?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examined the question of whether the “emergency remote teaching” that was accidentally adopted during the pandemic will eventually lead to an acceleration of digitalizing the teaching and learning processes at PNGUoT. Utilizing a mixed-method explanatory sequential design, quantitative data were collected first and followed by the qualitative data as a cross-verification strategy to increase control, generalizability, confidence, and validity of the study findings. The Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) was used to analyze numerical data obtained from 169 undergraduate students, while thematic analysis was found appropriate for interviews of 44 academic staff. The findings revealed that staff and students’ attitude, and ICT support were reliable predictors of e-learning adoption (F = 315.854, p ≤ 0.001 & F = 121.132, p ≤ 0.001). When all the four parameters of (X) were taken together, explained 57.3% variations in the dependent variable (adjusted r2 = 0.573). It was also clear that the multiple linear regression model showed a significant effect (F = 29.116, p ≤ 0.001) because the p value was less than the calculated probability (0.05) which was the minimum level of significance required in this study to declare a significant effect. Whereas the emergence of remote teaching seemed to have yielded tangible results during the pandemic, it, unfortunately, may not eventually lead to an automatic appreciation of technology in the teaching and learning processes at PNGUoT. There is a need to understand what is working and why, and use this to increase inclusion, innovation, creativity, and cooperation in PNGUoT in getting ready for the years ahead.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Although it may be valid to claim that the abrupt pivoting to online delivery so far yielded tangible results, it may be unwise to conclude that the long-awaited innovation has finally arrived at PNGUoT. This study sought to establish whether the inevitably adopted “emergency remote teaching” during the pandemic would eventually accelerate the process of digitalizing the teaching and learning strategies at PNGUoT. The findings indicated that “emergency remote teaching” is still a mere change in the wave but not a wave of change! There is need to have a better understanding of what is working and why, and use this to increase inclusion, innovation, creativity, and cooperation in PNGUoT in getting ready for the years ahead.

1. Introduction

World over, the period between 2010 and 2020 will not only be remembered by the business fraternity that seemed uncomfortable with the speed of the waves the decade dragged them into but also by the academics who were found seemingly unprepared to tackle the challenges of the period in an academic context. It has been so exciting to those who made sense of the situation to their advantage but worrying and terrifying to those who were unprepared to counter the ugly face of the decade. Wendy Green et al. (Citation2020) regard the period as a watershed. It drove radical changes to the way universities operate, and to the day-to-day experiences of the people who work and study. Consistently, Michael Gaebel (Citation2020) submits that the sudden and disruptive shift to remote education aggravated the digital gap. Whereas it may be regarded as a decade of unprecedented e-learning acceptance and adoption, it should not be forgotten that digital acceptance was much seen in the last part of the decade more so during the Covid-19 eruption. It was a moment of panic, experimentation, and trial and error, as higher education (HE) was seen willingly succumbing to the orders of the pandemic. “Covidification of higher education” is suitably coined in this study to refer to the period when Covid-19 single-handedly ruled the affairs of HE world over. Universities worldwide struggled during the period, but the situation was much more worrying in universities in the developing countries where most students and academics too had no access to technology to comfortably switch from the traditional on-campus learning to digitally enhanced mode of learning. This trend of events was much more present in Papua New Guinea (PNG) too, as universities closed down academic business out of genuine panic to control the unforeseen dangers.

On the eve of the Covid-19 crisis, most universities in PNG had indicated that they had online repositories for educational materials in place, centres for e-learning, and units that support teachers on the digitally enhanced teaching and learning, and digital skilling. While this is a truism, these centres seemed ill-prepared to tackle the crisis given the exaggerated nature of the situation alongside strict operational budgets. Divine Word University and Sanoma Teachers’ College “known for digital learning” as Jan Czuba (Citation2020) indicated, also struggled at the outset of the pandemic. Good news is that, as soon as institutions of higher learning felt the pulse of the disaster, they intermittently closed down whilst looking for proactive measures to confront the situation. The PNGUoT, through the Teaching and Learning Methods Unit (TLMU) and the Department of Open and Distance Learning (DODL), championed the pivoting to online mode. This was indeed a historic opportunity to make a significant swift in the digital acceptance and adoption in the teaching fraternity (EUA, Citation2020).

There is no reason to believe that experience levels were different in other HE systems elsewhere in the world. Reports indicate that HE swiftly moved into the online space at breakneck speed during the crisis (Wendy Green et al., Citation2020). It is not inappropriate to regard the last quarter of the decade as a season of change that saw a digital take-up and general conversion of teaching and learning process. The Irish National Digital Experience (INDEx) Survey indicates that 70% of academics had never taught online before the pandemic, with similar figures in the U.K. (Irish National Digital Experience (INDEx) Survey, Citation2020). Correspondingly, UNESCO (2020) reports that the pandemic is dramatically shaking up the world of HE to the extent that no one is truly certain about the fate of university education in the days to come. It is further observed that university corridors and lecture theaters are empty YERUN Report on Seminar on COVID-19 (Citation2020); indigenous and international students are no longer admissible (Rashid & Yadav, Citation2020); uncontrollable panic and psychological jolt among the academics is a common trend Wendy Green et al. (Citation2020); while social distancing is part of the new order (Pedersen & Favero, Citation2020; Deopa & Fortunato, Citation2020 & Durante et al., Citation2020). A part from the cognitive and teaching presence, the learning cycle also takes cognizance of the social presence (Miliszewska (Citation2007), which is unfortunately rendered impermissible in the face of the Covid-19. The question is: can teaching and learning processes rise above social distancing restrictions? The answer to the traditional professional teachers is an obviously no, while yes to the digitally-driven teaching professionals. Whether these two extremes in perception are guided by logic or mere sentiments premised on peoples’ professional backgrounds, our duty as researchers is to analyze both and propose a suitable practical model that can aid the attainment of teaching and learning efficacy in times of the pandemic and other eras of similar nature that may emerge.

Provided in the available body of literature is the fact that technology adoption and acceptance has received a recognizable position than ever before in the history of HE (J.S. Ash et al., Citation2004; Surry et al., Citation2005; Straub, Citation2009; Moser, Citation2007; Amiel & Reeves, Citation2008; Al -Hujran et al., Citation2014; Tlhoaele et al., Citation2015). Whereas this may sound like an apparent reality, it is essential to acknowledge that past researchers seem to have directed much of their focus on examining and appraising the validity of adoption models such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) by Davis (Citation1989), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) by V. Venkatesh et al., (Citation2003), among others in their contexts. That being the case, the same parameters (e.g., perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, performance expectancy, effort expectance, social influence, etc.) have been repeatedly tested for validity across the HE spectrum and fortunately offered consistent results over time. It is against this background that this study chose to concentrate on contextual parameters (i.e., age, attitude, ICT support, and security & user trust), which seemed to have had a powerful contextual prediction on e-learning adoption during the preliminary stages (conceptual phase) of this study than what the models suggest.

2. Problem statement

Accepting and adopting e-learning in HE has been a debatable issue for the last two decades on grounds that its effectiveness (e-learning) to predict learning outcomes has been and is still a contestable matter (Mushtaq Hussain et al., Citation2018 & Pennaa & Stara, Citation2007). Whereas universities and colleges were slow to accept the integration of web-based learning into the traditional mode, the Covid-19 wave that emerged in December 2019 forcefully made HE recognize e-learning as the best alternative to on-campus learning (R.Radha et al., Citation2020). This global crisis triggered a reconceptualization of education provision at all levels in an inconceivable manner (StefaniaGiannini, Citation2020). The intensive use of different technological platforms and resources to ensure learning continuity is the boldest experiment HE has ever done, albeit, unexpectedly and unplanned (StefaniaGiannini, Citation2020). This notwithstanding, available evidence indicates that the Covid-19 shock was too much to be contained. For this reason, some universities opted for temporary closure, whilst others permanently closed because the cost of shifting lab-based sessions to online seemed practically impossible given the ill preparedness of the academic staff.

As some universities and colleges were closing down and academics glued in shock, a few universities used the uncertainty to their advantage (Rashid & Yadav, Citation2020). Every crisis is an opportunity (Sébastien Godinot, Citation2015)! The PNGUoT did not sleep on this opportunity; 80% of in-person face-to-face instructions were shifted to online mode while the 20% laboratory component was delivered in-person with social distancing measures prioritized. It was a time for experiment, forceful acceptance and adoption, for there was no option left apart from emergency remote provision. At the outset, staff seemed unprepared for the new challenge; resistance for change was a norm among some academic staff, while “it is possible and doable” mentality engulfed the Senior Executive Management Team (SEMT). Several virtual trainings were conducted on the usage of learning management systems (LMSs), executive support from the SEMT was offered, academic staff with exceptional knowledge and digital learning skills were given the chance to showcase their potential, and students were appropriately oriented and encouraged to learn remotely. Adequate psychological preparation was done, a thing that made online adoption at PNGUoT a natural course.

This emergency remote provision was abrupt, and in many cases, a shift to remote classes preceded no contingency plan. However, it is not unwise to observe that the campus closure and sudden switch from in-person face-to-face education to remote instructions is just a baby step experiment in the long journey to offering online education. The educational institutions globally face a challenge to adapt to this change and trying to choose the right technologies and approaches for educating and engaging their students (Rashid & Yadav, Citation2020). This stands to reason that, for HE to survive during and after the pandemic, there is a need to invest in online teacher training, and build context-specific LMSs. Provision of fast internet to academics, and extension of digital support to students should also be prioritized. Efforts should also be spent on making online learning an alternative to the on-campus face-to-face learning mode as a suitable and reliable substitute for teaching and learning engagements capable of meeting the intended learning outcomes.

3. Purpose of the study

The study intended to examine the effect of age difference, staff, and students’ attitude, ICT support, and security and users’ trust on e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT.

4. Null hypothesis (Ho)

It is hypothesized in this study that; antecedents such as age difference, attitude, ICT support, and security and users’ trust in e-learning platforms do not significantly affect e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT.

5. Conceptual framework

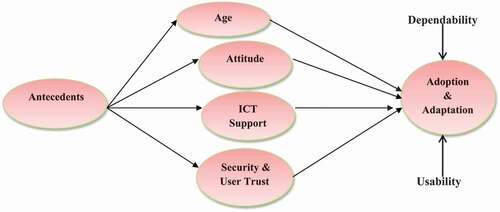

According Richard (Citation2010) as cited in (Fred Ssemugenyi et al., Citation2020), a conceptual framework is an analytical tool with several variations and context. It sets the stage for the presentation of a particular research question that drives the investigation being reported based on the problem statement. below shows how the antecedents jointly explain e-learning adoption and adaptation in HE.

Figure 1. A conceptual framework showing the link between the antecedents, moderators, and consequences

It is important to note that, this study recognizes the fact that technology acceptance in HE has been widely investigated whilst using the existing management information systems models (MISs) such as the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) by Fishbein & Ajzen (1975), the TAM by Davis (Citation1989), the UTAUT by V. Venkatesh et al., (Citation2003), to name but a few. One would expect this study to have adopted or utilized one or more of these models to explain the level of online learning acceptance, adoption, and utilization at PNGUoT. However, it should be remembered that with thousands of studies using these theories, their contribution to knowledge has reached a plateau (Aviv Shachak et al., Citation2019). Their credence as well as their predictive power to technology diffusion and implementation is already known (Holden & Karsh, Citation2010). A recent search of Web of Science retrieved more than 12,000 articles citing (Davis, Citation1989) original TAM paper and over 7700 citations for (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003) UTAUT article. These studies are reasonably consistent with several common themes that are reverberating through them. For specificity, at PNGUoT, the technology acceptance and use models (TAM, UTAUT, TRA, & TPB) have been at the forefront to predict the rate of technology acceptance in the internal University processes over time (Brian, Citation2015; William, Citation2015; Peter, Citation2014; George, Citation2017). These studies corroborate with earlier studies with a positive and significant effect on technology use and acceptance. Against this background, the researchers in this study chose to drop the adoption of any of these models because of their being over researched and the fear of yielding similar results. This study addressed four constructs (i.e., age, attitude, ICT support, & perceived trust and security of the learning management systems) age and attitude being part of TAM and UTAUT, while ICT support, and the perceived trust and security of LMSs as new contextual parameters with probable predictive power.

6. Literature review

This study critically examined the existing body of literature by unearthing gaps, contradictions and congruence among the previous researchers. Literature review can be conceived of as an argument, a debate between the investigator and the audience, in which statements or propositions are made first by the researcher in the form of assertions that a particular problem is interesting, worth investigating by means of specific methods, and amenable to interpretation by the theories suggested by the author (Compte & Preissle, Citation1993), cited in Amin (Citation2005).

6.1. The effect of age difference on e-learning adoption and adaptation

Although there is relentless debate about the e-learning adoption antecedents, there is little disagreement that age is a core predictor of e-learning acceptance and adoption (Kusumaningtyasa & Suwarto, Citation2014; Hadri et al., Citation2020; & Jenny Meyer, Citation2008). The existing body of literature is blessed with shaky but defensible and provocative arguments on how age predicts e-learning acceptance and adoption. Whereas it may sound obvious that the older a person becomes the wiser and more skillful too, Singer and Rexhaj (Citation2007), it is unwise to underestimate the youths’ ability to adapt to technology. Although literature in support of old age presents a compelling and absorbing narrative, that is skillfully threaded and cogently argued, there is no reason to deny that young age adopts faster than their counterpart. Nilsson and Paliwoda (Citation2005) & Indarti and Rostiani (Citation2008) agree that the speed at which young age adopts technology is imaginable. Correspondingly, J. Meyer (Citation2011), while analyzing age structure of the workforce and the adoption of significantly improved technologies, observed that employees younger than 30 were more responsive to new technology than older employees. Although this may sound so simplistic and obvious, on the contrary, one should not forget that most demographic (age-related) studies, irrespective of the variables and the problem under investigation, tend to favor young age.

Turning our attention briefly to PNG, it is evident that literature on age and technology adoption in HE is sparse and anecdotal. This may be the case because technology integration in the teaching and learning process is relatively new in this country. However, this notwithstanding, there is compelling observable evidence that represents several common themes to the effect that age could be a core predictor of technology adoption in this part of the world. Kretchmer (Citation2020), in his paper on the digital revolution in the Pacific Islands, observes that 48% of internet users are young and with increased digital transmission in the region the number may double. Consistently, Kelegai and Middleton (Citation2002) submit that the youth are inquisitive to learn anything technologically driven than the aged ones. While this citation may be regarded obsolete in the context of time, it should be noted that recent researchers such as Nassar et al., (Citation2019), & Hadri et al., (Citation2020) have all corroborated this observation.

One thing that can be mentioned with the highest degree of confidence is that studies with noticeable flashes of scholarly rigor and a good dose of compelling statistical evidence favoring old age via technology adoption are myriad. For example, Hao et al. (Citation2019), Anderson & Perin, Citation2017and Melinda Heinz (Citation2013) all independently found out that old age is a good predictor of technology adoption. On the account of evaluation, it is essential to note that technology adoption may not necessarily be driven by age, but rather by human preparedness to nourish their digital desires at any level in their lives.

6.2. The effect of attitude on e-learning adoption and adaptation

Attitude is a hypothetical construct that cannot be observed directly, but can be inferred from measurable reactions to the attitude object (Ajzen, Citation1993). Conversely, Joseph (Citation2013) defines attitude as nothing but rather individual’s disposition to react with certain degree of favorableness or unfavorableness to an object, behavior, person, situation, or event or to any other discriminable aspect of the individual’s world. Although there is no consensus on the universal definition, there is observable agreement that attitude is perception-oriented. The way people look at things is guided by their moral sense of judgment (Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1977). While analyzing students’ attitudes on the effectiveness of online learning at the tertiary level, Obaid Ullah et al. (Citation2017), found no significant relationship between students’ interest in computer and easiness in using online learning tools at undergraduate level. However, it should be noted that Obaid and his colleagues only adopted a closed 5 points Likert scale questionnaire in their study with no counter data collection technique to triangulate the findings. Like all surveys, the validity of the Likert scale attitude measurement can be compromised due to social desirability. In light of this, Obaid’s study findings are prone to errors and open to criticisms simultaneously.

Bhuasiri et al., (Citation2012) while examining the factors affecting online adoption in the developing countries, established that online adoption was widely affected by students’ characteristics. This observation differs from Aixia and Wang (Citation2011) who opines that students’ online adoption is affected mostly by students’ learning levels and skills in the computer rather than attitude. However, on the basis of scholarly appraisal, it is clear that Aixia forgets that it is still attitude that drives students’ computer skill acquisition. This stands to reason that a positive attitude is critical to online adoption.

In light of this sub-variable and given the emerging realities in HE, researchers in this study submit that attitude is not enough to justify online adoption. Whether students’ attitude via online learning is positive or negative, we need not forget that online learning has become an integral part of the universities curriculum learning processes. A new reality of online teaching has emerged, Hasan et al., (Citation2020); aligning technology and pedagogy in tune with students’ interest and learning preferences is our central focus as academics, Schoonenboom (Citation2012); resistance to change was justifiable then but not anymore (Sanford & Oh, Citation2010). The practical usage of video conferencing platforms, such as WebEx, Zoom, Google Meet, and LMSs like Moodle, Blackboard among others, Hasan et al., (Citation2020) are legitimate learning avenues of the new order.

6.3. The effect of ICT Support on e-learning adoption and adaptation

While several studies have been conducted on the influence of students’ perception on e-learning acceptance and adoption in HE as indicated by Khan et al., Citation2021 there is paucity of research on the effect of ICT support on e-learning acceptance and adoption. A few studies indicate that inadequate ICT support is the core reason why e-learning is still a jock in most universities worldwide. Habibu et al., (Citation2012), while addressing the difficulties teachers face using ICT in teaching-learning at technical and higher educational institutions in Uganda, revealed that: lack of genuine software, low bandwidth, and limited technical training skills, are all conspiring to limit e-learning adoption. Consistently, Williams et al., (Citation2000) state that the essential factors hindering e-learning adoption are; lack of access to technology, limited technical knowledge, and skill, lack of on-site support, among others. Indeed, lack of expert knowledge in e-learning and the cost of ICT training materials have staged a barricade to technology integration in the standard curriculum (Pelgrum & Law, Citation2003; Mumtaz, Citation2000; Sharma, Citation2003; Zziwa, Citation2001; Malcolm & Godwyll, Citation2008). Whereas there is a good deal of consistency in the literature on the developing countries, it may be unwise to imagine that the same story is much present in the developed world. As universities in the Third World struggle to have stable internet and have their academics trained and introduced to online learning, science-based universities in the developed world are delivering online laboratory sessions with much ease (Al-Balas et al., Citation2020). They add that, with reasonable difficulties, medical schools in Jordan were able to switch their on-campus practical and theory sessions to online during the lockdown. Goldberg and Dintzis (Citation2007) claim that Johns Hopkins University had, before the Covid-19 crisis, embarked on blended practical sessions for engineering students. Gamage et al., (Citation2020) further observe that whereas it has been nearly impossible to conduct practical sessions, most universities in Europe and the United States of America have tried and are still trying to make it possible.

Regrettably, it is interesting to note that a couple of universities claiming to have mastered the provision of online learning were seen panicking during the lockdown, for they could not comfortably shift to online learning platforms. This sudden “viral tsunami” exposed the internal operating weaknesses of so many universities, and at the same time, granted other universities opportunities to venture into the online learning business for the very first time. Adeyemi Oginni (Citation2020) insists that if it were not for Covid-19, the Nigeria’s much advocated and awaited paperless economy and smart city agenda could not have taken shape. He adds that for the first time in the history of Nigeria, the educational sector is rapidly evolving to ensure continuity in the training of students whilst keeping abreast with the times.

Whereas this may be the case in as far as the University of Lagos is concerned and a few other universities within the continent, it should not be forgotten that the majority of the universities in the developing countries lost direction in the wake of the pandemic, whilst students from less advantaged backgrounds suffered a great deal. Di Pietro et al. (Citation2020) reiterates that poor ICT infrastructure, funding challenges, and resistance to change miserably hit HE in the developing countries during the pandemic. While analyzing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system in the developing countries, Tiruneh (Citation2020) as cited in Seble Tadesse et al., (Citation2020) consistently reports that in Ethiopia, more than 80% of the population live in rural areas with limited or no access to electricity, pivoting to online learning during the lockdown was merely impossible.

In PNG, the situation was equally tense; “annus horribilis” is a befitting phrase for the year 2020 in as far as HE is concerned. It is a “numero uno” crisis that suddenly engulfed and pushed HE in PNG into a panic mode never before seen in the country’s history of university education. Whereas some universities like PNGUoT and Divine Word had long integrated technology in their standard curriculum and introduced their academic staff to the basics of e-learning, the Covid-19 knock was too heavy to withstand. Left with no hope, drowned in panic, actors traumatized, the Covid-19 intensity surprisingly lessened and the tremor subsidized in the country. This granted universities with some past encounters of e-learning experience an opportunity to strengthen their e-learning undertakings in preparation for hard times. At this point in time, HE in PNG was technologically reshaping. What a moment of change!

6.4. The effect of security and user trust on e-learning adoption and adaptation

In the context of online learning, security means that “learning resources are available and unimpaired to all authorized users when they are needed” (Adams & Blandford, Citation2003). Serb et al., (Citation2013) further observe that confidentiality, integrity, and availability are core ingredients of online security. While this is made clear to all users, universities and other colleges of higher learning are rushing into adopting online LMSs without proper evaluation of the security aspects (Alwi & Fan, Citation2010). Consistently, Chen and Wu (Citation2013) note that in a recent survey conducted by Campuscomputing.net and WCET (wcet.info) found that almost 88% of the surveyed institutions had adopted an LMS as their medium for offering online courses. Whereas this is regarded as a technological revolution in HE, it exposes university databases and servers to external threats if no security controls exist. The risk is imaginable, more likely so in cases where university internal processes become too complex to manage without technology. In a business spectrum, Stephen (Citation2001) provides compelling evidence to the effect that online transactions are extremely unsafe. He notes that noticeable online attacks involving financial loss worth $ 1.2 billion USD on outstanding internet sites such as CNN, Yahoo, eBay, and Amazon have been numerous since 2000. Research findings in general have shown that customers’ behavioral intention to use e-commerce websites is significantly influenced by their perception about the level of security control that is embedded in the website, so does in academia (Hua, Citation2009; Belkhamza & Wafa, Citation2009; Shafi, Citation2002).

Trust in online environments exceeds the common meaning of trust to include trust in technically or socially abstract systems (Sydow, Citation1998). The concept of system trust in online environments is basically premised on the aptness of the system in terms of confidentiality, dependability, reliability, and timeliness. Most available LMSs are prone to hacking and are unsafe to aid teaching and learning (Chen & Wu, Citation2013). Universities need to increase stakeholders’ confidence in the adopted online learning platforms by assuring them of confidentiality and aptness if e-learning acceptance and adoption is to take shape in HE. Serb et al., (Citation2013) advise that since there are many users in any online learning environment, both a login system and a strong delimitation marking registered users and user groups are needed to safeguard the access to the appropriate user. In the same spirit, it is reported that on realizing that the number of users had surged during the pandemic from 10 million-300 million in less than five months, Zoom bought a security firm to achieve end-to-end encryption at a broader scale. Upon this development, the New York City Department of Education had to lift the ban on Zoom use for educators as it approved the software’s new security features.

7. Methodology

Research methodology refers to a science of studying how research is systematically conducted (Shanti Bhushan & Shashi, Citation2011). It is a systematic and theoretical analysis of the techniques applied to a field of study. It systematically describes the procedures that have been followed in conducting a study (Olive et al., Citation2003) as cited in Fred Ssemugenyi et al. (Citation2020). With reference to this study, a cross-sectional survey design was adopted because the required data could only be collected at one point in time (Amin M. 2005; Xiaofeng & Cheng, Citation2020; James & Schumacher, Citation2006). Data were collected in sequence by the use of the sequential explanatory mixed method with the view of producing a holistic understanding of the hypotheses under investigation. A self-administered questionnaire embedded in the Google Classroom for students was used to obtain numerical data for this study. A Five-Point Likert Scale questionnaire that gives respondents an option to be neutral rather than having to choose an alternative that does not reflect their thinking (Johns, Citation2005; Lozano et al., Citation2008) was utilized in this study purposely to control the margin of error that is usually associated with other Likert scales (Amin M. 2005). This tool was found suitable in examining peoples’ perceptions and opinions, and the factors that influence them.

To minimize the degree of bias that is usually associated with the restricted Likert-numerical responses, interviews were held as a cross-verification strategy to increase control, generalizability, confidence, and validity of the study findings (Tashakkori & Teddle, Citation2003). Triangulation is used when the strengths of one method offsets the weaknesses of the other, so that together, they provide a more comprehensive set of data. The interview sessions of each participant were transcribed to identify patterns, assign codes, and subsequently develop themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The themes included personal attributes (PATS) for hypotheses on students’ age and attitude, program support (PLSs) for hypothesis on ICT support, and trustworthiness (TSWT) for security and users’ trust.

8. Study population and sample size

Concerning research context, population refers to an aggregate or totality of all the objects, subjects, or members that conform to a set of specifications (Pilot & Hungler, Citation1999; Olive et al., Citation2003). Sample size on the other hand refers to a statistical representation of the target population (Creswell, Citation2003). Using an online survey for Semester 1/2000, the study obtained primary data from 169 undergraduate students and 44 online facilitators. To avoid sampling errors and/or bias, and for the sake of generalizing the study findings, the survey was made open to all students whose learning load at the time of the inquiry was already uploaded and delivered exclusively via the Google Classroom-Learning Management System. Whereas one may challenge this sample selection on the basis that the total population of undergraduate students in PNGUoT is approximately 3000, and so 169 respondents do not statistically represent 3000, he/she should be reminded that 169 respondents only represented a handful of students whose course learning materials at the time of the survey had already been uploaded and delivered exclusively online. The Five-point Likert scale was used to collect numerical data from 169 students, while interviews were applied to the 44 online facilitators.

9. Eligibility criteria

These criteria specify the characteristics that people in the population must possess in order to be included in the study (Pilot & Hungler, Citation1999). With reference to this study, two categories of respondents took prominence (the online facilitators and undergraduate students). For the facilitators, these criteria were used; only PNGUoT undergraduate lecturers whose subjects at the time of the survey had been uploaded and delivered via Google Classroom, having the ability to deliver lectures synchronously via web-based video conferencing tools such as Zoom and Cisco Webex, and with the ability to record lectures using Camtasia Screening Software Program. For the students, concentration was only on undergraduate students of PNGUoT whose learning at the time of the survey was either received via Google Classroom or web-based interactive software.

10. Findings of the study

Findings of this study are logically presented in accordance with the key antecedents which researchers during the conceptual phase believed were more paramount in predicting e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. The same parameters (age difference, attitude, ICT support, and security and trust) guided the construction of the online data collection tools and the interview guide.

10.1. The effect of age difference on e-learning adoption and adaptation

The researchers in this study wondered if the adoption rate of e-learning at PNGUoT was not as a result of the age-difference hitherto existing among students and that the adoption of e-learning would not revolutionize teaching and learning at the University. To examine this narrative beyond any reasonable doubt, the researchers tested the aforesaid null hypothesis (Ho) to establish any possible links between age-difference and e-learning adoption. Conversely, with the help of SPSS (version 16.0) a simple linear regression analysis was employed to determine the impact of age difference on e-learning adoption and adaptation.

Whereas age and e-learning adoption seldom meet (Fleming et al., Citation2017), the regression results in above reveal that age has a positive and significant effect on e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. This is justified by the F-values and p. values (F = 2.082, p. = 0.006) in the above table. Since the p. value (0.006) is less than (0.05) which was the minimum level of significance required to declare a significant effect, the null hypothesis was rejected while the alternative was accepted by default. Implying that age variation significantly affects e-learning adoption and adaptation at the PNGUoT, contrary to what the researchers had hypothesized in the conceptual phase. The Beta value (0.180) suggests that a 1% increase in one’s age, increases the chances of e-learning adoption and adaptation by 0.180 which is significant at t = 9.206 and Sig. = 0.038. While the constant value 1.207 with corresponding t = 13.232 and Sig. 0.022 indicates that students’ e-learning acceptance and adoption can still be high irrespective of their age.

Table 1. Simple linear regression analysis on the effect of age difference on e-learning adoption and adaptation

10.1.1. Interview responses

Drawing on the thematic analysis of the qualitative part of the questionnaire, interview responses on whether age-difference significantly affects e-learning adoption and the teaching and learning processes were obtained to countercheck the validity of the numerical results. The interview responses of each participant were transcribed to identify patterns, assign codes, and subsequently develop themes. Personal attributes (PATS) were identified as a suitable theme for responses on age-difference and for the purposes of confidentiality, names of the participants were provided as pseudonyms in two categories (PATS1, & PATS2). These were grouped basing on the commonalities reverberating through their responses on age-difference as a possible predictor of e-learning adoption. PATS1 consisted of 31 participants whose responses did not find age-difference as a true predictor of e-learning adoption and an influencer of the teaching and learning processes. In comparison, PATS2 consisted of 13 participants with positive responses.

There was unanimous consensus from all the PATS1 participants that age-difference does not positively and significantly affect e-learning adoption and the teaching and learning processes. They noted that

variables beyond age have unbelievably triggered our reaction to technology; due to fear of rendering us obsolete, we had to quickly embrace technology since it was the only way possible to deliver lecturers to our students, and a demonstration that we are technologically compliant.

while it may seem reasonable to claim that older adults use digital technology less than younger generations, the digital migration anxiety hit all of us the same way during the pandemic.

Technological progress in HE is constant, forcing all of us to adapt. The difference in the rate of adoption between students and facilitators is quite negligible if any, and the extent to which e-learning influences teaching learning processes is unknown at the moment.

Although the influence of their responses was negligible, the PATS2 participants unanimously observed that age-difference has a positive and significant effect on e-learning adoption. They noted that

it is widely appreciated that older people are not tech-savvy, and their level of appreciation is low as opposed to that of the youths. It is quite evident here at PNGUoT; our students adapted very fast than the academics, and the relatively younger academics were equally swift in the transition process as opposed to their counterparts.

it is not uncommon that ageism work against the willingness to use digital technologies; the belief that technology is only for the digital natives has denied most of us (digital immigrants) the opportunity to adapt very fast to the new normal in the teaching and learning context. Many times, technology plays up in the middle of the lecture only to be rescued by our students.

In conclusion, whereas age was found to be statistically significant, the interview responses from the majority of the key informants disputed it. Given that responses obtained from the key informants usually receive much weight, it may be wise therefore to conclude that age-difference does not significantly and positively affect e-learning adoption at the PNGUoT. In addition, the contention whether technology adoption revolutionizes teaching and learning processes or not is still a myth at the moment, for no clear evidence was offered.

10.2. The effect of attitude on e-learning adoption and adaptation

This study further intended to establish the impact of attitude on e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. To establish whether staff and student attitude affects e-learning adoption and adaptation, a null hypothesis was tested. Hypothetically, the study assumed that attitude among staff and students does not affect e-learning adoption and adaptation. While utilizing SPSS, a simple linear regression analysis was employed to establish whether e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT is a function of attitude. Results of this analysis are here below presented in .

Table 2. Simple linear regression analysis on the effect of attitude on e-learning adoption and adaptation

The regression analysis results in reveal that students’ attitude had a significant positive effect on e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. This is explained by the F-values and p. values (F = 315.854, p ≤ 0.001) in the above table. Since the p. value was below the calculated probability (0.05) which was, in this case, the minimum level of significance required to declare a significant effect, the null hypothesis was rejected while the alternative was accepted− suggesting that attitude significantly and positively affects e-learning adoption and adaptation. It is further revealed that attitude accounts for 55% variation in e-learning adoption (r2 .550), above the value (45%) of the excluded variables. The Beta value of 0.442 suggests that a 1% increase in the determinants of one’s attitude via online aptness (usefulness, access, and technology-user support) increases the chances of e-learning adoption by 0.442, which is significant at t = 17.772 and Sig. = 0.000. On the other hand, the constant value of 1.514 with a corresponding t = 22.636 and Sig. = 0.000 indicates that e-learning adoption and adaptation can still be high irrespective of student and staff perception towards online learning. Implying that while positive attitude is paramount in matters to do with e-learning adoption, other factors are equally important.

10.2.1. Interview responses

Interview responses on whether facilitators’ attitude positively and significantly affects e-learning adoption and eventual adaptation were obtained to increase control, generalizability and validity of the findings. As a requirement for qualitative analysis, responses from the participants were coded, and themes developed. Just like age, Personal attributes (PATS) were found to be a suitable theme for attitude. The responses were categorized into three groups depending on the level of resemblance in their responses. PATS3 consisted of 33 participants with almost similar responses, PATS4 had only 8 participants with opposing responses, while PATS5 had 3 participants with neutral positions.

The PATS3 participants revealed that attitude, positively and significantly affected e-learning adoption and the eventual adaptation. They noted that

technology adoption and its sustained usage in higher institutions of learning depends largely on the end users’ attitude to using technology in their daily teaching and/or learning activities. We have all welcomed technology because it is clear that it is the only way to remain relevant in the face of the pandemic.

one thing that is consistently persistent in HE today is technology use, and its importance via academic excellence cannot be overemphasized. We are embracing it, and we shall always rely on it to transform instruction, keep connected to the online community of inquiry and open learning resources.

they again submitted that ‘usefulness, access, and ease of use’ are the most critical dimensions influencing both staff and students’ attitude to utilizing technology in the teaching and learning processes. For instance, the web-based video conferencing online learning platforms such as Zoom, Cisco Webex among others are straightforward to use; this explains why the majority of the staff and students opt for them as opposed to LMSs.

The PATS4 participants observed that attitude has nothing to do with e-learning adoption and adaptation at PNGUoT. They noted that;

for our case at PNGUoT, attitude may be the least aspect to think of; what influences e-learning adoption is far much bigger than our attitude. Can our attitude stop the University from funding e-learning project? Can technology stop to function because our attitude is negative? Let the University Management play its part, the rest is simple.

On the other hand, the PATS5 participants were neither positive nor negative in their responses. They noted that;

whether attitude affects e-learning adoption or not, it is not so important at the moment; the focus, should be on meeting the basic requirements to enable us deliver online with ease.

hardily can teachers’ or students’ attitude stop University Management from meeting their intended objects. As long as it is part of their agenda, whether staffs ‘attitude is supportive or not, it works

In conclusion therefore, the majority of the respondents (both quantitative and interview) in as far as hypothesis two is concerned, to a great extent agreed that attitude is a dominant predictor of technology utilization in the teaching and learning process. In view of this observation, it is not unwise to assume that any slight increase in technology usefulness, access, and technology user-support (indicators of attitude) will attract a similar corresponding effect on e-learning adoption. Therefore, promoters such as the SEMT and other key stakeholders should put much effort into mindset transformation as one of the ways to embark on this inevitable undertaking in these times of the pandemic and for the years ahead.

10.3. The effect of ICT support on e-learning adoption and adaptation

A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to determine the effect of ICT support on e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. ICT support was considered the predictor, while e-learning adoption and adaptation were the predicted variables. Results of the simple linear regression analysis are presented in .

Table 3. Simple linear regression analysis on the effect of ICT support on e-learning adoption and adaptation

results indicate that ICT support explained 65.8% variation in e-learning adoption and adaptation (r2 = 0.658). This means that the excluded variables from the regression model summary account for only 34.2%. The null hypothesis, in this case, was rejected because it was found out that ICT support significantly and positively predicts the rate of e-learning adoption in PNGUoT. This is clearly explained by the (F = 121.132, p ≤ 0.001) in the above model summary. Since the p. value is less than the calculated probability (0.05) which is the minimum level of significance required to declaring a significant effect, the null hypothesis was rejected. The Beta value 0.376 suggested that a unit increase in the provision of ICT support by the university management, increases the chances of e-learning adoption by 0.376 which is significant at t = 11.006 and Sig. = 0.000, respectively. However, the constant value of 1.731 with a matching t = 19.957 alongside Sig. 0.000 points to the fact that whereas ICT support is critical in determining the rate of e-learning adoption in PNGUoT, other factors outside this model summary (34.2% for precision) deserve attention too for the smooth implementation.

10.3.1. Interview responses

To validate the reliability of the numerical results provided in above, the researchers collected qualitative data in the form of interviews from 44 participants. Their responses were coded, patterns formulated, and themes developed. Upon their responses on hypothesis three, Program support (PLSs) was identified as a suitable theme for ICT support. The responses were categorized into two groups (PLSs6 & PLSs7) depending on their similarities and uniqueness. The PLSs6 responses represent 39 participants with the view that ICT support adequately predicts e-learning adoption and adaptation, while PLSs7 responses represent 5 participants with divergent views.

At the time of the inquiry, the PLSs6 participants demonstrated that e-learning adoption and adaptation had a positive and significant bearing on ICT support. They noted that;

the success or failure of online learning lies within the mental frame of the change agents. We are all excited and very inquisitive about e-learning because the SEMT is more than committed to ensuring that all conventional courses (practical and theory-based) are delivered exclusively online. Trainings on technology use, ICT infrastructure, support centres, and funding are all reasonably provided by the University Management.

whereas the University is very supportive, there is an urgent need to contextualize this support. Departments are completely unique, so are their needs.

the practical-based academic programs need access to virtual laboratories, simulation software, and a careful selection of an LMS that suits their uniqueness. The University Management and the Online Project team need to double their support on this.

we appreciate the role of technology in HE, more so in this era of the pandemic, but some of us are completely lost in this new wave of technology. The ICT support provided so far is good but we need more if we are to compete with other open universities.

On the contrary, the PLSs7 participants noted that;

we are in the digital age, whether the University supports or not it is just automatic that technology integration in the teaching-learning processes is inevitable. Teaching and technology are intertwined; what kind of teaching can you mention today without technology!

internet is almost becoming a human right, so does technology in education for both teachers and learners. It is a constant variable, by all means, it is meant to be available. No one should start bragging about this! It is meant to be like that, simple.

Therefore, to implement e-learning successfully in PNGUoT, the key actors will need to pay relatively more attention to ICT support since it has proved in this study to be the most critical aspect (r2 = 0.658) in predicting e-learning adoption. The management team needs to accept the responsibility for identifying the University’s current and future needs in e-learning, and be ready to support the entire process from the initial stage through to full adoption. In the same regard, the management team together with the heads of department need to keep themselves permanently up to speed with technological advances as a strategy to inspire confidence in staff and students, equip them with the necessary e-learning tools, facilitate the acquisition of knowledge through up-skilling pieces of training, and drive innovation and creativity.

10.4. The effect of security and trust on e-learning adoption and adaptation

During the conceptual phase, researchers hypothesized that the security and trust staff and students have in online learning platforms does not significantly affect e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. To guide this kind of reasoning to the desired end, a null hypothesis was tested. In addition, with the help of SPSS, a simple linear regression analysis was run to establish the impact of security and trust on e-learning adoption in PNGUoT.

The regression results in show that security and trust significantly affect the rate of e-learning adoption in PNGUoT. The table above shows that security and trust explained 49.5% variation in e-learning adoption (r2 = 0.495), while the excluded variables from this model accounted for 50.5%. The null hypothesis was rejected because the p. value (p ≤ 0.001) was less than the calculated probability (0.05), which was the minimum level of significance required in this study to declare a significant effect. The Beta value of 0.494 indicates that a 1% increase in security and trust increases the chances of e-learning adoption by 0.494, while the constant value of 1.364 with corresponding t = 13.141 and Sig. = 0.000 shows that apart from security and trust, other factors outside this model summary equally affect e-learning adoption and adaptation at the PNGUoT. Therefore, implementers need to be cognizant of this reality and take care of these factors as well.

Table 4. Simple linear regression analysis on the effect of security and trust on e-learning adoption and adaptation

10.4.1. Interview responses

The researchers further triangulated the numerical data with the interview responses obtained from 44 participants in order to develop a holistic understanding of the phenomenon (H0 4) under investigation. After a careful study of the response pattern, trustworthiness (TSWT) was identified as a suitable theme for security and users’ trust. For confidentiality, the names of the participants were provided as pseudonyms in two categories (TSWT8, & TSWT9). The TSWT8, included 28 participants, while TSWT9, 16. These were grouped as per the degree of resemblance in their responses on (H0 4).

The TSWT8 category observed that e-learning adoption and adaptation positively and significantly affected security and users’ trust during the inquiry. They noted that;

security and trust are fundamental aspects in the long journey of technology adoption and eventual adaptation.

technology adoption and usage has a close bearing on the user-confidence. As long as the available technology is fit to aid the attainment of the learning outcomes in a feasible manner, then consumer acceptance becomes obvious. we have confidence in our home-grown LMS-tSMAS, for example, because we are pretty sure of its safety.

whereas the available LMS is safe and fit for the theory-based programs, hardily can it support learning in science and engineering departments. There is an urgent need to have context-based LMSs that are extremely safe and tailored to our uniqueness.

some of the web-based platforms like Zoom (at the time of the inquiry) were prone to cyber-attacks, a vice that renders the platform unreliable, yet they are the most user-friendly at the moment. They are good at synchronistic engagements, but their safety is still questionable!

the absence of proctoring software makes it hard to guarantee integrity and fairness in the students’ formative and summative assessments. There is an urgent need of embedding proctoring into the available LMSs to increase user confidence and acceptance. Now that the University is in the final stages of obtaining proctoring software, our confidence levels are getting high.

While on the other hand, TSWT9 reported that;

all online learning systems are susceptible to hacking, whether Moodle, Canvas, or our tSMAS, the story remains the same. At least, there is enough evidence that most of these things are unsafe.

our confidence in systems should not be on their safety, rather on their ability to aid learning. What are we hiding anyway! Being so particular with safety features may imply that our primary responsibility has shifted from teaching/imparting knowledge to something else.

why must we emphasize security! It looks a misplaced agenda; our concern is to have a suitable LMS for teaching and learning. Whether it is hacked or not what do we lose? Unauthorized access for illicit motives cannot be avoided, and should not be part of the conversation at the moment

In conclusion, it is appropriate to note that although practitioners are very much willing to integrate technology in the teaching and learning processes, safety issues still worry them. The University Management is thus advised to imbed security features like the lockdown browser during examinations, and also encourage staff to use web-based learning platforms that have end-to-end encryption with their cryptographic keys undisclosed on their servers.

10.5. The total effect of antecedents on e-learning adoption and adaptation

Rarely, can a dependent variable be sufficiently explained by only one variable. Multiple regressions are used because they give room to other independent variables to explain why the dependent variable is the way it is. In this study, a multiple linear regression analysis was purposely employed to compare and rank all the four predictor variables in their order of importance and also to establish the extent to which each of the four predictors influences e-learning adoption in PNGUoT. To understand the predictive power of the independent variables upon the dependent variable, the following equations were used;

10.5.1. Functional equations

From EquationEquation (1)1

1 , the mathematical equation was formed as;

Where;

= the constant, or the level of e-learning adoption one is expected to be at, when the level of all other factors is taken to be zero.

: Refer to age difference, attitude, ICT support, and trust and security, respectively. Also referred to as the predictors in this model.

: Refer to the regression parameters, measuring predictive strength the respective explanatory (independent) variables have on e-learning adoption (dependent variable).

: Is the error term, which stands for model errors (measurement errors and functional estimation errors) such as other factors left out in this multiple linear regression model. In estimating the extent to which the dependent variable (e-learning adoption) is predicted by the independent variables (

),

was assumed to have a normal distribution with a mean of zero. Actual multiple linear regression analysis was done using SPSS, results of which are presented in .

Table 5. Multiple linear regression analysis on the effect of antecedents (age, attitude, ICT support, and security & trust) on e-learning adoption and adaptation

Researchers in this study had hypothesized that age, attitude, ICT support, and security and trust do not significantly and positively affect e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT. The results in show that, when all the four predictor variables were taken together, explained 57.3% variations in the dependent variable (adjusted r2 = 0.573). This means that only 42.3% takes care of the excluded variables. From the table still, it is clear that the regression model was significant (F = 29.116, p ≤ 0.001) because the p. value was less than the calculated probability of (0.05) which was the minimum level of significance required in this study to declare a significant effect and thence the null hypothesis was rejected.

Considering the coefficients section of , results indicate that while all the four predictors significantly influence e-learning adoption, their predictive strength is not equal. For example, results show that of the four predictors, two factors are taking the lion’s share ICT support (Sig. 0.000) and attitude (Sig. 0.001). These two were followed by security and trust (Sig. 0.002), while age (Sig. 0.027) had the least influence. Thus, from the estimated regression model, one can confidently say that, a unit increase in attitude and ICT support is likely to increase e-learning adoption by 0.521 and 0.487, respectively, considering other factors constant. Therefore, it is advisable that the University Management puts much effort on changing the attitude/perception staff and students have on e-learning, and at the same time provides ICT support if e-learning implementation is to become a successful story.

11. Discussion

The role of technology in shaping higher education today is not contestable (Buabeng-Andoh, Citation2012; Norton et al., Citation2000;; Parker et al., Citation2008). While this observation may be regarded obsolete on the basis of time, it should be noted that recent studies such as (Wendy Green et al., Citation2020; and Michael; Gaebel, Citation2020) have all corroborated this observation. The findings of this study find refuge in these previous observations as well. This study notes that one of the most powerful predictors of e-learning adoption is attitude; positive attitude drives peoples’ responsiveness to innovation and their rate of adaptation. It is believed that if teachers perceived technology programs as neither fulfilling their needs nor their students’ needs, it is much more likely that they will not integrate the technology into their teaching and learning processes. This is consistent with Peter K. et al., (Citation2016) whose aim was to establish if ICT adoption had any bearing on lecturers’ attitude in the University of Port Harcourt-Nigeria. Their study established a significant and positive correlation between attitude and ICT adoption. Although one can challenge their findings on the basis that their data collection tools showed low reliability coefficients (e.g., 0.67, 0.62, & 0.51) as per the Cronbach Alpha method, and going against a statistical rule of using t-test when the study population was more than 30, it is important to note that, attitude as a variable, received much attention in their study. It is upon this basis that their findings are cross-referenced in this study.

Even though Yusuf and Onasanya (Citation2004) and Palloff and Pratt (Citation2007), observed that staff and students’ online presence is incumbent upon their attitude, Korte and Husing (Citation2007) in an empirical survey submit that some European teachers’ attitude was found to be negative because they failed to establish the value of technology in learning. Congruently, a survey on the UK teachers also revealed that some teachers’ positivity about the possible contributions of ICT was moderate as they were more ambivalent about the specific role of technology in stimulating students’ cognitive abilities (Becta, Citation2008). Whereas this may be the case, this study on the other hand corroborates with so many earlier findings such as Hew and Brush (Citation2007), Keengwe et al. (Citation2008), Teo (Citation2008), and Demirci (Citation2009), which found positive attitude to be a core predictor of technology adoption in the teaching and learning processes.

In addition, ICT support has also proved to be another critical aspect of e-learning adoption in PNGUoT. In this study, ICT support was conceptualized as access to ICT infrastructure and resources, and technical support. Consistently, Yildirim (Citation2007) noted that, access to technological resources is one of the effective ways to teachers’ pedagogical use of ICT in teaching. His observation mirrors the scholarly works of Ssempebwa et al. (Citation2007), Usluel et al. (Citation2008), and Chen (Citation2010). They independently attest that access to ICT is the gateway to a sustainable e-learning culture in a university.

At the time of the survey, the majority of the respondents were happy with the ICT support provided by the University Management through ICTs Department. This justifies the reason why PNGUoT was able to deliver most of her courses online during the most heated, yet ugly times of the pandemic. Previous researchers such as Korte and Husing (Citation2007), Yilmaz (Citation2011), and Buabeng-Andoh (Citation2012) all acknowledge the importance of technical support in the long journey of technology adoption in the teaching and learning processes.

While security and trust had a significant effect on e-learning adoption, its impact was still weak as opposed to attitude and ICT support. This therefore, presupposes that attitude and ICT support unequivocally predict the staff and students’ responsiveness to e-learning than any other aspect. At the time of the study, age difference among students and staff was found to be a weak predictor of e-learning adoption. Implying that one’s age has nothing to do with e-learning adoption at the PNGUoT.

13. Conclusions and implications

Apart from contributing to the current scholarly debate derived from decades of research on e-learning, this study carefully examined the antecedents that seemed unclear during the conceptual phase but clarified much later during the empirical and analytical phases of the same study. Attitude, ICT support, and security and trust emerged as the best predictors of e-learning adoption while age difference revealed no significant effect as per the interview results on e-learning adoption and adaptation in PNGUoT.

The question raised at the outset on whether the pandemic-driven technology adoption in the teaching and learning processes in PNGUoT is a wave of change or a mere change in the wave appropriately addresses in this study. The reality on the ground suggests that the long-awaited innovation in the teaching fraternity has proven to be the only suitable intervention at the moment that can reasonably aide the teaching and learning process in odd times to all students irrespective of their physical locations. However, there is an urgent need to re-examine the context and identify technology that is in conformity with the students’ learning needs, University’s ICT infrastructure, and the teaching needs. Just because a particular technology worked well in some countries and/or universities, does not mean that it can suitably support teaching and learning processes at the PNGUoT.

On the aspect of attitude, it is therefore advisable that promoters such as the SEMT and other key stakeholders put much effort on changing both the staff and students’ attitude if e-learning is to become a successful story and a sustainable undertaking in PNGUoT. It is observed that if the available technology is fit to aid the achievement of the intended learning outcomes, then it is obvious as per the study findings that both staff and students will confidently support it.

On the aspect of ICT support, management team together with the heads of department need to keep themselves permanently up to speed with technological advances as a strategy to inspire confidence in staff and students, equip them with the necessary e-learning tools, facilitate the acquisition of knowledge through up-skilling trainings, and drive innovation and creativity.

There is a need to understand what is working and why, and use this to increase inclusion, innovation, creativity, and cooperation in PNGUoT. Adopting context-specific technologies is fundamental in getting ready for the years ahead. Some of the questions that need immediate answers include: what changes can we anticipate that would allow us to plan better, what aspects will be most crucial to act upon, and what unique features in our context today best define our future. Exposing ourselves to a thought process that flows to imagine dreams and nightmares may help our minds to travel into the unknown thereby allowing ourselves to understand the threats and how to surmount them.

While the impact of the pandemic in HE was abrupt and in the majority of cases there was no contingency plan other than to attempt to continue classes remotely, it is important that we start to consider a way out of this crisis, ensuring the highest degree possible of inclusion and equity. A shift away from the ‘emergency remote teaching” that was fit during the pandemic to real e-learning is urgently needed; with online policy guidelines in place, online instructional technologists employed and empowered, facilitators up-skilled, online modules prepared and uploaded, stable and fast internet installed, and the provision of stable power supply among others.

Even though technology has become an integral part of teaching and learning processes, technical issues in the pedagogical sense remain a big challenge. The on-campus traditional mode of learning is still popular for practical-based courses on grounds that it allows the delivery of learning outcomes in a clearer manner. The cognitive, social, and teaching interactions present in the on-campus mode, make teaching and learning processes natural and lively as opposed to exclusive online learning. To produce dynamic and competitive graduates under online learning stream, there is an urgent need to imbed physical interaction component in the online learning stream (blended learning) as a strategy to neutralize the degree of artificialization associated with digital learning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fred Ssemugenyi

Fred Ssemugenyi is an Associate Professor and Director, Department of Open and Distance Learning at PNGUoT. His research interest is prominent in educational policy, institutional governance and leadership, creative and inclusive pedagogy, educational technology, and institutional intelligence.

Tindi Nuru Seje

Tindi Nuru Seje is an Associate Professor and Director, Department of Teaching & Learning Methods where he promotes an institutional culture that values effective teaching, and meaningful learning. His research interest is dominant in instructional designing, Edtech, and Educational Management and Administration.

References

- Adams, A., & Blandford, A. (2003). Security and online learning: To protect or prohibit. Usability Evaluation of Online Learning Programs, pp.331–27. UK: IDEA Publishing.

- Adeyemi Oginni. (2020). Covid-19 and educational sector: A blessing or otherwise! Thursday, May 21, 2020 8:39:00 AM. Centre for Housing and Sustainable Development, University of Lagos.

- Aixia, D., & Wang, D. (2011). Factors influencing learner attitudes toward online learning and development of online learning environment based on the integrated online learning platform. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and Online Learning, 1(3), 264–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7706/IJEEEE

- Ajzen, I. (1993). Attitude theory and the attitude-behavior relation. New directions in attitude measurement, 41–57. New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888

- Al -Hujran, O., Al-Lozi, E., & Al-Debei, M. M. (2014). Get ready to mobile learning”: Examining factors affecting college students’ behavioral intentions to use M-learning in Saudi Arabia. Jordan Journal of Business Administration, 10(1), 111–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12816/0026186

- Al-Balas, M., Al-Balas, H. I., Jaber, H. M., Obeidat, K., Al-Balas, H., Aborajooh, E. A., Al-Taher, R., & Al-Balas, B. (2020). Distance learning in clinical medical education amid COVID-19 pandemic in Jordan: Current situation, challenges, and perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 341. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02257-4

- Al-Ghaith, W., Sanzogni, L., & Sandhu, K. (2010). Factors influencing the adoption and usage of online services in Saudi Arabia. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 40(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1681-4835.2010.tb00283.x

- Alwi, N. H. M., & Fan, I. S. (2010). E-learning and information security management. International Journal for Digital Society, 1(2), 148–156. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20533/ijds.2040.2570.2010.0019

- Amiel, T., & Reeves, T. C. (2008). Design-based research and educational technology: Rethinking technology and the research agenda. Educational Technology and Society, 11(4), 29–40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.11.4.29

- Amin, E. M. (2005). Social science research: Conception, methodology and analysis. Makerere University Printing Press.

- Anderson, M., & Perrin, A. (2017). Tech adoption climbs among older adults: Technology use among seniors. Pew Research Centre, May 2017. https://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/14/2017/05/16170850/PI_2017.05.17

- Ash, J. S., Berg, M., & Coiera, E. (2004). Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: The nature of patient care information system-related errors. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 11(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1197/jamia.M1471

- Becta. (2008). Harnessing technology: Schools survey 2008. Accessed October 20, 2011 http://emergingtechnologies.becta.org.uk

- Belkhamza, Z., & Wafa, S. (2009). The effect of perceived risk on the intention to use E-commerce: The case of Algeria. Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce, 14(1), 1–10. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242199053

- Bhuasiri, W., Xaymoungkhoun, O., Zo, H., Rho, J. J., & Ciganek, A. P. (2012). Critical success factors for E-Learning in developing countries: A comparative analysis between ICT experts and faculty. Computers & Education, 58(2), 843–855. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.10.010

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brian, J. (2015). Examining the validity of TAM and UTAUT: An ICT adoption appraisal at PNGUoT. Unpublished dissertation, Department of Mathematics and Computer studies.

- Buabeng-Andoh, C. (2012). Factors influencing teachers’ adoption and integration of information and communication technology into teaching: A review of the literature. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 8(1), 136–155. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/Ej1084227.pdf

- Chen, R.-J. (2010). Investigating models for pre-service teachers’ use of technology to support student-centered learning. Computers & Education in Press.

- Chen, Y., & Wu, H. (2013). Security risks and protection in online learning: A survey; The international review of research in open and distance learning. Old Dominion University.

- Compte, M. L., & Preissle, J. (1993). Ethnography and qualitative designs in educational research (2nd Ed.). London: Academic Press

- Creswell, J. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Czuba, J. (2020, April). Future-proofing access, quality and delivery in Papua New Guinea’s Higher Education sector. DHERST Quarterly Newsletter, 3(1), 10. https://web.dherst.gov.pg/images/News/newsletters/DHERST-Newsletter-Revised-080420-1.pdf

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- Demirci, A. (2009). How do teachers approach new technologies: Geography teachers’ attitudes towards Geographic Information Systems (GIS). European Journal of Educational Studies, 1(1), 43–53. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ali-Demirci-2/publication/228343724

- Deopa, N., & Fortunato, P., (2020). Coronagraben. Culture and social distancing in times of COVID-19. UNCTAD Research Paper No. 49; Division on Globalisation and Development Strategies, pp. 1–22, UNCTAD.

- Di Pietro, G. B., Biagi, F., Dinis Mota Da Costa, P., Karpinski, Z., & Mazza, J. (2020). The likely impact of COVID-19 on education: Reflections based on the existing literature and recent international datasets. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Durante, R., Guiso, L., & Gulino, G. (2020). A social capital: Civic culture and social distancing during covid-19. Working Paper 1181, Barcelona Graduate School of Economics,14(5), 1155–1180. https:ideas.repec.org/p/bge/wpaper/1181.html

- EUA. (2020). Preliminary results of the EUA survey on “digitally enhanced learning at European higher education institutions”, presented at the BFUG meeting 71. June. Available at http://www.ehea.info

- Fleming, J., Becker, K., & Newton, C. (2017). Factors for successful e-learning: Does age matter?”. Education + Training, 59(1), 76–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2015-0057

- Gaebel, M. (2020). European higher education in the Covid-19 crisis. International Association of Universities.

- Gamage, K. A. A., Wijesuriya, D. I., Ekanayake, S. Y., Rennie, A. E. W., Lambert, C. G., & Gunawardhana, N. (2020). Online delivery of teaching and laboratory practices: Continuity of university programmes during COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 10(10), 291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10100291

- George, T. (2017). On the road to ICT adoption: Examining the validity of TAM in higher education context in Papua New Guinea. Unpublished dissertation, IT Business Studies-PNGUoT.

- Godinot, S., (2015). From crisis to opportunity: Five steps to sustainable European economies. WWF Report. https://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net

- Goldberg, H. R., & Dintzis, R. (2007). The positive impact of team-based virtual microscopy on student learning in physiology and histology. Advances in Physiology Education, 31(3), 261–265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00125.2006

- Green, W., Anderson, V., Tait, K., & Tran, L. T. (2020). Precarity, fear and hope: Reflecting and imagining in higher education during a global pandemic. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1309–1312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1826029

- Habibu, T., Abdullah-Al-Mamum & Clement, C. (2012). Difficulties faced by teachers in using ICT in teaching-learning at technical and higher educational institutions of Uganda. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT), 1(7), 1–9. September 2278-01811. www.ijert.org.

- Hadri, K. U. S. U. M. A., Muafi, M. U. A. F. I., AJI, H. M., & Sigit, P. A. M. U. N. G. K. A. S. (2020). Information and communication technology adoption in small- and medium-sized enterprises: Demographic characteristics. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(10), 969–980. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no10.969