Abstract

The trans-contextual model (TCM) offers a heuristic-based theoretical framework to understand fifth-grade Danish schoolchildren’s motivation to participate in the 11 for Health in Denmark educational football concept, as well as their intention and behaviour to participate in vigorous physical activity (PA) in a leisure-time context. The implementation of this model framework in a validated web-based version of the 3-part TCM questionnaire battery requires transparent, qualitative cross-cultural translation and adaptation so that effectiveness of the 11 for Health concept can be evaluated in a Danish context. The focus of this translation and adaptation process was on content validity and conceptual, item, semantic, and operational equivalencies. This study consisted of three parts: (1) translation and creation of a web-based questionnaire version, (2) cognitive debriefing interviews in two independent groups of schoolchildren (ten boys and six girls, Mage = 11.65 years) and (3) observation during implementation of the questionnaire battery. Through analytical triangulation of interviews and observations, we identified four themes: considerations to be taken into account in creating the web-based questionnaire battery, adjustments needed when translating the questionnaire battery, required personal information, and response categories. Further, we identified and resolved problems with regard to the introduction of the questionnaire battery, to 23 out of 57 questions, to providing personal information, and to response categories. The translated and adapted TCM questionnaire battery seems to be suitable for 10- to 12-year-old Danish schoolchildren and shows content validity. The Danish web-based version of the TCM is now ready for large-scale testing of its psychometric properties.

Public interest statement

Motivation is an essential concept when investigating physical activity (PA) amongst schoolchildren. However, motivational processes are complex as motivational theories have similar components and overlap in the definitions and the proposed mechanisms by which these constructs affect PA behaviour. The trans-contextual model (TCM) is a common framework when investigating motivational processes and can be operationalized using a questionnaire battery. However, the questionnaire battery has not yet been translated or cross-culturally adapted into a web-based questionnaire battery appliable by 10–12-year-old Danish schoolchildren. Therefore, this study conducted and described the translation and cultural adaptation process, created a web-based TCM questionnaire battery and addressed content validity while evaluating specific equivalencies. The results support the content validity of the web-based TCM questionnaire battery, and the ability to measure the motivational processes by which schoolchildren’s autonomous motivation towards in-school football activities relates to autonomous motivation, intentions and participation in similar activities outside of school.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that children and adolescents limit the amount of time spent being sedentary and that they exercise at least an average of 60 min/day per week. The nature of this physical activity (PA) should be of moderate-to-vigorous intensity (MVPA) and mostly aerobic (Bull et al., Citation2020). However, only 26% of Danish children between 11 and 15 years of age conform to national guidelines of 60 min/day of moderate-to-high PA (Toftager & Brønd, Citation2019). Studies show that participation in informal and particularly formal leisure-time sports is effective in promoting PA and increases the chances of conforming to WHO guidelines (Madsen et al., Citation2020; Ørntoft et al., Citation2018). The evidence-based 11 for health—in Denmark concept (hereafter 11 for Health) targeting 10- to 12-year-old fifth-grade schoolchildren has been successful in increasing physical fitness, cognition, well-being, health knowledge and enjoyment (Larsen et al., Citation2021; Lind et al., Citation2018; Madsen et al., Citation2020; Ørntoft et al., Citation2018). However, a key element in the successful application of the 11 for Health concept has not been examined, namely the motivational processes underlying participation and the behavioural changes the program can potentially bring about. Motivation is an essential and complex phenomenon in relation to PA amongst children (Pannekoek et al., Citation2013). That is, motivation is energised by various psychological and socio-contextual factors, and in turn influences PA initiation and adherence (Standage et al., Citation2003; Vallerand & Losier, Citation1999). However, charging motivational processes are complex as motivational theories have similar components together with considerable overlap in the definitions and constructs and the proposed mechanisms by which these constructs affect PA behaviour (Hagger, Citation2014; Hagger & Chatzisarantis, Citation2009). The trans-contextual model (TCM) of Hagger and Chatzisarantis (Citation2009) is a common framework attempting to capture the complexity for investigating motivational processes in academic and school settings and was thus chosen for application in the 11 for Health concept (Hagger et al., Citation2003; Hagger & Chatzisarantis, Citation2009, Citation2012, Citation2016; Krustrup & Krustrup, Citation2018).

The TCM was developed to interrogate processes by which autonomous motivation toward in-school educational activities relate to autonomous motivation, intentions and participation in related activities in the out-of-school context (Hagger et al., Citation2003). To this end, the TCM draws on the well-known theories, namely self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991), and the hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Vallerand, Citation2007). To operationalize the TCM, Hagger and Hamilton (Citation2018) applied a comprehensive questionnaire battery covering 57 items that assess transfer processes of motivation for in-school activities to motivation for related activities in contexts outside of school. The course of the transfer processes is illustrated according to three central propositions occurring over time; Time point 1: perceived support for autonomous motivation predicts autonomous motivation within educational contexts; Time point 2: autonomous motivation toward activities in an educational context predicts autonomous motivation toward similar activities in an out-of-school context; Time point 3: autonomous motivation in an out-of-school context predicts future intention to engage in out-of-school activities and actual behavioural engagement. These three TCM propositions are addressed via a comprehensive TCM questionnaire battery in three parts, corresponding to the three time points. This is highlighted in and is aligned with the different sessions over the length of the 11 for Health program.

Figure 1. Hypothetical model of the trans-contextual model questionnaire battery and the 11 for health concept

Although the 3-part TCM questionnaire battery has not yet been translated or cross-culturally adapted to the Danish educational context for use within the 11 for Health concept, the model’s effect patterns have been supported by earlier cross-cultural adaptational research involving persons of different ages, and with different cultural and national backgrounds (Barkoukis et al., Citation2010; Hagger, Citation2014; Hagger et al., Citation2003, Citation2005, Citation2009; Hutmacher et al., Citation2020; Müftüler & İnce, Citation2015; Shen et al., Citation2008). In order to investigate the motivational processes during participation in the 11 for Health concept, the authors, therefore, had to translate and culturally adapt the 3-part TCM questionnaire battery into a web-based questionnaire battery to be used within the school-based 11 for Health concept.

When implementing a questionnaire in a new language and cultural context, the first step is to establish content validity (Terwee et al., Citation2018), that is, the degree to which content of the instrument adequately reflects the construct measured (Mokkink et al., Citation2010). While establishing content validity is often considered the most important in developing a questionnaire, it is challenging to assess (Terwee et al., Citation2018). Content validity is often judged by experts and representatives from the target group to ensure suitable and correct understanding (McKenna, Citation2011). However, when target group members are schoolchildren, as in the TCM questionnaire battery used within the 11 for Health concept (Krustrup, Citation2018), it is even more challenging to establish content validity (Andersen & Kjærulff, Citation2003; Devine et al., Citation2018; Omrani et al., Citation2019). In our current study, content validity therefore addresses three main areas; (1) relevance (i.e., all items should be relevant for the construct of interest within a specific population and context of use, (2) comprehensiveness (i.e., no key aspects of the construct should be missing), and in particular (3) comprehensibility (i.e., the items should be understood by respondents as intended) (Terwee et al., Citation2018). In addition, when addressing content validity in the cross‐cultural adaptation of a questionnaire, different types of equivalencies have to be emphasised, including conceptual equivalence (i.e., if a concept exists and is construed in the same way when translated), item equivalence (i.e., the extent to which a given item is an appropriate measure of the concept it is assumed to measure, in the different cultures), semantic equivalence (i.e., if the connotation is the same for speakers of different languages), and operational equivalence (i.e., if the methods used to collect the data are equally appropriate) (Regnault & Herdman, Citation2015).

Similar to previous questionnaire research applied to the 11 for Health concept, the use of the translated TCM questionnaire is planned as a web-based questionnaire (Larsen et al., Citation2021; Madsen et al., Citation2020; Ørntoft et al., Citation2018). However, web-based administration may yield slightly different results compared to paper-based versions as the web-based administration is seldomly done in a controlled setting (Austin et al., Citation2006; Donker et al., Citation2010). Therefore, content validity of the web-based TCM questionnaire must also be established (Gera et al., Citation2020; Terwee et al., Citation2018). Since the target users of the 11 for Health concept (i.e., 10- to 12-year-old schoolchildren) are not capable of translating a comprehensive English questionnaire, it is essential to involve them in other ways in the translation and adaptation process. By including this target group, we aim to minimize cultural bias and to ensure that the original intent of the measure is preserved beyond linguistic equivalence (Peña, Citation2007).

In sum, this study aims to (1) conduct and describe the translation and cultural adaptation process of the TCM questionnaire battery, (2) create a web-based TCM questionnaire battery to be used within the school-based 11 for Health concept, and in doing so (3) address content validity through cognitive debriefing and observations with target users, while evaluating conceptual, item, semantic, and operational equivalencies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Design

This cross-cultural adaptation study employed a qualitative and descriptive approach (Portney, Citation2020). The study was conducted from September 2018 to September 2019 and included an iterative and multistage process with translation and creation of a web-based TCM questionnaire battery as well as a series of cognitive debriefing interviews and observations. This process allowed in-depth insight into content validity and the addressed equivalencies of the 57-item TCM questionnaire battery (Terwee et al., Citation2018).

2.2. Measures

The translated TCM questionnaire battery comprised three parts that related to the three time points, and content related to perceived autonomy support by PE teachers (Hagger et al., Citation2007); autonomous (intrinsic and identified regulations) and controlled (external and introjected regulations) motivation for the perceived locus of causality scales for school and out-of-school contexts (Ryan & Connell, Citation1989); and intentions, attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control from the theory of planned behaviour for PA outside of school (Ajzen, Citation2002). Full details of the TCM questionnaire can be found in appendix A and a short description is given below. The Danish TCM questionnaire battery is available upon request from the corresponding author.

2.2.1. Time point 1 (week 0)

included 15 questions related to perceived autonomy support from the PE teacher (Hagger et al., Citation2007) and 8 questions related to autonomous and controlled forms of motivation for in-school PA (Ryan & Connell, Citation1989). Questions were formulated as statements and rated on a set of Likert scales. Perceived autonomy support from the PE teacher was rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Autonomous and controlled forms of motivation for in-school physical activities were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (very true) to 4 (not true at all). (See appendix A; Time 1 (week 0).

2.2.2. Time point 2 (week 1)

included 9 questions related to planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation2002), 16 questions related to perceived locus of causality in a leisure-time PA context (Ryan & Connell, Citation1989), 3 questions related to perceived behavioural control, and 4 questions related to subjective norms (Ajzen, Citation2002). In relation to planned behaviour, the first question addressed the amount of vigorous PA practised more than 20 minutes per day during the last 6 months according to a set of fixed response options from 1 (not at all) to 6 (most days per week). Three questions addressed intentions, plans, and expectations for a 5-week PA participation and were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), while one question addressed attitudes towards PA in leisure-time and was rated according to a set of five 7-point semantic differential scales covering boring-interesting, unenjoyable-enjoyable, bad-good, useless-useful, and harmful-beneficial. The 16 questions related to perceived locus of causality in a leisure-time PA context addressed four types of regulations (external, introjected, identified, and intrinsic) and were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (not true for me) to 7 (very true for me). The three questions related to perceived behavioural control addressed control over exercise during leisure-time and were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (very little control/strongly disagree) to 7 (complete control/strongly agree). The four questions related to subjective norms about PA in leisure time for the next 5 weeks were rated on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). (See appendix A; Time 2 (week 1).

2.2.3. Time point 3 (week 5)

included 2 questions related to engagement in active sports and/or vigorous physical activities (Ajzen, Citation2002). The questions were formulated as statements in which schoolchildren were asked about the amount of past PA behaviour and rated on a Likert scale from 1 (unenjoyable) to 7 (enjoyable). (See appendix A; Time 3 (week 5).

2.3. Procedure

The three main phases included seven steps which are displayed in .

Table 1. Description of the content of the three phases in the trans-contextual model (TCM) translation process

Phase 1 (steps 1–3) included translation and creation of a web-based TCM questionnaire battery. The translation of the TCM was based on forward and backward translation, emphasizing linguistic accuracy (Brislin & Freimanis, Citation2001). As this translation method does not consider cultural aspects of language (McKenna, Citation2011), we added elements of the dual-panel method (using experts and a “lay” panel), as recommended (McKenna, Citation2011; Mokkink et al., Citation2010; Regnault & Herdman, Citation2015). Following McKenna (Citation2011) the developer of the original questionnaire granted permission to translate, culturally adapt and validate the TCM into a Danish web-based questionnaire battery. As schoolchildren were not sufficiently capable of translating the TCM questionnaire battery, we decided not to include them in the translation lay panel, as recommended (Mckenna et al., Citation2012). Instead, the first author and a group of bachelor students produced two separate translations, which were then synthesized into a linguistically accurate consensus-based Danish web-based version named TCM-DK. Thereafter, one bilingual expert in sport and exercise psychology, who was familiar with the TCM, compared the TCM-DK to the original English version and made minor edits. At the end of phase 1, a web-based version of the TCM-DK was created and divided into a three-part design containing three separate links using Enalyzer (Citation2021) according to Time point 1 (week 0), Time point 2 (week 1), and Time point 3 (week 5).

Phase 2 (steps 4–5) included cognitive debriefing and observations. In total, two series of cognitive debriefing and observations were completed (Terwee et al., Citation2018). While the first series addressed the first version of the Danish web-based TCM-DK, the second addressed a second version of the Danish web-based TCM-DK adapted specifically to the 11 for Health concept.

Participants: Participants included fifth-grade Danish schoolchildren (ten boys and six girls, Mage = 11.65), of whom eight (4 boys and 4 girls) participated in the first series of individual cognitive debriefing and observations and eight (6 boys and 2 girls) participated in focus groups in the second series of cognitive debriefing and observations.

Procedure of cognitive debriefing and observations: Both series of cognitive debriefing and observations followed the three-part design (Time point 1, Time point 2, and Time point 3), were held in familiar classroom settings, and used an interview guide based on a model for cognitive debriefing, whereby two groups of schoolchildren would answer a range of probing questions (García, Citation2011) (see interview guide in appendix B). For both series of cognitive debriefing and observations a school location was chosen because it was considered topic-relevant and neutral and also provided room for social exchanges (Halkier, Citation2010). A short introduction to the TCM questionnaire battery was given, and probing questions were asked by interviewers. Examples of the probes included “Were there any questions you could not understand?”, “Can you repeat the question in your own words?”, “Was it easy or hard for you to answer the questions?”, “Could you find your answer among the response choices?” The interviewer could also ask spontaneous probing questions about the observation on the tablet, smartphone, or computer. The schoolchildren then clarified the spontaneous probing questions by pointing to the screen and elaborating on problems with the design of the web-based questionnaire, response categories and/or specific wording. To increase dependability of the translation process the interviews were recorded, and observations were described and transcribed verbatim after each cognitive debriefing and observation following the three-part design (Time point 1, Time point 2, and Time point 3).

The first series of cognitive debriefing and observations were conducted individually, with two schoolchildren who were interviewed individually each time at different ends of a classroom. All schoolchildren used a school tablet. Based on the first series of cognitive debriefing and observations, the first author conducted adjustments and adapted the 11 for Health concept to Time point 1 (week 0) of the three-part design.

The second series of cognitive debriefing and observations were conducted in focus groups with schoolchildren, following the teaching of the 11 for Health concept. Schoolchildren used a combination of school laptops and private smartphones. For the laptop users the questionnaire link was provided via the schoolchildren’s school e-mail account and for the smartphone users the link was provided via a QR-code.

Phase 3 (step 6) included analyses of the cognitive debriefing, review, and adaptation components. In order to ensure consistency, the data were analysed qualitatively and chronologically by the first author using a top-down approach with particular emphasis on comprehensibility following the two series of cognitive interviews and observations. The cognitive interviews and observations were analysed together using a triangulation of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) thematic analysis and Conrad and Blair (Citation1996) response problem matrix (RPM). The thematic analysis was used deductively and was analysis-driven, which implied that all data were related to specific equivalencies (i.e., conceptual, item, semantic, and operational) and were extracted to provide the unit of analysis (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). To confirm equivalencies, the RPM was used to identify the magnitude of the problem’s effect on response data (i.e., prominent, minor, lexical, inclusion/exclusion, temporal, logical, and computational) (Conrad & Blair, Citation1996). The thematic analysis involves searching across a data set to find repeated patterns of meaning (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), while the RPM can be described as a classification of possible response problems that may occur with questionnaire completion (Conrad & Blair, Citation1996). Thus, the thematic analysis is considered flexible and is framed as a realist/experiential method (Roulston, Citation2001), while the RPM taxonomy is somewhat stricter and can help specify problems and promote solutions (Conrad & Blair, Citation1996). A prominent problem was when the schoolchildren did not understand the content of the question or had insufficient information to answer, while a minor problem was when the schoolchildren had to re-read the question several times and/or asked for help from the interviewer but managed to provide a meaningful response. The responses to the TCM questionnaire battery in the second series were also analysed using descriptive statistics with frequencies and percentages. This was done to provide insight into which questions were answered using the full response scale. If there were questions with one response option overly favoured, these were then considered later together with all qualitative evidence. Based on these data it was later decided whether questions or response scales needed revisions.

Phase 3 (step 7) involved finalization of the battery together with experts. First, one bilingual expert in sport and exercise psychology reviewed and compared if the second version of the Danish web-based TCM-DK adapted to the 11 for Health concept matched the original English version to ensure content validity. Second, the Danish web-based TCM-DK adapted to the 11 for Health concept was back-translated to the original English language (Brislin & Freimanis, Citation2001) and approved by two experts in sport psychology.

2.4. Ethical approval

The study was a part of a comprehensive research study approved by the Regional Committees on Health Research Ethics for Copenhagen and Southern Denmark (J.no H-16026885).

3. Results

The four identified themes showed in were: Considerations to be taken into account in creating the web-based questionnaire battery, adjustments needed when translating the questionnaire battery, required personal information, and response categories.

Table 2. Coding framework from the analysis derived from testing a web-based Danish version of the trans-contextual model questionnaire in 10–12 year-old schoolchildren

Our RPM taxonomy which is summarised in showed that most questions were understood as intended or only had minor problems. However, we identified prominent problems with the introductory text for all three parts of the TCM questionnaire battery. Furthermore, we identified problems in 23 out of 57 questions, out of which one contained a prominent problem and 22 contained minor problems. In addition, we identified prominent problems in all questions that asked for participants’ personal information. Prominent problems were also identified in the first two parts of the questionnaire battery (computational and temporal) with regard to the questions’ response categories.

Table 3. Summary of Respondents problem matrix including referent, source of confusion, solution, and taxonomy problems

4. Considerations to be taken into account in creating the web-based questionnaire battery

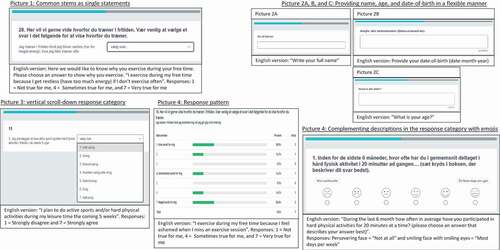

The first theme referred to operational equivalence. Across the two rounds of cognitive interviews and observations, the web-based TCM questionnaire battery was found to be a suitable tool for the targeted group of Danish schoolchildren. We discovered that the applied questionnaire program Enalyzer, which is shown in , was easy to use, and that electronic devices such as tablets, laptops and smartphones were widely available in a Danish school context.

Figure 2. Observations on how descriptions, items, and response categories were interpreted by the schoolchildren in Enalyzer

During both cognitive interviews we observed that most of the schoolchildren were focused on answering the questions as quickly as possible. To increase their concentration, we found it beneficial to assign the self-report questionnaire as schoolwork, and for the second round of cognitive interviews and observations we programmed the survey in such a manner that the schoolchildren were required to reply to each question before advancing to the next question. The first round of cognitive interviews and observations showed that the schoolchildren either did not read and/or were not able to remember the common stems for the questions (i.e., “the part of the survey question that presents the issue about which the question is asking or the instruction” (Roe, Citation2008, p. 666)). We therefore presented all common stems as single statements before each question (see , picture 1). This meant that the survey was programmed in such a way that the question was repeated before each single question and not just presented at the beginning of the scale.

4.1. Adjustments when translating the questionnaire battery

The second theme referred to conceptual, item and semantic equivalence. A common finding across the two rounds of cognitive debriefing and observations was that most of the questions were easy to understand, especially when referring to the 11 for Health concept in the second round of the cognitive interviews. However, during the first round of cognitive interviews and observations, the schoolchildren seemed somewhat reluctant to elaborate their interpretation and understanding of the questions. Minor lexical and inclusion/exclusion problems were found in most questions in this first round. We also found that providing a targeted description—highlighting that the PE session was the area of interest when introducing the questionnaire battery—was needed. During the first round we did not explicitly refer to the 11 for Health concept. One example was when the schoolchildren told us afterwards that they felt understood by their PE teacher, but when we asked them for more details, they referred to situations during their math instruction. We then realized that the PE teacher was also the children’s math teacher, making their replies less specific to PE sessions. The intended focus of the question concerned, however, was exclusively the PE session. These points were adjusted after the first round of cognitive interviews and observations. Consequently, these problems did not occur during the second round, which underlines that targeted description of specific PE elements was needed to fully capture the intended content of the questions. Furthermore, our analysis revealed that specific wording had to be changed or added to address semantic and item equivalence and capture the original intent of the questions beyond linguistic equivalence. An example of this was found during the second round of cognitive interviews and observations in which the schoolchildren pointed out that a definition of the word “restless” was needed. Due to the fact that the schoolchildren were not able to provide a more suitable Danish word, they suggested to add a definition in a parenthesis next to the word restless, namely, “having too much energy” (see picture 1, ).

4.2. Required personal information

The third theme, which referred to item and operational equivalence, addressed the challenges that the schoolchildren experienced when asked to provide required personal information such as providing their name, age, and date of birth (see picture 2A, 2B, and 2 C, ). During both interviews and observations, all schoolchildren seemed confused about whether to use their first name, or if they should also provide their middle and last name. As it seemed important for the schoolchildren to highlight the differences between just turning 11 and being nearly 12 years of age, providing age and date of birth were also found challenging. Several attempts were made to capture this information in the best way possible (i.e., suggesting a visual digital calendar, a textbox, and limiting the responses to numbers). The most suitable solution for both problems was a more flexible textbox, in which names and age could be interpreted verbatim.

4.3. Response categories

The final theme response categories refers to item, semantic, and operational equivalence. This theme was identified as having several computational problems (i.e., residual types of problems). Distributions of responses were reviewed for each TCM question to gain additional insights into whether the questions would be able to discriminate between the schoolchildren differing in the measured construct (see appendix A). The responses showed a good spread for the three-part design, however with a tendency to choose positive response categories such as “strongly agree”, “true”, “strongly approve”, “very true for me”. To solve the several computational problems, the use of both numbers and text were found to be preferable (see picture 3, ). For some computational problems it was not always necessary to include two types of information in the response categories as most questions with longer horizontal response categories revealed an evenly distributed response pattern (see picture 4, ). The use of emojis to replace or complement numbers or descriptions within the response categories was also attempted. The interviews revealed that emojis were applicable, yet we found only one question for which it was necessary to complement descriptions in the response category using emojis (see picture 5, ). We defined this as a prominent problem as the question addressed PA behaviour in the last 6 months. We therefore resolved the prominent problem by making use of both emojis and supportive text.

5. Discussion

This study aimed to (1) conduct and describe the translation and cultural adaptation process of the TCM questionnaire battery, (2) create a web-based TCM questionnaire battery for use within the school-based 11 for Health concept, and (3) in this process address content validity through cognitive interviews and observations with target users while evaluating specific equivalences (i.e., conceptual, item, semantic, and operational). Our findings suggest that the translated Danish three-part TCM questionnaire battery design was understood as intended when used within the context of the 11 for Health concept. However, to uphold a scientific standard of measurement and fully capture the theoretical construct of the TCM we identified four themes namely: considerations to be taken into account in creating the web-based questionnaire battery, adjustment needed when translating the questionnaire battery, required personal information, and response categories. Further, we identified and solved prominent problems with the introduction in all three parts of the TCM and discovered the need of using a targeted description of the 11 for Health concept. We identified and solved lexical problems in 23 out of 57 questions, out of which one question contained a prominent problem in which a definition of a word was needed, and 22 questions contained minor problems regarding word adjustment. Lastly, we identified and resolved prominent problems that occurred when the schoolchildren had to provide personal information, and for the computational problems in the response categories.

When addressing content validity as a first step in scale development and validation, there is often a need to delete items (Boateng et al., Citation2018) and this decision should not be made lightly (Regnault & Herdman, Citation2015). However, none of the two independent groups of schoolchildren mentioned the need to delete items within the TCM which supports our translation and cultural adaptation process. Schoolchildren who had not yet participated in the 11 for Health concept were considered a useful first group for additional validity and pre-testing (Collins, Citation2003). Afterwards, schoolchildren already taking part in the 11 for Health concept were involved in the pre-testing as they were able to judge the relevance and in particular the comprehensibility of the questionnaires while participating (McKenna, Citation2011) and thereby also ensured that a child-friendly language was being used (Andersen & Kjærulff, Citation2003; McCusker et al., Citation2015). Although previous studies recommend between 30 and 40 persons for pre-testing in the final stage of the adaptation process (Beaton et al., Citation2000), we found that the participation of 16 schoolchildren were sufficient which is also supported elsewhere (De Leeuw, Citation2011). As children lack the required linguistic capacity to process complex questionnaire structures (Andersen & Kjærulff, Citation2003; Devine et al., Citation2018), and have more difficulties with cognitively demanding survey questions than adults (Borgers et al., Citation2004; Scott, Citation1997) a working memory period of 3 months is considered maximum for children in questionnaires for memory to be roughly exact (Larsen, Citation2002). Therefore, we adjusted some of the response categories when referring to common stems and provided supportive working memory information (i.e., emojis) to support the text when addressing past PA behaviour (Alismail & Zhang, Citation2020; Kaye et al., Citation2017; Thompson & Filik, Citation2016). The need for adjusting such elements is also supported in other studies with children and adolescents, on the basis that these types of questions require more complex cognitive processes (Kröner-Herwig et al., Citation2010; Sampaio Rocha-Filho & Hershey, Citation2017; Smith & Platt, Citation2013). When reviewing the response distribution to obtain additional insights into whether the questions would discriminate among the schoolchildren differing in the measured construct, we found a tendency to choose positive response categories such as “strongly agree”, “true”, “strongly approve”, “very true for me”. This is supported elsewhere, as children of this age tend to please the researcher, which may result in more superficial answers and socially desirable responses (De Leeuw, Citation2011).

Denmark has implemented comprehensive national IT strategies in recent years (EU, Citation2020), making the use of web-based questionnaires applicable and easy to use for this age group and within this culture (Statistik, Citation2019). However, in newly translated versions of web-based questionnaires, comprehensibility is of major importance (Gera et al., Citation2020), which is why we emphasized content validity in our study. This is important since the translated web-based version is to be used within the large-scale school-based 11 for Health concept.

5.1. Methodological considerations

In this study the content validity was addressed while evaluating conceptual, item, semantic, and operational equivalence. To confirm equivalence, we combined two translation methods to enhance the value of the forward-backward translation (Brislin & Freimanis, Citation2001) by adding elements of the dual-panel method to build quality into the three phases of translation and cultural adaptation process. In the dual-panel method, a bilingual panel representing the target audience (Mckenna et al., Citation2012) should produce the first translation. However, since our target group of schoolchildren was not capable of translating the 57-item TCM questionnaire battery we used experts and a lay panel as recommended elsewhere (McKenna, Citation2011; Mokkink et al., Citation2010; Regnault & Herdman, Citation2015). As recommended by McKenna (Citation2011) we made every attempt to involve the schoolchildren as the target group in all phases of the process.

Furthermore, we added two rounds of cognitive debriefing interviews and observations with schoolchildren, as recommended in the literature (McKenna, Citation2011; Mckenna et al., Citation2012). However, for the first round of cognitive interviews and observations we did not refer to the actual intervention. This choice might have influenced our results as the first group of schoolchildren was found to be somewhat reluctant to elaborate on their interpretation and understanding of the TCM questionnaire battery in depth. This reluctance was not seen in the second group of schoolchildren, which can be explained by the fact that this group was able to refer to the 11 for Health as recommended in the methodological literature (Mckenna et al., Citation2012) and as suggested in the TCM literature (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, Citation2009; Hagger et al., Citation2005; Hagger & Hamilton, Citation2018). Therefore, our combined translation process and development of a web-based Danish version of the TCM seemed to work well. The original intention behind the TCM was preserved and hidden problems regarding aspects of conceptual, item, semantic, and operational equivalence were addressed and resolved. Thus, we believe our web-based Danish version of the TCM questionnaire battery with adequate content validity can be used in studies targeted at schoolchildren 10 years of age and up (Mokkink et al., Citation2010).

5.2. Recommendations for providing a web-based version of the TCM

In line with WHO recommendations, we will highlight some important considerations when developing web-based versions of questionnaires aimed at children (WHO, Citation2021). First, we recommend that only one piece of information and/or question is presented at a time to ensure that the original intention of the measure is preserved (Peña, Citation2007). Secondly, when referring to common stems such as “I exercise during my free time because … ” (Roe, Citation2008) we recommend that the stem is presented in each of the questions, and not solely at the beginning of the questionnaire. Thirdly, since schoolchildren, due to their age, are often impulsive and act in the spur of the moment (Leshem, Citation2016; Omrani et al., Citation2019), we recommend programming the questionnaire in such a way that that each question must be answered before the pupil can proceed to the next question. This will ensure a more complete data set. Fourth, we recommend that the web-based questionnaire is introduced and described as schoolwork and supervised by a teacher and/or researcher(s) as suggested elsewhere (Hagger & Hamilton, Citation2018). This introductory text should also be communicated using clear and simple short sentences (Borgers & Hox, Citation2000). Fifth, as schoolchildren in this study—as in other studies—found it challenging to provide their age (Andersen & Kjærulff, Citation2003), supplying a flexible textbox in which background information (i.e., name, age, and date-of-birth) can be entered is recommended to ensure the best answers. Sixth, when providing longer response categories and to fully capture the values, such as when using a Likert scale answering format from 1–7, we recommend considering using supplementary information (i.e., text and emojis) in all response categories to provide emotional and contextual cues (Alismail & Zhang, Citation2020; Kaye et al., Citation2017; Thompson & Filik, Citation2016).

6. Conclusion

In this study conceptual, item, semantic, and operational equivalence of a web-based Danish translation of the TCM questionnaire battery was achieved through an iterative process in three phases with participation of the target users (i.e., schoolchildren aged 10 to 12). This study adds to existing literature about the TCM questionnaire battery as well as adding knowledge to the approach when investigating content validity and cultural adaptation for schoolchildren. The results support the content validity of the translated Danish web-based TCM questionnaire battery, and the ability to measure the processes by which schoolchildren’s autonomous motivation towards in-school PA relates to autonomous motivation, intentions, and participation in similar activities outside of school. Challenges concerning the content of the TCM and the creation of a Danish web-based questionnaire battery were identified and resolved. Thus, the 57-item web-based Danish version of the TCM questionnaire battery is now ready for large-scale field testing of its psychometric properties, such as convergent validity, reliability, and responsiveness.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Esben Elholm Madsen

Esben Elholm Madsen ([email protected]) is a Ph.D candidate at the University of Southern Denmark, Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics. His research area is sport psychology, football and motivation, which will be applied within the “11 for Health – in Denmark” concept. The “11 for Health - in Denmark” concept is a health education concept targeted towards 10-12-year-old schoolchildren, taking place on the football pitch. The authors have previously investigated the impacts of the “11 for Health – in Denmark” concept and found positive effects on schoolchildren’s physical fitness, cognitive performance, well-being, enjoyment and health knowledge.

The validated web-based trans-contextual model questionnaire battery has been developed within the frame of the present study. The ambition is to apply the questionnaire battery to examine the effects of schoolchildren’s perceived autonomy support toward physical education-based football activities on autonomous motivation, beliefs, and intentions toward participating in physical activity outside of school.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Constructing a TpB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Amherst: University of Massachusetts. Retrieved January 29, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.601.956&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Alismail, S., & Zhang, H. (2020). Exploring and understanding participants’ perceptions of facial Emoji likert scales in online surveys: A qualitative study. ACM Transactions on Social Computing, 3 (2), 1–12. Article 12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3382505

- Andersen, D., & Kjærulff, A. (2003). Hvad kan børn svare på? -om børn som respondenter i kvantitative spørgeskemaundersøgelser. SFI – Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Velfærd.

- Austin, D. W., Carlbring, P., Richards, J. C., & Andersson, G. (2006). Internet administration of three commonly used questionnaires in panic research: Equivalence to paper administration in Australian and Swedish samples of people with panic disorder. International Journal of Testing, 6(1), 25–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0601_2

- Barkoukis, V., Hagger, M. S., Lambropoulos, G., & Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2010). Extending the trans-contextual model in physical education and leisure-time contexts: Examining the role of basic psychological need satisfaction. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(Pt 4), 647–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/000709910x487023

- Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural cdaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014

- Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: A primer [Review]. Frontiers in Public Health, 6(149), 149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00149

- Borgers, N., & Hox, J. (2000). Reliability of responses in questionnaire research with children. Paper presented at the Fifth International Conference on Logic and Methodology, Cologne, Germany.

- Borgers, N., Sikkel, D., & Hox, J. (2004). Response effects in surveys on children and adolescents: The effect of number of response options, negative wording, and neutral mid-point. Quality & Quantity, 38(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QUQU.0000013236.29205.a6

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brislin, R. W., & Freimanis, C. (2001). Back-translation: A tool for cross-cultural research. In C. P. Sin-Wai & E. David (Eds.), An encyclopaedia of translation (pp. 22–40). The Chinese University Press.

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S. J. H., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., Lambert, E., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

- Collins, D. (2003). Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Quality of Life Research, 12(3), 229–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023254226592

- Conrad, F., & Blair, J. (1996). From impression to data: Increasing the objectivity of cognitive interviews (Vol. 1, pp. 1–9). Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association.

- de Leeuw, E. D. (2011). Improving data quality when surveying children and adolescents: cognitive and social development and its role in questionnaire construction and pretesting. Department of Methodology and Statistics, Utrecht University.

- Devine, J., Klasen, F., Moon, J., Herdman, M., Hurtado, M. P., Castillo, G., Haller, A. C., Correia, H., Forrest, C. B., Ravens-Sieberer, U., Schröder, L. A., & Metzner, F. (2018). Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of eight pediatric PROMIS® item banks into Spanish and German. Quality of Life Research, 27(9), 2415–2430. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1874-8

- Donker, T., van Straten, A., Marks, I., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). Brief self-rated screening for depression on the Internet. Journal of Affective Disorders, 122(3), 253–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.07.013

- Enalyzer. (2021). Enalyzer www.enalyzer.com/#

- EU. (2020). Education and training monitor 2020.

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500107

- García, A. A. (2011). Cognitive interviews to test and refine questionnaires. Public Health Nursing, 28(5), 444–450. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00938.x

- Gera, A., Cattaneo, P. M., & Cornelis, M. A. (2020). A Danish version of the oral health impact profile-14 (OHIP-14): Translation and cross-cultural adaptation. BMC Oral Health, 20(1), 254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-020-01242-z

- Hagger, M. S. (2014). The trans-contextual model of motivation: An integrated multi-theory model to explain the processes of motivational transfer across contexts University of Jyväskyla]. Jyväskyla.

- Hagger, M. S., Biddle, S. J. H., Chow, E. W., Stambulova, N. B., & Kavussanu, M. (2003). Physical self-perceptions in adolescence: Generalizability of a hierarchical multidimensional model across three cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(6), 611–628. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022103255437

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2009). Integrating the theory of planned behaviour and self‐determination theory in health behaviour: A meta‐analysis. British Journal of Health Psychology, 14(2), 275–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1348/135910708X373959

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2012). Transferring motivation from educational to extramural contexts: A review of the trans-contextual model. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 27(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-011-0082-5

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2016). The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: Conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 360–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315585005

- Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Barkoukis, V., Wang, C. K. J., & Baranowski, J. (2005). Perceived autonomy support in physical education and leisure-time physical activity: A cross-cultural evaluation of the trans-contextual model. Journal of Educational Psychology, 97(3), 376–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.376

- Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Hein, V., Pihu, M., Soos, I., & Karsai, I. (2007). The perceived autonomy support scale for exercise settings (PASSES): Development, validity, and cross-cultural invariance in young people. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(5), 632–653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.09.001

- Hagger, M. S., Chatzisarantis, N. L. D., Hein, V., Soós, I., Karsai, I., Lintunen, T., & Leemans, S. (2009). Teacher, peer and parent autonomy support in physical education and leisure-time physical activity: A trans-contextual model of motivation in four nations. Psychology & Health, 24(6), 689–711. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440801956192

- Hagger, M. S., & Hamilton, K. (2018). Motivational predictors of students’ participation in out-of-school learning activities and academic attainment in science: An application of the trans-contextual model using Bayesian path analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 67(1), 232–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.09.002

- Halkier, B. (2010). Focus groups as social enactments: Integrating interaction and content in the analysis of focus group data. Qualitative Research, 10(1), 71–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109348683

- Hutmacher, D., Eckelt, M., Bund, A., & Steffgen, G. (2020). Does motivation in physical education have an impact on out-of-school physical activity over time? A longitudinal approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197258

- Kaye, L. K., Malone, S. A., & Wall, H. J. (2017). Emojis: Insights, affordances, and possibilities for psychological science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(2), 66–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.007

- Kröner-Herwig, B., Heinrich, M., & Vath, N. (2010). The assessment of disability in children and adolescents with headache: Adopting PedMIDAS in an epidemiological study. European Journal of Pain, 14(9), 951–958. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.02.010

- Krustrup, P. (2018). FIFA 11 for Health in Europe. Odense, Denmark: Department of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics, University of Southern Denmark. Retrieved January 27, from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03397628

- Krustrup, P., & Krustrup, B. R. (2018). Football is medicine: It is time for patients to play! British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(22), 1412–1414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099377

- Larsen, H. B. (2002). Spørgsmålsformuleringer til børn – Set fra et udviklingspsykologisk perspektiv. In I. D. Andersen & M. H. Ottosen (Eds.), Børn som respondenter. Om børns medvirkning i survey (Vol. 02, pp. 99–118). Socialforskningsinstituttet.

- Larsen, M. N., Elbe, A.-M., Madsen, M., Madsen, E. E., Ørntoft, C. Ø., Ryom, K., Dvorak, J., & Krustrup, P. (2021). An 11-week school-based ‘health education through football programme’ improves health knowledge related to hygiene, nutrition, physical activity and well-being— And it’s fun! A scaled-up, cluster-RCT with over 3000 Danish school children aged 10–12 years old. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 55, 906–911. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-103097

- Leshem, R. (2016). Brain development, impulsivity, risky decision making, and cognitive control: Integrating cognitive and socioemotional processes during adolescence—an introduction to the special issue. Developmental Neuropsychology, 41(1–2), 1–5. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/87565641.2016.1187033

- Lind, R. R., Geertsen, S. S., Ørntoft, C. Ø., Madsen, M., Larsen, M. N., Dvorak, J., Ritz, C., & Krustrup, P. (2018). Improved cognitive performance in preadolescent Danish children after the school-based physical activity programme “FIFA 11 for Health” for Europe – A cluster-randomised controlled trial. European Journal of Sport Science, 18(1), 130–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2017.1394369

- Madsen, M., Elbe, A.-M., Madsen, E. E., Ermidis, G., Ryom, K., Wikman, J. M., Lind, R. R., Larsen, M. N., & Krustrup, P. (2020). The “11 for Health in Denmark” intervention in 10- to 12-year-old Danish girls and boys and its effects on well-being: A large-scale cluster RCT. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 30(9), 1787–1795. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13704

- McCusker, P. J., Fischer, K., Holzhauer, S., Meunier, S., Altisent, C., Grainger, J. D., Blanchette, V. S., Burke, T. A., Wakefield, C., & Young, N. L. (2015). International cross-cultural validation study of the Canadian Haemophilia Outcomes: Kids’ Life Assessment Tool. Haemophilia, 21(3), 351–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/hae.12597

- McKenna, S. P. (2011). Measuring patient-reported outcomes: Moving beyond misplaced common sense to hard science. BMC Medicine, 9(1), 86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-86

- Mckenna, S. P., Wilburn, J., Thorsen, H., & Brodersen, J. (2012). Adapting patient-reported outcome measures for use in new languages and cultures. In K. B. Christensen, S. Kreiner, & M. Mesbah (Eds.), Rasch models in health. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118574454.ch16

- Mokkink, L. B., Terwee, C. B., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Stratford, P. W., Knol, D. L., Bouter, L. M., & De Vet, H. C. W. (2010). The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(7), 737–745. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.006

- Müftüler, M., & İnce, M. L. (2015). Use of the trans-contextual model - based physical activity course in developing leisure-time physical activity behavior of university students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 121(1), 31–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2466/06.PMS.121c13x1

- Omrani, A., Wakefield-Scurr, J., Smith, J., & Brown, N. (2019). Survey development for adolescents aged 11–16 Years: A developmental science based guide. Adolescent Research Review, 4(4), 329–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-018-0089-0

- Ørntoft, C. Ø., Larsen, M. N., Madsen, M., Sandager, L., Lundager, I., Møller, A., Hansen, L., Madsen, E. E., Elbe, A.-M., Ottesen, L., & Krustrup, P. (2018). Physical fitness and body composition in 10–12-year-old Danish children in relation to leisure-time club-based sporting activities. BioMed Research International, 2018, 9807569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9807569

- Pannekoek, L., Piek, J. P., & Hagger, M. S. (2013). Motivation for physical activity in children: A moving matter in need for study. Human Movement Science, 32(5), 1097–1115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2013.08.004

- Peña, E. D. (2007). Lost in translation: Methodological considerations in cross-cultural research. Child Development, 78(4), 1255–1264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01064.x

- Portney, L. G. (2020). Foundations of clinical research - Applications to evidence-based practice (4 ed. ed.). F.A. Davis.

- Regnault, A., & Herdman, M. (2015). Using quantitative methods within the Universalist model framework to explore the cross-cultural equivalence of patient-reported outcome instruments. Quality of Life Research, 24(1), 115–124. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0722-8

- Roe, D. (2008). Question stem. In P. J. Lavrakas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of survey research methods (p. 666). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Roulston, K. (2001). Data analysis and ‘theorizing as ideology’. Qualitative Research, 1(3), 279–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/146879410100100302

- Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749–761. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.57.5.749

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social Development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Sampaio Rocha-Filho, P. A., & Hershey, A. D. (2017). Pediatric migraine disability assessment (PedMIDAS): Translation Into Brazilian Portuguese and cross-cultural adaptation. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain, 57(9), 1409–1415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13159

- Scott, J. (1997). Children as respondents: Methods for improving data quality. In L. Lyberg (Ed.), Survey measurement and process quality (pp. 331–350). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118490013.ch14

- Shen, B., McCaughtry, J. M., & Martin, J. (2008). Urban adolescents’ exercise intentions and behaviors: An exploratory study of a trans-contextual model. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(4), 841–858. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2007.09.002

- Smith, K., & Platt, L. (2013). How do children answer questions about frequencies and quantities? Evidence from a large-scale field test. Centre for Longitudinal Studies.

- Standage, M., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2003). A model of contextual motivation in physical education: Using constructs from self-determination and achievement goal theories to predict physical activity intentions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.97

- Statistik, D. (2019). IT anvendelse i befolkningen. Danmarks Statistik. https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/GetPubFile.aspx?id=29449&sid=itbef2019

- Terwee, C. B., Prinsen, C. A. C., Chiarotto, A., Westerman, M. J., Patrick, D. L., Alonso, J., Bouter, L. M., De Vet, H. C. W., & Mokkink, L. B. (2018). COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Quality of Life Research, 27(5), 1159–1170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0

- Thompson, D., & Filik, R. (2016). Sarcasm in written communication: Emoticons are efficient markers of intention. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(2), 105–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12156

- Toftager, M., & Brønd, J. C. (2019). Fysisk aktivitet og stillesiddende adfærd blandt 11-15-årige: National monitorering med objektive målinger. Sundhedsstyrelsen. https://www.sdu.dk/da/sif/rapporter/2019/fysisk_akvtivitet_og_stillesiddende_adfaerd_bland_11-5-aarige

- Vallerand, R. J. (2007). A hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for sport and physical activity. In M. S. Hagger, & N. L. D. Chatzisarantis (Eds.), Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in exercise and sport (pp. 255–279, 356–363). Human Kinetics.

- Vallerand, R. J., & Losier, G. F. (1999). An integrative analysis of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 11(1), 142–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209908402956

- WHO. (2021). Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/