Abstract

This paper investigates the differentiated educational ideologies projected during the Japanese colonial era by comparing the Japanese language textbooks used by Korean and Japanese primary students at that time. By comparing the texts and images in Kokugotokuhon (Japanese language textbooks for Korean students) and Shougakutokuhon (Japanese language textbooks for Japanese students) with critical discourse analysis (CDA) in analysis of texts and visual image analysis (VIA) for images, this paper verifies the differentiated educational ideologies that Japanese colonial authorities presented to Korean students. There were three findings that were featured in the Japanese language textbooks for Korean students that were absent from the textbooks for Japanese students. Firstly, depictions of physical labour and helping parents after school and late at night were present only in the textbooks for Koreans. Secondly, Japanese nationalism with an Emperor-centred ideology was emphasised in the Japanese language textbooks used by Koreans. Thirdly, the textbooks encouraged Korean students to practise war-like games and drills. The results from this study suggest that differentiated education was provided to Korean students during the Japanese colonial era via the contents of the Japanese language textbooks, which projected the colonial ideologies of the Japanese government. Korean students were being educated to become Japanese colonial subjects.

Public interest statement

Although texts and images are generally believed to convey neutral knowledge, they can also be used to convey biased sentiments. Therefore, it is important to analyse both to reveal the ideologies a textbook may promote to a reader, and how they are implanted. In order to investigate the differentiated educational ideologies projected during the Japanese colonial era, the Japanese language textbooks used by the Korean and Japanese students at the time are analysed and compared. Comparison of the textbooks revealed the differentiated educational ideologies that were presented to the Korean students by Japanese colonial authorities, and further analysis discovered that physical labour, Japanese nationalism, and war-like games were emphasised to the Korean students. The result from this study is used to lead research regarding the ideologies that may be conveyed to the colonized through textbooks published by the colonizing country.

1. Introduction

During the colonial period in Korea, the publication of textbooks was controlled by the Japanese and their purchase was mandatory. As the use of these textbooks was imposed, they could be used to inculcate students with a particular understanding, with the intention of leading students towards acceptance of Japanese ruling ideologies, interests and cultural values. The existing Korean curriculum was replaced in order to confer benefits for the colonisers, while ignoring the needs of the colonised (Pennycook, Citation2016).

Ideal citizens were described in the Japanese textbooks as subordinate Koreans who were portrayed as being obedient and faithful subjects to the Japanese Empire (Kang Jin-ho et al., Citation2007; Kim; Hye-lyeon, Citation2011). The colonial curriculum was used to reconstruct Koreans as Japanese imperial subjects, and tried to negate the Koreans’ national spirit and identity in order to legitimise Japanese imperial ideologies (Lee Dong-bae, Citation2012; Peng & Chu, Citation2017; Kim; Sun-jeon et al., Citation2014). By changing an imperial language into a national language, and by stressing the importance of the colonised learning the Japanese language, the Japanese colonial curriculum aimed to deprive the Korean people of their national spirit and identity, and to establish them as imperial citizens of Japan.

When Korea was colonised, Japanese was imposed as the national language, and Japanese textbooks were used in Korean schools. A major role for the Japanese language textbooks was to strongly promote Japanese nationalism. Fostering Japanese nationalism among Korean citizens was to assimilate the Koreans, and this was achieved by misrepresenting Korean history in textbooks while educating Koreans about the history of Japan (Je-hong & Sun-jeon, Citation2016). Therefore, it is necessary to study Japanese language textbooks, as it can be considered to impose the ideology of the Japanese colonial nation onto the Korean students and thus create ideal colonial citizens through education of the Japanese language. Moreover, separate studies have been conducted on Japanese and Korean language textbooks for Koreans but no studies have attempted to generate a differentiated citizen from the two different Japanese language textbooks used in Japan and Korea.

Previous studies of education in Korea during Japanese colonial rule have primarily been concerned with how education policy was influenced by the Japanese government (Kwak Jin-o, Citation2011; Park Soo-bin, Citation2011). However, by focusing on broad education policy, such studies have provided little examination of the language curricula employed during the colonial era in Korea (Park Young-gi, Citation2008, p. 4). In order to understand the Japanese colonial curricula, it is essential to investigate the textbooks, since they are tools used to play out the agendas of school curricula, thereby portraying the values of the dominant culture and its practices (Venezky, Citation1992).

Textbooks are considered officially-sanctioned school knowledge—knowledge that students learn at school—and have greater influence and credibility than ancillary materials created by teachers (Lee Dong-bae, Citation2000; Sheldon, Citation1988). These books are selected by scholars and teachers, and are then used in schools and thus are reproduced in the curriculum. The school curriculum portrays the values of the dominant culture, and its practices and textbooks are considered a significant part of this (Venezky, Citation1992). The knowledge presented in the textbooks is legitimised by both writers and teachers, and then becomes a norm in the curriculum.

Most scholars who have examined the colonial curriculum, e.g., Suck Ji-hye (Citation2008) and Jeong Jae-cheol (Citation2009), based their research on Sushinseo, the disciplinary training textbook used in primary schools during the Japanese colonial period. However, each of these scholars restricted their research—by only looking into texts (Jeong Jae-cheol, Citation2009) or only pictures (Suck Ji-hye, Citation2008). Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation1996, Citation2006) and Fairclough (Citation2001, Citation2013), scholars in the field of critical analysis of visual images and texts, state that there are various sociocultural values and ideological messages that are embedded in both texts and visual images. Throughout KokugotokuhonFootnote1 and Shougakutokuhon,Footnote2 written texts were often accompanied with visual images. Therefore, it can be seen that by analysing both texts and images, this study will provide stronger results and more detailed findings on what ideologies are conveyed.

Japanese and Korean students used different Japanese language textbooks in this period, and a comparison of these can help to uncover what different ideologies were promoted to Korean students and what colonial aims were furthered. Since this study is the first to investigate and compare (using CDA and VIA) the ideologies presented in the different Japanese language textbooks used by Japanese and Korean students, it presents new and significant results. Additionally, previous studies have analysed only those textbooks that were used in Korea by Korean students, such as Sushinseo (“moral education book”) and music textbooks (Jang Mi-kyong, Citation2013), or compared Korean language textbooks with Japanese language textbooks (Kim Yoon-joo, Citation2011; Kang Jin-ho, Citation2011). However, to illuminate differentiated ideologies, it is important to look at the Japanese textbooks for both Korean and Japanese students, and thus this paper will comparatively analyse the Japanese language textbooks used by both Korean and Japanese students during the colonial era.

In order to find out how Japanese colonial authorities projected specific subjectivities onto the colonised, this paper examines how the Japanese administration promoted different educational ideologies, which ideologies were dominant in each set of textbooks, and what different ideologies were embedded in the textbooks used for Korean and Japanese students.

2. Ideology in the textbooks

Inclusions and omissions in education systems are revealing, especially those in teaching materials (including textbooks)—concepts of ideology relating to the questions of what has been included/represented and what aspects have been omitted have been fruitful areas for research. Althusser (Citation2014) claimed that ideology can be reproduced through the school curriculum, stating that schools ensure subjection to a dominant ideology “or else the ‘practice’ of it; every agent of production, exploitation, or repression … has to be ‘steeped’ in that ideology” (p. 51).

Fairclough (Citation2003) stated that “ideologies are representations of the world, which contribute to establishing and maintaining relations of power, domination and exploitation” (p. 218). Based on this definition, it can be inferred that colonial power, domination, and exploitation are connected to colonial ideology. This study will focus on the way ideology is used to construct, legitimise and transmit power over the colonised (the Koreans) to achieve the coloniser’s (the Japanese) goals.

Selective tradition is an “intentionally selective version of a shaping of past and a pre-shaped present, which is then powerfully operative in the process of social and cultural definition and identification” (Williams, Citation1977, p. 115). Based on Williams’s idea of the selective tradition, Apple (Citation2012) states,

(Textbooks) signify, through their content and form, particular constructions of reality, particular ways of selecting and organising that vast universe of possible knowledge. They embody what Raymond Williams called the selective tradition: someone’s selection, someone’s vision of legitimate knowledge and culture, one that on the process of enfranchising one group’s cultural capital disenfranchises another’s. (p. 171)

Yet, according to Apple (Citation2012), the carrying out of selective tradition is conducted by specific groups within the society that has created the textbooks. Apple (Citation2012) questioned whose selection, knowledge and interests are embedded in the textbooks, and this idea led to the analysis of unequal relations of power and dominance (p. 179).

Selective tradition in textbooks is commonly found in language textbooks. Thus, it can be expected that the Japanese language textbooks for Korean students will demonstrate a high degree of content selection. Therefore, it is essential to analyse the different ideologies presented in the Japanese language textbooks for both the Korean and Japanese students and compare them.

A colonial education curriculum often involves asserting control over another nation, and can play an important role in achieving the colonialists’ goals. According to Ashcroft et al. (Citation1995), education is part of the foundation of colonialist power and is often used as a means of accomplishing imperialism. A salient feature of Japanese colonisation is the use of the Japanese language as a tool to achieve subjugation of the colonised as well as the promotion of “the colonial dominant ideology” (Myers et al., Citation1984, p. 96). The Japanese government restricted educational opportunities for the colonised as one way to maintain power, since they regarded the education of indigenous populations as an obstruction to colonial power (Myers et al., Citation1984, pp. 375–376). Moreover, the colonial education curriculum often created or reinforced imbalanced power relations between the coloniser and the colonised (Phasha et al., Citation2017; Kim; Sun-jeon et al., Citation2014; Jeong Tae-jun, Citation2005). Okoth (Citation2012) stated that colonial education was projected “to suit the needs of the colonisers rather than those of the colonised” (p. 135). Published textbooks for the colonised often excluded certain subjects, such as local history and geography, serving to marginalise the colonised groups while prioritising the colonising group.

3. Data analysis

For analysis, representative texts and visual images were chosen based on the research questions (see p. 4) and analysed according to the theories of critical image analysis and critical discourse analysis. Ten Japanese language textbooks were chosen, based on similar teaching level, appropriateness and publisher. Not all visual images and texts could be analysed, as the ten language textbooks comprised a large corpus of texts, and a decision was made to limit the amount of data to be analysed for effective textual analysis (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2003).

After this general analysis, a more in-depth CDA (Fairclough, Citation2003, Citation2010) was conducted, and Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation1996, Citation2006) methodology was applied to the visual images. In analysing the texts, this study investigated particularly the lexical, grammatical and generic levels of analysis in order to reveal the underlying dominant ideologies. The texts and visual images were analysed together, as this provided stronger and richer analytical findings.

Use of CDA has not been limited to just English or Western languages and texts; scholars such as Luke (Citation2018), Dong-bae (Citation2000), and Liu (Citation2003) have shown CDA’s effectiveness in discovering underlying ideologies and hegemony by analysing texts in other language groups. Although CDA has mostly been applied in the European context (to discover social problems within English and Western language contexts), the Korean-language study conducted by Lee Dong-bae (Citation2000) used CDA to conduct an analysis of texts, and was able to discover the underlying ideologies and values embedded in Korean language textbooks. This study was able to show how CDA could be utilised to analyse Japanese language textbooks.

VIA is also a key tool used in this study, as visual images effectively support the meaning presented in the language they accompany (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012, p. 100). The visual images used in the textbooks are not separated from the text—they complement the teaching material, and so VIA plays an important role in creating meaning in the text. Although the usefulness of VIA cannot be disputed, its use in addressing key aspects of visual images in the field of critical discourse studies has so far been ignored to a certain degree.

With regard to the visual images, the following components were analysed: “ideational metafunction” (vectors—narrative relationship and establishing possible verbs from image, no vectors—conceptual process, no stressing objects, fixed idea), “interpersonal metafunction” (relationship between represented participants and viewers—offer or demand, gazing pose or gazing-off pose, looking up or down, the size of the frame, close or long shot, frontal or oblique angle, high or low modality), and “textural metafunction” (top or bottom, left or right, centre or margin, salience—size, colour, tone and foreground). Thereafter, each data set was further reduced by applying the CDA and VIA questions: “Is there rewording or overwording?”; “Are there any connotation words?”; “What metaphors are used?”; “Is agency excluded or included?”; “Is there a direct vector or no vector?”; “Is there an ‘offer image’ or a ‘demand image’?”; “Is the represented participant gazing up or down?”; and so on.

Overall, the data was analysed in accordance with the principles of CDA and VIA to investigate the presence of different ideologies in each textbook. Moreover, the texts and visual images from different textbooks were ultimately compared, to find what different ideologies had been embedded in the Japanese language textbooks used in Korean students.

There were three findings, which are further explored below: the depiction of physical labour; emphasis on Japanese nationalism with an Emperor-centred ideology; and the encouragement of playing war-like games and drills. These three themes were present in the Japanese language textbooks for Korean students but absent in those for Japanese students.

4. Work hard at physical labour

The Japanese education policy applied to the colonized Koreans was reformed in the beginning of the Japanese colonial era, in order to more closely mirror the Japanese education system. However, in reality, the content taught and the aims of Japanese education remained the same. For example, the school curriculum was used to train Koreans to become faithful and subordinate citizens to fulfil the aims of the Japanese colonial policy, including exploitation of workers and child labour (Yuh, Citation2010, p. 127). The policy continued to focus on teaching Koreans the national language (Japanese), as well as effectively forming them into faithful “low-class labourers”.

In order to replenish the ranks of labourers needed to expand colonial industry in the 1930s, the number of Japanese schools in Korea (the Japanese educational institutions called Botonghakgyo) rapidly increased (Choi Be-geun, Citation2007). Oh Seong-cheol (Citation2005) claimed that as a means to reinforce colonial industrialisation, expansion of Japanese schools took place. Kang Jun-man (Citation2008) also asserted that the expansion of Japanese schools in Korea was directly correlated with the Japanese capitalists’ need to train more manual workers. When the Japanese capitalists established their factories in Korea, they needed many manual labourers, who were able to perform repetitive tasks and who could speak Japanese. In other words, the Japanese schools were training institutions for manual labourers, in order to achieve the aims of Japanese capitalism.

Both Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, 1915, 1930, 1931, for Korean students) and Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho,Footnote3 Citation1935, Citation1938, for Japanese students) emphasised the need for diligence and unselfishness, yet each textbook also promoted different moralities. For example, Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1935, Citation1938) generally introduced the importance of kindness, while Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915, Citation1930, Citation1931) emphasised hard work, and helping adults (Park Je-hong, Citation2011).

It can be inferred from these differences that qualities, such as working hard and helping adults, were promoted to form model colonised citizens. By accentuating such qualities, the Japanese language textbooks reveal Japan’s colonial’s interests.

Regarding life at work, emphasis of physical labour was evident in much of Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon, whereas Shougakutokuhon contained only a few units, which portrayed professional jobs, such as car engineer and dentist. The specific content focused on labour is as follows:

provides the content that portrays themes of physical labour within the textbooks, Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915, Citation1930, Citation1931) and Shotou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1939) and Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1938; Citation1935). As can be seen, the topic of work appeared in many stories in Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915, Citation1930, Citation1931) and Shotou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1938) for Korean students. These stories tended to portray physical labour that does not require much skill, such as picking chestnuts, feeding the chicks, catching pine caterpillars, and picking up stones, and also included lower-class jobs, such as the work of farmers and shop keepers. In contrast, although Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1935, Citation1938) still contained stories regarding work, those stories focused on professional occupations, such as a mechanic in “The car” and a dentist in “The tooth”.

Table 1. The texts and images that emphasise labour

Throughout Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, 1915; Citation1930; Citation1931) and Shotou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1939), there were many expressions that instructed Korean students to move subserviently, and which promoted working hard. Below is an example from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) that presented the importance of hard work and physical labour, which will be compared with an example from Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917b). I have chosen these excerpts because they demonstrate the relative significance given to physical labour in the books for Korean students. These two stories were selected as examples of how the content and visual images aimed at the Korean and Japanese students were different.

Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2–3 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915, pp. 6–7) approached the theme of science by highlighting physical labour in a story “Chestnutting (クリヒロイ)”:

ミナサン, ゴラン ナサイ, クリ ガ タクサン オチテ イマス。

Everyone, look over here. [You can see] many chestnuts are on the ground.

サア, ミンナ デ イッショニ ヒロイマショウ。

Everyone, let’s collect the chestnuts together.

ソコ ニモ オチテ イマス。

[You can see] chestnuts over there, too.

ココ ニモ オチテ イマス。

[You can find] chestnuts here, too.

タクサン ヒロイマシタ。

[We] collected a lot of [chestnuts].

ウチ エ カエッタラ, オトウサン ヤ オカアサン ニ アゲマショウ。

When [we] return home, let’s give [the chestnuts] to father and mother.

オトウト ニモ, イモウト ニモ, 分ケテ ヤリマショウ。

Let’s share [the chestnuts] with [your] little brother and sister.

This story is set in a forest, where many chestnuts are on the ground. It focuses on the gathering of the chestnuts and dividing them between family members. The story uses word and sentence repetition, using the words “everyone”, “collect” and “chestnuts”, giving emphasis to the title. Homogenising nouns and pronouns, such as “everyone” (lines 1 and 2), “us” in “let’s” (lines 2 and 6), and “we” (lines 5 and 6), are used to stimulate the reader’s participation and to stress the responsibility of gathering chestnuts for the family. This text imposes an adult ideology on students, to encourage gathering chestnuts (lines 2 and 5) as everybody’s role, as well as explaining the reason for gathering chestnuts—to share chestnuts with family members (lines 6 and 7). The writer repeated synonymous phrases three times in lines 1, 3 and 4. The story focuses the reader’s attention on concentrating and looking for the chestnuts around them by using phrases such as “look over here”, “(You can see) chestnuts over there, too” and “(You can find) chestnuts here, too”. Moreover, synonymous phrases are also found in lines 6 and 7—“let’s give (the chestnuts) to father and mother” and “Let’s share (the chestnuts) with (your) little brother and sister”, in order to explain the purpose of picking up chestnuts. In the suggestive structure “let’s” in line 2, 6 and 7, the generic pronoun “us” in “let’s” refers to all Korean students. Therefore, the writer of the textbook possibly intended for this to incorporate all the people of the colonised. However, the reason as to why everybody is involved in collecting chestnuts is omitted (chestnuts are usually a staple food only in times of famine). This story may promote a sense of group responsibility in the reader.

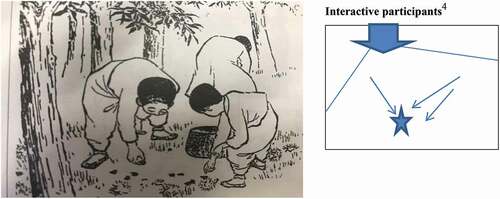

In , the children gathering chestnuts in the woods are indicated to be Korean, as they are depicted wearing lower-class Korean clothes and straw shoes. In the image, three boys are looking down and picking chestnuts, and all have similar postures, bending forward and concentrating on their actions, highlighting to the readers that the three boys are working hard. Additionally, the boys occupy themselves in picking the chestnuts and look only at the chestnuts, seemingly avoiding interaction with each other.

Figure 1. Chestnutting 1 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915, p. 6)

The image of the figure or object in the foreground is often considered more important than what appears in the background (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006), while figures or objects of larger size are given higher salience than those of a smaller size (Painter et al., Citation2013). In this case, in comparison with the images from Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917a) (see below), the tree and the chestnut burrs () are not as important as the working boys—they are emphasised by having a large space and size in the image. The chestnut burrs are small, so it is hard to recognise that the three boys are picking up chestnuts until the text is read. Presenting the three boys at a short distance from the reader could increase their individuality, as more of their appearance is discernible. In , the chestnuts on the ground are in a long shot (compared to ), which implies objectivity, separation and distance, defined by Kress and Van Leeuwen (Citation2006) as an “imaginary relation” (p. 126). In this case, the image of chestnuts suggests no relation or connection with the viewer, and thus means that the chestnuts are not the significant object in .

Figure 2. Chestnutting 2 (Monbusho, Citation1917a, p. 21)

Figure 3. Chestnutting 3 (Monbusho, Citation1917a, p. 21)

The image highlights the three boys by placing them in a centred position. By presenting a close shot of the three boys (), a closer connection with the viewer is suggested, inviting the reader to gather chestnuts as well, as clearly stated in line 2. Moreover, the three boys are looking obliquely out of the frame, the object of the viewer’s gaze and their eyes (vectors) focus on the chestnuts. The range of possible interpretations is not very complicated, as strong downward directionality of the vectors formed by the three boys emphasises their actions of chestnutting.

The following story is from Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917a). It has the same title as the story from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915), but the content and visual images are very different.

Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon 2–9 (Monbusho, Citation1917a, pp. 20–21) includes the theme of science in a story called “Chestnutting (クリヒロヒ)”:

「コノ 山 ニハ, クリ ノ 木 ガ タクサン アリマス。

There are many chestnut trees on this mountain.

ユフベ カゼ ガ フイタ カラ, キツト クリ ガ オチテ ヰマス。

Surely there should be many chestnuts [on the ground of the mountain] as it was windy last night.

サガシテ ミマセウ。」

Let’s try to find [them].

「モウ 人 ガ ヒロツタ ノ カ, サツパリ アリマセン。」

Other people must have already picked [them] up, [we] cannot find any chestnuts.

「ソレ デハ ムカフ ニ 大キナ 木ガ アリマス カラ, アノ 木 ノ 下 ヘ イツテミマセウ。」

Since there is a big tree over there, let’s try to go look under that [chestnut] tree.

(my translation)

This story is set after a windy night, which has led a number of chestnuts to fall to the ground on a mountain (lines 1 and 2). Line 3 invites the reader to search for chestnuts and lines 4 and 5 suggest looking in different areas to find more chestnuts after other people have taken the rest. Using the pronoun “somebody” in line 4 also conveys that the action of picking up chestnuts was completed by someone. By using the verbs “find” and “look” in line 3, 4 and 5, the story unfolds the interesting topic of finding chestnuts. The modal verb “must” in line 4 carries an obligatory high modality, which shows the need for things to be a certain way.

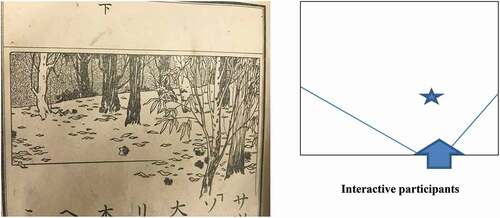

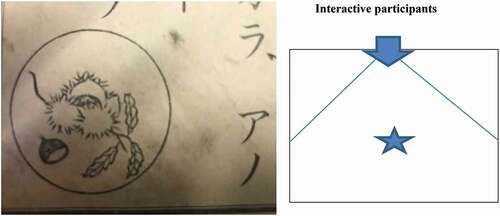

shows many trees, implied to be chestnut trees from line 1 of the text. In , the large image of a chestnut burr in the centre indicates its importance, as it supports the understanding of the form of a chestnut burr.

In visual images, the distance between the viewers and the participants (called “close” or “long” shot) represents the degree of intimacy. A “close shot” implies that the participants are closer to the viewer, implying an intimate social distance, while a “long shot” shows that the participants are maintaining more distance from the viewer, suggesting no, or distant, social relationships (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006). In this case, shows a part of the mountain and is accompanied by a close shot of chestnut burrs (), making sure that the student is aware of what a chestnut looks like, and the large image of chestnuts in the centre of a circle implies their importance as it matches the contents of the text. The close shot of the chestnut burrs () may also promote intimacy and suggest a closer relation and connection to the viewer. The potential meaning of the close shot also articulates the viewer’s attention and highlights the image’s importance.

Comparing the two texts, it is evident that they are quite different. For example, in the Korean text, by using the collective pronoun “everyone” two times, along with the pronoun “you”, the writers of the textbook strongly encourage everybody to pick up chestnuts together. While the Japanese text also uses repetition of the generic pronoun “us” in “let’s”, the author suggests finding chestnuts and depicts it as a game.

In order to equate Koreans with physical labourers, the colonial curriculum even uses the topic of natural science to teach a work ethic (Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon, Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915). The visual image and the texts attempt to emphasise the importance of labour and of being good colonial subjects in the Korean textbooks, whereas the visual images and the texts from the Japanese textbook emphasise finding and recognising chestnuts. In , for example, the chestnut burrs are located at the centre, and the large size of the image represents its importance as a depictive meaning. In comparison, in , the working boys are a much larger size than the chestnuts—there is “a hierarchy of importance among elements” to engage the “viewers’ attention” with the working boys (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006, p. 202). Additionally, while the text for the Korean students focuses on everyone being involved in a single activity, the text for the Japanese students mainly focuses on the description of the chestnuts that have fallen on the mountain.

Using framing around an image not only separates the including and excluding image, but also helps bring the reader’s attention to the framed objects (Serafini, Citation2014, pp. 65–66). Serafini (Citation2014) stated that borders can be established as a frame in visual images, as they draw the interest of the viewer to a particular part of the image, and insert the image into a particular context. As a result, the framing around the chestnuts in draws the reader’s attention to what is within the frame and also allows for the students to observe the details of the object. Compared to the image of the chestnuts () from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915), the chestnuts in are very clearly indicated, giving the impression that the chestnuts are the main focus of the text. The separation of the image of the chestnuts through the use of a frame in emphasises their importance, compared to , which has no frame.

Although both stories refer to gathering chestnuts and share the title “Chestnutting”, the texts and visual images are very different. The gathering of chestnuts is used as a symbolic image of working hard in , whereas this is not implied in . Line 2 of the Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) story has the lines “Everyone, let’s gather them all together”, while line 3 in Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon 2 (Monbusho, Citation1917a) has “Let’s look for them”. In these two lines, “them” refers to the chestnuts both times. To compare, in Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915), the action of “gathering chestnuts” applies to all people—“everyone” and “all together”. This line encourages students to gather and involve themselves in this activity. However, Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon 2 (Monbusho, Citation1917a), stresses the observation of or searching for the chestnuts, and the physical presentation of work is deliberately excluded.

Overall, it can be interpreted that the colonial language textbooks exhibited discrimination towards Koreans, depicting them as being physical workers and second-class students.

5. Japanese nationalism

The aim of the Japanese education system was to reconstruct the colonised as obedient citizens and subjects faithful to the Japanese Emperor (Lee Dong-bae, Citation2012; Park Jang-gyeong et al., Citation2014). In the initial stages of the Japanese colonial era, Japan emphasised their dominance through the use of their colonial political powers to control the Korean people effectively. This involved systematic attempts to restructure cultural identity, values and ideologies through curricular and educational reforms, and applied particularly to the textbooks for elementary school students compiled by Joseonchongdogbu (the Japanese Governor-General of Korea) (Heo Jae-young, Citation2009). The textbooks included details about the Japanese Emperor in order to emphasise Japanese nationalism, as Japan needed to train and raise the consciousness of the colonised as subjects of the Empire of Japan for the stabilisation of Japanese rule (Nakabayashi, Citation2015). According to Nakabayashi (Citation2015), this consciousness-raising took the form of assimilation, and Japan enforced “assimilation training” on Korean students (p. 10). Under the ideological basis of the Japanese colonial policy of assimilation, Japanese education aimed to educate the colonised, not only by adopting the Japanese language and culture, but also by establishing the Japanese Empire and achieving the subordination of the colonised for imperial Japan.

The Japanese language textbooks were organised differently for Korean and Japanese students, and the Japanese language curriculum for Korean students related more to the promotion of Japanese colonial ideology. For example, only Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) introduced content relating to the Japanese Emperor and flag. These significant differences may reveal that Japanese language textbooks were used to teach Japanese history, and also as a means of controlling the Korean school curriculum by highlighting Japanese ideologies (such as the Japanese Emperor-centric ideology and the Japanese flag) in order for Koreans to accept an Emperor-centred ideology and Japanese dominance. Lee Dong-bae (Citation2000), in his analysis of Korean language textbooks from the Japanese colonial era, found that Korean history, historical figures and Korea’s famous heroes were deliberately omitted from textbooks, and that colonial education was used as a tool for the indoctrination of Japanese colonialism and ideology.

The Japanese Emperors’ birthday was also presented in the books as a Japanese national day, when people flew the Japanese flag to celebrate his birthday. This indicates that the lower primary Korean students were taught to worship the Emperor as loyal subjects of Japan, and to love the Japanese flag as their own national flag, with an assumption that worshiping the Japanese Emperor would become a normal practice, to be carried out without resistance. The young Korean students may have accepted that they were part of the Japanese collective identity.

As shown in , content relating to Japanese nationalism was greater in Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) than in Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917a). Additionally, according to the table, the Japanese Emperor, the Japanese flag and national flowers were introduced in Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915).

Table 2. Japanese nationalism with Emperor-centred ideology (E) & pro-Japanese ideology (P)

The stories “New Year’s Day” from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotoku hon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) and Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917a) both had the same title, but had different images and contents. The story “New Year’s Day” from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) introduces the various decorations that Japanese people used to adorn their houses, as well as the practice of putting up the Japanese flag at each home’s front gate, while also highlighting powerful Japanese nationalism. To compare, the story “New Year’s Day” from Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917a) only showed people’s activities on New Year’s Day, and the visual image with the story presented how and what people do to celebrate New Year’s Day. Both “New Year’s Day” stories included decorating the house on New Year’s Day. However, different items are described in order to promote different ideas.

Under the rule of Japanese imperialism, the textbook Kokugotokuhon was introduced to teach Korean students the Japanese language (Kim Sun-jeon et al., Citation2012). It contained Japanese-centric ideology and omitted Korean themes, such as Korea’s great heroes and the JoseonFootnote4 kingdom. For example, Kokugotokuhon contained many stories that related to Japanese nationalism: “The flag of Japan”, “His Royal Highness, the Emperor of Japan”, “The Empire of Japan”, “The Meiji Emperor”, “Japanese apricot flowers and cherry blossoms” and “The Japanese Emperor’s birthday”. These strongly promoted Japanese nationalism by depicting Japanese flags and flowers, and promoting the worship of the Japanese Emperor. Throughout Kokugotokuhon, a Japan-centric perspective was highlighted by presenting the Japanese Emperor, but Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Monbusho, Citation1917a) (for Japanese students) did not include any texts about the Japanese Emperor. These significant differences may reveal the Japan-centric perspective, whereby the Japanese Emperor and Japanese nationalism were taught only to Korean students in order to shape them into Japanese colonised citizens. Learning about the Japan-centric perspective and the Japanese Emperor was not necessary for the Japanese students—they were naturally expected to already possess this knowledge.

The Japanese Emperor is depicted as the provider of love and kindness, and the Korean students are depicted as the beneficiaries of this love and kindness in the textbooks for Korean students. The Emperor’s love and kindness are described as something akin to what parents feel for their children and, by comparing it to parents’ love, the textbook writers were trying to influence the students to appreciate the Emperor’s love by emphasising it, along with demonstrating appreciation of parents’ sacrifice and love for their children. Their duty as the Emperor’s “children” was to be thankful to the Emperor, similar to how children were expected to be thankful to their parents for providing for them. The story “His Royal Highness the Emperor (of Japan)” demonstrates how the Japanese Emperor-centred ideology promoted the ideal image of the Japanese Emperor, by describing his kindness. Three stories about Japanese Emperors were included in Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915): “His Royal Highness the Emperor (of Japan)”, “The Meiji Emperor”, and “Tenchousetsu”. These stories gave an impression to the students of the need for respect and obedience towards the Emperor.

“The Meiji Emperor” also introduced the idea of the Meiji Emperor’s kindness and the need to worship him. While the colonised had little knowledge or experience of him and may not have received any benefits from the Meiji Emperor’s kindness, the story “The Meiji Emperor” addresses and highlights the Meiji Emperor’s kindness, in order to instil the Japanese Emperor-centred ideology in the colonised students’ minds. The Meiji Emperor governed Japan for 45 years and made Japan a wealthy and powerful nation (Klatt, Citation2006, p. 31). The story “The Meiji Emperor” encouraged readers to be thankful for the Meiji Emperor’s kindness, and prompted the Korean students to feel that a sense of gratitude towards the Meiji Emperor was natural, but the reason for Korean students to celebrate him was omitted. The colonisers tried to negate the Korean national identity and spirit by emphasising feelings of admiration towards the Japanese Emperor, so that a sense of identity as Japanese citizens could be promoted instead.

“Tenchousetsu” from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1915) also highlighted the Japanese Emperor-centred ideology and clearly displays how Korean students were invited to worship the Japanese Emperor (for example, by performing a ceremony and singing KimigayoFootnote5 at school). In the story, the school takes the lead in the celebration, and the students are therefore compelled to celebrate the Emperor’s birthday, as well as to worship the Emperor as a god, shown as Kimigayo. These kinds of school activities aimed to strengthen the identification of Koreans with the national ideals of Japan, and also worked as tools to inspire Koreans to support Japanese nationalism and imperialism (Jeong Tae-jun, Citation2005). According to Jeong Tae-jun (Citation2005), the main aim of teaching Japanese imperialism in the colonial textbooks was “to indoctrinate a colonial ideology” (p. 3). Jeong Tae-jun (Citation2005) also claimed that Korean students were involved in ceremonies (such as shrine festivals and worshiping the Japanese Emperor) as a tool to indoctrinate Koreans with Japanese imperialism. The text “Tenchousetsu” emphasised the role of students on the Japanese Emperor’s birthday. However, it did not explain that the Koreans were celebrating the Japanese Emperor’s birthday only due to their being colonised by Japan.

6. Making soldiers

By the late 1930s, overall educational content focused on military education—this had become the main purpose of the school curriculum (Cheol & Sun-jeon, Citation2012, p. 337; Peng & Chu, Citation2017). Throughout the Great Depression, Japan had been mired in the economic crisis, and in this period, it started an aggressive war (the second Sino-Japanese War) in 1937, and militarism became increasingly prominent. For the military, acclaim came from success. Therefore, continual military and imperial expansion was prioritised, and this exerted an influence on the education provided for the colonised.

In order to expand the aggressive war towards neighbouring Asian countries, such as China, Korea was used as an important military supply base for Japanese military operations (Kim Sun-jeon et al., Citation2015; Kim; Jeong-ha, Citation2013). In order to reinforce Japan’s security throughout the East Asia region, Korea was utilised to satisfy military needs. Therefore, The Japanese government used political and military coercion to achieve control and ethnic supremacy over the Koreans. The school curriculum was developed to encourage the acceptance of the subjugated role of the colonised citizens.

There were no texts or images that referred to war in the textbooks for the Japanese students—only Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1930) and Shotou Kokugotokuhon (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1939, Citation1940) included pro-war material, used to achieve ideological control and to benefit Japan’s aims in the war. In order to create soldiers from the colonised, the Japanese language textbooks for Korean students included content where the children practised war-like drills and war games. The textbooks were used as a tool to promote the ruling class’s interests—for example, Korean students were given military exercises as “recreation” (Kim Sun-jeon et al., Citation2012). When the Japanese textbook introduced the text “Gymnastic games” (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1930), the gymnastic exercises were performed like a military march and the students marched and chanted according to the team leader’s orders, mimicking a military drill.

Military practices are intended for soldiers, not children, yet they appeared in the following story, “Gymnastics games”, chosen from Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1930). The story portrays students’ roles and the authority of teachers, in order to impress the dominant ideology on the colonised students. This story signifies the school culture of the time, and shows the relations between teachers and students.

Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2–3 (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1930, pp. 6–8) covers the theme of school life and play, introducing school gymnastic games like military drills in this story, “Gymnastic games (タイソウゴツコ)”:

「タイソウゴツコ ヲ シマシヨウ。」

“Let’s play the gymnastics game.”

「キ ヲ ツケ。」

“Attention.”

「マエ ニ ナラエ。」

“Extend your arms to the front.”

「ナオレ。」

“Put your arms down!”

「マエ ヘ ススメ。」

“Go forwards.”

「一 ニ。 一 ニ。」

“One, two, one, two.”

「カケアシ ススメ。」

“Run forward.”

「一 ニ。 一 ニ。」

“One, two, one, two.”

「ゼンタイ トマレ。」

“Halt.”

「ヤスメ。」

“At ease!”

「コンド ハ, ダレ ガ 先生 ニ ナリマス カ。」

“Now, who wants to be the teacher (the person who is giving instructions)?”

(my translation)

In this story, the students perform their movements in absolute obedience under the teacher’s orders, just as if they are in military ranks. It is only possible for the students to play this game (which seems reminiscent of a military drill) if they accept and follow instructions. The students (taking the role of instructor) can also have a turn at being in charge. Thus, this story reinforces adult ideology, in order to develop good morality in the Korean students and prepare them to be useful in war. The use of imperative forms in lines 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9 and 10 can be seen as issuing commands, and helps to depict the role and authority of the teacher, echoing the dominant ideology. In line 1, 「-マシヨウ」, meaning “let’s” in English, is used to initiate an interaction with the Korean readers. The use of a request or offering, 「-マシヨウ」, also depicts the positive aspects of the relationships among the students, in order to encourage the actions (“play”) as an interesting game. Lines 2 to 10 display a distinguishing use of military terms—the students move and obey at the teacher’s command; likewise, lower-class soldiers obey higher-class officials in the army. This explains the hegemony and power relations between the high-ranking and the low-ranking soldiers in the army, as well as the relations between the teachers and students—the authority of the teacher is depicted as being the same as that of a high-ranking soldier. This story “Play gymnastics” is related to training Korean students as soldiers. The Japanese government promulgated preparation for combat (Hall, Citation2014).

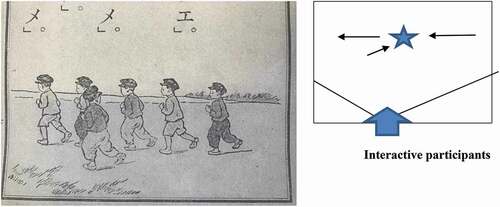

In , the students are introduced as soldiers who are in military training; they move in line and have the same posture. indicates how Korean students (their clothes indicate them to be Korean) played gymnastic games as a form of military training. One student who stands outside of the line is the leader of the group and he watches and orders the other students. None of the leader or the five students have eye contact with the viewer, denoting that the viewer is invited to watch—not in a way that encourages a personal relationship, but as an observer: they become an “offer” (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006, p. 148). The elements placed in the background are less important than the elements in the foreground (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012, p. 56). In this case, the leader is important—the boy placed at the front in is slightly larger than the other boys.

Figure 4. Gymnastic games (Joseonchongdogbu, Citation1930, p. 7)

All five boys are performing the same actions (running in a straight line and looking ahead), and their leader also has the same posture but is watching the five boys—this kind of image is usually seen in military camps. The vector is made by the boys and leads the reader’s eyes from the boy in front (the leader) to the other boys’ actions. Furthermore, the poses of the boys are highlighted, which shows the idea of gymnastics, as well as emphasising military training at school, as clearly stated in the text and .

In images, the length of a shot (i.e., “close shot” as against “medium shot” or “long shot”) indicates the distance between the participant and viewer, and can also represent social distance (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006, p. 124). In this case, by presenting a middle shot on the boys in , the story is positioned as a medium degree of social relation to the viewers. The angle of image indicates the social relation—the boys are located at a vertical angle from below, utilising a symbolic power on the viewer as the viewer looks up and focuses on the boys’ motion.

Military practices are intended for soldiers, not children, yet they are the theme of this story. When the Second Sino-Japanese War expanded throughout the Pacific, schools became a place to train Korean students as soldiers (Jeong Hye-gyeong, Citation2010) while Korean students were being taught to worship the Emperor as loyal subjects of Japan (Kim Jin-suk, Citation2012). The gymnastics exercises performed by Japan’s loyal Korean subjects (which were part of the Japanese military tradition, probably adopted from Western practice) were an important element in cultivating national spirit. Furthermore, Japan focused on these gymnastics exercises at school to cultivate the ideology of the Japanese Empire to the colonised (Jung Hee-jun, Citation2009, p. 21). This is evidence that the Japanese textbooks were used to raise Korean students to be battle-ready, and exposed Japan’s intent to train Korean students as soldiers (Jeong Hye-gyeong, Citation2010). The school system and curriculum for Koreans were highly significant in the Japanese prosecution of the war (Yu Cheol, Citation2015; Kim; Sun-jeon et al., Citation2012; Park Gyeong-su, Citation2011) and this is made clear by the inclusion of pro-war material in the textbooks of the period, in contrast with the absence of war images in textbooks from earlier stages of the colonial era.

7. Conclusion

This study is the first to compare the different sets of textbooks published for and used by Japanese and Korean primary school students in the colonial era. As well, previous studies have not utilised both CDA and VIA for their analysis of textbooks, thereby neglecting the power of these tools being used in combination.

The differing Japanese language textbooks used by Japanese and Korean elementary students during the Japanese colonial era presented differentiated ideologies to each group. The Japanese colonial curriculum was used to promote the ruling class’s interests and served as a tool of colonialism and legitimation of Japanese colonial ideology in an attempt to assert control over students.

The different textbooks intended for use by the Korean and the Japanese people were written to achieve differing goals, with the books for Korean students aiming to support the “training” of a subjugated population. Examination of the two different sets of textbooks (for Korean and Japanese students) made it clear that the education provided to the two groups was very different—the content served as a means for discrimination between the Japanese and the Korean students.

This use of curriculum was particularly clear through three topics that were featured in the Japanese language textbooks for Korean students but which were absent from the textbooks for Japanese students.

Hard physical labour was stressed in the Japanese language textbooks for Koreans, and content regarding labour tended to involve the portrayal of physical labour that did not require much skill, such as picking chestnuts, feeding chicks, and picking up stones, or of lower-class professions, such as farmers and shop keepers. In contrast, the textbooks for Japanese students that contained themes of work focused on professional occupations, such as the job of a mechanic or a dentist. These differential ideologies reveal Japan’s colonial’s interests to form model colonised citizens.

The textbooks for Korean students also included details about the Japanese Emperor in order to emphasise Japanese nationalism, as Japan needed to train and raise the consciousness of the colonised as subjects of the Empire of Japan for the stabilisation of Japanese rule (Nakabayashi, Citation2015). It was revealed that while the textbooks for Korean students contained a great amount of content relating to Japanese nationalism (which enforced a pro-Japanese ideology as well as an Emperor-centred ideology), the textbooks for Japanese students contained less than half the amount of content relating to Japanese nationalism, and had no content that presented an Emperor-centred ideology. Therefore, the Emperor-centred ideology that was only presented to the Korean students can be seen as an attempt to cultivate them into faithful subjects to the Japanese Emperor.

Furthermore, Korean students were encouraged to practise war-like games and drills through the stories offered in the Japanese language textbooks. The textbooks for the Japanese students did not include any pro-war material, whereas war was incorporated in depictions of recreational activities for the Korean students, encouraging them to practise war-like drills and games. This pro-war ideology (which was only presented to the Korean students) aimed to manipulate the Korean people into participating in the war, reflecting Japan’s intent to train Korean students as soldiers at the time.

The results from this study suggest that differentiated ideologies, presented exclusively to Korean students through the Japanese language textbooks of the Japanese colonial era, were a means of projecting Japan’s colonial ideologies. The Japanese government wished to raise colonial subjects that would participate in hard physical work as manual labourers, be faithful subjects of the Japanese Emperor, and become soldiers for the Japanese empire.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hai suk Kim

Hai suk Kim completed her PhD study in 2019 at the University of Queensland in Australia. She has been teaching the Korean language since 2012 at the University of Queensland and completed her postdoctoral fellowship with Korean Foundation in 2021. Her study of interest includes analysis of texts and visual images of the Japanese language textbooks that were published by the Japanese government during the Japanese colonial era. Her research investigates the ideologies by an analyzing the texts and visual images of the Japanese colonial images in the Japanese language textbooks used in Korea and also compared the Japanese language textbooks used by Korean and Japanese students in order to discover the different ideologies presented in them.

Notes

1. Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon (Citation1915, Citation1930 &, Citation1931) and Shotou Kokugotokuhon (Citation1939 &, Citation1940) are the full names of two series of textbooks for Korean students. These textbooks were used in Korea for Korean primary students during the colonial period.

2. The full titles of these series of books are Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon (Citation1917a) and Shougakutokuhon (Citation1935 &, Citation1938). These textbooks were used in Japan by Japanese primary students in the same period.

3. The Japanese Education Department (Monbusho in Japanese).

4. Joseon is the official name for Korea.

5. A Japanese national song, “Kimigayo”, was sung by the teachers and students at a school-organised ceremony, and the teachers read the Imperial Rescript.

References

- Althusser, L. (2014). On the reproduction of capitalism: Ideology and ideological state Apparatuses. ( G. M. Goshgarian, Trans.) Verso.

- Apple, M. W. (2012). Knowledge, power and education: The selected works of Michael W. Apple. Routledge.

- Ashcroft, B., Griffiths, G., & Tiffin, H. (Eds.). (1995). The post-colonial studies reader. Routledge.

- Be-geun, C. (2007). Hanguk gyeongjeui saeloungil: Yeoksajeok bunseokeulobon [The way of the Korean economy: As seen in historical analysis], 50(4). Parkyoungsa.

- Cheol, Y. (2015). Physical theory for education of the nation in the Japanese colonial era focused on Japanese readerbook: Physical education, music, wartime songs ( Doctoral thesis, Chonnam National University). Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Cheol, Y., & Sun-jeon, K. (2012). Iljegangjeomgi kugeodogbone tuyoungdoen gunsagyoyuk [A military discipline revealed in textbook on Japanese in Japanese imperialism], The Japanese Literature, 56, 335–19. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2003). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Dong-bae, L. (2000). The ideological construction of culture in Korean language textbooks: A historical discourse analysis ( Doctoral thesis, University of Queensland). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/304567573?accountid=14723

- Dong-bae, L. (2012). Critical analysis of Japanese ideology in Korean language textbooks (1913-1938). The Education of Korean Language and Literature, 27, 107–140. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Fairclough, N. (2001). Language and power. Pearson Education.

- Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language. Longman.

- Fairclough, N. (2013). Language and power (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Gyeong-su, P. (2011). Iljemalgi kukeodogbonui gyohwalo byeonyongdoen ‘eolini’ [In the end of the Japanese colonial period, ‘Children’ were changed into edification of kukeodogbon]. Japanese Literature, 55, 547–566. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Hall, S. (2014). Imperial Japanese army intelligence in North and Central China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. Salus Journal, 2(2), 16–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3316/INFORMIT.735360026845067

- Hee-jun, J. (2009). Seupocheu Korea pantaji: Seupocheulo ilgneun hankug sahoe munhwasa [Sports Korea fantasy: Reading Korean society and culture through sports]. Gaemagowon.

- Hye-gyeong, J. (2010). Joseon cheongueoniyeo hwangguksinmini doeeola [To Joseon youth, become citizens of Japanese Empire]. Seohaemunjib.

- Hye-lyeon, K. (2011). Ilje gangjeomgi Joseoneogwa gyogwaseowa Joseonin [Korean textbooks and Korean people during the Japanese colonial era]. Yeoglag.

- Jae-cheol, J. (2009). Comparative analysis in all textbooks from the colonial era (M. Lee, Ed.). The Journal of Education Studies, 31(2), 227–243. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Jae-young, H. (2009). Iljegangjeomgi gyogwaseo jeongchaekgwa Joseoneogwa gyogwaseo [The textbook policy and Joseon language textbooks during the Japanese occupation]. Gyeongjin.

- Jang-gyeong, P., Hyun-suk, K., & Sun-jeon, K. (2014). Joseonchongdogbu pyeonchan 1923-1924 botonghakgyo kugeodogbon je2gi: hangeulbeonyeog [The Japanese language textbooks published by the Japanese Governor-General of Korea in 1923-1924 the second period of Joseon Education Ordinance: Hangul translation]. J&C.

- Je-hong, P. (2011). Ilje sigminji sidaeui chabyeol gyoyukeul tongha sigminji eolini mandeulgi: Je 3 cha gonglibhakgyo gugeo gyogwaseo jungsimeulo [Making a colonial child through discriminatory education under the Japanese colonial period: Focusing on the tertiary common school national language textbooks] Journal of Japanese Language Education Association, 58, 231–245. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Je-hong, P., & Sun-jeon, K. (2016). Iljeui umihwa gyoyukgwa yeoksa gyogwaseo: Je1cha Joseon gyoyuglyeong sigi Joseonchongdogbu pyeonchan botonghakgyoyong gyogwaseoleul jungsimeulo [Japanese education of making the Korean the ignorant and history textbook: Focusing on textbook for primary schools compiled by the Japanese Governor-General of Korea in the period of ‘1Cha Joseon Education Law’. Journal of Japanese Language Education Association, 78(12), 183–197. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002187300

- Jeong-ha, K. (2013). Korean primary school music education during Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945. ( Doctoral thesis, The Griffith University). Retrieved from https://www120.secure.griffith.edu.au/rch/file/1cdd22c0-b3ee-459f-b984-85f2aba68d3a/1/Kim_2013_02Thesis.pdf

- Ji-hye, S. (2008). A study of the image of boys in textbook illustrations under the rule of Japanese imperialism ( Masters thesis, Ewha Women University). Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Jin-ho, K. (2011). Kugeo gyogwaseoui hyeongseonggwa ilje sigminjuui: Kukeodogbongwa Joseoneodogboneul jungsimeulo [The formation of Korean textbooks and Japanese colonialism: Focusing on the Japanese language textbooks (1907) and the Korean language textbooks (1907)]. The Journal of Modern Novel Studies, 46, 65–99. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Jin-ho, K., Sin-jung, K., Ye-ni, K., Kum-dan, B., & Seong-cheol, O. (2007). Gukeo gyogwaseowa gukga ideollogi [Korean language textbooks and national ideologies]. Nurim Press.

- Jin-o, K. (2011). Iljewa Joseon gyoyukjeongchak: Joseon gyoyuklyeongeul jungsimeulo [Japanese colonial education in Korea: Focus on the Korean Educational Ordinance during the Japanese colonial period]. Journal of Japanese Culture, 50, 255–272. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Jin-suk, K. (2012). Ilje gangjeomgibuteo je 1 cha gyoyukgwajeonggi gyoyukgwajeong munseo chegye bunseok: Chonglongwa gyogwaui bunhwawa doklib [Analysis of the document system of the first education and periodical curriculum since Japanese colonial rule: Differentiation and independence of general theory and subject]. The Journal of Korean Education History Studies, 34(1), 27–55. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Jun-man, K. (2008). Hanguk geundaesa sanchaek 8: Manju sabyeoneseo sinsachambaekkaji [Korean modern history walk: From the Manchurian Incident to shrine worship]. Inmulgwasasangsa.

- Klatt, O. (2006). Reiki systems of the world: One heart – Many beats (C. M. Grimm, Trans.). Lotus Press.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (1996). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Liu, Y. (2003). The cultural knowledge and ideology in Chinese language textbooks: A critical discourse anaysis ( Doctoral thesis, The University of Queensland). Retrieved from https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:106545

- Luke, A. (2018). Critical literacy, schooling, and social justice: The selected works of Allan Luke. Routledge.

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. Sage.

- Mi-kyong, J. (2013). Ilje gangjeomgi chodeung Sushinseo wa Eum-agseoe seosadoen seongsang [Characters of gender roles in Sushinseo and music textbooks for elementary school students during the Japanese colonial era]. Japanese Language and Literature, 59(1), 389–407. Retrieved from https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001797

- Myers, R., Peattie, M., & Chen, C. (1984). The Japanese colonial empire, 1895-1945. Princeton University Press.

- Nakabayashi, H. (2015). Joseonchongdogbuui gyoyukjeongchaeggwa donghwajuuiui byeoncheon [The Japanese Governor-General of Korea’s education policy and transition of assimilation] ( Doctoral thesis, Yonsei University). Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Okoth, P. G. (2012). The imperial curriculum: Racial images and education in the British colonial experience (J. A. Mangan, Ed.). Routledge.

- Painter, C., Martin, J. R., & Unsworth, L. (2013). Reading visual narratives: Image analysis of children’s picture books. Equinox Publishing.

- Peng, H., & Chu, J. (2017). Japan’s colonial policies – From national assimilation to the kominka movement: A comparative study of primary education in Taiwan and Korea (1937-1945). Paedagogica Historica, 53(4), 441–459. Retrieved from https://www-tandfonline-com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/doi/pdf/ https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2016.1276201 ?needAccess=true

- Pennycook, A. (2016). Politics, power relationships and ELT from: The Routledge handbook of English language teaching (G. Hall, Ed.). Routledge.

- Phasha, N., Mahlo, D., & Sefa Dei, G. J. (Eds.). (2017). Inclusive education in African contexts: A critical reader. Sense Publishers.

- Seong-cheol, O. (2005). Singminji chodeung gyoyukei hyeongseong [The formation of Japanese colonial primary education.] (2nd ed.). Gyoguk Gwahaksa.

- Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: An introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. Teachers College Press.

- Sheldon, L. E. (1988). Evaluating ELT textbooks and materials. The ELT Journal, 42 (4), 237–246. Retrieved from https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/42.4.237

- Soo-bin, P. (2011). Japanese imperialism and “Joseoneodokbon”: A study on the changes of Japanese colonial policy at the 4th and 7th educational law period “Joseoneodokbon”. The Society of Korean Educational Study Review, 36 (1), 467–492. Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Sun-jeon, K., Gyeong-su, P., Hui-young, S., Je-hong, P., Mi-gyeong, J., Seo-eun, K., & Cheol, Y. (2015). Jegugui jeonsigayo yeongu: Gunga enkaeul jungsimeulo [The study of Empire’s war poem: Focusing on the war song Enka]. J&C.

- Sun-jeon, K., Je-hong, P., Mi-gyeong, J., Gyeong-su, P., & Hui-young, S. (2014). Botonghakgyo gugeodokbon je 3gi: Wonmunsang [National school textbooks of third reading: Original texts]. J&C.

- Sun-jeon, K., Je-hong, P., Mi-gyeong, J., Gyeong-su, P., Hui-young, S., Seo-eun, K., & Cheol, Y. (2012). Iljegangjeomgi ilboneo gyogwaseo Kukoudockboneul tonghae bon sikminji Joseon mandeulgi [Making colonial subjects for Japan during the Japanese colonial era through the analysis of Kukoudockbon]. J&C.

- Tae-jun, J. (2005). Ilje gangjeomgi Joseonui cheonhwangje sasang gyoyuk yeongu [Choseon’s imperial ideology education during Japanese imperialism] ( Doctoral thesis, Gyeongsang National University). Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Venezky, R. L. (1992). Textbooks in school and society. In P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Curriculum (pp. 436–461). Maxwell Macmillan International.

- Williams, R. (1977). Marxism and literature. Oxford University Press.

- Yoon-joo, K. (2011). A Comparative study of Jeseoneodokbon and Gugeodokbon during the Japanese colonial era: Focusing on 2nd graders textbook of the 1st Educational Law Period. The Korean Language and Literature Society, 41, 137–166. Retrieved from https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART001591328

- Young-gi, P. (2008). The orientation of children’s literature education in Korea ( Doctoral thesis, The Hankuk University of Foreign Studies). Retrieved from http://dl.nanet.go.kr/SearchDetailList.do

- Yuh, L. (2010). Contradictions in Korean colonial education. International Journal of Korean History, 15 (1), 121–150. Retrieved from https://ijkh.khistory.org/upload/pdf/15-1-5.pdfReferences

- The Japanese Governor-General of Korea (1915). Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2. Joseonchongdogbu.

- The Japanese Governor-General of Korea (1915). Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 3. Joseonchongdogbu.

- The Japanese Governor-General of Korea (1930). Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 2. Joseonchongdogbu.

- The Japanese Governor-General of Korea (1931). Hutsuugakkou Kokugotokuhon 3. Joseonchongdogbu.

- The Japanese Governor-General of Korea (1939). Shotou Kokugotokuhon 2. Joseonchongdogbu.

- The Japanese Governor-General of Korea (1940). Shotou Kokugotokuhon 3. Joseonchongdogbu.

- The Ministry of Education (1917a). Zinzyoo Shougakutokuhon 2. Monbusho.

- The Ministry of Education (1917b). Shougakutokuhon 3. Monbusho.

- The Ministry of Education (1935). Shougakutokuhon 3. Monbusho.

- The Ministry of Education (1938). Shougakutokuhon 3. Monbusho.