?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Despite the consensus on the vital role of human capital investment towards a country’s socio-economic development, school enrolment levels in South Sudan remain dismal with no empirical study conducted to unravel the same. Using the 2016 South Sudan Frequency Survey data, this study sought to unravel the determinants of primary school enrolment in South Sudan with a central focus on the role of the community characteristics. The study also aimed at exploring the disparities in primary school enrolment along the gender and employment perspective lens. The probit model findings revealed that the more time is taken in accessing a primary school, hospital, or food outlet facilities, the lower the probability of a child enrolling in school. School enrolment levels were found to be highest in the Central Equatoria state but lowest in the Lakes state. Furthermore, wide employment and gender differentials in school enrolment rates exist with boys being accorded more preferences than girls. Gender sensitization at the household, community, and state levels as well as the subsidization of primary education are vital in incentivizing parents to enroll their children in school. Similarly, high investment in better infrastructural facilities would ensure schools, hospitals, and water sources are within the reach of school-going children.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Investment in human capital is paramount in realizing a country’s development aspirations. Despite this consensus, South Sudan’s education system is characterized as low investment and low capacity, but high demand. As reported in 2017 by UNICEF, South Sudan has the world’s highest proportion of out-of-school children in the world, with 72% of primary-aged children out of school. Despite gaining her independence in 2011 which marked it as the world’s newest nation, the country continues to suffer from the effects of long-lasting civil wars that have been experienced over the last five decades. This has and continues to undermine the country’s development prospects by depriving its citizens of their basic human right to education. This study, therefore, seeks to unravel those factors that most importantly influence primary school enrollment in South Sudan. Further, the study also seeks to explore the disparities in enrollment along the gender and employment perspective lens.

1. INTRODUCTION

Investment in education is indispensable in achieving a country’s development aspirations (Olaniyan & Okemakinde, Citation2008). Equally, it enhances an individual’s earnings prospects (Mincer, Citation1974). However, unlike in developed countries, investment in schooling in the sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) region and more particularly in South Sudan remains low. Gender, regional, and occupational differences in human capital investment in South Sudan still exist. The objectives of this study are two-fold. First, the study seeks to unravel those factors that most importantly determine primary school enrolment in South Sudan. Secondly, the study also aims to explore the disparities in primary school enrolment along the gender and employment perspective lens.

As the world’s newest nation, South Sudan has and continues to face a myriad of challenges that adversely affect her education system. Before South Sudan gaining its statehood in 2011, former Sudan has had to battle with the effects of two long-lasting civil wars (from 1955 to 1972 & 1983 to 2005) over the last five decades. The wars have been largely cited to stem from the political marginalization of some ethnic groups and inequitable distribution of resources across the country. These many years of conflict and wars have led to the loss of approximately 2.5 million lives (Lodou & Oladele, Citation2018).

Equally, many schooling facilities have been destroyed, burned down, or even converted into hideout battlefields. Some teachers and students became either refugees or freedom fighters. This led to the deprivation of her citizens the basic human right to education. To much disappointment, gaining independence in 2011 did not remedy the situation. In 2013, other fresh conflicts, largely attributed to resource control battle, surfaced leaving an estimated number of at least 866,000 school-aged children displaced, (more particularly those from the remote and rural areas) and without access to safe and protective learning facilities. Approximately 400,000 children were reported to have dropped out of school. Moreover, the majority of the 1,200 schools in the conflict-affected states of Unity, Upper Nile, and Jonglei were closed (Lodou & Oladele, Citation2018).

The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, Citation2017) observes that after a prolonged period of conflict, South Sudan’s system of education is gradually striving to meet its needs. However, its progress has been thwarted by high dropout rates and dismal enrolment rates in primary school among females as compared to males. Compared to that of SSA countries, South Sudan’s enrolment rate is twice less. Indeed, the gross enrolment ratio in primary school dropped from 84.8% in 2011 to 66.6% in 2015. Between 2011 and 2015, the enrolment rates dropped by 11% & 6% for males and females, respectively; though the male’s enrolment rate is still higher than that of females.

Despite these disparities in primary school enrolment rates, empirical studies that can address this problem are largely deficient in the South-Sudanese context. Besides, most studies in developing countries rather tend to focus more on the demand-side characteristics as opposed to the supply-side characteristics. These factors are fundamental in informing the school enrolment decision. They are even more significant in the light of the youngest nation in Africa that was largely hit by civil war conflicts on their road to acquiring statehood in 2011 as well as culminated prolonged power battles within the government.

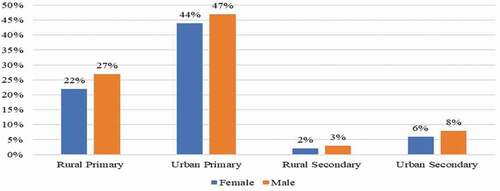

In South Sudan, the school enrolment rates are dismal and lower than the average enrolment rates in SSA. Also, gender and geographical differences in enrolment are visible. For instance, in rural primary and secondary schools, enrolment is characterized by male dominance, so is the case with the urban primary and secondary enrolment (see ).

Figure 1. School enrolment rate in south sudan

This calls for the need for policy interventions to address the gender and geographical disparities in school enrolment. After gaining independence in 2011, South Sudan adopted the 8-4-4 system of education. The country’s Vision 2040 notes that the education system is aimed at eradicating illiteracy among the youth and, thus, increase their prospects of employability. The post-statehood period saw the country affirm the integral role of schooling as contained in the Education Act. The Act’s guiding principles were to ensure free and compulsory primary education free of any racial, religious, or ethnic prejudice.

However, the ramifications of the long-protracted crisis did great harm to the country’s education system. The Government of South Sudan (Citation2011) estimated that about 63% of children who ought to be in school were not enrolled. In 2018, the United Nations noted that consequence of the protracted crisis, 48% of the country’s schools were not functioning. Being a young system, several supply & demand-side challenges still inhibit the country from achieving higher school enrolment rates as compared to other SSA countries.

On the supply side, schools are far from communities and even hard to access. Besides, the destruction of schools and the departure of teachers in conflict-affected areas exacerbate the continued prevalence of low school enrolment (UNESCO, Citation2017). On the demand side, lack of resources due to the high incidences of poverty has resulted in families allocating fewer resources for the education of children. Cultural beliefs are also seen to be a barrier. Norms and cultural practices have delineated specific roles across gender with girls tending to be more burdened with domestic duties and hence their low enrolment status.

South Sudan’s spending on education has been erratic and consistently declining compared to that of other countries in SSA. Her education expenditure as a % of government expenditure between 2012 and 2017 was less than 5%. This is in contrast with other countries whose educational expenditure as a proportion of government expenditure stood at over 10% and has been on an upward trend (World Bank, Citation2018a) (see ).

Table 1. Education expenditure as a proportion of the government expenditure

This pattern clearly shows that South Sudan still has a lot to do to catch up with her regional peers. This low government spending on education is alarming and shows little commitment towards the sector by the government. Furthermore, shows that the spending on education as a proportion of her GDP in South Sudan has experienced marked fluctuations with an even sharp decline in 2017 as compared to the level recorded in 2016. Even more surprising are the little levels of expenditure on schooling as a share of GDP considering the spending by other SSA countries (see ).

Table 2. Education expenditure as a proportion of the gross domestic product

The trends revealed in indicate that South Sudan needs to invest more in the education sector. In the context of a post-conflict and fragile state like South Sudan, the future path of the economy greatly depends on investing in progenies’ education. This study, thus, seeks to examine the determinants of disparities in primary school enrollment in South Sudan with a central focus on community characteristics.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 will review the literature. Section 3 will discuss the methodology and data. Section 4 will present the econometric estimates on school enrolment. Section 5 will provide the discussion and interpretation of results while the final section will present the study conclusions and policy implications based on the empirical findings.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Investment in human capital is often seen as a key to bolstering an economy’s growth and development (Olaniyan & Okemakinde, Citation2008). According to Gertler and Glewwe (Citation1990), it is viewed not only as a consumer good but also as a capital good. As a capital good, education adds to the stock of human capital through formal and on-the-job training and therefore is integral in boosting economic and social productivity. Just like any investment, human capital investment involves some initial sunk costs with the expectation of a return in some future date; either in the form of increased wage expectations or higher firm productivity.

Unlike other assets, the returns on investment in human capital are equivalent to the labor supplied (Hall & Johnson, Citation1980) which according to the human capital theory raises a worker’s marginal productivity which ultimately increases their lifetime income (Becker, Citation1964; Mincer, Citation1974; Schultz, Citation1961). The theory assumes that individuals are utility maximizers. They are deemed to be maximizing their lifetime stream of income whenever they make an investment choice (i.e. acquiring more education).

Several empirical studies have been conducted in the developing countries context. In investigating the determinants of school enrolment, attainment, and withdrawal through a gendered perspective lens, higher incomes are found to be associated with a higher significant improvement in girl’s schooling when compared to boys. Whereas a father’s level of education greatly influenced the boy’s education, a mother’s level of education significantly increased the girl’s education [(Al-Samarrai & Peasgood, Citation1998); (Glick & Sahn, Citation2000); (Handa et al. (Citation2004)); (Dancer & Rammohan, Citation2007); (Baschieri & Falkingham, Citation2009); (Kazeem et al. (Citation2010))]. These studies affirmed that in many African setups, household income levels and maternal and paternal preferences influenced school enrolment among girls and boys differently. Parents, and more so, fathers often attach more preferences to the male child’s education compared to that of females. This is attributed to the perceived low labor market return for females as they are discriminated against when it comes to employment opportunities.

Al-Samarrai and Reilly (Citation2000) find divergences in the primary school enrolment among rural and urban school-going children in Tanzania. This difference was attributed to the differences in household incomes across the regions. Besides, they also found that the child’s age positively and significantly influenced the prospect of being enrolled among both boys and girls. However, this relationship is not linear but rather concave; an indication that beyond a certain age threshold the probability of enrolling also declines.

Similarly, using cross-sectional and pseudo-panel data, Bedi et al. (Citation2004) examined the correlates of primary school enrolment in Kenya. From their study, they find that the increased cost of attending school and consequently, the reduced expected benefits from school attendance negatively affected school enrolment. Secondly, they observe that in urban areas, the prevalence of HIV/AIDs also played a central role in explaining the trend waning in primary school enrolment rates.

In another related study, Bold et al. (Citation2011) used a multinomial logit model in examining the determinants of the primary school enrolment rate in Kenya. According to the study, the introduction of free primary school education in 2003 together with parental income played a less significant role in predicting primary school enrolment rates. However, in the pre-free primary school policy period, they established a significant positive association between the head’s level of education and the probability that a child would enroll in primary school. They establish that an extra year in school by the head shove up enrolment by 0.8%, but the effect was reversed with the introduction of a free primary education program by the government.

Wahba (Citation2006) used data from Egypt to examine the role of adult market wages and parents who were child laborers on their children’s school enrolment and child labor. The study finds evidence that parents who were once child laborers have a higher propensity of sending their children to work rather than having them enroll in school. Furthermore, the more the number of younger siblings a household had, the lower the odds of schooling among the children and the higher the likelihood of child labor. Nielsen (Citation2001) finds a negative correlation between a child’s age and the propensity of primary school enrolment in Zambia. Also, transportation cost was found to negatively influence schooling while the presence of a school within the community and good infrastructure increased school enrolment (Filmer, Citation2007).

In Rural South Western Nigeria, Rahji and Falusi (Citation2005) established that boys were more likely to attend school than girls and this was driven by the cultural norms and beliefs that often tend to consider investment in boy’s education to be better than that of girls. In a study in Somalia, Moyi (Citation2012) found that boys were more likely to be enrolled in school than girls. In an extended view, household income was found to greatly influence school enrolment decisions as children from poor households in Sudan were less likely to enroll in school (Ebaidalla, Citation2018). Moreover, Fincham (Citation2018) revealed that even after enrolment, girls were more likely to drop out of school as compared to boys in the Red Sea State of Sudan.

Other studies conducted outside the African context equally reveal disparities in the child school enrolment rates. For instance, in Turkey, Tansel (Citation2002) finds the existence of regional effects in school enrolment with girls in the South Eastern region of Turkey being more likely to drop out of school relative to those of other regions. In investigating the correlates of enrolment in India, Jayachandran (Citation2002) estimated a random effects panel model and found a positive correlation between labor force participation among adult females and school attendance. Also, poverty and household size were found to reduce the probability of a child being enrolled in school. Similarly, another related study by (Huisman & Smits, Citation2009) reveals that the larger the household size, the lower likelihood of a child being enrolled in school.

The empirical examination of the determinants of school enrolment in the developing economies context is not a new concept. However, the findings of these studies tend to be context-specific, and hence the need to conduct an empirical examination at the country level to establish those factors that can be targeted through policy to increase enrolment rates. Whereas several of the reviewed studies have looked at the determinants of school enrolment in different jurisdictions, there is a clear lack of empirical evidence in the case of South Sudan. More importantly, several studies have failed to consider the role of supply-side characteristics such as distance to the nearest school and availability of usable roads within the community, yet they are fundamental in influencing enrolment decisions. To address this shortcoming, this study includes several supply-side and community characteristics in the enrolment decision. Further, we analyze the disparities in primary school enrolment along the gender and employment perspective lens.

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. RESEARCH DESIGN

This study seeks to unravel the determinants of disparities in primary school enrolment in South Sudan by using both the descriptive analysis and the probit model regression analysis (experimental design) where the school enrolment decision is modeled as the dependent variable. We also conduct a correlation analysis to ascertain the degree of association among the regressors.

3.2. SCHOOLING MODEL ESTIMATION

The demand for schooling can be seen from two perspectives: First, as an investment in human capital, and second, as a consumption good. From the two respects, schooling presents a trade-off in the sense that it results in future income streams (Nielsen, Citation2001). Theoretically, the demand for schooling is utility deriving for the parents (Glick & Sahn, Citation2006; Jensen, Citation2010). In choosing whether to enroll or not, parents consider the utility of having the child enroll in school vis-a-vis having the child not being in school.

To model the schooling decision, we assume that the supply of schooling is unconstrained and in the spirit of Strauss and Thomas (Citation1995), the demand for schooling is thus modeled within the confines of the economic model of a household’s behavior, which is influenced by the household’s utility. Following Gertler and Glewwe (Citation1990), the functional form of the utility of a household conditional on a child being enrolled in school can thus be modeled as:

Where denotes the utility that an individual derives from investment in human capital.

is the increment in human capital gained by a child as a result of an additional year of education.

represents the possible

consumption that accrues after the direct and indirect costs incurred in having a child enrolled in school.

is the error term and is assumed to be normally distributed with a zero mean and constant variance.

The functional form of the utility when the household chooses not to have the child enroll in school can be expressed as:

Nonetheless, the maximization of the utility function in equations (1) and (2) above is subject to an income/budget constraint of the form;

In equation (3), P is the total cost associated with a child’s school attendance and comprises both the monetary and non-monetary costs while is the household’s disposable income. Combining equations (1) and (2) and optimizing them subject to the income constraint in equation (3) yields maximum utility as expressed in equation 4.

Where is the maximum utility,

is the utility from non-enrollment and the consumption of non-schooling goods while

is the utility derived from school enrolment. The optimization of the household utility function is, however, constrained by income. If the utility function is twice differentiable and continuous, then optimization yields the conditional demand for schooling, which is binary. The projected likelihoods are restricted between 0 and 1. Thus, it follows that the probability that parents will have their children enroll in school can be expressed as a conditional utility function of the following form:

The parameters of interest in the estimation are which give the determinants of school enrolment among school-age children. We can also express the net consumption of schooling expenditures by making the subject in the budget constraint equation

and then substitute it into equation (5) as follows:

Equation (6) shows the utility derived from having a child enrolled in school. Alternatively, if a child does not enroll in school, then the utility function takes the following form:

A household will have their child enroll in school if +

. The probability of sending a child to school is thus modeled as probit:

Both the theoretical and empirical literature has identified various factors as key in influencing a child’s school enrollment decision. They range from the individual, household, and community attributes and, thus, in a more simplified form, the school enrolment decision can be expressed as follows:

Where is the enrolment status variable and it takes a value of 1 if the child is enrolled in school and 0 otherwise.

is a vector of a child’s attributes,

is a vector of household attributes, and

represents a vector of community attributes.

More concretely, equation 10 specifies the model to be estimated;

Where denotes Gender,

is the employment status,

is the household’s head education level,

is the household size, and

is the land ownership status.

represents the time taken in hours to the closest food outlet, shop, or market, TPS refers to the time taken in hours to the nearest primary school while

is the time taken in minutes to the nearest hospital.

denotes the time taken in minutes to the nearest source of drinking water, and finally,

defines the location (state of residence).

captures the error term, which is assumed to be normally distributed.

Equation (10) is then estimated using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method. For interpretation purposes, the marginal effects after probit are computed.

3.3. Data type and source

This study employed the second wave of the 2016 South Sudan High-Frequency Survey data. This survey was conducted by the World Bank in collaboration with the National Bureau of Statistics of South Sudan between February and June 2016 with funding from the Department for International Development (DfID). The High-Frequency Survey monitored the welfare and perceptions of citizens at the household level. The respondents were interviewed on matters of security, education, employment, economic conditions, and access to services. This survey also provided extensive information on assets and consumption. The administration of the survey was through a stratified sampling approach with 16,658 respondents being interviewed. The approach was preferred over other sampling methods, such as simple random sampling for two major reasons: First, it is to obtain unbiased estimates for the whole population as well as different subdivisions of the population with some known level of precision. Secondly is to ensure that the final total sample includes establishments from all different sectors as opposed to being concentrated in one or two industries/sizes/regions.

3.4. Econometric issues

In estimating the schooling model presented in equation (10), this paper acknowledges that potential selectivity bias may arise from 3 case scenarios. One, correlation of the error term with school quality may result if the parent’s decision to enroll their child in school is partly based on unobserved child motivation and ability (Becker, Citation1962). Two, bias may arise in the schooling estimates if the sample of students in primary school is not representative of the school-age population of children. In such a case, the school quality coefficients may not reveal the true marginal effect that arises out of increment in school quality (Glewwe and Jacoby, Citation1994). Finally, the schooling intensity variable that is lacking in the model is the only indicator of both school enrolment and attainment. This variable may be correlated with the other variables included in the model. Additionally, the existence of varied parental tastes for education may not be observed; hence, it is difficult to disentangle them from the effects of other school inputs (Case & Deaton, Citation1999).

This study will address these issues by first ensuring that the sample selected is the only representative of the primary school-going children. Secondly, this study focuses on only school enrolment and not attainment. Therefore, the omission of the schooling intensity variable which by the way has not been captured in the data will not yield any selectivity bias issues. Finally, the issue of parental tastes may not be addressed in this study due to data limitations.

3.5. Statistical Treatment of Data

3.5.1. Descriptive statistics

This is presented in .

Table 3. Variable description and measurement

3.5.2. Summary statistics

This is shown in .

Table 4. Summary statistics of variables (N = 16,658)

From the individual and household perspectives, reveals that on average, 46.96% of the children in South Sudan were enrolled in primary school. This leaves a whopping 53.04% for the non-enrolled children of primary school-going age. On average, more boys enrolled in school at 53.19% as compared to girls at 46.81%. The employment statistics were very worrying as they revealed wealth disparities at the household level with only 11.18% of households having the parent or parents employed. Employment status was used as a proxy to the household’s income level.

An employed parent or household head will earn a certain wage that can be used not only in offsetting the household’s budget expenditures but also in offsetting the costs associated with having their children enroll in school. On average, 12.81% of the children enrolled in primary school were of the 5–9 years age bracket. Most children all over the world enroll in school within this age bracket as they normally have attained the very least pre-requisite cognitive ability to speak, read, and write.

As for the highest level of education completed, the majority of South Sudanese parents or parental heads have at least acquired primary school education at a mean of 32.16% with only about 8.56% possessing university education qualification. On average, 73.56% of the South Sudanese households owned a piece of land that could be used for a viable economic activity. The maximum number of people in a given household was 39 with the lowest being 1. On average, there were about nine people in a given household with a standard deviation of 4.815 around the mean value.

From the community perspective, it took one approximately a minimum of 0.0167 hours (or 1 minute) to access the closest food outlet, shop, or market facility. The maximum time taken was 10 hours. Similarly, it took a minimum of approximately 0.7876 (or 47 minutes) to the nearest primary school and a maximum time of 24 hours. This revealed that schools in South Sudan were far away from primary school-going children; something that could largely hamper school enrolment.

The average time taken in minutes to access a hospital was 41 minutes while it took one approximately 26 minutes to access the closest drinking source of water. These statistics reveal that crucial infrastructural facilities such as roads, hospitals, and water sources were either deficient or in poor conditions, hence, the longer the time taken to access them. The location statistics reveal that the enrolment rate was averagely higher in the Central Equatoria state (about 22.88%) and lowest in the Western Bahr El Ghazal (about 5.63%).

3.5.3. Correlation Analysis

The pair-wise correlation matrix revealed a weak degree of association among the explanatory variables; hence, multicollinearity was deemed not to be a problem (see Appendix 1).

4. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

The schooling model was estimated with the results presented in .

Table 5. The Determinants of primary school enrolment in South Sudan

4.1. The Determinants of primary school enrolment

In terms of individual characteristics, we find that being male increased the likelihood of being enrolled by 0.33% point as compared to being female ceteris paribus. This implied that boys were more advantaged in terms of school enrolment as compared to girls. These results are consistent with findings by Rahji and Falusi (Citation2005) and Moyi (Citation2012) who also find more preferential treatment accorded to the boys as compared to girls in the school enrolment decision. This could be attributed to negative cultural norms and beliefs that downplay the importance of educating girls. The perceived low labor market return from investing in a female child’s education, the belief that girls are meant to get married after all, and the household responsibilities they are tasked to undertake such as taking care of their siblings heavily weighs down on the girl child education.

A child belonging to the age group of 5–9 years was significantly more likely to enroll in school by 14.6% point as compared to other age groups ceteris paribus. This is considered the prime age during which children can enroll in school. Below this age group, a child’s brain may not be well developed enough to have the cognitive ability to speak, read, write and even think properly. They may also require a lot of attention at school when they are too young. Besides, this may also be a tall order for those children who have to walk for long distances to reach their school. On the other hand, above this age group, children may deem themselves too old to enroll in school (Nielsen, Citation2001). This may be due to either their psychological attitude or the peer stigma that is often associated with age.

In terms of household characteristics, an additional household member increased the average probability of primary school enrolment by 0.61% point ceteris paribus. The larger the size of the household, the higher and significant chances of a child enrolling in a primary school. The result is counterintuitive and contrasts the normal perception that as the number of members in household increases, the higher the household expenditures; hence, less or none of the income is devoted to school enrolment. More household members would also imply increased educational expenses. This finding is largely consistent with the strand of literature that has often found that the larger the family sizes, the higher the school enrolment (Al-Samarrai & Reilly, Citation2000). On the contrary, this conflicts with the other strand in the literature that finds that larger families are often associated with a lower likelihood of a child being enrolled in school (Huisman & Smits, Citation2009).

Secondly, being employed for the households’ heads increased the likelihood of having their children enroll in school by 0.38% point as compared to the non-employed parents ceteris paribus. Employment status acts as a proxy to a household’s income level. If a parent is employed, then he or she will earn a certain amount of wage which can be channeled towards offsetting both the household and school expenditures for their children (Ebaidalla, Citation2018). Surprisingly, this variable was found to be statistically insignificant.

Third, the more educated the household head is, the higher the likelihood of their children enrolling in school. Holding other factors constant, a household head with primary or secondary school education qualification was less likely to enroll their children in school by 3.56% point and 0.89% point, respectively. This is compared to those parents without any education. The effect was highly felt for the case of primary school education level as the variable was found to be highly statistically significant at 1%. The secondary school education level variable was, however, found to be insignificant. On the other hand, a household head with university-level education as compared to no education was more likely to have their children enroll in school by 12.5% point ceteris paribus. These findings are consistent with those of Baschieri and Falkingham (Citation2009) and Kazeem et al. (Citation2010) who also established that higher parental education attainment was often associated with a higher likelihood of a child being enrolled in school. The cited reason being that educated parents are more literate and empowered enough to understand the value and the expected return from investment in child schooling.

Fourth, a household that owned land was more likely to have their children enroll in school by 26.6% point as compared to a household that did not own any land. Land ownership was used as a wealth index. This implied that owning land provided an opportunity of relaxing basic household expenditures on food through farming. By offsetting these expenditures, part of the income would then be devoted to school enrolment. Land ownership was found to be statistically significant at 1%.

Concerning the community characteristics, a one-hour increase in the average time taken by a child to reach a primary school decreased the probability of a child enrolling in school by 5.45% point ceteris paribus. The variable was found to be statistically significant at 1%. The further the school is, the more the time needed by the child to reach the learning facility hence the lower the chances of the child enrolling in school (Filmer, Citation2007).

Secondly, a one-hour increase in the average time taken by the child or parents in accessing a food outlet, shop, or market, the lower the chances of the child enrolling in school by 0.26% point ceteris paribus. The variable was found to be significant at 1%. Thirdly, holding other factors constant, a one-minute increase in the average time taken to access a hospital decreased the likelihood of a child enrolling in school by 0.12% point with the variable equally being significant at 1%. Consistent with findings by Al-Samarrai and Reilly (Citation2000), better roads, hospitals, and shops are very vital infrastructural amenities that heavily support the school enrolment decision.

Finally, regarding location, a child was more likely to enroll in a school located in Central Equatoria state by 48.9% point as compared to the Warrap state ceteris paribus. The probability of a child enrolling in school was found to be lowest (though positive) in the Lakes state at 11% point ceteris paribus. All six states were found to significantly and positively influence a child’s school enrolment decision. The findings reveal the pivotal role of proximity to infrastructural facilities in determining school enrolment as reiterated by Al-Samarrai and Reilly (Citation2000).

4.2. An employment and gendered perspective of the primary school enrolment status

To clearly understand the composition of primary school enrolment from the gender and employment status perspective, probit regression models were equally estimated with the results presented in .

Table 6. An employment and gendered perspective on the determinants of primary school enrolment

Standard errors in parentheses; *** p <0.01, ** p <0.05, * p <0.1

From the employment status perspective as presented in , the general trend reveals higher primary school enrolment levels for children when the household head or parents are employed as opposed to when they are unemployed. This is reflected through higher probability values for the employed model than for the unemployed model. This underscores why employment is very instrumental as it informs child school enrolment. These disparities are also consistent with previous findings by Bedi et al. (Citation2004) and Ebaidalla (Citation2018) that associate higher primary school enrolment with increased household incomes.

Similarly, the general trend in reveals that the probability of a male child enrolling in school is higher than that of their female counterparts. For instance, male children in the age group of 5–9 years are more likely to enroll in school as compared to female children by 29.5%. If a household head possesses a university education qualification, then the probability of enrolling their male children to school is higher than that of their female counterparts by a whopping 42.21%. Furthermore, if a household owned land, then the probability of enrolling the male children in school is also higher by 27.3%. These gender disparities in school enrolment further assert the male child education preferences and are consistent with findings by Rahji and Falusi (Citation2005), Dancer and Rammohan (Citation2007), and Moyi (Citation2012).

5. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The study concluded that individual, household, and community characteristics played an integral role in explaining a child’s enrolment in school. First, being male increased the likelihood of being enrolled than females, which implied that boys were more advantaged compared to girls. Secondly, a child’s age significantly increased the propensity of enrolment. Third, the parent’s education level and land ownership status significantly and positively influenced a child’s enrolment decision. Fourth, proximity to food outlets, hospitals, and schooling facilities was significant in informing the schooling decision. Finally, the enrolment choices at the employment and gendered analysis revealed preferences for education among boys to be higher than that among girls. Girls should be accorded equal opportunities to schooling just like the boys. This will effectively address the gender gap in schooling to the benefit of the whole society.

The study, therefore, recommends that the government of South Sudan subsidizes the education expenses as it will ultimately incentivize parents to enroll their children in school. Secondly, the government needs to invest heavily in better infrastructural facilities as this will ensure schools, hospitals, and water sources are within the reach of school-going children. Further, the government needs to develop gender sensitization programs at both the household and community levels that will educate parents or guardians on the importance of equitable schooling opportunities across all children. Since access to education is considered as a basic human right, every citizen should be sensitized to the significance of its acquisition regardless of parental employment or wealth status and child’s age status. Subsequent studies should attempt at analyzing the school attainment/completion rates as well as schooling demand at secondary and tertiary levels in South Sudan.

Acknowledgements

The authors express immense gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments which greatly improved the earlier version of this paper. The views expressed in this study are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the University of Nairobi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cyprian Amutabi

Cyprian Amutabi is a prospective Ph.D. student of Economics at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. He holds a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Nairobi, Kenya. His research interests largely focus on productivity, labor market issues, financial economics and econometric modeling. The author also has a special interest in the Economics of education and more so, the returns to schooling dynamics.

Martha Nyantiop Agoot holds a Master’s degree in Economics from the University of Nairobi, Kenya. Her research area of interest is Economics of Education but with a more particular interest in the challenges related to educational attainment. She also focuses her research on policy-oriented solutions towards schooling challenges, especially in developing countries.

References

- Al-Samarrai, S., & Peasgood, T. (1998). Educational attainments and household characteristics in Tanzania. Economics of Education Review, 17(4), 395–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(97)00052-6

- Al-Samarrai, S., & Reilly, B. (2000). Urban and rural differences in primary school attendance: An empirical study for Tanzania. Journal of African Economies, 9(4), 430–474. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/9.4.430

- Baschieri, A., & Falkingham, J. (2009). Staying in School: Assessing the role of access, availability and economic opportunities-the case of Tajikistan. Population, Space and Place, 15(3), 205–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.512

- Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. The Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital. a theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. Columbia University Press.

- Bedi, A. S., Kimalu, P. K., Manda, D. K., & Nafula, N. (2004). The decline in primary school enrolment in Kenya. Journal of African Economies, 13(1), 1–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/13.1.1

- Bold, T., Kimenyi, M., Mwabu, G., & Sandefur, J. (2011). Why did abolishing fees not increase public school enrolment in Kenya? Center for Global Development Working Paper No. 271. Available at SSRN: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1972336. [Accessed October 31, 2011]

- Case, A., & Deaton, A. (1999). School quality and educational outcomes in South Africa. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 1047–1084. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556124

- Dancer, D., & Rammohan, A. (2007). Determinants of schooling in egypt: The role of gender and rural/urban residence. Oxford Development Studies, 35(2), 171–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13600810701322041

- Ebaidalla, E. M. (2018). Understanding household education expenditure in Sudan: Do poor and rural households spend less on education? African Journal of Economic Review, 6(1), 160–178.

- Filmer, D. (2007). If you build it, will they come? School availability and school enrolment in 21 poor countries. Journal of Development Studies, 43(5), 901–928. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380701384588

- Fincham, K. (2018). Gender and primary school dropout in Sudan: Girls’ education and retention in red sea state. PROSPECTS, 47(4), 361–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-018-9420-6

- Gertler, P., & Glewwe, P. (1990). The willingness to pay for education in developing countries: Evidence from rural peru. Journal of Public Economics, 42(3), 251–275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(90)90017-C

- Glewwe, P., & Jacoby, H. (1994). Student achievement and Schooling Choice in low income countries: Evidence from ghana. The Journal of Human Resources, 29(3), 843–864. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/146255

- Glick, P., & Sahn, D. E. (2000). Schooling of girls and boys in a west african country: The effects of parental education, income, and household structure. Economics of Education Review, 19(1), 63–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(99)00029-1

- Glick, P., & Sahn, D. E. (2006). The demand for primary schooling in Madagascar: Price, quality, and the choice between public and private providers. Journal of Development Economics, 79(1), 118–145. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.01.001

- Government of South Sudan. (2011). The transitional constitution of the republic of south sudan, 2011. http://www.sudantribune.com/IMG/pdf/.

- Hall, A., & Johnson, T. R. (1980). The determinants of planned retirement age. Industrial & Labor Relations Review, 33(2), 241–254. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/001979398003300208

- Handa, S., Simler, K., & Harrower, S. (2004). Human capital, household welfare, and children’s schooling in Mozambique. International Food Policy Research Institute.

- Huisman, J., & Smits, J. (2009). Effects of household and district-level factors on primary school enrolment in 30 developing countries. World Development, 37(1), 179–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.01.007

- Jayachandran, U. (2002). Socio-economic determinants of school attendance in India. Working paper 103, Centre for Development Economics, Delhi School of Economics.

- Jensen, R. (2010). The (perceived) returns to education and the demand for schooling . The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 515–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2010.125.2.515

- Kazeem, A., Jensen, L., & Stoke, S. C. (2010). school attendance in nigeria: Understanding the impact and intersection of gender, urban-rural residence, and socioeconomic status. Comparative Education Review, 54(2), 295–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/652139

- Lodou, L. M., & Ogunniran, M. O. (2018). Examining the status of the universal primary educational in rural area (south sudan). In US-china education review B (pp. 8).

- Mincer, J. (1974). Schooling, Experience, and Earnings. Columbia University Press.

- Moyi, P. (2012). Who goes to school? School enrollment patterns in Somalia. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(1), 163–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2010.09.002

- National Bureau of Statistics of Sudan. (2008). The 5th sudan population and housing census 2008- IPUMS sub-set. center for census, evaluation and statistics.https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/1631 [Accessed 25 April 2018].

- Nielsen, H. S. (2001). How sensitive is the demand for primary education to changes in economic factors? Journal of African Economies, 10(2), 191–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jae/10.2.191

- Olaniyan, D. A., & Okemakinde, T. (2008). Human Capital Theory: Implications for educational development. European Journal of Scientific Research, 24(2), 157–162.

- Rahji, M. A. Y., & Falusi, A. O. (2005). A gender analysis of farm households’ labor use and its impacts on household income in southwestern Nigeria. Quarterly Journal of International Agriculture, 44(2), 155–166.

- Schultz, T. W. (1961). Investment in human capital. American Economic Review 51, (1), 1–17.

- Strauss, J., & Thomas, D. (1995). Human resources: Empirical modeling of household and family decisions. In T. N. Srinivasan & J. Behrman (Eds.), Handbook of development economics (pp. 1883–2023). North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Tansel, A. (2002). Determinants of school attainment of boys and girls in Turkey: Individual, household and community factors. Economics of Education Review, 21(5), 455–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00028-0

- UNESCO. (2017) . South sudan education sector analysis, 2016: Planning for resilience. International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Wahba, J. (2006). The influence of market wages and parental history on child labor and schooling in egypt. Journal of Population Economics, 19(4), 823–852. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0014-2

- World Bank. (2018a). Government expenditure on education, total (% of GDP)-South- Sudan.https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.XPD.TOTL.GD.ZS?locations=SS.

- World Bank. (2018b). School enrolment, primary (% gross) - South Sudan. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.ENRR?locations=SS