Abstract

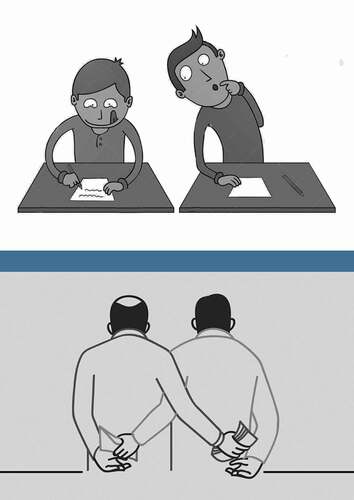

There has been a growing interest in determining whether dishonesty in college can be transferred to the professional workplace. There have been few, yet scarce, studies that focused on the link between college and workplace dishonesty. This review aims to bring into the limelight evidence-based consistency of the links between college and workplace dishonesty. Four databases were systematically scanned and yielded 18 articles related to dishonesty at the college and workplace levels were retrieved. Recognizing that there are only a few studies in this area that limit generalizations of this article, there are pieces of evidence that support a considerable association between college and workplace dishonest behaviors. Academic dishonesty in college can be considered more than just a matter of immediate academic repercussions, and it can also indicate potential workplace dishonesty to some degree. Instead, it tends to be a choice between producing ethical and unethical citizens or between preserving and smashing the profession. We have attempted to maintain academic integrity by developing multi-level intervention approaches that involve students, educators, administrators, and policymakers.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article is a review of whether academic dishonesty/cheating in college have the potential to be transferred to a professional workplace. It summarizes the findings of studies that focused on the relationship between college and workplace dishonest behaviors. According to the obtained findings of the research, there is a considerable association between college and workplace dishonest behaviors. That means students who are accustomed to cheating in college are also more likely to be cheated when they go to the workplace, which can be a potential problem for employers. As a result, we believe that all stakeholders should strive to ensure that students do not become a victim of college fraud in college.

1. Introduction

Academic dishonesty is commonplace in students’ academic pursuits far and wide (Premeaux, Citation2005; Tierney & Sabharwal, Citation2017). However, personal, sociological, institutional, and situational factors underpin the extent to which academic dishonesty occurs (Rettinger & Kramer, Citation2009; Yazici et al., Citation2011). Academic dishonesty, in this article, can be conceptualized as a “deliberate act, in that students make a conscious decision to engage in academic dishonesty” (Anderman et al., Citation2017, p. 95). Academic dishonesty and academic cheating are used interchangeably in this paper, as being used by (Yu et al., Citation2017). The explanation is that terms like academic cheating, academic misconduct, and academic dishonesty can be used interchangeably to refer to academic malpractice, although the expressions can vary in different contexts (Park et al., Citation2013). Each of the terms implies the deceptive attributes to impersonate a knowledgeable person (Anderman et al., Citation2017; Bloodgood et al., Citation2008). Studies show that most students have been occupied with dishonest behaviors at some point in their academic careers (Anderman et al., Citation2017). What makes it a great concern is that dishonesty in academia could be expanded to professional workplaces (Ballantine et al., Citation2014; Graves & Austin, Citation2008; Harding et al., Citation2004; Orosz et al., Citation2018). For example, there is a strong relationship between the frequency of dishonesty in academia and the recurrence of deceptive behavior in the real work environment (Nonis & Swift, Citation2001).

Given that dishonesty in college considerably impacts workplace trustworthiness (Grym & Liljander, Citation2017; Guerrero-Dib et al., Citation2020; Ma, Citation2013), it is more important than ever to revitalize and address this challenge. One way to achieve this goal is to have scientists working in this field and attempting to bring the links between college and workplace dishonesty into the spotlight. Accordingly, this review attempts to bring into the spotlight the association between college and workplace dishonesty. Thus, it may be conceivable to increase the sensitivity of educational stakeholders to academic dishonesty and the determination of higher education institutions to combat dishonest behaviors.

There are a plethora of investigations into how academic dishonesty undermines the quality of education and the factors that constitute dishonesty behaviors. However, a few emerging studies have focused on the relationship between college students’ academic cheating and actual workplace dishonesty (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000; Harding et al., Citation2004; Klein et al., Citation2007; Ma, Citation2013; Orosz et al., Citation2018). This pattern has been evident, especially in the fields of business and health, over the past two decades. However, there is a dearth of a systematic review that offers the consistency of the connection between college and workplace dishonest behaviors. In this paper, our primary goal is not just to abridge these scant findings and propose new ways to handle fraudulent behaviors. Rather, it is to bring the issue to the forefront and make it a point of discussion.

While there is an increasing interest in understanding the relationship, there are very few studies on the long-term impact of college dishonesty on workplace dishonesty. The mass media have likewise focused on the immediate consequences of academic cheating, just overlooking the intriguing enduring effects of dishonesty behaviors. The immediate pressures of academic dishonesty may also be seen from two broader perspectives (Lupton et al., Citation2010). First, a student who frequently engages in academic dishonesty has the advantage of higher grades without diligence. Therefore, the impartiality and effectiveness of educational assessments will be compromised and the relative capacity of a student cannot be measured. Second, academic dishonesty is presumed to decrease students’ enthusiasm for achieving viable instructional objectives both in terms of comprehending cutting-edge thoughts and applying instructional objectives. Moreover, rampant academic cheating damages creativity, innovation, and academic excellence (Shon, Citation2006).

Scientists who work in the field of academic integrity have long recognized the enduring impact of academic dishonesty (Harding et al., Citation2004; Laduke, Citation2013; Orosz et al., Citation2018). However, most scholars have not made a rigorous attempt to understand more deeply into the consolidated pieces of evidence for the fact that a synthesis of an article is sounder than the findings of a single article (Stern et al., Citation2014). The intention of this review was, therefore, to bring into the spotlight if college dishonesty would be extended to the workplaces. By drawing the attention of educators, policymakers, and politicians to this issue, this paper could be used to plan, develop, and monitor strategies for reducing academic dishonesty in colleges. To guide the review of how consistent college and workplace dishonesty is, we have forwarded the following research questions (a) Is there a substantial association between dishonesty in college and dishonesty in the workplace? (b) Do demographic factors influence dishonesty in college and the workplace? (c) How would educational stakeholders respond to college academic dishonesty?

2. Methods

A search of peer-reviewed articles published from 2000 to 2020 regarding the relationship between college and workplace dishonesty was conducted. The researchers chose this time frame because the studies focused on the relationship between college and workplace dishonesty have begun to appear over the last two decades. Papers were retrieved from four bibliographic databases: PubMed, IRIC, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar. These databases were selected because studies that focused on the relationship between college and workplace dishonesty are often available there. The search for papers occurred from March 2019 through April 2020. The researchers have used 2020 as a cutoff to include key findings of recent studies in the field. The search was limited to high-quality peer-reviewed journals to maintain the quality of the papers.

To perform a paper search, inclusion and exclusion criteria were devised to standardize the selection of papers based on the suggestion of Butler et al. (Citation2016), which embraces five explicit criteria: types of study, types of data, the phenomena under study, results, and demography. The inclusion criteria were intended to settle any predispositions and ensure that the articles are chosen distinctly based on the predefined criteria. Alongside setting the criteria for inclusion and exclusion, the researchers chose search terms related to academic dishonesty, college dishonesty, and workplace dishonesty. The complete search terms involve academic dishonesty, academic fraud, academic deception, academic cheating, plagiarism, college deviant behaviors, college misconduct, college unethical behaviors, workplace cheating, workplace deceptions, workplace misconduct, real-world dishonesty, and real-world cheating. In this review, only original papers published in the English language were considered.

In the initial paper search, the researchers identified 289 papers related to the relationship between academic and workplace dishonesty. The searched papers were downloaded to Mendeley 1.19.5 Reference Management Software, and 73 duplicates were removed. The abstracts of 216 papers were reviewed, and 54 have been discarded as irrelevant. Ultimately, the complete body of 162 papers was reviewed and 18 papers were deemed eligible for this review, as presented in . Generally, the findings from 6,223 participants, seven countries, and four continents were synthesized and consolidated in this review regarding the relationship between the college and workplace dishonesty.

Figure 1. The detail of procedures for the selection of sample articles in the review

3. Results

This review focuses on the association between college and workplace dishonest behaviors. The researchers presented data in the form of narration corresponding to the specific objectives as provided in . This review results generally show that academic dishonesty has been a widespread phenomenon throughout the world (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000), and it is a common concern to scholars (Klein et al., Citation2007). One of the big concerns is whether academic cheating in college will be transferred into the professional workplace. This paper presented a synthesis of scientific studies regarding the transferability of college cheating into the professional workplace to address this concern.

Table 1. A summary of each study included in this systematic review, including authors, country of study, research design, and key findings

3.1. Association between the college and workplace dishonesty

While the primary objective of this article is to determine whether dishonest behaviors in college will be extended to the workplace, it was found that academic dishonesty in college has a considerable association with workplace dishonesty. For instance, the entire findings of the papers included in this review show that college and workplace dishonesty have a considerable association except for the finding of Martin et al. (Citation2009). To mention some of these findings, nearly an equal number of participants reported that they had cheated in an academic setting and violated workplace policies (Harding et al., Citation2004). Bernardi et al. (Citation2015) also stated that students who are reported to have cheated at least once are more likely to cheat in the future. Likewise, Graves and Austin (Citation2008) stated that students who cheat on tests, paperwork, or both in college are more likely to engage in the misuse of property. An experimental study found that academic dishonesty in business schools predicted later behavior in a real business context. That means students who were dishonest in college were also dishonest in real business settings (Grym & Liljander, Citation2017). In a self-report survey, students who engaged in academic dishonesty scored higher on real-world personal risk behaviors such as unreliability, risky driving behaviors, and illicit activities (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000). Furthermore, the findings demonstrate that college dishonesty has the potential to influence workplace professional ethics (Lawson, Citation2004; Lucas & Friedrich, Citation2005; Nonis & Swift, Citation2001).

Based on the conclusions of the papers that were reviewed, it could be argued that there is a considerable association between academic integrity in college and acceptable moral standards in the workplace. In other words, the more students get involved in dishonest behaviors in college, the more possibility they are to be dishonest at work. However, this does not mean that dishonest behavior in the workplace is directly emanated from dishonest behaviors in college, because the articles included in this review were predominantly based on a self-report survey that was unable to determine cause-effect relationships.

Academic dishonesty in college may be extended into the workplace for various reasons and eventually incorporated into the plans of those involved in cheating. For instance, Bernardi et al. (Citation2015) expressed that those students who have cheated at least once in the past reported that they most likely tend to cheat in the future. Similarly, Klein et al. (Citation2007) stated that students might carry over an attitude of dishonesty in college into the workplace, potentially problematic for employers. It was also reported that when faced with the challenge of cheating, many students make the same decision in the end, both in college and in the workplace (Harding et al., Citation2004). It has also been reported that those students who consider any type of dishonesty as a serious offense in college are more likely to behave ethically in the workplace (Guerrero-Dib et al., Citation2020). Likewise, it was expressed that dishonesty in college has a relationship with deviant behaviors in the workplace (Graves & Austin, Citation2008). Furthermore, it has been reported that academic dishonesty in business schools has implications for later ethical behaviors in business contexts (Grym & Liljander, Citation2017). These pieces of evidence show that dishonest behaviors, attitudes, and propensity in college have the potential to be carried over from college to the workplace.

Researchers have a firm belief that fraud in college also affects the quality of life in the future (Ballantine et al., Citation2014; Bernardi et al., Citation2015; Graves & Austin, Citation2008; Harding et al., Citation2004; Krueger, Citation2014; Ma, Citation2013). For example, students who engaged in academic dishonesty in college also scored higher on dishonesty behaviors such as personal unreliability, risky driving behaviors, and illicit activities in the real world (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000). In another study, nursing students who were alleged to have cheated in college also reported having cheated in clinical settings (Bultas et al., Citation2017). In a similar setting, Krueger (Citation2014) expressed a significant relationship between self-reported academic dishonesty in the classroom and self-reported dishonesty in a clinical setting. Krueger further stated that more than half of the participants confessed that they had cheated both in the classroom and in clinical settings that affect the patient’s life. In a study involving engineering students, it was reported that a comparable number of students cheated both in the college and the workplace (Harding et al., Citation2004b). Even having at least one episode of cheating in college has been reported to have a high degree of association with cheating in the actual workplace (Bernardi et al., Citation2015) and the dishonesty in the workplace extends to the misuse of property and being unfaithful to the organization (Graves & Austin, Citation2008).

To be more specific, dishonesty in college may indicate at least one of the following five sorts of dishonest behaviors in the workplace: unethical behaviors, deviant behaviors, misuse of property, belief in cheating, and the ultimate decision making to cheat. Concerning unethical behaviors, a student who cheated to earn better grades in college is more likely to demonstrate comparable unethical behaviors in the workplace (Ballantine et al., Citation2018, Citation2014; Hsiao & Yang, Citation2011). It was also revealed that cheating in college is a better indicator of deviant behaviors in the workplace (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000; Graves & Austin, Citation2008; Harding et al., Citation2004). Likewise, college cheating has a strong connection with the misuse of property in the workplace (Graves & Austin, Citation2008), just as beliefs about dishonesty in college tend to be moved to the workplace. Accordingly, people may tend to replicate the same belief about cheating both in college and the workplace (Klein et al., Citation2007; Nonis & Swift, Citation2001). Finally, people who are accustomed to cheating in college may make the same choice when faced with the temptation to engage in cheating (Klein et al., Citation2007). Indeed, most of the students involved in dishonesty in college made similar ultimate decisions in the workplace (Harding et al., Citation2004).

3.2. Factors that constitute a relationship between the college and workplace dishonesty

Many variables moderate college and workplace dishonesty behaviors. For example, previous studies have shown that demographic factors, approaches to learning, values for integrity, attitudes toward dishonesty, propensity, academic disciplines, and institutional sensitivity can point to the trends of dishonesty. To begin with the demographic variables, male students reported significantly higher levels of academic dishonesty than female students in general (Ballantine et al., Citation2014; Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000; Grym & Liljander, Citation2017). It has also been reported that male students tolerate academic dishonesty more than female students, whereas values such as idealism are associated with academic dishonesty intolerance (Ballantine et al., Citation2014; Grym & Liljander, Citation2017). In another study, female students have witnessed more dishonest behaviors than their male counterparts (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000). Male students also reported significantly higher scores in illegal behaviors and drug use in particular (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000; Lucas & Friedrich, Citation2005). The reason might be that female students tend to be more comfortable with social needs than male students (Bernardi et al., Citation2015). Besides, there was no sex difference reported regarding false excuses according to (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000).

Grade levels and fields of study have also been linked to academic dishonesty behaviors. As students grow through academic hierarchies, they tend to tolerate less academic dishonesty (Bultas et al., Citation2017). Such issue is especially true while students progress from high school to college, from first degree to a Master’s degree and then to a Ph.D. degree. In terms of fields of study, students from the field of business are ranked first in dishonesty and succeeded by engineering, while students in health sciences are found to be more ethical (Harding et al., Citation2004b). It is also found that the learning approach has connections to college dishonesty. Indeed, in-depth learning is associated with a lower degree of academic dishonesty, while surface learning has been associated with a higher degree of academic dishonesty (Ballantine et al., Citation2018). These demographic variables indicate that academic dishonesty can be moderated by age, gender, learning style, and fields of study to a certain degree.

It is also reported that attitudes toward dishonesty and propensity to cheat determine college and workplace dishonesty. For example, there is a strong connection between students’ propensity to participate in dishonesty behaviors in college and the propensity to engage in such behaviors in the business world (Lawson, Citation2004). The author also reported that students’ responses to beliefs about ethics in the academic setting are strongly related to their responses to various situations in a non-academic environment. Likewise, Lawson (Citation2004, p. 195) stated that “cheaters are more likely to believe it is acceptable to lie to a potential employer on an employment application and to believe it is acceptable to use insider information when buying and selling stocks”. Furthermore, some findings show that students who tend to cheat on exams or plagiarize papers are more likely to demonstrate unethical behavior in the workplace (Klein et al., Citation2007; Nonis & Swift, Citation2001). These pieces of evidence indicate that it is not only the deeds of dishonesty that will be carried over from college to the workplace, but also attitude and propensity. Therefore, to trace academic dishonesty, it may be invaluable to consider students’ propensity.

The intensity of dishonesty can be moderated by the social and institutional sensitivity to dishonesty. For example, perceived college and workplace conditions have a strong potential for inducing or reducing dishonest behaviors (Guerrero-Dib et al., Citation2020; Harding et al., Citation2004). The more institutions place a high value on integrity and track it properly, the better students tend to behave in an ethical manner (Guerrero-Dib et al., Citation2020). One of the methods that institutions use to monitor academic integrity is the code of honor. Higher education institutions with an honor code have reduced academic dishonesty to a certain degree (Graves & Austin, Citation2008; Krueger, Citation2014). For example, a student who underwent an honor code or attributes his or her compliance just to the harsh penalty of code violations might show a significant change in the school setting; however, this may be less likely to advance in the workplace (Lucas & Friedrich, Citation2005). Additionally, if faculty can discuss academic misconduct and take measures following any academic dishonesty, the degree of fraud will be decreased (Ballantine et al., Citation2018; Bultas et al., Citation2017; Burke et al., Citation2007).

Students’ attitudes toward dishonesty in college can also greatly impact their actual dishonest behaviors in the future. For example, students may extend an attitude of dishonesty in college to the workplace (Klein et al., Citation2007). In another study, Bultas et al. (Citation2017) stated that “as students’ condemnatory attitude toward cheating increased, the frequency of dishonest behaviors in the clinical setting decreased”, p. 60. The authors further indicated that students who have a positive attitude to dishonesty have reported higher frequencies of academic dishonesty and are more likely to engage in workplace dishonesty. It is also reported that those students who scored higher on measures of personal unreliability also scored higher on measures of dishonest behavior in the real world (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000).

3.3. How should educational stakeholders respond to cheating in college?

There should be an increasing concern about college academic dishonesty because it can be carried over to the workplace. On the one hand, creating academic integrity safeguards educational productivity and the fair evaluation of students. On the other hand, academic dishonesty has an impact on future workplace behaviors. In other words, academic dishonesty is a threat to both immediate educational quality and sustained professional excellence. Consequently, a firm determination must be made to adapt intervention strategies that maintain academic integrity in a manner that is not dangerous to students’ livelihood and quality of education. By harmonizing both the quality of education and the well-being of students, this paper attempted to provide intervention strategies on how to respond to academic dishonesty. The intervention strategies presented in the subsequent sections were derived from the articles included in the review and a few extra articles.

Before suggesting intervention strategies, it is essential to comprehend dishonesty in an academic setting, which has a direct connection with the intervention techniques. The reasons why students cheat in college considerably vary from student to student and context to context. Indeed, several triggering factors can induce students to engage in college dishonesty (Simkin & Mcleod, Citation2010). In this article, such a factor can be classified as personal, situational, and assessment-related issues. The personal factors involve variables such as students’ ethical considerations, attitudes, social standing, demographic factors, self-esteem, intention, achievement, and program of study (Harding et al., Citation2004; Simkin & Mcleod, Citation2010; Yazici et al., Citation2011). The situational factors involve peer pressure, parental expectations, professor’s control, classroom conditions, the desire for higher grades, and high stakes testing (Iberahima et al., Citation2013; Lucas & Friedrich, Citation2005; Rettinger & Kramer, Citation2009; Simkin & Mcleod, Citation2010). The assessment-related factors are associated with the role of learning assessments in education. For instance, when the assessments focus on grades instead of learning, students are more likely to tend to be involved in cheating (Murdock et al., Citation2004; Yazici et al., Citation2011). Generally, the intervention strategies should consider all personal, situational, and assessment-related issues.

Although there is less dispute regarding giving particular attention to dishonest behaviors in college and taking immediate measures against such behaviors, the primary concern is whether the priority is given to behaviors or values. Behaviors refer to the details of an individual’s involvement in unauthorized phenomena. These behaviors involve copying from another student, allowing another student to copy, using unauthorized material without the professor’s permission, turning in term papers done by another student, sitting on exams for another student, and so on. The values refer to developing fundamental ethics such as honesty, trust, and responsibility. Since behavior and value are the two sides of the same coin, and they cannot be separated, this article stands that both behaviors and values should be highlighted side by side.

First, taking firm and fair measures should be prioritized in the short-term regarding the details of unauthorized phenomena to deter students from dishonesty (Graves & Austin, Citation2008; Ma, Citation2013). Besides, it is also very essential to focus on long-term value development. The long-term value development may help to create a generation that involves less in academic and workplace dishonesty. It is worthy in particular because numerous studies have demonstrated that morally incompetent students are more likely to engage in dishonesty than morally competent students (Ballantine et al., Citation2018, Citation2014; Hsiao & Yang, Citation2011; Nonis & Swift, Citation2001). Instead of just threatening each dishonest behavior, discussing the underlying reasons for forbidding dishonest behaviors is found to be productive (Klein et al., Citation2007). As a result, they may also carry over justified values and behaviors into the workplace.

There have been attempts to devise effective intervention techniques that can be implemented in academic settings. For instance, Nick and Llaguno (Citation2015) delineated five strategies that help reduce academic dishonesty. These strategies involve building relationships with students, helping students comprehend the importance of academic integrity, providing students with orientation programs, having students write honor codes and formative evaluation of students’ trustworthiness. While these intervention techniques appear to work and are more humanistic, they are likely restricted to the relationship between institutions and students, which overlook the roles of several stakeholders. In another study, increasing the admission of females into a profession is also supposed as one means of increasing academic integrity (Ballantine et al., Citation2014).

Consequently, this article relied on a multifaceted intervention approach that included both personal and situational factors. Such a situation begins with students and advances up to the education authorities. To begin with the personal factors, students may both intentionally or unintentionally engage in academic dishonesty. Students’ intentional involvement in academic dishonesty may be motivated by one of the following factors: a belief that dishonesty will not have a long-term impact on them or others; a desire to meet others’ expectations; the belief that everyone does it; recognition that they are not doing it; and a lack of time (Anderman et al., Citation2017; Bernardi et al., Citation2015; Brimble & Stevenson-Clarke, Citation2005; Mulisa, Citation2015; Mustaine & Tewksbury, Citation2005). Unintentionally, students may plagiarize or cheat with a poor understanding of what academic dishonesty is, mainly when they first enter college (Newton, Citation2015). For example, empirical evidence shows one of three students involved in cheating accidentally (Brimble & Stevenson-Clarke, Citation2005). As a result, corrective measures can be drawn from two views. At the outset, to avoid unintentional dishonesty, all acceptable and unacceptable academic phenomena should be explicitly communicated to students along with the consequences of each dishonest behavior. The reason is that there is no consensus on what exactly constitutes academic dishonesty in higher education (Graves & Austin, Citation2008; Klein et al., Citation2007; Krueger, Citation2014).

In the case of intentional dishonesty, researchers advocate strict rule enforcement by all educational authorities because contextual factors have a greater potential to influence students’ decisions to engage in dishonest behavior than personal factors (Murdock et al., Citation2004). For example, the way faculty members react to dishonest behaviors may exert a powerful influence on a student’s academic dishonesty (Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000). If students perceive faculty members have given little attention to dishonesty or show little concern about academic integrity, they are more likely to engage in dishonest behaviors (Iberahima et al., Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the faculty members and educational authorities should take prompt measures following each dishonesty phenomenon without compromising any rules. However, in one study, it was reported that the present laws might not fit with the dynamic nature of dishonest behaviors in college (Draper & Newton, Citation2017). Thus, a systematic intervention that targets college dishonesty needs a consistent update and amendment with the advancement of technology and cheating techniques. Furthermore, long-term plans should be developed to improve students’ attitudes and values toward integrity behaviors. Unless students’ attitudes and values toward academic dishonesty in college are altered, they tend to rationalize each dishonesty phenomenon (Lowe et al., Citation2018). Consistently, Bultas et al. (Citation2017) urged a frequent and timely discussion of appropriate behaviors and values to support students’ development of honesty and integrity beyond the classroom. The implication is that the faculty’s response to academic dishonesty and the implementation of institutional laws have great potential to reduce academic misconduct (Ma, Citation2013).

Peers are also considered to have the power to initiate dishonest behaviors in college (Rettinger & Kramer, Citation2009). Because a student wants to be perceived as knowledgeable and achieve higher grades (Jones, Citation2011), a peer is thought to have the potential to induce dishonest behaviors. In particular, the influence is more decisive in female-to-female interaction (Tsai, Citation2012). Hence, providing students with the skills to withstand peer pressure seems valuable. These efforts may improve the likelihood of integrity behaviors by resisting peer pressure. It is also possible to go beyond these categories and address some ways to deal with academic dishonesty. For example, higher education has the potential to reduce dishonest behavior in college if it fully shapes and develops students’ moral vision and purposes (Guerrero-Dib et al., Citation2020). Academic integrity can be improved by raising student understanding of what constitutes academic dishonesty and communicating the essence of academic integrity (Carpenter et al., Citation2007). Similarly, students may not fully comprehend the rules of academic dishonesty; therefore, faculty must be clear about what to expect and what academic honesty policies should be, as well as serve as role models and create positive learning environments for students (Krueger, Citation2014).

Smith (Citation2003) offered practical recommendations for stakeholders in academia, such as letting students know that professors are technologically savvy, indicating that detecting plagiarism is an easy process, involving tutors or writing centers to teach paraphrasing skills, redesigning coursework by dividing major research assignments into smaller, sequential steps that lead to the finished product, and investing in anti-plagiarism software. In addition to developing various technological activities to reduce the degree of academic dishonesty, it is further specified that some proactive measures that seem valuable. For example, activities such as faculty alert, student support, and diversity management positively impact reducing academic dishonesty. Faculty alert-it represents encouraging faculty to report any students who are dishonest in their studies as soon as possible to take positive steps that lead to a successful academic pursuit. Student support can be explained in terms of prioritizing student support rather than prioritizing remedial measures. In particular, it encourages students to have a good foundation for study skills. Diversity management refers to a service designed to make students have fair access to educational resources and learning experiences regardless of their background. Similarly, it was reported that providing training about academic dishonesty reduces academic fraud by educating students about misconduct (Perkins et al., Citation2020).

Nowadays, anti-plagiarism software is widely in use around the world to prevent academic dishonesty. However, such technologies effectively control fraud, and they cannot detect dishonesty behaviors outside the world of digital technology. For example, frauds that are not based on digital technology such as exam papers and academic correspondence of less developed countries are less likely to be controlled by such technologies. Even in the digital world, anti-plagiarism checkers only detect whether the manuscript is original or not and cannot tell us who did it. It does not reduce the fraud that occurs behind the wall (Draper & Newton, Citation2017). Hence, in addition to the existing software, it may include integrating technology that monitors progressive practice that strengthens integrity behaviors. For dishonest behaviors in the exam sessions, both camera-based and software-based technologies that help monitor academic honesty better explore all student movements, actions, and reactions, and practices appear important. In the case of contract cheating, which is out of control of technology, Perkins et al. (Citation2020) suggests collecting student writing samples, creating assignments that focus on particular material rather than generic papers, integrating critical thinking tests and personal involvement, and using alternative assessments such as testing, oral presentations, and reports.

3.4. Discussions

There has been an increasing interest in understanding whether college academic dishonesty can be extended into the workplace. The primary objective of this review was to highlight the association between college and workplace dishonesty and bring it into the spotlight. Attempts have also been made to understand the factors affecting dishonest behavior in college. However, a couple of limitations must be taken into account in attempting to answer the research questions. First, nearly all articles used in this review were based on self-report studies. Consequently, it may be impossible to determine the cause-effect relationship between college and workplace dishonesty. Second, there was a scarcity of articles that directly focused on the relationship between college and workplace dishonesty. Consequently, a large number of articles could not be assembled and the geographic distribution of the articles may not be representative since most of the articles were from the US, which could have a considerable bearing on the generalization of this paper’s outcome worldwide. Instead of inconsistencies in findings among the available publications, the problem is that there are fewer articles focused on this topic.

Enduring these limitations, it seems reasonable to state that dishonesty in college has the potential to be transferred to the workplace. This transferability could imply that the more students are exposed to dishonesty in college, the more probable it is that they will participate in dishonesty later in the workplace. Besides, the more we tolerate college dishonesty, the higher the likelihood we produce a dishonest society for the future workplace, as highlighted by Ma (Citation2013). Higher education should be, therefore, a struggle against dishonest behaviors unreservedly for it has the potential to indicate future workplace behaviors, which is stressed by Harding et al. (Citation2004) and Klein et al. (Citation2007). However, there is no guarantee maintaining that academic integrity in college will improve trustworthiness in the workplace.

Put succinctly, integrity is believed to be one of the fundamental values that employers need from the employees they recruit. It is a trait that an ethical employee demonstrates at the workplace and a foundation to establish healthy interpersonal relationships with coworkers and employers. Dishonest behaviors, on the other hand, make it challenging to build such trust in the workplace. Thus, reducing dishonesty seems valuable to contributing to competent and ethical employees in the market (Brimble & Stevenson-Clarke, Citation2005). Such effort might be why Burke et al. (Citation2007) asserted that forging ethical professionals begins in the classroom. There is also another dark side of dishonesty in college besides transferring into the professional workplace. It has a contagious feature (Saidin & Isa, Citation2013) and could be extended to the honest community down to the next generations. The cumulative of these results show that, unless a series of measures are taken, it might jeopardize academic outcomes, the credibility of professions, and influence workplace trustworthiness.

Given that academic dishonesty could be transferred from college to the workplace and impact future behaviors, it seems college dishonesty has just more than academic implications. It even seems a matter of choice between producing ethical and unethical citizens or between preserving and smashing the profession because it places the academic output in jeopardy. For example, to address the tip of the iceberg, who wants treatment with a medical doctor who cheated right through college? Patients will die at the hand of such a doctor. Who wants justice with a lawyer who cheated right through college? Justice will be lost at the hand of such a lawyer. Who wants a teacher who cheated right through college? Such a teacher will spoil the students. If dishonesty in college continues, we rather favor producing unethical citizens that spoil the generations. Therefore, we must give special attention to curbing dishonesty in college, which may in turn influence ethical behaviors in the workplace.

Highlighting the rigorous and consistent intervention of college dishonesty, it is essential to note that several factors can determine its magnitude. Among the determinants, students’ sex, age, grade levels, propensity, fields of study, learning style, idealism versus realism, and pedagogical approaches can be mentioned. For example, there are pieces of evidence that academic dishonesty is higher for males than for females (Ballantine et al., Citation2014; Blankenship & Whitley, Citation2000; Grym & Liljander, Citation2017). For example, Ballantine et al. (Citation2014) argue that increasing the admission of females to a given field of study, such as accounting, increases integrity in the workplace. Although this intervention technique seems sound in a specific discipline such as accounting, it appears defective across entire fields of study and in traditionally male-dominated careers. In contrast, in another study, Ip et al. (Citation2018) stated that there is no statistically significant gender difference regarding engaging in various forms of dishonesty behaviors in college. The reason could be that dishonesty contextual factors can influence academic dishonesty. While it appears cumbersome to address each determinant factor, what should not be overlooked is a learning approach, such as in-depth and surface learning. Indeed, if teachers use strategic learning and in-depth learning approaches, instead of surface learning, there is an opportunity to reduce academic dishonesty in college, as highlighted by (Ballantine et al., Citation2018), However, it is yet challenging to assess how well each student has adopted strategic learning and in-depth learning in the real classrooms.

Considering the consequences of college dishonesty and the factors that determine its magnitude, formulating intervention strategies seems invaluable. Regarding the intervention techniques, several rules and regulations have been developed and implemented across the globe to avoid dishonesty. However, dishonesty remains one of the major challenges in the academic setting. The reason is that perhaps the intervention strategies such as rules and regulations are primarily focused just on specific targets, such as students. This paper chose to depend on multi-level intervention techniques involving students, educators, administrators, and policymakers.

Fundamentally, a series of actions need to be taken to improve students’ conception of dishonest behaviors and their short-term and long-term consequences as they do not view it as a violation of academic integrity (Burgason et al., Citation2019). As a result, students may be less likely to engage in such dishonest behavior. Particularly, the development of value orientation appears very valuable to increase students’ integrity (Hsiao & Yang, Citation2011). As an immediate actor in the educational setting, the intervention strategies used by educators may focus on deterring the details of unauthorized behaviors and placing themselves as role models for younger generations. This method may be effective as focusing on the prevention of academic dishonesty has several advantages over taking remedial measures, which is stressed by (Stoesz & Yudintseva, Citation2018). As a result, socially responsible faculty members can help to reduce dishonesty in higher education institutions (Simkin & Mcleod, Citation2010). Besides, they should also be conscious enough of the detailed scams that students use, which may help them take further preventive measures.

Faculty members should take consistent and firm measures amidst the unresponsive bureaucracies of higher education institutions. If students recognize that professors overlook academic dishonesty and tolerate these behaviors, they are more likely to engage in dishonest behaviors, which were stated by (Bernardi et al., Citation2015). In the case of suspected academic dishonesty, along with the suggestion of Burke et al. (Citation2007), teachers need to take practical measures. Burke presented the details of the intervention, such as reassigning the work, reducing grades, providing F grades for the student, reporting the incident to the concerned stakeholders, and even keeping a record of academic dishonesty in the student’s academic file. Furthermore, as indicated by Klein et al. (Citation2007), regular classroom discussions with students, organizational meetings with students, and informative orientations have the potential to reduce college dishonesty.

College professors can also reduce academic dishonesty if there is an unreserved commitment to safeguarding academic integrity because dishonesty is contagious by nature, which begins with an individual and gradually extends to others (Saidin & Isa, Citation2013). Some dishonest behaviors such as inconsistency with the rule of law, tolerating taking measures according to the law, and being reluctant to monitor integrity are supposed to hearten students to the academic offense (Bernardi et al., Citation2015). As a result, there should be no room for any dishonest behavior in academic settings. Furthermore, faculty members must take measures such as focusing on authentic assessment, readmitting tests, rejecting theses and reports, dismissing students from the course, and invalidating the results according to (Ballantine et al. (Citation2018), Burke et al. (Citation2007), and Harding et al. (Citation2004). Since cheating is always supported by new technologies (Peytcheva-Forsyth et al., Citation2018), faculty members should update themselves periodically with in-depth research findings associated with the techniques students use to cheat.

The other stakeholders are educational authorities next to faculty members and students. The intervention strategies that these authorities could take may include a strategic plan to increase the value of academic integrity and reinforcing rules. Strengthening rules can be implemented both for all faculty members and students (Harding et al., Citation2004) Administrators must arrange platforms to promote academic integrity and establish standards to forestall academic dishonesty in college. This effort is made because students’ involvement in dishonest behavior partly relies on the faculty members (Murdock et al., Citation2004). Hence, administrators should denounce a faculty member who overlooks students’ dishonest behaviors. Additionally, policymakers need to focus on the long-term development of values to promote organizational cultures that place a high value on academic integrity besides drafting rules of law for short-term interventions.

To recapitulate, in the 21st century of the knowledge economy, academic dishonesty in college is perceived as a signal of a big emergency. If dishonesty is so prevalent in college, students may lack the necessary knowledge and skills to achieve the objectives, which inevitably results in a loss of social and economic benefits associated with the given knowledge. This lack of the economy of knowledge, in turn, makes the given country less competent and more subordinate. Therefore, educational authorities should focus on reducing college dishonesty that is supported by technology and may incorporate creating an ethical society in academic settings, as suggested by Ma (Citation2013), improving the self-esteem of students Harding et al. (Citation2004) and Yazici et al. (Citation2011), in-depth learning instructional approaches Ballantine et al. (Citation2018), assessing students’ authentic performance Murdock et al. (Citation2004), consistent monitoring and evaluation systems, and giving media coverage for academic dishonesty.

4. Conclusion

This review was intended to bring into the spotlight the consistency of the association between college and workplace dishonesty and the increasing sensitivity of educational stakeholders about college dishonesty. There have been growing, but limited investigations that have focused on the relationship between dishonesty in college and dishonesty in the workplace. Given the limited number of articles dedicated to this area, the scrutiny of the findings proves that dishonesty has the potential to be extended from college to the workplace. Indeed, dishonest behaviors in college can to some extent predict dishonest behaviors in the workplace. Furthermore, it has been attested that dishonesty in college has far-reaching enduring implications besides its immediate academic jeopardy. These dishonest behaviors are often accompanied by different personal and demographic factors, such as an attitude toward dishonesty and the ultimate decision to succeed in the shortcut.

As a result, tolerating dishonest behaviors in college seems to support dishonest students who may continue to be dishonest in the future. Thus, maintaining academic integrity in college may increasingly contribute to the credibility of the workplace. To gradually maintain academic integrity, the intervention strategies at the level of students, faculty members, administrators, and policymakers need to be synergistically implemented. Accordingly, students should fully understand all the ethical and unethical academic behaviors, the short-term and long-term consequences of dishonesty, and the importance of respecting academic integrity. Faculty members should also exercise academic integrity, discuss issues of dishonesty with students, and take prompt measures as required by law. Administrators should focus on developing an organizational culture of academic integrity and strengthening the enforcement of the academic integrity rules, while policymakers should focus on policies and technologies that would help to build a culture of academic integrity. Finally, as a direction for future research, intense findings should be directed toward integrating the types of policies, technologies, and pedagogical approaches that create an academic community that values academic integrity.

Data availability statement

In this article, there were four databases (PubMed, IRIC, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar) used to collect data. Because the present data were collected from the 18 articles incorporated in the review, it could be possible for readers and reviewers to access the data.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Feyisa Mulisa

Feyisa Mulisa is an assistant professor at the Institute of Education and Behavioral Sciences (IEBS), Ambo University, Ethiopia. Previously, he was a staff member of the Department of Psychology, Bahir Dar University. He was also the Head of the Department of Psychology. At present, he is working as an academic affairs vice Dean at IEBS, Ambo Univesity.

Asrat Dereb Ebessa is a lecturer in the Department of Educational Planning and Management, Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia. At present, he is a Ph.D. candidate at Tampere University, Finland. Previously, he was a Dean of the College of Education and Behavioral Sciences.

References

- Anderman, E. M., Koenka, A. C., & Koenka, A. C. (2017). The relation between academic motivation and cheating. Theory Into Practice, 56(2), 95–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2017.1308172

- Ballantine, J. A., Guo, X., & Larres, P. (2018). Can future managers and business executives be influenced to behave more ethically in the workplace? The impact of approaches to learning on business students’ cheating behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 149(1), 245–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3039-4

- Ballantine, J. A., McCourt Larres, P., & Mulgrew, M. (2014). Determinants of academic cheating behavior : The future for accountancy in Ireland. Accounting Forum, 38(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2013.08.002

- Bernardi, R. A., Banzhoff, C. A., Martino, A. M., & Savasta, K. J. (2015). Cheating and whistle-blowing in the classroom. Research on Professional Responsibility and Ethics in Accounting, 15, 165–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/S1574-0765(2011)0000015009

- Blankenship, K. L., & Whitley, B. E. (2000). Relation of general deviance to academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 10(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1001_1

- Bloodgood, J. M., Turnley, W. H., & Mudrack, P. (2008). Influence of ethics and instruction, religiosity, and intelligence on cheating behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(3), 557–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/sl0551-007-9576-0

- Brimble, M., & Stevenson-Clarke, P. (2005). Perceptions of the prevalence and seriousness of academic dishonesty in Australian universities. Australian Educational Researcher, 32(3), 19–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03216825

- Bultas, M. W., Schmuke, A. D., Davis, R. L., & Palmer, J. L. (2017). Crossing the “line”: College students and academic integrity in nursing. Nurse Education Today, 56, 57–62. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.012

- Burgason, K. A., Sefiha, O., & Briggs, L. (2019). Cheating is in the eye of the beholder: An evolving understanding of academic misconduct. Innovative Higher Education, 441, 203–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-9457-3

- Burke, J. A., Polimeni, R. S., & Salvin, N. S. (2007). Academic dishonesty: A crisis on campus. The CPA Journal, 77(5), 58–65.

- Butler, A., Hall, H., & Copnell, B. (2016). A guide to writing a qualitative systematic review protocol to enhance evidence-based practice in nursing and health care. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12134

- Carpenter, D. D., Harding, T. S., & Finelli, C. J. (2007). The implications of academic dishonesty in undergraduate engineering on professional ethical behavior. Proceedings of the world environmental and water resources congress 2006, 248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1061/40856(200)341

- Draper, M. J., & Newton, P. M. (2017). A legal approach to tackling contract cheating? Int J Educ Integr, 12(11). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-017-0022-5

- Graves, S. M., & Austin, S. F. (2008). Student cheating habits: A predictor of workplace deviance. Journal of Diversity Management, 3(1), 15–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19030/jdm.v3i1.4977

- Grym, J., & Liljander, V. (2017). To cheat or not to cheat? The effect of a moral reminder on cheating. Nordic Journal of Business, 65(3–4), 18–37.

- Guerrero-Dib, J. G., Portales, L., & Heredia-Escorza, Y. (2020). Impact of academic integrity on workplace ethical behaviour. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-0051-3

- Harding, T. S., Carpenter, D. D., Finelli, C. J., & Passow, H. J. (2004). Does academic dishonesty relate to unethical behavior in professional practice? An exploratory study. Science and Engineering Ethics, 10(2), 311–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-004-0027-3

- Harding(b), T. S., Passod, H. J., Carpente, D. D., & Finelli, C. J. (2004). An examination of the relationship between academic dishonesty and professional behavior. LEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, 46(5), 133–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/MAP.2004.1388860

- Hsiao, C. H., & Yang, C. (2011). The impact of professional unethical beliefs on cheating intention. Ethics & Behavior, 21(4), 301–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2011.585597

- Iberahima, H., Husseinb, N., Samatc, N., Noordind, F., & Daude, N. (2013). Academic dishonesty: Why business students participate in these practices? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90, 152–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.076

- Ip, E. J., Pal, J., Doroudgar, S., Bidwal, M. K., & Shah-Manek, B. (2018). Gender-based differences among pharmacy students involved in academically dishonest behavior. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 82(4), 337–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe6274

- Jones, D. R. (2011). Academic dishonesty: Are more students cheating? Business Communication Quarterly, 74(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1080569911404059

- Klein, H. A., Levenburg, N. M., McKendall, M., & Mothersell, W. (2007). Cheating during the college years: How do business school students compare? Journal of Business Ethics, 72(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9165-7

- Krueger, L. (2014). Academic dishonesty among nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 53(2), 77–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20140122-06

- Laduke, R. D. (2013). Academic dishonesty today, unethical practices tomorrow? Journal of Professional Nursing, 29(6), 402–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.10.009

- Lawson, R. A. (2004). Is classroom cheating related to business students’ propensity to cheat in the “real world”? Journal of Business Ethics, 49(2), 189–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BUSI.0000015784.34148.cb

- Lowe, M. S., Londino-smolar, G., Wendeln, K. E. A., & Sturek, D. L. (2018). Promoting academic integrity through a stand-alone course in the learning management system. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(13), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0035-8

- Lucas, G. M., & Friedrich, J. (2005). Individual differences in workplace deviance and integrity as predictors of academic dishonesty. Ethics & Behavior, 15(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb1501_2

- Lupton, R. A., Chapman, K. J., & Weiss, J. E. (2010). International perspective: A cross-national exploration of business students’ attitudes, perceptions, and tendencies toward academic dishonesty. Journal of Education for Business, 75(4), 231–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320009599020

- Ma, Z. (2013). Business students’ cheating in classroom and their propensity to cheat in the real world: A study of ethicality and practicality in China. Asian Journal of Business Ethics, 2(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13520-011-0012-2

- Martin, D. E., Rao, A., & Sloan, L. R. (2009). Plagiarism, integrity, and workplace deviance: A criterion study. Ethics & Behavior, 19(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420802623666

- Mulisa, F. (2015). The prevalence of academic dishonesty and perceptions of students towards its practical habits: Implication for quality of education. Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal, 4(2), 309–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4314/star.v4i2.43

- Murdock, T. B., Miller, A., & Kohlhardt, J. (2004). Effects of classroom context variables on high school students’ judgments of the acceptability and likelihood of cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 765–777. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.765

- Mustaine, E. E., & Tewksbury, R. (2005). Southern college students’ cheating behaviors: An examination of problem behavior correlates. Deviant Behavior, 26(5), 439–461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/016396290950659

- Newton, P. (2015). Academic integrity: A quantitative study of confidence and understanding in students at the start of their higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(3), 482–497. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1024199

- Nick, J. M., & Llaguno, M. (2015). Dealing with academic dishonesty: A redemptive approach. Journal of Christian Nursing: A Quarterly Publication of Nurses Christian Fellowship, 32(1), 50–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000126

- Nonis, S., & Swift, C. O. (2001). An examination of the relationship between academic dishonesty and workplace dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Journal of Education for Business, 77(2), 69–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320109599052

- Orosz, G., Tóth-király, I., Bothe, B., Paskuj, B., Berkics, M., Fülöp, M., & Roland-Lévy, C. (2018). Linking cheating in school and corruption. Revue Européenne De Psychologie Appliquée, 68(2), 89–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erap.2018.02.001

- Park, E. J., Park, S., & Jang, I. S. (2013). Academic cheating among nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 33(4), 346–352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.12.015

- Perkins, M., Gezgin, U. B., & Roe, J. (2020). Reducing plagiarism through academic misconduct education. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 16(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-020-00052-8

- Peytcheva-Forsyth, R., Aleksieva, L., & Yovkova, B. (2018). The impact of technology on cheating and plagiarism in the assessment - The teachers’ and students’ perspectives. AIP conference proceedings 2048, 020025. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5082055

- Premeaux, S. R. (2005). Undergraduate student perceptions regarding cheating: Tier 1 versus Tier 2 AACSB accredited business schools. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(4), 407–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-2585-y

- Rettinger, D. A., & Kramer, Y. (2009). Situational and personal causes of student cheating. Research in Higher Education, 50(3), 293–313. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9116-5

- Saidin, N., & Isa, N. (2013). Investigating academic dishonesty among language teacher trainees: The why and how of cheating. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 90, 522–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.122

- Shon, P. C. H. (2006). How college students cheat on in-class examinations: Creativity, strain, and techniques of innovation. Plagiary: Cross- Disciplinary Studies in Plagiarism, Fabrication, and Falsification, 1, 130‐ 148.

- Simkin, M. G., & Mcleod, A. (2010). Why do college students cheat? Journal of Business Ethics, 94(3), 441–453. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0275-x

- Smith, B. (2003). Fighting cyberplagiarism. NetConnect, 22–23. http://web12.epnet.com

- Stern, C., Jordan, Z., & Mcarthur, A. (2014). Developing the review question and inclusion criteria: The first steps in conducting a systematic review. America Journal of Nursing, 114(4), 53–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000445689.67800.86

- Stoesz, B. M., & Yudintseva, A. (2018). Effectiveness of tutorials for promoting educational integrity: A synthesis paper. International Journal for Educational Integrity, 14(6), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-018-0030-0

- Tierney, W. G., & Sabharwal, N. S. (2017). Academic corruption: Culture and trust in Indian higher education. International Journal of Educational Development, 55, 30–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.05.003

- Tsai, C. (2012). Peer effects on academic cheating among high school students in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev, 13(1), 147–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-011-9179-4

- Yazici, A., Yazici, S., & Erdem, M. S. (2011). Faculty and student perceptions on college cheating: Evidence from Turkey. Educational Studies, 37(2), 221–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2010.506321

- Yu, H., Glanzer, P. L., Sriram, R., Johnson, B. R., & Moore, B. (2017). What contributes to college students’ cheating? A Study of Individual Factors. Ethics and Behavior, 27(5), 401–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2016.1169535