of English: Students, texts, and contexts. Routledge.

- Hirvela, A. (2004). Connecting reading and writing in second language writing instruction. University of Michigan Press.

- Jonz, J. (1987). Textual cohesion and second‐language comprehension. Language Learning, 37(3), 409–438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1987.tb00578.x

- Kirn, E., & Hartmann, P. (2002). Interaction 1. In Reading (Silver edition). McGraw Hill.

- Kirn, E., & Hartmann, P. (2006). Interaction 2. In Reading (Silver edition). McGraw Hill.

- Miller, M. D., Linn, R. L., & Gronlund, N. E. (2009). Measurement and assessment in teaching (10th ed.). Pearson.

- Morris, C. D., Bransford, J. D., & Franks, J. J. (1977). Levels of processing versus transfer appropriate processing. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(5), 519–533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(77)80016-9

- Noori, A., Shafie, N. H., Mashwani, H. U., & Tareen, H. (2017). Afghan EFL Lecturers’ Assessment Practices in the Classroom. Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research, 3(10), 130–143.

- Numrich, C., & Kennedy, A. S. (2017). Providing guided practice in discourse synthesis. TESOL Journal, 8(1), 28–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.258

- Perfetti, C., Rouet, J. F., & Britt, M. A. (1999). Towards a theory of documents representation. In H. Van Oostendrop& & S. Goldman (Eds.), The construction of mental representations during reading (pp. 99–122). LawrenceErlbaum.

- Shanahan, T., & Lomax, R. G. (1986). An analysis and comparison of theoretical models of the reading–writing relationship. Journal of Educational Psychology, 78(2), 116–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.78.2.116

- Taylor, L. (2013). An overview of reading comprehension test design. In Testing reading through summary (pp. 40–55). Cambridge University Press.

- Trites, L., & McGroarty, M. (2005). Reading to learn and reading to integrate: New tasks for reading comprehension tests? Language Testing, 22(2), 174–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532205lt299oa

- Vonna, Y., Mukminatien, N., & Laksmi, E. D. (2015). The effect of scaffolding techniques on students’ writing achievement. Jurnal Pendidikan Humaniora, 3(3), 227–233.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In M. Gauvain& & M. Cole (Eds.), Readings on the development of children (pp. 34–40). Scientific American Books.

- Wegmann, B., & Knezevic, M. P. (2001). Mosaic 1: Reading (4th ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Yamashita, J. (2003). Processes of taking a gap-filling test: Comparison of skilled and less skilled EFL readers. Language Testing, 20(3), 267–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532203lt257oa

- Zhang, C. (2013). Effect of instruction on ESL students’ synthesis writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2012.12.001

Appendix 1

A—Demographic Survey

Code: _____________

Please fill in the background information requested below. You have five minutes. All information will remain confidential. Thank you.

Background Information

(1) First Language: ____________________________

(2) Gender (circle one): Male Female

(3) How comfortable are you in reading in English? Circle one answer.

Very comfortable b. Comfortable c. Uncomfortable d. Very Uncomfortable

(4) How comfortable are you in writing in English? Circle one answer.

Very comfortable b. Comfortable c. Uncomfortable d. Very Uncomfortable

(5) Think about what you read every week. What percentage of your reading is in English? Circle one answer.

~0-10% ~11-20 ~21-30% ~31-40% ~41-50%

~51-60% ~61-70% ~71-80% ~81-90% ~91-100%

Think about what you write every week. What percentage of your writing is in English? Circle one answer.

~0-10% ~11-20 ~21-30% ~31-40% ~41-50%

~51-60% ~61-70% ~71-80% ~81-90% ~91-100%

Appendix 1

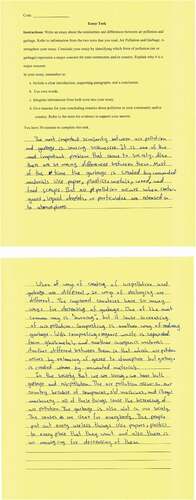

B - Reading-to-Write a Synthesis

Essay Task

Instructions: Write an essay about the similarities and differences between air pollution and garbage. Refer to information from the two texts that you read, Air Pollution and Garbage, to strengthen your essay. Conclude your essay by identifying which form of pollution (air or garbage) represents a major concern for your community and/or country. Explain why it is a major concern.

In your essay, remember to:

Include a clear introduction, supporting paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Use own words.

Integrate information from both texts into your essay.

Give reasons for your concluding remarks about pollution in your community and/or country. Refer to the texts for evidence to support your answer.

You have 30 minutes to complete this task.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Appendix 1

C - Gap-Filling Activity

Instructions for Gap-filling Task:

Refer back to the two texts, Air Pollution and Garbage, that you read and fill in the gaps below. Use words or phrases to complete the statements so that they reflect your understanding of the two texts.

You will have 30 minutes to complete this task.

Air pollution comes from cars, industry, and ____________________.

_________________kills all living things in a _______________over a long period of time. If its level rises high enough, all plant and animal life will ________________.

Wind scatters ________________in most areas creating ___________________, which makes it hard for people to _____________. It can also hurt people’s ______________.

The most common type of smog is called ______________which is created from a chemical called _____________.

Unwanted materials such as ___________________, wood, and food scraps are called _________________.

The safest method for waste disposal is _________________.

_________________ changes garbage into something that is actually helpful for the environment.

Some methods of waste disposal are (a) ________________, (b) ________________, and (c) landfills.

The amount of _______________and ______________that remains after _______________burns take up very little room in ____________.

Studies show that _____________today give off less ________________and ____________, which means less _______________is created.

________________is always dangerous, but some forms of _______________, such as debris, are useful and can be sold as __________________or ____________________.

While air pollution does not seem to create a ___________________ problem, garbage creates an _________________ problem, creating even more ____________________ conditions for ____________________ living in urban and ________________areas.

Humans not only _____________________ with __________________but also create __________________by burning ____________________mostly in and around cities.

While ___________________are considered a solution for dealing with waste, these require a long-term plan and collaboration of the ______________, industry, and ______________.

Appendix 1

D - Reading Texts (adapted from Hirschmann, 2005a, 2005b)

Garbage

People do not just pollute Earth’s air and water. They also litter the land with garbage – unwanted materials such as paper, plastics, metals, wood, and food scraps. In the United States, paper and cardboard products make up about 40 percent of the weight of city garbage. The rest is a mixture of yard trimmings, wood, glass, plastic, leather, cloth, and other materials.

Garbage builds up quickly near homes and businesses. It usually contains smelly and germ-filled food waste; therefore, it must be removed quickly. In most areas, this task is handled by garbage trucks. These trucks have built-in crushers that smash garbage to less than half its original volume. By doing this, trucks can gather more trash before dumping loads.

Once garbage has been collected, it is treated to make it smaller. The most common way is through incineration or burning. Incineration turns garbage into a mixture of ash and solid chunks of metal, glass, and other hard-to-burn materials. When the burning process is finished, garbage weighs only about 10 percent as much as it did originally.

Another way to reduce the size of garbage is through composting. With composting, organic waste (food scraps, lawn trimmings, and wood) is separated from glass, metal, and other inorganic materials. The organic waste is shredded to form debris. This debris is stored in piles and stirred every few days. Within a few weeks, bacteria within the debris have digested the waste. The left-over material is called compost. It is a safe, clean mixture that can be sold as mulch or soil fertilizer.

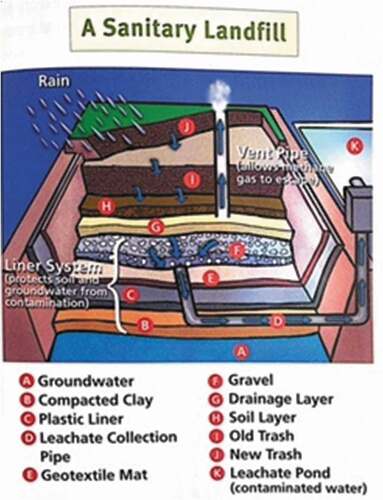

Not all garbage receives size-reduction treatments. Most is taken directly to sanitary landfills, which are safe dumping grounds for trash. Sanitary landfills have special liners that keep waste from touching underground or surface water. They are covered each day with a fresh layer of soil that traps smell and discourages bugs and rodents. These measures stop landfill garbage from polluting air or water.

All methods of garbage disposal have good and bad points. Incineration, for example, is an excellent way to shrink garbage volume. The small amount of ash and debris that remains takes up very little room in a landfill. However, incineration also releases many pollutants, including dangerous gases, cinders, dust, and soot. therefore, garbage must be burned in special furnaces that trap pollutants. These furnaces are expensive to build and operate. They also use a lot of electricity – and creating electricity usually involves the burning of fossil fuels, which creates air pollution.

Composting, too, has pros and cons. On the positive side, it changes garbage into something that is useful to the environment. On the negative side, composting only works for organic material, which makes up a small part of garbage. Also, finished compost can be hard to get rid of. Compost is a good natural fertilizer, but it is heavy and therefore expensive to ship.

Finally, landfills have many good and bad points. Landfills are the safest places to store most types of garbage. They are inexpensive to build and operate, and they can handle a lot of trash in a small space. Conversely, they produce methane, a poisonous gas that must be carefully controlled. And they can leak a pollutant called leachate if they are not well built. Leachate is created when water enters a landfill and picks up dangerous substances produced by decomposing garbage.

Serious problems are extremely rare at modern facilities. Today’s landfills are so sturdy that pollutants rarely escape. Abandoned and covered-over landfills are considered so safe that sometimes they are made into public recreation areas.

Air Pollution

Air pollution occurs when certain gases, liquid droplets, or particulates are released into the atmosphere. Sources of air pollution include exhaust from motor vehicles, factory smokestacks, and the burning of trash.

Most human-created air pollution comes from burning fossil fuels. Fossil fuels include coal, gasoline, and oil. When these substances burn, they release poisonous gases such as carbon monoxide and nitrogen oxides. They also release dust, soot, and other particulates. All these materials linger as pollution in the atmosphere.

Most air pollution is created in and around cities. Because wind carries pollutants thousands of miles from their sources, unpopulated areas sometimes suffer from air pollution too.

Air pollution near cities is usually called smog. The most common type is photochemical smog. It is created when exhaust from motor vehicles reacts with sunlight to form a chemical called ozone. Other substances in the exhaust join into droplets, creating a brown haze. This ozone rich haze makes it hard for people to breathe, and it can hurt people’s eyes. Coughing, sneezing, and nausea are other common reactions to photochemical smog.

In most areas, wind scatters smog. A few cities, however, are in places where geography and climate trap smog instead of carrying it away. Los Angeles and Denver are two such cities in the United States. Mexico City, Tokyo, and Buenos Aires, are other cities around the world that struggle with smog.

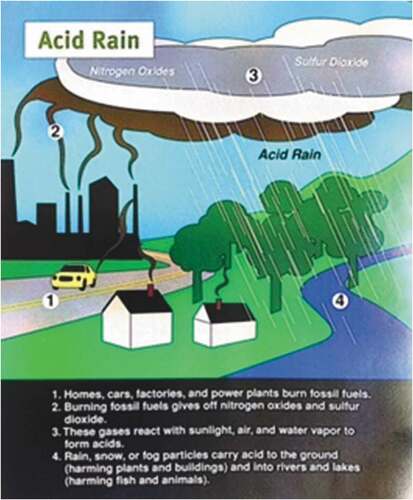

Acid rain is another problem created by air pollution. Acid rain starts when factories and motor vehicles release sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides in the air. These gases react with wind, sunlight, water vapor and oxygen to form acids. The acid droplets float on air currents for days or weeks. Rain or snow eventually pick them up and carry them to the ground.

Acid rain can kill all living things in lakes. When acid rain falls into a lake over a long period, fish, clams, and other lake animals begin to die. If the acid content of the lake rises high enough, all plant and animal life will disappear. A small percentage (less than 10 percent) of the lakes in Scandinavia, eastern Canada, and New York State qualify as “dead” lakes.

Acid may also harm trees. Some scientists believe that acidic fog around certain mountain areas, such as New York’s Adirondack Mountains damages tree leaves and bark. Over time, this fog may weaken the trees so much that they fall prey to insects or disease. It is very hard, however, to tell the difference between damage caused by acid fog and other causes. For this reason, it is difficult to know how bad the acid fog problem is.

Yet another effect of acid rain is damage to buildings and structures. For example, the walls of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. are covered with tiny holes where acid has eaten into the stone. Marble monuments in some cemeteries are so acid-etched that their words can no longer be read.

Scientists disagree about acid rain. Some feel it is a major problem that demands solutions. Others point out that even in the worst affected areas, only 4 to 5 percent of all lakes are severely acidified. Recent studies also show that rain is less acidic now than it was in the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, lakes and streams in many areas are becoming less acidic as well. This change is probably due to regulations put in place between 1970 and 1990. Factories today produce less sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides than they once did, so less acid rain is created.

Appendix 1

E – Rubric for Essay Task

Appendix 1

F – Answer Key for Gap-Filling

Burning of trash/fossil fuels/vehicles

a. Acid rain/air pollution

b. Lake/environment

c. Disappear/end/begin to die

3. a. Pollutants/smog

b. Chemical called ozone/brown haze/air pollution

c. Breathe

d. Eyes

4. a. photochemical

b. Ozone

5. a. Paper/plastic/metal/yard trimmings

b. Garbage

6. Sanitary landfills

7. Composting

8. a. Composting

b. Incineration

9. a. Ash

b. Debris

c. Garbage

d. Landfills

10. a. Factories

b. Sulfur dioxide

c. Nitrogen oxides

d. Acid rain/pollution

11. a. Air pollution

b. Garbage/organic waste

c. Mulch

d. Soil fertilizers

12. a. Garbage

b. Air pollution

c. Serious/hazardous/dangerous

d. People

e. Rural

13. a. Litter the land

b. Garbage

c. Air pollution/pollution

d. Fossil fuels/garbage

14. a. Sanitary landfills

b. Governments

c. People